Abstract

Extrinsic compression of the subaxial vertebral artery (VA) may cause rotational occlusion syndrome (ROS) and contribute to vertebrobasilar insufficiency potentially leading to symptoms and in severe cases, to posterior circulation strokes. The present literature review aimed to report the main clinical findings, diagnostic work-up, and surgical management of the subaxial VA-ROS, the diagnosis of which can be difficult and is often underestimated. An illustrative case is also presented. A thorough literature search was conducted to retrieve manuscripts that have discussed the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of ROS. Total 41 articles were selected based on the best match and relevance and mainly involved case reports and small cases series. The male/female ratio and average age were 2.6 and 55.6±11 years, respectively. Dizziness, visual disturbances, and syncope were the most frequent symptoms in order of frequency, while C5 and C6 were the most affected levels. Osteophytes were the cause in >46.2% of cases. Dynamic VA catheter-based angiography was the gold standard for diagnosis along with computed tomography angiography. Except in older patients and those with prohibitive comorbidities, anterior decompressive surgery was always performed, mostly with complete recovery, and zero morbidity and mortality. A careful neurological evaluation and dynamic angiographic studies are crucial for the diagnosis of subaxial VA-ROS. Anterior decompression of the VA is the cure of this syndrome in almost all cases.

Keywords: Cerebral angiography, Posterior circulation, Spondylosis, Stroke, Vertebral artery, Vertebrobasilar insufficiency

Introduction

Subaxial vertebral artery (VA) rotational occlusion syndrome (ROS) causes a transient or permanent decrease in blood flow in the posterior cerebral circulation that is associated with the occurrence of dizziness, drop attacks, visual disturbances, sensitive and motor symptoms, and even devastating strokes. These symptoms are classically triggered by the axial rotation of the head within the physiologic range of motion [1].

Disk herniation, spondylosis, ligamentous hypertrophy, bony defects, and abnormalities in the course of the VA across the transverse foramina are the main etiological factors. Atherosclerosis worsens the frequency and severity of the symptoms [2-9]. The treatment of the subaxial VA-ROS is elective surgical that aims to decompress the VA and restore normal blood flow in the posterior circulation [10-15]. Nevertheless, literature about the overall management of this syndrome is limited and mostly consists of case reports or small case series [2,3,6,16-54].

This literature review addresses the clinical aspects, diagnosis, and surgical management of subaxial VA-ROS. An illustrative case is also reported.

Methods

Two separate systematic reviews of the literature were conducted using the Ovid Medline and EMBASE databases to identify articles relevant to the natural history, diagnosis methods, treatment modalities, and outcomes of patients affected by VA-ROS. A population, intervention, comparison, and outcome search strategy was used for each review. Keyword and MeSH search terms were used including “axis, cervical vertebra,” “vertebral artery,” “occlusion syndrome,” “cervical vertebra,” “compression syndrome,” “bow hunter’s syndrome,” “decompression,” “dynamic angiography,” “vertebrobasilar insufficiency,” and “head movements.” All the manuscripts published in English were eligible for inclusion. This search strategy selected articles that described the diagnosis, natural history, and treatment of the VA-ROS. Reference lists of the included manuscripts were studied to identify additional relevant publications. Further articles were included following a manual search of the literature.

Results

1. Literature volume

The search retrieved 77 articles. After applying the exclusion criteria and removing duplicates, 41 relevant articles were selected and have been reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature review of sub-axial vertebral artery rotational occlusion syndrome

| No. | Authors (year) | No. of cases | Average age (yr) | Sex | Risk factors for stroke | Symptoms | Trigger | Neuroimaging techniques | Compression site | Laterality | Etiology and contributing factors | Treatment | Postoperative imaging | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Powers et al. [41] (1961) | 17 | NA | NA | None | Dizziness, visual disturbances, sensitive symptoms | Ext, Rot | dynAG | NA | NA | Muscle band | ASR (AA) | dynAG | Improved |

| 2 | Gortvai [16] (1964) | 1 | 56 | M | HP | Dizziness, syncope, hemiparesis, cervicalgia | E xt, Lt/Rt Rot | XR, dynAG | C6 | Lt | SPL, CST, DH, FR | ATR, OR, (AA) | dynAG | Improvement of hemiparesis |

| 3 | Bakay and Leslie [18] (1965) | 1 | 47 | M | HP, DM | Dizziness, syncope, paresthesia | Lt Rot | XR, dynAG | C5 | Rt | SPL, SPLS | OR, F (AA) | dynAG | Mild dizziness |

| 1 | 42 | M | None | Dizziness, cervicalgia | Ext, Rt Rot | XR, dynAG | C6 | Rt | SPL | ACDF (AA) | dynAG | Complete resolution | ||

| 4 | Hardin [17] (1965) | 9 | 63 | M (6); F (3) | HP (3) | Visual disturbances (7); sensitive/motor symptoms (6); dizziness (5); syncope (4); dysarthria (4); tinnitus (2); ataxia (2) | Rot | dynAG | C2–C6 (1); C5 (3); C6 (4) | NA | SPL | FT (AA) | dynAG | Complete resolution (5); tinnitus, deafness (1); dizziness, paresis (1); hoarseness (1); hemianopsia (1) |

| 5 | Husni [42] (1967) | 23 | 40 | M (13); F (10) | None | Dizziness (23); gait disturbances (12); syncope (6); visual disturbances (6); sensitive symptoms (4) | Rot | dynAG | C6 | Rt (6); Lt (10); bilateral (7) | LC (10); LC+AS (8); AS (4); MS (1) | Decompression (AA) | dynAG | Complete resolution (22); improved (1) |

| 6 | Nagashima [19] (1970) | 20 | 51 | M (12); F (8); | HP (4) | Dizziness (17); visual disturbances (12); syncope (10); cranial nerve palsy (8); sensitive/motor symptoms (8); ataxia (7); nystagmus (3) | Rot | dynAG | C 4 (5); C5 (12); C6 (4) | Rt (9); Lt (6); bilateral (5) | SPL, FR | OR, FT (AA) | XR, dynAG | Complete resolution (12); improved (6); suicide (1); myocardial infarction (1); |

| 7 | Smith et al. [20] (1971) | 1 | 51 | F | None | Syncope, ataxia, headache | Ex | XR, dynAG | C5 | Lt | SPL, CST | D, OR, F (AA) | dynAG | Complete resolution |

| 1 | 53 | M | None | Dizziness, hemifacial hypesthesia, paresis | Ex, Rot | XR, dynAG | C5, C6 | Bilateral | SPL | FT, OR, (AA) | dynAG | Complete resolution | ||

| 8 | Sullivan et al. [21] (1975) | 1 | 37 | M | None | Hemianopsia, headache | Rot | dynAG | C5 | Lt | SPL, FR | OR, F (AA) | dynAG | Improved |

| 9 | Dadsetan and Skerhut [43] (1990) | 1 | 56 | M | None | Dizziness, loss of vision, nystagmus | Rt Rot | CT, DSA | C7 | Lt | Muscle band | ASR, FT (AA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 10 | Budway and Senter [44] (1993) | 1 | 45 | M | HP | Dizziness, visual disturbances | Rot | XR, CT, MRI, dynAG | C5 | Lt | DH | D, ATR (AA) | NA | Complete resolution |

| 11 | Chin [45] (1993) | 1 | 55 | M | None | Dizziness, ataxia, tinnitus | Rot | CT, MRI, dynAG | C4 | Lt | SPL | Decompression | NA | Complete resolution |

| 12 | Kawaguchi et al. [23] (1997) | 1 | 56 | M | None | Amaurosis, tinnitus | Rt Rot | XR, CT, MRI, CTA, dynAG | C5 | Rt | SPL, FR | OR, FT (AA) | dynAG | Horner’s syndrome, weakness |

| 13 | Kuether et al. [46] (1997) | 1 | 49 | M | None | Dizziness, presyncope | Ext, Rt Rot | DSA | C4–C5; C2 | Rt, Lt | Left VA occlusion at C2 site | FT (PA); refused surgery on other side | NA | Not improvement |

| 1 | 62 | M | None | Presyncope | Ext, Rt Rot | DSA | C2 | Lt | SPL | Refused | NA | NA | ||

| 1 | 39 | M | None | Tinnitus, loss of vision | Rt Rot | DSA | C7 | Rt | NA | Conservatively | NA | NA | ||

