Abstract

We systematically reviewed the research on patients’ and prescribers’ perceptions of, and self-reported behaviors prompted by, exposure to direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA)1 of prescription drugs that occurs in the context of a clinical encounter. This research offers an important perspective on the broader goal of incorporating patient and prescriber voices in decision-making. Outcomes included patient information seeking, medication adherence, patient requests for DTCA-promoted prescription drugs, prescribing behaviors, and perceptions of the patient–prescriber relationship and interactions. We searched PubMed and other databases from 1982–2017 and identified 38 studies meeting our study criteria. Of these, 24 studies used patient-reported outcomes and 18 used prescriber-reported outcomes (four used both). Studies suggested some potential benefits of exposure to DTCA, including patients’ enhanced information-seeking, increased patient requests for appropriate prescriptions (when addressing potential underuse) and patients’ perceptions of higher-quality interactions with prescribers. Most prescribers perceived a neutral influence on the quality of their clinical interactions with patients regarding DTCA. Harms included patients receiving prescriptions for drugs that were not appropriate for them or that the patients did not need, and the potential for DTCA to interfere with medication adherence in some populations, such as those with mental illness. The potential benefits of DTCA on the patient–provider encounter must be balanced with the potential for harms.

Keywords: prescription drugs, advertising, direct-to-consumer, drug promotion

INTRODUCTION

Direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) of prescription drugs is one of the most common forms of health communication that reaches the U.S. public. American adults spend an average of 4.5 hours per day watching television (The Nielsen Company, 2016). This can translate to over 30 hours of DTCA per year (Brownfield, Bernhardt, Phan, Williams, & Parker, 2004), but this estimate does not include exposure to other sources including print, radio, and Internet-based prescription drug promotion. As of 2016, pharmaceutical company expenditures on DTCA reached $5.6 billion (McCaffrey, 2017).

Exposure to DTCA can have both positive and negative effects on health care choices and outcomes. Positive effects include empowering patients by educating them about the benefits and risks of products, increasing disease awareness, and ultimately improving health outcomes by addressing underuse of potentially beneficial drugs (Almasi, Stafford, Kravitz, & Mansfield, 2006; Gellad & Lyles, 2007). DTCA can also have a positive effect on the patient–prescriber relationship, leading to more frequent and useful discussions about health and treatment generally (Aikin, Swasy, & Braman, 2004). Negative effects include the potential for patients to be misled by communications designed to persuade rather than inform, and overuse of drugs that patients may not necessarily need (Almasi et al., 2006; Mintzes, 2012). Further, it has been suggested that DTCA may have a detrimental effect on the patient–prescriber relationship, undermining the role of the prescriber in prescription drug-related decisions, altering patient expectations for these drugs, and creating pressures to prescribe (American College of Physicians, 2006; Mintzes, 2012; Robinson et al., 2004).

Consistent with the growing emphasis among medical and health policy communities on informed and patient-centered decision making, various organizations and funding bodies seek to better understand both the patient and prescriber perspectives on issues related to promotion of medical products (Selby, 2012; U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2015), and to encourage the use of patient-reported outcomes. Thus, assessment of the patient and prescriber perspectives on DTCA is important when considering the larger goal of informed decision making and attention to the patient (and prescriber) voice.

Previous systematic reviews have rigorously evaluated the potential benefits and harms of DTCA on clinical outcomes (Gilbody et al., 2005; Mintzes et al., 2012). The authors concluded from their reviews that DTCA is associated with increased prescription of advertised products and can have a substantial effect on patient requests for these products.However, due to the strict eligibility criteria, largely absent from these reviews were observational studies that evaluated patient report of health behaviors as a result of DTCA, such as information seeking and medication adherence, or patient perceptions of the content or quality of interactions with physicians surrounding these drugs.

Our study builds on previous reviews by addressing the following research questions: (1) what are patients’ and providers’ perceptions of DTCA as they relate to interactions and behaviors that occur in a clinical setting? (2) what are the limitations of and knowledge gaps in this literature?

METHODS

Data Sources and Selection

We developed our search strategy with consultation from an experienced research librarian as part of a larger investigation on patient and provider perceptions of DTCA. Medical Search Terms (MeSH) and title/abstract keywords for MEDLINE® (via PubMed) centered around DTCA and assessment of health attitudes, behaviors, and practice (Online Supplement Appendix A). We adapted search terms used in MEDLINE for use with the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We identified additional studies for inclusion by searching reference lists of seminal studies, forward-tracing relevant studies using Google Scholar and Web of Science, and through consultation with content-area experts.

