Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the short-term outcomes of discordant tumor assessments between DWI-MRI and endoscopy in patients with treated rectal cancer when tumor-bed diffusion restriction is present (“+DWI”).

Methods:

In this HIPPA compliant, IRB-approved retrospective study, rectal MRI and endoscopic reports were reviewed for patients with locally advanced primary rectal adenocarcinoma (LARC) treated with chemoradiotherapy or total neoadjuvant therapy and imaged between January 2016 and December 2019. Eligible patients had a +DWI and endoscopy within 2 weeks of each other. True positive MRI were those with tumor on endoscopy and/or biopsy (TPa) or in whom endoscopy was negative for tumor, but subsequent 3-month follow up endoscopy and DWI were both positive (TPb). The positive predictive value of DWI-MRI was calculated on a per-scan and per patient basis. DWI negative MRI exams were not explored in this study.

Results:

397 patients with nonmetastatic primary LARC were analyzed. After exclusions, 90 patients had 98 follow-up rectal MRI studies with +DWI. 76 patients underwent 80 MRI scans and had concordant findings at endoscopy (TPa). 17 patients underwent 18 MRI scans and had discordant findings at endoscopy (FP); among these, 4 scans in 4 patients were initially false positive (FP) but follow up MRI remained +DWI and the endoscopy turned concordantly positive (TPb). PPV was 0.86 per scan and per patient. In 4/18 (22%) scans and 4/17 (24%) patients with discordances, MRI detected tumor regrowth before endoscopy.

Conclusions:

Although most +DWI exams discordant with endoscopy are false positive, 22% will reveal that DWI-MRI detects tumor recurrence before endoscopy.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, MRI, functional, surgical endoscopy

Introduction

Clinical evaluation of rectal cancer tumor response in patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment requires dedicated pelvic MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI-MRI) and endoscopic evaluation of the rectum[1]. Patients may proceed to standard-of-care total mesorectal excision (TME) in most cases. In up to 38% of cases, complete tumor response may be noted in the surgical specimen but can be hard to recognize preoperatively. The non-surgical alternative using frequent observation for good responders (i.e. “Watch and Wait”) is growing in popularity [2–5]. Although patients who achieve complete clinical response (cCR) have survival rates of close to 90%, they require this regular surveillance to ensure continued treatment efficacy because tumor regrowth is reported to develop in 19 to 30% of cases[6; 7].

Although endoscopy is considered optimal in evaluating luminal cCR, MRI may provide additional information in detecting residual luminal tumor or regrowth and suspicious submucosal, mesenteric and nodal findings[1; 8]. Several prior studies showed that with the addition of DWI-MRI, the detection of microscopic viable tumor may be significantly increased when compared with T2 weighted images (T2W) alone[9; 10][11–13], leading to its inclusion in the ESGAR Guidelines[14]. Data has shown that while DWI may overlook minimal microscopic tumor and is thus relatively insensitive to complete response, when positive, it may indicate residual tumor and be used to help de-select a patient from non-operative management[1]. However, DWI signal is not tumor-specific and false positive results are a concern that could inappropriately disqualify a patient from a watch-and-wait approach if given too much credence in the clinical decision-making process.

In our experience, a surgeon can be easily discount a negative DWI-MRI (-DWI) as false negative in the face of a suspicious endoscopy. However, when endoscopy is normal or equivocal, a positive DWI-MRI scan (including high signal on DWI and low signal on ADC map) - indicating possible tumor presence - presents a clinical dilemma which the surgeon is hard-pressed to dismiss because tumor could be present beneath the luminal surface, invisible to the endoscope[15]. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to determine: (1) the meaning of +DWI in the tumor bed when endoscopy is normal (“discordant evaluations”) and (2) whether, as the authors hypothesize, MRI can diagnose tumor residua or regrowth earlier than endoscopy.

