Abstract

To investigate genetic and environmental influences on cortisol levels, mothers of children with fragile X syndrome (FXS) were studied four times over a 7.5-year period. All participants (n=84) were carriers of the FMR1 “premutation”, a genetic condition associated with impaired HPA axis functioning. Genetic variation was indicated by expansions in the number of CGG (cytosine-guanine-guanine) repeats in the FMR1 gene (67–138 repeats in the present sample). The environmental factor was cumulative exposure to adverse life events during the study period. Cortisol was measured at the beginning of the study via saliva samples and at the end of the study via hair samples; hormone values from these two specimen types were significantly correlated. The interactions between CGG repeat number and adverse life events significantly predicted hair cortisol concentration, including after accounting for the initial salivary cortisol level. For those with fewer CGG repeats, stress exposure was associated with elevated cortisol, the expected response to stress, although women with a higher number of CGGs had a reduced cortisol response to adverse events, which might be related to HPA dysfunction. These results indicate that both exogenous and endogenous factors affect HPA functioning in this population of women.

Keywords: FMR1 Premutation, Hair cortisol, Salivary cortisol, HPA functioning, Adverse Life Events

1. Introduction

The extant literature offers two distinct perspectives on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Many studies have indicated that cortisol secretion should be considered to be relatively stable, a trait-like characteristic of the individual, whereas from the other perspective, its activity is labile and responsive to the environmental context (Hellhammer et al., 2007; Kirschbaum et al., 1990; Nater et al., 2010). Reconciling these interpretations may be further advanced by evaluating how genetic and environmental factors interactively predict HPA axis functioning, which was the primary aim of the present study.

The genetic factor we investigated was the number of cytosine-guanine-guanine (CGG) repeats in the FMR1 gene (located on the X chromosome). The modal number of FMR1 CGG repeats in the human population is 30, and expansions of more than 200 repeats cause the full mutation of fragile X syndrome (FXS), the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability and autism. When the number of repeats exceeds 200, the FMR1 gene is silenced and no longer produces its protein, resulting in FXS (Brown, 2002; Hagerman & Hagerman, 2002). Symptoms of FXS include learning or intellectual disabilities, behavioral problems, and mental and physical health conditions (Usher et al., 2019; Wheeler et al., 2014b). Hence, parenting a child with FXS can be very challenging (Bailey et al., 2008; Baker et al., 2012; Seltzer et al., 2012b).

Mothers of children with FXS are carriers of the “premutation” of the FMR1 gene (defined as 55–200 CGG repeats), a distinct genetic condition (Hagerman & Hagerman, 2013; Roberts et al., 2016). In the U.S., approximately 1 in 150 females carry this premutation (Seltzer et al., 2012a; Tassone et al., 2012), which may expand to the full mutation of FXS in their children (Nolin et al., 1996). In addition to their risk of having a child with a significant neurodevelopmental disorder, women with the premutation are at increased risk for reproductive, motor, and psychiatric conditions compared to those with modal numbers of CGG repeats (Movaghar et al., 2019; Wheeler et al., 2014a). Thus, the current study focused on a genetically defined population: premutation carrier mothers of children with FXS.

1.1. The FMR1 Premutation, HPA Axis Functioning, and Cortisol

Several studies suggest that FMR1 premutation carriers are at risk for HPA axis dysregulation. A subset of carriers are diagnosed with Fragile X-associated Tremor Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS), a neurodegenerative disease characterized by motor degeneration (intention tremor, ataxia), executive dysfunction, depression, and anxiety (Hagerman & Hagerman, 2016; Leehey et al., 2008; Tassone et al., 2012). Additionally, patients with FXTAS have HPA axis pathology, with intranuclear inclusions at all three neuroendocrine levels (i.e., hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal; Greco et al., 2007; Hunsaker et al., 2011; Jalnapurkar et al., 2015; Louis et al., 2006). FXTAS is most often diagnosed in male carriers over age 50, with more symptom severity in individuals who have CGG repeats in the upper premutation range (i.e., > 100 CGG repeats; Leehey et al., 2008; Tassone et al., 2007). Approximately 15% of female carriers over age 50 are diagnosed with FXTAS, and others have subclinical symptoms of this syndrome. Mouse models of the premutation show phenotypic similarity – elevated corticosterone in serum, ubiquitin-positive inclusions in the pituitary and adrenal glands and in the amygdala of 100-week old animals (not evident in 25-week old animals). Wild-type animals do not show inclusions at either age (Brouwer et al., 2008).

Previous studies have also investigated HPA axis dysregulation in human participants, and have linked differences in hormone levels with stress reactivity in female premutation carriers, with evidence of Gene-by-Environment (GxE) interactions (Hartley et al., 2019; Hunter et al., 2012; Seltzer et al., 2012b). For example, Hunter et al. (2012) assessed the corticotrophin releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1) gene, which plays a central role in HPA axis regulation. They observed a GxE interaction, such that carriers with the TT genotype of the CRHR1 gene and who had a child with FXS had an increased risk of social phobia, while those with this genotype who did not have a child with FXS evinced a decreased risk. GxE interactions were also observed by Seltzer et al. (2012b), and this analysis found a non-linear association between exposure to life events and the cortisol awakening response (CAR), dependent on CGG repeat number. Premutation carriers with approximately 90 or fewer CGG repeats had a normal response to stress (i.e., under conditions of high stress, the CAR was elevated, whereas under conditions of low stress, the CAR was less pronounced). However, the opposite pattern was evident in carriers who had ≥ 90 CGG repeats. Together, the human and animal studies suggest that further evaluation of FMR1 premutation carriers may yield new insights about how genetic and environmental factors contribute to individual and population-level heterogeneity in cortisol activity. The present study extended prior research by evaluating the longitudinal effects of chronic stress exposure among premutation carriers, and whether these effects vary by CGG repeat number.

1.2. Accounting for Variability in Cortisol Secretion

Cortisol can be measured in several types of samples (i.e., serum, saliva, urine, hair), with multiple assessment paradigms (resting, diurnal patterns, experimental provocation), and for varying lengths of time (within a day, over a week or months). In general, the correlations between cortisol levels measured in these diverse ways and across specimens has been weak to moderate (Rector et al., 2019), suggesting that each provides a distinct window into HPA activity. Additionally, different specimen sources of cortisol vary in stability over time. Longitudinal studies of hair samples show strong test-retest reliability, reflecting cumulative cortisol release and uptake into hair over weeks to months. In contrast, serum, saliva, or urine are less stable, reflecting acute changes in circulating cortisol, binding proteins in blood, and excretion by the kidney (Almeida et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2012; Stalder et al., 2011; Stalder et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017). Thus, there seems to be an aspect of cortisol that is responsive to the immediate context as well as a more invariant, trait-like dimension (Hellhammer et al., 2007; Kirschbaum et al., 1990).

