Abstract

Background:

Household material hardships could have a negative impact on maternal mental health. Understanding mechanisms by which material hardship trajectories affect maternal depression and anxiety could aid health care professionals and researchers to design better interventions to improve mental health outcomes among mothers.

Methods:

The study identified family-level mechanisms by which material hardship trajectories affect maternal depression and anxiety using Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study data (n=1,645). Latent growth mixture modelling was used to identify latent classes of material hardship trajectories at Years-1, −3, and −5. Parenting stress and couple relationship quality was measured at Year-9. The outcome measures included maternal depression and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) at Year-15 based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview - Short Form.

Results:

Parenting stress mediated the association between low-increasing hardship (b=0.020, 95% confidence interval (CI):0.003, 0.043) and maternal depression. Parenting stress also mediated the association between high-increasing hardship (b=0.043, 95% CI:0.004, 0.092), high decreasing hardship (b=0.034, 95% CI=0.001, 0.072), and low-increasing (b=0.034, 95% CI:0.007, 0.066) and maternal GAD. In all models, current material hardship was directly related to maternal depression (b=0.188, 95% CI:0.134, 0.242) and GAD (b=0.174, 95% CI:0.091, 0.239).

Limitations:

Study results need to be interpreted with caution as the FFCWS oversampled non-marital births as part of the original study design.

Conclusions:

While current material hardship appears to be more related to maternal mental health, prior material hardship experiences contribute to greater parenting stress which places mothers at risk for experiencing depression and GAD later on.

Keywords: Couple relationships quality, Depression, Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, Generalized anxiety disorder, Parenting stress

Introduction

Material hardship is defined as the inadequate consumption of very basic goods and services such as food, housing, clothing, and medical care (Beverly, 2001). While income or income-to-poverty ratio provides a general idea of a family’s ability to purchase items, material hardship provides a comprehensive indication of the extent to which families struggle to meet their basic needs. In 2017 approximately 40% of U.S. non-elderly adults reported experiencing hardships during the past 12 months. This percentage increases to nearly two-thirds among households with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty line. Several studies have reported that current experiences of material hardships were associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety among adults (Ahnquist and Wamala, 2011; Katz et al., 2018; Pulgar et al., 2016; Viseu et al., 2018). The next step is to examine how longitudinal material hardship exposure during child’s early childhood period influences maternal mental health later in life.

The Life Course Health Development framework conceptualizes health development as occurring through transactions between the person and environment over time (Halfon et al., 2014). According to this model cumulative disadvantage could have a significant impact on health over extended time frames as well as acute effects (Blane, 2006). Prior research on persistent or transient poverty occurrences has been linked to individuals experiencing poorer health status than their counterparts with no poverty occurrences (McDonough and Berglund, 2003). In addition, research on different poverty trajectory classes has found individuals categorized as “stable nonpoor” generally reported better health than individuals who were categorized as exiting poverty, entering poverty, and stable poor (McDonough et al., 2005). However, research has primarily focused on income or income-to-poverty ratio trajectories, with limited research on how specific trajectories of material hardship are related to maternal mental health. It can be expected that greater levels of material hardships (compared to lower levels of hardship), increased fluctuations of material hardship (compared to decreased fluctuations of material hardship), and associated material hardship instability (compared to stable material hardships) could also have a greater impact on maternal mental health.

Further, evidence is lacking on the family-level mechanisms through which stable and changing material hardship experiences during child’s early childhood period could impact maternal mental health status in later life. According to the Family Stress Model economic hardship may negatively impact family functioning – such as parenting stress and couple relationship quality - which could lead to increased depression or anxiety (Conger et al., 2002). While all parents experience aversive physiological reaction to the demands of being a parent (i.e. parenting stress) (Deater-Deckard, 1998), those experiencing material hardship are at risk of greater levels of parenting stress (Gershoff et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2015). Further, studies have also shown that parenting stress is associated with maternal depression (Chang and Fine, 2007; Nam et al., 2015) and anxiety (Leigh and Milgrom, 2008; McCloskey and Pei, 2019).

In addition, fluctuations in financial status over time and uncertainty associated with the fluctuations can also strain the relationships between couples with children (Conger et al., 2010). Several studies have shown that poor quality partner relationship is associated with maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms (Leach et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2019). In addition, poor relationship quality has been associated with increasing parental stress (Hakvoort et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2017).

Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to evaluate the mechanisms by which material hardship trajectories influence maternal depression and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). The first aim of the study was to evaluate the mediating effect of parenting stress on the association between material hardship trajectories and maternal mental health controlling for the effects of poor couple relationship quality. We hypothesized that the material hardship trajectories classes would be positively associated with parenting stress (Gershoff et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2015) and parenting stress would be positively associated with maternal depression (Nam et al., 2015) and GAD (Deater-Deckard et al., 1994). The second aim was to evaluate the mediating effect of poor couple relationship quality on the association between material hardship trajectories and maternal mental health controlling for the effects of parenting stress. We hypothesized that the material hardships trajectory categories would be positively associated with poor couple relationship quality (Conger et al., 2010) and poor couple relationship quality would be positively associated with maternal depression (Thomas et al., 2019; Whisman and Bruce, 1999) and GAD (Leach et al., 2013; Leach et al., 2017; Sockol et al., 2014). The third aim was to evaluate the indirect effects from material hardships to maternal depression and GAD through the relationship of couple relationship quality and parenting stress. We hypothesized that the poor relationship quality would be positively associated with parenting stress (Lin et al., 2017) and that there is a significant indirect effect between material hardship trajectory classes and maternal depression and GAD through poor couple relationship quality to parenting stress.

Methods

Study sample

Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS) data was used for the current study. The study follows a cohort of 4,898 children born in 20 large U.S. cities between 1998 and 2000. Study data was collected through interviewer-assisted surveys and in-home assessments starting at child’s birth and followed up when children were approximately one, three, five, nine and fifteen years old. Prior to the baseline interview, the FFCWS research team obtained signed informed consent from each participant. The current secondary study protocol was reviewed and approved by the last authors’ Institutional Review Board HSC-SN-21-0256).

