Abstract

Background

Self-management behaviors can reduce the progression of an illness. Although various factors affect self-management, no study has been conducted on the self-management of tuberculosis (TB) through path analysis.

Objectives

This study evaluated the factors affecting self-management in TB patients using path analysis.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was done on 133 non-prisoner TB patients that referred to all health centers in Karaj, Iran, in 2017. A structured questionnaire was applied. Data were analyzed with SPSS-17 and Lisrel 8.8, utilizing statistical path analysis to evaluate the relationships between self-management and its related factors.

Results

Overall, 52.3% of the participants in the study were female and 47.7% were male. Respondents of were 46.9% smear-positive, 9.4% smear-negative, and 43.8% extra-pulmonary TB. Fit indices confirmed the model fitness and logical relationships between the variables according to the conceptual model (χ2 = 49.80, df = 25). The final path model showed that age (β = 0.84), attitude (β = 0.10), marital status (β = 0.04), and house condition (β = 0.03) impact self-management through the direct path. Knowledge (β = 0.83) and education (β = 0.16) affect self-management through both direct and indirect paths. Education indirectly affects self-management through both knowledge and attitude. Knowledge indirectly impacts self-management through attitude. In other words, knowledge and attitude mediate the relationship between some factors and self-management.

Conclusions

This study provided an empirical model that illustrates the relationships between self-management and related factors in TB patients. The knowledge can be the target of interventions in support of self-management.

Keywords: attitude, knowledge, path analysis, self-management, tuberculosis

BACKGROUND

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major cause of chronic pulmonary infection [1]. Approximately one-third of the world’s population is infected with TB bacilli and at risk of developing active TB. Each year, approximately 9 million people are affected by active TB, and about 1.5–2 million people die from it. As a result, TB is a global health concern [2, 3].

TB can cause prolonged and significant impairment of lung function such as bronchiectasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which increases the number of episodes of TB, especially in multidrug-resistant (MDR) patients [4–6]. The detection and appropriate treatment of active cases can play an important role in TB prevention. TB disease is treated with at least six months of combinations of several antibiotics to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance. Increased drug-resistant TB in some areas threatens the achievements of global TB control programs [7]. Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS) strategy has been the mainstay of adherence promotion since its introduction in the 1990s [8].

One of the most important factors in the success of treatment and fewer complications is increased awareness and adequate management of the disease by the patient. The self-management behaviors are routine activities including acceptance of treatment plan, self-monitoring behaviors, and establishing a link between treatment plan and disease symptoms that a person does to manage their chronic illness such as diabetes, epilepsy, asthma, and coronary artery disease. Self-management behaviors promote health, control the signs and symptoms of disease, and reduce the effects of the illness. Self-management behaviors include methods that affect the performance, emotions, interpersonal communication, and the quality of the treatment regimen [9, 10].

Self-management behaviors reduce the progression of illness and increase the patient’s quality of life through changes in lifestyle, decision-making about treatments tailored to the patient’s social context, monitoring activities, and management of signs and symptoms. These behaviors are a tool that helps patients to execute safely trained skills to control their illness and solve the common problems and complications of the disease [11, 12]. Socioeconomic factors such as low educational level, low income, and low quality of interpersonal and family relationships are serious problems with the self-management process [13].

Researchers have shown that self-management behaviors in some diseases improve patient outcomes and treatment acceptance, eliminate the complications of the disease and hospitalization, and increase the knowledge and skills of patients and their caretakers to maintain and improve their health [10, 11, 14–18].

Self-management behavior and its related factors have been researched in some chronic diseases such as diabetes, epilepsy, asthma, and coronary artery disease, but there has been no study conducted on TB self-management. Cho et al. [19] discussed socio-demographic factors, including gender, marital status, family structure, family support, and income influence self-care in TB patients. Researchers have investigated factors affecting the self-management in patients with chronic disease and revealed the impacts of socio-demographic (age, education, job, income), knowledge, attitude, family/community support, social connections, and the ability to deal with stress and stigma on self-management [20–24]. It has been revealed that socio-demographic factors including age, education, occupation, family support, residential locality, and income impact knowledge; education and income influence attitude [22, 24–27]. The research question guiding this investigation is which factors may directly or indirectly affect self-management behaviors among TB patients.

