Abstract

Aims

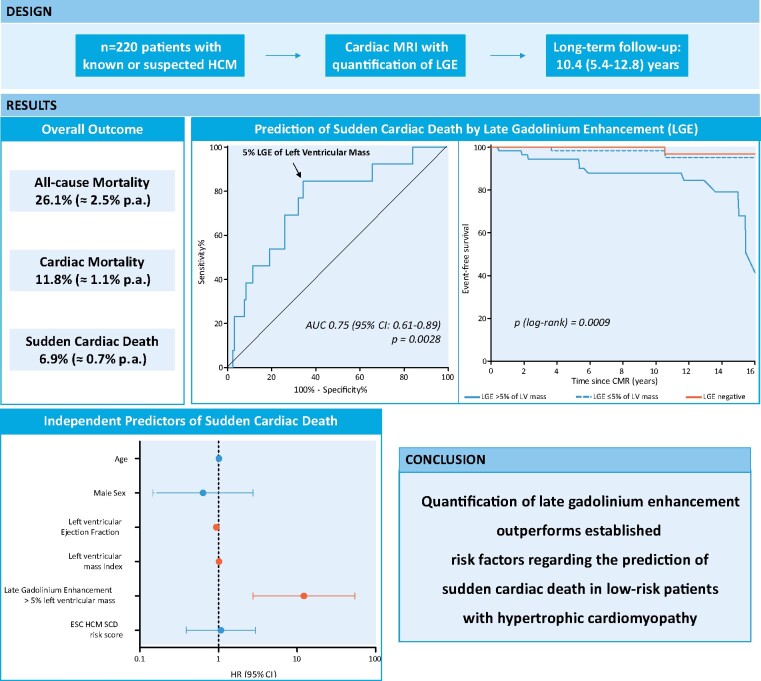

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is an appalling complication of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). There is an ongoing discussion about the optimal SCD risk stratification strategy since established SCD risk models have suboptimal discriminative power. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) for SCD risk stratification compared to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) SCD risk score and traditional risk factors in an >10-year follow-up.

Methods and results

Two hundred and twenty consecutive patients with HCM and LGE-CMR were enrolled. Follow-up data were available in 203 patients (median age 58 years, 61% male) after a median follow-up period of 10.4 years. LGE was present in 70% of patients with a median LGE amount of 1.6%, the median ESC 5-year SCD risk score was 1.84. In the overall cohort, SCD rates were 2.3% at 5 years, 4.8% at 10 years, and 15.7% at 15 years, independent from established risk models. An LGE amount of >5% left ventricular (LV) mass portends the highest risk for SCD with SCD prevalences of 5.5% at 5 years, 13.0% at 10 years, and 33.3% at 15 years. Conversely, patients with no or ≤5% LGE of LV mass have favourable prognosis.

Conclusions

LGE-CMR in HCM patients allows effective 10-year SCD risk stratification beyond established risk factors. LGE amount might be added to established risk models to improve its discriminatory power. Specifically, patients with >5% LGE should be carefully monitored and might be adequate candidates for primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator during the clinical long-term course.

Keywords: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, CMR, LGE, risk stratification, sudden cardiac death

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the most appalling complication in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Therefore, adequate risk assessment for SCD is an indispensable factor in the clinical management of these predominantly young to middle-aged patients. In contrast to secondary prevention of SCD, in which implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implant has a Class I indication in both American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA),1 and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) HCM guidelines,2 ICD insertion for primary prevention of SCD is much more ambiguous. Presently, the ESC guidelines recommend the use of a risk score (HCM risk-SCD score) for estimation of the 5-year risk suffering from SCD for decision-making of primary ICD implant.2 If the risk is low (<4%), ICD is not indicated. If the risk is intermediate (4–6%) ICD may be considered, and >6% risk an ICD should be considered. However, several studies suggest that this ESC risk score may be not sufficient to identify those patients at highest risk for SCD.3,4 Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) with the technique of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) for myocardial tissue characterization has been suggested to refine the risk evaluation of SCD in HCM.5,6 In HCM myocardial fibrosis can occur as a potential substrate for malignant ventricular arrhythmia. This fibrosis can be diagnosed by LGE with high accuracy.7 However, since more than 50% of HCM patients demonstrate LGE,5,8–10 the amount of LGE may be a more accurate indicator for SCD than its presence per se.8,9 Moreover, most HCM studies including advanced imaging techniques such as CMR have median follow-up data about 5 years, but extended follow-up data (>10 years) are very rare. Therefore, we performed an extended long-term follow-up CMR study in HCM patients to identify potential CMR parameters for patients at risk for SCD. Furthermore, we sought to investigate the prognostic value of LGE quantification regarding SCD in comparison with the established ESC HCM Risk-SCD score and traditional risk factors.

