Abstract

Microbial exopolysaccharides (EPS) are high molecular weight polymers having different sugar residues. EPS have potential applications in different fields, such as medicine, food and environment. Therefore, there is a growing interest in production, characterization and application of EPS from different microorganisms. The present study designed to investigate the production and characterization of EPS from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19 isolated from Morus nigra L. fruits as well as to examine their potential emulsifying properties. Effect of NaCl concentration, incubation period and pH on the production of EPS was studied. The maximum EPS production by yeast was achieved at 10% NaCl (9741.84 mg/l). The best incubation time for production of EPS was 5 days. Production of EPS decreased under neutral condition and increased at acidic and alkaline condition. The structural feature of EPS was examined by FT-IR and NMR spectral analysis and confirmed the presence of glucose, glucopyranose and galactose. The isolated EPS showed higher emulsification capacity with emulsification activity of 71% and emulsifying index of 60%. The EPS gave strong emulsification for farnesol and was more effective than sodium dodecyl sulphate, a reference emulsifier, in enhancing the herbicidal activity of farnesol against Melilotus indicus under greenhouse condition. The results suggest that the EPS produced by YMM19 strain has a potential to be used as emulsifying agent in pesticide formulations.

Keywords: Exopolysaccharides, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19, Bioemulsifiers, Herbicidal activity

Introduction

Microorganisms manufacture a broad range of polysaccharide polymers including extracellular, intracellular and structural polysaccharides (Jindal and Khattar 2018; Rana and Upadhyay 2020; Whitfield et al. 2020; Zikmanis et al. 2020). Extracellular polysaccharides or exopolysaccharides (EPS) are high molecular weight polymeric substances that are produced by microorganisms into their surrounding environment (Gupta and Thakur 2016). In general, EPS are made of sugar residues and some non-carbohydrate constituents, such as proteins, nucleic acids, phospholipids, succinate, pyruvate and acetate (Gupta et al. 2021; Tiwari et al. 2020). EPS have several functions to the producing microorganisms, such as protecting cells from desiccation and environment, phage attacks, antibiotics and biofilm formation (Kumar et al. 2007). Under extreme condition, microorganisms produce EPS with remarkable characteristics. EPS protect microorganisms from extreme environmental conditions, such as salinity, extreme temperature, desiccation and UV radiation (Poli et al., 2010; Hamidi et al. 2020; Joulak et al. 2020; Nguyen et al. 2020; Zeng et al. 2020; Ye et al. 2021). EPS are eco-friendly, non-toxic and low cost substances (Govarthanan et al. 2020; Siddharth et al. 2021). Microbial EPS have several industrial applications in the health, food and environment (Kavitake et al. 2020; Kielak et al. 2017; Krishnaswamy et al. 2021; Nwodo et al. 2012; Rosenberg and Ron 1997; Satpute et al. 2018; Tiwari et al. 2020). Some EPS are being used as stabiliser, emulsifiers and thickeners in food industry. Other EPS exhibit antioxidant, antiviral, immunostimulatory, antiulcer, lowering blood cholesterol and antitumor activities (Madhuri and Rabhakar 2014). Therefore, they have a potential to be used in therapeutic and pharmaceutical industries. Other EPS have a potential to improve the environment by enhancing biodegradation of pollutants and removing hydrocarbons and heavy metals (Lee et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2010).

Biosurfactants, including bioemulsifiers, are surface active natural molecules formed by microorganisms, such as fungi, bacteria, actinomycetes and yeasts (Calvo et al. 2009). Biosurfactants have the ability to reduce surface tension of water and interfacial tensions of water/hydrocarbon mixtures. They have a high molecular weight and produce stable emulsions and suspensions (Uzoigwe et al. 2015). Due to the problems associated with the use and production of synthetic surfactants of petroleum origin, such low biodegradability, toxicity and the environmental risk of their by-products, biosurfactants have been investigated to replace synthetic surfactants in industrial and environmental applications (Banat et al. 2000; Luna et al. 2013). Exopolysaccharides (EPS) are among biosurfactants which attract much attention because of their physicochemical properties, excellent surface activity, low toxicity, high specificity, biodegradability and effectiveness under extreme conditions (Desai and Banat 1997). Therefore, various microorganisms have been screened for the production of EPS and their bio-emulsifying properties have been studied (Das et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2012; Santos et al. 2013; Lopes et al. 2014; Maalej et al. 2015; Hassan and Ibrahim 2017). Several studies indicate the production of EPS by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa with various applications (Hamidi et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Medina-Ramirez et al. 2020; Vázquez-Rodríguez et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020).

Farnesol is a colorless acyclic sesquiterpene alcohol found in many essential plant oils such as lemon grass, neroli, cyclamen, tuberose, rose and musk (Bakkali et al., 2008). It has been reported that farnesol has different pharmacological activities such as antimicrobial, antitumor and antioxidant effects (Jung et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019). Also, farnesol has been shown to possess insecticidal activity (Awad, 2012; Al-Nagar et al., 2020; Abdelgaleil et al., 2020) and herbicidal activity (Saad et al., 2019).

Therefore, the main objectives of the present study were to isolate a yeast strain capable of producing EPS, study the effect of salinity, pH and incubation time on the production of EPS by R. mucilaginosa YMM19, characterize the produced EPS, investigate the bio-emulsifying activity of the EPS and examine the effect of EPS on the herbicidal activity of farnesol, a natural sesquiterpene, to explore its possible application in pesticide formulations.

Materials and methods

Isolation of EPS producing yeast

Exopolysaccharides (EPS) producing yeast was isolated from black mulberry fruits (Morus nigra L.) collected from Beheira Governorate, Egypt. Aseptically, five mulberry fruits were homogenized in 10 ml sterilized distilled water by a glass Teflon homogenizer to give homogenous suspension. Then, 0.1 ml of fruit suspension was transferred to a Petri plate of potatoes dextrose agar (PDA) media (pH 7). Inoculated plates were incubated at 28 °C and observed after 3 days. Resulted yeast colonies were purified by repeated streaking on PDA plates. The pure colonies obtained were transferred to a fresh PDA slant, subcultured and stored at 4 °C.