| 14 | Citow and Macdonald [47] (1999) | 1 | 69 | M | None | Dizziness, dysarthria, tetraparesis, diplopia | Ext, Rt Rot | CT, MRI, DSA | C6 | Lt | SPL, FR | FJR, OR (PA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 15 | Kimura et al. [48] (1999) | 1 | NA | NA | None | Dizziness, presyncope, paresthesia | Rt Rot | XR, MRI, dynAG | C5–C7 | Rt | SPL, SPLS, DH | ACDF | dynAG | Complete resolution |

| 16 | Ogino et al. [49] (2001) | 1 | 66 | M | None | Pre-syncope, dizziness, nystagmus | Rt Rot | MRI, CTA, dynAG | C4 | Rt | SPL, FR | FT, TPR (AA) | dynAG | Complete resolution |

| 17 | Vates et al. [24] (2002) | 1 | 56 | M | None | Dizziness, syncope | Lt Rot | XR, MRI, CT, DSA, DUS | C5 | Rt | DH | D, FT (AA) | CT, DUS, DSA | Complete resolution |

| 18 | Nemecek et al. [25] (2003) | 1 | 61 | M | None | Dizziness, syncope, nausea | Ex, Lt Rot | MRA, CTA, DSA, DUS | C6 | Lt | DH | D, FT (AA) | DUS | Complete resolution |

| 19 | Vilela et al. [26] (2005) | 6 | 58 | NA | HP, HL (1) | Syncope (5); dizziness (3); visual disturbances (3); leg paresis (1); dysarthria (1) | Rt Rot (4); Lt Rot (3) | MRI, DSA, CTA | C4 (3), C5 (2); C6 (3) | Rt (3); Lt (3) | SPL (4); DH (1); SPL, DH (1); | OR (4); D (1); D, OR (1); (AA) | DUS | Complete resolution (4); dizziness (2) |

| 20 | Bulsara et al. [3] (2006) | 1 | 55 | M | HP, DM | Dizziness, syncope | Rt Rot | CT, MRI, CTA, DSA | C5 | Rt | SPL, FR | OR, D, FT (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 21 | Velat et al. [50] (2006) | 1 | 58 | M | None | Dizziness, presyncope | Lt Rot | DSA | C6 | Lt | SPL | OR (AA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 22 | Miele et al. [51] (2008) | 1 | 48 | M | None | Syncope | Lt Rot | CT, MRI, DSA | C5 | Lt | SPL | ACDF | NA | Complete resolution |

| 23 | Tsutsumi et a [27] (2008) | 1 | 59 | M | HP, HL | Presyncope | Lt Rot | XR, MRI, CT, DSA | C5, C6 | Bilateral | SPL, SPLS, FR | FT, ACDF (AA) | XR, DSA | Complete resolution |

| 24 | Ujifuku et al. [2] (2009) | 1 | 78 | M | None | Syncope, visual disturbances | Rt Rot | MRI, CTA, DSA | C4 | Rt | DH | ATR, D (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 25 | Lu et al. [28] (2010) | 4 | 66.5 | M (4) | None | Dizziness, syncope | Rot | DSA, CTA | C4 (1); C5 (2); C6 (1) | Rt (1); Lt (3) | DH (1); SPL (1); SPL, FR (1); | FT, D (AA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 26 | Lee et al. [5] (2011) | 1 | 50 | M | None | Dizziness, syncope | Rt, Lt Rot | CT, MRA, DSA | C7 | Lt | Bony abnormality | Bony spurs removal (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 1 | 28 | F | None | Dizziness, ataxia, loss of vision | Ext, Rt Rot | DSA | C7 | Rt | Bony abnormality | ATR (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution | ||

| 27 | Yoshimura et al. [29] (2011) | 1 | 64 | M | HP, HL | Dizziness, syncope | Rt Rot | XR, MRI, DSA, CTA | C3 | Rt | SPL, UVI | ACDF (AA) | XR, DSA | Complete resolution |

| 28 | Dargon et al. [52] (2013) | 1 | 53 | M | None | Presyncope, photopsia | Rt Rot | DUS, DSA | C5 | Rt | Transverse process abnormality | TPR (AA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 29 | Fleming et al. [31] (2013) | 1 | 54 | M | None | Dizziness, diplopia, tinnitus | Rt/Lt Rot | MRI, DSA, CTA | C4 | Bilateral | SPL | ACDF (AA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 30 | Pinol et al. [30] (2013) | 1 | 27 | M | None | Dizziness | Rt Rot | XR, DSA, MRA | C6 | Rt | SPL, SPLS | ACDF (AA) | XR, DSA | Complete resolution |

| 31 | Buchanan et al. [32] (2014) | 1 | 52 | M | None | Weakness | Lt Rot | XR, DUS, CTA, DSA | C4 | Lt | SPL | ACDF (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 32 | Jost and Dailey [35] (2015) | 1 | 55 | M | None | Syncope, visual disturbances | Ex, Lt Rot | MRI, MRA, DSA, CTA | C6 | Lt | DH, SPL | ACDF (AA) | NA | Improved |

| 1 | 47 | F | None | Dizziness, visual disturbances | Lt Rot | MRI, MRA, DSA, CTA | C4, C5 | Lt | DH, SPL | ACDF (AA) | NA | Neck pain, stiffness | ||

| 33 | Okawa et al. [34] (2015) | 1 | 31 | F | DM | Dysarthria, confusion | Rt Rot | MRI, MRA, DSA, CTA | C5 | Rt | DH | D, FT (AA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 34 | Haimoto et al. [53] (2017) | 1 | 71 | M | None | Dizziness, syncope | Ext, Rt Rot | XR, CTA, DSA | C5 | Lt | SPL, DH, Osteochondroma | Tumor removal, TPR (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 35 | Johnson et al. [6] (2017) | 1 | 42 | M | None | Hemiparesis, hemianopsia | Rt Rot | MRI, DSA, CTA | C5 | Rt | Abnormal VA course | ATR (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 36 | Nishikawa et al. [36] (2017) | 1 | 78 | F | None | Dizziness, visual disturbances | Ex, Rt Rot | MRI, MRA, DSA, CTA | C5 | Rt | SPL | ATR, OR (AL) | CTA, DSA | Complete resolution |

| 1 | 77 | M | DM | Dizziness, dysarthria | Rt/Lt Rot | MRI, MRA, DSA, CTA | C5 | Bilateral | SPL | ACDF (AA) | CTA, MRA | Complete resolution | ||

| 37 | Cornelius et al. [38] (2018) | 1 | 54 | M | None | Syncope, visual disturbances | Lt Rot | MRI, MRA, CT, CTA, DSA | C6 | Lt | SPL | FT (AL) | NA | Complete resolution |

| 38 | Iida et al. [37] (2018) | 1 | 65 | M | None | Dizziness, visual disturbances | Lt Rot | MRI, MRA, DSA, CTA | C3 | Lt | SPL | OR, F (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 39 | Ng et al. [40] (2018) | 1 | 70 | M | None | Dizziness, syncope | Lt Rot | DSA, CTA | C4 | Bilateral | SPL | ACDF (AA) | DUS, CTA | Complete resolution |

| 40 | Rendon et al. [54] (2018) | 1 | 76 | F | HP, DM, HL | Presyncope | Rt Rot | CTA | C5 | Rt | Thyroid cartilage | Decompression (AA) | CTA | Complete resolution |

| 41 | Schunemann et al. [39] (2018) | 1 | 60 | M | HP | Dizziness, syncope | Lt Rot | XR, MRI, CTA, DSA | C3 | Rt | NA | ACDF (AA) | DSA | Complete resolution |

| 42 | Present case (2020) | 1 | 74 | M | HP | Dizziness, ataxia, visual disturbances, VII cranial nerve palsy | Lt Rot | XR, MRI, CT, CTA, DSA | C6 | Lt | SPL, FR | ATR, OR (AL) | CTA | Complete resolution |

NA, not available; Ext, extension; Rot, rotation; DynAG, dynamic angiography; ASR, anterior scalene resection; AA, anterior approach; M, male; F, female; HP, hypertension; Lt, left; Rt, right; XR, X-ray; SPL, spondylosis; CST, cervical spine trauma; DH, disc herniation; FR, fibrous ring; ATR, anterior tubercle removal; OR, osteophyte removal; DM, diabetes mellitus; SPLS, spondylolisthesis; F, fusion; ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; FT, foraminotomy; LC, longus colli muscle; AS, anterior scalene muscle; MS, medium scalene muscle; D, discectomy; CT, computed tomography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CTA, computed tomography angiography; VA, vertebral artery; PA, posterior approach; FJR, facet joint removal; PTR, posterior tubercle removal; DUS, Doppler ultrasonography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; HL, hyperlipidemia; UVI, uncovertebral instability; AL, anterolateral approach.

