Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

KEY WORDS: Educational Justice, Learning Disparities, Social Determinants, Equitable Education

Abstract

AIM

The aim of the study was to propose a framework, social determinants of learning™ (SDOL™), an actionable model to address learning disparities and expand learning opportunities to support nursing student diversity, equity, and inclusion.

BACKGROUND

There is significant growth in the racial and ethnic diversity across students at all levels of higher education, mirroring the growing diversity of the US population. Yet, lower rates of persistence and higher attrition rates among these student groups continue.

METHOD

The authors established six socially imposed forces, causative domains, as foundational to the SDOL framework. Key attributes of each domain were identified through a literature search. A case study illustrates an initial study of interventions targeting specific domains of the framework aimed toward student success.

CONCLUSION

Equitable education for all has far-reaching implications across nursing education and higher education in general. Further development and testing of the SDOL framework will support the goal of equitable education for all.

It is a matter of moral obligation and societal responsibility to uphold our nation’s long-held principles of justice and respect for the equal dignity and worth of all people, with responsibility to those less fortunate. Basic notions of individual and social justice are viewed in terms of fairness and what is deserved, being given what is due or owed. Any denial of something to which a person has a right is a grievous act of injustice, regardless of the person’s circumstances (Kohlberg, 1971).

Work aimed to correct injustices in the public educational system in the United States begins with an understanding of root causes, such as underresourced schools in poverty-stricken communities, often black/African American communities (Semega et al., 2020). According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020), the pre-2020 pandemic unemployment rate of black/African Americans was twice as high as whites, with household income a little less than 60 percent than that of whites (Semega et al., 2020). Semega et al. (2020) also reported that black/African American communities facing poverty because of systemic inequalities experience insufficient school funding, often the result of lower local property taxes, and may therefore experience unequal learning opportunities. Underresourced schools represent one of our nation’s most significant examples of structural racism.

Belief in a basic right to education is based largely on the doctrine of justice, which presumes that like cases should be treated alike, and equals are to be treated equally. Where there is injustice in education, educators must work to address the systemic factors in order to establish just education. Educational justice will be achieved when all students have “the opportunities to find, figure out, and develop their skills and abilities based on their values and their communities’ values” (Levitan, 2016).

BACKGROUND

Ensuring educational justice means all students, regardless of ethnicity, race, culture, financial status, or other factors, have access to quality college education that leads to equitable careers. In comparison to other similar nations, the United States is ranked first in terms of academic quality (US News and World Report, 2020). On the other hand, a recent study of multiple data sets reported that US students from low-income communities score near the bottom of international rankings in relation to academic performance outcomes, with educational inequalities increasing at an alarming growth rate (Jackson & Holzman, 2020).

In its 2019 comprehensive report, Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education, the American Council on Education reported significant growth in racial and ethnic diversity across higher education mirroring the growing diversity of the US population (American Council on Education, 2019). Yet, the report noted that disparities across racial and ethnic groups continue. For example, Latino/Hispanic students have low educational attainment (63.4 percent of Latino/Hispanic men have a high school diploma or less) compared to Asian students (55.4 percent hold a bachelor’s or advanced degree). Black/African American students in bachelor’s programs have lower rates of persistence during the first year compared to all other groups, are more likely to receive federal loans and grants, and graduate with the highest student loan debt compared to other groups. An encouraging finding of the report is that racially or ethnically diverse students who earned a bachelor’s degree are more likely to pursue graduate education within the following four years compared to their white peers.

According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN, 2020a), racial and ethnic diversity among nursing students continues to grow. AACN reported 24.6 percent of baccalaureate nursing graduates were from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds in 2010 compared to 33.1 percent in 2019. Diversity among postlicensure nursing graduates has increased significantly for both master’s and doctoral-level programs. In 2010, 24.1 percent of master’s nursing graduates were non-white racial and ethnic minorities compared to 34 percent in 2019. In 2010, 17.3 percent of doctor of nursing practice graduates were racial and ethnic minorities compared to 32.8 percent in 2020. As 19.2 percent of the entire registered nurse population represents racial and ethnic minorities, the need to enhance diversity of the nursing workforce continues as a key goal (Sullivan Commission, 2014). An ideal would be for the racial and ethnic minority RN population to mirror the US population, which is 23.7 percent minority (US Census, 2019).