Methods

Patient population

Two-hundred and twenty consecutive patients presenting for workup of known or suspected HCM were prospectively enrolled between January 2003 and April 2008 and underwent LGE-CMR. HCM was diagnosed (or confirmed) by the presence of a non-dilated and hypertrophied left ventricle on two-dimensional CMR (maximal wall thickness ≥15 mm in adult index patients or ≥13 mm in adult relatives of HCM patients) in the absence of another disease that could account for the hypertrophy.11 Patients with coronary artery disease, aortic stenosis, amyloidosis, systemic hypertension, or contraindications to CMR were not included. We also did not include patients with previous septal ablation or myectomy.

The cohort of this study was part of a previous study,5 in which we found that in a population of low or asymptomatic HCM patients, the presence of scar indicated by CMR is a good independent predictor of all-cause and cardiac mortality in a follow-up period of 3 years. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki, the local ethics committee of the University of Tübingen (Germany) has approved the research protocol and informed consent has been obtained from the subjects.

CMR protocol

Electrocardiography-gated CMR imaging was performed in breath-hold using a 1.5T Magnetom Siemens Sonata (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) in line with the Society of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance/European Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance recommendations.12 Both cine and LGE short-axis CMR images were prescribed every 10 mm (slice thickness 6 mm) from base to apex. Cine CMR was performed using a steady-state free precession sequence. LGE images were acquired on average 5–10 min after contrast administration using segmented inversion recovery gradient echo sequence,13 constantly adjusting inversion time.14 The contrast dose (gadodiamide or gadopentetate-dimeglumine) was 0.15 mmol/kg.

CMR analysis

Cine images were evaluated as described previously.5 In brief, endocardial and epicardial borders were outlined on the short-axis cine images. Volumes and ejection fraction (EF) were derived by summation of epicardial and endocardial contours. The left ventricular (LV) mass was calculated by subtracting endocardial from epicardial volume at end-diastole and multiplying by 1.05 g/cm3.15 For post-processing and quantification of the LGE images dedicated software (Mass, Medis, The Netherlands) was used according to Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance standards.16 All images were analysed by consensus of two experienced readers blinded to the results of clinical data. Epicardial and endocardial contours were placed manually on all LGE images. LGE was defined as an image intensity level ≥2 standard deviations (SD) above the mean of the remote myocardium which has been established as gold standard in the assessment of scarring by comparison to histology and gross pathology in humans.17,18 The amount of LGE was expressed as percentage of myocardial LV mass.

Clinical follow-up, variables, and endpoints

Clinical follow-up was performed using a standardized questionnaire. In case of a suspected event, all necessary medical records were obtained and reviewed by the authors acting as endpoint committee. Death notification was confirmed by observation of death certificate or verified with a family member or treating physician, respectively.

The following clinical risk factors for SCD were assessed: (i) history of cardiac arrest; (ii) history of spontaneous ventricular tachycardia; (iii) extreme hypertrophy (maximum wall thickness ≥30 mm); (iv) family history of SCD (≥1 first-degree relative, <50 years of age); (v) unexplained syncope; and (vi) LV outflow tract gradient >30 mmHg measured by continuous-wave Doppler as a surrogate parameter for obstruction.11

Based on the 2014 European HCM guidelines, we calculated % 5-year risk of SCD as previously described.19

There were three pre-specified primary endpoints: (i) all-cause death, defined as death from any cause, including aborted SCD; (ii) cardiac death, defined as death from all cardiac causes, including SCD, heart failure, and aborted SCD; and (iii) SCD, defined as unexpected arrest of presumed cardiac origin within 1 h after onset of any symptoms that could be interpreted as being cardiac in origin. Aborted SCD was considered as resuscitation after cardiac arrest defined as performance of the physical act of cardioversion, appropriate ICD shocks, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a patient who remained alive 28 days later. For appropriate ICD shocks, defibrillator discharges were considered appropriate and included automatic defibrillation shocks triggered by ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation and documented by stored intracardiac electrocardiographic data as previously described.5

Statistical analysis

Absolute numbers and percentages were computed to describe the patient population. Variables are presented as mean ± SD, medians with interquartile range (IQR) or absolute numbers (%) as appropriate. Categorical values were compared by Fisher’s exact test, the t-test was used to compare continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were calculated for visualizing the cumulative survival of patients with and without LGE. Time to event was measured from the date of CMR exam. A log-rank test was performed to compare both survival curves. Multivariable Cox hazards regression analyses were performed to determine independent predictors of mortality. The following variables were included in the Cox regression analyses: age, sex, LV ejection fraction (LVEF), LV mass index, LGE >5% (of LV mass), and the ESC HCM SCD risk score (only for SCD). A two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software (San Diego, CA, USA) or SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient and CMR characteristics

