Abstract

Background:

Of the most important implications and complaints in the elderly group of the population, is oral and dental health problems. This study aimed to assess oral health- related quality of life in older people.

Methods:

To data collection, databases were searched including PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, SID, MagIran, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and scholar google The keywords were “older adults”, “Geriatric” Elderly”, “Older”, “Aged”, “Ageing”, “Oral health”, “Oral hygiene” and “Quality of life”, “QOL. For manual searching, several specialized journals of related scope as well as the finalized articles’ reference list were searched. Studies from 1st Jan 2000 to 30th Jan 2017 were included. Studies were subjected to meta-analysis to calculate indexes, using CMA:2 (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis) software.

Results:

Totally, 3707 articles were searched that 48 of them were subjected to the oral and dental health-related quality of life in 59 groups of the elderly population with the mean age of 73.57+6.62 in the 26 countries. The obtained percentage values of dental and oral health were 80.2% (0–60), 14.8% (0–12), 16.4% (0–70), 22% (0–14 or 0–59) and 19.2% (0–196) for GOHAI with the additive method, GOHAI with Simple Count Method, OHIP-14 with the additive method, OHIP-14 with Simple Count method and OHIP-49 with additive method indexes, respectively.

Conclusion:

The elderly group of the population had no proper oral health-related quality of life. Regarding the importance and necessity of oral and dental health and its effect on general health care in the target group, it is recommended to improve dental hygiene in the mentioned group of population.

Keywords: Older adults, Geriatric, Elderly, Older, Aged, Ageing, Oral health, Oral hygiene, Quality of life

Introduction

Regarding the reported statistics particularly in middles and low-income countries, the population aging will become a fundamental concern during the future years (1, 2). Currently, the population aged 60+ are comprising more than 600 million of the world population. In 2020 this value will reach over 1 billion and in 2050 to 2 billion (3, 4).

The old aging people are more vulnerable to many complications in particular chronic diseases (5, 6). The oral and dental disorders are one of the most prevalent implications and complaints in this group of the population (7–9). Overall, the general health in the human body gives rise to the appropriate oral and dental health (10, 11). Tooth decay and periodontal complications are considered as the most well-known diseases (12–14). The instability of daily patterns and changing lifestyles have caused these diseases to increase. Over 90% of the human population is suffering from these complications and more than 50 h are wasted due to the complexities of these diseases (15). Changes in the dental health status of elderly individuals affect the nutritional requirements, food intake patterns, and ultimately physical conditions. On the other hand, it can influence one individual’s appearance, self-esteem, and psychological-social functions and the quality of life in elderly people (16–21). Therefore, the quality of life in this age group is of paramount importance (22–24).

The quality of life is a multidimensional, mental and complex concept that harbors all aspects of life, in other words, a unique individual understanding, and a way of expressing a person’s feelings about health or other aspects of life, reviewed through an expression of people’s beliefs and using standard tools (25–31).

In recent years, many investigations have been conducted on the quality of life associated with dental and oral health (32–35). However, these studies have examined the quality of elderly living in a confined area including smaller sample size. Based on these documents, they have no adequate information to make a clear decision and an ordainment of policies. The systematic conclusion of the results can provide the necessary information for solving these deficiencies on a broad scale. Hence, the aim of this study is a systematic review of the quality of life associated with oral and dental health and involved factors in elderly individuals.

Methods

The current systematic and meta-analysis review was conducted in 2017 following the book entitled “A Systematic Review to support evidence-Based Medline” (36).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- All studies including (Descriptive-analytical, cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort had been subjected.

Exclusion criteria:

- Interventional studies, under 60 years-investigated articles, less than 10 sample size researches, and presented articles in the congresses were excluded.

Information sources

Searching the required information sources was done through the google scholar, PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, SID, MagIran and Cochrane central register of controlled trials databases with the keywords “older adults”, “Geriatric” Elderly”, “Older”, “Aged”, “Ageing”, “Oral health”, “Oral hygiene” and “Quality of life”, QOL from 1st Jan 2000 to 30th Jan 2017. For manual searching, several specialized journals of related scope as well as the finalized articles. There was also contact with dentistry experts. To collect non-published sources (Grey Literature) European Association for Grey Literature Exploitation (EAGLE) and Health care Management Information Consortium (HMIC) were searched (Table 1).

