Sleep is a vital process conserved from jellyfish to humans and is necessary for optimal organism function [1]. Moreover, while sleep abnormalities are implicated in a broad range of neurodevelopmental, neuropsychiatric, and neurodegenerative diseases, the mechanisms of sleep regulation remain incompletely understood [2]. Genetics stands well-poised to offer insights into how the body regulates sleep.

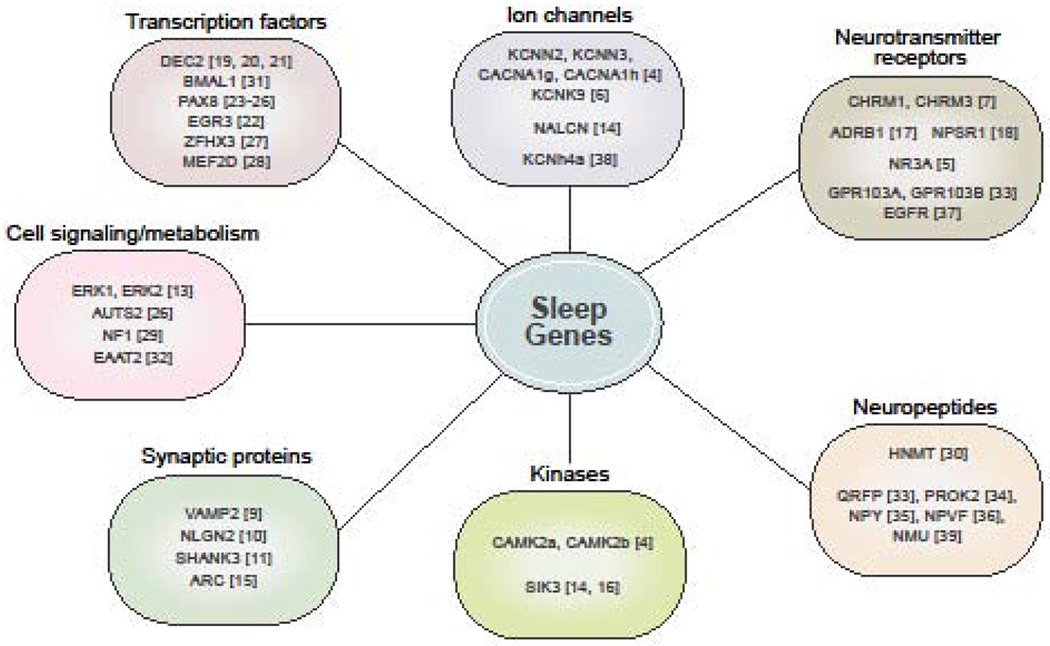

Genetic studies have implicated a quickly-growing array of genes involved in sleep regulation with a staggering array of functions including neuropeptides, ion channels, transcription factors, synaptic proteins, kinases, metabolism, and intracellular signaling cascades (Figure 1). Traditionally, the chokepoint in sleep studies has been the analysis of electroencephalogram (EEG) data, which must be done painstakingly by human scorers. In recent years, the introduction of high-throughput systems such as video tracking and breathing that serve as proxies for sleep have been used as a first pass to help screen for sleep-relevant genes followed by further analysis with EEG, greatly facilitating the pace of new discoveries.

Fig. 1. Recent genes known to affect sleep by functional category.

Genes affecting sleep fall into many broad functional categories, reflecting that a wide array of biological processes may influence sleep. The bracketed numbers reflect reference the gene is mentioned in. The largest categories are brain-specific genes such as ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, neuropeptides, and synaptic proteins. However, an increasing number of transcription factors, kinases, metabolism, and cell-signaling factors have also been implicated.