OBJECTIVES

Given that self-management behaviors can reduce illness progression, recognizing related factors is very important. Although various factors affect self-management, no study has been conducted on the self-management of TB through path analysis that examines the possibility of a mediating model to assay direct and indirect contributors to self-management among TB patients. The aim of this survey was to evaluate the factors affecting self-management among a sample of Iranian TB patients through path analysis.

METHODS

Design

This survey was a cross-sectional study conducted as a census on all non-prisoner TB patients in health care centers that have been implementing the DOTS strategy across Karaj, Iran. Data were collected between March 2016 and February 2017.

Participants

The study size was 133 non-prisoner TB patients that referred to all health care centers in Karaj, Iran, from March 2016 to February 2017. Every type of TB patient, including smear-positive/negative pulmonary TB and extra-pulmonary TB, participated in the study. The inclusion criteria were TB patients who completed at least two months of their treatment plan. The exclusion criteria were mentally disabled patients, individuals with a history of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and severe psychiatric disease. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Research variables

Socio-demographic characteristics included age, gender, nationality, marital status, education (e.g., illiterate, elementary, middle school, high school, and university), occupation, income, type of TB disease, location of living (urban, rural, margin), marital status, history of previous TB or another disease, history of TB in the family, housing conditions (number of rooms and number of people in the house), health access (distance to health facility), the number of hospitalizations after TB diagnosis, and cause of hospitalization. The dependent variables were knowledge, attitude, and self-management. Variables were used in the path analysis included age, marital status, education, number of rooms, distance to a health care center, knowledge, attitude, and self-management.

The knowledge questionnaire included 12 questions about the cause of TB, symptoms, ways of transmission, prevention, and treatment of disease. Each question was rated in such that a score of 1 was given to correct responses and a score of zero was used for incorrect/don’t know responses. The responses to these questions were added together to generate a knowledge score ranging from 0 to 12. Attitude questionnaire (9 questions) was structured on the five-point Likert scale (1 = quite agree, 2 = agree, 3 = no idea, 4 = disagree, and 5 = quite disagree). The attitude score ranged from 9 to 45. The self-management questionnaire (21 questions) included questions about drug consumption, medical visits, and lifestyle. Questions were structured on the five-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = always). The self-management score ranged from 21 to 105. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for knowledge, attitude, and self-management were respectively 0.781, 0.714, and 0.83. The questionnaire was completed by trained experts through interviews with TB patients. The total volume of samples was 133 people.

Statistical methods

Statistical presentation and analysis of the present studied data were carried out using the mean and standard deviation numbers with the percentage of cases. The mean of the self-management score was compared between patients admitted to the hospital and those not admitted using the two-tailed t-test. We used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the effect of the marital status on the knowledge, attitude, and self-management scores. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the relationships among the variables except for the variable marital status that was computed by the coefficient eta. Then, the collected data were analyzed using path analysis. Path analysis was applied to evaluate the relationships among socio-demographic status, self-management, knowledge, and attitude. Path analysis is a statistical method that can be used to analyze relationships between a set of independent variables and a dependent variable. Path analysis is an extension of the regression model, which researchers use to test the fit of a correlation matrix with a causal model that they test [28].

In relation to fitness indices of models in path analysis, chi-square to degrees of freedom index (χ2/df) <3 is preferred, even though some researchers consider a score of 4 and even 5 to indicate a good fit. Other indices for fitting the model include the normed fit index, comparative fit index, and the goodness of fit index, with preferred values >0.9. In the root mean square error of approximation criteria, a score of ≤0.05 indicates a good fit, and up to 0.08 is acceptable, although some sources consider a score up to 0.11 acceptable. SPSS-17 and Lisrel-8.8 software was used for data analysis with the application of path analysis.

