Abstract

Regulatory jurisdictions worldwide are increasingly incorporating bioavailability-based toxicity models into development of protective values (PVALs) for freshwater and saltwater aquatic life (e.g., water quality criteria, standards, and/or guidelines) for metals. Use of such models for regulatory purposes should be contingent on their ability to meet performance criteria as specified through a model-validation process. Model validation generally involves an assessment of a model’s appropriateness, relevance, and accuracy. We review existing guidance for validation of bioavailability-based toxicity models, recommend questions that should be addressed in model-validation studies, discuss model study type and design considerations, present several new ways to evaluate model performance in validation studies, and suggest a framework for use of model validation in PVAL development. We conclude that model validation should be rigorous but flexible enough to fit the user’s purpose. Although a model can never be fully validated to a level of zero uncertainty, it can be sufficiently validated to fit a specific purpose. Therefore, support (or lack of support) for a model should be presented in such a way that users can choose their own level of acceptability. We recommend that models be validated using experimental designs and endpoints consistent with the data sets that were used to parameterize and calibrate the model and validated across a broad range of geographically and ecologically relevant water types.

Keywords: Biotic ligand model, Metal bioavailability, Metal toxicity, Validation, Model performance, Water chemistry

INTRODUCTION

Bioavailability-based toxicity models (referred to as “models” herein) are currently being used or considered in many regulatory jurisdictions worldwide to incorporate the “state of the science” of metal speciation, metal bioavailability, and metal ecotoxicity into the development of protective values for aquatic life (PVALs) for metals (European Commission 2000, 2013; US Environmental Protection Agency 2007). Herein, we use “PVAL” when referring in general to water quality criteria, standards, guidelines, benchmarks, and so on that are developed by regulatory authorities to maintain acceptable concentrations of chemicals in water bodies; but we do not use that term to refer to specific documents published by governmental authorities. Use of this more general term is appropriate because of the many different regulatory terms used worldwide. However, when we refer to a specific jurisdictional document or set of documents, we capitalize the appropriate term (e.g., recommended Water Quality Criteria, Guidance, Guidelines, etc.). In a separate context, we use the word “criteria” to refer to a basis for making a decision about model performance (e.g., “acceptance criteria,”“performance criteria”) and the word “standard” as an adjective, but in those uses “criteria” and “standard” are not capitalized.

Before application in a regulatory framework, a model should be shown to be valid (e.g., appropriate, relevant, and accurate) for predicting bioavailability relationships that occur in the environment. Appropriateness and relevance of a model can be assessed by 1) critically reviewing the need for including effects of various toxicity-modifying factors (TMFs), and 2) understanding the way in which the effects of TMFs are characterized or described. Model accuracy can be evaluated by assessing the performance of the model when compared to laboratory or field observations. A structured model-validation process should incorporate these considerations.

For many metals, the effects of abiotic factors on toxicity have been investigated and quantified, leading to the development of models ranging in complexity from empirical models (e.g., simple linear regressions) to more mechanistic speciation and toxicity models (Adams et al. 2020). For example, the well-known family of biotic ligand models (BLMs) can be considered empirical toxicity models that contain underlying, mechanistic chemical-speciation elements.

Models are sometimes employed to normalize toxicity data sets from different source waters to a common condition. This normalization process, which is oftentimes referred to as “bioavailability correction,” usually decreases intraspecies variability among various data sets by, in some cases, several orders of magnitude (Schlekat et al. 2010). Incorporation of bioavailability corrections is a crucial step in PVAL derivation because the toxicity and bioavailability of many metals to aquatic organisms are driven by the prevailing water chemistry conditions (Meyer et al. 2007b, 2012). Before being used in a regulatory setting, a model must be accurate in predicting toxicity to the species for which it was developed and in predicting toxicity to other taxa that will be used to calculate PVALs and for which no model has been developed (e.g., cross-species extrapolation).

Bioavailability-based models have been developed for a growing number of metals (Al, Ag, Cd, Co, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb, Zn; Adams et al. 2020) and have undergone varying degrees of validation. The types of validation studies range from autovalidation to independent validation, including cross-species and cross-endpoint extrapolation. Bioavailability-based models might also include data from laboratory studies in natural or synthetic waters and, in some cases, field-based studies. In the context of the present study, “autovalidation” is the use of the same toxicity data set to both parameterize/calibrate a model and then test for accuracy of the model’s predictions (i.e., only demonstrating internal consistency). In contrast, “independent validation” is the use of different toxicity data sets to parameterize/calibrate a model to test for accuracy of the model’s predictions. In cross-species and cross-endpoint validation, it is assumed that the parameters which describe interactions between the TMF and the metal are constant across organisms, and the model structure (e.g., the set of binding constants in a BLM or the set of coefficients of the predictor variables in a multiple regression model [MRM]) is independently parameterized for one species or endpoint (using its own toxicity data set) and then applied to a data set for another species or endpoint (Van Sprang et al. 2009; Schlekat et al. 2010). In this situation, only the parameter describing the intrinsic sensitivity of the species and endpoint to which the model is applied (e.g., the short-term accumulation at the biotic ligand that is predictive of 50% mortality at a later time in a BLM or the regression constant in an MRM) are changed to fit the data set for the other species and/or endpoint. This approach is supported if empirical data show that the available models can predict toxicity for taxonomically dissimilar species (e.g., 3 or more taxonomic groups) and can be used to normalize full ecotoxicity databases to consistent water chemistry conditions to reduce intraspecies variability (Van Sprang et al. 2009; Schlekat et al. 2010).

The incorporation of bioavailability-based models into the derivation of PVALs requires robust and scientifically defensible model validation. However, little has been published on validation of ecotoxicity models, and that guidance is of limited depth (e.g., Janssen and Heuberger 1995; section 10.6.2 in European Food Safety Authority 2014). The present study reports the outcome of the model validation workgroup during the 2017 Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) technical workshop Bioavailability-Based Aquatic Toxicity Models for Metals (Adams et al. 2020), in which a variety of validation-related topics were addressed: existing guidance for validation of bioavailability-based models for metals, questions that should be addressed in a model-validation study, model-validation study types and design considerations, evaluation of model performance, and practical considerations for uses of model validation.

The approach described herein for model validation is general and thus is applicable both to freshwater and saltwater systems because it is incumbent on the user to decide the extent of validation and level of performance appropriate for various models and waters of interest. A prescriptive approach would be inappropriate because it is difficult to anticipate all types and possible applications of models. In addition, a prescriptive approach presumes that models developed in the future would be characterizing a specified set of biological responses with a given set of potential predictors (e.g., water chemistry characteristics). Our more general approach requires that potential users understand the models being evaluated, the biological endpoints the model can predict, and the species and waters of interest to which the models will be applied. With this understanding, a user should be able to design a credible validation approach that can determine if the model(s) under consideration is well suited to the application.

EXISTING GUIDANCE FOR VALIDATION OF BIOAVAILABILITY MODELS

Technical guidance documents for many regulatory jurisdictions recognize the need to incorporate metal bioavailability into the development of PVALs (Table 1). For example, the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (USEPA’s) 1985 Guidelines for Deriving Numerical National Water Quality Criteria for the Protection of Aquatic Organisms and Their Uses recognized a relationship between water hardness and acute toxicity of metals and stated that when sufficient data are available to demonstrate that toxicity is related to a water quality characteristic, the relationship should be considered using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA; Stephan et al. 1985). As a consequence, the USEPA’s recommended Water Quality Criteria for several metals (e.g., Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn) in the 1980s and 1990s were based on regression equations relating the logarithm of a median lethal concentration (LC50)/median effect concentration (EC50) value to the logarithm of the hardness of the exposure water, and ANCOVA was used to test whether the same model was applicable across all species (i.e., whether the regression slopes did not differ significantly among species). These were the first applications of bioavailability-based models in PVAL development, but the USEPA’s hardness-based models were not independently validated before being incorporated into the 1980s/1990s Water Quality Criteria.

