Abstract

Objective:

To assess whether duration, recency or type of hormonal contraceptive used is associated with anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) concentration given that the existing literature regarding the association between hormonal contraceptive use and AMH concentrations is inconsistent.

Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Setting:

Baseline data from the Study of the Environment, Lifestyle and Fibroids Study (SELF), a five-year longitudinal study of African American women.

Patients:

1,643 African American women aged 23–35 years at time of blood draw (2010–2012).

Interventions:

None.

Main Outcome Measures:

Serum AMH measured using an ultrasensitive enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Linear regression models were used to estimate percent differences in mean AMH concentrations and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by hormonal contraceptive use, with adjustment for potential confounders.

Results:

In multivariable-adjusted analyses, current users of hormonal contraceptives had 25.2% lower mean AMH concentrations than never users (95% CI −35.3%, −13.6%). AMH concentrations showed little difference among previous users of hormonal contraceptives compared with never users (−4.4%, 95% CI −16.3%, 9.0%). AMH concentrations were not appreciably associated with cumulative duration of use among previous users or time since last use among non-current users. Current users of combined oral contraceptives (−24.0%, 95% CI −36.6%, −8.9%), vaginal ring (−64.8%, 95% CI −75.4%, −49.6%), and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (−26.7%, 95% CI −41.0%, −8.9%) had lower mean AMH concentrations than never users.

Conclusion:

The present data suggest that AMH levels are significantly lower among current users of most forms of hormonal contraceptives, but that the suppressive effect of hormonal contraceptives on AMH levels is reversible.

Keywords: Anti-Müllerian hormone, hormonal contraceptives, ovarian reserve

Capsule:

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels were significantly lower among women currently using most forms of hormonal contraceptives, but the suppressive effect of hormonal contraceptives on AMH levels appeared reversible.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian reserve refers to a woman’s reproductive potential as a function of the number of her remaining oocytes. Though there are several known serum biomarkers of ovarian reserve (follicle stimulating hormone, estradiol, and inhibin B), growing evidence over the last decade has suggested that anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) more accurately reflects the follicular pool (1–4). AMH production begins in the granulosa cells of primary follicles, though the majority of circulating AMH is derived from pre-antral and early antral follicles (5, 6). As such, serum AMH is proportionally related to the size of the primordial follicle pool and represents ovarian reserve (2).

Relative to conventional biomarkers, AMH concentrations have low inter- and intra-cycle variability (7, 8). Based on these findings, AMH is increasingly used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes (9–13). To aid in the clinical interpretation of AMH concentrations, several nomograms have been published describing the range of normal AMH levels in various populations (14–19). The ‘utility of these nomograms has been questioned, however, as AMH concentrations can vary with numerous intrinsic, iatrogenic, and environmental factors (20–22).

One factor that may affect AMH concentration is hormonal contraceptive use. The effect of hormonal contraceptive use on AMH concentration has broad clinical implications given that more than 60% of reproductive-age women currently use contraceptives, the majority of which are hormonal methods (23). While combined oral contraceptives (COC) have traditionally been the most commonly used hormonal contraceptives, other hormonal methods (including depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [DMPA], the patch, hormonal intrauterine device [LNG-IUD], and ring) have increased in popularity in recent years (24).

Existing literature regarding the association between hormonal contraceptive use and AMH concentration is inconsistent. While some studies suggest hormonal contraceptive use lowers AMH concentration (20, 25–34), others have found no effect (35–39). The larger studies to date concluded that women actively using hormonal contraceptives have significantly lower AMH levels (20, 25, 27). A systematic review reported that AMH concentration does not seem to be altered in those using hormonal contraceptives during the first six months, but there does appear to be a decline in AMH concentration in long term users. This reduction in AMH concentration in long term users appears reversible after discontinuation of hormonal contraceptives (40). As previous studies have been largely limited to women using COC, it is unclear whether these findings can be generalized to other types of hormonal contraceptives. Few studies have investigated the effect of specific types of hormonal contraceptives on AMH concentrations (27, 29–31, 36, 39), and many of these studies have small sample sizes. The largest study examining the relationship of various types of hormonal contraceptives and AMH concentration concluded that AMH levels measured concurrent with use were lower in users of some, but not all, of the types of contraceptives studied (25). Users of COC, the progestin-only pill, and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system had lower AMH levels (25).

It is also unclear whether AMH levels are permanently influenced by hormonal contraceptive use. Although a prospective study of long-term users of COCs reported that after discontinuation, AMH concentration increased for the subsequent two months (41). To our knowledge, no study has investigated the association of current and former use of hormonal contraceptives including long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) and AMH concentration. There is also a paucity of data in the literature on whether the age of initiation of use or cumulative use influences AMH concentration. To address these deficits in the literature, we evaluated the association between AMH concentration and history, type, duration and recency of hormonal contraceptive use among a large population of reproductive-aged African American women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

We analyzed baseline data from the Study of Environment, Lifestyle, and Fibroids (SELF). From November 2010 through December 2012, 1,693 premenopausal African American women aged 23–34 were recruited to participate. Exclusion criteria included: hysterectomy, a previous clinical diagnosis of uterine fibroids, use of medication to treat an autoimmune disorder (including: multiple sclerosis, Grave’s disease, scleroderma, lupus, or Sjogren’s), or use of chemotherapy or radiation treatment for a previous cancer diagnosis. Details about the study design, methods, and recruitment have been described previously (42) and additional information is included as supplemental material. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions.

