Abstract

Objectives:

Refractory post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCS) complicating cardiac surgery yields nearly 100% mortality when untreated. Use of veno-arterial (V-A) extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for PCS has increased worldwide recently. The aim of the current analysis was to outline the trends in use, changing patient profiles, and in-hospital outcomes including complications in patients undergoing V-A ECMO for PCS.

Design:

Analysis of Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry from January 2010 through December 2018.

Setting:

multicenter worldwide registry.

Patients:

7,185 patients supported with V-A ECMO for PCS.

Interventions:

V-A ECMO.

Measurements and main results:

Hospital death, weaning from ECMO, hospital complications. Mortality predictors were assessed by multivariable logistic regression. Propensity score matching was performed for comparison of peripheral and central cannulation for ECMO. A significant trend toward more ECMO use in recent years (coef.:0.009; p<0.001) was found. Mean age was 56.3±14.9 years and significantly increased over time (coef.:0.513; p<0.001). Most commonly, V-A ECMO was instituted after coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) (26.8%) and valvular surgery (25.6%), followed by heart transplantation (20.7%). Overall, successful ECMO weaning was possible in 4,520 cases (56.4%), and survival to hospital discharge was achieved in 41.7% of cases. In-hospital mortality rates remained constant over time (coef.:−8.775;p=0.682) while complication rates were significantly reduced (coef.:−0.009;p=0.003). Higher mortality was observed after CABG (65.4%), combined CABG with valve (68.4%), and aortic (69.6%) procedures than other indications. Lower mortality rates were observed in heart transplantation recipients (46.0%). Age (P<0.001), central cannulation (P<0.001) and occurrence of complications while on ECMO were independently associated with poorer prognosis.

Conclusions:

The analysis confirmed increased use of V-A ECMO for PCS. Mortality rates remained relatively constant over time despite a decrease in complications, in the setting of supporting older patients.

Keywords: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, extracorporeal life support, postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock

Introduction

Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (V-A ECMO) represents a well-established life-saving procedure for refractory acute cardiac or cardiorespiratory insufficiency [1,2]. Its use in post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock (PCS) has exponentially increased in recent years, despite high associated mortality [3,4]. The severity of the patients’ underlying disease, together with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), predisposes to complications, which negatively impacts survival. While several reports suggested lower mortality when implemented early and in selected patients [5], other reports have shown the opposite.

V-A ECMO for PCS has represented the main indication for ECMO use and differs from other applications of ECMO in several respects [8–10]. Limited experience in these procedures, particularly in centers without well-established ECMO programs or without heart transplant or long-term mechanical circulatory support facilities, may impact patient outcomes [11].

Due to the increased use, complex patient management and resource intensity of PCS-related ECMO, careful evaluation of patient attributes, complication rates and in-hospital outcomes across a large accumulated experience should meaningfully inform the role of ECMO in this setting.

We utilized a patient registry reflecting the initial efforts at PCS V-A ECMO to the present day to outline the trends in use, changing patient profiles, and in-hospital outcomes including complications in patients undergoing V-A ECMO for PCS.

Methods

The ELSO registry is a voluntary registry with more than 430 centers worldwide contributing data, including information on pre-ECMO implant patient profile, use, complications, and in-hospital outcomes in adults and children undergoing temporary ECMO support [6,7,10]. To best account for changing technology and ECMO management, information present in the ELSO registry from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2018 were considered and retrospectively analyzed. Patient diagnoses were reported using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Edition codes. In this registry, indications for ECMO support are categorized as “cardiac,” “respiratory,” or “extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation” (ECPR).

Study Population

Data on patients more than 18 years old undergoing a single run V-A ECMO for refractory PCS were extracted. Indications for ECMO consisted of intra-operative failure to wean from CPB due to right, left or biventricular failure, and post-operative refractory cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest during the hospitalization after the surgical procedure. Patients with pre-operative ECMO were excluded from the analysis, as were patients undergoing more than one ECMO run. IRB approval was waived due to the retrospective design of the study and anonymous patient records in the registry. Informed consent was obtained as per regulations in the participating centers.

Main Goals and Definitions

We aimed to describe the trends of V-A ECMO for PCS, including perioperative morbidity as well as mortality, specifically attempting to identify factors associated with hospital death and weaning from ECMO. All complications were categorized using ELSO registry complication codes and included the following: 1) limb complications, 2) central nervous system complications, 3) bleeding complications, 4) kidney injury, and 5) sepsis. These categories were then further subdivided, as appropriate. We declared post-operative: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, cardiac tamponade, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, mediastinal bleeding, culture-proven sepsis, limb amputation or fasciotomy for ischemia, pump or oxygenator failure, severe hemolysis, brain death, diffuse brain ischemia or hemorrhage, pulmonary hemorrhage and renal replacement therapy as major complications. Definition of cardiogenic shock together with pertinent definitions for indications to ECMO support are ones adopted by attending physicians. The endpoint definitions are appended in Supplementary Table 1, where applicable.

