Highlights

-

•

ZIF-8 synthesis under different mixing speeds, US frequencies, powers and time.

-

•

ZIF-8 crystals were formed after 5 s of reaction time.

-

•

Sonication produced smallest crystals with an average size of 80 nm.

-

•

Varying frequency and power did not significantly affect the crystal properties.

-

•

Ultrasound has both positive and negative impact on crystal properties.

Keywords: MOFs, Ultrasound frequency, Ultrasound power, Mixing, Crystallinity, Crystal size

Abstract

A systematic study on the sonocrystallisation of ZIF-8 (zeolitic imidazolate framework-8) in a water-based system was investigated under different mixing speeds, ultrasound frequencies, calorimetric powers and sonication time. Regardless of the synthesis technique, pure crystals of ZIF-8 with high BET (Brunauer, Emmett and Teller) specific surface area (SSA) can be obtained in water after only 5 s. Furthermore, 5 s sonication produced even smaller crystals (~0.08 µm). The type of technique applied for producing the ZIF-8 crystals did not have any significant impact on crystallinity, purity and yield. Crystal morphology and size were affected by the use of ultrasound and mixing, obtaining nanoparticles with a more spherical shape than in silent condition (no ultrasound and mixing). However, no specific trends were observed with varying frequency, calorimetric power and mixing speed. Ultrasound and mixing may have an effect on the nucleation step, causing the fast production of nucleation centres. Furthermore, the BET SSA increased with increasing mixing speed. With ultrasound, the BET SSA is between the values obtained under silent condition and with mixing. A competition between micromixing and shockwaves has been proposed when sonication is used for ZIF-8 production. The former increases the BET SSA, while the latter could be responsible for porosity damage, causing a decrease of the surface area.

1. Introduction

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are a new class of hybrid, crystalline material with exceptional porosity that makes them very interesting from both scientific and industrial perspectives [1]. MOFs are suitable for any application in which high porosity is required, such as adsorption, gas storage, catalysis, nanoreactors, chemical sensors, and for encapsulation of pharmaceutical ingredients [2], [3], [4], [5]. To date, many different routes have been proposed for producing MOFs, trying to decrease the amount of energy required, reducing both synthesis time and temperature, together with attempts to make the entire process greener [6]. One promising route is sonochemical synthesis, which is the quickest and aligns with the principles of Green Chemistry [6]. Furthermore, it is well-known that sonication contributes to the formation of nanomaterials and nanostructured materials [7], [8]. Many applications require nano-MOFs with narrow particle size distribution i.e. for producing thin nano-layers on membranes, for catalysis or for nanoreactors. Since 2008, when the first MOF was synthesised via sonochemical route [9], many studies have confirmed the benefits of ultrasound (US) [10]. However, reports are often contradictory and no general consensus has been found on the effects of US on MOF synthesis, thus limiting the development and exploitation of this new technique.

In comparison to synthesis without US, the main effects of sonochemical synthesis of MOFs are: a quicker reaction, decrease in crystal size [11], [12], [13], [14], [15] and morphology transformation [16], [17]. However, no clear effects have been detected on the purity [13], [18], [19], [20], while inconsistent results have been reported on effects on surface area and porosity [11], [13], [15], [20], [21], [22]. These inconsistencies are certainly related to the variation among different MOFs: different structures, different bonds and different synthetic routes. In addition, reports on sonosynthesis of MOFs in the literature are limited and different ultrasonic systems are used: horn or ultrasonic baths. It is difficult to directly compare results obtained from these two sonication approaches because of the differences in the cavitation activity [23], [24], [25].

In order to better understand the effects of sonication on the MOF synthesis, it is import to carry out a systematic study on a specific system using the same ultrasonic set-up. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) could be considered an ideal system to study because it is stable in water, which is an important feature considering the presence of water in many applications [26]. Furthermore, ZIF-8 is one of the most studied MOFs in the literature and many synthetic routes have been explored [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]. It has been demonstrated that ZIF-8 can be produced in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [27], methanol [31], [39], [40], isopropyl alcohol [41] and water [33], [34], [35], [42]. In particular, water is an interesting solvent because it is very common, economical and environmentally friendly. However, water-based synthesis of ZIF-8 usually requires a high excess of ligand to improve the deprotonation of the ligand [34]. When the ligand (2-methylimidazole) is dissolved in the solvent, deprotonation occurs producing the imidazolium anion (mim), which contributes directly to the formation of ZIF-8. However, the level of deprotonation, i.e. the amount of free mim is lower in water than in other organic solvents [35]. Attempts to improve the hydrothermal synthesis were reported [34], [35], [42], [43], [44], [45], but sonication has not been systematically considered as a possible technique to apply to the water-based synthesis of ZIF-8.

In this paper, a water-based synthesis of ZIF-8 has been studied following the procedure proposed by Pan et al. [33] involving a high excess of ligand (molar proportion metal:ligand as 1:70). Sonication has been applied using different frequencies and powers for different times. Experiments with different mixing speeds, and in silent as control study, have also been considered for comparison. The effects of different synthesis methods have been studied with respect to purity, yield, crystals size, morphology and BET specific surface area. Although for ZIF-8 the use of US was reported [14], [15], [46], [47], the influence of frequency and power have not been explored. Understanding how these ultrasonic parameters affect the synthesis could clarify the inconsistencies in the literature. In addition, it is possible to find the optimum conditions for synthesising ZIF-8 in water. Another important parameter that will be considered is the influence of sonication time. For the antisolvent sonocrystallisation of sodium chloride, for example, it has been shown previously that it is not necessary to sonicate for the duration of the entire crystallisation period, but only for a short time at the beginning, likely favouring the nucleation [48]. Hence, this possibility was also explored for ZIF-8 synthesis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis of ZIF-8 at room temperature

The procedure of Pan et al. [33] was used in this study as a reference. The metal solution consisted of 0.293 g of zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, 98%, Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in 2 g of de-ionised water, and the ligand solution consisted of 5.675 g of 2-methylimidazole (Hmim, 99%, Sigma Aldrich) dissolved in 20 g of de-ionised water (metal:ligand molar ratio 1:70). The metal solution was then poured into the ligand solution to react for a total time of 5 min at room temperature. After the end of the reaction, the final solution obtained was mixed with 20 mL of chloroform (CHCl3, reagent grade, Fischer Scientific), causing flocculation of the crystals and allowed for its easy separation from the mother liquor. Chloroform was removed via a separatory funnel. The crystals were then recovered from the remaining solution by centrifugation (5000 rpm) with a Thermo Scientific Sorvall ST8 centrifuge. After this first separation, the crystals obtained were washed (20 mL of DI water each) and centrifuged again three times before being dried overnight at 80 °C.

Silent condition was studied first at room temperature, in which the two solutions of metal and ligand were combined and left to react without agitation or sonication. For the mixing experiments the two solutions of metal and ligand were mixed together using a plate mixer with a magnetic stirrer 1 cm in length and 0.5 mm in diameter. Different stirring speeds were applied (298, 562 and 1172 rpm), and the relative rpm were measured using a tachometer.