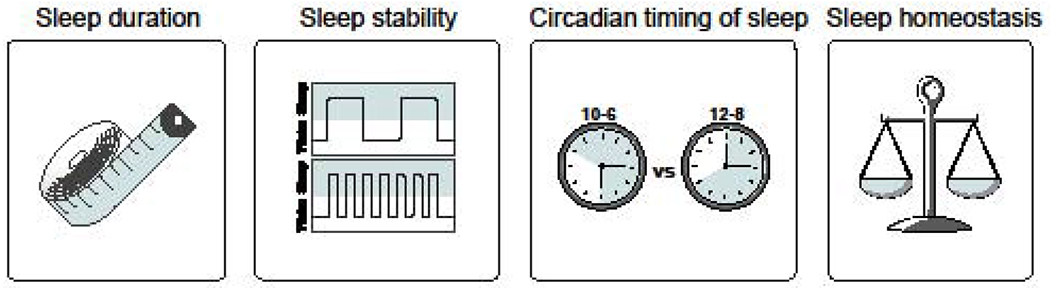

In general, sleep-associated genes can be subdivided into genes that affect sleep duration and those that affect sleep consolidation, timing, and homeostasis (Figure 2). For instance, ablating orexin neurons does not change sleep duration, but does cause more fragmented sleep [3]. This framework is particularly helpful given that the FDA has recently approved several orexin antagonists to treat sleep problems. Besides sleep duration versus sleep consolidation, another useful schematic for categorizing genetic effects on sleep is to note whether the manipulation alters the substages of either rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or non-REM (NREM) sleep, given that it is well-established that REM and NREM sleep are regulated via distinct neural circuitries [2]. To date, it is striking that the vast majority of gene knockouts (KO) and point-mutations known to affect sleep duration have led to a decrease in sleep, possibly due to the difficulty of differentiating between sleep and locomotor defects when locomotion is used as a proxy for sleep in model organisms. Finally, when assessing genetic effects on sleep phenotypes, it is important to pay attention to the magnitude of the change. The vast majority of genetic alterations change sleep by ~1 hour in mice, raising the possibility that more dramatic phenotypes may reflect more fundamental processes.

Fig. 2. Genes can affect specific components of sleep.

Most genes implicated in sleep affect a specific component of sleep, reflecting the fact that these different sleep components are likely regulated by different mechanisms. However, a single gene can sometimes affect multiple components. Sleep duration refers to the average time spent asleep per night. Genes can affect the duration of both REM and NREM sleep. Sleep stability refers to how fragmented or consolidated an organism’s sleep is. Some genes affect the ability of an organism to have consolidated sleep. Circadian timing of sleep refers to when in the circadian day most of an organism’s sleep occurs. Some genes change when in the day the majority of sleep occurs. Finally, some genes affect sleep homeostasis. Genes that affect this component lead to alterations in an organism’s ability to respond to sleep deprivation.

Genes implicated in mouse sleep duration

A wide variety of ion channel KOs have recently been implicated in short sleep in mice, including the calcium-dependent potassium channels KCNN2 and KCNN3, voltage-gated calcium channels CACNAlg and CACNAlh, the leak potassium channel KCNK9, and the NMDA receptor subunit NR3 A [4, 5, 6]. Through triple-target CRISPR single generation KOs, the same lab implicated other calcium dependent processes in short sleep, including the calcium/calmodulin dependent kinases CAMK2a and CAMK2b [4]. Besides ion channels, KO studies have indicated the metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors for acetycholine CHRM1 and CHRM3 in short sleep [7]. Curiously, CHRM1/CHRM3 double KOs had undetectable levels of REM sleep, despite classic studies demonstrating that selective REM sleep deprivation in rats can be fatal [7, 8]. Although these studies of mouse gene KOs are intriguing, abnormalities in ion channels are common in many neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Thus, the sleep duration phenotype may be comorbid with other behavioral abnormalities, limiting the ability of these KO studies to offer insight into therapeutic interventions for humans. A crucial challenge to the sleep field moving forward will be to discover genetic alterations with relative specificity for the sleep system, which provide more appealing therapeutic targets.