Statistical analysis

We compared in-hospital survivors and non-survivors and used the Shapiro–Wilk test for testing of normality of continuous variables. All variables were analyzed with descriptive and frequency analysis. Variables with missing data in more than 5% of the patients were excluded from analysis. The χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used to compare group differences for categorical variables. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and were reported as means with standard deviations (SDs). Complications occurring in both groups are reported as number (%) with corresponding odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). P <0.05 was considered significant. The Storey–Tibshirani multiple testing correction was used [12]. Variables that achieved P <0.2 in the univariable analysis were examined by using multivariable analysis with forward stepwise logistic regression to evaluate independent risk factors for in-hospital death and weaning from ECMO, considering 3 sets of variables: 1) pre-ECMO variables; 2) pre-ECMO- and on-ECMO variables; 3) pre-ECMO-, on-ECMO variables and on-ECMO complications. The performance of the multivariable model in predicting mortality was assessed by calculating a c-statistic for discrimination and by the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistics for calibration [13]. Receiver operating curves (ROC) were constructed for all models and compared according to DeLong [14]. Additionally, propensity score matching (PSM) was performed for the comparison of patients undergoing peripheral vs. central cannulation for ECMO; pre-ECMO variables were considered exclusively for PSM model. Detailed description of statistical methods is appended in supplementary material under “statistical analysis”. Propensity matched cohorts underwent further subgroup analysis, with estimated in-hospital death rates reported alongside. Annual mortality rates are reported as crude and adjusted for pre-ECMO variables following multilevel mixed effects Poisson regression for non-binary outcome. Missing data were addressed with artificial neural networks up to 5%. Statistical tests were performed in STATA MP version 13.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Trends in ECMO use, patient profiles and outcomes

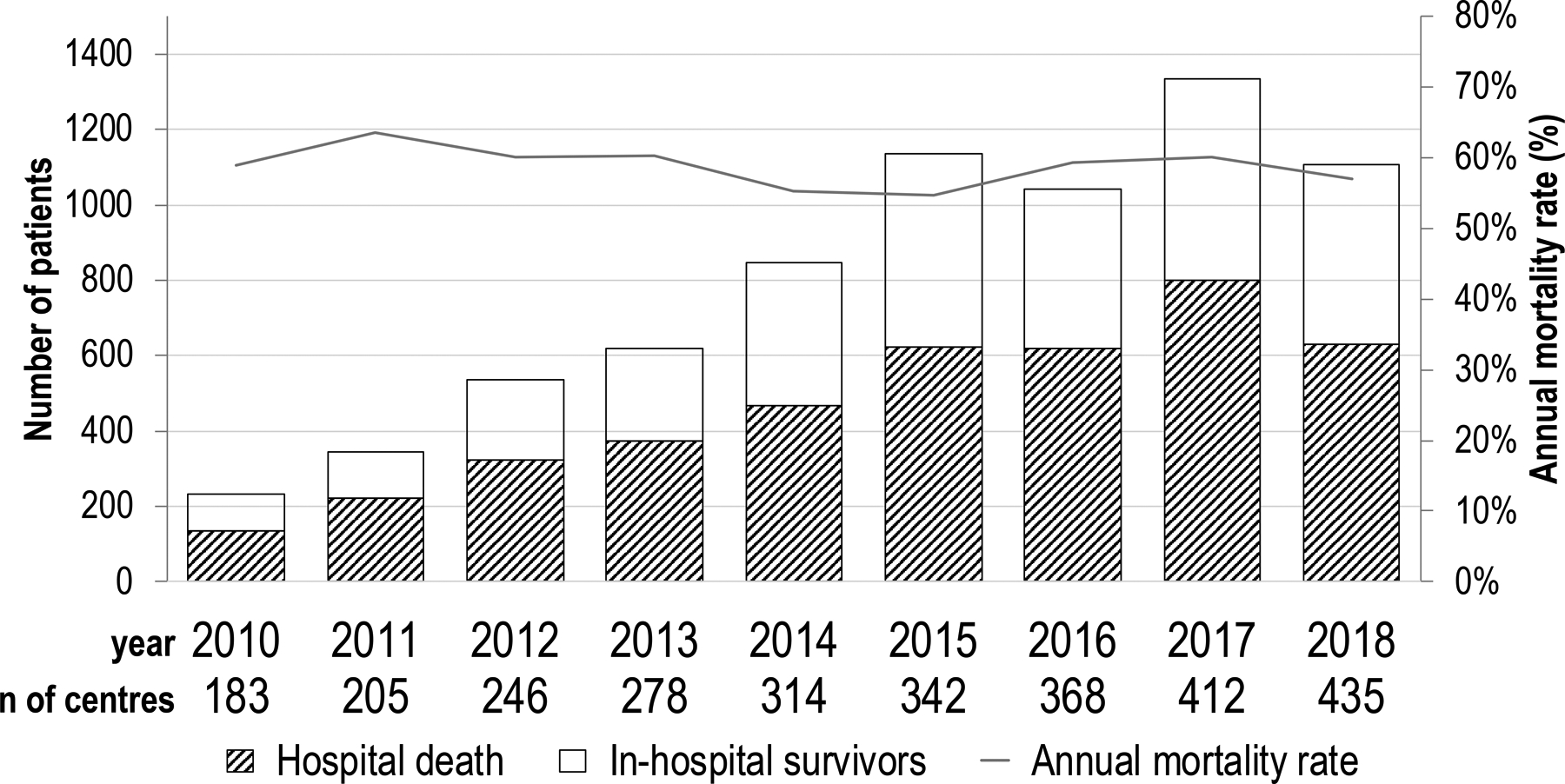

During the study period, 7,185 patients received V-A ECMO for PCS. Figure 1 demonstrate the trend in patient numbers initiated on V-A ECMO for PCS from the ELSO database with corresponding annual mortality rates. Annual mortality rates adjusted for pre-ECMO variables are available as Supplementary Table 2. In an unadjusted analysis, while there was a significant increase in the number of ECMO for PCS cases in recent years (coef.: 0.009; p<0.001), the mortality rate did not change significantly over time (coef.: −8.775; p=0.682). Mean age was 56.3±14.9 years (range, 18–86 years); patient distribution across age strata was evenly maintained. Yet, a significant trend (coef.: 0.444; p<0.001), for increasing average age was observed (Supplementary Figure 1). Pre-operative patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most commonly, patients were managed on ECMO for PCS after coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) (26.8%) and valvular surgery (25.6%), followed by heart transplantation (20.7%), combined surgeries, such as CABG with valve (13.4%), and ventricular assist devices (8.5%).