The effect of stress exposure on cortisol has been studied extensively and has emphasized the importance of both the severity and duration of stressful events. Chronic stress is more strongly associated with elevated cortisol levels when compared to intermittent and discrete stress, with a fall-off the longer the time has passed since the stressful event (see Miller et al., 2007; Stalder et al., 2017; Staufenbiel et al., 2013). The present study aimed to examine the effect of chronic stress exposure by evaluating the summative effect of repeated measures of adverse life events experienced by participants across a 7.5 year period of challenging parenting.

1.3. The Present Study

There are many unanswered questions about the factors that account for variability in cortisol parameters. These questions shaped the present investigation, which took advantage of a unique source of longitudinal data, including genetic and environmental information as well as two specimen sources (saliva and hair). A key aim that motivated the present study was to increase understanding of both endogenous and exogenous factors that affect HPA functioning, which ultimately may inform a personalized approach to enhancing health. The number of FMR1 CGG repeats may be indicative of endogenous influences on HPA functioning, while exposure to adverse life events reflects an exogenous influence.

The present report begins with a description of the association between cortisol measured in saliva and hair samples obtained an average of 7.5 years apart. Subsequently, for our primary research question, we probed CGG repeat variation within the premutation range and determined whether cortisol levels in hair were a function of the interaction between this indicator of genetic variation and stress exposure. Specifically, we hypothesized that participants who have CGG repeats at the lower end of the premutation range (i.e., closer to normal numbers of CGG repeats) would have a more typical response to stress (i.e., higher levels of hair cortisol following higher levels of stress exposure), reflecting more normal functioning of the HPA axis. In contrast, we anticipated that in participants with CGG repeats toward the upper end of the premutation range (i.e., closer to the full mutation of the FMR1 gene), stress exposure would not predict hair cortisol concentration, suggesting more impaired HPA functioning. These predictions were based on prior research that demonstrated greater abnormalities in diverse phenotypes (motor function, executive function, and mental health) in carriers whose CGG repeat number approaches the full mutation (Hocking et al., 2012; Lachiewicz et al., 2010; Leehey et al., 2008; Tassone et al., 2007).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study participants

Study participants were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study that included 138 premutation carrier mothers of adolescent and adult children with FXS (Mailick et al., 2014). Data for the present analyses were collected at four waves of the study spanning an average of 7.5 years (from 2008–09 to 2016–17). The families lived in 38 US states and in one Canadian province. Mothers were included in the larger study if they were the biological mother of an adolescent or adult (aged 12+ years) with FXS, either living in the same household or having at least weekly contact with this child. The child’s full mutation of FXS was verified by review of medical records of genetic testing. In families with multiple children with FXS (35.0%), one ‘target child’ was selected based on the following criteria and order: (a) the child who was ≥12 years, (b) who resided with mother, and (c) who was most severely affected of those who had FXS. Mothers’ premutation status was verified by medical records and molecular assays as described below. The present analysis included a subset of the sample of premutation carrier mothers who provided data on adverse life events between Time 1 and Time 4, and completed the salivary cortisol collection at Time 1 and provided a hair sample at Time 4 (n = 84).

Table 1 presents descriptive summary statistics about the participants. As shown in Table 1, mothers were a mean 51.0 years of age at Time 1 and 58.5 years at Time 4, with a range from age 45–77 at Time 4. Annual household income averaged $80,000. Most of the women were married (83.3% at Time 1; 76.8% at Time 4) and employed (70.2% at Time 1; 64.3% at Time 4). Over half (61.9%) were college graduates. Most were non-Latino Whites (96%). They had an average of 2.6 children, of whom 1.5 had FXS. The CGG repeats of these premutation carrier mothers ranged from 67 to 138, with a mean of 94 repeats.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary statisticsa for study variables (n = 84).

| (Time 1) | (Time 4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 51.0 (7.3) [37.1, 69.1] | 58.5 (7.2) [44.8, 76.5] |

| Household incomeb | 9.0 (3.2) [1, 14] | 9.5 (3.4) [1, 14] |

| Currently married (%) | 83.3% | 78.6% |

| Currently employed (%) | 70.2% | 64.3% |

| Number of children | 2.6 (1.2) [1, 6] | 2.6 (1.3) [1, 7] |

| Number of children w/ disabilities | 1.8 (0.8) [1, 4] | 2.0 (0.9) [1, 6] |

| Number of children w/ FXS | 1.5 (0.7) [1, 4] | 1.6 (0.7) [1, 4] |

| Target child co-residing with mother (%) | 86.9% | 83.3% |

| Education (% College grad) | 61.9% | |

| CGG repeats | 94.0 (16.1) [67, 138] | |

| Cumulative adverse life events | 7.1 (5.9) [0, 27] | |

| Salivary cortisol AUC total |

65.1 (13.4) [14.5, 118.7] |

|

| AUC: morning rise part | 17.7 (3.7) [2.55, 26.7] | |

| AUC: daily decline part | 47.9 (12.3) [11.4, 101.5] | |

| Hair cortisol, natural log transformed | n/a | 1.86 (1.04) [−.39, 5.23] |

Note.

Means, standard deviation (in parenthesis), and the range (in bracket) are presented unless the variable is marked with (%).

Ordinal scale of income: 1 $1 – $9,999; 9 $80,000 –$89,999; 14 $160,000 or greater. FXS = Fragile X Syndrome, AUC = Area Under the Curve.

2.2. Procedures

The Institutional Review Boards at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute approved the data collection protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all mothers prior to data collection. Mothers participated in telephone interviews and completed self-administered questionnaires at each time point and provided biological samples to confirm genetic status and to measure cortisol, as described below.

2.3. Genetic Data

The FMR1 CGG repeat assay was conducted in the Rush University Medical Center Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory under the direction of Elizabeth Berry-Kravis, MD, PhD. Buccal swabs kits were provided to participants who obtained their own samples (one for each cheek and labelled R and L) and returned the buccal samples via courier packages. DNA was isolated from buccal samples using standard methods. FMR1 genotyping to determine CGG repeat length was conducted with the Asuragen AmplideX® Kit (Chen et al., 2010; Grasso et al., 2014).

