Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect the health and well-being of individuals and communities worldwide. Patients with cancer are particularly vulnerable to experiencing serious health-related suffering from COVID-19. This requires oncology nurses in inpatient and clinic settings to ensure the delivery of primary palliative care while considering the far-reaching implications of this public health crisis. With palliative care skills fully integrated into oncology nursing practice, health organizations and cancer centers will be better equipped to meet the holistic needs of patients with cancer and their families receiving care for serious illness, including improved attention to physical, psychosocial, cultural, spiritual, and ethical considerations.

Keywords: primary palliative care, quality of life, COVID-19, pandemic, end-of-life care

The COVID-19 crisis is having profound consequences on the integrity of healthcare delivery and the nursing workforce around the world. Resource constraints, ethical dilemmas, spiritual and existential distress, increased visibility of health inequities, and social isolation are just some of the issues affecting patient, family, caregiver, and palliative care–related outcomes (Abedi et al., 2020; Dawson et al., 2020; Emanuel et al., 2020; Ferrell et al., 2020; Marmot, 2020; Morley et al., 2020). Patients with cancer are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and at increased risk for serious symptomatic complications and rapid physical decline (Mehta et al., 2020). In addition, there are a number of factors that may influence oncology nurses’ care of patients with cancer in the context of COVID-19, including the stage and aggressiveness of the patient’s cancer, the availability of resources for care (e.g., personal protective equipment, staffing, medications), increasing COVID-19–related anxiety, and the management of cancer amid an overwhelmed healthcare system.

The purpose of this article is to equip clinical oncology nurses working in all settings with primary palliative care skills during the COVID-19 pandemic. The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC, 2020a) is an international palliative care education initiative that has empowered more than one million nurses globally with palliative care skills and competencies. This article provides an evidence-based resource for primary palliative oncology nursing created by an ELNEC task force in response to the pandemic.

Palliative Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The increasing global prevalence of COVID-19 and associated deaths have called urgent attention to the critical nature of integrating palliative care throughout the healthcare continuum (De Lima et al., 2020; Radbruch et al., 2020). Palliative care is a critical component of high-quality health care, and access to it has become more significant during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available, affordable, accessible, and culturally acceptable health care is a right of all individuals, regardless of financial, social, political, geographic, racial, religious, or other considerations (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2016; International Council of Nurses, 2011; Knaul et al., 2018). Universal palliative care access is recognized as a core aspect of universal health coverage (World Health Organization, 2014, 2019).

With more than 114 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide (Johns Hopkins University, 2020), oncology nurses are integral to alleviating serious health-related suffering and optimizing quality of life for patients facing competing priorities related to the pandemic and the broad impacts of cancer. Throughout COVID-19, oncology nurses have had to promote simultaneous discussions about cancer management in the context of this public health emergency, mitigate the risk for contracting COVID-19, and plan for subsequent health-related crises. Advance care planning has become particularly important during the pandemic because of visitor restrictions and other factors that may challenge the integrity of the cancer care experience.

To ensure person-centered oncology care throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative to provide primary palliative nursing education on communication skills for advance care planning and general pain and symptom management (Mehta & Smith, 2020). The following recommendations can be applied to oncology nursing:

Increase palliative care education for oncology nurses to ensure palliative care begins at the time of diagnosis and encompasses additional concerns related to COVID-19.

Safely expand the scope of practice and leadership roles commensurate with training and education to support oncology nurses on the front line in clinics and acute care settings to provide palliative care within the changing landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Provide resources and support for oncology nurses’ self-care and to build resilience.

Promote a palliative care lens in oncology nursing science and research as it relates to caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Ensure palliative care priorities are integrated early and throughout the cancer care continuum, with particular attention paid to the COVID-19 context.

