Abstract

Background

Health inequities remain a public health concern. Chronic adversity such as discrimination or racism as trauma may perpetuate health inequities in marginalized populations. There is a growing body of the literature on trauma informed and culturally competent care as essential elements of promoting health equity, yet no prior review has systematically addressed trauma informed interventions. The purpose of this study was to appraise the types, setting, scope, and delivery of trauma informed interventions and associated outcomes.

Methods

We performed database searches— PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SCOPUS and PsycINFO—to identify quantitative studies published in English before June 2019. Thirty-two unique studies with one companion article met the eligibility criteria.

Results

More than half of the 32 studies were randomized controlled trials (n = 19). Thirteen studies were conducted in the United States. Child abuse, domestic violence, or sexual assault were the most common types of trauma addressed (n = 16). While the interventions were largely focused on reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 23), depression (n = 16), or anxiety (n = 10), trauma informed interventions were mostly delivered in an outpatient setting (n = 20) by medical professionals (n = 21). Two most frequently used interventions were eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (n = 6) and cognitive behavioral therapy (n = 5). Intervention fidelity was addressed in 16 studies. Trauma informed interventions significantly reduced PTSD symptoms in 11 of 23 studies. Fifteen studies found improvements in three main psychological outcomes including PTSD symptoms (11 of 23), depression (9 of 16), and anxiety (5 of 10). Cognitive behavioral therapy consistently improved a wide range of outcomes including depression, anxiety, emotional dysregulation, interpersonal problems, and risky behaviors (n = 5).

Conclusions

There is inconsistent evidence to support trauma informed interventions as an effective approach for psychological outcomes. Future trauma informed intervention should be expanded in scope to address a wide range of trauma types such as racism and discrimination. Additionally, a wider range of trauma outcomes should be studied.

Background

Despite the United States’ commitment to health equity, health inequities remain a pressing concern among some of the nation’s marginalized populations, such as racial/ethnic or gender minority populations. For example, according to the 2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 29.1% of Mexican Americans and 24.3% of African Americans with diabetes had hemoglobin A1C greater than 9% (the gold standard of glucose control with levels ≤ 7% deemed adequate), compared to 11% in non-Hispanic whites [1]. The 2016 survey also revealed that 40.9% and 41.5% of Mexican Americans and African Americans with hypertension, respectively, had their blood pressure under control, compared to 51.7% in non-Hispanic whites. In 2014, 83% of all new diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States occurred among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, with African American men having the highest rates [2].

Several factors have been discussed as root causes of health inequities. For example, Farmer et al. [3] noted structural violence—the disadvantage and suffering that stems from the creation and perpetuation of structures, policies and institutional practices that are innately unjust—as a major determinant of health inequities. According to Farmer et al., because systemic exclusion and disadvantage are built into everyday social patterns and institutional processes, structural violence creates the conditions which sustain the proliferation of health and social inequities. For example, a recent analysis [4] using a sample including 4,515 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants between 35 and 64 years of age revealed that black men and women had fewer years of education, were less likely to have health insurance, and had higher allostatic load (i.e., accumulation of physiological perturbations as a result of repeated or chronic stressors such as daily racial discrimination) compared to white men (2.5 vs 2.1, p<.01) and women (2.6 vs 1.9, p<.01). In the analysis, allostatic load burden was associated with higher cardiovascular and diabetes-related mortality among blacks, independent of socioeconomic status and health behaviors.

Browne et al. [5] identified essential elements of promoting health equity in marginalized populations such as trauma-informed and culturally competent care. In particular, trauma-informed care is increasingly getting closer attention and has been studied in a variety of contexts such as addiction treatment [6–8] and inpatient psychiatric care [9]. While there is a growing body of the literature on trauma-informed care, no prior review has systematically addressed trauma-informed interventions; one published review of literature [10] limited its scope to trauma survivors in physical healthcare settings. As such, the purpose of this paper is to conduct a systematic review and synthesize evidence on trauma-informed interventions.

For the purpose of this paper, we defined trauma as physical and psychological experiences that are distressing, emotionally painful, and stressful and can result from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances” such as a natural disaster, physical or sexual abuse, or chronic adversity (e.g., discrimination, racism, oppression, poverty) [11,12]. We aim to: 1) describe the types, setting, scope, and delivery of trauma informed interventions and 2) evaluate the study findings on outcomes in association with trauma informed interventions in order to identify gaps and areas for future research.

Methods

Five electronic databases—PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), SCOPUS and PsycINFO—were searched from the inception of the databases to identify relevant quantitative studies published in English. The initial literature search was conducted in January 2018 and updated in June 2019 using the same search strategy.

Review design

We conducted a systematic review of quantitative evidence to evaluate the effects of trauma informed interventions. Due to heterogeneity relative to study outcomes, designs, and statistical analyses approaches among the included studies, we qualitatively synthesized the study findings. Three trained research assistants extracted study data. Specifically, we used the PICO framework to extract and organize key study information. The PICO framework offers a structure to address the following questions for study evidence [13]: Patient problem or population (i.e., patient characteristics or condition); Intervention (type of intervention tested or implemented); Comparison or control (comparison treatment or control condition, if any), and Outcome (effects resulting from the intervention).

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria

Articles were screened for their relevance to the purpose of the review. Articles were included in this review if the study was: about trauma informed approach (i.e., an approach to address the needs of people who have experienced trauma) or an aspect of this approach, published in English language and involved participants who were 18 years and older. Also, only quantitative studies conducted within a primary care or community setting were included.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were: studies in or with military populations, refugee or war-related trauma populations, studies with mental health experts and clinicians as research subjects or studies of incarcerated and inpatient populations. Conference abstracts that had limited information on study characteristics were also excluded.

Search strategy and selection of studies

Search strategy

Following consultation with a health science librarian, peer-reviewed articles were searched in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SCOPUS and PsycINFO using MeSH and Boolean search techniques. Search terms included: "trauma focused" OR "trauma-focused" OR "trauma informed" OR "trauma-informed." We also searched for the term trauma within three words of informed or focus ((trauma W/3 informed) OR (trauma W/3 focused), or (traumaN3 (focused OR informed)). Detailed search terms for each database are provided in Appendix 1.

Study selection

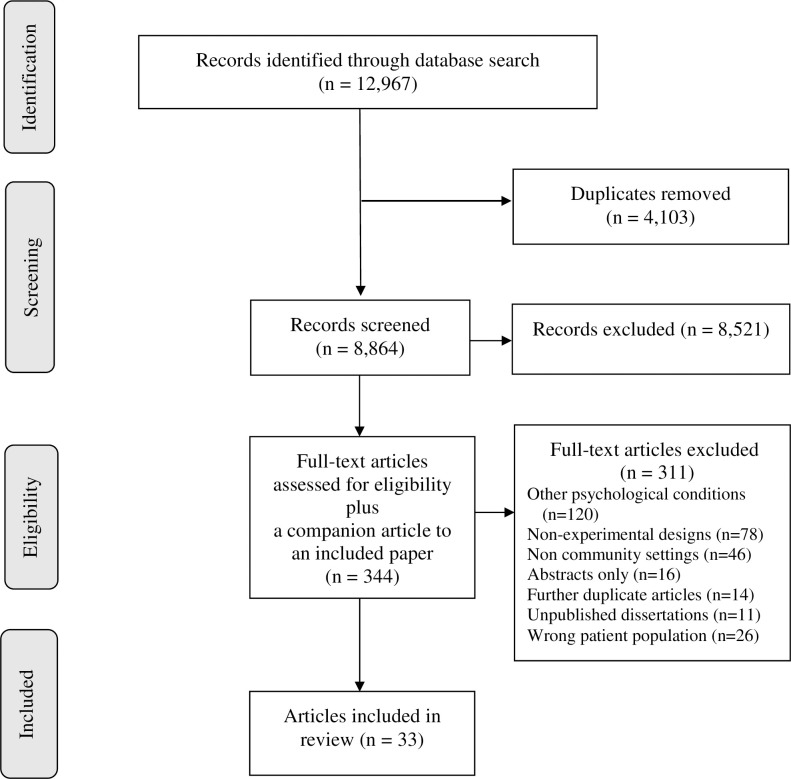

The initial electronic search yielded 7,760 references and the follow-up search yielded 5,207 which were all imported into the Covidence software for screening [14]. Screening of the references was conducted by 2 independent reviewers and disagreements were resolved through consensus. There were 4,103 duplicates removed from the imported articles and 8,864 studies were forwarded to the title and abstract screening stage. Eight thousand five hundred and twenty-one studies were excluded because they were irrelevant. Three hundred and forty-three abstracts were identified to be read fully. Following this, 311 articles were excluded for focusing on other psychological conditions (n = 120), were non-experimental studies (n = 78) and were in inpatient or incarcerated populations (n = 46). One additional companion article was identified during full text review. Therefore, thirty-three articles met the inclusion criteria and are reported in this review. Fig 1 provides details of the selection process and identifies the reasons why articles were excluded at each stage.