Overall, 203 of all 220 patients were available for clinical follow-up at a median of 10.4 (5.4–12.8) years, yielding a follow-up rate of 92.3%. The remaining n = 17 patients were lost due to no contact. Baseline characteristics are illustrated in Table 1. At time of CMR, patients were at median 58 years old and mildly symptomatic. Median LVEF was preserved (71%), median maximum wall thickness was 19 mm, n = 60 patients (30%) demonstrated LV outflow tract obstruction. LGE was present in n = 143 patients (70%) with an overall low LGE amount (1.6% of LV mass) predominantly located in the area of hypertrophy, Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| All patients (n = 203) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 (46–68) |

| Sex (male) | 123 (61) |

| Symptoms | |

| Chest pain | 25 (12) |

| NYHA I/II/III/IV | 3 (1) |

| NYHA II | 40 (20) |

| NYHA III | 17 (8) |

| CMR LV function | |

| LVEF (%) | 71 (64–77) |

| LVEDV (mL) | 118 (94–145) |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 82.2 (66.9–96.1) |

| LA size (cm2) | 24.0 (20.2–29.4) |

| Maximum wall thickness (mm) | 19 (16–23) |

| LVOT obstruction | 60 (30) |

| Apical aneurysm | 5 (2) |

| CMR hypertrophy pattern | |

| Septal | 171 (84) |

| Apical | 17 (8) |

| Concentric | 15 (7) |

| CMR LGE | |

| LGE present | 143 (70) |

| LGE mass (g) | 2.6 (0–11.6) |

| LGE (% of LVM) | 1.6 (0–6.6) |

| SCD risk parameters | |

| ESC HCM SCD risk score | 1.84 (1.53–2.21) |

| Max wall thickness >30 mm | 8 (4) |

| History of sustained VT | 11 (5) |

| Family history of SCD | 9 (4) |

| Unexplained syncope | 10 (5) |

| LVOT gradient >30 mmHg | 20 (10) |

Values are represented as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

CMR, cardiovascular magnetic resonance; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LA, left atrium; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVM, left ventricular mass; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

ESC HCM SCD risk score at time of enrolment was 1.84, indicating a low 5-year risk for SCD. Traditional clinical risk factors for SCD were present in a minority of the patients: 20% (one risk factor), 2% (two risk factors), and 1% (three risk factors). No patient had more than three clinical risk factors for SCD.

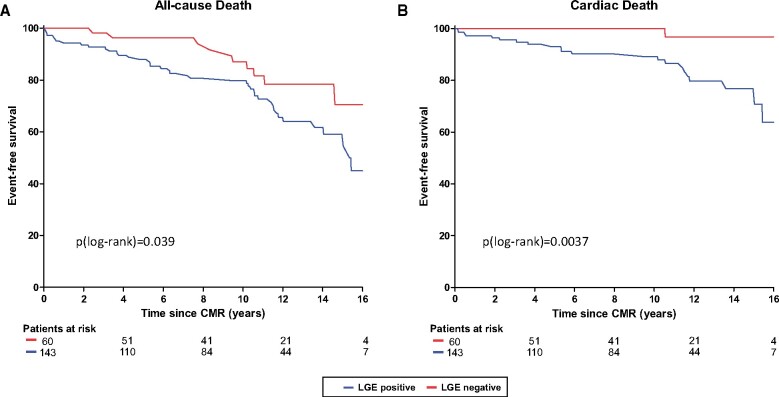

Follow-up results and predictors of mortality

During follow-up, n = 20 patients underwent surgical or interventional relief of LV outflow tract obstruction (n = 8 septal myectomy; n = 12 transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy), and n = 36 patients received an ICD. Overall, n = 53 of 203 patients (26.1%) died. Almost half of these patients (n = 24; 45.3%) suffered from cardiac death, including SCD (n = 14; 26.4%). The other deaths were related to cancer, fatal infections, or accidents. To identify predictors of mortality, patients were divided in patients with no event vs. patients with all-cause death, cardiac death, and SCD, respectively. Patients suffering from all-cause death were older, had larger left atrial size, higher prevalence of LV outflow tract obstruction, and larger amounts of LGE, all P-values <0.05. Patients with cardiac death had impaired LVEF, higher LV mass, larger left atrial size, and both higher prevalence and higher amounts of LGE (Supplementary data online, Table S1). At multivariate Cox regression analysis, several independent predictors of all-cause death could be identified, i.e. age, female sex, LVEF, and LV mass index and LGE >5% of LV mass. For cardiac death, age, LVEF, and LGE >5% LV mass were independent predictors, Table 2. LGE-positive patients were at higher risk suffering from all-cause death or cardiac death than LGE-negative patients, Figure 1.