For the purpose of the current study, data were extracted from the mother’s interviews at baseline, Year-1, Year-3, Year-5, Year-9, and primary caregiver interviews at Year-9 and 15. Data were excluded if the biological mothers did not participate in any of the maternal interviews or if mother is not the primary caregiver (biological mother was considered as the primary caregiver if she lives with the child for at least half of the time) at Year-9 and 15 (n=2,402). Further those with missing material hardship data (n=1), depression (n=5), anxiety (n=63), parenting stress (n=6), relationship quality (n=615) and missing covariate data (n=161) were also excluded.

The final analytic sample consist of 1,645 mothers with complete data on study variables. Compared to the analytic sample, the participants excluded due to missing data reported higher rate of depression at both Year-1 and 15, high-increasing hardship trajectories or low-increasing hardship trajectories during Year-1 through 5 and greater material hardships at Year-15. The excluded participants were significantly more likely to be younger, non-Hispanic black, U.S. born, unmarried mothers with high school or lower education, public health insurance and income to poverty ratio <0.99.

Measures

Maternal depression.

At Year-1 and 15, mother’s depression status was measured using questions derived from Composite International Diagnostic Interview - Short Form (CIDI-SF) (Kessler et al., 1998). They were asked about feelings of dysphoria and anhedonia during the past year that lasted for two weeks or more. Those who provided an affirmative response were asked seven follow-up questions including: losing interest, feeling tired, change in weight, trouble sleeping, trouble concentrating, feeling worthless, and thinking about death. Mothers who answered affirmatively to three or more questions were considered depressed (Kessler et al., 1998).

Maternal generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

At Year-1 and 15, maternal GAD status were measured using the CIDI-SF (Kessler et al., 1998). GAD is indicated when an individual feels excessively worried or anxious about more than one thing, more days than not, and has difficulty controlling their worries, including specific symptoms such as being keyed up or on edge, irritability, restlessness, tense or aching muscles that last for six months or more. Those who provided affirmative responses to three or more of the seven physiological symptoms were considered as having GAD.

Material hardship.

The household material hardships were assessed in Year-1, −3, and −5 using eight questionnaire items; 1) received free food or meals, 2) unable to pay the full amount of the rent or mortgage, 3) evicted from your home or apartment for not paying the rent or mortgage, 4) missed/late with the gas or electricity bill, 5) borrow money from friends or family to pay bills, 6) move in with other people because of financial problems, 7) stay at a shelter/abandoned building/automobile or any other place not meant for regular housing, 8) could not afford medical care. Based on prior research (Schuler et al., 2020; Zilanawala and Pilkauskas, 2012) a material hardship index was developed by summing affirmative responses to these eight items for each year (possible range 0–8; higher score indicates greater hardships).

Latent growth mixture modelling approach was used to identify latent classes of material hardship trajectories using the material hardship scores at Year-1, −3 and −5 (Daundasekara et al., 2020). The results indicated that the data were fitted best with a linear growth model with four latent classes (BIC= 25745.88, bootstrapped likelihood ratio test <0.001, entropy=0.885 and > 5% of total count in all classes). The latent classes identified four types of linear trends: 1) high levels of material hardships at Year-1 that increased throughout the years (high-increasing), 2) high levels of material hardships at Year-1 that decreased throughout the years (high-decreasing), 3) low levels of material hardships at Year-1 that increased throughout the years (low-increasing), and 4) low levels of material hardships at Year-1 that were stable during first five years after childbirth (low-stable hardships). The average material hardship scores based on the hardship trajectories are shown in Table 1, and the hardship trajectories based on the sample means and the estimated means are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. To use in the mediation models, the class assignment was dummy coded using low-stable hardship class as the reference category.

Table 1.

Average material hardship scoresa based on the hardship trajectory classes identified by the latent growth mixture model, Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, 1999–2017 (n = 1,645)

| Characteristics | High-increasing (n = 81) | High-decreasing (n = 113) | Low-increasing (n = 264) | Low-stable (n = 1,187) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material hardship total score | ||||

| Material hardships score at Year 1 | 3.04 (1.30) | 3.47 (0.94) | 0.94 (0.86) | 0.45 (0.73) |

| Material hardships score at Year 3 | 3.11 (1.56) | 2.12 (1.43) | 1.41 (1.23) | 0.40 (0.76) |

| Material hardships score at Year 5 | 4.17 (1.01) | 0.97 (0.69) | 2.49 (0.66) | 0.24 (0.42) |

| Material hardship trajectory characteristics | ||||

| Mean intercept | 2.84 (0.49) | 3.13 (0.46) | 0.93 (0.34) | 0.50 (0.31) |

| Mean slope | 0.53 (0.20) | −1.05 (0.25) | 0.71 (0.16) | −0.10 (0.12) |

Reported as mean (standard deviation).

Parenting stress.

At Year-9 parenting stress was measured using four questions derived from the Child Development Supplement of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (Abidin, 1995; Mainieri and Grodsky, 2006). The items included: 1) being a parent is harder than I thought it would be, 2) I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent, 3) I find that taking care of my child(ren) is much more work than pleasure, 4) I often feel tired, worn out, or exhausted from raising a family. The responses were recorded using a four-point Likert scale (1=strongly agree, 4= strongly disagree). For the purpose of the current study the items were reversed scored (higher score indicates greater parenting stress), summed and averaged into a summary index. Similar to prior research (Hatem et al., 2020; Schuler et al., 2020), this construct was treated as a formative composite variable for parenting stress (Bollen and Bauldry, 2011).

Couple relationship quality.

The couple relationship quality at Year-9 measured the mother’s perception about the nature of the relationship between mother and father/current partner. Twelve items were used as indicators of relationship quality (e.g. He is fair and willing to compromise when you have a disagreement; he express affection or love for you; he insults or criticizes you or your ideas) (Berryhill et al., 2016). The responses were recorded using a three-point Likert scale (1=often, 2= sometimes, and 3=never), and negatively stated items were revered scored so that higher scores indicate poorer relationship quality. The average score for the total 12-items was used as the indicator of mother’s current relationship quality. Similar to prior research (Petts and Knoester, 2019; Williams et al., 2019), this construct was also treated as a formative composite variable.

