Abstract

Objectives

The nutritional status of children with cystic fibrosis (CF) is associated with mortality and morbidity. Intestinal inflammation may contribute to impaired digestion, absorption and nutrient utilization in patients with CF and oral glutathione may reduce inflammation, promoting improved nutritional status in patients with CF.

Methods

The GROW study was a prospective, multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, Phase II clinical trial in pancreatic insufficient patients with CF between the ages of 2–10 years. Patients received reduced glutathione or placebo orally daily for 24 weeks. The primary endpoint was the difference in change in weight-for-age z-scores from baseline through week 24 between treatment groups. Secondary endpoints included other anthropometrics, serum and fecal inflammatory markers in addition to other clinical outcomes.

Results

58 participants completed the study. No significant differences were seen between glutathione (n=30) and placebo (n=28) groups in the 6 month change in weight-for-age z-score (−0.08; 95% CI: −0.22, 0.06; p=0.25); absolute change in weight (kg) (−0.18; 95% CI: −0.55, 0.20; p=0.35); or absolute change in BMI kg/m2 (−0.06; 95% CI: −0.37, 0.25; p=0.69). There were no significant differences in other secondary endpoints. Overall, glutathione was safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

Oral glutathione supplementation did not impact growth or change serum or fecal inflammatory markers in pancreatic insufficient children with CF when compared to placebo. Evaluating the role of oral glutathione in a larger, multicenter study prevents unnecessary increase in the medication burden of people with CF.

Keywords: Inflammation, antioxidant, calprotectin

Introduction

The nutritional status of children with cystic fibrosis (CF) is strongly associated with mortality and morbidity (1, 2). Optimal nutrition in the early years of life can have a positive influence on long-term growth, development and pulmonary function later in life. Despite pancreatic enzyme supplementation, high calorie diets, and supplementation of fat-soluble vitamins, many children with CF fail to achieve optimal growth. In CF, intestinal inflammation and dysbiosis contribute to impaired digestion, absorption, and nutrient utilization (3); intestinal inflammation is an appropriate target of therapies aimed at improving nutrition in CF. Antioxidants have been suggested as supplements to improve nutrition in CF. In two pilot studies, orally administered glutathione improved growth in people with CF (4, 5). These encouraging results led to the current study, designed to test the hypothesis that oral glutathione would increase weight gain in children with CF. Additionally, this study provides the opportunity to investigate the effects of oral glutathione on other important clinical outcomes such as gastrointestinal symptoms and markers of inflammation.

Methods

The GROW study was a 24-week multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, Phase II clinical trial examining the effects of oral reduced L-glutathione (GSH) on growth in children with CF. The trial was conducted from July 10, 2017 to December 12, 2018 at 18 accredited CF centers in the United States. It was coordinated by the CF Foundation Therapeutics Development Network Coordinating Center (TDNCC; Seattle; WA) and was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03020719). Institutional review boards at each participating center approved the study.

Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were ≥ 2 and < 11 years of age at enrollment with a confirmed diagnosis of CF, a weight-for-age between the 10th and 50th percentiles, were on a stable dose of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) for management of pancreatic insufficiency, and were clinically stable with no significant changes in health status within the 2 weeks prior to randomization. Exclusion criteria included: intestinal obstruction or gastrointestinal surgery within 6 months prior to enrollment; history of diabetes, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, or bowel resection; recent use of GSH or N-acetyl cysteine; recent initiation of new chronic therapy; recent changes to their amount of dietary supplementation; or recent use of antibiotics (oral, IV, or inhaled).

Study participants were seen at up to four study visits: screening, day 0 (baseline), week 12, and week 24 (Figure, Supplemental digital material (SDC) 2). Screening and baseline visits could be combined. Participants were randomized at baseline to receive either GSH or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. An adaptive randomization algorithm (6) was employed to ensure balance based on the following stratification factors: sex (male, female), baseline age (< 6 years, ≥ 6 years), baseline weight-for-age z-score (< −0.52, ≥ −0.52, i.e., the 30th percentile) and historical fecal elastase (< 200 ug/g, ≥ 200 ug/g, or unavailable).

