Abstract

Background:

This systematic review was conducted to review the studies investigating the role of dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) diet in prevalence and progression of the metabolic syndrome (MetS) in children, adolescents, and adults.

Methods:

Electronic searches for included studies were performed in MEDLINE, SCOPUS, EMBASE, Cochrane Trial Register, and ISI Web of Science until 30 March 2020. Study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were fulfilled independently by two reviewers using predefined criteria. Studies were included if they assessed the role of adherence to DASH diet in risk of incidence, prevalence, and development of MetS.

Results:

Twelve eligible studies (eight observational studies and four clinical trials) were identified. Despite methodological heterogeneity, limited statistical power, and the cross-sectional nature of most of observational studies, greater adherence to DASH diet was associated with reduced risk of MetS. However, results for change in metabolic characteristics based on dietary intervention with DASH diet in some interventional studies were somewhat controversial.

Conclusions:

The current study demonstrates that, based on observational studies, greater adherence to a DASH diet is inversely associated with MetS presence and progression. However, more interventional studies are needed in this regard to clarify the exact effect of DASH diet on MetS.

Keywords: DASH diet, dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet, metabolic syndrome, systematic review

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) as a pathologic condition is characterized by a cluster of five components, including hyperglycemia, central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and elevated blood pressure (BP) levels.[1] This disorder is a major public health problem with dramatic rising in its global incidence and prevalence.[2,3] It is reported that prevalence of MetS in the world is about 20–25% of all adult population.[3] Metabolic syndrome play essential role in occurring of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and therefore increase mortality, extremely.[4,5] It has been obviously seen that all components of MetS are subject of the interactions of genetic and environmental factors.[6] Of environmental factors, dietary pattern, physical activity, and weight control are important determinants in the prevention or management of MetS.[4,7,8,9]

The dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) diet focuses on consuming higher amounts of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts; moderate intake of low-fat dairy; and low intake of red or processed meats and sweetened beverages, and it is primarily coined for the treatment of hypertension by Fung et al.[10] However, this dietary pattern which is high in beneficial micronutrients such as potassium, magnesium, calcium, unsaturated fatty acids, and fiber is also recommended as a healthy eating dietary pattern.10]

Several observational reports provided convincing evidence that a greater adherence to DASH diet conferred a significant protection against risk of MetS[12,13,14,15,16,17,18] and its components including central adiposity[19,20] and lipid profile.[21] However, in the Joyce et al. study, there was no significant association between higher adherence to DASH diet and risk of MetS.[22] In clinical trials, the beneficial effect of high compliance to DASH style diet in protection against development of MetS and reducing BP have been reported; however, the results of these clinical trials on the possible protective effects of DASH style diet on several MetS components such as hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL-C, central obesity, and glucose intolerance are not entirely convincing.[23,24,25,26]

Studies have proposed some mechanisms for beneficial effects of higher adherence to a DASH diet on risk of MetS, although their pathways are not clearly known. Higher intakes of fiber, folate, potassium, magnesium, calcium, vitamin C, and phytochemicals such as phytoesterol, carotenoids, and flavonoids in the DASH diet may have a beneficial effect on blood pressure, lipid profile, insulin sensitivity, total antioxidant capacity, and reduction in risk of MetS.[27,28]

To our knowledge, no previous systematic review has analyzed the beneficial effect of DASH diet on MetS prevalence, incidence, and progression. As there is an increasing incidence of MetS with its life-threatening comorbidities worldwide, it is very important to know whether the higher adherence to DASH diet could be effective on prevention or treatment of MetS. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to summarize the findings of observational and interventional studies that assessed the effect of higher adherence to DASH diet on prevalence, incidence, or development of MetS in children, adolescents, and adults.

Methods

Data sources and searches

Systematic literature review of relevant published papers until March 2020 was conducted using MEDLINE, SCOPUS, EMBASE, Cochrane Trial Register, and ISI Web of Science. We used the following relevant keywords: (”dietary approaches to stop hypertension” OR “DASH”) AND (”metabolic syndrome” OR “MetS” OR “metabolic disorders”). Reference list of all related articles and reviews also were searched to find other relevant articles. Two reviewers (H F and H E) independently screened the output of the search to identify potentially eligible studies.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

All human studies, which were conducted on the role of DASH dietary pattern on prevention (cohort and cross-sectional) or treatment (clinical trials) of MetS in children, adolescents, and adults. The main outcomes of interest in these studies were odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) for MetS and mean ± SD changes in its components based on the DASH diets. In case of multiple publications or papers from the same population, we preserved the study with the largest sample size or with the most complete results.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded the papers that are not original research (reviews, editorials, and non-research letters). Case reports or case series, ecologic studies, cell-culture or animal studies were also excluded. Studies that did not assess the DASH diet as exposure variable or investigated only some components of the DASH diet were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they were non-English studies, if they contained irrelevant content, and if the full text was unavailable. Finally, studies were excluded if they did not use standard definition for estimation of MetS.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (H F and H E) independently screened the output of the search (based on the title and abstracts of searched papers) to identify potentially eligible studies. Any discrepancies or differences were resolved by discussion with the third author (P M). If necessary, data were requested from the authors. The EndNote X7.1 (version X7, for Windows, Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA) software was used to extract data. The following information from the selected papers were extracted: year of publication, the first author's name, design of study (cohort, cross sectional, and clinical trials), sample size, number of participants, age and gender of participants, follow-up time of cohort studies and trials, exposure (DASH diet), outcome (MetS), exposure and outcome assessment, mean (SD) changes in metabolic indices, adjusted risk estimate [relative risk (RR), hazard ratio (HR), or odds ratios (OR)] with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and adjusted confounding variables.

