Abstract

Background:

The diagnostic yield of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (ENB) is impacted by biopsy tool strategy and rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) use. This analysis evaluates usage patterns, accuracy, and safety of tool strategy and ROSE in a multicenter study.

Methods:

NAVIGATE (NCT02410837) evaluates ENB using the superDimension navigation system (versions 6.3 to 7.1). The 1-year analysis included 1215 prospectively enrolled subjects at 29 United States sites. Included herein are 416 subjects who underwent ENB-aided biopsy of a single lung lesion positive for malignancy at 1 year. Use of a restricted number of tools (only biopsy forceps, standard cytology brush, and/or bronchoalveolar lavage) was compared with an extensive multimodal strategy (biopsy forceps, cytology brush, aspirating needle, triple needle cytology brush, needle-tipped cytology brush, core biopsy system, and bronchoalveolar lavage).

Results:

Of malignant cases, 86.8% (361/416) of true positive diagnoses were obtained using extensive multimodal strategies. ROSE was used in 300/416 cases. The finding of malignancy by ROSE reduced the total number of tools used. A malignant ROSE call was obtained in 71% (212/300), most (88.7%; 188/212) by the first tool used (49.5% with aspirating needle, 20.2% with cytology brush, 17.0% with forceps). True positive rates were highest for the biopsy forceps (86.9%) and aspirating needle (86.6%). Use of extensive tool strategies did not increase the rates of pneumothorax (5.5% restricted, 2.8% extensive) or bronchopulmonary hemorrhage (3.6% restricted, 1.1% extensive).

Conclusion:

These results suggest that extensive biopsy tool strategies, including the aspirating needle, may provide higher true positive rates for detecting lung cancer without increasing complications.

Key Words: aspiration biopsy, fine-needle, bronchoscopy, image-guided biopsy, lung neoplasms/diagnosis

Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (ENB) is an image-guided approach to access peripheral lung lesions and aid in the collection of biopsy samples. ENB can be used to guide bronchoscopic sampling tools such as forceps, aspiration needles, and cytology brushes through an extended working channel. The pooled diagnostic yield estimates of ENB have been reported at 65% to 74% in meta-analyses,1,2 with a pooled sensitivity of 77%.3 However, across individual studies, the diagnostic yield of ENB varies considerably, from 33% to 97%.4

Variation in diagnostic yield across ENB studies is dependent upon many factors. These may include computed tomography-to-body divergence,5 lesion size,6–10 lobar location,9–12 the presence of a bronchus sign,11,13 and the definition of diagnostic yield used.14,15 Operator and procedural factors may further impact outcomes, such as user experience,16 the use of rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE),11,17,18 and concurrent imaging.15,19–22 Previous studies suggest that the diagnostic yield of bronchoscopy, including conventional bronchoscopy,9,23,24 virtual bronchoscopic navigation,25,26 and ENB,20,27,28 may be related to the choice of biopsy tool. In particular, several studies have reported higher diagnostic yield with transbronchial needle aspiration than with transbronchial forceps biopsy or brushing.9,20,23,24,27 In addition, the use of a multitool strategy may be more effective than single-tool strategies.20,24,26,27 However, some operators may be concerned that use of the transbronchial needle could increase complication rates. The safety and relative accuracy of different biopsy tool strategies used in conjunction with ENB have yet to be examined in a large, prospective, multicenter study.

NAVIGATE is a prospective, multicenter study that evaluated ENB usage patterns, safety, and diagnostic yield across community and academic sites.29 Biopsy tool choice, tool order, ROSE use and outcomes, and pathology results by tool were prospectively captured. The objective of the current post-hoc analysis is to evaluate the usage patterns, relative accuracy, and safety of biopsy tool strategies used in NAVIGATE.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all local regulatory requirements. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of all participating sites. All subjects provided written informed consent.

NAVIGATE (NCT02410837) is a prospective, multicenter, single-arm, cohort study of ENB using the superDimension navigation system, versions 6.3 to 7.1 (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN).14,29–33 NAVIGATE enrolled consecutive adult subjects undergoing ENB procedures in a real-world design that imposed no restrictions nor suggestions on procedural technique or the use of complementary tools. However, unlike registry studies, NAVIGATE used standardized predefined endpoints and rigorous follow-up, with independent source-data verification in ∼25% of subjects.14 All follow-up diagnostic procedures and imaging were prospectively captured through 12 months after the ENB procedure, as previously described.14

The current post-hoc subgroup analysis includes subjects from the United States cohort with a true positive malignancy diagnosis in a single lung lesion as of 12-month follow-up. The true positive subset was chosen to provide a definitive data set of known malignant cases against which the relative efficacy of each biopsy strategy and individual biopsy tool could be evaluated. Inclusion of cases considered negative for malignancy at 12 months would have confounded the assessment of biopsy tool strategy since negative (nonmalignant) outcomes could have resulted from either inaccurate localization or inadequate sampling; therefore, the lack of a diagnostic outcome could not be attributed to any individual tool or strategy.