Assays

Women were recruited from 2010–2012. At the time of enrollment, up to 55 mL of blood was drawn from each participant. Until analysis was performed serum was stored at −80° C. ln 2018, frozen samples were shipped to Ansh labs, (Webster, Texas, USA) where AMH assays were performed using the picoAMH assay which is an ultrasensitive enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). AMH values are presented in concentration of ng/mL. The lower limit of detection of the test was 1.3 pg/mL and the limit of blank was 0.5 pg/mL. The measuring range was 6.0 to 1,150 pg/mL (0.043 pmol/L to 8.21 pmol/L). If necessary, specimens were diluted up to 20-fold prior to assay, thus extending the measuring range up to 23,000 pg/mL (23 ng/mL, 164 pmol/L). Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <5%.

Hormonal Contraceptive Variables

We restricted this analysis to include women who were using the following types of hormonal contraceptives: combined oral contraceptives (COC), etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring (ring), depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), etonogestrel implant (implant), ethinyl estradiol/norelgestromin transdermal patch (patch), and levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG-IUD). Due to limited information on details of use, progestin-only pill (POP) users were not analyzed as a separate group of hormonal contraceptives. The association between AMH concentration and use of hormonal contraceptives, age at initiation, cumulative duration of use, recency of use and type of hormonal contraceptive was examined. Data on hormonal contraceptive use were self-reported by participants.

Age at first use of each hormonal contraceptive was reported at interview. For current and previous users of hormonal contraceptives, cumulative duration of use before enrollment was reported for each method separately in years and months, with the exception of COCs. Cumulative duration of COCs for current and previous users was calculated by first subtracting the age at which the participant reported initiating COCs from her age at enrollment (current user) or the age at which she discontinued use. This value was then weighted based on the participant’s response to how much of the time between those ages they used COCs (very little of that time, less than half of that time, about half of that time, more than half of that time, most of that time or the whole time). Among former users of hormonal contraceptives we calculated the duration of time since last hormonal contraceptive use (recency) by subtracting the age at last hormonal contraceptive use from the participant’s current age. Type-specific duration of use captured the entire history of use and was not designed to capture the most recent contiguous period of use. Total cumulative duration of all hormonal contraceptive use was calculated for current and former users of any of the queried hormonal contraceptive types by adding the individual durations of each type.

Covariates

We controlled for both age and a quadratic term for age because of the strong non-linear association between age and AMH levels. We also controlled for BMI (calculated from height and weight data measured at the clinic by trained study staff), and self-reported history of abnormal menstrual bleeding, any thyroid condition, and seeking care for difficulty conceiving as these factors were found to be associated with AMH levels in previous analyses of this cohort (22). Although menstrual cycle length was also found to be significantly associated with AMH levels in the previous analyses, this variable could not be included in this multivariable model because cycle length can only be assessed accurately off hormonal contraceptives. Therefore, we controlled for a self-reported diagnosis of PCOS given the association with cycle length. Given that PCOS is often under-ascertained among women, we additionally performed sensitivity analyses that controlled for reported menstrual cycle length when participants were aged 18–22 and off hormonal contraceptives. We reasoned that long menstrual cycles during this age range may serve as a proxy for PCOS which is often undiagnosed (43). Although we did not find an association between cigarette smoking and AMH levels in this cohort previously (44), given that other studies have demonstrated a relationship between cigarette smoking and both AMH and earlier time to menopause (20, 45, 46) we also conducted sensitivity analyses that controlled for current or previous cigarette smoking.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed the distribution of AMH levels and the explanatory variables of interest (use of hormonal contraceptives, cumulative duration of use, age at initiation, recency of use and type of hormonal contraceptives used). We calculated means or medians (with standard deviations [SD] or interquartile ranges [IQR]) for continuous variables, and proportions for categorical variables. As AMH levels were not normally distributed, for sample description we compared median AMH levels using Dwass, Steel, Critchlow-Fligner (DSCF) multiple comparison analysis based on two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

We used a multivariable linear regression model to estimate the percent difference in mean AMH levels (β) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for hormonal contraceptive users vs non-users. The covariates included in the multivariable model included age, age2, BMI, and self-reported history of abnormal menstrual bleeding, any thyroid condition, seeking care for difficulty conceiving or PCOS. We investigated hormonal contraceptives as a group (COC, ring, DMPA, implant, patch and LNG-IUD together). We also examined individual types of contraceptives separately if we had adequate sample size (COC, ring, DMPA and LNG-IUD) to determine differences in AMH levels between current and never users. To further investigate the association between AMH levels and duration of use and recency of use in current and previous users where the sample size was large enough, we also examined users of COC, DMPA, and LNG-IUD separately. For all analyses, the AMH concentrations were log-transformed to account for the non-normality.

For the full analysis that grouped all hormonal contraceptive types, all participants were included in the analysis. For the subgroup analyses by type (COC, DMPA, and LNG-IUD), participants were excluded if they were pregnant within 3 months of the baseline visit (n=29) or had used a hormonal contraceptive other than the type of interest in the analysis within 12 months of the baseline visit and within 24 months for DMPA use (COC Analysis: n=465 excluded; DMPA analysis: n=517 excluded; LNG-IUD analysis: n=588 excluded). The COC subgroup analysis further excluded participants who had ever used POPs (n=76).

All analyses were carried out using Statistical Analysis Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

1,693 African-American women were enrolled in SELF, and serum AMH was available for 1,643 individuals. Demographic details for this cohort of women are included in Table 1. The mean age of participants (±SD) considered in this analysis was 29.2 ± 3.4 years. The median AMH concentration was 4.07 (IQR 2.29–6.70). 460 participants (28.0%) were currently using some form of a hormonal contraceptive and a further 951 (57.9%) endorsed a history of previous hormonal contraceptive use.

