Abstract

Phytopathogenic fungi in the order Diaporthales (Sordariomycetes) cause diseases on numerous economically important crops worldwide. In this study, we reassessed the diaporthalean species associated with prominent diseases of strawberry, namely leaf blight, leaf blotch, root rot and petiole blight, based on molecular data and morphological characters using fresh and herbarium collections. Combined analyses of four nuclear loci, 28S ribosomal DNA/large subunit rDNA (LSU), ribosomal internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2 with 5.8S ribosomal DNA (ITS), partial sequences of second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2) and translation elongation factor 1-α (TEF1), were used to reconstruct a phylogeny for these pathogens. Results confirmed that the leaf blight pathogen formerly known as Phomopsis obscurans belongs in the family Melanconiellaceae and not with Diaporthe (syn. Phomopsis) or any other known genus in the order. A new genus Paraphomopsis is introduced herein with a new combination, Paraphomopsis obscurans, to accommodate the leaf blight fungus. Gnomoniopsis fragariae comb. nov. (Gnomoniaceae), is introduced to accommodate Gnomoniopsis fructicola, the cause of leaf blotch of strawberry. Both of the fungi causing leaf blight and leaf blotch were epitypified. Fresh collections and new molecular data were incorporated for Paragnomonia fragariae (Sydowiellaceae), which causes petiole blight and root rot of strawberry and is distinct from the above taxa. An updated multilocus phylogeny for the Diaporthales is provided with representatives of currently known families.

KEYWORDS: foliar fungi, Fragaria, leaf blotch, plant pathogens, petiole blight, Sordariomycetes, one new taxon

INTRODUCTION

The order Diaporthales is one of the largest and best-defined orders in the Sordariomycetes (Castlebury et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2006; Rossman et al. 2007). The order comprises many destructive plant pathogens causing diseases on various crops, ornamental plants and forest trees, as well as numerous endophytic and saprobic fungal species (Udayanga et al. 2011, 2015; Shuttleworth and Guest 2017; Senanayake et al. 2017a; Jiang et al. 2019, 2020). It currently contains approximately 31 families supported by molecular data, with many recent additions and segregations of genera and families within the order (Castlebury et al. 2002; Lumbsch and Huhndorf 2007; Rossman et al. 2007, 2015, 2016; Yang et al. 2018; Voglmayr et al. 2017, 2019a; Jiang et al. 2020). Although the phylogenetic relationships and species composition of the majority of commonly encountered pathogenic genera are known, much work remains to be done concerning more obscure taxa from various geographic locations around the world (Zhang and Blackwell 2001; Rossman et al. 2007; Yun and Rossman 2011; Crous et al. 2012a, 2012b; Walker et al. 2012; Rossman et al. 2015).

The genus Fragaria, better known as strawberry, belongs in the plant family Rosaceae and is well known for its edible fruits (Hancock 1999). Worldwide, there are more than 25 described species, including wild species and many hybrids and cultivars (Potter et al. 2000; Staudt 2009; Zhong et al. 2018). The modern cultivated/garden strawberry, Fragaria × ananassa (Weston) Duchesne ex Rozier is one of the most important economic fruit crops worldwide (Simpson 2018). Pre- and post-harvest fungal diseases caused by various pathogens have a great impact on strawberry production, decreasing subsequent fruit yield and quality (Maas 1998; Koike et al. 2009; Xu et al. 2015; Baroncelli et al. 2015; Abdelfattah et al. 2016). Among those pathogenic fungi, three of the destructive species namely Gnomoniopsis fructicola, Paragnomonia fragariae, and Phomopsis obscurans are members of the order Diaporthales (Sordariomycetes, Ascomycota).

Among various plant pathogens, Phomopsis obscurans is known to cause leaf blight and fruit rot in most of the strawberry growing regions of the world (Plakidas 1964; Sutton 1965; Eshenaur and Milholland 1989; Maas 1998; Ellis et al. 2000; Udayanga et al. 2011). Due to the implementation of one name for pleomorphic fungi, all species formerly known as Phomopsis and phylogenetically congeneric should now be placed in the genus Diaporthe (Udayanga et al. 2012, 2014a, 2014b; Rossman et al. 2014; Gomes et al. 2013; Fan et al. 2018). However, the generic placement of the strawberry leaf blight fungus has always been subject to uncertainty.

Ellis and Everhart (1894) formally described the species causing leaf blight of Fragaria as Phoma obscurans based on a collection from West Virginia (USA). The fungus was reported from various regions of North America in subsequent studies. A severe outbreak of leaf blight was reported from Indiana in 1919 (Anderson 1920; Plakidas 1964). The causal agent of this outbreak was identified by Anderson (1920) as Dendrophoma obscurans. Sutton (1965) revisited the concept of Dendrophoma and suggested D. obscurans was not congeneric with the type species, D. cytisporoides. The type species of Dendrophoma, D. cytosporoides, belongs to the family Chaetosphaeriaceae (Chaetosphaeriales) based on available molecular data (Crous et al. 2012a). Phoma obscurans has been also known as Sphaeropsis obscurans and Phyllosticta obscurans in taxonomic literature (Kuntze 1898; Tassi 1902). However, the taxonomic affinity of P. obscurans to either Sphaeropsis or Phyllostica was unknown. Based on comparisons with representative Phomopsis species, the name Phomopsis obscurans was proposed for the leaf blight fungus, by Sutton (1965).

In 1916, Sphaeronaemella fragariae was reported to be the causal agent of “Sphaeronaemella” rot in strawberry (Stevens and Peterson 1916; Maas 1998). This species was not accepted in the mycoparasitic genus Sphaeronaemella by Malloch (1974), as a sexual morph was not known (Stevens and Peterson 1916). Hausner and Reid (2004) utilized nuc 18S rDNA sequence data of the ex-syntype isolate (CBS 118.16) of S. fragariae and confirmed it did not group with the type species of Sphaeronaemella, S. helvellae. Therefore, they considered it to be a synonym of Phomopsis obscurans in the Diaporthales. In the study by Senanayake et al. (2017a), the name Microascospora fragariae was proposed, based on S. fragariae and unauthenticated ITS sequences from an unpublished study. However, the name Phoma obscurans has since been found to be the oldest name for this fungus.

Similarly, confusion has existed among Gnomonia-like species associated with strawberry (Sogonov et al. 2008; Walker et al. 2010). The name Gnomonia comari is commonly used in older literature to refer to the fungus causing leaf blotch and fruit rot of strawberry. However, Sogonov et al. (2008) expanded the concept of Gnomoniopsis (Gnomoniaceae) to include G. comari as Gnomoniopsis comari. That same study revealed G. comari to be distinct from the causal agent of leaf blotch and petiole blight of strawberry in Europe and North America, known as Gnomoniopsis fructicola. Therefore, G. comari is now considered to be associated exclusively with Comarum palustre and not as a pathogen of strawberry.

The third diaporthalean fungus associated with strawberry, Paragnomonia fragariae, is known to cause petiole blight and root rot of perennial strawberry in Northern Europe and has been shown to be not congeneric with Gnomonia (Gnomoniaceae) based on molecular data (Moročko and Fatehi 2007). Morphologically, this species is similar to gnomoniaceous taxa with an apparently limited distribution in Europe and no known asexual morph (Moročko 2006; Moročko and Fatehi 2007). Recently, Moročko-Bičevska et al. (2019) lectotypified it based on illustrations from the original description, providing taxonomic and nomenclatural clarifications, and designating an epitype specimen from Latvia,

The aims of this study were to infer the evolutionary relationships and revise the taxonomy of diaporthalean fungi associated with strawberry utilizing fresh collections, ex-type isolates and preserved fungal specimens from herbaria. An updated multilocus phylogeny of the order diaporthales, including fungal isolates from strawberry and modern taxonomic descriptions and illustrations are provided for the fungi reassessed in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample sources and morphology

Strains of pathogenic fungi causing leaf blight of strawberry (Phomopsis obscurans) were obtained from a conventionally managed, matted-row production system at a private farm in Germantown, MD, USA (Black et al. 2002). In addition, samples were collected from two locations at the Beltsville Agriculture Research Center (USDA-ARS) in Beltsville, MD, where neither fumigants nor fungicides had been used: the Student Discovery Garden and yield-trial plots for the strawberry breeding program (Lewers et al. 2019). Pure cultures of the pathogens were isolated by single spore isolation (Udayanga et al. 2012) from leaf specimens with typical mature disease symptoms. Other fresh specimens and pure cultures were obtained from culture collections and various contributors (Table 1). Holotype and other specimens were obtained from the United States National Fungus Collections (BPI) and other herbaria.

Table 1.

Isolates and DNA sequences used in this study

| Families in Diaporthales | Culture collection/Isolate | Species | Host | Country | GenBank Accessions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSU | ITS | RPB2 | TEF1 | |||||

| Apiosporopsidaceae | CBS 771.79 | Apiosporopsis carpinea | Carpinus betulus | Switzerland | AF277130 | – | – | – |

| Apoharknessiaceae | CBS 111377* | Apoharknessia insueta | Eucalyptus pellita | Brazil | AY720814 | JQ706083 | – | MN271820 |

| – | CBS 114575 | Apoharknessia insueta | Eucalyptus sp. | Colombia | MN172370 | MN172402 | – | MN271821 |

| Asterosporiaceae | MFLU 15–3555 | Asterosporium asterospoermum | Fagus sylvatica | Italy | MF190062 | – | – | – |

| Auratiopycnidiellaceae | CBS 132180*/ CPC 16371 | Auratiopycnidiella tristaniopsis | Tristaniopsis laurina | Australia: New South Wales | JQ685522 | JQ685516 | – | MN271825 |

| – | CPC 16371 | Auratiopycnidiella tristaniopsis | Tristaniopsis laurina | Australia: New South Wales | MN172374 | MN172405 | – | MN271826 |

| Coryneaceae | D201 | Coryneum umbonatum | Quercus robur | Austria | MH674329 | MH674329 | MH674333 | MH674337 |

| – | CFCC 52319/isolate 89–1* | Coryneum gigasporum | Castanea mollissima | China | MH683557 | MH683565 | – | – |

| Cryphonectriaceae (subclade1) | ATCC 38755 | Cryphonectria parasitica | Castanea dentata | USA | NG_027589 | AY141856 | DQ862017 | EU222014 |

| – | ATCC 48198/CMW7048 | Cryphonectria parasitica | Quercus virginiana | USA | JN940858 | JN942325 | – | – |

| – | CFCC 52150 | Cryphonectria parasitica | Castanea mollissima | China | MH514021 | MG866018 | – | MN271848 |

| Cryphonectriaceae (subclade2) | CBS 112916*/CMW62/CRY-98 | Chrysoporthe australafricana | Eucalyptus grandis | South Africa | AY194097 | AF292041 | – | MN271832 |

| – | CBS 118654* | Chrysoporthe cubensis | Eucalyptus grandis | Cuba | MN172378 | DQ368773 | – | MN271834 |

