Key Points

Question

Is race associated with COVID-19 testing and hospital outcomes in children in England?

Findings

In this cohort study of 2 576 353 children (0-18 years of age) in England with COVID-19 disease, children who were Black, Asian, or of mixed race had lower proportions of SARS-CoV-2 tests and had higher positive results and COVID-19 hospitalizations compared with White children. These results held after key demographic factors and selected comorbidities were accounted for.

Meaning

These findings suggest that race may play an important role in childhood COVID-19 outcomes, which reinforces the continued need for a race-tailored focus on health system performance and targeted public health interventions.

Abstract

Importance

Although children mainly experience mild COVID-19 disease, hospitalization rates are increasing, with limited understanding of underlying factors. There is an established association between race and severe COVID-19 outcomes in adults in England; however, whether a similar association exists in children is unclear.

Objective

To investigate the association between race and childhood COVID-19 testing and hospital outcomes.

Design, Setting, Participants

In this cohort study, children (0-18 years of age) from participating family practices in England were identified in the QResearch database between January 24 and November 30, 2020. The QResearch database has individually linked patients with national SARS-CoV-2 testing, hospital admission, and mortality data.

Exposures

The main characteristic of interest is self-reported race. Other exposures were age, sex, deprivation level, geographic region, household size, and comorbidities (asthma; diabetes; and cardiac, neurologic, and hematologic conditions).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was hospital admission with confirmed COVID-19. Secondary outcomes were SARS-CoV-2–positive test result and any hospital attendance with confirmed COVID-19 and intensive care admission.

Results

Of 2 576 353 children (mean [SD] age, 9.23 [5.24] years; 48.8% female), 410 726 (15.9%) were tested for SARS-CoV-2 and 26 322 (6.4%) tested positive. A total of 1853 children (0.07%) with confirmed COVID-19 attended hospital, 343 (0.01%) were admitted to the hospital, and 73 (0.002%) required intensive care. Testing varied across race. White children had the highest proportion of SARS-CoV-2 tests (223 701/1 311 041 [17.1%]), whereas Asian children (33 213/243 545 [13.6%]), Black children (7727/93 620 [8.3%]), and children of mixed or other races (18 971/147 529 [12.9%]) had lower proportions. Compared with White children, Asian children were more likely to have COVID-19 hospital admissions (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.62; 95% CI, 1.12-2.36), whereas Black children (adjusted OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.90-2.31) and children of mixed or other races (adjusted OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.93-2.10) had comparable hospital admissions. Asian children were more likely to be admitted to intensive care (adjusted OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.07-4.14), and Black children (adjusted OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.08-4.94) and children of mixed or other races (adjusted OR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.25-3.65) had longer hospital admissions (≥36 hours).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this large population-based study exploring the association between race and childhood COVID-19 testing and hospital outcomes, several race-specific disparities were observed in severe COVID-19 outcomes. However, ascertainment bias and residual confounding in this cohort study should be considered before drawing any further conclusions. Overall, findings of this study have important public health implications internationally.

This cohort study investigates the association between race and childhood COVID-19 testing and hospital outcomes in children from family practices in England.

Introduction

Approximately 10% of COVID-19 cases involve children up to the age of 18 years.1,2 Although children with COVID-19 largely experience mild disease, hospitalization rates are steadily increasing,3 and the underlying factors associated with severe outcomes have not been comprehensively explored. Only a small number of observational studies4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 have focused on children with COVID-19, and these studies4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 have mainly concentrated on age, sex, and preexisting comorbidities.

There is an established association between race/ethnicity and severe COVID-19 outcomes in adults, including hospitalizations and mortality.13,14,15,16 Disentangling the factors associated with these differences in adults is challenging. A combination of clinical factors, including higher prevalence of underlying chronic diseases in racial/ethnic minorities, and sociodemographic factors, including deprivation, key worker status, housing, and household size, are thought to play important roles.17 Whether a similar association between race/ethnicity and severe COVID-19 exists in children is not well established. To our knowledge, no population-based studies to date have directly explored race and SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 hospitalization risk in children, while accounting for important clinical and sociodemographic factors.

Current insight into the association between race and COVID-19 outcomes in children is based on descriptive observational studies from the UK4,18 and the US.5 In the UK, 2 studies, a case series of 5 children18 and a cohort of 651 children,4 reported on differences according to ethnicity and race, respectively, in COVID-19 outcomes, but both were limited to the first wave of the pandemic and hospitalized children. In the US, a descriptive cohort of 135 794 children tested for SARS-CoV-2 from a network of 7 US pediatric health systems5 reported race/ethnicity-specific differences in outcomes, however, without directly accounting for other potential mediating factors, such as family demographics. We aimed to investigate the association between race and childhood (0-18 years of age) COVID-19 testing and hospital outcomes, while accounting for sociodemographic and clinical factors, using linked electronic health record data.

Methods

Data Sources

The QResearch database (version 45) is a national, integrated database that consists of 35 million anonymized health records across all ages from approximately 1300 family practices across England,19 representing 20% of the UK population. Established in 2002, it is a not-for-profit collaboration between the University of Oxford and Egton Medical Information Systems, the leading clinical computer supplier for family practices in the UK.20 The database has ethical approval from the East Midlands–Derby Research Ethics Committee and has been extensively used for epidemiologic research, including COVID-19 research.15,21,22,23,24 QResearch only has anonymized data, and there is no requirement under the ethics approval for individual consent. Our study was conducted and findings reported in line with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline and the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Data (RECORD) guidelines.25,26

Primary care medical records consist of patient-level demographic information, including sex, self- or parent-assigned race, deprivation score, and household size, as well as clinical data, including clinical measurements and diagnoses. These records in QResearch are linked to the following: (1) hospital admission data (including intensive care unit [ICU] admissions) via Hospital Episode Statistics,27 a database that contains details for admissions and emergency attendances to all National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England; (2) civil registration (including mortality) data through the Office for National Statistics28; and (3) positive and negative SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test results undertaken in hospital and community settings in England through the National Infectious Disease Surveillance System provided by Public Health England.29,30

Data are linked at individual patient level using an anonymized identifier based on the NHS number. The NHS number is valid and complete in 99.8% of primary care and civil registry data as well as 98% of hospital admissions data.19,31

Study Population and Outcomes

The study population was a closed cohort of children from birth up through 18 years of age, registered with participating family practices in the QResearch database between January 24, 2020 (ie, the date of the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the UK), until the latest date for which data were available (October 31, 2020, for hospital admissions and November 30, 2020, for test results).