Anthropometric measures (weight and height), gastrointestinal symptoms, fecal samples (for calprotectin assay), and pulmonary function studies (in participants able to perform spirometry) were obtained at baseline and follow-up visits. Blood was obtained at baseline and week 24 to evaluate changes in blood inflammatory markers. Safety and tolerability were monitored throughout the study.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the difference between treatment groups in 24-week change from baseline in weight-for-age z-score. Secondary endpoints included: change from baseline to week 24 in weight, weight percentile, height, height for-age-z score, height percentile, body mass index (BMI), lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), FEV1 % predicted, forced vital capacity (FVC), or FVC % predicted), blood inflammatory markers (high sensitivity CRP, blood neutrophils, and platelets), and fecal calprotectin, as well as rates of pulmonary exacerbations, differences in the proportion of participants hospitalized or prescribed acute antibiotics, and improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms reported using the Cystic Fibrosis GI Parent Questionnaire (modified from (7)). Participants and/or their parent/guardian completed the questionnaire on gastrointestinal symptoms over the prior three months at the beginning of each visit (Table, SDC 3). Percentiles and z-scores for height and weight were derived using Center for Disease Control reference equations (8). Predicted values for lung function measures were calculated using Global Lung Initiative reference equations (9).

Exploratory Endpoints

At baseline and week 24, plasma samples were obtained to assess potential mechanisms of action and GSH metabolism. Samples were frozen and sent to a central laboratory at Emory University for analysis. Exploratory endpoints included changes between treatment groups in 48 metabolic outcomes of two types: 1) redox metabolites including total glutathione, total cysteine, methionine, methionine sulfone, and methionine sulfoxide; and 2) non-redox metabolites including glucose, lactate, amino acids, biogenic amines, and lipids. These outcomes were assessed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (SDC 4 and 5, processing and metabolites examined).

Glutathione & Placebo Dosing Regimen

L-glutathione reduced, USP (GSH) is a dietary supplement manufactured in accordance with current Good Medical Practice standards for dietary supplements. GSH was supplied as an odorless white crystalline powder with a slightly sour taste. The placebo was lactose monohydrate powder, an odorless white powder. The dose of lactose used (65 mg/kg/day) was too low to result in gastrointestinal symptoms, even for patients with lactose intolerance (10). Each participant received 65 mg/kg/day of either GSH or placebo orally divided into three doses. Each dose was mixed with flavored cherry syrup or a small amount of food immediately prior to administration and given with food. GSH and placebo study drug was packaged in identical high-density polyethylene bottles, labelled “L-Glutathione reduced or Placebo’ to maintain the blind, required FDA warning statement, the protocol number, a bottle number, the name of the sponsors and directions for patient use and storage.

Statistical Analysis

All primary and secondary endpoints were analyzed using the intent-to-treat population, defined as all randomized participants who took at least one dose of study drug. As a sensitivity analysis, the primary endpoint was assessed in the per-protocol population defined as participants with no major protocol violations and participant-reported study drug compliance of > 70%. The primary endpoint was assessed using a linear mixed effects model with unstructured covariance modeling change from baseline to week 12 and week 24, adjusting for randomization strata.

Changes from baseline in anthropometric and lung function parameters and fecal calprotectin were assessed using the same method as described for the primary endpoint. Changes from baseline in neutrophils, platelets, and high-sensitivity C- reactive protein (hs-CRP), were analyzed using analysis of covariance. For each symptom in the GI questionnaire, frequencies and percentages of severity levels (i.e., none, mild, moderate, or severe) and of changes from baseline (i.e., symptoms worsened, symptoms improved, or no change) were summarized across study visits.

Rates of pulmonary exacerbations were evaluated using Poisson regression with logarithm of observation time as an offset to estimate and compare the event rate ratios. Where applicable, Fisher’s exact tests, along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) derived from the Newcombe-Wilson method without continuity correction were reported to compare proportions by treatment group. Exploratory endpoints examining potential GSH mechanisms of action and other metabolites were assessed using two-sided non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests, where applicable. A Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple testing of the 49 included metabolic outcomes.

Safety outcomes were monitored throughout the study by a Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) appointed by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Data Safety Monitoring Board.