| Cytosporaceae | CFCC 89982* | Cytospora chrysosperma | Ulmus pumila | China | KP310805 | KP281261 | KU710952 | KP310848 |

| – | CFCC 89633 | Cytospora eleagni | Elaeagnus angustifolia | China | KF765693 | KF765677 | KU710956 | KU710919 |

| – | CBS 202.36* | Cytospora viridistroma | Cercis canadensis | Georgia | MN172388 | MN172408 | – | MN271853 |

| Diaporthaceae | AR 3405*/CBS 135422 | Diaporthe citri | Citrus sp. | USA | MT378365 | KC843311 | MT383081 | KC843071 |

| – | AR 4855 | Diaporthe novem | Lactuca muralis | France | MT378366 | MT378351 | MT383082 | MT383100 |

| – | CBS 592.81* | Diaporthe helianthi | Helianthus annuus | Serbia | MT378370 | NR_103698 | – | KC343841 |

| – | CBS 138594/AR 5193* | Diaporthe eres | Ulmus sp. | Germany | MT378367 | KJ210529 | MT383083 | KJ210550 |

| – | CBS 125529/AR 4658 | Mazzantia galii | Galium aparine | France | MH875041 | MH863563 | – | MT383101 |

| Diaporthosporellaceae | CBS 140348* | Diaporthella cryptica | Corylus avellana | Italy | MN172390 | MN172409 | MN271800 | MN271854 |

| – | CFCC 51994* | Diaporthosporella cercidicola | Cercis chinensis | China | KY852515 | KY852492 | – | MN271855 |

| Diaporthostomataceae | CFCC 52101 | Diaporthostoma machili | Machilus leptophylla | China | MG682021 | MG682081 | MG682041 | MG682061 |

| – | CFCC 52100* | Diaporthostoma machili | Machilus leptophylla | China | MG682020 | MG682080 | MG682040 | MG682060 |

| Dwiroopaceae | CBS 109755* | Dwiroopa lythri | Lythrum salicaria | USA | MN172389 | MN172410 | MN271801 | MN271859 |

| – | CBS 143163* | Dwiroopa punicae | Punica granatum var. azadi | USA:Minnesota | MK510686 | MK510676 | MK510692 | – |

| Erythrogloeaceae | CBS 132185*/CPC 18819 | Erythrogloeum hymenaeae | Hymenaea courbaril | Brazil | JQ685525 | JQ685519 | – | – |

| – | CFCC 52106* | Dendrostoma osmanthi | Osmanthus fragrans | China | MG682013 | MG682073 | MG682033 | MG682053 |

| Folicryphiaceae | CFCC 53025* | Neocryphonectria chinensis | Carpinus turczaninowii | China | MN172397 | MN172414 | MN271812 | MN271893 |

| – | CFCC 53027*/CFCC 53027 | Neocryphonectria carpini | Carpinus turczaninowi | China | MN172396 | MN172413 | – | – |

| Gnomoniaceae | DMW 108/CBS 128442 | Ophiognomonia rosae | Fragaria vesca | USA | MT378355 | JF514851 | MT383086 | JF514824 |

| – | CBS 851.79 | Ophiognomonia rosae | Comarum palustre | Finland | MT378356 | EU254930 | MT383071 | JQ414153 |

| – | CBS 121226/AR4275* | Gnomoniopsis fragariae | Fragaria vesca | USA | EU255115 | EU254824 | EU219250 | EU221961 |

| – | DMW 63 | Gnomoniopsis fragariae | Fragaria × ananassa | USA | MT378357 | MT378343 | MT383072 | MT383089 |

| – | DMW 61 | Gnomoniopsis fragariae | Fragaria sp. | USA | MT378358 | MT378344 | MT383073 | MT383090 |

| – | VPRI 15547 | Gnomoniopsis fragariae | Fragaria × ananassa | Australia | MT378359 | MT378345 | MT383087 | MT383091 |

| – | CBS 275.51/ATCC 11430 | Gnomoniopsis fragariae | Fragaria sp. | Canada:Ontario | MH868373 | EU254829 | MT383088 | MT383092 |

| – | CBS 208.34 | Gnomoniopsis fragariae | Fragaria sp. | France | EU255116 | EU254826 | EU219284 | EU221968 |

| – | CBS 904.79 | Gnomoniopsis tormentillae | Potentilla erecta | Switzerland | EU255133 | EU254856 | – | GU320795 |

| – | CBS 806.79 | Gnomoniopsis comari | Comarum palustre | Finland | EU255114 | EU254821 | – | GU320810 |

| Harknessiaceae | CBS 120033*/CFCC 53027 | Harknessia gibbosa | Eucalyptus delegatensis | Tasmania | EF110615 | EF110615 | – | MN271868 |

| – | CBS 120030* | Harknessia ipereniae | Eucalyptus sp. | Western Australia | EF110614 | EF110614 | – | MN271870 |

| Juglanconidaceae | MAFF 410216 | Juglanconis oblonga | Juglans ailanthifolia | Japan | KY427153 | KY427153 | KY427203 | KY427222 |

| – | CBS 121083 | Juglanconis juglandina | Juglans regia | Austria | KY427148 | KY427148 | KY427198 | KY427217 |

| – | MAFF 410079* | Juglanconis pterocaryae | Pterocarya rhoifolia | Japan | KY427155 | KY427155 | KY427205 | KY427224 |

| Lamproconiaceae | MFLUCC 15–0870 | Lamproconium desmazieri | Tilia tomentosa | Russia | KX430135 | KX430134 | MF377605 | MF377591 |

| – | MFLUCC 15–0872 | Lamproconium desmazieri | Tilia cordata | Russia | KX430139 | KX430138 | – | MF377593 |

| Macrohilaceae | CBS 140063* | Macrohilum eucalypti | Eucalyptus piperita | Australia | NG_058183 | NR_154184 | MN271810 | – |

| – | CPC 10945 | Macrohilum eucalypti | Eucalyptus sp. | New Zealand | DQ195793 | DQ195781 | – | – |

| Mastigosporellaceae | VIC44383*/COAD 2370 | Mastigosporella pigmentata | Qualea parviflora | Brazil | MG587928 | MG587929 | – | – |

| – | CBS 136421* | Mastigosporella anisophylleae | Anisophyllea sp. | Zambia | KF777221 | KF779492 | – | MN271892 |

| Melanconidaceae | CFCC 50474 | Melanconis itoana | Betula albosinensis | China | KT732974 | KT732955 | KT732987 | KT733004 |

| – | CFCC 50475* | Melanconis stilbostoma | Betula platyphylla | China | KT732975 | KT732956 | KT732988 | KT733005 |

| – | CFCC 50471 | Melanconis betulae | Betula albosinensis | China | KT732971 | KT732952 | KT732984 | KT733001 |

| Melanconiellaceae | AU01 | Greeneria uvicola | Vitis vinifera | Australia | JN547720 | – | – | – |

| – | OH35 | Greeneria uvicola | Vitis labrusca | Ohio | AF362570 | – | – | – |

| – | AR 3457 | Melanconiella spodiaea | Carpinus betulus | Austria | AF408369 | MT378352 | MT383074 | MT383093 |

| – | AR 3462 | Melanconiella spodiaea | Carpinus betulus | Austria | AF408370 | MT378353 | MT383075 | MT383094 |

| – | AR 3830/CBS 131494 | Melanconiella elegans | Carpinus caroliniana | USA | JQ926264 | JQ926264 | JQ926335 | JQ926401 |

| – | CBS 125597 | Melanconiella chrysodiscosporina | Carpinus betulus | Austria | MH875191 | MH863730 | – | – |

| – | BPI 878343 | Melanconiella ellisii | Carpinus caroliniana | USA | JQ926271 | JQ926271 | JQ926339 | JQ926406 |

| – | MFLU 15–1112* | Microascospora rubi | Rubus ulmifolius | Italy | MF190099 | MF190154 | MF377611 | MF377582 |

| – | MFLU 17–0883 | Microascospora rubi | Rubus ulmifolius | Italy | MF190098 | MF190153 | – | MF377581 |

| – | M1261/DS016 | Paraphomopsis obscurans | Fragaria × ananassa | USA | MT378360 | MT378346 | MT383076 | MT383095 |

| – | CBS 143829/M1262/DS020* | Paraphomopsis obscurans | Fragaria × ananassa | USA | MT378361 | MT378347 | MT383077 | MT383096 |

| – | M1259/DS013 | Paraphomopsis obscurans | Fragaria × ananassa | USA | MT378362 | MT378348 | MT383078 | MT383097 |

| – | M1333/DS133 | Paraphomopsis obscurans | Fragaria × ananassa | USA | MT378363 | MT378349 | MT383079 | MT383098 |

| – | M1278/DS055 | Paraphomopsis obscurans | Fragaria × ananassa | USA | MT378364 | MT378350 | MT383080 | MT383099 |

| – | strain 1–1 | Paraphomopsis obscurans (as. Sphaeronaemella fragariae) | Fragaria sp. | China | – | HM854850 | – | – |

| – | strain 1–3 | Paraphomopsis obscurans (as. Sphaeronaemella fragariae) | Fragaria sp. | China | – | HM854852 | – | – |

| – | strain 12 | Paraphomopsis obscurans (as. Sphaeronaemella fragariae) | Fragaria sp. | China | – | HM854849 | – | – |

| Phaeoappendicosporaceae | MFLUCC 13–0161*/MFLU 12–2131 | Phaeoappendicospora thailandensis | Quercus sp. | Italy | MF190102 | MF190157 | – | – |

| Prosopidicolaceae | CBS 113529* | Prosopidicola mexicana | Prosopis glandulosa | USA | KX228354 | AY720709 | – | – |

| – | CBS 141298/CPC 27478* | Prosopidiocola albizziae | Albizzia falcataria | Malaysia | KX228325 | KX228274 | – | – |

| Pseudomelanconidaceae | CFCC 52787* | Neopseudomelanconis castaneae | Castanea mollissima | China | MH469164 | MH469162 | – | – |

| – | CFCC 52110* | Pseudomelanconis caryae | Carya cathayensis | China | MG682022 | MG682082 | MG682042 | MG682062 |

| Pseudoplagiostomaceae | CBS 115722/CMW 6674 | Pseudoplagiostoma oldii | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Australia | GU973610 | GU973535 | – | GU973565 |

| – | CPC 14161 | Pseudoplagiostoma eucalypti | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Vietnam | GU973604 | GU973510 | – | GU973540 |

| Schizoparmaceae | CBS 112640*/STE-U 3904 | Coniella eucalyptorum | Eucalyptus grandis × tereticornis | Queensland | AY339290 | AY339338 | KX833452 | KX833637 |

| – | CBS 110394* | Coneilla peruensis | soil in rain forest | Peru | KJ710441 | KJ710463 | KX833499 | KX833695 |

