ABSTRACT

To estimate the incidence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), a global collection of 81,781 surveillance isolates of Enterobacterales collected from patients in 39 countries in five geographic regions from 2012 to 2017 was studied. Overall, 3.3% of isolates were meropenem-nonsusceptible (MIC ≥2 μg/ml), ranging from 1.4% (North America) to 5.3% (Latin America) of isolates by region. Klebsiella pneumoniae accounted for the largest number of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates (76.7%). The majority of meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales carried KPC-type carbapenemases (47.4%), metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs; 20.6%) or OXA-48-like β-lactamases (19.0%). Forty-three carbapenemase sequence variants (8 KPC-type, 4 GES-type, 7 OXA-48-like, 5 NDM-type, 7 IMP-type, and 12 VIM-type) were detected, with KPC-2, KPC-3, OXA-48, NDM-1, IMP-4, and VIM-1 identified as the most common variants of each carbapenemase type. The resistance mechanisms responsible for meropenem-nonsusceptibility varied by region. A total of 67.3% of all carbapenemase-positive isolates identified carried at least one additional plasmid-mediated or intrinsic chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum β-lactamase, AmpC β-lactamase, or carbapenemase. The overall percentage of meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales increased from 2.7% in 2012 to 2014 to 3.8% in 2015 to 2017. This increase could be attributed to the increasing proportion of carbapenemase-positive isolates that was observed, most notably among isolates carrying NDM-type MBLs in Asia/South Pacific, Europe, and Latin America; OXA-48-like carbapenemases in Europe, Middle East/Africa, and Asia/South Pacific; VIM-type MBLs in Europe; and KPC-type carbapenemases in Latin America. Ongoing CRE surveillance combined with a global antimicrobial stewardship strategy, sensitive clinical laboratory detection methods, and adherence to infection control practices will be needed to interrupt the spread of CRE.

KEYWORDS: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, surveillance, Enterobacterales, carbapenem resistant

INTRODUCTION

Carbapenems are a class of broad-spectrum β-lactam antimicrobial agents often used to treat hospitalized patients who have failed initial therapy or those with severe infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. Carbapenems are highly active against Enterobacterales that possess Ambler class C cephalosporinases and/or class A β-lactamases, including extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (1). The appearance and global dissemination of successful clones of ESBL-producing Enterobacterales over the last 3 decades resulted in an increase in the use of carbapenems to treat infections caused by these organisms. Subsequently, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) emerged, predominantly, but not exclusively, among Klebsiella pneumoniae (2–8).

Carbapenemases are β-lactamases capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems and most other β-lactams, resulting in carbapenem and multidrug resistance. Ambler class A (KPC and GES) and class D (OXA-48-like) carbapenemases possess a serine-based active site, while class B metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs; NDM, IMP, and VIM) have one or two zinc atoms in their active site (8, 9). Each carbapenemase type shows different substrate specificities, e.g., KPC hydrolyzes a broad spectrum of substrates, including penicillins, oxyimino-cephalosporins, older β-lactamase inhibitors (clavulanic acid, sulbactam, tazobactam), aztreonam, and carbapenems, while MBLs have a spectrum of hydrolysis similar to that of KPC but spare aztreonam, and OXA-48-like carbapenemases spare both cephalosporins and aztreonam but hydrolyze penicillins and weakly hydrolyze carbapenems (8, 9). CRE often cocarry multiple β-lactamases and determinants conferring resistance to antimicrobials from other drug classes, such as aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones, resulting in an MDR phenotype (10).

Whereas carbapenemase production is the most frequent mechanism of carbapenem resistance identified in meropenem-nonsusceptible CRE, other mechanisms of resistance may be present in some clinical isolates, including hyperproduction of AmpC β-lactamases or ESBLs, combined with impaired outer membrane permeability due to porin mutations, upregulated efflux, and/or alterations in penicillin-binding proteins (8, 11–14). Resistance arising by non-carbapenemase-mediated mechanisms is indistinguishable phenotypically from carbapenemase-based resistance.

The primary objective of the current report was to describe the molecular epidemiology of β-lactamase resistance determinants identified in meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales collected as part of a global surveillance program from 2012 to 2017.

RESULTS

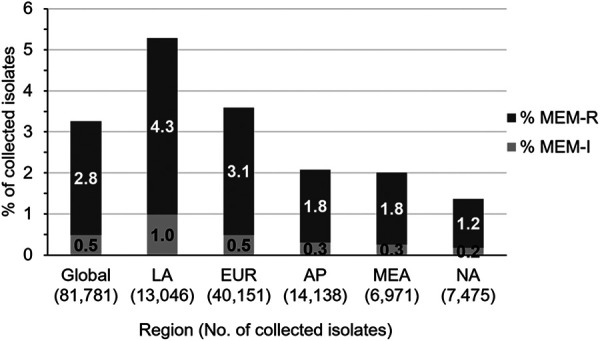

A total of 81,781 clinically significant Enterobacterales isolates that were considered probable causative agents of infection were collected from patients in 39 countries by medical laboratories participating in a global surveillance study from 2012 to 2017. Of these isolates, 2,666 (3.3%) tested as meropenem-nonsusceptible (MIC ≥2 μg/ml). The 2,666 isolates were from various infection sources, including lower respiratory tract (n = 778), urinary tract (n = 631), skin and soft tissue (n = 581), intra-abdominal (n = 408), bloodstream (n = 266), and other sites of infection (n = 2) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The percentage of Enterobacterales isolates from each geographic region that tested as meropenem-nonsusceptible ranged from 1.4% (North America) to 5.3% (Latin America) (Fig. 1). The largest number of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates were comprised of K. pneumoniae (n = 2,046; 76.7%), followed by Enterobacter cloacae (n = 177; 6.6%) and Escherichia coli (n = 136; 5.1%), with the remaining ∼12% of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates composed of 101 isolates of Klebsiella spp., 79 isolates of Citrobacter spp., 70 isolates of Proteeae, 31 isolates of Serratia marcescens, 18 isolates of Enterobacter spp., and 8 isolates of Raoultella spp. (see Fig. S2).

FIG 1.

Distribution of meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales collected from 2012 to 2017. MEM-I, meropenem-intermediate, MIC of 2 μg/ml; MEM-R, meropenem-resistant, MIC of ≥4 μg/ml. Global, all surveyed regions; LA, Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela); EUR, Europe (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom); AP, Asia/South Pacific (Australia, China, Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand); MEA, Middle East/Africa (Israel, Kenya, Kuwait, Nigeria, and South Africa); NA, North America (the United States). Isolates obtained from patients in North America were collected from 2012 to 2016 only.

