Abstract

目的

探讨固定后踝与否对不同 Haraguchi 分型后踝骨折临床疗效的影响。

方法

回顾分析 2015 年 1 月—2019 年 9 月收治且符合选择标准的 86 例三踝骨折患者临床资料。男 29 例,女 57 例;年龄 26~82 岁,平均 55.2 岁。按照 Haraguchi 分型进行分组,其中Ⅰ型组 38 例、Ⅱ型组 30 例、Ⅲ型组 18 例。3 组患者性别、年龄、骨折侧别等一般资料比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。术中Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ型组分别行后踝固定 23、21、5 例。记录并比较各分型组患者手术时间、骨折愈合时间、完全负重时间、术后关节平整度、关节退变程度。采用美国矫形足踝协会(AOFAS)踝与后足评分评价患者踝关节功能,包括疼痛、日常生活质量、关节活动度和关节稳定性 4 个方面。比较各分型组内后踝固定组与未固定组 AOFAS 踝与后足评分差异。

结果

各组患者均顺利完成手术,手术时间比较差异无统计学意义(F=3.677,P=0.159)。患者均获随访,随访时间 12~36 个月,平均 16.8 个月。末次随访时 6 例患者踝关节平整度欠佳,其中Ⅰ型组 2 例(5.3%)、Ⅱ型组 4 例(13.3%),各组间关节平整度比较差异无统计学意义(χ2=6.566,P=0.161)。各组患者踝关节均呈轻度退变;骨折均愈合良好,无骨折延迟愈合或不愈合发生,各组骨折愈合时间及完全负重时间比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。随访期间无切口感染、骨折移位及钢板螺钉松动、断裂等并发症发生。末次随访时,Ⅱ型组 AOFAS 踝与后足评分的总分和疼痛评分显著低于Ⅰ型组和Ⅲ型组(P<0.05),Ⅰ型组和Ⅲ型组间比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);各组日常生活质量、关节活动度及关节稳定性评分比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。除Ⅱ型组内未固定组疼痛和日常生活质量评分显著低于固定组(P<0.05)外,其余各型未固定组与固定组间比较各评分差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

结论

HaraguchiⅡ型后踝骨折较Ⅰ型和Ⅲ型预后更差,尤其在术后疼痛方面,后踝切开复位内固定能显著改善其预后;Ⅰ型和Ⅲ型后踝固定与否对预后影响较小。

Keywords: 三踝骨折, 后踝, 内固定术, Haraguchi 分型

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effectiveness of fixation the posterior malleolus or not to treat different Haraguchi’s classification of posterior malleolus fractures.

Methods

The clinical data of 86 trimalleolar fracture patients who were admitted between January 2015 and September 2019 and met the selection criteria were retrospectively reviewed. There were 29 males and 57 females; the age ranged from 26 to 82 years with a mean age of 55.2 years. According to Haraguchi’s classification, 38 patients were in type Ⅰ group, 30 patients in type Ⅱ group, and 18 patients in type Ⅲ group. There was no significant difference in the general data such as gender, age, and fracture location among the 3 groups (P>0.05). The fixation of the posterior malleolus was performed in 23, 21, and 5 patients in type Ⅰ, Ⅱ, and Ⅲ groups, respectively. The operation time, fracture healing time, full weight-bearing time, postoperative joint flatness, and joint degeneration degree of the patients in each group were recorded and compared. The American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) ankle and hindfoot score was used to evaluate ankle function, including pain, quality of daily life, joint range of motion, and joint stability. The AOFAS scores were compared between fixation and non-fixation groups in each group.

Results

The procedure was successfully completed by all patients in each group, and there was no significant difference in operation time (F=3.677, P=0.159). All patients were followed up 12-36 months with a mean time of 16.8 months. At last follow-up, 6 patients were found to have suboptimal ankle planarity, including 2 patients (5.3%) in the type Ⅰ group and 4 patients (13.3%) in the type Ⅱ group, with no significant difference between groups (χ2=6.566, P=0.161). The ankle joints of all the patients in each group showed mild degeneration; the fractures all healed well and no delayed union or nonunion occurred. There was no significant difference in the fracture healing time and full weight-bearing time between groups (P>0.05). No complications such as incision infection, fracture displacement, or plate screw loosening and fracture occurred during follow-up. At last follow-up, the total scores and pain scores of the AOFAS scores in the type Ⅱ group were significantly lower than those in the type Ⅰand Ⅲ groups (P<0.05), there was no significant difference between groups in the scores for the quality of daily life, joint range of motion, and joint stability between groups (P>0.05). There was no significant difference in any of the scores between the unfixed and fixed groups, except for the pain and quality of daily life scores, which were significantly lower (P<0.05) in the unfixed group of type Ⅱ group than the fixed group.

