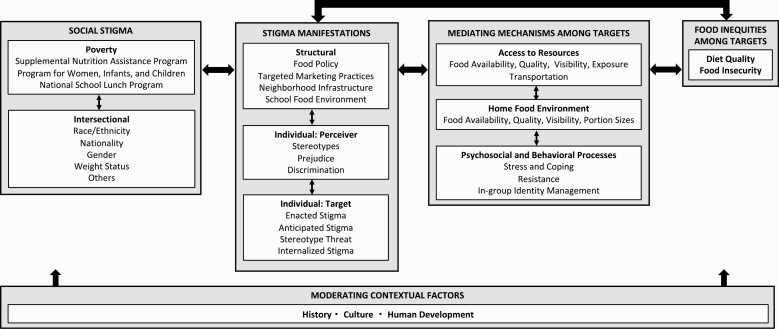

The Stigma and Food Inequity Framework describes how stigma associated with poverty, race, obesity and other characteristics impacts healthy food consumption, food insecurity, and diet quality.

Keywords: Discrimination, Food inequity, Stereotypes, Stigma

Abstract

There is increasing understanding that stigma associated with poverty, race, nationality, gender, obesity, and other intersecting, socially devalued characteristics is a key social determinant of health that plays a role in food inequities; yet, the processes linking stigma with food inequities are poorly defined. Building on prior conceptual and empirical stigma research in public health, this paper introduces The Stigma and Food Inequity Framework. Supporting empirical evidence for the associations proposed by the framework is reviewed. The framework proposes that stigma is manifested at the structural (e.g., neighborhood infrastructure and targeted marketing) and individual (e.g., internalized stigma and stereotypes) levels. These stigma manifestations are associated with food inequities via a series of mediating mechanisms, including access to resources, the home food environment, and psychosocial and behavioral processes, which ultimately undermine healthy food consumption, contribute to food insecurity, and impact diet quality. The framework further proposes that processes linking stigma with food inequities are situated within contexts of history, culture, and human development. Future directions to address stigma and enhance food equity include the value of addressing the broad range of underlying structural stigma manifestations when creating policy to promote food equity.

Implications.

Practice: In order to address food inequities, programs need to consider and address stigma at the structural and individual levels.

Policy: Policymakers must consider the broad range of underlying structural stigma manifestations when creating policy to promote food equity.

Research: Future research is needed to gain insight into the processes whereby stigma affects food inequities, including by testing hypothesized pathways within the Stigma and Food Inequity Framework, and identify strategies to address stigma to promote food equity.

Food inequities, including systematic differences in food accessibility and availability, shopping and purchasing, consumption, and diet quality, remain prevalent in the USA. As examples, households with residents with incomes 100% below the poverty line, with Black or Hispanic residents, and/or single heads of household experience higher rates of food insecurity than other households [1]. The importance of understanding and addressing upstream factors that generate and perpetuate food inequities is well recognized. To date, research and intervention efforts have centered on policy approaches [2–5] and the development of funding levers [6–8]. Yet, pronounced food inequities persist despite these efforts.

Stigma has been identified as a fundamental cause of population health inequities [9], but its role in food inequities remains understudied. Instead, much of the dialogue surrounding the role of stigma in food-related outcomes has centered on weight status stigma. Research demonstrates that overweight and obese individuals experience significant stigma associated with their weight status, which impacts healthy eating behaviors, perceived dietary control, exercise avoidance, and bias in health care settings [10–15]. Although some research has focused on other forms of stigma related to food (e.g., participation in food assistance programs) [16], the processes linking stigma with food inequities are currently poorly defined. Better understanding of how stigma ultimately impacts food inequities may improve our efforts to address food inequities. Building on prior conceptual and empirical stigma work in public health [9, 17, 18], the current paper: (a) introduces the Stigma and Food Inequity Conceptual Framework; (b) reviews supporting empirical evidence for the relationship between stigma and food inequities; and (c) identifies opportunities for research, intervention, and policy to address the role of stigma in food inequities.