Materials and Methods

Patient demographics

This HIPPA-compliant and Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective study evaluated consecutive rectal cancer patients who underwent rectal MRI between July 2016 and December 2019, as derived from the radiological rectal MRI database and electronic medical records at our tertiary referral cancer center. The need for individual patient consent was waived. Inclusion criteria for this study consisted of patients with (1) at least one post-chemoradiotherapy [CRT] rectal MRI, either after (a) total neoadjuvant treatment (TNT); comprised of long-course CRT with chemotherapy added either before (“induction”) or after (“consolidation”) CRT, (b) post short-course radiotherapy (with waiting an approximate six-week interval) with or without additional chemotherapy[16] or (c) post long course CRT alone; and/or, if available, subsequent “surveillance” MRI’s (usually for those on watch-and wait, nonoperative management) and (2) biopsy-proven, non-mucinous, non-inflammatory bowel disease-associated rectal adenocarcinoma and (3) rectal endoscopy performed within 2 weeks before or after restaging MRI and (4) at least 1 MRI scan with +DWI in the treated tumor bed. Exclusion criteria included patients with either (1) no rectal +DWI MRI scans or with (2) DWI artifact or with (3) equivocal restriction on DWI-MRI. A given patient, due to multiple scans, could have a combination of TP and FP results during different scan/paired endoscopy times. From 397 patients after exclusions noted in Figure 1, the final study population consisted of 90 patients.