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis—predictors of mortality

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| All cause death | ||

| Age | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 0.35 (0.18–0.66) | 0.001 |

| LVEF | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.002 |

| LVM index | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.002 |

| LGE >5% (of LVM) | 1.86 (1.05–3.31) | 0.002 |

| Cardiac death | ||

| Age | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.033 |

| Male sex | 0.46 (0.16–1.12) | 0.128 |

| LVEF | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | <0.001 |

| LVM index | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.035 |

| LGE >5% (of LVM) | 4.04 (1.69–9.63) | 0.002 |

| Sudden cardiac death (SCD) | ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.533 |

| Male sex | 0.63 (0.14–2.75) | 0.543 |

| LVEF | 0.93 (0.90–0.97) | 0.003 |

| LVM index | 1.01 (1.001–1.03) | 0.048 |

| LGE >5% (of LVM) | 12.23 (2.75–54.32) | 0.001 |

| ESC HCM SCD risk score | 1.07 (0.38–2.96) | 0.894 |

CI, confidence interval; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HR, hazard ratio; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVM, left ventricular mass. Significant P values are in bold (P <0.05)

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for all-cause and cardiac death. Kaplan–Meier survival curves of patients with HCM divided in all-cause mortality (A), and cardiac mortality (B). Note that LGE-negative HCM patients had a better outcome during this >10-year follow-up, foremost regarding cardiac death. CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement.