Fig 1. PRISMA diagram of a review of trauma-informed interventions.

Quality assessment

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute quality appraisal tools [15] for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, and retrospective studies to assess the rigor of each study included in this review. The Joanna Briggs Institute quality appraisal tools [15] include items asking about methodological elements that are critical to the rigor of each type of study designs. In particular, one of the items for RCTs addresses participant blinding to treatment assignment. Due to the nature of trauma-informed interventions included in our review, it was decided that participant blinding is not relevant and hence was removed from the appraisal list for RCTs. No studies were excluded on the basis of the quality assessment. The quality assessment process was conducted independently by two raters. Inter-rater agreement rates ranged from 56% to 100% with the resulting statistic indicating substantial agreement (average inter-rater agreement rate = 77%). Discrepancies between raters were resolved via inter-rater discussion.

Results

Overview of studies

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the 32 unique studies included in the review, with one companion article [16] for a study which was later reported with a more thorough examination of findings [17] totaling 33 articles. More than half (n = 19) of the 32 studies were RCTs [17–35] whereas twelve studies were quasi-experimental [36–47] and one was retrospective study [48]. Thirteen studies were conducted in the U.S. [17–19,22,26,27,29,35,39–41,45,47]; five in the Netherlands [30,31,33,38,48]; three in Canada [23,25,46]; two in Australia [21,24]; two in the United Kingdom [36,44]; two in Sweden [42,43]; on study in Chile [20]; Iran [32]; Haiti [37]; South Africa [34]; and Germany [28]. Fourteen of the studies only included females in their sample [18,20,21,23–25,27,28,38–41,45,48]. The average sample size was 78 participants, with a range from 10 participants [38] to 297 participants [48]. Of the studies included, 67% had a sample size above 50 [18–22,26,29–34,36,37,39–42,46–48].

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the review.

| 1st author (yr)[ref]/country | Purpose | Research design/Data points | Sample | Measurement of Trauma |

Main outcomes/Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beaumont (2016)[44]/United Kingdom | Investigate the effectiveness of using compassion focused therapy in reducing symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression and increasing self-compassion in fire service personnel | Quasi experimental, a 2×2 mixed-group design with repeated measures/Pre and post intervention | Fire service personnel suffering from PTSD (N = 17; 29% female) | Not directly measured | PTSD symptoms, self-compassion, anxiety and depression/Impact of Events Scale, Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| Booshehri (2018) [18]/United States | Test effectiveness of financial empowerment combined with trauma-informed peer support against standard Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) programming | RCT/Baseline and follow-up surveys every 3 months over 15 months | Primary caregivers of young children (<6 yrs) and receiving TANF (financial assistance and working at least 20 hours weekly) (N = 103) | Adverse Childhood Experiences and community violence | Family behavioral health, depression, self-efficacy, child’s developmental risks, economic hardship, labor market outcomes/Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression scale, General Self-Efficacy, Parent’s Evaluation of Developmental Status Scale, US Household Food Security Survey Module, Self-reported employment status and hourly earnings |

| Bowland (2012)[35]/United States | Evaluate the effectiveness of an 11-session, spiritually focused group intervention with older women survivors of interpersonal trauma | RCT/Baseline, at the end of the 11-week intervention, and 3-month follow up | Females age of 55 and older (N = 43) | Self-reported history of ≥ 1 interpersonal traumatic event (child abuse, sexual assault, or domestic violence) | PTSD symptoms, depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms/Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Patient Health Questionnaire |

| Bryant (2008)[21]/Australia | Determine the efficacy of exposure therapy or trauma-focused cognitive restructuring in preventing chronic PTSD relative to a wait-list control group | RCT/Baseline, immediately post-intervention and 6 months | Trauma survivors (non-sexual or vehicle) meeting diagnostic criteria for Acute Stress Disorder (N = 90) | Not directly measured | Symptoms of acute stress disorder, PTSD, and other psychopathological assessments/Acute Stress Disorder Interview, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale-2, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, Impact of Event Scale, Posttraumatic Cognition Inventory |

| Classen (2011)[26]/United States | Compare trauma-focused group psychotherapy with present focused group psychotherapy and a waitlist condition | RCT/Baseline, immediately post-intervention and 6 months | Females with PTSD as a result of childhood sexual abuse (N = 166) | ≥ 1 explicit memory of childhood sexual abuse involving genital or anal contact between ages 4-17 | PTSD symptoms, total HIV risk, sexual victimization experiences, interpersonal problems/PTSD Checklist—Specific, Sexual Experiences Survey, Drug and Alcohol Use Interview, and Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-32, Trauma Symptom Inventory, Posttraumatic Growth Inventory |

| Dalton (2013)[23]/Canada | Examine the impact of emotionally focused therapy on relationship distress in couples in which the female partner had a history of childhood abuse | RCT/Pre and post intervention | Heterosexual couples experiencing clinically significant marital stress (N = 32) | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule | Relationship satisfaction, Therapeutic alliance, Trauma symptoms, childhood trauma symptoms, PTSD symptoms, dissociative experiences/Dyadic Adjustment Scale, Couple Therapeutic Alliance Scale, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule, Trauma Symptom Inventory, Dissociative Experience Scale, Couple Therapeutic Alliance Scale |

| D’Andrea (2012)[45]/United States | Examine the relationship between trauma-focused psychotherapy processes in real-world therapies with complex trauma survivors | Quasi experimental/Pre and post intervention | Females with intimate partner violence (IPV) (N = 27) | Trauma History Questionnaire | PTSD symptoms, dissociative experiences, psychobiological symptoms, general psychiatric distress/Brief Symptom Inventory, Dissociative Experiences Scale, PTSD Checklist, Trauma History Questionnaire, Psychotherapy Process Q set, respiratory sinus arrhythmia, Skin conductance level |

| Decker (2017)[40]/United States | Describe the impact of a brief, trauma-informed, universal IPV and reproductive coercion assessment and education | Quasi-experimental single group/Baseline, 3 months post-intervention | Females aged 18-36 who had suffered from partner violence (N = 132) | Not directly measured | Interpersonal violence and reproductive coercion/Questions from previous family planning clinic-based studies (Revised Conflict Tactics Scale 2, Perception of Abuse), reproductive coercion measured by 10 questions |

| Decker (2017)[39]/United States | Develop and test a trauma-informed intervention to improve safety and reduce HIV among female sex workers | Quasi-experimental, single group/Baseline, and 10-12 week follow up | Female sex workers (traded sex for drugs, money, or other resources in the past 3 months; N = 60) | Revised Conflict Tactics Scale adapted for sex work | Depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, harm reduction/Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, Sex Work-specific Rape Myths Scale, Sex Work Safety Behavior Scale, Condom Confidence scale, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, PTSD CheckList |