The set-up used for sonicated experiments is reported in Fig. 1. The wavefield was generated by an amplifier/generator (AG1006, T&C Conversion, USA), connected to a step-up transformer (SUT) for improving the impedance matching (Fig. 1a). The transducer (Honda Electric, Japan) of 6 cm diameter was mounted at the bottom of a Perspex box 12 cm × 12 cm × 15.4 cm (Fig. 1b). The Perspex box was filled with degassed de-ionised water up to ~ 6 cm to ensure that the vial was submerged in the water. Degassed de-ionised water was used to prevent the formation of bubbles that would otherwise attenuate the sound field and maximise the sound field inside the vial. The reactor used was a glass vial of 7 cm height and 2.5 cm diameter, and it was kept suspended in the bath using clamps, keeping a distance from the transducer to the bottom of the vial of ~ 0.5 cm. For the experiments with US, the frequency and the amplifier power setting were varied (98 kHz, 300 kHz and 1 MHz, and 10, 20, 30 and 40 W, respectively). For all the various reaction conditions, different reaction/sonication times were studied, up to a maximum of 5 min, at constant room temperature (22 ± 2 °C).

Fig. 1.

Set-up used for the sonicated experiments: (a) the amplifier with the SUT for matching the impedances, (b) the reactor for ZIF-8 (glass vial), inside a bath (Plexiglas® box) with the plate transducer mounted on the bottom of the box.

2.2. Sonication field characterisation

The US field was measured using different techniques available in the literature. Calorimetry is the most common measure of the cavitation activity, but has its limitations due to the fact that it principally depends on the heat dissipation in the system, therefore dosimetry and sonochemiluminescence (SCL) intensity were also measured.

2.2.1. Calorimetry

Calorimetry was measured with the same set-up used for the experiments, using only DI water as liquid with the same mass as the solution used for the synthesis (27 g). Amplifier power settings between 0 and 40 W have been measured. The calorimetric power (Pcal) has been calculated using the following equation (1):

| (1) |

where m is the mass of water, Cp is the specific heat capacity of the water, T is temperature and t is time. The results of the quantification are reported in Table S1 in Supporting Information.

2.2.2. Chemical dosimetry

Dosimetry was measured using a method already presented in the literature [49]. This quantification was conducted for the ZIF-8 system. A solution of 0.1 M of potassium iodide, (KI, >99%, Fisher Chemical) in de-ionised water was prepared first. After that, 27 mL of the solution was injected in the glass vial used as the reactor for the ZIF-8. The solution was sonicated for different times up to 15 min. Using a quartz cuvette of 1 cm width, a sample of the solution was then analysed with the UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Evolution 201) at 353 nm for obtaining the concentration of triiodide (I3−) in the system, with an extinction coefficient of 2640 m2/mol (or 26400 dm3 mol−1 cm−1). The triiodide formation was linear as a function of time, therefore for a given sonication frequency and power, the rate of the triiodide formation was determined from the slope.

The results are reported in Fig. S1 as function of calorimetric power. In general, the rate of I3− formation increased with the calorimetric power, attributed to the rise in cavitation activity leading to higher HO radical production that can react with the iodide ions [49]. Furthermore, the rate of I3− formation was higher for 300 kHz than for the other frequencies with similar values of calorimetric power, in agreement with previous results where the highest concentration of I3− was found for frequencies between 200 and 500 kHz [49].

2.2.3. Sonochemiluminescence (SCL)

Sonochemiluminescence intensity was captured to demonstrate the presence and spatial distribution of cavitation in the system. SCL is light emissions caused by the free radicals produced through cavitation which can react with luminol to form hydroxylated luminol [50]. A stock solution consisting of 1 mM of luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione, Sigma Aldrich) and 0.1 M of sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Sigma Aldrich) was prepared and 26.6 g of this stock solution was injected in the vial. The vial was then placed inside the Perspex® box with degassed water with the same set-up used for the experiments for ZIF-8. The samples were pre-sonicated for 5 s and the SCL intensity was recorded for an exposure time of 1 s. Images were captured with an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) camera (Andor iXon3). Both camera and vessel were enclosed in a dark box to avoid interference from external light. Observation and calculation of the total integrated light intensity was performed using the Andor Solis software. The images obtained and the graph of the total intensity as function of the calorimetric power are reported in the respective Fig. S2a and S2b for the three frequencies explored. It is evident from the pictures, coupled with the previous results about dosimetry (Fig. S1), that the cavitation activity for 98 kHz and 1 MHz is generally very low, especially at the lowest power. Whereas 300 kHz showed an increase in the light intensity which increased with calorimetric power.

2.3. Segregation index (Xs)

The segregation index is an index of the micromixing level in the system [51], [52]. It varies from 0 (perfect micromixing) to 1 (perfect segregation) and has also been applied for sonicated systems [53], [54]. This index is based on the Villermaux-Dushman reaction, which consists of two parallel competing reactions for protons:

| H2BO3− + H+ ↔ H3BO3 quasi-instantaneous neutralisation reaction | (2) |

| 5I− + IO3− + 6H+ ↔ 3I2 + 3H2O very fast reaction | (3) |

In addition, when there is excess of iodide (I−), all iodine is transformed in triiodide (yellowish appearance), following the reaction:

| I− + I2 ↔ I3− quasi instantaneous equilibrium | (4) |

The procedure requires the addition of small amounts of sulfuric acid in stoichiometric deficiency to the ions in the mixture of iodate (IO3−), iodide (I−) and dihydrogenborate (H2BO3) (buffered solution, Table S2) to induce competition between reactions (2), (3). If the system is in perfect micromixing conditions, reaction (2) is instantaneous, because there is a good dispersion of the acid. When all the H2BO3− is consumed, reactions (3), (4) then occurs for the formation of I3. Therefore, the measurement of I3− concentration gives an indication of the mixing state of the solution, that is lower concentration of I3− indicates the system is well mixed and has low segregation index. The segregation index, denoted as Xs is defined as:

| (5) |

where Y is the ratio of the amount of protons consumed by reaction (3) over the total amount of protons added to the buffered solutions, YST is the value of Y in the case of total segregation, is the volume of the reactor, is the iodine concentration (assumed to be zero because all iodine is transformed in triiodide), is the triiodide concentration, is the volume of acid injected, is the acid concentration, and and are the initial concentrations of iodate ions (0.002M) and borate ions (0.091M) in the buffered solution, respectively. Further details can be found in the Supplementary Information.

It is known that when US is applied, I3− is produced from the effects of cavitation [50], therefore US can interfere with the calculation of the Xs. Jordens et al. [55] reported the importance of correcting the Xs obtained in presence of US by subtracting the quantity of I3− produced by sonication, determined from dosimetry, from the total I3− measured. Therefore, the concentration of I3− used in equation (5) was corrected as follows:

| (I3−)corrected = (I3−)measured – (I3−)sonolysis | (6) |

All the values of segregation index are reported in Fig. S3. Under mixing conditions (Fig. S3, left), Xs decreased with increasing mixing speed, this is because the micromixing was improved. With sonication (Fig. S3, right), the general trend was that Xs decreased with increasing calorimetric power. In addition, the lowest value of Xs was reached with the lowest frequency, 98 kHz, which was expected considering that bubbles collapse stronger at low frequencies and would therefore induce better mixing. This is in agreement with previous results obtained using plate transducers [54], where the values of Xs at 94 kHz were slightly larger than for 1135 kHz.