The aim of this analysis was to evaluate the usage patterns, accuracy, and safety of various biopsy tool strategies in NAVIGATE. We considered a more restricted “biopsy/brush/wash” strategy [including only the biopsy forceps, standard cytology brush, and/or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)/washing] and a more extensive multimodal strategy including a greater number of tools (biopsy forceps, standard cytology brush, aspirating needle, superDimension triple needle cytology brush, needle-tipped cytology brush, GenCut core biopsy system, BAL). The aspirating needle was included in the extensive set because, although many consider it to be standard-of-care, it is still widely underused even in expert centers (eg, in only 16% of cases in the AQuIRE registry).9

The accuracy of each individual tool was also evaluated against the final true positive malignant diagnosis. For each evaluated lung lesion, a malignant result based on the final pathology of the ENB-aided sample for any tool was considered a true positive result for that lesion (there were no false positives for malignancy). The pathology results for each individual tool were then evaluated against the overall malignant diagnosis. Any tool yielding only benign or inconclusive results was considered a false negative while any tool yielding at least one malignant result was considered a true positive. Lymph node biopsies were not included in the analysis.

Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). Data are summarized by descriptive statistics. The analyses were not prospectively powered to detect statistically significant differences. Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare lesion sizes and number of unique biopsy tools between the restricted and extensive groups.

RESULTS

Biopsy Tool Usage

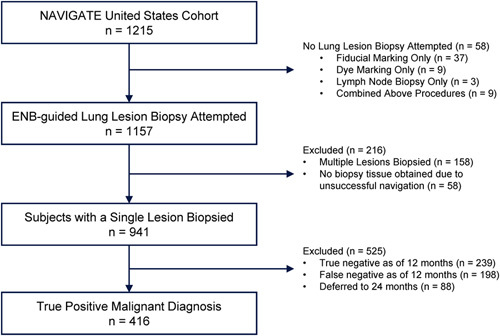

As of the 1-year analysis, the NAVIGATE US cohort enrolled 1215 consecutive subjects at 29 sites.14 The current subgroup analysis includes 416 subjects who underwent ENB-aided biopsy of a single lung lesion that was true positive for malignancy as of 12-month follow-up (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Analysis Set. The NAVIGATE US cohort enrolled 1215 consecutive subjects at 29 sites. The current subgroup analysis includes 416 subjects who underwent ENB-aided biopsy of a single lung lesion that was diagnosed as true positive for malignancy as of 12-month follow-up. ENB indicates electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy.

As shown in Table 1, most NAVIGATE patients were evaluated using extensive biopsy tool strategies; 86.8% (361/416) of true positive malignant diagnoses in NAVIGATE were obtained using extensive strategies. Only 13.2% (55/416) of true positive diagnoses were obtained using a restricted number of biopsy tools that included only biopsy forceps, cytology brush, and/or BAL/washing. Among the 29 sites included in the analysis, 28/29 sites contributed patients to the extensive group while 12/29 sites contributed patients to the restricted group. However, 19/55 (34.5%) patients in the restricted group came from a single site.

TABLE 1.

Lesion and Procedural Characteristics and Adverse Events

| Subjects Evaluated With a Restricted Number of Biopsy Tools | Subjects Evaluated With an Extensive Biopsy Tool Strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Tool* | 55/416 (13.2) | 361/416 (86.8) |

| Biopsy forceps | 44/55 (80.0) | 306/361 (84.8) |

| Cytology brush | 34/55 (61.8) | 164/361 (45.4) |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage/washing† | 19/55 (34.5) | 100/361 (27.7) |