The Stigma and Food Inequity Conceptual Framework

The Stigma and Food Inequity Conceptual Framework in Fig. 1 proposes processes whereby stigma leads to food inequities. The framework adapts previous theory and literature that identifies stigma as a social process, identifies manifestations of stigma at the structural and individual levels, defines mechanisms that mediate associations between stigma manifestations and health inequities, and describes factors that moderate stigma processes [9, 17–19]. The framework begins with social stigma, which is a social process that exists when labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination occur within a power context and results in some groups being socially devalued and discredited [19, 20] The framework highlights the role of stigma associated with poverty as a central driver of food inequities, which may be marked by participation in federal food programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or National School Lunch Program in the USA. The framework additionally recognizes that stigma associated with poverty may intersect with other stigmas, such as race, nationality, gender, obesity, and others. Therefore, it adopts an intersectionality lens, which acknowledges that systems of oppression (e.g., classism, racism, and sexism) are interlocking at the social and structural levels, and people experience stigma associated with multiple stigmatized characteristics simultaneously at the individual level (e.g., a Black woman living in poverty may experience stigma associated with her race, gender, and class simultaneously) [21, 22]. Thus, research to understand and interventions to address stigma and food inequities must take multiple stigmas into account. Although we primarily focus on stigma associated with poverty within this article, we also consider how other forms of stigma lead to food inequities.

Fig 1.

Stigma and Food Inequity Conceptual Framework.

Stigma manifestations

The social process of stigma is manifested, or expressed and experienced, at the structural and individual levels. Unlike social stigma itself, which is a social construct, stigma manifestations are typically observable, measurable, and intervenable. At the structural level, stigma is manifested within our policies, institutions, and built environments [23]. At the individual level, stigma is manifested among members of the general public but also among professionals, which may include regional planners, manufacturers, brand managers, and grocery store owners, as well as others involved in food production, marketing, and placement. These individuals, who may not be living with socially devalued characteristics themselves, are referred to as perceivers [24]. At the individual level, stigma is further manifested among people who are living with socially devalued characteristics, who are referred to as targets [24].

Structural level

Herein, we highlight four key, nonmutually exclusive structural manifestations of stigma that may play particularly prominent roles in food inequities, including policies related to food, the ways in which products are explicitly and implicitly marketed toward groups of people, the “brick and mortar” infrastructure of neighborhoods, and school food environments. Policies that result in limited food resources (e.g., single monthly distribution for SNAP, logistically challenging procedures for WIC enrollment, and others) and place children at high risk for hunger and food insecurity represent manifestations of structural stigma that often directly shape food insecurity [25, 26]. Individuals are exposed to targeted marketing practices within their built environments (e.g., signs on billboards and buses), school food environments (e.g., advertising on posters in school hallways), and online (e.g., social media marketing) [27–29]. These practices involve advertising products to specific groups based on lifestyle factors, purchasing habits, and related values and demographic characteristics [30]. One limiting practice in this regard is slotting fees, an important contributing mechanism toward what products are offered on grocery shelves [31]. Indeed the consumer nutrition environment, which encompasses the availability of healthful and less healthful food, the availability of well-placed and usable information consumers need to make healthy choices (i.e., food labels), the cost of food, including base pricing and discount pricing, as well as the implementation of taxes, and where products are placed on the shelf, is an important example of the kinds of structures where stigma manifestations may contribute to food inequities. In other contexts, research has documented differences in the ways that fast foods, including hamburgers, tacos, wraps, and soda, are advertised to African American youth as compared to White youth in commercials, as well as the interiors and exteriors of restaurants [32, 33].

Policies and targeted marketing practices unfold within and interact with other aspects of the built environments of neighborhoods and schools. From a traditional food perspective, the neighborhood infrastructure includes the types of retail food environments located near and within communities (i.e., supermarkets, corner stores, availability of supercenters like Walmart, and dollar stores), as well as the kinds of restaurants (e.g., fast food, take out, and sit down), and emergency food sites within communities. Research suggests that neighborhoods with more residents from stigmatized groups have limited access to healthy foods. For example, neighborhoods with more low-income and Black residents have more fast food restaurants [34] and fewer chain supermarkets [35] than those with more higher-income and White residents. The school food environment encompasses services and policies regarding nutrition, as well as the availability of food in schools, contributing to children’s and adolescents’ food consumption [36]. Evidence suggests that schools with less healthful food environments (e.g., menus are less likely to have been reviewed by nutritionists and healthful food is less available) are more commonly located in neighborhoods with greater social and material deprivation [36]. Other examples of stigma manifestations in the school food environment include stigma that may be associated with a subsidized meal and the mechanisms by which programs operate to mitigate structural inequities in the way that students participating in the program receive breakfast and lunch program food. In the case of the breakfast program, students qualifying for benefits may need to arrive before other students and consume their meals in a space only occupied by those receiving the benefit [37].