Covariates.

Maternal socio-demographic characteristics and baseline mental health diagnoses identified a priori (Heflin and Iceland, 2009; Katz et al., 2018; Leach et al., 2017; Lucero et al., 2016; O’Connor and Nepomnyaschy, 2020) as potentially influence household material hardships and maternal mental health were included as covariates in the mediation models. This includes self-reported race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black [reference], Hispanic, or other), and nativity (us born vs. foreign born [reference]) from the baseline survey and age, marital status (married/cohabitating vs. single/separated [reference]), level of education (less than high school [reference], high school or some college/greater), number of weeks worked in the past year, poverty status (< 100% [reference], 100–299% and ≥ 300% of federal poverty line), and health insurance (public, private or no insurance [reference]) from Year-1. The model for depression and GAD included Year-1 depression diagnosis and GAD diagnosis respectively as a covariate. In addition, models controlled for the total household material hardship score at Year-15.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis for the total sample and by mental health diagnosis were conducted using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, 2017). The material hardship trajectories and socio-demographic characteristics were compared between mothers with and without a diagnosis for depression and GAD using either independent-sample t test (continuous variables) or proportion test (categorical variables).

Covariate adjusted structure equation mediation models were used to evaluate the potential indirect effects of material hardship trajectories on maternal mental health diagnoses (depression and GAD) via parenting stress and poor relationship quality. Models were conducted using Mplus version 8.3 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017). To account for possible non-normality of the effect distributions due to binary outcome variables and categorical independent variable, weighted least square estimation with bootstrapping was used in the mediation analyses (Holtmann et al., 2016; Kelley, 2005). Standardized estimates with 95% bootstrapped (5,000 resamples) confidence intervals (CI) are presented. Significant indirect effects were identified by 95% bootstrapped CI that does not contain a zero.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The sample characteristics for the total sample and by mental health diagnoses are reported in Table 2. At Year-15, 16% of the participants were depressed and 5% reported GAD. Seventy two percent of the sample had low-stable hardships throughout the five-year period while 16% had low-increasing hardships, 7% had high-decreasing hardships and 5% had high-increasing hardships. At Year-9, participants had a mean parenting stress score of 2.01 (0.67), and the mean poor relationship quality score was 1.17 (0.22).

Table 2.

Mental health, potential family level mechanisms, material hardship classes, and socio-demographic characteristics of the analytic sample from Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, 1999–2017 (n=1,645), number (%) or mean (Standard Deviations).

| Characteristics | Total sample (n=1,645) | Depression diagnosis | Comparison test statisticsa | GAD diagnosis | Comparison test statisticsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressed (n=268) | No depression (n=1,377) | GAD (n=86) | No GAD (n=1,599) | ||||

| Characteristics at baseline (at childbirth) | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 440 (26.8%) | 71 (26.5%) | 369 (26.8%) | 0.10 | 20 (23.3%) | 420 (26.9%) | 0.75 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 714 (43.4%) | 133 (49.6%) | 581 (42.2%) | −2.25* | 46 (53.5%) | 668 (42.9%) | −1.94 |

| Hispanic | 428 (26.0%) | 58 (21.6%) | 370 (26.9%) | 1.78 | 19 (22.1%) | 409 (26.2%) | 0.85 |

| Other | 63 (3.8%) | 6 (2.2%) | 57 (4.1%) | 1.48 | 1 (1.2%) | 62 (4.0%) | 1.32 |

| Nativity | |||||||

| US born | 1,395(84.8%) | 243 (90.7%) | 1152 (83.7%) | −2.93** | 76 (88.4%) | 1,319 (84.6%) | −0.95 |

| Foreign born | 250 (15.2%) | 25 (9.3%) | 225 (16.3%) | 10 (11.6%) | 240 (15.4%) | ||

| Characteristics at Year 1 | |||||||

| Age | 26.98 (6.07) | 25.91 (5.99) | 27.19 (6.07) | 3.15** | 25.33(5.48) | 27.07 (6.09) | 2.60** |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married or cohabitating | 1,127 (68.5%) | 170 (63.4%) | 957 (69.5%) | 1.96 | 48 (55.8%) | 1,079 (69.2%) | 2.60** |

| Single/separated | 518 (31.5%) | 98 (36.6%) | 420 (30.5%) | 38 (44.2%) | 480 (30.8%) | ||

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 394 (24.0%) | 69 (25.8%) | 325 (23.6%) | −0.75 | 32 (37.2%) | 362 (23.2%) | −2.96** |

| High school graduate | 458 (27.8%) | 82 (30.6%) | 376 (27.3%) | −1.10 | 21 (24.4%) | 437 (28.0%) | 0.73 |

| Some college or higher | 793 (48.2%) | 117 (43.7%) | 676 (49.1%) | 1.63 | 33 (38.4%) | 760 (48.8%) | 1.87 |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Number of weeks worked during the past year | 26.27 (21.61) | 25.73 (20.85) | 26.37 (21.76) | 0.44 | 25.40 (21.37) | 26.32 (21.63) | 0.39 |

| Poverty status | |||||||

| <100% of FPL | 595 (36.2%) | 117 (43.7%) | 478 (34.7%) | −2.79** | 41 (47.7%) | 554 (35.5%) | −2.28* |

| 100–299% of FPL | 658 (40.0%) | 100 (37.3%) | 558 (40.5%) | 0.98 | 31 (36.1%) | 627 (40.2%) | 0.77 |

| ≥ 300% of FPL | 392 (23.8%) | 51 (19.0%) | 341 (24.8%) | 2.02* | 14 (16.3%) | 378 (24.3%) | 1.69 |

| Health insurance | |||||||

| No insurance | 143 (8.7%) | 22 (8.2%) | 121 (8.8%) | 0.31 | 10 (11.6%) | 133 (8.5%) | −0.99 |

| Medicaid/public insurance | 862 (52.4%) | 160 (59.7%) | 702 (51.0%) | −2.62** | 58 (67.4%) | 804 (51.6%) | −2.87** |