Several mouse KO studies have also implicated synaptic proteins in short sleep. Mice with a T441A mutation in VAMP2, which mediates synaptic vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter release, have about ~1.4 hours less NREM sleep and ~1.2 hours less REM sleep [9]. The VAMP2 mutation works in part by decreasing the probability of wake->NREM and NREM->REM transitions. Furthermore, mice lacking either one or both functional copies of NLGN2, a transmembrane scaffolding protein found primarily at GABAergic synapses, sleep less, and the full-body KO has decreases in NREM and REM totaling ~1 hour [10]. In addition, mice lacking exon 21 of the postsynaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 (SHANK3ΔC) sleep −1 hour less in the dark period due to decreases in both REM and NREM sleep and take longer to enter into NREM sleep following sleep deprivation [11]. Although it is tempting to speculate about the role of synaptic proteins contributing to a mechanism of sleep duration, especially in light of the synaptic homeostasis hypothesis (SHY) of sleep which posits one of the main functions of sleep is to change synaptic weighting, it is worth noting that both NLGN KO mice and SHANK3ΔC mice have severe nonsleep behavioral abnormalities [11, 12]. Indeed, the SHANK3ΔC mice are used as a mouse model of autism [11]. Finally, a recent report showed that a whole-body ERK1 KO or a cortical neuron-specific ERK2 KO led to ~30 minutes less sleep [13]. Since ERK signaling is a widespread intracellular cascade, further investigation is needed to shed light on how ERK signaling in the brain regulates sleep specifically.

While the above studies shortened either only NREM sleep or a combination of NREM sleep and REM sleep, several recent discoveries have found specific alterations to REM sleep. KO mice of the sodium leak channel NALCN led to a ~20 minute reduction in REM sleep, while KO mice of the synaptic downscaling associated protein ARC led to more REM sleep [14, 15]. So far, there are few genes that affect solely REM sleep, perhaps due to REM sleep’s relative rarity: a mouse spends only ~5% of its day in REM, making alterations in REM sleep difficult to pick out unless EEG is used as the primary outcome measure.

Among recent mammalian genetic advances, only alterations to the calcium-dependent ATPase ATP2b3 and the kinase SIK3 in mice have been shown to increase total sleep time [4,14]. Genetic KOs of ATP2b3 led to an increase in sleep of ~1 hour [4]. Mice that skip exon 13 of SIK3 have ~4 more hours of NREM sleep [14]. Subsequent work showed that a single point mutation on S551A of SIK3 could lead to ~3 more hours of NREM sleep [16].

Single gene mutations identified in human natural short sleepers

Along these lines, our group has made recent discoveries in familial natural short sleepers (FNSS), who naturally need only 4-6 hours of sleep a night. Crucially, FNSS carriers exhibit no obvious neuropsychiatric or other comorbid conditions, making them an intriguing avenue to study the regulation of sleep. At their best, FNSS carriers can be thought of as individuals resistant to the detrimental effects of long-term sleep deprivation, raising the possibility that FNSS carriers sleep more efficiently. Two recent studies from our lab have shown that both human carriers and CRISPR mouse models with point mutations in the neurotransmitter and neuropeptide receptors ADRB1 and NPSR1 exhibit less sleep [17, 18]. The ADRB1 mutation decreased the protein stability of ADRB1, attenuated the cAMP response, and altered the activity of neurons in vivo, while the NPSR1 mutation made the NPSR1 protein more sensitive to its agonist NPS in vivo [17, 18]. Interestingly, both ADRB1 and NPSR1 mutant mice have higher delta power during NREM sleep—a marker of sleep pressure—at the end of their active period compared to wild type (WT) animals but the delta power quickly falls to WT levels, suggesting the possibility that the FNSS mutation allows individuals to sleep more efficiently in part by more quickly relieving sleep pressure [17, 18].