The work of educational justice begins with denouncing racism; embracing just principles; identifying and addressing the underlying, unjust, and avoidable social causes disadvantaging learners; and creating the necessary conditions for student success. A conceptual framework rooted in the context of systemic racism may promote a shared understanding and language for advancing educational justice. Commitment to a robust strategic plan for change is critical — involving key stakeholders, listening sessions, data analysis, design thinking, resource development, and a caring culture. Bold leadership is critical for the long-term structural transformation required to advance educational justice for all.

The focus of this article is to present a framework, social determinants of learning™ (SDOL™), to address learning disparities and expand learning opportunities for nursing students from under resourced backgrounds. The SDOL framework provides a structure to coalesce discussions, teachings, and research about the influence and impact of social determinants supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion. Key results from past studies are summarized to lend support to SDOL domains presented in the framework. Finally, a case study illustrates interventions and research implemented by Chamberlain University to evaluate the impact of programs supporting success among the growing numbers of students from diverse groups. Implications for educators and researchers are discussed.

DEVELOPING THE SDOL FRAMEWORK

Social Determinants of Health as Basis

During the past few decades, the public health sector has focused efforts to address disparities in health outcomes among various populations through the application of a social determinants of health model. Within this model, several social and environmental factors have been found to have greater impact on health outcomes compared to personal health choices or health care received; these include economics, community safety, access to transportation and adequate housing, social networks and support, and discrimination (Marmot et al., 2008).

Several theories, supported by decades of research, have confirmed social determinants of health are key drivers of health inequity (Solar & Irwin, 2010), but as research evolved, it became evident that a more complex theoretical framework was needed. Thus, a focus on a systems theory approach was put forth to further explain complex interrelationships among social determinants and differences in health outcomes impacting the human condition (Jayasinghe, 2015). In turn, health equity initiatives have informed federal and state health care systems and payor models, influencing the way care is provided (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018). From an academic perspective, developing and testing an SDOL framework may also inform and influence educators in the provision of support, remediation, and resources to students.

The social determinants of health model serves as a foundation from which to build an SDOL framework. The relationship between health and education are clear. Healthy People 2020 (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020) addresses social determinants of health and identifies access to educational opportunities and quality of education as key social determinants, in addition to access to health care services.

Linkages Between Health and Education

Education is a key social determinant that is linked to health across the life span in several ways. Higher educational attainment leads to better health decisions and greater access to employment opportunities and financial resources, and has a positive impact on psychosocial factors (Shankar et al., 2013). The quality and length of one’s education crosses over other social determinants of health, impacting an individual’s future well-being related to employment and economic factors (McGill, 2016). A large-scale, national study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Rasberry et al., 2017) found high school students with greater academic performance had significantly higher prevalence of protective health-related behaviors and significantly lower prevalence of health-related risk behaviors compared to students who were not passing their courses.

Theoretical Foundation for SDOL Framework

Bourdieu’s (1986) theory of cultural capital has been applied widely in many remediation and support programs for underresourced students to explain differences in academic outcomes (Bennett et al., 2015; Tinto, 1975). According to Bourdieu’s theory, one’s capital refers to all its forms — economic, social, and cultural — which vary in amount and type among individuals from varying backgrounds. The challenge with Bourdieu’s theory stems from its application to support vertical inequalities (i.e., devaluing baccalaureate education to support a rationale for credentialing or graduate education), thus furthering class inequalities (Marginson, 2016). As a result, students are expected to assimilate, in contrast to the system’s taking actions to change. Students from a less “dominant” class may be less able to benefit academically because of lack of adequate preparation, financial issues, or unfamiliar social or cultural norms. In this regard, a university will most likely not succeed in attempts to implement a social inclusion policy, as fundamental structural inequalities present within the institution may promote barriers and thus foster poor performance or self-exclusion by students.

Sorenson (1996) put forth a theory to identify the structural basis of social inequality based on socioeconomic factors. More recently, Naylor and Mifsud (2019) tested the structural inequality theoretical framework to identify different aspects of university culture and activities that may promote perceived inequalities or exclusivity among different groups of students. They hypothesized that students from various backgrounds interact with aspects of a university differently, resulting in different experiences. Faculty, students, curricula, the environment, campus activities, and the administration are all potential sources of structural inequality. The Naylor and Mifsud study examined current practices to support student inclusivity and equality across a wide diversity of higher education institutions based on either a cultural capital or social inequality theoretical framework. The selection of either framework was not related to the type or size of the institution, but rather the culture of the organization and leadership preferences. Naylor and Mifsud did not study the long-term impact of either framework and noted the dearth of research examining the impact of institutional structures and cultures on student outcomes. There is, however, some initial support demonstrating that institutional factors, compared to student factors, may be stronger predictors of retention (Institute for Social Science Research, 2017).