Food deserts are an important example of structural stigma that have received much empirical attention in recent years. They are the result of multiple forces, which together manifest in the lack of access to affordable nutritious food, typically in impoverished areas [38]. These forces include those related to the stigma manifestations reviewed above, as well as perceivers’ beliefs about the types of food that low-income families prefer, the ways in which neighborhoods and transportation systems are designed to enable or complicate access to healthy food, and how policies are enacted to support or limit the needed infrastructure and space for adequate healthy food resources to be developed locally. They also include the ways in which high rates of incarceration and inadequate opportunities for education (which are driven in part by pervasive racism) result in a limited workforce that drives retailers to site stores outside of the areas of greatest need. Food deserts shape individuals’ access to food, which, in turn, shapes how individuals construct their home food environment and the types of food individuals consume.

Individual-level: perceivers

Stigma among perceivers is manifested as prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination. These manifestations may be explicit, when individuals are aware of their own biases, or implicit, when individuals are unaware of their biases [39, 40]. They are driven, in part, by individualistic ideologies, including the Protestant Work Ethic (i.e., everyone has a chance to get ahead; therefore, poverty is a result of lack of hard work) and a belief in a just world (i.e., bad things, such as poverty, happen to bad people) [41]. Stereotypes are thoughts and beliefs held about groups that are applied to individuals, such as that people in poverty are lazy, unintelligent, and take advantage of the welfare system [41]. Food acts as a social marker and, thus, there is a wealth of stereotypes about what types of food groups of people prefer to eat [42]. These include that people from low-income backgrounds do not value fresh fruits and vegetables and African Americans prefer fried foods, such as fried chicken [43]. We hypothesize that stereotypes are one of the most important pathways through which social stigma leads to food inequities.

Prejudice involves negative emotions and feelings toward stigmatized individuals, such as discomfort with, and dislike of, people in poverty [44]. Discrimination includes unfair or unjust treatment of individuals, often driven by stereotypes and prejudice [44]. In the context of food inequity, discrimination encompasses a wide range of behaviors that ultimately undermine people’s access to healthy foods. Stereotypes may shape decisions about product, placement, promotion, and price (4Ps) resulting in discriminatory practices [29]. For example, beliefs that low-income people dislike fresh fruits and vegetables or prefer salty snacks or sugary beverages may lead store owners, in the case of smaller stores, or grocery retail buyers, in the case of larger stores, to stock fewer fresh items or lower-fat products in low-income communities and maximize grab-and-go snack placement and stock fewer diet or low-sugar beverages, ultimately perpetuating the disparities [45], which may have been the source of the stereotype in the first place. Stereotypes may additionally shape neighborhood infrastructure: beliefs about the frequency of theft may drive retailers’ decisions to not build supermarkets in low-income neighborhoods [46]. In these ways, stereotypes can drive market segmentation (product placement and advertising efforts) and planning/zoning policy and redlining that have important implications for neighborhood infrastructure.

Individual-level: targets

Stigma among targets is manifested as enacted stigma, anticipated stigma, stereotype threat, and internalized stigma. Enacted stigma includes perceptions of prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination from others in the past or present [17]. Enacted stigma is a stressor among people living with a range of stigmatized identities, behaviors, and characteristics. Anticipated stigma includes expecting to experience prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination from others in the future [17]. Anticipated stigma may lead individuals to engage in behaviors to conceal stigmatized characteristics, such as poverty. For example, some youth refuse subsidized school lunches, which are supposed to be nutritionally balanced, and instead eat low-cost foods, such as chips or French fries because they do not want their peers to know that they are eligible for school lunch programs [16]. Stereotype threat includes perceiving that one is at risk of confirming a stereotype about one’s group [47] and can result in stereotype-confirming behavior by depleting cognitive resources. As an example, overweight individuals exposed to a stereotype threat manipulation (e.g., that overweight people eat more unhealthy foods) ordered more calorie-dense foods in a recent study [48]. Internalized stigma includes the awareness and endorsement of negative beliefs and feelings about one’s group and the application of these beliefs and feelings to the self [17]. Internalized stigma is associated with a suite of negative behavioral, mental, and physical health outcomes, including more frequent binge eating among overweight and obese women [49].

Mediating mechanisms

Stigma manifestations lead to food inequities through a series of mediating mechanisms experienced and enacted by targets of stigma [9, 50] that undermine healthy food consumption, contribute to food insecurity, and ultimately impact diet quality. These include individual targets’ access to resources, the construction of the home food environment, and psychological processes in response to stigma.