2. Demographic and clinical data

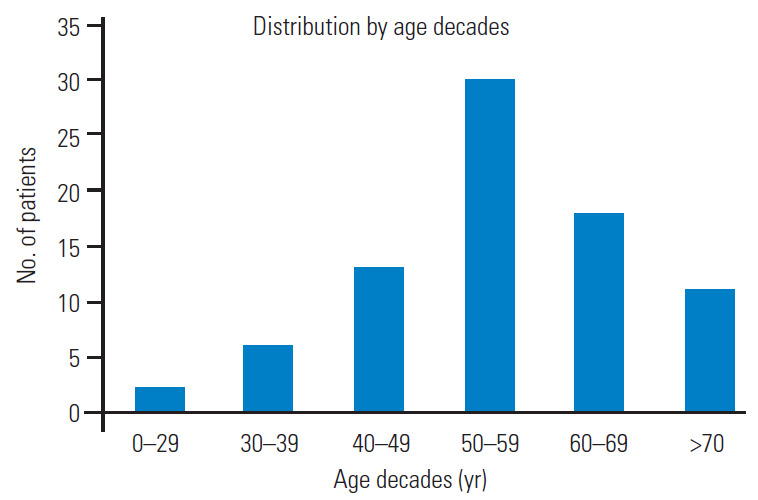

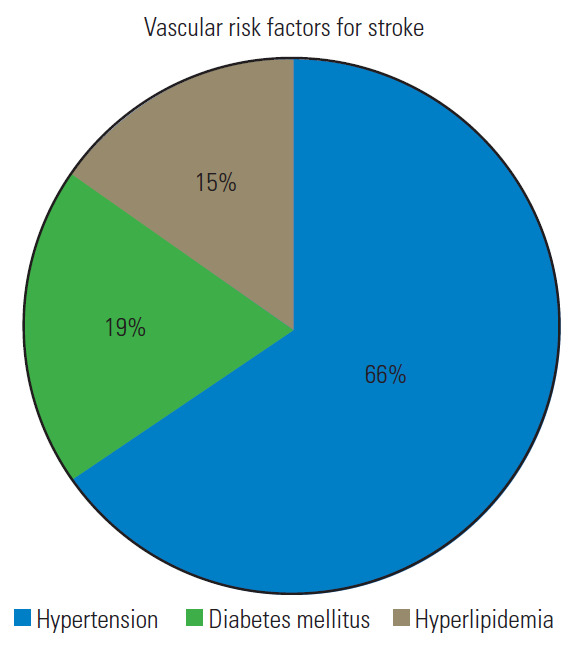

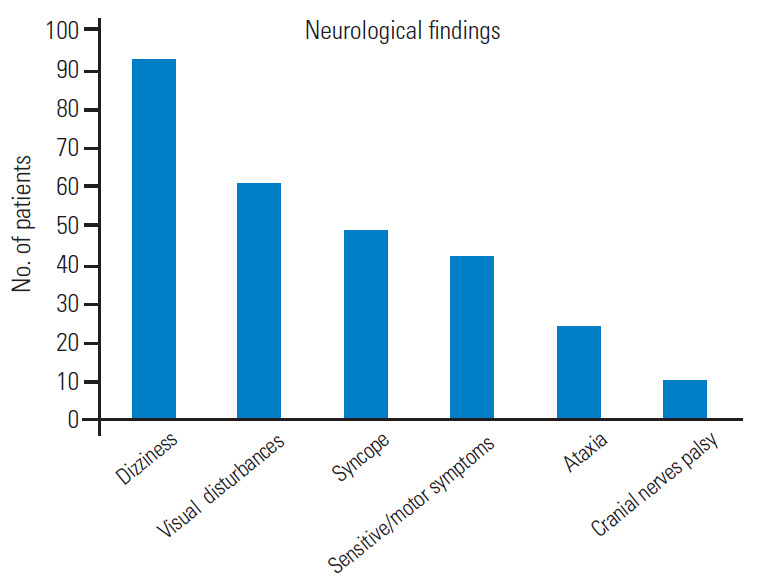

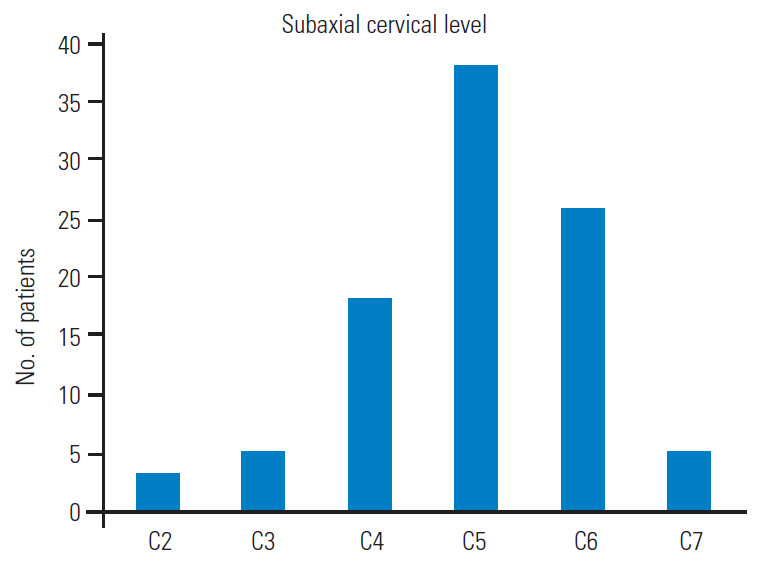

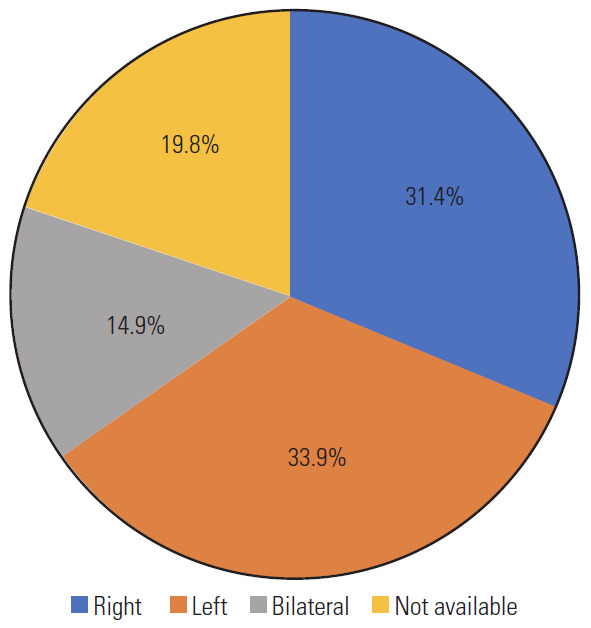

Total 121 patients were included in the study. The male/female ratio was 2.6 although sex was not reported in 24 patients. The average patient age was 55.6±11 years, and those in the fifth decade were more affected. Graph 1 shows the distribution by age decades (Fig. 1). In cases with vascular risk factors for stroke, the average frequency of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia were 66%, 19%, and 15%, respectively (Fig. 2). Dizziness, visual disturbances, and syncope had a prevalence rate of 76.8%, 50.4%, and 40.4%, respectively (Fig. 3). The C5 level was the most affected (31.4%) followed by the C6 level (21.4%) (Fig. 4). Left side had prevalence (33.9% versus 31.4%) and in 14.9% of the cases, the cause of occlusion involved both the sides (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

Bar graph showing the distribution by age decades.

Fig. 2.

Pie graph reporting the prevalence of the main vascular risk factors for stroke.

Fig. 3.

Bar graph showing the main neurological findings.

Fig. 4.

Bar graph describing the rate of the involvement of the different subaxial cervical levels.

Fig. 5.

Pie graph about the sideness.