| de Roos (2010)[38]/Netherlands | Test the effectiveness of a trauma focused psychological approach in the treatment of chronic phantom limb pain using a standardized EMDR protocol | Quasi-experimental/2 weeks before and after intervention, 3 mo after intervention and long-term (mean time: 2.8 years) | Individuals with limb amputation from accidents, cancer, medical failures or complex regional pain syndrome (N = 10; 60% female) | EMDR assessment to identify target traumatic memory | Pain intensity, psychological distress, fatigue, PTSD symptoms, health related quality of life/Pain intensity diary, Symptom Checklist 90, Checklist Individual Strength-Revised, Impact of Events Scale and Self-Inventory List, Short Form-36 Health Survey |

| Doering (2013)[28]/Germany | Investigate the effectiveness of EMDR treatment on reducing dental phobia | RCT/Baseline, 4 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year | Individuals diagnosed with dental phobia (N = 31) | Not directly measured | Dental stress and anxiety/Dental Anxiety Scale, Dental Fear Survey |

| Dutton (2016)[41]/United States | Examine differential response trajectories to trauma-elated imaginal exposure as a function of affective lability | Quasi-experimental/During sessions | Females with sexual victimization (N = 72) | Sexual victimization that satisfied the definition of a traumatic event as specified in DSM–IV–TR | PTSD symptoms/Clinician-administered PTSD scale, Responses to script-driven imagery scale, Affect Lability Scale-18 |

| Ford (2018)[27]/United States | Test an emotion enhancement to cognitive therapy TARGET (Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy) | RCT/Baseline, immediately post-intervention and 1 month follow up | College student problem drinkers and had a history of traumatic childhood stressor or trauma (N = 29) | Traumatic Events Screening Instrument for Adults | Alcohol use and abuse, PTSD, therapy expectancy and working alliance/Global Assessment of Individual Needs-Short Screen alcohol use subscales, Negative Mood Regulation Scale, Stress Reactions Checklist for disorders of extreme stress, PTSD checklist, Expectancy of therapeutic outcome, Brief Working Alliance Inventory |

| Gawande (2019)[29]/United States | Determine if Mindfulness Training for Primary Care impact health behavior change for primary care patients randomized versus a low-dose comparator | RCT/Baseline, 8-week and 24-week follow up | Individuals with a DSM-V diagnosis (N = 136) | Not directly measured | Behavior change related to self-management of health, anxiety and depressive symptoms, stress, self-emotional regulation, interoceptive awareness, mindfulness, self-compassion/Self-reported level of action plan initiation, Patient-Reported Outcomes Information System (PROMIS) Anxiety and Depression short forms, Perceived Stress Scale, Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale, Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness, Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Self-Compassion Scale short form, Self-Efficacy for Chronic Disease, Perceived Control Questionnaire |

| Ginzburg (2009)[22]/United States | Evaluate the effectiveness of group psychotherapy in reducing levels of shame and guilt in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse at risk for HIV | RCT/Baseline, immediately post-intervention, 6 mo post intervention | Females that experienced childhood sexual abuse between (N = 166; 100% female) | Self-report of ≥ 2 explicit memories of sexual abuse involving genital contact between age 4 -15 | Guilt, shame, PTSD/Guilt Subscale of the Abuse-Related Beliefs Questionnaire, Shame Subscale of the Abuse-Related Beliefs Questionnaire, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist |

| James (2013)[37]/Haiti | Evaluate an evidence-based culturally appropriate lay-person intervention for PTSD experienced by post-Haiti earthquake victims | Quasi-experimental/Pre and post-test | Individuals with PTSD from the 2010 Haitian earthquake (N = 60; 73% female) | Not directly measured | PTSD symptoms, compassion fatigue, posttraumatic growth/Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, Professional Quality of Life Scale, Posttraumatic Growth Inventory |

| Kelly (2015)[16]; (2016)[17]/United States | Evaluate a trauma-informed model of mindfulness-based stress reduction as a phase I trauma intervention for female survivors of IPV | RCT/Baseline and post-intervention | Female IPV survivors (N = 45) | Self-reported history of IPV (physical or sexual abuse) | PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, attachment patterns/Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder CheckList-Civilian Version, Beck Depression Inventory, Relationship Structures Questionnaire. |

| Lundqvist (2006)[42]/Sweden | Compare psychological symptoms, symptoms for PTSD, and the sense of coherence across three groups | Quasi-experimental with 3 arms (long-term group therapy, wait list, and short-term group)/Baseline, 12 months (for psychological symptoms and sense of coherence), 2 years after treatment (for inpatient days and sick listing days) | 100% Swedish female who were sexually abused in childhood (N = 77; n = 45 for long-term therapy group, n = 10 for wait list group, and n = 22 for short-term therapy group) | Not directly measured | Symptoms of PTSD, psychological symptoms, current psychological health, life attitudes in response to stress, sense of coherence and life events./DSM-IV, Symptom Checklist-90 and Global Severity Index, Sense of Coherence Scale, Life Events |

| Lundqvist, (2009)[43]/Sweden | Evaluate changes after a two-year-long trauma-focused group therapy program for adult females who had been sexually abused in childhood | Quasi-experimental/Pre and post-test | Female outpatients sexually abused in childhood (N = 45) | Not directly measured | Social interaction, social adjustment, perceived family climate/Interview Schedule of Social Interaction, Social Adjustment scale, Family Climate Test |

| MacIntosh (2018)[46]/Canada | Describe the implementation of the Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation | Quasi-experimental/Pre and post intervention | Individuals that experience childhood sexual abuse (N = 85) | Life Events Checklist for trauma history | Emotion regulation, interpersonal problems, PTSD symptoms/Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, ICD-11 Trauma Questionnaire, Life Events Checklist |

| Masin-Moyer (2019)[47]/United States | Compare clinical outcomes of a 16-week version of the Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) for women and an attachment-informed adaptation (ATREM) | Quasi-experimental/Pre and post-test | Patients diagnosed with a mental health and/or substance use condition (N = 69; n = 37 in ATREM group, n = 32 in TREM group) | Self-reported history of interpersonal trauma | Group attachment style, perceived social support, difficulty regulating emotions during times of distress, psychological distress related to depression, anxiety, and somatization, PTSD symptoms/Relationship Scale Questionnaire, Social Group Attachment Scale, Social Provisions Scale, Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale, Brief Symptom Inventory-18, PTSD Symptom Scale, Addiction Severity Index, Life Stressor Checklist–Revised |

| Matthijssen (2019)[30]/Netherlands | Test if Visual Schema Displacement Therapy is capable of reducing the emotionality and vividness of negative memories | RCT/pre and post intervention | Healthy participants (N = 105; n = 30 in study 1, n = 75 in study 2) | Not directly measured | Emotional disturbances and vividness of traumatic memories/Self-report Subjective Units of Disturbance and vividness of the most disturbing part of the memory |

| Nijdam (2012)[33]/Netherlands | Compare efficacy and response pattern of TF-CBT, brief eclectic psychotherapy for PTSD, with EMDR | RCT/Baseline, weekly at treatment sessions, post-intervention | Individuals 18-65 years with PTSD diagnosis by DSM-IV (N = 70) | Not directly measured | PTSD symptoms, verbal memory, information processing speed, executive functioning/Impact of Event Scale–Revised, Structured Interview for PTSD, California Verbal Learning Test, Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test, Trail Making Test, Stroop Color Word Test |

| Nijdam (2018)[31]/Netherlands | Examine longitudinal changes in neurocognitive functioning before and after trauma-focused psychotherapy | RCT/Assessment before and 17 weeks after start of treatment | Individuals suffering from PTSD (N = 88) | Not directly measured | PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, neuropsychological scores/Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Impact of Event Scale–Revised, California Verbal Learning Test, Paragraph Recall Subtest of the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test, Trail Making Test, Stroop Color Word Test |

| Nixon (2016)[24]/Australia | Examine the effectiveness of cognitive processing therapy compared with active treatment as usual | RCT/Immediately post-intervention, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months | Individuals with acute stress disorder that had experienced sexual assault or rape in the past month (N = 47) | Not directly measured | Acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms/Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, PTSD CheckList, Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory, MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire |

| Noroozi (2018)[32]/Iran | Determine the effectiveness of trauma-based cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressed divorced women | Pre/post-test control group/3-month follow up | Females with a history of traumatic event regarding social justice (N = 133) |