TABLE 1:

Validation processes for metal bioavailability models recently adopted or pending adoption in protective values for aquatic lifea

| Metal | Jurisdiction | Regulatory application (regulatory authority and year) | Bioavailability model | Validation process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | USA | USEPA 2018 | MRM (chronic, applied to acute) | Autovalidation (DeForest et al. 2018; US Environmental Protection Agency 2018) |

| Cd | EU | WFD 2000 | Hardness adjustment (acute and chronic) | Autovalidation (Mebane 2010) |

| USA | USEPA 2016 | Hardness adjustment (acute and chronic) | Autovalidation (US Environmental Protection Agency 2016a) | |

| Co | EU | REACH 2006 | BLM (chronic) | Cross-species validation (Oregon State University Aquatic Toxicology Laboratory 2017a-2017e) |

| Cu | USA | USEPA 2007 | BLM (acute, applied to chronic with ACR) | Autovalidation (US Environmental Protection Agency 2003) |

| Australia and New Zealand | ANZG 2019 | DOC adjustment (chronic) | Cross-species validation (Australian and New Zealand Governments 2019) | |

| EU | REACH 2006 | BLM and gBAM (chronic) | Independent and autovalidation (De Schamphelaere and Janssen 2004; De Schamphelaere and Janssen 2006; European Chemicals Agency 2008a) Cross-species validation (De Schamphelaere et al. 2006) |

|

| Canada | ECCC 2019 | BLM (chronic) | Autovalidation (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2019) | |

| Mn | UK | WFD 2000 | BLM (chronic) | Independent and autovalidation (Peters et al. 2011) |

| Ni | EU | WFD 2000 and REACH 2006 | BLM and gBAM (chronic) | Independent and autovalidation (Deleebeeck et al. 2007a, 2007b, 2008a, 2008b, 2009a, 2009b) Cross-species validation (Schlekat et al. 2010) |

| Pb | EU | WFD 2000 and REACH 2006 | DOC adjustment (chronic) BLM and gBAM (chronic) | Autovalidation (European Commission 2010; Sub-Group on Review of the Priority Substances List 2011) Independent and autovalidation (Nys et al. 2016) Cross-species validation (Van Sprang et al. 2016) |

| Zn | EU | REACH 2006 | BLM and gBAM (chronic) | Independent and autovalidation (De Schamphelaere et al. 2005) Cross-species validation (De Schamphelaere et al. 2005) |

| Canada | CCME 2018 | MRM | Independent and autovalidation (Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment 2018) | |

| Australia and New Zealand | ANZG 2019 (draft) | MRM or BLM (chronic) | Cross-species validation (Australian and New Zealand Governments 2019) |

Does not include older PVALs that used hardness-based bioavailability adjustments and other BLMs that have not been adopted in PVALs.

ACR = acute to chronic ratio; ANZG = Australia and New Zealand Guidelines; BLM = biotic ligand model; CCME = Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment; DOC = dissolved organic carbon; ECCC = Environment and Climate Change Canada; gBAM = generalized bioavailability model; MRM = multiple regression model; PVAL = protective value; REACH = Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals; USEPA = US Environmental Protection Agency; WFD = Water Framework Directive.

Since publication of the 1985 guidelines, the US Environmental Protection Agency (2001) has determined that to meet the precondition for inclusion in the covariance model for determining the hardness relationship, a species should have definitive toxicity values available over a range of hardness concentrations such that the highest hardness is at least 3 times and at least 100 mg/L higher than the lowest. However, the USEPA has not provided specific guidance on validating the hardness–toxicity relationship included in development of PVALs for metals.

Currently, the European Chemicals Agency (2008b) and the European Commission (2011) provide some general recommendations of factors to consider when validating bioavailability models for use in environmental quality standards. In addition, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidance on the incorporation of bioavailability concepts for assessing the ecological risk and/or environmental threshold concentrations of metals and inorganic metal compounds provides specific direction for validating BLMs (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2016). Together, these documents discuss important considerations for the applicability of the models (e.g., range of water chemistries) and explain the use of autovalidation, independent validation, and cross-species extrapolation. For example, in species-specific models, it is recommended that bioavailability correction be used only if the models have been developed and validated for at least 3 major taxonomic groups, including an alga, an invertebrate, and a fish species.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER FOR MODEL-VALIDATION STUDIES

Table 2 presents a series of questions that should be considered when validating bioavailability models. Each of these questions is addressed at varying levels of detail in the sections that follow.

TABLE 2:

Questions to consider when validating bioavailability models

| Question | Comments |

|---|---|

| Is the validation study designed to test the accuracy of the model under the conditions for which the model was designed to perform? | A starting point for validation is to test the model with the species and conditions for which it was calibrated. |

| Are the organisms appropriate for testing the model? | Test organisms should be the species or species assemblages for which the model was parameterized/calibrated and to which the model is intended to be extrapolated. |

| Is the range of water chemistry appropriate for testing the model? | Bioavailability models need to be validated in a broad range of geographically and ecologically relevant water types, especially within waters that might produce high metal bioavailability. Consideration should be given to the range of chemistry conditions with which the model was developed. |

| Should the model be validated in a standard set of water chemistry conditions? | Models validated in a standard set of water chemistry conditions can provide a higher level of comparability among models; however, developing a standard test water for all metals will be especially challenging because factors that determine bioavailability can vary significantly among metals. |

| Is the model capable of predicting effects on the species or community in the water chemistry being tested? | Although bioavailability-based models are capable of predicting effects under laboratory conditions, less is known about performance under natural conditions in the field. |

| What level of extrapolation within or among taxonomic groups is appropriate? | Interspecific toxicity-prediction models can be used to predict responses among closely related species through the genus and even to the order level (e.g., US Environmental Protection Agency 2016b); however, extrapolation among major groups of organisms (e.g., cladocerans to aquatic insects) or across levels of biological organization is significantly more challenging because of variation in modes of action and mechanisms of toxicity. |

| Can the model be extrapolated across levels of biological organization? | Extrapolating across levels of biological organization is conceptually possible, and a few bioavailability models have been used to improve predictions of effects of metals on natural communities relative to hardness-based models in the field (Schmidt et al. 2010; Stockdale et al. 2010) and in mesocosm experiments (Iwasaki et al. 2013). |

| Can validation studies incorporate spatial and temporal variability occurring in the field? | Some modeling efforts that incorporate bioavailability and fluctuating concentrations of metals have been performed (e.g., Meyer et al. 2007a), but this needs more development. |

| Are multiple exposure routes for metals relevant to consider in validation of bioavailability models? | For some metals, physical effects (e.g., Al, Fe) or diet-borne exposure pathways (e.g., Hg, Se) might be necessary to consider in the validation study. |

| What is the accuracy goal for the model? | Validation needs to be rigorous but flexible enough to fit the user’s purpose. Support (or lack of support) for a model should be presented and reported in such a way that users can define their own level of acceptability (see Performance Evaluation section). |

| When is the model sufficiently validated? | Model validation is a continuous and iterative process that will necessarily be constrained by the amount of data available. Beck et al. (1997) provide guidance when deciding a sufficient level of model validation. |

TYPES OF VALIDATION STUDIES

A gradient of possible types of validation studies is shown in Figure 1, including laboratory tests conducted under controlled conditions, mesocosm studies conducted with natural communities but under controlled conditions, and field studies conducted under natural, uncontrolled conditions. The shaded area indicates that uncertainty in the validation results increases the further the level of biological organization/endpoint is away from the level of biological organization/endpoint for which the model was parameterized. The types of chemical, biological, and physical data needed to evaluate the accuracy of models in any of these 3 types of studies will be informed by the types of experiments and conditions tested in the model calibration and development phase. If standard toxicity tests were used to develop and calibrate the model(s), a minimum level of validation should include standard toxicity tests, with exposure conditions representing a range of conditions relevant to the waters of interest (Stephan et al. 1985). Because most bioavailability-based toxicity models have been developed for single species using data from laboratory toxicity tests conducted under controlled conditions, similar types of laboratory toxicity tests are most commonly used in validation studies.

