Abstract

Plasmodium falciparum causes the deadliest form of malaria. Adequate redox control is crucial for this protozoan parasite to overcome oxidative and nitrosative challenges, thus enabling its survival. Sulfenylation is an oxidative post-translational modification, which acts as a molecular on/off switch, regulating protein activity. To obtain a better understanding of which proteins are redox regulated in malaria parasites, we established an optimized affinity capture protocol coupled with mass spectrometry analysis for identification of in vivo sulfenylated proteins. The non-dimedone based probe BCN-Bio1 shows reaction rates over 100-times that of commonly used dimedone-based probes, allowing for a rapid trapping of sulfenylated proteins. Mass spectrometry analysis of BCN-Bio1 labeled proteins revealed the first insight into the Plasmodium falciparum trophozoite sulfenylome, identifying 102 proteins containing 152 sulfenylation sites. Comparison with Plasmodium proteins modified by S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosation showed a high overlap, suggesting a common core of proteins undergoing redox regulation by multiple mechanisms. Furthermore, parasite proteins which were identified as targets for sulfenylation were also identified as being sulfenylated in other organisms, especially proteins of the glycolytic cycle. This study suggests that a number of Plasmodium proteins are subject to redox regulation and it provides a basis for further investigations into the exact structural and biochemical basis of regulation, and a deeper understanding of cross-talk between post-translational modifications.

Keywords: Sulfenylation, 9-hydroxymethylbicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne (BCN-Bio1), malaria, redox proteomics, cysteine modification, post-translational modification

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Malaria is caused by apicomplexan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. 5 different human pathogenic species are known, of which Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum) causes the deadliest form [1]. The parasite has a complex life cycle and protein expression patterns change dramatically with each stage; 20-33% of all proteins are stage specific [2]. At the same time, the parasite is subjected to different sources of nitrosative and oxidative challenges imposed by its mosquito vector Anopheles, its human host, and its own high metabolic rate [3]. To overcome these challenges, Plasmodium has developed a multifarious antioxidant system mainly based on the NADPH-dependent thioredoxin and glutathione systems [4,5]. Furthermore, the parasite possesses 5 peroxiredoxins [6,7]. Thus, despite lacking the classical mammalian antioxidant and redox regulating enzymes such as catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and sulfiredoxin, the parasite manages to exert control over its intracellular redox state [8].

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) of proteins are an important aspect of cellular regulation, allowing adaptation to changing environmental conditions through increasing proteome’s complexity and diversity. A number of Plasmodium PTMs have previously been investigated, revealing involvement in many crucial pathways (reviewed in [9]). These studies identified a high susceptibility of Plasmodium proteins to phosphorylation (30% of all proteins) [10], lysine acetylation (14%) [11], and ubiquitination (5%) [12]. Cysteine residues are particularly susceptible amino acids for PTM, and contribute to redox signaling [13]. Previous studies focusing on cysteine PTMs in P. falciparum investigated interaction partners of thioredoxin, glutaredoxin, and plasmoredoxin and identified several proteins which seem to be particularly prone to redox PTMs [14]. Glutathionylation and nitrosation pull-down experiments identified 491 and 317 targets, respectively [15,16]. There was a high overlap in the proteins identified in these studies, demonstrating the significance of redox regulation and the particular susceptibility to oxidation of proteins such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (PfGAPDH), which is involved in the central carbon metabolism of cells. Other redox PTMs have not been studied in detail in the Plasmodium system, and in this current study we remedy this by identifying the Plasmodium sulfenylome.

Sulfenic acid (-SOH), as an intermediate for several other PTMs, plays a crucial role in signal transduction and transcriptional regulation. Both reversible and what currently are thought to be irreversible oxidative modifications at cysteine sites (e.g., oxidation to sulfinic or sulfonic acids with some exceptions) [17,18] regulate protein activity through multiple mechanisms, whereas irreversible oxidation targeting a broader range of protein amino acids and nucleotides is associated with failure of protective mechanisms and thus oxidative imbalance [19,20]. Sulfenic acids represent an intermediate en route to other oxidation states. They serve as a regulator of several transcription factors, a sensor of oxidative stress, and a chemical species relevant in redox signaling [21,22]. Their transient nature is due to their metastable and highly reactive functional groups. Due to the formal oxidation state 0 of its sulfur atom, electrophilic as well as nucleophilic chemical activity can be exhibited [23]. Certain proteins, such as peroxidases and peroxiredoxins, belonging to the cell’s enzymatic reducing system, form -SOH intermediates during their catalytic cycle [24]. Prokaryotes such as Escherichia coli show similar sulfenylation mechanisms, emphasizing the importance of this transient modification [25].

1,3-dicarbonyl reagents, such as 5,5-dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexadione (dimedone), have been conventionally used to trap protein sulfenic acids [26]. Over the last decades, various derivatives linked to fluorescent or affinity-based probes have been developed, enabling enrichment and visualization of sulfenylated proteins (reviewed in [19]). Nevertheless, trapping this often-unstable modification requires reagents with faster kinetics such as that achieved with several more recently developed compounds [27,28]. Amongst these, the biotin-linked strained bicyclononyne BCN-Bio1 shows reaction rates with protein sulfenic acids over 100-fold higher than dimedone-based derivatives and was therefore selected for the studies included here [28].

We performed labeling of parasite lysates with BCN-Bio1 followed by pulldown of labeled sulfenylated proteins and MS/MS analysis to provide insight into the Plasmodium falciparum trophozoite sulfenylome. We identified 102 sulfenylated proteins and 152 sulfenylation sites, partially overlapping with previously identified redox-regulated proteins. As sulfenic acids are common intermediates in a broad range of protein redox modifications, their identification is a crucial step in further understanding the parasite’s redox metabolism and its role in regulation of cellular processes.

2. Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used were of the highest available purity and were obtained from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany), Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany), BioRad (Munich, Germany), Fluka (Steinheim, Germany), or Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). RPMI 1640 medium and Albumax were from Gibco (Paisley, United Kingdom), gentamycin from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany). BCN-Bio1 was synthesized as previously described and is available from Xoder Technologies, LLC (Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA) [28]. N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) was purchased from Fluka (Steinheim, Germany), bovine catalase from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany), high capacity streptavidin agarose from Invitrogen (California, USA), anti-biotin (33):sc-101339 from Santa Cruz (Texas, USA), and anti-mouse antibody from Dianova (Hamburg, Germany).

Cultivation of Plasmodium falciparum

Intraerythrocytic stages of the chloroquine sensitive strain 3D7 were maintained in continuous culture according to Trager and Jensen with slight modifications [29]). RPMI 1640 medium was completed with 0.5% lipid-rich bovine serum albumin (Albumax), 9 mM (0.16%) glucose, 0.2 mM hypoxanthine, and 22 μg/mL gentamycin. Parasites were grown in red blood cells (A+) at 3.3% hematocrit with a parasitemia between 1 to 10%. Incubations were performed at 37 °C in 3% O2, 3% CO2, and 94% N2. Synchronization to ring stages occurred through treatment with 5% (w/v) sorbitol [30]. Trophozoite stage infected erythrocytes with a parasitemia of 8-10% were harvested by lysing red blood cells for 10 min at 37 °C in a 20-fold volume of saponin lysis buffer (7 mM K2HPO4, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 11 mM NaHCO3, 58 mM KCl, 56 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 14 mM glucose, and 0.02% saponin, pH 7.4). Saponin lysis was repeated twice before three washings with PBS. 360 mL cultured cells were harvested to get one pellet. Pellets were stored until use at −80 °C.

Pull-down of sulfenylated proteins using BCN-Bio1

The previously described sulfenylation pull-down protocol [31,32] was optimized for Plasmodium. A parasite pellet was lysed in degassed mRIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 25 mM NaF, 10 μM ZnCl2, 50 mM HEPES, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton-X-100, pH 7.5) freshly supplemented with 200 U/mL bovine liver catalase, 20 mM NEM, complete protease inhibitor, and 250 μM BCN-Bio1. Cells were disrupted with 4 freezing-thawing cycles. The lysate was centrifuged at 100,000 x g for 30 min at 4 °C to obtain a clear supernatant. Ice cold acetone was added in a 5-fold volume and protein precipitation was carried out for 1 h at −20 °C. Upon 10 min centrifugation at 11,000 x g at 4 °C proteins were pelleted, and supernatant was discarded. After complete acetone evaporation, the pellet was resuspended in 700 μL PBS/2% SDS. Protein concentration was determined using a NanoDrop™ 2000. Sample concentration was calculated according to Lambert-Beer’s law using the software’s extinction coefficient for protein solutions.

To enrich biotinylated proteins, high capacity streptavidin agarose beads with a binding capacity of 10 mg/mL were used. Prior to incubation with the proteins, beads were washed 3x with 4 bed volumes of PBS/0.1% SDS. In between the washing steps, beads were separated from supernatant by 1 min centrifugation at 11,000 x g at room temperature (RT). Overnight incubation was carried out on a rotator at 4 °C, after diluting the sample 1:2 with PBS. The following day beads were spun down for 1 min at 11,000 x g at RT, and the supernatant containing unbound proteins removed and collected. In order to remove nonspecifically bound proteins, beads were washed with 4-fold bed volume of PBS (30 min) followed by 2 M urea, 1 M NaCl, 0.1% SDS with 10 mM DTT, all in PBS and at RT. One final washing step was then carried out in PBS. In between, beads were spun down for 1 min at 11,000 x g, and supernatant was removed and collected. Elution was conducted by boiling the beads at 95 °C for 10 min in 100 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 8.0. To ensure complete removal of bound proteins, elution was performed three times. Protein concentrations of the eluates and wash steps were determined as described above. Western blot analysis confirmed successful performance prior to mass spectrometry analysis. Each of the 3 biological replicates was split into 2 fractions to give technical replicates in mass spectrometry analysis. Eluates were then stored at −20 °C until further processed for mass spectrometry analysis.

