Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this study was to determine phenotypes characterizing cardiac involvement in AL amyloidosis by using direct (fluorine-18-labeled florbetapir {[18F]florbetapir} positron emission tomography [PET]/computed tomography) and indirect (echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance [CMR]) imaging biomarkers of AL amyloidosis.

BACKGROUND

Cardiac involvement in systemic light chain amyloidosis (AL) is the main determinant of prognosis and, therefore, guides management. The hypothesis of this study was that myocardial AL deposits and expansion of extracellular volume (ECV) could be identified before increases in N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide or wall thickness.

METHODS

A total of 45 subjects were prospectively enrolled in 3 groups: 25 with active AL amyloidosis with cardiac involvement (active-CA), 10 with active AL amyloidosis without cardiac involvement by conventional criteria (active-non-CA), and 10 with AL amyloidosis with cardiac involvement in remission for at least 1 year (remission-CA). All subjects underwent echocardiography, CMR, and [18F]florbetapir PET/CT to evaluate cardiac amyloid burden.

RESULTS

The active-CA group demonstrated the largest myocardial AL amyloid burden, quantified by [18F]florbetapir retention index (RI) 0.110 (interquartile range [IQR]: 0.078 to 0.139) min−1, and the lowest cardiac function by global longitudinal strain (GLS), median GLS −1 1% (IQR: −8% to −13%). The remission-CA group had expanded extracellular volume (ECV) and [18F]florbetapir RI of 0.097 (IQR: 0.070 to 0.124 min−1), and abnormal GLS despite hematologic remission for >1 year. The active-non-CA cohort had evidence of cardiac amyloid deposition by advanced imaging metrics in 50% of the subjects; cardiac involvement was identified by late gadolinium enhancement in 20%, elevated ECV in 20%, and elevated [18F]florbetapir RI in 50%.

CONCLUSIONS

Evidence of cardiac amyloid infiltration was found based on direct and indirect imaging biomarkers in subjects without CA by conventional criteria. The findings from [18F]florbetapir PET imaging provided insight into the preclinical disease process and on the basis of interpretation of expanded ECV on CMR and have important implications for future research and clinical management of AL amyloidosis. (Molecular Imaging of Primary Amyloid Cardiomyopathy [MICA]; NCT02641145)

Keywords: [18F]florbetapir, cardiac amyloidosis, cardiac magnetic resonance, echocardiography, light chain amyloidosis, longitudinal strain imaging, positron emission tomography

Light chain amyloidosis (AL) is a disease in which circulating light chains, derived from immunoglobulin, misfold and are deposited in various organs as insoluble amyloid fibrils (1). Although AL amyloidosis may affect almost any organ, the most serious consequences are due to cardiac involvement. Echocardiographic features of cardiac amyloidosis were first defined more than 40 years ago and formed the basis of early consensus definitions of the presence of cardiac involvement in AL amyloidosis (2). With the widespread development and use of measurements of cardiac troponin and natriuretic peptide, it became apparent that the addition of these biomarkers offered prognostic significance and that abnormal biomarkers may be present in AL amyloid patients in whom echocardiography failed to meet the (then) criteria for cardiac involvement (3). Since the first report of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in amyloidosis (4), increasing sophistication of this technique has demonstrated its ability to image expanded extracellular volume in AL amyloidosis (5). This again raised the bar for the definition of early disease.

However, expanded extracellular volume (ECV) by CMR, although strongly suggestive of cardiac involvement in a patient with known AL amyloidosis, may be seen in many cardiac diseases, including common ones such as hypertensive disease and is not specific for early amyloidosis.

Data from the present (6) and other investigators (7) suggest a promising role for cardiac amyloid imaging using fluorine-18-labeled florbetapir ([18F] florbetapir) and positron emission tomography (PET). An autoradiography study demonstrated direct binding of [18F]florbetapir to AL (and transthyretin) deposits (8) and cardiac imaging with [18F]florbetapir has been shown to be a feasible and highly specific molecular imaging marker of amyloid deposition in humans (6,9). Hypothetically, light chain amyloid deposits resulting in ECV expansion may be present in the myocardium of individuals prior to an increase in N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels. However, this could not be studied until now due to the lack of a direct imaging biomarker of myocardial amyloid. To date, specific comparisons among echocardiography, CMR, and [18F]florbetapir PET imaging, evaluating whether cardiac involvement could be diagnosed in patients with systemic AL amyloidosis defined by current echocardiographic/biomarker criteria as not having cardiac involvement, has not been described. No studies have prospectively compared structural and functional amyloid imaging biomarkers in subjects across the spectrum of systemic AL amyloidosis in patients with active AL cardiac amyloidosis, remission AL cardiac amyloidosis, active AL systemic amyloidosis without cardiac involvement. The 2 aims of this study were, first, to systematically compare direct and indirect imaging biomarkers of cardiac AL burden in subjects across the spectrum of systemic AL amyloidosis, and, second, to identify the earliest detectable manifestations of cardiac amyloid deposition, including AL deposits detected by [18F]florbetapir, ECV expansion, NT-proBNP release, or abnormal global longitudinal strain (GLS).

METHODS

SUBJECT SELECTION.

This study included 45 subjects with biopsy-proven systemic AL amyloidosis who were consecutively and prospectively enrolled in the ongoing MICA (Molecular Imaging of Primary Amyloid Cardiomyopathy; NCT02641145) study. The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee. Each subject provided written informed consent for participation. Subjects were recruited from 5 centers (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston Medical Center, Boston University School of Medicine, and Boston and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York).

STUDY CRITERIA, GROUPS, AND PROCEDURES.