Access to resources

Structural stigma manifestations, including the neighborhood infrastructure and school food environment, fundamentally shape individual targets’ access to healthy food. The availability and visibility of healthy and quality foods (i.e., those low in salt, sugar, and fat) within neighborhood environments ultimately shape what foods individual targets can access, purchase, and consume [2, 29, 51, 52]. Targeted marketing practices shape individuals’ exposure to different types of foods, which influences purchasing and consumption decisions [53]. Neighborhood infrastructure additionally shapes transportation options available to individuals, which are key for facilitating access to supermarkets, farmers’ markets, and other sources of quality foods [54]. Individuals in low-income households are less likely to both live in neighborhoods with supermarkets and to own cars [55, 56]. Therefore, they are more reliant on public transportation to access food.

Household food environment

Household food environments are influenced by individuals’ access to food, driven in part by the options presented by local food retailers, transportation options, desire for foods, and one’s own personal experiences of stigma manifestations, which contribute to preferences. For example, overweight individuals experiencing stereotype threat at a grocery store may purchase and bring home more calorie-dense foods. The household food environment is characterized by both the availability and quality of products in the home, as well as their visibility or placement on table tops or in cabinets and refrigerators, portion sizes, and the likelihood to consume food alone or with others.

Psychosocial and behavioral processes

Psychosocial processes represent ways that individual targets respond to stigma, which ultimately shape their food selection, purchasing, and consumption behaviors. Enacted and anticipated stigma are characterized as significant stressors [9], and individuals may cope with these stressors through unhealthy eating behaviors (e.g., disordered eating patterns, overconsumption, and consumption of unhealthy foods). Indeed, evidence suggests that experiences of both weight and race enacted stigma are associated with increased food consumption, particularly calorie-dense and fast foods [57, 58]. Additionally, purchasing and consuming certain foods may serve as a form of resistance. Similar to purchasing and wearing branded clothing [59], purchasing and consuming branded foods, such as Coca Cola or Doritos, may be a way for individuals to resist being labeled as poor and achieve inclusion and status within their social groups. Similarly, food is a powerful way to express and manage in-group identity. Individuals may internalize mental models, or understandings, regarding the types of foods that their group eats versus does not eat [60]. These mental models may promote eating unhealthy foods and avoiding healthy foods as a way to establish and preserve in-group identity.

Moderating contextual factors

The Stigma and Food Inequity Conceptual Framework proposes that the processes linking stigma with food inequities unfold within a context of history, culture, and human development. These contextual factors moderate the process linking social stigma with food inequities and affect how stigma is manifested, as well as the strengths of associations between stigma manifestations and food inequities.

History

History is the most important contextual driver of food inequities. Of particular concern are historical events that are themselves rooted in stigma and continue to impact people today. Examples include slavery, the forced relocation of Native Americans, and mortgage redlining in the USA. These historical events have shaped the environments in which people live (including their neighborhood infrastructure and home food environments), led to the loss of plant-based cultural and food traditions, resulted in historical trauma (i.e., psychological distress stemming from historic traumatic events [61]), and led to epigenetic transformations that impact health disparities. Teasing apart the legacy of slavery on inequities in food is not well studied; however, there is increasing recognition that slavery’s impact on the transmission of cultural values, human and economic capital, social and political power, and intergenerational trauma have left enduring effects, which are captured in part by geographic boundaries and which account for differential disease outcomes closely tied to diet [62].

Culture

Stigma processes are dependent on culture. That is, the extent to which characteristics are socially devalued, the ways in which stigma is manifested, and the outcomes of stigma on food inequities vary between different cultural contexts. For example, evidence suggests that prejudice toward overweight people is stronger in the USA than Mexico [63]. This difference appears to be driven, in part, by stronger attributions of controllability of weight status in the USA than in Mexico. Yang et al. additionally theorize that stigma undermines individuals’ capacity to participate in “what matters most” within a cultural context, thereby preventing individuals from achieving full status within their cultural group [25].

Human development

Another important context for our understanding of stigma on food is the role of lifespan development from early childhood through adulthood. Individuals’ physical and social needs change across the lifespan and, borne from these needs, they become more or less susceptible to the effects of stigma. Thus, exposure to stigma at some developmental periods may have a particularly strong impact on food inequities [64]. As examples, children may be particularly susceptible to the influences of targeted junk food marketing, an issue of great relevance today given children’s frequent use of YouTube, which does not require the separation of advertising from programming. Concurrently, adolescents may experience more stress as a result of stigmatizing experiences than adults, leading to greater coping through disordered eating patterns. Moreover, the effects of stigma may be intergenerationally transmitted through linked lives [64] as when mothers’ diets and breast-feeding habits affect the health and eating habits of their growing children [25, 26].