Figure 1.

Annual trend in the number of patients undergoing V-A ECMO and hospital death.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | Total (n=7,185) | Hospital survival (n=2,997) | Hospital death (n=4,188) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | ||||

| 18–38 | 921 (12.8) | 524 (56.9) | 397 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| 39–52 | 1,371 (19.1) | 644 (47.0) | 727 (53.0) | 0.002 |

| 53–62 | 1,895 (26.4) | 811 (42.8) | 1,084 (57.2) | <0.001 |

| 63–70 | 1,705 (23.7) | 625 (36.7) | 1,080 (63.3) | <0.001 |

| ≥71 | 1,293 (18.0) | 393 (30.4) | 900 (69.6) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4,852 (67.5) | 2,112 (43.5) | 2,740 (56.5) | <0.001 |

| Female | 2,333 (32.5) | 885 (37.9) | 1,448 (62.1) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 4,536 (63.1) | 1,892 (41.7) | 2,644 (58.3) | <0.001 |

| Black | 617 (8.6) | 281 (45.5) | 336 (54.5) | 0.002 |

| Asian | 997 (13.9) | 424 (42.5) | 573 (57.5) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 368 (5.1) | 136 (37.0) | 232 (63.0) | <0.001 |

| Other | 667 (9.3) | 264 (39.6) | 403 (60.4) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes melitus | 680 (9.5) | 252 (37.1) | 428 (62.9) | <0.001 |

| Uncontrolled hypertension | 1,022 (14.2) | 349 (34.1) | 673 (65.9) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 488 (6.8) | 163 (33.4) | 325 (66.6) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 142 (2.0) | 50 (35.2) | 92 (64.8) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 106 (1.5) | 36 (34.0) | 70 (66.0) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 78 (1.1) | 30 (38.5) | 48 (61.5) | 0.004 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 466 (6.5) | 163 (35.0) | 303 (65) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 697 (9.7) | 306 (43.9) | 391 (56.1) | <0.001 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 882 (12.3) | 288 (32.7) | 594 (67.3) | <0.001 |

| Unstable angina | 411 (5.7) | 162 (39.4) | 249 (60.6) | <0.001 |

| STEMIa | 380 (5.3) | 146 (38.4) | 234 (61.6) | <0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 669 (9.3) | 345 (51.6) | 324 (48.4) | 0.251 |

| Myocarditis | 43 (0.6) | 22 (51.2) | 21 (48.8) | 0.829 |

| Heart failure | 659 (9.2) | 263 (39.9) | 396 (60.1) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 301 (4.2) | 120 (39.9) | 181 (60.1) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 45 (0.6) | 27 (60.0) | 18 (40.0) | 0.055 |

| Bacterial endocarditis | 278 (3.9) | 129 (46.4) | 149 (53.6) | 0.089 |

| Cancer diagnosis | 91 (1.3) | 33 (36.3) | 58 (63.7) | <0.001 |

Last 90 days

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

ECMO implantation details are shown in Supplementary Table 3, together with blood gases and hemodynamic variables at ECMO implantation and 24-hours following implantation. The most frequent indication for V-A ECMO in this cohort was failure to wean from CPB. ECMO access was achieved by peripheral cannulation (54.1%) followed by central cannulation (45.9%); the combination of central arterial and peripheral venous cannulation was pooled as central cannulation strategies. Concomitant intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was used in 31.0%.

Patients were maintained on ECLS for a median duration of 144.7 ± 148.4 hours, with 136.5 ± 124.1 hours for in-hospital survivors, and 148.2 ± 163.4 hours for non-survivors (p=0.001). Successful weaning from ECMO was possible in 4,051 cases (56.4%). However, survival to hospital discharge was achieved in 41.7% (2,997/7,185) of cases.

