Abstract

Introduction/Aims:

Dysphagia worsens mortality and quality of life for persons diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), yet our understanding of its incidence and timing remains limited. We sought to estimate dysphagia incidence and dysphagia-free survival over time.

Methods:

Using data from the Pooled Resource Open-Access ALS Clinical Trials Database (PRO-ACT), we compared characteristics of persons with and without dysphagia upon study entry. To account for competing mortality risk, we used Kaplan-Meier curves to estimate the cumulative incidence of dysphagia and the median number of days until the development of dysphagia or death in those without dysphagia at study entry.

Results:

Patients with dysphagia upon study entry were more likely to have bulbar onset, had faster rates of functional decline, and shorter diagnostic delays. The cumulative incidence of new onset dysphagia was 44% at 1 year and 64% at 2 years post trial enrollment for those with spinal onset and 85% and 92% for those with bulbar onset. The median duration of dysphagia-free survival post trial enrollment was 11.5 months for those with spinal onset and 3.2 months for those with bulbar onset.

Discussion:

Our findings underscore the high risk for dysphagia development and support the need for early dysphagia referral and evaluation to minimize the risk of serious dysphagia-related complications.

Keywords: dysphagia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, survival, incidence, swallowing

Introduction

Difficulty swallowing, a well-known sequela of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), can result in complications such as aspiration pneumonia and malnutrition1–3 that increase mortality and reduce quality of life. Thus, early identification of dysphagia that leads to timely evaluation and informed patient-centered decision-making regarding management options such as diet modifications and feeding tube placement is a significant contemporary challenge.4 Dysphagia in those with bulbar-onset ALS is more common and occurs earlier than in those with spinal or respiratory onset ALS,5,6 but our knowledge surrounding the incidence and timing of dysphagia onset remains limited due to small samples sizes, lack of control populations, and variation in symptom onset.5–7 The purpose of this study was to quantify the cumulative incidence of dysphagia and the average time of dysphagia-free survival for patients with ALS stratified by site of onset.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study8 of the Pooled Resource Open-Access ALS Clinical Trials (PRO-ACT) database, which includes de-identified clinical patient records from 23 Phase II/III clinical trials and 1 longitudinal study between 1990 and 2015. For this study, inclusion criteria required the ALS Functional Rating Scale Score (ALSFRS) or ALS Functional Rating Scale Score-Revised (ALSFRS-R).9,10 Question 3 on the ALSFRS and ALSFRS-R describe eating on a 5-point ordinal scale from 4 for “Normal” to 0 for “Nothing by mouth (NPO); exclusively parenteral or enteral feeding.” We defined dysphagia as a change in self-reported score from 4 to <4. Diagnostic delay was calculated as months from self-reported symptom onset to diagnosis. We excluded participants with dysphagia at the time of clinical trial enrollment. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Informed consent was waived due to the de-identifiable nature of the data.

To account for deaths, we performed a competing risk survival analysis when estimating the cumulative incidence of dysphagia and dysphagia-free survival as the primary outcome from the time of the baseline study visit.11 Patients alive and free of dysphagia at the end of study follow up were censored at the time of their last ALSFRS or ALFRS-R score. To standardize ALS Functional Rating Scale scores for analyses, all ALSFRS-R scores were converted to ALSFRS scores by removing scores on two questions from the respiratory subscale that differentiate the ALSFRS-R from the ALSFRS. Kaplan-Meier curves estimated the median number of days from enrollment until either the development of dysphagia or death if dysphagia did not occur prior to death. Participants were stratified by site of initial symptom onset for each analysis. Rates of functional disease decline were calculated by dividing the loss of total ALSFRS score points by the months since symptom onset. Analysis for participants with bulbar onset was limited to 2 years, due to paucity of follow-up data beyond 2 years. All analyses were performed using RStudio version 1.1.1335.

