Abstract

Background:

Cross-sectional studies have shown lower cerebral blood flow (CBF) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) but longitudinal CBF changes in AD are still unknown.

Objective:

To reveal the longitudinal CBF changes in normal control (NC) and the AD continuum using Arterial Spin Labeling perfusion MRI (ASL MRI)

Methods:

CBF was calculated from two longitudinal ASL scans acquired in 2.22 ± 1.43 years apart from 140 subjects from the Alzheimeŕs Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). At the baseline scan, the cohort contained 41 NC, 74 mild cognitive impairment patients (MCI), and 25 AD patients. 21 NC converted into MCI and 17 MCI converted into AD at the follow-up. Longitudinal CBF changes were assessed using paired-t test for non-converters and converters separately at each voxel and in the meta-ROI. Age and sex were used as covariates.

Results:

CBF reductions were observed in all subjects. Stable NC (n=20) showed CBF reduction in the hippocampus and precuneus. Stable MCI patients (n=57) showed spatially more extended CBF reduction patterns in hippocampus, middle temporal lobe, ventral striatum, prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum. NC-MCI converters showed CBF reduction in hippocampus and cerebellum and CBF increase in caudate. MCI-AD converters showed CBF reduction in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. CBF changes were not related with longitudinal neurocognitive changes.

Conclusion:

Normal aging and AD continuum showed common longitudinal CBF reductions in hippocampus independent of disease and its conversion. Disease conversion independent longitudinal CBF reductions escalated in the MCI.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral blood flow, longitudinal analysis, aging, arterial spin labeling

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by amyloid deposition and cognitive impairment [1, 2]. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) is a fundamental physiological measure, and reduced CBF (hypoperfusion) has been observed repeatedly in AD using neuroimaging [3, 4], suggesting AD-related neurovascular and neuronal dysfunctions. Hypoperfusion may even represent a major cause of AD pathology and subsequent cognitive decline [5]. Arterial spin labeling (ASL) perfusion MRI is a non-invasive technique for quantifying CBF without using exogenous tracers [6, 7]. It is relatively low-cost and can be repeated many times, therefore its use is highly appealing in longitudinal AD studies. ASL hypoperfusion patterns in MCI and AD subjects have been reported in [8–12]. While encouraging, most of these findings were based on cross-sectional data, longitudinal CBF changes in the AD population have not been under-studied. Based on ASL CBF data from a small sample size, Wang reported AD conversion and reversion-related CBF decrease and increase [13]. Also based on a small sample size, Staffaroni et al. [14] reported that individuals with MCI who later converted to AD had lower baseline perfusion in the precuneus, middle cingulum, inferior parietal and middle frontal cortices than non-converters. Examination of changes in longitudinal CBF and their association to disease progression is still lacking in the literature. The purpose of this study is to examine the longitudinal CBF changes in the course of disease progression using the large samples available from AD Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (adni.loni.usc.edu). To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first of its type published in the literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Data used were obtained from the ADNI database. ADNI was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), private pharmaceutical companies and non-profit organizations, as a $60 million, 5-year public private partnership. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), other biological markers, as well as clinical and neuropsychological assessments can be combined to measure the progression of MCI to early AD. The ADNI 2 (phase 2) includes a sub-study of ASL MRI for participants scanned on the Siemens 3T MRI platform (~ 1/3 of enrolled subjects). This multi-site study allows for the assessment of ASL MRI sensitivity to disease severity across the spectrum from cognitively normal adults, early and late mild cognitive impairment (EMCI, LMCI), and mild AD. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org. Subjects recruited in ADNI GO and ADNI II with MPRAGE and ASL-MRI images were included and the cohort included in this study contains 41 normal controls (NC); age: 72.9 ± 6.9 years (mean ± standard deviation), 74 MCI patients, age: 70.5 ± 7.0 years, and 25 AD patients, age: 72.0± 6.38 years. More detail of the demographic information can be found in the Table 1.