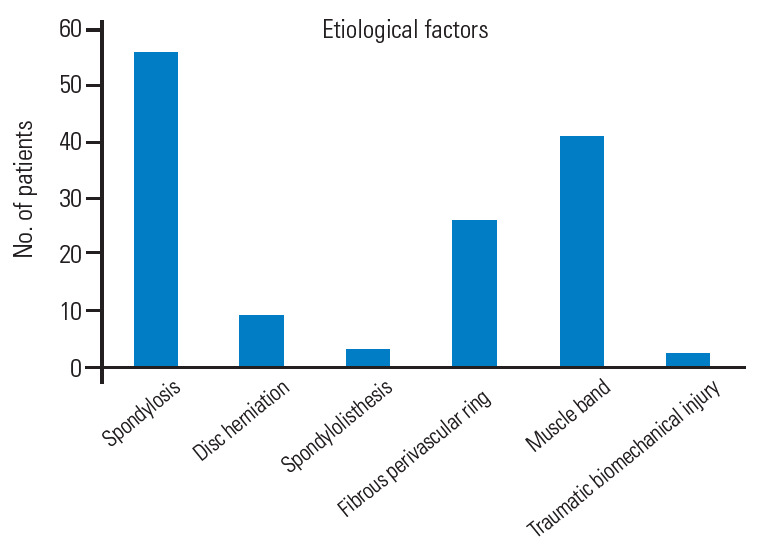

3. Etiological factors

Cervical spondylosis was the most common causative factor (46.2%), followed by muscle band (33.8%), fibrous perivascular ring (21.4%), and disk herniations (7.4%). Less common reasons were degenerative spondylolisthesis (2.4%) and biomechanical traumatic instability (1.6%) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Bar graph showing the prevalence of the different etiological factors.

4. Diagnostic work-up

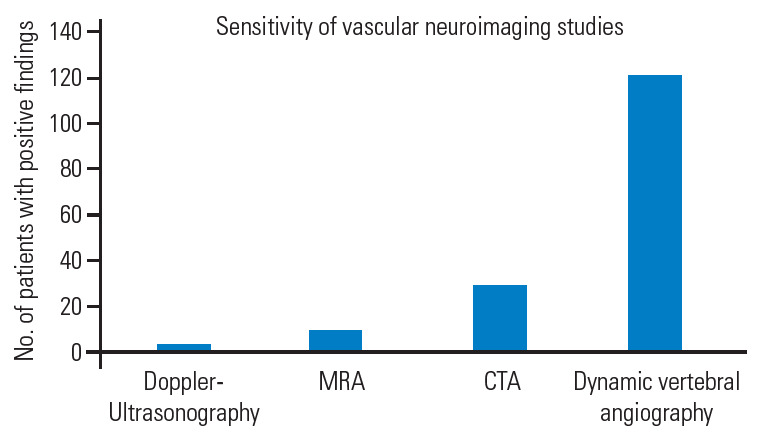

Diagnostic work-up involves different neurovascular imaging techniques whose sensitivity widely varies by type. Dynamic VA angiography, initially non-subtracted and then subtracted (digital subtraction angiography, DSA), has been crucial in the diagnosis in 100% of the reported cases. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance angiography were performed in 24.7% and 8.2% of the cases, respectively. Doppler ultrasound (DUS) standalone allowed the diagnosis in only four cases (3.3%) [24-26,32] (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Bar graph reporting the sensitivity of the vascular neuroimaging techniques. MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; CTA, computed tomography angiography.

5. Indication for surgery

Considering the neuroimaging evidence of VA-ROS, the indication for surgery was based in all cases on the severity of the symptoms, negative impact on the performance of normal daily and working activities, and failure of conservative therapies. Conversely, conservative treatment in collar brace that also involved the establishment of an antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, to be decided case-bycase based on the coexistence of vascular risk factors for stroke, may have a rationale in elderly patients with minor symptoms.

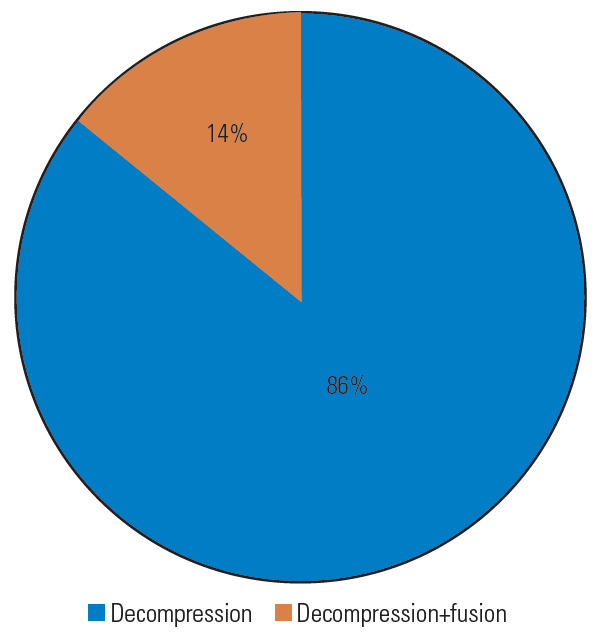

6. Choice of the approach and surgical corridors

In all cases, anterior decompression of the VA was performed, accompanied by fusion in 16% of the cases (Fig. 8). An anterior Smith–Robinson (Baley–Cloward) approach was used in all cases with the exception of the series by George and Bruneau, where an anterolateral presternocleidomastoid retro-jugular route was reported [11,55-59].

Fig. 8.

Pie graph about the type of surgical treatment.

7. Complications

No complications attributable to the surgical treatment have been reported, except in a case where the occurrence of Horner’s syndrome suggested injury to the sympathetic chain [23].

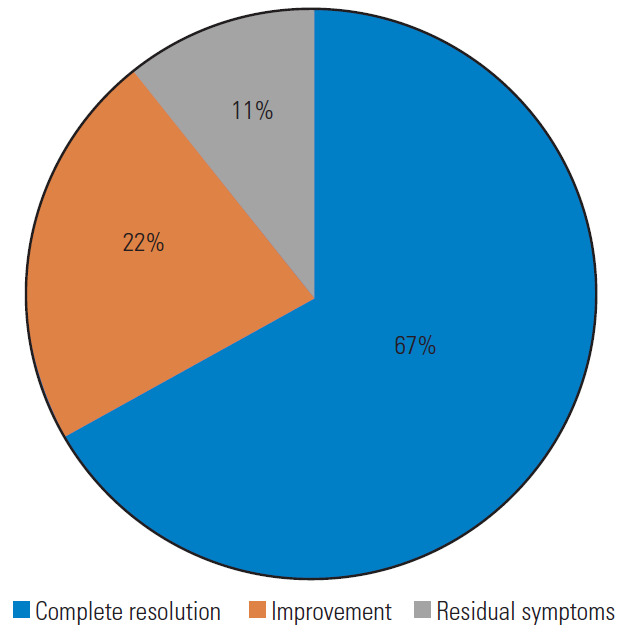

8. Overall outcome

In 67% of the cases, the pre-operative symptoms disappeared immediately after surgery, and vascular neuroimaging revealed a full release of the VA with no residual signs of extrinsic compression. Further, 22% of the patients showed significant clinical improvement, while 11% reported only partial neurological amelioration with residual symptoms (Fig. 9). No specific scales were used for this evaluation.

Fig. 9.

Pie graph reporting the overall outcome.