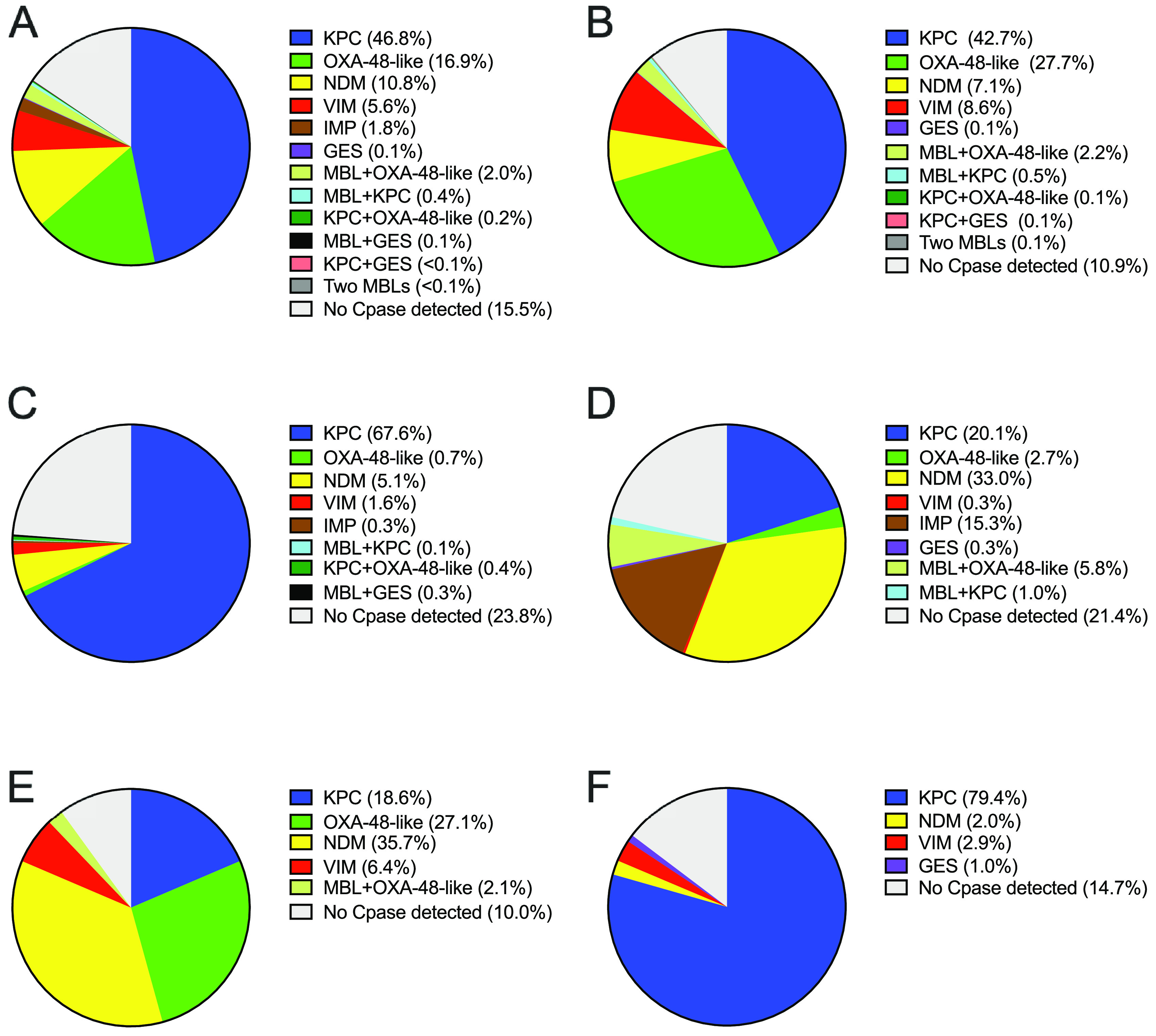

The majority (47.4%, n = 1,263) of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates collected globally carried KPC-type carbapenemases, whereas comparable percentages of isolates carried MBLs (20.6%, n = 548) or OXA-48-like β-lactamases (19.0%, n = 506), and few isolates carried GES-type carbapenemases (0.2%, n = 6) (Fig. 2A). MBL types were not equally common, with 61% of MBL-positive isolates carrying NDM-type, 30% carrying VIM-type, and 9% carrying IMP-type β-lactamases. No gene encoding a carbapenemase was detected in 15.5% (n = 413) of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates; of these, 91.5% carried ESBL- and/or AmpC β-lactamase-coding genes detected by PCR or the intrinsic, chromosomally encoded β-lactamases common to Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., Providencia spp., Serratia spp., and K. oxytoca and were assumed also to display reduced expression or loss of outer membrane porin proteins and/or upregulated efflux systems, which can lead to carbapenem resistance (Fig. 2A) (11–13). The remaining isolates were assumed to carry β-lactamases not included in the testing algorithm (e.g., SME, IMI/NMC-A [8]) and/or other resistance mechanisms, such as those described above; alternatively, these isolates may have carried β-lactamase genes that were not amplified with the primers used for detection.

FIG 2.

Distribution of carbapenem resistance mechanisms identified in meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales isolates. (A) Meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates collected in all surveyed regions (n = 2,666). (B) Isolates collected in Europe (n = 1,441). (C) Isolates collected in Latin America (n = 689). (D) Isolates collected in Asia/South Pacific (n = 294). (E) Isolates collected in the Middle East/Africa (n = 140). (F) Isolates collected in North America (n = 102,2012 to 2016 only). No Cpase detected, no gene encoding a carbapenemase was detected by PCR. MBL + OXA-48-like (n = 52) included NDM + OXA-48-like (Europe, n = 26; Asia/South Pacific, n = 17; Middle East/Africa, n = 1) and VIM + OXA-48-like (Europe, n = 6; Middle East/Africa, n = 2). MBL + KPC (n = 11) included VIM + KPC (Europe, n = 7), NDM + KPC (Latin America, n = 1; Asia/South Pacific, n = 1) and IMP + KPC (Asia/South Pacific, n = 2). MBL + GES was composed of NDM + GES carbapenemase (Latin America, n = 2). Two MBLs were composed of VIM + NDM (Europe, n = 1).

The distribution of resistance mechanisms observed among meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates varied by region (Fig. 2B to F and Table 1). Among isolates collected in Europe, the percentages of different carbapenemase types were similar to those observed for the global collection of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates, except that a larger proportion of isolates (30%) carried OXA-48-like β-lactamases, isolates carrying NDM-type and VIM-type MBLs were identified in comparable proportions (7 to 9%), and no isolates carrying IMP-type MBLs were identified (Fig. 2B). In Latin America and North America, KPC-positive isolates predominated, comprising 68 and 79% of the isolates collected, respectively. MBLs were found in 5 to 7% of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates from these two regions and OXA-48-like β-lactamases were found, in low numbers, only among isolates from Latin America (Fig. 2C and F). In contrast, MBL-positive isolates comprised the majority of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates collected in Asia/South Pacific and the Middle East/Africa regions (55 and 44%, respectively). In these two regions, approximately one-third of the meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates collected carried NDM-type MBLs. IMP-positive isolates were only found in Asia/South Pacific, except for two isolates that were detected in Latin America. Similar proportions of KPC-positive isolates (19 to 21%) were found in Asia/South Pacific and the Middle East/Africa region, whereas the proportion of isolates carrying OXA-48-like (29%) and VIM-type (8%) enzymes was greater among isolates collected in the Middle East/Africa region and approached that observed for Europe (Fig. 2D and E).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of carbapenemase variants among 2,253 meropenem-nonsusceptible, carbapenemase-positive Enterobacterales isolates collected from 2012 to 2017

| Region (no. of CPE/no. of collected isolates)a | Organism | Carbapenemase type/variant (no. of isolates) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPC | GES | OXA-48-like | IMP | NDM | VIM | ||

| Europe (1,284/40,151) | C. amalonaticus | KPC-2 (1) | OXA-48 (1) | ||||

| C. farmeri | VIM-1 (2) | ||||||

| C. freundii | KPC-2 (2) | OXA-48 (7) | VIM-1 (11) | ||||

| KPC-3 (2) | VIM-4 (2) | ||||||

| VIM-31 (5) | |||||||

| E. asburiae | VIM-1 (1) | ||||||

| E. cloacae | KPC-2 (2) | GES-6 (1) | OXA-48 (12) | NDM-1 (12) | VIM-1 (42) | ||

| KPC-3 (1) | OXA-162 (1) | VIM-2 (1) | |||||

| VIM-4 (2) | |||||||

| VIM-31 (1) | |||||||

| E. coli | KPC-2 (3) | OXA-48 (8) | NDM-1 (5) | VIM-1 (2) | |||

| KPC-3 (7) | OXA-181 (7) | NDM-5 (5) | |||||

| OXA-232 (1) | |||||||

| OXA-244 (1) | |||||||

| K. aerogenes | KPC-2 (1) | OXA-48 (4) | NDM-1 (2) | ||||

| K. oxytoca | KPC-2 (3) | OXA-48 (6) | NDM-1 (2) | VIM-1 (3) | |||

| KPC-3 (3) | VIM-44 (1) | ||||||

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 (338) | GES-6 (1) | OXA-48 (347) | NDM-1 (88) | VIM-1 (24) | ||

| KPC-3 (257) | OXA-162 (3) | NDM-16 (2) | VIM-12 (1) | ||||

| KPC-9 (2) | OXA-163 (2) | VIM-26 (15) | |||||

| KPC-type (2) | OXA-181 (1) | VIM-42 (1) | |||||

| OXA-232 (6) | |||||||

| OXA-244 (12) | |||||||

| P. mirabilis | OXA-48 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | VIM-1 (5) | ||||

| P. rettgeri | OXA-48 (3) | NDM-1 (11) | VIM-1 (1) | ||||

| P. stuartii | VIM-1 (14) | ||||||

| R. ornithinolytica | OXA-48 (2) | VIM-1 (1) | |||||

| R. planticola | OXA-48 (3) | ||||||

| S. marcescens | OXA-48 (4) | NDM-1 (2) | VIM-1 (1) | ||||

| VIM-4 (1) | |||||||

| VIM-5 (1) | |||||||

| Latin America (525/13,046) | C. freundii | KPC-2 (7) | VIM-23 (1) | ||||

| C. koseri | KPC-2 (3) | ||||||

| E. asburiae | KPC-2 (2) | ||||||

| E. cloacae | KPC-2 (19) | NDM-1 (6) | VIM-1 (2) | ||||

| VIM-23 (3) | |||||||

| E. coli | KPC-2 (14) | GES-2 (1) | OXA-232 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | VIM-23 (2) | ||

| K. aerogenes | KPC-2 (6) | ||||||

| K. oxytoca | KPC-2 (10) | GES-2 (1) | IMP-8 (2) | NDM-1 (1) | |||

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 (346) | OXA-163 (4) | NDM-1 (24) | VIM-23 (2) | |||

| KPC-3 (49) | OXA-232 (1) | VIM-24 (1) | |||||

| KPC-30 (1) | OXA-370 (1) | ||||||

| KPC-type (1) | |||||||

| K. variicola | KPC-2 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| P. rettgeri | NDM-1 (5) | ||||||

| R. ornithinolytica | KPC-3 (1) | OXA-181 (1) | |||||

| S. marcescens | KPC-2 (10) | ||||||

| Asia/Pacific (231/14,138) | C. farmeri | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| C. freundii | IMP-4 (7) | NDM-1 (5) | |||||

| IMP-8 (2) | NDM-7 (4) | ||||||

| C. koseri | KPC-2 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| E. asburiae | IMP-8 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| IMP-14 (1) | NDM-7 (2) | ||||||

