Abstract

Purpose

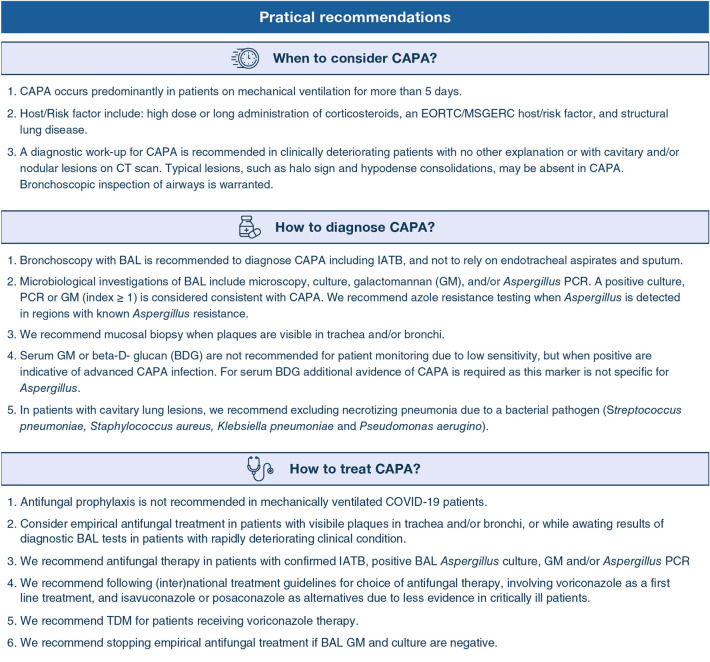

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is increasingly reported in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Diagnosis and management of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) are challenging and our aim was to develop practical guidance.

Methods

A group of 28 international experts reviewed current insights in the epidemiology, diagnosis and management of CAPA and developed recommendations using GRADE methodology.

Results

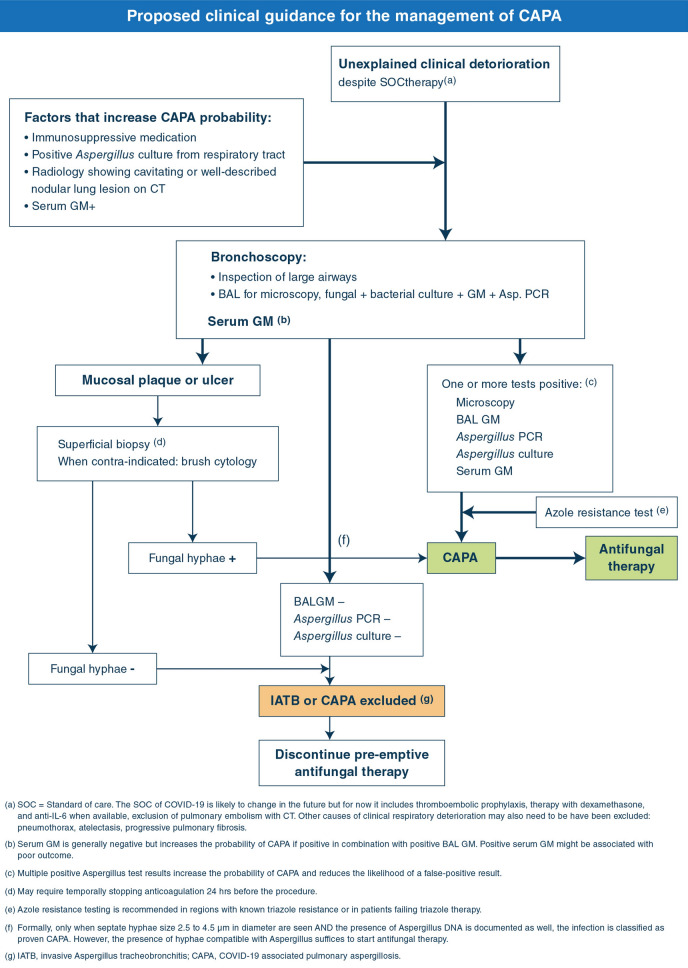

The prevalence of CAPA varied between 0 and 33%, which may be partly due to variable case definitions, but likely represents true variation. Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) remain the cornerstone of CAPA diagnosis, allowing for diagnosis of invasive Aspergillus tracheobronchitis and collection of the best validated specimen for Aspergillus diagnostics. Most patients diagnosed with CAPA lack traditional host factors, but pre-existing structural lung disease and immunomodulating therapy may predispose to CAPA risk. Computed tomography seems to be of limited value to rule CAPA in or out, and serum biomarkers are negative in 85% of patients. As the mortality of CAPA is around 50%, antifungal therapy is recommended for BAL positive patients, but the decision to treat depends on the patients’ clinical condition and the institutional incidence of CAPA. We recommend against routinely stopping concomitant corticosteroid or IL-6 blocking therapy in CAPA patients.

Conclusion

CAPA is a complex disease involving a continuum of respiratory colonization, tissue invasion and angioinvasive disease. Knowledge gaps including true epidemiology, optimal diagnostic work-up, management strategies and role of host-directed therapy require further study.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-021-06449-4.

Keywords: Viral pneumonia, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Invasive aspergillosis, ICU

Take-home message

| COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) is associated with excess mortality and requires bronchoscopy and BAL to diagnose. Antifungal therapy is recommended in CAPA, while discontinuation or tapering of concomitant corticosteroid therapy could be considered in patients who do not respond. |

Introduction

Soon after the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, reports of suspected invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) complicating COVID-19 appeared both from clinical and post-mortem findings [1, 2]. Over the past years, IPA secondary to seasonal influenza was recognized as an emerging clinical entity in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with respiratory failure [3]. Cases of influenza associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) were reported in up to 19% of influenza patients in the ICU [3]. The mortality rate was 51% compared to 28% in influenza patients without IAPA [3]. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) has been reported to have a similar mortality rate of 52% [4]. However, there are clear differences between IAPA and CAPA, including different patients’ typology and comorbidities, viral lytic effects and tissue tropism, host immune response as well as performance of Aspergillus diagnostic tests. Furthermore, the frequent detection of Aspergillus species or galactomannan (GM) in airway samples from critically ill COVID-19 patients, limited evidence of histopathological confirmation of CAPA at autopsy and reports of patients with CAPA who survived without receiving antifungal therapy, has challenged existing thoughts on the best diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. A group of experts set out to write practical and evidence-based guidance based on seven key questions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key questions

| 1. What is the case definition of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis? |

| 2. What is the optimal approach towards diagnosing or refuting CAPA in patients with COVID-19? |

| 3. What is the reported prevalence of Aspergillus pneumonia in patients with COVID-19? |

| 4. What are the host-/risk factors that are associated with COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA)? |

| 5. Is antifungal therapy indicated in patients suspected of CAPA? |

| 6. How should invasive Aspergillus tracheobronchitis be managed in CAPA patients? |

| 7. What is the role of immunomodulating agents in the management of CAPA in ICU patients? |

Methods

The taskforce consisted of 28 participants from eight European countries, the United States and Taiwan. Participants were selected based on internationally recognized experience, academic leadership, and field of expertise, including medical microbiology/infection control (PEV, KL, JBB, CL-F, TRR), infectious diseases (BJAR, MB, TCa, CJC, OAC, OL, MH-N, TFP, FLvdV), intensive care medicine (EA, SB, PD, DdL, PK, PW-LL, AR, JAS, LV, JW, IM-L), clinical pharmacology (RJMB, RL), public health (TCh) and hematology (OAC, PK, JM). Selected participants furthermore had specific expertise in epidemiology, diagnosis and management of invasive fungal diseases or fungal disease guideline development, and most participants had previously contributed to the IAPA case definition [5]. The key questions were discussed and regarded well-focused and relevant by all panel members. As the literature regarding CAPA is very limited, the PICo framework for qualitative research questions was followed, involving population characteristics, disease of interest, and context [6]. For each key question we developed short evidence summaries after searching PubMed, Embase and when available, the medRxiv pre-print server and pre-print publications. The search strategy included the following MESH terms (coronavirus or COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2) and (Aspergillus* or aspergillosis* or CAPA). The evidence was subsequently discussed during an online group meeting and quality of evidence for clinically relevant outcomes was graded from high to very low following the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology [7], involving categories of outcome, summary of evidence using evidence tables, and assessment of quality of evidence. The panel formulated recommendations after structured discussions based on the collected evidence. When evidence could not be obtained, recommendations were provided on the basis of opinions and experiences (good practice statements, GPS). Based on this process, we formulated 13 recommendations on the management of patients with a proven COVID-19 and Aspergillus colonization or possible, probable or proven CAPA.

Key questions

What is the case definition of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis?