The study cohort included subjects with systemic AL amyloidosis diagnosed by biopsy and typing of amyloid by immunohistochemistry or by mass spectroscopy. A total of 35.5% of subjects had a positive endomyocardial biopsy result, 28.9% had fat pad and 24.4% renal involvement; other biopsy sites included lung, gastrointestinal tract, and temporal artery (8.9%). Cardiac amyloidosis was defined by current consensus criteria using biopsy analysis proof of systemic AL amyloidosis and elevated cardiac serum markers (abnormal cardiac troponin T or age-adjusted NT-proBNP) (2). All subjects were free of nonamyloid cardiac disease and were divided into 3 groups as follows. Group 1 consisted of subject with active AL amyloidosis with cardiac involvement (active-CA); subjects with systemic AL amyloidosis and cardiac involvement with, at the time of imaging, an active plasma cell dyscrasia (defined as elevated serum free light chain with an abnormal kappa:lambda ratio and/or increased percentage of clonal plasma cells on bone marrow biopsy). Group 2 included subjects with systemic AL amyloidosis with an active plasma cell dyscrasia but without cardiac involvement by standard consensus criteria, namely, those with a normal mean left ventricular (LV) wall thickness by echocardiogram, and normal cardiac serum markers (referred to as “active-non-CA”). Group 3 had subjects who had previously undergone chemotherapy and who had achieved an improved partial response or complete hematologic light chain response, defined as differential free light chain (dFLC) levels <40 mg/l or a normal serum free light chain ratio for more than 12 months, respectively. These subjects all had evidence of cardiac involvement at the time of diagnosis and were termed the remission cardiac-AL (“remission-CA”) group. All subjects underwent detailed evaluation of serum biomarkers, echocardiography, myocardial [18F]florbetapir PET, and gadolinium contrast-enhanced CMR.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY.

Two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography with spectral and color Doppler imaging and advanced speckle tracking imaging was performed in all subjects according to standard American Society of Echocardiography recommendations (10). Conventional analysis of the LV included measurements of wall thickness, LV mass, LV ejection fraction (LVEF), and diastolic function. The peak velocities of the mitral E and A waves, the pulmonary vein S and D waves by pulse-wave Doppler, and the E′ waves of the lateral and septal mitral annulus by tissue Doppler imaging, and the deceleration time of the E wave, were used to assess diastolic dysfunction. An E/e′ ratio of >15 was considered representative of high left atrial pressures.

Deformation analysis of the left ventricle based on 2D speckle tracking imaging was performed off-line using dedicated software Image Arena version 4.6 (TomTec, Leipzig, Germany).

CONTRAST-ENHANCED CMR.

All CMR images were acquired using a 3.0-T system (Tim Trio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), with electrocardiographic gating and breath holding as described previously (11). The protocol consisted of steady-state free-precession cine imaging for assessing ventricular function and morphology and native and post-contrast T1 mapping for quantification of myocardial ECV using a modified Look-Locker 5–3-3 technique. Segmental ECVs were calculated by using the ratio of changes of relaxation rates of the myocardium to those of blood and adjusted to the fractional blood volume of distribution (1 – hematocrit) ● (1/post-contrast myocardial T1 — 1/pre-contrast myocardial T1)/(1/post-contrast blood T1 — 1/pre-contrast blood T1). Global myocardial ECV was then calculated by averaging the myocardial segmental ECV values from the short-axis slices at the base, mid, and apical LV levels (Figure 1). Commercial software (MedisSuite version 3.0 Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands) was used for post-processing and quantifying LV volumes, ejection fractions, mass, wall thicknesses, dimensions, and T1 mapping values (12). Measurements were obtained globally (when applicable) and segmentally at the basal, mid, and apical levels. LV wall thickness was measured following a modified American Heart Association left ventricular 17-segment model (13).

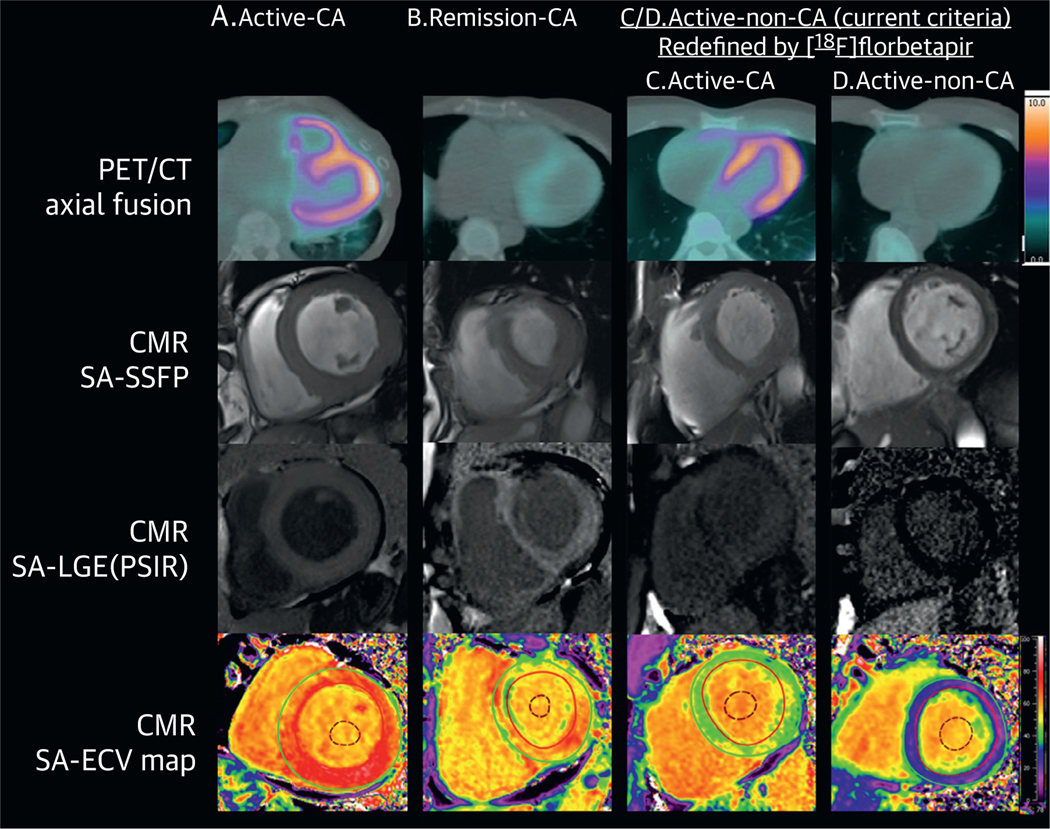

FIGURE 1. Cardiac Phenotype by LV Myocardial [18F]florbetapir Uptake and CMR in AL Amyloidosis.