Samples size calculations were determined assuming a two-sided 0.05 error rate and a standard deviation for the 24-week change in z-score of 0.4. With 30 participants enrolled in each treatment arm, and allowing for a 10% attrition rate, the study had 90% power to detect a difference in the primary endpoint of 0.36. All testing including p-values and confidence intervals were performed using a two-sided, 0.05 significance level. All differences and ratios were calculated using the placebo arm as the reference group. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) or R version 3.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Recruitment and Follow-up

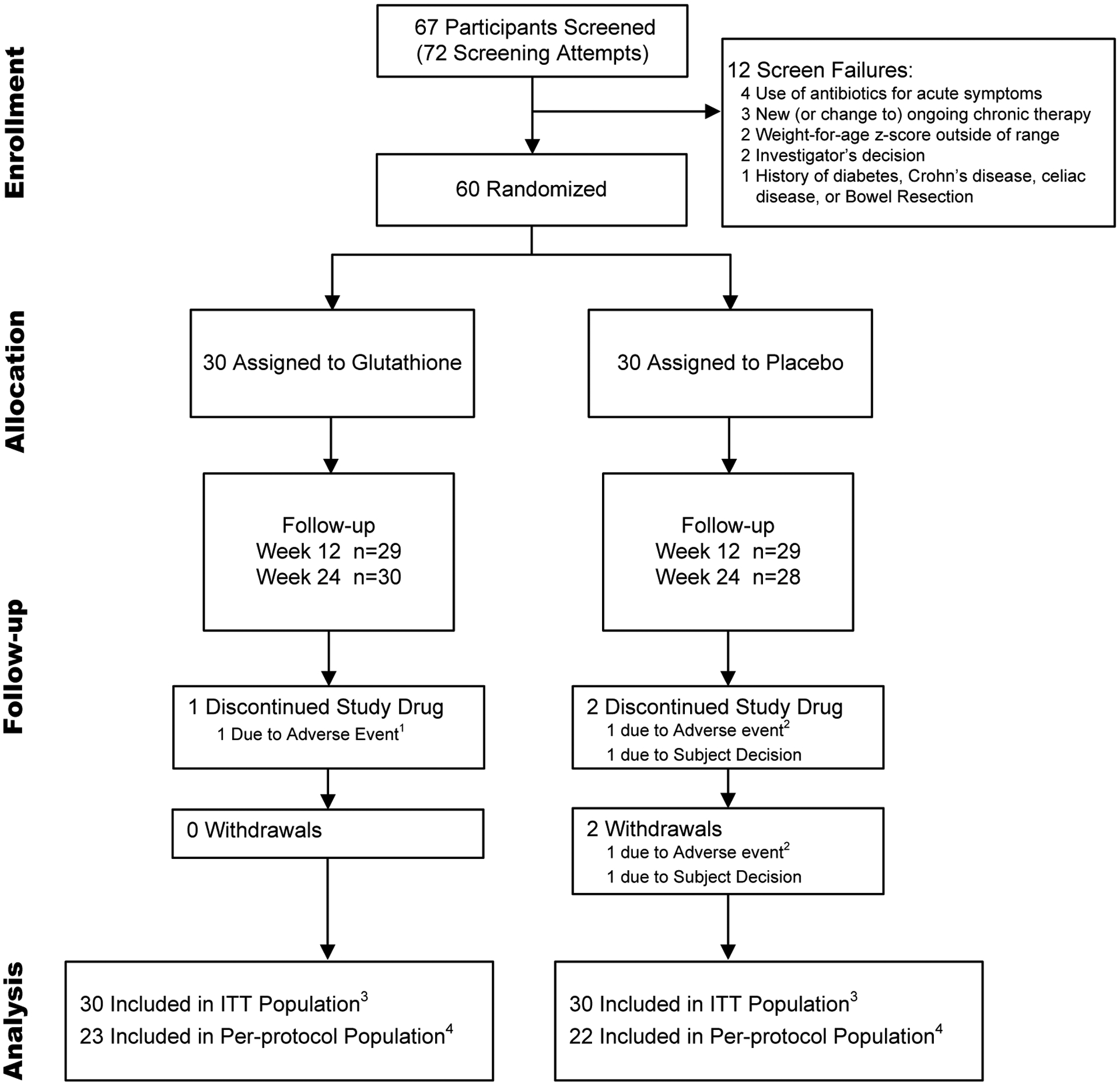

Of 67 screened participants, 60 met eligibility criteria and were randomized: 30 participants to the GSH group and 30 participants to the placebo group (Figure 1). Two participants (<4%), both in the placebo group, withdrew from the study: one participant withdrew due to distal intestinal obstruction, and the other participant decided not to continue in the study. The mean follow-up time was 26.1 weeks per participant in the GSH group and 25.8 weeks per participant in the placebo group.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant enrollment and study completion

1 One participant in the GSH group discontinued study drug due to an adverse event of decreased appetite and weight loss.