Quality assessment

Two authors (GA, HF) assessed the risk of bias in the included study, independently. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to assess the quality of included observational studies (cross sectional studies and cohort studies). We assessed the quality assessment of clinical trials, focusing on the following criteria: randomization, allocation concealment, blinding of personnel and of participants, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias using the Jadad scale.

Results

Search results and study selection

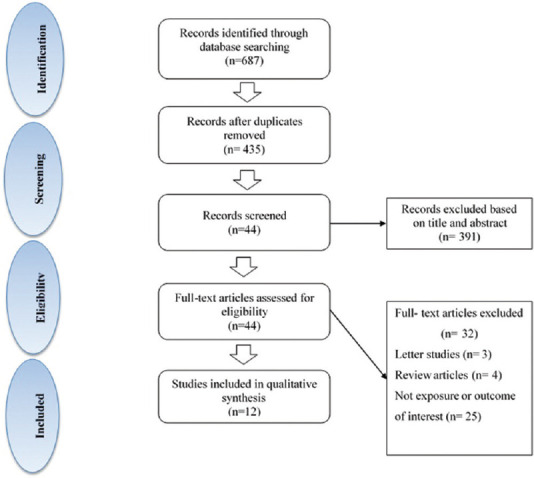

The flowchart of the selection process of publications for this systematic review is indicated in Figure 1. A total of 687 studies were initially identified in these databases with limiting to studies published in English. Of 687 studies selected, 252 publications were excluded because they were duplicate. 44 studies were included on the basis of title or abstract screening. We excluded 32 articles because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 12 articles (six cross-sectional studies, two cohort studies, and four clinical trials) which were in accordance with our inclusion criteria remained for more detailed evaluation. These papers are published between 2005 and 2020. The characteristics of these included studies were reported in Tables 1-3.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of identification of included observational and interventional studies

Table 1.

Summary of results of cohort studies (n=2) on the DASH diet and metabolic syndrome

| Authors, year, and reference | Country | Sample Size (n) | Follow-up | Age years | Sex | DASH diet score definition (components) | Assessment of the metabolic syndrome | Results | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pimenta et al. 2015[18] | Spain | 6851 | 8.3 years | adults | Men/women | DASH diet (+): whole grain, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, low-fat dairy products, (−): red and processed meat, sweetened beverages, and sodium DASH score range: 8-40 | AHA/NHLBI | Greater Adherence to DASH diet: ↓ Incidence of MetS, but only if they had low alcohol intake ((RR=0.41, 95% CI=0.20-0.85), (P for trend=0.023)) | 9 |

| Asghari et al. 2016[16] | Iran | 425 | 3.6 years | 6-18 | Girls/sons | DASH diet (+): whole grain, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, low-fat dairy products, (−): red and processed meat, sweetened beverages, and sodium DASH score range: 8-40 | JIS | High Adherence to DASH diet: ↓ Incidence of MetS ((OR: 0.36,95%%CI: 0.14-0.94), (P for trend=0.023)) | 9 |

Table 3.

Characteristics of clinical trials (n=4) that assessed the effect of the DASH diet on the development of the metabolic syndrome

| Authors, year, and reference | Sample Size (n) | Country | Follow-up | Age years | Sex | Intervention | Assessment of the metabolic syndrome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azadbakht et al. 2005[26] | 116 | Iran | 6 months | Adults | Men/women | Three diets were prescribed for 6 months: 1) a control diet, 2) a weight-reducing diet, 3) the DASH diet with reduced calories and increased consumption of fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and whole grains and lower in saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol and restricted to 2,400 mg Na. | ATP III | In compared to control diet, the DASH diet resulted in higher HDL-C, lower TGs, SBP, weight, FBG among men and women. |

| Saneei et al. 2013[25] | 60 | Iran | 6Ws intervention 4Ws washout 6Ws intervention | 11-18 | Girls | Sixty post pubescent adolescent girls with the MetS were randomized to either a DASH style diet or usual dietary advice for 6 weeks. | ATP III modified for children and adolescents | Changes in SBP, TGs, FPG, HDL-C, weight, WC and BMI were not significantly different between the two groups. The DASH diet prevented the increase in DBP compared with UDA (P=0.01). Compared with the UDA group, the DASH group experienced a significant reduction in prevalence of MetS and high BP. |

| Hikmat et al. 2014[24] | 410 | United states | 8 weeks | ≥ 22 | Men/women | Participants were classified based on MetS status and were randomized to receive a control diet (a diet rich in fruits and vegetables) or the DASH diet. | ATP III | In the MS subgroup, the DASH diet compared with the control diet reduced systolic BP by 4.9 mm Hg (P=0.006) and diastolic BP by 1.9 mm Hg (P=0.15). The DASH diet controlled hypertension in 75% of hypertensive participants with MS (adjusted odds ratio=9.5 vs the control diet, P=0.05). |

| Choi et al. 2015[23] | 39 Intervention: 21 Control: 18 | Korea | 8 weeks | ≥ 60 | Women | The treatment group received a weekly tailored nutritional program and the control group received only one educational session. | NCEP-ATP III modified for Asian Pacific Region | The oxidative stress (P<0.001) was lower in the experimental group than in the control group. LDL-C (P=0.023) had significantly decreased in the experimental group. |