Immunodetection

To confirm labeling and washing efficiency of the performed pull-down, immunodetection using α-biotin antibody was performed. Briefly, 25 μL of protein sample with sample buffer containing DTT was denaturated for 5 min at 95 °C. Following 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Blocking was carried out for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline 0,05% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBST) with constant agitation. To visualize BCN-Bio1 tagged proteins, the membrane was incubated for 1 h at RT with anti-biotin antibody, diluted 1:500 in 5% non-fat milk in TBST, and for 1 h at RT with anti-mouse antibody-HRP, 1:10,000 in 5% non-fat milk in TBST. In between incubations, the membrane was washed with TBST 3x for 8 minutes. The membrane was developed with luminol and 0.0011% coumaric acid.

Sample preparation for mass spectrometry analysis

Eluates were sent on dry ice to the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, California. Samples were thawed and 125 μL were removed. Urea (60.06 mg) was added, and after urea was dissolved, 6.25 μL of 100 mM TCEP was added. Samples were shaken at RT for 30 min. Iodoacetamide (IAA, 6 μL of 250 mM) was added and the samples were covered in aluminum foil and shaken at RT for 30 min. EndoLysC (Wako, 1 μg) was added and the reactions were shaken at 37 °C for 4 hours. Samples were diluted 4x with 100 mM Tris and 1 μg trypsin was added. Samples were shaken overnight at 37 °C and stored in the freezer.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Samples were thawed, acidified with 7 μL of formic acid, shaken and spun at highest speed for 15 min. Samples were transferred to a new tube. Each sample (25 μg) was pressure loaded onto a 250-μm inside diameter (i.d.) fused silica microcapillary column (Polymicro Technologies) that was packed with 2.0 cm of Partishpere strong cation exchange resin (Whatman) followed by 2.0 cm of 10 cm Aqua C18 resin (Phenomenex). The column was washed for 30 min with 5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (Buffer A).

A 100 μm i.d. capillary with a 5 μm pulled tip packed with 15 cm of 3 μm Aqua C18 material (Phenomenex) was attached via a union, and the entire split-column was placed in line with an Agilent 1100 quaternary high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and analyzed using a 9-step separation. The buffer solutions used for separation were: 5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (Buffer A); 80% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (Buffer B); and 500 mM ammonium acetate/5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (Buffer C). Step 1 consisted of a 90 min gradient from 0% to 100% buffer B. Steps 2–9 had the following profile: 10 min of X% buffer C, a 15 min gradient from 0% to 5% buffer B, and a 95 min gradient from 15% to 100% buffer B. The 10 min buffer C percentages (X) were: 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, and 100%, respectively, for the 9-step analysis. As peptides eluted from the microcapillary column, they were electrosprayed directly into an Orbitrap Velos Pro mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) with the application of a distal 2.4 kV spray voltage. A cycle of one full-scan mass spectrum (400–1800 m/z) followed by 15 data-dependent tandem mass spectrometry spectra at a 35% normalized collision energy was repeated continuously throughout each step of the multidimensional separation. The application of mass spectrometer scan functions and HPLC solvent gradients were controlled by the XCalibur 2.2 SP1 data system.

Mass spectrometry data analysis

Collected tandem mass spectra were analyzed with Integrated Proteomics Pipeline (IP2; Integrated Proteomics Applications, Inc., San Diego, CA. http://www.integratedproteomics.com) using ProLuCID [33] and DTASelect 2.0 [34,35]. Using RawExtract 1.9.9 (http://fields.scripps.edu/downloads.php) [36] spectrum raw files were extracted into MS1 and MS2 files prior to searching them against the PlasmoDB database (release date 03-30-2015). In order to estimate peptide probabilities and false discovery rates, a decoy database consisting of the reversed sequence of all proteins appended to the target database was used. As human proteins may be present in the sample, a human database was included as well. A peptide confidence of 99.9% was set as the minimum threshold, and only peptides with a precursor delta mass less than 20 ppm were accepted, including only peptides with a minimum peptide length of 6 amino acids. The search space included all fully and half-tryptic peptide candidates that fell within the mass tolerance window with maximal 3 missed internal cleavage sites. Following modifications on cysteine were taken into account: +392.1759 (BCN-Bio1 bound to sulfenic acid, see figure 2B), and +141.04261 (NEM bound to sulfenic acid [31]). The false discovery rate was calculated as the percentage of reverse decoy peptide/spectrum matches (PSM) among all the PSM that passed the 99.9% confidence threshold. After this last filtering step, the peptide false discovery rate was estimated to be below 1%.

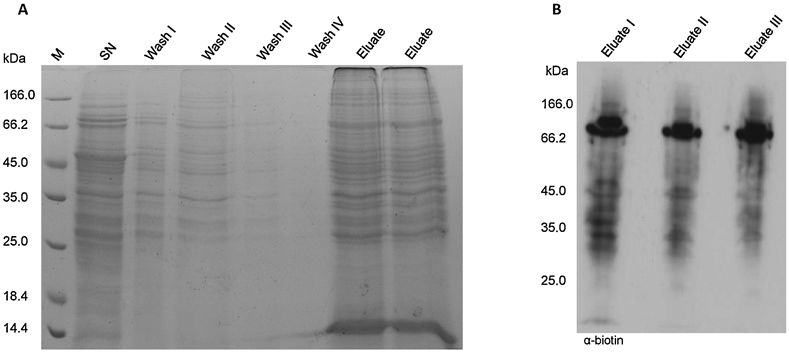

Figure 2 –

A: Gel electrophoresis of pull-down steps. Samples collected during pull-down were subjected to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. B: Immunodetection of pull-down eluates from 3 biological replicates using α-biotin.

Protein clustering

Identified target proteins for sulfenylation were clustered according to their molecular function and their involvement in biological processes using gene ontology (GO) slim annotations. At the same time enrichment analysis was performed using the enrichment tool by PlasmoDB (www.plasmodb.org). Pie charts were produced using Microsoft Excel 2019.

3. Results

Identification of sulfenylated proteins in P. falciparum cell extracts

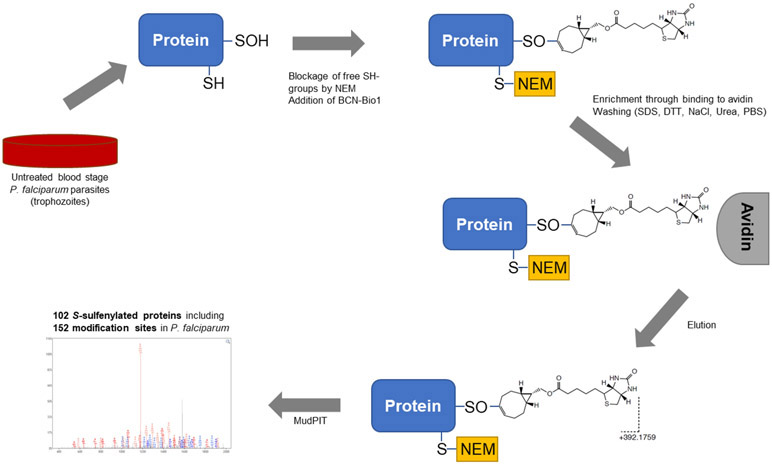

To gain an insight into P. falciparum’s trophozoite sulfenylome, the protein sulfenylation labeling probe BCN-Bio1 was used. In this approach, modified proteins were specifically labeled prior to enrichment and mass spectrometry analysis (Figure 1). Only proteins for which the modified sulfenylated peptide was identified by a specific mass shift of +392.1759 for BCN-Bio1 bound to a sulfenylated cysteine, and +141.0426 for NEM bound to a sulfenylated cysteine were accepted as true hits. +141.0426 was included because Reisz and coworkers have shown that alkylating agents, such as NEM show similar rate constants toward sulfenic acid as do sulfenic acids detection probes [31]. Protein persulfides, which have also been shown to react with strained cycloalkynes as BCN-Bio1 were not included in the search [37]. Stringent search parameters (detailed in materials and methods) identified 167 peptides containing a modification, representing 152 modification sites on 102 proteins (Table 1). 38 of these modification sites were detected in 2/3 replicates and 39 in all 3 biological replicates. Supplementary S2 lists all proteins with identified modification, the respective peptides including sulfenylation sites and statistics.

Figure 1 –

Schematic workflow of pull-down protocol Sulfenylated proteins of P. falciparum trophozoites were covalently labeled by BCN-Bio1, Free thiols were blocked by N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). Enrichment using avidin beads was performed. Throughout stringend washing steps unspecifically bound proteins were removed. Eluted proteins were analysed using multidimensional protein identification technique (MudPIT). Sulfenylated peptides labeld by BCN-Bio1 can be detected in MudPIT analysis by a mass shift of +392.1759 Da.

Table 1.