Evidence summary

A rapidly increasing number of papers on CAPA (125 publications by April 1st) are being reported in the literature. One problem is the lack of a consensus CAPA operational case definition, as various definitions have been used to classify CAPA. The invasive fungal disease case definition of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Mycosis Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSGERC) is rarely applicable because it only applies to patients with specific host factors, which are typically absent in patients suspected of having CAPA [8]. Several studies have used the algorithm that was proposed by Blot et al. to distinguish between putative IPA and Aspergillus colonization in the ICU [9]. As this classification is based on a positive culture, sometimes revised definitions were used, which also include the biomarker GM in serum or BAL [10]. Other studies have used the criteria which were used by Schauwvlieghe et al. [3] to classify patients with IAPA or the IAPA case definition proposed by an expert panel [5]. The expert panel indicated that the IAPA case definition may also be applied to classify CAPA cases, but at that time there was limited scientific evidence and clinical experience [5]. In December 2020 a consensus CAPA case definition was published by the European Confederation for Medical Mycology (ECMM) and the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology (ISHAM) [11], categorizing patients as proven, probable, and possible CAPA. The abovementioned case definitions do not vary regarding proven IPA, as this requires demonstration of invasive growth of Aspergillus species in tissue or sterile sites. Case definitions vary regarding probable, possible or putative categories, mainly regarding the presence of host factors, characteristic lesions on imaging, diagnostic specimens and mycological tests [3, 5, 8, 9, 11]. Inability to classify CAPA patients is mainly due to the absence of host factors, non-typical lesions on computed tomography (CT) and reliance on respiratory specimens other than bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) obtained through bronchoscopy. The 2020 ISHAM/ECMM consensus definitions permit classification of most CAPA patients, including those who have undergone non-bronchoscopic procedures, such as non-bronchoscopic bronchial lavage (NBL) to obtain mycological evidence [11]. CAPA patients diagnosed through NBL are classified as possible cases, reflecting the uncertainty regarding the diagnostic performance of this (blind) procedure to diagnose IPA, and the lack of validation of Aspergillus tests on this sample type. It is important to note that the possible category in the CAPA definitions differs fundamentally from that used in the EORTC/MSGERC definitions as the latter lacks mycological evidence for IPA, but is defined by “typical” radiological lesions [8, 11].

What is the optimal approach towards diagnosing or refuting CAPA in patients with COVID-19?

| Recommendations | Strength of recommendation | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| A CAPA diagnostic work-up is recommended in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients with unexplained respiratory deterioration or a positive Aspergillus culture from the respiratory tract | Strong | Low |

| Standard CT imaging is not recommended to refute or diagnose CAPA | Weak | Very low |

| Screening of critically ill COVID-19 patients for serum GM or BDG is not recommended | Strong | Low |

| Detection of Aspergillus in sputum and tracheal aspirate is considered insufficient evidence to support CAPA diagnosis, but warrants further diagnostics through bronchoscopy and BAL | Strong | Low |

| We recommend maximum efforts to perform a bronchoscopy for inspection of the airways and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) to diagnose CAPA in patients with proven or high likelihood of COVID-19 in the ICU | Strong | Low |

| There is no recommendation against or in favor of using lateral flow devices-based assays for diagnosing CAPA | Weak | Very low |

Evidence summary

Mycology Bronchoscopy with BAL has become the most important tool to diagnose IPA. BAL samples have been validated for microscopy (using optical brighteners such as Blankophor P or calcofluor white), which provides rapid results and helps to interpret culture results. Furthermore, Aspergillus culture, detection of GM and Aspergillus DNA PCR tests for species identification and detection of azole resistance markers have been reasonably well validated on BAL fluid. Detection of Aspergillus antigen may take place through ELISA test or with use of a lateral flow device (LFD) point-of-care tests that allows the rapid detection of Aspergillus antigen. Alternatively, GM and beta-d-glucan (BDG), the latter being a panfungal marker and therefore not specific for Aspergillus, may be detected in serum of patients with IPA.

Although bronchoscopy was generally discouraged in COVID-19 patients during the first wave, evaluation for co-infection is considered an indication to perform this procedure [12], provided that adequate preventive measures are taken to protect health care workers [13]. Recent studies report that bronchoscopy can be safely performed in COVID-19 patients [14]. In addition, exclusion of co-infection is considered relevant before starting corticosteroid treatment in COVID-19 patients with secondary clinical (respiratory) worsening that is attributed to pulmonary fibrosis or to organizing (non-infectious) pneumonia (cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, COP). Due to restricted availability of bronchoscopy, alternative specimens and procedures have been used, including testing of sputum, bronchial aspirates (BA) and tracheal aspirates (TA), and NBL [11]. Important drawbacks of these specimens include sampling of the upper respiratory tract (BA/TA) rather than lower respiratory tract, lack of validation of Aspergillus biomarkers for these specimens, and inability to visualize the airways, which is critical to diagnose invasive Aspergillus tracheobronchitis (IATB). An overview of the performance of Aspergillus diagnostics in reported case series is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of performance of diagnostic tests in CAPA

| Country | # of CAPA cases | BAL (#positive/#performed) | Aspergillus species | TA/BA (#positive/#performed) | Serum (#positive/#performed) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 9 |

Culture 5/7 GM 2/7 PCR 3/7 |

A. fumigatus (7) |

Culture 2/2 GM – PCR 2/ 2 |

GM 1/9 BDG 4/8 |

[15] |

| Germany | 5 |

Culture 1/3 GM 3/3 PCR 3/3 |

A. fumigatus (4) |

Culture 2/3 GM ND PCR 1/2 |

GM 2/5 BDG – |

[16] |

| Netherlands | 6 |

Culture 2/3 GM 3/3 PCR – |

A. fumigatus (5) |

Culture 3/3 GM– PCR – |

GM 0/3 BDG – |

[17] |

| Belgium | 6 |

Culture 5/6 GM 5/6 PCR – |

A. fumigatus (5), A. flavus (1) |

Culture – GM– PCR – |

GM 1/5 BDG – |

[18] |

| Italy | 30 |

Culture 19/30 GM 30/30 PCR 20 /30 |

A. fumigatus (16), A. niger (3), A. flavus (1) |

Culture – GM—PCR – |

GM 1/30 BDG – |

[19] |

| UK | 19 |

Only NBL performed; Denominator not reported |

A. fumigatus (9), A. versicolor (1) | Denominator not reported | Denominator not reported | [20] |

| Belgium | 4 |

Culture 4/4a GM 4/4 PCR 2/2 |

Not specified |

GM – BDG - |

[21] | |

| Switzerland | 3 |

Culture – GM– PCR – |

A. fumigatus (3) |

Culture 3/3 GM – PCR 1/? |

GM 1/? BDG 1/? |

[22] |

| France | 19 |

Culture 7/9 GM 7/9 PCR – |

A. fumigatus (14), A. calidoustus (1), A. niger (1) |

Culture 9/10 GM– PCR – |

GM 1/12 BDG – |

[23] |

| Pakistan | 5 | Not specified | A. fumigatus (1), A. flavus (4), A. niger (1) | Not specified |

GM 0/5 BDG 1/5 |

[24] |

| USA | 4 | Not specified | A. fumigatus (4) | Not specified |

GM 1/3 BDG – |

[25] |

| France | 7 |

Culture not specified/5 GM 3/5 PCR 2/5 |

A. fumigatus (5) | Not specified |

GM 1/7 BDG 2/7 |

[26] |

| Netherlands | 8 |

Culture 7/7 GM 2/6 PCR 4/5 |

A. fumigatus (7) |

Culture 1/1 GM 1/1 PCR 1/1 |

GM 0/1 | [27] |

| Netherlands | 11 |

Culture 5/40 GM 11/37 PCR 11/40 |

A. fumigatus (3) |

Culture 3/47 GM not performed PCR 23/30 |

GM 0/11 | [28] |

| USA | 20 |

Culture 2/20 GM 2/20 PCR not specified |

Not specified | Not specified |

GM 8/20 BDG 6/20 |

[29] |

BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; GM: galactomannan; BDG: beta-D-glucan; PCR: polymerase chain reaction

aBAL and BA were not distinguished

According to a recent case series involving 186 CAPA cases, GM levels were positive (i.e., GM index ≥ 1.0) in respiratory samples from 113 (60.8%) patients, including BAL samples from 63 (33.9%) patients and NBL from 22 (11.8%) [4]. Furthermore, GM was detected in serum or plasma from 29 (15.6%) CAPA patients. The performance of LFD tests has been studied in ICU patients [30], showing a good overall test performance (sensitivity 0.88–0.94, specificity 0.81, and the area under the ROC curve 0.90–0.94) [30]. AspLFD (OLM Diagnostics) was used in 8 CAPA cases using one TA and seven BAL samples [27]. The AspLFD was positive in six patients but did not correspond with GM detection in four. Another study compared the performance of the Sona Aspergillus Galactomannan Lateral Flow Assay (IMMY) with that of the Platelia Aspergillus in TA obtained from CAPA patients [31]. However, as bronchoscopy was not performed in this study, a reliable classification of CAPA patients was not possible.