| Aspirating needle | NA | 241/361 (66.8) |

| Triple needle cytology brush | NA | 99/361 (27.4) |

| Needle-tipped cytology brush | NA | 85/361 (23.5) |

| Core biopsy system | NA | 75/361 (20.8) |

| Restricted | Extensive | |

| Lesion and procedural characteristics | ||

| Lesion size (mm) | 17.0 (13-31) | 25.0 (18-36) |

| Lesions <20 mm | 33/55 (60.0) | 111/360 (30.8) |

| Upper lobe location | 29/55 (52.7) | 246/361 (68.1) |

| Lesion in peripheral third of lung‡ | 36/55 (65.5) | 218/361 (60.4) |

| Fluoroscopy used | 49/55 (89.1) | 331/361 (91.7) |

| Lesion visible on fluoroscopy | 33/49 (67.3) | 242/331 (73.1) |

| Bronchus sign present | 30/55 (54.5) | 238/361 (65.9) |

| Pure to mostly ground glass§ | 1/55 (1.8) | 9/360 (2.5) |

| General anesthesia used | 53/55 (96.4) | 273/361 (75.6) |

| Procedure-related adverse events | ||

| All pneumothorax | 3/55 (5.5) | 10/361 (2.8) |

| CTCAE grade ≥2∥ | 2/55 (3.6) | 4/361 (1.1) |

| All bronchopulmonary hemorrhage | 2/55 (3.6) | 4/361 (1.1) |

| CTCAE grade ≥2∥ | 2/55 (3.6) | 3/361 (0.8) |

| Aspirating needle not used | Aspirating needle used | |

| Procedure-related adverse events | ||

| All pneumothorax | 6/175 (3.4) | 7/241 (2.9) |

| CTCAE grade ≥2∥ | 2/175 (1.1) | 4/241 (1.7) |

| All bronchopulmonary hemorrhage | 4/175 (2.3) | 2/241 (0.8) |

| CTCAE grade ≥2∥ | 4/175 (2.3) | 1/241 (0.4) |

Data are presented as n/N (%) or median (Q1-Q3).

Multiple tools could be used in each subject. Represents all brands combined. Specific brands of tools used in the restricted group were the superDimension biopsy forceps in 80.0% (44/55), the superDimension cytology brush in 52.7% (29/55), and other cytology brushes in 12.7% (7/55). Specific brands of tools used in the “Extensive” group were the superDimension biopsy forceps in 80.6% (291/361), other biopsy forceps in 6.4% (23/361), the superDimension cytology brush in 38.2% (138/361), other cytology brushes in 8.3% (30/361), the superDimension aspirating needle in 65.1% (235/361), other aspirating needles in 1.9% (7/361), the superDimension triple needle cytology brush in 27.4% (99/361), the superDimension needle-tipped cytology brush in 17.5% (63/361), other needle-tipped cytology brushes in 6.1% (22/361), and the GenCut core biopsy system in 20.8% (75/361).

Bronchoalveolar lavage/washing is considered a “biopsy tool” for the purposes of this analysis only.

A lesion that is located in the outer third of the lung and difficult to reach by traditional bronchoscopy.29

Suzuki Class 1 or 2.

Requiring intervention (eg, chest tube) or hospitalization according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

A mean of 1.8±0.8 (range: 1 to 3) unique biopsy tools was used in the restricted group versus 3.0±1.0 (range: 1 to 6) in the extensive group (P<0.001). As shown in Table 1, lesions evaluated with a restricted number of biopsy tools tended to be smaller (60% <20 mm) than those evaluated with extensive strategies (31% <20 mm, P<0.001).

ROSE Usage

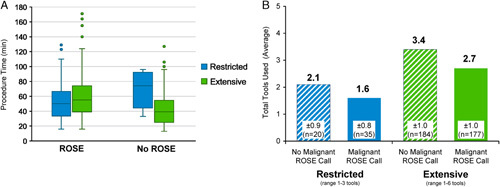

ROSE was available in 300/416 cases overall, including 89.1% (49/55) and 69.5% (251/361) of subjects in the restricted and extensive groups, respectively. The use of an extensive biopsy tool strategy did not increase the overall procedure time, regardless of whether ROSE was used (Fig. 2A). Of the subjects with ROSE available, a malignant call was obtained by ROSE (by any tool) in 212 out of 300 subjects, representing an overall concordance of ROSE with final pathology of 71%.

FIGURE 2.

Procedure Time and ROSE Usage. ROSE was available in 72.1% (300/416) of cases overall. A, The use of an extensive biopsy tool strategy did not increase the overall procedure time, regardless of whether ROSE was used. The overall median procedure time (bronchoscope in to bronchoscope out) was 50 minutes. B, Finding of malignancy by ROSE reduced the mean total number of tools used compared with cases without a malignant ROSE call. Among all 416 subjects included in the analysis, a mean of 2.9±1.1 biopsy tools were used (range: 1 to 6 tools). ROSE indicates rapid on-site evaluation.

In cases with ROSE available, a malignant call was obtained based on a sample from the first tool used in 88.7% (188/212). Operators continued to use additional tools after the first malignant ROSE call in 81.9% (154/188) of cases, including 45.5% of cases with 1 additional tool used, 33.8% with 2 additional tools used, 18.8% with 3 additional tools used, 1.3% with 4 additional tools used, and 0.6% with 5 additional tools used. However, it should be noted that some operators continued biopsies as ROSE samples were being evaluated such that the malignant ROSE call may not have been communicated to the operator until the second or third biopsy tool was in progress. The finding of malignancy by ROSE did reduce the mean total number of tools used compared to cases without a malignant ROSE call (Fig. 2B). All 212 cases with a malignant ROSE call achieved that malignant call within the first 3 tools attempted.