Images from each of the 3 study groups (active AL-CA [A], remission AL-CA [B], active AL-no CA [C and D]) are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The active AL-no CA group was further divided into preclinical cardiac involvement or not based on [18F]florbetapir RI >0.06 min−1 (C) or <0.06 min−1 (D). This figure shows [18F]florbetapir PET/CT fusion axial images (top), CMR end-diastolic cine still (second row), CMR LGE (third row), and ECV maps (bottom). Subjects in the active AL-CA (A), remission AL-CA (B), active AL-no CA with [18F]florbetapir RI >0.06 min-1 (C), groups have LV myocardial [18F]florbetapir uptake and CMR evidence of cardiac amyloid deposition, with transmural LGE and abnormally elevated ECV values. The subject in the last column (D) had no LGE and a normal ECV, with minimal (if any) LV myocardial [18F]florbetapir uptake. [18F]florbetapir = fluorine-18-labeled florbetapir; AL-CA = light chain cardiac amyloidosis; CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance; ECV = extracellular volume; GLS = global longitudinal strain; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; PET/CT = positron emission tomography/computed tomography; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; RI = retention index; SA-LGE-PSIR = short axis-late gadolinium enhancement-phase sensitive inversion recovery; SA-SSFP = short axis-steady state free precession.

[18F]florbetapir PET/CT.

The scan protocol included a cardiac 3D mode PET/CT (Discovery ST unit, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin) 60-min list-mode acquisition with the patient’s arms by the side. Individuals were positioned with the help of a computed tomography (CT) tomogram, and a low- dose CT scan of the heart was acquired for attenuation correction of PET emission data. [18F] florbetapir (355 ± 48 MBq [9.6 ± 1.3 mCi]) was injected through an intravenous catheter 1 min after the start of the PET cardiac acquisition.

DIRECT MEASUREMENTS OF CARDIAC AMYLOID DEPOSITS.

Myocardial retention index (RI) for [18F] florbetapir was used as a direct measurement of amyloid deposition in the myocardium. Myocardial retention (min−1) of [18F]florbetapir, defined as the active concentration in myocardial tissue between 10 and 30 min, normalized by the integral from 0 to 20 min of the image-derived (left atrium) arterial input function, determined using Carimas version 2.9 software (Turku PET Center, Finland). Myocardial RI was defined globally for the entire LV. A median global RI of >0.03 min−1 was defined as abnormal, based on prior data comparing healthy controls with subjects with cardiac AL amyloidosis (6). A more stringent cutoff value, >0.06 min−1, was used for active amyloidosis involvement based on the minimum RI of the active-CA group.

INDIRECT MEASURES OF CARDIAC AMYLOID DEPOSITS.

Cardiac structural parameters.

LV wall thickness was assessed by echocardiography and CMR. An LV wall thickness >12 mm by echocardiogram was considered abnormal, consistent with the consensus criteria (2). LV mass was assessed by CMR and was considered abnormal when the measurement was outside the normal range for males and females, that is, >80 g/m2 and >62 g/m2, respectively, and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) results were visually graded as present or absent. The cutoff value for an abnormal ECV was >0.34 and an “amyloidosis-specific” cutoff value of >0.41 was also used (14,15).

Cardiac functional parameters.

The effects of amyloid deposits on cardiac function were determined using several echocardiographic parameters, including GLS, relative apical sparing of LS (RELAPS), and global LVEF. Abnormal GLS was defined as less negative than −19% (10), and less negative than −16% (16) was used as a more stringent cutoff value for a clearly abnormal strain. Relative apical sparing of GLS was defined using previously described criteria; the optimal cutoff value of 1 for the relative apical GLS was shown to differentiate CA from other causes of increased LV wall thickness with a high sensitivity and specificity (16).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

Continuous variables are shown as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for all data, normally and non-normally distributed. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables among the 3 groups, followed by the Mann-Whitney U test for 2 pre-specified pairwise comparisons. A Fisher exact test with 2 degrees of freedom (df) was used to compare differences among the 3 groups for binary variables and then a 1-df Fisher exact test to analyze the 2 pairwise comparisons. Post-hoc comparisons for the 3 groups, active-CA, remission-CA, and active-non-CA, are presented with active-CA as the reference group. All statistical data were analyzed using STATA version 14.1 software (College Station, Texas) and all statistical tests were 2-tailed, with a p value <0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

BASELINE CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the 3 study groups are summarized in Table 1. The subjects without cardiac involvement by conventional criteria (active-non-CA) were significantly younger than the subjects with cardiac involvement (active-CA and remission-CA). The dFLCs were, by definition, lowest in the remission-CA group. The median interval was <1 day between PET and CMR scans, 1 day for CMR and echocardiogram, and 2 days for echocardiogram and PET scans.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Groups

| Active Cardiac AL (n = 25) | Remission Cardiac AL (n = 10) | Active Non-Cardiac AL (n = 10) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, yrs | 64 (59–67) | 62 (59–69) | 57.5 (51–62) | 0.03* |

| Females | 11 (44) | 6 (60) | 2 (20) | 0.19 |

| NYHA functional class ≥II | 23 (92) | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | 0.001* |

| 6-MWT distance, m | 370 (330–443.5) | 423 (381–480) | 443 (390–538) | 0.13 |

| Revised Mayo cardiac stage ≥II | 18 (72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001*† |

| Laboratory markers | ||||

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.21 (0.920–1.37) | 0.93 (0.88–1.1) | 1.02 (0.74–1.14) | 0.15 |

| dFLC, mg/l | 283.7 (75–502.4) | 7.7 (3.7–11.4) | 137.5 (82.8–340.8) | <0.001† |

| Kappa:lambda ratio | 0.15 (0.03–0.49) | 1.1 (0.45–1.34) | 0.075 (0.03–0.19) | 0.001† |

| Serum cardiac biomarkers | ||||

| Troponin T, ng/ml | 0.09 (0.01–0.12) | 0.01 (<0.01–0.01) | <0.01 | <0.001*† |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 6,200 (2,331–10,18) | 1,034 (588–1,484) | 149.5 (66–248) | <0.001*† |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%). Revised Mayo staging system assigns a score of 1 for each of dFLC >180 mg/l, troponin T >0.025 ng/ml, and NT-proBNP >1,800 pg/ml, creating stages I to IV with scores of 0 to 3 points, respectively.

p < 0.05 for Active Cardiac AL vs. Active Non-cardiac AL;

p < 0.05 for Active Cardiac AL vs. Remission Cardiac AL chain. 6-MWT = 6-min walking test; AL = light amyloidosis; dFLC = difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains; NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide;

NYHA = New York Heart Association

CARDIAC AMYLOID BURDEN BY CLINICAL GROUP.

Active cardiac AL group.