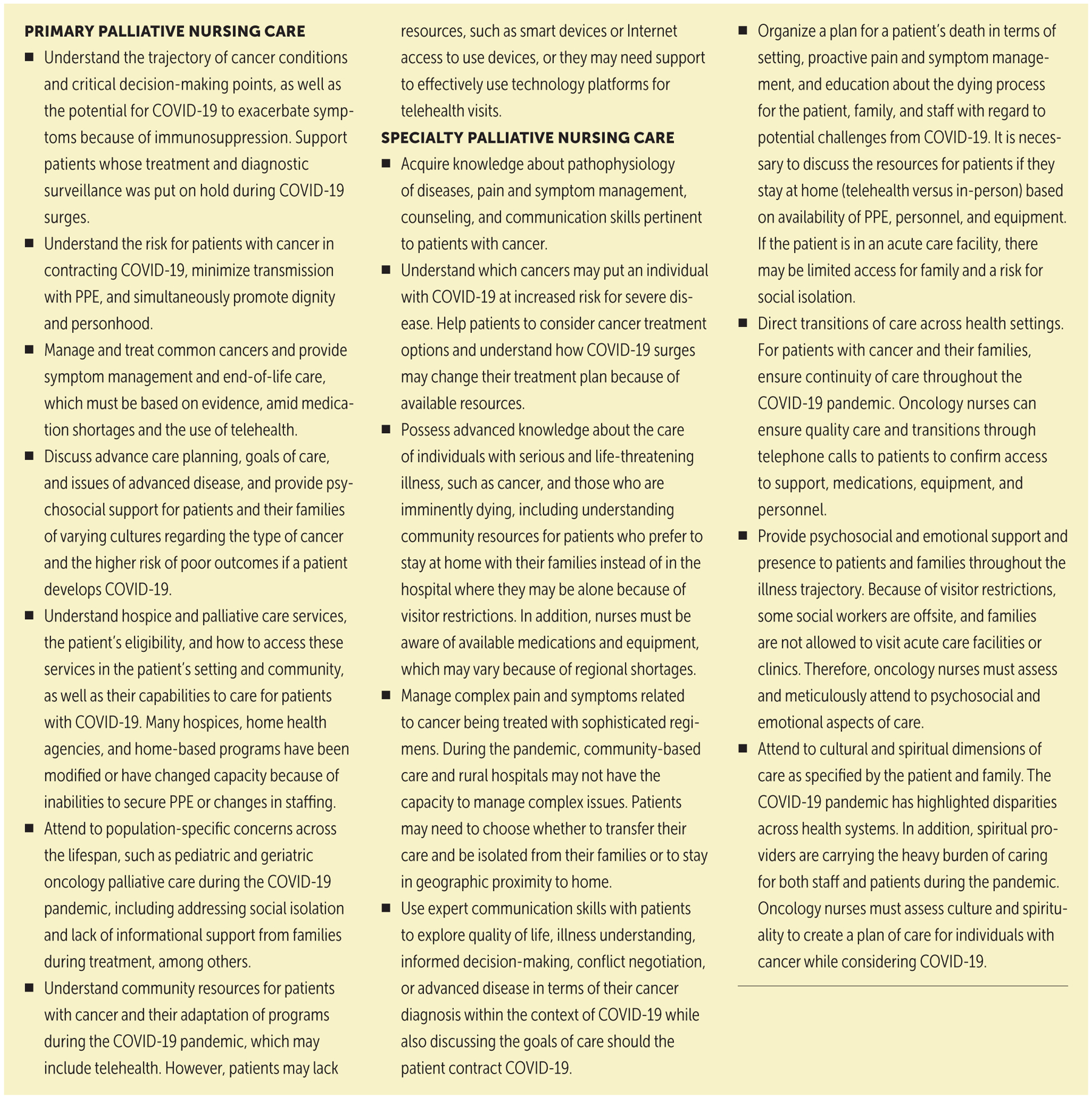

All patients with cancer require primary palliative care to systematically address physical, psychological/psychiatric, social, spiritual/religious/existential, cultural, end-of-life, and legal and ethical needs through an inherently interprofessional approach to care planning and delivery (Chow & Dahlin, 2018; Dahlin, 2015; Ferrell et al., 2017; Kaasa et al., 2018; Oncology Nursing Society [ONS], 2019; Rosa et al., 2020). Primary palliative care should be prioritized by all members of the healthcare team and begin at diagnosis of cancer (American Society of Clinical Oncology, n.d.; Kaasa et al., 2018; National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care [NCHPC], 2018; ONS, 2019). In addition, with the potential risk for contracting COVID-19, all individuals deserve to have clinical discussions about the virus as a potentially fatal condition with significant debilitating sequalae. Primary palliative nursing competencies for the RN and advanced practice RN should be integrated into all aspects of oncology nursing (American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2016, 2019; ELNEC, 2020b; ONS, 2019). Oncology nurses need coaching and mentoring around communication, common pain and symptom management, community resources, and planning within the confines of COVID-19. By assessing, evaluating, and deliberately striving to meet palliative needs early in the care plan of patients with cancer, oncology nurses play a key role in ensuring effective symptom management, eliciting patient values and preferences, providing advance care planning and documentation, and partnering with palliative specialists when and where available, among other vital interventions (Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association [HPNA], 2020) (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. PRIMARY AND SPECIALTY PALLIATIVE ONCOLOGY NURSING CARE DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC.

PPE—personal protective equipment

Note. Based on information from American Nurses Association & Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 2017; Dahlin, 2015.

ELNEC Resources for Primary Oncology Nursing

To best support nurses during the pandemic, ELNEC (2020b) formed a task force of palliative nursing specialists to create evidence-based tools and resources to aid in optimizing palliative care delivery across a host of settings (www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/COVID-19). These resources can be easily accessed online and downloaded for personal, institutional, educational, or patient and stakeholder education purposes to advance the field of palliative nursing. Through a series of webinars, video lectures, guides, and other presentation forums, the ELNEC team provides direction for palliative nurses on symptom management; loss, grief, and bereavement; meeting cultural needs; communication; end-of-life care; nursing self-care; and the delivery of primary palliative care during a disaster.