Conclusion

Haraguchi type Ⅱ posterior malleolus fractures have a worse prognosis than types Ⅰ and Ⅲ fractures, especially in terms of postoperative pain, which can be significantly improved by fixing the posterior malleolus; the presence or absence of posterior malleolus fixation in types Ⅰ and Ⅲ has less influence on prognosis.

Keywords: Trimalleolar fracture, posterior malleolus, internal fixation, Haraguchi classification

踝关节骨折是一种常见损伤,每年发病率为(122~187)/10 万[1],其中三踝骨折占所有踝关节骨折的 7%~12%。合并后踝骨折的患者往往术后功能恢复及预后不满意,可能发生关节移位、畸形等,长期关节不稳定易引起创伤性关节炎等严重并发症[2]。这可能与后踝在踝关节负重与稳定中发挥重要生物力学作用有关[3-4]。因此,后踝骨折患者治疗方式的选择至关重要。但并非所有后踝骨折都需要手术[5],目前普遍认为踝关节侧位 X 线片上后踝骨折块超过关节面 25% 或移位超过 2 mm 的患者应接受手术治疗,但以关节面骨折块面积来决定是否手术治疗仍存在争议。龚晓峰等[6]认为后踝骨折块超过关节面 15% 即可选择手术治疗,McHale 等[7]和戴坤权等[8]则表示超过 10% 就应行内固定治疗。然而越来越多研究表明,后踝骨折手术与否需着重考虑后踝骨折的形态学特征,而不仅仅单纯考虑骨折块大小[9-10]。

既往评估后踝骨折均采用踝关节正侧位 X 线片,很难发现踝关节真实受累情况。随着医学影像技术的发展,多排螺旋 CT 三维重建技术可提供更全面的骨折信息,在踝关节骨折诊断中应用越来越广泛。Haraguchi 分型[11]是目前最常用的踝关节骨折分型之一,其优势在于根据踝关节 CT 胫骨远端横断面对后踝骨折形态进行分型。因此,本研究通过回顾 2015 年 1 月—2019 年 9 月手术治疗的三踝骨折患者临床资料,旨在探讨固定后踝与否对不同 Haraguchi 分型后踝骨折疗效的影响,以期为三踝骨折的治疗提供新思路。报告如下

1. 临床资料

1.1. 患者选择标准

纳入标准:① 确诊为三踝骨折;② 有完整病历及影像学资料,包括手术前后踝关节正侧位 X 线片和术前踝关节 CT 平扫及三维重建;③ 骨折前踝关节功能无障碍,且无严重踝关节疾病;④ 随访时间 1 年以上。排除标准:① 非外伤性踝关节骨折;② 双侧踝关节骨折;③ 骨折至手术时间>3 周;④ 合并严重心肺疾病,一般情况差不能耐受手术者。2015 年 1 月—2019 年 9 月共 86 例患者符合选择标准纳入研究。

1.2. 一般资料

本组男 29 例,女 57 例;年龄 26~82 岁,平均 55.2 岁。骨折位于左踝 43 例,右踝 43 例;伴有踝关节脱位 21 例。术前均行踝关节正侧位 X 线片检查和 CT 平扫及三维重建评估骨折情况。按照 Haraguchi 分型进行分组,其中Ⅰ型组 38 例、Ⅱ型组 30 例、Ⅲ型组 18 例。3 组患者性别、年龄、骨折侧别等一般资料比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),具有可比性。见表 1。

表 1.

Comparison of general information of patients in each group

各组患者一般资料比较

| 组别

Group |

例数

n |

性别

Gender |

年龄(岁)

Age (years) |

骨折侧别

Fracture site |

||

| 男

Male |

女

Female |

左踝

Left ankle |

右踝

Right ankle |

|||

| Ⅰ型

TypeⅠ |

38 | 13 | 25 | 53.8±13.0 | 17 | 21 |

| Ⅱ型

TypeⅡ |

30 | 8 | 22 | 56.8±13.5 | 17 | 13 |

| Ⅲ型

TypeⅢ |

18 | 8 | 10 | 55.5±11.6 | 9 | 9 |

| 统计值

Statistic |

χ2=1.598

P=0.487 |

F=0.453

P=0.637 |

χ2=0.621

P=0.644 |

|||

1.3. 治疗方法

术前常规进行外固定,给予消肿、止痛、调节骨代谢等对症处理,待踝关节皮肤出现褶皱后进行手术。通过踝关节外侧入路暴露外踝,手法复位满意后使用钢板在腓骨远端进行内固定。视主刀医生临床经验决定是否对后踝骨折进行内固定(Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ型组分别行后踝固定 23、21、5 例)。通过外踝原切口(10 例)或踝关节后内侧入路(2 例)对后踝进行复位内固定,或直接采用拉力螺钉经皮固定后踝(37 例)。所有患者内踝骨折经内侧弧形切口复位后,用螺钉进行内固定。若存在下胫腓联合不稳定(24 例),则用 1~2 枚螺钉从外踝穿腓骨和胫骨外侧 3 层皮质进行固定。