| Private insurance | 640 (38.9%) | 86 (32.1%) | 554 (40.2%) | 2.50* | 18 (20.9%) | 622 (39.9%) | 3.51*** |

| Mental health diagnosis at Year 1 | |||||||

| Diagnosed with depression | 235 (14.3%) | 82 (30.6%) | 153 (11.1%) | −8.34*** | 29 (33.7%) | 206 (13.2%) | −5.29*** |

| Diagnosed with GAD | 52 (3.2%) | 18 (6.7%) | 34 (2.5%) | −3.64*** | 10 (11.6%) | 42 (2.7%) | −4.61*** |

| Material Hardship Classes (Years 1–5 after childbirth) | |||||||

| High-increase | 81 (4.9%) | 31 (11.6%) | 50 (3.6%) | −5.49*** | 10 (11.6%) | 71 (4.6%) | −2.95** |

| High-decrease | 113 (6.9%) | 30 (11.2%) | 83 (6.0%) | −3.06** | 12 (14.0%) | 101 (6.5%) | −2.67** |

| Low-increase | 264 (16.1%) | 58 (21.6%) | 206 (15.0%) | −2.73** | 18 (20.9%) | 246 (15.8%) | −1.27 |

| Low-stable | 1,187 (72.2%) | 149 (55.6%) | 1,038 (75.4%) | 6.61*** | 46 (53.5%) | 1,141 (73.2%) | 3.97*** |

| Potential Family Level Mechanisms at Year 9 | |||||||

| Parenting stress | 2.01 (0.67) | 2.19 (0.67) | 1.97 (0.66) | −4.96*** | 2.35 (0.66) | 1.99 (0.66) | −4.87*** |

| Poor couple relationship quality | 1.17 (0.22) | 1.21 (0.22) | 1.17 (0.22) | −2.50* | 1.25 (0.25) | 1.17 (0.22) | −3.45*** |

| Mental Health Diagnosis at Year 15 | |||||||

| Diagnosed with depression | 268 (16.3%) | 268 (100.0%) | - | 59 (68.6%) | 209 (13.4%) | −13.49*** | |

| Diagnosed with GAD | 86 (5.2%) | 59 (22.0%) | 27 (2.0%) | −13.49*** | 86 (100.0%) | - | |

| Household characteristics at Year 15 | |||||||

| Total material hardship | 0.85 (1.26) | 1.56 (1.59) | 0.71 (1.14) | −10.34*** | 1.80 (1.70) | 0.80 (1.21) | −7.31*** |

Note:

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05.

FPL=federal poverty line; GAD=generalized anxiety disorder

The comparison tests include two sample t-tests for continuous variables and proportion test for categorical variables

Comparison of socio-demographic and health variables between depression diagnosed mothers vs. mothers without depression showed that there are significant differences in material hardship trajectories, race/ethnicity, nativity, age, poverty status, health insurance, Year-1 mental health diagnoses, parenting stress, couple relationship quality and Year-15 GAD diagnosis and material hardship (Table 2). The mothers with and without GAD diagnosis showed significant differences in material hardship trajectories, marital status, education, poverty status, parenting stress and couple relationship quality (Table 2).

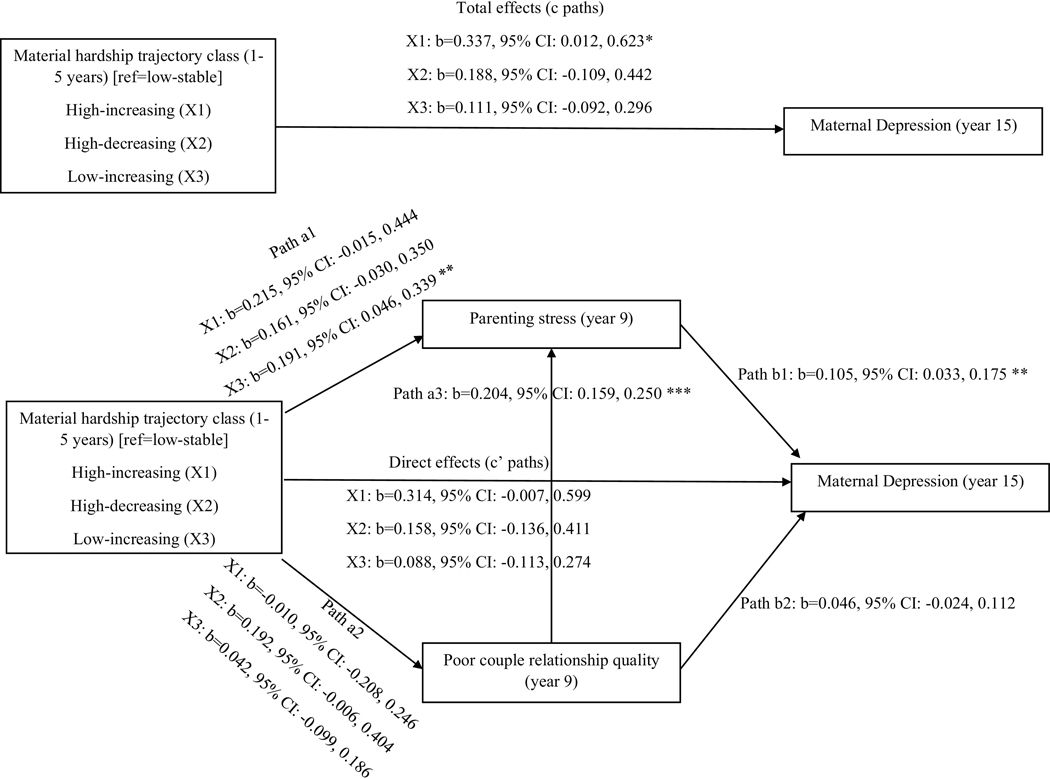

Mediation models predicting depression

The total and direct effects of the four material hardship trajectory classes on maternal depression are listed in Figure 1. The specific indirect effects of parenting stress and poor relationship quality are reported in Table 3. The association between low-increasing hardship class and maternal depression was partially mediated by parenting stress at Year-9 controlling for poor relationship quality (b=0.020, 95% CI: 0.003, 0.043). However, poor relationship quality at Year-9 did not mediated any of the associations between hardship trajectory classes and maternal depression. Similarly, the material hardship classes did not predict maternal depression indirectly through poor relationship quality to parenting stress. However, material hardship at Year-15 was positive associated with the risk of maternal depression at Year-15 (b=0.188, 95% CI=0.134, 0.242).