We searched for peer-reviewed English-language studies published between 1982 and December 2017. We included all research designs and only original research studies conducted in either the United States or New Zealand, because these were the only countries where DTCA was allowed by law at the time of this review. We excluded environmental scans of the literature, editorials, and commentaries.

For this review, we defined “patients” as general populations 18 years of age or older and “prescribers” as physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. DTCA included marketing or promotional communications delivered through television, print, radio, and web. Based on our preliminary review of the evidence, we identified the following outcomes related to exposure to DTCA for inclusion in our review: patient information seeking from a health care prescriber; patient–prescriber discussions about drugs (frequency, content or quality, such as perceptions of the discussion as positive or negative); patient visits to a health care prescriber; patient and prescriber perceptions of their relationship; patient requests for prescription drugs; prescribing behavior in response to these requests; patient adherence to prescribed drugs.

Our focus was on assessments of self-reported behavior and clinical interactions. As such, we excluded studies that did not directly measure patient or prescriber perceptions or their reported behaviors in relation to DTCA (e.g., we excluded studies that only analyzed medical claims data or market share information as the main outcome). We excluded studies that measured only behavioral intent (e.g., intent to seek information or ask for a prescription) or asked participants to respond to hypothetical scenarios, as our focus was on actual rather than potential behaviors. Finally, to focus our review, we excluded studies that reported only on awareness or exposure to DTCA, attitudes toward DTCA more generally, or only on comprehension or readability of DTCA information. Our review does not include assessments of over-the-counter drugs.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two members of the research team independently reviewed titles and abstracts and full-text articles against our predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A separate senior team member resolved any disagreement about inclusion or exclusion of any specific study.

We developed a standardized data abstraction table to collect relevant data from included studies. One member of the team extracted information from each article and a senior team member checked this information for accuracy. We tabulated study characteristics across the body of evidence and synthesized information narratively. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes, we did not conduct a meta-analysis of the studies’ findings.

RESULTS

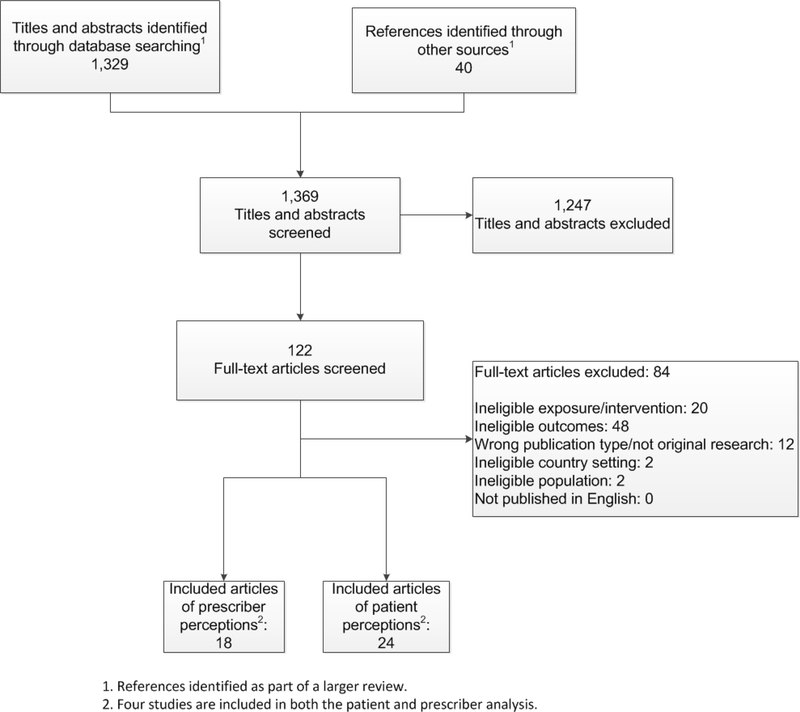

Our search results are shown in Figure 1. The electronic database search yielded 1,329 unduplicated citations and we identified another 40 studies for potential inclusion from manual searches. After removing nonrelevant titles and abstracts, we retained 124 studies for full-text review. Of these, 38 met the inclusion criteria described above. Twenty four studies used patient-reported outcomes and 18 used prescriber-reported outcomes; four used both (Aikin et al., 2004; Allison-Ottey, Ruffin, Allison, & Ottey, 2003; Mintzes et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Literature Flow Diagram