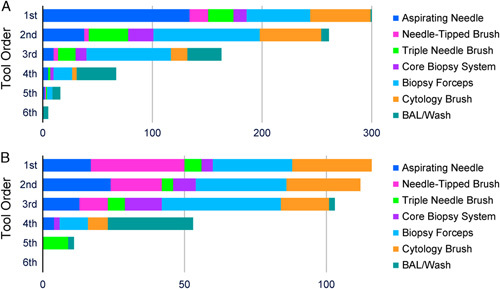

Biopsy Tool Order and Operator Decision Patterns

Biopsy tool order is shown in Figure 3. In cases in which ROSE was available (n=300), the aspirating needle was most commonly the first tool used [44.7% (134/300)], followed by the biopsy forceps [19.3% (58/300)] and the cytology brush [18.3% (55/300); Fig. 3A]. When a malignant ROSE call was obtained by the first tool used (188/300 cases), that tool was most commonly the aspirating needle [49.5% (93/188)] followed by the cytology brush [20.2% (38/188)] and the biopsy forceps [17.0% (32/188)].

FIGURE 3.

Biopsy tool order. Tool order in subjects with rapid on-site evaluation available (A, n=300) and subjects without rapid on-site evaluation available (B, n=116). BAL indicates bronchoalveolar lavage.

As shown in Figure 3B, in cases without ROSE available (n=116), the biopsy forceps, cytology brush, and needle-tipped brush were most commonly used first, with approximately equal frequencies (24.1%, 24.1%, and 28.4%, respectively).

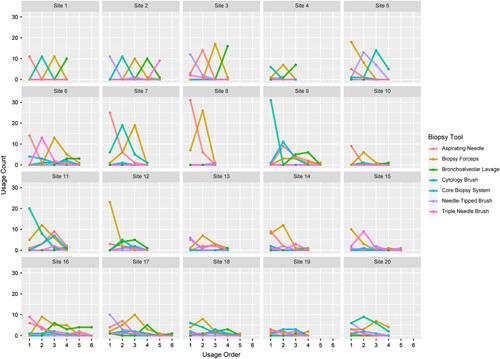

Site-specific biopsy tool usage trends in sites enrolling 25 or more subjects are shown in Figure 4. A wide variety of tools strategies can be seen among the individual NAVIGATE sites. Some sites used the same tools in the same order for every case (as exemplified by the top row of Fig. 4), while other sites used more varied patterns (as exemplified by the bottom row).

FIGURE 4.

Site-specific tool usage. Trending plots in sites enrolling 25 or more subjects, showing the first, second, third, etc., tools used in each case across the x-axis and subject count on the y-axis. Consistently peaked patterns indicate that the same tools were used in the same order for every subject. For example, site 1 used the aspirating needle first, the cytology brush second, and the biopsy forceps third in all 11 subjects that site contributed to the analysis set. In contrast, a more varied pattern was used in site 16, with the first tool being the triple needle cytology brush in 53% of cases, the aspirating needle in 35%, the cytology brush in 6%, and the needle-tipped brush in 6%.