Table 1:

Demographic Data for Study Participants (n=1643)

| Hormonal contraceptive usea | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current (n=460) | Former (n=951) | Never (n=232) | |

| Age at enrollment, y (mean ± SD; range)b | 28.8 ± 3.3; 23–35 | 29.6 ± 3.5; 23–35 | 28.4 ± 3.4; 23–35 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (mean ± SD; range) | 32.2 ± 8.6; 17.8–68.3 | 34.1 ± 9.7; 15.9–79.4 | 35.0 ± 10.9; 17.5–72.9 |

| AMH, ng/mL (median, IQR) | 3.56 (3.8) | 4.23 (4.8) | 4.71(4.3) |

| AMH, ng/mL (range) | <0.002–26.0 | <0.002–55.7 | 0.04–22.2 |

| Education (%) | |||

| High school/GED or less | 15.7 | 23.2 | 29.7 |

| Some college, associate’s, or technical degree | 50.7 | 50.9 | 44.8 |

| Bachelor’s or graduate degree | 33.7 | 25.8 | 25.4 |

| Income (%) | |||

| Less than $20,000 | 37.6 | 48.1 | 52.6 |

| $20,000–50,000 | 40.4 | 36.3 | 29.7 |

| More than $50,000 | 21.7 | 14.8 | 16.4 |

| Current smoker (%) | 11.5 | 22.0 | 23.3 |

| History of polycystic ovarian syndrome (%) | 2.2 | 4.1 | 1.3 |

| History of abnormal menstrual bleeding (%) | 9.6 | 12.5 | 10.3 |

| History of thyroid condition (%) | 2.4 | 3.5 | 1.7 |

| History of seeking care for difficulty conceiving (%) | 2.6 | 7.5 | 5.6 |

| History of previous birth (%) | 67.6 | 64.1 | 34.9 |

| Number of pregnancies (mean ± SD; range)c | 2.9 ± 1.8; 1–15 | 3.3 ± 2.1; 1–13 | 2.5 ± 1.9; 1–13 |

SD=standard deviation, IQR=interquartile range

Includes users of COC, ring, DMPA, implant, patch and LNG-IUD

Women ages 23–34 were recruited, but some women had turned 35 by the time that all baseline activities and enrollment were completed.

Among gravid women (n=356 current users, n=738 former users, n=112 never users)