Table 1 provides a brief summary of the included 38 studies (see Online Appendix B for detailed information on each included study). Thirty-six were cross-sectional surveys; of these, two included patients not exposed to DTCA as a comparison group for analyses. We identified one RCT (Kravitz et al., 2005) and one qualitative focus group study (Tentler et al., 2008). Whereas most of the patient studies surveyed a general population of adults (17), we identified six studies that focused on patients with specific medical conditions, and three that had a strong focus on either African American or Hispanic populations (Allison-Ottey et al., 2003; Allison-Ottey, Ruffin, & Allison, 2002; Lee & Begley, 2010). Thirty-one studies assessed the effects of prescription drug DTCA more generally, whereas seven studies assessed the effects of a specific drug type or condition.. Whereas most of the provider studies surveyed only physicians (17), four studies surveyed other prescribers (e.g., nurse practitioners). Sample characteristics ranged from small, convenience samples of single-practice sites to random samples drawn from large prescriber membership databases.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies2

We organize our findings below first by patient versus prescriber-reported outcomes. Within each major grouping, we further organize our findings by the outcome of interest. Due to space constraints, we largely focus our discussion on studies with either large, population-based samples or those with more rigorous designs

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Information seeking and discussions about drugs, health care visits

Patients reported that DTCA prompted them to seek more information from health care professionals about a condition or drug or have discussions about them in 22 studies (Online Supplement Appendix C). For example, a large, national survey conducted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002 Aikin et al. (2004) found that 43% of respondents sought additional information as a result of DTCA; 89% of these respondents said they obtained information from their doctor, while others sought information from other health care professionals (51% from pharmacists) or other sources (e.g., 38% from the internet). Other studies reported that information seeking was associated with having a chronic condition (Sumpradit, Fors, & McCormick, 2002), having a more positive attitude toward DTCA (Herzenstein, Misra, & Posavac, 2004; Sumpradit et al., 2002), greater trust in DTCA media (Huh, DeLorme, & Reid, 2005), and greater perceived value of the DTCA information (Singh & Smith, 2005).

Very rarely did patients report that DTCA was the sole reason for scheduling a medical visit (Aikin et al., 2004; Murray, Lo, Pollack, Donelan, & Lee, 2004; Robinson et al., 2004; Spake & Joseph, 2007). Two of the four studies that assessed this outcome were conducted with large, national samples (Aikin et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2004). In the previously described FDA survey, only a small percentage of respondents (4%) reported seeing their doctors exclusively because they wanted more information after viewing DTCA (Aikin et al., 2004). Murray and colleagues (2004) conducted a large, nationally representative telephone survey of 3,209 adults, and found that 7% of respondents reported discussing information from a DTCA with their physicians and that 2% scheduled a visit to a physician specifically or partly to discuss information they obtained from DTCA. The same survey found that those with lower education levels, who had chronic disease, and who were Hispanic were more likely to schedule an appointment for preventive care or a checkup as a result of DTCA. In a study of a local, random sample of 500 adults, 11% of participants indicated that DTCA motivated them to seek medical care (Robinson et al., 2004). Similarly, 11% of a convenience sample of 250 pharmacy customers reported they had scheduled an appointment with a doctor based on symptoms they saw depicted in DTCA (Spake & Joseph, 2007). More commonly, patients reported that, during a medical appointment they had already scheduled, they discussed a condition or drug depicted in DTCA. About 35% of respondents in a large, nationally representative survey of 3,000 adults (Weissman et al., 2003) stated that they were prompted by DTCA to discuss a specific drug or health concern with their physicians during an already-scheduled clinical visit.