Complications

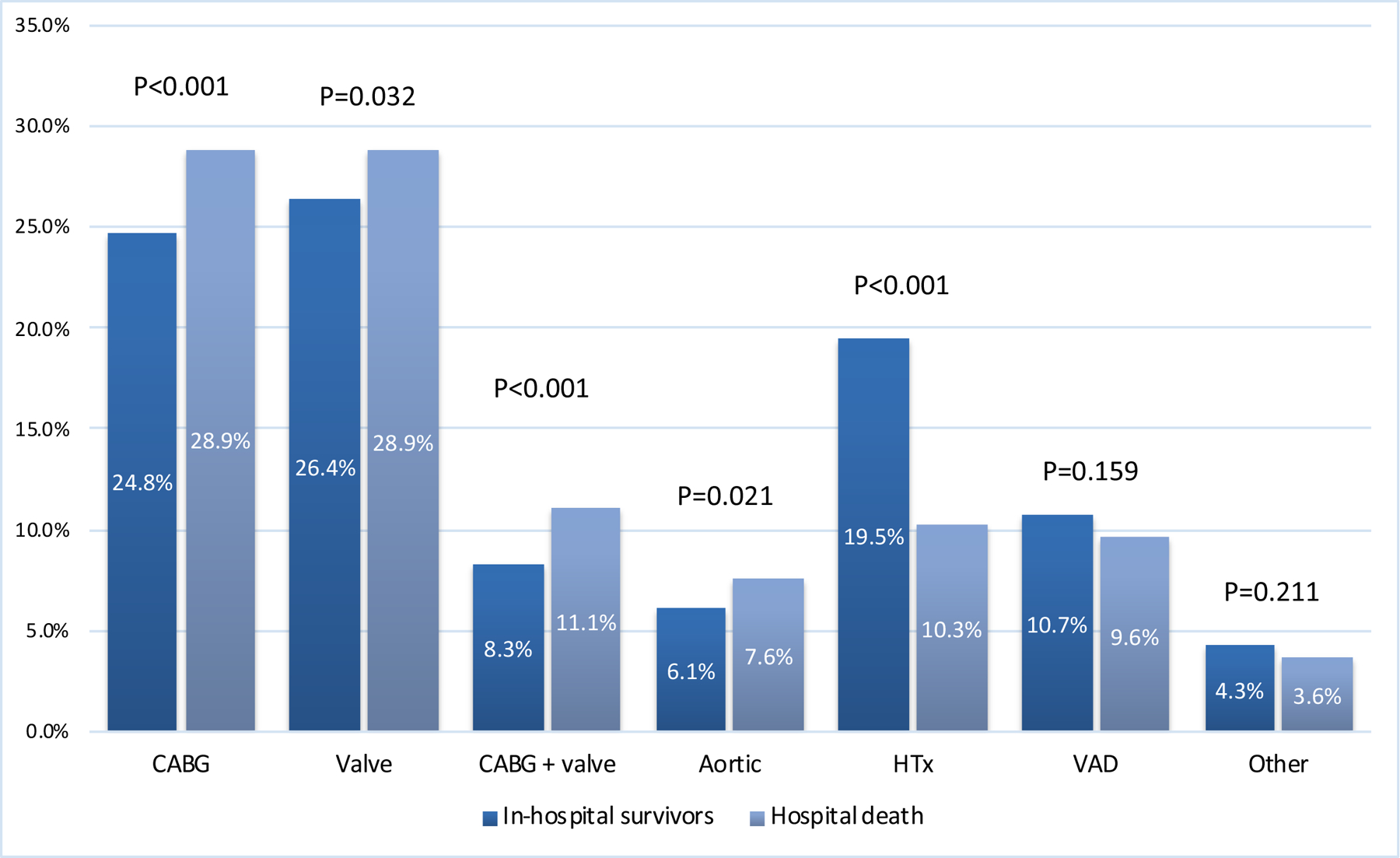

The use of PCS-ECMO was associated with numerous complications (Supplementary Table 4). Notwithstanding, the number of patients with major complications decreased in recent years (coef.: −0.009; p=0.003; Supplementary Figure 1). Overall, kidney failure (48.9%), surgical site bleeding (26.4%), cardiac arrhythmias (15.9%), sepsis (12.1%), metabolic disorders (26.9%) and neurologic complications (9.1%) were most common. When stratified by the type of primary surgery, higher mortality was observed after CABG (65.4%), combined CABG with valve 68.4%), and vascular aortic (69.6%) procedures in contrast to mortality rates among patients requiring V-A ECMO following heart transplantation with crude mortality rate of 46.0%.

Multivariable analysis

Older age was significantly associated with hospital death (Table 2). In particular, of 1,293 patients over 70 years of age, 69.6% (900) did not survive to discharge (p<0.001; Table 1) as compared to those ≤70 years-old (55.0% [3,288/5,892]). In the model taking into account exclusively pre-ECMO variables, initial pH, PO2, HCO3, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, CABG, heart transplantation, and thoracic aorta aneurysm were all independently associated with hospital death (Table 2). Supplementary Table 5 shows the predictors of hospital death further stratified by pre-ECMO- and on-ECMO variables. When on-ECMO complications were added (Supplementary Table 6), the accuracy of the model increased (Supplementary Figure 2). Arterial pH at 24 hours after initiation of ECMO was a strong predictor of death in this setting (P<0.001). Additionally, DIC (P<0.001), GI bleeding (P=0.002), hemolysis (P=0.010), neurological complications (P<0.001) and CRRT (P<0.001), were all associated with worse prognosis. Variables independently associated with weaning from ECMO are reported in Supplementary Table 7–9.

Table 2.

Multivariable predictors of hospital death (binary logistic regression). Pre-ECMO variables.