Serum biomarkers show a low sensitivity ranging from 0 to 40% for GM and 0–50% for BDG (Table 2). Overall, serum BDG shows a higher sensitivity than serum GM, but is a panfungal marker and thus not specific for CAPA. Furthermore, some studies indicate only a modest contribution of BDG to the diagnosis of invasive fungal disease in critically ill patients due to low sensitivity and positive predictive value [32]. Circulating GM is associated with angioinvasion, and the low number of CAPA patients with positive serum GM may be due to absence of angioinvasion in most patients. Nevertheless, one recent autopsy series reported Aspergillus angioinvasion in lung tissue in three patients, but the results of circulating biomarker detection in these patients was not reported [2].

Imaging CT has been the most important imaging tool in COVID-19 patients. Typical appearance of COVID-19 includes peripheral, bilateral, ground-glass opacities with or without consolidation or visible intralobular lines (i.e. crazy paving) in early stages; multifocal ground-glass opacities of rounded morphology with or without consolidation or crazy paving at peak stage; reverse halo sign as well as other findings of organizing pneumonia at late stages are observed as well [33]. Many signs of COVID-19 pneumonia can mimic CAPA, and vice versa, and lesions suggestive of CAPA may be hidden. Radiological findings that were previously shown to be sufficiently specific to diagnose IPA in immunocompromised patients are the halo sign, air-crescent sign, cavitating lung lesions and well-defined intrapulmonary nodule(s). In ICU patients with influenza, cavitating lung lesions and well-described nodule(s) are also considered a useful diagnostic sign. In a recent case series of 20 patients with probable CAPA from North-America, nine (45%) presented with cavitary lung lesions [29]. Whether or not, any of these criteria can help in distinguishing Aspergillus colonization from infection in COVID-19 patients is as yet uncertain. Indeed, an intrinsic part of severe COVID-19 is intravascular thrombosis due to endotheliopathy, which can result in infarction and cavitating lesions as well as the halo sign [5, 11]. Therefore, even though CT can reliably ascribe intravascular lesions to venous thrombosis, the role of imaging as a reliable criterion for diagnosing CAPA is probably limited. Importantly, CT may contribute to identifying other reasons for respiratory deterioration. Nevertheless, for critically ill COVID-19 patients, new nodules with cavitation or halo sign, or consolidations have been recommended to trigger a diagnostic work-up for CAPA [34]. Histopathological data of a sufficient number of patients with these radiological findings present in the days preceding death are needed to improve our understanding of the radiology of CAPA.

What is the reported prevalence of Aspergillus pneumonia in patients with COVID-19?

Evidence summary

With the limitations described above regarding the published definitions of CAPA in mind, the reported frequencies of CAPA can be found in Table 3. Overall, 15 CAPA case series in the ICU reported 158 CAPA cases among 1702 COVID-19 patients (9.3%, range between 0 and 33%). Only in four cases CAPA was proven, while the majority had a probable or putative diagnosis. Cohort studies report that most ICU patients who were diagnosed with CAPA were mechanically ventilated, although this may be explained by the fact that diagnostic procedures like BAL are rarely performed in non-ventilated patients with COVID-19. Furthermore, most patients developed CAPA on average between day 4 and 11 after ICU admission. However, as many studies relied on a diagnostic work-up in deteriorating patients or in those with positive upper respiratory cultures, the true prevalence and timing of CAPA remains undefined. The study of Bartoletti is the only study that involved routine bronchoscopy on day 0 and 7 of ICU admission indicated that a high number of patients (14 of 108) was BAL GM positive (GM index > 1) at ICU admission [19].

Table 3.

Reported characteristics of cohort studies of CAPA in ICU patients that utilized bronchoscopy

| Country | Case definition | CAPA prevalence | Time to first Asp. positive sample after ICU admission in days (range)a | Ventilated | Proven/probable/putative | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | EORTC/MSGERC (if immunocompromised) [7] and IAPA [5] | 9/27 (33%) | Not specified | 27/27 | 0/1/8 | [15] |

| Franceb |

Modified IAPA [3] and EORTC/MSGERC [7] |

21/366 (5.7%) | 6 (1 -15) | 246/366 | 0/21/0 | [33] |

| Germany | Modified AspICU [8, 9] | 5/19 (26%) | Not specified | 5/5 | 0/–/5 | [16] |

| Netherlands | Modified IAPA [3] | 6/31 (19%) | 10 (3 – 28) | 6/6 | 0/3/3 | [17] |

| Belgium | AspICU [8] | 6/34 (21%) | 8 (2 – 16) | 6/6 | 4/–/2 | [18] |

| Italy | Modified IAPA [3] | 30/108 (28%) | 4 (2 – 8) daysc (study used screening protocol) | 30/30 | 0/30/– | [19] |

| AspICU [8] | 19/108 (18%) | 8 (0 – 35)d | 19/19 | 0/–/19 | ||

| UK | AspICU [8] | 8/135 (6%) | 7/8 | 0/–/8 | [20] | |

| IAPA [5] | 20/135 (15%) | 15/20 | 0/–/20 | |||

| Own definition | 19/135 (14%) | 14/19 | 0/–/19 | |||

| Belgium | Modified AspICU [8, 9] | 4/131 (3%) | 4 | 4/4 | 0/–/4 | [21] |

| Switzerland | Modified IAPA [3] | 3/80 (4%)¥ | 6 (3–8) | 3/3 | 0/1/2 | [22] |

| France | Modified AspICU [8, 9] | 19/106 (18%) | 11 (2–23) | 18/19 | 0/–/19 | [23] |

| France | EORTC/MSGERC (if immunocompromised) [7] and IAPA [5] | 7/145 (5%) | 10 (median) | 27/27 | 0/0/7 | [24] |

| Ireland | Not stated | 0/55 | – | Not stated | 0/0/0 | [36] |

| Netherlands | 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus definitions [10] | 7/33 (21%) | Not specified | Not specified | 0/7/– | [27] |

| Netherlands | 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus definitions [10] | 11/63 (17%) | 21 (13–27) | 10/11 | 0/11/– | [28] |

| USA | 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus definitions [10] | 20/396 (5%) | 13 (8.5–28) | 20/20 | 0/20/19e | [29] |

aTime to positivity: Antinori et al. culture sample taken at day 4 positive [37]. Ghelfenstein-Ferreira et al. culture positive with A. fumigatus of sample taken at day 6 after ICU admission [38]. Meijer et al. recovered A. fumigatus from a tracheal aspirate culture at ICU admission [39]. Mitaka et al. found that the 6 patients were mechanically ventilated for a mean of 6.8 days (range 1–14 days) before Aspergillus isolation [25]. The two patients described by Helleberg had growth of A. fumigatus in respiratory samples 1 and 5 days after starting mechanical ventilation [40]

bIncludes cohort of Alanio et al. [15]

c80 mechanical ventilated patients of a total of 118 patients admitted to the ICU

dOf 16 patients with multiple Aspergillus cultures positive

e19 possible CAPA cases according to their own classification [29]

What are the host-/risk factors that are associated with COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA)?

Evidence summary

Case series published to date show that only a minority of patients have traditional EORTC/MSGERC host factors (Table S1). Five patients (3%) were reported with a hematological malignancy, two (1.3%) with other malignancies and five (3%) with solid organ transplantation. One study identified the presence of an EORTC/MSGERC host factor as significant risk for invasive fungal infection [26]. Four cohort studies have identified risk factors for CAPA. Long-term steroid treatment (at dosages higher than or equivalent to prednisone 16 mg/day for at least 15 days) was found to be significantly more frequent in patients with CAPA compared to those without CAPA [19]. The use of high-dose corticosteroids (dose not defined) and the presence of chronic lung disease were associated with multiple positive Aspergillus tests in another study [19]. A third cohort found that corticosteroids administered at any dose for > 3 weeks was a risk factor for invasive fungal infection, and a fourth study showed a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving hydrocortisone during admission in the patients with CAPA compared to patients without CAPA (50% versus 12.8%; p < 0.001) [26, 29]. Finally, a fifth study did not find a statistically significant association of high-dose corticosteroid therapy with CAPA risk (11.5% versus 28.6%; p = 0.08), but observed cumulative dose ≥ 100 mg to be higher among CAPA patients [35].

All but a few of the reports on CAPA come from a setting where corticosteroid therapy was not yet the standard of care but rather the exception. Since the publication of the RECOVERY trial, corticosteroid therapy has become the standard of care for all patients admitted with severe COVID-19 [41]. Therefore, the data regarding the impact as well as the magnitude of the impact of corticosteroid use on the incidence of CAPA should be considered preliminary. The question remains if a certain cumulative dose and if a 10-day regimen of dexamethasone, as was used in the RECOVERY trial and has become the standard of care, poses the patient at increased risk for CAPA.