Morphological and molecular identification of yeast

Isolated yeast was morphologically identified on the basis of culture and microscopic characteristics after cultivation on PDA media at 28 °C for 3 days. For molecular characterization, yeast isolate was cultured in potato dextrose broth (PDB) and genomic DNA was prepared according to Quick-DNA™ Fungal Microprep Kit (Zymo research #D6007). The D1/D2 domains of 26S rRNA gene of the large subunit ribosome (LSU) was PCR amplified using the primers pairs of NL1 (5′-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG-3′) and NL4 (5′-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG-3′) (O’Donnell, 1993). The PCR were performed in 50 μl reaction volume of 1 l (20 Pico mol) of each primer, 25 l MyTaq Red Mix, 8 l (25 ng) of template DNA and 15 l nuclease free water. PCR reaction was done under initial denaturation of 94 °C for 6 min, followed by 35 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 56 °C and 1 min at 72 °C and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR reaction was done using a ThermoHybaid PCR Sprint Thermal Cycler (Thermo Electron, USA) instrument. The amplification products were purified using GeneJET™ PCR purification kit (Thermo K0701). The size and purity of the amplified products were confirmed in 1% agarose gel. Then, the PCR products (≈ 600 bp) were sequenced on both strands using NL1 and NL4 primers by ABI PRISM 3700 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The BLASTn tool was used to obtain the similarity of the nucleotide sequences with corresponding sequences databases of NCBI to find the most closely related sequences. Finally, the sequence was submitted to GenBank. Moreover, a neighbor-joining distance-based phylogenetic tree of sequence was conducted using MEGA version 6 (Tamura et al. 2013).

Inoculum preparation and culture condition

The PDB medium was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG24 8PW, UK) and used for yeast cultivation and EPS production. R. mucilaginosa YMM19 was cultivated in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flask (containing 50 ml of PDB medium) at 200 rpm and 28 °C. The inoculum was made by culturing the yeast strain in PDB for 3 days at 200 rpm, 28 °C and pH 6.5. The yeast cell numbers (105 cell/ml) were obtained and aliquots of 1% (v/v) of this suspension were used as an inoculum for EPS production studies.

Extraction and purification of EPS

The yeast cultures were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 10 min. Two volumes of 95% ethanol was added to the supernatant and left at 4 °C for 48 h. The EPS was pellet down by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min and then it was dissolved in distilled water and estimated via phenol sulphuric acid method using glucose as standard (Dubois et al. 1956). Culture optical density (OD) of the YMM19 strain was determined spectrophotometrically against distilled water with a wavelength of 600 nm.

Effect of salinity on EPS production

The YMM19 strain was examined for their EPS production under salt stress in PDB enriched with different concentrations of NaCl (5, 10, 15 and 20% w/v) at 200 rpm, pH 6.5 and 28 °C. After 3 days of incubation, yeast growth (OD600nm) and EPS production were determined. Three replicates of each experiment were done.

Effect of pH on EPS production

The YMM19 strain was tested for their EPS production under pH stress in PDB at 200 rpm and 28 °C. The pH range was chosen between 2.5 and 10.5 after adjusting with HCl and NaOH. Yeast growth and EPS production were measured after 3 days of incubation. Three replicates of each experiment were done.

Effect of incubation time on EPS production

Effect of different incubation periods on EPS production by YMM19 strain was investigated in PDB at 200 rpm, pH 6.5 and 28 °C. YMM19 growth and EPS production were estimated after 3, 5, 7 and 9 days of incubation. Three replicates of each experiment were done.

Fourier transform infrared analysis of EPS

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy is usually used for preliminary identification of the functional groups constituting the EPS. The EPS FT-IR spectrum was recorded with a PerkinElmer spectrum two FT-IR system (Perkin Elmer Spectrum Version 10.5.1, USA) in wave number range from 400 to 4000 cm−1, at room temperature.

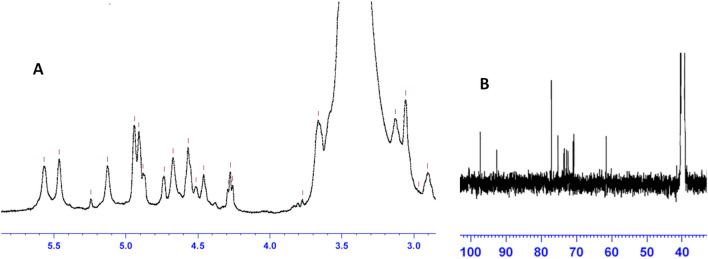

NMR analysis of EPS

NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker BioSpin GmbH spectrometer (400 MHz). A sample (10 mg) of lyophilized EPS was dissolved in 0.5 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (99.9%). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were taken at 25 °C, and the chemical shift was expressed in parts per million (ppm).

Solubility of EPS

Solubility of yeast EPS was examined in various solvents. A little amount of EPS were mixed with solvent (distilled water, chloroform and methanol) in 2 ml test tube, vortexed for 1 min and EPS dissolution was observed.

Determination of emulsifying potential of EPS

Emulsifying activity of EPS was measured using a modified method of Cooper and Goldenberg, 1987. In this method, xylene was added to aqueous phase containing 1% of the exopolysaccharide (hydrocarbon: exopolysaccharides in a ratio of 3:2, v/v) and vigorously vortexed for 2 min. The heights of xylene layer and aqueous layers were measured at every 24-h interval (1, 24 and 168 h). The emulsification activity (% EA) was determined after 1 h whereas the emulsion stability was determined as emulsification index (% EI) after 24 and 168 h (or E24 & E168). The % EA and % EI were defined as the percentage of the emulsion layer height compared to the total height after 24 h. EA of EPS was compared with sodium dodecyl sulphate (1% w/v) as emulsifiers. The EA (%) was calculated as the height of the emulsion layer, divided by the total height, multiplied by100.

Determination of emulsion type

Emulsion type of the tested EPS was determined by filter paper wetting test according to Rieger (1986). One droplet (25 μl) of EPS solution 1% was carefully dropped on the filter paper. In oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion type, the droplet disperses rapidly on the filter paper. While, in water-in-oil (W/O) type, it remains as a droplet on the filter paper.

Determination the effect of EPS on herbicidal activity of farnesol

Thirty seeds of Melilotus indicus (L.) All. were planted in plastic pot (10 cm diameter by 15 cm height) filled with clay soil (clay: sand 2:1). Seedlings were grown in the greenhouse under natural sunlight at 30 ± 2o C. Farnesol was dissolved in xylene then solutions of farnesol were prepared in distilled water containing EPS and/or sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) as surfactants. Farnesol was selected in this study based on its pronounced herbicidal activity described by us (Saad et al., 2019). The water solutions containing 0.25% (v/v) xylene as a solvent and 0.2% (v/v) of EPS/or SDS as emulsifying agents. Treatments with distilled water alone and/or DW containing xylene (0.25% v/v) and EPS/or SDS (0.2%) were served as the controls. Solutions were sprayed on weed seedlings foliage at concentration of 1% (3 ml for each replicate) after 15 days of sowing. Three replicates were used in each treatment. Treated plants were kept under observation for 4 days after treatment and visual plants injury (burning, necrosis, chlorosis, leaf distortion and stunting) were recorded. After 4 days, the shoot fresh weights were measured and the shoots were oven-dried at 75 °C for 72 h and the dry weights were measured.