| E. cloacae | KPC-2 (1) | IMP-1 (1) | NDM-1 (17) | ||||

| IMP-4 (3) | NDM-7 (4) | ||||||

| IMP-8 (1) | |||||||

| IMP-14 (2) | |||||||

| IMP-26 (1) | |||||||

| E. kobei | KPC-2 (1) | ||||||

| E. coli | KPC-2 (5) | OXA-181 (3) | IMP-59 (1) | NDM-1 (3) | |||

| NDM-5 (9) | |||||||

| NDM-7 (3) | |||||||

| K. aerogenes | KPC-2 (3) | IMP-8 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | ||||

| K. oxytoca | KPC-2 (3) | IMP-4 (5) | NDM-1 (1) | ||||

| NDM-7 (1) | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 (45) | GES-5 (1) | OXA-48 (5) | IMP-1 (2) | NDM-1 (45) | ||

| KPC-12 (1) | OXA-181 (7) | IMP-4 (10) | NDM-4 (1) | ||||

| KPC-17 (1) | OXA-232 (10) | IMP-26 (5) | NDM-5 (1) | ||||

| NDM-7 (12) | |||||||

| P. mirabilis | IMP-26 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| P. rettgeri | NDM-1 (2) | ||||||

| P. stuartii | VIM-1 (1) | ||||||

| S. marcescens | KPC-2 (1) | IMP-4 (1) | |||||

| IMP-8 (1) | |||||||

| IMP-47 (1) | |||||||

| Middle East/Africa (126/6,971) | C. freundii | KPC-2 (1) | OXA-181 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | |||

| E. asburiae | OXA-48 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| E. cloacae | KPC-2 (1) | OXA-48 (3) | NDM-1 (4) | VIM-4 (4) | |||

| KPC-3 (1) | OXA-181 (1) | ||||||

| E. kobei | OXA-48 (2) | ||||||

| E. coli | KPC-2 (2) | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| KPC-3 (1) | NDM-5 (2) | ||||||

| K. aerogenes | KPC-2 (1) | NDM-1 (1) | |||||

| K. oxytoca | NDM-1 (1) | VIM-1 (2) | |||||

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 (6) | OXA-48 (5) | NDM-1 (27) | VIM-1 (1) | |||

| KPC-3 (13) | OXA-181 (16) | NDM-5 (2) | |||||

| OXA-232 (12) | NDM-7 (5) | ||||||

| P. mirabilis | VIM-5 (4) | ||||||

| P. rettgeri | NDM-1 (5) | ||||||

| P. stuartii | NDM-1 (1) | ||||||

| North America (87/7,475) | C. farmeri | KPC-3 (1) | |||||

| C. freundii | KPC-2 (3) | VIM-1 (1) | |||||

| VIM-32 (1) | |||||||

| E. asburiae | KPC-2 (2) | ||||||

| E. cloacae | KPC-2 (1) | VIM-1 (1) | |||||

| E. coli | KPC-2 (2) | ||||||

| KPC-3 (3) | |||||||

| KPC-18 (2) | |||||||

| K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 (17) | GES-20 (1) | NDM-1 (2) | ||||

| KPC-3 (49) | |||||||

| KPC-29 (1) | |||||||

Meropenem-nonsusceptible carbapenemase-positive isolates from Europe were collected in Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Isolates from Latin America were collected in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela. Isolates from Asia/South Pacific were collected in Australia, China, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand. Isolates from Middle East/Africa were collected in Israel, Kenya, Kuwait, Nigeria, and South Africa. Isolates from North America were collected in the United States. Isolates carrying multiple carbapenemases were counted for each individual carbapenemase type.

Forty-three carbapenemase sequence variants (8 KPC-type, 4 GES-type, 7 OXA-48-like, 5 NDM-type, 7 IMP-type, and 12 VIM-type variants) were identified among 2,253 meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates carrying one or more carbapenemases (Table 1; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). KPC-2 (864 of 1,263 isolates, 68.4%), KPC-3 (388 of 1,263 isolates, 30.7%), OXA-48 (414 of 506 isolates, 81.8%), NDM-1 (283 of 336 isolates, 84.2%), IMP-4 (26 of 49 isolates, 53.1%), and VIM-1 (115 of 164 isolates, 70.1%) were the most commonly identified variants of these carbapenemase types. As shown in Table 1, KPC-2 made up the majority of KPC-type carbapenemases identified among isolates collected in Europe (350 of 624, 56.1%), Latin America (418 of 470, 88.9%), and Asia/South Pacific (60 of 62, 96.8%), whereas KPC-3 was more common among isolates collected in Middle East/Africa (15 of 26, 57.7%) and North America (53 of 81, 65.4%). OXA-48 was the major OXA-type found among isolates from Europe (398 of 432, 92.1%), but OXA-181 and OXA-232 were more prevalent in the Middle East/Africa (30 of 41, 73.2%) and Asia/South Pacific (20 of 25, 80.0%). NDM-1 was the predominant NDM-type detected among isolates collected in all regions, but the numbers of isolates carrying NDM-5 and NDM-7 were notably increased in Middle East/Africa (9 of 51, 17.6%) and Asia/South Pacific (36 of 115, 31.3%). IMP-8 was the only IMP-type detected among meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales collected outside the Asia/South Pacific region. Similarly, few VIM-positive isolates were collected in regions other than Europe, and the majority of these carried VIM-1, although isolates carrying VIM-23 were notable in Latin America (8 of 11, 72.7%) (Table 1). KPC-type carbapenemases were carried most frequently by K. pneumoniae in all regions surveyed, ranging from 73.1% (19 of 26) of KPC-positive isolates collected in Middle East/Africa to 96.0% (599 of 624) of isolates from Europe; similarly, the majority of OXA-48-like β-lactamases were also found among K. pneumoniae (>80% of OXA-48-like positive isolates collected in Europe, Asia/South Pacific, and Middle East/Africa). Although a large proportion of the MBLs identified globally were also carried by K. pneumoniae (271 of 548, 49.5%), the incidence of other species or species groups was markedly enriched among MBL-positive isolates, including E. cloacae (n = 107, 19.5%), Citrobacter freundii (n = 40, 7.3%), E. coli (n = 34, 6.2%) and the Proteeae (n = 51, 9.3%) (Table 1).

A total of 67.3% (1,516 of 2,253) of all carbapenemase-positive isolates identified globally cocarried at least one additional plasmid-mediated or intrinsic chromosomally encoded ESBL, AmpC β-lactamase or carbapenemase, including 49.2% (622 of 1,263) of KPC-positive isolates, 83.3% (5 of 6) of GES-positive isolates, 90.9% (460 of 506) of OXA-48-like-positive isolates, and 91.1% (499 of 548) of MBL-positive isolates (Table 2). Seventy-one isolates cocarrying two carbapenemases were collected in the Europe (n = 42), Asia/South Pacific (n = 20), Latin America (n = 6), and Middle East/Africa (n = 3) regions (Table 2 and Fig. 2B to E). These isolates were composed of 54 K. pneumoniae, six C. freundii, four E. cloacae, three E. coli, three K. oxytoca, and one Providencia rettgeri cocarrying NDM-type and OXA-48-like (n = 44), VIM-type and OXA-48-like (n = 8), VIM-type and KPC-type (n = 7), KPC-type and OXA-48-like (n = 4), KPC-type and NDM- or IMP-type (n = 2 of each), GES-type and NDM- or KPC-type (n = 2 and n = 1, respectively), and VIM-type and NDM-type (n = 1) carbapenemases. A total of 87.3% (62 of 71) of these isolates also harbored ESBLs or AmpC β-lactamases (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cocarriage of carbapenemases and other β-lactamases in 2,253 meropenem-nonsusceptible carbapenemase-positive Enterobacterales collected from 2012 to 2017

| Region | β-Lactamase typesa (no. of isolates) | Organismb | No. of isolates | Molecular variant(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | GES carbapenemase + ESBL + AmpC + OSBL (1) | E. cloacae* | 1 | GES-6, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL |

| KPC ± OSBL and/or spectrum undefined (346) | E. coli | 1 | KPC-2 | |

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 6 | KPC-3, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 3 | KPC-2 | ||

| 19 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 116 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 3 | KPC-3 | |||

| 30 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-3, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 162 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, SHV-26, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, SHV-36, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (239) | E. coli | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. oxytoca† | 1 | KPC-2 | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3 | |||

| 2 | KPC-3, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 26 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-27, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 37 | KPC-2, SHV-12 | |||

| 81 | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, VEB-1, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 21 | KPC-2, VEB-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, VEB-1, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-3, CTX-M-14, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15 | |||

| 2 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 47 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, SHV-28, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, SHV-168, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-3, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-9, VEB-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-TYPE, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + AmpC ± OSBL (25) | C. amalonaticus* | 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |

| C. freundii* | 2 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | ||

| E. cloacae* | 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | KPC-3 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, ACT-TYPE, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 8 | KPC-2, CMY-4, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 10 | KPC-2, CMY-4, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CMY-4, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (5) | C. freundii* | 1 | KPC-3, SHV-12 | |