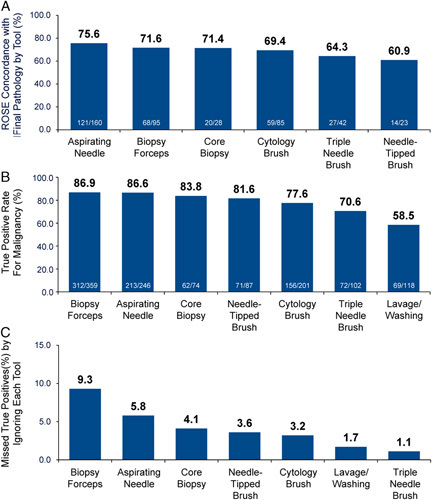

Biopsy Tool Accuracy

By design, all lesions included in this analysis were ultimately proven to be positive for malignancy based on final pathology results of the ENB-aided sample. The true positive rates of each individual tool by ROSE and final pathology are shown in Figure 5. Either the aspirating needle or the biopsy forceps were used in 392/416 subjects and 1 or both of those tools obtained a malignant result in 92.9% of cases (364/392), although not exclusively. The aspirating needle and biopsy forceps had the highest concordance rate between ROSE and final pathology (Fig. 5A) and the highest true positive rates (Fig. 5B). True positive rates by biopsy tool did not significantly differ based on lesion size or lobe location, with the exception of lower true positive rates for lavage/washing in lesions <20 mm [42.9% (15/35)] versus lesions ≥20 mm [65.1% (54/83), P=0.04]. There was a trend toward lower true positive rates in lesions <20 mm for the core biopsy system [76.5% (13/17) vs. 86.0% (49/57)] and the needle-tipped brush [72.7% (16/22) vs. 84.4% (54/64)] and in upper lobe versus lower lobe lesions for the triple needle brush [58.3% (21/36) vs. 77.3% (51/66)]. To assess the relative contribution that each individual tool had on the efficacy of the multimodal strategy, an analysis was conducted in which each tool was “ignored” in the analysis in turn (Fig. 5C). Within the multimodal strategy, the tools that had the greatest impact on outcomes were the biopsy forceps and the aspirating needle: the true positive rate was increased by 9.3% by adding the biopsy forceps to the tool strategy and by 5.8% by adding the aspiration needle. Removing both the biopsy forceps and the aspiration needle from the multimodal strategy would have reduced the true positive rate by 13.5%. The impact of other tools is shown in Figure 5C. In cases with a malignant diagnosis missed by both the biopsy forceps and the aspirating needle, 17.9% (5/28) were ultimately obtained by the standard cytology brush alone, 3.6% (1/28) by the triple needle brush alone, 10.7% (3/28) by the needle-tipped brush alone, 7.1% (2/28) by the core biopsy system alone, 7.1% (2/28) by washing alone, and the remainder by a combination of the nonforceps/non-needle methods.

FIGURE 5.

Individual tool results. ROSE concordance (A) and true positive rates (B) for individual tools. By design, all lesions included in this analysis were ultimately proven to be positive for malignancy based on final pathology results of the ENB-aided sample. Any individual tool yielding only benign or inconclusive results was considered a false negative while any tool yielding at least one malignant result was considered a true positive. C, Individual impact of each individual tool on multimodality success. Among all 416 subjects with single lesions ultimately proven to be true positive for malignancy, this analysis examines the impact of “ignoring” each tool in turn within the analysis. For example, if only the biopsy forceps yielded a malignant result and all other tools yielded negative results, the overall result for that case would be considered negative when the biopsy tool was ignored in the analysis. The impact of ignoring each tool in turn is shown. For example, within the context of the multimodality sampling strategy, if the biopsy forceps had not been used, 9.3% of true positive malignant cases would have been missed (or in other words, adding biopsy forceps to the tool strategy increased the true positive rate by 9.3%). ROSE indicates rapid on-site evaluation.

Complications

Procedure-related adverse events are shown in Table 1. Use of an extensive number of biopsy tools or use of the aspiration needle did not increase complication rates. No differences were observed based on individual tools used; however, since >1 tool was used in most patients it is difficult to ascribe adverse events to any individual tool.

DISCUSSION

This NAVIGATE post-hoc analysis suggests that extensive biopsy strategies were favored by US investigators and yielded the majority of true positive diagnoses. These observations are consistent with a meta-analysis of 40 ENB studies in which the sensitivity for malignancy significantly increased with the number of biopsy tools used, levelling off after 4 sampling tools.3 Within the multimodal strategy, the aspirating needle and biopsy forceps had the highest true positive rates and the greatest impact in our analysis. However, malignant diagnoses were missed by both the forceps and the needle in a small proportion of cases and instead obtained by the cytology brushes, the core biopsy system, washing, or some combination of these lesser-used tools.

Use of extensive biopsy tool strategies, including use of the aspirating needle, did not increase complication rates. These results are consistent with prior reports of improved diagnostic yield using the aspirating needle compared with other transbronchial methods.16–18,27,28 The AQuIRE registry reported that the aspiration needle improved diagnostic yield compared with transbronchial brushing, forceps biopsy, or lavage.9 Use of needle aspiration in only 16% of AQuIRE subjects may have contributed to the overall low rate of ENB-aided diagnostic yield in that study.34 The choice to put the aspirating needle in the restricted group may be questioned by those who consider this tool standard-of-care. However, multiple published papers have reported low use of the aspirating needle, even in expert centers.9,19,35,36 That disparity in the context of higher reported diagnostic yield with the aspiration needle was one of the driving forces of the current analysis.

There are many factors that influence biopsy tool choice beyond the anticipated efficacy of any individual tool. Usage patterns and market availability will be different in other countries compared with this US analysis. Within the United States, reimbursement advantages may influence the choice to use the aspirating needle. There is also a reimbursement benefit to using >1 tool,37 particularly the combination of aspirating needle, biopsy forceps, and cytology brush. Conversely, the cost of these additional instruments maybe a limiting factor in the decision to use them absent clear benefit. Nonetheless, while market availability and reimbursement factors may impact the choice of biopsy tools used, the current analysis suggests that the biopsy forceps and the aspirating needle provided the highest true positive rate and together had the largest positive impact on the overall multimodal strategy.