FIGURE 1:

Studies that could be used to validate a bioavailability-based metal toxicity model. The width of the shaded area indicates that uncertainty in the validation results increases the further the level of biological organization/endpoint is away from the level of biological organization/endpoint for which the model was parameterized, which in this example is whole-organismal tests conducted in natural waters.

As the science matures, the types of experiments used to develop and calibrate the models likely will evolve. For example, models might be developed that are capable of predicting the effects of bioavailable metals at the community or ecosystem level. If these more complex models are to be incorporated into regulatory frameworks, the underlying models will have to be validated using toxicity tests or experiments that represent the appropriate level of ecological complexity (e.g., microcosms/mesocosms or in situ field testing).

The ability of a model to satisfactorily predict effect concentrations under a specified range of water quality conditions would provide support that the model is sufficiently parameterized. Poor model performance might indicate that 1) the model is not appropriately parameterized, 2) previously unconsidered factors (e.g., physical or water chemistry factors, ecological processes not incorporated into the model) affect biological response in the waters of interest, and/or 3) the exposure water was not in equilibrium (e.g., the metal had not equilibrated with the dissolved organic carbon [DOC] in the exposure water [Ma et al. 1999] and, thus, kinetic constraints at least partially controlled metal bioavailability).

Regardless of the chemical, biological, and physical conditions to be tested during validation, it is necessary to test metal concentrations over an appropriate gradient so effect concentrations (ECx values) can be calculated. For example, the appropriate metal concentration gradient for chroniceffect models should include low concentrations at approximately the chronic EC10 or EC20 values so the validation study is relevant to PVALs that are based on chronic effects in many regulatory jurisdictions. Special consideration might be needed when models capable of predicting ECx values for higher levels of ecosystem complexity (e.g., mesocosms) are being validated. In those cases, resource constraints might make it difficult to test a wide range of conditions or multiple metal concentrations to appropriately validate the model. Specific types of validation studies are further discussed in the Supplemental Data.

VALIDATION STUDY DESIGN AND DATA COLLECTION

Validation of bioavailability-based models (including BLMs, regression, and hybrid models) is most often based on single-species toxicity data sets that include measurements of water chemistry, metal exposure concentrations, and biological effects. The range of chemical conditions over which validation studies should be conducted will depend on the waters of interest to which the models will be applied and the range of water chemistry conditions over which the models have been calibrated. Several strategies might be used to choose appropriate water chemistry conditions to evaluate during validation studies, including identifying absolute ranges of water chemistry or identifying relevant combinations of water chemistries that represent extreme conditions. One approach for identifying relevant combinations of water chemistries would be to conduct principal components analysis of water chemistry data in the waters of interest (Brix et al. 2020). Although this approach might identify a set of water chemistry conditions relevant to the waters of interest, the user should determine if these conditions are within the range tolerated by the organisms being tested. For example, if the relevant range of pH includes very low or very high values (e.g., <3 or >9), those ranges could be excluded from validation if they are not relevant to the effects of the metal of interest. However, in real-world regulatory application, end users may desire to apply the model to these extreme conditions to set regulatory limits in waters with those conditions, and it would be useful to understand the interaction of metal exposure and extreme conditions for the organisms on toxicity. Otherwise, if no such testing is conducted, care should be taken if applying the model beyond the bounds of the testing and validation ranges. It could be beneficial to establish a standard set of water chemistry conditions for validation of models for a given metal or group of metals because commonality of testing can provide a higher level of comparability among models than when validation water chemistry differs among models and/or metals.

Other considerations related to chemistry and biology data requirements are potentially relevant from a validation perspective but might depend on the type of model being validated. In the current context of BLMs, there is a metal-speciation component and an accumulation component, whereby predicted effect concentrations directly depend on the water chemistry and the amount of metal accumulated at the biotic ligand. For these types of models, validation of the metal-speciation and accumulation components would ideally be performed during model development. However, quantification of metal accumulation currently is technically challenging or sometimes even practically infeasible for small test organisms (e.g., rotifers, small daphnids).

Because BLM-type models rely on chemical-speciation software to estimate the free-ion activity of metals from dissolved-metal concentrations, the metal-speciation component of the model should be calibrated for the toxicologically relevant range of metal concentrations the model will predict. If the metal-speciation component of the bioavailability model is based on a previously validated speciation model (e.g., the Windermere Humic Aqueous Model [WHAM] [Tipping 1994]) and the range of water chemistry is relevant in the waters of interest, independent validation of the speciation component is not considered necessary. If additional validation of the speciation component is desirable, speciation in the waters of interest could be evaluated (e.g., Van Laer et al. 2006). The types of approaches used to validate speciation would depend on the metal of interest and the available techniques to characterize speciation. In general, it would not be necessary to determine metal speciation during validation toxicity tests because the accuracy of the speciation component of the model could be tested using separate analytical chemistry experiments (Batley et al. 2004). However, it might be desirable to test speciation predictions of models under certain conditions, for example, if considerable organic matter is added during aqueous exposure (e.g., food for the test organisms, high densities of algae) and is not accounted for in the model.

Accumulation of metals at a biotic ligand could also be validated during model development, if possible. In many cases, the amount of metal accumulated at a biotic ligand is inferred (i.e., calculated from model parameterization that is based on toxicity results) and not based on measured metal concentrations. In those cases, validation of metal accumulation is not possible. Generally, the idea of a critical accumulation at a biotic ligand has been validated as proof of concept through accumulation and toxicity studies (Playle et al. 1993; MacRae et al. 1999). But if it is desirable to validate accumulation predictions (e.g., for the purpose of directly evaluating bioavailability and intrinsic organism sensitivity), organisms will have to be exposed to a metal of interest under a scenario in which water chemistry conditions are fully characterized (i.e., with regard to necessary model inputs). Tissue concentrations (e.g., specific target tissue or whole body) will then need to be determined and compared to predicted accumulations. However, it might be difficult to interpret and compare a predicted concentration of a metal at a biotic ligand (i.e., specific binding at a presumptive site of toxic action) with a measured tissue concentration (i.e., a composite of metal accumulation at a variety of sites that might and might not be related to toxicity). If the metal accumulation is not or cannot be validated, the critical accumulation concentration in the model can be viewed as a calibrated model parameter representing endpoint sensitivity.

Validation studies that generate new data

Table 3 outlines important factors to be considered when designing validation studies. These factors should be considered, regardless of the type of model to be validated.

TABLE 3:

Factors for consideration in the design of experiments for validation of bioavailability models

| Factors to consider | Comments | Caveats |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental design | • Capture full concentration–response range to calculate toxicity estimates • Use appropriate number of treatment replicates (Green 1979; ASTM, OECD, USEPA standardized methods) • Consider positive and negative controls (ASTM, OECD, USEPA standardized methods) • Replicate experiment over time to demonstrate reproducibility • Stipulate test acceptability criteria (ASTM, OECD, USEPA standardized methods) • Use accepted and defined statistical methods (Green 1979; ASTM, OECD, USEPA standardized methods) |

• The number of treatments can be determined based on the type of study that has been chosen (e.g., field versus lab) and based on the resources available • Regardless of the model, predicted ECx should optimally be the midrange of the test concentrations used • Test conditions should be tightly controlled • Test acceptability criteria exist for well-established protocols (e.g., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2004; Elonen 2018), but caution must be taken when testing with novel species for which such an extensive database or well-established protocol does not exist |

| Selection of species/taxa | • Consider how model was developed and the geographical location to which the model will be validated, including desirability of or requirement for taxonomic representation from that location • Validate model with species/taxa that the model was intended to represent • Determine if the model is to be extrapolated to relevant species/taxa, if it is predictive of ecologically relevant species/taxa (e.g., Schlekat et al. 2010; De Schamphelaere et al. 2014), and if it is to be applied to a range of taxa (microalgae, invertebrates, vertebrates) • Use standard characteristics of test organism (e.g., test starts with daphnid neonates <24 h old) • Consider sensitivity of the testing laboratory’s strain of the species to be tested, relative to the sensitivity of the strains in the data set used to parameterize/calibrate the model |