1.4. 术后处理及疗效评价标准

术后 3 d 开始进行踝关节主、被动功能锻炼,术后 6~8 周开始负重锻炼。

术后定期随访,复查踝关节正侧位 X 线片或 CT 平扫及三维重建。记录并比较各分型组患者手术时间、骨折愈合时间、完全负重时间、术后关节平整度、关节退变程度。其中,关节平整度评价包括正常和欠佳,正常定义为无后踝移位或后踝关节面移位≤1 mm,欠佳定义为后踝关节面移位>1 mm[8]。关节退变程度参照 Domsic 等[12]提出的踝关节炎分级法进行评价,分为正常、轻度(有骨赘形成但无关节狭窄)、中度(骨赘形成并关节狭窄)及重度(关节严重狭窄或无关节间隙)。采用美国矫形足踝协会(AOFAS)踝与后足评分[13]评价患者踝关节功能,包括疼痛、日常生活质量、关节活动度和关节稳定性 4 个方面。比较各分型组内后踝固定组与未固定组 AOFAS 踝与后足评分差异。

1.5. 统计学方法

采用 SPSS26.0 统计软件进行分析。计量资料以均数±标准差表示,组间比较采用单因素方差分析,两两比较采用 SNK 检验;计数资料以率或构成比表示,组间比较采用 χ2 检验;等级资料组间比较采用秩和检验;检验水准 α=0.05。

2. 结果

各组患者均顺利完成手术,手术时间比较差异无统计学意义(F=3.677,P=0.159)。患者均获随访,随访时间 12~36 个月,平均 16.8 个月。末次随访时 6 例患者踝关节平整度欠佳,其中Ⅰ型组 2 例(5.3%)、Ⅱ型组 4 例(13.3%),各组间关节平整度比较差异无统计学意义(χ2=6.566,P=0.161)。各组患者踝关节均呈轻度退变;骨折均愈合良好,无骨折延迟愈合或不愈合发生,各组骨折愈合时间及完全负重时间比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 2。随访期间无切口感染、骨折移位及钢板螺钉松动、断裂等并发症发生。见图 1~3。末次随访时,Ⅱ型组 AOFAS 踝与后足评分的总分和疼痛评分显著低于Ⅰ型组和Ⅲ型组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),Ⅰ型组和Ⅲ型组间比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);各组日常生活质量、关节活动度及关节稳定性评分比较差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 3。除Ⅱ型组内未固定组疼痛和日常生活质量评分显著低于固定组(P<0.05)外,其余各型未固定组与固定组间比较各评分差异均无统计学意义(P>0.05)。见表 4~6。因踇长屈肌及腓骨肌受内固定物干扰,目前已有 33 例患者于术后 1 年后取出内固定物。

表 2.

Comparison of clinical indexes of different Haraguchi classification groups

各分型组患者各临床指标比较

| 组别

Group |

例数

n |

手术时间(min)

Operation time (minutes) |

骨折愈合时间(d)

Fracture healing time (days) |

完全负重时间(d)