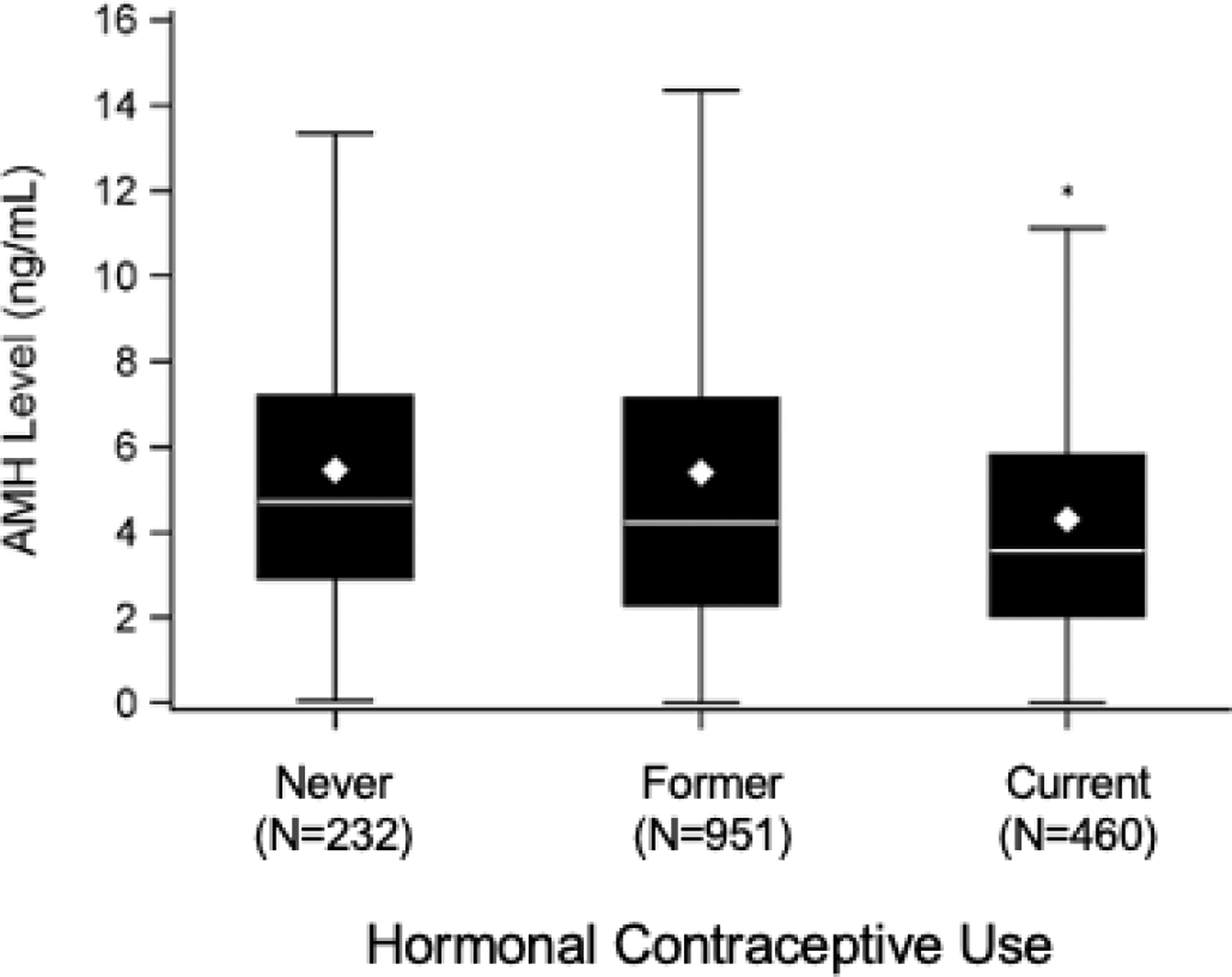

AMH and Hormonal Contraceptive Status

Median AMH levels among current hormonal contraceptive users (3.56, IQR 2.03–5.81) was lower than those who had previously used hormonal contraceptives (4.23, IQR 2.30–7.13; p<.001), and those who had never used hormonal contraceptives (4.71, IQR 2.92–7.19; p<.001) (Figure 1). As shown in Table 2, multivariable adjusted analysis demonstrated that AMH levels in current users of hormonal contraceptives were 25.2% lower than AMH levels in those who had never used hormonal contraceptives. AMH levels were not significantly different comparing previous with never users of hormonal contraceptives.

Figure 1:

Box plot demonstrating median AMH concentrations of current hormonal contraceptive users compared to former and never hormonal contraceptive users.

* denotes statistically significant difference in AMH compared to other groups.

Table 2:

Multivariable Adjusted Associations of AMH with Hormonal Contraceptive Usea, Cumulative Duration of Use, Age at Start, and Time Since Last Use Compared to Never Usersb

| N | Estimate of % change in AMH (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Status of hormonal contraceptive use | ||

| Never | 232 | Reference |

| Former | 951 | −4.4% (−16.3%, 9.0%) |

| Current | 460 | −25.2% (−35.3%, −13.6%) |

| Total duration of hormonal contraceptive use (ever users) | ||

| Current and cumulative use <1 year | 20 | −33.5% (−56.1%, 0.8%) |

| Current and cumulative use 1–3 years | 92 | −21.1% (−36.9%, −1.4%) |

| Current and cumulative use ≥4 years | 328 | −26.9% (−37.4%, −14.7%) |

| Former and cumulative use <1 year | 183 | −2.2% (−18.1%, 16.8%) |

| Former and cumulative use 1–3 years | 354 | −3.4% (−17.0%, 12.5%) |

| Former and cumulative use ≥4 years | 414 | −6.5% (−19.5%, 8.6%) |

| Age at start of hormonal contraceptive (ever users) | ||

| <15 years | 145 | −12.2% (−27.5%, 6.3%) |

| 15–20 years | 968 | −11.3% (−22.3%, 1.3%) |

| 21–25 years | 236 | −14.0% (−27.3%, 1.6%) |

| ≥26 years | 47 | −19.7% (−39.9%, 7.2%) |

| Time since last use of hormonal contraceptive (ever users) | ||

| Current | 460 | −26.1% (−36.2%, −14.5%) |

| Within last year | 124 | −5.1% (−22.2%, 15.8%) |

| > 1 year ago | 827 | −4.4% (−16.4%, 9.4%) |

Includes users of COC, ring, DMPA, implant, patch and LNG-IUD

The reference group is “never users” (n= 232)

The multivariable model adjusted for age, age2, BMI, and reported histories of PCOS, abnormal menstrual bleeding, thyroid condition, and seeking care for difficulty conceiving.

Cumulative Duration, Age at Start, and Recency of Using Hormonal Contraceptive Use (Combining Use of COC, Ring, DMPA, Implant, Patch and LNG-IUD)

The mean lifetime cumulative duration of hormonal contraceptive use among ever users was 61.0 months (SD 49.58, range 0–236.6) and among current hormonal contraceptive users was 62.0 months (SD 49.6; range 1–205 months). Within current and previous users, there was no appreciable difference by cumulative duration of use. Among participants who ever used hormonal contraceptives, the mean age at first use was 18.1 years (SD 3.34, range 8–33 years). As shown in Table 2, compared to never users, AMH levels did not show differences by age of initiation among ever users. The mean amount of time since last use of hormonal contraceptives in those who ever used was 42.8 months (SD 51.07, range 0–251). As shown in Table 2, AMH levels were lower only among current users of hormonal contraceptives (−26.1%, 95% CI −36.2%, −14.5%). Those who last used within the year or those who last used more than one year prior did not have meaningfully lower AMH concentrations.

AMH and Hormonal Contraceptive Type

When type of hormonal contraceptive was assessed among current hormonal contraceptive users, the most commonly used types were COC (39%), LNG-IUD (25%), and DMPA (22%). Median AMH levels among users of the various types of hormonal contraceptives compared to those who never used hormonal contraceptives are shown in Table 3. Current use of COC, vaginal ring, and DMPA were inversely associated with AMH levels in the multivariable analysis. Compared with never users of hormonal contraceptives, AMH levels were 24.0% lower in COC users. The dose of ethinyl estradiol (EE) in the COC was not associated with AMH levels. When the lowest dose of EE (10–20 mcg) was compared to 25–30 mcg and 35 mcg of EE, there was no difference in AMH concentration. AMH levels were 64.8% lower in vaginal ring users and 26.7% lower in DMPA users compared to never users of hormonal contraceptives. There was a small, non-significant reduction in AMH levels for current LNG-IUD users.