Not directly measured | Depression symptoms/Beck Depression Inventory |

| Paivio (2010)[25]/Canada | Evaluate and compare emotion-focused therapy for trauma with imaginal confrontation and emotion-focused therapy for trauma with empathic exploration | RCT/Pre-intervention, mid-intervention, post-intervention and follow up | Individuals that experienced emotional, physical, or sexual childhood abuse (N = 45; 53% female) | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire | PTSD symptoms, interpersonal difficulties, anxiety, depression, self-esteem, resolution and discomfort/Impact of Event Scale, State Trait Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Target Complaints (Discomfort) Scale, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, Resolution Scale |

| Sacks (2008)[19]/United States | Evaluate the effectiveness of the three componentsof the Dual Assessment and Recovery Track program as compared with that of the basic outpatient treatment program | RCT/Baseline, 12 months | Individuals with substance abuse and co-occurring disorders (N = 240) | Trauma History Questionnaire | Substance use, crime, employment, psychological health, trauma, housing, depression, psychological symptoms, community and interpersonal violence, and exposure to trauma/Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN-Q and GAIN-I), Beck Depression Inventory-II, Brief Symptom Inventory, Trauma History Questionnaire |

| Sikkema (2017)[34] /South Africa |

Evaluate feasibility and potential efficacy of the intervention "Improving AIDS Care after Trauma," a coping intervention for HIV-infected women | RCT/Baseline, 3 months, and 6 months | Females with a diagnosis of HIV, met antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation criteria and had a history of sexual abuse (N = 64) | Self-reported history of sexual abuse | PTSD symptoms, coping (avoidant, spiritual), adherence motivation, HIV care management/PTSD CheckList, Life Windows Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills ART Adherence Questionnaire, HIV Care Engagement survey |

| Vitriol (2009)[20]/Chile | Examine the effectiveness of a three-month structured outpatient intervention for women with severe depression and childhood trauma | RCT/Baseline, 3 months, 6 months | Females that experience traumatic childhood trauma and have severe depression (N = 87) | Self-reported traumatic experience before age 15; separation from a parent or caregiver, alcohol or drug abuse by family member, physical injury related to punishment, and forced sexual contact | Depressive symptoms, symptoms of PTSD/Hamilton Depression Scale, Composite International Diagnostic Interview-10, Lambert’s Outcome Questionnaire-45.2, Post-traumatic Stress Treatment Outcome scale |

| Nixon (2016)[24]/Australia | Examine the effectiveness of cognitive processing therapy compared with active treatment as usual | RCT/Immediately post-intervention, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months | Individuals with acute stress disorder that had experienced sexual assault or rape in the past month (N = 47) | Not directly measured | Acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms/Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, PTSD CheckList, Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory, MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire |

| Noroozi (2018)[32]/Iran | Determine the effectiveness of trauma-based cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressed divorced women | Pre/post-test control group/3-month follow up | Females with a history of traumatic event regarding social justice (N = 133) | Not directly measured | Depression symptoms/Beck Depression Inventory |

| Paivio (2010)[25]/Canada | Evaluate and compare emotion-focused therapy for trauma with imaginal confrontation and emotion-focused therapy for trauma with empathic exploration | RCT/Pre-intervention, mid-intervention, post-intervention and follow up | Individuals that experienced emotional, physical, or sexual childhood abuse (N = 45; 53% female) | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire | PTSD symptoms, interpersonal difficulties, anxiety, depression, self-esteem, resolution and discomfort/Impact of Event Scale, State Trait Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Target Complaints (Discomfort) Scale, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, Resolution Scale |

| Sacks (2008)[19]/United States | Evaluate the effectiveness of the three components of the Dual Assessment and Recovery Track program as compared with that of the basic outpatient treatment program | RCT/Baseline, 12 months | Individuals with substance abuse and co-occurring disorders (N = 240) | Trauma History Questionnaire | Substance use, crime, employment, psychological health, trauma, housing, depression, psychological symptoms, community and interpersonal violence, and exposure to trauma/Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN-Q and GAIN-I), Beck Depression Inventory-II, Brief Symptom Inventory, Trauma History Questionnaire |

| Sikkema (2017)[34]/South Africa | Evaluate feasibility and potential efficacy of the intervention "Improving AIDS Care after Trauma," a coping intervention for HIV-infected women | RCT/Baseline, 3 months, and 6 months | Females with a diagnosis of HIV, met antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation criteria and had a history of sexual abuse (N = 64) | Self-reported history of sexual abuse | PTSD symptoms, coping (avoidant, spiritual), adherence motivation, HIV care management/PTSD CheckList, Life Windows Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills ART Adherence Questionnaire, HIV Care Engagement survey |

| Vitriol (2009)[20]/Chile | Examine the effectiveness of a three-month structured outpatient intervention for women with severe depression and childhood trauma | RCT/Baseline, 3 months, 6 months | Females that experience traumatic childhood trauma and have severe depression (N = 87) | Self-reported traumatic experience before age 15; separation from a parent or caregiver, alcohol or drug abuse by family member, physical injury related to punishment, and forced sexual contact | Depressive symptoms, symptoms of PTSD/Hamilton Depression Scale, Composite International Diagnostic Interview-10, Lambert’s Outcome Questionnaire-45.2, Post-traumatic Stress Treatment Outcome scale |

| Wieferink (2017)[48]/Netherlands | Analyze whether there is a difference in decrease of days of substance use, craving and psychiatric symptoms during subjective units of disturbance treatment between patients with higher or lower levels of PTSD symptoms | Retrospective study/Baseline, 3 months, 6 months | All participants followed regular substance use disorder treatment (N = 297, 72% male) | Not measured | PTSD symptoms, cravings, depression, anxiety and stress/Self- Report Inventory for PTSD, Substance Use Inventory, Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales-21 |

ART: Antiretroviral Therapy.

ATREM: Attachment-informed adaptation Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model.

DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition.

EMDR: Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing.

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Viruses.

ICD: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.

IPV: Intimate Partner Violence.

PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial.

TANF: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

TF-CBT: Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral therapy.

TREM: Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model.

The studies included in this review recruited their study populations largely based on the type of trauma they were aiming to address, such as individuals that experienced interpersonal traumatic event such as child abuse, sexual assault, or domestic violence [16–18,20–22,24–26,35,40–43,45,46], individuals with substance abuse disorders [19,47,48], couples experiencing clinically significant marital issues [23], individuals with limb amputations [38], dental phobia [28], or fire service personnel suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder [44]. Trauma was self-reported in eight articles [16,17,20,22,26,34,35,47]. In contrast, nine studies clearly identified a measurement of trauma; the Trauma History Questionnaire [19,45], the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [23,25], the Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule [23], the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale adapted for sex work [39], the Traumatic Events Screening Instrument for Adults [27], the Life Events Checklist [46], and the Adverse Childhood Experiences [18]. Two studies used a clinical tool (e.g. eye movement desensitization and reprocessing [38] and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition [41] to identify or diagnose trauma. Fifteen studies did not include direct measurements for trauma [21,24,28–33,36,37,40,42–44,48].