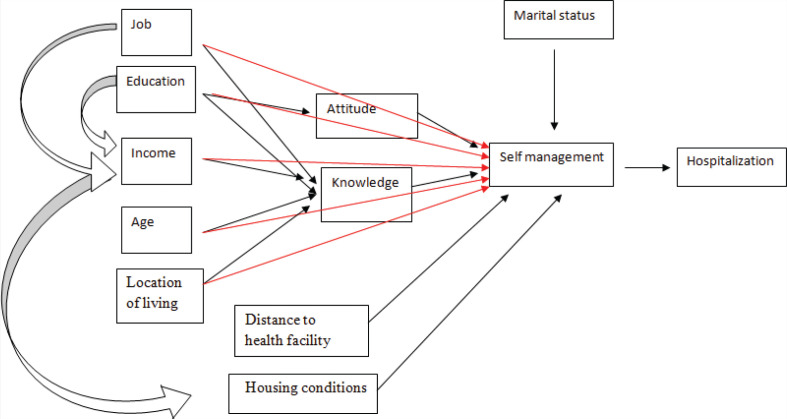

According to previous studies [22, 24–27], a conceptual framework is investigated by using Path analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized conceptual framework of the relationships among the study variables.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Of 133 participants in the study, 52.3% were female and 47.7% were male. The age of the people ranged from 7 to 88 years old (mean ± SD = 48.8 ± 17.76); the highest percentage was in the age group of 31–50 years (34.9%). Most of the patients were Iranian (83.2%), and most (89.3%) lived in the city. The type of TB disease in patients was: 46.9% positive smears, 9.4% negative pulmonary smear, and 43.8% extra-pulmonary. Demographic Characteristics of patients is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of TB patients

| Demographic characteristics | Frequency |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Valid Percent | ||

| Sex | Male | 63 | 47.7 |

| Female | 70 | 52.3 | |

| Age group | 1–10 | 2 | 1.6 |

| 11–30 | 23 | 17.8 | |

| 31–50 | 49 | 34.9 | |

| 51–70 | 43 | 33.3 | |

| >70 | 16 | 12.4 | |

| Nationality | Iranian | 111 | 83.2 |

| Non-Iranian | 22 | 16.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 24 | 18.3 |

| Married | 91 | 68 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Widow | 16 | 12.2 | |

| Educational level | Illiterate | 33 | 24.8 |

| Elementary | 36 | 27.1 | |

| Middle school | 16 | 12 | |

| High school | 34 | 25.6 | |

| University | 14 | 10.5 | |

| Tuberculosis type | Pulmonary smear positive | 62 | 46.9 |

| Pulmonary smear negative | 12 | 9.4 | |

| Extra pulmonary | 59 | 43.8 | |

| Location of living | Urban | 119 | 89.3 |

| Rural | 3 | 2.3 | |

| Margin | 11 | 8.4 | |

| Home distance to health care center | Less than 10 min | 36 | 27.1 |

| 10–20 min | 64 | 48.1 | |

| 20–30 min | 23 | 17.3 | |

| More than 30 min | 10 | 7.5 | |

Overall, 75.6% of patients were not admitted to the hospital after diagnosis of TB, and 24.4% were hospitalized at least once. The reasons for hospitalization included exacerbation of symptoms (50%), symptoms that failed to improve (16.7%), drug complications (6.7%), drug intolerance (3.3%), and disassociation in drug use (3.3%). Self-management level was significantly higher in patients who were not admitted to the hospital after TB diagnosis by using a two-tailed test analysis (self-management mean ± SD in non-admitted and admitted TB patients, respectively, was 90.39 ± 9.4 and 86.43 ± 10.1; p = 0.045). We used a one-way ANOVA to determine the effect of marital status on the knowledge, attitude, and self-management scores. There was a significant difference between self-management and marital status (p = 0.029). After the post hoc test (Bonferroni), self-management level was significantly higher in the married group than divorced and widowed individuals (p = 0.025).

Correlation coefficients

Prior to path analysis, bivariate analysis was used to assess the existing correlations between variables. As seen in Table 2, self-management was directly correlated with education, the number of rooms in the house, and knowledge. Knowledge was also directly correlated with education and the number of rooms in the house. The attitude was directly correlated with age and patient hospitalization.

TABLE 2.