MetS=Metabolic syndrome, DASH=Dietary approach to stop hypertension, Ws=Weeks, UDA=Usual dietary advices, LDL-C=Low density lipoprotein, -cholesterol, HDL-C=High density lipoprotein, -cholesterol, TGs=Triglycerides, SBP=Systolic blood pressure, DBP=Diastolic blood pressure, FPG=Fasting plasma glucose, WC=Waist circumference, BMI=Body mass index

Cohort studies

Of all eligible publications, two were prospective cohort study which provided evidence of a significant protective effect of the DASH diet against MetS incidence [Table 1]. One cohort study with 8.3-year follow-up period conducted on 6,851 Spanish participants. Pimenta et al. have assessed the association between adherence to DASH dietary patterns and risk of MetS in framework of the “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) Project. In this study, the International Diabetes Federation and American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI) harmonizing definition were used to define the MetS. In final model, after adjustment for age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and BMI, the higher adherence to DASH diet was not associated with risk of MetS [RR = 0.82, 95% (0.64–1.03), (P for trend = 0.083)]. However, the stratified analyses by tertiles of alcohol consumption indicated that a greater adherence to the DASH diet is associated inversely with risk of the MetS among participants, only if they had low alcohol intake [(RR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.20–0.85), (P for trend = 0.023)].[18] Another cohort study conducted on 425 healthy Iranian subjects, aged 6–18 years by Asghari et al. The DASH-style diet score was determined based on eight components using 147-items FFQ. MetS was defined according to the definition which proposed by JIS. This study has reported that higher adherence to DASH diet is associated negatively with risk of MetS in children and adolescents. They indicated that the OR (95% CI) of MetS incident in the highest quartile of DASH diet is higher than those in the lowest quartile of DASH score [(0.36 95% CI: 0.14-0.94), (P for trend = 0.023)].[16] Also, in this study, individuals in the highest quartile of DASH diet had lower odds of developing abdominal obesity (OR: 0.35, 95% CI 0.14–0.89), high fasting blood glucose (FPG) (OR: 0.40, 95% CI 0.15-0.99), and hypertension (OR: 0.30, 95% CI 0.10-0.88) compared with those in the lowest quartile of this dietary pattern.

Cross-sectional studies

Six cross-sectional studies were included in current study [Table 2]. One study in Iran enrolled 420 female nurses aged >30 years. The DASH diet score was determined based on 8 components emphasized or minimized in the DASH diet. The MetS was defined according to the JIS. Results of this study showed that in fully adjusted model, after controlling potential confounding factors including age, smoking habits, socioeconomic status, marital status, menopausal situation, medical history, and current use of medications, participants in the highest tertile of DASH diet (assessed using a 8-item score with a range of 8–40 points) had lower risk of MetS than those in the lowest ones (OR 0.37; 95% CI 0.14–0.91).[15] Also, a study performed on 6,826 postmenopausal Korean women, aged between 49 and 70 years, has been reported that DASH diet was associated with lower prevalence of MetS.[12] They have assessed DASH diet based on six nutrients (protein, fat, fiber, calcium, potassium, and sodium) using the DASH-Korean quartile model (range of DASH score: 6–24 points). In this study, the number of participants with MetS in DASH quartile of 1, 2, 3, and 4 was 37.4%, 31.1%, 30.5%, and 30.3%, respectively. Based on multivariate logistic regression analyses, Kang et al. indicated that every increase in the DASH diet score by 1 showed a 0.977-fold odds for MetS.[12] In framework of the ELSA-Brasil study, a cross-sectional study has been conducted on 10,010 Brazilian civil servants, aged 35–74 years. DASH diet was determined using a validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), with 114 food and drink items. The joint interim statement consensus criteria were used for diagnosing MetS. In this study, the fully adjusted model was adjusted for age, sex, race, education, family income, occupational status, study center, menopausal status, family history of diabetes, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol, and calorie intake. They indicated that in multivariable model, there is a borderline inverse association (non-significant) between higher adherence to the DASH diet [score ranging from 8 (lowest adherence) to 40 (highest adherence] and risk of MetS [(OR: 0.88, 95%CI: 0.74, 1.05), (P for trend: 0.044)].[13] Furthermore, Park et al. assessed the association of the DASH diet with metabolically healthy obese (MHO) and metabolically unhealthy normal weight (MUNW) phenotypes in U.S. population.[14] The DASH diet score was determined using dietary data of 2767 adults aged 20–90 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 1988–1994 (using Mellen's index as a nutrient-based index with 9 components). This study revealed that higher DASH diet score was associated with lower odds of MUNW phenotype [(OR: 0.59, 95% CI, 0.38–0.93), (P trend = 0.03)] in the younger group men or women (aged <45 years). However, no significant associations of DASH diet score with metabolic health status were observed in the older participants (aged ≥45 years). In a cross-sectional study, Ghorabi et al. have performed the association of DASH diet and risk of MetS on 396 Iranian adults, aged ≥18 years. The guideline of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) was used to define the MetS. They have observed an inverse association between adherence to DASH diet (score ranging: 8–80 points) and odds of MetS (OR: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.54) via controlling confounding effect of energy intake, socioeconomic status, and body mass index. Also, higher adherence to DASH diet was negatively related to elevated BP (OR: 0.12, 95% CI: 0.05–0.29), high serum triglyceride (TG) (OR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.28–1.00) and low serum HDL-C (OR: 0.51, 95% CI: 0.25–1.01).[17]

Table 2.