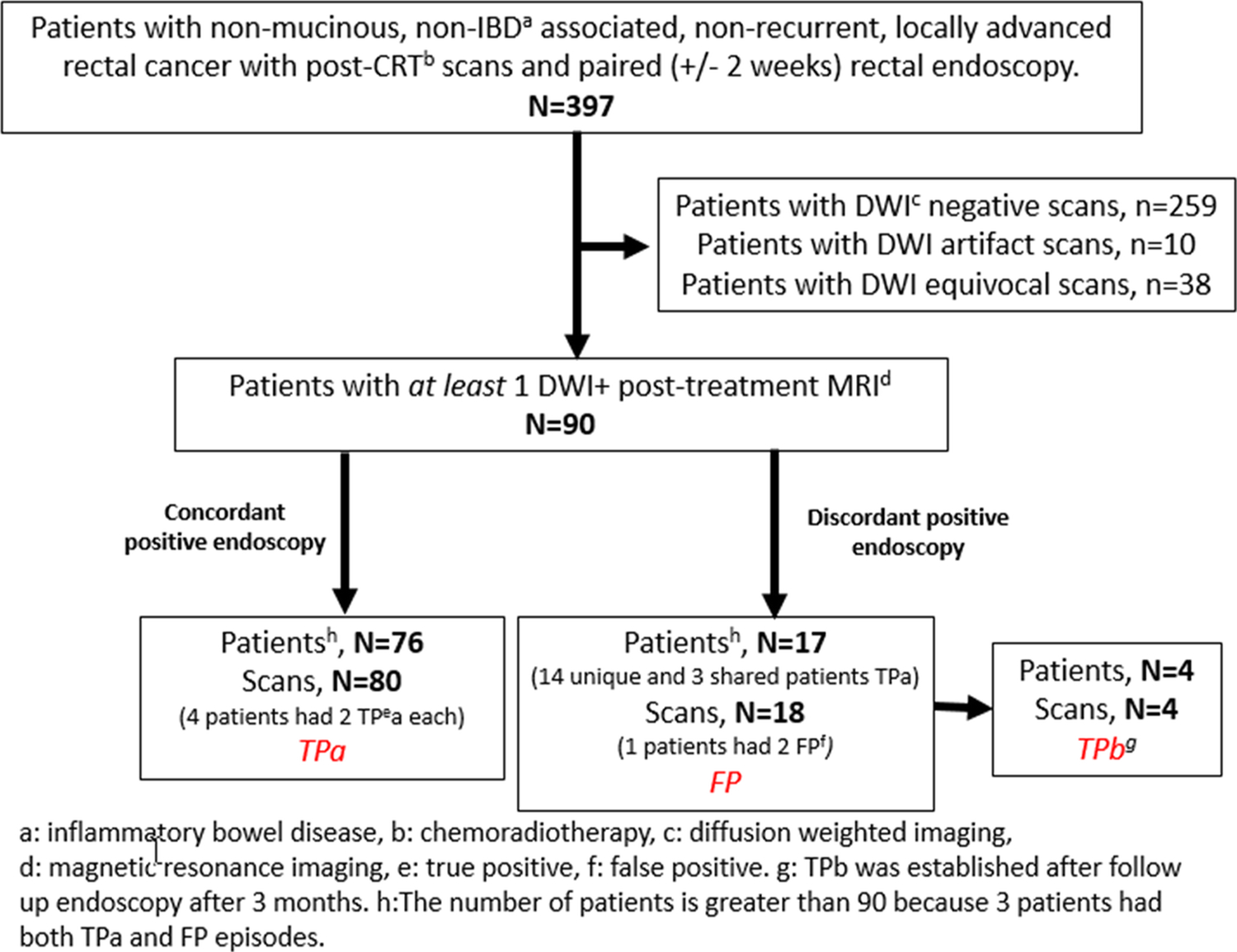

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Patient Recruitment

MRI protocol

Rectal MRI was performed on several GE Healthcare MRI scanners at a field strength of 1.5 and/or 3 Tesla, as previously described[17]. Specifically, DWI parameters included single-shot spin-echo echo planar imaging sequence, b-values: 0, 400 and 750–1,500 s/mm2; TR: 1,800–5,550 ms; TE: 60–112 ms slice thickness: 3–5 mm; interslice gap: 1 mm; FOV: 18–40 cm; matrix: 96–256 x 96–128; NEX: 3–6; mean acquisition time: 2.4 min.

Neoadjuvant treatment and scan timing

The intended chemoradiation (CRT) regimen involves the following; 4,500 cGy of radiation to the pelvis, with a further radiation ‘boost’ to the rectal neoplasm and nodal metastases of 5,000 cGy in 28 fractions (180–200 cGy each) over a 5- to 6-week period. Concurrent chemotherapy, either Fluorouracil (5-FU) or capecitabine, is delivered via intravenous infusion for each day of radiation therapy. Induction (pre-CRT) or consolidation (post-CRT) chemotherapy consisted of FOLFOX (Fluorouracil [5-FU] and Oxaliplatin). Most patients undergoing TNT received a minimum of 3 scans including (1) baseline, (2) post CRT, and (3) post-induction or consolidation chemotherapy. We did not evaluate MRI after chemotherapy only, since CRT would be given before a clinical decision was made between surgery and watch-and-wait.

MRI and endoscopic image evaluation

MR images were initially interpreted by eight independent attending radiologists who each interpret more than 200 rectal MRI per year. The radiologists were blinded to the paired endoscopy. No re-readings were performed for this study. Only patients with +DWI findings were included. The gold-standard for the presence of tumor included surgical pathology or biopsy, when available, or clinical and imaging follow up. Endoscopy was performed and interpreted by one of 8 fellowship-trained colorectal surgeons. One of 3 endoscopic response categories was assigned as defined by an expert international consensus committee [18]; complete response (Flat, white scar, telangiectasia, no ulcer, no nodularity) near complete response (Irregular mucosa, small mucosal nodules or minor mucosal abnormality, superficial ulceration, mild persisting erythema of scar) and incomplete response; visible tumor. Tumor regrowth was judged similarly.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed, and contingency tables were constructed to compare MRI-DWI findings with individual patient outcomes. True positive MRI (referred to as TPa) were those with endoscopy consistent with tumor presence within 2 weeks before or after MRI, with or without biopsy positive for tumor (Figure 2). In addition, we allowed a period of 3 months (<13 weeks) for follow up MRI and endoscopy (or surgical resection, n=2) in which to confirm tumor (while maintaining +DWI to indicate a true positive DWI in a case initially assessed as FP, (referred to as TPb) (Figure 3). False positive MRI occurred when a discordance based on the above definitions occurred within 2 weeks of endoscopy and remained discordant at 3 months follow up per above.