Full weight-bearing time (days) |

术后关节平整度

Postoperative joint flatness |

|

| 正常

Normal |

欠佳

Poor |

|||||

| Ⅰ型

TypeⅠ |

38 | 132.1±41.6 | 67.0±2.4 | 78.1±3.4 | 36 | 2 |

| Ⅱ型

TypeⅡ |

30 | 140.6±46.9 | 68.5±3.9 | 79.8±5.5 | 26 | 4 |

| Ⅲ型

TypeⅢ |

18 | 113.9±41.9 | 65.5±3.6 | 76.9±5.7 | 18 | 0 |

| 统计值

Statistic |

F=3.677

P=0.159 |

F=5.800

P=0.055 |

F=1.945

P=0.378 |

χ2=6.566

P=0.161 |

||

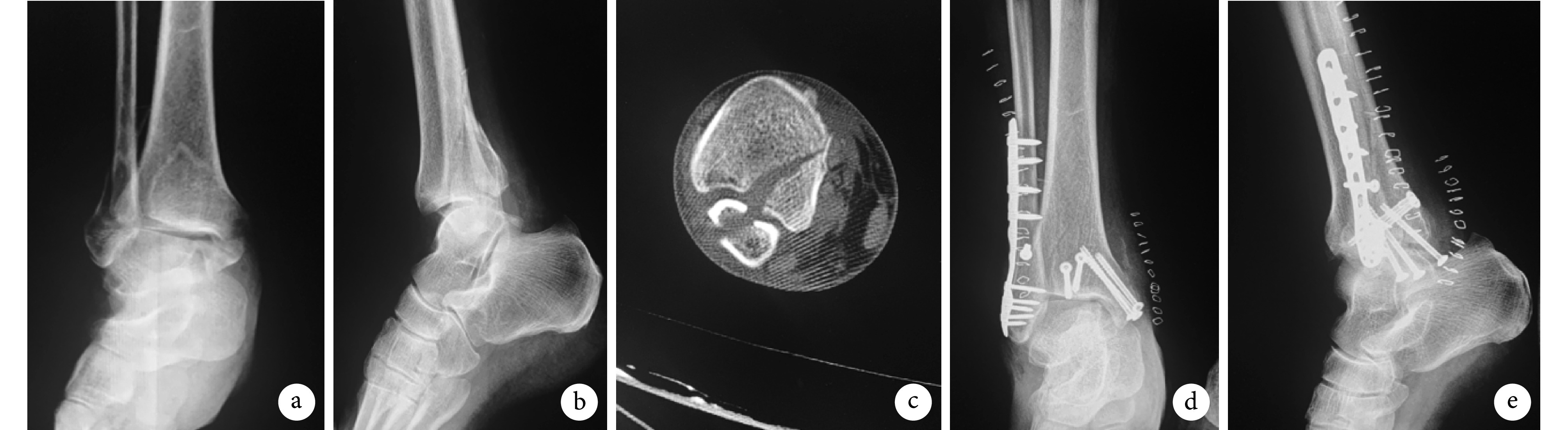

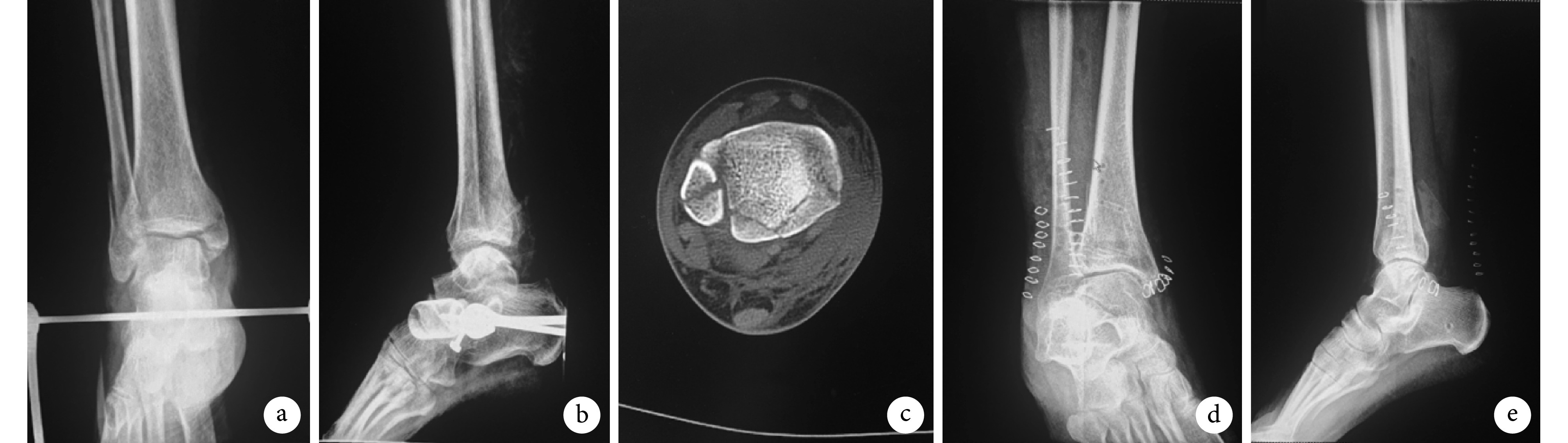

图 1.

A 71-year-old male patient with right trimalleolar fracture who was treated with internal fixation of the posterior malleolus fracture in type Ⅰ group

Ⅰ型组患者,男,71 岁,右侧三踝骨折,后踝行内固定

a、b. 术前正侧位 X 线片示右踝关节骨折;c. 术前 CT 示后踝骨折伴移位;d、e. 术后 12 个月正侧位 X 线片示骨折愈合,踝关节内固定物在位,后踝轻度关节退变

a, b. Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral X-ray films showed a fracture of the right ankle joint; c. Preoperative CT showed a posterior ankle fracture with displacement; d, e. Anteroposterior and lateral X-ray films at 12 months after operation showed fracture healing, three ankles internal fixator in place, and mild degeneration of the posterior ankle joint