The primary outcome of interest was hospital admission for confirmed COVID-19 infection. The NHS England definition of hospital admission was used (ie, any COVID-19 admission with a confirmed positive COVID-19 RT-PCR test result in last 14 days32 or an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code of U07.1 or U07.2). Secondary outcomes included the following: (1) COVID-19 ICU admission via Hospital Episode Statistics; (2) SARS-CoV-2 tests (duplicate tests removed); (3) COVID-19 RT-PCR–positive disease in those tested from community and in-hospital testing available through Public Health England30; (4) any hospital attendance with confirmed COVID-19 infection, including any COVID-19 RT-PCR–positive disease via in-hospital testing as well as COVID-19–confirmed hospital admission data; (5) duration of hospitalization with confirmed COVID-19 (no admission vs <36 or ≥36 hours admission to hospital; previous studies33,34 estimate that 36 hours is the mean length of stay in pediatric admissions in the UK and longer admissions are categorized as prolonged); (6) mortality data via the Office for National Statistics; and (7) a diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) using ICD-10 diagnosis code U07.5. Outcomes were reported from January 24 to October 31, 2020, for hospital admissions or November 30, 2020, for test results.

Exposures

The main characteristic of interest was self- or parent-reported race, identified through primary care health records. Racial groups were recorded based on the 2011 Census of England and Wales in 4 broad categories (White, Asian, Black, and mixed or other).35

Explanatory variables with existing evidence of association with childhood COVID-19 outcomes were identified through primary care records. These variables include the following: (1) age at cohort entry (categorized as 0-<3 months, 3 months-1 year, 2-5 years, 6-10 years, 11-15 years, and 16-18 years); (2) sex (male or female); (3) level of deprivation assessed through the Townsend deprivation score,36 which is an area-level continuous score based on an individual’s postcode; factors that included unemployment, non–car ownership, non–home ownership, and household overcrowding, are measured for a given area of approximately 120 households, via the 2011 Census of England and Wales35 and combined to give a Townsend score for that area, with the first quintile representing the lowest deprivation level and the fifth quintile representing the highest deprivation level; (4) geographic region (10 regions across England); (5) household size (categorized into 2 people, 3-5 people, 6-9 people, or ≥10 people in a household), with single-occupant households reclassified as missing and imputed; and (6) only relevant comorbidities previously observed to be associated with severe childhood COVID-19 outcomes and with differing prevalence across racial or ethnic groups were included (asthma,37 type 1 diabetes,38 obesity,4,39 congenital heart disease,40 neurologic disorders [cerebral palsy and epilepsy],41 and sickle cell disease).42

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression was used to investigate the associations between race and each of the COVID-19 outcomes in 3 separate models. Model A consisted of unadjusted analyses. Model B adjusted for demographic factors only (age, sex, deprivation, household size, and geographic region). Model C adjusted for the aforementioned demographic factors and relevant comorbidities (asthma, type 1 diabetes, congenital heart disease, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and sickle cell disease). All models accounted for the correlation because of clustering of children within practices through a robust variance estimator.

Regression analyses for hospital contact and admission included the full cohort of children. Analyses for testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 were restricted to those tested, and analyses for hospitalization duration were restricted to those with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Multiple imputation with chained equations was used to replace missing data for household size (14% missing), race (30% missing), and Townsend deprivation score quintile (0.8% missing). Ten imputations were performed (eTable 12 in the Supplement). Imputation models included race, all explanatory variables, and the primary outcome variables; statistical models were developed on each of the 10 imputed data sets and the estimates pooled using the Rubin rules.

All analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, version 16 (StataCorp LLC).43 A 2-sided P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Study Population and Characteristics

The cohort included 2 576 353 children (mean [SD] age, 9.23 [5.24] years; 48.8% female). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the cohort. A total of 1 827 809 of the 2 576 353 children (70.9%) were school aged (>5 years). Race was recorded for 1 795 735 participants (69.7%) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). A total of 484 694 of the 2 576 353 patients (18.8 %) comprised individuals who identified as Asian, Black, and mixed or other racial categories, which is largely representative of the UK population.44 A total of 361 509 of the 2 576 353 children (14.0%) were classified into single-person households.

Table 1. Baseline and Clinical Characteristics of Children Registered With QResearch Practices Between January 24, 2020, and November 30, 2020a.

| Characteristic | Total population | No. of SARS-CoV-2 tests | Tested for SARS-CoV-2 per total population, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2 576 353 | 410 726 | 15.9 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 318 747 (51.2) | 213 157 (51.9) | 16.1 |

| Female | 1 257 606 (48.8) | 197 569 (48.1) | 15.7 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 9.23 (5.24) | 9.28 (5.41) | NA |

| Age categories | |||

| 0-3 mo | 61 116 (2.4) | 8348 (2.0) | 13.7 |

| 3-12 mo | 130 110 (5.1) | 23 984 (5.8) | 18.4 |

| 2-5 y | 557 318 (21.6) | 93 316 (22.7) | 16.7 |

| 6-10 y | 725 819 (28.2) | 106 440 (25.9) | 14.7 |

| 11-15 y | 707 095 (27.5) | 108 575 (26.4) | 15.4 |

| 16-18 y | 394 895 (15.3) | 70 063 (17.1) | 17.7 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 311 041 (50.9) | 223 701 (78.9) | 17.1 |