Statistical analysis

All the trials were done in three replicates. The obtained data were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). The experimental data were subjected to one-way ANOVA and Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) method for all pairwise comparisons among factors means by the Minitab® 16.1.0 program (Minitab Inc, PA, USA).

Results

Yeast identification

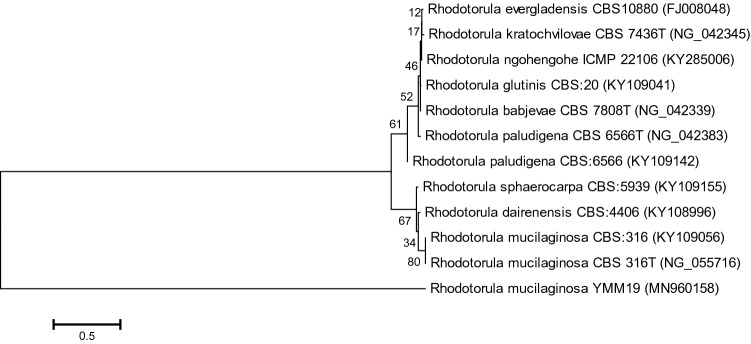

One yeast isolate (YMM19) was isolated from mulberry fruits. According to morphological characteristics, the yeast strain was belonging to genus Rhodotorula. The D1/D2 region of 26S rRNA gene was PCR amplified using NL1 and NL4 primers. Same primers were used for sequencing of amplified products. After editing, the attained sequence was submitted to the GenBank under the accession numbers of MN960158. The phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree was constructed for yeast strain with their close relatives using MEGA 6.0 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19 and closely related species constructed based on the D1/D2 domain (26S rRNA gene) sequence. Bootstrap consensus tree was drawn by multiple sequence alignment with neighbor-joining method using MEGA 6.0 software

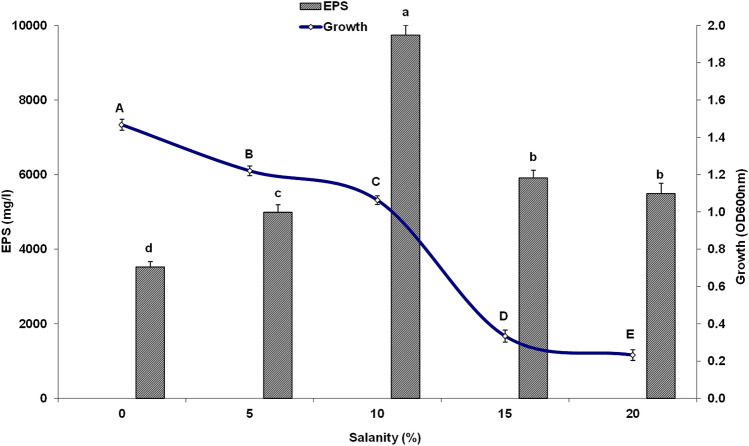

Effect of salinity on EPS production

The yeast strain YMM19 was studied for their growth and EPS production under NaCl stress conditions (Fig. 2). The maximum yeast growth (1.47 OD600nm) was obtained in the broth medium lacking NaCl, followed by that supplemented with 5% NaCl (1.22 OD600nm), 10% NaCl (1.06 OD600nm), 15% NaCl (0.33 OD600nm), and 20% NaCl (0.23 OD600nm), respectively. However, the production of EPS by the yeast increased with the increase in the salt concentration and maximum EPS was observed at 10% NaCl (9741.84 mg/l).

Fig. 2.

Effect of NaCl (%) on growth and EPS production by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19 cultured in PDB medium at 200 rpm, 28 °C after 3 days and pH 6.5. Data were presented as means of three replicates with standard deviation, means (bars) that do not share a letter (A–E) are significantly different according to Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) method at p < 0.05

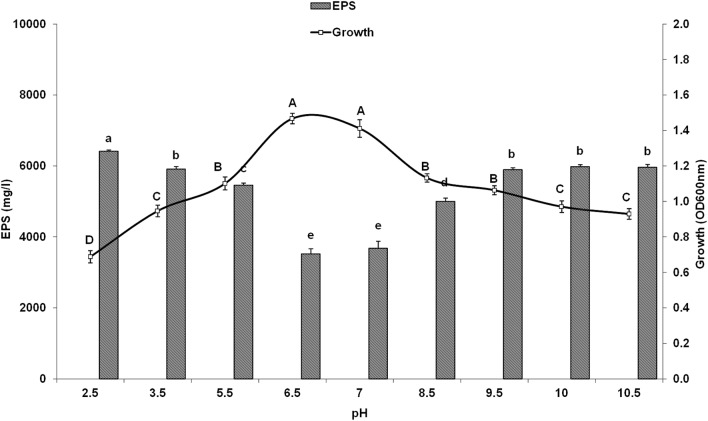

Effect of pH on EPS production

The effect of pH on yeast growth and production of EPS is shown in Fig. 3. The maximum growth of YMM19 strain was observed at pH 6.5 and decreased in the alkaline and acidic medium. In spite of this, the maximum EPS production was under the alkaline and acidic conditions and was decreased at neutral conditions.

Fig. 3.

Influence of initial pH on production of EPS by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19 cultured in PDB medium at 200 rpm, 28 °C and after 3 days. Data were presented as means of three replicates with standard deviation, means (bars) that do not share a letter (A to E) are significantly different according to Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) method at p < 0.05

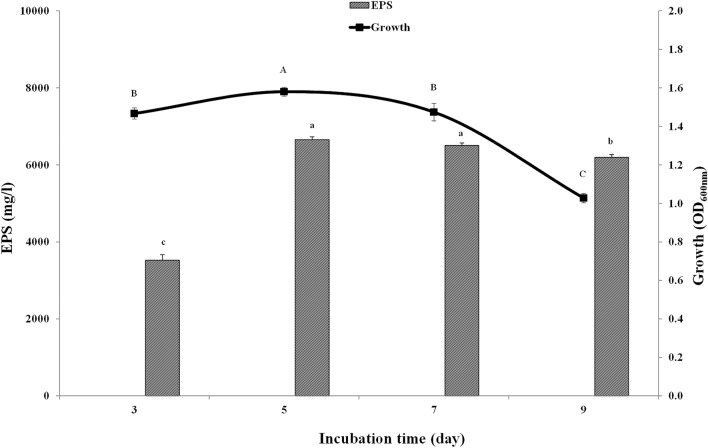

Effect of incubation time on EPS production

The effect of incubation time on the growth of YMM19 and EPS production is shown in Fig. 4. The growth of YMM19 was slowly increased with incubation time until reached to the maximum after 5 days and severely decreased after 7 and 9 days. The EPS production was very low after 3 days and strongly increased and reached to the maximum after 5 and 7 days and then slowly decreased after 9 days. In general, the results showed that the maximum growth and EPS production were observed after 5 days.