2.4. Material characterisation

The morphology of crystals was analysed first by scanning electron microscope (SEM, Jeol 7100F). The samples were attached onto suitable stubs with araldite and gold coated (Emitech K575X Sputter Coater) for four cycles, 2 nm each. The SEM images were collected varying the acceleration between 10 and 30 kV. All particle size distribution (PSD) calculated on number basis were obtained analysing around 100 particles. The Feret diameter was used for the size of the crystals. The average particle size has been calculated as follows:

| (7) |

where dj is the mean diameter of the j-th interval of diameters considered, nj is the number of particles with diameters that falls within the j-th interval.

For crystallinity, X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected using an X’Pert ProPANalytical, with Cu Kα radiation (wavelength of 0.15406 nm, 40 mA, 45 kV) in a range of 2θ = 5 – 40°.

For purity, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed in a TA Instruments TGA Q-500 in air, between ambient temperature and 700 °C. The temperature increase was 10 °C/min.

With a high excess of ligand, the percentage yield was calculated based on the mass of MOF crystals obtained from the amount of metal used for the synthesis.

The BET specific surface area (SSA) was measured through N2 adsorption–desorption experiments with a Micromeritics 3Flex. The samples were degassed at 90 °C for 1 h (10 °C/min) and at 200 °C for 8 h (2 °C/min). The analyses were run at −196 °C in liquid nitrogen. The calculation of the BET SSA was based on the guidelines for microporous materials presented in some studies [56], [57], [58]. These guidelines allow more reliable value of BET SSA to be obtained, even if they are not often used in the literature for MOFs. In general, the application of these criteria causes a general increase of the surface area calculated respect to the traditional BET method.

3. Results

For all the results obtained under sonication, calorimetric power, rate of I3− formation and SCL intensity were measured. However, none of these measurements exhibited any clear correlation with the results. Since the general trend is that increasing calorimetric power increases both the rate of I3− formation and SCL intensity, it has been chosen for simplicity to use the calorimetric power as reference.

3.1. XRD

The XRD patterns (Fig. 2) of all the samples crystallised under silent, mixing and sonication showed that pure ZIF-8 was always produced, regardless of the synthesis conditions. In Fig. 2 only some of the patterns collected are reported, together with the simulated pattern of sod-ZIF-8 (sodalite topology). In general, no influence of time has been detected and no differences have been observed among silent, mixing and sonication. Furthermore, mixing speed did not have any impact, and when US was applied, neither frequency nor calorimetric power affected the crystallinity of the final product obtained. Although both dosimetry (Fig. S1) and SCL images (Fig. S2) have proved that cavitation activity was present in the system. All the XRD patterns are in agreement with previous results presented for ZIF-8 synthesised in water at high molar ratio metal:ligand (≥1:35) [33], [34], [35], [37].

Fig. 2.

XRD patterns comparing silent and mixing conditions at room temperature for different times (left), and with US at varying frequencies and powers (right). The simulated pattern of sod-ZIF-8 is from the CIF file Refcode: VELVOY01, CCDC: 602542 [27], obtained with Diamond 3.2.

3.2. TGA

TGA results did not reveal any influence of reaction/sonication times, nor impact of mixing speed, frequency and power on the purity (Fig. S4 in Supporting Information). In all the synthesis conditions considered, the sod-ZIF-8 produced exhibited high purity. This is clear from Fig. S4 that no loss of mass was detected until 400 °C when ZIF-8 degradation starts. This means that no ‘guest’ molecules (impurities or solvent residuals) were present in the samples produced. Similar results have been obtained by Kida et al. [35] for a molar proportion metal:ligand of 1:60.

3.3. Yield

The results for the percentage yield calculated with respect to the metal (Fig. S5 in Supporting Information) showed similar observations to those already obtained for XRD and TGA, that is the yield was not affected by the reaction/sonication time, power, frequency and mixing speed. Silent, mixed or sonicated experiments do not present any significant differences, and the yield remains around 70–90% (Pan et al. [33] obtained ~ 80%), with large error bars. These large error bars are probably due to the recovery step, i.e. the centrifugation. MOFs in fact are usually very porous and consequently very light, therefore their separation would be difficult, especially when they are in the form of nanoparticles (see section 3.5). Very powerful centrifuges are needed (≥10000 rpm): in some cases ultracentrifuges are used for recovering the highest quantity of product possible when it is nanometre sized. This means that the value of the yield does not only depend on the synthesis, but it is also strongly related to the method and efficiency of washing and centrifugation treatments. Therefore, when analysing the yield, it is important to also consider these issues. The conclusion is that the values of yield obtained are all similar and they do not present specific trends.

3.4. Crystal morphology

SEM images of the ZIF-8 crystallised under silent and mixed conditions, and under different sonication conditions are presented in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 respectively. Under silent conditions the crystals were more spherical at 5 s (Fig. 3i), while they have truncated faces and are larger at 300 s (Fig. 3ii). This observation on the morphology change as a function of time is in agreement with the report by Kida et al. [35]. On the other hand, if mixing was applied (Fig. 3iii - vi) the crystals obtained at 300 s were more spherical and much smaller compared to the silent condition obtained at 300 s. No significant differences were detected with increasing mixing speed from 298 to 1172 rpm. When US was applied (Fig. 4), the crystals generated were spherical and small, similar to those obtained with mixing. In addition, growth was detected between 5 and 300 s. However, it is clear in Fig. 4 that the influence of both frequency and power was minor.

Fig. 3.

SEM images of ZIF-8 crystals obtained at room temperature under silent and mixing conditions at 5 s and 300 s.

Fig. 4.

SEM images of ZIF-8 crystals obtained at room temperature under sonicated conditions for different frequencies and powers after 5 s and 300 s.

3.5. Crystal size

In Fig. 5 the average crystal size based on number as a function of time is presented for different mixing speeds (298, 562 and 1172 rpm) and sonication conditions (98 kHz, 0.06 W; 98 kHz, 0.55 W; 300 kHz, 7.52 W; and 1 MHz, 2.78 W). The average crystal size obtained in silent conditions (~0.14 µm) is in line with the previous results presented by Jian et al. [37]: the crystal size was around 0.12 µm with a molar proportion metal:ligand:water equal to 1:70:1280 under no stirring conditions. The values obtained under mixing conditions were in line with the results of Pan et al. [33], who produced nanocrystals around 0.085 µm when stirring was applied during the reaction, but no indications on the mixing speed were available.

Fig. 5.

Average crystal size based on number fraction, comparing silent and mixing conditions (left), and with US comparing different frequencies and powers (right), at room temperature. The lines are drawn to guide the eye. In case of two repetitions, the single values of the two experiments are reported separately.