Proteins identified by mass spectrometry as being sulfenylated sorted according to their biological function (UniProt.org).

| N° | PlasmoDB Accession N° |

Protein name | Molar mass (kDa) |

Sequence coverage in each replicate a |

SOH site b | Protein nitrosylated [16] c |

Protein glutathionylated [15] d |

Predicted localisation e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biosynthetic pathway | ||||||||

| 1 | PF3D7_0511800 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase | 69.1 | 69.9% / 76.0% / 71.9% | C560 | + | + | |

| 2 | PF3D7_0513300 | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | 26.9 | 71.4% / 69.8% / 82.0% | C71 C141 C208 | + | + | |

| 3 | PF3D7_0608800 | Ornithine aminotransferase | 46.0 | 65.9% / 54.1% / 40.6% | C63 | + | + | |

| 4 | PF3D7_0621200 | Pyridoxine biosynthesis protein PDX1 | 33.0 | 63.1% / 62.5% / 63.1% | C16 C177 | + | + | |

| 5 | PF3D7_0810800 | Dihydropteroate synthetase | 83.4 | 43.2% / 51.4% / 42.1% | C473 | + | ||

| 6 | PF3D7_0918900 | Gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase | 124.5 | 22.8% / 29.6% / 32.8% | C103 6 + C103 8 | + | ||

| 7 | PF3D7_0922200 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (PfSAMS) | 44.8 | 71.9% / 73.1% / 68.4% | C264 | + C113 | + | |

| 8 | PF3D7_0922600 | Glutamine synthetase, putative | 63.2 | 57.3% / 61.7% / 50.3% | C66 C346 C479 | |||

| 9 | PF3D7_0926700 | Glutamine-dependent NAD(+) synthetase, putative | 97.8 | 24.7% / 22.8% / 11.9% | C91 | + | ||

| 10 | PF3D7_1343000 | Phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase | 31.0 | 82.0% / 82.0% / 86.1% | C70 C87 C161 | + | + | |

| 11 | PF3D7_1354500 | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | 50.1 | 46.4% / 52.9% / 35.5% | C283 C396 | + | ||

| Cell cycle/Proliferation | ||||||||

| 12 | PF3D7_0511000 | Translationally-controlled tumor protein homolog | 20.0 | 60.2% / 60.2% / 67.3% | C14 | + C14 | + | |

| 13 | PF3D7_0619400 | Cell division cycle protein 48 homologue, putative | 92.4 | 56.2% / 61.4% / 67.4% | C418 + C425 C425 C575 | + C695 | + | |

| Cellular redox homeostasis | ||||||||

| 14 | PF3D7_0802200 | 1-cys peroxiredoxin | 25.2 | 58.6% / 61.4% / 45.0% | C101 | + C184 | + | |

| 15 | PF3D7_0814900 | Superoxide dismutase [Fe] | 22.7 | 72.2% / 90.9% / 72.7% | C85 C116 | + | ||

| 16 | PF3D7_0923800.1 PF3D7_0923800.2 | Thioredoxin reductase | 68.7 | 44.7% / 34.2% / 39.7% 51.0% / 39.0% / 45.3% | C422 | + | ||

| 17 | PF3D7_1438900 | Thioredoxin peroxidase 1 | 21.8 | 79.0% / 86.2% / 63.6% | C170 | + | + | |

| Cytoskeleton | ||||||||

| 18 | PF3D7_0422300 | Alpha tubulin 2 | 49.7 | 33.6% / 35.8% / 35.8% | C376 | |||

| 19 | PF3D7_0903700 | Alpha tubulin 1 | 50.3 | 45.3% / 49.0% / 43.9% | C376 | + C65 | ||

| 20 | PF3D7_1008700 | Tubulin beta chain | 49.8 | 42.9% / 50.8% / 43.8% | C127 C129 | + | ||

| 21 | PF3D7_1473300 | CKK domain-containing protein, putative | 114.3 | X / 1.4% / 1.4% | C456 | |||

| DNA and RNA metabolism and processing | ||||||||

| 22 | PF3D7_0624600 | SNF2 helicase, putative | 315.6 | 22.6% / 25.7% / 23.3% | C147 + C150* | + | ||

| 23 | PF3D7_0711500 | Regulator of chromosome condensation, putative | 78.9 | 30.1% / 24.9% / 30.5% | C66 | |||

| 24 | PF3D7_0717700 | Serine-tRNA ligase, putative | 62.5 | 45.1% / 60.1% / 51.0% | C247 | + | + | |

| 25 | PF3D7_0812500 | RNA-binding protein, putative | 117.1 | 7.1% / 8.5% / 6.4% | C182' | + | ||

| 26 | PF3D7_1224300 | polyadenylate-binding protein, putative | 97.2 | 40.6% / 50.3% / 48.9% | C410 | + C234 | + | |

| 27 | PF3D7_1346300 | DNA/RNA-binding protein Alba 2 | 25.0 | 51.2% / 46.0% / 46.4% | C133 | + | + | |

| 28 | PF3D7_1347500 | DNA/RNA-binding protein Alba 4 | 42.2 | 70.7% / 77.4% / 74.2% | C63 C286 | + | + | |

| 29 | PF3D7_1461900 | Valine--tRNA ligase, putative | 128.1 | 45.0% / 53.1% / 45.2% | C428 | + | ||

| Glycolysis | ||||||||

| 30 | PF3D7_0626800 | Pyruvate kinase (PfPK) | 55.7 | 60.3% / 56.6% / 58.7% | C222 C302 C343 C433 | + | + | |

| 31 | PF3D7_0915400 | 6-phosphofructokinase | 159.5 | 55.7% / 54.5% / 53.2% | C645 C1321 C1038 | + C777 | + | |

| 32 | PF3D7_1015900 | Enolase | 48.7 | 81.8% / 83.9% / 87.2% | C157 C370 | + | + | |

| 33 | PF3D7_1324900 | L-lactate dehydrogenase (PfLDH) | 34.1 | 74.4% / 72.5% / 71.8% | C59 C260 | + | + | SP |

| 34 | PF3D7_1439900 | Triosephosphate isomerase | 27.9 | 72.2% / 73.8% / 76.2% | C217 | + | + | |

| 35 | PF3D7_1444800 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 40.1 | 84.0% / 83.2% / 82.1% | C247 | + | ||

| 36 | PF3D7_1462800 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (PfGAPDH) | 36.6 | 78.9% / 81.9% / 81.6% | C58 C157 C250 | + | + | |

| Kinase/ Signal transduction | ||||||||

| 37 | PF3D7_0818200 | 14-3-3 protein | 30.2 | 65.6% / 63.0% / 61.1% | C41 | + | + | |

| 38 | PF3D7_0826700 | Receptor for activated c kinase | 35.7 | 57.6% / 58.5% / 60.4% | C162 C177 C216 C384 | + | + | |

| 39 | PF3D7_1103700 | Casein kinase II beta chain | 28.4 | 29.4% / 34.3% / 27.3% | C122 | + | ||

| 40 | PF3D7_1124600 | Ethanolamine kinase | 49.9 | 39.5% / 53.2% / 57.4% | C283 | + | + | |

| 41 | PF3D7_1144500 | Ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1) subunit Aos1, putative | 39.7 | 28.1% / 25.7% / 29.9% | C297 | |||

| 42 | PF3D7_1242800 | Rab specific GDP dissociation inhibitor | 52.3 | 54.5% / 64.7% / 56.0% | C250 | + | ||

| 43 | PF3D7_1414400 | Serine/threonine protein phosphatase PP1 | 34.9 | 50.3% / 58.2% / 53.3% | C169 | |||

| Miscellaneous | ||||||||

| 44 | PF3D7_0406400 | Cytosolic glyoxalase II | 30.5 | 45.6% / 42.6% / 42.2% | C4 | + | + | |

| 45 | PF3D7_1012400 | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase | 26.4 | 72.7% / 81.8% / 73.2% | C134 | + | + | |

| 46 | PF3D7_1033400 | Haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase | 32.8 | 56.9% / 55.9% / 63.5% | C92 | + | ||

| 47 | PF3D7_1311900 | Vacuolar ATP synthase subunit a | 68.6 | 72.5% / 79.5% / 67.3% | C526 | + | + | |

| 48 | PF3D7_1406300 | Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase | 56.3 | 67.4% / 68.2% / 53.9% | C91 | + | SP | |

| Pathogenesis / Evasion / Protein export / Antigen | ||||||||

| 49 | PF3D7_0929400 | High molecular weight rhoptry protein 2 | 162.7 | 61.3% / 60.4% / 62.6% | C1344/ C1344' | + | + | SP/Rhop |

| 50 | PF3D7_0930300 | Merozoite surface protein 1 | 195.7 | 41.5% / 60.6% / 63.7% | C173 | + | + | SP/PM |

| 51 | PF3D7_1028700 | Merozoite TRAP-like protein | 58.1 | X / 8.4% / 26.3% | C47 | SP | ||

| 52 | PF3D7_1029600 | Adenosine deaminase | 42.5 | 68.7% / 80.7% / 70.3% | C173 C281 | + | + | |

| 53 | PF3D7_1126000 | Threonine-tRNA ligase | 119.5 | 43.8% / 47.0% / 40.4% | C428 C589 C767 | + | SP/AP | |

| 54 | PF3D7_1229400 | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | 12.8 | 94.8% / 95.7% / 95.7% | C3/C3' C4/C4' C3+C4 | + | + | |

| Protein / hemoglobin degradation | ||||||||

| 55 | PF3D7_0207600 | Serine repeat antigen 5 | 111.8 | 48.4% / 58.8% / 57.4% | C672 | + | + | SP/PV |

| 56 | PF3D7_1115400 | Cysteine proteinase falcipain 3 | 56.7 | 42.9% / 48.4% / 41.9% | C331 | + | + | FV |

| 57 | PF3D7_1118300 | Insulinase, putative | 173.6 | 36.6% / 31.3% / 31.9% | C322 C1364 | + | + | |

| 58 | PF3D7_1225800 | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 | 131.8 | 48.6% / 51.2% / 46.5% | C641 | + | ||