TABLE 1:

Demographic characteristics of study subjects

| NC | MCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 41 | 74 | 25 |

| Age (yrs) | 72.9±6.9 | 70.5±7.0 | 72±6.38 |

| Age range (yrs) | 60 – 85 | 56 – 85 | 61 – 82 |

| Female:Male | 25:16 | 43:31** | 15:10** |

| Years of education (SD) | 16.4±2.3 | 16.4±2.8 | 16.4±3.1 |

| mean GM CBF (ml /100 g/min) | 53.35±17.36 | 52.64±15.37 | 45.13±13.30 |

| MMSE | 27.10±7.76 | 25.85±7.95 | 23.56±5.77 |

means significantly different from controls.

Image acquisition

Both high-resolution structural MRI data and ASL-MRI data were downloaded. The structural images were acquired using a 3D MPRAGE T1-weighted sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE/TI = 2300/2.98/900 ms, 176 sagittal slices, within plane FOV = 256 × 240 mm2, voxel size = 1.1 × 1.1 × 1.2 mm3, flip angle = 9°, bandwidth = 240 Hz/pix. ASL data were acquired using the Siemens product 2D PICORE sequence, which is a pulsed ASL sequence using the Q2TIPs technique for defining the spin bolus [15]. The acquisition parameters were TR/TE = 3400/12 ms, TI1/TI2 = 700/1900 ms, FOV = 256 mm, 24 sequential 4 mm thick slices with a 25% gap between the adjacent slices, partial Fourier factor = 6/8, bandwidth = 2368 Hz/pix, and imaging matrix = 64 × 64.

ASL data processing

Similar to our previous study [10], a SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) based toolbox, ASLtbx [16,17] was used for preprocessing all MR images. The steps for processing ASL images include motion correction [17], temporal denoising, spatial smoothing, CBF quantification, outlier cleaning [18], partial volume correction, and spatial registration to the Montreal Neurology Institute (MNI) standard brain space. Temporal filtering was achieved by using a high-pass Butterworth filter (cutoff frequency = 0.01Hz) and temporal nuisance cleaning. Temporal nuisances including head motion time courses (3 translations and 3 rotations), and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) mean signal time course were regressed out from ASL image series at each voxel. CSF mask was defined during the T1-weighted structural image segmentation. Spatial smoothing was performed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel with a full-width-at-half-maximum of 6 mm. The preprocessed ASL label and control image pairs were then successively subtracted, and the control-label difference was converted into a quantitative CBF value using the one-compartment model included in ASLtbx. The detailed model parameters can be found in other references [19]. Quality assurance measures consisted of three different methods: 1) using the method proposed in [20], 2) subjects with CBF mapping out of the range of mean CBF ± 3*std were rejected. 20 AD patients’ CBF maps were rejected; and 3) three manual checks of the registration CBF images to the MNI space. The mean ASL image was registered to the high resolution structural T1 images using SPM 12. The corresponding registration transform was used to register the CBF maps into the structural MRI

Structural images were segmented into grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), and CSF using the segmentation tool provided in SPM12. These images were projected into the native ASL image space based on the registration correspondence between the mean ASL control image and the structural image; and they were subsequently used for extracting the CBF signals for temporal denoising and partial volume correction. The Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponential Lie Algebra (DARTEL) routine [19] implemented in SPM12 was used to generate a local template for all subjects based on their segmented GM and WM probability maps. The local template was registered into the MNI standard space using a linear affine transformation. With these two transformations, each individual subject’s brain was mapped into the MNI space. The slice-wise adaptive outlier cleaning algorithm [17] was applied to the resulting CBF time series. Partial volume effect (PVE) correction was performed at each voxel in the GM using a previously described approach. The PVE corrected CBF map was then registered into the structural image space using the same registration transformation from the mean ASL control image to the structural image described above. The meta-region-of-interest (meta-ROI) identified by Landau et al. [21] was used to extract mean CBF in the temporal parietal regions which have been shown to be sensitive to AD-related CBF changes [10,22].

Statistical analysis

Table 1 shows the demographic information, whereby the group differences were determined by X2 for sex and 2 sample t-tests for continuous variables. The values are shown in the form of mean±SD. Only sex was significantly different between the patients and NC. Additionally, Pearson correlation was computed between the change of meta-ROI and the change of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (This score was selected based on the closest in date to the date of acquisition for the ASL-MRI images.)