2 One participant in the placebo group discontinued study drug and withdrew from the study due to a serious adverse event of distal intestinal obstruction syndrome.

3 Intent-to-treat (ITT) population is defined as all randomized participants who received at least one dose of study drug.

4 Per-protocol population is defined as participants having completed >70% of study drug doses based on participant diary and having incurred no major protocol violations.

The two groups were comparable with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline as shown in Table 1. Overall, 58% were female, 98% were Caucasian, 53% had F508del homozygous genotype; the mean age was 6.1 (standard deviation (SD)=2.6) years (52% <6 years, 48% ≥6 years). Baseline weight-for-age z-scores were similar between treatment groups with a mean of −0.57 (SD=0.33) in the GSH group and −0.53 (SD=0.35) in the placebo group. All 60 participants were pancreatic insufficient as indicated by fecal elastase of < 200 mg/g and medication use was similar between groups.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population at baseline. Continuous measures are summarized by means ± standard deviations, categorical measures are summarized by counts and percentages.

| Characteristic | GSH (N = 30) | Placebo (N = 30) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 6.1±2.4 | 6.0±2.9 |

| Age, no. (%) | ||

| < 6 years | 16 (53) | 15 (50) |

| ≥ 6 years | 14 (47) | 15 (50) |

| Female, no. (%) | 18 (60) | 17 (57) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 29 (97) | 30 (100) |

| Black of African American | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (3) | 3 (10) |

| FEV1, % predicted1 | 96±15 | 98±10 |

| Height, percentile2 | 35±25 | 29±17 |

| Weight, percentile2 | 29±11 | 31±11 |

| BMI, percentile2 | 40±23 | 44±21 |

| Weight, z-score2 | −0.57±0.33 | −0.53±0.35 |

| Genotype, no. (%) | ||

| F508del homozygous | 18 (60) | 14 (47) |

| F508del heterozygous | 9 (30) | 13 (43) |

| Other | 3 (10) | 3 (10) |

| Chronic Medication Use, no. (%) | ||

| CFTR Modulators | 6 (20) | 7 (23) |

| Azithromycin | 4 (13) | 5 (17) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 17 (57) | 12 (40) |

| H2-Blockers | 1 (3) | 4 (13) |

| Dornase Alfa | 26 (87) | 25 (83) |

| Hypertonic Saline | 22 (73) | 21 (70) |

| Appetite Stimulant | 5 (17) | 6 (20) |

| Nutritional Supplements3 | 19 (63) | 21 (70) |

| G-tube, no. (%) | 6 (20) | 2 (7) |

Among those participants able to reproducibly perform spirometry. FEV1 % predicted is calculated using the Global Lung Initiative reference equations.

Percentiles and z-scores are derived using CDC standards.

Nutritional supplements are defined as products providing caloric supplementation and does not include supplements providing only vitamins and/or minerals.

The per-protocol population excluded 15 participants (7 in the GSH group): 10 participants due to major protocol violations (changes in chronic treatment regimen that had the potential to significantly impact weight); five participants due to study drug compliance <70%, and two participants due to missing weight measurements at either baseline or Week 24. Two excluded participants met more than one of the aforementioned criteria.

Study Drug Adherence and Discontinuation

Among the 58 participants with daily diary information available, average adherence for the GSH and placebo groups was 91% and 85%, respectively (difference=5.4%; 95%CI: −3.8%, 14.5%; p=0.25). One participant (3.3%) in the GSH group permanently discontinued study drug as compared to two (6.7%) in the placebo group.