Results

Of the 10,723 participants, 4,216 participants were excluded due to missing ALSFRS or ALSFRS-R scores, and 358 were excluded due to absence of the site of symptom onset. Of the remaining 6,149 patients, 2,469 had dysphagia at enrollment and 3,680 patients did not (Table 1). Notably, those with dysphagia upon trial entry were more likely to be female, have bulbar onset, have faster rates of functional disease decline, lower baseline ALSFRS total and bulbar subscale scores, and shorter diagnostic delays.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with and without dysphagia at the time of clinical trial enrollment.

| No Dysphagia (n=3680) | Dysphagia (n=2469) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (sd)) | 55.16 (11.5) | 56.24 (11.7) |

| Female (%) | 1304 (33.0) | 1150 (45.3) |

| Race (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 3377 (94.5) | 2306 (96.3) |

| African American | 38 (1.1) | 23 (1.0) |

| Asian | 72 (2.0) | 15 (.6) |

| Other | 87 (2.4) | 50 (2.1) |

| Bulbar Onset (%) | 258 (7.0) | 1186 (48.0) |

| Months from symptom onset (mean (sd)) | 22.08 (13.5) | 21.16 (14.4) |

| Months from diagnosis (mean (sd)) | 5.24 (3.2) | 10.09 (12.0) |

| Rate of decline (loss of ALSFRS points per month) | 0.54 (0.3) | 0.80 (0.8) |

| Diagnostic Delay (months) | 15.63 (12.3) | 10.99 (8.4) |

| ALSFRS Total Score (mean (sd)) | 31.09 (5.0) | 27.25 (6.4) |

| ALSFRS Bulbar Subscale Score (mean (sd)) | 11.47 (.9) | 7.86 (3.3) |

| ALSFRS Fine Motor Subscale Score (mean (sd)) | 8.23 (2.9) | 8.10 (3.2) |

| ALSFRS Gross Motor Subscale Score (mean (sd)) | 7.62 (2.9) | 7.88 (3.1) |

| ALSFRS Respiratory Subscale Score (mean (sd)) | 3.77 (.5) | 3.4 (.7) |

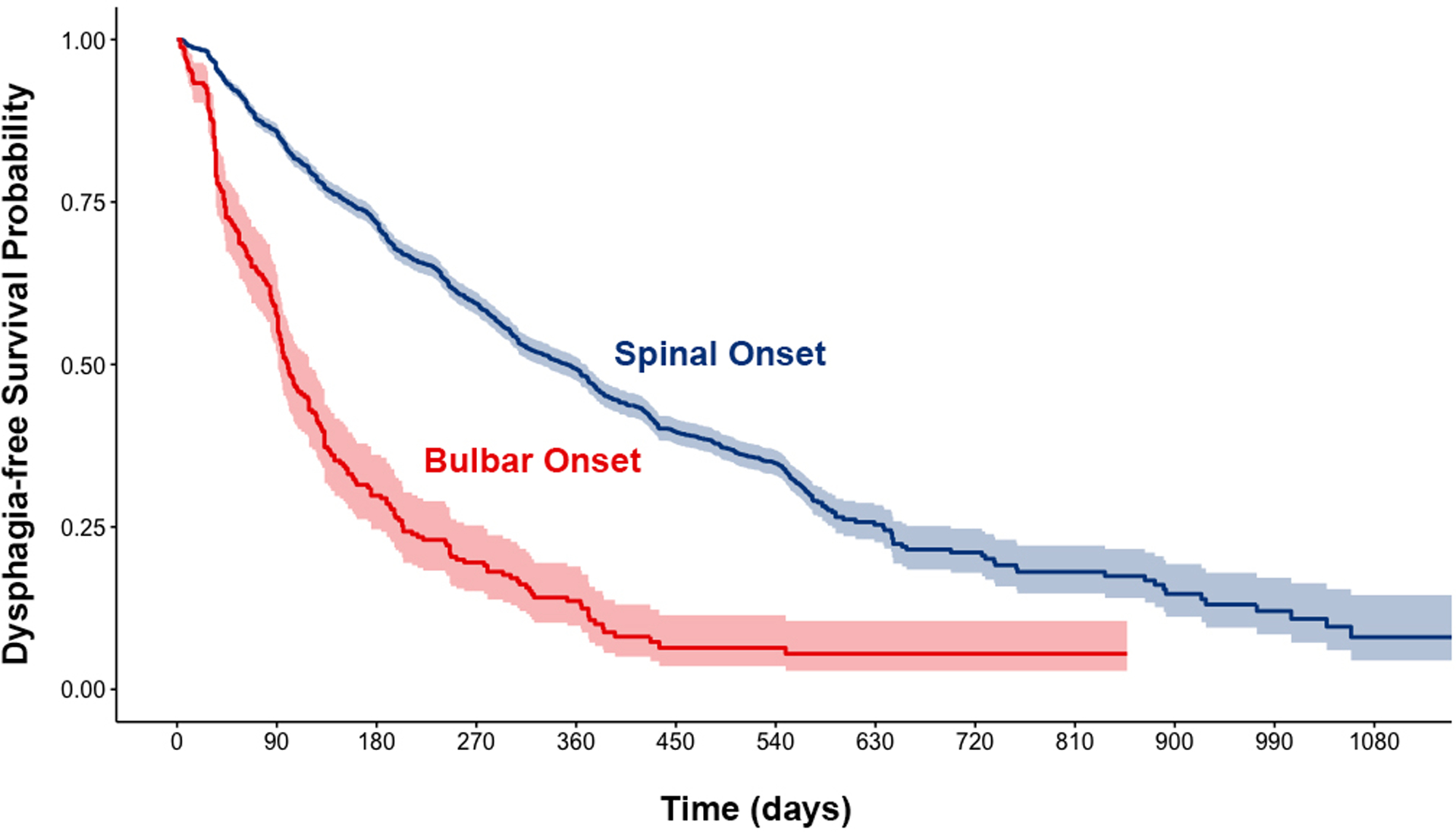

The average time from diagnosis to entrance into a clinical trial was 5.24 months (+/− 3.6), and 5.16 months (+/−3.1) for participants with spinal and bulbar onset respectively. For persons diagnosed with spinal-onset ALS (n=3,422), the cumulative incidence of dysphagia was 44% 1-year after trial enrollment, 64% at 2 years, and 72% at 3 years. Deaths prior to dysphagia onset occurred in 7% of patients with spinal onset at 1 year, 15% at 2 years, and 19% at 3 years post trial enrollment. With bulbar onset (n=258), the cumulative incidence of dysphagia was 85% at 1 year and 92% at 2 years (Figure 1) post trial enrollment. Death free from dysphagia occurred in 1.6% of participants at 1 and 2 years post trial enrollment. The median dysphagia-free survivals were 11.5 (95% CI 0.7–12.1) months post trial enrollment for those with spinal-onset and 3.2 (95% CI 2.9–3.9) months post trial enrollment for those with bulbar-onset.