Summary of results of cross-sectional study (n=6) on the DASH diet and metabolic syndrome

| Authors, year, and reference | Sample Size (n) | Country | Age years | Sex | DASH diet score definition (components) | Assessment of the metabolic syndrome | Results | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joyce et al. 2019[22] | 10741 | United States | 18-74 | Men/women | DASH diet (+):total and whole grains, vegetables (excluding potatoes), fruits (including juice), dairy, nuts/seeds/legumes, (−): red/processed meat, fats/oils, and sweets

DASH score range: 0-80 |

AHA/NHLBI 2009 JIS | There is no associations between DASH and MetS prevalence in all population study(OR: 0.95, 95%CI: 0.88, 1.02). | 7 |

| Ghorabi et al. 2019[17] | 396 | Iran | ≥18 | Men/women | DASH diet (+): fruits, vegetables, nuts and legume, dairy products, and low intake of grains, (−):sugar-sweetened beverages and sweets, sodium, and red and processed meats DASH score range: 8-80 |

NCEP ATP III |

Higher adherence to DASH diet: ↓ odds of MetS (OR: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.54) | 6 |

| Kang et al. 2018[12] | 6826 | Korea | 49-70 | Women | Protein, fat, fiber, calcium, potassium, and sodium DASH score range: 4-24 |

ATP III | Every increase in the DASH-KQ score by 1 exhibited a 0.977-fold odds for metabolic syndrome. | 7 |

| Drehmer et al. 2017[13] | 10010 | Brazil | 35-74 | Men/women | DASH diet (+): whole grain, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, low-fat dairy products, (−): red and processed meat, sweetened beverages, and sodium DASH score range: 8-40 |

JIS | Higher Adherence to the DASH Diet: ↓ odds of MetS ((OR: 0.88, 95%CI: 0.74-1.05), (P for trend: 0.044)) | 7 |

| Park YM et al. 2017[14] | 2767 | United States | 20-90 | Men/women | DASH diet (+): protein, fiber, magnesium, calcium, and potassium,(−): total fat, saturated fat, sodium, and cholesterol DASH score range: 0-9 |

ATP-III | Higher DASH index was associated with lower odds of MONW phenotype :((OR: 0.59, 95% CI, 0.38-0.93); P trend=0.03)) in the younger age group (<45 years for men or premenopausal women) | 7 |

| Saneei et al. 2015[15] | 420 | Iran | >30 | Women | DASH diet (+): fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, low-fat dairy products, and whole grains, (−): sodium, sweetened beverages, and red and processed meats DASH score range: 8-40 |

JIS | Higher DASH diet score was associated with lower odds of MetS: (OR 0.37; 95% CI 0.14-0.91) | 5 |

(+)=Positive component, (−)=Negative component. DASH=Dietary approach to stop hypertension; MetS=Metabolic syndrome; OR=Odds ratio; CI=Confidence interval; ATP III=Adult Treatment Panel III; AHA=American Heart Association; NCEP=National Cholesterol Education Program; JIS=Joint Interim Societies; NHLBI=National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; MONW=Metabolic obese normal weight

However, in United States, Joyce et al. study has investigated the associations between DASH diet and prevalence of MetS on 10,741 adults aged 18–74 in diverse Hispanics/Latinos.[22] In this study, MetS was defined as the presence of three or more of the criteria including abdominal obesity, elevated blood pressure, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, and impaired fasting glucose. DASH diet was assessed using 8-item score with a range of 0–80 points. in multivariable model, after controlling confounding factors (including age, sex, site, nativity, smoking status, alcoholic drinks, education, household income, marital status, depressive and anxiety symptoms, baseline visit season, physical activity, energy intake, and health insurance status), there was no associations between higher adherence to DASH diet and risk of MetS (OR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.88, 1.02).

Clinical trial studies

Four clinical trials assessing the effect of higher adherence to the DASH diet on MetS were included in this systematic review [Table 3]. The first one was conducted in Iran, that is, assessed the possible effect of DASH eating plan on characteristics of the MetS in 116 patients (34 men and 82 women) for 6 months.[26] The ATP III criteria were used to determine the MetS. The mean ± SD age of participants was 41.2 ± 12.3 years. According to results of this study, in comparison to control diet, the DASH diet resulted in higher HDL-C (7 and 10 mg/dl), lower TGs (−18 and −14 mg/dl), SBP (−12 and −11 mmHg), DBP (−6 and −7 mmHg), fasting blood glucose (−15 and −8 mg/dl), and weight (−16 and −15 kg) among participants (all P < 0.001).