Fig. 1.

Covariate-adjusted structure equation mediation model of the indirect effects of material hardship trajectory classes (experienced during 1–5 years after childbirth) on maternal depression diagnosis at year 15 thorough parenting stress and relationship quality (standardized estimates), using Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study data, 1999–2017; (n = 1645).

Note: *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05. Path al & a2 = Effect of X on M; path a3 = Effect of M l on M2; b paths = Effect of M on Y; c paths = Total effect of X on Y; c’ paths = Direct effect of X on Y controlling for Ms. Higher scores on parenting stress indicates greater stress and higher scores on relationship quality indicates poorer relationship quality.

All paths are controlled for race/ethnicity, nativity, age, marital status, education, employment, poverty status, health insurance, and depression at one year after childbirth. The paths predicting maternal depression Year-15 included material hardships score at Year-15 as an additional covariate (b = 0.183, 95% CI=0.134, 0.242, p < .001).

Table 3.

Standardized indirect effects from multiple mediator structure equation models with parenting stress and poor couple relationship quality as mediators on the association between household material hardships and maternal depression (n=1,645).

| Mediational path –specific indirect effects (reference=no hardships) | b | SE | 95% Bootstrap CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-increasing material hardship trajectory on depression | |||

| Total indirect effect | 0.023 | 0.018 | −0.008, 0.063 |

| High-increasing → parenting stress → depression | 0.023 | 0.015 | −0.001, 0.059 |

| High-increasing → poor couple relationship quality → depression | 0.000 | 0.007 | −0.013, 0.015 |

| High-increasing → poor couple relationship quality → parenting stress → depression | 0.000 | 0.003 | −0.005, 0.006 |

| High-decreasing material hardship trajectory on depression | |||

| Total indirect effect | 0.030 | 0.015 | 0.004, 0.064 |

| High-decreasing → parenting stress → depression | 0.017 | 0.012 | −0.003, 0.045 |

| High-decreasing → poor couple relationship quality → depression | 0.009 | 0.009 | −0.005, 0.031 |

| High-decreasing → poor couple relationship quality → parenting stress → depression | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.000, 0.011 |

| Low-increasing material hardship trajectory on depression | |||

| Total indirect effect | 0.023 | 0.012 | 0.003, 0.048 |

| Low-increasing → parenting stress → depression | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.003, 0.043 |

| Low-increasing → poor couple relationship quality → depression | 0.002 | 0.004 | −0.005, 0.012 |

| Low-increasing → poor couple relationship quality → parenting stress → depression | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.002, 0.005 |

b=standardized coefficient; CI=confidence interval; SE=standard error

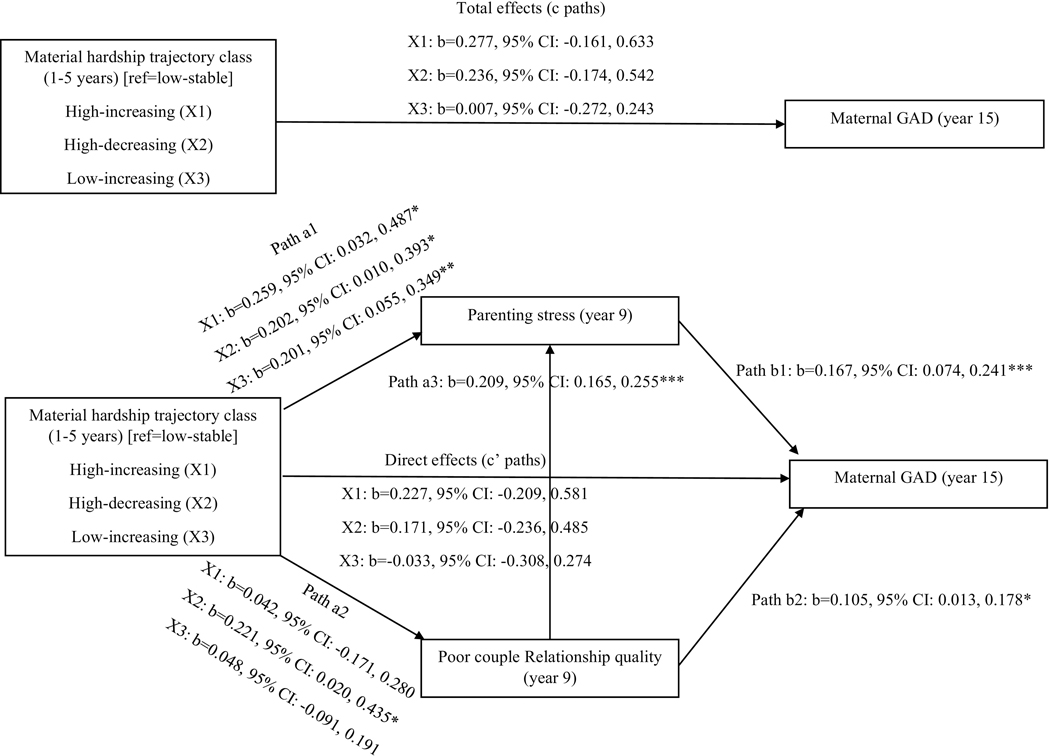

Mediation model predicting GAD

The total and direct effects of the four material hardship trajectory classes on maternal GAD are listed in Figure 2. The specific indirect effects of parenting stress and poor relationship quality are reported in Table 4. The association between maternal GAD and high-increasing hardship (b=0.043, 95% CI: 0.004, 0.092), high-decreasing hardship (b=0.034, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.072) and low-increasing hardship (b=0.034, 95% CI: 0.007, 0.066) is mediated by parenting stress controlling for poor relationship quality. Poor relationship quality was not a significant mediator of the association between the material hardship classes and maternal GAD controlling for parenting stress. However, the high-decreasing hardship predicted maternal GAD diagnosis indirectly through poor relationship quality to parenting stress (b=0.008, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.017). Further, material hardship at Year-15 was positive associated with the risk of maternal GAD at Year-15 (b=0.174, 95% CI=0.091, 0.239).