CGG repeat number was treated as a continuous variable in the present research. Although past research has yielded varying results regarding the association of CGG repeat number and aspects of the premutation phenotype, in general carriers with fewer repeats within the premutation range (approximately 100 and below) have been shown to have more normal executive functioning, health, mental health, and motor phenotypes than those with greater numbers of CGG repeats (Hartley et al., 2019; Hocking et al., 2012; Lachiewicz et al., 2010; Loesch et al., 2015; Mailick et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2009; Seltzer et al., 2012b; Usher et al., 2019).

2.4. Measurement of Cortisol

Saliva samples were collected at Time 1 as part of an 8-day daily diary protocol (the National Study of Daily Experiences) conducted by the Pennsylvania State University Survey Center (Almeida, 2005; Almeida et al., 2009). On Days 2 through 5 of the Diary Study, mothers collected saliva samples four times throughout the day—morning awakening, 30 min after awakening, at midday, and at bedtime. Saliva was collected using Sarstedt salivette collection devices. Salvia samples were sent in courier packages to our research office and stored in an ultracold freezer at −60 °C. For analysis, the salivettes were thawed and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. Cortisol concentrations were quantified with chemiluminescence immunoassay (IBL; Hamburg, Germany), with intra-assay coefficient variations below 5% (Polk et al., 2005). Three measures of the cortisol diurnal rhythm captured the within-person mean level of cortisol activity over the four days. The three measures were the total AUC (Area Under the Curve) throughout the day, the morning rise part of the AUC (reflecting the AUC between the awakening level and 30 min after awakening), and the daily decline part of the AUC (reflecting the AUC between 30 min after awakening and at bedtime). AUC was calculated with respect to ground (Pruessner et al., 2003).

Hair samples were collected at Time 4. Hair provides a noninvasive and cumulative marker of endocrine activity, reflecting the prior 1–3 months of endocrine activity, and is responsive to stressful life events (Stalder and Kirschbaum, 2012). Each participant provided one lock of hair from the posterior vortex region of the head. Hair was cut as close as possible to the scalp and wrapped in special foil packaging that identified the scalp end. At the laboratory, hair proximal to the scalp was cut to a fixed length (3–4 cm) and weighed (30–40 mg) to approximate 1–3 months of most recent growth.

Cortisol levels were quantified at the Endocrine Assay Services unit of the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Kapoor et al., 2014; Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2020). Hair (10 mg) was washed with 2-propanol to remove hormone and other adherent material from the exterior of the hair shaft, dried, and ground into a fine powder using small steel balls in a Retsch mixer mill (Haan, Germany). Powdered hair was weighed, and then stored in the dark in a glass culture tube at room temperature until the extraction step. For hormone extraction, methanol and an internal standard were added, incubated overnight. The tube was then vortexed and spun in a refrigerated centrifuge, after which the supernatant was processed through solid phase followed by liquid phase extraction. The organic phase was evaporated until dry, resuspended in a mobile phase, and then analyzed on a QTRAP 5500 quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Sciex, Framingham, MA). Chromotagraphic separation was performed using a Kinetex C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Spectrum data were processed with Analyst software (Sciex); intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 4.3, and 9.2, respectively. Hormone concentrations are expressed as pg/mg hair.

2.5. Measurement of Adverse Life Events

In our GxE interaction paradigm, the measure of the environment was exposure to adverse life events experienced by carrier mothers. Much past research has found that adverse life events compromise psychological well-being in the general population (e.g., Hammen, 2004; McCue Horwitz et al., 2007), in parents of children with developmental disabilities (Barker et al., 2011; Warfield et al., 1999), and in mothers of children with FXS (Seltzer et al., 2012b).

Although all mothers in this sample experienced challenging parenting responsibilities for their son or daughter with FXS, they varied with respect to their exposure to other adverse life events. The Life Stress Scale of the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin, 1986) was used to gauge the experience of adverse life events by mothers or by someone in their immediate family (spouse or any of their children). Mothers provided information about the life events experienced during the previous 12 months, and completed this inventory four times during the study (Times 1, 2, 3, and 4). The four repeated measures were summed to capture cumulative exposure to adverse life events during the 7.5-year study period. This measure has been frequently used in studies of families of children with developmental disabilities (Warfield et al., 1999). It is an inventory of ten adverse life events including divorce, marital separation, financial problems (going deeply into debt, decreased income), legal problems, problems at work, death of a friend or family member, alcohol or drug problems, and health problems. We added one item for the present study, namely caregiving responsibilities other than for their son or daughter with FXS, for a total of 11 items. Items were scored dichotomously, 0 (event not experienced) and 1 (self or immediate family member experienced this event) and summed. For the ‘health problems’ item, only such problems experienced by the spouse or children of the participant were scored to avoid confounding health of the mother with her level of the dependent variable of cortisol. Higher total scores reflect having greater exposure to adverse life events within the immediate family over the 7.5 year study period. Life events checklists are commonly used as inventories of events that contribute to stress and compromise well-being, and have been shown to be valid and reliable for this purpose (e.g., Miller, 1996; Shaw et al., 2008).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Participants with seemingly extreme values for salivary and/or hair cortisol were examined with regard to their level of influence on statistical estimations. No cases were found to be overly influential in the analyses reported below (Cook’s D < .5), so all were retained in the analysis.

Table 2 presents the correlations among variables included in the multivariate model. To evaluate the prediction that genetics would interact with stress exposure to predict cortisol level, we fit a linear model with hair cortisol as the outcome variable and modeled it as a function of cumulative stress (adverse life events), CGG repeat number, and their interaction, controlling for maternal age and Time 1 salivary cortisol (total AUC). We evaluated the effect size (small, medium, large) of the interaction between adverse life events and CGG repeat number (Cohen, 1992).

Table 2.

Correlations among study variables (p-values in parenthesis).

| 1. hair cortisol at Time 4 | 2. salivary cortisol (AUC total) at Time 1 | 3. maternal age at T1 | 4. CGG repeats | 5. cumulative adverse life events (Time 1 to Time 4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. hair cortisol at Time 4 | 1.000 | ||||

| 2. salivary cortisol (AUC total) at Time 1 | 0.258 (0.018) | 1.000 | |||

| 3. maternal age at Time 1 | 0.170 (0.123) | 0.060 (0.590) | 1.000 | ||

| 4. CGG repeats | −0.013 (0.908) | 0.035 (0.753) | −0.254 (0.020) | 1.000 | |

| 5. cumulative adverse life events (Time 1 to Time 4) | 0.190 (0.083) | 0.085 (0.446) | 0.131 (0.234) | 0.088 (0.428) | 1.000 |

As a follow-up sensitivity analysis, we repeated the analysis restricting the sample to mothers who lived continuously with their son or daughter with FXS during the 7.5 year study period. The purpose of this sensitivity analysis was to probe the effect of exposure to adverse life events during the time when the stress associated with coresident parenting continued uninterrupted across the study period.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Seven participants had taken oral corticosteroid medication at some point during the study period; however, each of these seven women took the medication at only one time point. The results after exclusion of these cases were very similar to whole sample analysis, suggesting that the reported findings are robust even after considering the possibility of a transient effect of corticosteroid-related medication usage. Therefore, all seven of these participants were retained in the analysis.