The use of ROSE impacted the number of tools required and the order of tools; however, with no differences in safety or procedure time, the clinical relevance of that finding may be limited. ROSE was concordant with final pathology in only 71% of cases. This supports the perception that many providers use ROSE as an assessment of tissue adequacy rather than as a diagnostic tool, although other studies have found higher ROSE concordance rates38–40 and many factors may affect ROSE usage and efficacy. Use of ROSE was not a significant predictor of increased diagnostic yield for peripheral pulmonary lesions in NAVIGATE (78.6% with ROSE vs. 75.8% without ROSE).14 Similarly, a meta-analysis of transbronchial needle aspiration in mediastinal lymph nodes found no impact of ROSE on diagnostic yield, although it did reduce the number of needle passes and the number of additional bronchoscopic procedures.41 In contrast, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 bronchoscopy studies reported significantly higher diagnostic yield when ROSE was used, particularly in lesions ≤2 cm, for all guidance modalities (fluoroscopy, endobronchial ultrasound, and ENB).42 In the current study, the order of tools also differed depending on whether ROSE was used. When ROSE was available, the aspirating needle was most commonly the first tool used and yielded the first malignant ROSE call in nearly 50% of cases. Without ROSE, the biopsy forceps, cytology brush, and needle-tipped brush were more commonly used first. Again, choice of the aspirating needle for ROSE may be institution specific based on factors beyond expected efficacy. Strategies with regard to ROSE vary widely depending on resource availability and workflow; this variation is reflected in the real-world NAVIGATE data set and the overall low concordance of ROSE with final pathology.

Regardless of the biopsy tool strategy or number of tools used, this analysis supports the low complication rates of ENB. Up to 6 unique biopsy tools could be used in each subject, with many subjects undergoing biopsy sampling with the same tool multiple times. Use of the aspirating needle and multiple biopsy tools are sometimes avoided because of the perception that more aggressive biopsy strategies may increase the risk of complications. In contrast, this analysis found no increase in complication rates with either an extensive strategy overall, nor with the aspirating needle in particular. Pneumothorax and bronchopulmonary hemorrhage rates were lower than reported for transthoracic aspirating needle biopsy (18.8% pneumothorax, 4.3% with chest tube, 6.4% pulmonary hemorrhage).43 Selection bias may have occurred in this analysis if operators chose to use multiple tools only when the perceived risk of complications was low (eg, lesions that were more central, larger, or more dense, or those with better localization with ultrasound). Nonetheless, this analysis provides increased confidence to operators wishing to use more extensive tool strategies to increase the chance of diagnostic success.

While this analysis supports the use of extensive biopsy strategies with multiple tools, including the aspiration needle, several questions remain unanswered. First, because of the variety and number of strategies used among NAVIGATE investigators, we are unable offer a conclusive recommendation regarding the specific order or number of passes of biopsy tools. Institutional standards, pathologist preferences, ROSE availability, commercial availability, and reimbursement factors all have a broad and significant influence on biopsy tool choice. Outcomes in the extensive group were largely driven by the biopsy forceps and aspirating needle; specialized tools used with lower frequency had a more limited contribution and thus must be interpreted with caution. Second, because molecular testing was attempted in only 31% of NAVIGATE subjects with adenocarcinoma or non–small cell lung cancer not otherwise specified14 and tool-specific adequacy for molecular testing was not captured, this analysis does not inform the most appropriate tool for molecular analysis. The increasing requirement for biomolecular status and need for larger tissue samples for molecular analysis will impact tool choices and could partially explain why additional tools were used after the first malignant ROSE call in 82% of cases. Third, the optimal biopsy tool strategy for ground glass opacities could not be examined because of the underrepresentation of ground glass opacities in NAVIGATE. Finally, additional studies will be needed to examine the impact of tool strategy on cost-effectiveness.

Limitations

This was a retrospective post-hoc analysis of a prospective single-arm cohort study, and therefore was not designed to assess statistical significance between comparison groups. This analysis was also limited to the United States and may not be applicable to other regions. The disparity in the number of centers contributing patients to the extensive and restricted groups, as well as the preponderance of restricted group patients from a single site, may have influenced the results. The use of multiple biopsy tools in each subject precludes a specific analysis of complication rates and outcomes associated with individual tools. The statistically significant difference in median lesion size between the restricted and extensive groups may impact the ability to compare those groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this post-hoc analysis suggest that extensive biopsy tool strategies, including the aspirating needle, may provide higher true positive rates without increasing complications. While the biopsy forceps and aspirating needle have the greatest impact, a greater number and variety of tools may further improve outcomes. However, future studies are needed to prospectively assess the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of individual biopsy tools.