Fig. 5 shows that, in all conditions studied, a plateau was reached after 30 s of synthesis and no further growth was observed after the initial step. In addition, the use of mixing or sonication decreased the crystal size (~0.11 µm) at the same extent with respect to the silent conditions (~0.14 µm), probably due to an enhancement of mass transfer in both conditions. However, the crystal size obtained after 5 s sonication was slightly smaller (~0.08 µm) than that produced with 5 s mixing (~0.095 µm), but the size after 300 s was the same with both techniques (~0.10 µm).

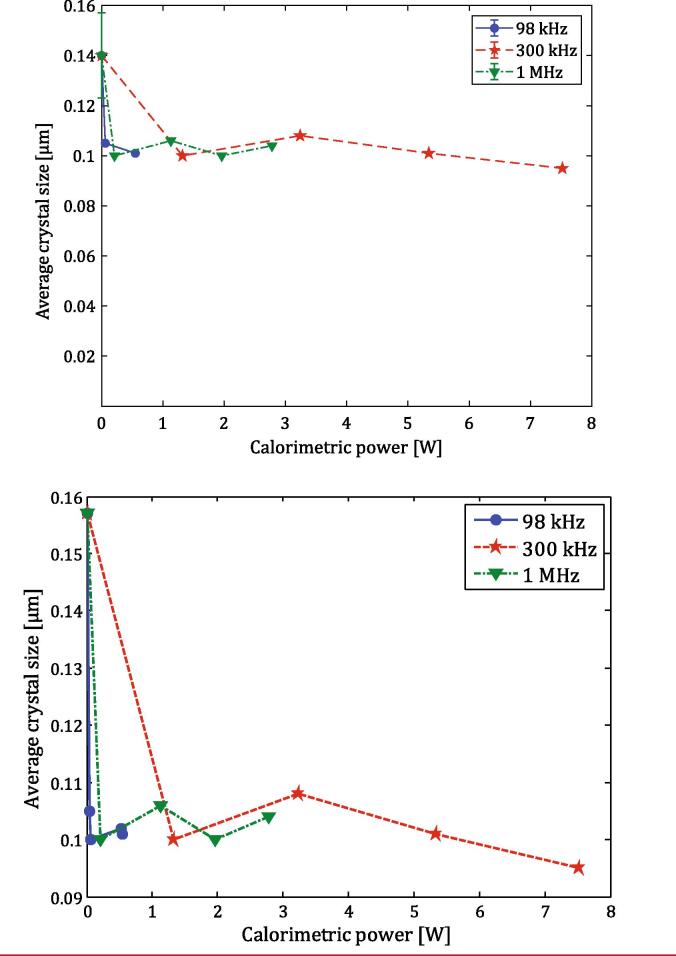

Mixing speeds above 298 rpm had clearly no impact on the crystal size. In addition, no clear influence of frequency or calorimetric power was detected, as it is clear from Fig. 5 right and Fig. S6. Similar particle sizes were in fact obtained despite having used different frequencies and powers. The only exception could be 300 kHz, 7.52 W, which appeared to cause a stronger size reduction (~0.09 µm). This could be related to the stronger cavitation activity enhancing nucleation (see section 2.2). To further clarify this, the average crystal size obtained after 300 s is plotted as a function of calorimetric power for each frequency (Fig. 6). The large jump was between silent conditions (0 W) and the use of US, but no effect of frequency was observed. Furthermore, at calorimetric powers below 4 W there does not appear to be a correlation between calorimetric power and the crystal size, with the crystal sizes fluctuating around similar values. A small correlation was only observed for 300 kHz at calorimetric powers higher than 4 W where the crystal size decreased slightly with increasing power. To confirm this trend, experiments at higher calorimetric powers are probably needed; however, the set-up used here was limited in terms of maximum power supplied by the amplifier, and maximum temperature of the bath to avoid damaging the transducers. Therefore, considering the results presented here it was not possible to conclude a clear dependence of the crystal size on the calorimetric power. It is important to underline that the experiments were run at high excess of ligand which could “hide” differences among the conditions studied.

Fig. 6.

Average crystal size as function of calorimetric power for each frequency studied, considering 300 s synthesis. The lines are interpolations drawn to guide the eye.

In Table 1 the standard deviations (in μm) calculated for each PSD at different synthesis conditions have been reported, indicating how the broadness changes at the different conditions and with time. Furthermore, some of the PSDs are reported in Fig. 7, for silent, mixed and sonicated conditions. Under silent conditions, no significant variations in the standard deviations were detected with time. For all the other conditions, the standard deviation seemed to be smaller than the silent conditions (evident in the narrower PSD in Fig. 7) and increase slightly for longer times, especially between 5 and 30 s. There are no significant differences between mixing and sonication, and no significant trend was observed when changing mixing speed, frequency or calorimetric power. The only significant difference was essentially between silent and all the other conditions studied, both with mixing and sonication. These observations support the hypothesis of an increase in the mass transfer, decreasing the concentration differences in the reactor and the expected wall effect, i.e. homogenising the crystal size.

Table 1.

Standard deviations of PSDs (μm) based on number for each condition studied, for analysing the broadness. In case of two repetitions, the single values obtained from the two experiments are reported separately.

| Time [s] | Silent | Mixing |

98 kHz |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 rpm | 562 rpm | 1172 rpm | 0.05 W | 0.06 W | 0.53 W | 0.55 W | ||

| 5 | 0.034 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.016 | 0.012 0.019 |

0.020 | 0.016 | 0.014 0.016 |

| 30 | 0.038 | 0.016 0.019 |

0.026 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.019 0.022 |

| 300 | 0.031 0.032 |

0.022 0.023 |

0.019 0.024 |

0.020 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.022 | 0.021 |

| Time [s] | 300 kHz |

1 MHz |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.32 W | 3.24 W | 5.34 W | 7.52 W | 0.21 W | 1.13 W | 1.96 W | 2.78 W | |

| 5 | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.013 0.014 |

0.015 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.011 0.013 |

| 30 | 0.021 |

0.018 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.021 |

| 300 | 0.017 |

0.024 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.022 |

Fig. 7.

Particle size distributions (PSD) obtained in (left) silent and mixing conditions and (right) in sonicated conditions, for different frequencies and calorimetric powers. The lines are drawn to guide the eye.

3.6. BET specific surface area

In all conditions studied, the isotherms were Type I, indicating that the materials were microporous [59], [60], normally associated with ZIF-8 crystals [27], [33], [34], [35]. Some isotherms obtained are reported in Fig. S7 as examples. The BET specific surface area (SSA) values calculated from the BET equation are reported for mixed conditions in Fig. 8 left and for sonicated conditions in Fig. 8 right. No significant influence of time on the BET SSA or trends were detected in all the conditions investigated (Fig. S8), in agreement with previous studies with US, where sonication time did not affect the BET SSA [21], [46]. Therefore, it was decided to focus on the possible effects of mixing and sonication parameters instead, and each single point in Fig. 8 represents the average BET SSA and the standard deviation calculated for the three times (5 s, 30 s and 300 s). In general, the values of BET SSA obtained were larger than those presented in the literature for water-based systems [33], [34], [35], [42]. This may be attributed to the different assumptions made for calculating the BET SSA on microporous materials [56], [57], [58].