| 59 | PF3D7_1311800 | M1-family alanyl aminopeptidase | 126.1 | 76.9% / 80.0% / 78.9% | C140 C617 | + | + | |

| 60 | PF3D7_1360800 | Falcilysin | 138.9 | 51.4% / 57.3% / 61.3% | C438 | + | + | FV |

| 61 | PF3D7_1407800 | Plasmepsin IV | 51.0 | 47.0% / 48.8% / 43.0% | C370 | + | + | FV |

| 62 | PF3D7_1446200 | M17 leucyl aminopeptidase | 67.8 | 59.0% / 53.9% / 55.4% | C121 | + | + | |

| Protein degradation | ||||||||

| 63 | PF3D7_0317000 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-3, putative | 29.3 | 46.0% / 42.9% / 39.3% | C222 | + | ||

| 64 | PF3D7_0727400 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-5, putative | 28.4 | 82.8% / 75.0% / 82.8% | C76 C112 | + | + | |

| 65 | PF3D7_0807500 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-6, putative | 29.5 | 81.9% / 77.3% / 68.8% | C172 | + | ||

| 66 | PF3D7_0932300 | M18 aspartyl aminopeptidase | 65.6 | 52.6% / 52.3% / 49.5% | C226 | + | ||

| 67 | PF3D7_1248900 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 8, putative | 49.5 | 33.1% / 32.2% / 35.6% | C391 | |||

| 68 | PF3D7_1306400 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 10B, putative | 44.7 | 35.6% / 42.2% / 38.9% | C111' | |||

| 69 | PF3D7_1402300 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit RPN6 | 78.4 | 20.6% / 23.0% / 16.2% | C377 | |||

| Protein folding | ||||||||

| 70 | PF3D7_0214000 | T-complex protein 1, putative | 61.0 | 48.2% / 51.3% / 40.8% | C184 C499 | |||

| 71 | PF3D7_0320300 | T-complex protein 1 epsilon subunit, putative | 59.2 | 40.4% / 25.6% / 32.7% | C458 | + | ||

| 72 | PF3D7_0322000 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 19.0 | 64.3% / 49.1% / 49.1% | C69 | + C168 | + | ER |

| 73 | PF3D7_0527500 | Hsc70-interacting protein | 51.1 | 29.7% / 30.8% / 23.4% | C17 C187 | + C187 | + | |

| 74 | PF3D7_0627500 | Protein DJ-1 | 20.3 | 86.2% / 86.2% / 81.5% | C85 C106/ C106' | + | + | |

| 75 | PF3D7_0708400 | Heat shock protein 90 | 86.2 | 58.3% / 63.0% / 59.9% | C393 C616 | + | + | |

| 76 | PF3D7_0708800 | Heat shock protein 110 | 100.0 | 50.2% / 57.4% / 59.9% | C265 C606 | + | + | |

| 77 | PF3D7_0818900 | Heat shock protein 70 (PfHsp70-1) | 73.9 | 77.3% / 65.6% / 68.5% | C28 C583 | + | + | |

| 78 | PF3D7_0827900 | Protein disulfide isomerase | 55.5 | 68.1% / 69.8% / 75.2% | C384 C387 | + | + | SP/ER |

| 79 | PF3D7_1118200 | Heat shock protein 90, putative | 108.5 | 43.2% / 48.6% / 39.2% | C556 | + | ||

| 80 | PF3D7_1344200 | Heat shock protein 110, putative | 108.2 | 62.4% / 72.4% / 73.6% | C23 | + | + | SP/ER |

| Protein transport | ||||||||

| 81 | PF3D7_0210000 | Secretory complex protein 61 gamma subunit | 9.3 | 34.6% / 34.6% / 34.6% | C19 | ER | ||

| 82 | PF3D7_0214100 | Protein transport protein SEC31 | 166.7 | 25.8% / 33.6% / 29.4% | C309 | |||

| 83 | PF3D7_0524000 | Karyopherin beta | 127.4 | 59.1% / 60.1% / 52.9% | C212 C452 | + | ||

| 84 | PF3D7_1361100 | Protein transport protein Sec24A | 106.7 | 22.6% / 28.5% / 29.0% | C251 | |||

| Transcription | ||||||||

| 85 | PF3D7_1011800 | PRE-binding protein | 131.6 | 49.0% / 46.8% / 51.8% | C505 | + | + | |

| Translation | ||||||||

| 86 | PF3D7_0309600 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P2 | 11.9 | 92.0% / 92.0% / 82.1% | C12 | + | + | |

| 87 | PF3D7_1103100 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P1, putative | 13.0 | 85.6% / 83.1% / 83.1% | C19 | + | ||

| 88 | PF3D7_1204300 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A | 17.6 | 51.6% / 51.6% / 54.0% | C73 | + C73 + C148 | + | |

| 89 | PF3D7_1302800 | 40S ribosomal protein S7, putative | 22.5 | 48.5% / 22.2% / 33.0% | C23 | |||

| 90 | PF3D7_1323400 | 60S ribosomal protein L23 | 22.1 | 31.6% / 25.3% / 19.5% | C134 | |||

| 91 | PF3D7_1338300 | Elongation factor 1-gamma, putative | 47.8 | 46.0% / 55.2% / 54.3% | C70 | + | + | |

| 92 | PF3D7_1357000 / PF3D7_1357100 | Elongation factor 1-alpha | 49.0 | 68.8% / 63.9% / 67.5% | C356 | + | + | |

| 93 | PF3D7_1434600 | Methionine aminopeptidase 2 | 71.7 | 33.9% / 30.4% / 25.3% | C447 | |||

| 94 | PF3D7_1438000 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF2A, putative | 76.8 | 36.6% / 36.9% / 31.6% | C176 | + | ||

| 95 | PF3D7_1451100 | Elongation factor 2 | 93.5 | 59.3% / 63.3% / 67.1% | C130 C362 C653 C725 C786 | + C565 | + | |

| 96 | PF3D7_1468700 | Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A | 45.3 | 67.3% / 67.3% / 63.8% | C291 | + | + | |

| Unknown | ||||||||

| 97 | PF3D7_0321800 | WD repeat-containing protein, putative | 322.2 | X / X / 0.6% | C2321 | |||

| 98 | PF3D7_0811400 | Conserved protein, unknown function | 71.4 | 45.9% / 54.1% / 43.9% | C517 | + | ||

| 99 | PF3D7_0813300 | Conserved Plasmodium protein, unknown function | 36.3 | 32.4% / 32.4% / 32.4% | C61 | + | + | |

| 100 | PF3D7_1023900 | Chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 1 homolog, putative | 381.3 | 16.0% / 18.4% / 19.4% | C1375 | + | + | |

| 101 | PF3D7_1205600 | Conserved Plasmodium protein, unknown function | 39.0 | 28.5% / 37.2% / 27.6% | C213 | + | + | |

| 102 | PF3D7_1361800 | Conserved Plasmodium protein, unknown function | 291.0 | 42.7% / 39.8% / 41.5% | C821 C1337 C1549 | |||

Indicates the percentage of a protein’s sequence in one of three independently conducted experiments which has been covered in mass spectrometry analysis.

Cysteines which were identified as being sulfenylated due to a mass shift of C = SO-NEM (+141.0426); C* = SO-BCN-Bio1 (+392.177), and their position in a protein’s amino sequence are listed. “C + C” indicates two cysteines in the same peptide sequence which were found to be simultaneously sulfenylated.

“+” indicates proteins which were also identified by Wang et al. as being S-nitrosated. If available, the modified cysteine is given. Proteins found to be non-specifically enriched were subtracted [16].

“+” indicates proteins which were also identified by Kehr et al. as being S-glutathionylated. Proteins found to be non-specifically enriched were subtracted [15].

SP, signal peptide; AP, apicoplast; PV, parasitophorous vacuole; PM, plasma membrane; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FV, food vacuole; Rhop, rhoptry. Annotation based on PlasmoDB/SIgnalP analyses.

Throughout preparation collected samples were subjected to protein concentration measurements, SDS-PAGE and immunodetection targeting the biotin moiety of BCN-Bio1 with an anti-biotin antibody. Thus, the efficiency of the protocol throughout the 3 independently performed experiments was confirmed (Figure 2B, Supplementary S1). The eluates of the 3 biological replicates showed similar lane patterns of proteins of varying sizes ranging from low to high mass, indicating a broad distribution of sulfenylated proteins (Figure 2B). Notably, 2 bands between 66 and 166 kDa appeared more prominent in all 3 samples. One would expect those proteins to be highly abundant in mass spectrometry analysis, potentially overlapping other protein signals. Therefore, MS data were searched for the highest abundance proteins. L-lactate dehydrogenase (PF3D7_1324900, PfLDH) showed the highest spectrum count but has only a molecular mass of only 34.1 kDa, not represented by a remarkably prominent lane in immunodetection. P. falciparum proteins in a mass range of 66 to 110 kDa such as heat shock protein 70 (PfHsp70-1, PF3D7_0818900), elongation factor 2 (PF3D7_1451100), and inositol-3-phosphate synthase (PF3D7_0511800) showed spectrum counts less than half that of PfLDH. Regarding human proteins, only human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (HsGAPDH, 36.1 kDa) showed a spectrum count in the same range as PfHsp70-1 (see S2). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), which is a constituent of the cell culture medium, has a molecular mass of 69.3 kDa. It was identified in all 3 replicates but at a spectrum count 100 times lower than that of PfHsp70-1. It is thus not totally clear what the dominant bands in WB analysis represent, but they do not seem to influence MS analysis.