• Taxonomic diversity should be considered (i.e., if the model is based on one species or averaged across a taxonomic grouping [e.g., invertebrates]) • Although validating with species/taxa the model was developed for is a good check, these taxa might not be available to the user or relevant to the geographic region of interest • Caution must be taken when extrapolating models from one taxonomic group to another (Van Sprang et al. 2009; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2016) • Unusually low or high relative sensitivity of the strain used in the validation test might lead to an erroneous conclusion about model bias |

| Exposure conditions | • Use exploratory runs of the model during the experimental design phase to help determine appropriate water chemistry • Consider ecologically relevant exposure conditions, water chemistry within the bounds of concern to the user and the geographic range of interest, exposure water flow (static, renewal, or flow-through), and implications for chemical equilibrium • Measure routine water chemistry parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, conductivity, hardness, alkalinity, DO, DOC) • Ensure measurement of appropriate metal form or species • Use appropriate lighting (both intensity and light cycle) |

• Caution must be taken if validating the model outside of the water chemistry parameter ranges for which it was originally developed |

| Media collection | • Decide whether using natural or synthetic dilution water • Follow guidance for best practice of natural water collection and synthetic water preparation |

• In natural waters, consider concentrations of metals and speciation-modifying factors (e.g., pH, hardness, natural DOC, and ligands) • Although synthetic waters allow tight control of physical–chemical parameters, they do not necessarily represent waters of interest |

| Endpoints | • Ensure appropriate endpoints for the validation objective (e.g., ECx for reproduction in daphnids) • Consider the endpoints predicted by the model |

• Use caution when extrapolating to endpoints the model was not developed to predict |

ASTM = American Society for Testing and Materials; DO = dissolved oxygen; DOC = dissolved organic carbon; ECx= x% effect concentration; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; USEPA = United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Validation using existing toxicity data

Bioavailability-based models can be validated using existing toxicity data; however, it is crucial to screen and check the data for relevance and reliability before using them in a validation study. In addition, it is important that the data selected for an external validation be independent of that used in the parameterization/calibration of the model(s) to be validated.

Several documents exist for guidance on general (Klimisch et al. 1997; US Environmental Protection Agency 2009; European Commission 2011; Warne et al. 2015; Moermond et al. 2016; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2016) and metal-specific (Warne et al. 2015; Gissi et al. 2016) data screening and quality checking. Important questions for consideration in determining the relevance and reliability of data for model validation include, but are not limited to, the following: Did the study report exposure-water chemistry parameters needed for the model(s) under consideration? Were metal concentrations in test waters measured and reported? Were the endpoints ecologically relevant? Were appropriate methods used and adequately reported (e.g., ASTM International, OECD, USEPA standardized methods)? Was the dilution water type appropriate (e.g., synthetic or natural)? Were the study data of sufficient quality to be used in the validation of the model and development of PVALs?

However, care should be taken when considering the exclusion of data. For example, the USEPA’s guidelines for derivation of Water Quality Criteria (Stephan et al. 1985) do not allow toxicity data from exposure waters containing >5 mg DOC/L, but validation studies should not exclude toxicity data from exposure waters containing higher DOC concentrations if some of the waters of interest contain higher concentrations of DOC. For example, Thurman (1985) compiled wide ranges of DOC concentrations in rivers (1–60 mg C/L) and lakes (1–50 mg C/L), and Arnold (2005) reported estuarine DOC concentrations in the United States ranging from approximately 1 to 10 mg C/L.

The chemical data collected in a validation study should, at a minimum, include measurements of the relevant form of the metal of interest and all chemical concentrations needed to perform model calculations. For example, if TMFs in the model include hardness cations (Ca and Mg), pH, and DOC concentrations, measurement of those water chemistry characteristics would be needed. In addition, water chemistry characteristics that could potentially affect organism health or that might be important features of the water of interest should be measured (e.g., temperature, dissolved oxygen, ammonia, other metals). If multiple types of models (e.g., empirical regression models or BLMs) are being considered for validation, relevant chemistry information for both models should be collected. Similarly, if a relatively simple model (i.e., a model with few parameters) is being validated but some additional parameters are suspected to affect toxicity, those parameters should be measured. Also, if the model being validated includes a speciation component, factors that might influence the speciation of the metal of interest but might not be included in the bioavailability-based model should be measured. For example, if a metal speciation–based model for Cu (e.g., WHAM VII) is being validated with toxicity data from natural waters, concentrations of Al and Fe (which can compete with Cu for binding to DOC) should be measured. Water samples should be retained after the tests are conducted so that potential complicating factors can be investigated, if needed. In the future, analytical techniques will likely improve so that it might be feasible to accurately measure concentrations of additional analytes that might be important modifiers of metal speciation (e.g., sulfide).

When existing toxicity data are available (but not used to parameterize the model[s] under consideration), not all of the necessary water chemistry inputs to the model might have been reported. Instead of concluding that those toxicity data should not be used in a validation study for that model, it might be possible to address those data deficiencies using one of several approaches for post hoc data estimation or gathering (Van Genderen et al. 2020). In addition, the absence of some water chemistry inputs might not be fatal in a validation study. For example, K concentration often is not a crucial input for metal speciation–based models. Thus, a sensitivity analysis of the model inputs could be used to narrow the list of water chemistry parameters that are essential for adequate validation of a bioavailability-based toxicity model within a specified range of water chemistry conditions (European Food Safety Authority 2014).

Biological data needs for validation of models will be determined by the types of toxicity tests used during model development. For example, a model that predicts effect concentrations for Daphnia magna survival will need to be validated by toxicity tests that evaluate D. magna survival under similar exposure conditions (e.g., continuous exposure and appropriate exposure water and duration). In addition, toxicity data will be needed for other species to which the D. magna model will be applied, if a cross-validation study is being conducted.

In addition to chemical and biological data needs, physical data (e.g., light intensity, temperature, photocycle, type of substrate) that are potentially relevant to organisms or the waters of interest should be measured and documented during field- and laboratory-based validation studies.

VALIDATION STUDIES THAT HAVE BEEN REPORTED IN THE LITERATURE

At least one type of autovalidation, independent validation, or cross-species extrapolation has been reported for metal-toxicity models in the 118 publications listed in Supplemental Data, Table S-1. That table contains entries for 10 different metals (Ag, Al, Cd, Co, Cu, Mn, Ni, Pb, U, Zn), 2 metals reported as their free ion activity (Cu2+, Ni2+), and a variety of metal mixtures and 49 different biological species (8 fish species, 30 species of aquatic invertebrates or assemblages of aquatic invertebrate species, 7 algal species or assemblages of algal species, 1 bacterial species, and 3 aquatic plant species), for a total of 118 biological species and metal combinations (including mixtures). Most of the entries are for tests conducted in freshwaters (94%, including dilution water sources composed of natural waters, reconstituted waters [e.g., a standard recipe prepared in deionized water], dechlorinated tap water, and natural freshwater blended with reverse osmosis–treated water). Of the 10 metals, Cu has the highest percentage of model validations (34%). Of the 250 species and metal combination entries, 50% contain only autovalidations, 26% contain only independent validations, 8% contain only cross-species extrapolations, and 17% contain both an autovalidation and an independent validation (Table 4). BLM-type models are the most frequently validated type of model (66% of the species and metal combination entries), and plots of predicted versus observed toxicity metrics (i.e., 1:1 plots) are the most frequently used method for presenting validation results (80% of the species × metal combination entries; Table 4).