Fig. 4.

Effect of different incubation periods on production of EPSs by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19 cultured in PDB medium at 200 rpm, 28 °C and pH 6.5. Data were presented as means of three replicates with standard deviation, means (bars) that do not share a letter are significantly different according to Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) method at p < 0.05

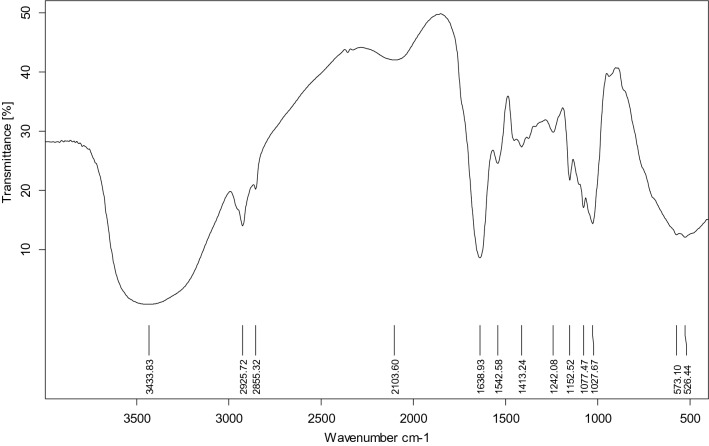

FT-IR and NMR analysis of EPS from strain YMM19

The FT-IR spectrum of YMM19 EPS shows a range of distinctive absorption bands of polysaccharides (Fig. 5). The intense broad band at 3433.83 cm−1 was related to –OH groups. The absorption band at 2925.72 cm−1 was due to the aliphatic C–H groups. The band at 1638.93 cm−1 was corresponded to the C=O stretching of polysaccharide moiety. The EPS band at 1242.08 cm−1 may due to a pyranose ring. The C–O stretching bands were observed at 1152.52 cm−1, 1077.47 cm−1 and 1027.67 cm−1 in fingerprint region (1200–950 cm−1) and these groups linked to the ether or beta-glycosidic linkages of polysaccharides. The EPS had no uronic acids due to the absence of absorption band at 1726 cm−1.

Fig. 5.

FT-IR spectrum of the EPSs produced by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19. IR absorption bands: 3433.83 cm−1 = stretching of –OH (hydroxyl groups); 2925.72 cm−1 = C–H stretching of aliphatic hydrocarbon; 1638.93 cm−1 = C=O bond stretches of polysaccharide moiety; 1027.67 cm−1 = C–O bond stretches of ether groups of polysaccharides

In the 1H NMR spectrum, the anomeric region (4.5–5.7 ppm) signals were often used to differentiate the anomeric protons of sugar residues in polysaccharides. The ring proton region (2.9–4.4 ppm) was assigned to protons attached to C2–C6 and usually poorly resolved due to their overlapping chemical shifts. As shown in the 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. 6A), the signals in 4.93, 4.73 and 4.56 ppm indicated EPS contained both α- and β-type glycosidic linkages. The 13CNMR spectrum (Fig. 6B) was also included anomeric carbon regions (90–100 ppm) and ring carbon regions (60–80 ppm). The chemical shifts of carbon signals indicated the presence of β-d-glucopyranose and β-d-galactose bound to glucose. The absence of carbon signals at δ > 170 and at δ < 20 indicated the absence of uronic acid and rhamnose, respectively.

Fig. 6.

1H NMR (A) and 13C NMR (B) spectra of EPSs produced by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YMM19. 1H NMR: δ 4.5–5.7 ppm = anomeric protons of sugar residues in polysaccharides; δ 2.9–4.4 ppm = protons attached to C2–C6 in rings; δ 4.93, 4.73 and 4.56 ppm = protons of α- and β-type glycosidic linkages; 13CNMR: δ 90–100 ppm = signals of carbons in anomeric carbon regions; δ 60–80 ppm signals of carbon in ring carbon regions

EPS solubility

The EPS of strain YMM19 was soluble in distilled water and insoluble in methanol and chloroform. This nature of EPS is compatible with general characteristics of polysaccharides.

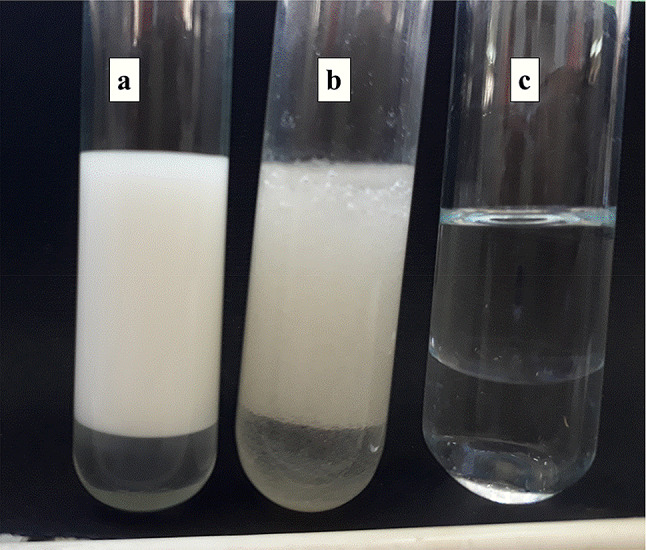

Emulsifying activity of EPS

The emulsification activity (% EA) of the test EPS produced by YMM19 with xylene (71%) was comparable with the emulsification activity of SDS (74%), a reference emulsifier. In addition, emulsifying index of EPS produced by YMM19 was 60% after 24 h (Table 1). Moreover, EPS showed emulsifying index slightly less than SDS after 24 h and 168 h. On the other hand, the type of emulsion test showed that the emulsion formed in the presence of EPS of strain YMM19 was oil-in-water (O/W) type (Fig. 7).