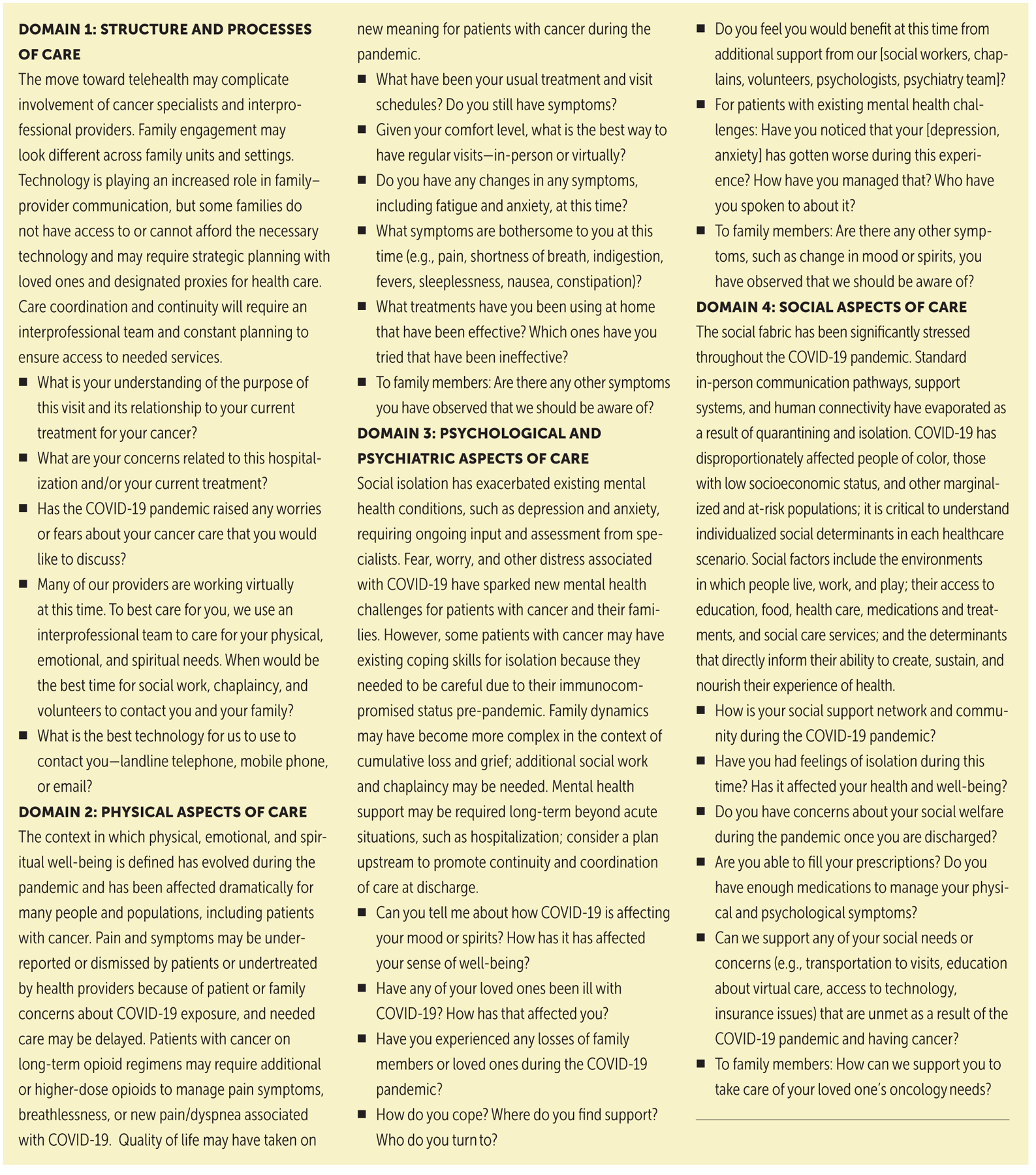

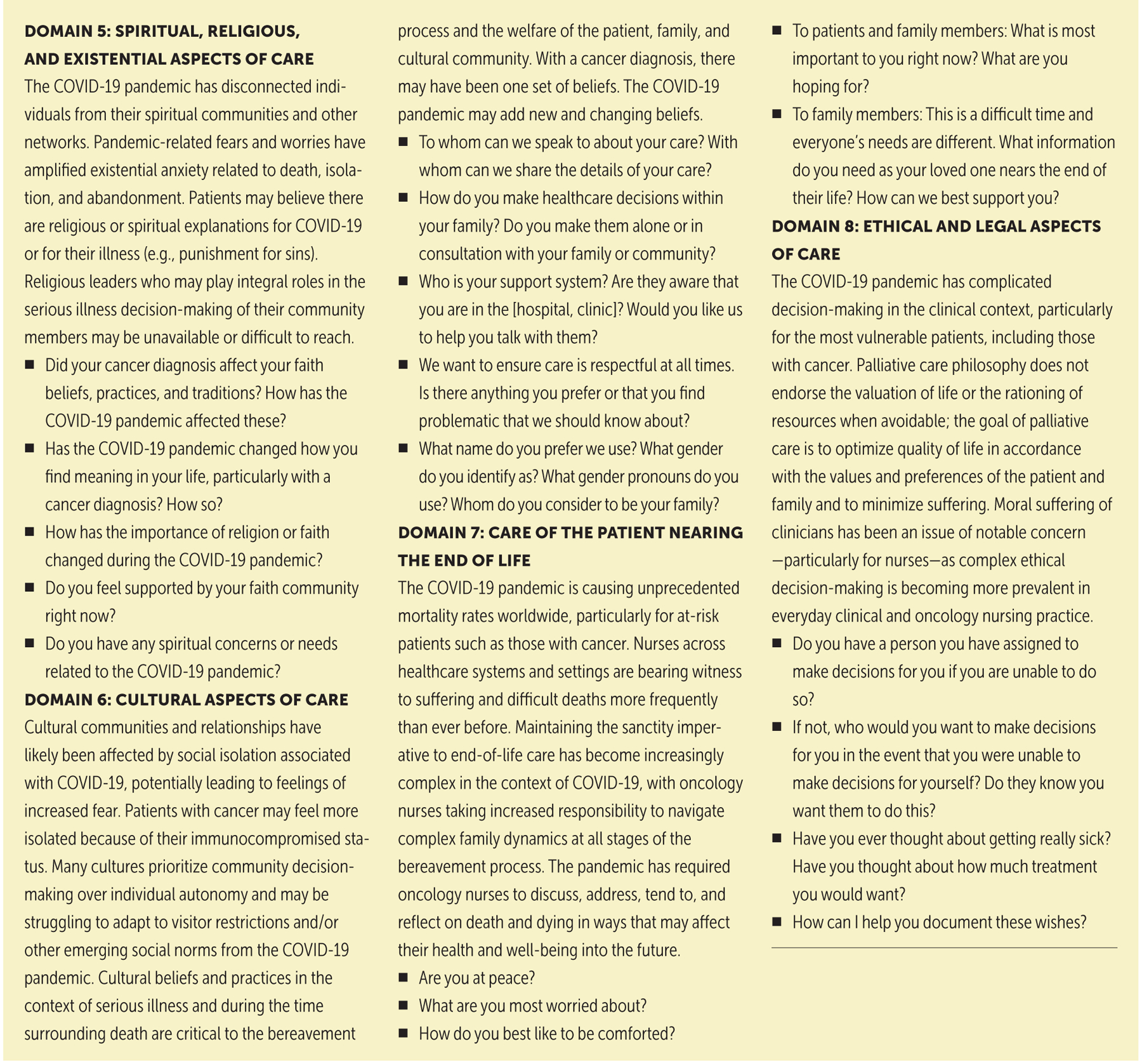

Primary palliative nursing is essential to ensuring person-centered, holistic care in the COVID-19 oncology milieu (ELNEC, 2020b; HPNA, 2020; ONS, 2019). A series of infographics were created to provide strategic applications of primary palliative oncology nursing across all eight domains of quality palliative care according to NCHPC (2018) clinical practice guidelines. A modified version of the primary palliative nursing tools was compiled for this article to guide oncology nurses in delivering primary palliative nursing care safely, critically, and efficiently to all patients, particularly those receiving acute care services (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. PRIMARY ONCOLOGY NURSING CONCERNS AND QUESTIONS FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILY MEMBERS ACROSS THE DOMAINS OF PALLIATIVE CARE DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC.

Note. Based on information from End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium, 2020b; Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 2020; Oncology Nursing Society, 2019.

Alleviating Suffering

Suffering for patients can be relieved by addressing the eight domains of palliative care strategically and regularly and by integrating primary palliative care skills. This is more challenging during the COVID-19 pandemic because of the added stress and concerns it brings to oncology care.

Tenets identified by Ferrell and Coyle (2008) can assist with guiding the integrity of nursing practice during COVID-19 while addressing the suffering experience of those with serious illnesses. Examples of primary palliative oncology nursing interventions to alleviate suffering include the following:

Assessing patients for the suffering associated with multiple losses at the intersection of cancer and the psychosocial consequences of COVID-19: Expert communication skills are necessary to promote connection and mitigate isolation (e.g., use of therapeutic verbal and nonverbal techniques).

Being present to patients’ search for meaning or answers during their illness: Oncology nurses must listen to patients with compassion and collaborate with appropriate interprofessional team members; the importance of empathically bearing witness to the patient and family experience cannot be understated.

Considering all potential sources of suffering: Oncology nurses must assess for hopelessness, provide spiritual care support, acknowledge spiritual distress, and consult with spiritual care specialists.