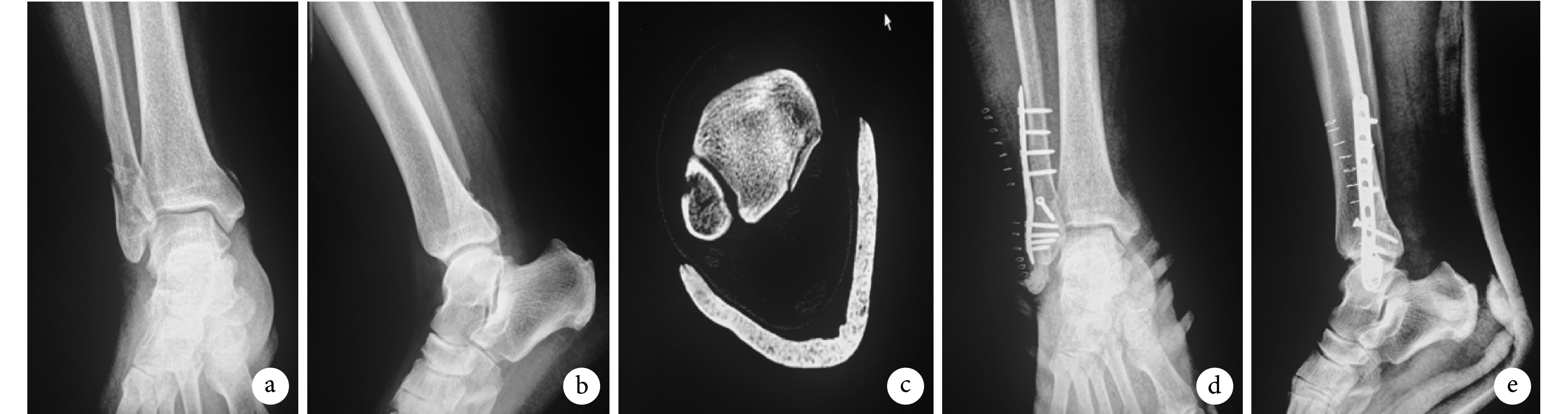

图 3.

A 69-year-old male patient with right trimalleolar fracture in type Ⅲ group, the posterior malleolus fracture wasn’t internally fixeda, b. Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral X-ray films showed a fracture of the right ankle joint; c. Preoperative CT showed a posterior ankle fracture with displacement; d, e. Anteroposterior and lateral X-ray films at 16 months after operation showed fracture healing, three ankles internal fixator in place, and mild degeneration of the posterior ankle joint

Ⅲ型组患者,男,69 岁,右侧三踝骨折,后踝未行内固定

a、b. 术前正侧位 X 线片示右踝关节骨折;c. 术前 CT 示后踝骨折伴移位;d、e. 术后 16 个月正侧位 X 线片示骨折愈合,踝关节内固定物在位,后踝轻度关节退变

表 3.

Comparison of AOFAS ankle and hindfoot score of different Haraguchi classification groups at last follow-up (

)

)

各分型组末次随访时 AOFAS 踝与后足评分比较(

)

)

| 组别

Group |

例数

n |

总分

Total |

疼痛

Pain |

日常生活质量

Quality of daily life |

关节活动度

Joint range of motion |

关节稳定性

Joint stability |

|

*与Ⅰ型组比较 P<0.05,#与Ⅲ型组比较 P<0.05

*Compared with typeⅠgroup, P<0.05;#compared with type Ⅲ group, P<0.05 | ||||||

| Ⅰ型

TypeⅠ |

38 | 92.4±4.0 | 38.0±1.5 | 24.5±1.2 | 13.4±0.5 | 16.5±1.2 |

| Ⅱ型

TypeⅡ |

30 | 89.7±4.3*# | 36.7±1.4*# | 23.5±1.8 | 13.5±0.5 | 15.9±1.5 |

| Ⅲ型

Type Ⅲ |

18 | 92.1±3.6 | 37.9±1.4 | 24.4±1.1 | 13.5±0.5 | 16.3±1.0 |

| 统计值

Statistic |

F=4.103

P=0.036 |

F=7.775

P=0.002 |

F=4.215

P=0.079 |

F=0.437

P=0.642 |

F=1.725

P=0.208 |

|

表 4.

Comparison of AOFAS ankle and hindfoot score between posterior malleolus fixed group and non-fixed group in Haraguchi type Ⅰ group at last follow-up (

)

)

末次随访时 HaraguchiⅠ型组中后踝固定与未固定组 AOFAS 踝与后足评分比较(

)

)

| 组别

Group |

例数

n |

总分

Total |

疼痛

Pain |

日常生活质量

Quality of daily life |

关节活动度

Joint range of motion |

关节稳定性

Joint stability |

| 固定组

Fixed group |

23 | 92.4±4.1 | 38.1±1.4 | 24.5±1.0 | 13.4±0.5 | 16.4±1.5 |

| 未固定组

Non-fixed group |

15 | 92.5±4.1 | 37.9±1.6 | 24.4±1.4 | 13.5±0.5 | 16.7±0.9 |

| 统计值

Statistic |

F=0.045

P=0.964 |

F=0.457

P=0.648 |

F=0.370

P=0.711 |

F=0.454

P=0.650 |

F=0.635

P=0.526 |

表 6.