Next, we examined the possible effects of hormone replacement medications, such as estrogen, which were taken by about one-third of the participants (35.7%) at some point during the decade prior to Time 4, although only 15.5% were taking such medications at Time 4. Those who took hormone replacement medications at any point during the 10 years prior to Time 4 did not differ from those who never took such medications in either salivary cortisol (AUC total, p = .737) or hair cortisol concentration (p = .832). Similarly, those who took hormone replacement at Time 4 did not differ from those who did not take such medications at that time point in either their salivary cortisol (AUC total, p = .394) or hair cortisol levels (p = .154). Therefore, these women were included in the final analysis.

Finally, we explored the association between several “hair hygiene” variables and hair cortisol, but no significant associations were observed related to the frequency of washing hair per week, whether conditioner was used, or if hair was colored or bleached (ps > .133). However, the frequency of hair washing was significantly correlated with age (r = −0.289, p =.008) and age was controlled in the statistical analyses.

3.2. Descriptive Results

For our descriptive research aim, we evaluated the association between cortisol measured in saliva at Time 1 and in hair samples obtained at Time 4, an average of 7.5 years later. There was a significant association between salivary cortisol, as indexed by the total daily AUC and hair cortisol concentration (r = .253, p < .05), controlling for maternal age. When the total AUC was decomposed into the morning rise after awakening and the daily decline phase, it was only the latter that showed a significant association with hair cortisol (r = .305, p < .01).

During the year prior to each of the four points of data collection across the study period, participants experienced an average of just under two adverse life events (see Table 3). The most prevalent challenge was death of a family member, affecting 52.4% of participants during the full study period. The least common event was divorce, experienced by 5.9% of participants. Across the full study period, participants averaged a total of 7.1 events, ranging from 0 to 27 events per participant.

Table 3.

Percent of premutation carrier mothers who reported each adverse life event [% (n)] as experienced by the family (self, spouse, and children) in the year prior to each data collection time point.

| Event occurred in the past year | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Totala |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death of a family member | 21.4% (18) | 14.3% (12) | 26.2% (22) | 21.4% (18) | 52.4% (44) |

| Health problemsb | 21.4% (18) | 20.2% (17) | 27.4% (23) | 23.2% (20) | 50.0% (42) |

| Any additional caregiving responsibilities | 26.2% (22) | 27.4% (23) | 31.0% (26) | 28.6% (24) | 46.4% (39) |

| Death of a close friend | 10.7% (9) | 11.9% (10) | 15.5% (13) | 22.6% (19) | 45.2% (38) |

| Income decreased substantially (20% +) | 15.5% (13) | 23.2% (20) | 14.3% (12) | 16.6% (14) | 45.2% (38) |

| Trouble with supervisors at work | 13.1% (11) | 8.3% (7) | 8.3% (7) | 13.1% (11) | 34.5% (29) |

| Legal problems | 10.7% (9) | 9.5% (8) | 3.6% (3) | 4.8% (4) | 22.6% (19) |

| Went deeply into debt | 8.3% (7) | 8.3% (7) | 7.1% (6) | 5.9% (5) | 20.2% (17) |

| Alcohol or drug problem | 4.8% (4) | 4.8% (4) | 4.8% (4) | 3.6% (3) | 10.7% (9) |

| Separation | 1.2% (1) | 3.6% (3) | 1.2% (1) | 1.2% (1) | 7.1% (6) |

| Divorce | 1.2% (1) | 3.6% (3) | 1.2% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 5.9% (5) |

| Total number of adverse life events: mean (s.d.) [range] | 1.63 (2.0) [0, 8] | 1.74 (1.9) [0, 8] | 1.93 (2.2) [0, 9] | 1.83 (1.9) [0, 7] | 7.1 (5.9) [0, 27] |

Note.

Total number of distinct respondents who reported each event at any data point.

Health problems occurred to spouse or children only.

3.3. Multivariate Results

To address the primary research question, we investigated whether cortisol level in premutation carriers varied as a function of the interaction between stress exposure and genetic variation. We hypothesized that participants who have CGG repeats at the lower end of the premutation range (i.e., closer to normal numbers of CGG repeats) would show a more typical response to stress (i.e., higher levels of hair cortisol following higher levels of stress exposure), reflecting more normal functioning of the HPA axis. In contrast, we expected that in participants with CGG repeats toward the upper end of the premutation range, stress exposure might not predict hair cortisol concentration, suggestive of a dysregulation of HPA responsiveness.

As shown in Table 4, neither the main effect of CGG repeats nor the cumulative exposure to adverse life events significantly predicted hair cortisol concentration, after taking into account maternal age and their initial level of salivary cortisol (Model 3). However, as hypothesized, the interaction between CGG repeats and adverse life events exposure was a significant predictor (p < .05) of hair cortisol (see Model 4). The effect size for this interaction term was between small and medium (η2 = .07, 95% CI [.001, .196]).

Table 4.

Predicting hair cortisol by cumulative adverse life events (T1 to T4), moderated by the CGG repeat length, net of maternal age and T1 salivary cortisol (AUC total).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coef. | s.e. | p-value | coef. | s.e. | p-value | coef. | s.e. | p-value | coef. | s.e. | p-value | |

| T1 maternal age | .021 | .015 | .164 | .023 | .016 | .154 | .020 | .016 | .220 | .019 | .015 | .210 |

| T1 salivary cortisol (AUC total) | .019* | .008 | .022 | .019* | .008 | .024 | .018* | .008 | .030 | .016* | .008 | .046 |

| CGG | -- | -- | -- | .002 | .007 | .726 | .001 | .007 | .855 | .003 | .007 | .680 |

| Adverse life events (ALE) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .024 | .019 | .223 | .024 | .019 | .207 |

| CGG x ALE | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.003* | .001 | .017 |

| Constant | 1.838 | .109 | <.001 | 1.838 | .110 | <.001 | 1.839 | .109 | <.001 | 1.862 | .106 | <.001 |

| R-sq | .089 | .091 | .108 | .172 | ||||||||

Note: All independent variables are mean-centered.