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | OR | Lower CI | Upper CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.024 | 0.002 | 1.024 | 1.020 | 1.028 | <0.001 |

| Initial pH | −3.793 | 0.506 | 0.061 | 0.023 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| Initial PO2 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 1.003 | 1.002 | 1.002 | <0.001 |

| Initial HCO3 | −0.047 | 0.009 | 0.971 | 0.954 | 0.938 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.349 | 0.101 | 1.730 | 1.418 | 1.163 | 0.001 |

| CKD | 0.272 | 0.137 | 1.717 | 1.313 | 1.004 | 0.047 |

| CABG | 0.293 | 0.082 | 1.573 | 1.340 | 1.141 | <0.001 |

| Heart transplantation | −0.542 | 0.101 | 0.709 | 0.582 | 0.477 | <0.001 |

| Thoracic aorta aneurysm | 0.706 | 0.307 | 3.698 | 2.025 | 1.109 | 0.022 |

SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

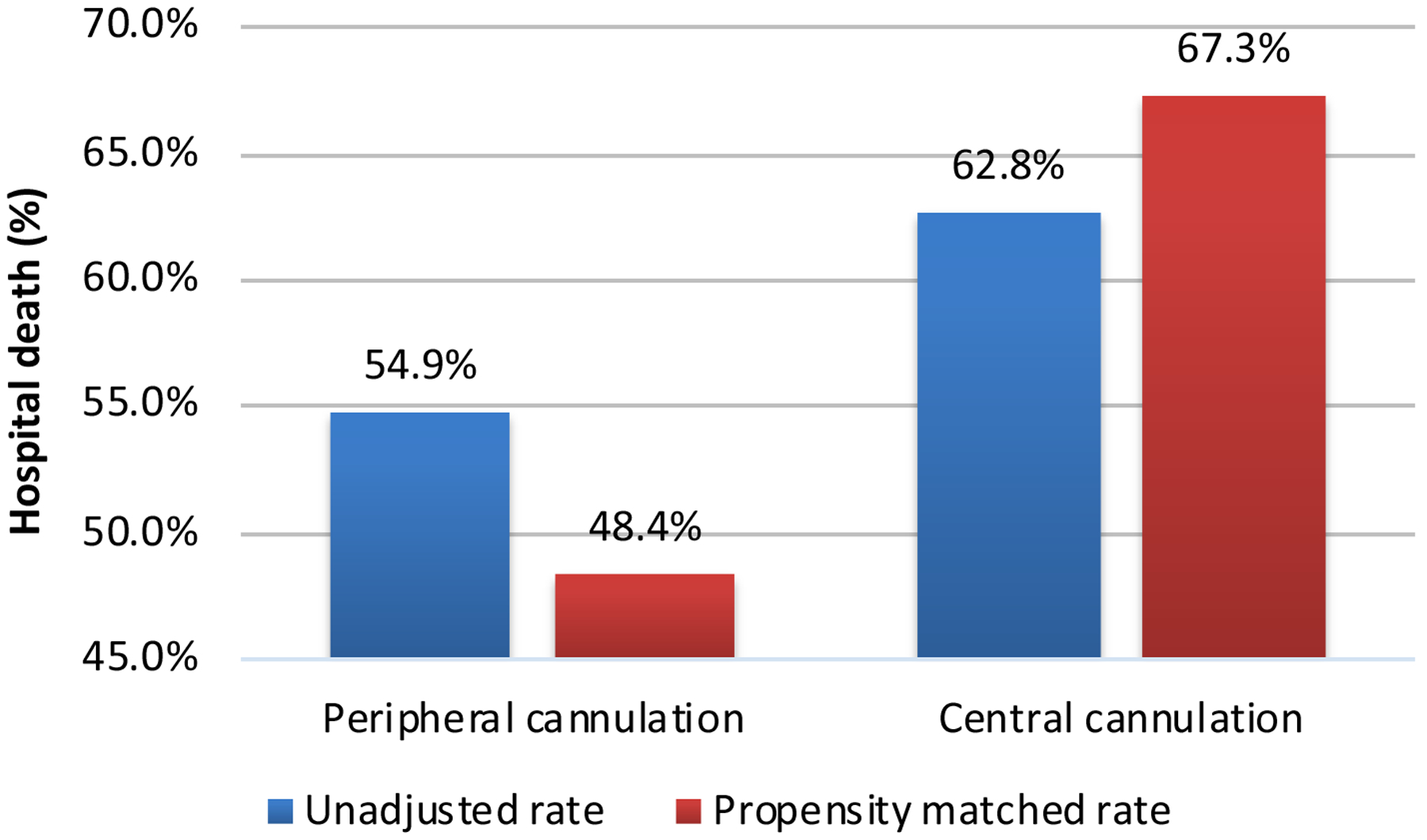

Peripheral vs central cannulation

Peripheral cannulation was shown in the overall multivariable model to be associated with lower in-hospital mortality (Supplementary Table 5 and Figure 3); unadjusted OR: 0.87; 95%CIs: (0.84–0.90); P<0.001. Propensity score matching was performed for the analysis stratified according to cannulation technique accounting exclusively for pre-ECMO variables: Supplementary Tables 10 and 11 list the baseline patients- and ECMO characteristics; Supplementary Table 12 lists propensity scores. In-hospital mortality odds after matching were over 50% reduced in the peripheral cannulation group: OR: 0.48; 95%CIs: (0.40–0.58); P<0.001 (Figure 3); odds of weaning from ECMO: 2.07 (1.72–2.48); P<0.001. Remaining ORs for hospital death stratified by subgroups are further available as Supplementary Table 13.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted and propensity score matched analysis of peripheral vs central cannulation and the endpoint of hospital death.