Table 3:

Multivariable Adjusted Associations of Hormonal Contraceptive Type with AMH Among Current Users Compared to Never Users

| N | AMH, ng/mL Median (IQR) | Estimate of % change in AMH (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never use | 232 | 4.71 (2.92, 7.19) | Reference |

| COC | 180 | 3.54 (2.01, 5.97) | −24.0% (−36.6%, −8.9%) |

| Ring | 28 | 1.89 (1.38, 3.91) | −64.8% (−75.4%, −49.6%) |

| DMPA | 103 | 3.23 (1.92, 5.72) | −26.7% (−41.0%, −8.9%) |

| LNG-IUD | 116 | 3.89 (2.46, 6.15) | −8.7% (−25.7%, 12.2%) |

COC=combined oral contraceptives, DMPA=depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, LNG-IUD=levonorgestrel IUD The multivariable model adjusted for age, age2, BMI, and reported histories of PCOS, abnormal menstrual bleeding, thyroid condition, and seeking care for difficulty conceiving

The association between AMH levels and lifetime cumulative duration of use in current and previous users was examined by hormonal contraceptive type. Participants who were current users of COC (−25.8%, 95% CI −37.6%, −11.7%) or DMPA (−34.4%, 95% CI −47.2%, −18.5%) with cumulative use of one year or more had lower AMH levels than never users. There were very few current users of COC or DMPA with less than a year of cumulative use (n=10 and n=8 respectively). While AMH concentrations were lower for current COC users of less than one year of cumulative use compared to never users the estimate was quite imprecise (−36.8%, 95% CI −63.4%, 9.0%). AMH levels were not significantly lower in previous COC or DMPA users compared to never users, regardless of the duration of COC or DMPA use. There was a trend toward lower AMH levels in those who were current LNG-IUD users for one or more years (−13.8%, 95% CI −29.0, 4.6%), but there was no significant association between AMH levels and duration of use in current or former LNG-IUD users when compared to never users, regardless of length of use.

The association between AMH levels and time since last use was also examined by hormonal contraceptive type. In previous COC users, including those who had used within the last year, there was no significant association between AMH concentration and time since last use when compared to never users. Although AMH levels were not different for previous users of DMPA as a group compared to never users, there were lower AMH levels for those who had used DMPA within the last year (−15.6%, 95% CI −39.3%, 17.4%), or one to two years ago (−12.6%, 95% CI −31.9%, 12.1%). Last use of DMPA more than two years ago was not appreciably associated with current AMH concentrations. Compared to never users, AMH levels were not significantly lower in those who previously used LNG-IUD regardless of recency of use.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses in which we further controlled for cigarette smoking (current, previous, never) or usual menstrual cycle length at age 18–22 years among non-users of hormonal contraceptives showed largely similar results.

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort study, AMH levels were lower among the group of current hormonal contraceptives users, while past use was not associated with AMH levels. Neither cumulative duration of hormonal contraceptive use among previous users nor recent cessation of hormonal contraceptive use were appreciably associated with AMH concentrations. Among past users of hormonal contraceptives, AMH levels appear to rebound within a year of last use. Type of hormonal contraceptive used appears to play a role in the observed association. Current use of COC, ring, and DMPA was inversely associated with AMH levels. Together our findings suggest that current users of many types of hormonal contraceptives have lower AMH levels, and this effect is reversible. AMH levels in previous COC users may return to baseline more quickly after ceasing use than AMH levels in previous DMPA users.

The present findings contribute to a conflicting body of literature regarding the association between hormonal contraceptives and AMH concentration. Although our findings concur with three large studies (20, 25, 27) that demonstrated reductions in AMH levels with hormonal contraceptive use, several other studies have reported that AMH concentrations are not influenced by current hormonal contraceptive use (35–39). One study showed no difference in the AMH levels of participants who had been using COC for more than a year compared with age-matched women who had not used hormonal contraceptives within the last year (35). Another study found little appreciable change in AMH levels after six cycles of COC use (37). Two other studies of short term hormonal contraceptive use of up to two cycles also found no association with AMH levels. (38, 39). Notably, these were relatively small studies (20–45 women) and this may have contributed to findings that were discordant from our study. Further, in two of these studies the women used COC for a short duration which may not have been long enough to lead to a decrease in AMH levels.