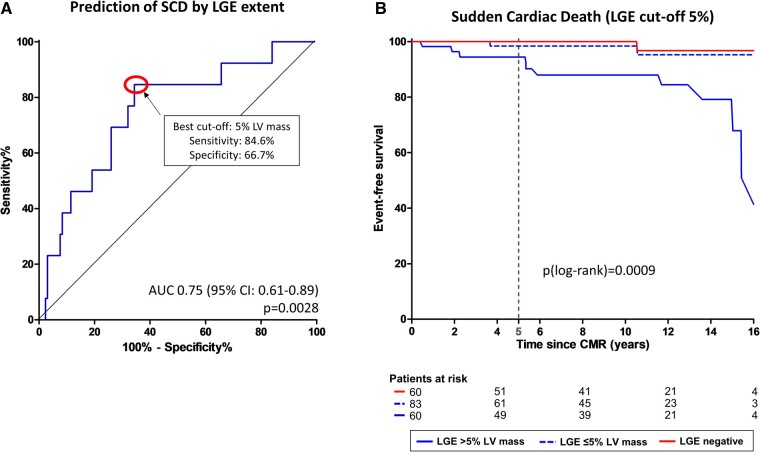

Prediction of SCD

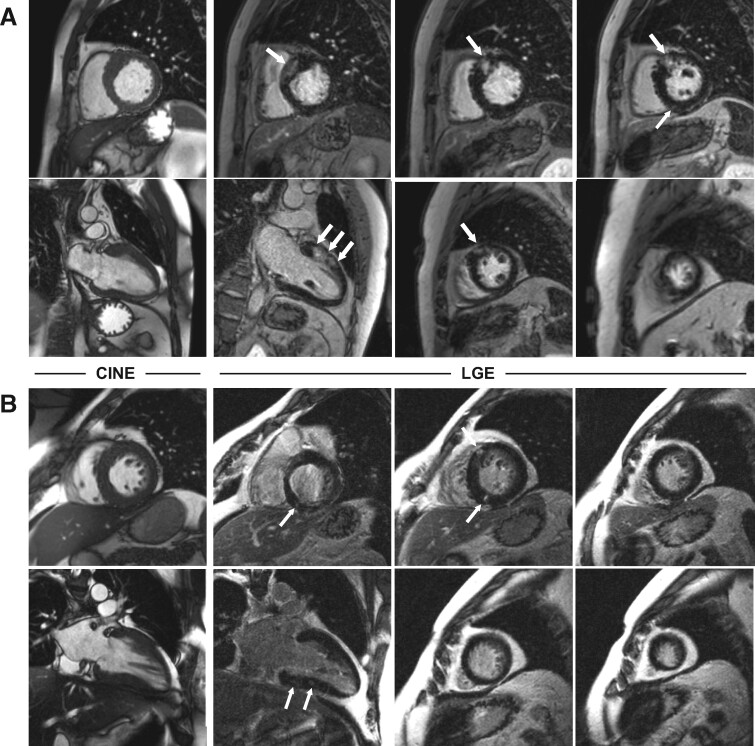

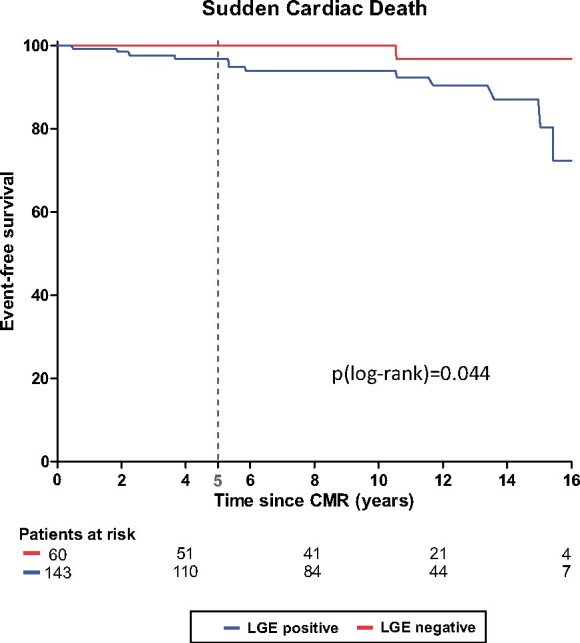

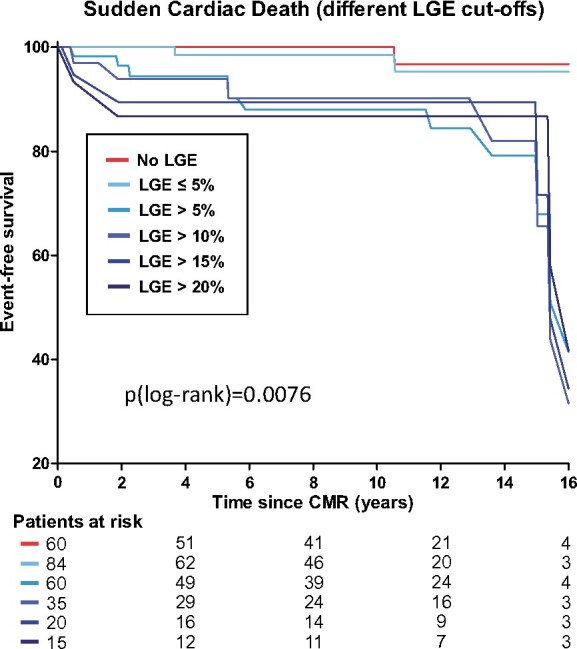

Patients suffering from SCD demonstrated lower LVEF and higher LV mass. Furthermore, SCD patients were more frequently LGE-positive, Figure 2, and displayed larger amounts of LGE, Supplementary data online, Table S1 and Figure 3. Receiver-operating curve analysis revealed an LGE extent >5% as the best threshold to predict SCD, Figure 4A. Hence, patients with an LGE amount >5% (of LV mass) more often suffered from SCD than HCM patients with an LGE amount ≤5% (of LV mass), Figure 4B. Moreover, patients with LGE ≤5% (of LV mass) seem to have similar prognosis with regard to SCD as HCM patients without LGE, P = 0.614, Figure 4B. Conversely, neither traditional clinical risk factors (for SCD) nor the HCM SCD risk score differed significantly between patients suffering from SCD vs. patients without SCD. On multivariate analysis, besides LVEF [hazard ratio 0.938 (0.900–0.978)] and LV mass [hazard ratio 1.018 (1.001–1.037)], LGE >5% of LV mass [hazard ratio 12.232 (2.754–54.327)] was most predictive for SCD, Table 2. Looking at the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of LGE for SCD revealed a high NPV (0.98) but a low PPV (0.09) of the presence of LGE alone, Table 3. As suggested by the receiver-operating curve (Figure 4A), a threshold >5% LGE (of LV mass) seems to be the optimal threshold to discriminate high risk from low-risk SCD patients with an increased PPV (0.18) without decreasing the high NPV (0.98) compared to the presence of LGE alone. Higher thresholds for LGE (%LV mass) further increase the PPV, but at the cost of a lower NPV, Table 3. Although HCM patients with excessive amounts of LGE have a higher SCD risk compared to patients with no LGE (or LGE ≤5% LV mass), Kaplan–Meier curves between different LGE amounts beyond the 5% LGE threshold were comparable, P = 0.99, Figure 5.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for sudden cardiac death (SCD). SCD is rare (especially in LGE-negative patients) but increases over time. The dashed line indicates a low SCD prevalence at 5 years (2.3%), confirming the calculated overall 5-year SCD risk (1.84%) of this cohort using the ESC HCM risk score.

Figure 3.

Representative CMR images of two patients with HCM and different amount of LGE. (A) 35-year old male patient and >5% LGE (9.1%) who suffered sudden cardiac death during the follow-up period. (B) 43-year old male patient with <5% LGE (1.8%) and no event during follow-up.

Figure 4.

Prediction of SCD by LGE extent. Receiver-operating curve (ROC) analysis revealed an LGE extent >5% as the best threshold to predict SCD (A). Hence, patients with a LGE amount >5% (of LV mass) suffered more often from SCD than HCM patients with a LGE amount ≤5% (of LV mass) (B). Moreover, patients with LGE ≤5% (LV mass) had a similar prognosis with regard to SCD as HCM patients without LGE, P = 0.614 (B).

Table 3.

Positive and negative predictive value of LGE in HCM

| n (%) | PPV | NPV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sudden cardiac death (SCD) | |||

| Presence of LGE | 143 (66%) | 0.09 | 0.98 |

| LGE >5% | 60 (30%) | 0.18 | 0.98 |

| LGE >10% | 35 (17%) | 0.20 | 0.96 |

| LGE >15% | 20 (10%) | 0.25 | 0.95 |

| LGE >20% | 15 (7.4%) | 0.27 | 0.95 |

| LGE >30% | 9 (4.4%) | 0.33 | 0.94 |

LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Figure 5.