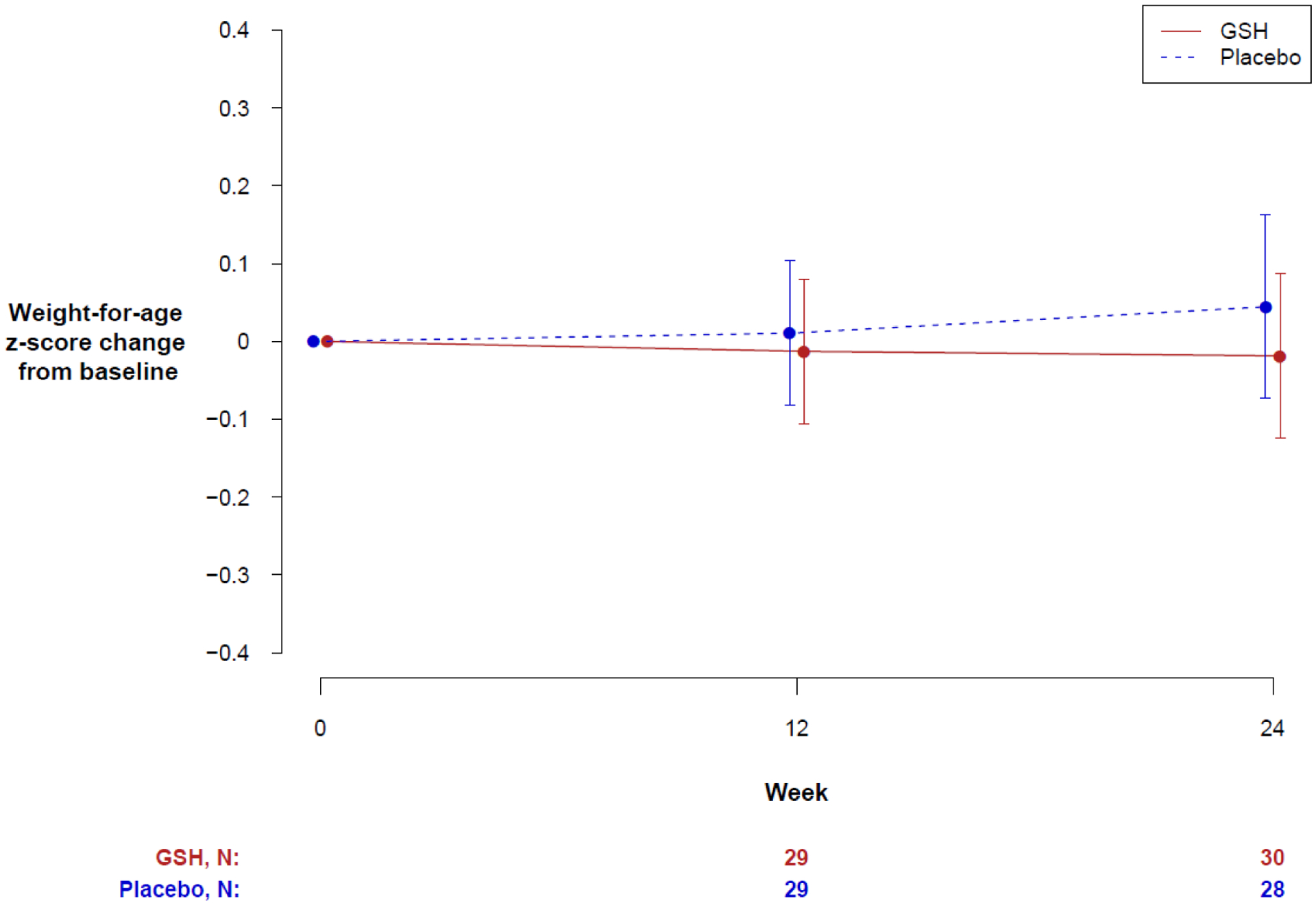

Changes in Weight-for-Age z-score

There was no statistically significant difference in 24-week change from baseline in weight-for-age z-score between GSH and placebo groups (Figure 2). The adjusted model-based estimate of the difference between treatment groups for the 24-week change from baseline in mean weight-for-age z-score was −0.08 (95%CI: −0.22, 0.06; p=0.25). The direction of this effect is consistent with the placebo group experiencing slightly more improvement in weight-for-age z-scores over the course of the study than the GSH group, on average. Similarly, no difference was seen in the per-protocol population analysis (difference=−0.01; 95%CI: −0.13, 0.16; p=0.86). The unadjusted mean 24-week change from baseline in weight-for-age z-score was similar in the two groups, −0.02 (SD=0.28) in the GSH group and 0.04 (SD=0.30) in the placebo group.

Figure 2.

Mean absolute change in weight-for-age z-scores from baseline to week 12 and week 24 by treatment group. The number of participants contributing data at each time point are shown below and error bars show pointwise 95% CIs.