Table 1.

Emulsifying activity of EPS with xylene and its stability after 1, 24 and 168 ha

| Compound | Emulsifying activity (% EA) | Emulsifying index (% EI24 h) | Emulsifying index (% EI168 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPS | 71 ± 1.41ab | 60 ± 1.41b | 49 ± 1.41b |

| SDS | 74 ± 1.41a | 64 ± 1.41a | 59 ± 1.41a |

| Cont. (W) | 53 ± 4.24b | 0.0 ± 0.0c | 0.0 ± 0.0c |

aData are expressed as mean values ± SD from experiments with three replicates

bMean values within a column sharing the same letter are not significantly different at the 0.05 probability level

Fig. 7.

The emulsion stability of 1% of sodium dodecyl sulphate (a); 1% exopolysaccharides (b), and distilled water (c) with xylene after 24 h

Herbicidal activity of farnesol/EPS mixture

A mixture containing EPS (0.2%) as emulsifying against and farnesol (1%), a natural sesquiterpene with pronounced herbicidal activity, in distilled water was prepared and tested for herbicidal activity against M. indicus. The prepared mixture showed strong reduction in weed fresh weight (87.6%) and dry weight (63.4%) (Table 2). The mixture was more effective than the mixture of farnesol + SDS against the weed. At the same time, the EPS alone showed no herbicidal activity against the weed. Moreover, complete death for the weed was observed after 4 days of treatment with farnesol + EPS mixture (Fig. 8).

Table 2.

Effect of farnesol on fresh and dry weight of Melilotus indicus shoot after 4 days of foliar treatment at application rate of 1%a

| Treatment | Fresh weight (mg) | (%) Rb | Dry weight (mg) | (%) R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farnesol + EPS | 2.73 ± 0.21cb | 87.6 | 2.63 ± 0.23b | 63.4 |

| Farnesol + SDS | 5.33 ± 0.61c | 75.4 | 3.37 ± 0.72b | 52.1 |

| EPS | 22.76 ± 6.0a | − 5.1 | 6.30 ± 1.45a | 11.3 |

| SDS | 15.6 ± 2.74b | 28.1 | 3.70 ± 0.43b | 47.9 |

| Cont. (W) | 21.7 ± 3.57a | 0.0 | 7.13 ± 1.84a | 0.0 |

R reduction, EPS exopolysaccharide, SDS sodium dodecyl sulphate, W water

aData are expressed as mean values ± SD from experiments with three replicates of 20 seeds each

bMean values within a column sharing the same letter are not significantly different at the 0.05 probability level

Fig. 8.

Post emergence herbicidal activity of farnesol against M. indicus 4 d after foliar application. a 1% farnesol solutions containing 0.2% EPS; b 1% farnesol solutions containing 0.2% SDS; c control treatments sprayed with water

Discussion

EPSs produced by microorganisms have wide applications in medicine, food and industry (Banerjee et al. 2020; Hamidi et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Medina-Ramirez et al. 2020; Seveiri et al. 2020; Vázquez-Rodríguez et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). One of these interesting applications is the use EPSs as surfactants and emulsifiers. In fact, EPSs produced by microorganisms can be used in food industries to form emulsions, such as jellies, sauces, salad dressing and jam and in pesticide formulations to form products, such as emulsion concentrates and suspension concentrates. Also EPSs can be used to stabilize food and pesticide products during transportation and storage (Kavitake et al. 2020; Kielak et al. 2017; Krishnaswamy et al. 2021; Satpute et al. 2018; Tiwari et al. 2020). In fact, some EPS are currently used in food industry, for example, xanthan gum is added to improve the texture, stability, flavour and shelf life of many foods (Imeson 2010). Levan is used as a stabiliser, an emulsifier, a formulation aid, surface-finishing agent, an encapsulating agent and a carrier of flavours and fragrances (Han and Clarke 1990). Dextran is used as thickener for jam and ice cream (Zannini et al., 2016). Also, inulin is used to enhance the quality of the food products acting as texturiser, emulsion stabiliser and partial fat replacer (Franck 2002).

Several studies indicate the potential of R. mucilaginosa as an EPS producer (Hamidi et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Medina-Ramirez et al. 2020; Vázquez-Rodríguez et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study explaining the production of EPS from R. mucilaginosa YMM19 under salt stress as well as the effect of some other factors on the production of EPS from this yeast strain. Based on the molecular analysis of nucleotide sequence the yeast strain YMM19 was identified as R. mucilaginosa with a high similarity of 99.28%.

The results of the current study revealed that the production of EPS by the yeast increased with the increase in the salt concentration and maximum EPS production was observed at 10% NaCl. Similarly, Silambarasan et al. (2019) found that the EPS yield increased constantly with increasing concentrations of NaCl in the growth media of yeast Rhodotorula sp. strain CAH2. Likewise, Sheng et al. (2006) stated that the EPS production by a bacterial strain (Rhodopseudomonas acidophila) increased at high NaCl concentrations. The increased production under salt stress condition is due to that the EPS may be responsible for yeast cells protection.

The maximum EPS production was observed under the alkaline and acidic conditions and the production was decreased at neutral conditions. It has been reported that the production of EPS by Bacillus subtilis SH1 increased with increasing of alkaline level (Hassan and Ibrahim, 2017). In agreement with our results, Kim et al. (2006) observed that the optimum pH for cell growth of Ganoderma lucidum fungus was lower than that for EPS formation. However, Darwish et al. (2019) reported that the optimum cell growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and maximum EPS production were achieved at the same pH (6.0). These results suggest that the alkaline and acidic stresses increase the EPS production significantly. On the other hand, the results showed that the maximum growth and EPS production were observed after 5 days. These results are consistent with other studies on the EPS production by B. subtilis MTCC 121 (Vijayabaskar et al. 2011), B. subtilis SH1 (Hassan and Ibrahim, 2017), and Pseudomonas stutzeri AS22 (Maalej et al. 2015).

The spectra of FT-IR, 1H NMR and 13C NMR for the isolated EPS showed characteristic bands and signals of polysaccharides. The absorption bands for –OH groups, the aliphatic C–H groups, the C=O stretching, a pyranose ring and the C–O stretching were observed and matched with those previously reported in the literature (Parikh and Madamwar 2006; Cao et al. 2017). The IR bands in fingerprint region (1200–950 cm−1) indicated the presence of β-glycosidic linkages (Ye et al. 2009). Also, IR data confirmed the absence of uronic acids (Wang et al. 2017). Similarly, the 1H NMR and 13CNMR spectra revealed the presence of anomeric protons and carbons, sugar protons and carbons, α- and β-type glycosidic linkages, β-d-glucopyranose and β-d-galactose bound to glucose. The presence of these moieties was also confirmed by comparing their chemical shifts with those reported in the literature (Ismail and Nampoothiri, 2010; Synytsya and Novák 2013; Ma et al. 2018).