Framework to Address Learning Disparities/Expand Learning Opportunities

The achievement gap, disparities in educational outcomes based on race and socioeconomic status, has been the focus of research for several decades. The gap continues to widen for some groups, including students with disabilities and students struggling with poverty (National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2017). Although out-of-school factors are drivers of the gap, most initiatives to address this gap turn responsibilities and expectations toward in-school interventions (Rothstein, 2013). Despite best-intended supportive programs, attrition rates among students from underresourced backgrounds continue to rise (Metcalfe & Neubrander, 2016). Specific to supportive programs in nursing, Carthon et al. (2014) conducted a national study of 33 such programs and found enrollment and graduation results were mixed, depending on race and ethnicity.

In terms of the nursing literature, research examining the association between social determinants and nursing student outcomes is limited to primarily descriptive or qualitative studies addressing students’ financial issues, lack of social supports, inadequate student skills, and incidents of perceived discrimination (Barbe et al., 2018; Graham et al., 2016). Studies of social determinant attributes in nonnursing student populations were also examined to develop a more comprehensive understanding of an SDOL framework. As a growing number of students choose nursing as a second career (Rainbow & Steege, 2019), an SDOL framework that would elicit more robust research on interventions to support the success of diverse student populations is critical.

For purposes of this discussion, social determinants are defined as socially imposed forces that are causative factors that have implications for or influence one’s life. Those barriers would need to be assessed and addressed for students to move forward and progress. SDOL attributes may also be identified in positive terms and, in those cases, would be protective in nature. For example, being resilient in stressful situations is a determinant that drives learning and successful academic outcomes.

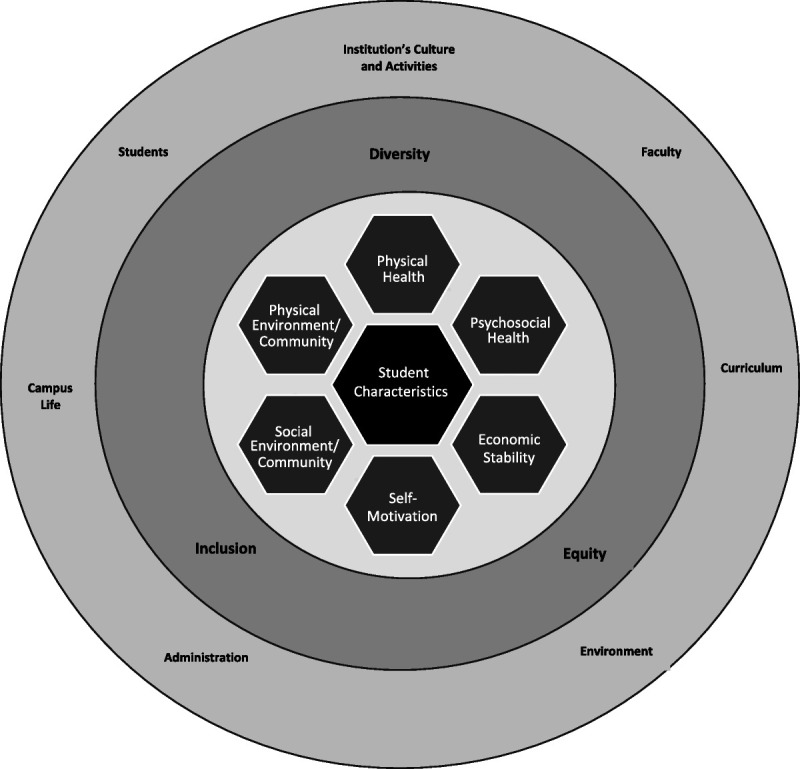

Figure 1 serves as an initial framework for an actionable model of SDOL amenable to further nursing studies. The six main domains of social determinants include physical health, psychosocial health, physical environment, social environment, economic stability, and self-motivation (see Supplemental Content, http://links.lww.com/NEP/A264 for attributes described in previous studies within each SDOL domain). Impacting the SDOL are the important factors of diversity, equity, and inclusion, which contribute to and influence each determinant of learning (Green, 2020). Diversity targets differences in student characteristics, including race, ethnicity, age, gender, socioeconomic status, culture, language, religious beliefs, and socioeconomics. Equity relates to access, opportunity, fair treatment, and advancement for all while eliminating barriers to full participation. Finally, inclusion ensures an invitation to all to participate in opportunities and share resources. All three factors are necessary to turn a social determinant barrier into an opportunity. The outer circle identifies different structural aspects of the university environment in which students interact. Potential sources of structural inequalities or equalities within institutional cultures may include faculty, students, curriculum, environment, campus activities, or administration (Naylor & Mifsud, 2019).