Is antifungal therapy indicated in patients suspected of CAPA?

| Recommendations | Strength of recommendation | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Antifungal therapy is indicated in patients with CAPA | Strong | Low |

| We recommend to follow national or international guidelines on antifungal therapy of invasive aspergillosis | Strong | Low |

| We recommend to consider empirical therapy for CAPA in patients in who(m) a BAL has been performed and BAL GM/PCR results are pending | Weak | Very low |

| In patients with a negative BAL GM, discontinuation of empirical antifungal therapy is recommended | Weak | Very low |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is recommended in critically ill CAPA patients receiving triazole therapy | Strong | Low |

Evidence summary

Despite the difficulty in distinguishing between Aspergillus colonization and invasive disease, studies have shown excess mortality in Aspergillus positive COVID-19 patients in the ICU, but the difference was not always statistically significant (Table 4). In the study of Bartoletti et al., of the 30 CAPA patients, 16 received antifungal therapy of whom 13 received voriconazole [19]. Fourteen patients did not receive antifungal therapy due to post-mortem diagnosis (7 patients) or due to clinical decision (7 patients). Survival of patients treated with voriconazole was 54% (7 of 13), and for those not receiving voriconazole 41% (7 of 17) (p = 0.39) [19]. A relationship between initial BAL GM index and 30-day survival was noted. The odds of death within 30 days of ICU admission increased 1.41-fold (1.10–1.81; p = 0.007) for each point increase in the initial BAL GM index [19]. In the study of White et al., all-cause mortality rates ranged from 46.7% (95% CI 24.8–69.9) in CAPA patients receiving appropriate antifungal therapy to 100% (95% CI 51.1–100) in patients not receiving appropriate antifungal therapy [20]. Van Biesen et al. found a mortality of 22.2% in patients with CAPA based on NBL and 15.1% in patients without CAPA [42]. In the study of Dupont, 3 of 9 (33%) of antifungal-treated patients compared to 5 of 10 (50%) untreated patients died at day 42 [23].

Table 4.

All-cause mortality in COVID-19 patients with CAPA compared with controls

| Country | Case definition | # of CAPA patients | Mortality in CAPA | Mortality in controls | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | EORTC/MSGERC (if immunocompromised) [7] and IAPA [5] | 9 | 44% | 39% (p = 0.99) | [15] |

| Francea | Modified IAPA [8, 9] and EORTC/MSGERC [7] | 21 | 71.4% | 36.8% (p < 0.01) | [35] |

| Italy | IAPA [5] | 30 | 44% (day 30) | 19% (day 30) (p = 0.002)b | [19] |

| AspICU [8] | 19 | 74% | 26% ( p < 0.001) | ||

| United Kingdom | 19 | 58% (day 77?) | 38% | [20] | |

| Netherlands | 2020 ECMM/ISHAM [10] | 19 | 63.6% | 23.1% ( p = 0.013) | [28] |

| USA | 2020 ECMM/ISHAM [10] | 20 | 50% | 41.5% | [29] |

aIncludes cohort of Alanio et al. [15]

bDiagnosis of CAPA was associated with 30-day mortality from ICU admission (OR 3.53; 95% CI 1.29–9.67; p = 0.014), even after adjustment for age (OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.94–1.06; p = 0.99), need for renal replacement therapy (OR 3.02; 95% CI 1.11–8.19; p = 0.015), and SOFA score at ICU admission (OR 1.38; 95% CI 1.07–1.73; p = 0.004) with a logistic regression model [19]

Patients diagnosed with CAPA have been reported to survive without receiving antifungal therapy. As indicated above, 7 of 17 (41%) CAPA patients who were not treated with voriconazole survived in the case series reported by Bartoletti et al. [19] Alanio and colleagues described 7 patients with putative (6) or probable (1) CAPA who did not receive antifungal therapy, of whom 5 survived [15]. Survival may be due to various factors, including absence of invasive disease (i.e. colonization). Indeed, in one study tissue biopsies showed no evidence for CAPA, despite most patients being classified as probable cases [43]. These observations might imply that in some critically ill COVID-19 patients positive Aspergillus tests reflect colonization rather than invasive disease. Importantly, the prognostic impact of Aspergillus colonization in severe COVID-19 pneumonia is yet to be established. Furthermore, baseline mortality of severe COVID-19 may vary between studies as new treatment modalities continue to evolve. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved remdesivir and baricitibinib for treatment of COVID-19, but their role in critically ill patients remains unclear. Further discussions of treatment of COVID-19 were beyond the scope of the taskforce.

Azole resistance Five cases of azole-resistant CAPA have been reported [27, 38, 39, 44]. In four cases the TR34/L98H resistance mutation was detected and in one case a TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation, which are associated with environmental resistance selection. There are currently no indications that the risk for azole-resistant infection differs from that in other ICU patients. In regions with levels of azole resistance exceeding 10%, it was recommended to cover resistance in initial antifungal therapy by adding an echinocandin to voriconazole or isavuconazole or by treating with liposomal amphotericin B [45]. When azole resistance is detected liposomal amphotericin B is recommended [11, 45], while the use of deoxycholate-amphotericin B in the ICU-setting is discouraged [45].

There are no studies that investigate the optimal choice and duration of antifungal therapy of CAPA. We therefore refer to international or national invasive mycoses guidelines for primary treatment choices [45, 46]. Most guidelines recommend voriconazole or isavuconazole as a first line treatment option. Recently, posaconazole was shown to be non-inferior to voriconazole for the treatment of IPA [47]. The experience with isavuconazole and posaconazole in ICU patients with IPA is still limited.

Pharmacologic considerations Monitoring of exposure to ensure adequate exposure by means of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and is an important component in triazole treatment of patients with CAPA. Critical illness with (multi) organ failure predisposes patients to a high degree of variability in drug exposure. This is further complicated by factors such as drug-drug interactions, alterations in protein binding, use of vasopressor agents impacting organ perfusion and the frequent use of renal replacement techniques as well as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

Pharmacokinetic interactions are most likely the biggest source of pharmacokinetic variability in exposure. Clinicians should make a thorough assessment of these interactions and consult a pharmacologist where needed to aid in this matter. A useful resource to recommend is the website on COVID drug interactions that includes reference to the antifungal drugs. (available at https://www.covid19-druginteractions.org/).

In addition to pharmacokinetic interactions, pharmacodynamic interactions may be relevant. Pharmacodynamic interactions occur when the pharmacological effect of the victim drug is altered by coadministration of the antifungal drug. Clinically relevant side effects are often off-target effects. Examples are interactions between (lipid) formulations of amphotericin B and nephrotoxic drugs resulting in loss of kidney function, potassium wasting agents and liposomal amphotericin B as well as posaconazole, and many others. Patients with pre-existing QT-prolongation as well as those with severe electrolyte disturbances may be more prone to ventricular arrhythmias when treated with triazoles. Isavuconazole might be the preferred triazole, as this drug is not associated with further disturbances of electrolytes and shortens rather than prolongs the QT interval.

For many antifungal drugs there are reports of low exposure in patients receiving ECMO. However, ECMO-associated pharmacokinetic changes are generally superimposed with extreme physiological derangements associated with critical illness, making empiric dosage adjustments without TDM difficult [48, 49]. It is furthermore unclear if volumes of distribution are impacted due to adhesion to the circuitry system or that clearance is increased. Recently, ECMO did not appear to influence posaconazole exposure [50]. An overview of triazole pharmacokinetic considerations in ICU patients is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Pharmacokinetic considerations for using triazole antifungals for CAPA

| Pharmacokinetic | Clinical manifestation | Recommendations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical illness (sepsis, altered fluid balance, altered protein binding/hypo-albuminemia, inflammation) | Voriconazole exposures unpredictable in critically ill patients; both low exposures with poor clinical outcomes and elevated exposures increased CNS toxicity are reported especially in the setting of systemic inflammation (0.015 mg/L increase in voriconazole Cmin for every 1 mg/L increase in C-reactive protein) |

TDM to confirm adequate voriconazole drug exposuresa Fewer data in critically ill for isavuconazole but TDM could still be considered |