Also, in another randomized cross-over clinical trial conducted in Iran; 60 post-pubescent adolescent girls with the MetS were randomized to either a DASH style diet or usual dietary advice for 6 weeks. After a 4-week washout period, the patients were crossed over to the alternate arm. The mean ± SD age of the subjects was 14·2 ± 1·7 years. To definition of MetS in participants, ATP III criteria was used, which was modified for children and adolescents. In this study, there is no significant difference in changes of weight, waist circumference, and body mass index between the two intervention phases. Also, the recommendations to follow DASH diet did not have significant effect on serum levels of FPG and lipid profiles. However, compared with the usual dietary advice group, DASH group showed a significant decrease in the prevalence of MetS and high BP.[25]

According to a randomized clinical trial in USA,[24] an effect of the DASH diet on BP in patients with and without MetS has been assessed. Participants, aged 22 years old, were classified based on MetS status (99 with MetS, 311 without MetS) and were randomized to receive a control diet (a diet rich in fruits and vegetables) or the DASH diet. ATP III criteria were used to determine the MetS. In the MetS subgroup, compared with the control diet, the DASH diet reduced systolic BP by 4.9 mmHg (P < 0.05) and diastolic BP by 1.9 mmHg (P > 0.05). In the group without MetS, corresponding net BP reductions were 5.2 mmHg and 2.9 mmHg, respectively (P < 0.001). Also, in the MetS subgroup, the DASH diet had beneficial effect on controlling hypertension (67% vs 17%, OR = 9.5, P = 0.05) in comparison to the control diet group.

Choi et al. study has investigated the effects of DASH diet on MetS parameters in Korean elderly women (aged ≥ 60) with abdominal obesity. The NCEP-ATP III modified for Asian Pacific Region was used to define the Mets. This study is a randomized, controlled trial which was conducted for 8 weeks. The treatment group received a weekly tailored nutritional program for 8 weeks (n = 21) and the control group received only one educational session (n = 18). In the treatment group, after the intervention, the serum levels of TGs and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were lower than their baseline value (P < 0.05. However, there was no significant difference in waist circumference, FPG, HDL-C, TG, and BP between the two groups before and after the intervention.[23]

The quality of cohort studies was assessed by Newcastle-Ottawa scale. The details of the quality assessment sections, including selection (representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the non-exposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure), comparability (comparability of cohorts on the basis of design or analysis), outcomes (assessment of outcome, adequacy of follow up of cohorts) were provided in Supplementary Table 2. The quality assessment of cross-sectional studies was fulfilled in three section, including selection (representativeness of the exposed sample, sample size, ascertainment of exposure, selection of the non-exposed sample), comparability (comparability of outcome groups on the basis of design or analysis), outcomes (assessment of outcome, suitability of statistical test) [Supplementary Table 1]. In cohort study, study score less than 4 indicates low quality, a score of 4–6 represents moderate quality, and a score of more than 6 is considered as a good quality. For cross-sectional studies, a score of 7 was considered as a good quality. The score of each study are presented separately in Table 1 and Table 2. The quality assessment of clinical trials was done using the Jadad scale and results are presented in Table 4. The various biases including, selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), selective outcome reporting, and other bias was assessed in included trials. Two studies were judged to be at high risk of bias. One study regarded as having low risk of bias. Risk of bias was unclear for the last one.

Supplementary Table 2.

Quality assessment using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies†

| Study | Selection | Comparability Comparability of Cohorts on the basis of design or analysis |

Outcome | Study score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of The exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at start of the study | Assessment of outcome | Was follow- up Long enough For the outcome to occur? | Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | |||

| Asghari, et al. 2016 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Pimenta et al. 2014 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

†Study score <4 indicates low quality, a score of 4 to 6 represents moderate, and a score of more than 6 indicates as a good quality

Supplementary Table 1.

Quality assessment using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for Cross-sectional studies*

| Study | Selection | Comparability Comparability of Outcome groups on the Basis of design or analysis |

Outcome | Study score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of The exposed sample | Sample size | Ascertainment of exposure | Selection of the non-exposed sample | Assessment of outcome | Suitability of statistical test | |||

| Ghorabi et al., 2019 | * | - | * | * | ** | * | * | 7/7 |

| Joyce et al., 2019 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7/7 |

| kang et al., 2018 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7/7 |

| Drehmer et al., 2017 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7/7 |

| Park et al., 2016 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | 7/7 |

| Saneei et al., 2015 | - | - | * | * | ** | * | * | 6/7 |

*We used a modified NOS scale for cross sectional studies. Note: A score of 7 was considered as good quality

Table 4.

Quality assessment of clinical trials according to the Jadad scale

| Random sequence generation (Selection Bias) | Allocation concealment (Selection Bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective outcome reporting | Other bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azadbakht, 2005 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Saneei, 2013 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hikmat, 2014 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Choi, 2015 |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Noted=Risk of bias level: low (green), unclear (yellow), high (red)

Discussion

The current systematic review support the hypothesis that a DASH diet that emphasizes on consuming higher amounts of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts; moderate intake of low-fat dairy; and low intake of red or processed meats and sweetened beverages can be an effective measure for reducing the risk of incident or progression of MetS. The benefits of the DASH diet were significant in most of observational studies. Also, in clinical trials, the beneficial role of DASH style diet in reducing some metabolic characteristics such as high BP and lipid profiles was shown. However, results for change in metabolic characteristics including waist circumference, FPG, HDL-C, TG based on dietary intervention with DASH diet in some interventional studies were not completely convincing.