Figure 1.

A framework of social determinants of learning.

Aragon et al. (2020) cited an example of how elements of the SDOL framework may be put into action for further study. They noted the challenges nursing programs have in applying admissions criteria equitably given that some applicants are less advantaged because of lack of resources or factors within SDOL domains they may have experienced throughout their lives. In addition, there may be barriers to admission for these applicants, whether perceived or actual, within the university’s policies, personnel, or environment. To that end, adoption and evaluation of a holistic admission process may help faculty consider a broader scope of factors beyond the traditional academic metrics. These would be applied to all applicants based on their individual life experiences and potential for success (AACN, 2019).

Domains, Attributes, and Key Learnings

The authors sought to identify key attributes of each SDOL domain through a literature search of past studies of nursing and nonnursing students supporting each of the SDOL domains presented in the framework. Attributes listed under each SDOL domain (see Digital Content for Table 1, available at http://links.lww.com/NEP/A250) were included based on the following eligibility criteria: a) published between 2005 and 2020; b) published in the English language; c) focus on nursing or college students; and (d) findings tied to key student outcomes including academic performance, academic achievement, or student progression. The literature cited included key learnings from primary research, literature or scoping reviews, and descriptive or exploratory studies but is not meant to be a comprehensive review.

CHAMBERLAIN CASE STUDY STUDENT SUCCESS MODEL

Chamberlain University conceptualizes care as a noun rather than a verb, “The provision of what is necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance and protection of someone or something” (Groenwald, 2018, p. 2). A conceptual model of care as applied to educational justice means providing the necessary resources and support for underresourced students to become effective learners. Our description of the Chamberlain Care Student Success Model (CCSSM) illustrates some of the university’s interventions to target specific domains of the SDOL framework to ensure academic success. Assessment and evaluation of interventions have been primarily focused on prelicensure baccalaureate nursing students.

Chamberlain University is a private degree-granting institution dedicated to quality health care education in preparing nursing and other health care professional graduates to transform health care worldwide. During the 2018 to 2019 academic year, Chamberlain had an enrollment of more than 9,600 prelicensure nursing students, 59 percent from racially or ethnically diverse backgrounds. In comparison, the annual survey of the AACN (2020a) reported an average of 36 percent diversity among their 793 participating schools.

Designing a Model to Support Student Success

The CCSSM was developed as an integrated approach to academic and nonacademic student support. The focus is holistic, spanning the student’s journey from acceptance into the program through graduation and informing academic advising and the development of a personalized learning pathway supported through a caring relationship between faculty and student. To ensure equity in admission review processes, the admission committees have tools to help determine academic eligibility through a holistic lens as they review preadmission information about each candidate, both quantitative (e.g., prior academic performance, preadmission test performance) and qualitative (e.g., admission essays, patterns, or trends in academic record).

Using student life cycle risk assessments, the CCSSM provides indicators of current and predicted academic success through the nursing curriculum to NCLEX®-RN performance. Indicators include preadmission factors, key performance indicators, and nationally normed assessments throughout the program. As part of Chamberlain’s program evaluation, the Institutional Effectiveness and Research Team utilizes an advanced form of multiple regression analysis, propensity modeling, to predict each student’s “propensity to succeed” along the way. As students progress, the modeling continues to ingest data and provide updated outcome results so that students and faculty may evaluate the impact of student success interventions.

CCSSM interventions focus on increased individualized support and resources to students targeting their financial, psychosocial, and environmental needs. For example, to better provide social support to its growing diverse student population, Chamberlain has made great efforts to recruit a diverse faculty and leadership team. AACN (2020b) reported in their most recent national survey that 20.3 percent of full-time faculty and 17.1 of faculty leaders are racial and ethnic minorities.

Specific to NCLEX support, previous studies consistently report a small percent of the variance driving NCLEX-RN results may be explained by academic factors alone (16 to 28 percent; Simon et al., 2013). Chamberlain’s team found similar results; 26 percent of the variance in NCLEX-RN results was explained by academic factors. Nonacademic factors impacting students’ success are many and may be categorized as financial, social, psychological, or personal (Hanover Research, 2011).