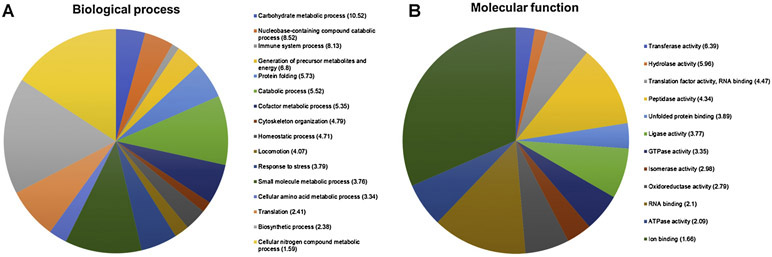

Classification of sulfenylated proteins in P. falciparum

In order to obtain a better overview of the proteins’ characteristics, identified sulfenylation targets were clustered according to their gene ontology (GO) slim annotations depicting their role in biological processes and molecular functions (Figure 3, Supplementary S3). Sulfenylated proteins of P. falciparum seem to be involved in a large variety of biological processes such as biosynthesis, locomotion, translation, response to stress, and protein folding (Figure 3A). A GO (gene ontology) enrichment analysis using slim GO terms (biological processes) reveals that our dataset is highly enriched in proteins involved in carbohydrate metabolism and nucleobase-containing compound catabolic processing. The first group, which is enriched more than 10-fold, comprises mainly glycolytic enzymes, and will be discussed in more detail later. The second group, enriched over 8-fold, contains the enzymes purine nucleoside phosphorylase, adenosine deaminase, and adenylosuccinate synthase

Figure 3 -.

Functional classification and enrichment of sulfenylated proteins in the trophozoite stage of P. falciparum. Sulfenylated proteins identified were clustered according to their gene ontology (GO) annotations in biological process (A) and molecular function (B). The number in brackets indicates the enrichment of the respective GO slim term compared to all P. falciparum proteins. GO slim enrichment analysis was performed using the online enrichment tool of PlasmoDB (www.plasmodb.org)

Clustering according to the involvement in molecular function gives a different pattern (Figure 3B). More than a quarter of identified sulfenylated proteins participate in ion binding, such as SNF2 helicase and S-adenosylmethionine synthase. The second largest group is formed by proteins involved in RNA binding, followed by proteins with peptidase activity. Enrichment analysis reveals more than 6-fold enrichment of proteins with transferase activity such as dihydropteroate synthase, ethanolamine kinase, and elongation factor 1-gamma. Proteins with hydrolase activity such as glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase and insulinase are also enriched more than 5-fold compared to background.

4. Discussion

Redox PTMs play a major role in cellular regulation as they affect the structure and function of numerous proteins [38]. Sulfenylation, as a reversible oxidative modification, has been shown to serve as a regulator of transcription factors, a sensor for oxidative stress, and mediate in general redox signaling [21]. In this study BCN-Bio1, a highly strained bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne, showing high reactivity with sulfenylated proteins [28], was used to identify the P. falciparum trophozoite sulfenylome.

Previous redox studies focusing on the malaria parasite P. falciparum revealed 32 putative interaction partners for the redox enzymes thioredoxin (PfTrx), glutaredoxin (PfGrx), and plasmoredoxin (PfPlrx) [14]. Furthermore, in pull-down analysis of whole cell lysates of the trophozoite stage, 491 and 317 putative targets for S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosation were identified, respectively [15,16]. To deepen our understanding of the interplay between redox PTMs in P. falciparum, this current study focused on the identification of sulfenylated proteins to enable comparison with other previously identified redox PTM targets.

A common issue in bottom-up proteomics is the over-representation of abundant proteins in datasets. Therefore, the identified sulfenylation targets in this study were first checked for their abundance in the trophozoite stage. Global proteomic studies revealed abundance levels of Plasmodium proteins over different stages of development [39]. S2 shows the broad distribution of abundance levels of proteins identified in this study, thus verifying the enrichment method applied, which enables identification of even low abundance proteins.

Of 167 detected modified peptides around 50% were detected in one out of three biological replicates, but with high confidence. This underlines the difficulties in detecting modification sites. As sulfenylation is a highly dynamic modification, trapping it remains highly challenging. Some of these peptides may well be of low abundance, further complicating the identification. Alternative approaches such as direct detection of biotin-containing tags (DiDBiT) can improve the detection of modification sites. In this approach proteins labeled by a biotin-tag containing probe are digested prior to enrichment. This is reported to increase detection efficiency by up to 50% [40].

While comparing overall P. falciparum sulfenylation patterns of trophozoites with sulfenylation patterns of other organisms, comparable levels of modified proteins can be observed. Out of P. falciparum isolate 3D7’s predicted 5,449 proteins, 102 are found to be sulfenylated, representing approximately 1.9% of the proteome. In Homo sapiens (H. sapiens) 1,285 out of 74,788 proteins could be detected as sulfenylation targets, representing around 1.7% [41]. In Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana, 39,361 proteins), 1,394 proteins were identified as targets for sulfenylation, giving a coverage of around 3.5% [42].

Clustering of sulfenylated proteins revealed large distribution amongst different biological processes and molecular functions (Figure 3). At the same time certain GO slim terms are more enriched than others. Clustering sulfenylated proteins according to their molecular functions shows around 6-fold enrichment of transferase and hydrolase activity while carbohydrate metabolic process is enriched more than 10-fold. Proteins belonging to those GO terms may be especially susceptible towards oxidative modification. Whether this modification is required for regulation these proteins has to be elucidated in detail

Proteins of the glycolytic pathway appear to be particularly targeted for sulfenylation; 7% of P. falciparum’s sulfenylated proteins belong to this pathway, despite representing only 0.001% of all total predicted proteins. Glycolysis is crucial for the survival of the intracellular parasite, as Plasmodium is reliant on the metabolization of glucose for ATP production [43]. A comparative study of glycolytic enzymes amongst different organisms reveals conserved sulfenylation patterns and sites. Table 2 compares the patterns of glycolytic enzymes phosphofructokinase, aldolase, triosephosphate isomerase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH), phosphoglycerate kinase, enolase, and pyruvate kinase (PK) in H. sapiens, A. thaliana, and P. falciparum. Six proteins were found to be sulfenylated in H. sapiens as well as in A. thaliana [44]. When these findings are compared with our dataset for P. falciparum, a high overlap can be observed; 7 out of 11 glycolytic enzymes were identified as targets for sulfenylation, including 6-phosphofructokinase (PfPFK1, PF3D7_0915400), fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (Pf3D7_1444800), triosephosphate isomerase (Pf3D7_1439900), PfGAPDH (PF3D7_1462800), enolase (PF3D7_1015900), PfPK (PF3D7_0626800), and PfLDH (PF3D7_1324900). With the exception of PfPFK1 and PfLDH, homologues of the other 5 proteins were also identified as being sulfenylated in H. sapiens and A. thaliana, indicating a strong conservation of sulfenylation patterns in proteins of the glycolysis pathway across kingdoms. The amino acid sequences surrounding the sulfenylated residue ot homologue proteins showed a high level of conservation (data not shown), and this together with limitations in a) the number of sequences available for comparison and, b) the lack of knowledge of specific sulfenylation patterns in all organisms studied, hindered us in being able to specify a “sulfenylation motif”, i.e a conserved pattern potentially required for sulfenylation.

Table 2.

Sulfenylated glycolysis enzymes previously found in different organisms. (+): Protein has been found to be sulfenylated. Modified according to [44].

| H. sapiens | A. thaliana | P. falciparum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphofructokinase | |||

| Aldolase | + | + | + |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | + | + | + |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-P-dehydrogenase | + | + | + |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | + | + | |

| Enolase | + | + | + |

| Pyruvate kinase | + | + | + |

Glycolytic enzymes identified as being sulfenylated in this current study have previously been identified as targets of S-glutathionylation (8/11) and S-nitrosation (10/11). These findings are in accordance with previous publications and imply a strong redox regulation of proteins in this key energy metabolism pathway [15,16]. Glycolytic proteins show high sequence conservation at their catalytic sites, but contain unique structural differences between parasitic and host homologues, rendering these proteins attractive targets for the development of antimalarials. Alam et al. describe the moonlighting functions of glycolytic proteins which may arise due to structural changes induced by PTMs [45]. Besides catalyzing the conversion of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, eukaryotic GAPDH is involved in, amongst others, gene regulation, vesicular transport, and cell signaling, as reviewed in [46]. The respective activity seems to be dependent on its cellular localization, influenced through PTMs such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and S-nitrosation [45]. PfGAPDH is expressed in all life stages [47] and out of 8 cysteine residues, 3 were identified as being sulfenylated (C56, C157, C250). PfGAPDH has previously also been confirmed as a target for S-glutathionylation. Depending on the concentration and the incubation time, the protein is reversibly inhibited by oxidized glutathione (GSSG) [15]. PfGAPDH’s active site cysteines were shown to be susceptible to S-nitrosation, leading to an inhibition of its enzymatic activity. Low molecular weight thiols such as reduced glutathione can reverse this effect [48]. In general, sulfenylation as a consequence of oxidative disbalance may lead to a rapid adaption of different metabolic pathways and thus help organisms deal with this challenge [49].