| Stilbosporaceae | CBS 122529* | Stilbospora longicornuta | Carpinus betulus | Austria | KF570164 | KF570164 | KF570194 | KF570232 |

| – | CBS 117025* | Stegonsporium acerophilum | Acer saccharum | USA: Tennessee | EU039993 | EU039982 | KF570173 | EU040027 |

| Sydowiellaceae | AR 3809 | Chapeckia nigrospora | Betula sp. | USA | EU683068 | – | – | – |

| – | F129/P3/1* | Paragnomonia fragariae | Fragaria × ananassa | Latvia | MK524447 | MK524430 | – | MK524466 |

| – | GF300/M1530 | Paragnomonia fragariae | Fragaria sp. | France | MT378368 | – | MT383084 | MT383102 |

| – | GF301/M1531 | Paragnomonia fragariae | Fragaria sp. | France | MT378369 | – | MT383085 | MT383103 |

| – | MFLU 16–2864* | Sillia karstenii | Centaurea sp. | Italy | KY523500 | KY523482 | KY501636 | – |

| Synnemasporellaceae | CFCC 52094 | Synnemasporella aculeans | Rhus chinensis | China | MG682026 | MG682086 | MG682046 | MG682066 |

| – | CFCC 52097* | Synnemasporella toxicodendri | Toxicodendron sylvestre | China | MG682029 | MG682089 | MG682049 | MG682069 |

| Tirisporellaceae | BCC 00018 | Thailandiomyces bisetulosus | Licuala longicalycata | Thailand | EF622230 | – | – | – |

| – | BCC 38312 | Tirisporella beccariana | Nypa fruticans | Thailand | JQ655449 | – | – | – |

| Tubakiaceae | CBS 129012* | Tubakia iowensis | Quercus macrocarpa | USA | MG591971 | JF704194 | – | MG603576 |

| – | CBS 127490* | Tubakia seoraksanensis | Quercus mongolica | South Korea | KP260499 | MG591907 | – | MG592094 |

| – | CBS 114386 | Tubakia dryina | Quercus robur | New Zealand | JF704188 | MG591852 | – | MG592040 |

| – | CPC 13806 | Racheliella wingfieldiana | Syzygium guineense | South Africa | MG592006 | MG591911 | MG976487 | MG592100 |

| – | CBS 189.71* | Oblongisporothyrium castanopsidis | Castanopsis cuspidata | Japan | MG591943 | MG591850 | – | MG592038 |

| – | CBS 124732 | Oblongisporothyrium castanopsidis | Castanopsis cuspidata | Japan | MG591942 | MG591849 | MG976453 | MG592037 |

| – | MUCC 2293* | Paratubakia subglobosoides | Quercus glauca | Japan | MG592010 | MG591915 | MG976491 | MG592104 |

| – | CBS 193.71* | Paratubakia subglobosa | Quercus glauca | Japan | MG592009 | MG591914 | MG976490 | MG592103 |

| – | CPC 31361 | Sphaerosporithyrium mexicanum | Quercus eduardii | Mexico | MG591988 | MG591894 | – | MG592081 |

| – | CPC 33021* | Sphaerosporithyrium mexicanum | Quercus eduardii | Mexico | MG591990 | MG591896 | MG976473 | MG592083 |

| – | MUCC 2304* | Involutiscutellula rubra | Quercus phillyraeoides | Japan | MG591995 | MG591901 | MG976478 | MG592088 |

| – | CBS 192.71* | Involutiscutellula rubra | Quercus phillyraeoides | Japan | MG591993 | MG591899 | MG976476 | MG592086 |

| Outgroup (Magnaporthales) | MFLU 18–2323*/MFLUCC 18–1337 | Ceratosphaeria aquatica | submerged wood | China | MK835812 | MK828612 | MN156509 | MN194065 |

| – | CG-4/M83* | Pyricularia grisea | Digitaria sp. | USA | JX134683 | JX134671 | – | JX134697 |

Abbreviations of the culture collections: ATCC: American Type Culture collection; CMW:FABI fungal culture collection; CBS:CBS-KNAW culture collection, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute; MFLU: Mae Fah Luang University Herbarium; MFLUCC: Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection; CFCC: China Forestry Culture Collection Center; STE-U: culture collection of the Department of Plant Pathology at the University of Stellenbosch; AR, M, DMW: Cultures housed at MNGDBL, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, Maryland; CPC: Culture collection of Pedro Crous, housed at Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute; MUCC: Murdoch University Culture Collection; BCC: BIOTEC Culture Collection, Bangkok, Thailand; VPRI: Victoria Plant Pathology Herbarium. *Ex-type/epitype/neotype cultures or specimens are indicated by asterisks. Newly generated sequences in this study are bold

Morphological descriptions were based on pycnidia or perithecia formed on inoculated alfalfa stems placed on 2% water agar (WA), as well as from type specimens. Digital images of fruiting bodies were captured using a Discovery V20 stereomicroscope and AxioCam HrC digital camera (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, New York, USA) imaging system. Whenever possible, 20–30 measurements were made of the structures mounted in 5% KOH using a Carl Zeiss Axioplan2 compound light microscope. The sample sizes are given in parentheses with mean and standard deviation. Triplicates of the cultures for each isolate were used for determining colony characters on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA), Malt Extract Agar (MEA, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and V8 juice agar (V8A) (Dhingra and Sinclair 1985) at 25 °C in indoor light. After 1 wk., and color of the colonies were recorded. The colony color codes are given within the parenthesis according to the charts by Rayner (1970). For determination of growth rates, triplicate PDA plates were inoculated with 5 mm in diam plugs of actively growing fungal cultures. Mycelial growth was measured daily along two perpendicular lines drawn at the center of the colonies and continued for two weeks. Radial growth rates were calculated and expressed in mm day− 1. Digital images were captured and cultural characteristics were observed as described in Udayanga et al. (2014a, 2014b).

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing

Mycelial scrapings (50–60 mg) from the leading edge of cultures on PDA, incubated for 4–5 d at 25 °C were harvested and lysed in tubes containing 500 μm garnet media and a 6mm zirconium bead (OPS Diagnostics, Lebanon, New Jersey) with the Fast Prep FP120 benchtop bead-beating instrument (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts) for 60 s (20 s × 3 with 10 s intervals). Genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, California) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was eluted from DNAeasy mini spin column using 50 μl of elution buffer and visualized with agarose gel electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels stained with SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon).

The nuc rDNA internal transcribed spacer ITS1–5.8S-ITS2 region (ITS), nuc 28S rRNA gene (LSU), translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF1) and second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2) gene regions were amplified on a Bio-Rad Dyad Peltier thermal cycler in a 25 μL reaction volume: 10–15 ng genomic DNA, 12.5 μL Quick load Taq 2x Master Mix (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts), 1 μL 10 mM of each primer, and nuclease-free water to adjust volumes to 25 μL. Amplification and DNA sequencing of ITS region were performed using forward and reverse primer pair ITS1 and ITS4 (White et al. 1990), as described by Udayanga et al. (2014a). Amplification of 28S ribosomal DNA region was performed using the forward and reverse primer pair LROR and LR7 (Vilgalys and Hester 1990), under the following conditions: 95 °C 5 min, (95 °C: 60 s, 55 °C: 60 s, 72 °C: 60 s) × 39 cycles, 72 °C 10 min. DNA sequencing was performed using the same PCR primers with additional internal primers LR3R and LR5 (Rehner and Samuels 1995). The RPB2 gene region was amplified using the forward and reverse primer pair, fRPB2-5F and fRPB2-7cR (Liu et al. 1999) under the following conditions: 95 °C 5 min, 95 °C 1 min, [55 °C 2 min - increase 0.2 °C per second until 72 °C (slow ramp), 72 °C 2 min] × 34 cycles, 72 °C 10 min and sequenced using the same primers. The TEF1 region was amplified and sequenced using the primer pair EF728f (Carbone and Kohn (1999) and EF2 (Rehner (2001), using a modified touchdown PCR protocol: 95 °C 5 min, [95 °C: 30 s, 66 °C: 30 s decrease 1 °C in every cycle, 72 °C: 80 s cycle to step 2] × 10 cycles [95 °C: 30 s, 56 °C 30 s, 72 °C 80 s] × 40 cycles, 72 °C 10 min.

PCR products were visualized as above. Excess primers and dNTPs were removed from PCR mixtures with ExoSAP-IT (USB Corp., Cleveland, Ohio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplicons were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York) on an Applied Biosystems 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

The newly generated raw sequences were assembled into contigs with Sequencher 5.0 for Windows (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Michigan). Additional sequences were obtained from GenBank, including ex-type or other reference sequences (Table 1). All sequence conversions and manual alignments were performed in Bioedit v.7.2.5 (Hall 1999) and CLC Sequence Viewer 7.7 (http://www.clcbio.com/products/clc-sequence-viewer/). Sequences were aligned with MAFFT v.7 using Auto (FFT-NS-1, FFT-NS-2, FFT-NS-i or L-INS-i depending on data size) strategy (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) (Katoh and Standley 2013).

Isolates were selected to represent each of the 31 known families in the Diaporthales based on the latest available literature. Each taxon selected was represented by at least an LSU sequence. In addition to fungal isolates from Fragaria, several new sequences were generated for representative taxa of the order: Ophiognomonia rosae (DMW 108, CBS 851.79), Melanconiella spodiaea (AR 3457, AR 3462), Diaporthe eres (AR 5193), D. novem (AR 4855), D. citri (AR 3405), D. helianthi (CBS 592.81) and Mazzantia galii (AR 4658). Two taxa in the Magnaporthales (Sordariomycetes), Pyricularia grisea (M83) and Ceratosphaeria aquatica (MFLU18–2323), were used as outgroup taxa in the phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic reconstructions of concatenated and individual gene regions were performed using Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) (Felsenstein 1981; Huelsenbeck et al. 2001). Individual datasets were tested for congruency using the 70% reciprocal bootstrap (BS) threshold method as described by Gueidan et al. (2007). ML gene trees were estimated using the software RAxML 8.2.8 Black Box (Stamatakis 2006; Stamatakis et al. 2008) in the CIPRES Science Gateway platform (Miller et al. 2010). For the concatenated dataset, all free-modal parameters were estimated by RAxML with an ML estimate of 25 per site rate categories. The concatenated dataset was partitioned by locus and the gaps were treated as missing data. The RAxML analysis utilized the GTRCAT model of nucleotide substitution with the additional options of modeling rate heterogeneity (G) and proportion invariable sites (I).