Fig. 2.

Covariate-adjusted structure equation mediation model of the indirect effects of material hardship trajectory classes (experienced during 1–5 years after childbirth) on maternal general anxiety disorder (GAD) diagnosis at year 15 thorough parenting stress and relationship quality (standardized estimates), using Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study data, 1999–2017 (n = 1645).

Note: *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05. Path a I & a2 = Effect of X on M; path a3 = Effect of M l on M2; b paths = Effect of M on Y; c paths = Total effect of X on Y; c’ paths = Direct effect of X on Y controlling for Ms. Higher scores on parenting stress indicates greater stress and higher scores on relationship quality indicates poorer relationship quality.

All paths are controlled for age, race/ethnicity, nativity, marital status, education, employment, poverty status, health insurance, and GAD diagnosis at one year after childbirth. The paths predicting maternal GAD at Year-’l 5 included material hardships score at Year-15 as an additional covariate (£> = 0.174, 95% CI=0.091, 0.239, p < .001).

Table 4.

Standardized indirect effects of from multiple mediator structure equation models with parenting stress and poor couple relationship quality as mediators on the association between household material hardships and maternal general anxiety disorder diagnosis (GAD) (n=1,645).

| Mediational path –specific indirect effects (reference=low-stable) | b | SE | 95% Bootstrap CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-increasing material hardship trajectory on GAD | |||

| Total indirect effect | 0.049 | 0.028 | −0.002, 0.107 |

| High-increasing → parenting stress →GAD | 0.043 | 0.023 | 0.004, 0.092 |

| High-increasing → poor couple relationship quality →GAD | 0.004 | 0.013 | −0.017, 0.034 |

| High-increasing → poor couple relationship quality → parenting stress → GAD | 0.001 | 0.004 | −0.006, 0.010 |

| High-decreasing material hardship trajectory on GAD | |||

| Total indirect effect | 0.065 | 0.025 | 0.019, 0.116 |

| High-decreasing → parenting stress →GAD | 0.034 | 0.019 | 0.001, 0.072 |

| High-decreasing → poor couple relationship quality →GAD | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.000, 0.057 |

| High-decreasing → poor couple relationship quality → parenting stress → GAD | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.001, 0.017 |

| Low-increasing material hardship trajectory on GAD | |||

| Total indirect effect | 0.040 | 0.018 | 0.007, 0.077 |

| Low-increasing → parenting stress →GAD | 0.034 | 0.015 | 0.007, 0.066 |

| Low-increasing → poor couple relationship quality →GAD | 0.005 | 0.008 | −0.010, 0.023 |

| Low-increasing → poor couple relationship quality→ parenting stress → GAD | 0.002 | 0.003 | −0.003, 0.007 |

b=standardized coefficient; CI=confidence interval; SE=standard error

Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the potential biases due to exclusion of participants with missing data on study variables, the structural equation models were re-analyzed using multiple imputation (n=30 imputations). As Mplus does not generate bootstrapping confidence intervals with imputed data, direct and indirect effect coefficients and p values were compared with the main analysis results.

The maternal depression model with imputed data indicated that the total and direct effect of all three hardship trajectory classes on maternal depression was statistically significant and parenting stress partially mediated the association between each hardship classes and maternal depression. The maternal anxiety model with imputed data showed that the total and direct effect of high-decreasing hardship class and high-decreasing hardship class on anxiety was significant and parenting stress partially mediated the association between each hardship class and maternal GAD. The poor couple relationship quality was not a significant mediator of the association between household material hardship classes and maternal depression/GAD diagnosis. Therefore, the results with imputed data support the main analysis results indicating that material hardships during the child’s early childhood period predicted maternal depression and GAD 10 years later through parenting stress.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate parenting stress and couple relationship quality as mechanisms by which material hardships trajectories during a child’s early childhood period influences maternal depression and GAD diagnoses 10 years later. The study findings showed that compared to low-stable hardships, the high-increasing hardship trajectory class predicted greater likelihood of maternal depression after controlled for Year-15 material hardships. Experiencing greater hardships and significant increases in financial hardships over time could act as an additive stressor that increases the overall stress associated with experiencing any hardships (Lucero et al., 2016). The initial higher levels of hardships can impact a greater adverse effect on maternal depression which is independent of the later financial status of the household. Therefore, it is important to provide continuous support for mothers with young children who have experienced higher amount of material hardships after childbirth or experienced hardships that gradually increases with time. However, this was no longer significant after controlled for parenting stress, poor couple relationship quality.

In contrast to prior evidence (Gershoff et al., 2007; Nam et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2015), hardships trajectory classes during years-1 to 5 was not associated with parenting stress at Year-9 in the maternal depression model except for low-increasing hardship class. However, all hardship classes were significantly associated with greater parenting stress at Year-9 in the GAD model. Similar to prior evidence (McCloskey and Pei, 2019), greater parenting stress was associated with higher likelihood of maternal depression and GAD diagnosis. Partially supporting our first hypothesis, the association between low-increasing hardship class and maternal depression was mediated by parenting stress and the impact of all material hardship trajectory classes on maternal GAD was partially mediated by parenting stress. Financial stress associated with material hardships may enhance the stress associated with parenting, thus placing the mothers with higher hardships or increasing hardships at risk for depression and GAD. Therefore, even though there was no direct impact of material hardships during child’s early childhood on maternal health status in later life, hardships during this period may indirectly impact maternal mental health through increased parenting stress.

According to the depression model, none of the hardship classes predicted poorer couple relationship quality nor did poorer relationship quality predict depression diagnosis. According to the GAD model, compared to mothers with low-stable hardship trajectory, only high-decreasing hardship trajectory class was positively associated with poorer couple relationship quality. The high-decreasing hardship class had the highest mean hardship score at Year-1. It is possible that the amount of hardships experienced immediately following childbirth is more related to relationship quality than the trajectory overtime. Further, studies are needed to understand longitudinal effects of material hardships/trajectory on couple relationship quality. In line with prior research (Leach et al., 2013; Leach et al., 2017), the poorer relationship quality predicted greater maternal GAD diagnosis. However, couple relationship quality did not mediate the association between the material hardship trajectories and maternal mental health diagnoses.