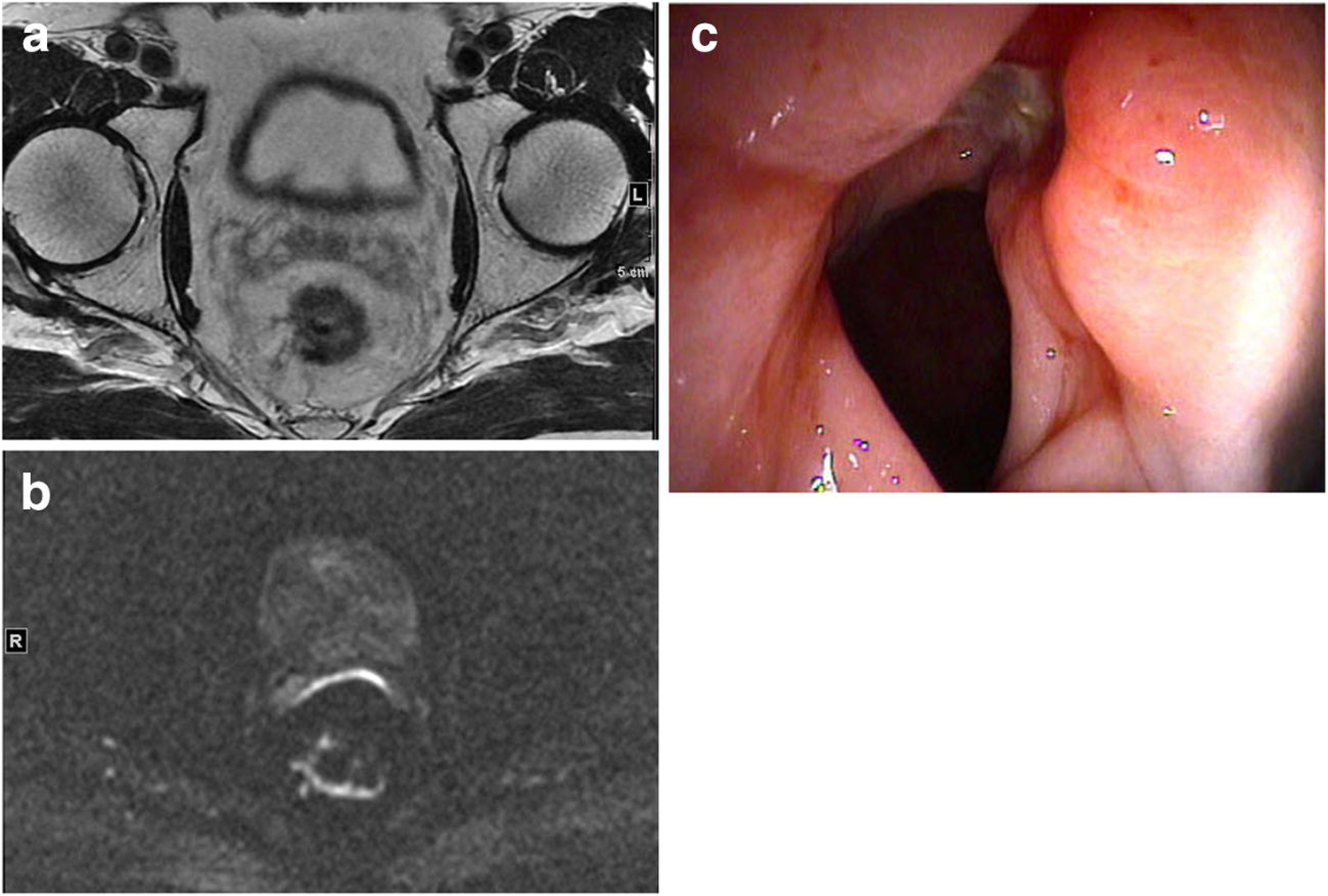

Figure 2.

Example of case with concordant DWI and endoscopy findings (TPa). 67-year-old male post total neoadjuvant treatment

A. Axial T2 weighted image of treated tumour bed with scar and residual intermediate signal tumour.

B. Axial DWI-MRI, b-800, showing irregular curvilinear and nodular diffusion restriction in rectal wall consistent with incomplete tumour regression