Correlations between structural parameters

| Age | MS | Edu | HDH | NHR | PH | SM | PK | PA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| MS | 0.68 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Edu | –0.282** | 0.35 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| HDH | 0.154 | 0.105 | –0.060 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| NHR | 0.085 | 0.239 | 0.207* | 0.091 | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| PH | –0.071 | 0.159 | –0.027 | 0.033 | –0.051 | 1 | — | — | — |

| SM | 0.044 | 0.549 | 0.179* | –0.144 | 0.244** | –0.132 | 1 | — | — |

| PK | –0.039 | 0.359 | 0.342** | –0.137 | 0.224** | –0.078 | 0.236** | 1 | — |

| PA | 0.226** | 0.391 | 0.146 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.198* | 0.041 | 0.003 | 1 |

MS = marital status; Edu = education; HDH = home distance to health center; PH = patient hospitalization; SM = self-management; PK = patient knowledge; PA = patient attitude; NHR = number of house rooms.

Note: The correlations between the structural parameters were computed by the Pearson correlation coefficient, except for the variable MS which was by the coefficient eta.

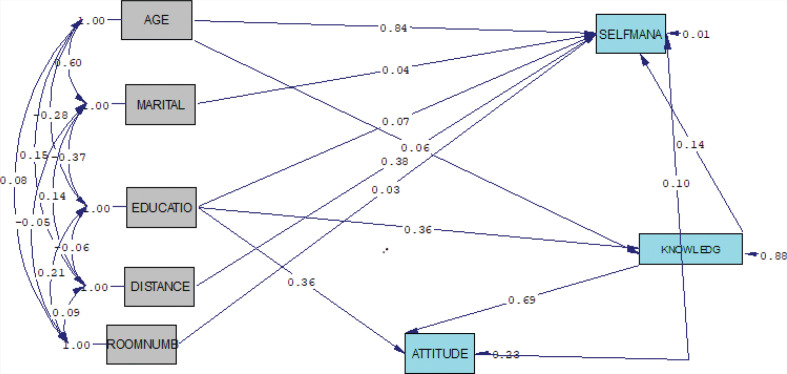

The relationship between self-management and its related factors in patients with TB was studied based on the path analysis model (Figure 2 and Table 3). According to the developed path diagram, the variable of age affects the self-management from both direct and indirect paths, but the indirect path was insignificant. Among the variables that affected self-management just through a path, the variable of age and number of rooms in the house were the highest (standardized beta coefficient; β = 0.84) and lowest (β = 0.03) impact respectively; higher age and the number of rooms in the house will lead to better self-management. The variable of knowledge had the highest impact on self-management among variables that influenced both direct and indirect paths (β = 0.83); as the individual’s knowledge increases, their level of self-management also enhances. Knowledge indirectly affects self-management through attitude (β = 0.69). Education also affects self-management through the direct and indirect paths (β = 0.16). Education indirectly impacts self-management through knowledge and attitude.

FIGURE 2.

Full empirical model (empirical path model for effects of factors among Iranian Tuberculosis Patients on self-management.

TABLE 3.

Path coefficients

| Variable | Direct effect | Indirect effect | Total effect | t-value (for direct) | t-value (for indirect | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.84 | 0.06* | 0.84 | 78.57 | 0.72 | 0.99 |

| Marital status | 0.04 | — | 0.04 | 3.57 | — | |

| Education | 0.07 | 0.0864 | 0.16 | 6.11 | 4.14 | |

| Distance | 0.38† | — | 0.38* | 1.94* | ||

| Room number | 0.03 | — | 0.03 | 3.22 | — | |

| Attitude | 0.10 | — | 0.10 | 5.63 | — | |

| Knowledge | 0.14 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 9.09 | 15.40 |

, not significant.

Fit indices confirmed the model fitness and logical relationships between the variables according to the conceptual model. In other words, the fitted model had no significant differences in the conceptual model (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Goodness of fit indices (n = 133)

| χ2 | df | CFI | GFI | NFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49.80 | 25 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.00 |

Note: df = degrees of freedom; CFI = comparative fit index; GFI = goodness of fit index; NFI = normed fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide an empirical model that illustrates the relationships between self-management and related factors in TB patients. We revealed (i) age, attitude, marital status, and house condition (number of rooms) had respectively the most impact on self-management just through the direct path; (ii) knowledge and education had an impact on self-management among variables that influenced both direct and indirect paths, knowledge had the greatest impact on self-management; (iii) education indirectly affects self-management through both knowledge and attitude. Knowledge indirectly impacts self-management through attitude. Knowledge and attitude mediate the relationship between some factors and self-management.