[51–53] |

| Obesity | Increased Vd and CL of posaconazole, decreased serum drug exposures | Voriconazole dose based on adjusted body weight; no adjustment of fixed isavuconazole dose recommended. Posaconazole exposures reduced in obese patients | [54–56] |

| Renal replacement therapy | No effect on voriconazole or isavuconazole pharmacokinetics, sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin in IV voriconazole formulation is removed by CRRT at rate similar to ultrafiltration rate | TDM of voriconazole recommended even though voriconazole is not cleared by RRT | [57, 58] |

| ECMO | Initial voriconazole doses are extracted into ECMO circuit; once circuit is saturated “redosing” of patient can occur; limited data with isavuconazole suggested exposures may be reduced by 50% | Patients at risk of voriconazole and isavuconazole underdosing at initiation of ECMO, overdosing of voriconazole at discontinuation. Limited data for isavuconazole Routine TDM-guided dosing essential for voriconazole and may be indicated for isavuconazole | [48, 49] |

| Drug-interactions | Dexamethasone, methylprednisolone | Limited evidence that corticosteroids reduce voriconazole exposure, TDM-adjusted dosing indicated | [59] |

aVoriconazole Cmin of 1–6 mg/L2 Cmean 2.98 ± 1.09 mg/L

How should invasive Aspergillus tracheobronchitis be managed in CAPA patients?

| Recommendation | Strength of recommendation | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with visible plaques in trachea and bronchi should undergo mucosal biopsy or brush to diagnose IATB | Strong | Low |

Evidence summary

IATB was found to be a frequent and highly lethal manifestation of IAPA [60]. Autopsy studies indicate that focal white patches may be present in the trachea and large bronchi of 92% of COVID-19 patients [61]. This is likely to be due to viral tropism as the epithelium of the conducting airways was shown to support the replication of SARS-CoV-2 and to express ACE-2 receptor [62]. Local epithelial damage may provide a portal of entry for Aspergillus to cause invasive airway disease. Pseudomembranous plaques or ulcers were visible in 6 of 30 (20%) patients with CAPA [19], and bronchial ulcers reported in two of 8 Aspergillus positive COVID-19 patients, but the patients in the latter study were not classified according to published definitions [63]. These data indicate that the frequency of IATB in CAPA is probably lower than observed in IAPA [5]. However, the diagnosis of IATB is made through visualization of plaques in the airways, and since the use of bronchoscopy has been restricted, tracheobronchitis cases may be underreported.

The mortality associated with IATB is unknown in CAPA but was reported to be as high as 90% in IAPA patients [60]. Systemic antifungal therapy alone might not be sufficient to effectively treat this disease manifestation due to intraluminal growth of the fungus. Inhaled (liposomal) amphotericin B has been recommended by the IDSA as adjunctive therapy in these cases [46]. To date only one IAPA patient with IATB was reported to be treated with nebulized liposomal amphotericin B in addition to systemic antifungal therapy [64].

What is the role of immunomodulating agents in the management of CAPA in ICU patients?

| Recommendations | Strength of recommendation | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| We recommend not to stop concomitant dexamethasone or corticosteroid therapy in CAPA patients | Weak | Very low |

Evidence summary

Corticosteroids in influenza and other coronavirus respiratory syndromes have shown no benefit or possible harm [65, 66]. Early consensus was against corticosteroids in COVID-19 [67]. During the pandemic the RECOVERY trial, a meta-analysis of steroid trials by the WHO, and the REMAP-CAP trial have changed practice by showing benefit of corticosteroids in COVID-19 patients in the ICU [41, 68, 69]. RECOVERY reported that in over 6000 patients the administration of 6 mg dexamethasone for ten days was associated with significantly reduced 28-day mortality [41]. This result was most pronounced among patients requiring mechanical ventilation (rate ratio 0.65, 95% CI 0.48–0.88, p = 0.0003) and immediately changed clinical practice. The question arose whether there would be additive effects of other immunomodulatory drugs in addition of corticosteroids. Recently, REMAP-CAP showed that in an ICU population blocking the IL-6 pathway with tocilizumab or sarilumab could further reduce mortality and organ free support days in the ICU when started within 24 h of admission to the ICU [70]. Median organ support-free days were 10 (interquartile range [IQR] − 1, 16), 11 (IQR 0, 16) and 0 (IQR − 1, 15) for tocilizumab, sarilumab and control, respectively. Hospital mortality was 28% (98/350) for tocilizumab, 22.2% (10/45) for sarilumab and 35.8% (142/397) for control. More recently, an improved overall survival in patients receiving tocilizumab in addition of dexamethasone was confirmed in the RECOVERY trial as well [71]. Again, similar to corticosteroids there were no reports of increased adverse events, including secondary infections during treatment [41, 65, 68, 70]. However, no CAPA-related diagnostic strategy were implemented in these trials and at 0.1%, the extremely low incidence of infection as the cause of death in the tocilizumab arm of the RECOVERY trial suggests that the registration of this adverse event may have been suboptimal.

Immune-modulation has thus become a cornerstone of treatment of COVID-19 in the ICU, and current practice will include combinations of corticosteroids and blocking IL-6 in some critically ill patients. Although there is no evidence for increased frequency of IPA among patients receiving immunotherapy compared to no immunotherapy, the difficulty of diagnosing CAPA and the fact that registrations of fungal infection complications are not optimal do not allow us to fully understand the impact of immune-modulating agents on CAPA rates. Future randomized clinical trials should include specific registration of secondary infections such as CAPA to assess the impact of immunomodulation on this patient population. The risk factors identified for CAPA thus far do include corticosteroids and the population with the highest CAPA incidence was a study where over 70% of patients had received tocilizumab [19]. The cytokine IL-6 which signals via STAT3 is crucial for T helper (Th)17 development and Th17 responses are important for protective anti-Aspergillus host responses [72–74]. Clinicians should be aware that CAPA as a complication of COVID-19 in ICU might increase with these new immunosuppressive strategies since they also suppress crucial antifungal host defense pathways. However, dampening the immune response has been shown to benefit critically ill COVID-19 and may subsequently reduce the risk for IPA by limiting damage to the epithelium, endothelium and the tissue. Therefore, when CAPA is diagnosed we do not have data which support stopping or continuing dexamethasone or other immune modulatory agents in the context of risk for CAPA, however these immunomodulatory treatments do reduce the overall mortality in the population at risk for CAPA.

Pathophysiology of CAPA

It is becoming apparent that CAPA is a complex disease, which involves a continuum of Aspergillus respiratory tract colonization, tissue invasion and angioinvasion. The limited histopathological data on CAPA available so far show both tissue invasion and angioinvasion [3, 75], but the low number of patients with circulating GM may indicate that angioinvasion is less frequent than observed in IAPA [75]. Angioinvasion is the hallmark pathologic feature of IPA and is associated with circulating GM. Recently, an angioinvasion threshold model was presented in which a combination of determinants was suggested to contribute to Aspergillus reaching the angioinvasion threshold. These determinants involve predisposing factors, such as EORTC/MSGERC host factors and comorbidities, lytic effects on host cells caused by SARS-CoV-2, immune dysregulation, including both hyperinflammation and immune paralysis, and concomitant therapy, such as corticosteroids. These factors together determine if and when Aspergillus infection progresses to cause angioinvasive growth. While this threshold is reached early on in patients with IAPA (corresponding with serum GM positivity in 65–90% of IAPA patients) [4, 60], infrequent serum GM positivity in CAPA patients (between 0 and 50%) indicates that angioinvasion is less frequent. One study showed that mortality in serum GM positive CAPA patients was > 80% compared to 37% in GM negative CAPA patients, which suggests that this marker can be used to stage CAPA infection personal communication, paper submitted for peer-reviewing. There is, however, a need for a marker that is specific for tissue invasion and can discriminate from Aspergillus respiratory tract colonization.

Discussion

Bronchoscopy with BAL remains the cornerstone of CAPA diagnosis. Bronchoscopy allows visual inspection of the airways and thus enables the diagnosis of IATB. In addition to diagnosing CAPA and other respiratory infections, BAL may also be useful to exclude CAPA in patients that require corticosteroid therapy, for instance for the treatment of COP or the prevention of pulmonary fibrosis. In comparison with previous recommendations [11, 34], the use of bronchoscopy has been shown to be a safe procedure in critically ill COVID-19 patients [76]], and thus simplifies the management algorithm.

Positive BA/TA Aspergillus culture or any unexplained respiratory deterioration in critically ill COVID-19 patients are considered triggers to perform a bronchoscopy and BAL (management algorithm). The implications of positive Aspergillus test results for starting antifungal therapy will depend on the institutional incidence of CAPA and the clinical condition of the patient.

The need to administer corticosteroids for the treatment of COVID-19 and the associated risk for CAPA, present a dilemma in the management of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Although the decision to continue corticosteroids in critically ill patients who develop CAPA needs to be assessed on an individual patient basis, we believe that dexamethasone therapy should be continued for the recommended time frame, if possible. Stopping dexamethasone could be considered, e.g. when there is no clear hyperinflammation anymore, when it has been given for 10 days, and/or when there is angioinvasive CAPA or secondary bacterial infections such as S. aureus pneumonia. This also applies to patients who are treated with high-dose corticosteroid therapy for pulmonary fibroproliferation during ICU stay and develop CAPA. Discontinuation or tapering of corticosteroids could be considered in patients who do not respond to antifungal therapy or with underlying EORTC/MSGERC host factors, although this is not supported by clinical data.