Fig. 8.

BET specific surface area as function of mixing speed (left) and calorimetric power for three frequencies (right). Each point is the average calculated from the values obtained at different times (5 s, 30 s and 300 s) and the error bars are the relative standard deviations.

Fig. 8 left shows that the BET SSA increased when mixing speed increased. On the other hand, when US was applied, for each frequency, a high calorimetric power caused a decrease in the BET surface area towards the value obtained in silent condition. Furthermore, the BET SSA of ZIF-8 synthesised with US was in general slightly higher than the value obtained in silent conditions, comparable to the values at 298 and 562 rpm. Nevertheless, it is important to note that all the BET surface areas were very similar in case of sonication (between 1500 and 2000 m2/g), especially considering the error bars calculated.

It is evident that a direct comparison between mixing and sonication was not possible in Fig. 8, because the former depends on the mixing speed, while the latter depends on the cavitation activity, here represented in terms of calorimetric power. To create a direct comparison, it is possible to report the data of BET SSA as function of segregation index (SI). This indicates the level of micromixing in the system, therefore being independent from the technique used for inducing the micromixing. In Fig. 9 the values of BET SSA are reported as a function of SI, estimated for each condition (except from silent). No direct correlation between BET SSA and SI was observed. Only in the case of mixing, the highest BET specific surface area corresponds to the lowest value of SI, where the error bars calculated are also smaller. In case of sonication instead, the BET SSA does not depend on the SI, staying flat between 1500 and 2000 m2/g, considering that the error bars in this case are larger.

Fig. 9.

BET specific surface area of the ZIF-8 as function of segregation index. For each frequency, the BET SSA is the average calculated from the BET SSA obtained at different times (5, 30 and 300 s) and the error bars are the relative standard deviations. The two dotted lines represent the upper and lower limits of the standard error bars of the BET SSA obtained under silent condition.

4. Discussion

The main impact of US was on the crystal size, as observed previously for other systems in which US has been applied [9], [11], [12], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [21], [22], [61], [62]. The effects of US and mixing seem to be analogous because similar crystal size reductions were detected. It is possible that sonication initially increases the number of nucleation sites, producing smaller crystals as a consequence and any subsequent crystal growth is inhibited because of the sono-deagglomeration phenomena [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68]. Furthermore, it has been observed that crystals made with only 5 s sonication were smaller than those obtained with 5 s mixing (Fig. 6). This suggests that the influence of sonication on the initial nucleation step is even stronger than that of mixing, because US could produce much more nuclei than mixing, obtaining smaller crystals after the same reaction time.

In the case of MOF synthesis, it is difficult to identify which nucleation is mainly influenced, primary or secondary. Primary nucleation occurs when no crystalline structures are in the system, whereas secondary nucleation needs the presence of crystals to occur [69]. On one hand, it is possible that the internal movement caused by sonication or mixing could homogenise the solution, so it is possible to have more points in which the local supersaturation is high enough to initiate crystallisation, i.e. primary nucleation is increased. On the other hand, mixing or sonication could affect secondary nucleation through collision and fluid shear phenomena, causing attrition and solute layer removal [70]. In both cases the final effect is the rapid increase in the number of nuclei. Coarse fragmentation is excluded for the MOF synthesis since no fragments are formed: the crystals have regular spherical shape with narrower PSD, features difficult to find for irregular fragments.

Another possible explanation is the influence of sonication/mixing on the pH of the solution, which can affect the formation of ZIF-8 because the pH should be basic enough for assuring the deprotonation of the ligand [28], [34], [35], [45]. However, the possibility that sonication or mixing could change the pH is very low. Discarding the use of deprotonators, in general pH mainly depends on the type of solvent used and on the temperature. However, US did not increase the bulk temperature more than 5 – 6 °C (observed during calorimetry), assuming that the nucleation occurred throughout the reaction (max 5 min) as worst-case scenario. Therefore, a change in pH responsible for reducing the crystals size is not expected with such a small variation in temperature. It is likely that sonication and mixing predominantly affects the coordination between metal and ligand, instead of the deprotonation. This is also proved by the yield, which is almost the same in all the conditions studied. If an effect on the deprotonation was expected, the yield should be higher or lower.

There are no previous studies in the literature about the influence of mixing speed on the BET SSA for MOFs. One study on Cu3(BTC)2 showed that increasing the mixing speed decreases the BET surface area [71], but no explanations have been reported. For ZIF-8 it has been proven that the BET SSA increases with reaction time [28], [35], in line with a higher crystallinity. One hypothesis for ZIF-8 formation [28] proposes an initial gel made of a metastable phase from where ZIF-8 crystals start growing until a fully crystalline material is formed. Two mechanisms are responsible of this structural change, the solution-mediated transport and the solid-phase transformation, previously hypothesised for zeolites [72]. In the former, the species needed for building the framework are transported from the liquid phase to the nucleation site, while in the latter the transformation occurs inside the initial amorphous gel through internal reorganisation. Both mechanisms most probably are involved during the ZIF-8 synthesis. Venna et al. [28] showed that for ZIF-8 the transition between amorphous and crystalline phase corresponds to an increase in the BET SSA, since it depends on the rearrangement of the building block in the crystal. The presence of an amorphous initial phase evolving toward a final crystalline phase was also shown elsewhere [30], [31], [32], confirming the similarities between zeolites and ZIFs. In the zeolite synthesis the role of agitation has been studied, even if its role is still unclear. Mixing can interact with many aspects of the reaction, such as reagent dissolution, initial gel formation, the break-up of the gel to initiate the crystalline structure and the transport of the species from the solution [73]. Some studies [74], [75] revealed that a high stirring speed could form a more homogenous and less dense amorphous phase, improving the crystallinity of the final crystals. High mixing speed can also cause shear forces responsible of modifying the growth of the zeolite toward a more stable phase [76]. Considering all these observations, when the two reagents are mixed, high agitation levels could form a more homogeneous amorphous phase. After that, high mixing speed could reduce the duration of the initial transition phase, improving both the dissolution of the initial amorphous gel and the solution-mediated transport of the species. As a consequence, the diffusion of the species from the solution to the nucleation centre is increased, accelerating the transformation toward the crystalline phase. Therefore, it is possible that a lower segregation index (SI), which means higher micromixing level, can result in the ZIF-8 having a higher BET SSA, because the crystallinity is also higher.

