Abstract

Elbow arthroscopy can be a challenge, however, indications and benefits compared to open elbow surgery are rapidly evolving. The elbow has seemed to lag behind other joints including the knee, shoulder, ankle and the hip, both in number of cases and in widespread acceptance, as a joint amenable to arthroscopic management. This has occurred despite literature demonstrating successful utilization of arthroscopy in the management of a variety of injuries. The purpose of this review is to clarify and expand the indications for arthroscopy of the elbow in 2021. We will also offer tips and tricks to help make elbow arthroscopy more successful. Since originally publishing these guidelines in 2007, elbow arthroscopy has evolved, although the principles and progressions remain the same.

Keywords: Elbow, Elbow arthroscopy, Sports medicine

Introduction

Elbow arthroscopy can be a challenge, however, indications and benefits compared to open elbow surgery are rapidly evolving. The elbow has seemed to lag behind other joints including the knee, shoulder, ankle and the hip, both in number of cases and in widespread acceptance, as a joint amenable to arthroscopic management.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 This has occurred despite literature demonstrating successful utilization of arthroscopy in the management of a variety of injuries. The purpose of this review is to clarify and expand the indications for arthroscopy of the elbow in 2021. We will also offer tips and tricks to help make elbow arthroscopy more successful. Since originally publishing these guidelines in 2007, elbow arthroscopy has evolved, although the principles and progressions remain the same.6

The initial indications for elbow arthroscopy were for assistance in diagnosis and in removal of loose bodies. These original arthroscopic elbow surgeries were first conceptualized by Burman,7 but the field found wider acceptance because of studies by Lynch et al.,8 Andrews and Carson,9 Johnson,10 Poehling et al.,11 and Morrey.12 Once diagnostic elbow arthroscopy became more accepted, further surgical management of more complicated pathologies was attempted.12, 13, 14 Presently, debridement, drilling, autograft or allograft replacement surgery for capitellar defects, debridement and repair of lateral epicondylitis, management of arthritis and ankyloses, and fractures of the radial head, capitellum, and distal humerus are all considered to be standard indications for management by elbow arthroscopy. Various forms of elbow instability, including varus, valgus, and posterolateral, are an indication for diagnostic arthroscopy and debridement, with varus and posterolateral rotatory instability being a relative indication for arthroscopic repair or reconstruction. Additional relative indications include triceps tendon repair as well as debridement of olecranon bursitis, olecranon spurring, ulnar nerve constriction isolated to the proximal cubital tunnel, coronoid fractures and partial tears of the distal biceps.

Contraindications

Currently, reconstruction of the medial ulnar collateral ligament (MUCL), as well as debridement and repair of medial epicondylitis with ulnar nerve irritation (Type 2 medial epicondylitis) should be performed in an open manner after diagnostic arthroscopy secondary to the proximity of the ulnar nerve. Significant disruption of the native anatomy secondary to trauma or severe degenerative arthritis may be a relative contraindication to arthroscopy.

Prior ulnar nerve transposition maybe a relative contraindication depending on the position of the transposed ulnar nerve. Whereas ulnar nerve decompression just proximal to the medial epicondyle can be performed arthroscopically in experienced hands, patients with ulnar nerve compression at the distal portion of the cubital tunnel where the nerve enters the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) are better served with open decompression.

Presently, any indication for surgery of the elbow can also be considered an indication for arthroscopic or arthroscopically assisted management if the anatomy allows. More often than not, the procedure may be better managed arthroscopically than open. There are some procedures traditionally performed in an open manner that, in experienced hands, can be safely performed arthroscopically. It is our belief that the indications for arthroscopic versus open elbow surgery rely more on surgeon experience than on patient pathology. Accordingly, indications detailed below will be divided based on surgeon experience rather than strictly pathology and are intended as a general parameter for when each surgeon's experience allows progression to another level of expertise in elbow arthroscopy. Following this are specific tips and tricks that can be applied across arthroscopic elbow surgery in general.

Stage I: Initial elbow arthroscopy

The main goal in beginning elbow arthroscopy is to understand portal anatomy. Arthroscopy should be approached with a predetermined time limit of 30 min for diagnostic arthroscopy or 60 min for more involved procedures as general guidelines before switching to open surgery to gain experience with normal elbow anatomy. Some examples of procedures in which arthroscopic evaluation of the joint may assist with the open portion and provide the surgeon with valuable experience in elbow arthroscopy include diagnostic arthroscopy procedures to evaluate the joint before open lateral epicondylectomy, ulnar nerve transposition, or radial head excision. Participation at one or more cadaveric courses as well as visiting an experienced elbow arthroscopist prior to the first diagnostic arthroscopy is highly advised and should then be repeated after ten to twenty cases have been completed. The primary risks, especially for the inexperienced surgeon, are injury to the ulnar nerve posteriorly and the radial nerve anteriorly (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The (A) medial and (B) lateral aspects of the elbow illustrate the access sites for arthroscopic instruments and retractors. The grey tube indicates the arthroscope. (n, nerve; a, artery.)