Bayesian analysis was performed using MrBayes v. 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001) and substitution models were determined in MrModeltest v. 2.3 (Nylander 2004). Bayesian reconstructions were performed using MrBayes 3.1.2. Six simultaneous Markov chains were run for 1,000,000 generations and trees were sampled every 100 generations, resulting in 10,000 total trees. The first 25% of the trees, representing the burn-in phase of the analyses, were discarded, and the remaining trees were used for calculating posterior probabilities (PP) in the majority rule consensus tree. Trees were visualized in FigTree v. 1.4.4 (Rambaut 2018). The DNA sequence alignments, single gene and combined trees were deposited in the USDA AgData Commons: 10.15482/USDA.ADC/1518737.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analyses, limits and boundaries of genera and families

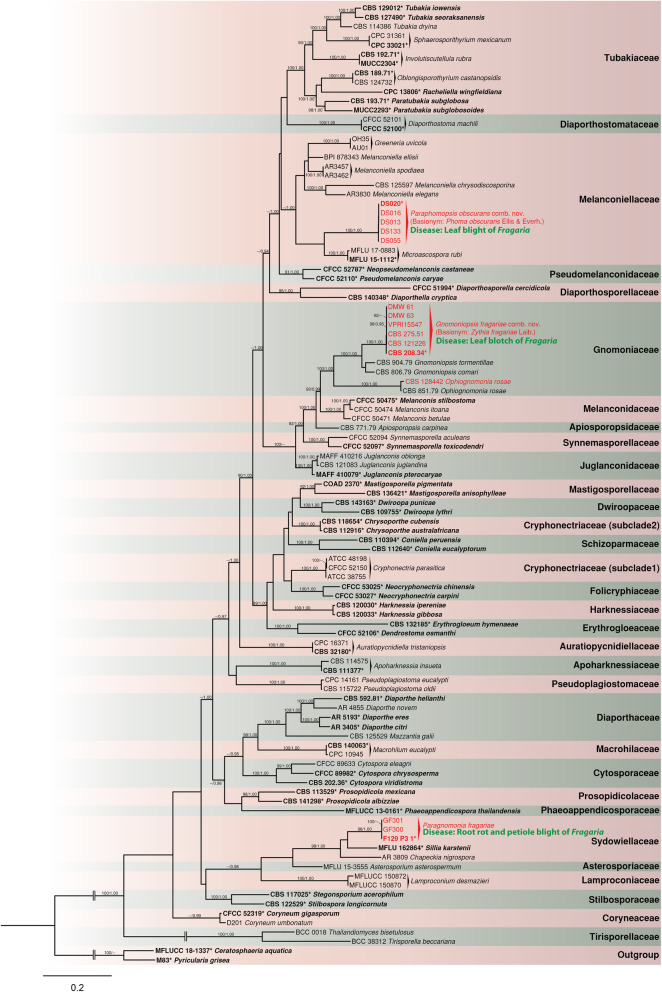

In total, 60 new DNA sequences were generated in this study. The approximate sizes of the target fragments of ITS, LSU, RPB2 and TEF1 were observed to be 600 bp, 1200 bp, 1000 bp and 650 bp, respectively. The remaining sequences were downloaded from GenBank (Table 1). Each gene region was aligned individually before concatenation in a sequence alignment consisting of 103 taxa representing 48 genera in 31 families of Diaporthales, including the isolates of fungi associated with Fragaria obtained in this study. The final combined four gene alignment consisted of 3899 total characters including gaps. Each taxon is represented by at least the LSU sequence. The ML tree resulting from the RAxML analysis had a final ML Optimization Likelihood of − 61,871.952114 and the following model parameters: alpha = 0.344711, pi(A) = 0.239113, pi(C) = 0.263167, pi(G) = 0.271106, and pi(T) = 0.226613. This tree was used to represent the phylogeny of the order Diaporthales (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ML tree generated based on combined LSU, ITS, RPB2, and TEF1 alignment of representative taxa in the order Diaporthales. Isolates from Fragaria are indicated in red. Ex-type/epitype isolates are in bold and marked with asterisk (*). The ML bootstrap values/Bayesian PP greater than 90% /0.90 are indicated above or below the respective branches. The tree is rooted with Pyricularia grisea (M83) and Ceratosphaeria aquatica (MFLU 18–2323) (Magnaporthaceae, Magnaporthales)

The phylogeny inferred from the combined analysis of four loci resolved deeper nodes where confusion has remained at familial and generic boundaries when using only LSU data or other single gene regions (trees available at 10.15482/USDA.ADC/1518737). Major monophyletic groups representing families and genera were resolved with well-supported branches. Both BI and ML trees resolved the 31 families and 48 genera including the new genus described herein.

Multilocus phylogeny generated in this study placed the Fragaria isolates in the Melanconiellaceae, Sydowiellaceae and Gnomoniaceae. Based on the combined analysis, we determined that the isolates from strawberry causing leaf blight known to date as Phomopsis obscurans, are distinct from their closest relatives classified in Melanconiella, Microascospora or Greeneria. Therefore, a new genus Paraphomopsis is described below to accommodate the species formerly known as Phomopsis obscurans. The combined analysis further revealed that Paraphomopsis obscurans appears to be a sister taxon to Microascospora rubi, the type species of Microascospora. However, in the LSU and TEF1 single gene analyses, Microascospora rubi and Paraphomopsis obscurans were found to be non-monophyletic, and they were diverged based on ITS and RPB2 single gene trees. The ML bootstrap and BPP values for the node that groups Microascospora rubi and Paraphomopsis obscurans in the combined analysis were 65% and 0.68, respectively (≤90%/0.90, not shown in Fig. 1). Therefore, the taxa were not considered to be congeneric based on combined phylogeny. The three representative ITS sequences (HM854850, HM854852, HM854849), used by Senanayake et al. (2017a) to propose the name Microascopora fragariae (synonymized under Paraphomopsis obscurans below) were not included in the analyses due to lack of LSU sequences for those isolates. However, the ITS sequences for these isolates were 100% identical with the isolates of Paraphomopsis obscurans generated for this study.

The leaf blotch pathogen of strawberry, Gnomoniopsis fructicola, is currently placed in Gnomoniaceae with new molecular data from multiple isolates. The genus Gnomoniopsis (including syn. Sirococcus) represents a basal lineage to the rest of the genera in Gnomoniaceae, which contains the genera Gnomonia, Plagiostoma, Cryptodiaporthe, Apiognomonia, Discula, Cryptosporella, Ophiognomonia and Anisogramma. However, to preserve the historical concept of the widely accepted family Gnomoniaceae, which includes the major non-stromatic lineages in the Diaporthales, it is considered as a diverse single taxonomic entity with the assumption that intermediate genera in this family remain to be discovered. The closest family Melanconidaceae is clearly distinct from Gnomoniaceae. The new sequences generated for the fresh collection of the petiole blight and root rot pathogen, placed it within the Sydowiellaceae and conspecific with the recently designated epitype of Paragnomonia fragariae (F129/P3/1) with high ML bootstrap and BPP.

Taxonomy

Based on the molecular phylogenetic assessment of the order we introduce a new genus and combination to accommodate the strawberry leaf blight fungus, with lecto- and epitypification of the taxon. A new combination is introduced for Gnomoniopsis fructicola, with lecto- and epitypification providing a revision of synonyms. The remaining strawberry isolates collected in this study belonged to Paragnomonia fragrariae, for which we provide a description based on fresh collections from France.

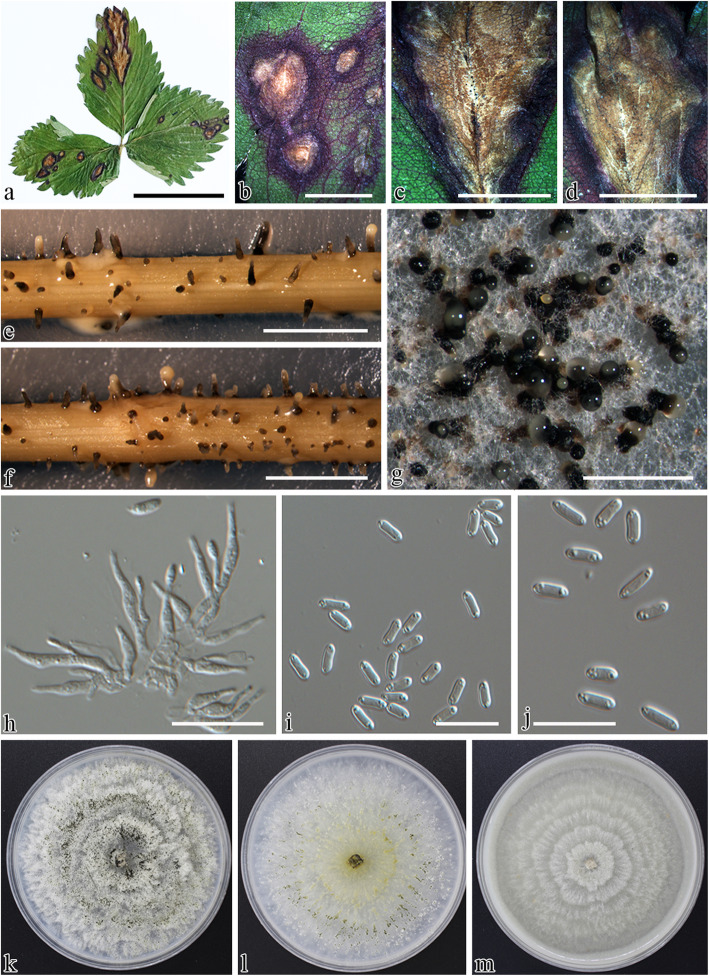

Paraphomopsis Udayanga & Castl., gen. nov. Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Morphology of Paraphomopsis obscurans (BPI 919201, culture CBS 143829/M1262, isolate DS020). a Infected leaf of Fragaria × ananassa. b–d Leaf blight symptoms under stereo microscope. e,f Pycnidia on alfalfa stems on WA. g Pycnidia on PDA. h Conidiophores. i,j Conidia. k 7-d-old culture on PDA. l 7-d-old culture on MEA. m 7-d-old culture on V8A. Scale bars: a = 4 cm, b = 1.5 cm, c,d = 1 cm, e-g = 300 μm, h-j = 10 μm

MycoBank: MB 835529.

Type species: Paraphomopsis obscurans (Ellis & Everh.) Udayanga & Castl.

Etymology: Morphologically similar to the well-known asexual morph Phomopsis (curr. name Diaporthe), but phylogenetically distinct.

Description: Asexual morph coelomycetous. Pycnidia globose, ostiolate, embedded in tissue, erumpent at maturity, with a slightly elongated, black neck, wider towards the apex at maturity; walls parenchymatous, consisting of 3–4 layers of medium brown textura angularis. Conidiophores hyaline, smooth, branched, ampulliform, long, slender, wider at the base, Conidiogenous cells phialidic, cylindrical, terminal, slightly tapering towards apex, alpha conidia aseptate, hyaline, smooth, ellipsoidal to fusiform, often biguttulate, rarely multiguttulate with minute particles aggregated towards the ends, base subtruncate. Sexual morph unknown.