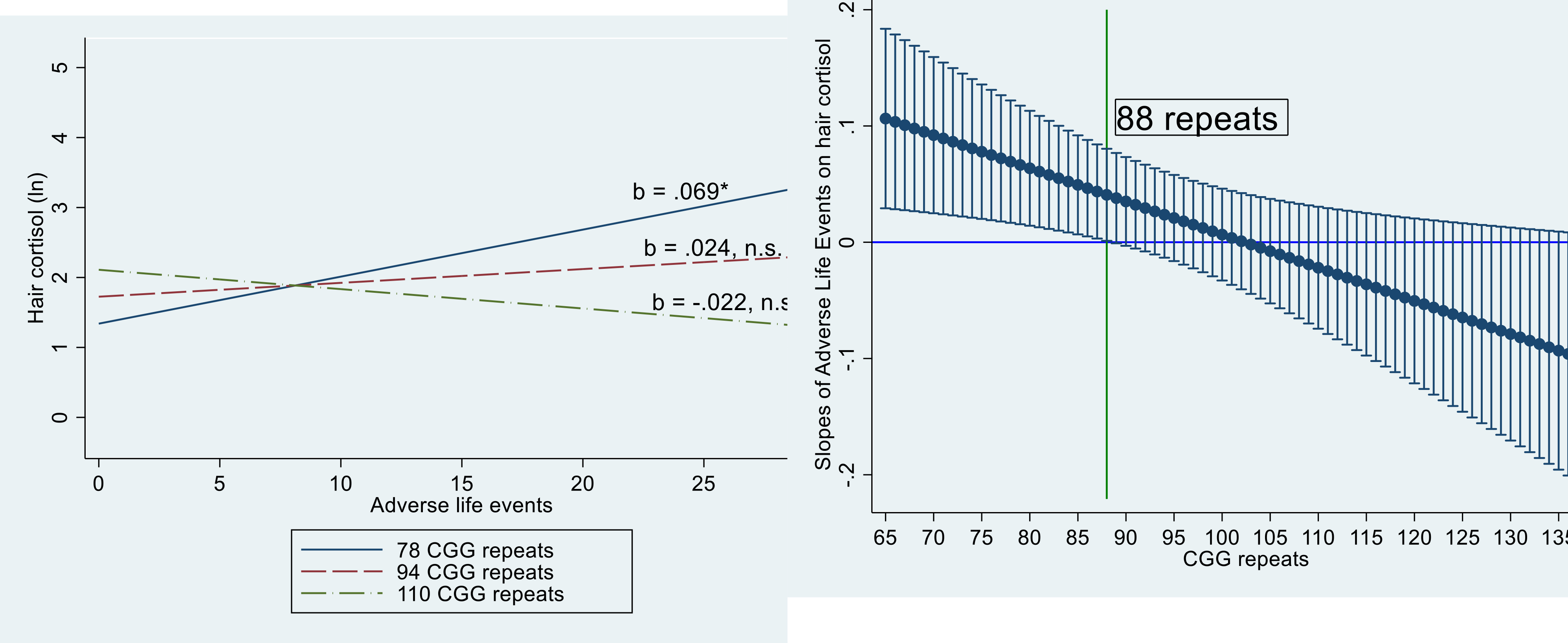

To illustrate the significant interaction between adverse life events and CGG repeats, the results of Model 4 have been plotted in two ways. First, the effect of cumulative adverse life events on hair cortisol was estimated at three CGG points – one standard deviation below the mean (78 repeats), at the mean (94 repeats), and at one standard deviation above the mean (110 repeats). The negative interaction term in the regression model between exposure to adverse life events and CGG repeat length indicates that the slope of the effect of adverse life events decreased as CGG repeat length increased. Figure 1A conveys that the association between hair cortisol concentration and exposure to adverse life events was significant and positive when estimated at 78 CGG repeats, but the association was not significant when estimated at 94 or 110 repeats.

Figure 1.

Interaction effects between cumulative adverse life events and CGG repeat length on hair cortisol.

1A. Linear Fitted Lines of Hair Cortisol by Adverse Life Events by CGG Repeat Groups: 1 standard deviation below the mean (78 repeats), at the mean (94 repeats), and one standard deviation above the mean (110 repeats).

1B. Estimated slope and 95% Confidence Interval of Cumulative Adverse Life Events on Hair Cortisol by CGG Repeat Length.

* p < .05

n.s., not significant

Second, following the approach used by Preacher et al. (2006) to identify the point in the CGG distribution where the association between the adverse life events and hair cortisol became not statistically different from zero, a plot was constructed that illustrated how the slope of the effect of adverse life events on hair cortisol varied by CGG repeat length (Figure 1B). This figure shows that the slope of adverse life events was significantly (p < .05) associated with hair cortisol at the lower end of the CGG repeat range, namely between 65 and 88 CGG repeats. In the present analysis, 36 participants (42.9%) had CGG repeats between 65 and 88. However, among those participants who had more than 88 CGG repeats (n = 48; 57.1%), the effect of adverse life events on hair cortisol was not significantly different from zero.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis: Continuous Coresidence with the Child with FXS

As noted, individuals with FXS have lifelong symptoms, including learning or intellectual disabilities, behavioral problems, and mental and physical health conditions. Hence, parenting a child with FXS can be very challenging. Furthermore, there is evidence that coresiding with a son or daughter with a developmental disability is associated with higher stress exposure and negative impact than when the parent and child live apart (Barker et al., 2011; Namkung et al., 2018; Piazza et al., 2014; Seltzer et al., 2011). Therefore, as a sensitivity analysis, we restricted the analysis to mothers whose son or daughter lived at home continuously during the full study period (n = 67, 79.8%).

As shown in Table S1, the life events that were experienced by this sub-sample were nearly identical in frequency to those experienced by the full sample. As found for the full sample, more than half experienced the death of a family member during the study period, but only 6% were divorced. In total, an average of 7.5 adverse life events were experienced by the members of this sub-sample during the study period.

We next probed the interaction of adverse life events by CGG repeat number in this sub-sample (see Table S2). The results of this analysis showed the same pattern of findings as for the full-sample analysis. Specifically, there was a significant interaction between cumulative adverse life events experienced during the study period and CGG repeat number. For mothers who have fewer CGG repeats, there was a positive association between exposure to adverse life events and hair cortisol level, whereas this association was not significant for the mothers whose CGG repeats were at the mean or above.