Table 1:

Complete search strategy for PubMed databases

| Search | Recent queries in PubMed | Item found |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | (“quality of life”) OR “QOL”[Title/Abstract] | 258248 |

| #2 | (“oral health”[Title/Abstract]) OR “oral hygiene”[Title/Abstract] | 34411 |

| #3 | ((((“elderly”[Title/Abstract]) OR “ageing”[Title/Abstract]) OR “older”[Title/Abstract]) OR “older adults”[Title/Abstract]) OR “aged” [Title/Abstract] | 1052735 |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 682* |

Filters activated: Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2017/04/31, Humans, English.

Review Process

Firstly, the titles of reviewed articles that were not consistent with the study objectives were excluded. In the next step, the abstract and full texts were reviewed and identified articles that did not comprise the inclusion criteria and poorly integrated with the research were retracted. The data extraction form was designed manually in word software. Thereafter, the 5 articles’ data were extracted empirically, and defeats in the initial form were resolved.

The included items were authors, year of study, country, sample size, statistical population, the mean age of participants, the average of life quality, instrument type, collection of data, and score calculations. All process was carried out by two authors and dispute cases were referred to the third person.

Reporting Quality Assessment

Reporting quality of included articles was evaluated by two assessors through strengthening the Reporting of observational studies Epidemiology (STROBE) (37) checklist. Disagreements between them were referred to as the third person. This checklist was selected because of its specificity for the evaluation of observational studies and its validity and translation to the Persian for assessing articles in the study (38). It was included 22 items (39, 40).

Data Analysis

Studies were subjected to meta-analysis to calculate indexes, using CMA:2 (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis) software. To report results, it was applied to the Forest plot diagrams in where the size of each square indicates the sample size and drawn lines of each side represent the confidence interval about 95% for each study. For results, heterogeneity assaying Q statistics and I2 index were used. In this study, over 50% of I2 would be the heterogeneity scale of articles.

GOHAI

General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) as a 12 items-questionnaire evaluates the life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene. It assays the three dimensions: functional, psychological, and discomfort. To compute GOHAI scores two methods include the additive (ADD) and simple count (SC) were used. Additive scores for GOHAI had obtained through the adding answer scores for 12 items after encoding reversed. To score the items Likert scale was applied in which it has considered always=5, often=3, sometimes=2, rarely=1, and never=0. Consequently, the GOHAI scale is calculated from 0–60. The higher scores indicate the improved life quality associated with oral and dental health. To score with GOHAI for simple count method by counting the case numbers it has used the answers such as sometimes, rather often, rarely or never. The scores are variable from 0–12 for GOHAI (33, 41, 42).

OHIP-14

To calculate OHIP-14 scores, two methods include the additive (ADD) and simple count (SC) were applied. Additive scores for OHIP-14 had obtained through the adding 14 items scores. For scoring the items Likert scale had been used as well. In this instrument always=5, often=4, quietly=3, sometimes=2, rarely=1, and never=0. Consequently, the OHIP-14 scale from 0–70 including higher scores is indicating the quality of life associated with oral and dental health. To score with simple count method in OHIP-14 by counting the case numbers it has used the answers such as sometimes, rather often, rarely or never. In this method, score ranges have been evaluated from 0–14 or between 0–56 (42, 43).

OHIP-49

The OHIP-49 questionnaire includes 7 dimensions such as functional constraints, physical pain, psychological discomfort, and social, physical and psychological disabilities, and 49 items to assay. For item scoring Likert scale had been applied (0=never, quietly always=1, sometimes=2, rather often =3, and many=4). In OHIP-49 the 0 score indicates the high level of life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene and the high score represents an implication in this area. The scores were obtained by only adding the answers points (44, 45). To calculate the average of life quality associated with oral and dental health in older people, regarding the various instruments obtained scores from studies were adjusted. To unify how to the calculation of score ranges it was considered from 0–100 and the mean scores of life quality in older individuals were computed from 0–100.