Most of the active-CA cohort had symptoms of heart failure, with 92% having New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II or greater symptoms. The active-CA group had the largest cardiac amyloid burden by direct and indirect measurements and the lowest cardiac function (Table 2). In addition, NT-proBNP and troponin T levels were highest in this group (Table 1). All subjects in this group had evidence of amyloid by LGE and abnormal LV mass (indexed LV mass was 96.9) of (IQR: 81.4 to 108.9) g/m2 and 78.9 (IQR: 51.1 to 83.4) g/m2, in men and women respectively). Consistent with these structural changes, the ECV was markedly elevated in this group (Figure 1). Amyloid measured directly by [18F]florbetapir PET RI was abnormal in all subjects in this group; the median [18F]florbetapir RI was 0.11 min−1 (IQR: 0.078 to −0.139 min−1), and the minimum value in this group was 0.062 min−1.

TABLE 2.

Imaging Biomarkers of Cardiac Involvement in Systemic AL Amyloidosis

| Active Cardiac AL (n = 25) | Remission Cardiac AL (n = 10) | Active Non-Cardiac AL (n = 10) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiographic measurements | ||||

| Chamber measurements | ||||

| IVS, mm | 16.0 (14.6 to 21.2) | 16.0 (14.3 to 16.7) | 11.6 (10.8 to 12.2) | <0.001* |

| PW, mm | 16.7 (14.8 to 18.4) | 15.0 (12.7 to 16.8) | 11.0 (9.5 to 11.8) | <0.001* |

| LA volume, cm3 | 57.7 (51.2 to 79.1) | 72.2 (43.7 to 88.6) | 58.3 (48.8 to 72.0) | 0.81 |

| LA volume indexed, cm3/m2 | 31.0 (26.3 to 43.0) | 42.2 (25.4 to 49.8) | 27.9 (24.6 to 32.0) | 0.33 |

| Doppler measurements | ||||

| E/A ratio, unitless | 2.06 (1.54 to 2.28) | 1.66 (1.08 to 2.14) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.09) | 0.003* |

| DT, cm/s | 172 (143 to 189) | 190 (167 to 229) | 195 (187 to 229) | 0.07 |

| E/e′ ratio, unitless | 23 (17 to 29) | 17 (13 to 23) | 8 (7 to 10) | <0.001* |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity, m/s | 2.50 (2.23 to 2.84) | 2.27 (2.01 to 2.45) | 2.27 (2.04 to 2.70) | 0.29 |

| Peak longitudinal strain measurements | ||||

| GLS, % | −10.7 (—7.9 to −13.4) | −13.3 (−13.1 to −1 7.2) | —23.2 (−1 6.7 to —25.0) | <0.001*† |

| GLS <−1 6% | 24 (4) | 6 (67) | 2 (22) | <0.001*† |

| Apical LS, % | —20.6 (−1 5.6 to —23.0) | —21.5 (−1 8.1 to —22.7) | —25.9 (—24.2 to —28.7) | 0.012* |

| RELAPS ratio, unitless | 1.21 (1.01 to 1.59) | 1.04 (0.67 to 1.14) | 0.84 (0.54 to 0.87) | <0.001* |

| RELAPS | 19 (76) | 6 (60) | 0 (0) | 0.002* |

| CMR Measurements | ||||

| Mean wall thickness, mm | 10.4 (9.7 to 11.3) | 8.9 (8.0 to 10.2) | 7.8 (6.8 to 9.1) | <0.001*† |

| LV massindexed, g/m2 | 84.5 (75.6 to 103.1) | 78.7 (54.1 to 83.5) | 54.5 (48.8 to 57.6) | <0.001* |

| LV EDVi, cm3/m2 | 68.0 (62.6 to 76.0) | 77.3 (68.2 to 98.1) | 69.8 (55.7 to 73.4) | 0.25 |

| LV ESVi, cm3/m2 | 33.6 (26.1 to 46.1) | 35.9 (26.2 to 44.5) | 27.2 (18.6 to 30.3) | 0.098 |

| LV EF, % | 49.9 (44.9 to 59.0) | 53.5 (47.6 to 65.0) | 66.1 (56.8 to 69.2) | 0.004* |

| LGE | 25 (100) | 9 (90) | 2 (20) | <0.001* |

| ECV, % | 0.514 (0.465 to 0.564) | 0.507 (0.473 to 0.588) | 0.377 (0.316 to 0.406) | <0.001* |

| ECV >0.41 | 23 (100) | 9 (90) | 2 (20) | <0.001* |

| [18F]florbetapir PET/CT | ||||

| Global RI, min−1 | 0.110 (0.078 to 0.139) | 0.097 (0.070 to 0.124) | 0.058 (0.042 to 0.087) | 0.003* |

| RI >0.06 min−1 | 25 (100) | 9 (90) | 5 (50) | 0.001* |

Values are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

p < 0.05 for Active Cardiac AL vs. Active Non-cardiac AL.

p < 0.05 for Active Cardiac AL vs. Remission Cardiac AL.

AL = light-chain amyloidosis; CMR = cardiovascular magnetic resonance; DT = E wave deceleration time; ECV = extracellular volume; EDV = end-diastolic volume; EDVi = end-diastolic volume indexed; ESV = end-systolic volume; ESVi = end-systolic volume indexed; IVS interventricular septum; LA = left atrial; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; LS = longitudinal strain; LV = left ventricular; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; RELAPS = relative apical sparing; RI = retention index; other abbreviations as in Table 1

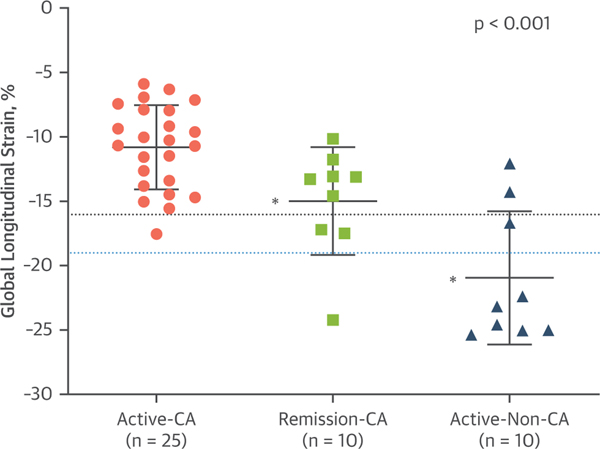

LV function was the lowest in this group. LVEF was 50 ± 11%. GLS was markedly reduced (median GLS, −1 1%; IQR: −8% to −1 3%), and 76% of the subjects displayed a typical apical sparing pattern (Figures 2 and 3). The median E/A ratio, deceleration time, E/e′, and e′ values were consistent with a restrictive filling pattern.