9. Illustrative case

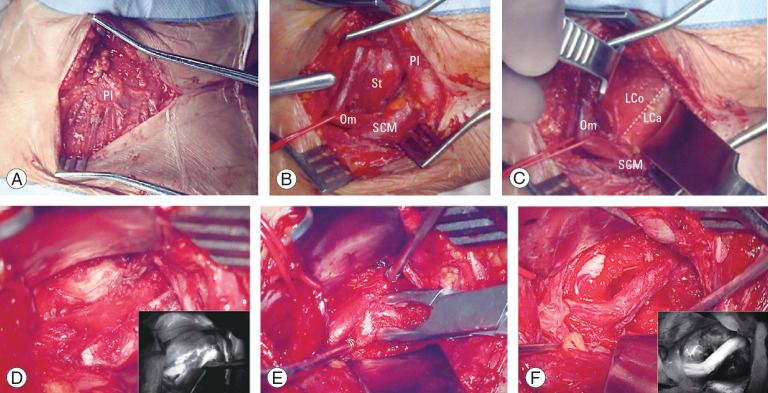

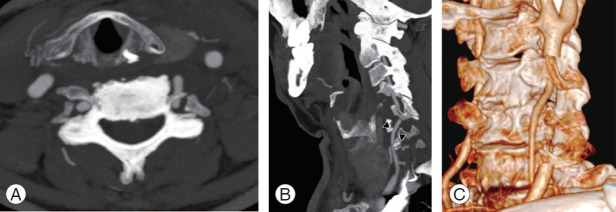

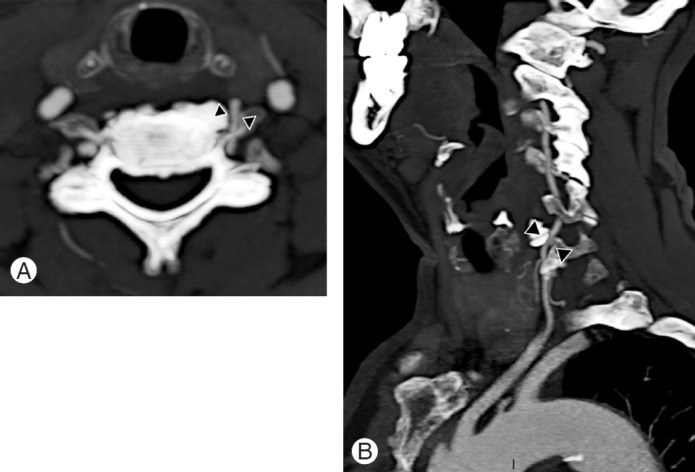

A 74-year-old male patient with medical history of hypertension experienced seven consecutive drop attacks in duration of 14 months. Cardiovascular investigations, blood tests for thrombophilia, and DUS were all within normal limits. The last attack was in association with left facial nerve palsy, rotatory nystagmus, dizziness, and numbness in the right arm. The CT and magnetic resonance imaging findings were normal; therefore, a transitory ischemic attack was suspected, and the patients underwent systemic thrombolysis, followed by anticoagulation with a factor Xa inhibitor, rivaroxaban. As the drop attacks manifested again in the 3 months after initiating anticoagulation therapy, the patients came to our attention. A comprehensive neurological examination revealed an association between the right axial rotation of the head >45° and early appearance of nausea, blurred vision, and dizziness. CT angiography revealed dynamic tethering of the VA at C5–C6 during right axial rotation of the head caused by a C6 osteophyte of the left uncinate process narrowing the anterior ramus of the satellite transverse foramen (Fig. 10). Catheter-based dynamic angiography confirmed these findings (Fig. 11). The patient underwent selective unroofing of the left C6 transverse foramen trough an anterolateral approach. The retro-longus colli corridor allowed easy reach and exposure of the subaxial portion of the V2 segment of the VA (Fig. 12). Postoperative static and dynamic CT and catheter-based angiography confirmed complete release of the VA (Fig. 13). The drop attacks subsided. Anticoagulant therapy was maintained for 1 month postoperatively and then discontinued.

Fig. 10.

Axial (A) and sagittal (B) contrast enhanced CT angiography showing a left C5–C6 margin-somatic osteophyte narrowing the near transverse foramen and causing a severe compression of the vertebral artery (arrowheads).

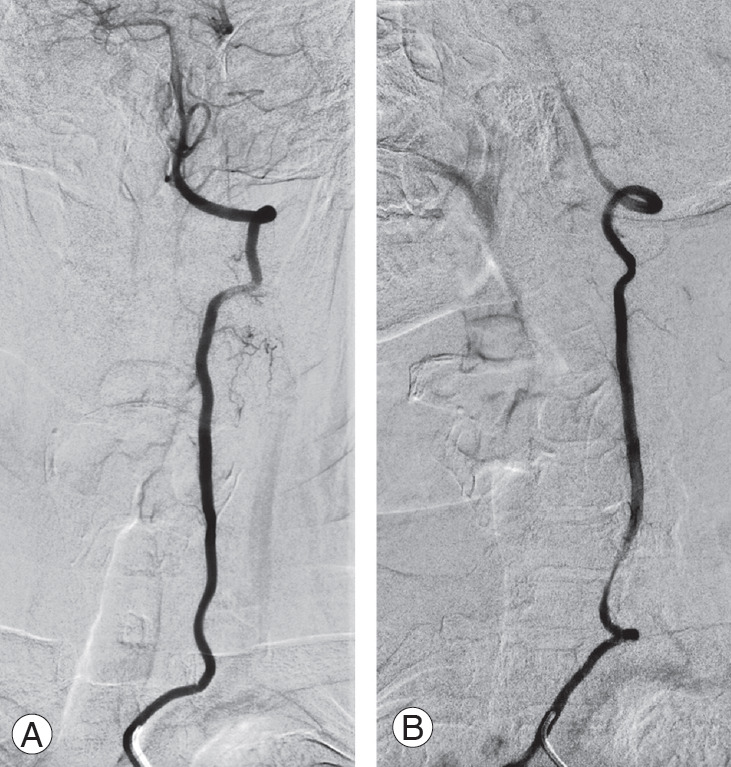

Fig. 11.

Catheter-based digital subtraction angiography of the left vertebral artery. Static anterior-posterior projection (A) and dynamic right oblique projection (B) acquired during the right axial rotation of the head, and revealing a tethering of the vertebral artery at C6 level.

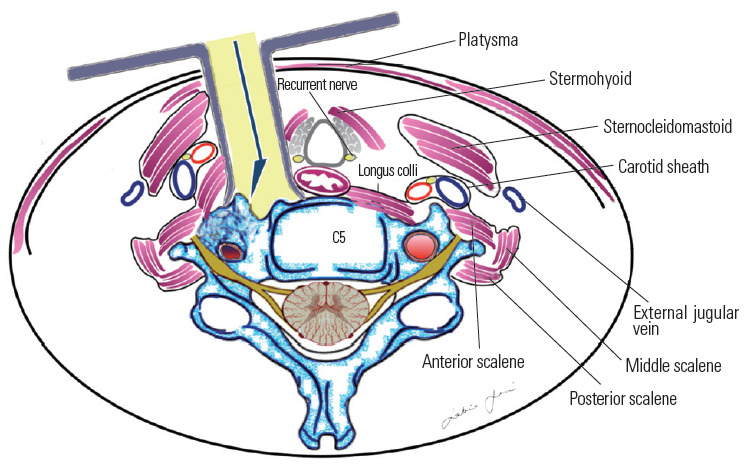

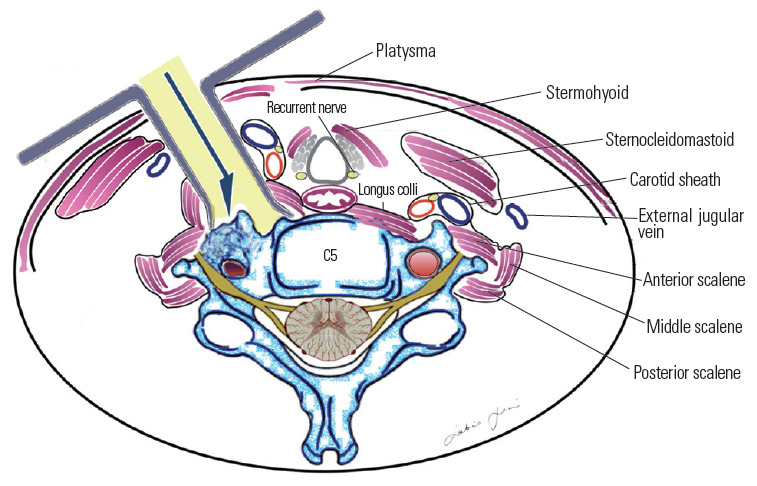

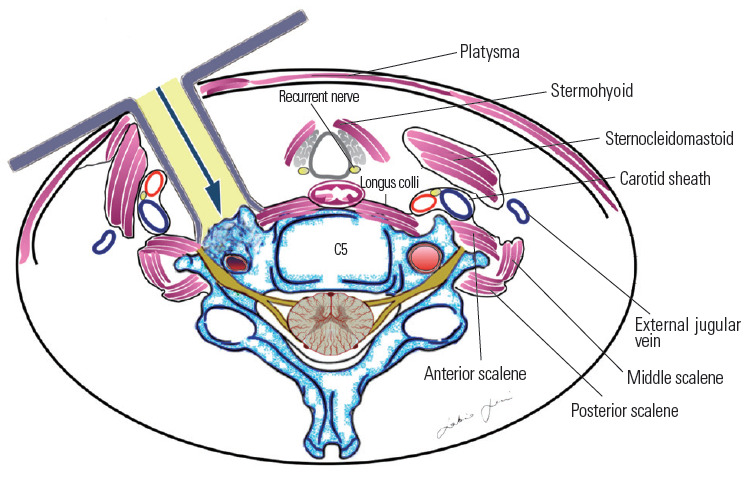

Fig. 12.