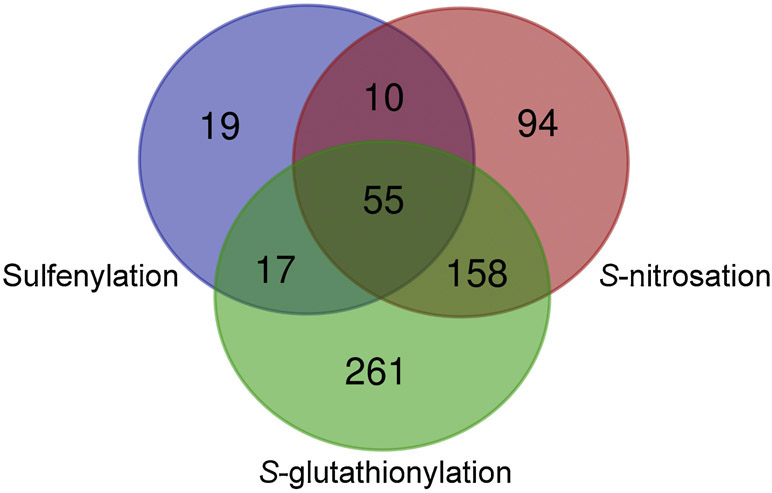

When our protein hit list is compared with previously reported targets for S-nitrosation and S-glutathionylation, we find that out of 102 sulfenylated proteins, 55 were also found to be S-glutathionylated and S-nitrosated; 17 were found to be S-glutathionylated [15], and 10 to be S-nitrosated [16], meaning that around 80% of Plasmodium sulfenylated proteins are susceptible to more than one redox modification (Table1, Figure 4). For example, one of the sulfenylated proteins identified by this study was S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (PfSAMS). The enzyme catalyzes the formation of S-adenosylmethionine from methionine and ATP and thus participates in multiple processes (epigenetic, metabolism, signaling) supporting parasite growth. Its structure is highly homologous to other SAMS, especially those of plants and other protozoans [50]. Pretzel et al. demonstrated the contribution of Cys52, Cys113, and Cys187 to its redox regulation by influencing its structure and activity. Upon S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosation PfSAMS is inhibited, emphasizing the importance of redox regulation [51].

Figure 4 -.

Venn diagram depicting the overlap between P. falciparum proteins susceptible to different redox modifications Pull-down experiments identified 101 targets for sulfenylation, 491 target proteins for S-glutathionylation, and 317 target proteins for S-nitrosation [15,16]. 55 proteins were identified containing all 3 PTM. The Venn diagram was generated using the online tool http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/.

Our study also identified the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (PfMIF, PF3D7_ 1229400) as a target for sulfenylation. This protein is a homologue of the human cytokine MIF and is released into the host’s blood stream upon schizont rupture. It is predicted to modulate the human immune system, making it an interesting target for further study [52,53]. Of its four cysteines, Cys3 and Cys4 were identified as being susceptible to sulfenylation. These two cysteines have previously been shown to be crucial for antioxidant activities as well as for the Trx-like oxidoreductase activity of this protein [54]. PfMIF has also been identified as being glutathionylated and nitrosated in the trophozoite stage [15,16]. As this protein appears highly susceptible to redox modifications while itself participating in antioxidant activities, further research is needed to understand its putative regulatory mechanisms.

Thioredoxin peroxidase 1 (PfTrxPx [aka PfPrx1a], Pf3D7_1438900) belongs to the family of cysteine-dependent Prx enzymes. They reduce peroxides and can be recycled by PfTrx or PfGrx [55]. PfTrxPx is a 2-Cys Prx, meaning that two cysteines are involved in its catalytic cycle [56]. Its resolving cysteine Cys170 has been identified as being sulfenylated in this study. This cysteine, as well as its peroxidatic cysteine Cys50, are important for the Prx-based redox regulation of 127 cytosolic target proteins as shown by Brandstaedter and coworkers [57].

These findings indicate possible general crosstalk between redox modifications. As sulfenic acids are often intermediates en route to more stable modifications, it is likely that proteins are initially sulfenylated under unstressed conditions and upon stress are further modified, becoming for example S-glutathionylated or S-nitrosated upon exposure to glutathione or NO-donors. Both modifications are thought to protect thiols against irreversible oxidation [58,59]. In general, the exposure of a cysteine, its pKa and its electrophilicity determine its reactivity [60]. Surface exposure of cysteines, and thus accessibility for modification can change depending on structural modifications of the protein [61,62]. In some cases, redox sensitive proteins are able to shuttle between different compartments of a cell and are thus subjected to changing redox environments, such as proximity to metal centers, rapid changes in local pH, and changes in solvent access. These factors may all affect the pKa and reactivity of critical cysteine(s) [63]. Further studies have investigated non-redox PTMs in Plasmodium, including phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation, as reviewed in [9,64]. Today, more than 300 PTMs are known across a variety of systems, massively expanding a proteome’s diversity and complexity [65]. Nevertheless, their interplay still remains ambiguous, rendering additional research necessary. As PTMs are so consequential, significant efforts in antimalarial drug discovery focus on inhibition of enzymes mediating these modifications [66].

Some proteins detected in at least 2 replicates as being sulfenylated were previously found as targets for other PTMs, including PfSNF2 helicase (PF3D7_0624600). This nuclear protein is suggested to be part of large functional complexes involved in transcriptional regulation, and has been confirmed as a target for phosphorylation in Plasmodium [10,67]. Gene expression must be highly regulated to meet the needs of the parasite at each stage of the life-cycle, therefore it is not surprising that proteins involved in transcription are especially targets for sulfenylation, allowing for fine tuning of gene regulation.

The cyclophilin peptidyl-prolyl-cis-trans-isomerase (PF3D7_0322000) accelerates the folding of Plasmodium proteins through cis-trans isomerase activity and shows a chaperone function in a comparable manner to heat shock proteins [68]. This activity is inhibited by the cyclic peptide cyclosporine A, which also has an antimalarial effect [69]. Besides sulfenylation, S-glutathionylation, and S-nitrosation, this protein has been detected as a target for mono-ubiquitination [12]. This rapidly reversible modification can label a protein for degradation [12]. Furthermore, this protein has recently been identified as being an interaction partner of peroxiredoxin 1 a (PfPrx1a) [57]. It is thought that PfPrx, which undergoes sulfenylation during its catalytic cycle, can transfer this oxidation to an interacting protein, thus regulating its activity [70].

We investigated the predicted sub-cellular localisation of targets of sulfenylation (Table 1). This analysis revealed that sulfenylation can take place on proteins with a wide range of localisations, including plasma membrane, food vacuole, apicoplast, rhoptries and endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and highlights that sulfenylation takes place in at least several cellular compartments, and that sulfenylation activity is not restricted merely to the parasite cytosol.

In a previous study, Sturm et al. identified 32 proteins interacting with the redox enzymes thioredoxin (PfTrx), glutaredoxin (PfGrx), and plasmoredoxin (PfPlrx) [14]. Those which interact with more than one of the redox enzymes are also more likely to be sulfenylated, giving an overlap of 14 proteins (Table 3). One of them is the enzyme pyruvate kinase (PfPK) (PF3D7_0626800). It has been shown that S-glutathionylation leads to inhibition of PfPK in a concentration dependent reversible mode [15]. Additionally, PfPK is susceptible to S-nitrosation and 3 of its 15 cysteines have been found to be sulfenylated [16]. These data indicate a strong susceptibility towards redox regulation of this rate-limiting enzyme, which is needed to adapt the glycolytic flux to changing environments, such as those experienced as the parasite passes from vertebrate host to mosquito vector and vice versa [71].

Table 3.

P. falciparum sulfenylated proteins identified as interaction partners of thioredoxin (Trx), glutaredoxin (Grx), or plasmoredoxin (Plrx) [14].

| PlasmoDB Accession n° |

Protein name | Trx | Grx | Plrx | SOH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PF3D7_0608800 | Ornithine aminotransferase | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | PF3D7_0626800 | Pyruvate kinase | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | PF3D7_0708400 | Heat shock protein 90 | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | PF3D7_0802200 | 1-cys peroxiredoxin | + | + | ||

| 5 | PF3D7_0818200 | 14-3-3 protein | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | PF3D7_0818900 | Heat shock protein 70 | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | PF3D7_0826700 | Receptor for activated c kinase | + | + | ||

| 8 | PF3D7_0827900 | Protein disulfide isomerase | + | + | ||

| 9 | PF3D7_0922200 | S-adenosylmethionine synthetase | + | + | + | + |

| 10 | PF3D7_1324900 | L-lactate dehydrogenase | + | + | ||

| 11 | PF3D7_1343000 | Phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase | + | + | ||

| 12 | PF3D7_1438900 | Thioredoxin peroxidase 1 | + | + | ||

| 13 | PF3D7_1451100 | Elongation factor 2 | + | + | + | |

| 14 | PF3D7_1462800 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | + | + | + |

As mentioned above, a certain conservation of sulfenylation can be observed across different kingdoms. However, when comparing the hit list for P. falciparum with identified sulfenylated proteins of H. sapiens, differences become obvious. Of the 102 P. falciparum target proteins, 20 are parasite-specific and do not have a human homologue, for 52 proteins there is evidence that the human homologues are also subject to sulfenylation [27,72]. The remaining 26 proteins were found to be sulfenylated in the parasite but not in its host. It may be that those proteins have distinct regulatory mechanisms. One of these proteins is M17 leucyl aminopeptidase (PF3D7_1446200). This protein is a known target for the development of antimalarial drugs, as inhibition leads to death of P. falciparum in culture [73]. The protein catalyzes the release of neutral amino acids from the N-terminus of peptides, thus participating in hemoglobin digestion, pivotal for parasite survival [74], but a role of redox PTM in modulation of its activity has not yet been described.