Prediction of SCD by different LGE cut-offs. Kaplan–Meier (KM) curves for different LGE amounts beyond the 5% LGE threshold were comparable, P = 0.99.

Important to note, that in our initial low-risk SCD population the calculated 5-year SCD risk of 1.84% (according to the ESC HCM risk-SCD) parallels the observed 5-year SCD incidence of 2.3%, Figure 2 (dashed line at 5 years) and Table 4. However, we report substantial increase of SCD after 10 and 15 years, respectively: SCD risk increases from 4.8% at 10 years to 15.7% at 15 years. Focusing on patients with >5% LGE (of LV mass), SCD risk increases from 5% at 5 years to 13.0% at 10 years and 33.3% at 15 years. The number-needed-to-treat to save a patient with >5% LGE from SCD by ICD implant decreases from 18.0 at 5 years to 7.7 at 10 years, and 3.0 at 15 years, Table 4.

Table 4.

Numbers needed to treat with ICD to potentially save one patient with SCD at 5, 10, and 15 years

| Follow-up | All patients (n = 203) |

Patients with LGE >5% (n = 60) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available patientsa | SCD events | NNT | Available patientsa | SCD events | NNT | |

| At 5 years | 173 | 4 (2.3%) | 43.5 | 54 | 3 (5.5%) | 18.0 |

| At 10 years | 146 | 7 (4.8%) | 20.8 | 46 | 6 (13.0%) | 7.7 |

| At 15 years | 70 | 11 (15.7%) | 6.4 | 24 | 8 (33.3%) | 3.0 |

LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; NNT, number needed to treat; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

Number of patients with 5, 10, or 15 years of follow-up excluding those with non-SCD-death.

Discussion

This is the first >10-year follow-up study in HCM patients evaluating the predictive value of LGE-CMR for SCD compared to the ESC SCD risk score and traditional SCD risk factors. Classified as a low-risk SCD group by the ESC risk score, our results confirm a low SCD prevalence at 5 years (2.3%). However, we observed significant increase of SCD after 10 years (4.8%) and 15 years (15.7%). An LGE amount of >5% (of LV mass) portends a higher risk for SCD, increasing the risk from 5.5% at 5 years to 13.0% at 10 years and 33.3% at 15 years. Conversely, patients with no or ≤5% LGE amount seem to have a favourable prognosis. Our findings underscore the unmet need of further predictors to identify patients at highest risk for SCD who subsequently should be offered an ICD during the clinical course. In our study, neither ESC HCM risk-SCD nor traditional clinical risk factors identified those patients at highest risk for SCD at a 10- and 15-year follow-up. Therefore, we suggest extending established risk models for SCD by the addition of LGE-CMR amount as a risk modifier to refine the >10-year risk of SCD in HCM patients. Specifically, otherwise classified low-risk patients who demonstrate >5% LGE burden on CMR might benefit from closer monitoring and might nevertheless be adequate candidates for primary preventive ICD.

Prediction of SCD

Since established SCD risk models seem to suffer from low discriminative power, there is ongoing discussion which HCM patients are adequate candidates for primary prevention ICD.3,20 The potential role of CMR-LGE as an arbitrator in HCM patients has previously been investigated by several studies.5,6 Although the presence of LGE per se was associated with an adverse outcome in HCM patients in these studies,5,6 the high prevalence of LGE faces a relatively low overall SCD rate.2,21 Therefore, further investigation of the role of LGE as a predictor for SCD is urgently needed in order to identify those patients who would not benefit from primary prevention ICD in terms of inappropriate shocks and potential complications. Here, the amount of LGE might be a more powerful marker than the LGE presence per se. Chan et al.8 demonstrated increased SCD risk by increasing amounts of LGE in 1293 HCM patients; with an LGE of ≥15% of LV mass demonstrated a two-fold increase in SCD risk in patients who were otherwise considered as low risk. Another study from Mentias et al.9 in 1423 low-/intermediate-risk HCM patients reported that >15% LGE (of LV mass) was independently associated with increased SCD or ICD discharge (hazard ratio 3.04). As a similar finding, SCD patients in our cohort were more frequently LGE-positive, Figure 2, and showed larger amounts of LGE. In contrast to our study, which reports a median follow-up time of 10.4 years, the latter studies had significant shorter follow-up times of 3.3 and 4.7 years, respectively. Similar to the large multicentre Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Registry (HCMR),10 traditional clinical risk factors for SCD were present only in a minority of our patients despite a considerable long-term SCD risk at 10 and 15 years, respectively. Interestingly, neither the number of traditional clinical risk factors (for SCD) nor the ESC HCM SCD risk score differed significantly between patients suffering from SCD vs. patients without SCD.