The results of solubility tests showed that the EPS of strain YMM19 was insoluble in organic solvents (e.g. methanol and chloroform) and highly soluble water. These findings were supported by the previous results reported by Castellane et al. (2015) and Mirzaei Seveiri et al. (2020). On the other hand, EPS of strain YMM19 revealed high emulsification activity. Emulsification capacity (60% after 24 h) of EPS of strain YMM19 was higher than emulsification capacity of other EPS produced by B. cereus (48%) (Velázquez-Aradillas et al. 2011) and B. licheniformis MS3 (36%) (Biria et al. 2009). However, emulsification capacity of EPS produced by YMM19 was lower than surfactin (emulsification index = 64.4%) produced by B. subtilis PTCC 1696 (Ghojavand et al. 2008). The pronounced emulsification property of EPS observed in this study indicates its promising applications in various possible environmental and industrial fields. Also, EPS of strain YMM19 produced O/W emulsion. This type of emulsion is commonly used in food preparations and in pesticide formulation which indicate that this EPS may find wide applications in food and pesticide industries (Anvari and Joyner 2018; Feng et al., 2018).

The mixture containing EPS (0.2%) and farnesol (1%) showed interesting herbicidal activity against M. indicus as complete death for the weed was observed after 4 days of treatment. These results indicated that EPS could be used as a natural emulsifier in herbicide formulations. In agreement with our results, Appaiah and Karanth (1991) stated that EPS produced by Pseudomonas trahcida was effective in emulsifying several insecticides. In addition, microbial strains of Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Halomonas, Bacillus, Arthrobacter, Enterobacter, Rhodococcus and yeast have shown to produce EPS with surface active properties (Satpute et al. 2010). Furthermore, it has been reported that several EPSs were also used as surfactants and emulsifiers (Kavitake et al. 2020; Kielak et al. 2017; Krishnaswamy et al. 2021; Rosenberg and Ron 1997; Satpute et al. 2018; Tiwari et al. 2020).

In fact, in recent years, there has been an interest in replacing conventional or synthetic emulsifiers by natural polymeric emulsifiers in pesticide formulations. The natural emulsifiers are safer, biodegradable and ecofriendly (Rodrigues et al. 2006). Based on the results of this study, EPS could be a useful natural emulsifier in food and pesticide industries.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study show that R. mucilaginosa YMM19 represents a valuable source of new EPS with remarkable emulsification properties. Also, the results indicate the possible use of EPS produced by YMM19 as emulsifier in herbicide formulations to ensure complete coverage to treated surfaces and enhance the penetration and translocation of active ingredient inside the target weeds.

Author contributions

YMMM and MMGS designed the work. YMMM and MMGS conducted the experiments. YMMM, MMGS and SAMA analyzed and interpreted the results. YMMM, MMGS and SAMA drafted the manuscript. SAMA wrote the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