| Asian | 243 545 (9.5) | 33 213 (11.7) | 13.6 |

| Black | 93 620 (3.6) | 7727 (2.7) | 8.3 |

| Mixed or other | 147 529 (5.7) | 18 971 (6.7) | 12.9 |

| Not recorded | 780 618 (30.3) | 127 114 (30.9) | 16.3 |

| Townsend deprivation quintile | |||

| 1 (Least deprived) | 527 452 (20.5) | 95 949 (23.6) | 18.2 |

| 2 | 547 532 (21.3) | 96 475 (23.7) | 17.5 |

| 3 | 542 116 (21.0) | 88 858 (21.8) | 16.4 |

| 4 | 509 671 (19.8) | 74 096 (18.2) | 14.5 |

| 5 (Most deprived) | 429 060 (16.7) | 51 598 (12.7) | 12.0 |

| Not recorded | 20 522 (0.8) | 3750 (0.9) | 18.3 |

| Geographic region of England | |||

| East Midlands | 48 887 (1.9) | 7977 (1.9) | 16.3 |

| East of England | 98 280 (3.8) | 14 980 (3.7) | 15.2 |

| London | 669 444 (26.0) | 82 965 (20.2) | 12.4 |

| North East | 51 775 (2.0) | 10 087 (2.5) | 19.5 |

| North West | 473 994 (18.4) | 95 702 (23.3) | 20.2 |

| South Central | 341 774 (13.3) | 54 145 (13.2) | 15.8 |

| South East | 283 721 (11.0) | 33 246 (10.8) | 11.7 |

| South West | 242 585 (9.4) | 38 114 (9.3) | 15.7 |

| West Midlands | 284 207 (11.0) | 48 147 (11.7) | 16.9 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 81 686 (3.2) | 14 363 (3.5) | 17.6 |

| Household size (No. of people) | |||

| 2 | 383 616 (14.9) | 64 635 (15.7) | 16.8 |

| 3-5 | 1 549 068 (60.1) | 253 123 (61.6) | 16.3 |

| 6-9 | 246 764 (9.6) | 30 806 (7.5) | 12.5 |

| ≥10 | 35 396 (1.4) | 3950 (1.0) | 11.2 |

| Not recordedb | 361 509 (14.0) | 58 212 (14.2) | 16.1 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| No relevant comorbidities | 2 348 326 (91.1) | 362 649 (88.3) | 15.4 |

| Asthma | 183 089 (7.1) | 37 519 (9.1) | 20.5 |

| Diabetes (type 1) | 4916 (0.2) | 1166 (0.3) | 23.7 |

| Cerebral palsy | 3927 (0.2) | 1153 (0.3) | 29.4 |

| Epilepsy | 12 972 (0.5) | 3213 (0.8) | 24.8 |

| Congenital heart disease | 21 523 (0.8) | 4694 (1.1) | 21.8 |

| Sickle cell disease | 1600 (0.1) | 332 (0.1) | 20.8 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Data are presented as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Household size 1 (single occupant) was reclassified as not recorded.

Overall, 410 726 children (15.9%) underwent SARS-CoV-2 testing, with positive results in 26 322 (6.4%). During the study period, 1853 children (0.07%) in the cohort had a recorded hospital contact and 343 (0.01%) were admitted to the hospital (Table 2). Of those admitted, 184 of 343 (53.6%) remained in the hospital for less than 36 hours and 159 of 343 (46.4%) remained in the hospital for 36 hours or longer.

Table 2. COVID-19 Testing and Hospital Outcomes of Children Between January 24 and October 31 (for Hospital Data) and November 30, 2020 (for Testing Data)a.

| Outcome | Total population | Tested positive | Hospital contact | Hospital admission | ICU admission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <36 h | ≥36 h | Total admissions | |||||

| Total population | 2 576 353 | 26 322 (1.0) | 1853 (0.07) | 184 (0.007) | 159 (0.006) | 343 (0.01) | 73 (0.002) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1 318 747 | 12 959 (1.0) | 934 (0.07) | 109 (0.008) | 83 (0.006) | 192 (0.01) | 45 (0.003) |

| Female | 1 257 606 | 13 363 (1.1) | 919 (0.07) | 75 (0.006) | 76 (0.006) | 151 (0.01) | 28 (0.002) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 14 (9-17) | 13 (7-16) | 3 (1-12) | 8 (1-15) | 5 (1-13) | 4 (0-12) | |

| Age categories | |||||||

| 0-<3 mo | 61 116 | 330 (0.53) | 96 (0.15) | 35 (0.06) | 30 (0.05) | 65 (0.1) | 22 (0.03) |

| 3-12 mo | 130 110 | 580 (0.44) | 113 (0.09) | 36 (0.03) | 18 (0.01) | 54 (0.04) | 6 (0.005) |

| 2-5 y | 557 318 | 2334 (0.42) | 204 (0.04) | 39 (0.007) | 21 (0.004) | 60 (0.01) | 12 (0.002) |

| 6-10 y | 725 819 | 4750 (0.65) | 318 (0.04) | 22 (0.003) | 26 (0.004) | 48 (0.006) | 12 (0.002) |

| 11-15 y | 707 095 | 9000 (1.27) | 535 (0.08) | 28 (0.004) | 33 (0.005) | 61 (0.009) | 15 (0.002) |

| 16-18 y | 394 895 | 9328 (2.36) | 587 (0.15) | 24 (0.006) | 31 (0.008) | 55 (0.01) | 6 (0.002) |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 1 311 041 | 13 043 (1.0) | 839 (0.06) | 62 (0.004) | 63 (0.004) | 125 (0.009) | 24 (0.002) |

| Asian | 243 545 | 3576 (1.47) | 236 (0.09) | 24 (0.01) | 23 (0.009) | 47 (0.02) | 15 (0.006) |

| Black | 93 620 | 601 (0.64) | 67 (0.07) | 10 (0.01) | 10 (0.01) | 20 (0.02) | 5 (0.005) |

| Mixed/other | 147 529 | 1197 (0.81) | 108 (0.07) | 11 (0.007) | 19 (0.01) | 30 (0.02) | 6 (0.004) |

| Townsend deprivation quintile | |||||||

| 1 (Least deprived) | 527 452 | 6239 (1.0) | 433 (0.08) | 30 (0.005) | 17 (0.003) | 47 (0.009) | 7 (0.001) |

| 2 | 547 532 | 5762 (1.1) | 395 (0.07) | 31 (0.006) | 23 (0.004) | 54 (0.01) | 10 (0.002) |

| 3 | 542 116 | 5562 (1.0) | 408 (0.08) | 44 (0.008) | 29 (0.005) | 73 (0.01) | 17 (0.003) |

| 4 | 509 671 | 4916 (1.0) | 326 (0.06) | 38 (0.007) | 37 (0.007) | 75 (0.01) | 12 (0.002) |

| 5 (Most deprived) | 429 060 | 3694 (0.86) | 271 (0.06) | 41 (0.009) | 51 (0.01) | 92 (0.02) | 26 (0.006) |

| Household size (No. of people) | |||||||

| 2 | 383 616 | 3427 (0.90) | 257 (0.07) | 33 (0.009) | 27 (0.007) | 60 (0.02) | 9 (0.002) |