| E. cloacae* | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | ||

| K. aerogenes* | 1 | KPC-2, VEB-1, TEM-OSBL | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, MOX-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| KPC + GES carbapenemase + OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, GES-6, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| KPC + OXA-48-like + OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, OXA-163, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| OXA-48-like ± OSBL (38) | E. coli | 1 | OXA-48, TEM-OSBL | |

| K. pneumoniae | 18 | OXA-48, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 11 | OXA-48, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | OXA-232, SHV-OSBL | |||

| P. mirabilis | 1 | OXA-48 | ||

| R. ornithinolytica | 2 | OXA-48 | ||

| R. planticola | 3 | OXA-48 | ||

| OXA-48-like + ESBL ± OSBL (322) | E. coli | 6 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-24, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-244, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. oxytoca† | 2 | OXA-48 | ||

| 3 | OXA-48, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-27 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | OXA-48, CTX-M-3, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 6 | OXA-48, CTX-M-3, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-9-type, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 3 | OXA-48, CTX-M-9-type, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-14 | |||

| 3 | OXA-48, CTX-M-14, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 17 | OXA-48, CTX-M-14, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | OXA-48, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-27, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15 | |||

| 75 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 166 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | OXA-48, CTX-M-27, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | OXA-48, CTX-M-28, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-28, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-55 | |||

| 2 | OXA-48, CTX-M-55, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, SHV-ESBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, SHV-ESBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 3 | OXA-162, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-163, CTX-M-3, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-232, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 2 | OXA-244, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 10 | OXA-244, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| OXA-48-like + AmpC ± OSBL (17) | C. amalonaticus* | 1 | OXA-48 | |

| C. freundii* | 1 | OXA-48 | ||

| 1 | OXA-48, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. cloacae* | 3 | OXA-48 | ||

| 1 | OXA-162, ACC-4, DHA-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. coli | 1 | OXA-181, CMY-42 | ||

| K. aerogenes* | 3 | OXA-48 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | OXA-48, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL | ||

| P. rettgeri* | 1 | OXA-48, TEM-OSBL | ||

| S. marcescens* | 3 | OXA-48 | ||

| OXA-48-like + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (22) | E. cloacae* | 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-9-type, SHV-12 | |

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 4 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-48, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. coli | 6 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15, CMY-42 | ||

| K. aerogenes* | 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, CMY-6, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 3 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| P. rettgeri* | 2 | OXA-48, PER-1, TEM-OSBL | ||

| S. marcescens* | 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-22, SHV-OSBL | ||

| MBL ± OSBL (25) | E. coli | 2 | NDM-1, TEM-OSBL | |

| 2 | NDM-5 | |||

| 1 | VIM-1 | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, SHV-OSBL | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 5 | NDM-1, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 1 | VIM-1 | |||

| 12 | VIM-1, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-12, SHV-OSBL | |||

| MBL + ESBL ± OSBL (74) | E. coli | 1 | NDM-5, CTX-M-15 | |

| K. oxytoca† | 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-3, SHV-12 | ||

| 1 | VIM-1, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | VIM-44, SHV-12 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 25 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 21 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-16, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-16, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-ESBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | VIM-1, SHV-5 | |||

| 3 | VIM-1, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, SHV-ESBL | |||

| 12 | VIM-26, SHV-5 | |||

| 1 | VIM-26, SHV-ESBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-42, SHV-12 | |||

| P. mirabilis | 1 | VIM-1, VEB-1, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | ||

| MBL + AmpC ± OSBL (56) | C. freundii* | 1 | VIM-1 | |

| 1 | VIM-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, FOX-7, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-4, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. asburiae* | 1 | VIM-1 | ||

| E. cloacae* | 2 | NDM-1 | ||

| 11 | VIM-1 | |||

| 22 | VIM-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-2 | |||

| 1 | VIM-4 | |||

| E. coli | 1 | NDM-1, CMY-6, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-5, CMY-42 | |||

| K. aerogenes* | 2 | NDM-1, CMY-4 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | NDM-1, CMY-6, SHV-OSBL | ||

| P. mirabilis | 4 | VIM-1, CMY-16, TEM-OSBL | ||

| P. rettgeri* | 1 | NDM-1, VIM-1 | ||

| R. ornithinolytica | 1 | VIM-1, CMY-13 | ||

| S. marcescens* | 1 | VIM-4 | ||

| 1 | VIM-5 | |||

| MBL + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (73) | C. farmeri* | 2 | VIM-1, SHV-12 | |

| C. freundii* | 7 | VIM-1, SHV-12 | ||

| 1 | VIM-4, SHV-12 | |||

| E. cloacae* | 4 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15 | ||

| 4 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-3, SHV-12, DHA-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-9-type | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-9-type, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-14, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, SHV-12 | |||

| 3 | VIM-1, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-4, CTX-M-9, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. coli | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, CTX-M-27, CMY-6, DHA-1, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-27, CMY-2 | |||

| K. oxytoca† | 1 | NDM-1, ACC-1, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, CMY-4 | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, ACC-1 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, CMY-4, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, CMY-6, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 4 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, CMY-6, DHA-type, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 2 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, DHA-type, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-5, CMY-6, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-5, CMY-6, DHA-type | |||

| P. mirabilis | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, DHA-type, TEM-OSBL | ||

| P. rettgeri* | 10 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | ||

| P. stuartii* | 1 | VIM-1, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | VIM-1, VEB-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 12 | VIM-1, VEB-1, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | |||

| S. marcescens* | 2 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | VIM-1, SHV-12 | |||

| MBL + KPC (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | VIM-1, KPC-2 | |

| MBL + KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (2) | K. pneumoniae | 2 | VIM-26, KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |

| MBL + KPC + AmpC + OSBL (2) | C. freundii* | 1 | VIM-1, KPC-3, SHV-OSBL | |

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | VIM-1, KPC-2, MOX-1, SHV-OSBL | ||

| MBL + KPC + ESBL + AmpC + OSBL (2) | K. pneumoniae | 2 | VIM-1, KPC-2, SHV-12, CMY-13, TEM-OSBL | |

| MBL + OXA-48-like + OSBL (4) | K. pneumoniae | 3 | NDM-1, OXA-48, SHV-OSBL | |

| 1 | NDM-1, OXA-232, SHV-OSBL | |||

| MBL + OXA-48-like + ESBL ± OSBL (17) | K. pneumoniae | 3 | NDM-1, OXA-48, CTX-M-15 | |

| 8 | NDM-1, OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 4 | NDM-1, OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | NDM-1, OXA-232, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL + OXA-48-like + AmpC ± OSBL (8) | C. freundii* | 5 | VIM-31, OXA-48, TEM-OSBL | |

| E. cloacae* | 1 | NDM-1, OXA-48 | ||

| 1 | VIM-31, OXA-48 | |||

| E. coli | 1 | NDM-5, OXA-232, CMY-42, TEM-OSBL | ||

| MBL + OXA-48-like + ESBL + AmpC + OSBL (3) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-1, OXA-48, CTX-M-15, CMY-6, SHV-OSBL | |

| 1 | NDM-1, OXA-48, CTX-M-15, DHA-type, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, OXA-48, CTX-M-15, DHA-type, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| Latin America | KPC ± OSBL and/or spectrum undefined (211) | E. coli | 9 | KPC-2 |

| 3 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-type | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 16 | KPC-2 | ||

| 68 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 3 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 84 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-52 | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-120, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 8 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 15 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-30, SHV-OSBL | |||

| K. variicola | 1 | KPC-2 | ||

| KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (207) | E. coli | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15 | |

| K. oxytoca† | 2 | KPC-2 | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-8, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-12 | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-2A | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 3 | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 21 | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-2-type, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-9 | |||

| 3 | KPC-2, CTX-M-12 | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, CTX-M-12, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-12, SHV-12 | |||

| 3 | KPC-2, CTX-M-14 | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-14, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 20 | KPC-2, CTX-M-14, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 3 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15 | |||

| 25 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 37 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-type, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-35, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-67, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 9 | KPC-2, SHV-12 | |||

| 24 | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-23, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, SHV-ESBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, SHV-ESBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-12, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 9 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, SHV-12 | |||

| 14 | KPC-3, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-TYPE, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| R. ornithinolytica | 1 | KPC-3, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | ||

| KPC + AmpC ± OSBL (32) | C. freundii* | 2 | KPC-2 | |

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| C. koseri* | 2 | KPC-2 | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. cloacae* | 5 | KPC-2 | ||

| 8 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. aerogenes* | 3 | KPC-2 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, FOX-5, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| S. marcescens* | 8 | KPC-2 | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (16) | C. freundii* | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-2, TEM-OSBL | |

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-12 | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15 | |||

| E. asburiae* | 2 | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | ||

| E. cloacae* | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-12, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 2 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15 | |||

| 3 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. aerogenes* | 2 | KPC-2, CTX-M-14, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| S. marcescens* | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, CTX-M-59, TEM-OSBL | ||

| KPC + OXA-48-like + OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, OXA-163, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| KPC + OXA-48-like + ESBL + OSBL (2) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, OXA-163, CTX-M-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| 1 | KPC-2, OXA-370, CTX-M-14, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| OXA-48-like ± OSBL (4) | E. coli | 1 | OXA-232, TEM-OSBL | |