Future Directions to Address Stigma and Enhance Food Equity

Researchers, public health practitioners, clinicians, policymakers, and other stakeholders have important roles to play in addressing stigma to enhance food equity. Below, we identify possible future directions for research, as well as translational implications for intervention and policy to achieve these goals.

Research directions

There are numerous research questions that can be asked to gain insight into the processes whereby stigma affects food inequities and what can be done to address these processes. As a first step, our framework calls for the recognition that stigma is a likely driver of disparity and, as such, should be investigated alongside other more common metrics. Studies of interventions that seek to influence dietary quality traditionally examine impacts in terms of purchasing and consumption and may incorporate mediating mechanisms like food access. The present framework, however, calls for research to look more closely at the mechanisms by which stigma manifests itself to not only account for its role but also to better understand how and when it influences behaviors. Importantly, the framework identifies stigma manifestations and possible mediating mechanisms linking these stigma manifestations with outcomes. Yet, research examining many of the proposed processes linking stigma manifestations with food inequities is lacking. Evidence is needed to determine the extent to and ways in which stigma manifestations ultimately impact food inequities.

In a similar vein, the Stigma and Food Inequity Framework hypothesizes that stereotypes play important roles in food advertisement and product placement by perceivers and that stereotype threat is an important mechanism by which targets may make product selection decisions. Research questions that investigate, for example, how stigma plays a role in the selection of what items are marketed and how in supermarkets, such as the role of stigma in how placement decisions are made, for example, would considerably advance the public health understanding of how to improve food environments and effectively address inequities. To date, there is no research with which we are familiar that specifically considers the role that stigma plays in corporate decision-making at the manufacturer and retailer levels about product availability, display, marketing campaigns, and store stock on grocery shelves, as well as for prepared food. While it is well recognized that there is a lack of diversity among the highest level of food retail operations, little has been systematically studied about how and in what ways stigma contributes to food inequities. Future research could test these and other hypotheses and should consider measuring the extent to which individuals experience stigma manifestations as part of studies that seek to understand or impact dietary behavior.

The Stigma and Food Inequity Framework additionally points to several methodological approaches that may be particularly well suited to study the role of stigma in food inequities. The framework is multilevel, including manifestations at the structural and individual levels, as well as mediating mechanisms within neighborhoods, households, and individuals. Thus, it may be important for research on food and health inequities to incorporate multilevel methods and analyses to build a comprehensive understanding of how stigma impacts food inequities. The framework hypothesizes that stigma manifestations impact food inequities via a suite of mediating mechanisms. Longitudinal methods may be needed to test these causal associations over time. Contextual factors included in the framework are conceptualized as moderators of the process linking stigma with food inequities. Research that explores these processes across time, cultural contexts, and stages of human development may provide insight into circumstances wherein stigma has a stronger, or weaker, impact on food inequities. The framework additionally highlights that stigma associated with multiple socially devalued characteristics, including poverty, race/ethnicity, nationality, gender, obesity, and others, may play roles in food inequities. Future studies should consider adopting an intersectional lens that accounts for the roles of multiple stigmas and follow recent recommendations for intersectional stigma research [65, 66]. Food researchers should also consider incorporating measures of stigma manifestations (see [67–69] for recommendations for stigma measurement) and can develop new public health interventions that go beyond education and begin to provide new ways that practitioners and institutions can become awakened to the various ways that stigma impacts dietary decisions. Furthermore, policymakers in the context of a “health in all” framework should be educated on and recognize the ways in which stigma manifests food inequities, as well as opportunities in policy decision-making and communication efforts that can minimize stigma and improve outcomes.