In regards to the final hypothesis, only the association between high-decreasing hardship class and GAD was linked through couple relationship quality to parenting stress. The current study considered couple relationship quality to be a predictor of parenting stress similar to previous studies (Kersh et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2017; Mulsow et al., 2002). However, the two mediating variables were assessed at the same time, and there is evidence to indicate a bidirectional association between couple relationship quality and parenting stress (Berryhill et al., 2016). It is plausible that parents with greater parenting stress have lower couple relationship quality which may influence maternal mental health.

In general, individuals living in poverty are at an increased risk for psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety due to stressors associated with poverty and poverty related hardships (Hudson, 2005; Wadsworth and Achenbach, 2005). However, low income mothers with limited resources also have less access to mental health resources and have limited use of such services (Oh et al., 2018; Santiago et al., 2013; Song et al., 2004). Thus, it is harder to provide treatment for mental health symptoms as well as to reduce predisposing factors. Current results indicate that reducing parenting stress may be an effective strategy to reduce the negative mental health consequences among mothers experiencing higher levels of hardships after child’s birth or hardships that increase during the early childhood period.

Limitations

The current study results need to be interpreted with caution as the FFCWS oversampled non-marital births as part of the original study design (Reichman et al., 2001) and the participants excluded from the current analyses were due to non-participation in the follow up interviews and due to missing data. Those individuals excluded from the analytic sample were more likely to be socio-economically disadvantaged compared to those included in the analytic sample. According to the sensitivity analysis there are few differences in the results when using the imputed data. Future studies need to evaluate the relation between material hardship trajectory and maternal mental health using large population based/ nationally representative samples.

Conclusions

While current material hardship appears to be directly related to maternal mental health, prior material hardship does not directly associate with the risk of experiencing depression and anxiety later on. However, prior material hardship may elevate parenting stress among mothers thus, indirectly increase the risk of maternal depression and GAD. Providing mothers from households with high or increasing material hardships with support to cope with parenting stress may aid in reducing future mental health symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Parenting stress mediates low-increasing hardship trajectory and depression.

Parenting stress mediates various material hardship trajectories and GAD.

Couple relationship quality does not link hardship trajectories and mental health.

Acknowledgments

Funding

FFCWS data used in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HD036916, R01HD039135, and R01HD040421, as well as a consortium of private foundations. The Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01MD015326 to Brittany R. Schuler. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

List of abbreviations

- GAD

Generalized anxiety disorder

- FFCWS

Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study

- CIDI-SF

Composite International Diagnostic Interview - Short Form

- CI

Confidence interval

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

None.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sajeevika S. Daundasekara, Department of Research, Cizik School of Nursing, University of Texas Health Science Center, 6901 Bertner Avenue, 591, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Brittany R. Schuler, School of Social Work, Temple University, 1301 Cecil B. Moore Ave. Ritter Annex 549, Philadelphia, PA 19122.

Jennifer E. S. Beauchamp, Department of Research, Cizik School of Nursing, University of Texas Health Science Center, 6901 Bertner Avenue, 591, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Daphne C. Hernandez, Department of Research, Cizik School of Nursing, University of Texas Health Science Center, 6901 Bertner Avenue, 591, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