Chamberlain developed and implemented an early assessment survey from an extensive literature review to better understand nonacademic indicators of risk to student success, such as critical thinking, motivation for learning, learning strategies, ability to cope with stress, social supports, use of the English language, family and work responsibilities, and emotional and financial stress. Nursing students complete the survey during their first nursing course and receive a report of their results to discuss with faculty advisors. Feedback to students is expressed in positive terms, encouraging the importance and application of each indicator to nursing program success.

Implementing and Evaluating CCSSM Interventions

To develop an approach to just, equitable education for all students, an interventional approach is being tested. Understanding out-of-school SDOL attributes that either pose a risk to student success or bolster success can guide the identification of in-school interventions to mitigate those risks (Rothstein, 2013), thus supporting each individual student and fostering an equitable educational environment for all students. Early assessment survey results are being used to design program interventions to ameliorate student risk. These interventions have been termed Care Connections, as they focus on ways to connect students to faculty, support staff, peers, and administrators in order to promote student engagement within the institution’s culture of care.

The first Care Connections program piloted mindfulness techniques for students. Mindfulness has been examined primarily in small-scale studies of nurses and nursing students, but results demonstrating benefits to reducing stress and anxiety are promising (van der Riet et al., 2018). Chamberlain implemented a mindfulness program in the first nursing course to heighten students’ awareness of the importance of being present in the moment, increase self-care and self-awareness to support their success, and inspire their becoming effective professional nurses. Mindfulness techniques have potential to impact factors such as stress, resilience, ability to focus, self-confidence, and engagement, all important to support students’ psychosocial health within the SDOL framework. More than one third of 750 new students enrolled in the January 2020 class reported reduced stress levels, improved attention span, and heightened focus on their studies. Participation in the program was also associated with a 3.5 percentage point increase in persistence as compared to two prior new student cohorts.

Plans for Further Development

To support a culture of equitable education for all students, development of a diversity and inclusion Care Connection is underway. The Chamberlain University Institutional Review Board approved an exploratory study of all prelicensure BSN students to gain insights about the campus cultural climate, particularly as it relates to linguistic and ethnic diversity and inclusion, that is, feelings of belonging, the quality of relationships, ways the university demonstrates or does not demonstrate diversity and inclusion, and awareness of available tools and resources. Students affirm that experiences with faculty and advisors, perceptions of racial climate, and inclusion and diversity efforts all play an important role in their perceptions of belonging as an attribute of the “social environment” SDOL domain. Plans for further Care Connection interventions include belonging, motivation for learning, and coaching for success.

BELONGING

This intervention expands upon the diversity and inclusion initiative and will address the SDOL domain of “social environment/community.” Qualitative interviews are a next step in understanding student perception of “fit” and the effectiveness of specific diversity and inclusion efforts. The goal is belonging in a truly equitable learning environment where social cohesion, characterized by self-worth, perceived sameness, and unity and high levels of satisfaction, exists among all students, evidenced by equality in student performance in both academic and social outcomes.

MOTIVATION FOR LEARNING

Addressing the SDOL domain of “self-motivation,” this intervention will be faculty facing to develop an understanding of motivation for learning research from a theoretical perspective, manifested by active participation in a learning environment, growth mindset to improve motivation in learning, student support for becoming self-directed, and lifelong learning.

COACHING FOR SUCCESS

This intervention will provide social work resources for students to access federal and state financial aid, housing, food and transportation assistance, learning technologies, counseling services, and job placement services while in school. The use of social workers on campuses has been a recent strategy for educational institutions. Patel and Field (2020) addressed threats to low-income students brought about by COVID-19. They described how social workers provide “wraparound support” for underrepresented students, developing mechanisms and helping students solve and cope with problems impacting their ability to learn.

IMPLICATIONS FOR EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

Equitable education for all has far-reaching implications, across nursing education and higher education in general. Although the focus of this work is on baccalaureate degree nursing programs, further research is recommended in order to test potential applicability across associate degree nursing programs.

Greater diversity is needed among leaders, strategists, admission and student advisors, and faculty in order to contribute to the design and testing of the SDOL framework, domains, and attributes. Nursing education’s professional organizations and associations can likewise contribute to the framework’s development. Lastly, development in teaching, advising, and resourcing students is needed for faculty and student life professionals to further develop and implement the interventional approaches to addressing educational injustices.