Comparison of AOFAS ankle and hindfoot score between posterior malleolus fixed group and non-fixed group in Haraguchi type Ⅲ group at last follow-up (

)

)

末次随访时 HaraguchiⅢ型组中后踝固定与未固定组 AOFAS 踝与后足评分比较(

)

)

| 组别

Group |

例数

n |

总分

Total |

疼痛

Pain |

日常生活质量

Quality of daily life |

关节活动度

Joint range of motion |

关节稳定性

Joint stability |

| 固定组

Fixed group |

5 | 92.0±4.2 | 38.0±1.6 | 24.4±1.1 | 13.4±0.6 | 16.2±1.3 |

| 未固定组

Non-fixed group |

13 | 92.2±3.5 | 37.9±1.3 | 24.4±1.1 | 13.5±0.5 | 16.3±1.0 |

| 统计值

Statistic |

F=0.050

P=0.960 |

F=0.101

P=0.920 |

F=0.051

P=0.959 |

F=0.511

P=0.609 |

F=0.257

P=0.797 |

图 2.

A 37-year-old female patient with right trimalleolar fracture who was treated with internal fixation of the posterior malleolus fracture in type Ⅱ group

Ⅱ型组患者,女,37 岁,右侧三踝骨折,后踝行内固定

a、b. 术前正侧位 X 线片示右踝关节骨折;c. 术前 CT 示后踝骨折伴移位;d、e. 术后 18 个月正侧位 X 线片示骨折愈合,内固定物已拆除,后踝轻度关节退变

a, b. Preoperative anteroposterior and lateral X-ray films showed a fracture of the right ankle joint; c. Preoperative CT showed a posterior ankle fracture with displacement; d, e. Anteroposterior and lateral X-ray films at 18 months after operation showed fracture healing, the internal fixator had been removed, and mild degeneration of the posterior ankle joint

表 5.

Comparison of AOFAS ankle and hindfoot score between posterior malleolus fixed group and non-fixed group in Haraguchi type Ⅱ group at last follow-up (

)

)

末次随访时 HaraguchiⅡ型组中后踝固定与未固定组 AOFAS 踝与后足评分比较(

)

)

| 组别

Group |

例数

n |

总分

Total |

疼痛

Pain |

日常生活质量

Quality of daily life |

关节活动度

Joint range of motion |

关节稳定性

Joint stability |

| 固定组

Fixed group |

21 | 90.6±4.0 | 37.1±1.4 | 24.1±1.4 | 13.5±0.5 | 15.9±1.6 |

| 未固定组

Non-fixed group |

9 | 87.6±4.4 | 35.9±0.9 | 22.2±1.9 | 13.6±0.5 | 15.9±1.5 |

| 统计值

Statistic |

F=1.820

P=0.069 |

F=2.299

P=0.022 |

F=2.599

P=0.009 |

F=0.157

P=0.875 |

F=0.069

P=0.945 |

3. 讨论

3.1. 后踝骨折分型

目前最常用的踝关节骨折分型为 Lauge-Hansen 分型、Danis-Weber 分型及 Haraguchi 分型。3 种分型各有优缺点,Lauge-Hansen 分型能够清晰体现受伤时足姿势及外力方向与韧带损伤或骨折间的关系,虽然对治疗方法的选择具有重要指导作用,但并未详细描述后踝骨折损伤;而 Danis-Weber 分型仅着重强调了腓骨骨折的治疗,也缺乏对后踝骨折的详细描述。上述两种分型在判断踝关节骨折时均基于踝关节侧位 X 线片,由于 X 线片分辨率较低且为单一维度成像,故很难发现真实的后踝受累情况。因此,Haraguchi 等[11]通过分析 57 例后踝骨折患者的踝关节 CT 资料,最终确定根据 CT 胫骨远端横断面的后踝骨折形态进行分型,Ⅰ型为后外侧斜形(约占 67%),Ⅱ型为内侧延伸形(约占 19%),Ⅲ型为小撕脱形(约占 14%),表明 Haraguchi 分型可描述后踝骨折形态进而指导临床治疗。

3.2. 后踝骨折形态与踝关节功能预后之间的关系

内、外踝骨折时行内固定治疗预后良好,但合并后踝骨折时,患者术后满意度往往较低,同时可能出现踝关节不稳、创伤后关节炎等严重并发症,预后较差[2]。随着 CT 后处理技术在临床的广泛应用,后踝骨折的形态学特点逐渐被学者们重视[14-16]。Blom 等[17]通过对 73 例旋转型踝关节骨折患者进行多元回归分析,发现是后踝骨折形态而并非后踝骨折块大小决定了患者预后。2020 年,Blom 等[9]进一步对 70 例后踝骨折患者进行队列研究,在双变量分析中后踝骨折形态(P=0.039)及骨折块大小(P=0.007)均与预后显著相关,但是多变量分析中仅后踝骨折形态(P=0.001)影响预后。