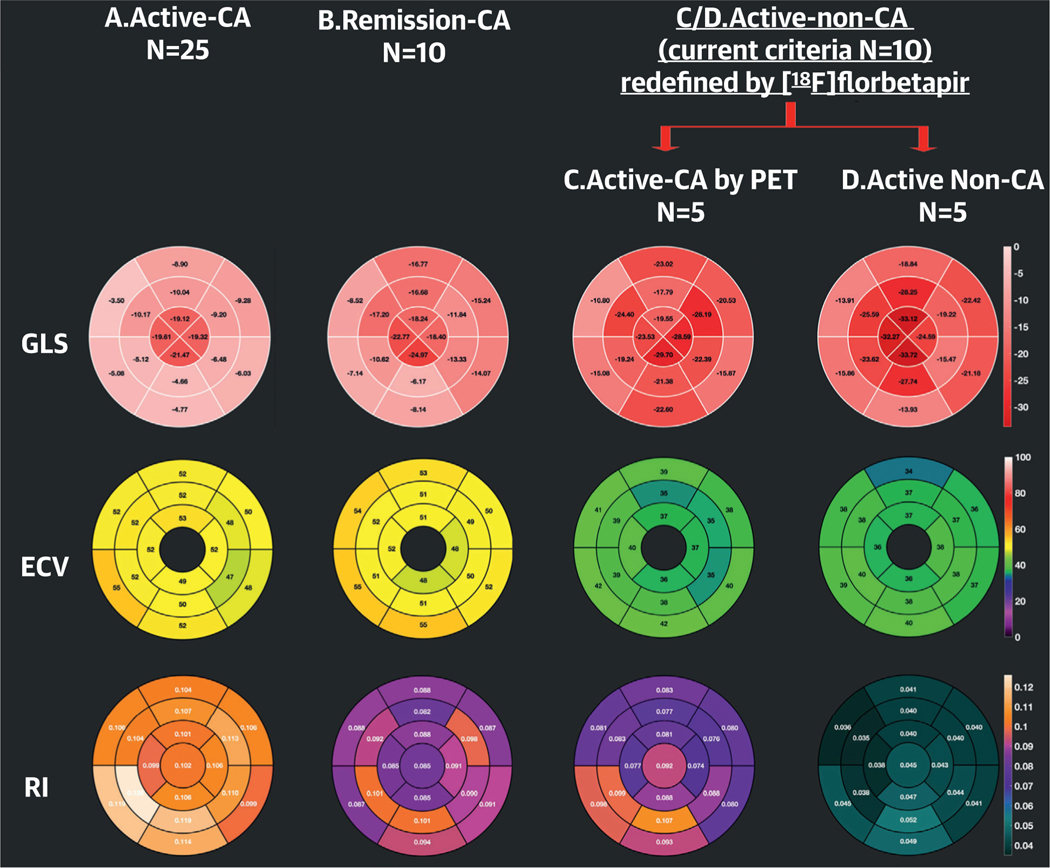

FIGURE 2. Segmental Distribution of GLS, ECV, and [18F]florbetapir RI in the Entire Study Cohort.

A 16-segment polar plot of GLS (top), 16-segment polar plot of ECV (second row), and a 17- segment polar plot of [18F]florbetapir RI (bottom row) in (left to right) active cardiac amyloidosis (A), remission cardiac amyloidosis (B), and (C) active AL-no CA with a [18F]florbetapir RI >0.06 min−1 and (D) active AL-no CA with a [18F] florbetapir RI <0.06 min−1. Values represented in the polar plots are the median of each parameter. Subjects in groups A and B have impaired GLS, whereas those in groups C and D have normal GLS. ECV is expanded in all 4 groups but more markedly in A and B than in C and D. Cardiac amyloid deposition detected by [18F] florbetapir PET/CT is highest in group A and lowest in group D. Abbreviations are as in Figure 1.

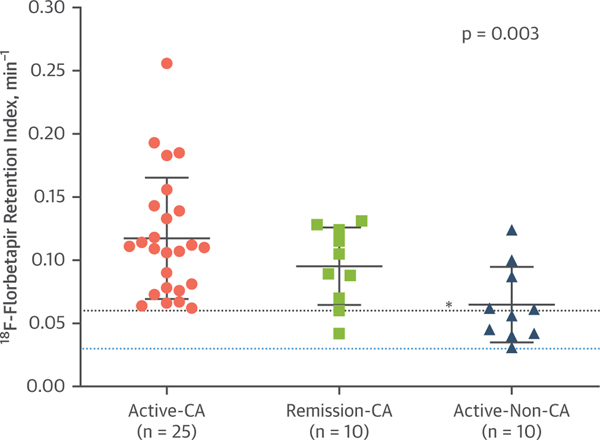

FIGURE 3. Distribution of GLS Values in the Study Groups.

The dotted black line represents the cutoff value to diagnose presence or absence of cardiac amyloidosis. The dotted blue line represents the upper threshold of normal observed in healthy controls, as reported in other studies. The p value listed in the figure is the across group comparison. *p < 0.005 for between-group differences with active-CA as the reference group. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

REMISSION CARDIAC AL GROUP.

Despite free light chain remission, 70% of subjects in the remission-CA cohort had heart failure with NYHA functional class II or greater symptoms and elevated serum cardiac biomarker levels. However, NT-proBNP and troponin T levels were significantly lower in this group than in the active-CA cohort. The remission-CA cohort showed evidence of myocardial structural changes (indexed LV mass, LGE, ECV), amyloid deposition ([18F]florbetapir RI), and LV systolic (LVEF, GLS) and diastolic dysfunction (e′ values and E/e′ ratio) but not as marked as those in the active-CA group (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences between the [18F] florbetapir RIs in the remission-CA group and those in the active-CA group (Figure 4); however, the mean LV wall thickness by CMR was lower, 8.9 mm (IQR: 8.0 to 10.2 mm) vs. 10.4 mm (IQR: 9.7 to 11.3 mm) (p = 0.006), respectively.

FIGURE 4. Distribution of [18F]Florbetapir RI Values in the Study Groups.