Notes: Paraphomopsis can be distinguished from its closely related genera (Greeneria, Melanconiella, Microascopsora) in Melanconiellaceae based on both molecular phylogeny and morphology. The genus Paraphomopsis is morphologically described herein, exclusively based on the characters of the asexual morph. The asexual morph of Melanconiella usually consists of both dark brown melanconium-like conidia as well as hyaline discosporina-like conidia (Voglmayr et al. 2012). Similarly, the genus Greeneria, which is typified by G. uvicola, forms pale brown conidia, smooth, variously shaped ranging from fusiform, oval, to ellipsoidal, each with a truncate base and obtuse to bluntly pointed apex (Farr et al. 2001). In Paraphomopsis, although the appearance of conidia is superficially similar to Diaporthe (syn. Phomopsis), micropscopic examination revealed that the shape and overall appearance are distinct from those in Diaporthe species. In general, conidia of Paraphomopsis are fusiform with minute guttules toward the end of the conidia, whereas most Diaporthe species form ovate to clavate conidia with no or prominent biguttulate or multiguttulate conidia. The morphology of sexual morph of the new genus described here remains unknown and is not available for comparison with other closely related genera. Although, the genus Paraphomopsis represents a sister clade to Microascopora in the phylogeny presented (Fig. 1), the asexual morph of the latter remains undetermined. The sexual morph of Microascospora distinct from other genera in the same family having immersed, solitary ascomata with narrow papilla with smaller hyaline, aseptate ascospores bearing long appendages (Senanayake et al. 2017a, 2017b). However, the sexual morph of the saprobic genus Melanconiella is identified by its inconspicuous ectostroma projecting above the substrate and the hyaline, yellow or brown ascopsores, with or without short, blunt appendages and occasionally with a thin gelatinous sheath (Voglmayr et al. 2012; Senanayake et al. 2017a, 2017b).

Paraphomopsis obscurans (Ellis & Everh.) Udayanga & Castl. comb. nov. Fig. 2.

MycoBank: MB 835530.

Basionym: Phoma obscurans Ellis & Everh., Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phil. 46: 357. 1894.

≡ Sphaeropsis obscurans (Ellis & Everh.) Kuntze, Revis. gen. pl. (Leipzig) 3(2): 1–576. 1898.

≡ Phyllosticta obscurans (Ellis & Everh.) Tassi, Bulletin Labor. Orto Bot. de R. Univ. Siena 5: 13. 1902.

≡ Dendrophoma obscurans (Ellis & Everh.) H.W. Anderson, University of Illinois Agricultural Experiment Station Bull. 229: 135. 1920.

≡ Phomopsis obscurans (Ellis & Everh.) B. Sutton, Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 48(4): 615. 1965.

= Sphaeronaemella fragariae F. Stevens & Peterson, Phytopathology 6: 258. 1916.

≡ Microascospora fragariae (F. Stevens & Peterson) Senan., Maharachch. & K.D. Hyde, Stud. Mycol. 86: 279. 2017.

Type: USA. WEST VIRGINIA: Fayette Co., on leaves of Fragaria sp., 08 July 1894, Nutall LW (1600 (7620) (J.B. Ellis 554)), (Lectotype designated here BPI 521547; MBT393834); ibid. (Iso-lectotype designated here, BPI 357247; MBT 393835); USA. MARYLAND: Beltsville Agriculture Research Center, Beltsville, on leaves of Fragaria × ananassa, 21 May 2015, Udayanga D. DS020, (Epitype designated here, BPI 919201; MBT 393833, ex-epitype culture M1262 = CBS 143829). GenBank: ITS = MT378347; LSU = MT378361; TEF1 = MT383096; RPB2 = MT383077.

Description: Pycnidia on alfalfa stems on WA: globose, ostiolate, scattered over the substrate, 40–55 μm diam, embedded in tissue, erumpent at maturity, with a slightly elongated, black neck 60–100 μm high, wider towards the apex at maturity, often with a yellowish, conidial cirrus extruding from ostiole; walls parenchymatous, consisting of 3–4 layers of medium brown textura angularis. Conidiophores hyaline, smooth, branched, ampulliform, long, slender, wider at the base, 9–12 μm long and wide. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, cylindrical, terminal, slightly tapering towards apex, 1.5–2.5 μm diam at the widest point. Collarette present and conspicuous. Paraphyses absent. Alpha conidia 5–7 × 1.5–2.2 μm (avg. ± SD = 6 ± 0.5 × 2 ± 0.2, n = 30), abundant in culture and on alfalfa stems, aseptate, hyaline, smooth, ellipsoidal to fusiform, often biguttulate and rarely multiple guttules and confined to minute particles clumped towards the vertices of the spore, base subtruncate. Beta conidia unknown.

Culture on PDA under artificial light at 25 °C for 1 wk., growth rate: 4.5 ± 0.2 mm/day (n = 3), white, sparse aerial mycelium, with pale olivaceous grey (120) pigmentation and abundant sporulation with aging, olivaceous grey (107) pigmentation developing in reverse.

Additional specimens examined: USA. MARYLAND: Beltsville Agriculture Research Center, Beltsville, on leaves of Fragaria × ananassa, 22 May 2015, Udayanga D. DS013 (BPI 919179), living culture M1259; ibid, 19 June 2015, Udayanga D. DS021, June 082015 DS134 (BPI 19204); ibid, DS016 (BPI 919180), living culture M1261; ibid, Greenhouses at Beltsville Agriculture Research Centre, Beltsville, on leaves of Fragaria × ananassa, 29 Sept. 2015, Udayanga D. GR002 (BPI 919182); ibid, Davis Mill Road, Germantown (Montgomery County), on leaves of Fragaria × ananassa ‘Darselect’, 24 June 2015, Butler B. DS053 (BPI 919185) living culture M1276; ibid, Davis Mill Road, Germantown (Montgomery County), on leaves of Fragaria × ananassa ‘Darselect’, 12 Oct. 2016, Butler B. DS090 (BPI 919192).

Geographic distribution: Australia (Cook and Dubé 1989; Shivas 1989; Cunnington 2003), Brazil (Mendes et al. 1998), Brunei Darussalam (Peregrine and Bin Ahmad 1982), Bulgaria (Bobev 2009), China (Jinping 2011; Shi et al. 2013), Egypt (Haggag 2009; Abd-El-Kareem et al. 2019), Malawi (Peregrine and Siddiqi 1972), Myanmar (Thaung 2008), South Africa (Crous et al. 2000), Tonga (Dingley et al. 1981), USA: Florida, Maryland, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Washington, West Virginia (Alfieri Jr et al. 1984; Cash 1953; Shaw 1973; Maas 1998; Farr and Rossman 2020).

Notes: Although the appearance of conidia is superficially similar to Phomopsis (Syn. Diaporthe), microscopic examination revealed that the shape and overall appearance of guttules are distinct from those in Diaporthe species. In general, conidia of Paraphomopsis obscurans are fusiform with minute guttules toward the end of the conidia, whereas most Diaporthe species bear ovate to clavate conidia with no or prominent biguttulate or multiguttulate conidia. Paraphomopsis obscurans can be distinguished from the closely related species Microascospora rubi and other genera in the family Melanconiellaceae based on its morphology and robust support of the multilocus phylogeny. Due to confusion of nomenclature and taxonomy, previous records of the pathogen from various geographic locations were linked to multiple names: Phoma obscurans, Sphaeronaemella fragariae and Phomopsis obscurans, or misidentified as Gnomonia fragariae, Gnomonia comari and Gnomoniopsis fragariae. Therefore, the actual distribution of the fungus may be largely underestimated.

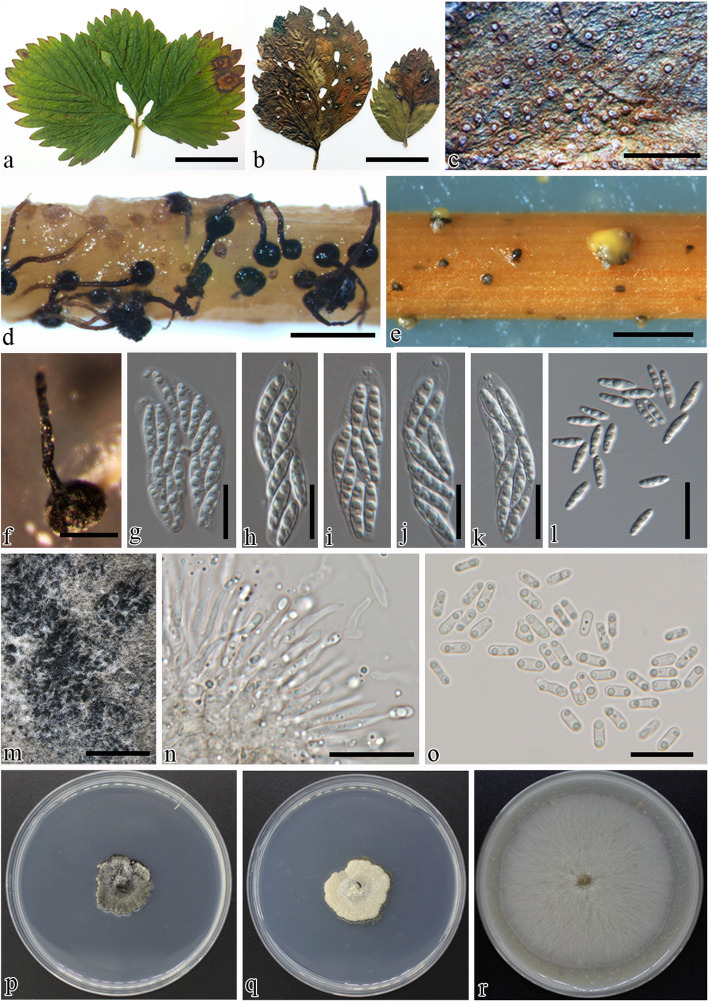

Gnomoniopsis fragariae (Laib.) Udayanga & Castl. comb. nov. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Morphology of Gnomoniopsis fragariae (BPI 877447, CBS 121226). a,b Infected leaves of Fragaria sp.. c Pycnidia on leaf surface. d Perithecia on alfalfa stems on WA. e Pycnidia on alfalfa stems on WA. f Single perithecium on WA. g–k Asci l Ascospores. m Pycnidia on culture. n Conidiophores. o Conidia. p 7-d-old culture on PDA. q 7-d-old culture on MEA. r 7-d-old culture on V8A. Scale bars: a,b = 3 cm, c = 300 μm, d,e = 800 μm, f = 200 μm, g-l = 10 μm, m = 600 μm, n = 15 μm, o = 12 μm

MycoBank: MB 835531.

Basionym: Zythia fragariae Laib., Arb. K. biol. Anst. f. Land-u-Forstwirt 6: 79–80. 1908.

= Gnomonia fragariae f. fructicola G. Arnaud, Traite de Pathologie Vegetale Encyclopedie Mycologique (Paris): 1558. 1931.

≡ Gnomonia fructicola (G. Arnaud) Fall, Can. J. Bot. 29: 309. 1951.

≡ Gnomoniopsis fructicola (G. Arnaud) Sogonov, Stud. Mycol. 62: 47. 2008.