Request for prescription drugs, medication change/referrals

Eighteen studies reported on patient requests for prescription drugs and related outcomes, such as receipt of new prescriptions and medication change as a result of DTCA (Online Supplement Appendix C). The frequencies in which these outcomes occurred varied widely across studies Here, we discuss the study findings from four large, probability-based surveys. The FDA survey previously described found that 32% of patients reported having asked about a drug to treat their condition as a result of DTCA. Of these patients, 39% asked for a specific brand of drug, and of these, about half reported that they received the drug they had asked about (Aikin et al., 2004). More than half of respondents in the previously described study by Murray and colleagues (2004) reported having requested at least one medical intervention from their physicians as a result of DTCA; most requests were for changes in medications, followed by tests and referrals to specialists for conditions that were described in the DTCA. Of those who made requests, 55% reported receiving the intervention they requested. This outcome was more common in white patients and those with higher socioeconomic status. A national, web-based survey of over 2,000 adults (Brodie, 2001) found that, of the 30% of respondents who reported talking to their doctors about a drug promoted in DTCA, 44% reported receiving the requested medication. However, an important question not addressed in the body of research identified in our review is whether new drugs prescribed as a result of DTCA were appropriate (the patient was treated for an overlooked condition or received symptom relief for an existing condition) or if they resulted in overprescribing and overtreatment of the patient.

Medication adherence

We identified two studies that assessed patient adherence to medications as a result of DTCA (Bell, Taylor, & Kravitz, 2010; Green et al., 2017). In a convenience sample of 148 online depression support group members, 26% said that DTCA reminded them to take their presently prescribed medications (Bell et al., 2010). However, the study did not specifically assess the alternative outcome, that is, whether exposure to DTCA caused others to alter or discontinue use of their prescribed medicine In contrast, a study of 256 patients in a mental health clinic found that those who self-reported exposure to DTCA had greater nonadherence to their prescribed medications (defined as missing medication on two or more days out of seven) than those who reported no exposure to DTCA (OR = 5.04; CI = 2.90–8.75, p < .001), and this association persisted after adjusting for sex, age, education level, and diagnosis (Green et al., 2017). In the same study, 61% of patients who reported exposure to DTCA were nonadherent to their medications, and 59% of these patients reported that they changed how they took their medication or discontinued it specifically because of viewing the information on potential side effects. Conversely, 26% of patients not exposed to DTCA were nonadherent to their medications. Although this finding suggests that DTCA may be a possible risk factor for medication nonadherence, it is unclear if this finding can be generalized to other patient populations and medical conditions.

Patient–prescriber relationship

Findings from seven studies reporting on patient perceptions of the patient–prescriber relationship as a result of exposure to DTCA were mixed (Online Supplement Appendix C). The FDA survey previously described found that 43% of participants felt that DTCA helped them to have better discussions with their prescribers (Aikin et al., 2004). In this study, 10% of patients reported some hesitation in talking to their physicians about a drug because of concerns that it would signal distrust of their prescriber. The previously described national survey by Murray and colleagues (2004) found that, of the survey respondents who reported discussing DTCA during a visit, 23% reported an improved relationship as a result, 72% reported no change in the relationship, and 5% reported a worsened relationship. Respondents who requested a specific drug but did not receive it were more likely to report a worsened relationship. This study also found that 5% of patients reported feeling a greater sense of control due to DTCA-prompted discussion, and very few patients reported serious dissatisfaction with their visit or noted that their prescriber seemed challenged by their request for information as a result of DTCA. Findings from studies with local samples yielded similarly mixed results with regard to the extent to which DTCA improved the patient-provider relationship (Huh et al., 2005).

Prescriber-reported Outcomes

Information seeking and discussion about drugs

Ten studies assessed prescribers’ perspectives on patient information-seeking prompted by DTCA and discussions about these drugs (Online Supplement Appendix D). In a survey of 2,008 nationally representative physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, Kelly and colleagues (2013) found that 76% of providers reported that their patients had initiated discussions about brand-name prescription drugs, but they were not sure about the extent to which these conversations were prompted by DTCA. A set of studies with practicing African American physicians found that about 90% had ever been asked their medical opinion concerning a prescription drug because of DTCA (Allison-Ottey et al., 2003; Allison-Ottey et al., 2002). An assessment of 168 prescribers’ clinical encounters with patients (1,641 encounters) within a Colorado practice-based research network found that among those encounters where patients had asked about a medication, 20% of those inquiries were prompted by DTCA, whereas slightly more (32%) were prompted by friends and family, and one-third reported “other” (Parnes et al., 2009). In a study by Weissman and colleagues (2004), among 643 randomly selected physicians, DTCA-initiated discussions occurred in only a small proportion of office visits (3%), but about one-half of physicians reported having a DTCA-initiated discussion with a patient within the past week.