Many studies that have reported lower AMH levels among hormonal contraceptive users have solely considered women using COC (20, 26, 28, 32, 33). While several studies have included individuals using other types of hormonal contraceptives along with COC, (27, 29, 31) studies that have specifically examined the relationship between AMH concentrations and individual types of hormonal contraceptives other than COCs are limited. In one of the largest studies examining multiple types of contraceptives, AMH levels were 17.1% lower in 90 IUD users (95% CI −31.4, 0.002), but this decline was not statistically significant. In the same study there was not a significant decrease in AMH levels in 16 ring users (−12.2%, 95% CI −42.7, 34.3) (25). Another study reported significantly lower AMH levels in COC, patch, and ring users (n=18 in each group) (30). Conversely, a study that included users of COC (n=23), IUD (n=20), and DMPA (n=20) concluded that AMH levels were unaffected by hormonal contraceptive use. Notably, although there was not a statistically significant decline in AMH levels, there was a relatively large difference in pre- and post-treatment AMH levels in the COC group (27.2 pmol/L vs 17.1 pmol/L) (36). Further, the analyses were not age adjusted and the median age for DMPA users was 37 years, making a comparison to our data challenging. In our study AMH levels of current LNG-IUD users were not significantly lower than AMH levels of never users. While there was a trend toward lower AMH levels (−13.4%) in those who were currently using the LNG-IUD for one year or more, the association with AMH concentrations was not significant. Further investigation is warranted to examination the association between AMH levels and LNG-IUD use.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that DMPA use is inversely associated with AMH levels. Although only current users of DMPA had significantly lower AMH levels, AMH levels were lower in more recent past users of DMPA which suggests that AMH levels may take time to recover after cessation of DMPA use. We hypothesize that the association observed among users of DMPA (a high-dose progestin-only injection administered every three months) is best explained by previous findings that suggested luteinization has an adverse effect on AMH production by granulosa cells (47). Conversely, the effect of the combined hormonal contraceptive methods on AMH concentrations is likely the result of down-regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, resulting in decreased production of FSH and LH, and altered antral follicle development (26). Our results demonstrate significantly lower AMH levels in current DMPA users with cumulative use of more than one year. However, given our small numbers for current DMPA users with cumulative use less than one year, we are unable to determine if short term use of DMPA is sufficient to result in lower AMH concentrations. A larger sample of women using DMPA for less than one year is needed.

AMH levels were lower across all durations of use categories for current hormonal contraceptive use suggesting that even short-term use of hormonal contraceptives may lower AMH concentrations. Previous users of hormonal contraceptives did not have AMH levels that were materially different from never users, nor was length of time using hormonal contraceptives associated with AMH levels in previous users. These findings suggest that the decline in AMH levels due to hormonal contraceptive use is reversible within one year of cessation of use and agree with several previous studies. In a study of 68 women with a history of long term COC, there was a 53% improvement in AMH after discontinuation of COC and AMH levels increased from baseline until two months after COC were discontinued (41). Further supporting the notion that AMH concentration recovers after cessation of hormonal contraceptives, in women who were off of hormonal contraceptives for one year but that had previously used for ten or more years, AMH levels were similar to those who never used hormonal contraceptives(48). The reversible nature of the observed reductions in AMH levels, demonstrated in our study as well as others (20, 33), seems to indicate the decline in AMH concentration associated with hormonal contraceptive use does not reflect a change in ovarian reserve. More likely, the reduction in AMH levels among current hormonal contraceptive users represents alterations in follicular development resulting from down-regulation of the HPO axis (26).

There are several strengths of this study. First, this study examines a large population with access to and wide uptake of a number of different forms of hormonal contraceptives that may have been utilized less in older aged cohorts. Further, over 1,600 study participants were recruited directly from the community, rather than from fertility clinics or other medical settings. In addition, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between use of hormonal contraceptives and AMH levels in a population of young African-American women.

One study limitation is that because only African American women were studied, the generalizability of these findings may be limited, as several studies have suggested racial/ethnic differences in AMH levels (21, 49–52). However we would not expect hormonal contraceptives to influence AMH concentrations differently by race or ethnicity, although confirmation of this requires further investigation. Additionally, the smaller sample sizes of some of the individual types of hormonal contraceptives (patch n=5, implant n=13, and ring n=28) precluded evaluating these methods individually. Sample size may also be considered in the interpretation of the more detailed analyses of the associations between AMH levels and COC, DMPA and LNG-IUD use given the small number of users in some of the subgroups. Another study limitation is that the duration variable was calculated using cumulative duration, which could alter results in those who had breaks in their use. An additional limitation is that the samples were stored for 6–8 years before the assays were run and there are limited data on the reliability of AMH levels after long-term storage of serum. The samples were not run in duplicate due to a limited budget. Lastly, all variables related to contraceptive use were self-reported and there was no feasible way to validate participants’ hormonal contraceptive use using pharmacy or medical records. Given the in-depth nature of the survey questions (participants answered up to 41 questions on current and previous contraceptive use), and research documenting generally high accuracy of self-reported data on oral contraceptive use relative to pharmacy or medical records (53–55), bias due to misclassification is likely to be small. Furthermore, the prevalence of hormonal contraceptive use in the SELF cohort (28%) is highly consistent with national data on reproductive-aged women (56). We would expect any misclassification of current hormonal contraceptive use to be non-differential, which would bias the results towards the null.

CONCLUSIONS

The present data suggest that AMH levels are significantly lower among women currently using most forms of hormonal contraceptives, but that the suppressive effect of hormonal contraceptives on AMH levels is reversible. Consequently, when measured as a marker of ovarian reserve, AMH should be interpreted with caution in women using hormonal contraceptives. Although this study demonstrates that previous hormonal contraceptive users ultimately achieve similar AMH levels to those who have never used, the precise duration of time required for AMH levels to return to normal after discontinuation of hormonal contraceptives requires further investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Patrick Sluss and the Clinical Laboratory Research Core in the Pathology Department at Massachusetts General Hospital for performing the assays used in this study. We thank Dr. Julie White for reviewing the manuscript. We also thank the study SELF Study Team, women who took part in this study, and the many others who made this study possible.