Stage II: Surgical elbow arthroscopy

A continued commitment to learning portal anatomy and safety (Fig. 1) continues to be important, as in no other joint are the neurovascular structures in such close proximity to the operative areas. The use of retractors to protect normal structures during more advanced surgery is the key, which means understanding how to use multiple portals for visualization, surgery and retractors. Being facile with a bridge system for the arthroscope allows placement of cannulas into each portal and the ability to switch the instruments and arthroscope from portal to portal with minimal risk to surrounding tissues. In this stage the surgeon becomes comfortable with instability evaluation, before open reconstruction; loose body removal (Fig. 2); debridement of small coronoid and olecranon spurs in the arthritic elbow; irrigation and debridement of a contaminated or lightly infected elbow joint; and excision of a pathologically swollen, inflamed posterolateral plica associated with radiocapitellar chondromalacia. It is advised that continued attendance to cadaveric courses on elbow arthroscopy be a part of the process of improving surgical skills. Cadaveric practice, always beneficial for surgeons, becomes crucial as surgical indications grow. A maximum time of 60 min or less is recommended as the endpoint at which the elbow should be opened to complete the operation.

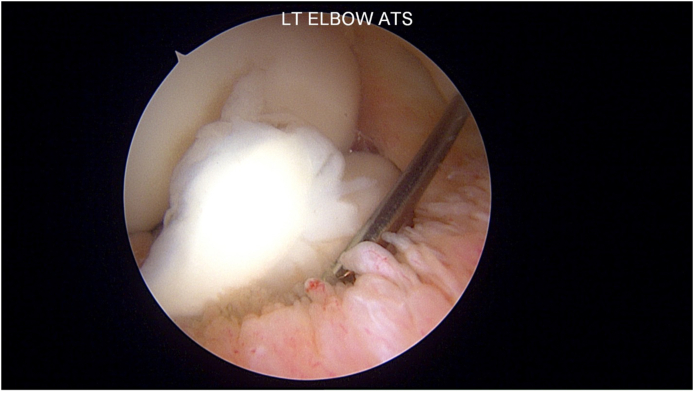

Fig. 2.

Loose body noted in the anterior compartment of a left elbow. The spinal needle can be used to hold it in place in preparation for removal.

Stage III: Advanced elbow arthroscopy

In this third stage, the surgeon has gained a better respect for and has become more comfortable with arthroscopic management of pathologies of the elbow. At this point the surgeon has an awareness of the normal and pathologic anatomy and can visualize the elbow three dimensionally while viewing diagnostic imaging. The aid of retractors to visualize and protect adjacent normal structures is straightforwardly accomplished by this level of surgeon. The complex anatomy of the elbow and particularly the neurovascular structures and their position in specific pathologies has been achieved. While the precise sum of cases required is controversial, most individuals will need at least one hundred cases of elbow arthroscopy to reach this level of proficiency. Additional to the procedures listed in the previous stages, all “normal” operations on the elbow are now an opportunity to improve the patient's results by use of arthroscopy. While we strongly advocate for practice on cadavers and development of a thoughtful “game plan” before each “new” procedure is performed, the majority of surgeons who are at this level are already frequently seeking out cadaveric courses as a regular part of their practice.

The stiff or arthrofibrotic elbow is treated by arthroscopic ankyloses takedown procedures with achievement of a full arc of motion at the time of surgery (Fig. 3). Removal of the entirety of the anterior capsule from septum to septum, release and excision (while protecting the ulnar nerve) of the posterior band of the medial ulnar collateral ligament and elevation of the triceps tendon are accomplished arthroscopically to achieve full elbow motion. If necessary, a small incision can be made over the radial and cubital tunnel to locate and protect the radial and ulnar nerves and use of nerve retractors is effective to safeguard these vital structures throughout the arthroscopic capsular excision.

Fig. 3.

Arthroscopic view of a total elbow arthroplasty after ankyloses takedown and restoration of normal motion.