| 3-5 | 1 549 068 | 16 760 (1.12) | 1156 (0.07) | 93 (0.006) | 75 (0.005) | 168 (0.01) | 38 (0.002) |

| 6-9 | 246 764 | 2739 (1.83) | 160 (0.06) | 14 (0.006) | 25 (0.01) | 39 (0.02) | 6 (0.002) |

| ≥10 | 35 396 | 573 (1.61) | 42 (2.3) | <5b | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| No relevant comorbidities | 2 348 326 | 22 747 (1.0) | 1584 (0.07) | 288 (0.01) | 157 (0.007) | 131 (0.006) | 55 (0.002) |

| Asthma | 183 089 | 2962 (1.6) | 188 (0.1) | 15 (0.008) | 10 (0.005) | 25 (0.01) | <5 |

| Diabetes (type 1) | 4916 | 98 (2.0) | 16 (0.3) | <5 | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Cerebral palsy | 3927 | 57 (1.5) | 13 (0.3) | <5 | <5 | 7 (0.2) | 5 (0.1) |

| Epilepsy | 12 972 | 205 (1.6) | 35 (0.3) | 5 (0.04) | 7 (0.05) | 12 (0.09) | 5 (0.04) |

| Congenital heart disease | 21 523 | 244 (1.1) | 28 (0.1) | <5 | <5 | 7 (0.03) | 5 (0.02) |

| Sickle cell disease | 1600 | 9 (0.6) | <5 | <5 | <5 | <5 | <5 |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Data are presented as number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Values less than 5 were suppressed to maintain confidentiality.

A total of 73 of 343 patients (21.3%) were admitted to the ICU. Of these admitted patients, 22 (30.1%) were infants (0-<3 months of age), 45 (62.6%) were male, and 26 (36.1%) were from the most deprived level. Of 159 prolonged hospitals stays (≥36 hours), 50 (31.4%) were ICU admissions. There was only 1 recorded death during the study period (case fatality rate, 0.003%).

COVID-19 Testing

Testing patterns across different races varied (Table 1; eTable 1 in the Supplement). White children had the highest percentage of SARS-CoV-2 tests (223 701/1 311 041 [17.1%]), whereas children of all other races had lower percentages (Asian: 33 213/243 545 [13.6%]; mixed or other: 18 971/147 529 [12.9%]; and Black: 7727/93 620 [8.3%]). In children who were tested, those from Asian (3576/33 213 [10.8%]), Black (601/7727 [7.8%]), and mixed or other (1197/18 971 [6.3%]) backgrounds had higher proportions of positive test results, whereas White children had lower proportions (13 043/223 701 [5.8%]) (Table 2).