Acknowledging and attending to suffering is not only a goal of primary palliative care but an ethical foundation of nursing (ANA, 2015; Ferrell & Coyle, 2008). Considering these aspects of suffering can inform oncology nurses about the broad and sometimes unseen variables that cause distress and disharmony at physical, psychological, social, and spiritual levels.

Case Study

Mary is a 54-year-old woman with metastatic colon cancer. During a previous clinic visit, her oncology nurse initiated conversations about advance care planning related to her cancer diagnosis and COVID-19. However, Mary had been reluctant to talk about any disease progression.

Mary is admitted with symptoms of recurrent shortness of breath and tests positive for COVID-19. Her respiratory symptoms require supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula, and she is placed on airborne precautions. Hospital visitors are restricted because of the pandemic. After several days, Mary’s symptoms worsen, requiring placement of a nasogastric tube and increased oxygen support. Most providers are working remotely or decreasing face-to-face interactions with patients and relying on the expertise of the bedside oncology nurses to facilitate symptom assessment and goals-of-care conversations. Mary expresses that she is afraid of dying and asks her night shift nurse, Ben, “What has my life really meant?” Ben and his team understand their vital role in ensuring a quality end-of-life experience for Mary and her loved ones. They apply a systematic approach to effectively meet her and her families’ palliative care needs within the limitations of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mary died a few days following her admission. Her oncology nurses, in consultation with the palliative care team, made recommendations based on the rapport built with Mary and her family through primary palliative nursing. The oncology nurses, including Ben, were able to advocate for Mary’s family to visit once she decided to decline further disease-modifying treatment and focus exclusively on symptom management. They provided anticipatory bereavement support for the family, spiritual care for Mary, and ensured meticulous attention to Mary’s preferences throughout the rest of her life. The nursing team felt satisfied that their care allowed Mary to have a dignified death with minimal physical, psychosocial, and spiritual suffering.

Conclusion

Holistic, humanistic care has long been the foundation of palliative care. All oncology nurses are in a unique position to advocate for patients regarding access to and the delivery of quality palliative care (ONS, 2019). Oncology nurses must be educated and trained to incorporate palliative care skills into their clinical practice given the chronic nature and severity of many cancers, as well as to consider the trajectory of various cancers, manage common pain and other symptoms, and initiate advance care planning about goals of care. With the COVID-19 pandemic, oncology nurses must have additional palliative care training to advocate for their patients with cancer and help them to make informed choices about their care.

COVID-19 has increased anxiety and isolation and reduced contact to healthcare providers, support systems, and sometimes family. These factors necessitate that oncology nurses serve as skilled communicators to help elicit patient’s values and preferences for cancer care and then determine how those values and preferences might change if the patient develops COVID-19. ELNEC has developed tools that help oncology nurses have easy access to pain and symptom management evidence, communication techniques, and cultural sensitivity education. These resources empower oncology nurses to attend to the physical, psychosocial, cultural, spiritual, and ethical considerations of patients with cancer and other serious illnesses.

AT A GLANCE.

Palliative care is an integral component of comprehensive cancer care throughout the illness trajectory.

COVID-19 has increased the burden of serious health-related suffering for patients with cancer, requiring enhanced primary palliative oncology nursing skills.

Oncology nurses should integrate primary palliative care skills while considering the myriad psychosocial, physical, and spiritual consequences of COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

The authors take full responsibility for this content. The authors received grant funding for ELNEC-COVID-19 activities from the Cambia Health Foundation and the Pfizer Foundation. Rosa, Finlayson, and Wisniewski are supported by funding from a National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Support Grant (P30 CA008748). Rosa is also supported by the NCI (T32 CA009461).