Results

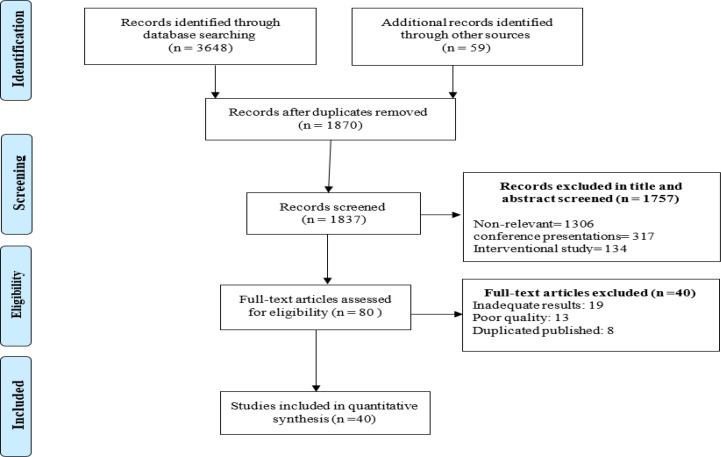

Overall, 3707 articles were searched that 1837 of them were removed because of common sources and 1817 cases in the title and abstract assessment. In full-text evaluation, 13 cases were retracted as well. Finally, 40 articles were included (Fig. 1) (Appendix 1: Not published but is ready in case of requesting by readers) (46–80), in which information about the life quality of 55 groups of older individuals in 24 countries was reported. Nineteen groups were evaluated in community, 3 groups in nursing homes, and 33 groups in health care centers. Overall, the life quality of 22416 older participants had been assessed with the mean age of 73.57± 6.62.

Fig. 1:

Searches and inclusion process

The study results are based on the used tools for assaying the life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene in older individuals in 5 sections.

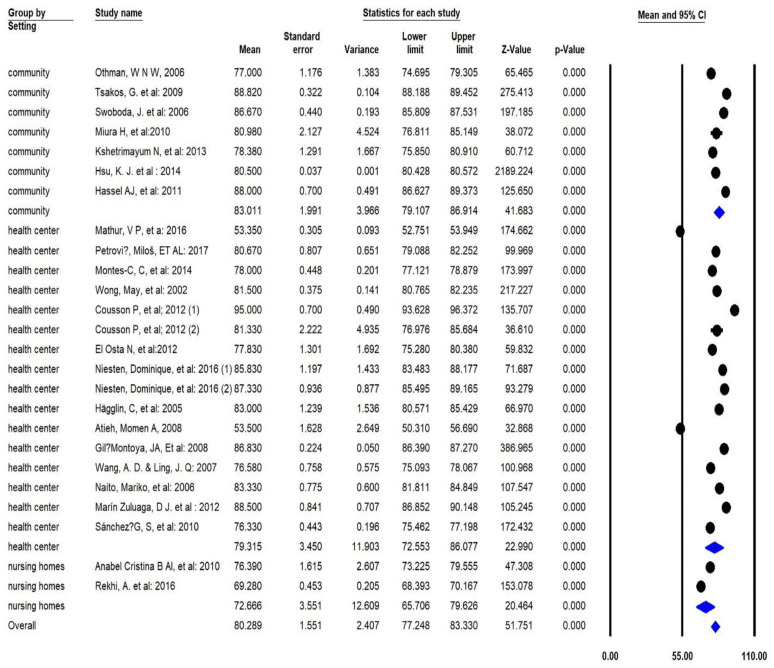

GOHAI with the Additive Method

Total average of life quality in the elderly group is 80.2 [77.2–83.3 95%CI Q=11341.1 df=24 I2=97.7 P<0.001], in health care centers 79.3 [72.5–86 95%CI Q=9367 df=15 I2=98.5 P<0.001], in the home/society 83 [79.1–86.9 95%CI Q=968.7 df=6 I2=98.7 P<0.001], and in nursing homes 72.6 [65.7–79.6 95%CI Q=17.9 df=1 I2=91.3 P<0.001] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2:

Quality of Life associated with oral and dental hygiene using General (formerly Geriatric) Oral Health Assessment Index with the additive methods.

GOHAI with Simple Count Method

The total average of life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene in the elderly group is 14.8 [9.6–20 95%CI Q=306.6 df=4 I2=94.6 P<0.001] (43).

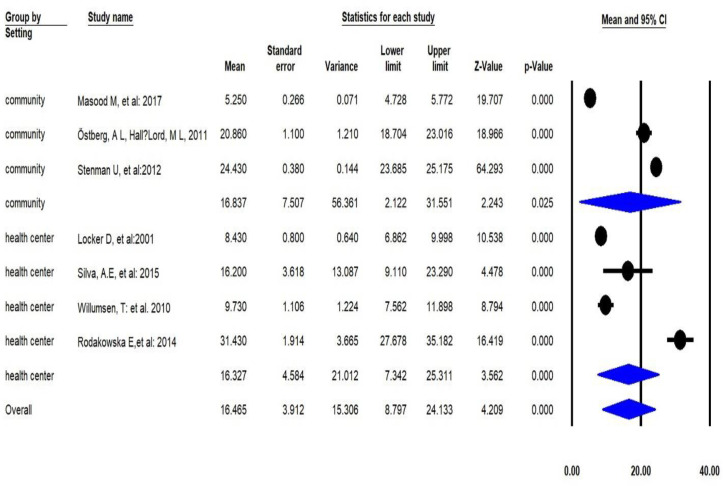

OHIP-14 with the Additive Method

The total average of life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene in the elderly group is 16.2 [8.7–24.1 95%CI Q=1904.9 df=6 I2=96.8 P<0.001], total average of life quality in health care centers 16.3 [7.3–25.3 95%CI Q=127.3 df=3 I2=94.5 P<0.001], in-home/society 16.8 [2.1–31.5 95%CI Q=177.7 df=2 I2=97.7 P<0.001] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3:

Quality of life associated with oral and dental hygiene using Oral Health Impact Profile-14 with the additive method

OHIP-14 with Simple Count Method

The total average of life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene in the elderly group is 22.2 [16–28.4 95%CI Q=527.2 df=6 I2=94.8 P<0.001].

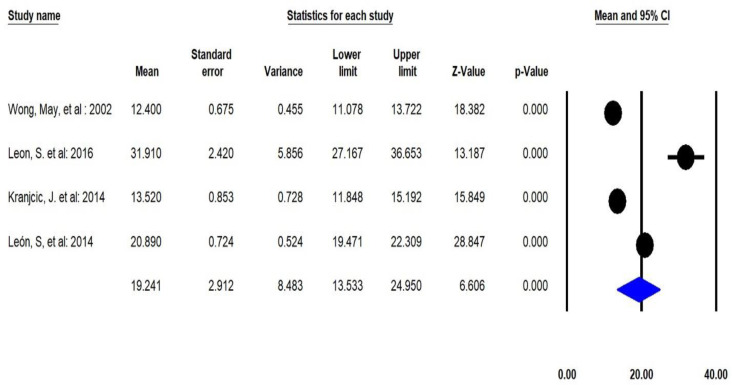

OHIP-49 with the Additive Method

Results indicated that the total average of life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene in the elderly group is 19.2 [13.5–24.9 95%CI Q=125.6 df=3 I2=92.8 P<0.001] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4:

Quality of Life associated with oral and dental hygiene using OHIP-49 with the additive method

Discussion

In the present study, 3707 articles were searched and 48 cases of them were included. The evaluation of life quality of 22416 participants was reported through the 5 instruments in health care centers, homes, and society. In GOHAI with additive method-investigations that surveyed the life quality associated with oral and dental health, the total average in elderly individuals was 80.2% followed by 14.8% in GOHAI with simple count method, 16.4% in OHIP-14 with the additive method, 22.2% in OHIP-14 with simple count method, and 19.2% with OHIP-49 with the additive method.

The results pertinent to OHIP-14 with a simple count method were following Baker et al. results (2006) with 22.47% in England (81). The majority of findings in Canada (82) and the United States (83–85) indicated the low quality of life associated with oral and dental hygiene in older people. The mouth cancer, tooth decaying, incidence of periodontal infections, and loss of teeth gives rise to improper hygiene (86, 87). Regarding the importance of oral and dental hygiene promoting the WHO recommends taking some measures in countries (88, 89). Of the most significant general preventative measures, daily and primary care of teeth such as brushing and plaque control in elderly patients, no alcohol abuse, assessment of health care, and a 6-month checkup are in utmost importance (90–92).

General health and life quality of elderly people are extensively affected by the oral and dental hygiene (93–96). The probability of oral and dental implications in this age group is deeply regarded (97). The elderly individuals were believed that their improper general health gives rise to the low dental and oral hygiene (98). Despite the mentioned points and other complications, elderly people dedicate lower priority to their oral and dental hygiene which influences the life quality and general health matter (55). It is also probable low expectations of oral and dental health in the low and middle income-countries which increase the reports rate of complexities related to life quality, therefore, it is important to be more cautious about dental implications (97). One of the elderly peoples’ misconceptions is no necessity to have the tooth, so they have no pay attention to oral hygiene. It influences their life quality. On the other hand, health officials concentrate their potencies on the children, young people, and adolescents and most of the health priorities have been implemented on them. These false conceptions are declining factors for elderly individuals’ health and their life quality.

Life quality percentage in nursing homes was 72.6%, and in health care centers with a marginally increase in a value of 79.3%, in the homes/society it had the highest rate in comparison with other groups in a value of 83%. In nursing homes due to the low awareness about health, dentistry visiting has taken only in emergency cases. Moreover, the high mental problems and melancholia cause to pay no proper attention to efficient hygiene. However, elderly people in homes and society have a better condition because their relatives take preventative and treatment measures. Other reasons for low-total scores of life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene are considered as the lack of motivation and no strong social relationship in the nursing homes. The individuals in the unfamiliar and no social relationship condition have a lower score of life quality associated with oral and dental health compared to other groups (32).