On the other hand, sonicated systems seems to behave differently because the BET SSA as function of the segregation index is almost flat (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9). It is well known that cavitation activity causes both microturbulence and shockwaves, which characterise the convection in the system [77]. The BET SSA of crystals produced with US is generally higher than in silent condition because sonication increases the level of micromixing, as it is shown from the value of segregation index in Fig. 9. On the other hand, the presence of shockwaves could negatively affect the surface area. In previous work [46] on the sonication of ZIF-8 particles, made with a conventional synthesis in methanol, showed that an ultrasonic horn at 20 kHz caused localised defects on the crystal surface. In addition, pore blockages have been observed due to the recrystallisation induced by US. Collapses of cavitation bubbles could be responsible for phase transformations similar to what happens with shear forces induced by mixing [76], damaging at the same time the crystal framework. During the crystal growth, bridges are formed using non-framework species for stabilising the pores [32]. The shockwaves in a sonicated system could break these fragile bridges, reducing the internal porosity and the surface area. This hypothesis can also explain why, when increasing the calorimetric power at fixed frequency, the BET SSA tends to slightly decrease towards the value obtained in silent conditions: in this case, the advantages of mixing are cancelled by the increase on collapse strength, reducing the BET SSA. Finally, looking at Fig. 9, 98 kHz gives the lowest segregation index values, but the surface area is similar to the values corresponding to the other frequencies used. This is probably due to the strong bubble collapses typical at low frequencies [25], which may completely remove the benefits of the high micromixing reached in the system. For 300 kHz and 1 MHz, the bubble collapses are weaker due to smaller active bubbles associated with higher frequencies [25] but no significant improvement in BET SSA values were observed. The calorimetric powers used at the higher frequencies are in general higher than the powers used for 98 kHz (Fig. 8 right) and would increase the maximum bubble size reached during expansion, leading to an increase of the shockwaves which could decrease the BET SSA values by damaging the coordination bonds of the framework or promote amorphization of the ZIF-8.

Cavitation bubble population, size and cavitation threshold can vary over different frequency ranges and powers. Therefore, it is possible that a very narrow ultrasound operation window exists in which the micromixing can be maximised and the damage to the coordination bonds of the framework minimised, but have been missed in this study. To confirm the existence of such optimum would require a much smaller variation in frequency and power to be investigated, which require sophisticated instrumentation that may not always be easily sourced.

5. Conclusions

A systematic study on the sonocrystallisation of ZIF-8 in a water-based system has been conducted, exploring different frequencies, powers and sonication time. Moreover, experiments at different mixing speeds and in silent conditions have been carried out for comparison. In general, no significant effects of time have been detected for crystallinity, purity, yield and BET specific surface area (SSA), while for crystal size a growth is observed between 5 and 30 s, before reaching a plateau. Both sonication and mixing mainly cause a crystal size reduction with respect to the silent condition producing nanoparticles, but no clear trends have been detected using different frequencies, calorimetric powers or mixing speeds. On the other hand, crystallinity, purity and yield were not affected by any condition considered. It has been hypothesised that sonication and mixing probably influence the nucleation step, increasing rapidly the number of nucleation centres and consequently hindering the growth. In addition, it has been concluded that the effects of sonication on the nucleation are more significant than for mixing. Effects on the pH have been excluded, considering that solvents and temperature are kept constant and that no basic deprotonators were used.

Finally, the BET SSA increases with higher mixing speed. With sonication, instead, the BET SSA reached is lower than that attained with mixing, but slightly higher than with silent conditions. This behaviour could be explained by the competition between micromixing, which increases the BET SSA, and the shockwaves, which can break the framework consequently decreasing the surface area. Therefore, the synthesis of ZIF-8 in water can be shortened because pure crystals with high BET SSA can be obtained in only 5 s. Furthermore, with only 5 s sonication it is possible to obtain even smaller crystals (~0.08 µm). However, in general sonication does not significantly improve the reaction nor the final product. The features of the crystals obtained resemble the ones produced by mixing except for the BET SSA: with high stirring speed the surface area produced is higher, while with sonication there is no significant improvement.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Silvia Nalesso: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Gaelle Varlet: Methodology, Validation, Investigation. Madeleine J. Bussemaker: Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition. Richard P. Sear: Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition. Mark Hodnett: Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition. Rebeca Monteagudo-Oliván: Validation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Victor Sebastián: Validation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Joaquín Coronas: Resources, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Judy Lee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Armourers & Brasiers’ Company through the Armourers & Brasiers’ Company Travel Grant. Spanish authors would like to acknowledge financial support from Research Project MAT2016-77290-R (AEI/FEDER, UE). The work was also supported by the UK Government’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), through the UK’s National Measurement System programmes.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105616.

Contributor Information

Silvia Nalesso, Email: silvia.nalesso.87@gmail.com.

Joaquín Coronas, Email: coronas@unizar.es.