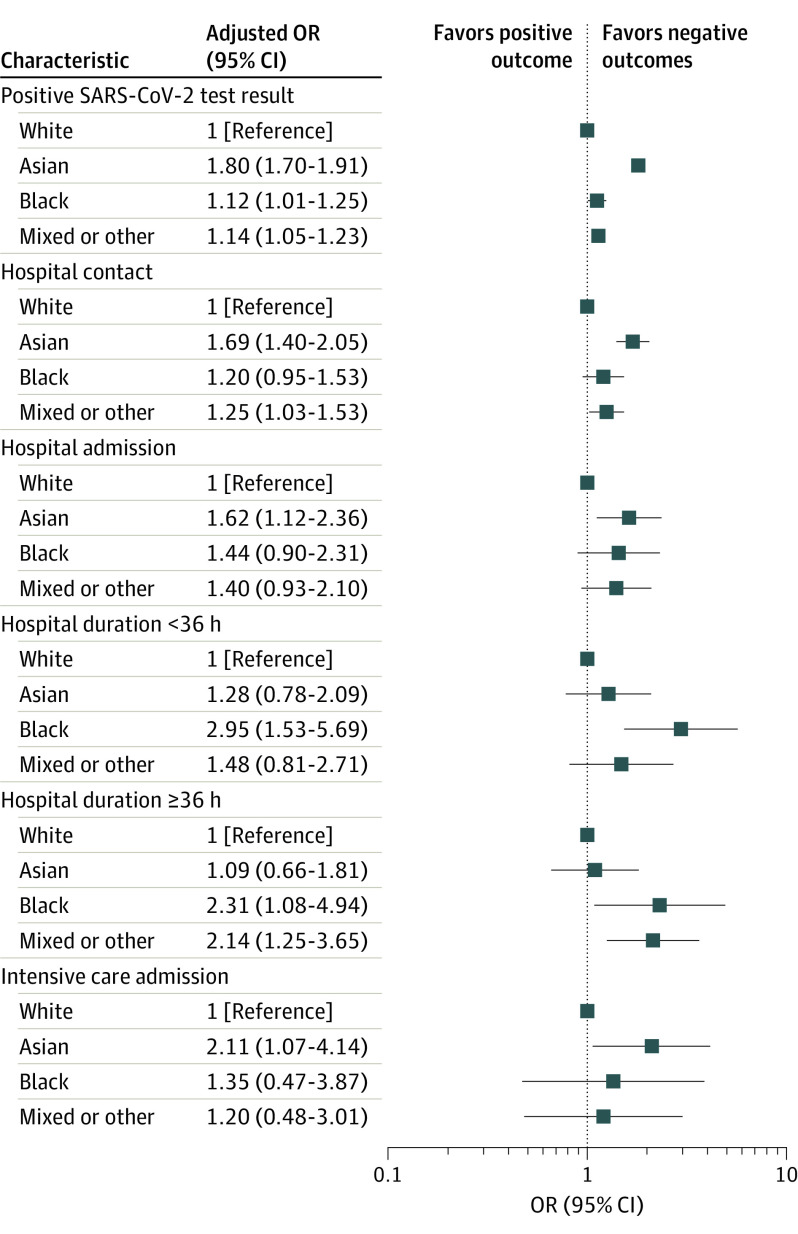

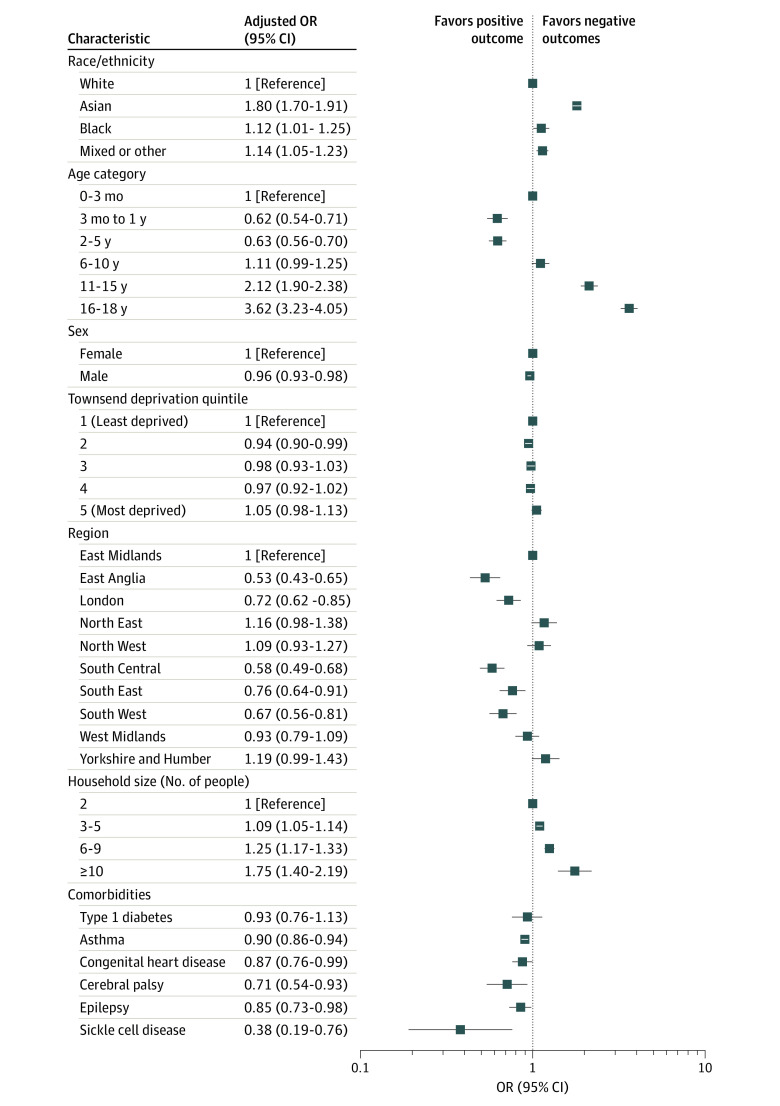

In maximally adjusted estimates, children of Asian (adjusted OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.70-1.91; P < .001), Black (adjusted OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01-1.25; P = .04), and mixed or other (adjusted OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.05-1.23; P = .002) backgrounds had significantly higher odds of positive test results compared with White children (Figure 1; eFigure 1 and eTables 3 and 8 in the Supplement). Older children (16-18 years of age) were also more likely to have a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 compared with infants (0-3 months of age) (adjusted OR, 3.62; 95% CI, 3.23-4.05; P < .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Race and Outcomes of Interest.

Outcomes of interest included SARS-CoV-2 testing, hospital contact (admission or attendance), hospital admission, hospitalization duration, and intensive care admission. Adjustments were made for demographic characteristics (age, sex, deprivation level, region, and household size) and all relevant comorbidities (asthma, type 1 diabetes, cerebral palsy, congenital heart disease, epilepsy, and sickle cell disease). OR indicates odds ratio.

Figure 2. Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Race and Having a SARS-CoV-2 Positive Test Result.

Adjustments were made for demographic characteristics (age, sex, deprivation level, region, and household size) and relevant comorbidities (asthma, type 1 diabetes, congenital heart disease, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and sickle cell disease). OR indicates odds ratio.

COVID-19 Hospital Contact and Admission

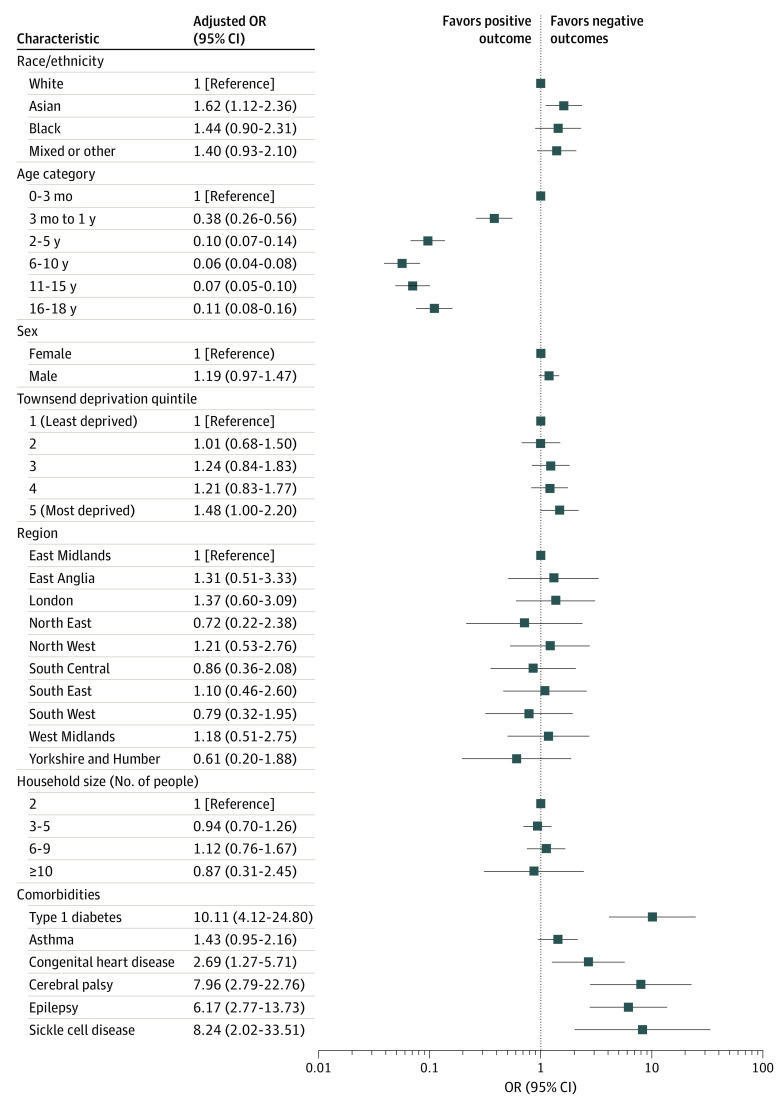

Race was significantly associated with hospital admission (Figure 1 and Figure 3; eFigure 3 and eTables 5 and 10 in the Supplement) and any hospital contact (Figure 1; eFigure 2 and eTables 4 and 9 in the Supplement). In maximally adjusted estimates, children of Asian (adjusted OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.40-2.05; P < .001) and mixed or other (adjusted OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.03-1.53; P = .03) backgrounds had significantly higher ORs for hospital contact. Asian children were also more likely to be admitted to the hospital for confirmed COVID-19 (adjusted OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.12-2.36; P = .01) compared with White children, whereas the ORs for Black children (adjusted OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.90-2.31) and children of mixed or other races (adjusted OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 0.93-2.10) were comparable.