Groups are defined by the presence of consensus criteria for cardiac involvement and AL disease activity. The dotted blue line represents the cutoff value to diagnose the presence or absence of cardiac amyloidosis. The dotted black line represents the upper threshold of normal observed in healthy controls, as reported in other studies. The p value is the cross-group comparison. *p < 0.005 for between-group differences with active-CA as the reference group. Abbreviations are as in Figure 1.

ACTIVE NONCARDIAC AL GROUP.

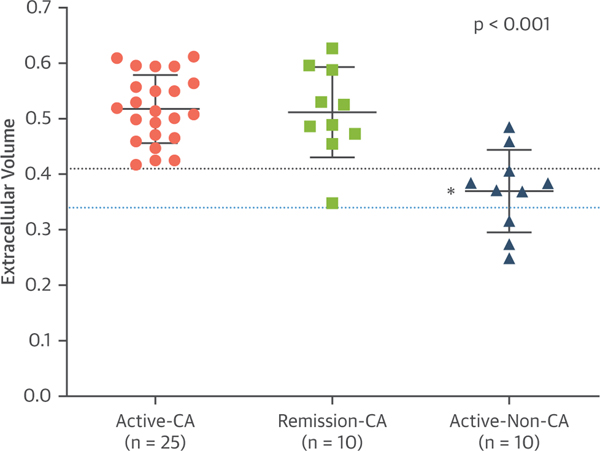

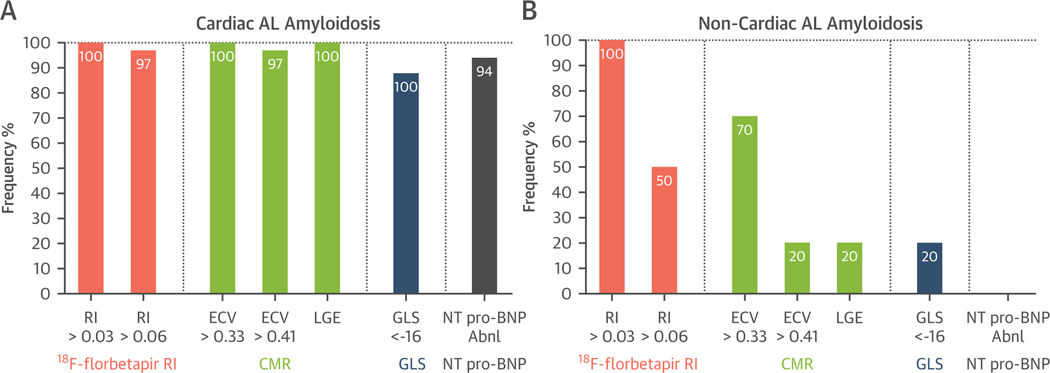

Subjects with active systemic AL amyloidosis but no evidence of cardiac involvement had, by definition, normal LV wall thickness (≤12 mm) on echocardiography and normal serum cardiac biomarker levels. ECV was above the upper limit of normal in 70% of this group (Figure 5); the mean ECV was 0.370 ± 0.074. LGE was present in 2 of the subjects, both of whom had an abnormal ECV. All 10 of the subjects in the active-non-CA cohort showed some degree of myocardial amyloid deposition with [18F]florbetapir RI >0.03 min−1, notably, one-half of those subjects demonstrated amyloid deposition compatible with the active-CA cohort ([18F]florbetapir RI >0.06 min−1) (Figure 4). The median amyloid burden, as measured by [18F]florbetapir RI, was significantly lower in this group than in the other 2 groups, 0.058 min−1 (IQR: 0.042 to 0.087 min−1) (Table 2). Despite these changes, cardiac function GLS (Figure 5) and LVEF were preserved in most of these subjects. None of the subjects had evidence of restrictive cardiac filling (Table 2).

FIGURE 5. Distribution of ECV Values in the Study Groups.

The dotted blue line represents the cutoff value to diagnose the presence or absence of cardiac amyloidosis. The dotted black line represents the upper threshold of normal observed in healthy controls, as reported in other studies. The p value listed in the figure is the cross-group comparison. *p < 0.005 for between-group differences with active-CA as the reference group. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

CARDIAC STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL PARAMETERS STRATIFIED BY SERUM NT-proBNP LEVELS.

Subjects with serum NT-proBNP levels above age-adjusted normal limits comprised 68% of the study cohort. These subjects were older and had higher mean creatinine levels. Mean LV wall thicknesses, LV mass indexes, LGE and ECV results, and quantitative [18F]florbetapir PET RIs were higher, and mean native GLS values were nearly universally impaired in the cohort with abnormal NT-proBNP compared to those with normal NT-proBNP.

CARDIAC STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL PARAMETERS STRATIFIED BY LV WALL THICKNESS.

Subjects with cardiac amyloidosis by conventional criteria, LV wall thickness >12 mm by echocardiogram, comprised 80% (35 of 45 patients) of the study cohort. In these subjects, serum NT-proBNP and advanced imaging metrics of GLS, LGE, ECV, and [18F]florbetapir PET RIs were almost universally abnormal (Figure 6A) compared to those in the cohort with normal wall thickness and normal NT-proBNP levels (no cardiac amyloidosis by conventional criteria) (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6. Prevalence of Abnormal Indexes of Cardiac Amyloid Deposition in Cardiac AL Groups.

(A) Active-Ca and remission-CA and (B) in the noncardiac active CA group. Conventional criteria for the diagnosis of cardiac AL amyloidosis (A) identifies subjects with advanced infiltration with ubiquitous abnormalities in [18F]florbetapir RI, LGE, ECV, GLS, and NT-proBNP. Importantly, in subjects diagnosed as not having cardiac involvement by conventional criteria (B), a substantial proportion were identified to have early cardiac involvement by imaging biomarker abnormalities in RI, ECV, LGE, and GLS. NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