References

- Abdelgaleil SAM, Abou-Taleb HK, Al-Nagar NMA, Shawir MS. Antifeedant, growth regulatory and biochemical effects of terpenes and phenylpropenes on Spodoptera littoralis Boisduval. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2020;40:423–433. doi: 10.1007/s42690-019-00093-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nagar NMA, Abou-Taleb HK, Shawir MS, Abdelgaleil SAM. Comparative toxicity, growth inhibitory and biochemical effects of terpenes and phenylpropenes on Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.) J Asia Pac Entomol. 2020;23:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2019.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anvari M, Joyner HS. Effect of fish gelatin and gum arabic interactions on concentrated emulsion large amplitude oscillatory shear behavior and tribological properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;79:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appaiah AKA, Karanth NGK. Insecticide specific emulsifier production by hexachlorocyclohexane utilizing Pseudomonas tralucida Ptm+ strain. Biotechnol Lett. 1991;13:371–374. doi: 10.1007/BF01027685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awad HH. Effect of Bacillus thuringiensis and farnesol on haemocytes response and lysozymal activity of the black cut worm Agrotis ipsilon larvae. Asian J Biol Sci. 2012;5:157–170. doi: 10.3923/ajbs.2012.157.170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkali F, Averbeck S, Averbeck D, Idaomar M. Biological effects of essential oils—a review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:446–475. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banat IM, Makkar RS, Cameotra SS. Potential commercial applications of microbial surfactants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;53:495–508. doi: 10.1007/s002530051648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Das D, Rudra SG, Mazumder K, Andler R, Bandopadhyay R. Characterization of exopolysaccharide produced by Pseudomonas sp. PFAB4 for synthesis of EPS-coated AgNPs with antimicrobial properties. J Polym Environ. 2020;28:242–256. doi: 10.1007/s10924-019-01602-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biria D, Maghsoudi E, Roostaazad R, Dadafarin H, Sahebghadam Lotfi A, Amoozegar MA. Purification and characterization of a novel biosurfactant produced by Bacillus licheniformis MS3. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;26:871–878. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-0246-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo C, Manzanera M, Silva-Castro GA, Uad I, Gonzalez-Lopez J. Application of bioemulsifiers in soil oil bioremediation processes. Future Prospects Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:3634–3640. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Wang Z, Shang Z, Zhao J. Classification and identification of Rhodobryum roseum Limpr and its adulterants based on Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and chemometrics. PLoS ONE. 2017;16:2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172359.e0172359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellane TC, Persona MR, Campanharo JC, de Macedo Lemos EG. Production of exopolysaccharide from rhizobia with potential biotechnological and bioremediation applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;74:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Jiang X, Xu M, Zhang M, Huang R, Huang J, Qi F. Co-production of farnesol and coenzyme Q10 from metabolically engineered Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18:98. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1145-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DG, Goldenberg BG. Surface-active agents from 2 Bacillus species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:224–229. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.2.224-229.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish AA, Al-Bar OA, Yousef RH, Moselhy SS, Ahmed YM, Hakeen KR. Production of antioxidant exopolysaccharide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilizing heavey oil as a solo carbon source. Phcog Res. 2019;11:378–383. doi: 10.4103/pr.pr_40_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Mukherjee S, Sen R. Improved bioavailability and biodegradation of a model polyaromatic hydrocarbon by a biosurfactant producing bacterium of marine origin. Chemosphere. 2008;72:1229–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai JD, Banat IM. Microbial production of surfactants and their commercial potential. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:47–64. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.47-64.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Chen Q, Wu X, Jafari SM, McClements DJ. Formulation of oil-in-water emulsions for pesticide applications: impact of surfactant type and concentration on physical stability. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:21742–21751. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2183-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck A. Technological functionality of inulin and oligofructose. Br J Nutr. 2002;87(Suppl 2):S287–291. doi: 10.1079/BJN/2002550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghojavand H, Vahabzadeh F, Roayaei E, Shahraki AK. Production and properties of a biosurfactant obtained from a member of the Bacillus subtilis group (PTCC 1696) J Colloid Interface Sci. 2008;324:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govarthanan M, Jeon C-H, Jeon Y-H, Kwon J-H, Bae H, Kim W. Non-toxic nano approach for wastewater treatment using Chlorella vulgaris exopolysaccharides immobilized in iron-magnetic nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;162:1241–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Thakur IS. Study of optimization of wastewater contaminant removal along with extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) production by a thermotolerant Bacillus sp. ISTVK1 isolated from heat shocked sewage sludge. Bioresour Technol. 2016;213:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Rathour R, Dupont CL, Kaul D, Thakur IS. Genomic insights into waste valorized extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) produced by Bacillus sp. ISTL8. Environ Res. 2021;192:110277. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi M, Gholipour AR, Delattre C, Sesdighi F, Seveiri RM, Pasdaran A, Kheirandish S, Pierre G, Kozani PS, Kozani PS. Production, characterization and biological activities of exopolysaccharides from a new cold-adapted yeast: Rhodotorula mucilaginosa sp. GUMS16. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;151:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han YW, Clarke MA. Production and characterization of microbial levan. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38:393–396. doi: 10.1021/jf00092a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan SW, Ibrahim HA. Production, characterization and valuable applications of exopolysaccharides from marine Bacillus subtilis SH1. Pol J Microbiol. 2017;66:449–461. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.7001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imeson A. Food stabilisers, thickening and gelling agents. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail B, Nampoothiri KM. Production, purification and structural characterization of an exopolysaccharide produced by a probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum MTCC 9510. Arch Microbiol. 2010;192:1049–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0636-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal N, Khattar JS. Microbial polysaccharides in food industry. In: Grumezescu AM, Holban AM, editors. Biopolymers for food design. Handbook of food bioengineering: Academic Press, Elsevier; 2018. pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Joulak I, Azabou S, Finore I, Poli A, Nicolaus B, Donato PD, Bkhairia I, Dumas E, Gharsallaoui A, Immirzi B. Structural characterization and functional properties of novel exopolysaccharide from the extremely halotolerant Halomonas elongata S6. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YY, Hwang ST, Sethi G, Fan L, Arfuso F, Ahn KS. Potential anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties of farnesol. Molecules. 2018;23:2827. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavitake D, Balyan S, Devi PB, Shetty PH. Evaluation of oil-in-water (O/W) emulsifying properties of galactan exopolysaccharide from Weissella confusa KR780676. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57:1579–1585. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04262-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielak AM, Castellane TC, Campanharo JC, Colnago LA, Costa OY, Da Silva MLC, Van Veen JA, Lemos EG, Kuramae EE. Characterization of novel Acidobacteria exopolysaccharides with potential industrial and ecological applications. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep41193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HM, Park MK, Yun JW. Culture pH affects exopolysaccharide production in submerged mycelia culture of Ganoderma lucidum. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2006;134:249–262. doi: 10.1385/ABAB:134:3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaswamy UR, Lakshmanaperumalsamy P, Achlesh D. Microbial Exopolysaccharides as Biosurfactants in Environmental and Industrial Applications. In: Maddela NR, García LC, Chakraborty CS, editors. Advances in the Domain of Environmental Biotechnology. Springer; 2021. pp. 81–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AS, Mody K, Jha B. Bacterial exopolysaccharides–a perception. J Basic Microbiol. 2007;47:103–117. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200610203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Kim SH, Park IH, Chung SY, Choi YL. Isolation and structural analysis of bamylocin A, novel lipopeptide from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LP03 having antagonistic and crude oil-emulsifying activity. Arch Microbiol. 2007;188:307–312. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Huang L, Zhang Y, Yan Y. Production, characterization and immunomodulatory activity of an extracellular polysaccharide from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa YL-1 isolated from Sea salt field. Mar Drugs. 2020;18:595. doi: 10.3390/md18120595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yang L, Molin S. Synergistic activities of an efflux pump inhibitor and iron chelators against Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3960–3963. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00463-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes EM, Castellane TCL, Moretto C, Lemos EGM, Souza JAM. Emulsification properties of bioemulsifiers produced by wild-type and mutant Bradyrhizobium elkanii strains. J Bioremed Biodeg. 2014;5:245. [Google Scholar]