Quality ratings

Tables 2–4 shows final scores of quality assessment. Quality of the 32 unique studies included in this review varied across individual studies. Twelve of 19 RCTs included in the review were of high quality (i.e., 9 to 11) [17,18,20,21,24,26,28,29,31,33–35] and six were of medium quality (i.e., 5 to 8) [19,22,23,25,27,30]. One study scored 4 of 12 [32]. The low rating study [32] lacked relevant information to adequately score its methodological rigor. Most RCTs clearly described randomization, group equivalence at baseline, rates and reasons for attrition, study outcomes, and analysis. Blinding of outcomes assessors to treatment assignment was used and described in several RCTs [17,20,21,24,27,35], whereas blinding of those delivering treatment was discussed clearly in only one study [25]. The majority of the quasi-experimental studies were of high quality (i.e., 7 or higher), except two, which scored 2 of 9 [37] and 6 of 9 [39], respectively. Six of twelve quasi-experimental studies [36,41–44,47] had a comparison group to strengthen internal validity of causal inferences by comparing intervention and control groups. Some of these studies, however, noted differences in baseline assessments between groups [36,43,44]. Finally, one retrospective study [48] scored 11 of 11 and hence was rated as high quality.

Table 2. Study quality ratings for randomized control trials.

| Randomized controlled trial | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Items |

Boosh-ehri [18] | Bowland [35] | Bryant [21] | Classen [26] | Dalton [23] | Doering [28] | Ford [27] |

Gawande [29] | Ginzburg [22] | Kelly [17] |

Matth-ijssen [30] | Nijdam [33] | Nijdam [31] | Nixon [24] | Nor-oozi [32] | Paivio [25] | Sacks [19] | Sikk-ema [34] | Vitriol [20] |

| 1. Was true randomization used? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | 1 | ? |

| 3. Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | ? | 0 | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ? | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? | ? | 1 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 1 | 0 | ? | 1 | ? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | 1 |

| 6. Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analyzed? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Were participants analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| 11. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12. Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total Score | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 9 |

Table 4. Study quality ratings for cohort study.

| Cohort study | |

|---|---|

| Items | Wieferink [48] |

| 1. Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? | 1 |

| 2. Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups? | 1 |

| 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | 1 |

| 4. Were confounding factors identified? | 1 |

| 5. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | 1 |

| 6. Were the participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)? | 1 |

| 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | 1 |

| 8. Was the follow up time reported and sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur? | 1 |

| 9. Was follow up complete, and if not, were the reasons to loss to follow up described and explored? | 1 |

| 10. Were strategies to address incomplete follow up utilized? | 1 |

| 11. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 1 |

| Total Score | 11 |

+1 = yes; 0 = no; ? = unclear.

Table 3. Study quality ratings for quasi-experimental studies.

| Quasi-experimental study | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Beaumont[44] | D’Andrea [45] | Decker [40] | Decker [39] | de Jongh [36] | de Roos [38] | Duton [41] | James [37] | Lundqvist [42] | Lundqvist[43] | Mac-Intosh [46] | Masin-Moyer [47] |

| 1. Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4. Was there a control group? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 5. Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analyzed? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | 1 | 1 | ? | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total Score | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

Characteristics of trauma-informed interventions

Type of intervention

Table 5 details the trauma informed intervention characteristics included in this review. The two most frequently used interventions were eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) [28,30,31,33,36,38]—a multi-phase intervention using bilateral stimulation, such as left-to-right eyes movements or hand tapping, to desensitize individuals to a traumatic memory or image—and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [26,27,32,46,48]—a psychological approach to introduce emotional regulation and coping strategies (e.g., deep muscle relaxation, yoga, thought discovery and breathing techniques) to deal with negative feelings and behaviors surrounding a trauma of interest [32,48]. The implementation of CBT varied on the trauma of interest. Other studies implemented interventions using general trauma focused therapy [22,43], emotion focused therapy [23,25], stress reduction programs [17], cognitive processing therapy [24], brief electric psychotherapy [31], present focused group therapy [26], compassion focused therapy [44], prolonged exposure [45], stress inoculation training [45], psychodynamic therapy [45], and visual schema displacement therapy [30]. A number of studies included more than one of these therapies [13,26,30,31,33,36,45].

Table 5. Trauma-informed intervention characteristics.

| 1st author (yr)[ref]/Intervention | Intervention Description | Setting | Interventionists | Fidelity | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beaumont (2016)[44]/Compassion focused therapy (CFT) and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) | 12 weekly sessions of either TF-CBT or TF-CBT with CFT. First and last sessions were 1.5 hours, all others were 1 hour. Both groups received TF-CBT from a psychotherapist and psychoeducation. Those in the TF-CBT group with CFT also received education on the CFT and practiced compassionate letter writing to themselves | Location not specified | Cognitive behavioral therapist | Not addressed | TF-CBT combined with CFT was more effective than TF-CBT alone at increasing self-compassion (p = .05). TF-CBT and CFT not statistically significant for depression and avoidance, however revealed a downward trend in the combined TF-CBT + CFT groups. |

| Booshehri (2018)[18]/The Building Wealth and Health Network | 28-week financial empowerment education with assistance in opening a credit union savings. Matched savings 4-hour weekly peer support group guided by The Sanctuary Model, a trauma-informed approach to social services | Financial empowerment group classes | 2 trained financial services organization facilitators | Not addressed | Compared to the other groups, caregivers in the full intervention had better self-efficacy (p = 0.039) and depressive symptoms (p = 0.015) and reduced economic hardship (p = 0.064). Unlike the intervention groups, the control group reported increased developmental risk among their children. Although the control group showed higher levels of employment, the full intervention group reported greater earnings. |

| Bowland (2012)[35]/Spiritually focused intervention | 11 weekly group sessions that manualized psychoeducational cognitive restructuring and skill building approaches to address spiritual struggles in trauma recovery. Sessions were 1.5 hours | Not reported | Not specified | Independent evaluator randomly rated selected videotapes of group sessions | Women in treatment group had lower scores on traumatic, depressive, anxiety and somatic symptoms. Trauma scores fell from mean 19.43 to 11.86. Depressive symptoms decreased by 8.81 compared to .73 increase in control. Anxiety decrease was 6.28 compared to 1.60 increase in control. Somatic symptoms decreased by 2 points compared to increase of 0.55 in control. |

| Bryant (2008)[21]/Prolonged exposure and cognitive restructuring | 5 weekly sessions. Prolonged Exposure consisted of participant engagement in exposure to trauma, homework and strategies to manage stress. Cognitive restructuring consisted of Psychoeducation and homework to restructure thoughts surrounding trauma. | Traumatic Stress Clinic | Master level clinical psychologists | Training manual; weekly supervision of sessions; and audios of 45 random sessions rated by psychologists not involved in intervention | At follow up, patients on prolonged exposure treatment were less likely to meet PTSD criteria than those who underwent cognitive restructuring (37% vs. 63%; odds ratio [OR] = 2.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.12-3.94) and to achieve full remission (47% vs. 13%; OR = 2.78, 95% CI = 1.14-6.83). |

| Classen (2011)[26]/Trauma focused group therapy (TFGT) and present focused group therapy (PFGT) | 24 weekly sessions (each session lasting 1.5 hours). TFGT involved activation and exploration of trauma memories to restructure cognitive and emotional understanding of traumatic events to minimize the trauma’s impairment on current experience/functioning. PFGT focused on examining current functioning, illuminating in the here-and-now maladaptive expectations and behaviors to help restructure views of self and others. | Research lab | Psychologists, psychiatrists and master level clinicians with prior experience in working with trauma survivors and group therapy | Brief post-session survey completed at end of every session; One randomly selected session for each group rated on the post-session questionnaire by 2 raters who were kept blind to condition | PFGT had greater advantage than TFGT in total HIV risk reduction (p = .05); but all three groups had significant reduction in total HIV risk scores overtime. Both TFGT and PFGT had an advantage on PTSD severity compared to waitlist condition (p<.05); but all three groups showed significant reduction in PTSD severity over time. TFGT had a significantly greater reduction in anger/irritability compared with PFGT (p<.01). |