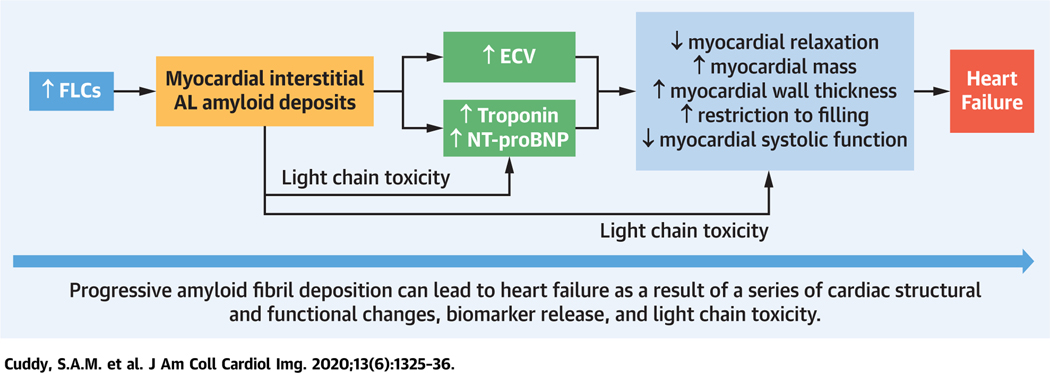

To the best of the present authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate molecularly targeted imaging of cardiac amyloidosis using [18F]florbetapir PET in combination with imaging of cardiac structure and function using advanced CMR and echocardiography. There were several important findings about cardiac AL amyloid deposition across the spectrum of systemic AL amyloidosis. Although increased wall thickness, according to echocardiography, was always associated with either biomarker or CMR evidence of abnormality and impaired GLS, subjects deemed to have no cardiac amyloidosis based on normal wall thickness and serum biomarkers sometimes showed nonspecific abnormalities on CMR (Central Illustration). Minor abnormalities on echocardiography or CMR, such as slight increase in wall thickness or mild expansion of ECV, are nonspecific and can be seen in other pathologies, including poorly controlled hypertension (14). In contrast, [18F]florbetapir uptake was present in all the AL subjects, regardless of abnormalities in the other tests results, suggesting that this imaging technique may be positive even when other noninvasive cardiac imaging test results are negative. That a positive [18F]florbetapir scan truly reflects the presence of cardiac amyloidosis is strongly suggested by the finding that amyloid burden, estimated directly by [18F]florbetapir RI, was highest in the active-CA group, followed by the remission-CA group, with the lowest burden in the active-non-CA group. Previously published data (6) showed that [18F]florbetapir uptake (and other amyloid targeted PET tracer uptake) (17,18) was absent in healthy volunteers free of systemic amyloidosis.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Imaging From Early to Advanced Stages of Myocardial AL Amyloid Deposition.

The inciting event in the pathogenesis of AL amyloidosis in the heart is AL amyloid deposition, which can now be imaged by imaging with a targeted amyloid tracer [18F] florbetapir PET/CT. Amyloid deposition expands ECV and releases cardiac biomarkers, which are probably very early manifestations in AL cardiac amyloidosis. With progressive myocardial AL amyloid deposition, several typical cardiac structural and functional changes become evident, which are likely to represent more advanced stages of AL amyloidosis and can be imaged by echocardiography. Heart failure typically indicates advanced amyloid infiltration that is typically associated with poor prognosis. Light-chain toxicity also has a role in myocardial dysfunction. [18F]florbetapir = fluorine-18-labeled florbetapir; ECV = extracellular volume; FLC = free light chain level; PET/CT = positron emission tomography/computed tomography

ECV by CMR, assumed to be related to amyloid burden, was higher in the cardiac amyloid group than in the “non-CA” group, as was the florbetapir RI. These findings confirm that minor changes in ECV by CMR are due to amyloid deposition rather than other more common pathologies in this cohort. Mildly expanded ECV has been described in subjects with systemic AL amyloidosis who do not have classical echocardiographic features (5). Because of a lack of direct amyloid imaging techniques, these patients were labeled, appropriately, as having “probable” cardiac amyloidosis (5). This study showed, albeit in a small cohort, that amyloid deposition is the cause of early increases in ECV and that this deposition can be identified by florbetapir PET before changes can be seen in LGE, suggesting the existence of a novel “Stage B” heart failure phenotype in AL amyloidosis (19).

Early studies of the sensitivity of an elevated level of NT-proBNP for diagnosing AL cardiac amyloidosis in patients with systemic AL amyloidosis were based predominantly on echocardiography as the reference standard (2,3). Those studies reported that no patient with cardiac involvement was found to have an NT-proBNP concentration <55 pmol/l (465 pg/ml) and concluded that an elevated NT-proBNP was 100% sensitive for cardiac involvement in AL amyloidosis (3). Using targeted amyloid imaging, the present study confirmed that, in contrast, a significant proportion of subjects have substantial cardiac amyloid deposition despite a normal age-adjusted concentration of NT-proBNP.

Martinez-Naharro et al. (20) reported CMR findings in 31 patients with AL cardiac amyloidosis before and after chemotherapy. ECV decreased in 13 patients (42%), but only 7 subjects had a concordant decrease in LV mass. This suggests remodeling of the LV in some patients. In the present comparison among cohorts, mean LV mass, ECV, and florbetapir retention did not differ significantly between untreated active-CA and those in remission.

However, serum biomarker levels were lower and the GLS was less impaired in the remission-CA group. Improvement in symptoms and biomarkers with chemotherapy are believed to be due to a combination of decreased amyloid burden and elimination of light chain toxicity. Although the present findings are not longitudinal the group differences between the remission and the active AL-CA groups further support the concept of light chain toxicity. Despite a similar burden of amyloid by LV mass, ECV, and florbetapir retention, myocardial functional metrics were better in the remission group than in the active AL-CA group.

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

All subjects enrolled in the study were carefully selected based on study criteria for AL amyloidosis, and the results of this study are therefore applicable to a similar cohort of subjects. As the subjects in the 3 groups were different, longitudinal changes in these various imaging markers cannot be established within groups in this cohort. As multiple variables have been tested in this study, there is an inflated risk of type I error. The remission groups were recruited at different times following chemotherapy, so response to therapy is not captured at a uniform time point in the groups; however, all subjects had maintained normal serum light chain levels for >12 months. Ongoing work will establish how imaging metrics reflect longitudinal changes and response to therapy. In place of a healthy control group, this study used the authors’ prior experience with [18F] florbetapir PET/CT RI to inform normal thresholds. Subjects with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min/1.73 m2 were excluded, which also excluded a small proportion of patients with systemic AL amyloidosis. Lack of correlation between endomyocardial biopsy in the active-non-CA group and imaging findings is a limitation of the study; however, autoradiography data previously published by this group demonstrate the specificity of [18F]florbetapir uptake for amyloid deposits. Endomyocardial biopsy would be far too invasive for patients without elevated biomarkers, and furthermore, sampling difficulties would still prevail, due to the often patchy and microscopic distribution of cardiac amyloid.