Patient requests, prescribing behavior, medication changes/new diagnoses

Reports regarding prescribing behavior as a result of DTCA-prompted requests from patients varied across studies and measures (Online Supplement Appendix D). In the above-mentioned assessment of 1,641 clinical encounters in a Colorado health network, requests for prescription drugs prompted by DTCA were very uncommon, occurring in only 3.5% of the encounters (Parnes et al., 2009). Further, these inquiries were more frequent in the community clinic samples than in the private clinic samples (7.2% vs. 1.7%, p < .001) (Parnes et al., 2009). In the previously described national survey of providers by Kelly and colleagues (2013), 10% of providers reported that a patient had asked for a prescription drug by name, prompted by DTCA, within the past month. The same study found that 85% reported very little or no pressure to prescribe drugs requested by patients, and only 5% of prescribers who felt pressure reported that they prescribed because of this pressure. Other studies assessed perceived pressures to prescribe and yielded varying responses (Aikin et al., 2004; Allison-Ottey et al., 2002; Fortuna et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2013; Lipsky & Taylor, 1997; Paul, Handlin, & Stanton, 2002; Robinson et al., 2004; Viale & Sanchez Yamamoto, 2004), with some surveys finding that 50% or more of providers reported some pressure to prescribe (Aikin et al., 2004; Lipsky & Taylor, 1997). In the previously described study by Weissman and colleagues (2004), among the conversations initiated by DTCA within the past week, physicians reported that they prescribed the advertised drug in 39% of visits, but in 43% of encounters they took other actions (e.g., prescribed a different drug, suggested a lifestyle change), and in 18% of encounters, they took no action. The previously described survey of physicians in Colorado found that 24% reported that they had ever altered their prescribing practices due to a DTCA-prompted request (Parnes et al., 2009). The study did not evaluate whether the changes in prescribing were medically appropriate.

Two studies suggest that DTCA-prompted requests for prescriptions can have profound influence on prescriber behavior. Mintzes and colleagues (2003) conducted on-site surveys of patient and physician pairs in a clinic in the United States (U.S.; patient n = 683, physician n = 38) and a clinic in Canada (patient n = 748, physician n = 40). The design was advantageous in that the setting minimized potential influence of recall bias and the pairing of patient and physician responses allowed for a more nuanced evaluation of this topic. Although only 7% of U.S. patients made DTCA-prompted requests for prescription drugs, physicians fulfilled these requests in 78% of cases. After the clinical encounters, physicians in this study were asked to reflect on these requests and rate the likeliness (unlikely, possibly, very likely) of prescribing the drug for other similar patients. Of the DTCA-prompted prescriptions (those requests prompted by DTCA that resulted in one or more prescriptions), physicians rated 50% as “possible” or “unlikely” choices for other patients similar to those making the request, compared to 12% of prescriptions that were not based on DTCA requests (Mintzes et al., 2003). In a randomized trial by Kravitz and colleagues (2005), trained actors posing as patients with fictitious symptoms made requests to 152 primary care physicians for antidepressants for either major depressive disorder or adjustment disorder, the latter being a condition for which antidepressants are not clinically approved. In the major depressive disorder group, rates of prescribing were 53%, 76%, and 31% for actors making brand-specific, general, and no request, respectively. Rates of prescribing for adjustment disorder were 55%, 39%, and 10%, respectively. Thus, DTCA-prompted requests addressed underuse by appropriately diagnosing and prescribing for those with major depression, but also promoted overuse by providing inappropriate prescriptions for those with adjustment disorder. Follow-up focus groups with 22 of the 152 surveyed physicians pointed to a tendency to err toward overtreatment to build better rapport when faced with a potentially stigmatizing condition (Tentler et al., 2008).

Patient–prescriber relationship

Physicians report mixed attitudes about the benefits of DTCA on their relationships with patients (Online Supplement Appendix C). The previously described FDA survey found that 41% of physicians reported that DTCA exposure had some benefit on their relationship with patients, leading to better discussions or greater awareness of potential treatments (Aikin et al., 2004). Conversely, while 60% of surveyed members of the American Academy of Family Physicians agreed that DTCA encourages patients to take a more active role in their health care, 89% disagreed that these same ads enhance the prescriber–patient relationship (Lipsky & Taylor, 1997). A survey of primary care and psychiatric physicians showed that 46% felt that DTCA had neither a positive nor negative influence on their relationships with patients, whereas 39% reported a negative impact on their relationships. Adverse outcomes included lengthening clinic times to correct misperceptions or explain why a requested drug was inappropriate or an alternative drug was better (Bhanji et al., 2008). In the study by Parnes and colleagues (2009) of clinical encounters within a Colorado health research network, physicians reported that the overall impact of DTCA on their patient visit was positive in 24% of visits, neutral in 66%, and negative in 10%.