No previous research has investigated self-management behavior and its related factors in TB patients. Several types of research used a correlation method between TB self-care and related factors. They revealed factors, including gender, marital status, family structure, family support, income, and knowledge affect the self-care of TB patients [19, 29]. To our knowledge, our survey is the first research to investigate the relationships between variables that affect self-management in TB Patients using path analysis.

In this study, there was a significant direct and indirect relationship between knowledge and self-management so that the increased individual’s knowledge leads to enhancement of TB self-management, which is consistent with other studies in chronic disease self-management [24, 30]. The DOTS strategy that is done in health centers has been considered as a basic and effective factor in developing countries for better treatment and more adherence to the TB control program [8]. One of the activities in this program is training patients about the signs and symptoms of TB, prevention, correct drug use, and drug complications. Increased knowledge related to the disease can be very important for self-management. Therefore, the communication between the provider and the patient may play an important role in increasing knowledge, attitude, and self-management of their disease. Studies have shown educational interventions can increase the level of knowledge, behavior, and self-care of pulmonary TB patients [31, 32].

In our study, the results demonstrated that attitude directly affects self-management and mediates the effect of knowledge and education on self-management. Studies have shown that attitude contains feelings, beliefs, or opinions that could be both facilitators and barriers to self-management. Positive attitude to disease such as the increased perceptions of control is an important facilitator of self-management, and negative beliefs towards self-management, such as believing that self-management was time-consuming, inconvenient, or complex, prevented self-management behaviors [24, 33, 34]. In this study marital status directly affected self-management so that people who lived with other persons had better self-management. The presence of a life partner may influence self-management due to more supervision, providing reminders about medication, accompanying individuals to medical services, and attention of partner to disease [24, 30]. A life partner provides a better emotional and informational support for the patient and it is an important factor for chronic disease. These findings are consistent with other studies that revealed the social and family support is a determinant variable and could be important to successful self-management behavior of chronic illnesses [19, 35–37].

The results showed that house conditions, including the number of rooms, directly impact self-management so that living in houses that have more room leads to better self-management. Given that living in a separate room with good ventilation and sunshine is important in the prevention and treatment of TB, house conditions can be affected by self-management. Wardani et al. [38] studied TB incidence and related factors based on a structured equation model and revealed that the variable of housing condition was as latent variables of TB incidence. Their results indicated that people with lower education, occupation, income, and social class tend to have housed with overcrowded, inadequate ventilation, and indoor air pollutants. Those factors will increase the risk of TB [38]. Other studies have also shown housing conditions affect TB incidence [39, 40].

In this study, education had a direct effect on self-management in that people with higher education had better self-management. Education had an indirect effect through knowledge and attitude affect self-management. These findings are consistent with other studies that revealed the importance of education on knowledge, attitude, and self-management [26, 30, 38].

Our research showed that age directly impacts self-management so that a higher age is associated with better self-management. This can suggest that when people grow older, they care more about their health. Our findings in the bivariate analysis showed a direct correlation between age and attitude, so as age increased the attitude to TB disease increased, which can be one of the reasons for higher self-management. Other studies have shown a negative correlation between self-management/self-care or health literacy and age [25, 32, 41]. Grey et al. [42] showed age as an individual factor is variable in the self-management of chronic disease . This disparity in our study can be from methodological differences.

Limitations

There are several limitations within this study. First, our sample size was relatively small, which limits our power to detect significant results; therefore, further studies are needed to establish our model. Second, self-management was assessed by self-report scales that may not have adequately reflected these constructs. Third, the factors assessed in this study are low and more factors are needed to be studied.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we provided an empirical model that illustrates the relationships between self-management and related factors in TB patients. The most important factor that affects self-management through both direct and indirect paths is knowledge. The indirect path is through attitude so that increased knowledge leads to more positive attitudes to TB and improves self-management. Therefore, the communication between the health provider and the patient in health centers can play an important role in increasing knowledge, attitude, and self-management of their disease. We suggest that health education be increased by health professionals to both TB patients and their families who support the patients. Further studies are needed with more variables and sample sizes to establish our model.