Figure 3. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Race and Hospital Admission.

Adjustments were made for demographic characteristics (age, sex, deprivation level, region, and household size) and any relevant comorbidity (asthma, type 1 diabetes, congenital heart disease, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and sickle cell disease). OR indicates odds ratio.

Hospitalization duration also varied across races (Figure 1; eFigure 4 and eTable 6 in the Supplement). In adjusted estimates, Black children (adjusted OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.08-4.94; P = .03) and children of mixed or other races (adjusted OR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.25-3.65; P = .006) had significantly more hospitalizations that were 36 hours or longer compared with White children. Because of small numbers of children with comorbidities, adjusted estimates for hospitalization duration included only demographic variables.

COVID-19 ICU Admissions

Race was also associated with ICU admissions (Figure 1; eFigure 5 and eTables 7 and 11 in the Supplement). In maximally adjusted estimates, Asian children had a significantly higher odds ratio for COVID-19 ICU admissions (adjusted OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.07-4.14; P = .03) compared with White children. The OR for COVID-19 ICU admission in Black children (adjusted OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.47-3.87) and children of mixed or other races (adjusted OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.48-3.01) was not significantly different compared with White children.

Discussion

This cohort study used a nationally representative cohort of 2 576 353 children (0-18 years of age) to investigate the association between race and pediatric COVID-19 outcomes in the UK. Results of this study indicate that race-specific disparities in SARS-CoV-2 testing and COVID-19 hospital outcomes seen in adults also exist among children, after accounting for several clinical and sociodemographic factors thought to play a role in the disease. First, unequal SARS-CoV-2 testing across racial minority children was identified, with the highest proportion of tests seen in White children. Second, in children who received a test, racial minority children were more likely to test positive compared with White children. Third, Asian children were significantly more likely to have COVID-19 hospital and ICU admissions compared with White children. Fourth, although Black children and children of mixed or other races had comparable risks of hospital admission, when admitted, they were more likely to remain in the hospital for 36 hours or longer compared with White children.

Differing testing rates across racial/ethnic minorities during the pandemic have previously been reported in studies45,46 that focused on adults. This disparity has also been observed more generally in other health contexts in adults, such as cancer screening,47 HIV screening,48 and vaccination uptake.49,50 Structural discrimination, distrust of health care establishments, and the wider social determinants of health are all thought to contribute to this observed inequity.51 The findings of this study support similar pediatric reports from the US5 and suggest that this disparity is not limited to adults. These findings highlight the need for a more international focus on prioritization of testing access and uptake among children from different race. Testing remains particularly important for children, while waiting for vaccination programs to roll out to younger age groups.

The finding that racial minority children are more likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared with White children, after accounting for key sociodemographic and clinical factors, builds on a previous report5 from the US-based pediatric cohort study and is in keeping with several other studies52,53 focused on adult racial/ethnic minorities. A recent meta-analysis17 of 50 studies in adults from the US and the UK found that racial/ethnic minorities were at higher risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection. The underlying reasons for these findings are likely to be multifactorial and complex. Higher infection rates observed among adult racial minorities have largely been attributed to sociodemographic factors that we were unable to account for in our study.17,45 These factors include living in multigenerational households and being part of families with members who are considered essential workers.42

This study further found race-specific differences in hospital outcomes in children with COVID-19. Compared with White children, Asian children were more likely to have COVID-19 hospital and ICU admissions, whereas Black children and children of mixed or other races were more likely to remain in the hospital for longer than or equal to 36 hours. These results suggest that racial minority children may have a more severe course of COVID-19. These findings are in line with studies4,54,55 based on cohorts of hospitalized children with COVID-19: (1) a UK-based descriptive study4 that reported an increased risk of COVID-19 critical care admissions in children of Black backgrounds and (2) US-based studies54,55 on MIS-C that identified a higher risk in children of Black race in MIS-C–related hospitalizations. The underlying mechanisms for these findings are likely to be complex. The lower percentage of tests seen in racial minority children may result in the biased selection of more severe COVID-19 cases and underestimate the mild and asymptomatic cases in these groups. These study findings do not allow further extrapolation of underlying etiologic mechanisms. More granular assessment of individual ethnicities within Asian and Black groups, as well as other ethnicities, such as Hispanic, are required before any further interpretation.

This study also identified other potential factors associated with severe childhood COVID-19 outcomes, such as young age, preexisting comorbidities, and higher deprivation levels. Infants (0-3 months of age) were more likely to have hospital admissions, longer hospital stays, and more ICU admissions. Higher ORs of these outcomes were also observed in children with preexisting comorbidities, specifically neurologic disorders (cerebral palsy and epilepsy), type 1 diabetes, congenital heart disease, and sickle cell disease. This finding could be a result of the lower admission thresholds for observation in infants and children with preexisting comorbidities but could also indicate a more severe disease course. The findings of this study are in line with results of several other pediatric cohort studies4,5,11 that have explored COVID-19. This study also observed a higher proportion of ICU admissions in male patients, which has been reported in a previous pediatric, multicohort study11 in Europe and is an established risk factor for poor outcomes in adults with COVID-19.17 Male sex has previously been reported to be associated with more severe outcomes in several other childhood infectious diseases, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus,56 although the mechanisms underlying this difference is unclear.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths. Overall, the main strengths include the use of a large, nationally representative sample covering approximately 20% of the population of England. The population-based approach overcomes the potential selection bias observed in previous studies,54,57 which have been restricted to hospital admissions, and reduces the risk of collider bias. Detailed consideration and inclusion of clinical and sociodemographic confounders in the analyses provide a rigorous investigation of the association between race and pediatric COVID-19 outcomes.