Changes in Height and Weight

The two treatment groups were similar at baseline with respect to weight, stature, and BMI (Table 1). Changes from baseline to week 12 and 24 were similar for the two treatment groups, with no significant differences between GSH and placebo groups in either the mean absolute or mean relative change from baseline to week 24 for any anthropometric measures. The adjusted treatment difference at week 24 for the mean absolute change in weight percentile was −2.9 (95%CI: −7.5, 1.7; p=0.21), for BMI percentile it was −0.40 (95%CI: −7.2, 6.4; p=0.91), and for height percentile it was - 2.4 (95%CI: −5.1, 0.4; p=0.09).

Change in Markers of Inflammation

The two groups were similar at baseline with respect to fecal calprotectin, neutrophil and platelet counts. At baseline visit, the GSH group had a mean hs-CRP of 2.2 mg/L (SD=3.7) and the placebo group had a mean of 0.8 (SD=1.2). At week 24 there were no statistically significant differences between groups in the change from baseline for any of these markers of inflammation (Table 2).

Table 2:

Changes in measures of intestinal and systemic inflammation between baseline and week 24 visits. Differences and p-values correspond to models adjusted for randomization strata.

| GSH (N = 30) | Placebo (N = 30) | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal calprotectin (log10(μg/g)) | ||||

| n | 29 | 26 | ||

| Mean absolute change (95% CI) | 0.05 (−0.16, 0.26) | −0.05 (−0.27, 0.16) | 0.11 (−0.17, 0.40)1 | 0.431 |

| Neutrophil (%) | ||||

| n | 28 | 25 | ||

| Mean absolute change (95% CI) | 1.8 (−3.0, 6.7) | −3.4 (−8.9, 2.2) | 5.0 (−2.0, 12.0)2 | 0.162 |

| Platelet (103/μL) | ||||

| n | 28 | 25 | ||

| Mean absolute change (95% CI) | 8.3 (−19.1, 35.7) | −1.6 (−28.8, 25.5) | 6.1 (−32.4, 44.5)2 | 0.752 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | ||||

| n | 29 | 25 | ||

| Mean absolute change (95% CI) | −0.45 (−1.74, 0.84) | −0.04 (−0.70, 0.62) | −0.55 (−2.06, 0.96)2 | 0.472 |

Model based estimates from a linear mixed effects model which incorporates week 12 measurement

Model based estimates from an ANCOVA model

Changes in Gastrointestinal Symptoms:

No significant differences were seen between the groups in the proportion of participants that improved from baseline to Week 24 for any gastrointestinal symptoms (data not shown).

Use of Antibiotics, Frequency of Hospitalization, Spirometry and Pulmonary Exacerbations

Eleven (37%) of the 30 participants in the GSH group experienced at least one pulmonary exacerbation during the study, as did 12 (40%) of the 30 participants in the placebo group. The rate of exacerbations in the GSH group was 0.11 events per participant-month compared to a rate of 0.07 events per participant-month in the placebo group (rate ratio=1.5; 95%CI: 0.8, 3.1; p=0.23). Two (7%) GSH group participants were hospitalized during the study, as were five (17%) placebo group participants (difference=−10%; 95%CI: −28%, 7%; p=0.42).

Fifteen participants in the GSH group, and 16 in the placebo group were able to perform spirometry reproducibly. At week 24, there was no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in mean absolute change from baseline in FEV1, FEV1 % predicted, FVC, or FVC % predicted (data not shown).

A similar proportion of participants in both treatment groups had oral antibiotics initiated during the study, 23 of 30 (77%) in the GSH group and 20 of 30 (67%) in the placebo group (difference=10%; 95%CI: −13%, 31%; p=0.57). The number of participants initiating inhaled antibiotics, IV antibiotics, or systemic corticosteroids was also similar between the two treatment groups (data not shown).

Adverse Events:

Overall, GSH was safe and well tolerated in this study. The percent of participants reporting at least one serious adverse event (SAE) was not statistically significant (GSH 3% vs. placebo 17%; difference=−13%; 95%CI: −31%, 3%; p=0.19). The rate of SAEs was lower in the GSH group (1 SAE, or 0.01 SAEs per participant-month) as compared to the placebo group (8 SAEs, or 0.05 SAEs per participant-month) with a rate ratio of 0.12 (95%CI: 0.01, 0.67; p=0.01). However, participants in the GSH group experienced more adverse events (AEs) on average, with a rate ratio of 1.2 (95%CI: 0.96, 1.5; p=0.11). The GSH group had 160 AEs experienced by 29 (97%) participants whereas the placebo group had 131 AEs among 29 (97%) participants. The most common events seen in both groups were cough, infective pulmonary exacerbation of cystic fibrosis, and pyrexia (data not shown).