= Gloeosporium fragariae G. Arnaud, Traite de Pathologie Vegetale Encyclopedie Mycologique (Paris): 1558. 1931.

= Phyllosticta grandimaculans Bubák & Krieg., in Bubák, Annls mycol. 10(1): 46. 1912.

Type: Illustration Abb. 3, page 80 (as Zythia fragariae) in Laibach (1908) Arbeiten aus der Kaiserlichen Biologischen Anstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft 6: 80 (Lectotype designated here; MBT 393837), Digitized by Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg (UB Frankfurt am Main) and accessed here on 16 September 2020: http://www.digizeitschriften.de/dms/resolveppn/?PID=urn:nbn:de:hebis:30:4-16524, Image 114: Page 80). USA. MARYLAND: Beltsville, May 2006, Turechek (Epitype designated here BPI 877447, MBT 393837; ex-epitype culture AR 4275 = CBS 121226). GenBank: ITS = EU254824, LSU = EU255115, TEF1 = EU221961, RPB2 = EU219250.

Description: Perithecia on alfalfa stems black, solitary, superficial on substrate, globose, 200–250 μm diam, with long tapering neck co-occurring on stems and on WA with pycnidia together, multiple tapering perithecial necks protruding through substrata, 400–500 × 20–25 μm. Asci 29–33 × 6–9 μm (avg. ± SD = 31 ± 2 × 7 ± 1.5, n = 30), unitunicate, 8-spored, arranged obliquely uniseriate, irregularly biseriate or irregularly multiseriate, sessile or freely arranged, elongate to clavate, with conspicuous refractive ring at the apex. Ascospores 7–10 × 1.9–2.6 μm (avg. ± SD = 8.7 ± 0.7 × 2. 3 ± 0.2), hyaline, fusiform, one septate or bicellular, constricted at septum, 4-guttulate, and one cell is slightly smaller than the other.

Pycnidia on alfalfa stems on WA, globose, black, ostiolate, solitary, 50–100 μm diam, embedded in tissue, erumpent at maturity, with a short or inconspicuous neck, often with a yellowish, conidial cirrus extruding from ostiole; walls parenchymatous, consisting of 2–3 layers of medium brown textura angularis. Conidiophores 8–17 × 1–2.5 (avg. ± SD = 12 ± 2.5 × 2 ± 0.4), hyaline, smooth, unbranched or rarely branched at the base, ampulliform, long, slender and wider at the base. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, cylindrical, terminal, slightly tapering towards apex, 7–9 μm diam. Paraphyses absent. Alpha conidia 5.8–6.5 × 1.9–2.5 (avg. ± SD = 6 ± 0.4 × 2.2 ± 0.2), abundant in culture and on alfalfa stems, aseptate, hyaline, smooth, ellipsoidal to ovoid, biguttulate, base subtruncate, Beta conidia unknown.

Culture on PDA under artificial light at 25 °C for 1 wk., growth rate: 2.5 ± 0.2 mm/day (n = 3) white with irregular margins, in center with aggregations of mouse grey (118) crust like aerial mycelia with age or readily sporulating with yellow conidial cirri on black perithecia, dark mouse grey (119) pigmentation developing in reverse.

Additional specimens examined: FRANCE: Yvelines (formerly Seine-et-Oise), Chevreuse, on Fragaria sp., (date unknown), culture deposited 1934, G. Arnaud (CBS 208.34). Type of Phyllosticta grandimaculans: GERMANY: Sachsen, Königstein, on leaves of Fragaria sp., 1906–1912; W. Krieger, Krieger, Fungi Saxon. Exs. nr. 2179, (Krypto-S, F48606 Lectotype for P. grandimaculans designated here), ibid. (isotypes CUP, BPI 352482); DENMARK: Rindsholm, on leaves of Fragaria sp., 11 Oct. 1904, Lind J (BPI 352477).

Geographic distribution: Australia (Gomez et al. 2017), Belgium (Sogonov et al. 2008; Walker et al. 2010), Canada: British Columbia (Sogonov et al. 2008), China (Tai 1979); Denmark (this study), France (Sogonov et al. 2008; Walker et al. 2010), Germany (this study) Switzerland (Walker et al. 2010), Taiwan (Anonymous 1979), USA: Maryland, New York, Michigan (Alexopoulos and Cation 1952; Sogonov et al. 2008; Walker et al. 2010; Farr and Rossman 2020).

Notes: The name of the leaf blotch fungus was documented in phytopathological literature as Gnomonia comari (syn. Gnomoniopsis comari) before Sogonov et al. (2008) identified it as Gnomoniopsis fructicola. However, the earlier name Zythia fragariae (1908) represents the oldest name for this taxon as the asexual state of G. fructicola (Fall 1951). Although Arnaud (1931) identified the asexual state as a Gloeosporium sp., Fall (1951) mentions it as identical to Z. fragariae. Attempts to find type material for Zythia fragariae in European herbaria were unsuccessful. Therefore, the illustration available from the protologue is designated as a lectotype herein with a modern epitype designated. Microscopic observation of the isotype specimens of Phyllosticta grandimaculans housed in BPI, S and CUP and comparison of symptoms revealed that this species is conspecific with Gnomoniopsis fragariae. This pathogen appears to occur both in Europe and North America and is commonly associated with cultivated and wild species and varieties of Fragaria (Bolton 1954; van Adrichem and Bosher 1958; Maas 1998).

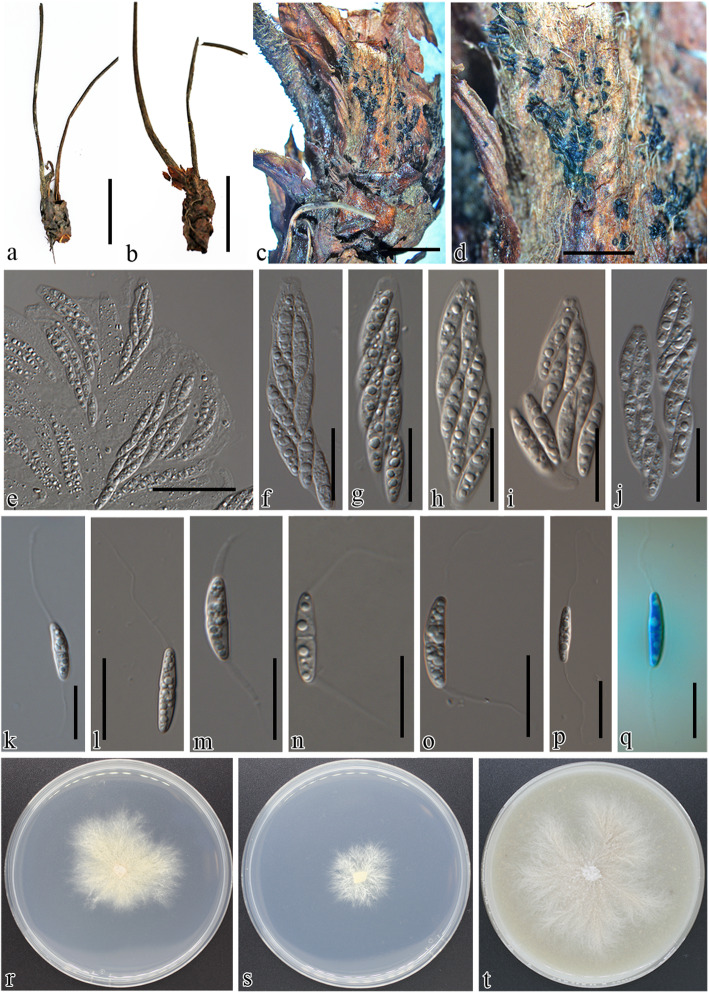

Paragnomonia fragariae (Kleb.) Senan. & K.D. Hyde, Mycosphere 8: 199. 2017. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Morphology of Paragnomonia fragariae AG16076 (BPI 919211 and living culture CBS 143831). a-d Infected petioles of Fragaria sp. e-j Asci k-q Ascospores. r 7-d-old cultures on PDA. s 7-d-old cultures on MEA. t 7-d-old cultures on V8A. Scale bars: a, b = 2 cm, c,d = 1000 μm, e = 30 μm, f-j = 16 μm, k,p,q = 18 μm, l–o = 20 μm

Basionym: Gnomonia fragariae Kleb., Haupt- und Nebenfruchtformen der Askomyzeten: Eine Darstellung eigener und der in der Literatur niedergelegten Beobachtungen über die Zusammenhänge zwischen Schlauchfrüchten und Konidienfruchtformen. 1: 285. 1918.

Type: Illustration Abb. 205, page 286., in H. Klebahn, Haupt-und Nebenfruchtformen der Askomyzeten: Eine Darstellung eigener und der in der Literatur niedergelegten Beobachtungenüber die Zusammenhänge zwischen Schlauchfrüchten und Konidienfruchtformen. 1918 (Lectotype designated by Moročko-Bičevska et al. (2019); Latvia: Tukums, Pūre, on dead petioles of Fragaria × ananassa, Lat: 57.0323418, Lon: 22.9160658, 20 Oct 2013, I. Moroĉko-Biĉevska & J. Fatehi F129 [Epitype F367871(S); Iso-epitype DAU100004631 (DAU); ex-epitype culture F129/P3/1 = MSCL1603. ITS = MK524430, LSU = MK524447, TEF1 = MK524466].

Description: Perithecia on crown and petioles of Fragaria, non stromatal, black, globose, arranged in immersed clusters on the base of the crown or solitary on petioles of the infected plants, 200–300 μm diam, bearing tapering black perithecial necks protruding from infected tissue 130–150 × 20–25 μm. Asci 50–60 × 8–10 (avg. ± SD = 56 ± 4 × 9 ± 1) μm unitunicate, 8-spored, sessile on defined hymenium or freely arranged with aging, elongate to clavate with conspicuous refractive ring at the terminals. Ascospores 14–17 × 3.5–5 (avg. ± SD = 16 ± 1.3 × 4 ± 0.4) μm, hyaline, fusiform to ellipsoid, straight to slightly curved, one septate or bicellular, with a conspicuous septum, slightly constricted at the septum, often 4-guttulate, two mucilaginous appendages present at the either ends of the ascospores. Asexual morph not seen in culture.

Culture on PDA under artificial light at 25 °C for 1 wk., growth rate: 2.8 ± 0.2 mm/day (n = 3) white, with sparse aerial mycelium, with irregular margins, rhizoid form of growth and in center and at edges with grayish yellow (57) pigmentation with age, dull green (70) pigmentation developing in reverse.

Geographic distribution: Confirmed distribution in Germany: Hamburg (Klebahn 1918), Switzerland:Vaud, Les Barges, Valais, Tessin (Bolay 1971; Monod 1983), United Kingdom, Latvia (all across the country), Sweden:Uppsala, Vastra (Moročko 2006; Moročko 2006), Lithuania:Kaunas, Siauliai and Finland: Parainen (Moročko-Bičevska et al. 2019), France (in this study).