Translational implications

In addition to guiding research questions, the Stigma and Food Inequities Framework has the potential to inform future intervention efforts to address social stigma and reduce food inequities. Stigma is a social determinant of health. The framework emphasizes that stigma manifested at multiple social-ecological levels ultimately impacts food inequities. We, therefore, echo calls from recent stigma theorists for interventions that address stigma at multiple social-ecological levels, including among targets, perceivers, and within structures [70, 71]. The framework further suggests that stigma associated with multiple socially devalued characteristics affects food inequities. It is, therefore, important to adopt cross-cutting approaches that seek to address stigma associated with multiple socially devalued characteristics simultaneously. Addressing classism, without addressing racism, will likely not end food inequities. The framework also identifies multiple opportunities for intervention. As examples, interventions may aim to reduce stigma manifestations directly, disrupt associations between stigma manifestations and food inequities by addressing mediating mechanisms, or bolster resilience to stigma by attending to contextual factors. Above all, it is critical that practitioners recognize what institutions can do, rather than targets, to recognize that individual responsibility and will-power narratives perpetuate self-blame and the devaluing of individuals and their experiences.

Stigma researchers have yet to uncover a single “silver bullet” intervention strategy to end social stigma. Rather, they are accumulating a toolbox of strategies that have demonstrated efficacy in various domains (e.g., mental health and HIV) and can be applied to food inequities. At the structural level, mass media campaigns have shown promise in changing public attitudes toward members of stigmatized groups within countries [72, 73], and cultural competence trainings communicate diversity values within organizations [70]. For perceivers at the individual level, these include educational interventions to address stereotypes, intergroup contact interventions to humanize members of stigmatized populations and reduce implicit and explicit prejudice, and cognitive dissonance interventions that lead perceivers to confront inconsistencies between their beliefs (e.g., negative views about a group) and values (e.g., egalitarianism) [70]. For targets, these include values affirmation interventions to reduce stereotype threat and restore self-integrity, expressive writing to strengthen coping with enacted and/or anticipated stigma, education and counseling to promote healthy decision-making, and social support and belongingness interventions to counter social exclusion [70]. Researchers might test the feasibility of implementing these stigma-reduction tools within existing interventions (e.g., retail food environment, community nutrition, and home food environment interventions).

Changing policy is a powerful way to reduce and prevent stigma from impacting food inequities. As examples, the Healthy Hunger Free Kids Act, which addressed the quality of foods available in schools and sought to improve the in-school marketing environments, worked to shift norms and expectations for all children and fostered the acceptance of whole grains and lower-sodium and lower-sugar foods and beverages. At the same time, however, inequities in facilities continue to prohibit equal access to working kitchens, and revenue differences between schools with a large student self-pay versus those exclusively reliant on federal reimbursement have limited the policy’s full potential to achieve equity [74]. In addition to addressing school food and the layered systematic inequities inherent therein are broader policy issues related to the establishment of community food systems in the context of a global food economy, including efforts to promote local land ownership and local business development. Food marketing too is an area well suited for policy intervention in order to foster equity. Established in 2007, the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative is an industry self-regulation initiative that seeks to improve the advertising mix of foods marketed to children under 12 in order to improve dietary choices [75]; however, recent reports suggest that racially and ethnically targeted marketing of unhealthy foods, which may be driven in part by stereotypes, persists [76]. More specific recommendations that would limit the marketing of unhealthy foods specifically targeted to racial or ethnic minority children is an example of how policy can address stigma [76].

Conclusion

Stigma is a key social determinant of health that plays a role in food inequities. Yet, research on the role of stigma in food inequities and interventions to address stigma to reduce food inequities have been limited to date. We have introduced the Stigma and Food Inequities Framework to identify stigma mechanisms at the structural and individual levels, describe key mediating mechanisms through which stigma mechanisms impact food inequities, and highlight contextual factors that may shape the process linking stigma with food inequities. We have also suggested future directions in research, intervention, and policy based on this Framework. Collaborations across the food system are needed to address stigma at the structural and individual levels to promote food equity.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DK102324 and an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number U54-GM104941.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. 2018. Statistical supplement to household food security in the United States in 2017. AP-079. Available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90028. Date accessed 15 May 2020.