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | OXA-163, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| R. ornithinolytica | 1 | OXA-181 | ||

| OXA-48-like + ESBL ± OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | OXA-232, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| MBL ± OSBL (7) | K. pneumoniae | 3 | NDM-1, SHV-OSBL | |

| 3 | NDM-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. variicola | 1 | NDM-1 | ||

| MBL + ESBL ± OSBL (24) | E. coli | 2 | VIM-23, CTX-M-15 | |

| K. oxytoca† | 2 | IMP-8, TEM-OSBL | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 2 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 11 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-ESBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, PER-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | VIM-23, SHV-ESBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-24, CTX-M-15, SHV-ESBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL + AmpC ± OSBL (9) | C. freundii* | 1 | VIM-23 | |

| E. cloacae* | 2 | NDM-1 | ||

| 3 | VIM-23 | |||

| P. rettgeri* | 3 | NDM-1 | ||

| MBL + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (8) | E. cloacae* | 4 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15 | |

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-9 | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-9, TEM-OSBL | |||

| P. rettgeri* | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-12 | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL + GES carbapenemase + ESBL + OSBL (2) | E. coli | 1 | NDM-1, GES-2, CTX-M-55, TEM-OSBL | |

| K. oxytoca† | 1 | NDM-1, GES-2, TEM-OSBL | ||

| MBL + KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-1, KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| Asia/Pacific | GES carbapenemase + ESBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | GES-5, SHV-12 |

| KPC ± OSBL and/or spectrum undefined (9) | E. coli | 2 | KPC-2 | |

| 2 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 4 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (36) | K. oxytoca† | 1 | KPC-2, SHV-12 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | KPC-2, CTX-M-3, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-14, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 19 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-24, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-55, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, CTX-M-65, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, CTX-M-65, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-65, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-90, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-12, SHV-2A | |||

| 1 | KPC-17, SHV-12 | |||

| KPC + AmpC ± OSBL (10) | E. kobei* | 1 | KPC-2 | |

| E. coli | 1 | KPC-2, CMY-2 | ||

| K. aerogenes* | 3 | KPC-2 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, CMY-2, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, CMY-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| S. marcescens* | 1 | KPC-2 | ||

| KPC + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (4) | C. koseri* | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-3, TEM-OSBL | |

| E. cloacae* | 1 | KPC-2, SHV-12, DHA-1 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-27, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-55, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| OXA-48-like ± OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | OXA-48, SHV-OSBL | |

| OXA-48-like + ESBL ± OSBL (5) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| 4 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| OXA-48-like + AmpC ± OSBL (1) | E. coli | 1 | OXA-181, CMY-2, TEM-OSBL | |

| OXA-48-like + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (1) | E. coli | 1 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15, CMY-2, TEM-OSBL | |

| MBL ± OSBL (9) | E. coli | 1 | IMP-59, TEM-OSBL | |

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | IMP-1, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 1 | IMP-4, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 3 | IMP-4, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1 | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, SHV-OSBL | |||

| P. mirabilis | 1 | NDM-1 | ||

| MBL + ESBL ± OSBL (60) | E. coli | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-3 | |

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-27 | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-27, SHV-31 | |||

| 1 | NDM-5, CTX-M-15 | |||

| 2 | NDM-5, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. oxytoca† | 1 | IMP-4 | ||

| 1 | IMP-4, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | IMP-4, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | IMP-1, CTX-M-3, SHV-OSBL | ||

| 2 | IMP-4, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 4 | IMP-4, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | IMP-26, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | IMP-26, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | IMP-26, CTX-M-15, SHV-28 | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-14, SHV-12 | |||

| 2 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15 | |||

| 5 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 14 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, CTX-M-27, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-ESBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, VEB-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-5, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 5 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 4 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL + AmpC ± OSBL (32) | C. freundii* | 7 | IMP-4, TEM-OSBL | |

| 2 | NDM-1 | |||

| 1 | NDM-7 | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, DHA-1 | |||

| E. asburiae* | 1 | IMP-14 | ||

| 1 | NDM-1 | |||

| 2 | NDM-7 | |||

| E. cloacae* | 1 | IMP-1 | ||

| 3 | IMP-4 | |||

| 2 | NDM-1 | |||

| 2 | NDM-1, DHA-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7 | |||

| E. coli | 1 | NDM-5, CMY-42, TEM-OSBL | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | IMP-26, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| P. mirabilis | 1 | IMP-26, DHA-1 | ||

| P. rettgeri* | 2 | NDM-1 | ||

| S. marcescens* | 1 | IMP-4, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | IMP-47, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (42) | C. farmeri* | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |

| C. freundii* | 2 | IMP-8, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-3, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15 | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, SHV-31, DHA-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| C. koseri* | 1 | NDM-1, SHV-31 | ||

| E. asburiae* | 1 | IMP-8, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | ||

| E. cloacae* | 1 | IMP-8, CTX-M-22, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 2 | IMP-14, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | IMP-26, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, SHV-31, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-31 | |||

| 7 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-31, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-31, DHA-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | NDM-1, SHV-12 | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | NDM-7, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. coli | 3 | NDM-5, CTX-M-15, CMY-2, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-5, CTX-M-15, CMY-2, TEM-type | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, CMY-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, DHA-1 | |||

| K. aerogenes* | 1 | IMP-8, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | IMP-26, CTX-M-15, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, SHV-ESBL, DHA-1 | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, DHA-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| P. stuartii* | 1 | VIM-1, VEB-1, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | ||

| S. marcescens* | 1 | IMP-8, CTX-M-3 | ||

| MBL + KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (3) | K. oxytoca† | 2 | IMP-4, KPC-2, SHV-12 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-7, KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | ||

| MBL + OXA-48-like + ESBL ± OSBL (16) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-1, OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |

| 1 | NDM-1, OXA-48, SHV-ESBL | |||

| 3 | NDM-1, OXA-181, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 3 | NDM-1, OXA-232, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 7 | NDM-1, OXA-232, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-4, OXA-48, CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL + OXA-48-like + ESBL + AmpC + OSBL (1) | E. coli | 1 | NDM-5, OXA-181, CTX-M-15, CMY-2, TEM-OSBL | |

| Middle East/Africa | KPC ± OSBL and/or spectrum undefined (18) | E. coli | 1 | KPC-2 |

| 1 | KPC-3 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | KPC-2 | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 7 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 4 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (2) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + AmpC ± OSBL (3) | E. cloacae* | 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |

| E. coli | 1 | KPC-2, CMY-2, TEM-OSBL | ||

| K. aerogenes* | 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | ||

| KPC + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (3) | C. freundii* | 1 | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |

| E. cloacae* | 1 | KPC-3, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, DHA-25, TEM-OSBL | ||

| OXA-48-like ± OSBL (3) | K. pneumoniae | 2 | OXA-181, SHV-OSBL | |

| 1 | OXA-181, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| OXA-48-like + ESBL ± OSBL (29) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-14, SHV-OSBL | |

| 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 3 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 5 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 8 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | OXA-232, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 10 | OXA-232, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| OXA-48-like + AmpC ± OSBL (3) | E. asburiae* | 1 | OXA-48 | |

| E. kobei* | 2 | OXA-48 | ||

| OXA-48-like + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (3) | C. freundii* | 1 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15 | |

| E. cloacae* | 1 | OXA-48, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | ||

| 1 | OXA-181, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL ± OSBL (8) | K. pneumoniae | 2 | NDM-1, SHV-OSBL | |

| 1 | NDM-1, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-5, SHV-OSBL | |||

| P. mirabilis | 4 | VIM-5 | ||

| MBL + ESBL ± OSBL (33) | K. oxytoca† | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |

| 2 | VIM-1 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15 | ||

| 4 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 15 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-55, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-134, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-5, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 4 | NDM-7, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| MBL + AmpC ± OSBL (7) | E. coli | 1 | NDM-5, CMY-42 | |

| 1 | NDM-5, CMY-42, TEM-OSBL | |||

| P. rettgeri* | 3 | NDM-1 | ||

| 1 | NDM-1, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | NDM-1, DHA-type | |||

| MBL + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (11) | C. freundii* | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-9-type | |

| E. asburiae* | 1 | NDM-1, VEB-1, TEM-OSBL | ||

| E. cloacae* | 2 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15 | ||

| 2 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | VIM-4, CTX-M-9 | |||

| 1 | VIM-4, CTX-M-100, TEM-OSBL | |||

| E. coli | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, CMY-6 | ||

| K. aerogenes* | 1 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, TEM-OSBL | ||

| P. stuartii* | 1 | NDM-1, PER-12, DHA-type | ||

| MBL + OXA-48-like + OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | NDM-1, OXA-232, SHV-OSBL | |

| MBL + OXA-48-like + AmpC ± OSBL (1) | E. cloacae* | 1 | VIM-4, OXA-48, CMY-4 | |

| MBL + OXA-48-like + ESBL + AmpC + OSBL (1) | E. cloacae* | 1 | VIM-4, OXA-48, SHV-12, CMY-4, TEM-OSBL | |

| North America | GES carbapenemase ± OSBL (1) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | GES-20, SHV-OSBL |

| KPC ± OSBL and/or spectrum undefined (57) | E. coli | 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |

| 1 | KPC-3 | |||

| 2 | KPC-3, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-18, TEM-OSBL | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2 | ||

| 2 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 8 | KPC-2, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 2 | KPC-3 | |||

| 6 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 30 | KPC-3, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-29, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + ESBL ± OSBL (16) | K. pneumoniae | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL | |

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, SHV-28, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-124, SHV-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-2, SHV-12 | |||

| 2 | KPC-2, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |||

| 1 | KPC-3, SHV-12 | |||

| 8 | KPC-3, SHV-12, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + AmpC ± OSBL (3) | C. farmeri* | 1 | KPC-3 | |

| C. freundii* | 1 | KPC-2 | ||

| 1 | KPC-2, TEM-OSBL | |||

| KPC + ESBL + AmpC ± OSBL (5) | C. freundii* | 1 | KPC-2, VEB-1B, TEM-OSBL | |

| E. asburiae* | 2 | KPC-2, SHV-30, TEM-OSBL | ||

| E. cloacae* | 1 | KPC-2, SHV-5, TEM-OSBL | ||

| E. coli | 1 | KPC-2, CTX-M-15, CMY-2, TEM-OSBL | ||

| MBL + ESBL ± OSBL (2) | K. pneumoniae | 2 | NDM-1, CTX-M-15, SHV-OSBL, TEM-OSBL | |

| MBL + AmpC ± OSBL (3) | C. freundii* | 1 | VIM-1 | |

| 1 | VIM-32 | |||

| E. cloacae* | 1 | VIM-1 |

OSBL, original-spectrum β-lactamase: TEM-type and SHV-type β-lactamases that do not contain amino acid substitutions associated with ESBL activity (e.g., TEM-1, SHV-1, SHV-11); Spectrum undefined: TEM-type and SHV-type β-lactamases whose spectrum of activity has not be determined biochemically; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; MBL, metallo-β-lactamase.

*, presumed to also carry the intrinsic chromosomally encoded AmpC β-lactamase common to this species; †, presumed to also carry the intrinsic chromosomally encoded ESBL common to this species.

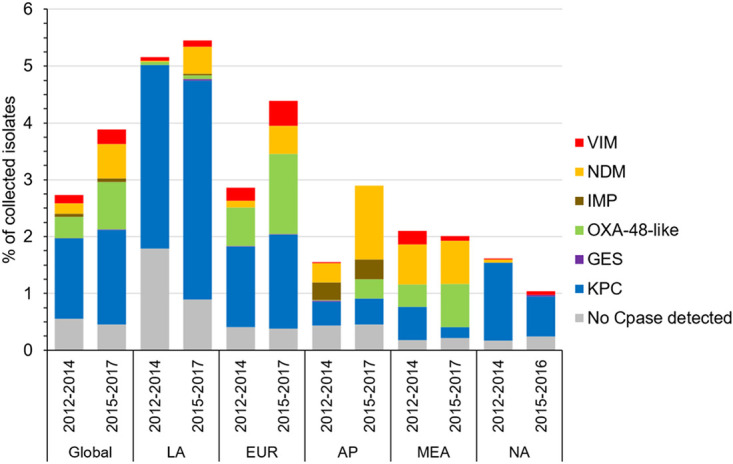

The percentage of meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales collected over the course of this study increased from 2.7% of isolates collected globally in 2012 to 2014 to 3.8% of isolates collected in 2015 to 2017 (Fig. 3). At the regional level, the percentage of meropenem-nonsusceptibility increased among isolates collected in Europe (2.8% versus 4.3%), Asia/South Pacific (1.5% versus 2.6%), and Latin America (5.1% versus 5.4%) was stable among isolates collected in the Middle East/Africa (2.04% versus 1.97%) and decreased among isolates collected in North America (1.6% versus 1.0%). This overall increase could be attributed to the increasing proportion of carbapenemase-positive isolates that was observed, most notably among isolates carrying NDM-type MBLs in Asia/South Pacific, Europe, and Latin America; OXA-48-like carbapenemases in Europe, Middle East/Africa, and Asia/South Pacific; KPC-type carbapenemases in Latin America; and VIM-type MBLs in Europe (Fig. 3). When countries that participated only or primarily during the 2012 to 2014 time period (China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Kenya, and Nigeria) were removed from analysis, a larger increase in the percentage of meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales and increases in KPC-positive isolates and NDM-positive isolates were also revealed in the Asia/South Pacific and Middle East/Africa regions, respectively (see Fig. S4).

FIG 3.

Comparison of the distribution of carbapenem resistance mechanisms identified in meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales isolates collected from 2012 to 2014 and from 2015 to 2017. Region (no. of isolates collected in 2012 to 2014/no. of isolates collected in 2015 to 2017): Global, all surveyed regions (38,190/43,591); LA, Latin America (5,317/7,729); EUR, Europe (18,301/21,850); AP, Asia/South Pacific (7,087/7,051); MEA, Middle East/Africa (3,281/3,690); NA, North America (4,204/3,271 [2015 to 2016 only]). No Cpase detected, no gene encoding a carbapenemase was detected by PCR. Isolates carrying multiple carbapenemases were counted for each individual carbapenemase type.

DISCUSSION

This 2012-2017 global surveillance study provided a perspective on the incidence and carbapenemase carriage of meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales, which varied by geographic region, as reported by others (4–8, 15). Though it is difficult to compare results from independent studies that differ in study design and participation, others have reported broadly similar percentages of meropenem- or imipenem-resistant Enterobacterales (ranging between 1.2 and 1.9% of isolates collected in North America, 1.3 and 3.1% of isolates collected in the Asia/Pacific region, 3.2 and 3.7% of isolates collected in Europe, and 3.5 and 8.4% of isolates collected in Latin America) among isolates collected in 2014 to 2016 (16–18). Similar to other studies, the highest incidence of CRE was observed among K. pneumoniae (19–21). KPC-type, OXA-48-like, and MBL carbapenemases were each found among 14 to 15 Enterobacterales species, but KPC enzymes were predominantly carried by K. pneumoniae, and OXA-48-like enzymes were found mostly among K. pneumoniae and E. coli, in agreement with other reports (7, 22), whereas MBLs were proportionately more common among meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates of Enterobacter spp., Citrobacter spp., the Proteeae, and E. coli (20, 23). As observed by others, the majority of CRE isolates cocarried ESBLs and/or AmpC enzymes, and a number of isolates carried multiple carbapenemases (8). The production of multiple β-lactamases from different Ambler classes, likely encoded on multiple plasmids potentially harboring additional non-β-lactam resistance mechanisms, further adds to the challenges of effectively treating infections caused by these organisms (8, 24).

The overall geographical distribution of Enterobacterales isolates carrying different carbapenemase types reported in the present study agreed with published reports. KPC was the predominant carbapenemase type detected globally, and the largest numbers of KPC-positive isolates were collected in the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Greece, Italy, Israel, China, and the Philippines (data not shown), consistent with reports of their endemicity in all but one of these countries (6, 7, 25–28). The largest numbers of meropenem-nonsusceptible OXA-48-like-positive Enterobacterales isolates were observed in Turkey, Russia, Romania, Spain, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Kuwait, and South Africa (data not shown). Isolates carrying OXA-48 are reported to be endemic in Turkey and countries in the Middle East and North Africa, whereas isolates carrying OXA-48-like β-lactamases (e.g., OXA-181 and OXA-232) are prevalent in the Indian subcontinent, though both OXA-48-positive and OXA-48-like-positive isolates have disseminated widely to countries in Europe, Asia, the Pacific, and southern Africa, including those noted in our study (6, 22, 29, 30). Isolates carrying OXA-48-like enzymes were rarely identified in Latin America and the variants found as part of this study were consistent with those reported by others (27). No OXA-48-like-positive isolates were collected in the United States during the surveyed time period, likely reflecting both their low incidence and good susceptibility to meropenem, the sentinel carbapenem used in this study (31–33). NDM-positive Enterobacterales were found in all regions in this study, consistent with reports of their worldwide dissemination (6, 7, 23), but composed the greatest percentage of meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates in the Asia/South Pacific and Middle East/Africa regions. In other studies, NDM was the most commonly identified carbapenemase reported in a surveillance study conducted in the Asia/South Pacific region from 2008 to 2014 (34) and was observed in the greatest number of African countries in literature searches of carbapenem-resistant organisms (35, 36); NDM was also the most common carbapenemase identified in isolates collected from African patients in a small surveillance study conducted in 2014 to 2015 (37). IMP-positive Enterobacterales were most common in the Asia/South Pacific region and also identified in a small percentage of isolates collected in Latin America, consistent with published reports (7, 8, 20, 27). VIM-positive isolates were found in highest proportions in Europe, Middle East/Africa, and Latin America, primarily in countries where they have been reported by others (7, 26, 27, 35).