Figure 1.

Probability of dysphagia-free survival from the time of trial enrollment stratified by site of symptom onset.

Discussion

Our study findings on the incidence of self-reported dysphagia are consistent with previous reports of dysphagia incidence between 82–98% for patients with bulbar onset,6,7 and 34–65% for patients with spinal onset.4,5 These high rates of dysphagia, which often occur relatively early in the disease process, underscore the imminent risk for developing serious dysphagia-related complications, including aspiration pneumonia and malnutrition that increase the risk of death2,3 and reduce quality of life.12

At present, we lack a set of best practices for dysphagia assessment and management for patients with ALS.13 Practice patterns surrounding dysphagia assessment vary widely13, in part, because disease specific risk factors for dysphagia development are not well understood. Our study found bulbar onset, faster rates of disease progression, lower baseline total and bulbar subscale ALSFRS scores, and shorter diagnostic delays to be associated with dysphagia development early in the course of the disease process (prior to clinical trial entry). These risk factors are consistent with characteristics associated with “rapid disease progressors”.14 As nutritional management decisions remain keys to minimizing complications arising from dysphagia and maximizing quality of life for patients diagnosed with dysphagia,6 future work exploring risk factors for dysphagia development in patients with slow disease progression is needed.

Taken together, our findings in this large cohort inform the likelihood and the timing of dysphagia onset. Timely referral for dysphagia evaluation provides greater opportunity for deliberations regarding nutritional management options and for patient-centered input about values and preferences.

Limitations

An important limitation of this study is the reliance on a single self-reported question to define the onset of dysphagia. Prior research suggests that impairments in swallowing may be present prior to patient self-reports.6 Additionally, some patients diagnosed with ALS develop cognitive impairment that may impact their ability to self-report.16 To confirm our findings, future work using objective assessment of dysphagia is warranted.