我们的研究结果显示,HaraguchiⅡ型组末次随访时 AOFAS 踝与后足评分总分及疼痛评分均低于Ⅰ型组和Ⅲ型组,表明后踝骨折线延伸至内侧的踝关节骨折(HaraguchiⅡ型)预后较其他类型差。Verhage 等[18]通过对 243 例踝关节骨折患者术后远期功能和影像学结果分析,认为当骨折线累及内踝时,其功能预后较其他踝关节骨折类型患者更差。其原因可能与 HaraguchiⅡ型骨折发生机制有关,当踝关节处于跖屈位时,距骨旋转后撞击后踝导致后踝骨折,常同时伴有后外侧骨折块和后内侧骨折块,前者通过下胫腓后韧带与腓骨远端相连维持其稳定性,而后者无坚韧软组织与腓骨相连,常处于孤立状态易导致距骨脱位[19]。所以,后踝骨折线累及内侧时,往往伴有较高的创伤性关节炎发生率,从而导致预后不佳。因此,我们认为后踝骨折形态可能影响后踝骨折患者的预后,而 Haraguchi Ⅱ型后踝骨折较其他类型骨折预后更差,尤其在术后疼痛发生方面。在选择后踝骨折的治疗方案时,临床医生应更加倾向于基于后踝骨折形态学方面,而后踝骨折块大小、移位程度仅是众多参考指标之一。

3.3. Ⅱ型后踝骨折术中固定后踝的重要性

本研究发现在 HaraguchiⅡ型患者中,后踝固定组末次随访时 AOFAS 踝与后足评分中的疼痛和日常生活质量评分均高于未固定组,而其余类型骨折中固定后踝与否其预后差异无统计学意义,表明在Ⅱ型组中固定后踝能够提高术后疗效,而对Ⅰ型和Ⅲ型影响较小。尽管临床对于后踝骨折是否内固定尚无统一意见,但是当后踝骨折线延伸至内侧(HaraguchiⅡ型)时,文献报道多采用切开复位内固定治疗[20-23]。Mangnus 等[24]通过 CT 图像的 Cole 骨折绘图法对 45 例后踝骨折进行定性分析研究,结果发现 Haraguchi Ⅱ型采用切开复位内固定治疗效果更佳。另外,有学者[25]将骨折线延伸至内侧的后踝骨折称为后 Pilon 骨折。张光明等[26]对后 Pilon 骨折形态和损伤机制进行三维有限元分析,结果提示复位及固定后内侧骨折块至关重要。当后踝骨折为 HaraguchiⅡ型时,绝大多数患者关节面存在压缩嵌顿的骨软骨块,增加后踝受累范围及关节不稳定程度,因此后内侧骨块必须及时坚强固定。

HaraguchiⅡ型后踝骨折需要坚强固定的原因可能有两点:第一,胫骨远端后内侧骨折块为 HaraguchiⅡ型后踝骨折的关键骨折块,可防止距骨向后脱位且其后方紧贴胫后肌腱,故需行内固定治疗;第二,三角韧带可限制距骨外旋、外翻,是踝关节内侧最重要的稳定结构,其部分附着于后内侧骨折块上,当后者发生移位时前者连续性未中断,故复位后内侧骨折块可恢复三角韧带正常解剖结构,从而增加踝关节内侧稳定性。由此可见,固定后踝对于 HaraguchiⅡ型骨折恢复后踝骨性结构、修复关节面、重建踝关节稳定性具有重要意义,因此绝大多数骨科医生会对该型后踝骨折选择内固定治疗。近年研究[27-30]认为直接切开复位钢板内固定后踝骨折,在生物力学、临床疗效等方面优于间接复位和经皮螺钉固定。所以本研究认为,对于 HaraguchiⅡ型后踝骨折,不论骨折块大小均应行切开复位内固定术,而Ⅰ型和Ⅲ型是否固定后踝对预后影响较小。

综上述,Haraguchi Ⅱ型骨折患者较其他类型患者预后更差,尤其在术后疼痛发生方面,手术切开复位内固定后踝能够明显提高该型患者术后治疗效果,且患者的踝关节、后足功能恢复更好。

作者贡献:陈烽负责数据收集整理、统计分析及起草文章;安忠诚负责实验设计及实施、对文章的知识性内容进行修改及审阅;周芳负责对文章的知识性内容进行修改及审阅;范佳俊、高威负责数据收集整理及统计分析;陈哲负责科研设计。

利益冲突:所有作者声明,在课题研究及文章撰写过程中不存在利益冲突。

机构伦理问题:研究方案经浙江中医药大学附属第二医院伦理委员会批准(2020-KL-152-01)。

References

- 1.Kortekangas T, Haapasalo H, Flinkkilä T, et al Three week versus six week immobilisation for stable Weber B type ankle fractures: randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority clinical trial. BMJ. 2019;364:k5432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.许腾飞, 龙毅 微型钢板内固定与螺钉内固定治疗后踝关节骨折患者的疗效比较. 创伤外科杂志. 2020;22(7):547–550. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evers J, Fischer M, Raschke M, et al. Leave it or fix it? How fixation of a small posterior malleolar fragment neutralizes rotational forces in trimalleolar fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00402-021-03772-9.