Glutathione Mechanism of Action:

The two treatment groups were similar at baseline with respect to levels of the 48 measured redox and non-redox metabolites. After correction for multiple comparisons, there were no significant changes over the 24 weeks between the two treatment groups for any of the metabolites in either redox or non-redox categories.

Discussion

Optimal growth has a profound impact on pulmonary status, survival and overall well-being in patients with cystic fibrosis (2). The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend that all children reach a weight-for-length or BMI status of >50th percentile (1, 11). Dysfunction in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator can make achieving these nutritional recommendations challenging. Chronic intestinal inflammation is a characteristic of CF intestinal pathology, as evidenced by direct inspection of the intestinal mucosa (12) and by elevated fecal calprotectin (13, 14). Studies in the CF mouse have shown that laxatives and antibiotics, which improve or reverse inflammation in the intestine, also improve growth (15–17).

Oxidative stress has been demonstrated in the CF airway with redox imbalance contributing to tissue damage and a persistent inflammatory process. GSH is a tripeptide that is one of the most important antioxidants in humans (18), playing a role in epithelial proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis in the intestine (19). People with CF have decreased systemic levels of GSH (20), perhaps as the result of inflammatory mediators suppressing production or secretion of GSH. Reduced airway GSH may be due to failure to transport glutathione across the cell membrane as a result of CFTR dysfunction or consumption during inflammation processes (21). It is possible that reduced levels of GSH in the CF intestine may contribute to redox imbalance and the development of intestinal inflammation.

In a recent single center study, 44 participants received GSH or placebo for a six-month period; those on GSH experienced an average increase of 0.67 SD in weight-for-age z-score compared to 0.10 SD improvement in participants receiving placebo. Furthermore, improvements in BMI, height and fecal calprotectin were observed (4). This study suggested a link between improvement in intestinal inflammation and administration of GSH improving growth.

Our study replicated several aspects of the previous pilot studies of GSH in CF but enrolled 36% more participants, was performed at multiple centers and had better balance between the treatment and placebo groups at baseline. These factors make the results of the GROW study quite compelling: there was no difference in any of the growth parameters evaluated between the GSH and placebo groups. Because we had 90% power to detect a difference of 0.36 in mean weight-for-age z-score with our sample size, we had approximately a 10% chance of failing to see a difference of that magnitude assuming it truly exists (a Type II error). We cannot rule out that there may be a smaller effect of GSH that we could have detected with a larger sample size, however it would not be a clinically meaningful difference. Furthermore, there was no change in any of the secondary endpoints, including serum and fecal inflammatory markers.

What is the value of a negative study? In this case, GROW discourages the use of GSH as a supplement to impact growth or intestinal inflammation in people with CF. There is a distinct positive aspect to clarity in this area. People with CF endure complex treatment regimens; demonstrating lack of effectiveness of a supplement eliminates the need to add another medication to their treatments. Dietary supplements are often not reimbursed by insurance, and patients pay out of pocket. Our study demonstrates that this cost does not need to be borne by our patients with CF. It is expensive and difficult to carry out studies of low-cost food supplements; the willingness of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the TDN to do so has freed some of our patients from an unnecessary therapy.

Further research is needed to develop interventions to reduce inflammation in the CF intestine and promote appropriate growth in patients with CF. The advent of highly effective modulator therapy may play a role. Our study is a reminder that while randomized controlled multi-center clinical studies are difficult to perform, properly planned and executed trials to evaluate dietary supplements can help avoid an unnecessary increase in the medication burden of individuals with CF.

Supplementary Material

What is known, what is new.

What is known

The nutritional status of children with cystic fibrosis (CF) is strongly associated with mortality and morbidity

Intestinal inflammation and dysbiosis contribute to impaired digestion, absorption, and nutrient utilization in CF

People with CF have lower circulating levels of glutathione, a major antioxidant

What is new

Oral glutathione did not impact growth or change serum or fecal inflammatory markers in children with CF when compared to placebo.

Evaluating the role of oral glutathione in a larger, multicenter study prevents unnecessary increase in the medication burden of people with CF.

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

This clinical trial was supported by a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network (SJS, MB). Dr. Schwarzenberg receives support for an unrelated study from Gilead.