LGE-threshold for SCD prediction

According to multivariate analysis, LGE >5% of LV mass portends the highest hazard ratio for SCD [hazard ratio 12.232 (2.754–54.327)], underlining the important role of LGE in risk stratification of HCM patients, Table 2. Of note, the NPV for LGE is by far higher than its PPV, Table 3. Therefore, focusing on the presence of LGE per se is not sufficient for risk stratification since LGE is a common finding in the routine work-up of HCM patients (prevalence in our cohort 70%),17,22 which contrasts a low SCD prevalence, explaining its overall low PPV. Median LGE amount (1.6%) was low in our cohort, which matches results from other cohorts.10,22 Therefore, the definition of a critical LGE-threshold for SCD prediction is crucial if LGE should act as an arbitrator where uncertainty remains about primary preventive ICD implant. Obviously, patients with excessive LGE amounts as a marker of myocardial damage predispose to rhythm disturbances and might end up with SCD,8,9 which is also supported by our data (Figure 5). However, since excessive amounts of LGE are rare in HCM patients,10 a lower threshold of critical LGE amount seems to be more reasonable for a real-world setting.

Receiver-operating curve analysis revealed an LGE extent >5% as the best cut-off to predict SCD, Figure 4A. The number-needed-to-treat to save a patient with >5% LGE from SCD by ICD implant decreases from 18.0 at 5 years to 7.7 at 10 years, and 3.0 at 15 years, Table 4.

Conversely, patients with LGE ≤5% (LV mass) seem to have similar prognosis with regard to SCD than HCM patients with no LGE, addressing the high prevalence of low LGE amounts in HCM patients in the clinical routine,10,22Figure 4B. Our results are in line with Chan et al.8 who reported that the SCD risk in patients with small amounts of LGE (≤5%) did not differ significantly from the SCD risk in patients without LGE. Therefore, the LGE 5% threshold may be of clinical value in both mid-term8 and long-term prognosis of HCM patients.

In contrast to Chan et al.,8 who reported a 15% LGE threshold indicating a two-fold increased SCD risk, Kaplan–Meier curves for different LGE amounts beyond the 5% LGE threshold were comparable in our present study, Figure 5. After initial divergence of the Kaplan–Meier curves in the first 5 years, the curves parallel within the following years. Therefore, one reason for the definition of the critical 5% LGE threshold reported in our cohort might be the extended follow-up time to 15 years. Another reason for differing critical LGE-thresholds may be the higher amount of LGE in the study from Chan et al.8 (9% vs. 1.6% in our cohort). Of note, another study with a lower overall LGE amount than Chan et al.8 and a similar clinical baseline characteristic as our cohort (LGE amount 2%, median age 54 years, LGE prevalence 65%, low ESC HCM risk score) supports our hypothesis that a lower threshold than the 15% LGE amount might be useful to recognize additional patients at increased risk for malignant arrhythmic episodes. Specifically, an LGE extent ≥10% was the best threshold to predict major arrhythmic events (area under the curve 0.74).22 Unfortunately, median follow-up time in the latter study was only 3.3 years. One might argue that with a longer follow-up time, the critical LGE-threshold might decrease further, converging the 5% LGE-threshold as reported in this study.

Value of the ESC SCD risk score in long-term follow-up

First, the ESC SCD risk score classified this cohort as a low-risk SCD population and the calculated 5-year SCD risk (1.8%) parallels the observed 5-year SCD incidence (2.3%) indeed, Figure 2 (dashed line at 5 years). Therefore, despite some contrary data which suggest that the ESC risk score leads to less ICD implants but might misclassify high-risk patients,3 the ESC SCD risk score was an adequate tool for assessing the overall 5-year SCD risk of our study cohort. However, it was not sensitive enough to discriminate those patients being at increased risk for SCD from the others.

These predominantly young to middle-aged HCM patients deserve a refined assessment of their long-term risk, which seems to be not adequately reflected by established HCM SCD risk models, and might be enhanced by the addition of other non-invasive parameters such as LGE-CMR. We reported a substantial increase of SCD risk after 10 and 15 years in our ‘low-risk’ HCM cohort: SCD risk increased from 4.8% at 10 years to 15.7% at 15 years, which is even enhanced in patients with >5% LGE (33.3% at 15 years), underlining the unmet need for additional risk stratification in SCD long-term risk assessment. Therefore, we suggest further research incorporating both presence and exact amount of LGE beside established risk factors in future HCM SCD risk models to validate our findings.

Limitations

Newer CMR mapping techniques (T1 and T2 mapping) were not performed since they were not available at the time of patient enrolment. However, mapping values depend on the sequence and vendor, and LGE-CMR is more established for prognosis in HCM.