4. Discussion

Although parenting a child with FXS has been shown to be stressful (Bailey et al., 2012), the mothers in the present study were also exposed to a variety of other stressful experiences, such as death of friends and family, health concerns among family members, additional caregiving responsibilities, financial difficulties, and difficulties at work. These adverse events are especially relevant in the context of the current Covid-19 pandemic, when similarly stressful life experiences are quite common and ultimately detrimental to the health and well-being of many other people around the world. Our study results indicate the importance of probing genetic variation to reveal the toll taken by these types of adverse life events on the functioning of the HPA axis.

Those participants in the present study who had CGG repeats at the lower (i.e., more normal) end of the premutation repeat range exhibited more typical reactions to cumulative stress; in the context of high exposure to adverse life events, they had elevated levels of cortisol. In contrast, among those who had repeat lengths in the upper premutation range (i.e., closer to the full mutation), the association between exposure to adverse life events and cortisol was not statistically significant, suggestive of HPA axis dysregulation or a reduced sensitivity to environmental influence.

Previous research has provided clues about the HPA axis dysregulation associated with the FMR1 premutation. HPA axis pathology has been documented in both human premutation carriers and mouse models (Brouwer et al., 2008; Greco et al., 2007; Hunsaker et al., 2011; Jalnapurkar et al., 2015; Louis et al., 2006), suggesting an endogenous influence on cortisol synthesis and release into circulation. The evidence in humans derives primarily from studies of premutation carriers who have FXTAS, and these patients tend to have higher numbers of CGG repeats within the premutation range (Leehey et al., 2008; Tassone et al., 2007). In addition, previous research has documented other differences in carriers with repeat numbers in the lower versus the upper parts of the premutation range; in general, those with fewer repeats have more normal executive functioning (Hocking et al., 2012) and mental health (Lachiewicz et al., 2010), as well as fewer symptoms of FXTAS, than those who have high numbers of CGG repeats within the premutation range. Consistent with these studies, the present research found that it was only in those with fewer repeats (88 or fewer CGGs) that the association between adverse life events and hair cortisol was significant. It is possible that the HPA axis pathology in those with higher repeat numbers disrupts normal reactions to cumulative stressors, whereas those with fewer repeats in the premutation range have the more expected pattern of HPA axis functioning.

Although the extant research has provided substantial evidence showing that salivary cortisol is responsive to acute situational contexts, whereas hair cortisol reflects a more prolonged or trait-like aspect of HPA functioning, we found the levels of cortisol in the two specimen sources were significantly associated, in spite of the fact that the measures were obtained 7.5 years apart. By analyzing the association between salivary cortisol parameters and hair cortisol concentration, we were able to probe endogenous influences on the activity of this important endocrine axis.

Notwithstanding the novel findings, it should be acknowledged that the design of the present study had several limitations. Importantly, it would have been advantageous to have hair samples not only at the final time point of the assessment but at the beginning as well, and similarly to have salivary cortisol samples at the last time point, enabling an evaluation of changes in each specimen type over time. It is not possible to draw definitive conclusions about the stability of cortisol levels over time without sampling both specimen types at both time points. Yet the correlation of the two hormone sources over time is informative that there can be an association in the diffusion of cortisol in different tissues, a topic that has been the repeated focus of past research (e.g., Short et al., 2016; Stalder et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the association between the two specimen types does not suggest that they can be used interchangeably or that hair and saliva will always be so strongly correlated.

The generalizability of the findings is also limited by the racial homogeneity of the participants (i.e., non-Hispanic white females). Thus, future research is still needed to gauge the extent to which the patterns are also evident in male premutation carriers and in racially and ethnically diverse populations. Juxtaposed against these limitations are the strengths of the study, which brought together multiple sources of data (genetic associations, varied level of stress exposure, and two different specimen types to assess cortisol activity) to address fundamental questions about HPA functioning.

The conclusions from this evaluation of women with a specific genetic background are significant for a number of reasons. The prevalence of the FMR1 premutation is relatively high – 1 in 150 women in the U.S. have between 55 and 200 CGG repeats in the FMR1 gene and thus are premutation carriers. However, because it is a substantially under-diagnosed condition, much remains to be learned about the biological and psychosocial factors that affect the health and well-being of carriers. It is also an important risk factor for bearing children who will go on to develop a significant neurodevelopmental disorder.

The results of the present study also have broader implications, for both methodological and substantive reasons. Methodologically, although salivary cortisol is generally interpreted to indicate acute reactions to stress, and hair cortisol concentration is typically interpreted to reflect chronic stress exposure, the significant associations we observed between these two bioindicators should motivate future research using different specimen types to examine the extent to which salivary cortisol (collected over multiple days) and hair cortisol measured during the same time are correlated, and under what study conditions one specimen type would be preferable over the other. Further, in this era of personalized medicine, a better understanding of the genetic influences on stress vulnerability has implications for public health. Probing gene by environment interactions can potentially explicate why some individuals are more resilient in the face of stress, while others seem to be more vulnerable.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Stress and genetics interact to predict hair cortisol in FMR1 premutation carriers

The premutation is defined as 55–200 CGG repeats in the FMR1 gene

Women with larger numbers of CGG repeats have more impaired HPA functioning

Women with fewer repeats have the expected elevated cortisol in response to stress

Hair and salivary cortisol are correlated over time in FMR1 premutation carriers

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the women and families who participated in this research, and to Renee Makuch for supervising the data collection for the longitudinal study.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01HD082110, P30 HD003100-S1, U54 HD090256].