DISCLOSURES

Acknowledgments

This study was the result of a research project with code 1198 that has been funded by Alborz University of Medical Sciences. We greatly appreciate health centers for collaboration in this research.

Author’s contributions

NG and TFH were involved in the study conception and design, NG and ZM, analyzed and interpreted the patient data as well as drafted the manuscript. ZS involved in writing up of the manuscript and data collection. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interests

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the approval of the research ethics committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences (ABZUMS.REC.1395.9).

Funding/Support

This study was the result of a research project with code 1198 that has been funded by Alborz University of Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salzer HJ, Wassilew N, Köhler N, Olaru ID, et al. Personalized medicine for chronic respiratory infectious diseases: tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases, and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Respiration 2016;92(4):199–214. doi: 10.1159/000449037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis control: epidemiology, strategy, financing: WHO report 2009. 2009: World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis report 2013. 2013: World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maguire G, Anstey NM, Ardian M, Waramori G, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis, impaired lung function, disability and quality of life in a high-burden setting. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis 2009;13(12):1500–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Valliere S, Barker R. Residual lung damage after completion of treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis 2004;8(6):767–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hnizdo E, Singh T, Churchyard G. Chronic pulmonary function impairment caused by initial and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis following treatment. Thorax 2000;55(1):32–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn SD, Zumla AI. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2011;378:57–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62173-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otu AA. Is the directly observed therapy short course (DOTS) an effective strategy for tuberculosis control in a developing country? Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2013;3(3):227–31. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(13)60045-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, et al. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Counsel 2002;48(2):177–87. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yadollahi S, Ashktorab T, Zayeri F, Safavibayat Z. Correlation between epilepsy self-management behaviors and seizure frequency among patients with epilepsy in Iran Epilepsy Association. Prev Care Nurs Midwifery J 2015;5(1):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang AT, Haines T, Jackson C, Yang I, et al. Rationale and design of the PRSM study: pulmonary rehabilitation or self management for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), what is the best approach? Contemp Clin Trials 2008;29(5):796–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper K, Smith BH, Hancock E. Patients’ perceptions of self-management of chronic low back paIn: evidence for enhancing patient education and support. Physiotherapy 2009;95(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson KM, McFarland L, Reiber G. Factors influencing disease self-management among veterans with diabetes and poor glycemic control. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(4):442–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0053-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGillion MH, Watt-Watson J, Stevens B, LeFort SM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a psychoeducation program for the self-management of chronic cardiac pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36(2):126–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustavsson C, Denison E, Koch L. Self-management of persistent neck paIn: a randomized controlled trial of a multi-component group intervention in primary health care. Eur J Pain 2010;14(6):630.e1–630e.11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swerissen H, Belfrage J, Weeks A, Jordan L, et al. A randomised control trial of a self-management program for people with a chronic illness from Vietnamese, Chinese, Italian and Greek backgrounds. Patient Educ Counsel 2006;64(1–3):360–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang T, Tan JY, Xiao LD, Deng R. Effectiveness of disease-specific self-management education on health outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Counsel 2017;100(8):1432–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, Rouleau M, et al. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(5):585–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho E, Kwon Y. Factors influencing self-care in tuberculosis patients. J Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Soc 2013;14(8):3950–7. doi: 10.5762/KAIS.2013.14.8.3950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tol A, Shojaezadeh D, Eslami A, Alhani F, et al. Analyses of some relevant predictors on self-management of type 2 diabetic patients. Hospital 2011;10(3). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulman-Green D, Jaser S, Martin F, Alonzo A, et al. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarship 2012;44(2):136–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01444.