Secondly, the PRO-ACT database comprises data from participants in clinical trials which often exclude patients with either slow or rapid disease progression, so the generalizability of our findings remains unknown. Additionally, those with dysphagia at trial entry were excluded from our dysphagia-free survival estimates, so our findings on dysphagia-free survival may be more readily generalizable to patients with spinal onset and slow disease progression. Finally, we estimated incidence only among those surviving without dysphagia to the time of clinical trial entry. Because dysphagia-free survival was calculated from the time of the first visit in a clinical trial and not from time since diagnosis to avoid immortal-time bias, our estimates underestimate dysphagia-free survival.17

Conclusions

Dysphagia occurs in at least 70% of patients with ALS, regardless of the site of symptom onset and can occur relatively early in the disease process for many. Future work is needed to explore the impact of dysphagia development on important patient outcomes such as respiratory decline, development of pneumonia, malnutrition and mortality. To reduce dysphagia-related complications such as aspiration pneumonia and malnutrition, future research should seek to incorporate objective measures of dysphagia to confirm risk factors for patients at high risk for the imminent development of dysphagia.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by two National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: [UL1TR002544] and [1TR002546].

Abbreviations

- ALSFRS

ALS Functional Rating Scale Score

- ALSFRS-R

ALS Functional Rating Scale Score – Revised

- ALS

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- NPO

Nothing by Mouth

- PRO-ACT

Pooled Resource Open-Access Clinical Trials Database

Footnotes

Ethical Publication Statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Bridget J. Perry, Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, Tufts Medical Center, 35 Kneeland Street, Boston, Ma 02111, MGH Institute of Health Professions, 79/96 13th Street, Charlestown, Ma 02129.

Jason Nelson, Predictive Analytics and Comparative Effectiveness (PACE) Center, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, Tufts Medical Center, 35 Kneeland Street, Boston, Ma 02111.

John B. Wong, Division of Clinical Decision Making, Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington Street #302, Boston, MA 02111.

David M. Kent, Predictive Analytics and Comparative Effectiveness (PACE) Center, Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, Tufts Medical Center, 35 Kneeland Street, Boston, Ma 02111.

References

- 1.Burkhardt C, Neuwirth C, Sommacal A, Andersen PM, Weber M. Is survival improved by the use of NIV and PEG in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)? A post-mortem study of 80 ALS patients. Zhou R, ed. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiò A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: A critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(5–6):310–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang R, Huang R, Chen D, et al. Causes and places of death of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in south-west China. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12(3):206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waito AA, Valenzano TJ, Peladeau-Pigeon M, Steele CM. Trends in Research Literature Describing Dysphagia in Motor Neuron Diseases (MND): A Scoping Review. Dysphagia. 2017;32(6):734–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruoppolo G, Schettino I, Frasca V, et al. Dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Prevalence and clinical findings. Acta Neurol Scand. 2013;128(6):397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onesti E, Schettino I, Gori MC, et al. Dysphagia in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Impact on Patient Behavior, Diet Adaptation, and Riluzole Management. Front Neurol. 2017;8:94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen A, Garrett CG. Otolaryngologic presentations of amyotrophic lateralsclerosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(3):500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atassi N, Berry J, Shui A, et al. The PRO-ACT database: design, initial analyses, and predictive features. Neurology. 2014;83(19):1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N. Performance of the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS) in multicenter clinical trials. J Neurol Sci. 1997;152:s1–s9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III). J Neurol Sci. 1999;169(1–2):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. Published online 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabor L, Gaziano J, Watts S, Robison R, Plowman EK. Defining Swallowing-Related Quality of Life Profiles in Individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Dysphagia. 2016;31(3):376–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plowman EK, Tabor LC, Wymer J, Pattee G. The evaluation of bulbar dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: survey of clinical practice patterns in the United States. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener. 2017;18(5–6):351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackrivo J, Hansen-Flaschen J, Wileyto EP, Schwab RJ, Elman L, Kawut SM. Development of a prognostic model of respiratory insufficiency or death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen A, Gaelyn Garrett C, Garrett CG. Otolaryngologic presentations of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2005;132(3):500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raaphorst J, de Visser M, Linssen WHJP, de Haan RJ, Schmand B. The cognitive profile of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A meta-analysis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11(1–2):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suissa S Immortal time bias in pharmacoepidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. Published online 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]