Additional specimens examined: FRANCE: Côte-d’Or, Fontaine-Française, Le Revers des Lochères, on Fragaria sp. (cultivated), 20 May 2016, Alain Gardiennet AG16076 (BPI 919211), GF 300 = M1530 = CBS 143831; Véronnes, 14 rue Roulette, on Fragaria vesca, 10 June 2012, Alain Gardiennet AG12071 (BPI 919213); Bourberain, 37 route de Chazeuil, on Fragaria × ananassa, 10 June 2012, Alain Gardiennet AG12072 (BPI 919212), Côte-d’Or, Bretenière, la Garande, on Fragaria sp. (cultivated), 23 June 2018, Alain Gardiennet AG18036, UK: on Fragaria sp. dates and collector unknown (IMI 10064, living culture CBS 146.64 = ATCC 16651).

Notes: The holotype specimen of Gnomonia fragariae was not available in Klebahn’s collection in BREM (pers. comm. Michael Stiller). The specimen (IMI 100647) linked to CBS 146.64 housed in K consists of a dry culture and slides, which may not contain conspicuous fungal structures to observe (pers. comm. Angela Bond & Paul Cannon); however, molecular data are available. Senanayake et al. (2017b) described the taxon without typifications and clarifications of affiliated names or specimens. Therefore, Moročko-Bičevska et al. (2019) designated original drawings by Klebahn (1918) specified in his original publication as a lectotype of G. fragariae and a freshly collected specimen from Latvia as an epitype, based on its morphology on the host and in culture.

DISCUSSION

Post- and pre-harvest fungal diseases of strawberry cause significant annual losses to strawberry production (Maas 1998; Garrido et al. 2011). Phytopathogenic fungi are able to infect each and every part of the strawberry plant including leaves, petioles, fruits, sepals, stolon, crown and root systems at any age of the growth (Garrido et al. 2016). Although the fungal genera Botrytis, Colletotrichum, Fusarium and Verticillium causes major diseases of strawberry, several other pathogens also have significant impact on annual production (Leroch et al. 2013; Baroncelli et al. 2015). Species in the order Diaporthales also have been generally associated with strawberry diseases, although much confusion exists regarding the taxonomy, nomenclature, and evolutionary relationships of the taxa (Maas 1998; Garrido et al. 2016). In this study, evolutionary relationships of the leaf blight and leaf blotch pathogens widely known from North American strawberry fields and other strawberry growing regions in the world were revisited. Fresh collections of diseased specimens, pure cultures and multilocus phylogenetic analysis were used to resolve taxonomic problems. Type and other historic specimens from herbaria were observed and compared with fresh fungal collections to provide comprehensive nomenclatural clarification.

Leaf blight of strawberry was initially identified by characteristic large V-shaped necrotic lesions along major veins bearing black protruding necks of the pycnidia when examined under the stereo microscope (Fig. 2). Although the fungus infects leaves early in the growing season, leaf blight symptoms are more common on older leaves near or during harvest. The pathogen can weaken the plants through the destruction of older foliage and can also infect runner stems, calyxes, and fruits in some varieties (Maas 1998). The leaf blotch fungus, Gnomoniopsis fragariae is characterized by purplish to brown blotches and in later stages by large necrotic spots with abundant conidiomata around the major veins of the leaf (Fig. 3). The spots often occur on the end of a leaflet and are rounded to wedge shaped. This fungus can be found on the petiole, calyx, fruit stalk, and fruit. New collections of petiole blight and root rot pathogens were found in France occurring on stalks of perennial Fragaria sp. The symptoms often are confused with the early stages of leaf scorch caused by Diplocarpon fragariae (Helotiales) and leaf blotch caused by G. fragariae. Weakened plants may overwinter, which can result in reduced yields in the following season in commercial cultivations. Under conditions highly favorable for disease development, leaf blight can cause severe defoliation leading to plant death. Leaf blight fungus is often listed as a leading threat to strawberry and commonly co-occurs with other pathogens causing leaf blotch, leaf scorch and numerous leaf spots (Maas 1998). Close inspection of symptoms of various fresh specimens and historical collections housed in the U. S. National Fungus Collections revealed that it is possible to distinguish these taxa based on symptomology as well as microscopic examination of the fungal structures when present.

One additional species associated with strawberry included in the analysis is Ophiogonomia rosae (Gnomoniaceae) as identified by Walker et al. (2012) and represented by isolate CBS 128442 isolated from Fragaria vesca (Fig. 1). The same study reported the occurrence of O. rosae on overwintered leaves of F. vesca, Comarum palustre, Rosa sp., and Rubus sp. (Rosaceae) from various geographic regions of the world. Pathogenicity on these hosts is unknown, but it is likely O. rosae either possesses a saprobic lifestyle or is perhaps a weakly opportunistic pathogen. No specific reports of it as a pathogen of strawberry are known to exist and symptomology remains unknown.

The family composition of the order Diaporthales has changed with various classification systems originally based on morphology and later based on phylogenetic analyses (Wehmeyer 1975; Barr 1978; Castlebury et al. 2002), with Diaporthaceae, Gnomoniaceae, Valsaceae, Melanconidaceae and Pseudovalsaceae as the earliest defined families based on morphological characters (Wehmeyer 1975; Barr 1978; Vasilyeva 1987; Castlebury et al. 2002; Gryzenhout et al. 2006; Cheewangkoon et al. 2010; Crous et al. 2015). We confirmed that the Melanconiellaceae, which is broadly defined in this study, is a well-resolved family distinct from other closely related families. However, it is widely known that Melanconium-like taxa are polyphyletic and scattered throughout the order, and therefore need to be redefined with reference to the placement of the type species. The genus Melanconiella was considered as Diaporthales incertae sedis until recently and placed in Sphaeriales in early classifications (Clements and Shear 1931). It is now classified within Melanconiellaceae with numerous other species (Voglmayr et al. 2012; Du et al. 2017). Melanconiella species were known to be associated with the host family Betulaceae, including Betula, Carpinus, Corylus and Ostrya, and considered to be highly host specific. Du et al. (2017) described M. cornuta associated with canker and dieback of Cornus controversa (Cornaceae) and Juglans regia (Juglandaceae) from China. Greeneria uvicola causes bitter rot and necrotic fleck of grapes (Vitis spp., Vitaceae) in North America, Australia and elsewhere in the world and often misidentified and is often confused with other common diaporthalean pathogens on grapevines including Diaporthe ampelina (Diaporthaceae) (Farr et al. 2001; Steel et al. 2007; Longland and Sutton 2008). Microascospora rubi is associated with Rubus ulmifolia from Italy but appears to be a saprobe (Senanayake et al. 2017a). However, the generic delimitation and species diversity within the family Melanconiellaceae are yet to be resolved with more collections and molecular data of closely related taxa.

Early morphology-based classification systems placed species that occur singly within the substrate without any stromatic development in the family Gnomoniaceae (Wehmeyer 1975; Barr 1978; Monod 1983). However, molecular data and large-scale sampling of taxa have revealed that gnomoniaceous taxa sensu Wehmeyer (1975) and Monod (1983) are polyphyletic. Improvements in phylogenetic understanding have ultimately resulted in a more natural classification, leading to better insights into the evolutionary history of the Diaporthales and other Sordariomycetes (Zhang et al. 2006; Hongsanan et al. 2017; Guterres et al. 2019). These methods have also led to improvements of the understanding of the seemingly minor morphological differences of the sexual morphs of these ascomycete genera for identification purposes. Therefore, finding and utilizing phylogenetically informative genes are critical to obtain compelling, yet previously unrecognized, data to develop new evolutionarily significant insights and to encourage innovative practices in modern fungal systematics.

Due to the morphological plasticity of both asexual and sexual morphs, confusion has remained in generic and family-level classifications of many diaporthalean fungi. Phylogenetic analyses based on single gene trees have been often problematic. The conventionally used nuc 28S rDNA roughly distinguished taxa at generic and family levels, but several genera and families were poorly supported or otherwise not distinguished. Single morphological characters previously used to segregate genera or families in ascomycetes have often been found to be discordant with multilocus phylogenies and phylogenomic analyses (Choi and Kim 2017; Yang et al. 2018; Voglmayr et al. 2019b).

The best approach for developing knowledge about species in this diverse group of plant-associated fungi is through a consolidated platform utilizing morphological data, multigene phylogeny, as well as host associations and historical background information connected to voucher specimens in herbaria. For instance, correct identification of Paraphomopsis obscurans required the time-consuming process of sifting through the complicated historical literature of various genera within Diaporthales as well as unrelated genera and observation of numerous specimens. From this historical research, it was evident that previous authors observed morphological and physiological distinctions from other genera including Dendrophoma, Diaporthe, Phoma, Phyllostica, Sphaeronaemella, and Zythia. As the taxonomic opinions were based on the observation of the vouchered specimens, it was possible to reassess these opinions based on the same or other authentic specimens. To this end, a consolidated approach of multilocus phylogenetic analyses and morphological observations will provide the best resolution for taxonomists, evolutionary biologists, plant pathologists, and quarantine officials in their efforts to address issues regarding accurate identification, host plant associations and interactions, and disease management.

CONCLUSIONS

Molecular phylogeny based on newly generated DNA sequences of diaporthalean fungi associated with strawberry diseases revealed that the leaf blight pathogen represents a new evolutionary lineage within the family Melanconiellaceae, distinct from closely related taxa. The combined phylogeny based on four loci (ITS, LSU, RPB2, and TEF1) together with morphological data illustrate the generic and family-level relationships in this diverse order of fungi. Although, leaf blight, leaf blotch, petiole blight and root rot fungi of strawberry are frequently encountered, the taxonomy, accurate naming and geographic distribution were largely overlooked until recently. Therefore, this study highlights the need for revisiting poorly known genera of phytopathogenic diaporthalean fungi in order to establish their evolutionary relationships and provide reference DNA sequences for accurate identification purposes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was funded by USDA-ARS Projects 8042-21220-257-00-D and 8042-22000-298-00-D. Dhanushka Udayanga thanks University of Sri Jayewardenepura for facilitating ongoing research. The authors wish to thank Shannon Dominick (BPI) for facilitating loans from various herbaria and assistance at BPI, Tunesha Phipps and Ryan Vo for technical assistance, W. Cavan Allen for nomenclatural assistance, John Enns, Phil Edmonds, and the USDA-ARS Beltsville Research Support Services for field and greenhouse support, herbarium curators and managers of CUP, S, K, FR, BONN, BREM and UPS for the loan of specimens and/or providing information about specimens in their collections. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or any of the other coauthors’ institutions.

Adherence to national and international regulations

Not applicable.

ABBREVIATIONS

- avg.