Main surgical steps of the left anterolateral approach to the sub-axial V2 segment of the vertebral artery. (A) Platysma muscle; (B) pre-sternocleidomastoid precarotid corridor with medialization of the omohyoid muscle; (C) identification of the retro-longus colli corridor; (D) picture-in-picture operative image showing the compression of the vertebral artery by osteophyte and the indocyanine green video angiography (IR 800, Zeiss Kinevo 900; Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany); (E) unroofing of the left C6 transverse foramen. (F) Picture-in-picture operative picture and video angiography showing the vertebral artery completely decompressed. Pl, platysma muscle; St, sternothyroid muscle; Om, omohyoid muscle; SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle; LCo, longus colli muscle; LCa, longus capitis muscle.

Fig. 13.

Postoperative axial (A), sagittal (B) (arrowheads), and dynamic three-dimensional–rendered (C) computed tomography angiography of the vertebral artery revealing its complete release.

Discussion

The present comprehensive literature review about the management of the subaxial VA-ROS showed that most of the publications were case reports or small cases series. Dynamic angiography is the gold standard for this challenging diagnosis, and decompressive surgery performed via the anterior or anterolateral access route can be curative.

Based on a literature review, the biggest challenge concerning VA-ROS is the delay in diagnosis owing to the dynamic and intermittent nature of artery compression, thus often mimicking cardiovascular or other neurovascular pathologies. The transient symptomatology is caused by the axial rotation of the head during a careful neurologic evaluation. George et al. [60] reported that, paradoxically, chronic, static, and concentric causes of compressions, as those secondary to tumors abutting and slowly compressing the VA, are better tolerated because collateral muscular vascular supply develops to vicariate even occlusions of the dominant VA. From the clinical standpoint, compressions of the V2 segment are generally better tolerated than those of V1 and V3 owing to the protective role played by the transverse processes. V1 is susceptible to compressions by fibrous bands and muscle fibers [13,22,60], while V3 is the most commonly affected segment as pathology at the CV junction and C1–C2 is far more common [60].

In an extensive literature review on the pathophysiology and diagnosis of vertebrobasilar insufficiency, Lima Neto et al. [61] reported that this syndrome is more commonly observed in men after the fourth decade of life. Similar data have been reported by Savitz and Caplan [1].

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency is linked with three different mechanisms, including blood flow drop, embolic events, and autoregulation loss [3,60,62]. In particular, for the VA-ROS involving V2 in the subaxial cervical spine, osteophytes are the most common cause, and the embolization from thrombotic material secondary to a chronic sub adventitial mechanical stress seems responsible for the ischemic events [60].

Atherosclerosis is the most important coexisting condition favoring this syndrome; smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and obesity are considered risk factors [61]. Not surprisingly, atrial fibrillation, infective endocarditis, and systemic hypercoagulable state further increase the stroke risk in VA-ROS patients.

Hence, the rationale of antiplatelet/anticoagulant regimen in those patients that not surgical candidates. Machaly et al. [63] demonstrated that vertigo is significantly more common in patients with severe forms of cervical spondylosis, while Olszewski et al. [64] documented a reduction in blood flow in the basilar artery and VAs that could be attributed to the extrinsic compression caused by osteophytes. Bulsara et al. [3] clarified that uncovertebral joint osteophytes cause symptoms during axial rotation and extension of the head, respectively.

Regarding those forms sustained by muscle and fibrous perivascular bands, male and younger patients are at a higher risk, with any probability because of the frequent muscular hypertonia.

Our data highlighted a major involvement of the C5 and C6 levels, similarly to that reported by Nagashima [19]. This subgroup of patients involved mostly men, and risk factors for atherosclerosis were present in all cases, thus confirming the aforementioned theory.

Labyrinthic symptoms associated with vertebrobasilar insufficiency are reported to be mainly caused by the lack of collateral vascular supply of the labyrinthine branches that are tiny and terminal in case of impairment of the vertebrobasilar arterial system [1,61,65]. Moubayed and Saliba [66] also postulated a possible direct ischemia of the labyrinth, secondary to peripheral hypoperfusion or ischemia.

The sensitivity of different neurovascular imaging techniques in the diagnosis of the subaxial VA-ROS warrants discussion. Although simple, non-invasive, repeatable and cost-effective, DUS had the worse sensitivity in our study. However, although it had a sensitivity lower than that of catheter-based angiography, dynamic CT angiography allows direct visualization of the bony compression on the VA, as well as its postoperative release. With a sensitivity and a specificity of 100%, dynamic DSA remains the gold standard for the radiological diagnosis of the subaxial VAROS, allowing detailed appreciation of compression, but also giving information about vascular dominancy of one of the VAs, size of the posterior communicating arteries, anatomical variations of the VA at its termination in the posterior-inferior cerebellar artery, and existence of collaterals. With respect to the sensitivity and specificity of dynamic DSA, our data are consistent with those reported in the literature. It is noteworthy that Toole and Tucker [67] reported that in case of VAs that are different in size, the ischemic event may be attributable to the compression of the non-dominant VA after head rotation to the contralateral side. Selective catheterization of the VAs is obviously of utmost importance to confirm the diagnosis and for surgical planning.

Stand-alone surgical decompression, achieved with selective unroofing of the V2 segment of the VA at the transverse foramen, can be curative for subaxial VA-ROS of the V2 segment, if dynamic compression is demonstrated. In fact, our review demonstrated that the cumulative rate of complete recovery/improvement of symptoms is 89%. For the remaining 11% of the patients with residual symptoms, we conducted an additional different decompressive technique for the removal of the so-called “fibrous band” if further impingement was noted at the V1 segment proximal to the artery entering the foramen at C6 [60].

The addition of a posterior instrumented fusion is seldom necessary and is necessary only if instability is noted or the compression is due to other causes, such as a disc herniation or spondylolisthesis [11,24,25,34,44,48].

Most authors recommend simple lateral extension of the classic Smith–Robinson (Bailey–Cloward) technique [68-70] as suitable to expose the prevertebral musculature and VA [13,14]. This represents a routinely performed operation with which most neurosurgeons are familiar. The approach entails subperiosteal dissection of the longus colli muscle and the exposure of the anterior tubercle of the transverse foramen (Fig. 14). This approach is considered an anterior access route. An anterolateral approach was instead popularized by Bruneau et al. [10-12,57] to obtain an easier and more direct access to the subaxial V2 segment of the VA. The anterolateral approach involves a pre-sternocleidomastoid retro-jugular exposure of the prevertebral area along with the transection of the longus colli muscle (Fig. 15). As we report here in this illustrative case, we prefer the anterolateral approach for decompression of the subaxial VA with some modifications, including the precarotid exposure of the prevertebral muscles. The rationale of the precarotid exposure lies in the fact that injuries of the thoracic duct are very uncommon through this route because it has a more lateral course at the C4–C6 level [10,71-77] (Fig. 16).

Fig. 14.

Precarotid pre-longus colli corridor.

Fig. 15.

Retro-jugular trans-longus colli corridor.

Fig. 16.

Retro-longus colli corridor.

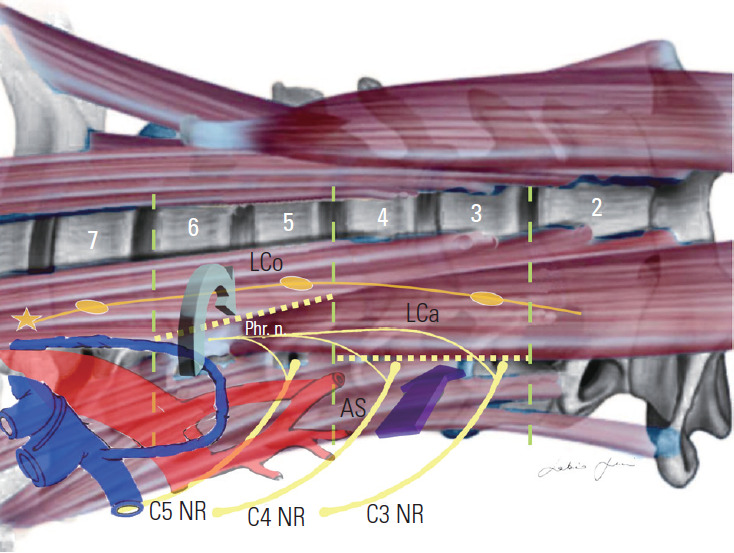

Our personal experience also led us to delineated a retro-longus colli and a pre-scalenic prevertebral corridor for C5–C6 and C3–C4 level, respectively, to avoid injuries of the sympathetic chain and phrenic nerve, here having an upward and lateral-ward course [78-80] (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17.