Subjects were classified into two categories based on their disease diagnosis results at each time scan timepoint using the clinical assessment data obtained at the date close to the image data acquisition date: 1) non-converters: subjects who did not have a change in diagnosis across all sessions (i.e., NC to NC, MCI to MCI, AD to AD), 2) converters: subjects whose diagnosis progressed beyond their baseline diagnosis (i.e., NC to MCI, or MCI to AD). Since only 5 AD subjects remained after ASL CBF image quality check, we did not run statistical analysis for the AD to AD subgroup. Paired-t test as implemented in SPM12 was used to assess the longitudinal CBF difference at the two scan dates at each voxel and for each subgroup separately. Sex, age, and education were included as covariates. A voxelwise statistical significance threshold was set to p<0.001. The Monte Carlo simulation-based cluster size estimation was used for correcting the multiple comparisons [23]. For visualization, BSPVIEW [24] was used.

Mean metaROI CBF was extracted and compared across time for each group of subjects. Neurocognitive decline was assessed by MMSE, working memory (the LIMMTOTAL (LIMM) and LDELTOTAL (LDEL) score), and daily function measure (the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ)). Longitudinal neurocognitive decline was examined with paired t-test for each group separately. Correlations between the longitudinal metaROI CBF change and the longitudinal neurocognitive score changes were calculated using Pearson correlation analysis. Sex and time difference between the two assessments was included as nuisance. Because hippocampus is pivotal to memory and has been frequently implicated in AD, we repeated the above analyses for the bilateral hippocampus mean CBF. The hippocampus was defined by the Wakeforest PickAtlas [25] and covers the entire hippocampus while the metaROI only contains a small sphere in the hippocampus.

RESULTS

Longitudinal CBF changes in non-converters

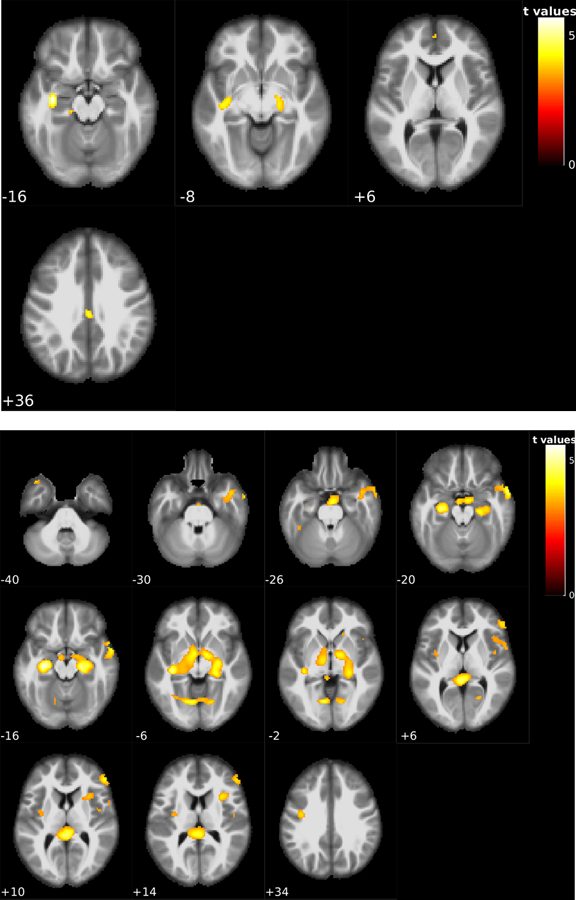

Fig. 1 shows the voxelwise longitudinal CBF difference for both stable NC and stable MCI patients. 20 stable NC subjects had two ASL scans within 2.45 ±1.50 years. Fig 1A shows the significant CBF changes in the stable NC. The threshold was t > 3.57 at a p < 0.001 and a cluster size > 57. CBF reduction was found in the right and left hippocampus and left fusiform gyrus. Furthermore, the meta-ROI CBF computed for this group was 52.4 ml/100 g / min and 51.86 ml ml/100 g /min in the first and last sessions, respectively.

Figure 1.