Debridement with excision of the Nirschl lesion in lateral epicondylitis is easily accomplished arthroscopically, and an anchor can be placed to allow repair of the tendon (Fig. 4).15 Comprehensive arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow comprising synovectomy, resection of coronoid and olecranon spurs, ulnohumeral arthroplasty, and radial head resection, when indicated, is an exceptionally valuable procedure for patients suffering from this ailment. Resection of the olecranon bursa as well as the triceps traction spur can be accomplished by the proficient elbow arthroscopist. Debridement and drilling of osteochondritis dissecans lesions utilizing a 70° arthroscope (Fig. 5A, Fig. 5BA and B) are also considered surgeries better accomplished arthroscopically than open for this surgeon. Fractures of the coronoid, olecranon, and radial head can be evaluated arthroscopically and even managed arthroscopically if they are nondisplaced or minimally displaced to confirm reduction of the articular surface. Synovectomy for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and chronic septic arthritis may also be performed.

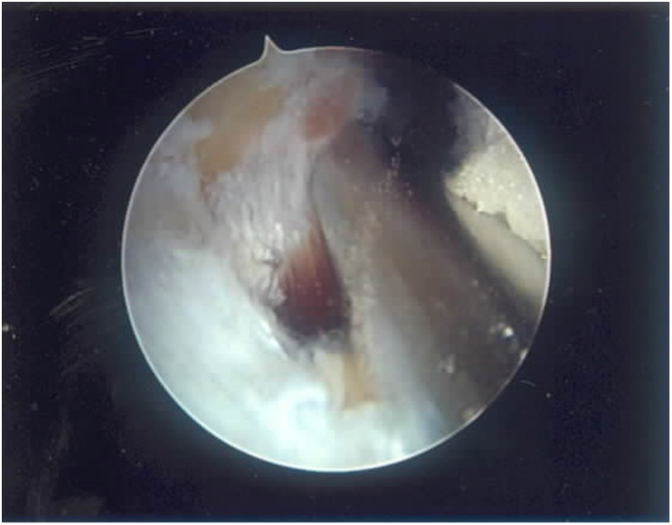

Fig. 4.

View from the medial portal of the Extensor Carpi Radialis Brevis origin. The grey tissue represents angiofibrotic dyplasia, or Nirschle lesion. The shiny white tissue is normal tendon. Excision of the grey tissue is essential for a successful “tennis elbow” procedure.

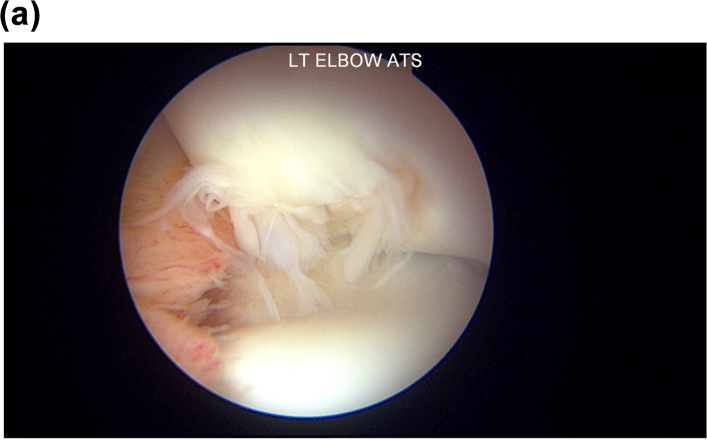

Fig. 5A.

This view from a posterior lateral portal with a 70-degree arthroscope shows an osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum (above), with an inflamed plica laterally and the intact radial head below.

Fig. 5B.

Similar view to Fig. 5A with a 70-degree arthroscope from a posterior lateral portal showing the capitellum (above) after debridement and microfracture of the osteochondral lesion and resection of the plica.

Stage IV: Expansive indications

Arthroscopy can be used to improve outcomes in certain, more difficult cases. Repair of the lateral ligament complex, with or without mid capsular plication for posterolateral instability (PLRI) utilizing anchor placement can also be accomplished arthroscopically. Displaced fractures involving the radial head, coronoid, capitellum, and trochlea may be treated arthroscopically (Fig. 6). Double row triceps tendon repair can be performed both arthroscopically and endoscopically (via the olecranon bursa) with excellent outcomes. Protective retraction as well as decompression of the ulnar nerve has been performed arthroscopically as a part of the capsular release procedures. This has also been utilized in the treatment of advanced degenerative elbow arthritis, which allows for satisfactory release of the nerve and symptomatic relief while lowering the risk of a tardy ulnar nerve palsy. Endoscopic repair of partial and even chronic retracted distal biceps injuries may be performed as well.16