Retro-longus colli (green arrow) and pre-scalenic (purple arrow) paramuscular corridor. Lco, longus colli muscle; Lca, longus capitis muscle; AS, anterior scalene muscle; Phr. n., phrenic nerve: NR, nerve root.

Having the same advantages already reported by our group for aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations, intraoperative indocyanine green video angiography and microdoppler ultrasonography are also useful adjuncts [81-88].

Conclusions

Subaxial VA-ROS classically causes drop attacks, dizziness, and visual disturbances triggered by axial rotation or head extension. A careful neurological evaluation is paramount to suspect the syndrome. Compressions of the V2 segment of the VA are caused in most cases by osteophytes that involve the uncoapophyseal joints at the C5 and C6 level. Compressions of the V1 segment of the artery relate to the presence of fibrous bands and muscular compression. Dynamic compressions of the VA by tumors are less common.

Dynamic DSA is the gold standard for establishing a diagnosis although dynamic CT angiography is the first step to delineate the extrinsic causes of compression. Anterior decompression of the subaxial VA affected segment is curative in most cases.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Eng. Giorgia Di Giusto for her outstanding and valuable support in formatting the manuscript and editing the graphs and figures.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing–original draft preparation: Sabino Luzzi, Cristian Gragnaniello; soft ware and valida-software and validation: Stefano Marasco, Alice Giotta Lucifero; review and editing: Mattia Del Maestro; validation: Giuseppe Bellantoni; and supervision: Renato Galzio.

References

- 1.Savitz SI, Caplan LR. Vertebrobasilar disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2618–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ujifuku K, Hayashi K, Tsunoda K, et al. Positional vertebral artery compression and vertebrobasilar insufficiency due to a herniated cervical disc. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:326–9. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.SPINE08689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulsara KR, Velez DA, Villavicencio A. Rotational vertebral artery insufficiency resulting from cervical spondylosis: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:625–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar J, Wolfe SQ, Ching BH, Kellicut DC. Bow hunter’s syndrome causing vertebrobasilar insufficiency in a young man with neck muscle hypertrophy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:1032. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2013.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee V, Riles TS, Stableford J, Berguer R. Two case presentations and surgical management of bow hunter’s syndrome associated with bony abnormalities of the C7 vertebra. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1381–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.11.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson SA, Ducruet AF, Bellotte JB, Romero CE, Friedlander RM. Rotational vertebral artery dissection secondary to anomalous entrance into transverse foramen. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:998. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparaco M, Ciolli L, Zini A. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke-a review part I: anatomy, aetiology and clinical presentations. Neurol Sci. 2019;40:1995–2006. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03977-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morimoto T, Nakase H, Sakaki T, Matsuyama T. Extrinsic compression bow hunter’s stroke. In: Bruneau M, Spetzler RF, George B, editors. Pathology and surgery around the vertebral artery. Paris: Springer; 2011. pp. 473–87. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen BF. Bow hunter’s stroke. Neurosurgery. 1978;2:259–61. doi: 10.1227/00006123-197805000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruneau M, Cornelius JF, George B. Anterolateral approach to the V1 segment of the vertebral artery. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(4 Suppl 2):ONS–215. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000204650.35289.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruneau M, Cornelius JF, George B. Anterolateral approach to the V2 segment of the vertebral artery. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(4 Suppl):262–7. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000176414.58086.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruneau M, George B. The lateral approach to the V1 segment of the vertebral artery. In: Bruneau M, Spetzler RF, George B, editors. Pathology and surgery around the vertebral artery. Paris: Springer; 2011. pp. 125–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Z aidi HA, Albuquerque FC, Chowdhr y SA, Zabramski JM, Ducruet AF, Spetzler RF. Diagnosis and management of bow hunter’s syndrome: 15-year experience at barrow neurological institute. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:733–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakuba A. Trans-unco-discal approach: a combined anterior and lateral approach to cervical discs. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:284–91. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.45.3.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verbiest H. A lateral approach to the cervical spine: technique and indications. J Neurosurg. 1968;28:191–203. doi: 10.3171/jns.1968.28.3.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gortvai P. Insufficiency of vertebral artery treated by decompression of its cervical part. Br Med J. 1964;2:233–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5403.214-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardin CA. Vertebral artery insufficiency produced by cervical osteoarthritic spurs. Arch Surg. 1965;90:629–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1965.01320100173025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakay L, Leslie EV. Surgical treatment of vertebral artery insufficiency caused by cervical spondylosis. J Neurosurg. 1965;23:596–602. doi: 10.3171/jns.1965.23.6.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagashima C. Surgical treatment of vertebral artery insufficiency caused by cervical spondylosis. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:512–21. doi: 10.3171/jns.1970.32.5.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith DR, Vanderark GD, Kempe LG. Cervical spondylosis causing vertebrobasilar insufficiency: a surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1971;34:388–92. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.34.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan HG, Harbison JW, Vines FS, Becker D. Embolic posterior cerebral artery occlusion secondary to spondylitic vertebral artery compression: case report. J Neurosurg. 1975;43:618–22. doi: 10.3171/jns.1975.43.5.0618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mapstone T, Spetzler RF. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency secondary to vertebral artery occlusion froma fibrous band: case report. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:581–3. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.56.4.0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawaguchi T, Fujita S, Hosoda K, Shibata Y, Iwakura M, Tamaki N. Rotational occlusion of the vertebral artery caused by transverse process hyperrotation and unilateral apophyseal joint subluxation: case report. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:1031–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.6.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vates GE, Wang KC, Bonovich D, Dowd CF, Lawton MT. Bow hunter stroke caused by cervical disc herniation: case report. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(1 Suppl):90–3. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.96.1.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemecek AN, Newell DW, Goodkin R. Transient rotational compression of the vertebral artery caused by herniated cervical disc: case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(1 Suppl):80–3. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.98.1.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilela MD, Goodkin R, Lundin DA, Newell DW. Rotational vertebrobasilar ischemia: hemodynamic assessment and surgical treatment. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:36–45. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000146441.93026.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsutsumi S, Ito M, Yasumoto Y. Simultaneous bilateral vertebral artery occlusion in the lower cervical spine manifesting as bow hunter’s syndrome. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2008;48:90–4. doi: 10.2176/nmc.48.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu DC, Zador Z, Mummaneni PV, Lawton MT. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion-series of 9 cases. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:1066–72. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ee36db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshimura K, Iwatsuki K, Ishihara M, Onishi Y, Umegaki M, Yoshimine T. Bow hunter’s stroke due to instability at the uncovertebral C3/4 joint. Eur Spine J. 2011;20 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S266–70. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1669-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinol I, Ramirez M, Salo G, Ros AM, Blanch AL. Symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis secondary to cervical spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:E1503–5. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a43441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleming JB, Vora TK, Harrigan MR. Rare case of bilateral vertebral artery stenosis caused by C4-5 spondylotic changes manifesting with bilateral bow hunter’s syndrome. World Neurosurg. 2013;79:799. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchanan CC, McLaughlin N, Lu DC, Martin NA. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion secondary to adjacent-level degeneration following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20:714–21. doi: 10.3171/2014.3.SPINE13452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Healy AT, Lee BS, Walsh K, Bain MD, Krishnaney AA. Bow hunter’s syndrome secondary to bilateral dynamic vertebral artery compression. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okawa M, Amamoto T, Abe H, Yoshimura S, Higashi T, Inoue T. Wake-up stroke in a young woman with rotational vertebral artery occlusion due to farlateral cervical disc herniation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23:166–9. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.SPINE14393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jost GF, Dailey AT. Bow hunter’s syndrome revisited: 2 new cases and literature review of 124 cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38:E7. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.FOCUS14791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishikawa H, Miya F, Kitano Y, Mori G, Shimizu S, Suzuki H. Positional occlusion of vertebral artery due to cervical spondylosis as rare cause of wakeup stroke: report of two cases. World Neurosurg. 2017;98:877. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iida Y, Murata H, Johkura K, Higashida T, Tanaka T, Tateishi K. Bow hunter’s syndrome by nondominant vertebral artery compression: a case report, literature review, and significance of downbeat nystagmus as the diagnostic clue. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.12.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornelius JF, Slotty PJ, Tortora A, Petridis AK, Steiger HJ, George B. Bow hunter’s syndrome caused by compression of the subaxial vertebral artery: surgical technique of anterolateral decompression (video) World Neurosurg. 2018;119:358–61. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.08.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schunemann V, Kim J, Dornbos D, 3rd, Nimjee SM. C2-C3 anterior cervical arthrodesis in the treatment of bow hunter’s syndrome: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:284–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng S, Boetto J, Favier V, Thouvenot E, Costalat V, Lonjon N. Bow hunter’s syndrome: surgical vertebral artery decompression guided by dynamic intraoperative angiography. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:290–5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powers SR, Jr, Drislane TM, Nevins S. Intermittent vertebral artery compression; a new syndrome. Surgery. 1961;49:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Husni EA. Mechanical occlusion of the vertebral artery. GP. 1967;35:94–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dadsetan MR, Skerhut HE. Rotational vertebrobasilar insufficiency secondary to vertebral artery occlusion from fibrous band of the longus coli muscle. Neuroradiology. 1990;32:514–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02426468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Budway RJ, Senter HJ. Cervical disc rupture causing vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:745–7. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199310000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chin JH. Recurrent stroke caused by spondylotic compression of the vertebral artery. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:558–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuether TA, Nesbit GM, Clark WM, Barnwell SL. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion: a mechanism of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:427–33. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199708000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Citow JS, Macdonald RL. Posterior decompression of the vertebral artery narrowed by cervical osteophyte: case report. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:495–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(98)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimura T, Sako K, Tohyama Y, Hodozuka A. Bow hunter’s stroke caused by simultaneous occlusion of both vertebral arteries. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999;141:895–6. doi: 10.1007/s007010050394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogino M, Kawamoto T, Asakuno K, Maeda Y, Kim P. Proper management of the rotational vertebral artery occlusion secondary to spondylosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2001;103:250–3. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(01)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Velat GJ, Reavey-Cantwell JF, Ulm AJ, Lewis SB. Intraoperative dynamic angiography to detect resolution of bow hunter’s syndrome: technical case report. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:420–3. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miele VJ, France JC, Rosen CL. Subaxial positional vertebral artery occlusion corrected by decompression and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:E366–70. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817192a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dargon PT, Liang CW, Kohal A, Dogan A, Barnwell SL, Landry GJ. Bilateral mechanical rotational vertebral artery occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:1076–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haimoto S, Nishimura Y, Hara M, et al. Surgical Treatment of rotational vertebral artery syndrome induced by spinal tumor: a case report and literature review. NMC Case Rep J. 2017;4:101–5. doi: 10.2176/nmccrj.cr.2016-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rendon R, Mannoia K, Reiman S, Hitchman L, Shutze W. Rotational vertebral artery occlusion secondary to completely extraosseous vertebral artery. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2018;5:14–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvscit.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bruneau M, Cornelius JF, George B. Microsurgical cervical nerve root decompression by anterolateral approach. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(1 Suppl):ONS108–13. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000193521.98836.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruneau M, Cornelius JF, George B. The selective microforaminotomy. In: Bruneau M, Spetzler RF, George B, editors. Pathology and surgery around the vertebral artery. Paris: Springer; 2011. pp. 227–46. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruneau M, George B. The lateral approach to the V2 segment of the vertebral artery. In: Bruneau M, Spetzler RF, George B, editors. Pathology and surgery around the vertebral artery. Paris: Springer; 2011. pp. 143–64. [Google Scholar]