Voxel-wise statistical analysis results of the within-subject CBF changes in patients with no change of disease status at both assessed time points. CBF changes were marked with the red clusters. Figure 1-A is the longitudinal CBF reductions in the 20 non-converter NC subjects; significant CBF reduction was found in the left and right hippocampus and left fusiform gyrus. Figure 1-B shows the longitudinal CBF reductions in the 57 non-converter MCI patients; significant reduction of CBF was found on left and right hippocampus, left and right cerebellum, basal ganglia, and left fusiform gyrus. The number underneath each image slice indicate the slice location in the MNI standard brain space.

Time difference between the two ASL scans for the 57 stable MCI patients was 2.18 ±1.43 years. Fig. 1B shows their significant longitudinal CBF changes. The voxel-wise statistical significance threshold was t > 3.24 at a p < 0.001. The cluster size threshold was 57. Significant CBF reduction was found in left and right hippocampus, left and right cerebellum, basal ganglia, and left fusiform gyrus. The meta-ROI CBF for this group had a mean of 53.35 ml ml/100 g/min and 51.20 ml /100 g/min in the first and last sessions, respectively.

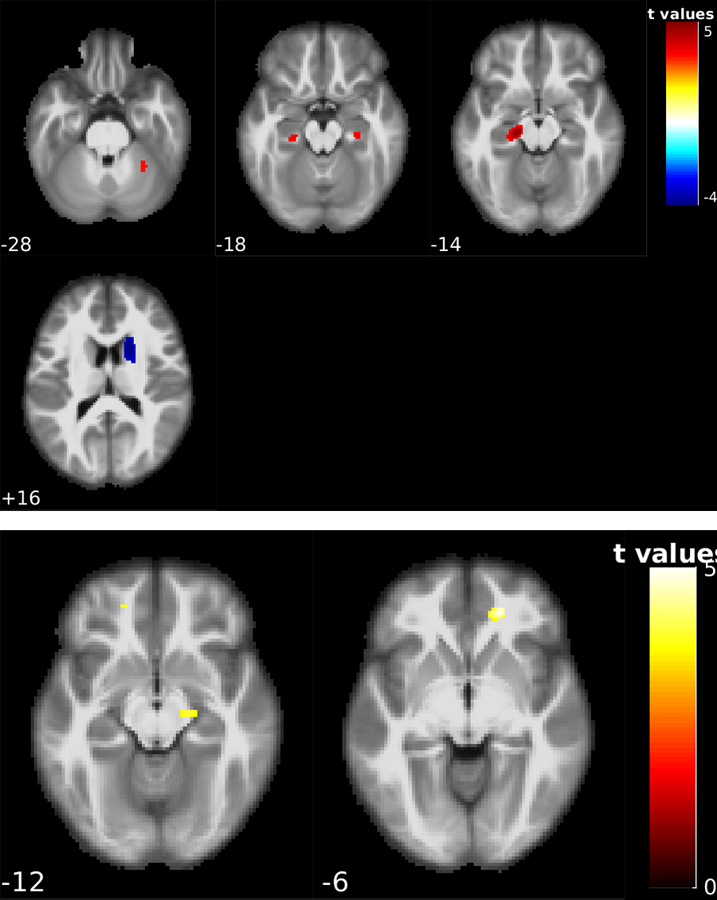

Longitudinal CBF changes in converters

Fig. 2 shows the voxelwise longitudinal CBF difference for the converters: NC to MCI and MCI to AD. 21 NC to MCI converters had two ASL scans within 3.00 ±1.18 years. Fig 2 A shows the significant longitudinal CBF changes in the NC to MCI converters at the statistical significance level of t > 3.55 at a p < 0.001 and a cluster size > 57. A reduction of CBF was found in the left and right hippocampus, right cerebellum, and an increase of CBF was found in the right putamen and right caudate nucleus. The meta-ROI CBF for this group showed a mean of 56.84 ml/100 g/min and 54.80 ml /100 g/min in the first and last sessions, respectively. No significant difference was observed (p-value = 0.42).