Discussion

Change in trends of V-A ECMO use

The use of temporary mechanical circulatory support including V-A ECMO is increasing but is often used as a last resort for patients who might otherwise die [3,4]. In the United States, PCS and shock complicating ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI) were the two most frequent indications for V-A ECMO implantation until 2012 [15]. The European and American Societies of Cardiology guideline recommendations assigned ECMO the class recommendation IIb, level of evidence C, for the management of cardiogenic shock in STEMI [16]. Despite the above recommendation, in-hospital ECMO outcomes have not shown substantial improvement [6,15]. Little is still known of who benefits most from ECMO, or the cost-effectiveness of such a resource-intense therapy [4]. The inherent features of ECMO in terms of quick availability, relative ease of application and reliability, have made it an attractive option, particularly in the PCS setting [1,2]. In contrast, although the implantable or para-corporeal ventricular assist devices (VAD) have been applied in these circumstances, their complexity, lack of associated lung support, cost, and limited availability have hampered their wider application, making V-A ECMO the most frequent temporary mechanical circulatory support in these circumstances [17].

Numerous publications have shown ECMO-related short- and medium-term outcomes [2,3]. While several large-scale registries have addressed the safety and efficacy of V-A ECMO in the setting of cardiogenic shock [6,18], specific reports about post-cardiotomy ECMO in acquired and congenital cardiac surgery patients, have usually been limited to single center reports only [19,20]. The characteristics of ECMO implantation (patient profiles, surgical access or location of implantation, timing of application, and duration of support), complications, and outcomes in the post-cardiotomy ECMO setting are different than in other applications of ECMO [21–26].

Change in approach to V-A ECMO

Cardiac surgical patients are often characterized by substantial pre-ECMO comorbidities, prolonged ECMO support, and more advanced age than in other ECMO populations [27–29]. Prolonged V-A ECMO duration may be associated with an increased morbidity and mortality [29–32]. Notably, a trend towards worsened survival rates, reaching a low of 15% in 2016 was recently reported in another analysis of the ELSO registry, including both adult and pediatric patients [6]. Similarly, the largest report to date on MCS use after cardiac surgery demonstrated a steadily increasing trend in the use of mechanical circulatory support other than IABP [4]. However, mortality rates were higher in recent years [4]. According to Flecher et al, [33] worse outcomes among post-cardiotomy ECMO patients was clearly demonstrated. Although this may be due, at least in part, to more widespread application of this technology to higher risk patients, this underlines the high complexity of PCS-ECMO patients.

Change in mortality

Our study demonstrates a trend toward an increasing number of ECMO procedures in recent years yet no signs of increased mortality rates over time were observed. In the largest study to date assessing in-hospital and long-term survival after ECMO for PCS [6], overall successful weaning from ECMO was possible for 63% of patients but survival to hospital discharge was only 25%. These findings were comparable to results of smaller series of patients with PCS undergoing ECMO for which early survival rates of between 16% and 41% have been reported [34,35]. In line with previous reports, in the current analysis, overall successful ECMO weaning was possible in 4,051 cases (56%), yet survival to hospital discharge was achieved in 41% of cases. The trend suggesting overall unchanging mortality over time might be surprising in the face of improvements in intensive care unit management, more advanced ECMO circuit components and novel technologies, as well as increased experience [36]. Rather than searching for alternatives to mechanical circulatory support, which seems the best solution in circulatory collapse, as in PCS, further improvements in patient and ECMO management must be sought. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that LV unloading, as compared to ECMO alone, was associated with 12% lower mortality risk and 35% higher probability of weaning from ECMO [37], albeit found less effective in PCS- than non-PCS setting [37]. In addition, timing of LV unloading [38], peripheral and dynamic cannulation [39,40] and patient tailored anticoagulation protocol [41,42] may all contribute to lower observed hospital mortality.

On the other hand, these improvements may not directly translate to mortality reduction if they are being offset by the application of V-A ECMO for PCS in increasingly older and sicker patients. This possibility is supported by our finding that nearly two-thirds of patients included in the ELSO registry could be successfully weaned from ECMO despite increases in risk scores, patient age, and the complexity of the cardiac procedures. Additionally, performed multilevel regression adjustment for pre-ECMO variables confirmed the stability of the death rates.

Change in survival prediction

Prediction of post-cardiotomy ECMO weaning and survival has been addressed by numerous investigators [1,2,29,33–35]. Pre-implantation, intra-operative, and post-ECMO factors and events all play a critical role. Among pre-ECMO factors, ECMO institution during a cardiac arrest, was a strong negative predictor [43–48]. The current analysis demonstrated that age, pH, and ventilation parameters, were all significantly associated with poor prognosis among pre-ECMO variables. Additionally, when on-ECMO variables and complications were included, so were the occurrence of DIC, GI bleeding, hemolysis and surgical complications. Notably, pre-ECMO variables alone perform worse in predicting hospital death than pre-ECMO, on-ECMO variables and complications in collective.

The impact of patient age on survival requires a distinct discussion in the context of post-cardiotomy ECMO, as many patients eligible for such support are elderly. Indeed, two recent analysis of the ELSO registry [10,49] limited to elderly patients (≥70 y.o.); with over 2,600 elderly, it showed that increasing age itself was not linked to increased mortality in this group. In fact, V-A ECMO may still be helpful and meaningful for some elderly patients, without severe comorbidities and potential for a short recovery time. Therefore, elderly subjects should still be considered for mechanical circulatory support provided that careful analysis, including local experience, resources, and, as said, clinical aspects are met.