| Dalton (2013)[23]/Emotion focused therapy (EFT) | EFT sessions (22 couple and 2 individual sessions) helped clients symbolize and work through their emotional responses to traumatic events through a focus on creating safe interpersonal connections. Sessions lasted 1.25 hours | Research office | Five therapists, four of which were masters level mental health therapists and one of which was the primary investigator. Therapists had at least 4 years of experience in treating childhood abuse and received five months of weekly training in EFT | All sessions audio-taped. Weekly group supervision done by primary investigator (experienced EFT therapist). A random selection of 25-30% of all taped sessions sent to a senior EFT trainer with 3 therapy implementation check | The couples in EFT group demonstrated significant reduction in relationship distress (p<.04). A statistically significant proportion of participants who participated in EFT displayed clinically relevant improvement on the DAS from pretest to post-test (p<.001). However, no participants in the control group exhibited clinically significant changes on the DAS. |

| D’Andrea (2012)[45]/Trauma focused therapy | Trauma focused therapy included prolonged exposure (PE), stress inoculation training (SIT) and psychodynamic therapy (PDT) over 12 weekly sessions. Therapy focused on reconstructing the patient’s memories of the traumatic events by discussing feelings, perceptions, coping, relationships, etc. surrounding the event |

Lab setting | 22 trauma-oriented therapists who were recruited through printed advertisements or by the clients | Therapists rated their overall treatments using 9 points scales from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic) to 9 (extremely characteristic) via the Psychotherapy Process Q Set | Reduced subjective PTSD symptoms but showed no change in subjective dissociation, depression, anxiety, or interpersonal sensitivity symptoms after 12 weeks. Greater presence of PDT process was significantly associated with greater reductions in PTSD and depression symptoms (p<.05 for both). Greater presence of SIT process was related to greater reduction in PTSD symptoms (p<.05). Clients showed significant improvement in trauma-related attention bias (p<.01) and anxiety-related attention bias (p<.05) but not in attention bias for neutral words. Greater PDT and greater SIT process were both marginally related to reduced implicit memory for anxiety cues (p<.1 for both). PE process levels were unrelated to any significant change after 12 weeks of treatment. |

| Decker (2017)[40]/Trauma informed partner violence assessment with Addressing Reproduction Coercion in Health Settings (ARCHES) | ARCHES assessment included a universal assessment of the recognition of abuse. Intervention included harm reduction counseling and referrals to violence support provider. A provider facilitated discussion of intimate partner violence. Reproductive coercion was addressed with a safety card including suggestions for harm reduction and national resources for violence related help-seeking | Family planning health centers | Physician/Providers who received a day-long training from national experts | Not addressed | Those who received violence related discussion and/or safety resources felt more confident in their providers concern for their safety and ability to respond appropriately to violence. Treatment increased knowledge of violence-related resources. Close to two thirds (65%) of women reported receiving at last one element of the intervention on their exit survey and reported that clinic base Interpersonal violence assessment was helpful irrespective of past violence history. |

| Decker (2017)[39]/Integrating safety promotion with HIV risk reduction | Brief, semi-structured dialogue that was reinforced with a safety card. Dialogue blended trauma-informed sup- port, validation, safety promotion. Semi-structured dialogue took on average 5–8 minutes and up to 15 minutes depending on participant response and needs. Also linked participants to services. | Mobile vans or adjacent vehicles in community setting | Field research team selected based on experience working with the target population. They underwent training specific to sex workers, violence-related research and practice, and ethics in research | Not addressed | At follow-up, improvements were seen in avoidance of client condom negotiation (p = 0.04) and frequency of sex trade under the influence of drugs or alcohol (p = 0.04). Women’s safety behavior increased (p<0.001). Participants improved knowledge and use of sexual violence support (p<0.01) and use of intimate partner violence support (p<0.01). Change in rape myths, depression and PTSD did not reach statistical significance. |

| de Jongh (2011)[36]/TF-CBT and Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR) | TF-CBT: Patient guided through remembrance of trauma via a cohesive narrative of the event(s) until extinction occurs. EMDR: Patients focus on trauma of the event, while tracking a movement with their eyes. in vivo exposure involved patient self-managed homework. | Therapist’s office | 125 therapists accredited in CBT or EMDR. Patients were assigned to therapist based on geographic proximity | Not addressed | Therapist Rated Outcome revealed that both treatments were highly effective but without significant difference between the treatment groups. Those with travel phobia experienced a greater reduction in symptoms as measured by the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) than those with travel anxiety (p<0.04). HADS revealed a significant effect of time but no significance between groups for main effect of treatment or diagnosis. |

| de Roos (2010)[38]/EMDR | EMDR targeted trauma, pain-related disturbing memories, and phantom-limb pain. Standard EMDR protocol utilized to target trauma and pain-related disturbing memories. Number of sessions individualized to the patient (mean number of sessions 5.9). Sessions lasted 1.5 hours. Sessions occurred weekly. | Individual therapy; location not stated | 2 senior psychotherapists trained in EMDR | Not addressed | Significant decrease in pain score (p<0.001) at 2 weeks and 3 months after with an overall time effect for reduction in pain intensity (p<0.02). |

| Doering (2013)[28]/EMDR | 3 weekly sessions. Sessions lasted 1.5 hours. EMDR treatment consisted of reprocessing of memories using the application of eye movements to tax working memory. A series of 25-30 horizontal movements were repeated until the subjective distress reached zero | Psychotherapist’s office at the dental clinical | Therapist trained in both CBT and EMDR. Therapist received specialized EMDR supervision for the treatment of dental phobia | All sessions videotaped. One randomly selected session rated by five different raters | The intervention group improved on all outcome variables except for depression. Dental anxiety total score pretreatment to 12 months (d = 3.28) was significant (p<.001). There was continuing decrease of dental anxiety up to 3 months after treatment and plateaued. Significant reduction of PTSD symptoms between baseline and 3 months follow up (at 12 months, difference was no longer significant). |

| Dutton (2016)[41]/Imagery exposure | 8 trauma focused sessions and 2 neutral session. Sessions were 30 min each and included 5-min baseline exposure and five 5-minute exposure trials. The imagery exposure was conducted with standardized imagery scenes and cued the participants to focus on their active responses (e.g., did your breathing or heart rate change?) | Laboratory | Clinicians (training unspecified) | Not addressed | Mean responses to script-driven imagery scale scores following the first exposure trial were > zero (p<0.001), and symptom ratings decreased significantly across exposure trials (p = 0.001). Past month CAPS score significantly predicted responses to the first trauma script presentation (p<0.001). |

| Ford (2018)[27]/CBT and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy (TARGET) | 8 sessions of manualized internet-supported CBT for problem drinking with or without trauma-focused emotional regulation skills | University of Connecticut counseling center | PhD clinical psychology students received training (10 hours) to conduct both therapies and were randomly assigned to participants. Each therapist conducted at least 5 cases of each therapy modality | First author reviewed therapist’s first two cases and 33% of the sessions following (randomly chosen). Fidelity was achieved on 100% of all items in all sessions in both therapies | Both treatments showed significant reduction in days of alcohol use in the past month (p = .006); days of impairment due to alcohol use were reduced at post-treatment and follow-up only for the CBT+TARGET group but the base rate was very low (approximately 1.25 days in the past month) and the change for both groups was not statistically significant. |

| Gawande (2019)[29]/Mindfulness Training for Primary Care (MTPC) | MTPC incorporates elements from mindfulness- based stress reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy with evidence-based elements from other mindfulness-oriented behavior change approaches. 8 weekly sessions lasting 2 hours and 1 session lasting 7 hours were offered. Participants were recommended to complete 30–45 minutes of daily home practice with guided recordings. | Office for group and home-based practice | 13 trained providers including 12 licensed mental health clinicians (e.g., psychology, social-work, psychiatry) and one primary care provider. Providers completed 35 hours of MBSR and 40 hours of MTPC training | Weekly supervision and session-specific fidelity checklists were used. Sessions were audio-recorded and 10% were reviewed by trained observers for adherence and competency, preventing drift | MTPC participants reported a higher rate of action plan initiation (API) compared with low-dose comparator (LDC) of participants who responded to the API survey. MTPC remained associated with higher API. Participants randomized to MTPC, relative to LDC, had significantly higher adjusted odds of self-management action plan initiation in an intention-to-treat analysis (OR = 2.28; 95% CI = 1.02 to 5.06). |