Figure 2:

Voxel-wise statistical analysis results for the converter groups. Figure 2-A shows the CBF change patterns in the 21 NC to MCI converters; significant reduction of the CBF was found on the left and right hippocampus, right cerebellum, and an increase in CBF in the right putamen and right caudate nucleus. Figure 2-B shows the CBF change patterns for 17 MCI to AD converters; significant CBF reduction was found in the right hippocampus and right superior orbital gyrus. The number underneath each image slice indicate the slice location in the MNI standard brain space.

17 MCI to AD converters had two ASL MRI scans within 1.71 ±1.26 years. Fig. 2B shows the longitudinal CBF changes defined by a statistical threshold of t > 3.6861 at a p < 0.001 and a cluster size > 57. Longitudinal CBF reduction was found in the right hippocampus and right superior orbital gyrus.

Table 2 lists the mean CBF of the metaROI for each subgroup at both baseline and the followup time. Table 3 lists the mean CBF of bilateral hippocampus for each subgroup at both baseline and the followup. Hippocampus ROI was defined by the PickAtlas. Longitudinal CBF reduction in the stable MCI patients was statistically significant in both metaROI and the hippocampus ROI, resulted in a significant longitudinal CBF reduction in both ROIs in the entire group.

TABLE 2:

Meta-ROI CBF in the baseline and the second time point

| Group | N | CBF at baseline | CBF at second time point | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC to NC | 20 | 53.35 (17.58) | 51.23 (15.14) | 0.69 |

| MCI to MCI | 57 | 54.72 (16.55) | 50.72 (15.99) | 0.19 |

| NC to MCI | 21 | 57.97 (17.60) | 54.00 (13.68) | 0.42 |

| MCI to AD | 17 | 45.70 (7.23) | 43.50 (13.19) | 0.55 |

| All Subjects | 115 | 53.74 (16.16) | 50.34 (15.19) | 0.10 |

Values were shown in the format of mean and standard deviation in the parenthesis. CBF is in the unit of ml/100 g/min. N represents the number of subjects in each group after the remove of outliers.

TABLE 3:

Hippocampal CBF in the baseline and the second time point

| Group | N | CBF at baseline (ml/100 g/min) |

CBF at second time point (ml/100 g/min) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC to NC | 20 | 41.83 (10.54) | 40.19 (12.38) | 0.34 |

| MCI to MCI | 57 | 41.63 (9.04) | 37.11 (9.84) | 0.0002* |

| NC to MCI | 21 | 44.59 (12.15) | 38.51 (8.02) | 0.06 |

| MCI to AD | 17 | 39.09 (7.14) | 37.54 (10.19) | 0.38 |

| All Subjects | 115 | 41.83 (9.71) | 37.97 (10.02) | 2.48x10−5** |

and ** indicate statistically significant results defined by p<0.05. Values were shown in the format of mean and standard deviation in the parenthesis. CBF is in the unit of ml/100 g/min. N represents the number of subjects in each group after the remove of outliers.

Stable NC (NC-NC) showed significant longitudinal memory decline as measured by LIMM (p=0.04) and LDEL (p=0.003). Stable MCI patients showed significant memory decline (LIMM, p=0.02; LDEL, p=0.0002) and significant daily function impairment as measured by FAQ (p=0.0005). NC-MCI converters showed significant longitudinal memory decline (LIMM, p=0.05). MCI-AD converters showed significant memory decline (LDEL, p=1.4e-6) and FAQ decline (p=0.001). Longitudinal CBF changes were not related to longitudinal neuro-cognitive decline in any group (p>0.1).

DISCUSSION

We examined longitudinal CBF changes in normal aging, and patients in the AD continuum. In subjects without disease progression (non-converters), statistically significant longitudinal CBF reduction was observed in the hippocampus and cerebellum in both stable NC and MCI subjects. In subjects with disease status change at the second timepoint (converters), CBF reduction was found in the left and right hippocampus and right cerebellum in NC subjects who converted to MCI. MCI to AD converters showed CBF reduction in the right hippocampus and in the right superior orbital gyrus. No significant longitudinal changes were observed in the grey matter mean CBF and the meta-ROI mean CBF in all populations. Change of mean grey matter CBF or meta-ROI CBF was not significantly related to the change of neurocognitive changes as measured by MMSE, working memory indices, and FAQ.