TABLE 4:

Summary of the 250 species and metal combination entries in the compilation of metal bioavailability toxicity model studies in Supplemental Data, Table S1

| Category | Typea | Percent (number)b |

|---|---|---|

| Type of model | BLMc | 66.0 (165) |

| WHAM-FTOXd | 11.6 (29) | |

| MRM | 14.8 (37) | |

| Mixed | 9.2 (23) | |

| FIAM | 4.4 (11) | |

| Hardness | 1.6 (4) | |

| GLMM + WHAM | 0.4 (1) | |

| MixTox | 0.4 (1) | |

| TKTD | 0.4 (1) | |

| TOX | 0.4 (1) | |

| WHAM regression | 0.4 (1) | |

| Type of validation | Autovalidation | 49.6 (124) |

| Independent validation | 25.6 (64) | |

| Autovalidation and independent validation | 16.8 (42) | |

| Cross-species extrapolation | 8.0 (20) | |

| Method used to present results | Predicted versus observed (1:1) plot | 80.4 (201) |

| Other graphical method | 17.6 (44) | |

| Table | 5.2 (13) | |

| Narrative | 0.4 (1) |

Types of models: BLM = biotic ligand model-type model (e.g., Di Toro et al. 2001); FIAM = free-ion activity model; GLMM = generalized linear mixed model; Hardness = based on hardness regression; Mixed = mixture of model types; MixTox = MixTox model of Jonker et al. (2005); MRM = multiple regression–type model; TKTD = toxicokinetic/toxicodynamic model; TOX = Tox function–type model (e.g., Balistrieri et al. 2015); WHAM = WHAM-FTOX-type model (e.g., Tipping and Lofts 2013); WHAM = Windermere humic aqueous model (e.g., Tipping 1994); WHAM regression = regression based on WHAM speciation.

For types of models and for methods used to present results, the sum of the types exceeds 100% because for some entries more than one type of model was validated or more than one type of method was used to present the validation results.

In addition, 1 metal speciation-validation analysis was conducted for a BLM.

In addition, 4 metal speciation-validation analyses were conducted for a WHAM.

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

Model validation includes qualitative and/or quantitative evaluation of a model’s accuracy and predictive capabilities (US Environmental Protection Agency 2009). For bioavailability-based toxicity models, validation can be considered in a 2-part sequence to address the following overarching issues. The first step is qualitative evaluation: Was model development sufficiently rigorous to warrant consideration? The second step is quantitative evaluation: Is use of the model justified relative to a null model (in which all of the variation in the toxicity-response variable is attributable to random variation among the test organisms and not to differences in TMFs)? Is there a bias in model predictions? Is the model accurate? Further descriptions of qualitative and quantitative evaluations of bioavailability-based toxicity models are provided in the following sections.

Qualitative evaluations

The purpose of a qualitative evaluation is to assess the credibility of a model (i.e., is the model appropriate and relevant?). Considerations for the evaluation could include the following.

Model structure.

Is the model based on mechanistic descriptions, empirical regressions, or hybrid modeling that includes both mechanistic and empirical elements? How many TMFs are considered in the model? How many taxa are considered in the model? Are model formulations consistent with current understanding of metal bioavailability and uptake? Is the model based in part on other validated models (e.g., WHAM)?

Calibration procedure.

How many data sets were considered in the model calibration? Was model calibration performed across an appropriate range of water chemistries? Were ancillary measurements (e.g., free metal ion activity or gill or whole-body accumulation of metal) used to constrain the model calibration? Was the calibration rigorous (e.g., stepwise calibration for the various TMFs being considered)? Was information on metal chemistry (e.g., hard-soft-acid-base theory [Jones and Vaughn 1978] and/or quantitative ion characteristic activity relationships [Ownby and Newman 2003]) used to constrain model calibration?

Model performance.

Does the model adequately describe the calibration data sets (autovalidation)? Was the model tested for other species or endpoints not included in the calibration (cross-species and cross-endpoint validation)? Was the model tested using independent data sets (independent validation)?

The final outcome of a qualitative evaluation could be a quality rating of the model structure, calibration procedure, and performance (e.g., 5 = excellent, 4 = very good, 3 = good, 2 = fair, 1 = inadequate). Although quality ratings are subjective, the purpose of the qualitative evaluation is to differentiate models that were rigorously developed and shown to perform well over a wide range of TMFs (with separate checks on intermediate model outputs) from models that have no mechanistic underpinning and/or were developed and tested using very limited data sets. Depending on the results of the qualitative evaluation, further validation may be warranted for all or selected models using the quantitative evaluations, as described in the following section.

Quantitative evaluations

Performance evaluations of models have often been presented graphically, but numerical metrics have also been used by some authors. For example, in Van Sprang et al (2016, see their Supplementary Material 2), the performance of several bioavailability models to predict Pb toxicity for nonmodel test species was analyzed with additional statistics (mean, median, and maximum prediction error and percentage of EC50 values that were predicted within 2-fold error). Janssen and Heuberger (1995) presented a long list of statistical performance measures for comparing model predictions and observations.

In most graphical presentations of model performance, model-predicted ECx values are plotted on the vertical axis and their paired, observed ECx values are plotted on the horizontal axis (e.g., Di Toro et al. 2001; Santore et al. 2001; Figure 2). The diagonal solid line in each panel of Figure 2 is the 1:1 line of perfect agreement between predicted and observed values. The diagonal dashed lines in Figure 2 represent the boundaries for model predictions that fall within plus or minus a factor of 2 of the observed ECx values. The factor of 2 has often been used in assessing the accuracy of bioavailability-based toxicity models and is based on the among-test variability in LC50 values for fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) exposed to Cu in Lake Superior water (Erickson et al. 1996). Considering random variation in toxicity results, a factor-of-2 agreement between predicted and observed LC50 or EC50 values is consistent with the level of precision that would be expected from such a model. Recent expanded analyses with data for D. magna exposed to Cd, Cu, Ni, or Zn generally support the factor-of-2 rule of thumb (Santore and Ryan 2015; Meyer et al. 2018); however, further analyses of existing repeated-test data sets or new repeated-test studies could provide additional support for this conclusion (Meyer et al. 2018).

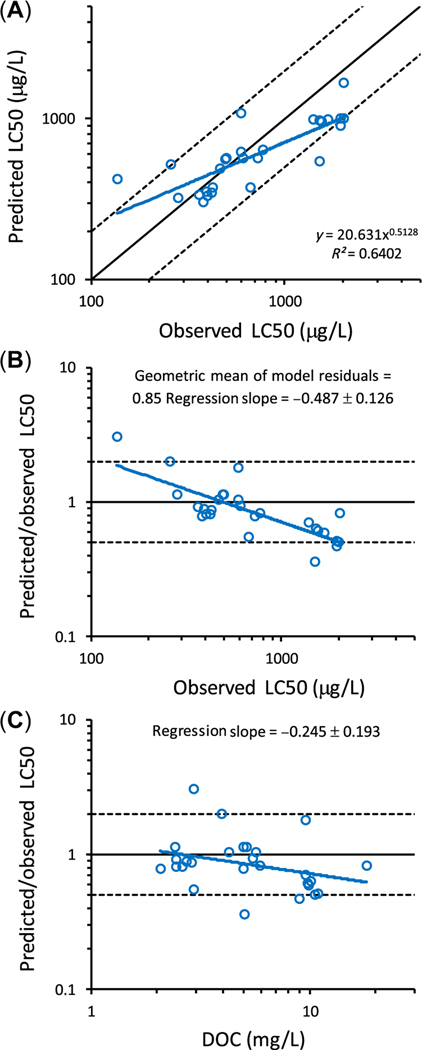

FIGURE 2:

Four hypothetical cases of performance of bioavailability-based metal toxicity models, for predictions of an effect concentration at x% impairment of a biological response (ECx). The solid black diagonal line is the 1:1 line of perfect agreement between model-predicted and observed ECx values; the dashed black diagonal lines are plus or minus a factor of 2 above and below the 1:1 line. (A) An accurate, unbiased model with data points falling along the 1:1 line; (B) a less accurate, unbiased model with data points exhibiting more scatter about the 1:1 line; (C) a biased model that consistently overpredicts the observed ECx values; and (D) a biased model that predicts intermediate ECx values well but has a clear bias when predicting low and high ECx values.