Review of the findings of most observational studies indicated that there is a negative association between DASH diet and risk of MetS.[12,15,17,18] Studies on Korean adult population[12] and Iranian population[15,17] confirmed the beneficial effect of DASH diet regarding MetS and indicate the positive effect of this dietary pattern on metabolic health status. Also, in the Park et al. study, higher adherence to DASH diet score was associated with lower odds of unhealthy metabolic status in the younger group of men or women,[14] but no significant associations of DASH diet score with metabolic health were observed in the older participants (aged ≥45 years). In the Drehmer et al. study, there was no significant between higher adherence to the DASH diet and risk of MetS.[13] Furthermore, in US Hispanics/Latinos population, there was no associations between DASH diet and MetS prevalence.[22] An important point that should be noted in observational studies is that most of them had cross-sectional design. These studies cannot imply a causal relationship between this healthy dietary pattern and metabolic status. Also, some observed discrepancy in results of previous studies can be explained by difference in study design, sample size, adjustments for confounding factors, and approach which used to measure metabolic components and DASH diet score. Only two cohort studies (in the framework of the SUN and TLGS) have assessed the association of DASH diet with risk of MetS.[16,18] Study on Tehranian children and adolescents reported that greater adherence to DASH diet is associated negatively with risk of MetS and its components such as abdominal obesity, hypertension, and high FPG.[16] Also, the study on Spanish population indicated that high score of DASH diet is associated inversely with the risk of MetS among participants who had low alcohol intake.[18]

Some clinical trials have assessed the protective role of DASH style diet in reducing development of MetS and some of its components.[23,24,25,26] The clinical trial on Tehranian adults reported that high compliance to DASH diet can likely improve most of the metabolic indices, including HDL-C, lower TGs, SBP, weight, FBG among men and women.[26] Also, Saneei et al. reported a significant reduction in the prevalence of the MetS and hypertension in the DASH group.[25] Furthermore, the beneficial effect of high compliance to DASH styles diet on reducing BP and LDL-C have been reported,[23,24] however there is no significant effect of DASH diet intervention on metabolic indices including waist circumference, FPG, HDL-C, and TGs.[23,25] The results of previous clinical trials indicated that evidence on the possible protective effects of DASH style diet on several MetS components such as hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL-C, central obesity, and glucose intolerance are not entirely convincing.[23,24,25]

Over the past decade, different international organizations including the World Health Organization (WHO),[29] the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP),[30] the AHA/NHLBI,[31] the International Diabetes Federation (IDF),[32] and the Chinese Diabetes Society (CDS)[33] have presented several MetS definitions. Also, recently, IDF and AHA/NHLBI recommended a new Joint Interim Statement (JIS) to harmonize the definition of MetS.[1] Most of the studies included in the present review have assessed the presence of MetS using NCEP ATP III or the JIS (i.e., as the presence of any 3 of 5 risk factors of the following: waist circumference >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women, TGs >150 mg/dL, HDL <40 mg/dl in men and <50 mg/dl in women, BP >130/85 mmHg or antihypertensive medication use, fasting glucose >110 mg/dL). However, in the Kang et al. study,[12] MetS was defined using the Adult Treatment Panel III criteria, which were modified based on the Asia Pacific guidelines. Based on this guideline, abdominal obesity as a component of MetS was defined high WC as being >90 cm in men and >80 cm in women. Also, in the Asghari et al. study on adolescent participants, MetS was defined according to the joint interim statement as the presence of any 3 of 5 following factors: (1) abdominal obesity for women WC ≥91 cm and for men ≥89 cm, according to the cutoff point for Iranians; (2) FPG ≥100 mg/dl or drug treatment; (3) fasting TGs ≥150 mg/dl or drug treatment; (4) fasting HDL-C <50 mg/dl for women and <40 mg/dl for men or drug treatment; and (5) high BP was defined as SBP ≥130 mm Hg, DBP ≥85 mm Hg, or antihypertensive drug treatment. Although all the existing MetS definitions have been performed based on common characteristics including abdominal obesity, elevated TGs levels, decreased HDL-C levels, elevated BP levels and glucose intolerance; there are also some differences, especially regarding waist circumference cutoff. Therefore, the rigid comparison of result of studies which used different MetS definitions should be done cautiously.

Different methods of determination of the level of adherence to a specific dietary pattern, such as DASH diet are an important methodological issue in the nutritional epidemiology which deserves further consideration. There are several different approaches for the assessment of the adherence to DASH diet pattern; in particular, four different DASH diet scores have been created previously.[10,34,35,36] Some of them have been used for the evaluation of adherence to DASH diet by the studies included in the current study. Besides these differences, there are high similarities in scoring of DASH diet in most of these studies. Most of studies which included in the current review have determined DASH diet score using the Fung et al. study approach.[10] In these studies, seven foods and food groups including vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grain, low fat dairy, red and processed meat, and sweetened beverages were assessed by all scores. Other dietary components including sodium, sweet, fat/oil, total grains, and total dairy intake assessed by some of the scores. Other different in DASH diet scoring approach have been observed in regarding the number of the components used (from 8 to 9 components representing various food groups or items), the scoring system (number of partitions for each component, i.e., some scores have used a larger scaling, however others have used binary scores, which consequently, the total range of the scores of these studies to be very varied (0–9 to 8–80) [Table 5]. The present review revealed that one study has assessed the DASH score of study participants based on 9 different food components, including protein, fiber, magnesium, calcium, and potassium, total fat, saturated fat, sodium, and cholesterol using Mellen approach.[34] Also, a study on postmenopausal Korean women has used the modified DASH score, which was estimated using the DASH-Korean quartile model based on six nutrients (protein, fat, fiber, calcium, potassium, and sodium).[12] It is expected that the mentioned differences in the methodology used in the calculation of DASH diet scores may have effect on the significance of the associations and the effect size. Previously it has been reported that if researchers of nutrition fields use food components include large number of partitions (i.e., scoring classes for each consumption category) and the use of specific weights (related to the effect of each specific component with the evaluated outcome) for each index component; the accuracy of DASH diet scores is increased and, consequently the association of diet and diseases is evaluated appropriately. Of course, it should be noted that all of DASH score approaches have been used by these studies, are emphasizing to the inherent features of the DASH dietary pattern, which is rich in plant foods including whole grain, vegetables, fruits, legumes; consequently, this healthy dietary pattern lead to higher intakes of potassium, calcium, magnesium, fiber and lower intakes of cholesterol, sodium, and fat.