Cross-sectional studies [26] have suggested longitudinal CBF reductions occur in aging and AD. Our data provide direct evidence of the longitudinal CBF changes in hippocampus in both healthy elderly and AD patients with or without disease progression. The hippocampus is a pivotal region for both aging and AD as it is the major region involved in episodic memory. Hippocampal CBF reduction overserved in both non-converters and converters suggests a disease independent hippocampal function decline during the progressive aging process. Cross-sectional studies have suggested larger longitudinal hippocampal CBF reductions in the AD continuum than in normal aging [4,10], in line with the hallmark fast memory decline in AD. One reason for missing the disease related longitudinal CBF could be the limited sample size in the converter groups. In the current study, the stable MCI group had the largest sample size and their longitudinal CBF reduction patterns appeared to be the largest among all four groups. Another reason could be the symptom progression heterogeneity. Even for the “stabilized” NC and MCI patients, we still found significant memory decline and daily function decline at the second scan time. In other words, some of the nonconverter NC and MCI might be better grouped into converters or early converters as also suggested by the AD subtyping concept [27]. In addition to the hippocampus, aging-related CBF reduction (the time effect) was demonstrated in both normal elderly and MCI in other regions, including the medial prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, and ventral striatum. The medial prefrontal cortex and cingulate are involved in memory and decision making [28]. Reduction of CBF, seen over time, in the medial prefrontal cortex may be related to aging-related memory and decision making decay. Hypoperfusion in cingulate was consistent with an early SPECT imaging study [29], where cingulate hypoperfusion was found to be predictive of AD. Cingulate is involved in self-referencing [30], which is related to memory. Hypoperfusion in cingulate cortex in aging and MCI may indicate impairments of self-referencing function. The “stable” MCI group showed longitudinal hypoperfusion in ventral striatum, indicating an impairment of reward information processing and motor function in MCI since ventral striatum is pivotal to those brain functions and has been reported to be affected in aging and AD [31, 32, 33].

Hypoperfusion was observed in the lateral striatum in the putamen and temporal cortex after patients converted to MCI from normal aging. However, this pattern was diminished in the MCI to AD conversion group. While we do not know the exact reason for this discrepancy, one reason may be the small number of patients included in the MCI to AD conversion group. Disease severity-related CBF reduction in the parietal cortex, precuneus, and temporal cortex was reported in a previous ADNI ASL study [10]. In our current study, we did not find a hypoperfusion pattern in the parietal cortex and precuneus. Future studies are needed to investigate this discrepancy.

No significant correlation was found between the longitudinal CBF change and the longitudinal neurocognitive decline in either the nonconverters or the converters. While this result may suggest a non-linear relationship between the longitudinal CBF change and the longitudinal neurocognitive changes, it may also be caused by the large population heterogeneity as we mentioned above and the relatively low signal-to-noise-ratio of the PASL sequence used in ADNI II ASL data acquisitions.

Hypoperfusion patterns in MCI and AD detected by ASL CBF have been shown to be comparable to hypo-metabolism patterns detected by PET-FDG [22,34,35]. Cerebral metabolism rate of glucose (CMRglu) measured by PET has been long postulated to progressively decline as the disease progresses [36]. A future important study could be assessing the longitudinal CMRglu decline in the same groups as included in this paper or combining ASL CBF and PET-FDG CMRglu for better delineating the longitudinal brain vs behavioral relationship.

Several limitations have been discussed above, including the relatively small sample size in three of the four groups, the relatively low signal-to-noise-ratio of the ADNI PASL data, and the neurocognitive progression inheterogeneity in each group. Larger sample size may be available when more ADNI data will be released. High quality ASL data are available from ADNI phase III study but there were few subjects who had converted from NC to MCI or from MCI to AD by the time we performed this study. Group subtyping is possible when larger cohort is available. This study was also limited in terms of lack of AD pathology analysis. We did not include longitudinal AD pathological data as few subjects had the data at both time points and AD pathology may not be sensitive to detect longitudinal neurocognitive decline [37,38,39,40]. Another limitation is the unclear caffeine intake information at both the baseline scan and the followup scan. The ADNI patient enrollment excluded the use of antihypertensive agents and benzodiazepines but it is unclear for whether caffeine intake was controlled at each imaging date. Previous studies have shown that caffeine can cause transient acute CBF reductions [41,42]. It is possible that part of the longitudinal CBF reduction might be contributed by caffeine intake difference between the two timepoints.