Examples of further research on SDOL include interventions in support of student resilience and persistence to graduation, grade point averages, academic progress, self-confidence, motivation for lifelong learning, engagement with the learning community, sense of fit, graduation rates, licensing and certification pass rates, and employer satisfaction. Given the multilevel, multidimensional nature of lifelong learning, research approaches and methods should address key stakeholders and research teams who hold multiple perspectives and use multiple data collection methods. It would be expected that these teams participate in regular, collaborative meetings to discuss and share approaches to data collection and analytics in order to engage multiple perspectives and thus foster a research culture that will be positioned to engage in theoretical modeling based on literature review, drive a research agenda, and act on the significance and relevance of findings from these proposed studies. It is anticipated that the short- and long-term impact of these interventions on student and alumni success would be established from these studies.

CONCLUSION

The right to equitable education has not yet been realized in the United States. Calling out the causative social and structural factors that impact learning is a beginning; the responsibility to intervene and eliminate root cause factors can help students achieve their dreams. In the first half of the 20th century, Dewey urged an educational model to achieve social cohesion through deep understanding of individual student differences and identifying shared interests to expand students’ horizons through education (Dill, 2007). This approach is foundational to the ideal that all students can learn.

Students from diverse backgrounds can achieve social cohesion through a clear understanding of the SDOL and by embracing the associated interventions to mitigate risks. The vision for a framework for SDOL can be realized through a relationship with students and fostered in a learning community of belonging, understanding, and trust that launches students on a personalized learning journey of upward mobility through lifelong learning across the span of a career. In addition, to support appropriate, equitable patient care, nursing and health professions educators must embrace new approaches for increasing the number of ethnically diverse care providers today’s health care system needs. As important as that is, there is an even more compelling reason to find new approaches for increasing diverse providers — it is the just thing to do.

The desired outcome of an SDOL framework is self-determined, accountable, confident, and courageous students who engage faculty and fellow students in order to build intellectual and social capital as a means to employment and a poverty-free future. The United States will have achieved educational justice when this outcome becomes the norm. As professionals whose practice is built on a culture of care, it is only right that nursing and health care education lead the way.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.neponline.net).

Contributor Information

Linda M. Hollinger-Smith, Email: lhollinger-smith@chamberlain.edu.

Karen Cox, Email: karen.cox@chamberlain.edu.

REFERENCES

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing . (2019). Enhancing diversity in the workforce. https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-information/fact-sheets/enhancing-diversity

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing . (2020a). Enrollment and graduations in baccalaureate and graduate programs in nursing. Author.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing . (2020b). Salaries of instructional and administrative nursing faculty in baccalaureate and graduate programs in nursing. Author.

- American Council on Education . (2019). Race and ethnicity in higher education. https://www.equityinhighered.org/resources/report-downloads

- Aragon S. Friday V. Green C. Kiger A. J. Lear T. Perkins D., & Velasco B. (2020). Equity, achievement, and thriving in nursing academic progression. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 15, 255–261 10.1016/j.teln.2020.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aughinbaugh A., & Rothstein D. S. (2015). Do cognitive skills moderate the influence of neighborhood disadvantage on subsequent educational attainment? Economics of Education Review, 44, 83–99. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko-Mould Y., & Laschinger H. (2014). Effects of incivility in clinical practice settings on nursing student burnout. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 11(1), 145–154. 10.1515/ijnes-2014-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe T. Kimble L. P. Bellury L. M., & Rubenstein C. (2018). Predicting student attrition using social determinants: Implications for a diverse nursing workforce. Journal of Professional Nursing, 24, 352–356. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A. Naylor R. Mellor K. Brett M. Gore J. Harvey A. James R. Munn B. Smith M., & hitty G. (2015). The critical interventions framework. Part 2: Equity initiatives in Australian higher education: A review of evidence of impact. The University of Newcastle. https://nova.newcastle.edu.au/vital/access/manager/Repository/uon:32946 [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. (1986). The forms of capital. In Richardson J. (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). : Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C. Sambrook S., & Irvine F. (2007). The meaning of empowerment for nursing students: A critical incident study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59, 342–351. 10.1111/j.13652648.2007.04331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley B. J., & Green A. C. (2013). Do health and education agencies in the United States share responsibility for academic achievement and health? A review of 25 years of evidence about the relationship of adolescents’ academic achievement and health behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 523–532. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthon J. Brooks M. Thai-Huy N. Chittams J. Park E., & Guevara J. (2014). Measuring success: Results from a national survey of recruitment and retention initiatives in the nursing workforce. Nursing Outlook, 62(4), 259–267. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K. M. Tang W. K. Chan W. H. Sit W. H. Choi K. C., & Chan S. (2018). Resilience and well-being of university nursing students in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 18(13), 1–8. 10.1186/s12909-018-1119-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J. (2007). Durkheim and Dewey and the challenge of contemporary moral education. Journal of Moral Education, 36(2), 221–237. 10.1080/03057240701325357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar S. Carr S. E. Counnaughton J., & Celenza A. (2019). Student motivation to learn: Is self-belief the key to transition and first year performance in an undergraduate health professions program? BMC Medical Education, 19, 111. 10.1186/s12909-019-1539-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphinstone B., & Tinker S. (2017). Use of the Motivation and Engagement Scales—University/college as a means of identifying student typologies. Journal of College Student Development, 58(3), 457–462. 10.1353/csd.2017.0034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S. Nater U. M., & Laferton J. A. (2016). Negative stress beliefs predict somatic symptoms in students under academic stress. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23, 746–751. 10.1007/s12529-016-9562-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C. L. Phillips S. M. Newman S. D., & Atz T. W. (2016). Baccalaureate minority nursing students perceived barriers and facilitators to clinical education practices: An integrative review. Nursing Education Perspectives, 37(3), 130–137. 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green C. (2020). Equity and diversity in nursing education. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 15, 280–283. 10.1016/j.teln.2020.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groenwald S. L. (Ed.) (2018). Designing and creating a culture of care for students and faculty. Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Hanover Research . (2011). Predicting college student retention. https://www.algonquincollege.com/academic-success/files/2014/12/Predicting-College-Student-Retention-Literature-Review-1.pdf?file=2014/12/Predicting-College-Student-Retention-Literature-Review-1.pdf