Average

- BI

Bayesian Inference

- BPI

United States National Fungus Collections

- BPP

Bayesian Posterior Prabalities

- ITS

Ribosomal internal transcribed spacers 1 and 2 with 5.8S ribosomal DNA

- LSU

28S ribosomal DNA/large subunit rDNA

- MEA

Malt Extract Agar

- ML

Maximum Likelihood

- nuc 18S rDNA

Nuclear 18S/ small subunit of ribosomal DNA

- PDA

Potato Dextrose Agar

- rDNA

Ribosomal DNA

- 5.8S

Ribosomal DNA 5.8S region

- RPB2

Partial sequences of second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II

- SD

Standard Deviation

- TEF1

Translation elongation factor 1-α

- V8A

V8 juice Agar

- WA

Water Agar

- wk

Week

Authors’ contributions

DU and LAC designed the research. DU performed the experiments. DU, DSM, SDM performed data analysis. LAC, KL and AG contributed with specimens and/or funds for research. All authors contributed to data interpretation and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by USDA-ARS Projects 8042–21220–257-00-D and 8042–22000–298-00-D and was supported in part by the appointment of Dhanushka Udayanga to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Research Participation Program administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and USDA (contract number DE579AC05-06OR23100).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Ag Data Commons, U.S. Department of Agriculture 10.15482/USDA.ADC/1518737

DECLARATIONS

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

REFERENCES

- Abdelfattah A, Wisniewski M, Nicosia MGLD, Cacciola SO, Schena L. Metagenomic Analysis of Fungal Diversity on Strawberry Plants and the Effect of Management Practices on the Fungal Community Structure of Aerial Organs. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abd-El-Kareem F, Elshahawy IE, Abd-Elgawad MM. Management of strawberry leaf blight disease caused by Phomopsis obscurans using silicate salts under field conditions. Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 2019;43(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s42269-018-0041-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos CJ, Cation D. Gnomonia fragariae in Michigan. Mycologia. 1952;44(2):221–223. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1952.12024190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri SA, Jr, Langdon KR, Wehlburg C, Kimbrough JW. Index of Plant Diseases in Florida (Revised) Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industry Bulletin. 1984;11:1–389. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HW. Dendrophoma leaf blight of strawberry. Agriculture Experiment Bulletin of University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. 1920;229:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous (1979) List of plant diseases in Taiwan. Plant Protection Society, Republic of China

- Baroncelli R, Zapparata A, Sarrocco S, Sukno SA, Lane CR, Thon MR, Vannacci G, Holub E, Sreenivasaprasad S (2015) Molecular diversity of anthracnose pathogen populations associated with UK strawberry production suggests multiple introductions of three different Colletotrichum species. PLoS One 10(6):e0129140. 10.1371/journal.pone.0129140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Barr ME. Diaporthales in North America with emphasis on Gnomonia and its segregates, Mycologia Memoirs Series, No. 7. Lehre: Published for the New York Botanical Garden by J. Cramer in collaboration with the Mycological Society of America; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Black BL, Enns JM, Hokanson SC. A comparison of temperate-climate strawberry production systems using eastern genotypes. Hort Technology. 2002;12(4):670–675. doi: 10.21273/HORTTECH.12.4.670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bobev S (2009) Reference guide for the diseases of cultivated plants (Translated from Russian). Makros Publishers

- Bolay A (1971) Contribution à la connaissance de Gnomonia comari Karsten (syn. G. fructicola [Arnaud] Fall): étude taxonomique, phytopathologique et recherches sur sa croissance in vitro. Berichte der Schweizerischen Botanischen Gesellschaft 81:398–482. 10.5169/seals-57134

- Bolton AT. Gnomonia fructicola on strawberry. Canadian Journal of Botany. 1954;32(1):172–181. doi: 10.1139/b54-015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Kohn LM. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia. 1999;91(3):553–556. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1999.12061051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cash EK (1953) A record of the fungi named by J.B. Ellis Part II. U.S. Department of Agriculture Special Publication, Beltsville, Maryland. pp. 166–345. 10.5962/bhl.title.149755

- Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Jaklitsch WJ, Vasilyeva LN. A preliminary overview of the Diaporthales based on large subunit nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycologia. 2002;94(6):1017–1031. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2003.11833157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheewangkoon R, Groenewald JZ, Verkley GJM, Hyde KD, Wingfield MJ, Gryzenhout M, Summerell BA, Denman S, Toanun C, Crous PW. Re-evaluation of Cryptosporiopsis eucalypti and Cryptosporiopsis-like species occurring on Eucalyptus leaves. Fungal Diversity. 2010;44(1):89–105. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0041-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Kim SH. A genome tree of life for the fungi kingdom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017;114(35):9391–9396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711939114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements FE, Shear CL. The genera of fungi. New York: H. W. Wilson and Co.; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Cook RP, Dubé AJ (1989) Host-pathogen index of plant diseases in South Australia. Field Crops Pathology Group South Australian Department of Agriculture

- Crous PW, Phillips AJL, Baxter AP. Phytopathogenic Fungi from South Africa. Stellenbosch, Western Cape South Africa: University of Stellenbosch, Department of Plant Pathology Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Verkley GJM, Christensen M, Castaneda-Ruiz RF, Groenewald J. How important are conidial appendages ? Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2012;28(1):126–137. doi: 10.3767/003158512X652624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Summerell BA, Shivas RG, Carnegie AJ, Groenewald JZ. A re-appraisal of Harknessia (Diaporthales), and the introduction of Harknessiaceae. Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2012;28(1):49–65. doi: 10.3767/003158512X639791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Carris LM, Giraldo A, Groenewald JZ, Hawksworth DL, Hernández-Restrepo M, Jaklitsch WM, Lebrun MH, Schumacher RK, Stielow JB, van der Linde EJ, Vilcāne J, Voglmayr H, Wood AR. The Genera of Fungi – fixing the application of the type species of generic names - G 2: Allantophomopsis, Latorua, Macrodiplodiopsis, Macrohilum, Milospium, Protostegia, Pyricularia, Robillarda, Rotula, Septoriella, Torula, and Wojnowicia. IMA Fungus. 2015;6:163–198. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2015.06.01.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnington J (2003) Pathogenic fungi on introduced plants in Victoria. A host list and literature guide for their identification. Department of Primary Industries, State of Victoria Knoxfield, Victoria Australia

- Dhingra OD, Sinclair JB. Culture media and their formulas. In: Basic Plant Pathology Methods. Florida: CRC Press Inc. Boca Raton; 1985. pp. 345–394. [Google Scholar]

- Dingley JM, Fullerton RA, McKenzie EHC. Survey of Agricultural Pests and Diseases. Technical Report Volume 2. Records of Fungi, Bacteria, Algae, and Angiosperms Pathogenic on Plants in Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Niue, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Western Samoa. Rome: FAO; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Fan XL, Yang Q, Tian CM. Host and geographic range extensions of Melanconiella, with a new species M. cornuta in China. Phytotaxa. 2017;327(3):252–260. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.327.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JB, Everhart BM. New species of fungi from various localities. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 1894;46:322–384. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MA, Nita M, Madden LV. First report of Phomopsis fruit rot of strawberry in Ohio. Plant Disease. 2000;84(2):199–199. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.2.199C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshenaur BC, Milholland RD. Factors influencing the growth of Phomopsis obscurans and disease development on strawberry leaf and runner tissue. Plant Disease. 1989;73(10):814–819. doi: 10.1094/PD-73-0814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fall J. Studies on fungus parasites of strawberry leaves in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Botany. 1951;29(4):299–315. doi: 10.1139/b51-029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Yang Q, Bezerra JD, Alvarez LV, Tian C. Diaporthe from walnut tree (Juglans regia) in China, with insight of the Diaporthe eres complex. Mycological Progress. 2018;17(7):841–853. doi: 10.1007/s11557-018-1395-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farr DF, Rossman AY. Fungal Databases, U.S. National Fungus Collections, ARS, USDA. Available from: https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/. Accessed 25 Apr 2020

- Farr DF, Castlebury LA, Rossman AY, Erincik O. Greeneria uvicola, cause of bitter rot of grapes, belongs in the Diaporthales. Sydowia. 2001;53(2):185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1981;17(6):368–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido C, Carbú M, Fernández-Acero FJ, González-Rodríguez VE, Cantoral JM. New insights in the study of strawberry fungal pathogens. Genes Genomes Genomics. 2011;5:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido C, González-Rodríguez VE, Carbú M, Husaini AM, Cantoral JM. Fungal Diseases of Strawberry and their Diagnosis. In: Husaini AJ, Neri D, editors. Strawberry: Growth. Wallingford, UK: Development and Diseases, CABI; 2016. pp. 157–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes RR, Glienke C, Videira SIR, Lombard L, Groenewald JZ, Crous PW. Diaporthe: a genus of endophytic, saprobic and plant pathogenic fungi. Persoonia. 2013;31(1):1–41. doi: 10.3767/003158513x666844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez AO, Mattner SW, Oag D, Nimmo P, Milinkovic M, Villalta ON. Protecting fungicide chemistry used in Australian strawberry production for more sustainable control of powdery mildew and leaf blotch. Acta Horticulturae. 2017;1156(1156):735–742. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2017.1156.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gryzenhout M, Myburg H, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. Cryphonectriaceae (Diaporthales), a new family including Cryphonectria, Chrysoporthe, Endothia and allied genera. Mycologia. 2006;98(2):239–249. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueidan C, Roux C, Lutzoni F. Using a multigene phylogenetic analysis to assess generic delineation and character evolution in Verrucariaceae (Verrucariales, Ascomycota) Mycological Research. 2007;111(10):1145–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterres DC, Galvão-Elias S, dos Santos MDDM, de Souza BCP, de Almeida CP, Pinho DB, Miller RNG, Dianese JC. Phylogenetic relationships of Phaeochorella parinarii and recognition of a new family, Phaeochorellaceae (Diaporthales) Mycologia. 2019;111(4):660–675. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2019.1603025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggag WM. First report of Phomopsis leaf blight of strawberry in Egypt. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2009;91:239. doi: 10.4454/jpp.v91i1.649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock JF. Strawberries. Wallingford, UK: CABI; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hausner G, Reid J. The nuclear small subunit ribosomal genes of Sphaeronaemella helvellae, Sphaeronaemella fimicola, Gabarnaudia betae, and Cornuvesica falcata: phylogenetic implications. Canadian Journal of Botany. 2004;82(6):752–762. doi: 10.1139/b04-046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hongsanan S, Maharachchikumbura SS, Hyde KD, Samarakoon MC, Jeewon R, Zhao Q, et al. An updated phylogeny of Sordariomycetes based on phylogenetic and molecular clock evidence. Fungal Diversity. 2017;84(1):25–41. doi: 10.1007/s13225-017-0384-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(8):754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F, Nielsen R, Bollback JP. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science. 2001;294(5550):2310–2314. doi: 10.1126/science.1065889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Fan XL, Crous PW, Tian CM. Species of Dendrostoma (Erythrogloeaceae, Diaporthales) associated with chestnut and oak canker diseases in China. MycoKeys. 2019;48:67–96. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.48.31715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]