| Ginzburg (2009)[22]/TFGT | Present focused group therapy (PFGT) focused on the link between symptomatology and the immediate distress. Trauma focused group therapy (TFGT) emphasized the link between symptomology and the past environment. Patients were guided through retrieval and reinterpretation of traumatic memories to work-through and reconstruct painful memories in TFGT and in PFGT, to identify and modify current maladaptive behaviors and coping strategies. Both groups were conducted over 24 weekly sessions (sessions lasted 1.5 hours). | Three universities in California | Licensed clinical psychologists | Not addressed | Both shame and guilt, significant treatment effects were found for TFGT and PFGT compared with waitlist at 12-months (p = 0.01 and p = 0.03, respectively). Shame and guilt were not significantly related to treatment when TFGT compared with PFGT. |

| James (2013)[37]/Soulaje Lespri Moun (SLM; "Relief for the Spirit" in Haitian Creole) | Drop in program within the internally displaced people camps. 12 group seminars (2 hour-drop in seminars, 3 times a week). Seminars covered earthquake safety, common somatic and emotional responses to stress and trauma, basic relaxation and self-soothing techniques, coping skills, spirituality. | Internally displaced people camps in Port-au-Prince metropolitan area | Earthquake survivors delivered intervention. US and Haitian mental health and psychosocial professionals trained survivors | Not addressed | In the 1st study, lower trauma scores achieved after SLM (p<.01). In the 2nd study, where seminars were offered more frequently and in a more private space, there was a reduction in PTSD symptoms post seminar attendance (p<.001). In 3rd study, there was a reduction of PTSD symptoms post treatment (p<.001). |

| Kelly (2015)[16]; (2016)[17]/Trauma informed mindfulness-based stress reduction (TI-MBSR) | The 8-week mindfulness course consisted of movement exercises, didactic lecture, and group discussion. Sessions lasted 2 to 2.5 hours. Participants were also asked to practice mindfulness 30-45 minutes a day with provided CD. | Group sessions were in-person, unspecified location. Guided mindfulness was completed at participants location of choice | Licensed clinical social workers | Ensured fidelity using a checklist to document each intervention component as it was delivered during the session (100% adherence) | TI-MBSR group reported significantly greater reductions in posttraumatic stress than the waitlist control group (p = .004, d = .94). TI-MBSR group reported significantly greater decreases in depression than the waitlist control group (p = .006, d = .86). TI-MBSR group reported significantly greater decreases in anxious attachment than the waitlist control group (p = .033, d = .85). |

| Lundqvist (2006)[42]/Trauma-focused therapy | 46 group therapy sessions with a phase-divided structure. Phase 1 was 22 sessions during 5 months, twice a week to help women discuss their childhood sexual abuse narratives and discuss relationships in family of origin. Phase 2 had 15 weekly sessions during 4 months to work through present life. Phase 3 had 9 monthly sessions during 1 year, to work with separation and get used to autonomy. The group therapy model for the short-term group was limited to 20 weekly sessions and including six topics. | Outpatient treatment unit | 2 female group leaders did all group sessions in all 10 groups together | Not addressed | No group differences in psychological and PTSD symptoms and sense of coherence. Significant reductions for the study group in the total symptom score and in 8 of 9 scales of Global Severity Index (p<.05); reductions for the short-term group in 4 of 9 subscales (p<.05); and no differences for the wait-list group. A PTSD reduction for the study group, from 87% to 40% (p<.01) but not for the waiting-list group. An increase in sense of coherence for both groups (10-point and 7-point, respectively; p<.05). |

| Ginzburg (2009)[22]/TFGT | Present focused group therapy (PFGT) focused on the link between symptomatology and the immediate distress. Trauma focused group therapy (TFGT) emphasized the link between symptomology and the past environment. Patients were guided through retrieval and reinterpretation of traumatic memories to work-through and reconstruct painful memories in TFGT and in PFGT, to identify and modify current maladaptive behaviors and coping strategies. Both groups were conducted over 24 weekly sessions (sessions lasted 1.5 hours). | Three universities in California | Licensed clinical psychologists | Not addressed | Both shame and guilt, significant treatment effects were found for TFGT and PFGT compared with waitlist at 12-months (p = 0.01 and p = 0.03, respectively). Shame and guilt were not significantly related to treatment when TFGT compared with PFGT. |

| James (2013)[37]/Soulaje Lespri Moun (SLM; "Relief for the Spirit" in Haitian Creole) | Drop in program within the internally displaced people camps. 12 group seminars (2 hour-drop in seminars, 3 times a week). Seminars covered earthquake safety, common somatic and emotional responses to stress and trauma, basic relaxation and self-soothing techniques, coping skills, spirituality. | Internally displaced people camps in Port-au-Prince metropolitan area | Earthquake survivors delivered intervention. US and Haitian mental health and psychosocial professionals trained survivors | Not addressed | In the 1st study, lower trauma scores achieved after SLM (p<.01). In the 2nd study, where seminars were offered more frequently and in a more private space, there was a reduction in PTSD symptoms post seminar attendance (p<.001). In 3rd study, there was a reduction of PTSD symptoms post treatment (p<.001). |

| Kelly (2015)[16]; (2016)[17]/Trauma informed mindfulness-based stress reduction (TI-MBSR) | The 8-week mindfulness course consisted of movement exercises, didactic lecture, and group discussion. Sessions lasted 2 to 2.5 hours. Participants were also asked to practice mindfulness 30-45 minutes a day with provided CD. | Group sessions were in-person, unspecified location. Guided mindfulness was completed at participants location of choice | Licensed clinical social workers | Ensured fidelity using a checklist to document each intervention component as it was delivered during the session (100% adherence) | TI-MBSR group reported significantly greater reductions in posttraumatic stress than the waitlist control group (p = .004, d = .94). TI-MBSR group reported significantly greater decreases in depression than the waitlist control group (p = .006, d = .86). TI-MBSR group reported significantly greater decreases in anxious attachment than the waitlist control group (p = .033, d = .85). |

| Lundqvist (2006)[42]/Trauma-focused therapy | 46 group therapy sessions with a phase-divided structure. Phase 1 was 22 sessions during 5 months, twice a week to help women discuss their childhood sexual abuse narratives and discuss relationships in family of origin. Phase 2 had 15 weekly sessions during 4 months to work through present life. Phase 3 had 9 monthly sessions during 1 year, to work with separation and get used to autonomy. The group therapy model for the short-term group was limited to 20 weekly sessions and including six topics. | Outpatient treatment unit | 2 female group leaders did all group sessions in all 10 groups together | Not addressed | No group differences in psychological and PTSD symptoms and sense of coherence. Significant reductions for the study group in the total symptom score and in 8 of 9 scales of Global Severity Index (p<.05); reductions for the short-term group in 4 of 9 subscales (p<.05); and no differences for the wait-list group. A PTSD reduction for the study group, from 87% to 40% (p<.01) but not for the waiting-list group. An increase in sense of coherence for both groups (10-point and 7-point, respectively; p<.05). |