References

- Abidin R, 1995. Manual for the parenting stress index, 3rd ed. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Ahnquist J, Wamala SP, 2011. Economic hardships in adulthood and mental health in Sweden. The Swedish National Public Health Survey 2009. BMC Public Health 11, 788. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryhill MB, Soloski KL, Durtschi JA, Adams RR, 2016. Family process: Early child emotionality, parenting stress, and couple relationship quality. Pers Relatsh 23, 23–41. 10.1111/pere.12109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beverly SG, 2001. Measures of material hardship. J Poverty 5, 23–41. 10.1300/J134v05n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blane D, 2006. The life course, the social gradient, and health, In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R. (Eds.), Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 54–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Bauldry S, 2011. Three Cs in measurement models: Causal indicators, composite indicators, and covariates. Psychol Methods 16, 265–284. 10.1037/a0024448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Fine MA, 2007. Modeling parenting stress trajectories among low-income young mothers across the child’s second and third years: Factors accounting for stability and change. J Fam Psychol 21, 584–594. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ, 2010. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J Marriage Fam 72, 685–704. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH, 2002. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Dev Psychol 38, 179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daundasekara SS, Schuler BR, Hernandez DC, 2020. Stability and change in early life economic hardship trajectories and the role of sex in predicting adolescent overweight/obesity. J Youth Adolesc 49, 1645–1662. 10.1007/s10964-020-01249-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, 1998. Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clin Psychol (New York) 5, 314–332. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Scarr S, McCartney K, Eisenberg M, 1994. Paternal separation anxiety: Relationships with parenting stress, child-rearing attitudes, and maternal anxieties. Psychol Sci 5, 341–346. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00283.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, Lennon MC, 2007. Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Dev 78, 70–95. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakvoort EM, Bos HMW, Van Balen F, Hermanns JMA, 2012. Spillover between mothers’ postdivorce relationships: The mediating role of parenting stress. Pers Relatsh 19, 247–254. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01351.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N, Larson K, Lu M, Tullis E, Russ S, 2014. Lifecourse health development: Past, present and future. Matern Child Health J 18, 344–365. 10.1007/s10995-013-1346-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatem C, Lee CY, Zhao X, Reesor-Oyer L, Lopez T, Hernandez DC, 2020. Food insecurity and housing instability during early childhood as predictors of adolescent mental health. J Fam Psychol 34, 721–730. 10.1037/fam0000651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin CM, Iceland J, 2009. Poverty, material hardship, and depression. Soc Sci Q 90, 1051–1071. 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00645.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann J, Koch T, Lochner K, Eid M, 2016. A comparison of ML, WLSMV, and Bayesian methods for multilevel structural equation models in small samples: A simulation study. Multivariate Behav Res 51, 661–680. 10.1080/00273171.2016.1208074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson CG, 2005. Socioeconomic status and mental illness: Tests of the social causation and selection hypotheses. Am J Orthopsychiatry 75, 3–18. 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Crean HF, Cerulli C, Poleshuck EL, 2018. Material hardship and mental health symptoms among a predominantly low income sample of pregnant women seeking prenatal care. Matern Child Health J 22, 1360–1367. 10.1007/s10995-018-2518-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K, 2005. The effects of nonnormal distributions on confidence intervals around the standardized mean difference: Bootstrap and parametric confidence intervals. Educ Psychol Meas 65, 51–69. 10.1177/0013164404264850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kersh J, Hedvat TT, Hauser-Cram P, Warfield ME, 2006. The contribution of marital quality to the well-being of parents of children with developmental disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 50, 883–893. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen H-U, 1998. The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short-form (CIDI-SF). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 7, 171–185. 10.1002/mpr.47 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leach LS, Butterworth P, Olesen SC, Mackinnon A, 2013. Relationship quality and levels of depression and anxiety in a large population-based survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48, 417–425. 10.1007/s00127-012-0559-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach LS, Poyser C, Fairweather-Schmidt K, 2017. Maternal perinatal anxiety: A review of prevalence and correlates. Clin Psychol 21, 4–19. 10.1111/cp.12058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B, Milgrom J, 2008. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry 8, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Zhang Y, Chi P, Ding W, Heath MA, Fang X, Xu S, 2017. The mutual effect of marital quality and parenting stress on child and parent depressive symptoms in families of children with oppositional defiant disorder. Front Psychol 8, 1810–1810. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero JL, Lim S, Santiago AM, 2016. Changes in economic hardship and intimate partner violence: A family stress framework. J Fam Econ Issues 37, 395–406. 10.1007/s10834-016-9488-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mainieri T, Grodsky M. 2006. The panel study of income dynamics-child development supplement: User guide supplement for CDS-I. Institute for Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI: https://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/CDS/CDS1_UGSupp.pdf [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey RJ, Pei F, 2019. The role of parenting stress in mediating the relationship between neighborhood social cohesion and depression and anxiety among mothers of young children in fragile families. J Community Psychol 47, 869–881. 10.1002/jcop.22160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough P, Berglund P, 2003. Histories of poverty and self-rated health trajectories. J Health Soc Behav 44, 198–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough P, Sacker A, Wiggins RD, 2005. Time on my side? Life course trajectories of poverty and health. Soc Sci Med 61, 1795–1808. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulsow M, Caldera YM, Pursley M, Reifman A, Huston AC, 2002. Multilevel factors influencing maternal stress during the first three years. J Marriage Fam 64, 944–956. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00944.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 2017. Mplus user’s guide. Eighth edition. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y, Wikoff N, Sherraden M, 2015. Racial and ethnic differences in parenting stress: Evidence from a statewide sample of new mothers. J Child Fam Stud 24, 278–288. 10.1007/s10826-013-9833-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor J, Nepomnyaschy L, 2020. Intimate partner violence and material hardship among urban mothers. Violence Against Women 26 935–954. 10.1177/1077801219854539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, 2018. Trends in depression among low-income mothers in the United States, 2005–2015. J Affect Disord 235, 72–75. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petts RJ, Knoester C, 2019. Are parental relationships improved if fathers take time off of work after the birth of a child? Soc Forces 98, 1223–1256. 10.1093/sf/soz014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulgar CA, Trejo G, Suerken C, Ip EH, Arcury TA, Quandt SA, 2016. Economic hardship and depression among women in latino farmworker families. J Immigr Minor Health 18, 497–504. 10.1007/s10903-015-0229-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS, 2001. Fragile families: Sample and design. Child Youth Serv Rev 23, 303–326. 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00141-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago CD, Kaltman S, Miranda J, 2013. Poverty and mental health: How do low-income adults and children fare in psychotherapy? J Clin Psychol 69, 115–126. 10.1002/jclp.21951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler BR, Daundasekara SS, Hernandez DC, Dumenci L, Clark M, Fisher JO, Miller AL, 2020. Economic hardship and child intake of foods high in saturated fats and added sugars: the mediating role of parenting stress among high-risk families. Public Health Nutr 23, 2781–2792. 10.1017/s1368980020001366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockol LE, Epperson CN, Barber JP, 2014. The relationship between maternal attitudes and symptoms of depression and anxiety among pregnant and postpartum first-time mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health 17, 199–212. 10.1007/s00737-014-0424-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Sands RG, Wong YLI, 2004. Utilization of mental health services by low-income pregnant and postpartum women on medical assistance. Women Health 39, 1–24. 10.1300/J013v39n01_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15.1. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AL, Caughy MO, Anderson LA, Owen MT, 2019. Longitudinal associations between relationship quality and maternal depression among low-income African American and Hispanic mothers. J Fam Psychol 33, 722–729. 10.1037/fam0000548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viseu J, Leal R, de Jesus SN, Pinto P, Pechorro P, Greenglass E, 2018. Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: Moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res 268, 102–107. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Achenbach TM, 2005. Explaining the link between low socioeconomic status and psychopathology: Testing two mechanisms of the social causation hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol 73, 1146–1153. 10.1037/0022-006x.73.6.1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Bruce ML, 1999. Marital dissatisfaction and incidence of major depressive episode in a community sample. J Abnorm Psychol 108, 674–678. 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DT, Cheadle JE, Goosby BJ, 2015. Hard times and heart break: Linking economic hardship and relationship distress. J Fam Issues 36, 924–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DT, Simon L, Cardwell M, 2019. Black Intimacies Matter: the Role of Family Status, Gender, and Cumulative Risk on Relationship Quality Among Black Parents. J Afr Am Stud 23, 1–17. 10.1007/s12111-019-09420-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zilanawala A, Pilkauskas NV, 2012. Material Hardship and Child Socioemotional Behaviors: Differences by Types of Hardship, Timing, and Duration. Child Youth Serv Rev 34, 814–825. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.