Four hypothetical cases of model performance are depicted in Figure 2. The first case (Figure 2A) represents an accurate, unbiased model prediction with data points falling along the 1:1 line with a limited amount of scatter. The second case (Figure 2B) shows a less accurate, unbiased model prediction with data points exhibiting more scatter about the 1:1 line. The third case (Figure 2C) shows a biased model prediction in which the model consistently overpredicts the observed ECx values; however, consistent underprediction might occur in other situations. The example in Figure 2C would only be possible for an independent-validation or cross-species-validation study (because an autovalidation study, which by definition uses the same toxicity data with which the model was parameterized, would have the data points approximately equally distributed above and below the diagonal 1:1 line). The last case (Figure 2D) shows a biased model that predicts intermediate ECx values well but has a clear bias when predicting low and high ECx values.

Although the accuracy of a model can be generally inferred from the type of plot presented in Figure 2, the extent of the variability and the extent of the bias (i.e., overprediction or underprediction of the model) are difficult to determine only from inspection of those data points. Alternative ways of evaluating model performance are presented in the following paragraphs for a validation data set of the toxicity of Cu to larval fathead minnows (Ryan et al. 2004) and are explained in more detail in the Supplemental Data.

Figure 3A shows a typical comparison of BLM-predicted LC50 values (using the BLM of Santore et al. 2001) versus observed LC50 values for larval fathead minnows. This validation data set most closely resembles the hypothetical validation data set in Figure 2D. Model predictions are within a factor of 2 of the observed LC50 values for 24 of the 27 data points. However, the slope of a regression of the data points (0.5128) is considerably less than 1. This indicates a bias in the model, with the model underpredicting toxicity at low observed LC50 values and overpredicting toxicity at high observed LC50 values.

FIGURE 3:

(A) Comparison of biotic ligand model–predicted and observed median lethal concentration (LC50) values for larval fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) exposed to Cu in a variety of surface waters (Ryan et al. 2004). The equation for the blue regression line is Predicted LC50 = 20.631 × (Observed LC50)0.5128 (n = 27, R2 = 0.6402). (B) The same data plotted as the predicted LC50/observed LC50 ratio versus observed LC50, analogous to a plot of regression residuals. Slope of blue regression line = −0.487 (n = 27, 95% CI −0.361 to −0.613); geometric mean predicted LC50/observed LC50 ratio = 0.85. (C) The same data plotted as the predicted LC50/observed LC50 ratio versus dissolved organic carbon concentration, analogous to a plot of regression residuals. Slope of blue regression line = −0.245 (n = 27, 95% CI −0.051 to −0.438). In all 3 panels, the solid black diagonal line is the 1:1 line of perfect agreement between model-predicted and observed effect concentration at x% values; the dashed black diagonal lines are plus or minus a factor of 2 above and below the 1:1 line. DOC = dissolved organic carbon.

Using the same data, Figure 3B provides an alternative presentation of model-predicted versus observed LC50 values. In this format, a form of model residual (i.e., the predicted LC50/observed LC50 ratio) is plotted versus the observed LC50. The solid horizontal line (slope of 0, intercept of 1) indicates the line of perfect agreement between the model-predicted and observed LC50 values. Dashed horizontal lines in Figure 3B represent the boundaries for model predictions that fall within plus or minus a factor of 2 of the observed LC50 values. An advantage of the type of plot in Figure 3B is that potential bias in the model predictions can be evaluated, as follows. First, the geometric mean of the model residuals can be used to determine if there is a consistent overprediction or underprediction of LC50 values. For the larval fathead minnow validation data set of Ryan et al. (2004), the geometric mean of the model residuals is 0.85 (compared to the expected, unbiased geometric mean of 1), indicating that there is only a slight underprediction in the observed LC50 values. Second, the slope of a regression of the data points on the plot can be used to evaluate if the model predictions are biased relative to the independent variable on the horizontal axis. In Figure 3B, the slope of the regression is –0.49, indicating a bias in the model relative to the observed LC50 values.

In addition to plotting predicted/observed LC50 ratios versus observed LC50 values, similar evaluations of model residuals should be performed to evaluate potential biases in model predictions, by plotting predicted/observed LC50 ratios versus known or suspected TMFs (e.g., pH, hardness, alkalinity, DOC). For example, the slope of a regression of the BLM-predicted LC50/observed LC50 ratio versus DOC concentration in the Ryan et al. (2004) data set is −0.25 (Figure 3C), indicating a smaller bias in the BLM relative to the DOC concentration than relative to the LC50 (cf. Figure 3B). Ryan et al. (2009) used a plot of predicted/observed ratio of LC50s to understand pH and hardness biases in Cu BLM predictions for D. magna in soft waters; the biases were addressed by modifying the BL–CuOH and BL–Ca binding constants. Similarly, DeForest and Van Genderen (2012) used a plot of predicted/observed ratios of acute and chronic toxicity values versus pH to understand a pH bias in Zn BLM predictions, and they also used the predicted/observed toxicity ratios to optimize the BL–ZnOH binding constant.

In the above discussions of Figure 3, the predicted LC50 values were considered accurate if predictions were within a default factor of 2 of their paired, observed LC50 values. In many cases, it might be useful to evaluate accuracy based on other acceptance criteria. For example, a factor of 1.5 or 3 might be more appropriate in some situations; however, an acceptability margin less conservative than a factor of 2 (e.g., a factor of 3) might mask an underlying weakness in the model instead of being characteristic of random variation, thus leading to inadequate bioavailability normalization. In addition, other variations on this “factor-of” approach for performance evaluation are possible. For example, Parrish and Smith (1990) recommended calculating a “factor-of-f” as 1) the ratio of the modeled value divided by either the upper 95% confidence limit of an observed value, or 2) the ratio of the lower 95% confidence limit of an observed value divided by the modeled value (depending on whether the modeled value was greater than or less than the mean observed value, respectively), instead of calculating the “factor-of” as the ratio of the modeled value divided by the mean observed value.

Model accuracy associated with various acceptability criteria can be presented as a cumulative distribution of the relative differences in predicted and observed response. For example, the cumulative distribution of the relative differences in predicted and observed LC50 values (as expressed by the predicted LC50/observed LC50 ratio) is shown as the blue circles in Figure 4A for the Cu-BLM predictions from the Ryan et al. (2004) independent-validation data set. In this figure, the percentage of predictions that fall within plus or minus a factor of 2 of the observed LC50 values can be evaluated by subtracting the cumulative probability associated with a predicted/observed value of 0.5 from the cumulative probability associated with a predicted/observed value of 2. In similar fashion, the percent of predictions that fall within plus or minus some other assigned factor of agreement can also be calculated. In addition, an estimate of model bias can be obtained from the predicted/observed value for the 50th percentile value (where a value of 1 indicates no bias in the median model prediction) and the shape of the distribution.

FIGURE 4:

Cumulative probability distributions of (A) model-predicted median lethal concentration (LC50)/observed LC50 ratio and (B) the factor of agreement between model-predicted and observed LC50 values (the factor of X) for larval fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) exposed to Cu in a variety of surface waters (Ryan et al. 2004). Blue symbols represent ratios for LC50 values calculated using a biotic ligand model; green symbols represent ratios for LC50 values calculated using a null model (i.e., the predicted LC50 for all 27 different exposure waters equals the geometric mean of the 27 observed LC50 values). BLM = biotic ligand model.

A cumulative distribution plot also provides a convenient approach for comparing the performance of different models. This is shown in Figure 4A, where the BLM predictions (blue circles) are compared to a null model (green triangles). For the null model, the predicted LC50 in each exposure water is the geometric mean of all 27 observed toxicity responses. The reduction in the “spread” of the BLM distribution (relative to the null model) indicates that the BLM is able to explain more of the total variance in the observed data than the null model explains. This result could be summarized by comparing the sum of the squares of the residuals for the BLM and null model.