- 2. Foster GD, Karpyn A, Wojtanowski AC, et al. Placement and promotion strategies to increase sales of healthier products in supermarkets in low-income, ethnically diverse neighborhoods: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1359–1368. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.075572.Efforts. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karpyn A, DeWeese RS, Pelletier JE, et al. Examining the feasibility of healthy minimum stocking standards for small food stores. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(9):1655–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DeWeese RS, Todd M, Karpyn A, et al. Healthy store programs and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), but not the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), are associated with corner store healthfulness. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davis EL, Wojtanowski AC, Weiss S, Foster GD, Karpyn A, Glanz K. Employee and customer reactions to a healthy in-store marketing intervention in supermarkets. J Food Res. 2016;5(1):107–113. doi: 10.5539/jfr.v5n1p107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karpyn A, Young C, Weiss S. Reestablishing healthy food retail: Changing the landscape of food deserts. Child Obes. 2012;8(1):28–30. doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karpyn BA, Manon M, Treuhaft S, Giang T, Harries C, Mccoubrey K. Policy solutions to the “Grocery Gap.” Heatlh Aff (Milwood). 2010;29(3):473–480. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harries C, Koprak J, Young C, Weiss S, Parker KM, Karpyn A. Moving from policy to implementation: A methodology and lessons learned to determine eligibility for healthy food financing projects. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(5):498–505. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1019–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Major B, Hunger JM, Bunyan DP, Miller CT. The ironic effects of weight stigma. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2014;51:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vartanian LR, Porter AM. Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite. 2016;102:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vartanian LR, Shaprow JG. Effects of weight stigma on exercise motivation and behavior: A preliminary investigation. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(1):131–138. doi. 10.1177/1359105307084318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chou WY, Prestin A, Kunath S. Obesity in social media: A mixed methods analysis. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4(3):314–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phelan SM, Dovidio JF, Puhl RM, et al. Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: The medical student CHANGES study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(4):1201–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu B, Lim H, Kelly S. Does receiving a school free lunch lead to a stigma effect? Evidence from a longitudinal analysis in South Korea. Soc Psychol Educ. 2019;22(2):291–319. doi: 10.1007/s11218-019-09485-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: Moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. doi. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (1st Touchstone). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosenthal L. Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. Am Psychol. 2016;71(6):474–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43:1241–1299. doi. 10.2307/1229039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hatzenbuehler ML, Link BG. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bos AER, Pryor JB, Reeder GD, Stutterheim SE. Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;35(1):1–9. doi. 10.1080/01973533.2012.746147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang Z, Huffman SL. Nutrition in pregnancy and early childhood and associations with obesity in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(suppl 1):105–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pauwels S, Symons L, Vanautgaerden E, et al. The influence of the duration of breastfeeding on the infant’s metabolic epigenome. Nutrients. 2019;11(1408):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harris JL, Shehan C, Gross R. 2015. Food advertising targeted to Hispanic and Black youth: Contributing to health disparities. Available at http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/272-7%20%20Rudd_Targeted%20Marketing%20Report_Release_081115%5B1%5D.pdf">http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/272-7%20%20Rudd_Targeted%20Marketing%20Report_Release_081115%5B1%5D.pdf. Date accessed 15 May 2020.

- 28. Velazquez CE, Black JL. Food and beverage marketing in schools: A review of the evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(1054):1–15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14091054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glanz K, Bader MD, Iyer S. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: An integrative review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grier S, Bryant CA. Social marketing in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:319–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rivlin G. Rigged: Supermarket Shelves for Sale. Washington, DC: Center for Science in the Public Interest; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gilmore JS, Jordan, A. Burgers and basketball: Race and stereotypes in food and beverage advertising aimed at children in the US. J Child Media. 2012;6(3):317–332. doi. 10.1080/17482798.2012.673498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ohri-Vachaspati P, Isgor Z, Rimkus L, Powell LM, Barker DC, Chaloupka FJ. Child-directed marketing inside and on the exterior of fast food restaurants. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Block JP, Scribner RA, DeSalvo KB. Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Powell LM, Slater S, Mirtcheva D, Bao Y, Chaloupka FJ. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fitzpatrick C, Datta GD, Henderson M, Gray-Donald K, Kestens Y, Barnett TA. School food environments associated with adiposity in Canadian children. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017;41(7):1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leos-Urbel J, Schwartz AE, Weinstein M, Corcoran S. Not just for poor kids: The impact of universal free school breakfast on meal participation and student outcomes. Econ Educ Rev. 2013;36:88–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karpyn AE, Riser D, Tracy T, Wang R, Shen YE. The changing landscape of food deserts. UNSCN Nutr. 2019;44:46–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, Shelton JN. Disparities and distrust: The implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dovidio J, Gaertner S. Aversive racism. In: Zanna MP, ed. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 36. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2004:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cozzarelli C, Wilkinson AV, Tagler MJ. Attitudes toward the poor and attributions for poverty. J Soc Issues. 2001;57(2):207–227. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garine I. Views about food prejudice and stereotypes. Anthropol Food. 2001;40(3):487–507. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Golan E, Stewart H, Kuchler F, Dong D. Can low-income Americans afford a healthy diet? Amber Waves, 2008;6(5):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brewer, M. B. (2007). The social psychology of intergroup relations: Social categorization, ingroup bias, and outgroup prejudice. In: Kruglanski AW, eds. Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mendez MA, Miles DR, Poti JM, Sotres-Alvarez D, Popkin BM. Persistent disparities over time in the distribution of sugar-sweetened beverage intake among children in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(1):79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bowes DR A two-stage model of the simultaneous relationship between retail development and crime. Econ Devel Quart. 2007;21(1):79–90. doi: 10.1177/0891242406292465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brochu PM, Dovidio JF. Would you like fries (380 calories) with that? Menu labeling mitigates the impact of weight-based stereotype threat on food choice. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2014;5(4):414–421. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Puhl RM, Moss-racusin CA, Schwartz MB, Rebecca M. Internalization of weight bias : Implications for binge eating and emotional well-being. Obesity. 2007;15(1):19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chaudoir SR, Earnshaw VA, Andel S. “Discredited” versus “eiscreditable”: Understanding how shared and unique stigma mechanisms affect psychological and physical health disparities. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;35(1):75–87. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.746612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jilcott SB, Keyserling T, Crawford T, Guirt JTMC, Ammerman AS. Examining associations among obesity and per capita farmers’ markets, grocery stores/supermarkets, and supercenters in US counties. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(4):567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bragg MA, Roberto CA, Harris JL, Brownell KD, Elbel B. Marketing food and beverages to youth through sports. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(1):5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vallianatos M, Shaffer A, Gottlieb R. (2002) Transportation and food: The importance of access. Center for Food and Justice, Urban and Environmental Policy Institute policy brief. Available at http://eatbettermovemore.org/sa/pdf/transportation_and_food.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2019.