DISCUSSION

This review synthesized the research literature on patients’ and prescribers’ perceptions of the influences of DTCA of prescription drugs on the clinical encounter. We focus our discussion on key gaps in the literature and areas for future exploration.

Whereas the preponderance of the literature we identified studied exposure to DTCA more generally, fewer studies explored the influence of DTCA on specific disease conditions. Our review identified no studies on patient and provider perceptions of DTCA-related behaviors outside of mental illness or anxiety disorders, signaling a gap in the literature. Findings from studies in the context of mental health suggested that DTCA can influence requests for and prescribing of these medicines. Further, in one well-designed study, exposure to DTCA was associated with decreased adherence to mental health medications (noteworthy in this study was the inclusion of a comparison group of patients who reported not having been exposed to DTCA for these drugs). For these patients, it is likely that the information about the drug’s risks was more influential than the information about its benefits, leading them to alter their medication behaviors, although this mediational hypothesis was not tested.

Our review also suggests that the literature on DTCA and health-related behavior is dated; about three-quarters of the studies identified in our review were more than a decade old. Given the changing landscape of DTCA, where patients are increasingly exposed to online prescription drug promotion on pharmaceutical websites or through interactive social media (including drug company–sponsored Facebook pages, Twitter accounts, and YouTube channels, for example), further exploration within this new and rapidly changing era of online promotion is warranted.

Other limitations to the research we identified were that studies seldom included a meaningful comparison group (e.g., patients who were not exposed to or influenced by DTCA). Therefore, it is difficult to know if the frequency with which patients reported outcomes would have been higher or lower among those not exposed to DTCA. Second, studies often asked patients to recall past behaviors, which is prone to recall bias. Stronger research designs assessed patient and prescriber reactions to DTCA at the time of actual clinical encounters.. Assessments of diverse samples, including those with lower educational backgrounds or those who speak English as a second language, were rare; these groups warrant further study because they may be highly influenced to the information presented in DTCA. Finally, many of the conclusions drawn from this literature assume a somewhat simplistic model of behavior change, where exposure to DTCA is thought to influence thought, which in turn leads to behavior. Communication Theory suggests that a more complex interaction of factors is at play (Hornik & Yanovitzky, 2003). For example, exposure to DTCA may have a stronger influence for some population segments (e.g., those who actively seek drug information for a diagnosed condition) than others, or after repeated exposures through multiple channels, or in the presence of other social or institutional factors. A more nuanced understanding of how and for whom DTCA exerts its influence would aid the field moving forward.

Our review methodology had some limitations. Our search found that studies addressing this topic were not indexed in a consistent way; thus, our review may have missed some relevant studies. However, we mitigated this possibility through an extensive backward and forward hand-search process, as described in our methods. We did not conduct a formal quality assessment of the studies in our review, so we cannot evaluate the strength of this body of evidence. Finally, our review is limited by publication bias and thus may overstate the benefits or harms of DTCA exposure.

Our literature review echoes many of the conclusions made in previous studies about the reported benefits and harms of DTCA on health-related behaviors. Additional research is needed that assesses the influence on specific disease conditions (such as the influence of DTCA on cancer-related decision-making); uses strong observational designs (e.g., includes a nonexposed comparison group), considers a broad set of factors that could explain how exposure leads to behavior (mediational analyses); and considers the rapidly changing online presence of prescription drug promotion.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Food and Drug Administration under Contract HHSF223201510002B.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

For ease of reading we use the term “advertising” to encompass advertising and promotional labeling. Broad use of this term does not imply endorsement by FDA.

Studies in this table may fall into multiple categories within each section, therefore, each section may sum to greater than 100%.