This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03020719)

No support for this manuscript came from the NIH, HHMI, or the Wellcome Trust

Footnotes

- The GROW study group

- Figure, Study design schematic

- Table, Cystic Fibrosis GI Parent Questionnaire (modified from (7))

- Methods, Redox and metabolomic methods

- Table, Exploratory metabolic outcomes

References

- 1.Stallings VA, Stark LJ, Robinson KA, Feranchak AP, Quinton H, Ad Hoc Working Group. Evidence-based practice recommendations for nutrition-related management of children and adults with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency: results of a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(5):832–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yen EH, Quinton H, Borowitz D. Better Nutritional Status in Early Childhood Is Associated with Improved Clinical Outcomes and Survival in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borowitz D, Durie PR, Clarke LL, Werlin SL, Taylor CJ, Semler J, et al. Gastrointestinal outcomes and confounders in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(3):273–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visca A, Bishop CT, Hilton S, Hudson VM. Oral reduced L-glutathione improves growth in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(6):802–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visca A, Bishop CT, Hilton SC, Hudson VM. Improvement in clinical markers in CF patients using a reduced glutathione regimen: an uncontrolled, observational study. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7(5):433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han B, Enas NH, McEntegart D. Randomization by minimization for unbalanced treatment allocation. Stat Med. 2009;28(27):3329–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Nyren O, Tibblin G. Reproducibility and validity of a postal questionnaire. The abdominal symptom study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1993;11(4):252–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prevention CfDCa. A SAS program for the 2000 CDC growth charts (ages 0 to <20 years) 2019. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm.

- 9.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(6):1324–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Costanzo M, Berni Canani R. Lactose Intolerance: Common Misunderstandings. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;73 Suppl 4:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borowitz D, Baker RD, Stallings V. Consensus report on nutrition for pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(3):246–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werlin SL, Benuri-Silbiger I, Kerem E, Adler SN, Goldin E, Zimmerman J, et al. Evidence of intestinal inflammation in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(3):304–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg M, Leach ST, Coffey MJ, Katz T, Strachan R, Pang T, et al. Age-dependent variation of fecal calprotectin in cystic fibrosis and healthy children. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(5):631–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JM, Leach ST, Katz T, Day AS, Jaffe A, Ooi CY. Update of faecal markers of inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:948367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Lisle RC, Roach E, Jansson K. Effects of laxative and N-acetylcysteine on mucus accumulation, bacterial load, transit, and inflammation in the cystic fibrosis mouse small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293(3):G577–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Lisle RC, Roach EA, Norkina O. Eradication of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in the cystic fibrosis mouse reduces mucus accumulation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42(1):46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norkina O, Kaur S, Ziemer D, De Lisle RC. Inflammation of the cystic fibrosis mouse small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286(6):G1032–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu G, Fang Y-Z, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J Nutr. 2004;134(3):489–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aw TY. Cellular Redox: A Modulator of Intestinal Epithelial Cell Proliferation. Physiology. 2003;18(5):201–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roum JH, Buhl R, McElvaney NG, Borok Z, Crystal RG. Systemic deficiency of glutathione in cystic fibrosis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1993;75(6):2419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galli F, Battistoni A, Gambari R, Pompella A, Bragonzi A, Pilolli F, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant therapy in cystic fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(5):690–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conrad C, Lymp J, Thompson V, Dunn C, Davies Z, Chatfield B, et al. , Long-term treatment with oral N-acetylcysteine: affects lung function but not suptum inflammation in cystic fibrosis subjects. A phase II randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Cyst Fibros 2015; 14(2):219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tirouvanziam R, Obukhanych TV, Laval J, Aronov PA, Libove R, Banerjee AG, et al. Distinct plasma profile of polar neutral amino acids, leucine and glutamate in autism spectrum disorders, J Autism Dev Disord 2012. 42(5):827–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mannery YO, Ziegler TR, Park Y, Jones DP, Oxidation of plasma cysteine/cystine and GSH/GSSG redox potentials by acetaminophen and sulfur amino acid insufficiency in humans, J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2010. 333(3):939–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandler JD, Margaroli C, Horati H, Kilgore MB, Veltman M, Liu HK et al. Myeloperoxidase oxidation of methione associates with early cystic fibrosis lung disease, Eur Respir J, 2018. 52(4); 1801118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.