In the first FNSS family, we found a P384R mutation in the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor DEC2 that led to short sleep in humans and mice [19]. The mutation works by decreasing the repressive activity of DEC2. Using studies of human dizygotic twin, a subsequent study by another group has found a second Y362H mutation in DEC2 associated with short sleep and resistance to sleep deprivation [20]. Crucially, this mutation also decreases the repressive activity of DEC2. More recently, we have demonstrated that the DEC2 mutation works at least in part through modulating orexinergic signaling [21]. In cell culture and in vivo, the DEC2 P384R mutation led to increased expression of orexin-related genes and orexin antagonists were able to blunt the increased mobile time of the DEC2 P384R mutant mice. Unpublished data from our lab also suggests that overexpressing DEC2 P384R solely in orexin-expressing cells can reproduce the whole-body short sleep phenotype. DEC2 is not the only transcription factor that can lead to sleep effects as knocking out the immediate early gene transcription factor EGR3 in mice led to ~30 minutes of less sleep in the dark period, though the study provided no NREM versus REM breakdown [22]. Overall, these results highlight the ability of transcription factors to influence sleep.

Genome-wide association studies with large human populations

In recent years there have also been a growing number of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in humans looking at the effect of SNPs on sleep. The most consistent result has been a SNP near PAX8, a thyroid-specific transcription factor, which has been implicated in four separate GWAS studies and leads to a ~2.7min increase in self-reported sleep duration [23–26]. A UK biobank GWAS study of more than 91,000 participants that used wrist actigraphy implicated 8 SNPs involved in sleep duration including 2 novel sites [26]. The novel locations implicated in this study were AUTS2, a gene involved in chromatin remodeling, and MAPKAP1, a gene involved in the mTORC complex. A subsequent UK biobank study that relied on self-reported sleep duration included over 446,000 people implicated 78 loci for sleep duration with a mean effect of 1.08 minutes per allele and a combined aggregate risk of 20 minutes [25]. Although GWAS studies hold the advantage of large sample sizes and an unbiased way of identifying novel factors, their small effect size limits their ability to shed light on the mechanisms of human sleep regulation. Moreover, since GWAS studies implicate nearby SNPs rather than causally demonstrating that a gene affects sleep, further work needs to be done to reveal how these implicated SNPs affect sleep.

Genes for sleep consolidation, circadian timing of sleep, or altered recovery sleep

Several genes do not have an obvious sleep duration phenotype but change components of sleep architecture such as sleep consolidation, circadian timing of sleep, or altered recovery sleep, suggesting that these components may be regulated by different mechanisms than sleep duration. Indeed, more than a dozen human mutations have been found to alter circadian timing without obvious impact on other aspects of sleep [27]. Mice with a point mutation in exon 9 of the transcription factor ZFHX3 have normal baseline sleep but less NREM recovery after sleep deprivation [28]. In addition, mice lacking MEF2D, a transcription factor enhancer, have more fragmented sleep and a shortened NREM->REM latency [29]. The absence of NF1, a protein involved in the ERK pathway, also leads to more fragmented sleep [30]. Finally, alterations to the histamine arousal system lead to an altered circadian profile of sleep seen from sleep profile of HNMT (Histamine N-methyltransferase) KO mice [31].

Although the classic way of defining sleep relies on neural activity measured through EEG recordings, several recent studies have indicated that genetic alterations in non-neuronal cell types are sufficient to alter sleep. BMAL1 KO mice have ~3 hour increase in NREM sleep, but a brain-specific BMAL1 rescue was unable to restore normal sleep levels [32]. However, the authors found that a muscle-specific BMAL1 rescue restored the WT sleep phenotype, raising the possibility that a signal from the muscle may influence sleep [32]. Another study in flies found that using RNAi to knockdown the metabolic factor EAAT2 solely in ensheathing glia was sufficient to alter sleep [33]. It will be interesting to see what factors from these non-neuronal subtypes subsequently influence neurons.