Judy Lee, Email: j.y.lee@surrey.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Férey G. Hybrid porous solids: past, present, future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37(1):191–214. doi: 10.1039/b618320b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu G., Li S., Guo Z., Farha O.K., Hauser B.G., Qi X., Wang Y.i., Wang X., Han S., Liu X., DuChene J.S., Zhang H., Zhang Q., Chen X., Ma J., Loo S.C.J., Wei W.D., Yang Y., Hupp J.T., Huo F. Imparting functionality to a metal-organic framework material by controlled nanoparticle encapsulation. Nat. Chem. 2012;4(4):310–316. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunha D., Ben Yahia M., Hall S., Miller S.R., Chevreau H., Elkaïm E., Maurin G., Horcajada P., Serre C. Rationale of Drug Encapsulation and Release from Biocompatible Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Mater. 2013;25(14):2767–2776. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu S., Xue M., Zhu G. Metal-organic framework membranes: from synthesis to separation application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43(16):6116–6140. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paseta L., Simón-Gaudó E., Gracia-Gorría F., Coronas J. Encapsulation of essential oils in porous silica and MOFs for trichloroisocyanuric acid tablets used for water treatment in swimming pools. Chem. Eng. J. 2016;292:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dey C., Kundu T., Biswal B.P., Mallick A., Banerjee R. Crystalline metal-organic frameworks (MOFs): synthesis, structure and function. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B: Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2014;70:3–10. doi: 10.1107/S2052520613029557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gedanken A. Using sonochemistry for the fabrication of nanomaterials. Ultrasonics – Sonochemistry. 2004;11(2):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bang J.H., Suslick K.S. Applications of Ultrasound to the Synthesis of Nanostructured Materials. Adv. Mater. 2010;22(10):1039–1059. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu L.-G., Li Z.-Q., Wu Y., Wang W., Xu T., Jiang X. Facile synthesis of nanocrystals of a microporous metal–organic framework by an ultrasonic method and selective sensing of organoamines. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2008;(31):3642. doi: 10.1039/b804126a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safarifard V., Morsali A. Applications of ultrasound to the synthesis of nanoscale metal–organic coordination polymers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015;292:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Son W.-J., Kim J., Kim J., Ahn W.-S. Sonochemical synthesis of MOF-5. ChemComm. 2008;(47):6336. doi: 10.1039/b814740j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan N.A., Jhung S.-H. “Facile Syntheses of Metal-organic Framework Cu3(BTC)2(H2O)3 under Ultrasound”. Ultrasound Synthesis of Cu3. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2009;30(12):2921–2926. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang S.-T., Kim J., Cho H.-Y., Kim S., Ahn W.-S. Facile synthesis of covalent organic frameworks COF-1 and COF-5 by sonochemical method. RSC Adv. 2012;2(27):10179. doi: 10.1039/c2ra21531d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seoane B., Zamaro J.M., Tellez C., Coronas J. Sonocrystallization of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIF-7, ZIF-8, ZIF-11 and ZIF-20) CrystEngComm. 2012;14(9):3103. doi: 10.1039/c2ce06382d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho H.-Y., Kim J., Kim S.-N., Ahn W.-S. High yield 1-L scale synthesis of ZIF-8 via a sonochemical route. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013;169:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z.-Q., Qiu L.-G., Wang W., Xu T., Wu Y., Jiang X. Fabrication of nanosheets of a fluorescent metal–organic framework [Zn(BDC)(H 2 O)] n (BDC = 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate): Ultrasonic synthesis and sensing of ethylamine. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2008;11(11):1375–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang D.-A., Cho H.-Y., Kim J., Yang S.-T., Ahn W.-S. CO 2 capture and conversion using Mg-MOF-74 prepared by a sonochemical method †. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012;5(4):6465–6473. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung D.-W., Yang D.-A., Kim J., Kim J., Ahn W.-S. Facile synthesis of MOF-177 by a sonochemical method using 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone as a solvent. Dalton Trans. 2010;39(11):2883. doi: 10.1039/b925088c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tahmasian A., Morsali A. Ultrasonic synthesis of a 3D Ni(II) Metal-organic framework at ambient temperature and pressure: New precursor for synthesis of nickel(II) oxide nano-particles. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2012;387:327–331. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sargazi G., Afzali D., Ghafainazari A., Saravani H. Rapid Synthesis of Cobalt Metal Organic Framework. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. 2014;24(4):786–790. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z.-Q., Qiu L.-G., Xu T., Wu Y., Wang W., Wu Z.-Y., Jiang X. Ultrasonic synthesis of the microporous metal–organic framework Cu 3 (BTC) 2 at ambient temperature and pressure: An efficient and environmentally friendly method. Mater. Lett. 2009;63(1):78–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beyer S., Prinz C., Schürmann R., Feldmann I., Zimathies A., Blocki A.M., Bald I., Schneider R.J., Emmerling F. Ultra-Sonication of ZIF-67 Crystals Results in ZIF-67 Nano-Flakes. ChemistrySelect. 2016;1(18):5905–5908. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crum L.A., Reynolds G.T. Sonoluminescence Produced by Stable Cavitation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1985;78(1):137–139. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutkar V.S., Gogate P.R., Csoka L. Theoretical prediction of cavitational activity distribution in sonochemical reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2010;158(2):290–295. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J. Handb. Ultrason. Sonochemistry. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2016. Importance of sonication and solutions conditions on the acoustic cavitation activity; pp. 137–175. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C., Liu X., Keser Demir N., Chen J.P., Li K. Applications of water stable metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45(18):5107–5134. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00362a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park K.S., Ni Z., Côté A.P., Choi J.Y., Huang R., Uribe-Romo F.J., Chae H.K., O’Keeffe M., Yaghi O.M. Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:10186–10191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602439103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venna S.R., Jasinski J.B., Carreon M.A. Structural Evolution of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8. JACS Commun. 2010;132(51):18030–18033. doi: 10.1021/ja109268m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paseta L., Potier G., Sorribas S., Coronas J. Solventless synthesis of MOFs at high pressure. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016;4(7):3780–3785. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terban M.W., Banerjee D., Ghose S., Medasani B., Shukla A., Legg B.A., Zhou Y., Zhu Z., Sushko M.L., De Yoreo J.J., Liu J., Thallapally P.K., Billinge S.J.L. Early stage structural development of prototypical zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF) in solution. Nanoscale. 2018;10(9):4291–4300. doi: 10.1039/c7nr07949d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cravillon J., Schroder C.A., Nayuk R., Gummel J., Huber K., Wiebcke M., Cravillon J., Schrçder C.A., Wiebcke M., Nayuk R., Huber K., Gummel J. Fast Nucleation and Growth of ZIF-8 Nanocrystals Monitored by Time-Resolved In Situ Small-Angle and Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:8067–8071. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moh Pak Y., Cubillas Pablo, Anderson Michael W., Attfield Martin P. Revelation of the molecular assembly of the nanoporous metal organic framework ZIF-8. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133(34):13304–13307. doi: 10.1021/ja205900f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan Yichang, Liu Yunyang, Zeng Gaofeng, Zhao Lan, Lai Zhiping. Rapid synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanocrystals in an aqueous system. Chem. Commun. 2011;47(7):2071. doi: 10.1039/c0cc05002d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka Shunsuke, Kida Koji, Okita Muneyuki, Ito Yosuke, Miyake Yoshikazu. Size-controlled Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8) Crystals in an Aqueous System at Room Temperature. Chem. Lett. 2012;41(10):1337–1339. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kida Koji, Okita Muneyuki, Fujita Kosuke, Tanaka Shunsuke, Miyake Yoshikazu. Formation of high crystalline ZIF-8 in an aqueous solution. CrystEngComm. 2013;15(9):1794. doi: 10.1039/c2ce26847g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee Yu-Ri, Jang Min-Seok, Cho Hye-Young, Kwon Hee-Jin, Kim Sangho, Ahn Wha-Seung. ZIF-8: A comparison of synthesis methods. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;271:276–280. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jian Meipeng, Liu Bao, Liu Ruiping, Qu Jiuhui, Wang Huanting, Zhang Xiwang. Water-based synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 with high morphology level at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2015;5(60):48433–48441. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson Joseph P., Abellan Patricia, Denny Michael S., Park Chiwoo, Browning Nigel D., Cohen Seth M., Evans James E., Gianneschi Nathan C. Observing the Growth of Metal-Organic Frameworks by in Situ Liquid Cell Transmission Electron Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137(23):7322–7328. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cravillon Janosch, Münzer Simon, Lohmeier Sven-Jare, Feldhoff Armin, Huber Klaus, Wiebcke Michael. Rapid room-temperature synthesis and characterization of nanocrystals of a prototypical zeolitic imidazolate framework. Chem. Mater. 2009;21(8):1410–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cravillon Janosch, Nayuk Roman, Springer Sergej, Feldhoff Armin, Huber Klaus, Wiebcke Michael. Controlling zeolitic imidazolate framework nano- and microcrystal formation: Insight into crystal growth by time-resolved in situ static light scattering. Chem. Mater. 2011;23(8):2130–2141. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett Thomas D., Saines Paul J., Keen David A., Tan Jin-Chong, Cheetham Anthony K. Ball-milling-induced amorphization of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) for the irreversible trapping of iodine. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2013;19(22):7049–7055. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gross Adam F., Sherman Elena, Vajo John J. Aqueous room temperature synthesis of cobalt and zinc sodalite zeolitic imidizolate frameworks. Dalton Trans. 2012;41(18):5458. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30174a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao Jianfeng, He Ming, Wang Kun, Chen Rizhi, Zhong Zhaoxiang, Wang Huanting. High-yield synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks from stoichiometric metal and ligand precursor aqueous solutions at room temperature. CrystEngComm. 2013;15(18):3601. doi: 10.1039/c3ce27093a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Binling, Bai Fenghua, Zhu Yanqiu, Xia Yongde. Hofmeister anion effect on the formation of ZIF-8 with tuneable morphologies and textural properties from stoichiometric precursors in aqueous ammonia solution. RSC Adv. 2014;4(88):47421–47428. [Google Scholar]