This study also has some important limitations. First, the numbers of ICU admissions and deaths were small. Although the findings provide crucial insights into the association of race with COVID-19 outcomes, further studies are required to explore the most severe cases (ie, ICU admissions and mortality) and longer-term outcomes, such as long-term COVID-19. Second, because of the absence of a code for MIS-C in the UK, it was not possible to separately investigate the association between race and MIS-C. Third, although obesity has been associated with more severe COVID-19 outcomes in children as well as adults and has different prevalence rates across racial/ethnic minority groups in the UK,5,39,58 body mass index was not consistently recorded across the data set (only 15.8% of cohort) and therefore could not be included in analyses. This inconsistency is attributable to childhood weight measurements not routinely being conducted in primary care. Fourth, schools were open for part of the study period (September to November 2020), which may impact test rates, although schooling is compulsory for all children in the UK. Fifth, 14.0% of the study cohort was misclassified into single-occupant households, which is likely because of family members registering at different nearby family practices. Because only 2.1% of the 16- to 24-year-olds in the UK are reported to live alone,59 we reclassified single-occupant households as missing and imputed it in our analyses. Sixth, because this study is an observational study based on linked data sets, there is the possibility of selection bias from missing data, information bias from misclassification of test results (particularly with limited community testing at the beginning of the pandemic, which may underestimate the numbers of patients with COVID-19 disease), and residual confounding from unaccounted confounders, such as parental occupation.

Conclusions

After accounting for important sociodemographic and clinical factors that are associated with COVID-19 disease, this population-based cohort study provides, to our knowledge, the most evidence to date of race-specific disparities across SARS-CoV-2 testing and COVID-19 hospitalizations in children in the UK. Disparities in testing, infection rates, and hospitalization linked to racial minority children have important implications for families, practitioners, and policymakers internationally. Raising awareness of race/ethnic group–specific patterns of presentation to hospital and potential differences in disease course may support families in their decisions to seek medical advice early and aid practitioners in tailoring their inpatient and ambulatory management. This study reinforces the continued need for race/ethnicity-tailored focus on health system performance and targeted public health interventions in children, not only during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic but also in the event of future public health threats.

eTable 1. Characteristics and Outcomes of Children, by Race/Ethnicity

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Study Population, Population With Ethnicity Recorded and Population Without Ethnicity Recorded

eTable 3. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Testing Positive for SARS-COV-2

eTable 4. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Any Hospital Contact

eTable 5. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eTable 6. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and I) Hospitalization <36 Hours and II) Hospitalization Duration ≥36 Hours

eTable 7. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission

eTable 8. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Testing Positive for SARS-COV-2

eTable 9. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Any COVID-19 Hospital Contact

eTable 10. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eTable 11. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission

eTable 12. Study Population According to Race/Ethnicity Before and After Imputation

eFigure 1a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Having a Positive SARS-COV-2 Test (If Tested)

eFigure 1b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Having a Positive SARS-COV-2 Test (If Tested)

eFigure 2a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Contact (Any Admission or Attendance to Hospital)

eFigure 2b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Contact (Any Admission or Attendance to Hospital)

eFigure 2c. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Contact (Admission or Attendance)

eFigure 3a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eFigure 3b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eFigure 4a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and I) Hospitalization Duration <36 Hours and II) Hospitalization Duration ≥36 Hours

eFigure 4b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and I) Hospitalization Duration <36 Hours and Ii) Hospitalization Duration ≥36 Hours

eFigure 5a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission.

eFigure 5b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission

eFigure 5c. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC COVID Data Tracker. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographics

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. COVID-19 in children and the role of school settings in COVID-19 transmission: first update. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/children-and-school-settings-covid-19-transmission

- 3.Kim L, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, et al. ; COVID-NET Surveillance Team . Hospitalization rates and characteristics of children aged <18 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-July 25, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1081-1088. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle L, et al. ; ISARIC4C Investigators . Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m3249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey LC, Razzaghi H, Burrows EK, et al. Assessment of 135794 pediatric patients tested for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 across the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(2):176-184. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parri N, Lenge M, Buonsenso D; Coronavirus Infection in Pediatric Emergency Departments (CONFIDENCE) Research Group . Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):187-190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garazzino S, Montagnani C, Donà D, et al. ; Italian SITIP-SIP Pediatric Infection Study Group; Italian SITIP-SIP SARS-CoV-2 Paediatric Infection Study Group . Multicentre Italian study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents, preliminary data as of 10 April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(18):2000600. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rankin DA, Talj R, Howard LM, Halasa NB. Epidemiologic trends and characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infections among children in the United States. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021;33(1):114-121. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loomba RS, Villarreal EG, Farias JS, Bronicki RA, Flores S. Pediatric intensive care unit admissions for COVID-19: insights using state-level data. Int J Pediatr. 2020;2020:9680905. doi: 10.1155/2020/9680905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Götzinger F, Santiago-García B, Noguera-Julián A, et al. ; ptbnet COVID-19 Study Group . COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(9):653-661. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30177-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludvigsson JF, Engerstrom L, Nordenhall C, Larsson E. Open schools, Covid-19, and child and teacher morbidity in Sweden. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):669-671. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2026670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430-436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by ethnic group, England and Wales. Published 2020. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronavirusrelateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/2march2020to10april2020

- 15.Hippisley-Cox J, Young D, Coupland C, et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 disease with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: cohort study including 8.3 million people. Heart. 2020;106(19):1503-1511. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clift AK, Coupland CAC, Keogh RH, et al. Living risk prediction algorithm (QCOVID) for risk of hospital admission and mortality from coronavirus 19 in adults: national derivation and validation cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371:m3731. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sze S, Pan D, Nevill CR, et al. Ethnicity and clinical outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29:100630. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harman K, Verma A, Cook J, et al. Ethnicity and COVID-19 in children with comorbidities. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(7):e24-e25. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30167-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.QResearch . QResearch. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.qresearch.org/

- 20.EMIS Health. Products. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.emishealth.com/products/emis-web/