Proteomic analyses of P. falciparum have revealed susceptibility of its proteins towards multiple PTMs, whereas possible cross talk between different modifications remains to be elucidated in detail. Our identification of sulfenylation targets give an interesting new insight into the redox regulation of the parasite’s proteins and allow for further structural and functional analysis of identified target proteins. Nevertheless, proteomic approaches need to be supplemented with in vivo data, verifying the biological function of the respective modification. A better understanding of these complex mechanisms is pivotal for combatting the pathogen and thus fighting malaria.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Pull-down to identify sulfenylome of P. falciparum trophozoites.

102 sulfenylated proteins identified including 152 modification sites.

High overlap between target proteins for S-glutathionylation, S-nitrosation and sulfenylation.

Especially glycolytic cycle seems to be modified.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Siegrid Franke for excellent support in cell culture, and Esther Jortzik for her intellectual input to this project. JRY acknowledges support from National Institutes of Health grant (P41 GM103533). This work was supported by the DFG priority program SPP1710 (BE1540/23-2) to Katja Becker and Stefan Rahlfs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

CMF and LBP are co-founders of Xoder Technologies, LLC, which provides consulting services and commercializes reagents for redox investigations.

References

- [1].Phillips MA, Burrows JN, Manyando C, van Huijsduijnen RH, Voorhis WCV, Wells TNC, Malaria, Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 3 (2017) 17050. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Florens L, Washburn MP, Raine JD, Anthony RM, Grainger M, Flaynes JD, Moch JK, Muster N, Sacci JB, Tabb DL, Witney AA, Wolters D, Wu Y, Gardner MJ, Holder AA, Sinden RE, Yates JR, Carucci DJ, A proteomic view of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle, Nature. 419 (2002) 520–526. 10.1038/nature01107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tripathy S, Roy S, Redox sensing and signaling by malaria parasite in vertebrate host, J. Basic Microbiol 55 (2015) 1053–1063. 10.1002/jobm.201500031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jortzik E, Becker K, Thioredoxin and glutathione systems in Plasmodium falciparum, Int. J. Med. Microbiol 302 (2012) 187–194. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chaudhari R, Sharma S, Patankar S, Glutathione and thioredoxin systems of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum: Partners in crime?, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 488 (2017) 95–100. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Deponte M, Rahlfs S, Becker K, Peroxiredoxin systems of protozoal parasites, Subcell. Biochem 44 (2007) 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Qiu W, Dong A, Pizarro JC, Botchkarsev A, Min J, Wernimont AK, Hills T, Hui R, Artz JD, Crystal structures from the Plasmodium peroxiredoxins: new insights into oligomerization and product binding, BMC Struct. Biol 12 (2012) 2. 10.1186/1472-6807-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Becker K, Tilley L, Vennerstrom JL, Roberts D, Rogerson S, Ginsburg H, Oxidative stress in malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes: host-parasite interactions, Int. J. Parasitol 34 (2004) 163–189. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yakubu RR, Weiss LM, Silmon de Monerri NC, Post-translational modifications as key regulators of apicomplexan biology: insights from proteome-wide studies, Mol. Microbiol 107 (2018) 1–23. 10.1111/mmi.13867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alam MM, Solyakov L, Bottrill AR, Flueck C, Siddiqui FA, Singh S, Mistry S, Viskaduraki M, Lee K, Hopp CS, Chitnis CE, Doerig C, Moon RW, Green JL, Holder AA, Baker DA, Tobin AB, Phosphoproteomics reveals malaria parasite Protein Kinase G as a signalling hub regulating egress and invasion, Nat. Commun 6 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4507021/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cobbold SA, Santos JM, Ochoa A, Perlman DH, Llinás M, Proteome-wide analysis reveals widespread lysine acetylation of major protein complexes in the malaria parasite, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 19722. 10.1038/srep19722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ponts N, Saraf A, Chung D-WD, Harris A, Prudhomme J, Washburn MP, Florens L, Le Roch KG, Unraveling the Ubiquitome of the Human Malaria Parasite, J. Biol. Chem 286 (2011) 40320–40330. 10.1074/jbc.M111.238790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jortzik E, Wang L, Becker K, Thiol-Based Posttranslational Modifications in Parasites, Antioxid. Redox Signal 17 (2011) 657–673. 10.1089/ars.2011.4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sturm N, Jortzik E, Mailu BM, Koncarevic S, Deponte M, Forchhammer K, Rahlfs S, Becker K, Identification of Proteins Targeted by the Thioredoxin Superfamily in Plasmodium falciparum, PLOS Pathog. 5 (2009) e1000383. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kehr S, Jortzik E, Delahunty C, Yates JR, Rahlfs S, Becker K, Protein S-Glutathionylation in Malaria Parasites, Antioxid. Redox Signal 15 (2011) 2855–2865. 10.1089/ars.2011.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang L, Delahunty C, Prieto JH, Rahlfs S, Jortzik E, Yates JR, Becker K, Protein S-nitrosylation in Plasmodium falciparum, Antioxid. Redox Signal 20 (2013) 2923–2935. 10.1089/ars.2013.5553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Akter S, Fu L, Jung Y, Conte ML, Lawson JR, Lowther WT, Sun R, Liu K, Yang J, Carroll KS, Chemical proteomics reveals new targets of cysteine sulfinic acid reductase, Nat. Chem. Biol 14 (2018) 995–1004. 10.1038/S41589-018-0116-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Forshaw TE, Holmila R, Nelson KJ, Lewis JE, Kemp ML, Tsang AW, Poole LB, Lowther WT, Furdui CM, Peroxiredoxins in Cancer and Response to Radiation Therapies, Antioxidants. 8 (2019). 10.3390/antiox8010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gupta V, Carroll KS, Sulfenic acid chemistry, detection and cellular lifetime, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840 (2014) 847–875. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen X, Lee J, Wu H, Tsang AW, Furdui CM, Mass Spectrometry in Advancement of Redox Precision Medicine, in: Woods AG, Darie CC (Eds.), Adv. Mass Spectrom. Biomed. Res, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019: pp. 327–358. 10.1007/978-3-030-15950-4_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Salsbury FR, Knutson ST, Poole LB, Fetrow JS, Functional site profiling and electrostatic analysis of cysteines modifiable to cysteine sulfenic acid, Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc 17 (2008) 299–312. 10.1110/ps.073096508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Devarie-Baez NO, Silva Lopez EI, Furdui CM, Biological Chemistry and Functionality of Protein Sulfenic Acids and Related Thiol Modifications, Free Radic. Res 50 (2016) 172–194. 10.3109/10715762.2015.1090571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Paulsen CE, Carroll KS, Cysteine-Mediated Redox Signaling: Chemistry, Biology, and Tools for Discovery, Chem. Rev 113 (2013) 4633–4679. 10.1021/cr300163e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Poole LB, Nelson KJ, Discovering mechanisms of signaling-mediated cysteine oxidation, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 12 (2008) 18–24. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Leichert LI, Gehrke F, Gudiseva HV, Blackwell T, Ilbert M, Walker AK, Strahler JR, Andrews PC, Jakob U, Quantifying changes in the thiol redox proteome upon oxidative stress in vivo, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 105 (2008) 8197–8202. 10.1073/pnas.0707723105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Allison WS, Formation and reactions of sulfenic acids in proteins, Acc. Chem. Res 9 (1976) 293–299. 10.1021/ar50104a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gupta V, Yang J, Liebler DC, Carroll KS, Diverse Redoxome Reactivity Profiles of Carbon Nucleophiles, J. Am. Chem. Soc 139 (2017) 5588–5595. 10.1021/jacs.7b01791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Poole TH, Reisz JA, Zhao W, Poole LB, Furdui CM, King SB, Strained Cycloalkynes as New Protein Sulfenic Acid Traps, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136 (2014) 6167–6170. 10.1021/ja500364r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Trager W, Jensen JB, Human malaria parasites in continuous culture, Science. 193(1976) 673–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lambros C, Vanderberg JP, Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum Erythrocytic Stages in Culture, J. Parasitol 65 (1979) 418–420. 10.2307/3280287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Reisz JA, Bechtold E, King SB, Poole LB, Furdui CM, Thiol-Blocking Electrophiles Interfere with Labeling and Detection of Protein Sulfenic Acids, FEBS J. 280 (2013)6150–6161. 10.1111/febs.12535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wani R, Qian J, Yin L, Bechtold E, King SB, Poole LB, Paek E, Tsang AW, Furdui CM, Isoform-specific regulation of Akt by PDGF-induced reactive oxygen species, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108 (2011) 10550–10555. 10.1073/pnas.1011665108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xu T, Park SK, Venable JD, Wohlschlegel JA, Diedrich JK, Cociorva D, Lu B, Liao L, Hewel J, Han X, Wong CCL, Fonslow B, Delahunty C, Gao Y, Shah H, Yates III JR, ProLuCID: An improved SEQUEST-like algorithm with enhanced sensitivity and specificity, J. Proteomics 129 (2015) 16–24. 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cociorva D, Tabb DL, Yates JR, Validation of Tandem Mass Spectrometry Database Search Results Using DTASelect, in: Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/0471250953.bi1304s16/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tabb DL, McDonald WH, Yates JR, DTASelect and Contrast: Tools for Assembling and Comparing Protein Identifications from Shotgun Proteomics, J. Proteome Res 1 (2002)21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].McDonald WH, Tabb DL, Sadygov RG, MacCoss MJ, Venable J, Graumann J, Johnson JR, Cociorva D, Yates JR, MS1, MS2, and SQT—three unified, compact, and easily parsed file formats for the storage of shotgun proteomic spectra and identifications, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 18 (2004) 2162–2168. 