- 55. Rhone A, Ver Ploeg M, Dicken C, Williams R, Breneman V. Low-Income and Low-Supermarket-Access Census Tracts, 2010–2015. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 56. McCann B. 2006. Community design for healthy eating: How land use and transportation solutions can help. Available at http://www.slideshare.net/GeoAnitia/community-design-for-healthy-eating-how-land-use-and-transportation-solutions-can-help. Date accessed 15 May 2020.

- 57. Puhl R, Suh Y. Health consequences of weight stigma: Implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(2):182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cozier YC, Wise LA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Perceived racism in relation to weight change in the Black women’s health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(6):379–387. doi. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Elliott R, Leonard C. Peer pressure and poverty: Exploring fashion brands and consumption symbolism among children of the “British poor.” J Consum Behav. 2004;3(4):347–359. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Satia JA. Diet-related disparities: Understanding the problem and accelerating solutions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(4):610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Whitbeck LB, Adams GW, Hoyt DR, Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(3–4):119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kramer MR, Black NC, Matthews SA, James SA. The legacy of slavery and contemporary declines in heart disease mortality in the U.S. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Crandall CS, Martinez R. Culture, ideology, and antifat attitudes. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1996;22(11):1165–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Brondolo E. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma and health. In: Major B, Link BG, Dovidio JF, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bastos JL, Celeste RK, Faerstein E, Barros AJ. Racial discrimination and health: A systematic review of scales with a focus on their psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):1091–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fox AB, Earnshaw VA, Taverna EC, Vogt D. Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: The Mental Illness Stigma Framework and critical review of measures. Stigma Health. 2018;3(4):348–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, Busch JTA. Intervening within and across levels: A multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rao D, Elshafei A, Nguyen M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Frey S, Go VF. A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: State of the science and future directions. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Evans-Lacko S, Corker E, Williams P, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Effect of the Time to Change anti-stigma campaign on trends in mental-illness-related public stigma among the English population in 2003-13: An analysis of survey data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(2):121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination in mental illness: Time to Change. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1928–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Giancatarino A, Noor S. 2014. Building the case for racial equity in the food system. Available at https://www.centerforsocialinclusion.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Building-the-Case-for-Racial-Equity-in-the-Food-System-1.pdf. Date accessed 15 May 2020.

- 75. BBB National Programs. 2019. Children’s food and beverage advertising initiative. Available at https://bbbprograms.org/programs/all-programs/cfbai. Date accessed 4 September 2020.

- 76. Harris JL, Frazier W, Kumanyika S, Ramirez AG. 2019. Increasing disparities in unhealthy food advertising targeted to Hispanic and Black youth. Available at http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/TargetedMarketingReport2019.pdf. Date accessed 15 May 2020.