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angwenyi V, Aantjes C, Kajumi M, De Man J, et al. Patients experiences of self-management and strategies for dealing with chronic conditions in rural Malawi. PLoS One 2018;13(7):e0199977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abubakari A.-R, Cousins R, Thomas C, Sharma D, et al. Sociodemographic and clinical predictors of self-management among people with poorly controlled type 1 and type 2 diabetes: the role of illness perceptions and self-efficacy. J Diabetes Res 2016, 6708164: 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2016/6708164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman-Green D, Jaser SS, Park C, Whittemore R. A metasynthesis of factors affecting self-management of chronic illness. J Adv Nurs 2016;72(7):1469–89. doi: 10.1111/jan.12902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heijmans M, Waverijn G, Rademakers J, van der Vaart R, et al. Functional, communicative and critical health literacy of chronic disease patients and their importance for self-management. Patient Educ Counsel 2015;98(1):41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konda SG, Melo CA, Giri PA. Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding tuberculosis among new pulmonary tuberculosis patients in a new urban township in India. Int J Med Sci Publ Health 2016;5(3):563–70. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2016.01112015185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali AOA, Prins MH. Patient knowledge and behavioral factors leading to non-adherence to tuberculosis treatment in Khartoum State, Sudan. J Publ Health Epidemiol 2016;8(11):316–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright S. Correlation and causation. J Agr Res 1921;20(7):557–85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gumeyi SC. Relationship between knowledge and self-care practices regarding tuberculosis treatment among clients aged 20–40 years at Beatrice Road Infectious Hospital outpatient clinic. 2012; University of Zimbabwe Department of nursing, Science Faculty of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miles C, Arden-Close E, Thomas M, Bruton A, et al. Barriers and facilitators of effective self-management in asthma: systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient and healthcare professional views. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2017;27(1):57. doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0056-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jadgal KM, Nakhaei-Moghadam T, Alizadeh-Seiouki H, Zareban I, et al. Impact of educational intervention on patients behavior with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis: a study using the health belief model. Materia Socio-Medica 2015;27(4):229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howyida S, Heba A, Abeer Y. Effect of counseling on self-care management among adult patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Life Sci J 2012;9(1): 956–964. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundberg PC, Thrakul S. Type 2 diabetes: how do Thai Buddhist people with diabetes practise self-management? J Adv Nurs 2012;68(3):550–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05756.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orzech KM, Vivian J, Huebner Torres C, Armin J, et al. Diet and exercise adherence and practices among medically underserved patients with chronic disease: variation across four ethnic groups. Health Educ Behav 2013;40(1):56–66. doi: 10.1177/1090198112436970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosland AM, Piette JD, Lyles CR, Parker MM, et al. Social support and lifestyle vs. medical diabetes self-management in the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Ann Behav Med 2014;48(3):438–47. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9623-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carbone ET, Rosal MC, Torres MI, Goins KV, et al. Diabetes self-management: perspectives of Latino patients and their health care providers. Patient Educ Counsel 2007;66(2):202–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mead H, Andres E, Ramos C, Siegel B, et al. Barriers to effective self-management in cardiac patients: the patient’s experience. Patient Educ Counsel 2010;79(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wardani DW, Arden-Close E, Thomas M, Bruton A, Structured equation model of tuberculosis incidence based on its social determinants and risk factors in Bandar Lampung, Indonesia. Open J Epidemiol 2014;4(02):76. doi: 10.4236/ojepi.2014.42013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lönnroth K, Castro KG, Chakaya JM, Chauhan LS, et al. Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010–50: cure, care, and social development. The Lancet 2010;375(9728):1814–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60483-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lönnroth K, Holtz, T.H., Cobelens, F., Chua, J., et al. Inclusion of information on risk factors, socio-economic status and health seeking in a tuberculosis prevalence survey [Educational series. Serialised guidelines. Assessing tuberculosis prevalence through population-based surveys. Number 6 in the series]. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis 2009;13(2):171–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansyur CL, Rustveld LO, Nash SG, Jibaja-Weiss ML. Social factors and barriers to self-care adherence in Hispanic men and women with diabetes. Patient Educ Counsel 2015;98(6):805–10 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grey M, Knafl K, McCorkle R. A framework for the study of self-and family management of chronic conditions. Nurs Outlook 2006;54(5):278–86. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]