Conclusion

Using ADNI longitudinal ASL data, we found consistent longitudinal CBF reduction in the hippocampus in normal aging and in the progression of AD. Also, striatal CBF changes were found in the progression of NC to MCI, suggesting this is a sign of early disease progression and may be used as an additional biomarker for early disease detection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH/NIA Grant R01AG060054. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuroimaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

CONFLICT OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- [1].Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH (2011) Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7, 280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R; Contributors (2018) NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Alsop DC, Detre JA, Grossman M (2000) Assessment of cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer’s disease by spin-labeled magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 47, 93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wolk DA, Detre JA (2012) Arterial spin labeling MRI: an emerging biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative conditions. Curr Opin Neurol 25, 421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zlokovic BV, Deane R, Sallstrom J, Chow N, Miano JM (2005) Neurovascular pathways and Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide. Brain Pathol 15, 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Williams DS, Detre JA, Leigh JS, Koretsky AP (1992) Magnetic resonance imaging of perfusion using spin inversion of arterial water. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89, 212–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992. May 1;89(9):4220. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP (1992) Perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med 23, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Du AT, Jahng GH, Hayasaka S, Kramer JH, Rosen HJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rankin KP, Miller BL, Weiner MW, Schuff N (2006) Hypoperfusion in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease by arterial spin labeling MRI. Neurology 67, 1215–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Johnson NA, Jahng GH, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Chui HC, Jagust WJ, Gorno-Tempini ML, Schuff N (2005) Pattern of cerebral hypoperfusion in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment measured with arterial spin-labeling MR imaging: initial experience. Radiology 234, 851–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wang Z, Das SR, Xie SX, Arnold SE, Detre JA, Wolk DA; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2013) Arterial spin labeled MRI in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: A multi-site study. Neuroimage Clin 2, 630–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang Q, Stafford RB, Wang Z, Arnold SE, Wolk DA, Detre JA (2012) Microvascular perfusion based on arterial spin labeled perfusion MRI as a measure of vascular risk in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 32, 677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Alexopoulos P, Sorg C, Förschler A, Grimmer T, Skokou M, Wohlschläger A, Perneczky R, Zimmer C, Kurz A, Preibisch C. (2012) Perfusion abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia in Alzheimer’s disease measured by pulsed arterial spin labeling MRI. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 262, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang Z (2016) Longitudinal CBF changes predict disease conversion/revision in AD and MCI. The 22nd Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping, Geneva, Switzerland, #1009. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Staffaroni AM, Cobigo Y, Elahi FM, Casaletto KB, Walters SM, Wolf A, Lindbergh CA, Rosen HJ, Kramer JH (2019) A longitudinal characterization of perfusion in the aging brain and associations with cognition and neural structure. Hum Brain Mapp 40, 3522–3533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Luh WM, Wong EC, Bandettini PA, Hyde JS QUIPSS (1999) II with thin-slice TI1 periodic saturation: a method for improving accuracy of quantitative perfusion imaging using pulsed arterial spin labeling. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.; 41:1246–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang Z, Aguirre GK, Rao H, Wang J, Fernández-Seara MA, Childress AR, Detre JA (2008) Empirical optimization of ASL data analysis using an ASL data processing toolbox: ASLtbx. Magn Reson Imaging 26, 261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang Z (2012) Improving Cerebral Blood Flow Quantification for Arterial Spin Labeled Perfusion MRI by Removing Residual Motion Artifacts and Global Signal Fluctuations Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 30(10):1409–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li Y, Dolui S, Xie DF, Wang Z; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2018) Priors-guided slice-wise adaptive outlier cleaning for arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI. J Neurosci Methods 307, 248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, Siewert B, Warach S, Edelman RR (1998) A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 40, 383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dolui S, Wang Z, Shinohara RT, Wolk DA, Detre JA; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2017) Structural Correlation-based Outlier Rejection (SCORE) algorithm for arterial spin labeling time series. J Magn Reson Imaging 45, 1786–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Jack CR Jr, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ, & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2010). Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology, 75(3), 230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chen Y, Wolk DA, Reddin JS, Korczykowski M, Martinez PM, Musiek ES, Newberg AB, Julin P, Arnold SE, Greenberg JH, & Detre JA (2011). Voxel-level comparison of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI and FDG-PET in Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 77(22), 1977–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub/dist/doc/program_help/3dClustSim.html.