Additionally, the inability to access health services in nursing homes particularly in low and middle-income countries as well as non-referral to dentists is of most major factors to have a direct negative impact on the quality of life associated with oral and dental hygiene (84, 99). Educating elderly individuals in nursing homes about oral and dental health and increase their awareness is a positive and constructive action to reduce detrimental consequences (99, 100). Moreover, the establishment of a suitable background and easy access to health services promote the life quality in this age group of population.

The life quality associated with oral and dental hygiene in health care centers was 79.3%, marginally lower than 83% pertinent to the home/society elderly individuals. The low hygiene level of patients in health care centers to receive services is considered as the main cause of this statement besides the oral ulcers and abscess (51). Some reasons like the relationship with family members have a direct impact on the higher quality of life in the home/society elderly individuals. However, the mentioned percentage is not completely acceptable and has the potency to be higher. One of the strategies that are defined to reduce the effects of oral and dental infections consequences is preventative measures in extended periods including daily oral and dental hygiene and its continuous assessment (88, 90–92).

The findings of the current study state that, there is no identical tool for assessing the quality of life associated with oral and dental health in elderly individuals and each instrument calculates the scores with a different distribution. To improve the evaluation method, it is necessary to design an identical instrument with the unit instructions. For localizing the short and long forms of instruments, it is suggested to follow the unit instructions for each country. Moreover, the authors are not permitted to modify its content with different perspectives.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study were the existence of a variety of instruments with different methods of calculation. It persuaded the authors to divide the articles into several categories which led to a high dispersion rate and low power of findings. Moreover, some of the articles written to other languages were excluded from the study because of unfamiliarity to authors.