The present study demonstrated that the overall percentage of meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales has increased over time on the global and most regional levels. These increases are likely partly attributable to increasing proportions of carbapenemase-positive Enterobacterales isolates, most notably those carrying OXA-48-like and NDM-type enzymes. Others have also noted the growing incidence and dissemination of isolates carrying these carbapenemase types. Increasing CRE rates were reported for the SENTRY global surveillance study and were attributed in part to an increase in isolates carrying genes encoding NDM and OXA-48 variants identified in 2014 to 2016 compared to an earlier time period (21). In Europe, the incidence of CPE and a worsening epidemiological situation were documented in a series of expert reports, which also reported an increase in and rapid spread of OXA-48-positive and NDM-positive Enterobacterales in 2015 relative to prior years (3, 19, 26, 38, 39); similarly, increases in the incidence of NDM-positive isolates and/or OXA-48-positive isolates have been reported on the country level (40–43). In Asia, increasing trends in NDM-positive E. coli and E. cloacae and KPC-positive K. pneumoniae were reported in China in 2013 to 2016, whereas increasing trends in both KPC-positive and OXA-48-positive K. pneumoniae were observed in Taiwan in 2012 to 2015 (28, 44). Increases in carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae also have been documented in Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam in recent years, and NDM-positive isolates are commonly identified in these countries (45). In Latin America, NDM has been reported in several species and as part of outbreaks, notably in Mexico, which was the source of ∼55% of the NDM-positive isolates identified in that region as part of this study (27, 46, 47).

The strength of the present study is that it is a global, multiyear study employing standardized antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular testing methods that were used consistently throughout its course. However, it also has limitations. The study was not designed to determine the prevalence of resistance mechanisms, since investigators were requested to collect a predefined number of isolates of select species comprising major clinically relevant pathogens and pathogens that pose unique treatment challenges. Furthermore, the relatively limited number of medical centers participating in each country may not provide a representation of the full range and diversity of CRE existing in each region. Changes in study participation by individual medical centers and countries over the 6 years surveyed also must be taken into consideration when evaluating regional trends. Only meropenem-nonsusceptible isolates were screened for carbapenemase carriage, likely resulting in an underestimate of the number of isolates carrying OXA-48-like β-lactamases and potentially biasing the results toward resistance mechanisms more specific to meropenem than carbapenems in general (32, 48). Finally, sequence typing was not performed because of the volume of isolates examined.

In the absence of appropriate control measures, CRE can disseminate readily among patients in health care environments. Timely detection of CRE is critical to facilitate optimal implementation of infection prevention and control measures and to inform clinicians who must choose treatment regimens (49–51). Current treatment options for CRE infections include combinations of polymyxins, tigecycline, fosfomycin, and aminoglycosides; β-lactam/non-β-lactam inhibitor combinations utilizing diazabicyclooctanones (ceftazidime-avibactam and imipenem-relebactam) or boronic acid derivatives (meropenem-vaborbactam); and a siderophore cephalosporin (cefiderocol). β-lactam/non-β-lactam inhibitor combinations with promising activity against MBL-positive Enterobacterales (aztreonam-avibactam and cefepime-taniborbactam) and derivatives of older drug classes are also in development (1, 52–54). However, ongoing CRE surveillance combined with a global antimicrobial stewardship strategy, sensitive clinical laboratory detection methods, and adherence to infection control practices will be needed to interrupt the progressive spread of CRE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolate collection.

Nonduplicate isolates of Enterobacterales were collected from patients with urinary tract infections (n = 22,872), skin and soft tissue infections (n = 19,838), lower respiratory tract infections (n = 18,405), intra-abdominal infections (n = 14,964), bloodstream infections (n = 5,559; isolates collected only in 2014 to 2017), and other infections (n = 143) by 232 medical laboratories located in 39 countries in Asia/South Pacific (n = 14,138), Europe (n = 40,151), Latin America (n = 13,046), the Middle East/Africa (n = 6,971), and North America (n = 7,475). Medical centers were requested to contribute a target number of isolates of specified bacterial species regardless of antibiotic susceptibility. Each isolate was deemed to be a clinically significant pathogen by diagnostic algorithms in use in each participating laboratory and was considered the probable causative agent of infection. Participating countries by year are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Nine countries (Austria, China, Hong Kong, Kenya, Malaysia, Nigeria, Poland, Sweden, and the United States) participated in fewer than 6 years of the study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and screening for β-lactamase genes.

All isolates were shipped to a central reference laboratory (IHMA, Schaumburg, IL), where species identification of all isolates was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed at IHMA by broth microdilution following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (55, 56). Enterobacterales isolates testing as nonsusceptible to meropenem (MIC ≥2 μg/ml) were screened for the presence of β-lactamase genes encoding carbapenemases (KPC, OXA-48-like, GES, NDM, IMP, VIM, SPM, and GIM) and other β-lactamases (TEM, SHV, CTX-M-1 group, CTX-M-2 group, CTX-M-8 group, CTX-M-9 group, CTX-M-25 group, VEB, PER, ACC, ACT, CMY, DHA, FOX, MIR, and MOX) using a combination of microarray and multiplex PCR assays, followed by amplification and sequencing of the full-length genes and comparison to publicly available databases (57).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study investigators, laboratory personnel, and all members of the global surveillance program who contributed isolates and information for this study.

This study was sponsored by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP and Pfizer, Inc., which also included compensation fees for manuscript preparation, and was funded in part with federal funds from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), under OT number HHSO100201500029C.