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest

Marsha Mailick is the Chair of the Scientific Advisory Board of the John Merck Fund Developmental Disabilities Program. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data analyzed in this study is not publicly available. Due to the sensitive and personal nature of the diagnosis, participants were assured that findings would be released in aggregate form only and original data would not be shared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abidin R, 1986. Parenting Stress Index, second ed. Pediatric Psychology Press, Charlottesville, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, 2005. Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci 14, 64–68. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Charles ST, Mogle J, Drewelies J, Aldwin CM, Spiro A III, Gerstorf D, 2020. Charting adult development through (historically changing) daily stress processes. Am. Psychol 75, 511–524. 10.1037/amp0000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, McGonagle K, King H, 2009. Assessing daily stress processes in social surveys by combining stressor exposure and salivary cortisol. Biodemogr. Soc. Biol 55, 219–237. 10.1080/19485560903382338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB Jr, Sideris J, Roberts J, Hatton D, 2008. Child and genetic variables associated with maternal adaptation to fragile X syndrome: A multidimensional analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 146, 720–729. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DB Jr., Raspa M, Bishop E, Mitra D, Martin S, Wheeler A, Sacco P, 2012. Health and economic consequences of fragile X syndrome for caregivers. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr 33 (9), 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JK, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, 2012. Behavior problems, maternal internalising symptoms and family relations in families of adolescents and adults with fragile X syndrome. J. Intell. Disabil. Res. 56, 984–995. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker ET, Hartley SL, Seltzer MM, Floyd FJ, Greenberg JS, Orsmond GI, 2011. Trajectories of emotional well-being in mothers of adolescents and adults with autism. Dev. Psychol. 47, 551–561. 10.1037/a0021268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer JR, Severijnen EAWFM, De Jong FH, Hessl D, Hagerman RJ, Oostra BA, Willemsen R, 2008. Altered hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal gland axis regulation in the expanded CGG-repeat mouse model for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33, 863–873. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WT, 2002. The molecular biology of the fragile X mutation, in: Hagerman R, Hagerman P, (Eds.), Fragile X syndrome Diagnosis, treatment and research, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp. 110–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Hadd A, Sah S, Filipovic-Sadic S, Krosting J, Sekinger E, Pan R, Hagerman PJ, Stenzel TT, Tassone F, Latham GJ, 2010. An information-rich CGG repeat primed PCR that detects the full range of fragile X expanded alleles and minimizes the need for southern blot analysis. J, Mol, Diagn 12, 589–600. 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, 1992. A power primer. Psychol. Bull 112, 155–159. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso M, Boon EM, Filipovic-Sadic S, van Bunderen PA, Gennaro E, Cao R, Latham GJ, Hadd AG, Coviello DA, 2014. A novel methylation PCR that offers standardized determination of FMR1 methylation and CGG repeat length without southern blot analysis. J, Mol, Diagn 16, 23–31. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, Soontrapornchai K, Wirojanan J, Gould JE, Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ, 2007. Testicular and pituitary inclusion formation in fragile X associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. J. Urol 177, 1434–1437. 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, 2002. Fragile X syndrome Diagnosis, treatment and research, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, 2013. Advances in clinical and molecular understanding of the FMR1 premutation and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 12, 786–798. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70125-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, 2016. Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome—features, mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Neurol 12, 403–412. 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, 2004. Stress and Depression. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol 1, 293–319. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, DaWalt LS, Hong J, Greenberg JS, Mailick MR, 2019. Positive Emotional Support in Premutation Carrier Mothers of Adolescents and Adults With Fragile X Syndrome: Gene by Environment Interactions. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil 124, 411–426. 10.1352/1944-7558-124.5.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellhammer J, Fries E, Schweisthal OW, Schlotz W, Stone AA, Hagemann D, 2007. Several daily measurements are necessary to reliably assess the cortisol rise after awakening: state-and trait components. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, 80–86. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DR, Kogan CS, Cornish KM, 2012. Selective spatial processing deficits in an at-risk subgroup of the fragile X premutation. Brain Cogn. 79, 39–44. 10.1016/j.bandc.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker MR, Greco CM, Spath MA, Smits AP, Navarro CS, Tassone F, Kros JM, Severijnen LA, Berry-Kravis EM, Berman RF, Hagerman PJ, Willemsen R, Hagerman RJ, Hukema RK, 2011. Widespread non-central nervous system organ pathology in fragile X premutation carriers with fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome and CGG knock-in mice. Acta Neuropathol. 122, 467–479. 10.1007/s00401-011-0860-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JE, Leslie M, Novak G, Hamilton D, Shubeck L, Charen K, Abramowitz A, Epstein MP, Lori A, Binder E, Cubells JF, Sherman SL, 2012. Depression and anxiety symptoms among women who carry the FMR1 premutation: impact of raising a child with fragile X syndrome is moderated by CRHR1 polymorphisms. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B 159B, 549–559. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalnapurkar I, Rafika N, Tassone F, Hagerman R, 2015. Immune mediated disorders in women with a fragile X expansion and FXTAS. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 167, 190–197. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor A, Lubach G, Hedman C, Ziegler TE, Coe CL, 2014. Hormones in infant rhesus monkeys’ (Macaca mulatta) hair at birth provide a window into the fetal environment. Pediatr. Res 75, 476–481. 10.1038/pr.2014.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Steyer R, Eid M, Patalla U, Schwenkmezger P, Hellhammer DH, 1990. Cortisol and behavior: 2. Application of a latent state-trait model to salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology 15, 297–307. 10.1016/0306-4530(90)90080-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachiewicz A, Dawson D, Spiridigliozzi G, Cuccaro M, Lachiewicz M, McConkie- Rosell A, 2010. Indicators of anxiety and depression in women with the fragile X premutation: assessment of a clinical sample. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res 54, 597–610. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leehey MA, Berry-Kravis E, Goetz CG, Zhang L, Hall DA, Li L, Rice CD, Lara R, Cogswell J, Reynolds A, Gane L, Jacquemont S, Jacquemont S, Grigsby J, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, 2008. FMR1 CGG repeat length predicts motor dysfunction in premutation carriers. Neurology 70, 1397–1402. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000281692.98200.f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch DZ, Bui MQ, Hammersley E, Schneider A, Storey E, Stimpson P, Burgess T, Francis D, Slater H, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, 2015. Psychological status in female carriers of premutation FMR1 allele showing a complex relationship with the size of CGG expansion. Clin. Genet 87, 173–178. 10.1111/cge.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E, Moskowitz C, Friez M, Amaya M, Vonsattel JPG, 2006. Parkinsonism, dysautonomia, and intranuclear inclusions in a fragile X carrier: a clinical–pathological study. Mov. Disord 21, 420–425. 10.1002/mds.