- 45.He Ming, Yao Jianfeng, Liu Qi, Wang Kun, Chen Fanyan, Wang Huanting. Facile synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 from a concentrated aqueous solution. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014;184:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson Joshua A., Chapman Karena W., Koros William J., Jones Christopher W., Nair Sankar. Sonication-induced Ostwald ripening of ZIF-8 nanoparticles and formation of ZIF-8/polymer composite membranes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;158:292–299. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amali Arlin Jose, Sun Jian-Ke, Xu Qiang. From assembled metal–organic framework nanoparticles to hierarchically porous carbon for electrochemical energy storage. Chem. Commun. Chem. Commun. 2014;50(13):1519–1522. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48112c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nalesso Silvia, Bussemaker Madeleine J., Sear Richard P., Hodnett Mark, Lee Judy. Development of Sodium Chloride Crystal Size during Antisolvent Crystallization under Different Sonication Modes. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019;19(1):141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koda Shinobu, Kimura Takahide, Kondo Takashi, Mitome Hideto. A standard method to calibrate sonochemical efficiency of an individual reaction system. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003;10(3):149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(03)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ashokkumar Muthupandian, Lee Judy, Kentish Sandra, Grieser Franz. Bubbles in an acoustic field: An overview. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14(4):470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guichardon Pierrette, Falk Laurent. Characterisation of micromixing efficiency by the iodide-iodate reaction system. Part I: experimental procedure. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2000;55(19):4233–4243. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fournier M.-C., Falk L., Villermaux J. A new parallel competing reaction system for assessing micromixing efficiency- experimental approach. Pergamon Chem. Eng. Sci. 1996;51(22):5053–5064. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee Judy, Ashokkumar Muthupandian, Kentish Sandra E. Influence of mixing and ultrasound frequency on antisolvent crystallisation of sodium chloride. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jordens Jeroen, Bamps Bram, Gielen Bjorn, Braeken Leen, Van Gerven Tom. The effects of ultrasound on micromixing. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;32:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jordens Jeroen, Appermont Tessa, Gielen Bjorn, Van Gerven Tom, Braeken Leen. Sonofragmentation: Effect of Ultrasound Frequency and Power on Particle Breakage. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016;16(11):6167–6177. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parra J.B., Sousa J.C. De, Bansal Roop C., Pis J.J., Pajares J.A. Characterization of Activated Carbons by the BET Equation — An Alternative Approach. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 1995;12(1):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rouquerol J., Llewellyn P.L., Rouquerol J. 7th Int. Symp. Charact. Porous Solids. Elsevier; Amsterdam and Oxford: 2007. Is the BET equation applicable to microporous adsorbents? pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walton Krista S., Snurr Randall Q. Applicability of the BET Method for Determining Surface Areas of Microporous Metal-Organic Frameworks. JACS Articles. 2007;129(27):8552–8556. doi: 10.1021/ja071174k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lowell S., Shields J.E., Thomas M.A., Thommes M. Springer Netherlands; Characterization of Porous Solids and Powders: 2004. Characterization of Porous Solids and Powders: Surface Area, Pore Size and Density“. Characterization of Porous Solids and Powders: Surface Area, Pore Size and Density. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Condon J.B. Measurements and Theory, First edit, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam; Dordrecht: 2006. Surface Area and Porosity Determinations by Physisorption: Measurements and Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mehrani Azadeh, Morsali Ali, Hanifehpour Younes, Joo Sang Woo. Sonochemical temperature controlled synthesis of pellet-, laminate- and rice grain-like morphologies of a Cu(II) porous metal-organic framework nano-structures. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21(4):1430–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alavi Mohammad Amin, Morsali Ali. Ultrasound assisted synthesis of [Cu2(BDC)2(dabco)].2DMF.2H2O nanostructures in the presence of modulator; new precursor to prepare nano copper oxides. Ultrasonics - Sonochemistry. 2014;21(2):674–680. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo Z., Jones A.G., Li N., Germana S. High-speed observation of the effects of ultrasound on liquid mixing and agglomerated crystal breakage processes. Powder Technol. 2007;171(3):146–153. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gielen B., Jordens J., Thomassen L.C.J., Braeken L., Van Gerven T. Agglomeration control during ultrasonic crystallization of an active pharmaceutical ingredient. Crystals. 2017;7 pp. 40–1/20. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Hong, Li Hairong, Guo Zhichao, Liu Yu. The application of power ultrasound to reaction crystallization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2006;13(4):359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim Jong-Min, Chang Sang-Mok, Kim Kyo-Seon, Chung Min-Kyu, Kim Woo-Sik. Acoustic influence on aggregation and agglomeration of crystals in reaction crystallization of cerium carbonate. Physicochem. Eng. Aspects. 2011;375(1-3):193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sivabalan R., Gore G.M., Nair U.R., Saikia A., Venugopalan S., Gandhe B.R. Study on ultrasound assisted precipitation of CL-20 and its effect on morphology and sensitivity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007;139(2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bari A.H., Chawla A., Pandit A.B. Sono-crystallization kinetics of K2SO4: Estimation of nucleation, growth, breakage and agglomeration kinetics. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;35:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mullin J.W. fourth ed. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford, USA: 2001. “Crystallization”. Crystallization. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agrawal S.G., Paterson A.H.J. Secondary Nucleation: Mechanisms and Models. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2015;202(5):698–706. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim Jun, Kim Sun-Hee, Yang Seung-Tae, Ahn Wha-Seung. Bench-scale preparation of Cu 3 (BTC) 2 by ethanol reflux: Synthesis optimization and adsorption/catalytic applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;161:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davis Mark E., Lobo Raul F. Zeolite and molecular sieve synthesis. Chem. Mater. 1992;4(4):756–768. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Casci John L. Zeolite molecular sieves: preparation and scale-up. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005;82(3):217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng Y., Liao R.H., Li J.S., Sun X.Y., Wang L.J. Synthesis research of nanosized ZSM-5 zeolites in the absence of organic template. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008;206(1-3):445–452. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mainganye Dakalo, Ojumu Tunde, Petrik Leslie. Synthesis of Zeolites Na-P1 from South African Coal Fly Ash: Effect of Impeller Design and Agitation. Materials. 2013;6(5):2074–2089. doi: 10.3390/ma6052074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marrot B., Bebon C., Colson D., Klein J.P. Influence of the Shear Rate During the Synthesis of Zeolites. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2001;36(3):269–281. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nalajala Venkata Swamy, Moholkar Vijayanand S. Investigations in the physical mechanism of sonocrystallization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18(1):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.