- 58.George B, Laurian C. Surgical approach to the whole length of the vertebral artery with special reference to the third portion. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1980;51:259–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01406753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.George B, Lot G. Neurinomas of the first two cervical nerve roots: a series of 42 cases. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:917–23. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.6.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.George B, Bresson D, Bruneau M. Extrinsic compression of the vertebral artery. In: Bruneau M, Spetzler RF, George B, editors. Pathology and surgery around the vertebral artery. Paris: Springer; 2011. pp. 273–83. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lima Neto AC, Bittar R, Gattas GS, et al. Pathophysiology and diagnosis of vertebrobasilar insufficiency: a review of the literature. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;21:302–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mitchell JA. Changes in vertebral artery blood flow following normal rotation of the cervical spine. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:347–51. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Machaly SA, Senna MK, Sadek AG. Vertigo is associated with advanced degenerative changes in patients with cervical spondylosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1527–34. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olszewski J, Majak J, Pietkiewicz P, Luszcz C, Repetowski M. The association between positional vertebral and basilar artery flow lesion and prevalence of vertigo in patients with cervical spondylosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:680–4. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gomez CR, Cruz-Flores S, Malkoff MD, Sauer CM, Burch CM. Isolated vertigo as a manifestation of vertebrobasilar ischemia. Neurology. 1996;47:94–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moubayed SP, Saliba I. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency presenting as isolated positional vertigo or dizziness: a double-blind retrospective cohort study. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:2071–6. doi: 10.1002/lary.20597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toole JF, Tucker SH. Influence of head position upon cerebral circulation: studies on blood flow in cadavers. Arch Neurol. 1960;2:616–23. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1960.03840120022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bailey RW, Badgley CE. Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42-A:565–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robinson RA, Smith GW. Anterolateral cervical disc removal and interbody fusion for cervical disc syndrome. SAS J. 2010;4:34–5. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cloward RB. The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks. J Neurosurg. 1958;15:602–17. doi: 10.3171/jns.1958.15.6.0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kawashima M, Tanriover N, Rhoton AL, Jr, Matsushima T. The transverse process, intertransverse space, and vertebral artery in anterior approaches to the lower cervical spine. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(2 Suppl):188–94. doi: 10.3171/spi.2003.98.2.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hart AK, Greinwald JH, Jr, Shaffrey CI, Postma GN. Thoracic duct injury during anterior cervical discectomy: a rare complication: case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:151–4. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.1.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davis HK. A statistical study of the thoracic duct in man. Am J Anat. 1915;17:211–44. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gottlieb MI, Greenfield J. Variations in the terminal portion of the human thoracic duct. AMA Arch Surg. 1956;73:955–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1956.01280060055012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kinnaert P. Anatomical variations of the cervical portion of the thoracic duct in man. J Anat. 1973;115(Pt 1):45–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Van Pernis PA. Variations of the thoracic duct. Surgery. 1949;26:806–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ammar K, Tubbs RS, Smyth MD, et al. Anatomic landmarks for the cervical portion of the thoracic duct. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1385–8. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000093826.31666.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kiray A, Arman C, Naderi S, Guvencer M, Korman E. Surgical anatomy of the cervical sympathetic trunk. Clin Anat. 2005;18:179–85. doi: 10.1002/ca.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ebraheim NA, Lu J, Yang H, Heck BE, Yeasting RA. Vulnerability of the sympathetic trunk during the anterior approach to the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1603–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lyons AJ, Mills CC. Anatomical variants of the cervical sympathetic chain to be considered during neck dissection. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:180–2. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ricci A, Di Vitantonio H, De Paulis D, et al. Cortical aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery: a review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:117. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_50_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Del Maestro M, Luzzi S, Gallieni M, et al. Surgical treatment of arteriovenous malformations: role of preoperative staged embolization. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2018;129:109–13. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73739-3_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gallieni M, Del Maestro M, Luzzi S, Trovarelli D, Ricci A, Galzio R. Endoscope-assisted microneurosurgery for intracranial aneurysms: operative technique, reliability, and feasibility based on 14 years of personal experience. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2018;129:19–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73739-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luzzi S, Del Maestro M, Bongetta D, et al. Onyx Embolization before the surgical treatment of Grade III Spetzler-Martin brain arteriovenous malformations: single-center experience and technical nuances. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:e340–53. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Luzzi S, Gallieni M, Del Maestro M, Trovarelli D, Ricci A, Galzio R. Giant and very large intracranial aneurysms: surgical strategies and special issues. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2018;129:25–31. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-73739-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luzzi S, Del Maestro M, Galzio R. Letter to the editor: preoperative embolization of brain arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 2019:1–2. doi: 10.3171/2019.6.JNS191541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luzzi S, Elia A, Del Maestro M, et al. Indication, timing, and surgical treatment of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: systematic review and proposal of a management algorithm. World Neurosurg. 2019;S1878-8750(19):30105–6. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Luzzi S, Del Maestro M, Elbabaa SK, Galzio R. Letter to the editor regarding “one and done: multimodal treatment of pediatric cerebral arteriovenous malformations in a single anesthesia event”. World Neurosurg. 2020;134:660. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]