Despite difference in short‐term outcomes, estimated late survival in a large-scale meta-analysis of 5824 person‐years was similar [50]. In fact, long‐term survival in both PCS‐ECMO and non‐PCS‐ECMO seems to be strongly influenced by the early hospitalized critical phase, after which the survival slightly drops but remains satisfactory [51].

Benefits of peripheral access

Interestingly, the current report confirms the protective effect of peripheral cannulation for ECMO on survival demonstrated previously in a large study with an accompanying meta-analysis [39]. Patients undergoing peripheral ECMO for PCS had over 25% higher odds of survival compared to their centrally cannulated counterparts which was maintained after matching for pre-ECMO variables: OR: 0.48 (0.40–0.58); P<0.001.With a nearly five-fold higher number of patients in the current single report and focusing exclusively on PCS, the finding of significantly lower mortality rates with peripheral cannulation appears to be a robust finding and certainly deserves attention.

Limitations

We analyzed data from the ELSO Registry, an international collaboration with more than 430 contributing centers. The current analysis is, however, limited by the inherent shortcomings of registry data. All gathered information is of retrospective nature; selection criteria, V-A ECMO protocols, time to support, LV unloading techniques and time, patient management and centers’ ECMO experience and volume, could not be accounted for in the analysis. The registry collects in-hospital data only, therefore long-term follow-up data were not available. Admittedly, some diagnoses, and in particular neurological and cardiovascular outcomes are autopsy findings, and thus be underreported. The registry does not collect data on surgical and procedural characteristics other than the type of surgery. All cardiac surgery operative details are also not available and could all impact the postoperative course. Other information, like the size of the cannulas (available only in 38% of total patient cohort), access site changes during the ECMO run, or lactates levels, were not fully available in the registry.

Findings on mortality benefit with peripheral cannulation must be viewed with caution since the timing of V-A ECMO start (operating room or intensive care unit) was not available in the registry.

Finally, the current ELSO definitions for cardiogenic shock and some adjunctive treatments (eg. Impella® and levosimendan) or arterial line monitoring, were only implemented recently or not present, and therefore not available for the complete data analysis.

Conclusions

The current analysis represents the largest to date single database for heart surgery patients requiring postoperative V-A ECMO and demonstrates significantly increased use of V-A ECMO in patients with postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock from 2010 through 2018. Mortality rates remained relatively constant over time despite a decrease in complications, in the setting of supporting older, and higher risk patients. Further studies are needed to elucidate factors that might optimize patient selection and improve the outcomes of this very complex cohort of ECMO in cardiac surgery patients.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Analysis of hospital death mortality stratified by the type of primary surgery. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; HTx, heart transplantation; VAD, ventricle assist device.

Acknowledgements:

Prof Kiran Shekar acknowledges research support from Metro North Hospital and Health Service.

COI:

Dr. Lorusso is consultant and conducts clinical trial for LivaNova (London, UK), is consultant for Medtronic (Minneapolis, MN), and an Advisory Board member of PulseCath (Arnhem, The Netherlands and Eurosets (Medolla, Italy). Dr. Brodie receives research support from ALung Technologies, he was previously on their medical advisory board. He has been on the medical advisory boards for Baxter, BREETHE, Xenios and Hemovent. Dr. Alexander’s institution receives consulting funds from Novartis and investigational therapeutic agent (levosimendan) from Tenax Therapuetics. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Abrams D, Combes A, Brodie D. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiopulmonary disease in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2769–2778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorusso R, Raffa GM, Alenizy K et al. Structured review of post-cardiotomy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Part 1-adult patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38:1125–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vallabhajosyula S, Arora S, Sakhuja A et al. Trends, predictors, and outcomes of temporary mechanical circulatory support for postcardiac surgery cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:489–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stretch R, Sauer CM, Yuh DD, et al. National trends in the utilization of short-term mechanical circulatory support: incidence, outcomes, and cost analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge M, Pan T, Wang JX, et al. Outcomes of early versus delayed initiation of extracorporeal life support in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitman GJ. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the treatment of postcardiotomy shock. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiagarajan RR, Barbaro RP, Rycus PT et al. Extracorporeal life support organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO J 2017;63:60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nasr VG, Raman L, Barbaro RP et al. Highlights from the extracorporeal life support organization registry: 2006–2017. ASAIO J 2019;65:537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorusso R, Vizzardi E, Johnson DM et al. Cardiac surgery in adult patients with remitted or active malignancies: A review of preoperative screening, surgical management and short- and long-term postoperative results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54:10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorusso R, Gelsomino S, Parise O et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock in elderly patients: Trends in application and outcome from the extracorporeal life support organization (elso) registry. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowalewski M, Raffa GM, Zielinski K et al. The impact of centre’s heart transplant status and volume on in-hospital outcomes following extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory post-cardiotomy cardiogenic shock: A meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nattino G, Pennell ML, Lemeshow S. Assessing the goodness of fit of logistic regression models in large samples: A modification of the hosmer-lemeshow test. Biometrics. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy FH, McDermott KM, Kini V et al. Trends in u.S. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use and outcomes: 2002–2012. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;27:81–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S et al. 2017 esc guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with st-segment elevation: The task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with st-segment elevation of the european society of cardiology (esc). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez AF, Grab JD, Gammie JS et al. A decade of short-term outcomes in post cardiac surgery ventricular assist device implantation: Data from the society of thoracic surgeons’ national cardiac database. Circulation. 2007;116:606–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayanga JWA, Aboagye J, Bush E et al. Contemporary Analysis of Charges and Mortality in the use of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Cautionary Tale. JTCVS Open [Internet]. 2020;Available from: 10.1016/j.xjon.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rastan AJ, Dege A, Mohr M et al. Early and late outcomes of 517 consecutive adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:302–311, 311 e301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranney DN, Benrashid E, Meza JM et al. Central cannulation as a viable alternative to peripheral cannulation in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalewski M, Raffa G, Zielinski K et al. Baseline surgical status and short-term mortality after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for post-cardiotomy shock: A meta-analysis. Perfusion. 2019:267659119865122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meani P, Matteucci M, Jiritano F et al. Long-term survival and major outcomes in post-cardiotomy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult patients in cardiogenic shock. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8:116–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo Coco V, Lorusso R, Raffa GM et al. Clinical complications during veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxigenation in post-cardiotomy and non post-cardiotomy shock: Still the achille’s heel. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:6993–7004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raffa GM, Kowalewski M, Meani P et al. -hospital outcomes after emergency or prophylactic veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation during transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A comprehensive review of the literature. Perfusion. 2019;34:354–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raffa GM, Kowalewski M, Brodie D et al. Meta-analysis of peripheral or central extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in postcardiotomy and non-postcardiotomy shock. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:311–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raffa GM, Gelsomino S, Sluijpers N et al. In-hospital outcome of post-cardiotomy extracorporeal life support in adult patients: The 2007–2017 maastricht experience. Crit Care Resusc. 2017;19:53–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawler PR, Silver DA, Scirica BM et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults with cardiogenic shock. Circulation. 2015;131:676–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu MY, Lin PJ, Lee MY et al. Using extracorporeal life support to resuscitate adult postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock: Treatment strategies and predictors of short-term and midterm survival. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1111–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith M, Vukomanovic A, Brodie D et al. Duration of veno-arterial extracorporeal life support (VA ECMO) and outcome: an analysis of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry. Crit Care. 2017;21:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson AS, Schmidt M, Bailey M et al. Ecmo cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (ecpr), trends in survival from an international multicentre cohort study over 12-years. Resuscitation. 2017;112:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mashiko Y, Abe T, Tokuda Y et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock in adult patients: Predictors of in-hospital mortality and failure to be weaned from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Artif Organs. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khorsandi M, Dougherty S, Bouamra O et al. Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock after adult cardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;12:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flecher E, Anselmi A, Corbineau H et al. Current aspects of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a tertiary referral centre: Determinants of survival at follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:665–671; discussion 671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith C, Bellomo R, Raman JS et al. An extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-based approach to cardiogenic shock in an older population. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1421–1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiser SM, Tribble CG, Kaza AK et al. When to discontinue extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postcardiotomy support. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:210–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbaro RP, Odetola FO, Kidwell KM et al. Association of hospital-level volume of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cases and mortality. Analysis of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:894–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kowalewski M, Malvindi PG, Zielinski K et al. Left ventricle unloading with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock. Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Fares AA, Randhawa VK, Englesakis M et al. Optimal strategy and timing of left ventricular venting during veno-arterial extracorporeal life support for adults in cardiogenic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12:e006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mariscalco G, Salsano A, Fiore A et al. Peripheral versus central extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postcardiotomy shock: Multicenter registry, systematic review, and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo Coco V, Swol J, De Piero ME et al. Dynamic Extracorporeal Life Support: A Novel Management Modality in Temporary Cardio-Circulatory Assistance. Artif Organs. 2020. November 15. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fina D, Matteucci M, Jiritano F et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation without therapeutic anticoagulation in adults: A systematic review of the current literature. Int J Artif Organs. 2020:391398820904372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piacente C, Martucci G, Miceli V et al. A narrative review of antithrombin use during veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: Rationale, current use, effects on anticoagulation, and outcomes. Perfusion. 2020:267659120913803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pontailler M, Demondion P, Lebreton G et al. Experience with Extracorporeal Life Support for Cardiogenic Shock in the Older Population more than 70 Years of Age. ASAIO J 2017;63:279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sertic F, Diagne D, Rame E et al. Short-term outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality with the use of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in elderly patients with refractory cardiogenic shock. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2019;60:636–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendiratta P, Tang X, Collins RT 2nd et al. membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure in the elderly: a review of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. ASAIO J. 2014;60:385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biancari F, Saeed D, Fiore A et al. Postcardiotomy venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients aged 70 years or older. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:1257–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saxena P, Neal J, Joyce LD et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in postcardiotomy elderly patients: The mayo clinic experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:2053–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SN, Jo MS, Yoo KD. Impact of age on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival of patients with cardiac failure. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1347–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowalewski M, Zieliński K, Maria Raffa G et al. Mortality Predictors in Elderly Patients With Cardiogenic Shock on Venoarterial Extracorporeal Life Support. Analysis From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Crit Care Med. 2020. October 14 (ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kowalewski M, Zieliński K, Gozdek M et al. Cardiogenic shock and veno‐arterial extracorporeal life support in heart transplantation/ventricle assist device centres vs. non‐transplant/ventricle assist device units: meta‐analysis. ESC Heart Failure (ahead of print) doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meani P, Matteucci M, Jiritano F et al. Long-term survival and major outcomes in post-cardiotomy extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult patients in cardiogenic shock. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019. January;8(1):116–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.