REFERENCES

- Aikin KJ, Swasy JL, & Braman AC (2004). Patient and physician attitudes and behaviors associated with DTC promotion of prescription drugs–Summary of FDA survey research results. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ScienceResearch/ResearchAreas/DrugMarketingAdvertisingandCommunicationsResearch/ucm152860.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Allison-Ottey SD, Ruffin K, Allison K, & Ottey CC (2003). Assessing the impact of direct-to-consumer advertisements on the AA patient: A multisite survey of patients during the office visit. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95(2), 120–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison-Ottey SD, Ruffin K, & Allison KB (2002). “To do no harm” survey of NMA physicians regarding perceptions on DTC advertisements. Journal of the National Medical Association, 94(4), 194–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasi EA, Stafford RS, Kravitz RL, & Mansfield PR (2006). What are the public health effects of direct-to-consumer drug advertising? PLoS Medicine, 3(3), e145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Physicians. (2006). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Position paper. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians. [Google Scholar]

- Avorn J, Chen M, & Hartley R (1982). Scientific versus commercial sources of influence on the prescribing behavior of physicians. American Journal of Medicine, 73(1), 4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, Kravitz RL, & Wilkes MS (1999). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising and the public. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(11), 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RA, Taylor LD, & Kravitz RL (2010). Do antidepressant advertisements educate consumers and promote communication between patients with depression and their physicians? Patient Education and Counseling, 81(2), 245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanji NH, Baron DA, Lacy BW, Gross LS, Goin MK, Sumner CR, … Slaby AE (2008). Direct-to-consumer marketing: An attitude survey of psychiatric physicians. Primary Psychiatry, 15(11), 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M (2001). Understanding the effects of direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Menlo Park, CA: [Google Scholar]

- Brownfield ED, Bernhardt JM, Phan JL, Williams MV, & Parker RM (2004). Direct-to-consumer drug advertisements on network television: An exploration of quantity, frequency, and placement. Journal of Health Communication, 9(6), 491–497. doi: 10.1080/10810730490523115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorme DE, Huh J, & Reid LN (2006). Age differences in how consumers behave following exposure to DTC advertising. Health Communication, 20(3), 255–265. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc2003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dens N, Eagle LC, & De Pelsmacker P (2008). Attitudes and self-reported behavior of patients, doctors, and pharmacists in New Zealand and Belgium toward direct-to-consumer advertising of medication. Health Communication, 23(1), 45–61. doi: 10.1080/10410230701805190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A, Menon A, Perri M III, & Zinkhan G (2004). Direct-to-consumer advertising and its utility in health care decision making: A consumer perspective. Journal of Health Communication, 9(6), 499–513. doi: 10.1080/10810730490523197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieringer NJ, Kukkamma L, Somes GW, & Shorr RI (2011). Self-reported responsiveness to direct-to-consumer drug advertising and medication use: Results of a national survey. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), 232. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckwitz N, & Yuan Y (2002). Doctors & DTC. Retrieved from http://www.pharmexec.com/print/243373?page=full

- Fortuna RJ, Ross-Degnan D, Finkelstein J, Zhang F, Campion FX, & Simon SR (2008). Clinician attitudes towards prescribing and implications for interventions in a multi-specialty group practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14(6), 969–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellad ZF, & Lyles KW (2007). Direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals. American Journal of Medicine, 120(6), 475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Wilson P, & Watt I (2005). Benefits and harms of direct to consumer advertising: A systematic review. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 14(4), 246–250. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CE, Mojtabai R, Cullen BA, Spivak A, Mitchell M, & Spivak S (2017). Exposure to direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising and medication nonadherence among patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 68(12), 1299–1302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzenstein M, Misra S, & Posavac SS (2004). How consumers’ attitudes toward direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs influence ad effectiveness, and consumer and physician behavior. Marketing Letters, 15(4), 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek J, & Maubach N (2007). Consumers’ knowledge, perceptions, and responsiveness to direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription medicines. New Zealand Medical Journal, 120(1249), U2425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R, & Yanovitzky I (2003). Using theory to design evaluations of communication campaigns: The case of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign. Communication Theory, 13(2), 204–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh J, DeLorme DE, & Reid LN (2005). Factors affecting trust in on-line prescription drug information and impact of trust on behavior following exposure to DTC advertising. Journal of Health Communication, 10(8), 711–731. doi: 10.1080/10810730500326716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, McFarlane EG, Southwell BG, Boudewyns V, Chowdhury D, Cullen K, … Wohlgenant K (2013). Healthcare professional survey of prescription drug promotion: Methods report. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International. [Google Scholar]