Table 5.

Methodological characteristics of the diet scores used to assessed the association of DASH with MetS

| Author | Year | Number of components | Scoring system | Range | Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asghari et al.[16] | 2016 | 8 | 5 partitions for each component | 8-40 | (+): whole grain, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, low-fat dairy products, (−): red and processed meat, sweetened beverages, and sodium |

| Joyce et al.[22] | 2019 | 8 | 10 partitions for each component | 0-80 | (+): grains, vegetables, fruit, dairy, and nuts/seeds/legumes, (−): red/processed meat, fats/oils, and sweets |

| Ghorabi et al.[17] | 2019 | 8 | 10 partitions for each component | 8-80 | (+): fruits, vegetables, nuts and legume, dairy products, grains, (−): sugar-sweetened beverages and sweets, sodium, and red and processed meats |

| Kang et al.[12] | 2018 | 6 | 4 partitions for each component | 6-24 | Protein, fat, fiber, calcium, potassium, and sodium |

| Drehmer et al.[13] | 2017 | 8 | 5 partitions for each component | 8-40 | (+): fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, (−): sodium, red and processed meats, and sweetened beverages |

| Park YM et al.[14] | 2017 | 9 | 0 and 1 points | 0-9 | Saturated fat, total fat, protein, cholesterol, fiber, magnesium, calcium, potassium, and sodium |

| Saneei et al.[15] | 2015 | 8 | 5 partitions for each component | 8-40 | (+): fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, low-fat dairy products, and whole grains, (−): sodium, sweetened beverages, and red and processed meats |

| Pimenta et al.[18] | 2015 | 8 | 5 partitions for each component | 8-40 | (+): whole grain, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, low-fat dairy products, (−): red and processed meat, sweetened beverages, and sodium |

(+)=Positive component; (−)=Negative component

The DASH diet may exert its role on risk of MetS through multiple biologic mechanisms.[27,28,37,38,39] The components of DASH diet including fruits, vegetables, legumes, dairy, whole grain, and nuts are rich in antioxidants such as vitamin C, fiber, potassium, magnesium, calcium, carotenoids, and flavonoids, which reduce insulin resistance, obesity, and MetS.[27] It is reported that high dietary fiber improves indices of metabolic abnormalities such as FPG, TGs, BP, and WC through reducing appetite, dietary energy density, and overall energy intake;[28] another suggested mechanism is the higher consumption of low fat dairy via the effects of calcium on insulin sensitivity, WC, BP, and lipid blood concentration.[37,38] Calcium is associated inversely with levels of above-mentioned cardio-metabolic factors through calcitrophic hormone regulation, conjugated with bile acids and elevated fecal fat excretion, intracellular calcium levels reduction, and affect metabolism of other electrolytes such as sodium. Also, consumption of more potassium-rich foods based on greater adherence to DASH diet and limiting sodium intake, has beneficial effects on BP level and reducing hypertension.[39,40]

The one of the strength of current study is the inclusion of all observational studies and clinical trials in this context. Also, two independent reviewers conducted comprehensive search on multiple databases, who aimed to identify all relevant articles. The robust methodology of this study enhances additional strength to the findings. However, some limitations of this review should be noted; the insufficient consistent evidences from trials made it difficult for us to make specific qualitative conclusions. Also, most of the included observational studies had cross-sectional nature, which limited us from establishing a cause and effect relation between DASH diet and MetS. Furthermore, studies used different dietary pattern scoring methods, and included participants who differed by various characteristics, such as age and sex. Therefore, the results of this study may cannot be generalized to public. A meta-analysis cannot be performed due to heterogeneity of included studies, limitation of the number of studies, and the use of various tools in these studies.

Conclusions

Most of observational and clinical studies have been published, confirmed the effective role of DASH diet in ameliorating risk of MetS incident or its progression. In fact, the results of the present systematic review indicated positive effect of greater adherence to DASH diet, characterized by the frequent consumption of whole grain, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, low-fat dairy products, and lower consumption of red and processed meat, sweetened beverages, and sodium, on decreasing risk of incident MetS and highlighting the its beneficial effect on human health. However, findings for beneficial effects of improved adherence to DASH dietary pattern on changes in some metabolic characteristics in interventional studies were not entirely convincing. Further interventional studies with long term follow up would be useful to clarify the possible beneficial effects of DASH diet on development of MetS.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project was funded by a grant NO. 1397/68987 from Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), Tehran, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study is related to the project NO. 1397/68987 From Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), Tehran, Iran. We also appreciate the Student Research Committee and Research & Technology Chancellor and Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences in SBMU for their financial support of this study.