Although excess mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients with CAPA justifies pro-active diagnostic assessment and antifungal therapy, many questions remained unanswered (Table 6). These questions need to be addressed in future trials to further fine-tune integrated and targeted CAPA management.

Table 6.

Research agenda in CAPA

| Epidemiology |

Determine the true epidemiology of CAPA Frequency of IATB in CAPA Identification of host/risk factors |

| Diagnosis |

Markers that discriminate between Aspergillus respiratory tract colonization and tissue invasion Validation of Aspergillus biomarkers in NBL and BA/TA Determine the immune status of the host (e.g. FACS) |

| Strategy |

Role for antifungal prophylaxis Management of COVID-19 patients with positive upper respiratory tract culture |

| Antifungal agents |

Benefit of nebulized antifungals in IATB Role of liposomal amphotericin B in the ICU-setting Effect of sequestration and drug interactions of antifungals on exposure (i.e. ECMO; CRRT) |

| Therapy |

Implications of antiviral and host-directed therapy for CAPA risk and outcome Host directed therapy: dampening or boosting immune response or both, dependent on host immune status |

Management algorithm

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

IM-L initiated the idea and coordinated the work with PEV. PEV, JBB, RJMB, and FvdV performed the literature search. PEV and IM-L wrote the first draft, BJAR and PEV constructed the flow chart. All authors participated in critical review and revisions, and grading of the recommendations. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was involved in the guideline development.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

PE Verweij reported grants from Gilead Sciences, MSD, Pfizer, Mundipharma, ThermoFisher, and F2G, and non-financial support from OLM and IMMY, outside the submitted work. All contracts were through Radboudumc, and all payments were invoiced by Radboudumc. RJM Brüggemann served as consultant to Astellas Pharma, Inc., F2G, Amplyx, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., and Pfizer, Inc., and has received unrestricted and research grants from Astellas Pharma, Inc., Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., and Pfizer, Inc. All contracts were through Radboudumc, and all payments were invoiced by Radboudumc. E Azoulay has received fees for lectures from Pfizer, Gilead, MSD, Alexion and Baxter. His institution received research support from Fisher&Payckle, Jazz pharma and Gilead. M Bassetti has received funding for scientific advisory boards, travel and speaker honoraria from Angelini, Astellas, Bayer, BioMèrieux, Cidara, Correvio, Menarini, MSD, Nabriva, Pfizer, Roche and Shionogi. S Blot received research funding from Pfizer and MSD, travel support from Pfizer, MSD, and Gilead, and invited speaker for Pfizer and Gilead. J.B. Buil T Calandra reported advisory board membership from Astellas, Basilea, Cidara, MSD, Sobi, ThermoFisher, and GE Healthcare and data monitoring board membership from Novartis, all outside the submitted work. Fees are paid to its institution. T Chiller reported no conflicts of interest. CJ Clancy has been awarded investigator-initiated research grants from Astellas, Merck, Melinta, and Cidara for projects unrelated to this project, served on advisory boards or consulted for Astellas, Merck, the Medicines Company, Cidara, Scynexis, Shionogi, Qpex and Needham & Company, and spoken at symposia sponsored by Merck and T2Biosystems. OA Cornely is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education and the European Commission, and has received research grants from, is an advisor to, or received lecture honoraria from Actelion, Allecra Therapeutics, Amplyx, Astellas, Basilea, Biosys UK Limited, Cidara, Da Volterra, Entasis, F2G, Gilead, Grupo Biotoscana, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Matinas, Medicines Company, MedPace, Melinta Therapeutics, Menarini Ricerche, Merck/MSD, Octapharma, Paratek Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, PSI, Rempex, Scynexis, Seres Therapeutics, Tetraphase, Vical. P Depuydt reported no conflicts of interest. P Koehler is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education and the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany and has received non-financial scientific grants from Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, and the Cologne Excellence Cluster on Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany, and received lecture honoraria from and/or is advisor to Akademie für Infektionsmedizin e.V., Ambu GmbH, Astellas Pharma, European Confederation of Medical Mycology, Gilead Sciences, GPR Academy Ruesselsheim, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Noxxon N.V., and University Hospital, LMU Munich outside the submitted work. K Lagrou received consultancy fees from MSD, SMB Laboratories Brussels and Gilead Sciences, travel support from Pfizer, grant from Thermo Fisher Scientific and speaker fees from Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, and FUJIFILM WAKO. D de Lange C Lass-Flörl received research funding from Pfizer, Gilead and Egger, travel support from Pfizer, MSD, and Gilead, and has served as invited speaker for MSD, Pfizer, Gilead, Basilea and Angelini. RE Lewis has received research support from Merck, and has served an invited speaker for Gilead, Cidara. O Lortholary has served as an invited speaker for Gilead, MSD, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, and is a consultant for Gilead, Novartis and F2G. P Wei-Lun Liu has received research grants from MSD, Pfizer, and has served as an invited speaker for Gilead, MSD, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, and is an advisor to Pfizer, Gilead. J Maertens reported personal fees and non-financial support from Basilea Pharmaceuticals, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Cidara, F2G Ltd, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Astellas, Scynexis, and Pfizer Inc. and grants from Gilead Sciences, IMMY and OLM. MH Nguyen receives research grants from the National Institute of Health, Astellas, Pulmocide, Scynexis,and Mayne, and participates in clinical trials funded by the Mycosis Study Group and F2G. TF Patterson received research grants or clinical trial support to UT Health San Antonio from Cidara and F2G and is an NIH ACTT and ACTIV investigator; is a consultant for Appili, Basilea, F2G Gilead, Mayne, Merck, Pfizer, Scynexis, and Sfunga. B Rijnders was investigator for studies supported by Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag, MSD, Pfizer, ViiV; has received research grants from Gilead and MSD; was invited speaker for Gilead, MSD, Pfizer, Jansen-Cilag, BMS; and advisory board member for BMS, Abbvie, MSD, Gilead, Jansen-Cilag; he received travel support from BMS, Abbvie, MSD, Gilead, Jansen-Cilag. A Rodríguez report research grant from Gilead Science and fees for lectures from Pfizer, Gilead, ThermoFisher, Biomerieux and MSD. J Schouten reported grants from MSD and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. All contracts were through Radboudumc, and all payments were invoiced by Radboudumc. J Wauters reports grants, personal fees and other from MSD, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, outside the submitted work. F van de Veerdonk reports grants from Gilead Sciences, grants from Sobi, outside the submitted work. I Martin-Loeches reported grants from Gilead, MSD and Pfizer, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Paul E. Verweij, Email: paul.verweij@radboudumc.nl