REFERENCES

- Abedi V, Olulana O, Avula V, Chaudhary D, Khan A, Shahjouei S, … Zand R (2020). Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 10.1007/s40615-020-00833-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2016). CARES: Competencies and recommendations for educating undergraduate nursing students: Preparing nurses to care for the seriously ill and their families. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/ELNEC/PDF/New-Palliative-Care-Competencies.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2019). Preparing graduate nursing students to ensure quality palliative care for the seriously ill and their families. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/ELNEC/PDF/Graduate-CARES.pdf

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. (2016). The nurse’s role in ethics and human rights: Protecting and promoting individual worth, dignity, and human rights in practice settings [Position statement]. https://bit.ly/2MiCRuR

- American Nurses Association & Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. (2017). Call for action: Nurses lead and transform palliative care. https://bit.ly/304vKta

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. (n.d.). Palliative care in oncology. https://www.asco.org/practice-policy/cancer-care-initiatives/palliative-care-oncology

- Chow K, & Dahlin C (2018). Integration of palliative care and oncology nursing. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 34(3), 192–201. 10.1016/j.soncn.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin C (2015). Palliative care: Delivering comprehensive oncology nursing care. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 31(4), 327–337. 10.1016/soncn.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A, Isaacs D, Jansen M, Jordens C, Kerridge I, Kihlbom U, … Skowronski G (2020). An ethics framework for making resource allocation decisions within clinical care: Responding to COVID-19. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 17(4), 729–755. 10.1007/s11673-020-10007-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lima L, Pettus K, Downing J, Connor S, & Marston J (Eds). (2020). Palliative care and COVID-19 series—Briefing notes compilation. IAHPC Press. https://bit.ly/3e4 [Google Scholar]

- EyaZ Emanuel L, Solomon S, Fitchett G, Chochinov H, Handzo G, Schoppee T, & Wilkie D (2020). Fostering existential maturity to manage terror in a pandemic. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 24(2), 211–217. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium. (2020a). ELNEC curricula. https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/About/ELNEC-Curricula

- End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium. (2020b). ELNEC support for nurses during COVID-19. https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/COVID-19

- Ferrell BR, & Coyle N (2008). The nature of suffering and the goals of nursing. Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Handzo G, Picchi T, Puchalski C, & Rosa WE (2020). The urgency of spiritual care: COVID-19 and the critical need for whole-person palliation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(3), e7–e11. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, & Smith TJ (2017). Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. Journal of Oncology Practice, 13(2), 119–121. 10.1200/JOP.2016.017897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. (2020). Palliative nursing: Scope and standards of practice (6th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses. (2011). Nurses and human rights [Position statement]. https://bit.ly/2MoOH6U [DOI] [PubMed]

- Johns Hopkins University. (2020). COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. http://bit.ly/3dHmPWK

- Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, Albreht T, Anderson R, Bruera E, … Lundeby T (2018). Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncology, 19(11), e588–e653. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, De Lima L, Bhadelia A, Jiang Kwete X, … Zimmerman C (2018). Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—An imperative of universal health coverage: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet, 391(10128), 1391–1454. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M (2020). Society and the slow burn of inequality. Lancet, 395(10234), 1413–1414. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30940-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AK, & Smith TJ (2020). Palliative care for patients with cancer in the COVID-19 era. JAMA Oncology, 6(10), 1527–1528. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, Cole D, Goldfinger M, Acuna-Villaorduna A, … Verma A (2020). Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discovery, 10(7), 935–941. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley G, Grady C, McCarthy J, & Ulrich CM (2020). COVID-19: Ethical challenges for nurses. Hastings Center Report, 50(3), 35–39. 10.1002/hast.1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (4th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Oncology Nursing Society. (2019). Palliative care for people with cancer [Position statement]. https://www.ons.org/make-difference/ons-center-advocacy-and-health-policy/position-statements/palliative-care-people

- Radbruch L, Knaul FM, De Lima L, de Joncheere C, & Bhadelia A (2020). The key role of palliative care in response to the COVID-19 tsunami of suffering. Lancet, 395(10235), 1467–1469. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30964-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa WE, Finlayson CS, & Ferrell BR (2020). The cancer nurse as primary palliative care agent during COVID-19. Cancer Nursing, 43(6) 431–432. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/158962 [DOI] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Political declaration of the high-level meeting on universal health coverage. https://www.un.org/pga/73/event/universal-health-coverage