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: A summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1769–78. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranasinghe P, Mathangasinghe Y, Jayawardena R, Hills AP, Misra A. Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome among adults in the asia-pacific region: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4041-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Neill S, O'Driscoll L. Metabolic syndrome: A closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev. 2015;16:1–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris M. The metabolic syndrome. Aust Family Phys. 2013;42:524–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Church T. Exercise in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;53:412–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassanabadi MS, Mirhosseini SJ, Mirzaei M, Namayandeh SM, Beiki O, Gannar F, et al. The most important predictors of metabolic syndrome persistence after 10-year follow-up: YHHP study. Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:33. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_215_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghobadi S, Rostami ZH, Marzijarani MS, Faghih S. Association of vitamin D status and metabolic syndrome components in iranian children. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:77. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_242_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Inter Med. 2008;168:713–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buse JB, Ginsberg HN, Bakris GL, Clark NG, Costa F, Eckel R, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2007;115:114–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang SH, Cho KH, Do JY. Association between the modified dietary approaches to stop hypertension and metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women without diabetes. Metab Syndr Relat Dis. 2018;16:282–9. doi: 10.1089/met.2018.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drehmer M, Odegaard AO, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Cardoso LD, Matos SM, et al. Brazilian dietary patterns and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet-relationship with metabolic syndrome and newly diagnosed diabetes in the ELSA-Brasil study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:13. doi: 10.1186/s13098-017-0211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park YM, Steck SE, Fung TT, Zhang J, Hazlett LJ, Han K, et al. Mediterranean diet, dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) style diet, and metabolic health in U.S. adults. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:1301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saneei P, Fallahi E, Barak F, Ghasemifard N, Keshteli AH, Yazdannik AR, et al. Adherence to the DASH diet and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among Iranian women. Eur J Nutr. 2015;54:421–8. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0723-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asghari G, Yuzbashian E, Mirmiran P, Hooshmand F, Najafi R, Azizi F. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) dietary pattern is associated with reduced incidence of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016;174:178–84.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghorabi S, Salari-Moghaddam A, Daneshzad E, Sadeghi O, Azadbakht L, Djafarian K. Association between the DASH diet and metabolic syndrome components in Iranian adults. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13:1699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pimenta AM, Toledo E, Rodriguez-Diez MC, Gea A, Lopez-Iracheta R, Shivappa N, et al. Dietary indexes, food patterns and incidence of metabolic syndrome in a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN project. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:508–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barak F, Falahi E, Keshteli AH, Yazdannik A, Esmaillzadeh A. Adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet in relation to obesity among Iranian female nurses. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:705–12. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014000822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farhadnejad H, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Dietary approach to stop hypertension diet and cardiovascular risk factors among 10- to 18-year-old individuals. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13:185–94. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liese AD, Bortsov A, Günther ALB, Dabelea D, Reynolds K, Standiford DA, et al. Association of DASH diet with cardiovascular risk factors in youth with diabetes mellitus: The search for diabetes in youth study. Circulation. 2011;123:1410–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.955922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joyce BT, Wu D, Hou L, Dai Q, Castaneda SF, Gallo LC, et al. DASH diet and prevalent metabolic syndrome in the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Prev Med Rep. 2019;15:100950. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SH, Choi-Kwon S. The effects of the DASH diet education program with omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on metabolic syndrome parameters in elderly women with abdominal obesity. Nutr Res Pract. 2015;9:150–7. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2015.9.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hikmat F, Appel LJ. Effects of the DASH diet on blood pressure in patients with and without metabolic syndrome: Results from the DASH trial. J Human Hypertens. 2014;28:170–5. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saneei P, Hashemipour M, Kelishadi R, Rajaei S, Esmaillzadeh A. Effects of recommendations to follow the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet v.usual dietary advice on childhood metabolic syndrome: A randomised cross-over clinical trial. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:2250–9. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi T, Azizi F. Beneficial effects of a dietary approaches to stop hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2823–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Most MM. Estimated phytochemical content of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet is higher than in the control study diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:1725–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papathanasopoulos A, Camilleri M. Dietary fiber supplements: Effects in obesity and metabolic syndrome and relationship to gastrointestinal functions. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(65):72.e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications.Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabetic Med. 1998;15:539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the national heart, lung, and blood institute/American heart association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--A new world-wide definition.A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabetic Med. 2006;23:469–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu YH, Lu JM, Wang SY, Li CL, Liu LS, Zheng RP, et al. [Comparison of the diagnostic criteria of metabolic syndrome by international diabetes federation and that by chinese medical association diabetes branch] Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;86:386–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellen PB, Gao SK, Vitolins MZ, Goff DC., Jr Deteriorating dietary habits among adults with hypertension: DASH dietary accordance, NHANES 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Arch Inter Med. 2008;168:308–14. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunther AL, Liese AD, Bell RA, Dabelea D, Lawrence JM, Rodriguez BL, et al. Association between the dietary approaches to hypertension diet and hypertension in youth with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2009;53:6–12. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon LB, Subar AF, Peters U, Weissfeld JL, Bresalier RS, Risch A, et al. Adherence to the USDA food guide, DASH eating plan, and mediterranean dietary pattern reduces risk of colorectal adenoma. J Nutr. 2007;137:2443–50. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dairy consumption is inversely associated with the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Tehranian adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:523–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Meijl LE, Vrolix R, Mensink RP. Dairy product consumption and the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res Rev. 2008;21:148–57. doi: 10.1017/S0954422408116997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akhlaghi M. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH): Potential mechanisms of action against risk factors of the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res Rev. 2019:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S0954422419000155. doi: 10.1017/S0954422419000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geleijnse JM, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE. Blood pressure response to changes in sodium and potassium intake: A metaregression analysis of randomised trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:471–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]