K.M.K., J.A.K., B.L.M.D.J., and G.G.S. wrote and edited the manuscript. K.M.K. and D.F.S. are employees of IHMA, who were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with the development of the manuscript. J.A.K. is a consultant for IHMA and an employee of the University of Manitoba and Shared Health Manitoba. None of the IHMA authors or J.A.K. has a personal financial interest in the sponsor of this paper (Pfizer, Inc.). G.G.S., an employee of and shareholder in AstraZeneca at the time of the study, is currently an employee of Pfizer. B.L.M.D.J. is a former employee of and shareholder in AstraZeneca and a former employee of Pfizer. All authors provided analysis input and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodriguez-Bano J, Gutierrez-Gutierrez B, Machuca I, Pascual A. 2018. Treatment of infections caused by extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-, AmpC-, and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev 31:e00079-17. 10.1128/CMR.00079-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. 2011. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1791–1798. 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canton R, Akova M, Carmeli Y, Giske CG, Glupczynski Y, Gniadkowski M, Livermore DM, Miriagou V, Naas T, Rossolini GM, Samuelsen O, Seifert H, Woodford N, Nordmann P, The European Network on Carbapenemases. 2012. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:413–431. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel G, Bonomo RA. 2013. Stormy waters ahead”: global emergence of carbapenemases. Front Microbiol 4:48. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2014. The difficult-to-control spread of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:821–830. 10.1111/1469-0691.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Duin D, Doi Y. 2017. The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence 8:460–469. 10.1080/21505594.2016.1222343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Logan LK, Weinstein RA. 2017. The epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the impact and evolution of a global menace. J Infect Dis 215:S28–S36. 10.1093/infdis/jiw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush K, Bradford PA. 2020. Epidemiology of β-lactamase-producing pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 33:e00047-19. 10.1128/CMR.00047-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush K, Jacoby GA. 2010. Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:969–976. 10.1128/AAC.01009-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bush K. 2013. Carbapenemases: partners in crime. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 1:7–16. 10.1016/j.jgar.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacoby GA, Mills DM, Chow N. 2004. Role of β-lactamases and porins in resistance to ertapenem and other β-lactams in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3203–3206. 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3203-3206.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Boxtel R, Wattel AA, Arenas J, Goessens WHF, Tommassen J. 2017. Acquisition of carbapenem resistance by plasmid-encoded-AmpC-expressing Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01413-16. 10.1128/AAC.01413-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X-Z, Plesiat P, Nikaido H. 2015. The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:337–418. 10.1128/CMR.00117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adler M, Anjum M, Andersson DI, Sandegren L. 2016. Combinations of mutations in envZ, ftsI, mrdA, acrB, and acrR can cause high-level carbapenem resistance in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1188–1198. 10.1093/jac/dkv475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nordmann P, Poirel L. 2019. Epidemiology and diagnostics of carbapenem resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis 69:S521–S528. 10.1093/cid/ciz824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castanheira M, Huband MD, Mendes RE, Flamm RK. 2017. Meropenem-vaborbactam tested against contemporary gram-negative isolates collected worldwide during 2014, including carbapenemase-resistant, KPC-producing, multidrug-resistant, and extensively drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00567-17. 10.1128/AAC.00567-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaller MA, Huband MD, Mendes RE, Flamm RK, Castanheira M. 2018. In vitro activity of meropenem/vaborbactam and characterization of carbapenem resistance mechanisms among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from the 2015 meropenem/vaborbactam surveillance programme. Int J Antimicrob Agents 52:144–150. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaller MA, Huband MD, Streit JM, Flamm RK, Sader HS. 2018. Surveillance of tigecycline activity tested against clinical isolates from a global (North America, Europe, Latin America, and Asia-Pacific) collection (2016). Int J Antimicrob Agents 51:848–853. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasner C, Albiger B, Buist G, Tambić AA, Canton R, Carmeli Y, Friedrich AW, Giske CG, Glupczynski Y, Gniadkowski M, Livermore DM, Nordmann P, Poirel L, Rossolini GM, Seifert H, Vatopoulos A, Walsh T, Woodford N, Donker T, Monnet DL, Grundmann H, European Survey on Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE) Working Group. 2013. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: a survey among national experts from 39 countries, February 2013. Euro Surveill 18:20525. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.28.20525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlowsky JA, Lob SH, Kazmierczak KM, Badal RE, Young K, Motyl MR, Sahm DF. 2017. In vitro activity of imipenem against carbapenemase-positive Enterobacteriaceae isolates collected by the SMART global surveillance program from 2008 to 2014. J Clin Microbiol 55:1638–1649. 10.1128/JCM.02316-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castanheira M, Deshpande L, Mendes RE, Canton R, Sader HS, Jones RN. 2019. Variations in the occurrence of resistance phenotypes and carbapenemase genes among Enterobacteriaceae isolates in 20 years of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Open Forum Infect Dis 6:S23–S33. 10.1093/ofid/ofy347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitout JDD, Peirano G, Kock MM, Strydom KA, Matsumura Y. 2020. The global ascendency of OXA-48-type carbapenemases. Clin Microbiol Rev 33:e00102-19. 10.1128/CMR.00102-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu W, Feng Y, Tang G, Qiao F, McNally A, Zong Z. 2019. NDM metallo-β-lactamases and their bacterial producers in health care settings. Clin Microbiol Rev 32:e00115-18. 10.1128/CMR.00115-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navon-Venezia S, Kondratyeva K, Carattoli A. 2017. Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:252–275. 10.1093/femsre/fux013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazmierczak KM, Biedenbach DJ, Hackel M, Rabine S, de Jonge BL, Bouchillon SK, Sahm DF, Bradford PA. 2016. Global dissemination of blaKPC into bacterial species beyond Klebsiella pneumoniae and in vitro susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4490–4500. 10.1128/AAC.00107-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albiger B, Glasner C, Struelens MJ, Grundmann H, Monnet DL, European Survey on Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE) working group. 2015. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: assessment by national experts from 38 countries, May 2015. Euro Surveill 20:30062. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.45.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escandon-Vargas K, Reyes S, Gutierrez S, Villegas MV. 2017. The epidemiology of carbapenemases in Latin America and the Caribbean. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther 15:277–297. 10.1080/14787210.2017.1268918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Wang X, Wang J, Ouyang P, Jin C, Wang R, Zhang Y, Jin L, Chen H, Wang Z, Zhang F, Cao B, Xie L, Liao K, Gu B, Yang C, Liu Z, Ma X, Jin L, Zhang X, Man S, Li W, Pei F, Xu X, Jin Y, Ji P, Wang H. 2018. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: data from a longitudinal large-scale CRE study in China (2012-2016. ). Clin Infect Dis 67:S196–S205. 10.1093/cid/ciy660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazmierczak KM, Bradford PA, Stone GG, de Jonge BLM, Sahm DF. 2018. In vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam against OXA-48-carrying Enterobacteriaceae isolated as part of the International Network for Optimal Resistance Monitoring (INFORM) global surveillance program from 2012-2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e00592-18. 10.1128/AAC.00592-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poirel L, Potron A, Nordmann P. 2012. OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1597–1606. 10.1093/jac/dks121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyman M, Walters M, Lonsway D, Rasheed K, Limbago B, Kallen A. 2015. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae producing OXA-48-like carbapenemases: United States, 2010-2015. Morbidity and Mortality Wkly Report 64:1315–1316. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6447a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potron A, Poirel L, Rondinaud E, Nordmann P. 2013. Intercontinental spread of OXA-48 beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae over a 11-year period, 2001 to 2011. Euro Surveill 18:20549. 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.31.20549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hopkins KL, Meunier D, Mustafa N, Pike R, Woodford N. 2019. Evaluation of temocillin and meropenem MICs as diagnostic markers for OXA-48-like carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:3641–3643. 10.1093/jac/dkz383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jean SS, Hsueh PR, SMART Asia-Pacific Group. 2017. Distribution of ESBLs, AmpC β-lactamases and carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae isolates causing intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections in the Asia-Pacific region during 2008-2014: results from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART). J Antimicrob Chemother 72:166–171. 10.1093/jac/dkw398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manenzhe RI, Zar HJ, Nicol MP, Kaba M. 2015. The spread of carbapenemase-producing bacteria in Africa: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:23–40. 10.1093/jac/dku356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitgang EA, Hartley DM, Malchione MD, Koch M, Goodman JL. 2018. Review and mapping of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Africa: using diverse data to inform surveillance gaps. Int J Antimicrob Agents 52:372–384. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewardson AJ, Marimuthu K, Sengupta S, Allignol A, El-Bouseary M, Carvalho MJ, Hassan B, Delgado-Ramirez MA, Arora A, Bagga R, Owusu-Ofori AK, Ovosi JO, Aliyu S, Saad H, Kanj SS, Khanal B, Bhattarai B, Saha SK, Uddin J, Barman P, Sharma L, El-Banna T, Zahra R, Saleemi MA, Kaur A, Iregbu K, Uwaezuoke NS, Abi Hanna P, Feghali R, Correa AL, Munera MI, Le TAT, Tran TTN, Phukan C, Phukan C, Valderrama-Beltrán SL, Alvarez-Moreno C, Walsh TR, Harbarth S. 2019. Effect of carbapenem resistance on outcomes of bloodstream infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae in low-income and middle-income countries (PANORAMA): a multinational prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 19:601–610. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grundmann H, Livermore DM, Giske CG, Canton R, Rossolini GM, Campos J, Vatopoulos A, Gniadkowski M, Toth A, Pfeifer Y, Jarlier V, Carmeli Y, CNSE Working Group. 2010. Carbapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: conclusions from a meeting of national experts. Euro Surveill 15:19711. 10.2807/ese.15.46.19711-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brolund A, Lagerqvist N, Byfors S, Struelens MJ, Monnet DL, Albiger B, Kohlenberg A, European Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Surveillance Network (EURGen-Net) Capacity Survey Group. 2019. Worsening epidemiological situation of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe, assessment by national experts from 37 countries, July 2018. Euro Surveill 24:1900123. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.9.1900123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortega A, Saez D, Bautista V, Fernandez-Romero S, Lara N, Aracil B, Perez-Vazquez M, Campos J, Oteo J, Spanish Collaborating Group for the Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Programme. 2016. Carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli is becoming more prevalent in Spain mainly because of the polyclonal dissemination of OXA-48. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:2131–2138. 10.1093/jac/dkw148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Findlay J, Hopkins KL, Loy R, Doumith M, Meunier D, Hill R, Pike R, Mustafa N, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2017. OXA-48-like carbapenemases in the UK: an analysis of isolates and cases from 2007 to 2014. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:1340–1349. 10.1093/jac/dkx012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dortet L, Cuzon G, Ponties V, Nordmann P. 2017. Trends in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, France, 2012 to 2014. Euro Surveill 22:30461. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.6.30461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang TD, Bogaerts P, Berhin C, Hoebeke M, Bauraing C, Glupczynski Y, on behalf of a multicenter study group . 2017. Increasing proportion of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and emergence of a MCR-1 producer through a multicentric study among hospital-based and private laboratories in Belgium from September to November 2015. Euro Surveill 22:30530. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.19.30530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiu S-K, Ma L, Chan M-C, Lin Y-T, Fung C-P, Wu T-L, Chuang Y-C, Lu P-L, Wang J-T, Lin J-C, Yeh K-M. 2018. Carbapenem nonsusceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan: dissemination and increasing resistance of carbapenemase producers during 2012-2015. Sci Rep 8:8468. 10.1038/s41598-018-26691-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsu LY, Apisarnthanarak A, Khan E, Suwantarat N, Ghafur A, Tambyah PA. 2016. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterobacteriaceae in South and Southeast Asia. Clin Microbiol Rev 30:1–22. 10.1128/CMR.00042-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torres-Gonzalez P, Bobadilla-del Valle M, Tovar-Calderon E, Leal-Vega F, Hernandez-Cruz A, Martinez-Gamboa A, Niembro-Ortega MD, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Ponce-de LA. 2015. Outbreak caused by Enterobacteriaceae harboring NDM-1 metallo-β-lactamase carried in an IncFII plasmid in a tertiary care hospital in Mexico City. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:7080–7083. 10.1128/AAC.00055-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bocanegra-Ibarias P, Garza-Gonzalez E, Morfin-Otero R, Barrios H, Villarreal-Trevino L, Rodriguez-Noriega E, Garza-Ramos U, Petersen-Morfin S, Silva-Sanchez J. 2017. Molecular and microbiological report of a hospital outbreak of NDM-1-carrying Enterobacteriaceae in Mexico. PLoS One 12:e0179651. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dupont H, Gaillot O, Goetgheluck AS, Plassart C, Emond JP, Lecuru M, Gaillard N, Derdouri S, Lemaire B, de Courtilles MG, Cattoir V, Mammeri H. 2015. Molecular characterization of carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterial isolates collected during a prospective interregional survey in France and susceptibility to the novel ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:215–212. 10.1128/AAC.01559-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman ND, Carmeli Y, Walton AL, Schwaber MJ. 2017. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a strategic roadmap for infection control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 38:580–594. 10.1017/ice.2017.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonomo RA, Burd EM, Conly J, Limbago BM, Poirel L, Segre JA, Westblade LF. 2018. Carbapenemase-producing organisms: a global scourge. Clin Infect Dis 66:1290–1297. 10.1093/cid/cix893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]