Conclusion

Oral health related to life quality in older people has not appropriate level. Therefore, as a result of poor oral and dental hygiene levels in this age group besides the other complications, it is crucial to increase the attention to dental care and the explicit support of countries’ health systems in all aspects of health. Given the importance of dental hygiene, it is necessary to provide health services related to dentistry according to the health policies of countries in service packages.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Research Center for Evidence Based Medicine (RCEBM), Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Research NO: 61524).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lutz W, Sanderson W, Scherbov S. (2008). The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature. 451(7179):716–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinsella KG, Phillips DR. (2005). Global aging: The challenge of success. Population Bulletin, 60(1): 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beard HPJR, Bloom DE. (2015). Towards a comprehensive public health response to population ageing. Lancet, 385(9968):658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzman R, Beard JR, Boerma T, et al. (2015). Health in an ageing world—what do we know? Lancet, 385(9967):484–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reider N, Gaul C. (2016). Fall risk screening in the elderly: A comparison of the minimal chair height standing ability test and 5-repetition sit-to-stand test. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 65:133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabeshova A, Launay CP, Gromov VA, et al. (2016). Falling in the elderly: Do statistical models matter for performance criteria of fall prediction? Results from two large population-based studies. Eur J Intern Med, 27:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swoboda J, Kiyak HA, Persson RE, et al. (2006). Predictors of oral health quality of life in older adults. Spec Care Dentist, 26(4):137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Mata C, Cronin M, O’Mahony D. (2015). Subjective impact of minimally invasive dentistry in the oral health of older patients. Clin Oral Investig, 19(3):681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karki A, Monaghan N, Morgan M. (2015). Oral health status of older people living in care homes in Wales. Br Dent J, 219(7):331–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baghaie H, Kisely S, Forbes M, et al. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and substance abuse. Addiction, 112(5):765–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacruz RS, Habelitz S, Wright JT, et al. (2017). Dental enamel formation and implications for oral health and disease. Physiol Rev, 97(3):939–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nazar H, Al-Mutawa S, Ariga J, et al. (2014). Caries prevalence, oral hygiene, and oral health habits of Kuwaiti infants and toddlers. Med Princ Pract, 23(2):125–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marino R, Albala C, Sanchez H, et al. (2015). Prevalence of diseases and conditions which impact on oral health and oral health self-care among older chilean. J Aging Health, 27(1):3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi N, Soga Y, Maekawa K, et al. (2017). Prevalence of oral health-related conditions that could trigger accidents for patients with moderate-to-severe dementia. Gerodontology, 34(1):129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwan SY, Petersen PE, Pine CM, et al. (2005). Health-promoting schools: an opportunity for oral health promotion. Bull World Health Organ, 83(9):677–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozdemir E, Yilmaz H, Orhan H. (2016). General health and oral health status in elderly dental patients in Isparta, Turkey. East Mediterr Health J, 22(8):579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freitas YN, Lima KC, Silva DAd. (2016). Oral health status and functional capacity in the elderly: a longitudinal population-based study. Rev Bras Epidemiol, 19(3):670–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph AG, Janakiram C, Mathew A. (2016). Prosthetic Status, Needs and Oral Health Related Quality of Life (OHRQOL) in the Elderly Population of Aluva, India. J Clin Diagn Res, 10(11):ZC05–ZC09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa MJF, Lins CAdA, Macedo LPVd, et al. (2019). Clinical and self-perceived oral health assessment of elderly residents in urban, rural, and institutionalized communities. Clinics (Sao Paulo), 74: e972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paredes-Rodríguez V-M, Torrijos-Gómez G, González-Serrano J, et al. (2016). Quality of life and oral health in elderly. J Clin Exp Dent, 8(5): e590–e596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jafari-Shobeiri M, Ghojazadeh M, Azami-Aghdash S, et al. (2015). Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Public Health, 44(8):1036–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camelo LdV, Giatti L, Barreto SM. (2016). Health related quality of life among elderly living in region of high vulnerability for health in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol, 19(2):280–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaier K, Gutmann A, Baumbach H, et al. (2016). Quality of life among elderly patients undergoing transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement–a model-based longitudinal data analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 14:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleczyński P, Bagieński M, Dziewierz A, et al. (2016). Twelve-month quality of life improvement and all-cause mortality in elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Int J Artif Organs, 39(8):444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan RM, Ries AL. (2007). Quality of life: concept and definition. COPD, 4(3):263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandau KE, Hoglund BA, Weaver CE, et al. (2014). A conceptual definition of quality of life with a left ventricular assist device: results from a qualitative study. Heart Lung, 43(1):32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xavier FM, Ferraz M, Marc N, et al. (2003). Elderly people s definition of quality of life. Braz J Psychiatry, 25(1):31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaghoubi A, Tabrizi J-S, Mirinazhad M-M, et al. (2012). Quality of life in cardiovascular patients in iran and factors affecting it: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res, 4(4):95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maleki MR, Derakhshani N, Azami-Aghdash S, et al. (2020). Quality of Life of People with HIV/AIDS in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iran J Public Health, 49(8):1399–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azami-Aghdash S, Gharaee H, Aghaei MH, et al. (2019). Cardiovascular diseases patient’s Quality of Life in Tabriz-Iran: 2018. Journal of Community Health Research,8(4):245–252. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azami-Aghdash S, Ghojazadeh M, Naghavi-Behzad M, et al. (2019). A pilot study of fear of disease consequences and its relationship with quality of life, depression and anxiety in patients with multiple sclerosis. International Archives of Health Sciences, 6(3):132–135. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcarde ACB, Bittar TO, Fornazari DH, et al. (2010). A cross-sectional study of oral health-related quality of life of Piracicaba’s elderly population. Rev odonto ciênc, 25(2):126–31. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atchison KA, Dolan TA. (1990). Development of the geriatric oral health assessment index. J Dent Educ, 54(11):680–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cousson PY, Bessadet M, Nicolas E, et al. (2012). Nutritional status, dietary intake and oral quality of life in elderly complete denture wearers. Gerodontology, 29(2):e685–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kshetrimayum N, Reddy CV, Siddhana S, et al. (2013). Oral health-related quality of life and nutritional status of institutionalized elderly population aged 60 years and above in Mysore City, India. Gerodontology, 30(2):119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan K, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, et al. (2011). Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine. 2nd ed, Crc Press. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. (2014). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg, 12(12):1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poorolajal J, Tajik P, Yazdizadeh B, et al. (2009). Quality assessment of the reporting of cohort studies before STROBE statement. Iranian journal of epidemiology, 5(1):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med, 147(8):573–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vandenbroucke JP, Von E, lm E, Altman DG, et al. (2007). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med, 4(10):e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiyak HA. (2008). Does orthodontic treatment affect patients’ quality of life? J Dent Educ, 72(8):886–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen PF, Locker D. (1997). Do item weights matter? An assessment using the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Health, 14(3):133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Locker D, Matear D, Stephens M, et al. (2001). Comparison of the GOHAI and OHIP-14 as measures of the oral health-related quality of life of the elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 29(5):373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petričević N, Čelebić A, Papić M, et al. (2009). The Croatian version of the oral health impact profile questionnaire. Coll antropol, 33(3):841–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kranjčić J, Mikuš A, Peršić S, et al. (2014). Factors affecting oral health–related quality of life among elderly Croatian patients. Acta Stomatol Croat, 48(3):174–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Locker D, Matear D, Stephens M, et al. (2001). Comparison of the GOHAI and OHIP-14 as measures of the oral health-related quality of life of the elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 29(5):373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Motallebnejad M, Mehdizadeh S, Najafi N, et al. (2015). The evaluation of oral health-related factors on the quality of life of the elderly in Babol. Contemp Clin Dent, 6(3):313–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodakowska E, Mierzyńska K, Bagińska J, et al. (2014). Quality of life measured by OHIP-14 and GOHAI in elderly people from Bialystok, north-east Poland. BMC Oral Health, 14:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El Osta N, Tubert-Jeannin S, Hennequin M, et al. (2012). Comparison of the OHIP-14 and GOHAI as measures of oral health among elderly in Lebanon. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 10: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikebe K, Hazeyama T, Enoki K, et al. (2012). Comparison of GOHAI and OHIP-14 measures in relation to objective values of oral function in elderly J apanese. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 40(5):406–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masood M, Newton T, Bakri NN, et al. (2017). The relationship between oral health and oral health related quality of life among elderly people in United Kingdom. J Dent, 56:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miura H, Yamasaki K, Morizaki N, et al. (2010). Factors influencing oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among the frail elderly residing in the community with their family. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 51(3):e62–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rekhi A, Marya CM, Oberoi SS, et al. (2016). Periodontal status and oral health-related quality of life in elderly residents of aged care homes in Delhi. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 16(4):474–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silva AE, Demarco FF, Feldens CA. (2015). Oral health-related quality of life and associated factors in Southern Brazilian elderly. Gerodontology, 32(1):35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Östberg AL, Hall-Lord ML. (2011). Oral health-related quality of life in older Swedish people with pain problems. Scand J Caring Sci, 25(3):510–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsakos G, Sheiham A, Iliffe S, et al. (2009). The impact of educational level on oral health-related quality of life in older people in London. Eur J Oral Sci, 117(3):286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hassel AJ, Steuker B, Rolko C, et al. (2010). Oral health-related quality of life of elderly Germans--comparison of GOHAI and OHIP-14. Community Dent Health, 27(4):242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willumsen T, Fjaera B, Eide H. (2010). Oral health-related quality of life in patients receiving home-care nursing: associations with aspects of dental status and xerostomia. Gerodontology, 27(4):251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuluaga DJM, Montoya JAG, Contreras CI, et al. (2012). Association between oral health, cognitive impairment and oral health–related quality of life. Gerodontology, 29(2):e667–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gil-Montoya J, Subirá C, Ramón J. (2008). Oral health-related quality of life and nutritional status. J Public Health Dent, 68(2):88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biazevic MG, Michel-Crosato E, Iagher F, et al. (2004).Impact of oral health on quality of life among the elderly population of Joacaba, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Braz Oral Res, 18(1):85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Enoki K, Matsuda KI, Ikebe K, et al. (2014).Influence of xerostomia on oral health-related quality of life in the elderly: a 5-year longitudinal study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 117(6):716–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsu KJ, Lee HE, Wu YM, et al. (2014).Masticatory factors as predictors of oral health-related quality of life among elderly people in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan. Qual Life Res, 23(4):1395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang A, Ling J. (2007).A survey of oral health-related quality of life and related influencing factors in elderly patients. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi, 42(8):489–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ikebe K, Hazeyama T, Morii K, et al. (2007).Impact of masticatory performance on oral health-related quality of life for elderly Japanese. Int J Prosthodont, 20(5):478–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leon S, Bravo-Cavicchioli D, Giacaman RA, et al. (2016).Validation of the Spanish version of the oral health impact profile to assess an association between quality of life and oral health of elderly Chileans. Gerodontology, 33(1):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stenman U, Ahlqwist M, Björkelund C, et al. (2012). Oral health–related quality of life–associations with oral health and conditions in Swedish 70-year-old individuals. Gerodontology, 29(2):e440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zini A, Sgan-Cohen HD. (2008).The effect of oral health on quality of life in an underprivileged homebound and non-homebound elderly population in Jerusalem. J Am Geriatr Soc, 56(1):99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Atieh MA. (2008). Arabic version of the geriatric oral health assessment index. Gerodontology, 25(1):34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hägglin C, Berggren U, Lundgren J. (2005).A Swedish version of the GOHAI index. Psychometric properties and validation. Swed Dent J, 29(3):113–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mathur VP, Jain V, Pillai RS, et al. (2016).Translation and validation of H indi version of G eriatric O ral H ealth A ssessment I ndex. Gerodontology, 33(1):89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Niesten D, Witter D, Bronkhorst E, et al. (2016). Validation of a Dutch version of the Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI-NL) in care-dependent and care-independent older people. BMC geriatrics, 16(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Petrović M, Stančić I, Popovac A, et al. (2017).Oral health-related quality of life of institutionalized elderly in Serbia. Vojnosanit pregl, 74(5):402–409. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Naito M, Suzukamo Y, Nakayama T, et al. (2006).Linguistic adaptation and validation of the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) in an elderly Japanese population. J Public Health Dent, 66(4):273–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Othman WNW, Muttalib KA, Bakri R, et al. (2006).Validation of the geriatric oral health assessment index (GOHAI) in the Malay language. J Public Health Dent, 66(3):199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sánchez-García S, Heredia-Ponce E, Juárez-Cedillo T, et al. (2010).Psychometric properties of the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) and dental status of an elderly Mexican population. J Public Health Dent, 70(4):300–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Montes-Cruz C, Juárez-Cedillo T, Cárdenas-Bahena Á, et al. (2014).Behavior of the Geriatric/General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) and Oral Impacts on Daily Performances (OIDP) in a senior adult population in Mexico City. Revista odontológica mexicana, 18(2):111–119. [Google Scholar]