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailick MR, Hong J, Greenberg J, Smith L, Sherman S, 2014. Curvilinear association of CGG repeats and age at menopause in women with FMR1 premutation expansions. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet 165, 705–711. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue Horwitz S, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Storfer-Isser A, Carter AS, 2007. Prevalence, Correlates, and Persistence of Maternal Depression. J. Women’s Heal 16, 678–691. 10.1089/jwh.2006.0185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES, 2007. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol. Bull 133, 25–45. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TW, 1996. Current measures in the assessment of stressful life events, in: Miller TW, (Ed), Theory and assessment of stressful life events. International Universities Press, Madison, CT, pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Movaghar A, Page D, Brilliant M, Baker MW, Greenberg J, Hong J, DaWalt LS, Saha K, Kuusisto F, Stewart R, Berry-Kravis E, Mailick MR, 2019. Data-driven phenotype discovery of FMR1 premutation carriers in a population-based sample. Sci. Adv 5, eaaw7195. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung EH, Greenberg JS, Mailick MR, Floyd FJ, 2018. Lifelong parenting of adults with developmental disabilities: Growth trends over 20 years in midlife and later life. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil 123, 228–240. 10.1352/1944-7558-123.3.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater UM, Hoppmann C and Klumb PL, 2010. Neuroticism and conscientiousness are associated with cortisol diurnal profiles in adults—Role of positive and negative affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 1573–1577. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolin SL, Lewis FA, Ye LL, Houck GE, Glicksman AE, Limprasert P, Li SY, Zhong N, Ashley AE, Feingold E, Sherman SL, Ted Brown W, 1996. Familial transmission of the FMR1 CGG repeat. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 59, 1252–1261. 10.1136/jmg.34.4.349-b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza VE, Floyd FJ, Mailick MR, Greenberg JS, 2014. Coping and psychological health of aging parents of adult children with developmental disabilities. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil 119, 186–198. 10.1352/1944-7558-119.2.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann-Tynan J, Engbretson A, Vigna AB, Weymouth LA, Burnson C, Zahn- Waxler C, Kapoor A, Gerstein ED, Fanning KA, Raison CL, 2020. Cognitively- Based Compassion Training for parents reduces cortisol in infants and young children. Infant Ment. Health. J 41, 126–144. 10.1002/imhj.21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk DE, Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Kirschbaum C, 2005. State and trait affect as predictors of salivary cortisol in healthy adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30, 261–272. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ, 2006. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH, 2003. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology 28, 916–931. 10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rector JL, Tay L, Wiese CW, Friedman EM, 2019. Relative sensitivity of cortisol indices to psychosocial and physical health factors. PloS One 14, p.e0213513. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Bailey DB Jr, Mankowski J, Ford A, Sideris J, Weisenfeld LA, Heath TM, Golden RN, 2009. Mood and anxiety disorders in females with the FMR1 premutation. Am J Med Genet Part B. 150B, 130–139. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Tonnsen BL, McCary LM, Ford AL, Golden RN, Bailey DB Jr, 2016. Trajectory and predictors of depression and anxiety disorders in mothers with the FMR1 premutation. Biol. Psychiatry 79, 850–857. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell E, Koren G, Rieder M, Van Uum S, 2012. Hair cortisol as a biological marker of chronic stress: current status, future directions and unanswered questions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 589–601. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Baker MW, Hong J, Maenner M, Greenberg J, Mandel D, 2012a. Prevalence of CGG expansions of the FMR1 gene in a US population- based sample. Am J Med Genet Part B. 159B, 589–597. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Barker ET, Greenberg JS, Hong J, Coe C, Almeida D, 2012b. Differential sensitivity to life stress in FMR1 premutation carrier mothers of children with fragile X syndrome. Health Psychol. 31, 612–622. 10.1037/a0026528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Floyd F, Song J, Greenberg J, Hong J, 2011. Midlife and aging parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Impacts of lifelong parenting. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil 116, 479–499. 10.1352/1944-7558-116.6.479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw WS, Dimsdale JE, Patterson TL, 2008. Stress and life events measures, in: Rush AJ, First MB, Blacker D, (Eds), Handbook of psychiatric measures, second ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA, pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Short SJ, Stalder T, Marceau K, Entringer S, Moog NK, Shirtcliff EA, Wadhwa PD, Buss C, 2016. Correspondence between hair cortisol concentrations and 30-day integrated daily salivary and weekly urinary cortisol measures. Psychoneuroendocrinology 71, 12–18. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, Evans P, Hucklebridge F, Clow A, 2011. Associations between the cortisol awakening response and heart rate variability. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 36, 454–462. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, Kirschbaum C, 2012. Analysis of cortisol in hair–state of the art and future directions. Brain Behav. Immun. 26, 1019–1029. 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, Steudte S, Miller R, Skoluda N, Dettenborn L, Kirschbaum C, 2012. Intraindividual stability of hair cortisol concentrations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 602–610. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, Steudte-Schmiedgen S, Alexander N, Klucken T, Vater A, Wichmann S, Kirschbaum C, Miller R, 2017. Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 77, 261–274. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staufenbiel SM, Penninx BW, Spijker AT, Elzinga BM, van Rossum EF, 2013. Hair cortisol, stress exposure, and mental health in humans: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 1220–1235. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Adams J, Berry- Kravis EM, Cohen SS, Brusco A, Leehey MA, Li L, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, 2007. CGG repeat length correlates with age of onset of motor signs of the fragile X- associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS). Am J Med Genet Part B. 144B, 566–569. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Greco CM, Hunsaker MR, Seritan AL, Berman RF, Gane LW, Jacquemont S, Basuta K, Jin LW, Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ, 2012. Neuropathological, clinical and molecular pathology in female fragile X premutation carriers with and without FXTAS. Genes Brain Behav. 11, 577–585. 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher LV, DaWalt LS, Greenberg JS, Mailick MR, 2019. Unaffected siblings of adolescents and adults with fragile X syndrome: Effects on maternal well-being. J. Fam. Psychol 33, 487–492. 10.1037/fam0000458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfield ME, Krauss MW, Hauser-Cram P, Upshur CC, Shonkoff JP, 1999. Adaptation during early childhood among mothers of children with disabilities. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr 20, 9–16. 10.1097/00004703-199902000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AC, Bailey DB, Berry-Kravis E, Greenberg J, Losh M, Mailick M, Milà M, Olichney JM, Rodriguez-Revenga L, Sherman S, Smith L, Summers S, Yang JC, Hagerman R, 2014a. Associated features in females with an FMR1 premutation. J. Neurodev. Disord 6, 1–14. 10.1186/1866-1955-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AC, Raspa M, Bann C, Bishop E, Hessl D, Sacco P, Bailey DB Jr, 2014b. Anxiety, attention problems, hyperactivity, and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 164, 141–155. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Chen Z, Chen S, Xu Y, Deng H, 2017. Intraindividual stability of cortisol and cortisone and the ratio of cortisol to cortisone in saliva, urine and hair. Steroids 118, 61–67. 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.