Genetic panels were not routinely performed. Therefore, HCM phenotype might mimic in rare cases other forms of cardiomyopathies. However, by the use of LGE in our cohort, specific LGE patterns indicating potential differential diagnosis such as M. Fabry or cardiac amyloidosis would have been noted.

Another limitation might be that patients in whom ICDs were implanted before CMR were not included. Furthermore, the amount of LGE may progress during follow-up, with potential implications on risk assessment and the occurrence of events. Since our HCM population was a low-risk population, our results might not be generalized to high-risk patients with HCM. However, patients otherwise misclassified as low-risk group according to established risk factors and scores might benefit most from the addition of LGE-CMR parameters.

Patients were not divided in obstructed and non-obstructed HCM. Furthermore, our population included also patients who underwent myectomy or transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy during follow-up. However, it has previously been demonstrated that the amount of LGE provides prognostic utility in all of these subgroups.9

Conclusions

LGE-CMR in HCM patients allows effective SCD risk stratification for long-term prognosis beyond established risk models. Our data suggest that LGE-CMR should be added to established risk models for decision-making of primary prevention ICD to improve its discriminatory power. Specifically, patients with no or ≤5% LGE amount seem to have favourable prognosis. Conversely, patients with >5% amount of LGE are at increased risk suffering from SCD at 10 and 15 years, irrespective of established risk models. Therefore, patients with >5% amount of LGE should be carefully monitored and further prospective studies should investigate if these patients might be adequate candidates for primary prevention ICD during the clinical course.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging online.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the Robert Bosch Foundation: KKF 13-2, KKF 15-5, and KKF 770. This project was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Klinische Forschungsgruppe-KFO-274: ‘Platelets-Molecular Mechanisms and Translational Implications’) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Projektnummer 374031971—TRR 240.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB. et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2018;138:e210–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F . et al. ; Authors/Task Force members. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2733–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maron BJ, Casey SA, Chan RH, Garberich RF, Rowin EJ, Maron MS.. Independent assessment of the European Society of Cardiology sudden death risk model for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Desai MY, Smedira NG, Dhillon A, Masri A, Wazni O, Kanj M. et al. Prediction of sudden death risk in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: potential for refinement of current criteria. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;156:750–9.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruder O, Wagner A, Jensen CJ, Schneider S, Ong P, Kispert EM. et al. Myocardial scar visualized by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predicts major adverse events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:875–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weng Z, Yao J, Chan RH, He J, Yang X, Zhou Y. et al. Prognostic value of LGE-CMR in HCM: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:1392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greulich S, Arai AE, Sechtem U, Mahrholdt H.. Recent advances in cardiac magnetic resonance. F1000Res 2016;5:2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Pencina MJ, Assenza GE, Haas T. et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2014;130:484–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mentias A, Raeisi-Giglou P, Smedira NG, Feng K, Sato K, Wazni O. et al. Late gadolinium enhancement in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and preserved systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:857–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neubauer S, Kolm P, Ho CY, Kwong RY, Desai MY, Dolman SF. et al. Distinct subgroups in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the NHLBI HCM Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2333–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maron BJ, McKenna WJ, Danielson GK, Kappenberger LJ, Kuhn HJ, Seidman CE. et al. American College of Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1965–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kramer CM, Barkhausen J, Flamm SD, Kim RJ, Nagel E; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Board of Trustees Task Force on Standardized Protocols. Standardized cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) protocols 2013 update. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013;15:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Simonetti OP, Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Hillenbrand HB, Wu E, Bundy JM. et al. An improved MR imaging technique for the visualization of myocardial infarction. Radiology 2001;218:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Holly TA, Elliott MD, Bonow RO, Kim RJ. et al. Reproducibility of chronic infarct size measurement by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2002;106:2322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Choudhury L, Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Choi KM, Elliott MD, Klocke FJ. et al. Myocardial scarring in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:2156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schulz-Menger J, Bluemke DA, Bremerich J, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG. et al. Standardized image interpretation and post processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance: society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) board of trustees task force on standardized post processing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013;15:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Rodriguez ER, Tan C, Setser R, Thamilarasan M. et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance detection of myocardial scarring in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: correlation with histopathology and prevalence of ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moon JC, Reed E, Sheppard MN, Elkington AG, Ho SY, Burke M. et al. The histologic basis of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2260–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O'Mahony C, Jichi F, Pavlou M, Monserrat L, Anastasakis A, Rapezzi C. et al. ; for the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Outcomes Investigators. A novel clinical risk prediction model for sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM risk-SCD). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2010–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greulich S, Schumm J, Grun S, Bruder O, Sechtem U, Mahrholdt H.. Incremental value of late gadolinium enhancement for management of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maron BJ, Maron MS.. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2013;381:242–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Todiere G, Nugara C, Gentile G, Negri F, Bianco F, Falletta C. et al. Prognostic role of late gadolinium enhancement in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and low-to-intermediate sudden cardiac death risk score. Am J Cardiol 2019;124:1286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interest: none declared.