Although Figure 4A is a useful graphic for presenting accuracy and potential bias of model predictions and for comparing the relative performance of different models, some users might find the figure difficult to interpret. A simplified version of Figure 4A can be constructed by considering the magnitude (and not the direction) of differences in predicted/observed responses. In this evaluation, a model prediction that is a factor of 2 below the observed response is counted the same as a model prediction that is a factor of 2 above the observed response. The resulting simplified plot for the cumulative distribution is shown in Figure 4B. This plot can be readily used to evaluate the cumulative percentile of model predictions that meet a prescribed acceptability criterion. For example, the projected lines in Figure 4B indicate that BLM predictions are within a factor of 2 of the observed LC50 values for 82% of the observed values. In comparison, the null-model predictions are within a factor of 2 of the observed LC50 values for 57% of the observed values. The plot can also be used to determine the factor of X associated with a specified probability. For example, a specified cumulative probability of 0.68 (representative of ±1 standard deviation) would correspond to a factor of 1.6. The value of 1.6 could then be interpreted as an uncertainty factor for the predictive capability of the model.

Evaluation of the cumulative probability distributions in Figure 4 allows a user to determine whether there is sufficient quantitative evidence to select a given model over another. If data are from repeated toxicity tests using the same strain of a test organism in the same water quality, a cumulative probability distribution of those ECx values can also be plotted in Figure 4A and B (see discussion in the Supplemental Data). Comparison of that distribution to the cumulative probability distribution for a given model can show the relative amount of variability in the model-predicted results that might be attributable to random effects and the relative amount that might be attributable to TMFs not included in the model.

In practice, the types of quantitative evaluations discussed above should be performed for autovalidation, cross-validation, and independent validation of one or more models (including the null model). When possible, data from multiple data sets should be considered. The final outcome of the quantitative evaluation could be expressed as a performance rating for the accuracy of the model and as a more detailed rating for its potential bias. For model accuracy, the performance rating could be based on the cumulative percentile that is less than or equal to a prescribed acceptability ratio (e.g., a factor of 2). Because 82% of the predicted LC50 values are within a factor of 2 of the observed LC50 values (Figure 4B), the model accuracy rating for the larval fathead minnow data set would be 0.82 (or 82%).

For a more detailed rating for model bias, the performance rating could be based on several factors, including the geometric mean of the model residuals and the computed regression slope for the model residuals. In this scheme, the geometric mean of the model residuals could be used directly as a measure of bias for cases in which the geometric mean is ≤1. For cases in which the geometric mean is >1, the performance rating would be given as the inverse of the geometric mean (e.g., a geometric mean of 2.5 would have a performance rating of 0.4). The closer the geometric mean of the model residuals is to 1, the higher the performance rating. We propose that the regression slope could also be expressed as a performance rating by converting the regression slope into a transformed value between 0 and 1, using the relationship

| (1) |

where the tan−1 operator is expressed in radians. In this case, the closer the regression slope is to a horizontal line in Figure 3B (i.e., a slope of 0), the closer the slope rating will be to 1. Conversely, the closer the regression is to a vertical line in Figure 3B (i.e., a slope of infinity), the closer the slope rating will be to 0. In this evaluation, a slope rating should be determined for the regression slope of the model residuals (i.e., the predicted/observed ECx ratio) plotted versus the observed ECx and versus each of the known or suspected TMFs.

We propose that an overall rating of model bias could be calculated as the summation of the performance rating for the geometric mean of the model residuals and for the performance ratings for the regression slope of the model residuals, divided by the total number of the individual ratings. For the larval fathead minnow validation data set (Figure 3B), the first performance rating would be the geometric mean of the model residuals (0.85). A second performance rating can be included based on the regression slope of model residuals versus the LC50 values (Figure 3B). Substituting that slope of −0.49 into Equation 1, the slope performance rating would be 0.71. Other performance ratings can be added for the regression slopes of model residuals versus TMFs. For example, a regression slope for model residuals versus DOC of − 0.25 (Figure 3C) would equate to a DOC regression slope rating of 0.84. The overall bias rating would then be (0.85 + 0.71 + 0.84)/3 = 0.80. Weighting factors could also be added to this evaluation (e.g., to account for any covariance in TMFs).

Comparisons among models

A rating index like that described in the previous section could help regulators to quantitatively rank the performance of various candidate models, and the scores could be scaled to fit any range of values that might be used in a broader model-evaluation algorithm (e.g., Van Genderen et al. 2020). In that way, if appropriate water chemistry data are available, various currently used and proposed bioavailability-based metal toxicity models could be compared using the same validation data set to help decide whether the currently used model(s) should be reconsidered in a given regulatory setting. To that end, it would be useful to validate the current hardness-based metal toxicity models used in many regulatory jurisdictions concurrent with validations of other bioavailability-based models.

VALIDATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR MODEL USE

The primary objective of the model validation process is to evaluate and communicate the level of uncertainty in the context of the model’s intended application, with the goal of developing a model that produces consistently accurate and defensible outcomes. An overriding objective of the model validation process is to ensure that the evaluated model adequately and appropriately represents metal bioavailability over the range of conditions to which it is being applied, consistent with the end user’s requirements. The relative importance of each model component considered in the validation process is expected to vary with the specific model and its intended application. Coordinated planning between the model validator and end users (e.g., regulatory community) and early consideration of the range of conditions to which the model may apply are therefore crucial to the validation process.

Figure 5 depicts a process diagram for the validation of a bioavailability-based model, outlining steps that help to ensure that the validated model will support its intended application throughout its life cycle. Initial planning represents the first step of the validation process. This step, which occurs before formal model validation, is important for 1) characterizing the type and level of model validation that is necessary, 2) establishing the needs of the end users and critical objectives of the validation process, and 3) ensuring that the validated model will support its intended application. Considerations relevant to model validation that should be addressed during validation planning include defining the specific scope and objectives of the model validation; developing a model validation plan, consistent with best practices and goals established for the intended model use; establishing a framework for communicating validation objectives, priorities, processes, outcomes, and considerations; identifying and initially evaluating potential evaluation needs, related to model performance; and communicating and discussing expected applications and considerations with the model end users, including the potential strengths and weaknesses of the model as related to the model-validation process. Consideration during planning will help to establish a basis for the data-validation requirements and later evaluation of model performance and acceptability.

FIGURE 5:

Validation process diagram for bioavailability-based models for metals.

Important to the validation process is the recognition that models represent a simplification of reality. Some investigators have suggested that a model can never be truly “validated” but can only be invalidated for a specific use or application (Oreskes et al. 1994). Validation processes must adhere to best practices and remain consistent with technical defensibility; however, validation processes and model acceptability should be evaluated based on defining the intended model use and the corresponding level of rigor necessary to determine if the model can accomplish what it was designed to do. This “fit-for-purpose” concept was described in the USEPA’s Framework for Human Health Risk Assessment to Inform Decision Making (US Environmental Protection Agency 2014) and is applicable to the model-validation process by focusing on defining and incorporating validation requirements early in the model planning and development process. In addition, the “fit-for-purpose” concept supports consideration of the model’s intended use, statutory requirements, and inherent limitations in the data and methods available for model development. For example, performance of toxicity models sometimes is evaluated based on chronic EC50 values (e.g., plots of predicted versus observed chronic EC50), but PVALs often are based on chronic EC10 or EC20 values. Because goodness of agreement in 1:1 plots of predicted versus observed EC10 values can differ from goodness of agreement in 1:1 plots of predicted versus observed EC50 values, a disconnect can arise that might lead to the model validation not being as fit for purpose as desired.