Ignacio Martin-Loeches, Email: drmartinloeches@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Skok K, Vander K, Setaffy L, Kessler HH, Aberle S, Bargfrieder U, Trauner M, Lax SF. COVID-19 autopsies: procedure, technical aspects and cause of fatal course. Experiences from a single-center. Pathol Res Pract. 2021;217:153305. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.153305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evert K, Dienemann T, Brochhausen C, Lunz D, Lubnow M, Ritzka M, Keil F, Trummer M, Scheiter A, Salzberger B, Reischl U, Boor P, Gessner A, Jantsch J, Calvisi DF, Evert M, Schmidt B, Simon M. Autopsy findings after long-term treatment of COVID-19 patients with microbiological correlation. Virchows Arch. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00428-020-03014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schauwvlieghe AFAD, Rijnders BJA, Philips N, Verwijs R, Vanderbeke L, Van Tienen C, Lagrou K, Verweij PE, Van de Veerdonk FL, Gommers D, Spronk P, Bergmans DCJJ, Hoedemaekers A, Andrinopoulou ER, van den Berg CHSB, Juffermans NP, Hodiamont CJ, Vonk AG, Depuydt P, Boelens J, Wauters J, Dutch-Belgian Mycosis study group Invasive aspergillosis in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe influenza: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:782–792. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salmanton-García J, Sprute R, Stemler J, Bartoletti M, Dupont D, Valerio M, Garcia-Vidal C, Falces-Romero I, Machado M, de la Villa S, Schroeder M, Hoyo I, Hanses F, Ferreira-Paim K, Giacobbe DR, Meis JF, Gangneux JP, Rodríguez-Guardado A, Antinori S, Sal E, Malaj X, Seidel D, Cornely OA, Koehler P, FungiScope European Confederation of Medical Mycology/The International Society for Human and Animal Mycology Working Group2 COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis, March-August 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1077–1086. doi: 10.3201/eid2704.204895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verweij PE, Rijnders BJA, Brüggemann RJM, Azoulay E, Bassetti M, Blot S, Calandra T, Clancy CJ, Cornely OA, Chiller T, Depuydt P, Giacobbe DR, Janssen NAF, Kullberg BJ, Lagrou K, Lass-Flörl C, Lewis RE, Liu PW, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Martin-Loeches I, Nguyen MH, Patterson TF, Rogers TR, Schouten JA, Spriet I, Vanderbeke L, Wauters J, van de Veerdonk FL. Review of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients and proposal for a case definition: an expert opinion. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1524–1535. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Jaeschke R, Helfand M, Liberati A, Vist GE, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group Incorporating considerations of resources use into grading recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1170–1173. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39504.506319.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, Clancy CJ, Wingard JR, Lockhart SR, Groll AH, Sorrell TC, Bassetti M, Akan H, Alexander BD, Andes D, Azoulay E, Bialek R, Bradsher RW, Bretagne S, Calandra T, Caliendo AM, Castagnola E, Cruciani M, Cuenca-Estrella M, Decker CF, Desai SR, Fisher B, Harrison T, Heussel CP, Jensen HE, Kibbler CC, Kontoyiannis DP, Kullberg BJ, Lagrou K, Lamoth F, Lehrnbecher T, Loeffler J, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Marchetti O, Marr KA, Masur H, Meis JF, Morrisey CO, Nucci M, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Pagano L, Patterson TF, Perfect JR, Racil Z, Roilides E, Ruhnke M, Prokop CS, Shoham S, Slavin MA, Stevens DA, Thompson GR, Vazquez JA, Viscoli C, Walsh TJ, Warris A, Wheat LJ, White PL, Zaoutis TE, Pappas PG. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European organization for research and treatment of cancer and the mycoses study group education and research consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blot SI, Taccone FS, Van den Abeele AM, Bulpa P, Meersseman W, Brusselaers N, Dimopoulos G, Paiva JA, Misset B, Rello J, Vandewoude K, Vogelaers D, AspICU Study Investigators A clinical algorithm to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:56–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-1978OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder M, Simon M, Katchanov J, Wijaya C, Rohde H, Christner M, Laqmani A, Wichmann D, Fuhrmann V, Kluge S. Does galactomannan testing increase diagnostic accuracy for IPA in the ICU? A prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2016;20:139. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1326-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koehler P, Bassetti M, Chakrabarti A, Chen SCA, Colombo AL, Hoenigl M, Klimko N, Lass-Flörl C, Oladele RO, Vinh DC, Zhu LP, Böll B, Brüggemann R, Gangneux JP, Perfect JR, Patterson TF, Persigehl T, Meis JF, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, White PL, Verweij PE, Cornely OA, European Confederation of Medical Mycology; International Society for Human Animal Mycology; Asia Fungal Working Group; INFOCUS LATAM/ISHAM Working Group; ISHAM Pan Africa Mycology Working Group; European Society for Clinical Microbiology; Infectious Diseases Fungal Infection Study Group; ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients; Interregional Association of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobial Chemotherapy; Medical Mycology Society of Nigeria; Medical Mycology Society of China Medicine Education Association; Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society for Haematology and Medical Oncology; Association of Medical Microbiology; Infectious Disease Canada Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30847-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pritchett MA, Oberg CL, Belanger A, De Cardenas J, Cheng G, Nacheli GC, Franco-Paredes C, Singh J, Toth J, Zgoda M, Folch E. Society for advanced bronchoscopy consensus statement and guidelines for bronchoscopy and airway management amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:1781–1798. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.04.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koehler P, Cornely OA, Kochanek M. Bronchoscopy safety precautions for diagnosing COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis-A simulation study. Mycoses. 2021;64:55–59. doi: 10.1111/myc.13183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lormans P, Blot S, Amerlinck S, Devriendt Y, Dumoulin A. COVID-19 acquisition risk among ICU nursing staff with patient-driven use of aerosol-generating respiratory procedures and optimal use of personal protective equipment. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;63:102993. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alanio A, Delliere S, Fodil S, Bretagne S, Megarbane B. Prevalence of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Resp Med. 2020;8:e48–e49. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30237-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koehler P, Cornely OA, Böttiger BW, Dusse F, Eichenauer DA, Fuchs F, Hallek M, Jung N, Klein F, Persigehl T, Rybniker J, Kochanek M, Böll B, Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2020;63:528–534. doi: 10.1111/myc.13096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Arkel ALE, Rijpstra TA, Belderbos HNA, van Wijngaarden P, Verweij PE, Bentvelsen RG. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2020;202:132–135. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1038LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutsaert L, Steinfort N, Van Hunsel T, Bomans P, Naesens R, Mertes H, Dits H, Van Regenmortel N. COVID-19-associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:71. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00686-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartoletti M, Pascale R, Cricca M, Rinaldi M, Maccaro A, Bussini L, Fornaro G, Tonetti T, Pizzilli G, Francalanci E, Giuntoli L, Rubin A, Moroni A, Ambretti S, Trapani F, Vatamanu O, Ranieri VM, Castelli A, Baiocchi M, Lewis R, Giannella M, Viale P, PREDICO study group Epidemiology of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among COVID-19 intubated patients: a prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White PL, Dhillon R, Cordey A, Hughes H, Faggian F, Soni S, Pandey M, Whitaker H, May A, Morgan M, Wise MP, Healy B, Blyth I, Price JS, Vale L, Posso R, Kronda J, Blackwood A, Rafferty H, Moffitt A, Tsitsopoulou A, Gaur S, Holmes T, Backx M. A national strategy to diagnose COVID-19 associated invasive fungal disease in the ICU. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarrazyn C, Dhaese S, Demey B, Vandecasteele S, Reynders M, Van Praet JT. Incidence, risk factors, timing and outcome of influenza versus Covid-19 associated putative invasive aspergillosis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamoth F, Glampedakis E, Boillat-Blanco N, Oddo M, Pagani JL. Incidence of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1706–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dupont D, Menotti J, Turc J, Miossec C, Wallet F, Richard JC, Argaud L, Paulus S, Wallon M, Ader F, Persat F. Pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Med Mycol. 2021;59:110–114. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasir N, Farooqi J, Mahmood SF, Jabeen K. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) in patients admitted with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: an observational study from Pakistan. Mycoses. 2020;63:766–770. doi: 10.1111/myc.13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitaka H, Perlman DC, Javaid W, Salomon N. Putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19: An observational study from New York City. Mycoses. 2020;63:1368–1372. doi: 10.1111/myc.13185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fekkar A, Lampros A, Mayaux J, Poignon C, Demeret S, Constantin JM, Marcelin AG, Monsel A, Luyt CE, Blaize M. Occurrence of invasive pulmonary fungal infections in patients with severe COVID-19 admitted to the ICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:307–317. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3400OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meijer EFJ, Dofferhoff ASM, Hoiting O, Meis JF. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: a prospective single-center dual case series. Mycoses. 2021;64:457–464. doi: 10.1111/myc.13254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Grootveld R, van Paassen J, de Boer MGJ, Claas ECJ, Kuijper EJ, van der Beek MT, LUMC-COVID-19 Research Group Systematic screening for COVID-19 associated invasive aspergillosis in ICU patients by culture and PCR on tracheal aspirate. Mycoses. 2021;64:641–650. doi: 10.1111/myc.13259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Permpalung N, Chiang TP, Massie AB, Zhang SX, Avery RK, Nematollahi S, Ostrander D, Segev DL, Marr KA. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis in mechanically ventilated patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercier T, Dunbar A, Veldhuizen V, Holtappels M, Schauwvlieghe A, Maertens J, Rijnders B, Wauters J. Point of care aspergillus testing in intensive care patients. Crit Care. 2020;24:642. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03367-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roman-Montes CM, Martinez-Gamboa A, Diaz-Lomelí P, Cervantes-Sanchez A, Rangel-Cordero A, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Ponce-de-Leon A, Gonzalez-Lara MF. Accuracy of galactomannan testing on tracheal aspirates in COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2021;64:364–371. doi: 10.1111/myc.13216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azoulay E, Guigue N, Darmon M, Mokart D, Lemiale V, Kouatchet A, Mayaux J, Vincent F, Nyunga M, Bruneel F, Rabbat A, Bretagne S, Lebert C, Meert AP, Benoit D, Pene F. (1, 3)-beta-D-glucan assay for diagnosing invasive fungal infections in critically ill patients with hematological malignancies. Oncotarget. 