- Khanfar NM, Polen HH, & Clauson KA (2009). Influence on consumer behavior: The impact of direct-to-consumer advertising on medication requests for gastroesophageal reflux disease and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Health Communication, 14(5), 451–460. doi: 10.1080/10810730903032978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, Franz CE, Azari R, Wilkes MS, … Franks P (2005). Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(16), 1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krezmien E, Wanzer MB, Servoss T, & LaBelle S (2011). The role of direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertisements and individual differences in getting people to talk to physicians. Journal of Health Communication, 16(8), 831–848. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.561909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Salmon CT, & Paek H-J (2007). The effects of information sources on consumer reactions to direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription drug advertising: A consumer socialization approach. Journal of Advertising, 36(1), 107–119. doi: 10.2753/joa0091-3367360108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, & Begley CE (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in response to direct-to-consumer advertising. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 67(14), 1185–1190. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky MS, & Taylor CA (1997). The opinions and experiences of family physicians regarding direct-to-consumer advertising. Journal of Family Practice, 45(6), 495–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey K (2017). Drugmakers again boost DTC spending, to $5.6 billion in 2016. Retrieved from http://www.mmm-online.com/commercial/drugmakers-again-boost-dtc-spending-to-56-billion-in-2016/article/642028/

- Mintzes B (2012). Advertising of prescription-only medicines to the public: Does evidence of benefit counterbalance harm? Annual Review of Public Health, 33, 259–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, Bassett K, Lexchin J, Kazanjian A, … Marion SA (2003). How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? A survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 169(5), 405–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E, Lo B, Pollack L, Donelan K, & Lee K (2004). Direct-to-consumer advertising: Public perceptions of its effects on health behaviors, health care, and the doctor-patient relationship. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 17(1), 6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnes B, Smith PC, Gilroy C, Quintela J, Emsermann CB, Dickinson LM, & Westfall JM (2009). Lack of impact of direct-to-consumer advertising on the physician-patient encounter in primary care: A SNOCAP report. Annals of Family Medicine, 7(1), 41–46. doi: 10.1370/afm.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul DP, Handlin A, & Stanton AD (2002). Primary care physicians’ attitudes toward direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs: Still crazy after all these years. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(7), 564–574. doi: 10.1108/07363760210451393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AR, Hohmann KB, Rifkin JI, Topp D, Gilroy CM, Pickard JA, & Anderson RJ (2004). Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: Physician and public opinion and potential effects on the physician-patient relationship. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(4), 427–432. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby JV, Beal AC, & Frank L (2012). The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307(15), 1583–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, & Smith D (2005). Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising: A study of consumer attitudes and behavioral intentions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(7), 369–378. doi: 10.1108/07363760510631101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spake DF, & Joseph M (2007). Consumer opinion and effectiveness of direct-to-consumer advertising. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(5), 283–292. doi: 10.1108/07363760710773102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spake DF, Joseph M, & Megehee CM (2014). Do perceptions of direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising vary based on urban versus rural living? Health Marketing Quarterly, 31(1), 31–45. doi: 10.1080/07359683.2013.847344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumpradit N, Fors SW, & McCormick L (2002). Consumers’ attitudes and behavior toward prescription drug advertising. American Journal of Health Behavior, 26(1), 68–75. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tentler A, Silberman J, Paterniti DA, Kravitz RL, & Epstein RM (2008). Factors affecting physicians’ responses to patients’ requests for antidepressants: Focus group study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(1), 51–57. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0441-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Nielsen Company. (2016). The Nielsen total audience report: Q1 2016. The Nielsen Total Audience Series. Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/corporate/us/en/reports-downloads/2016-reports/total-audience-report-q1-2016.pdf

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2015). Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) research. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm090276.htm

- Viale PH, & Sanchez Yamamoto D (2004). The attitudes and beliefs of oncology nurse practitioners regarding direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription medications. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(4), 777–783. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.777-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman JS, Blumenthal D, Silk AJ, Newman M, Zapert K, Leitman R, & Feibelmann S (2004). Physicians report on patient encounters involving direct-to-consumer advertising. Health Affairs, Suppl Web Exclusives, W4–219–233. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman JS, Blumenthal D, Silk AJ, Zapert K, Newman M, & Leitman R (2003). Consumers’ reports on the health effects of direct-to-consumer drug advertising. Health Affairs, Suppl Web Exclusives, W3–82–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.