Footnotes

Present address: Gregory P. LeMense, MD, Bozeman Health Pulmonary Medicine, Bozeman, MT.

Presented at the CHEST annual meeting in New Orleans, LA on October 23, 2019 (Gildea et al, CHEST. 2019;156:A827–A829).

Study sponsored and funded by Medtronic. All authors (or their institutions) received research grant support from Medtronic to conduct this study. Biostatistical analysis was provided by Haiying Lin of Medtronic. Medical writing support was provided by Kristin L. Hood, PhD of Medtronic in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and under full direction of the authors.

Disclosure: Dr E.E.F. reports consultant fees from Medtronic and Boston Scientific, and a research grant from Intuitive Surgical. Dr T.R.G. reports travel funds from Medtronic. Dr S.J.K. reports consultant fees from Medtronic. Dr G.P.L. reports consultant fees from Medtronic. H.L. and Dr J.S.M. are full-time employees of Medtronic. Dr A.K.M. reports consultant fees from Medtronic. Dr M.A.P. reports speaking, consulting, or research payments from Medtronic, Auris Health, BodyVision, Intuitive Surgical, Philips, Biodesix, AstraZeneca, Johnson and Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, United Therapeutics, Actelion, Inivata, and Boston Scientific. Dr O.B.R. reports consultant fees from Medtronic. Dr J.S. reports consultant fees from Somnoware Sleep Solutions. For the remaining authors there is no conflict of interest or other disclosures.

Contributor Information

Thomas R. Gildea, Email: gildeat@ccf.org.

Erik E. Folch, Email: efolch@mgh.harvard.edu.

Sandeep J. Khandhar, Email: sandeep.khandhar@usoncology.com.

Michael A. Pritchett, Email: mpritchett@pinehurstmedical.com.

Gregory P. LeMense, Email: glemense@gmail.com.

Philip A. Linden, Email: Philip.Linden@UHhospitals.org.

Douglas A. Arenberg, Email: darenber@med.umich.edu.

Otis B. Rickman, Email: otis.rickman@vumc.org.

Amit K. Mahajan, Email: bmahaj@gmail.com.

Jaspal Singh, Email: Jaspal.Singh@atriumhealth.org.

Joseph Cicenia, Email: cicenij@ccf.org.

Atul C. Mehta, Email: mehtaa1@ccf.org.