- 21.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Robson J, Brindle P. Derivation, validation, and evaluation of a new QRISK model to estimate lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease: cohort study using QResearch database. BMJ. 2010;341:c6624. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2020;371:m3873. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clift AK, Coupland CAC, Keogh RH, Hemingway H, Hippisley-Cox J. COVID-19 mortality risk in Down syndrome: results from a cohort study of 8 million adults. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):572-576. doi: 10.7326/M20-4986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jack RH, Hollis C, Coupland C, et al. Incidence and prevalence of primary care antidepressant prescribing in children and young people in England, 1998-2017: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(7):e1003215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langan SM, Schmidt SA, Wing K, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ. 2018;363:k3532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NHS Digital . About NHS Digital. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/about-nhs-digital

- 28.Office for National Statistics. Births, deaths, and marriages. Accessed December 28, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages

- 29.UK Department of Health and Social Care. Sources of COVID-19 surveillance systems. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-covid-19-surveillance-reports/sources-of-covid-19-systems

- 30.UK Department of Health and Social Care. COVID-19 testing data: methodology note. Accessed December 28, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-testing-data-methodology/covid-19-testing-data-methodology-note

- 31.University of Nottingham. Accessed March 7, 2021. http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/3153/

- 32.NHS England : COVID-19 hospital activity. Accessed December 28, 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/12/Publication-definitions-1.pdf

- 33.Heys M, Rajan M, Blair M. Length of paediatric inpatient stay, socio-economic status and hospital configuration: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):274. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2171-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nuffield Trust and The Health Foundation . Quality Watch Report. Focus on: emergency hospital care for children and young people. Accessed December 27, 2020. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/qualitywatch

- 35.Office for National Statistics. 2011 Census. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/2011censusanalysisethnicityandreligionofthenonukbornpopulationinenglandandwales/2015-06-18

- 36.Townsend P, Davidson N. Inequalities in Health: The Black Report. Dept of Health and Social Security; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Netuveli G, Hurwitz B, Levy M, et al. Ethnic variations in UK asthma frequency, morbidity, and health-service use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):312-317. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17785-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oldroyd J, Banerjee M, Heald A, Cruickshank K. Diabetes and ethnic minorities. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(958):486-490. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Public Health England. Differences in child obesity by ethnic group. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/differences-in-child-obesity-by-ethnic-group/differences-in-child-obesity-by-ethnic-group#references

- 40.Knowles RL, Ridout D, Crowe S, et al. Ethnic and socioeconomic variation in incidence of congenital heart defects. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(6):496-502. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinha G, Corry P, Subesinghe D, Wild J, Levene MI. Prevalence and type of cerebral palsy in a British ethnic community: the role of consanguinity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39(4):259-262. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hickman M, Modell B, Greengross P, et al. Mapping the prevalence of sickle cell and beta thalassaemia in England: estimating and validating ethnic-specific rates. Br J Haematol. 1999;104(4):860-867. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. Release 16. StataCorp; 2019.

- 44.Office for National Statistics . UK Population by Ethnicity. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/latest

- 45.Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37-44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rentsch CT, Kidwai-Khan F, Tate JP, et al. Patterns of COVID-19 testing and mortality by race and ethnicity among United States veterans: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marlow LA, Waller J, Wardle J. Barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women: a qualitative study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(4):248-254. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alvarez-del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, et al. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(6):1039-1045. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):964-973. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Royal Society for Public Health : New poll finds BAME groups less likely to want COVID vaccine. Accessed December 27, 2020. https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-us/news/new-poll-finds-bame-groups-less-likely-to-want-covid-vaccine.html

- 51.Dodds C, Fakoya I. Covid-19: ensuring equality of access to testing for ethnic minorities. BMJ. 2020;369:m2122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathur R, Rentsch CT, Morton CE, et al. Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission, and death in 17 million adults in England: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet. 2021;397(10286):1711-1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00634-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rozenfeld Y, Beam J, Maier H, et al. A model of disparities: risk factors associated with COVID-19 infection. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01242-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee EH, Kepler KL, Geevarughese A, et al. Race/Ethnicity among children with COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2030280. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Godfred-Cato S, Bryant B, Leung J, et al. ; California MIS-C Response Team . COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: United States, March-July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1074-1080. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwane MK, Edwards KM, Szilagyi PG, et al. ; New Vaccine Surveillance Network . Population-based surveillance for hospitalizations associated with respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, and parainfluenza viruses among young children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1758-1764. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle L, et al. Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m3249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seidu S, Gillies C, Zaccardi F, et al. The impact of obesity on severe disease and mortality in people with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2020;e00176. doi: 10.1002/edm2.176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Families and Households Dataset . Published 2020. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/datasets/familiesandhouseholdsfamiliesandhouseholds

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Characteristics and Outcomes of Children, by Race/Ethnicity

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Study Population, Population With Ethnicity Recorded and Population Without Ethnicity Recorded

eTable 3. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Testing Positive for SARS-COV-2

eTable 4. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Any Hospital Contact

eTable 5. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eTable 6. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and I) Hospitalization <36 Hours and II) Hospitalization Duration ≥36 Hours

eTable 7. Comparison of Regression Estimates for Complete Case Analysis (CCA) and Multiple Imputation (MI) Models for Maximally Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission

eTable 8. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Testing Positive for SARS-COV-2

eTable 9. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Any COVID-19 Hospital Contact

eTable 10. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eTable 11. Comparison of Maximally Adjusted Regression Estimates for Logistic Regression and Relative Risk Regression in the Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission

eTable 12. Study Population According to Race/Ethnicity Before and After Imputation

eFigure 1a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Having a Positive SARS-COV-2 Test (If Tested)

eFigure 1b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Having a Positive SARS-COV-2 Test (If Tested)

eFigure 2a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Contact (Any Admission or Attendance to Hospital)

eFigure 2b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Contact (Any Admission or Attendance to Hospital)

eFigure 2c. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Contact (Admission or Attendance)

eFigure 3a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eFigure 3b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Hospital Admission

eFigure 4a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and I) Hospitalization Duration <36 Hours and II) Hospitalization Duration ≥36 Hours

eFigure 4b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and I) Hospitalization Duration <36 Hours and Ii) Hospitalization Duration ≥36 Hours

eFigure 5a. Univariate Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission.

eFigure 5b. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission

eFigure 5c. Adjusted Regression Analysis Exploring the Association Between Ethnicity and Intensive Care Admission