Funding: Supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HD088638 to EEM). In addition, the research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and in part by funds allocated for health research by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: LAB, MSW, AW, QH, MRC and DDB have nothing to declare. LAW is a consultant for AbbVie, Inc. EEM is a consultant for Myovant Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Rooij IA, Tonkelaar I, Broekmans FJ, Looman CW, Scheffer GJ, de Jong FH et al. Antimullerian hormone is a promising predictor for the occurrence of the menopausal transition. Menopause 2004;11:601–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Vet A, Laven JS, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Fauser BC. Antimullerian hormone serum levels: a putative marker for ovarian aging. Fertil Steril 2002;77:357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fanchin R, Schonauer LM, Righini C, Guibourdenche J, Frydman R, Taieb J. Serum anti-Mullerian hormone is more strongly related to ovarian follicular status than serum inhibin B, estradiol, FSH and LH on day 3. Hum Reprod 2003;18:323–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, Scheffer GJ, Looman CW, Habbema JD, de Jong FH et al. Serum antimullerian hormone levels best reflect the reproductive decline with age in normal women with proven fertility: a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril 2005;83:979–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen CY, Byskov AG. Estradiol and regulation of anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin-A, and inhibin-B secretion: analysis of small antral and preovulatory human follicles’ fluid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4064–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weenen C, Laven JS, Von Bergh AR, Cranfield M, Groome NP, Visser JA et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone expression pattern in the human ovary: potential implications for initial and cyclic follicle recruitment. Mol Hum Reprod 2004;10:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Marca A, Giulini S, Tirelli A, Bertucci E, Marsella T, Xella S et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone measurement on any day of the menstrual cycle strongly predicts ovarian response in assisted reproductive technology. Hum Reprod 2007;22:766–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Disseldorp J, Lambalk CB, Kwee J, Looman CW, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC et al. Comparison of inter- and intra-cycle variability of anti-Mullerian hormone and antral follicle counts. Hum Reprod 2010;25:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broer SL, Eijkemans MJ, Scheffer GJ, van Rooij IA, de Vet A, Themmen AP et al. Antimullerian hormone predicts menopause: a long-term follow-up study in normoovulatory women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:2532–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broer SL, Mol BW, Hendriks D, Broekmans FJ. The role of antimullerian hormone in prediction of outcome after IVF: comparison with the antral follicle count. Fertil Steril 2009;91:705–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewailly D, Andersen CY, Balen A, Broekmans F, Dilaver N, Fanchin R et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum Reprod Update 2014;20:370–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knauff EA, Eijkemans MJ, Lambalk CB, ten Kate-Booij MJ, Hoek A, Beerendonk CC et al. Anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin B, and antral follicle count in young women with ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:786–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee on Gynecologic P. Committee opinion no. 618: Ovarian reserve testing. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:268–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagen CP, Aksglaede L, Sorensen K, Main KM, Boas M, Cleemann L et al. Serum levels of anti-Mullerian hormone as a marker of ovarian function in 926 healthy females from birth to adulthood and in 172 Turner syndrome patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:5003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelsey TW, Wright P, Nelson SM, Anderson RA, Wallace WH. A validated model of serum antimullerian hormone from conception to menopause. PLoS One 2011;6:e22024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Marca A, Spada E, Grisendi V, Argento C, Papaleo E, Milani S et al. Normal serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels in the general female population and the relationship with reproductive history. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012;163:180–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lie Fong S, Visser JA, Welt CK, de Rijke YB, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ et al. Serum antimullerian hormone levels in healthy females: a nomogram ranging from infancy to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:4650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson SM, Messow MC, Wallace AM, Fleming R, McConnachie A. Nomogram for the decline in serum antimullerian hormone: a population study of 9,601 infertility patients. Fertil Steril 2011;95:736–41 e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seifer DB, Baker VL, Leader B. Age-specific serum anti-Mullerian hormone values for 17,120 women presenting to fertility centers within the United States. Fertil Steril 2011;95:747–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolleman M, Verschuren WM, Eijkemans MJ, Dolle ME, Jansen EH, Broekmans FJ et al. Reproductive and lifestyle determinants of anti-Mullerian hormone in a large population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:2106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bleil ME, Gregorich SE, Adler NE, Sternfeld B, Rosen MP, Cedars MI. Race/ethnic disparities in reproductive age: an examination of ovarian reserve estimates across four race/ethnic groups of healthy, regularly cycling women. Fertil Steril 2014;101:199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsh EE, Bernardi LA, Steinberg ML, de Chavez PJ, Visser JA, Carnethon MR et al. Novel correlates between antimullerian hormone and menstrual cycle characteristics in African-American women (23–35 years-old). Fertil Steril 2016;106:443–50 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. NCHS Data Brief 2014:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniels K, Mosher WD. Contraceptive methods women have ever used: United States, 1982–2010. Natl Health Stat Report 2013:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landersoe SK, Forman JL, Birch Petersen K, Larsen EC, Nohr B, Hvidman HW et al. Ovarian reserve markers in women using various hormonal contraceptives. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2020;25:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arbo E, Vetori DV, Jimenez MF, Freitas FM, Lemos N, Cunha-Filho JS. Serum anti-mullerian hormone levels and follicular cohort characteristics after pituitary suppression in the late luteal phase with oral contraceptive pills. Hum Reprod 2007;22:3192–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bentzen JG, Forman JL, Pinborg A, Lidegaard O, Larsen EC, Friis-Hansen L et al. Ovarian reserve parameters: a comparison between users and non-users of hormonal contraception. Reprod Biomed Online 2012;25:612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabregues F, Castelo-Branco C, Carmona F, Guimera M, Casamitjana R, Balasch J. The effect of different hormone therapies on anti-mullerian hormone serum levels in anovulatory women of reproductive age. Gynecol Endocrinol 2011;27:216–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson LN, Sammel MD, Dillon KE, Lechtenberg L, Schanne A, Gracia CR. Antimullerian hormone and antral follicle count are lower in female cancer survivors and healthy women taking hormonal contraception. Fertil Steril 2014;102:774–81 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kallio S, Puurunen J, Ruokonen A, Vaskivuo T, Piltonen T, Tapanainen JS. Antimullerian hormone levels decrease in women using combined contraception independently of administration route. Fertil Steril 2013;99:1305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kristensen SL, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Andersen CY, Ernst E, Olsen SF, Bonde JP et al. The association between circulating levels of antimullerian hormone and follicle number, androgens, and menstrual cycle characteristics in young women. Fertil Steril 2012;97:779–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw CM, Stanczyk FZ, Egleston BL, Kahle LL, Spittle CS, Godwin AK et al. Serum antimullerian hormone in healthy premenopausal women. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2718–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Berg MH, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Overbeek A, Twisk JW, Schats R, van Leeuwen FE et al. Comparison of ovarian function markers in users of hormonal contraceptives during the hormone-free interval and subsequent natural early follicular phases. Hum Reprod 2010;25:1520–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birch Petersen K, Hvidman HW, Forman JL, Pinborg A, Larsen EC, Macklon KT et al. Ovarian reserve assessment in users of oral contraception seeking fertility advice on their reproductive lifespan. Hum Reprod 2015;30:2364–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deb S, Campbell BK, Pincott-Allen C, Clewes JS, Cumberpatch G, Raine-Fenning NJ. Quantifying effect of combined oral contraceptive pill on functional ovarian reserve as measured by serum anti-Mullerian hormone and small antral follicle count using three-dimensional ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2012;39:574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li HW, Wong CY, Yeung WS, Ho PC, Ng EH. Serum anti-mullerian hormone level is not altered in women using hormonal contraceptives. Contraception 2011;83:582–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somunkiran A, Yavuz T, Yucel O, Ozdemir I. Anti-Mullerian hormone levels during hormonal contraception in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2007;134:196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steiner AZ, Stanczyk FZ, Patel S, Edelman A. Antimullerian hormone and obesity: insights in oral contraceptive users. Contraception 2010;81:245–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Streuli I, Fraisse T, Pillet C, Ibecheole V, Bischof P, de Ziegler D. Serum antimullerian hormone levels remain stable throughout the menstrual cycle and after oral or vaginal administration of synthetic sex steroids. Fertil Steril 2008;90:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amer S, James C, Al-Hussaini TK, Mohamed AA. Assessment of Circulating Anti-Mullerian Hormone in Women Using Hormonal Contraception: A Systematic Review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020;29:100–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landersoe SK, Birch Petersen K, Sorensen AL, Larsen EC, Martinussen T, Lunding SA et al. Ovarian reserve markers after discontinuing long-term use of combined oral contraceptives. Reprod Biomed Online 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baird DD, Harmon QE, Upson K, Moore KR, Barker-Cummings C, Baker S et al. A Prospective, Ultrasound-Based Study to Evaluate Risk Factors for Uterine Fibroid Incidence and Growth: Methods and Results of Recruitment. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fauser BC, Tarlatzis BC, Rebar RW, Legro RS, Balen AH, Lobo R et al. Consensus on women’s health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the Amsterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored 3rd PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Fertil Steril 2012;97:28–38 e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawkins Bressler L, Bernardi LA, De Chavez PJ, Baird DD, Carnethon MR, Marsh EE. Alcohol, cigarette smoking, and ovarian reserve in reproductive-age African-American women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:758 e1–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mattison DR, Thorgeirsson SS. Smoking and industrial pollution, and their effects on menopause and ovarian cancer. Lancet 1978;1:187–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plante BJ, Cooper GS, Baird DD, Steiner AZ. The impact of smoking on antimullerian hormone levels in women aged 38 to 50 years. Menopause 2010;17:571–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fanchin R, Louafi N, Mendez Lozano DH, Frydman N, Frydman R, Taieb J. Per-follicle measurements indicate that anti-mullerian hormone secretion is modulated by the extent of follicular development and luteinization and may reflect qualitatively the ovarian follicular status. Fertil Steril 2005;84:167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kucera R, Ulcova-Gallova Z, Topolcan O. Effect of long-term using of hormonal contraception on anti-Mullerian hormone secretion. Gynecol Endocrinol 2016;32:383–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gold EB, Bromberger J, Crawford S, Samuels S, Greendale GA, Harlow SD et al. Factors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:865–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henderson KD, Bernstein L, Henderson B, Kolonel L, Pike MC. Predictors of the timing of natural menopause in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:1287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKnight KK, Wellons MF, Sites CK, Roth DL, Szychowski JM, Halanych JH et al. Racial and regional differences in age at menopause in the United States: findings from the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:353 e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seifer DB, Golub ET, Lambert-Messerlian G, Benning L, Anastos K, Watts DH et al. Variations in serum mullerian inhibiting substance between white, black, and Hispanic women. Fertil Steril 2009;92:1674–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norell SE, Boethius G, Persson I. Oral contraceptive use: interview data versus pharmacy records. Int J Epidemiol 1998;27:1033–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spangler L, Ichikawa LE, Hubbard RA, Operskalski B, LaCroix AZ, Ott SM et al. A comparison of self-reported oral contraceptive use and automated pharmacy data in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women. Ann Epidemiol 2015;25:55–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nischan P, Ebeling K, Thomas DB, Hirsch U. Comparison of recalled and validated oral contraceptive histories. Am J Epidemiol 1993;138:697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. NCHS data brief, no 173. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.