- Hawkins J. E. Wiles L. L. Karlowicz K., & Tufts K. A. (2018). Educational model to increase the number and diversity of RN-BSN graduates from a resource-limited rural community. Nurse Educator, 32(4), 206–209. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B. Cormier C. Hebert E. Naquin M., & Wood R. (2018). Health and health care issues among upper-level college students and relationships to age, race, gender, and living arrangements. College Student Journal, 52(1), 7–20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323175338_Health_and_health_care_issues_among_upper-level_college_students_and_relationships_to_age_race_gender_and_living_arrangements [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social Science Research . (2017). Review of identified equity groups: Appendices to the consultation paper. Appendix B. Key results. University of Queensland. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M., & Holzman B. (2020). A century of educational inequality in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(32), 19108–19115. 10.1073/pnas.1907258117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe S. (2015). Social determinants of health inequalities: Towards a theoretical perspective using systems science. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(17), 1–8. 10.1186/s12939-015-0205-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation . (2018). Beyond health care: The role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Author. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/ [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A., & Wightman P. (2011). Parental job loss and children's educational attainment in black and white middle-class families. Social Science Quarterly, 92(1), 57–78. 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00757.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L. (1971). Stages of moral development as a basis for moral development. In Beck C. M. Crittenden B. S., & Sullivan E. V. (Eds.), Moral education: Interdisciplinary approaches. : Newman. [Google Scholar]

- Larson M. Orr M., & Warne D. (2016). Using student health data to understand and promote academic success in higher education settings. College Student Journal, 50(4), 590–602. [Google Scholar]

- Levitan J. (2016, May 2). The difference between educational equality, equity, and justice…and why it matters. AJE Forum. www.ajeforum.com/the-difference-between-educational-equality-equity-and-justice-and-why-it-matters-by-joseph-levitan/ [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. W., & Mai L. J. (2018). Impact of mindfulness meditation intervention on academic performance. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(3), 366–375. 10.1080/14703297.2016.1231617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marginson S. (2016). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education, 72(4), 413–434. 10.1007/s10734-016-0016-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Friel S. Bell R. Houweling T., & Taylor S. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372(9650), 8–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill N. (2016). Education attainment linked to health throughout the lifespan: Exploring social determinants of health. The Nation’s Health, 46(6), 1–19. https://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/46/6/1.3 [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe S. E., & Neubrander J. (2016). Social determinants and educational barriers to successful admission to nursing programs for minority and rural students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 32(5), 377–382. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger M. Dowling T. Guinn J., & Wilson D. T. (2020). Inclusivity in baccalaureate nursing education: A scoping study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 36, 5–14. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Assessment of Educational Progress . (2017). Nation's report card: Achievement flattens as gaps widen between high and low performers. https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/inside-school-research/2018/04/nations_report_card_2018_us_achievement.html