High throughput screening in zebrafish reveal novel sleep genes

Monitoring the mobile time of zebrafish has also recently proved to be a high-throughput way of discovering new genes related to sleep in vertebrates. Recent work in zebrafish has found that the knockout of neuropeptides QRFP, PROK2, NPY, NPVF, the neuropeptide receptors GPR103A and GPR103B, the growth factor receptor EGFR, and the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNH4A leads to increased locomotor time and the knockout of the neuropeptide NMU leads to decreased locomotor time [34–40]. Crucially the authors were able to show that the novel factors altered the activities of more well-studied mammalian systems such as norephinephrin, galanin, or orexin [35, 36, 39]. Given that most of these zebrafish genetic knockouts represent novel sleep pathways, it will be interesting to learn if they can also alter sleep in mammals. Regardless, findings in both human and zebrafish seem to have a bias towards neuropeptides and their receptors for sleep regulation. Although sleep state transitions and sleep stability occur on the timescale of seconds, other sleep components such as sleep duration, circadian timing of sleep, and sleep homeostasis occur on a minutes-to-hours timescale. Due to their ability to induce neuromodulation and transcriptional changes—changes that occur on the minute-to-hour timescale—neurotransmitters and their receptors are well-poised be involved in sleep regulation, particularly sleep duration, circadian timing of sleep, and sleep homeostasis, which may account for the bias towards neuropeptides and their receptors in sleep regulation.

Concluding remark

A wide variety of approaches in this past decade has uncovered a multitude of genes involved in sleep regulation. The sleep field has also benefited from the use of diverse model organism as well as the acceptance of using locomotor time as a first-pass approximation for sleep. The genetic results have implicated a broad range of biological processes with a heavy emphasis on ion channels, neuropeptides, neuropeptide receptors, synaptic proteins, and transcription factors. The sleep field is now well-positioned to use the genetic evidence to investigate the mechanism for how the body regulates sleep.

Highlights:

Genetics plays a critical role in regulating sleep

Specific genetic effects on REM versus NREM sleep

Genetic differences for sleep consolidation, recovery sleep, and circadian timing of sleep

Human and zebrafish converge on neuropeptides/receptors

Acknowledgments

Our work is supported by NIH grants NS072360 and NS104782 to Y-H.F. and by the William Bowes Neurogenetics Fund to Y-H.F. John Webb is a student in the Neuroscience graduate program at University of California San Francisco.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Nath RD, Bedbrook CN, Abrams MJ, Basinger T, Bois JS, Prober DA, Sternberg PW, Gradinaru V, Goentoro L: The jellyfish Cassiopea exhibits a sleep-like state. Curr Biol 2017, 27:2984–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scammell TE, Arrigoni E, Lipton JO: Neural circuitry of wakefulness and sleep. Neuron 2017, 93:747–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Sugiyama F, Yagami K, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T: Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron 2001, 30:345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatsuki F, Sunagawa GA, Shi S, Susaki EA, Yukinaga H, Perrin D, Sumiyama K, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Fujishima H, Ohno R, Daisuke T, et al. : Involvement of Ca2+-dependent hyperpolarization in sleep duration in mammals. Neuron 2016, 90:70–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunagawa GA, Sumiyama K, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Perrin D, Fujishima H, Ukai H, Nishimura O, Shi S, Ohno R, Narumi R, Shimizu Y et al. :Mammalian reverse genetics without crossing reveals Nr3a as a short-sleeper gene. Cell Reports 2016, 14:662–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida K, Shi S, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Fujishima H, Ohno R, Ueda HR: Leak potassium channels regulate sleep duration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:E9459–E9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.**.Niwa Y, Kanda GN, Yamada RG, Shi S, Sunagawa GA, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Fujishima H, Matsumoto N, Masumoto K, Nagano M, Kasukawa T, et al. : Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors Chrm1 and Chrm3 are essential for REM sleep. Cell Reports 2018, 24:2231–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study systematically knocked out nine different ionotropic nicotinic receptors as well as five metabotropic nicotinic receptors, ultimately finding a double-knockout mouse almost completely devoid of REM sleep.

- 8.Kushida CA, Bergmann BM, Rechtschaffen A: Sleep deprivation in the rat: IV. Paradoxical sleep deprivation. Sleep 1989, 12:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banks GT, Guillaumin MCC, Heise I, Lau OP, Yin M, Bourbia N, Aguilar C, Bowl MR, Esapa C, Brown LA, Hasan S, Tagliatti E, et al. : Forward genetics identifies a novel sleep mutant with sleep state inertia and REM sleep deficits. Sci Advances 2020, 6:eabb3567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seok BS, Bélanger-Nelson E, Provost C, Gibbs S, Mongrain V: The effect of Neuroligin-2 absence on sleep architecture and electroencephalographic activity in mice. Molecular Brain 2018, 11:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.*.Ingiosi AM, Schoch H, Wintler T, Singletary KG, Righelli D, Roser LG, Median E, Risso D, Frank MG, Peixoto L: Shank3 modulates sleep and expression of circadian transcription factors. eLife 2019, 8:e42819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Identified a short sleep phenotype in a mouse model of autism.