- 4.Ochman S, Raschke MJ Ankle fractures in older patients: What should we do differently? Unfallchirurg. 2021;124(3):200–211. doi: 10.1007/s00113-021-00953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.李庭, 孙志坚, 柴益民, 等 ERAS理念下踝关节骨折诊疗方案优化的专家共识. 中华骨与关节外科杂志. 2019;12(1):3–12. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-9958.2019.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.龚晓峰, 武勇, 吕艳伟, 等 后踝骨折手术治疗的指征. 中华创伤骨科杂志. 2015;17(3):232–237. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-7600.2015.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHale S, Williams M, Ball T Retrospective cohort study of operatively treated ankle fractures involving the posterior malleolus. Foot Ankle Surg. 2020;26(2):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.戴坤权, 姚粤峰, 熊奡, 等 不同大小后踝骨折块的手术选择及疗效分析. 中华骨与关节外科杂志. 2020;13(4):304–308. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-9958.2020.04.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blom RP, Hayat B, Al-Dirini RMA, et al Posterior malleolar ankle fractures. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B(9):1229–1241. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B9.BJJ-2019-1660.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.廖明新, 王岩 后踝骨折的治疗与研究进展. 骨科临床与研究杂志. 2019;4(1):50–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haraguchi N, Haruyama H, Toga H, et al Pathoanatomy of posterior malleolar fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(5):1085–1092. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domsic RT, Saltzman CL Ankle osteoarthritis scale. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(7):466–471. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasenstein T, Greene T, Meyr AJ A 5-year review of clinical outcome measures published in the Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association and the Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2017;107(3):176–179. doi: 10.7547/16-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evers J, Barz L, Wähnert D, et al Size matters: The influence of the posterior fragment on patient outcomes in trimalleolar ankle fractures. Injury. 2015;46 Suppl 4:S109–113. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(15)30028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tenenbaum S, Shazar N, Bruck N, et al Posterior malleolus fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2017;48(1):81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mak MF, Stern R, Assal M Repair of syndesmosis injury in ankle fractures: Current state of the art. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3(1):24–29. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blom RP, Meijer DT, de Muinck Keizer RO, et al Posterior malleolar fracture morphology determines outcome in rotational type ankle fractures. Injury. 2019;50(7):1392–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verhage SM, Boot F, Schipper IB, et al Open reduction and internal fixation of posterior malleolar fractures using the posterolateral approach. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(6):812–817. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B6.36497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert LA, Falconer L, Mason L Ankle stability in ankle fracture. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(3):375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Smith CD, White E, et al A systematic review of the role of surgical approaches on the outcomes of the tibia pilon fracture. Foot Ankle Spec. 2016;9(2):163–168. doi: 10.1177/1938640015620637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Wang H, Pen C, et al. Characteristics and proposed classification system of posterior pilon fractures. Medicine (Baltimore), 2019, 98(3): e14133. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014133.

- 22.何锦泉, 马信龙, 马宝通, 等 后踝骨折分型及治疗的研究进展. 中华骨科杂志. 2016;36(13):863–870. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2352.2016.13.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi Y, Chun DI, Won SH, et al. Morphological characteristics of the posterior malleolar fragment according to ankle fracture patterns: a computed tomography-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2018, 19(1): 51. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-1974-1.

- 24.Mangnus L, Meijer DT, Stufkens SA, et al Posterior malleolar fracture patterns. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(9):428–435. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klammer G, Kadakia AR, Joos DA, et al Posterior pilon fractures: a retrospective case series and proposed classification system. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(2):189–199. doi: 10.1177/1071100712469334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.张光明, 阮志勇, 丁声龙, 等 Pilon变异的后踝骨折的形态分析和损伤机制的三维有限元分析. 中华实验外科杂志. 2018;35(11):2035–2038. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-9030.2018.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goost H, Wimmer MD, Barg A, et al Fractures of the ankle joint: investigation and treatment options. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(21):377–388. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solan MC, Sakellariou A Posterior malleolus fractures: worth fixing. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(11):1413–1419. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B11.BJJ-2017-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartoníček J, Rammelt S, Tuček M Posterior malleolar fractures: Changing concepts and recent developments. Foot Ankle Clin. 2017;22(1):125–145. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baumbach SF, Herterich V, Damblemont A, et al Open reduction and internal fixation of the posterior malleolus fragment frequently restores syndesmotic stability. Injury. 2019;50(2):564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]