Jennifer S. Mattingley, Email: jen.s.mattingley@medtronic.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gex G, Pralong JA, Combescure C, et al. Diagnostic yield and safety of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy for lung nodules: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respiration. 2014;87:165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGuire AL, Myers R, Grant K, et al. The diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity for malignancy of radial-endobronchial ultrasound and electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy for sampling of peripheral pulmonary lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2020;27:106–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Folch EE, Labarca G, Ospina-Delgado D, et al. Sensitivity and safety of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy for lung cancer diagnosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2020;158:1753–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehta AC, Hood KL, Schwarz Y, et al. The evolutional history of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy: state of the art. Chest. 2018;154:935–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pritchett MA, Bhadra K, Calcutt M, et al. Virtual or reality: divergence between preprocedural computed tomography scans and lung anatomy during guided bronchoscopy. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:1595–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bertoletti L, Robert A, Cottier M, et al. Accuracy and feasibility of electromagnetic navigated bronchoscopy under nitrous oxide sedation for pulmonary peripheral opacities: an outpatient study. Respiration. 2009;78:293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bowling MR, Kohan MW, Walker P, et al. The effect of general anesthesia versus intravenous sedation on diagnostic yield and success in electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2015;22:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jensen KW, Hsia DW, Seijo LM, et al. Multicenter experience with electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of pulmonary nodules. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2012;19:195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ost DE, Ernst A, Lei X, et al. Diagnostic yield and complications of bronchoscopy for peripheral lung lesions. Results of the AQuIRE Registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:68–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahajan AK, Patel S, Hogarth DK, et al. Electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy: an effective and safe approach to diagnose peripheral lung lesions unreachable by conventional bronchoscopy in high-risk patients. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2011;18:133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Balbo PE, Bodini BD, Patrucco F, et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy and rapid on site evaluation added to fluoroscopy-guided assisted bronchoscopy and rapid on site evaluation: improved yield in pulmonary nodules. Minerva Chir. 2013;68:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eberhardt R, Anantham D, Herth F, et al. Electromagnetic navigation diagnostic bronchoscopy in peripheral lung lesions. Chest. 2007;131:1800–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seijo LM, de Torres JP, Lozano MD, et al. Diagnostic yield of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy is highly dependent on the presence of a bronchus sign on CT imaging: results from a prospective study. Chest. 2010;138:1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Folch EE, Pritchett MA, Nead MA, et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy for peripheral pulmonary lesions: one-year results of the prospective, multicenter NAVIGATE study. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aboudara M, Roller L, Rickman O, et al. Improved diagnostic yield for lung nodules with digital tomosynthesis-corrected navigational bronchoscopy: initial experience with a novel adjunct. Respirology. 2020;25:206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lamprecht B, Porsch P, Wegleitner B, et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (ENB): increasing diagnostic yield. Respir Med. 2012;106:710–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karnak D, Ciledag A, Ceyhan K, et al. Rapid on-site evaluation and low registration error enhance the success of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy. Ann Thorac Med. 2013;8:28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loo FL, Halligan AM, Port JL, et al. The emerging technique of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy-guided fine-needle aspiration of peripheral lung lesions: promising results in 50 lesions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eberhardt R, Anantham D, Ernst A, et al. Multimodality bronchoscopic diagnosis of peripheral lung lesions: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eberhardt R, Morgan RK, Ernst A, et al. Comparison of suction catheter versus forceps biopsy for sampling of solitary pulmonary nodules guided by electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy. Respiration. 2010;79:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pritchett MA, Schampaert S, de Groot JAH, et al. Cone-beam CT with augmented fluoroscopy combined with electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy for biopsy of pulmonary nodules. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2018;25:274–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pritchett MA, Bhadra K, Mattingley JS. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy with tomosynthesis-based visualization and positional correction: three-dimensional accuracy as confirmed by cone-beam computed tomography. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2020. Doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schreiber G, McCrory DC. Performance characteristics of different modalities for diagnosis of suspected lung cancer: summary of published evidence. Chest. 2003;123:115S–128S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Franke KJ, Hein M, Domanski U, et al. Transbronchial catheter aspiration and transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnostic workup of peripheral lung lesions. Lung. 2015;193:767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Asano F, Shinagawa N, Ishida T, et al. Virtual bronchoscopic navigation combined with ultrathin bronchoscopy. A randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Asahina H, Yamazaki K, Onodera Y, et al. Transbronchial biopsy using endobronchial ultrasonography with a guide sheath and virtual bronchoscopic navigation. Chest. 2005;128:1761–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Odronic SI, Gildea TR, Chute DJ. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy-guided fine needle aspiration for the diagnosis of lung lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Copeland S, Kambali S, Berdine G, et al. Electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules. Southwest Resp Crit Care Chron. 2017;5:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Folch EE, Bowling MR, Gildea TR, et al. Design of a prospective, multicenter, global, cohort study of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khandhar SJ, Bowling MR, Flandes J, et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy to access lung lesions in 1,000 subjects: first results of the prospective, multicenter NAVIGATE study. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bowling MR, Folch EE, Khandhar SJ, et al. Pleural dye marking of lung nodules by electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy. Clin Respir J. 2019;13:700–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bowling MR, Folch EE, Khandhar SJ, et al. Fiducial marker placement with electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy: a subgroup analysis of the prospective, multicenter NAVIGATE study. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2019;13:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Towe CW, Nead MA, Rickman OB, et al. Safety of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy in patients with COPD: results from the NAVIGATE study. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2019;26:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Patrucco F, Gavelli F, Daverio M, et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy: where are we now? Five years of a single-center experience. Lung. 2018;196:721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makris D, Scherpereel A, Leroy S, et al. Electromagnetic navigation diagnostic bronchoscopy for small peripheral lung lesions. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1187–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andersen FD, Degn KB, Riis, Rasmussen T. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy for lung nodule evaluation. Patient selection, diagnostic variables and safety. Clin Respir J. 2020;14:557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Manual System Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing. 2012. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R2333CP.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2020.

- 38. Rokadia HK, Mehta A, Culver DA, et al. Rapid on-site evaluation in detection of granulomas in the mediastinal lymph nodes. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang J, Zhao Y, Chen Q, et al. Diagnostic value of rapid on-site evaluation during transbronchial biopsy for peripheral lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2019;49:501–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lamprecht B, Porsch P, Pirich C, et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy in combination with PET-CT and rapid on-site cytopathologic examination for diagnosis of peripheral lung lesions. Lung. 2009;187:55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, et al. Impact of rapid on-site cytological evaluation (ROSE) on the diagnostic yield of transbronchial needle aspiration during mediastinal lymph node sampling: systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2018;153:929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yuan M-L, Yang X, Yin W, et al. The effectiveness of rapid on-site cytological evaluation (ROSE) on the diagnostic yield of bronchoscopy in peripheral pulmonary lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2019;12:3283–3293. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heerink WJ, de Bock GH, de Jonge GJ, et al. Complication rates of CT-guided transthoracic lung biopsy: meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]