10.1002/rcm.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Galardon E, Padovani D, Reactivity of Persulfides Toward Strained Bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne Derivatives: Relevance to Chemical Tagging of Proteins, Bioconjug. Chem (2015). 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wani R, Nagata A, Murray BW, Protein redox chemistry: post-translational cysteine modifications that regulate signal transduction and drug pharmacology, Front. Pharmacol 5 (2014). 10.3389/fphar.2014.00224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pease BN, Huttlin EL, Jedrychowski MP, Talevich E, Harmon J, Dillman T, Kannan N, Doerig C, Chakrabarti R, Gygi SP, Chakrabarti D, Global Analysis of Protein Expression and Phosphorylation of Three Stages of Plasmodium falciparum Intraerythrocytic Development, J. Proteome Res 12 (2013) 4028–4045. 10.1021/pr400394g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schiapparelli LM, McClatchy DB, Liu H-H, Sharma P, Yates JR, Cline HT, Direct Detection of Biotinylated Proteins by Mass Spectrometry, J. Proteome Res 13 (2014) 3966–3978. 10.1021/pr5002862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Li R, Klockenbusch C, Lin L, Jiang H, Lin S, Kast J, Quantitative Protein Sulfenic Acid Analysis Identifies Platelet Releasate-Induced Activation of Integrin β2 on Monocytes via NADPH Oxidase, J. Proteome Res 15 (2016) 4221–4233. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Huang J, Willems P, Wei B, Tian C, Ferreira RB, Bodra N, Gache SAM, Wahni K, Liu K, Vertommen D, Gevaert K, Carroll KS, Montagu MV, Yang J, Breusegem FV, Messens J, Mining for protein S-sulfenylation in Arabidopsis uncovers redox-sensitive sites, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 116 (2019) 21256–21261. 10.1073/pnas.1906768116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].van Niekerk DD, Penkler GP, du Toit F, Snoep JL, Targeting glycolysis in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, FEBS J. 283 (2016) 634–646. 10.1111/febs.13615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Huang J, Willems P, Van Breusegem F, Messens J, Pathways crossing mammalian and plant sulfenomic landscapes, Free Radic. Biol. Med (2018). 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Alam A, Neyaz MK, Ikramul Hasan S, Exploiting Unique Structural and Functional Properties of Malarial Glycolytic Enzymes for Antimalarial Drug Development, Malar. Res. Treat 2014 (2014) e451065. 10.1155/2014/451065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sirover MA, On the functional diversity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: Biochemical mechanisms and regulatory control, Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Gen. Subj 1810 (2011) 741–751. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Krause RGE, Hurdayal R, Choveaux D, Przyborski JM, Coetzer THT, Goldring JPD, Plasmodium glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: A potential malaria diagnostic target, Exp. Parasitol 179 (2017) 7–19. 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Padgett CM, Whorton AR, Glutathione redox cycle regulates nitric oxide-mediated glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibition, Am. J. Physiol.- Cell Physiol 272 (1997) C99–C108. 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.1.C99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Deng X, Weerapana E, Ulanovskaya O, Sun F, Liang H, Ji Q, Ye Y, Fu Y, Zhou L, Li J, Zhang H, Wang C, Alvarez S, Hicks LM, Lan L, Wu M, Cravatt BF, He C, Proteome-wide quantification and characterization of oxidation-sensitive cysteines in pathogenic bacteria, Cell Host Microbe. 13 (2013) 358–370. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chiang PK, Chamberlin ME, Nicholson D, Soubes S, Su X, Subramanian G, Lanar DE, Prigge ST, Scovill JP, Miller LH, Chou JY, Molecular characterization of Plasmodium falciparum S-adenosylmethionine synthetase, Biochem. J 344 Pt 2 (1999) 571–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pretzel J, Gehr M, Eisenkolb M, Wang L, Fritz-Wolf K, Rahlfs S, Becker K, Jortzik E, Characterization and redox regulation of Plasmodium falciparum methionine adenosyltransferase, J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 160 (2016) 355–367. 10.1093/jb/mvw045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Augustijn KD, Kleemann R, Thompson J, Kooistra T, Crawford CE, Reece SE, Pain A, Siebum AHG, Janse CJ, Waters AP, Functional Characterization of the Plasmodium falciparum and P. berghei Homologues of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor, Infect. Immun 75 (2007) 1116–1128. 10.1128/IAI.00902-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pantouris G, Rajasekaran D, Garcia AB, Ruiz VG, Leng L, Jorgensen WL, Bucala R, Lolis EJ, Crystallographic and Receptor Binding Characterization of Plasmodium falciparum Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Complexed to Two Potent Inhibitors, J. Med. Chem 57 (2014) 8652–8656. 10.1021/jm501168q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Alam A, Goyal M, Iqbal Mohd.S., Bindu S, Dey S, Pal C, Maity P, Mascarenhas NM, Ghoshal N, Bandyopadhyay U, Cysteine-3 and cysteine-4 are essential for the thioredoxin-like oxidoreductase and antioxidant activities of Plasmodium falciparum macrophage migration inhibitory factor, Free Radic. Biol. Med 50 (2011)1659–1668. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Perkins A, Nelson KJ, Parsonage D, Poole LB, Karplus PA, Peroxiredoxins: guardians against oxidative stress and modulators of peroxide signaling, Trends Biochem. Sci 40 (2015) 435–45. 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rahlfs S, Becker K, Thioredoxin peroxidases of the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum, Eur. J. Biochem 268 (2001) 1404–1409. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Brandstaedter C, Delahunty C, Schipper S, Rahlfs S, Yates JR, Becker K, The interactome of 2-Cys peroxiredoxins in Plasmodium falciparum, Sci. Rep 9 (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6753162/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sun J, Steenbergen C, Murphy E, S-Nitrosylation: NO-Related Redox Signaling to Protect Against Oxidative Stress, Antioxid. Redox Signal 8 (2006) 1693–1705. 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Scirè A, Cianfruglia L, Minnelli C, Bartolini D, Torquato P, Principato G, Galli F, Armeni T, Glutathione compartmentalization and its role in glutathionylation and other regulatory processes of cellular pathways, BioFactors. 45 (2019) 152–168. 10.1002/biof.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Marino SM, Gladyshev VN, Analysis and Functional Prediction of Reactive Cysteine Residues, J. Biol. Chem 287 (2012) 4419–4425. 10.1074/jbc.R111.275578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Fu L, Liu K, Sun M, Tian C, Sun R, Morales Betanzos C, Tallman KA, Porter NA, Yang Y, Guo D, Liebler DC, Yang J, Systematic and Quantitative Assessment of Hydrogen Peroxide Reactivity With Cysteines Across Human Proteomes, Mol. Cell. Proteomics MCP 16 (2017) 1815–1828. 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Bar-Peled L, Kemper EK, Suciu RM, Vinogradova EV, Backus KM, Horning BD, Paul TA, Ichu T-A, Svensson RU, Olucha J, Chang MW, Kok BP, Zhou Z, Ihle N, Dix MM, Jiang P, Hayward MM, Saez E, Shaw RJ, Cravatt BF, Chemical Proteomics Identifies Druggable Vulnerabilities in a Genetically Defined Cancer, Cell. 171 (2017) 696–709.e23. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Roos G, Foloppe N, Messens J, Understanding the pKa of Redox Cysteines: The Key Role of Hydrogen Bonding, Antioxid. Redox Signal 18 (2012) 94–127. 10.1089/ars.2012.4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Doug Chung D-W, Ponts N, Cervantes S, Le Roch KG, Post-translational modifications in Plasmodium: More than you think, Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 168 (2009) 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Witze ES, Old WM, Resing KA, Ahn NG, Mapping protein post-translational modifications with mass spectrometry, Nat. Methods 4 (2007) 798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Doerig C, Rayner JC, Scherf A, Tobin AB, Post-translational protein modifications in malaria parasites, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 13 (2015) 160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Volz J, Carvalho TG, Ralph SA, Gilson P, Thompson J, Tonkin CJ, Langer C, Crabb BS, Cowman AF, Potential epigenetic regulatory proteins localise to distinct nuclear sub-compartments in Plasmodium falciparum, Int. J. Parasitol 40 (2010) 109–121. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Marin-Menendez A, Monaghan P, Bell A, A family of cyclophilin-like molecular chaperones in Plasmodium falciparum, Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 184 (2012) 44–47. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bell A, Roberts HC, Chappell LH, The antiparasite effects of cyclosporin A: possible drug targets and clinical applications, Gen. Pharmacol. Vase. Syst 27 (1996) 963–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Netto LES, Antunes F, The Roles of Peroxiredoxin and Thioredoxin in Hydrogen Peroxide Sensing and in Signal Transduction, Mol. Cells 39 (2016) 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Bakszt R, Wernimont A, Allali-Hassani A, Mok MW, Hills T, Hui R, Pizarro JC, The Crystal Structure of Toxoplasma gondii Pyruvate Kinase 1, PLoS ONE. 5 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2939071/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Yang J, Gupta V, Carroll KS, Liebler DC, Site-specific mapping and quantification of protein S-sulphenylation in cells, Nat. Commun 5 (2014) 4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Skinner-Adams TS, Stack CM, Trenholme KR, Brown CL, Grembecka J, Lowther J, Mucha A, Drag M, Kafarski P, McGowan S, Whisstock JC, Gardiner DL, Dalton JP, Plasmodium falciparum neutral aminopeptidases: new targets for anti-malarials, Trends Biochem. Sci 35 (2010) 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Poreba M, McGowan S, Skinner-Adams TS, Trenholme KR, Gardiner DL, Whisstock JC, To J, Salvesen GS, Dalton JP, Drag M, Fingerprinting the Substrate Specificity of M1 and M17 Aminopeptidases of Human Malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, PLOS ONE. 7 (2012) e31938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.