2016;7:21484–21495. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang M, Som A, Mendoza DP, Flores EJ, Li MD, Shepard JO, Little BP. Detection of Unsuspected Coronavirus Disease 2019 Cases by Computed Tomography and Retrospective Implementation of the Radiological Society of North America/Society of Thoracic Radiology/American College of Radiology Consensus Guidelines. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35:346–353. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong-James D, Youngs J, Bicanic T, Abdolrasouli A, Denning DW, Johnson E, Mehra V, Pagliuca T, Patel B, Rhodes J, Schelenz S, Shah A, van de Veerdonk FL, Verweij PE, White PL, Fisher MC. Confronting and mitigating the risk of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2002554. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02554-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dellière S, Dudoignon E, Fodil S, Voicu S, Collet M, Oillic PA, Salmona M, Dépret F, Ghelfenstein-Ferreira T, Plaud B, Chousterman B, Bretagne S, Azoulay E, Mebazaa A, Megarbane B, Alanio A. Risk factors associated with COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients: a French multicentric retrospective cohort. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:790.e1–790.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyd S, Martin-Loeches I. Rates of Aspergillus co-infection in COVID patients in ICU not as high as previously reported. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Antinori S, Rech R, Galimberti L, Castelli A, Angeli E, Fossali T, Bernasconi D, Covizzi A, Bonazzetti C, Torre A, Carsana L, Tonello C, Zerbi P, Nebuloni M. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis complicating SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: A diagnostic challenge. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;38:101752. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghelfenstein-Ferreira T, Saade A, Alanio A, Bretagne S, Araujo de Castro R, Hamane S, Azoulay E, Bredin S, Dellière S. Recovery of a triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in respiratory specimen of COVID-19 patient in ICU—a case report. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2021;31:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meijer EFJ, Dofferhoff ASM, Hoiting O, Buil JB, Meis JF. Azole-resistant COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in an immunocompetent host: a case report. J Fungi (Basel) 2020;6:79. doi: 10.3390/jof6020079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helleberg M, Steensen M, Arendrup MC. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:147–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, Staplin N, Brightling C, Ustianowski A, Elmahi E, Prudon B, Green C, Felton T, Chadwick D, Rege K, Fegan C, Chappell LC, Faust SN, Jaki T, Jeffery K, Montgomery A, Rowan K, Juszczak E, Baillie JK, Haynes R, Landray MJ. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Biesen S, Kwa D, Bosman RJ, Juffermans NP. Detection of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in COVID-19 with non-directed bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1171–1173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-2018LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flikweert AW, Grootenboers MJJH, Yick DCY, du Mée AWF, van der Meer NJM, Rettig TCD, Kant MKM. Late histopathologic characteristics of critically ill COVID-19 patients: different phenotypes without evidence of invasive aspergillosis, a case series. J Crit Care. 2020;59:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohamed A, Hassan T, Trzos-Grzybowska M, Thomas J, Quinn A, O'Sullivan M, Griffin A, Rogers TR, Talento AF. Multi-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection: a lethal combination. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2021;31:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, Denning DW, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Lass-Flörl C, Lewis RE, Munoz P, Verweij PE, Warris A, Ader F, Akova M, Arendrup MC, Barnes RA, Beigelman-Aubry C, Blot S, Bouza E, Brüggemann RJM, Buchheidt D, Cadranel J, Castagnola E, Chakrabarti A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Dimopoulos G, Fortun J, Gangneux JP, Garbino J, Heinz WJ, Herbrecht R, Heussel CP, Kibbler CC, Klimko N, Kullberg BJ, Lange C, Lehrnbecher T, Löffler J, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Marchetti O, Meis JF, Pagano L, Ribaud P, Richardson M, Roilides E, Ruhnke M, Sanguinetti M, Sheppard DC, Sinkó J, Skiada A, Vehreschild MJGT, Viscoli C, Cornely OA. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(Suppl 1):e1–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patterson TF, Thompson GR, 3rd, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Nguyen MH, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR, Young JA, Bennett JE. Executive summary: Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:433–442. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maertens JA, Rahav G, Lee DG, Ponce-de-León A, Ramírez Sánchez IC, Klimko N, Sonet A, Haider S, Diego Vélez J, Raad I, Koh LP, Karthaus M, Zhou J, Ben-Ami R, Motyl MR, Han S, Grandhi A, Waskin H, Study investigators Posaconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive aspergillosis: a phase 3, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2021;397:499–509. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spriet I, Annaert P, Meersseman P, Hermans G, Meersseman W, Verbesselt R, Willems L. Pharmacokinetics of caspofungin and voriconazole in critically ill patients during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:767–770. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Y, Seelhammer TG, Barreto EF, Wilson JW. Altered pharmacokinetics and dosing of liposomal amphotericin B and isavuconazole during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pharmacotherapy. 2020;40:89–95. doi: 10.1002/phar.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Daele R, Brüggemann RJ, Dreesen E, Depuydt P, Rijnders B, Cotton F, Fage D, Gijsen M, Van Zwam K, Debaveye Y, Wauters J, Spriet I. Pharmacokinetics and target attainment of intravenous posaconazole in critically ill patients during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76:1234–1241. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoenigl M, Duettmann W, Raggam RB, Seeber K, Troppan K, Fruhwald S, Prueller F, Wagner J, Valentin T, Zollner-Schwetz I, Wölfler A, Krause R. Potential factors for inadequate voriconazole plasma concentrations in intensive care unit patients and patients with hematological malignancies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3262–3267. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00251-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veringa A, Geling S, Span LF, Vermeulen KM, Zijlstra JG, van der Werf TS, Kosterink JG, Alffenaar JC. Bioavailability of voriconazole in hospitalised patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Encalada Ventura MA, van Wanrooy MJ, Span LF, Rodgers MG, van den Heuvel ER, Uges DR, van der Werf TS, Kosterink JG, Alffenaar JW. Longitudinal analysis of the effect of inflammation on voriconazole trough concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:2727–2731. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02830-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Desai A, Kovanda L, Andes D, Lademacher C, Townsend R, Engelhardt M, Bonate P. No dose adjustment necessary for isavuconazole in obese patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3(suppl_1):1950. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw172.1498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pai MP, Lodise TP. Steady-state plasma pharmacokinetics of oral voriconazole in obese adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2601–2605. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01765-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wasmann RE, Smit C, van Donselaar MH, van Dongen EPA, Wiezer RMJ, Verweij PE, Burger DM, Knibbe CAJ, Brüggemann RJM. Implications for IV posaconazole dosing in the era of obesity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:1006–1013. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Townsend RW, Akhtar S, Alcorn H, Berg JK, Kowalski DL, Mujais S, Desai AV. Phase I trial to investigate the effect of renal impairment on isavuconazole pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:669–678. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiser TH, Fish DN, Aquilante CL, Rower JE, Wempe MF, MacLaren R, Teitelbaum I. Evaluation of sulfobutylether-beta-cyclodextrin (SBECD) accumulation and voriconazole pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy. Crit Care. 2015;19:32. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0753-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dolton MJ, Ray JE, Chen SC, Ng K, Pont LG, McLachlan AJ. Multicenter study of voriconazole pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4793–4799. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00626-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nyga R, Maizel J, Nseir S, Chouaki T, Milic I, Roger PA, Van Grunderbeeck N, Lemyze M, Totet A, Castelain S, Slama M, Dupont H, Sendid B, Zogheib E. Invasive tracheobronchial aspergillosis in critically ill patients with severe influenza. A clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:708–716. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201910-1931OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borczuk AC, Salvatore SP, Seshan SV, Patel SS, Bussel JB, Mostyka M, Elsoukkary S, He B, Del Vecchio C, Fortarezza F, Pezzuto F, Navalesi P, Crisanti A, Fowkes ME, Bryce CH, Calabrese F, Beasley MB. COVID-19 pulmonary pathology: a multi-institutional autopsy cohort from Italy and New York City. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:2156–2168. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jia HP, Look DC, Shi L, Hickey M, Pewe L, Netland J, Farzan M, Wohlford-Lenane C, Perlman S, McCray PB., Jr ACE2 receptor expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection depend on differentiation of human airway epithelia. J Virol. 2005;79:14614–14621. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14614-14621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang J, Yang Q, Zhang P, Sheng J, Zhou J, Qu T. Clinical characteristics of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang, China: a retrospective case series. Crit Care. 2020;24:299. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03046-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boots RJ, Paterson DL, Allworth AM, Faoagali JL. Successful treatment of post-influenza pseudomembranous necrotising bronchial aspergillosis with liposomal amphotericin, inhaled amphotericin B, gamma interferon and GM-CSF. Thorax. 1999;54:1047–1049. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.11.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lansbury LE, Rodrigo C, Leonardi-Bee J, Nguyen-Van-Tam J, Shen Lim W. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of Influenza: an updated Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:e98–e106. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng W, Li Y, Cui L, Chen Y, Shan S, Xiao D, Chen X, Chen Z, Xu A. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid treatment in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:571156. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.571156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395:473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Angus DC, Derde L, Al-Beidh F, Annane D, Arabi Y, Beane A, et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19: the REMAP-CAP COVID-19 corticosteroid domain randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1317–1329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]