- National Center for Homeless Education . (2018). Supporting college completion for students experiencing homelessness. https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/he-success.pdf

- Naylor R., & Mifsud N. (2019). Structural inequality in higher education: Creating institutional cultures that enable all students. https://www.gie.unsw.edu.au/towards-structural-inequality-framework-student-retention-and-success

- Nyet B. Omey E. Verhaest D., & Baert S. (2019). Does student work really affect educational outcomes? A review of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(3), 896–921. 10.1111/joes.12301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . (2020). Healthy People 2020: Social determinants of health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

- Olson M. A. (2012). English-as-a-second-language (ESL) nursing student success: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 19(1), 26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., & Field K. (2020). Vulnerable students: Creating the COVID-era safety net. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt V. Powis D. Levett-Jones T., & Hunter S. (2015). The influence of critical thinking skills on performance and progression in a pre-registration nursing program. Nurse Education Today, 35(1), 125–131. 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbow J. G., & Steege L. M. (2019). Transition to practice experiences of first- and second-career nurses: A mixed-method study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28, 1193–1204. 10.1111/jocn.14726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasberry C. N. Tiu G. F. Kann L. McManus T. Michael S. L. Merlo C. L. Lee S. M. Bohm M. K. Annor F., & Ethier K. A. (2017). Health-related behaviors and academic achievement among high school students. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(35), 912–927. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6635a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roksa J., & Kinsley P. (2019). The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Research in Higher Education, 60(4), 415–436. 10.1007/s11162-018-9517-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. (2013). Why children from lower socioeconomic classes, on average, have lower academic achievement than middle-class children. In Carter P. L., & Welner K. G. (Eds.), Closing the opportunity gap (pp. 61–77). : Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryabov I. (2016). Colorism and educational outcomes of Asian Americans: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Social Psychology of Education, 19, 303–324. 10.1007/s11218-015-9327-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salamonson Y. Roach D. Crawford R. McGrath B. Christiansen A. Wall P. Kelly M., & Ramjan L. M. (2020). The type and amount of paid work while studying influence academic performance of first year nursing students: An inception cohort study. Nursing Education Today, 84, 104213. 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar S. Aleem A., & Nadeem M. A. (2019). Health related quality of life and its correlation with academic performance of medical students. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 35(1), 1–5. 10.12669/pjms.35.1.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semega J. Kollar M. Creamer J., & Mohanty A. (2020). Income and poverty in the United States: 2018. Current population reports. US Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Shankar J. Ip E. Khalema E. Couture J. Tan S. Zulla R. T., & Lam G. (2013). Education as a social determinant of health: Issues facing indigenous and visible minority students in postsecondary education in western Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10, 3908–3929. 10.3390/ijerph10093908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey P. (2013). Stuck in place: Urban neighborhoods and the end of progress toward racial equality. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simon E. B. McGinness S. P., & Krauss B. J. (2013). Predictors variables for NCLEX-RN readiness exam performance. Nursing Education Perspectives, 34(1), 18–24. 10.5480/1536-5026-34.1.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar O., & Irwin A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson A. (1996). The structural basis of social inequality. The American Journal of Sociology, 101(5), 1333–1365. 10.1086/230825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan Commission . (2014). Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions: A report of the Sullivan Commission on diversity in the healthcare workforce. Author. 10.13016/cwij-acxl [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tee S. Ozcetin Y., & Russell-Westhead M. (2016). Workplace violence experienced by nursing students: A UK survey. Nurse Education Today, 41, 30–35. 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinto V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125. 10.3102%2F00346543045001089 [Google Scholar]

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics . (2020). Unemployment rates by age, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpsee_e16.htm

- US Census . (2019). Quick facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120218

- US News and World Report . (2020). Best countries for education. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/best-education

- Van der Riet P. Levett-Jones T., & Aquino-Russell C. (2018). The effectiveness of mindfulness meditation for nurses and nursing students: An integrated literature review. Nurse Education Today, 65, 201–211. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald A. Muennig P. A. O’Connell K. A., & Garber C. E. (2014). Associations between healthy lifestyle behaviors and academic performance in US undergraduates: A secondary analysis of the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment II. American Journal of Health Promotion, 28(5), 298–305. 10.4278/ajhp.120518-QUAN-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuff K. B. (2018). Does personalized goal setting and study planning improve academic performance and perception of learning experience in a developing setting? Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 13(3), 232–237. 10.1016/j.jtumed.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.