- Luna JM, Rufino RD, Sarubbo LA, Campos-Takaki GM. Characterisation, surface properties and biological activity of a biosurfactant produced from industrial waste by Candida sphaerica UCP0995 for application in the petroleum industry. Colloids Surf B. 2013;102:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Chen X, Wang B, Lou W, Chen X, Hua J, Sun Y, Zhao Y, Peng T. Characterization, antioxidativity, and anti-carcinoma activity of exopolysaccharide extract from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa CICC 33013. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;181:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalej H, Hmidet N, Boisset C, Buon L, Heyraud A, Nasri M. Optimization of exopolysaccharide production from Pseudomonas stutzeri AS22 and examination of its metal-binding abilities. J Appl Microbiol. 2015;118:356–367. doi: 10.1111/jam.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhuri KV, Rabhakar KV. Microbial exopolysaccharides: biosynthesis and potential applications. Orient J Chem. 2014;30:1401–1410. doi: 10.13005/ojc/300362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Ramirez CF, Castañeda-Guel MT, Alvarez-Gonzalez M, Montesinos-Castellanos A, Morones-Ramirez JR, López-Guajardo EA, Gómez-Loredo A. Application of extractive fermentation on the recuperation of exopolysaccharide from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa UANL-001L. Fermentation. 2020;6:108. doi: 10.3390/fermentation6040108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei Seveiri R, Hamidi M, Delattre C, Sedighian H, Pierre G, Rahmani B, Darzi S, Brasselet C, Karimitabar F, Razaghpoor A, Amani J. Characterization and prospective applications of the exopolysaccharides produced by Rhodosporidium babjevae. Adv Pharm Bull. 2020;10:254–263. doi: 10.34172/apb.2020.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen P-T, Nguyen T-T, Bui D-C, Hong P-T, Hoang Q-K, Nguyen H-T. Exopolysaccharide production by lactic acid bacteria: the manipulation of environmental stresses for industrial applications. AIMS Microbiol. 2020;6:451–263. doi: 10.3934/microbiol.2020027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwodo U, Green E, Okoh AI. Bacterial exopolysaccharides: functionality and prospects. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:14002–14015. doi: 10.3390/ijms131114002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell K. Ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacers are highly divergent in the phytopathogenic ascomycete Fusarium sambucinum (Gibberella pulicaris) Curr Genet. 1993;22:213–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00351728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh A, Madamwar D. Partial characterization of extracellular polysaccharides from cyanobacteria. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2006;97:1822–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli A, Anzelmo G, Nicolaus B. Bacterial exopolysaccharides from extreme marine habitats: production, characterization and biological activities. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:1779–1802. doi: 10.3390/md8061779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana S, Upadhyay LSB. Microbial exopolysaccharides: synthesis pathways, types and their commercial applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;157:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger MM. Emulsion. In: Lachman L, Lieberman HA, Kanig JL, editors. The theory and practice of industrial pharmacy. 3. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1986. pp. 502–532. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues LR, Teixeira JA, Vander Mei HC, Oliveira R. Physicochemical and functional characterization of a biosurfactant produced by Lactococcus lactis 53. Colloids Surf B. 2006;49:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E, Ron E. Bioemulsans: microbial polymeric emulsifiers. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:313–316. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(97)80009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad MMG, Gouda NAA, Abdelgaleil SAM. Bioherbicidal activity of terpenes and phenylpropenes against Echinochloa crus-galli. J Environ Sci Health B. 2019;54:954–963. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2019.1653121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos DKF, Rufino RD, Luna JM, Santos VA, Salgueiro AA, Sarubbo L. Synthesis and evaluation of biosurfactant produced by Candida lipolytica using animal fat and corn steep liquor. J Pet Sci Eng. 2013;105:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2013.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satpute SK, Banat IM, Dhakephalkar PK, Banpurkar AG, Chopade BA. Biosurfactants, bioemulsifiers and exopolysaccharides from marine microorganisms. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28:436–450. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpute SK, Zinjarde SS, Banat IM (2018) Recent updates on biosurfactant/s in food industry. In: Microbial cell factories. Taylor & Francis, pp 1–20

- Seveiri RM, Hamidi M, Delattre C, Sedighian H, Pierre G, Rahmani B, Darzi S, Brasselet C, Karimitabar F, Razaghpoor A. Characterization and prospective applications of the exopolysaccharides produced by Rhodosporidium babjevae. Adv Pharm Bull. 2020;10:254–263. doi: 10.34172/apb.2020.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng GP, Yu HQ, Yue Z. Factors influencing the production of extracellular polymeric substances by Rhodopseudomonas acidophila. Int Biodeterior Biodegr. 2006;58:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddharth T, Sridhar P, Vinila V, Tyagi R. Environmental applications of microbial extracellular polymeric substance (EPS): a review. J Environ Manag. 2021;287:112307. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silambarasan S, Logeswari P, Cornejo P, Kannan VR. Evaluation of the production of exopolysaccharide by plant growth promoting yeast Rhodotorula sp. strain CAH2 under abiotic stress conditions. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;121:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synytsya A, Novák M. Structural diversity of fungal glucans. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;92:792–809. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari ON, Sasmal S, Kataria AK, Devi I. Application of microbial extracellular carbohydrate polymeric substances in food and allied industries. 3 Biotech. 2020;10:1–17. doi: 10.3390/biotech10010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzoigwe C, Burgess JG, Ennis CJ, Rahman PKSM. Bioemulsifiers are not biosurfactants and require different screening approaches. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:245. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Rodríguez A, Vasto-Anzaldo XG, Leon-Buitimea A, Zarate X, Morones-Ramírez JR. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles coated with exopolysaccharides obtained from Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci. 2020;19:498–503. doi: 10.1109/TNB.2020.2985101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Aradillas C, Toribio-Jiménez J, del Carmen Ángeles González-Chávez M, Bautista F, Cebrián ME, Esparza-García FJ, Rodríguez-Vázquez R. Characterisation of a biosurfactant produced by a Bacillus cereus strain tolerant to cadmium and isolated from green coffee grain. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;27:907–913. doi: 10.1007/s11274-010-0533-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayabaskar P, Babinastarlin S, Shankar T, Sivakumar T, Anandapandian KTK. Quantification and characterization of exopolysaccharides from Bacillus subtilis (MTCC 121) Adv Biol Res. 2011;5:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Shao C, Liu L, Guo X, Xu Y, Lu X. Optimization, partial characterization and antioxidant activity of an exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus plantarum KX041. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;103:1173–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Ma J, Wang X, Wang Z, Tang L, Chen H, Li Z. Detoxification of Cu(II) by the red yeast Rhodotorula mucilaginosa: from extracellular to intracellular. App Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:10181–10190. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10952-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield C, Wear SS, Sande C. Assembly of bacterial capsular polysaccharides and exopolysaccharides. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2020;74:521–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-011420-075607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Zhang J, Yang Y, Zhou S, Liu Y, Tang Q, Du X, Chen H, Pan Y. Structural characterisation of a heteropolysaccharide by NMR spectra. Food Chem. 2009;112:962–966. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M, Liang J, Liao X, Li L, Feng X, Qian W, Zhou S, Sun S. Bioleaching for detoxification of waste flotation tailings: relationship between EPS substances and bioleaching behavior. J Environ Manag. 2021;279:111795. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannini E, Waters DM, Coffey A, Arendt EK. Production, properties, and industrial food application of lactic acid bacteria-derived exopolysaccharides. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:1121–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-7172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, Li F, Wu C, Yu R, Wu X, Shen L, Liu Y, Qiu G, Li J. Role of extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) in toxicity response of soil bacteria Bacillus sp. S3 to multiple heavy metals. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2020;43:153–167. doi: 10.1007/s00449-019-02213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Li Z, Su J, Zhang R, Liu C, Zhao M. Characterization and emulsifying property of a novel bioemulsifier by Aeribacillus pallidus YM-1. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:44–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zikmanis P, Brants K, Kolesovs S, Semjonovs P. Extracellular polysaccharides produced by bacteria of the Leuconostoc genus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;36:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11274-020-02937-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]