CONCLUSIONS

This imaging study of a well-defined population of systemic amyloidosis patients, all of whom were initially evaluated at amyloidosis centers of excellence, has demonstrated that the definition of cardiac amyloid involvement is a “moving target,” with earlier diagnosis occurring as techniques become increasingly sophisticated. It is clear that many patients who do not meet current consensus criteria for cardiac involvement in AL amyloidosis have cardiac amyloid deposition, as determined by florbetapir retention, but the clinical significance when combined with other imaging findings remains to be defined. Although the present data confirm the long-recognized view that AL amyloidosis is a multi-organ disease with a wide range of phenotypic expressions, data also strongly suggest that serial measurements of [18F]florbetapir RI may be a better and more sensitive tool for better understanding the cardiac changes that occur with hematologic remission in this disease.

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE:

Cardiac amyloid deposition can be detected in patients with systemic AL amyloidosis by using advanced imaging techniques prior to increases in wall thickness and elevation in circulating biomarkers of cardiac injury. These techniques can identify patients with stage B heart failure. Patients in hematologic remission for at least 1 year have persistent amyloid deposition.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK:

Although indirect imaging parameters, such as ECV and GLS, provide information on the severity of amyloid deposition, direct imaging with [18F]florbetapir PET allowed detection of amyloid burden below the thresholds recognized for indirect imaging parameters. This improved sensitivity will allow earlier detection of cardiac involvement. These direct and indirect markers require investigation longitudinally to establish which is the best marker for tracking disease progression and response to therapy, and for predicting mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank each of the study subjects for their participation. The authors also thank Pranav Dorbala for contributing to Figure 2.

Supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL093148 (Dr. Liao), HL128135 (Dr. Liao), HL099073 (Dr. Liao), HL130563 (Drs. Dorbala and Falk), and HL094301 (Dr. Bravo); and by American Heart Association grant AHA 16 CSA 28880004 (Drs. Liao and Dorbala). Dr. Dorbala has received research support from U.S. NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grants R01 HL130563 and American Heart Association grant AHA 16 CSA 28880004. Dr. Dorbala’s institution has received research grant from Pfizer, GE Healthcare, and Advanced Accelerator Applications. Dr. Ruberg has received research support from U.S. NIH/NHLBI grant R01 HL130563 and R01 HL139671; is a consultant for Pfizer; and has received research support from Eidos Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Akcea Therapeutics. Dr. Yee is a consultant for Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Glaxo Smith Kline, Janssen, Oncopeptides, Sanofi, and Takeda. Dr. Di Carli has received research support from Gilead Sciences and Spectrum Dynamics; and is a consultant for Bayer and Janssen. Dr. Sanchorawala has received research support from Takeda, Celgene, Janssen, Prothena; and sits on the scientific advisory board for Caleum Biosciences. Dr. Landau is a consultant for Celgene, Takeda, Janssen, Prothena, Pfizer, and Juno; and has received research support from Amgen, Spectrum, and Takeda. Dr. Dorbala is a consultant for and has received personal consulting fees from Pfizer and GE Healthcare. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AL amyloidosis

light chain amyloidosis

- CA

cardiac amyloidosis

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- dFLC

free light-chain difference

- ECG

electrocardiography

- ECV

extracellular volume

- LGE

late gadolinium enhancement

- LV

left ventricular

- PET

positron emission tomography

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging author instructions page.

REFERENCES

- 1.Falk RH, Alexander KM, Liao R, Dorbala S. AL (light-chain) cardiac amyloidosis: a review of diagnosis and therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68: 1323–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gertz MA, Comenzo R, Falk RH, et al. Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis, Tours, France, 18–22 April 2004. Am J Hematol 2005;79: 319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palladini G, Campana C, Klersy C, et al. Serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide is a sensitive marker of myocardial dysfunction in AL amyloidosis. Circulation 2003;107:2440–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maceira AM, Joshi J, Prasad SK, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation 2005;111:186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banypersad SM, Sado DM, Flett AS, et al. Quantification of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in systemic AL amyloidosis: an equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:34–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorbala S, Vangala D, Semer J, et al. Imaging cardiac amyloidosis: a pilot study using [18]F-florbetapir positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Img 2014;41:1652–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner T, Page J, Burniston M, et al. Extracardiac ([18])F-florbetapir imaging in patients with systemic amyloidosis: more than hearts and minds. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;45:1129–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park MA, Padera RF, Belanger A, et al. 18F-florbetapir binds specifically to myocardial light chain and transthyretin amyloid deposits: autoradiography study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8: e002954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osborne DR, Acuff SN, Stuckey A, Wall J. A routine PET/CT protocol with simple calculations for assessing cardiac amyloid using 18F-Florbetapir. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2015;2: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015; 16:233–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bravo PE, Fujikura K, Kijewski MF, et al. Relative apical sparing of myocardial longitudinal strain is explained by regional differences in total amyloid mass rather than the proportion of amyloid deposits. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2019;12: 1165–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujita N, Duerinekx AJ, Higgins CB. Variation in left ventricular regional wall stress with cine magnetic resonance imaging: normal subjects versus dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 1993; 125:1337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawel-Boehm N, Maceira A, Valsangiacomo-Buechel ER, et al. Normal values for cardiovascular magnetic resonance in adults and children. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015;17:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mongeon FP, Jerosch-Herold M, Coelho-Filho OR, et al. Quantification of extracellular matrix expansion by CMR in infiltrative heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2012;5:897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosmini S, Bulluck H, Captur G, et al. Myocardial native T1 and extracellular volume with healthy ageing and gender. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;19:615–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelan D, Collier P, Thavendiranathan P, et al. Relative apical sparing of longitudinal strain using two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography is both sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. Heart 2012;98: 1442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoni G, Lubberink M, Estrada S, et al. In vivo visualization of amyloid deposits in the heart with 11C-PIB and PET. J Nucl Med 2013;54: 213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Law WP, Wang WY, Moore PT, Mollee PN, Ng AC. Cardiac amyloid imaging with 18F-florbetaben positron emission tomography: a pilot study. J Nucl Med 2016;57:1733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah AM, Claggett B, Loehr LR, et al. Heart failure stages among older adults in the community: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation 2017;135:224–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Naharro A, Abdel-Gadir A, Treibel TA, et al. CMR-verified regression of cardiac AL amyloid after chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol Img 2018;11:152–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]