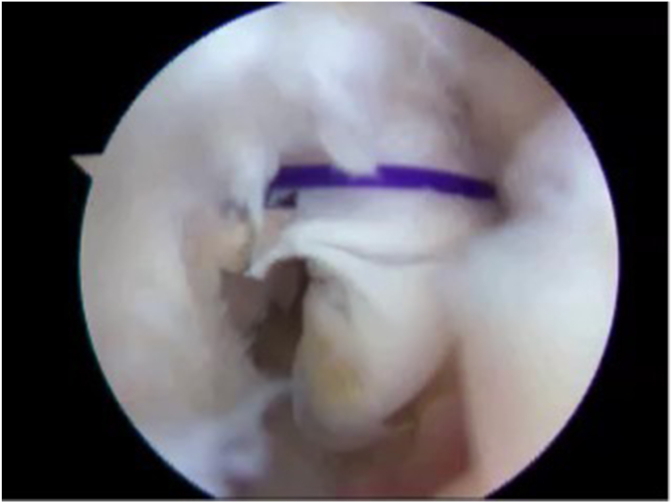

Fig. 6.

Repair of a lateral capitellar fracture utilizing an absorbable suture anchor and substituting the normal suture with an absorbable suture, a modification of the Michael Hausman technique for repair.

Stage V: Future indications

There is great potential for increasingly complex elbow procedures to be performed arthroscopically. In our cadaveric laboratory, we have successfully performed completely arthroscopic posterolateral reconstruction with allograft semitendinosus and interference screw fixation, and fascial interposition arthroplasty. Medial collateral ligament reconstruction may be feasible once better techniques are developed to protect the ulnar nerve. Radial tunnel release and retrieval and repair of complete, retracted ruptures of the distal biceps, though published in the literature,16 also awaits improvement on current surgical techniques to become more mainstream.

Tips and tricks

Room setup

Room setup is one key for ensuring success of the operation. We perform all elbow arthroscopies with the patient prone on a regular operating room table with the upper arm of the operative extremity resting on a cloth bump. This bump in turn, is resting on an arm board folded flush with the side of the table. The arm is typically brought into flexion and internal rotation, resting on the arm board while the initial proximal anteromedial portal is established. Positioning of the arm board can be adjusted, either cranial or caudal, depending on if concomitant medial or lateral elbow surgery needs to be performed. The ulnar nerve is palpated and marked with a marking pen to help maintain orientation throughout the case. The nonsterile tourniquet is inflated to 250 mm Hg after exsanguination with an Esmarch bandage. After tourniquet is inflated, the elbow joint capsule is insufflated with 30 mL of normal saline using an 18-gauge spinal needle either directly posterior or through the soft spot. The spinal needle is then used at the planned proximal anteromedial portal.

Portal placement

For us, the anteromedial portal is 2 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and 2–3 cm anterior to the medial intermuscular septum.

Tip #1: Measure from the medial intermuscular septum, not the medial triceps, to correctly place this portal

Place the cannula by directing it toward the most medial aspect of the anterior elbow joint, trying to penetrate the capsule as medially as possible and then sliding across the joint to end in front of the radial head and capitellum. Extravasation of saline in this position ensures the appropriate trajectory. The needle is then promptly removed in order to maintain joint distention, and an 11 blade is used to establish the first portal. Care is taken to make small incisions involving only the skin. Plunging, while less consequential in arthroscopy of other joints, is not acceptable in the elbow given the close proximity of neurovascular structures.

Numerous varieties of portal placement have been described for elbow arthroscopy. As above, we advocate for placement of the initial proximal anteromedial portal 2 cm proximal and 2–3 cm anterior to the intermuscular septum, a point at which a soft spot can be palpated. This position, which is slightly more anterior than usually described positioning, allows better visualization of the joint and has been shown in cadaveric studies to put fewer structures at risk.17 This more anterior portal also is extremely effective in arthritic elbows in allowing correct access into the joint.

Tip #2: In arthritic elbows move both medial and lateral portals 0.5 mm more anterior to prevent the osteophytes from mis-directing the cannula out of the joint

On the lateral side a modified anterolateral portal is used, which is established 2 cm proximal and 2 cm anterior to the lateral epicondyle. The primary portals on the posterior side include the posterior central portal overlying the olecranon fossa, the posterolateral portal, and the soft spot portal. The proximal anteromedial portal is made initially to visualize the anterior joint, the other portals are made as needed depending on the goals of the surgery.