- 12.Chen C, Lee P, Liao H, Chang P: Neuroligin 2 R215H mutant mice manifest anxiety, increased prepulse inhibition, and impaired spatial learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2017, 8:257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikhail C, Vaucher A, Jimenez S, Tafti M: ERK signaling pathway regulates sleep duration through activity-induced gene expression during wakefulness. Sci Signaling 2017, 10:eaii9219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funato H, Miyoshi C, Fujiyama T, Kanda T, Sato M, Wang Z, Ma J, Nakane S, Tomita J, Ikkyu A, Kakizaki K, et al. : Forward-genetics analysis of sleep in randomly mutagenized mice. Nature 2016, 539:378–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki A, Yanagisawa M, Greene RW. Loss of Arc attenuates the behavioral and molecular responses for sleep homeostasis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020, 19:10547–10553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda T, Fujiyama T, Miyoshi C, Ikkyu A, Hotta-Hirashima N, Kanno S, Mizuno S, Sugiyama F, Takahashi S, Funato H, Yanagisawa M: A single phosphorylation site of SIK3 regulates daily sleep amounts and sleep need in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115:10458–10463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.*.Shi G, Xing L, Wu D, Bhattacharyya BJ, Jones CR, McMahon T, Chong SYC, Chen JA, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Krystal A, et al. : A rare mutation of βΐ-adrenergic receptor affects sleep/wake behaviors. Neuron 2019, 103:1044–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study found a short sleep mutation in a human family, confirmed that it was causative using a mouse model, and investigated how it changed protein stability and neural activity in vivo.

- 18.Xing L, Shi G, Mostovoy Y, Gentry NW, Fan Z, McMahon T, Kwok P, Jones CR, Ptécěk LJ, Fu Y: Mutant neuropeptide S receptor reduces sleep duration with preserved memory consolidation. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11:eaax2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He Y, Jones CR, Fujiki N, Xu Y, Guo B, Holder JL Jr, Rossner MJ, Nishino S, Fu YH: The transcriptional repressor dec2 regulates sleep length in mammals. Science 2009, 325:866–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellegrino R, Kavakli ΓΗ, Goel N, Cardinale CJ, Dinges DF, Kuna ST, Maislin G, Van Dongen HP, Tufik S, Hogenesch JB, Hakonarson H et al. : A novel bhlhe41 variant is associated with short sleep and resistance to sleep deprivation in humans. Sleep 2014, 37:1327–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirano A, Hsu P, Zhang L, Xing L, McMahon T, Yamazaki M, Ptécěk LJ, Fu Y: DEC2 modulates orexin expression and regulates sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:3434–3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maple AM, Rowe RK, Lifshitz J, Fernadez F, Gallitano AL: Influence of schizophrenia-associated gene Egr3 on sleep behavior and circadian rhythms in mice. J Biol Rhythms 2018, 33:662–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb DJ, Hek K, Chen T, Watson NF, Eiriksdottir G, Byrne EM, Cornelis M, Warby SC, Bandinelli S, Cherkas L, Evans DS, et al. :Novel loci associated with usual sleep duration: the CHARGE consortium genome-wide association study. Mol Psychiatry 2015, 20:1232–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones SE, Tyrrell J, Wood AR, Beaumont RN, Ruth KS, Tuke MA, Yaghootkar H, Hu Y, Teder-Laving M, Hayward C, et al. : Genome-wide association analyses in 128,266 individuals identifies new morningness and sleep duration loci. PLOS Genetics 2016, 12:e1006125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.**.Dashti HS, Jones SE, Wood AR, Lane JM, van Hees VT, Wang H, Rhodes JA, Song Y, Patel K, Anderson SG, et al. : Genome-wide association study identifies genetic loci for self-reported habitual sleep duration supported by accelerometer-derived estimates. Nat Comm 2019, 10:1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the largest sleep GWAS to date, encompassing more than 440,000 adults and discovered 78 loci related to various sleep phenotypes.