| Lundqvist, (2009)[43]/Trauma focused group therapy | 2-year long trauma focused group therapy. 46 sessions total with phase 1 containing 22 weekly sessions over 5 months, phase 2 containing 15 weekly sessions over 4 months, and phase 3 comprising 9 sessions over 1 year. Sessions were designed to help women tell their childhood sexual-abuse narratives and to discuss relationships within the family. Each participant was the central narrator in 3 sessions during which she could tell the others about sexual details in abuse, feelings of shame, and feelings of guilt. | Outpatient treatment setting | First author was group leader (faculty of Heath and Society at Malmo University) but second group leader was not specified. Both leaders were female | Not addressed | Levels of social interaction significantly improved, with most evident improvements in total score and adequacy of social integration. The effect size values were .55 and .64, respectively. Social adjustment was significantly improved particularly in subscale of work/studies and homework. Effect size values were .53 and .56, respectively. No significant changes in family climate except for the expressed emotion subscale perceived criticism in relation to the partner that showed a reduction. |

| MacIntosh (2018)[46]/Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR) treatment | STAIR consisted of 10 weekly group sessions. First five focused on the impact of trauma on emotions and relationships; labeling and identifying feelings; emotion management; and increased capacity to experience positive emotions. The remaining five sessions included identification of trauma-generated interpersonal ‘‘schemas’’ or expectations that impact current relationships; more positive schemas relevant to effective living in the present; skills training in effective assertiveness; increasing flexibility regarding interpersonal expectations; and enhancing compassion for self and others | Clinic | Center therapist trained by the first author over the course of an intensive day-long training session | Clinical director of the center provided weekly supervision and adherence checks over the course of the groups. Standardized materials were developed by the originator of the STAIR model and given to all therapists. | There was significant reduction in Inventory of Interpersonal Problems scores from pre to post treatment, suggesting lower levels of interpersonal problems (p = .002). There was significant reduction in the mean levels of trauma symptoms reported by participants from pre to post treatment (p = .004). |

| Masin-Moyer (2019)[47]/Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) versus Attachment-informed adaptation TREM (ATREM) | TREM included 16 weekly sessions. Sessions lasted 1.5 hours. ATREM had the same 16 topics as TREM but also had 3 open weeks to add new attachment information involving imagery, arts, fables, group meditation, transitional objects, body tapping and written and verbal feedback. Open weeks were to integrate more processing by pausing content and initiating in-the-moment exploration of relational dynamics and facilitating dyadic and group connections. | Therapy took place at: an outpatient behavioral health facility, a residential substance use treatment, and an outpatient victim services agency | First-author was TREM trained and trained all other clinicians. Each group had at least 1 licensed masters level social worker or counselor. All facilitators participated in training prior to intervention implementation | A facilitator report fidelity checklist was created by 1st author to ensure weekly discussion questions and activities in the TREM manual were addressed | Pre and post intervention results showed statistically significant reductions in individual and group attachment anxiety (p = .03), group attachment avoidance (p<.001), perceived social support (p = .002), emotional regulation capacities (p<.001), psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptom severity (p<.001) for ATREM and TREM. ATREM associated with statistically significant reductions in individual attachment avoidance. |

| Lundqvist, (2009)[43]/Trauma focused group therapy | 2-year long trauma focused group therapy. 46 sessions total with phase 1 containing 22 weekly sessions over 5 months, phase 2 containing 15 weekly sessions over 4 months, and phase 3 comprising 9 sessions over 1 year. Sessions were designed to help women tell their childhood sexual-abuse narratives and to discuss relationships within the family. Each participant was the central narrator in 3 sessions during which she could tell the others about sexual details in abuse, feelings of shame, and feelings of guilt. | Outpatient treatment setting | First author was group leader (faculty of Heath and Society at Malmo University) but second group leader was not specified. Both leaders were female | Not addressed | Levels of social interaction significantly improved, with most evident improvements in total score and adequacy of social integration. The effect size values were .55 and .64, respectively. Social adjustment was significantly improved particularly in subscale of work/studies and homework. Effect size values were .53 and .56, respectively. No significant changes in family climate except for the expressed emotion subscale perceived criticism in relation to the partner that showed a reduction. |

| MacIntosh (2018)[46]/Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR) treatment | STAIR consisted of 10 weekly group sessions. First five focused on the impact of trauma on emotions and relationships; labeling and identifying feelings; emotion management; and increased capacity to experience positive emotions. The remaining five sessions included identification of trauma-generated interpersonal ‘‘schemas’’ or expectations that impact current relationships; more positive schemas relevant to effective living in the present; skills training in effective assertiveness; increasing flexibility regarding interpersonal expectations; and enhancing compassion for self and others | Clinic | Center therapist trained by the first author over the course of an intensive day-long training session | Clinical director of the center provided weekly supervision and adherence checks over the course of the groups. Standardized materials were developed by the originator of the STAIR model and given to all therapists. | There was significant reduction in Inventory of Interpersonal Problems scores from pre to post treatment, suggesting lower levels of interpersonal problems (p = .002). There was significant reduction in the mean levels of trauma symptoms reported by participants from pre to post treatment (p = .004). |

| Masin-Moyer (2019)[47]/Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) versus Attachment-informed adaptation TREM (ATREM) | TREM included 16 weekly sessions. Sessions lasted 1.5 hours. ATREM had the same 16 topics as TREM but also had 3 open weeks to add new attachment information involving imagery, arts, fables, group meditation, transitional objects, body tapping and written and verbal feedback. Open weeks were to integrate more processing by pausing content and initiating in-the-moment exploration of relational dynamics and facilitating dyadic and group connections. | Therapy took place at: an outpatient behavioral health facility, a residential substance use treatment, and an outpatient victim services agency | First-author was TREM trained and trained all other clinicians. Each group had at least 1 licensed masters level social worker or counselor. All facilitators participated in training prior to intervention implementation | A facilitator report fidelity checklist was created by 1st author to ensure weekly discussion questions and activities in the TREM manual were addressed | Pre and post intervention results showed statistically significant reductions in individual and group attachment anxiety (p = .03), group attachment avoidance (p<.001), perceived social support (p = .002), emotional regulation capacities (p<.001), psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptom severity (p<.001) for ATREM and TREM. ATREM associated with statistically significant reductions in individual attachment avoidance. |

| Lundqvist, (2009)[43]/Trauma focused group therapy | 2-year long trauma focused group therapy. 46 sessions total with phase 1 containing 22 weekly sessions over 5 months, phase 2 containing 15 weekly sessions over 4 months, and phase 3 comprising 9 sessions over 1 year. Sessions were designed to help women tell their childhood sexual-abuse narratives and to discuss relationships within the family. Each participant was the central narrator in 3 sessions during which she could tell the others about sexual details in abuse, feelings of shame, and feelings of guilt. | Outpatient treatment setting | First author was group leader (faculty of Heath and Society at Malmo University) but second group leader was not specified. Both leaders were female | Not addressed | Levels of social interaction significantly improved, with most evident improvements in total score and adequacy of social integration. The effect size values were .55 and .64, respectively. Social adjustment was significantly improved particularly in subscale of work/studies and homework. Effect size values were .53 and .56, respectively. No significant changes in family climate except for the expressed emotion subscale perceived criticism in relation to the partner that showed a reduction. |

| MacIntosh (2018)[46]/Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR) treatment | STAIR consisted of 10 weekly group sessions. First five focused on the impact of trauma on emotions and relationships; labeling and identifying feelings; emotion management; and increased capacity to experience positive emotions. The remaining five sessions included identification of trauma-generated interpersonal ‘‘schemas’’ or expectations that impact current relationships; more positive schemas relevant to effective living in the present; skills training in effective assertiveness; increasing flexibility regarding interpersonal expectations; and enhancing compassion for self and others | Clinic | Center therapist trained by the first author over the course of an intensive day-long training session | Clinical director of the center provided weekly supervision and adherence checks over the course of the groups. Standardized materials were developed by the originator of the STAIR model and given to all therapists. | There was significant reduction in Inventory of Interpersonal Problems scores from pre to post treatment, suggesting lower levels of interpersonal problems (p = .002). There was significant reduction in the mean levels of trauma symptoms reported by participants from pre to post treatment (p = .004). |