Tip #3: Use an endoscopic extracapsular capsulectomy to enter the ankylosed/scarred elbow joint

The first goal in elbow arthroscopy is to enter the joint. This can become a challenge in the posttraumatic joint in which significant contractures and scarring are seen. This confined joint space represents a smaller working area in which anatomy can be altered and safety compromised. Entering these difficult joints using an endoscopic extracapsular capsulectomy can be a useful tool to the experienced arthroscopist.18 This technique involves introduction of a periosteal elevator through a proximal anterior medial portal after identification of the ulnar nerve. A channel is then created between the anterior cortex of the humerus and the brachialis musculature. The anterior elbow capsule is then dissected distally from the musculature under direct visualization until the joint line is safely identified.

Protecting vital structures

Protecting vital structures is a key element to all surgery but is even more crucial in elbow arthroscopy where the proximity to nerves and vessels are greater and the learning curve, in becoming comfortable with precise movements using the arthroscope, is steeper. Maintaining visualization either with joint insufflation or retractors is critical. Failure to do this, especially as joint swelling increases, will cause the joint space to collapse leading to poor visualization and higher risk of iatrogenic injury.

Tip #4: Use a switching stick through an accessory portal as a retractor

When working in the anterior elbow, the brachialis muscle serves as a buffer to protect the median and radial nerves as well as the brachial artery. It is important to maintain the brachialis for this reason. A switching stick through an accessory portal can be used to help retract vital structures as necessary. A great application of this is retraction of the brachialis while working in the anterior elbow. This can be especially helpful in the ankylosed joint or while working on the lateral side where the radial nerve is in closer proximity. Likewise, the ulnar nerve should be protected while working on the posteromedial side. If ulnar nerve decompression is indicated, this can be done open prior to the arthroscopy. While the ulnar nerve can be decompressed arthroscopically through the proximal cubital tunnel in the hands of an expert elbow arthroscopist, open decompression is necessary if nerve entrapment is distal. This also allows for protection of the nerve while doing additional work through the arthroscope on the medial side. If proximity to the nerve is in question, an assistant can gently retract the nerve and palpate for when a shaver or other arthroscopic instrument is in close proximity.

Summary

Arthroscopic treatment of elbow pathology marks a continuously evolving field that is growing in conjunction with continued research and advancing technology. The proximity of vital anatomical structures to the joint makes it one of the more challenging joints for the novice arthroscopist, with the risk for serious complications being relatively high. Practice, repetition, and continued experience will keep these risks minimized and allow for the improved outcomes that arthroscopy has delivered in other joints to be seen in the elbow.

References

- 1.Lapner P.C., Leith J.M., Regan W.D. Arthroscopic debridement of the elbow for arthrofibrosis results resulting from nondis- placed fracture of the radial head. Arthroscopy. 2005;21 doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.09.016. 1492.e1-1492.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen D., Proper S.I., MacDermid J.C., King G.J.W., Faber K.J. Functional outcomes of arthroscopic capsular release of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.04.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin R.E., II, Savoie F.H., III, Field L.D., Ramsey J.R. Arthroscopic treatment of the arthritic elbow due to primary radiocapitellar arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mastrokalos D.S., Zahos K.A., Korres D., Soucacos P.N. Arthroscopic debridement and irrigation of periprosthetic total elbow infection. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolla P.R., Surace M.F., Bini A., Pilato G. Arthroscopic treatment of fractures of the radial head. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:233.e1–233.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savoie F.H. Guidelines to becoming and expert elbow arthroscopist. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:123701240. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burman M. Arthroscopy of the elbow joint: a cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1932;14:349–350. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch G.J., Meyers J.F., Whipple T.L., Caspari R.B. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: inherent risks. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(86)80067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews J.R., Carson W.G. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(85)80038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson L.L. Mosby; St Louis, MO, USA: 1986. Arthroscopic Surgery: Principles & Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poehling G.G., Whipple T.L., Sisco L., Goldman B., III Elbow arthroscopy: a new technique. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:222–224. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(89)90176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrey B.F. WB Saunders; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 1985. The Elbow and its Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savoie F.H., Field L.D. Churchill Livingstone; New York, NY, USA: 1996. Arthroscopy of the Elbow. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eames M.H.A., Bain G.I. Distal biceps tendon endoscopy and anterior elbow arthroscopy portal. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;7:139–142. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nirschl R.P., Pettrone F.A. Tennis elbow. The surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1679;61:832–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatia D.N. Endoscopic repair of acute and chronic retracted distal biceps ruptures. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(12):e501–e507. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cusing T., Finley Z., O'Brien M.J., Savoie F.H., Myers L., Medvedev G. Safety of anteromedial portals in elbow arthroscopy: a systematic review of cadaver studies. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(7):2164–2172. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamineni S., Savoie F.H. ElAttrache N endoscopic extracapsular Capsulectomy of the elbow: a neurovascularly safe Technique for high-grade contractures. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:789–792. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]