- 26.Doherty A, Smith-Byme K, Ferreira T, Holmes MV, Holmes C, Pulit SL, Lindgren CM: GWAS identifies 14 loci for device measured physical activity. Nat Comm 2018, 9:5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balzani E, Lassi G, Maggi S, Sethi S, Parsons MJ, Simon M, Nolan PM, Tucci V: The Zfhx3-mediated axis regulates sleep and interval timing in mice. Cell Reports 2016, 16:615–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi G, Wu D, Ptéček LJ, and Fu Y: Human genetics and sleep behavior. Curr Opitt Neurobiol. 2018, 44:43–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohawk JA, Cox KH, Sato M, Yoo S, Yanagisawa M, Olson EN, Takahashi JS: Neuronal myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2D (MEF2D) is required for normal circadian and sleep behavior in mice. J Neurosci 2019, 39:7958–7967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anastasaki C, Rensing N, Johnson KJ, Wong M, Gutmann DH: Neurofibromatosis type 1 (A/2)-mutant mice exhibit increased sleep fragmentation. J Sleep Research 2018, 28:e12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naganuma F, Nakamura T, Yoshikawa T, Iida T, Miura Y, Karpati A, Matsuzawa T, Yanai A, Mogi A, Mochizuki T, Okamura N, et al. : Histamine A-methyltransferase regulates aggression and the sleep-wake cycle. Sci Reports 2017, 7:15899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehlen JC, Brager AJ, Baggs J, Pinckney L, Gray CL, DeBruyne JP, Esser KA, Takahashi JS, Paul KN: Bmall function in skeletal muscle regulates sleep. eLife 2017, 6:e26557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stahl BA, Peco E, Davla S, Murakami K, Moreno NAC, van Meyel DJ, Keene ACL: The taurine transporter Eaat2 functions in ensheathing glia to modulate sleep and metabolic rate. Curr Biol 2018, 28:3700–3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen A, Chiu CN, Mosser EA, Khan S, Spence R, Prober DA: QRFP and its receptors regulate locomotor activity and sleep in zebrafish. J Neurosci 2016, 36:1823–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen S, Reichert S, Singh C, Oikonomou G, Rihel J, Prober DA: Light-dependent regulation of sleep and wake states by prokineticin 2 in zebrafish. Neuron 2017, 95:153–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh C, Rihel J, Prober DA: Neuropeptide Y regulates sleep by modulating noradrenergic signaling. Curr Biol 2017, 27:3796–3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee DA, Andreev A, Truong TV, Chen A, Hill AJ, Oikonomou G, Pham U, Hong YK, Tran S, Glass L, Sapin V, et al. : Genetic and neuronal regulation of sleep by neuropeptide VF. Elife 2017, 6:25727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee DA, Liu J, Hong Y, Lane JM, Hill AJ, Hou SL, Wang H, Oikonomou G, Pham U, Engle J, Saxena R, et al. : Evolutionarily conserved regulation of sleep by epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Sci Advances 2019, 5:eaax4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yelin-Bekerman L, Elbaz I, Diber A, Dahary D, Gibbs-Bar L, Alon S, Lerer-Goldshtein T, Appelbaum L: Hypocretin neuron-specific transcriptome profiling identifies the sleep modulator Kcnh4a. eLife 2015, 4:e08638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiu CN, Rihel J, Lee DA, Singh C, Mosser EA, Chen S, Sapin V, Pham U, Engle J, Niles BJ, Montz CJ, et al. : A zebrafish genetic screen identifies neuromedin U as a regulator of sleep/wake states. Neuron 2016, 89:842–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]