- 78.León S, Bravo-Cavicchioli D, Correa-Beltrán G, et al. (2014). Validation of the Spanish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14Sp) in elderly Chileans. BMC Oral Health, 14:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wong MC, Lo EC, McMillan AS. (2002).Validation of a Chinese version of the oral health impact profile (OHIP). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 30(6):423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong MC, Liu JK, Lo EC. (2002).Translation and validation of the Chinese version of GOHAI. J Public Health Dent, 62(2):78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baker SR, Pankhurst CL, Robinson PG. (2006).Utility of two oral health-related quality-of-life measures in patients with xerostomia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 34(5):351–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.MacEntee MI, Weiss R, Waxier-Morrison NE, et al. (1987).Factors influencing oral health in long term care facilities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 15(6):314–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kambhu PP, Levy SM. (1993).Oral hygiene care levels in Iowa intermediate care facilities. Spec Care Dentist, 13(5):209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kiyak HA, Grayston MN, Crinean CL. (1993).Oral health problems and needs of nursing home residents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 21(1):49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gift HC, Cherry-Peppers G, Oldakowski RJ. (1997).Oral health status and related behaviours of US nursing home residents, 1995. Gerodontology, 14(2):89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cohen LK. Disease prevention and oral health promotion: socio-dental sciences in action. Munksgaard; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Joshipura KJ, Hung H-C, Rimm EB, et al. (2003).Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and incidence of ischemic stroke. Stroke, 34(1):47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petersen PE, Yamamoto T. (2005).Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 33(2):81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.World Health Organization (2002). Active ageing: A policy framework. Geneva: WHO, pp.:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Niessen LC, Douglass CW. (1992).Preventive actions for enhancing oral health. Clin Geriatr Med, 8(1):201–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ettinger RL. (1992).Oral care for the homebound and institutionalized. Clin Geriatr Med, 8(3):659–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Steele J, Walls A. (1997).Strategies to improve the quality of oral health care for frail and dependent older people. Qual Health Care, 6(3):165–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Inglehart MR, Bagramian R. (2002). Oral health-related quality of life: Quintessence Publishing Co. Chicago, pp. 1–6 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. (1994).Development and evaluation of the oral health impact profile. Community Dent Health, 11(1):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Petersen PE, Nörtov B. (1989).General and dental health in relation to life-style and social network activity among 67-year-old Danes. Scand J Prim Health Care, 7(4):225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Locker D. (1988).Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health, 5(1):3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kotzer RD, Lawrence HP, Clovis JB, et al. (2012). Oral health-related quality of life in an aging Canadian population. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 10:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Srisilapanan P, Sheiham A. (2001).The prevalence of dental impacts on daily performances in older people in Northern Thailand. Gerodontology, 18(2):102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Frenkel H, Harvey I, Newcombe RG. (2000).Oral health care among nursing home residents in Avon. Gerodontology, 17(1):33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nicol R, Petrina S, weeney M, McHugh S, et al. (2005).Effectiveness of health care worker training on the oral health of elderly residents of nursing homes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 33(2):115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]