Model-validation outcomes should be evaluated by the model validator in conjunction with the end users for their accuracy and predictive capability. In addition to validation outcomes, this evaluation should consider and document supporting considerations including uncertainties and implications of those uncertainties on model robustness, model applicability and protectiveness, and the range of conditions under which the model is supported. When multiple models are validated, they can be compared to determine the accuracy and predictive capabilities of each, as part of a final model selection.

Scientific knowledge relevant to a validated model is expected to continue advancing, along with the availability of additional supporting data. Periodic postvalidation evaluations or re-evaluations should be considered, particularly following major changes in the science or available data underlying the model. Such events represent potential triggers for evaluating whether a model may require further validation or revision. Information and supporting evaluations developed and documented during the validation planning and postvalidation processes, including the characterization of uncertainties, can be used along with selected validation testing, to identify the need for model revision.

CONCLUSIONS

Model validation should be rigorous but flexible enough to fit the user’s purpose. Validation is a continuum: the higher the level of validation, the less uncertainty in the model. Although a model can never be fully validated to a level of zero uncertainty, it can be sufficiently validated to fit a specific purpose or objective. Models should be validated using experimental designs and endpoints consistent with the data sets that were used to parameterize and calibrate the model. Other study types can inform the weight of evidence regarding model performance; however, not all studies are equally informative. In general, greater uncertainty is associated with validation studies that evaluate endpoints or levels of biological organization that differ from the endpoints or levels of biological organization for which the model was developed. For example, extrapolation of a model developed for predicting lethality in a given species to another species might carry less uncertainty than extrapolation of that same model to an ecosystem-level response.

Models should be validated across a broad range of geographically and ecologically relevant water types. In addition, it could be beneficial to establish a standard set of water chemistry conditions for validation of models for a given metal or group of metals because commonality of testing can provide a higher level of comparability among models than when water chemistry differs among models and/or metals. Given the widespread current use of hardness-based metal toxicity models in PVALs, it would be useful to validate the current hardness-based models concurrent with validations of other bioavailability-based models.

Support (or lack of support) for a model should be presented/reported in such a way that users can choose their own level of acceptability (e.g., by inspection of the cumulative density function graph that displays the extent and probability of deviation of model-predicted results from observed results). In addition, models need to be evaluated for accuracy, appropriateness, and relevance (e.g., “fit for purpose”) before use in a regulatory setting.

Model validation is a continuous and iterative process that will necessarily be constrained by the amount of data available. For use in a PVAL setting, it is important to recognize that models have a life cycle and that scientific knowledge will continue to advance along with the collection of additional data. As models advance, they might need to undergo additional validation. In the future, as more models are developed and refined to predict population-, community-, and ecosystem-level effects of metals, validation methodology will have to evolve to meet those needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment—

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the SETAC technical workshop Bioavailability-Based Aquatic Toxicity Models for Metals, including the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Metals Environmental Research Associations, Dow Chemical Company, Newmont Mining Company, Rio Tinto, Umicore, and Windward Environmental. We also thank the SETAC staff for their support in organizing the workshop.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement—The data presented in Figures 3 and 4 are from Ryan et al. (2004). No other real data were used in the present study.

Supplemental Data—The Supplemental Data are available on the Wiley Online Library at DOI: 10.1002/etc.4563.

REFERENCES

- Adams W, Blust R, Dwyer R, Mount D, Nordheim E, Rodriguez PH, Spry D. 2020. Bioavailability assessment of metals in freshwater environments: A historical review. Environ Toxicol Chem 39:48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WR. 2005. Effects of dissolved organic carbon on copper toxicity: Implications for saltwater copper criteria. Integr Environ Assess Manag 1:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian and New Zealand Governments. 2019. Australian and New Zealand guidelines for fresh and marine water quality. Canberra, ACT, Australia. [cited 2019 November 11]. Available from: www.waterquality.gov.au/anz-guidelines [Google Scholar]

- Balistrieri LS, Mebane CA, Schmidt TS, Keller W. 2015. Expanding metal mixture toxicity models to natural stream and lake invertebrate communities. Environ Toxicol Chem 34:761–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batley GE, Apte SC, Stauber JL. 2004. Speciation and bioavailability of trace metals in water: Progress since 1982. Aust J Chem 57:903–919. [Google Scholar]

- Beck MB, Ravetz JR, Mulkey LA, Barnwell TO. 1997. On the problem of model validation for predictive exposure assessments. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 11:229–254. [Google Scholar]

- Brix KV, DeForest DK, Tear L, Peijnenburg W, Peters A, Traudt E, Erikson R. 2020. Development of empirical bioavailability models for metals. Environ Toxicol Chem 39:85–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. 2018. Scientific criteria document for the development of the Canadian water quality guidelines for the protection of aquatic life: Zinc. Winnipeg, MB, Canada. [cited 2019 November 11]. Available from: https://www.ccme.ca/en/resources/canadian_environmental_quality_guidelines/scientific_supporting_documents.html [Google Scholar]

- DeForest DK, Brix KV, Tear LM, Adams WJ. 2018. Multiple linear regression (MLR) models for predicting chronic aluminum toxicity to freshwater aquatic organisms and developing water quality guidelines. Environ Toxicol Chem 37:80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeForest DK, Van Genderen EJ. 2012. Application of USEPA guidelines in a bioavailability-based assessment of ambient water quality criteria for zinc in freshwater. Environ Toxicol Chem 31:1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleebeeck NME, De Laender F, Chepurnov VA, Vyverman W, Janssen CR, De Schamphelaere KAC. 2009a. A single bioavailability model can accurately predict Ni toxicity to green microalgae in soft and hard surface waters. Water Res 43:1935–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleebeeck NME, De Schamphelaere KAC, Heijerick DG, Bossuyt BTA, Janssen CR. 2008a. The acute toxicity of nickel to Daphnia magna: Predictive capacity of bioavailability models in artificial and natural waters. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 70:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleebeeck NME, De Schamphelaere KAC, Janssen CR. 2007a. A bioavailability model predicting the toxicity of nickel to rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) in synthetic and natural waters. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 67:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleebeeck NME, De Schamphelaere KAC, Janssen CR. 2008b. A novel method for predicting chronic nickel bioavailability and toxicity to Daphnia magna in artificial and natural waters. Environ Toxicol Chem 27:2097–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleebeeck NME, De Schamphelaere KAC, Janssen CR. 2009b. Effects of Mg2+ and H+ on the toxicity of Ni2+ to the unicellular green alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata: Model development and validation with surface waters. Sci Total Environ 407:1901–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleebeeck NME, Muyssen BTA, De Laender F, Janssen CR, De Schamphelaere KAC. 2007b. Comparison of nickel toxicity to cladocerans in soft versus hard surface waters. Aquat Toxicol 84: 223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schamphelaere KAC, Heijerick DG, Janssen CR. 2006. Cross-phylum comparison of a chronic biotic ligand model to predict chronic toxicity of copper to a freshwater rotifer, Brachionus calyciflorus (Pallas). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 63:189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schamphelaere KAC, Janssen CR. 2004. Development and field validation of a biotic ligand model predicting chronic copper toxicity to Daphnia magna. Environ Toxicol Chem 23:1365–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schamphelaere KAC, Janssen CR. 2006. Bioavailability models for predicting copper toxicity to freshwater green micro-algae as a function of water chemistry. Environ Sci Technol 40:4514–4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schamphelaere KAC, Lofts S, Janssen CR. 2005. Bioavailability models for predicting acute and chronic toxicity of zinc to algae, daphnids, and fish in natural surface waters. Environ Toxicol Chem 24:1190–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schamphelaere KAC, Nys C, Janssen CR. 2014. Toxicity of lead (Pb) to freshwater green algae: Development and validation of a bioavailability model and inter-species sensitivity comparison. Aquat Toxicol 155: 348–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Toro DM, Allen HE, Bergman HL, Meyer JS, Paquin PR, Santore RC. 2001. Biotic ligand model of the acute toxicity of metals. 1. Technical basis. Environ Toxicol Chem 20:2383–2396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]