- [24].Spunt Bob. (2016, November 22). spunt/bspmview: BSPMVIEW v.20161108 (Version 20161108). Zenodo. Accessed on January 5, 2021

- [25].WFU_PickAtlas. https://www.nitrc.org/projects/wfu_pickatlas/. Last updated April 23, 2015. Accessed on March 1, 2021.

- [26].Perry RJ, Hodges JR (1999) Attention and executive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. A critical review. Brain 122, 383–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Murray ME, Graff-Radford NR, Ross OA, Petersen RC, Duara R, Dickson DW. (2011) Neuropathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease with distinct clinical characteristics: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 10:785–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gutchess AH, Welsh RC, Boduroglu A, Park DC (2006) Cultural differences in neural function associated with object processing. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 6, 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Huang C, Wahlund LO, Svensson L, Winblad B, Julin P. (2002) Cingulate cortex hypoperfusion predicts Alzheimer’s disease in mild cognitive impairment. BMC Neurol 2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Haber SN (2011) Neuroanatomy of Reward: A View from the Ventral Striatum. In: Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward, Gottfried JA, editor. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL, Chapter 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dreher JC, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kohn P, Berman KF (2008) Age-related changes in midbrain dopaminergic regulation of the human reward system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 15106–15111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Gunning-Dixon F, Acker JD (2003) Differential aging of the human striatum: longitudinal evidence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 24, 1849–1856. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cho H, Kim JH, Kim C, Ye BS, Kim HJ, Yoon CW, Noh Y, Kim GH, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Kim CH, Kang SJ, Chin J, Kim ST, Lee KH, Na DL, Seong JK, Seo SW (2014) Shape changes of the basal ganglia and thalamus in Alzheimer’s disease: a three-year longitudinal study. J Alzheimers Dis 40:285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dolui S, Li Z, Nasrallah IM, Detre JA, & Wolk DA (2020). Arterial spin labeling versus 18F-FDG-PET to identify mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage. Clinical, 25, 102146.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Musiek ES, Chen Y, Korczykowski M, Saboury B, Martinez PM, Reddin JS, Alavi A, Kimberg DY, Wolk DA, Julin P, Newberg AB, Arnold SE, & Detre JA (2012). Direct comparison of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 8(1), 51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kuwabara Y, Ichiya Y, Ichimiya A, Sasaki M, Akashi Y, Yoshida T, Fukumura T, & Masuda K (1994). Kaku igaku. The Japanese journal of nuclear medicine, 31(10), 1255–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee HG, Casadesus G, Zhu X, Takeda A, Perry G and Smith MA (2004). “Challenging the amyloid cascade hypothesis: senile plaques and amyloid-beta as protective adaptations to Alzheimer disease.” Ann N Y Acad Sci 1019: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tse KH and Herrup K (2017). “Re-imagining Alzheimer’s disease - the diminishing importance of amyloid and a glimpse of what lies ahead.” J Neurochem 143(4): 432–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhu X, Lee HG, Perry G and Smith MA (2007). “Alzheimer disease, the two-hit hypothesis: an update.” Biochim Biophys Acta 1772(4): 494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zlokovic BV (2011). “Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders.” Nat Rev Neurosci 12(12): 723–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Deibler AR, Pollock JM, Kraft RA, Tan H, Burdette JH, & Maldjian JA (2008). Arterial spin-labeling in routine clinical practice, part 2: hypoperfusion patterns. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology, 29(7), 1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ge Q, Peng W, Zhang J, Weng X, Zhang Y, Liu T, Zang YF, Wang Z. (2017). Short-term apparent brain tissue changes are contributed by cerebral blood flow alterations. PLoS One.; 12(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]