C. Flexible sigmoidoscopy of rectum showing circumferential nodular tumour persistence

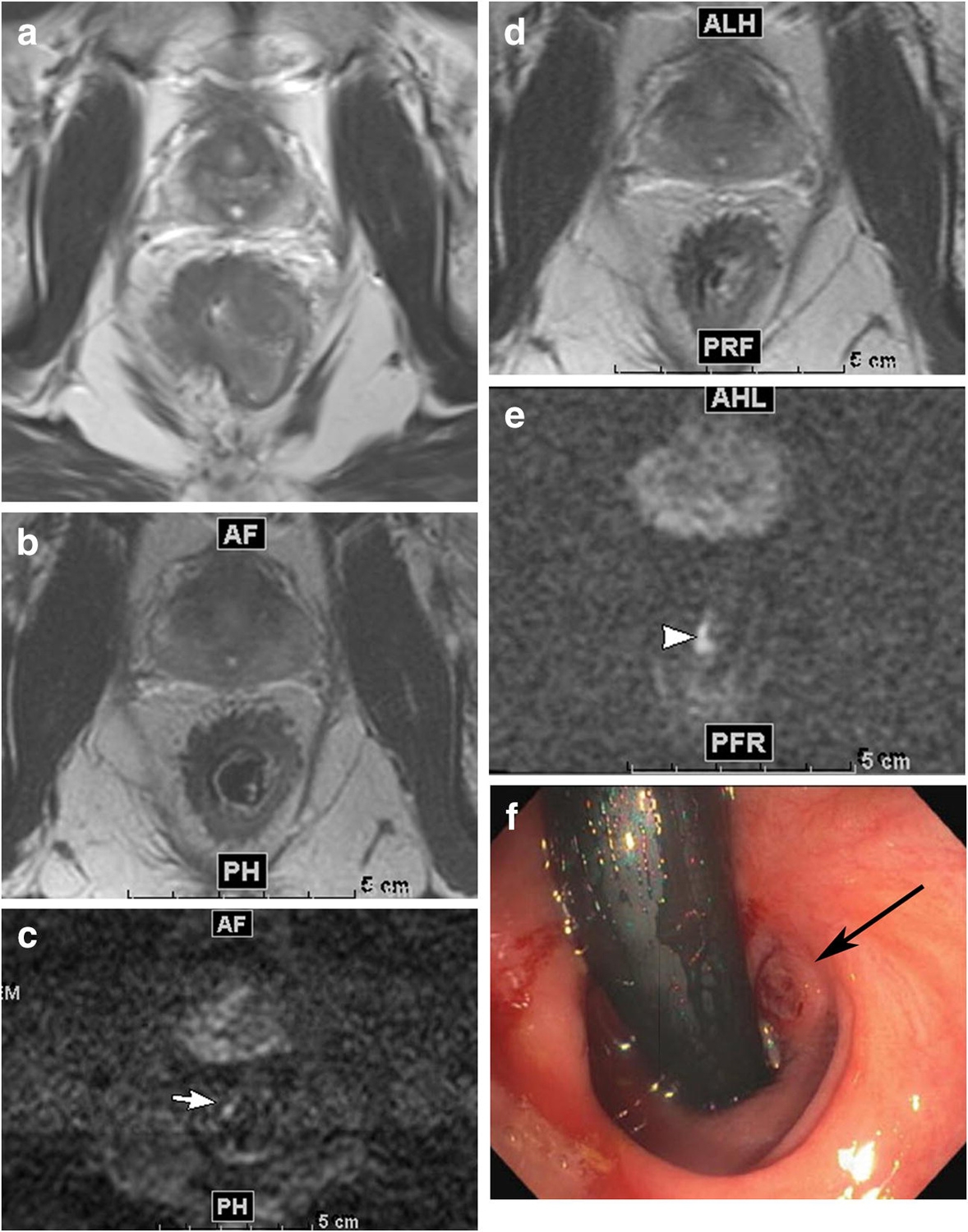

Figure 3.

Example of case with initially discordant DWI and endoscopy findings (FP) (normal endoscopy not shown) and subsequent concordance for tumour between DWI and endoscopy (TPb). 36-year-old male who underwent total neoadjuvant treatment for mid- and lower rectal adenocarcinoma

A. Axial T2 weighted image pre-treatment shows a portion of the tumour

B. Axial T2 weighted image after total neoadjuvant treatment shows thick scar in patient’s anterior right quadrant

C. Axial DWI-MRI, b1500, showing focal area of restriction (arrow). Some ghosting artefact that is minimal does not interfere with interpretation. Endoscopy (not shown) was normal at this time.

D. Axial T2 weighted image 11 weeks later shows thick scar in patient’s anterior right quadrant

E. Axial DWI-MRI, b1500, 11 weeks later, showing increase size of same area of focal restriction (arrow).

F. Flexible sigmoidoscopy shows small raised tumour nodule (arrow).

Biopsy was not necessary but either biopsy or surgery could be used to confirm or refute an endoscopic visual interpretation and was considered more definitive than endoscopy alone.

Positive predictive value of DWI-MRI was calculated on a per patient and a per scan basis as follows: Per patient PPV = #TPa patients + #TPb patients / (#TPa patients + #TPb patients) + final #FP patients, where final #FP patients= original #FP patients minus #FP patients converted to TPb patients, and Per scan PPV = #TPa scans + #TPb scans / (#TPa scans + # TPb scans) + #final FP scans, where # final FP scans = All FP scans - #FP scans converted to TPb scans). We did not record DWI negative scans in the analysis, as that was not the purpose of our investigation. As such, sensitivity, specificity and negative predictive value could not be assessed. All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2007 for Windows XP.

Results

Demographics (Figure 1, Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Features

| Variable | Total (n=90,%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.8 (33–94) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 (57) |

| Female | 39 (43) |

| cTa stage at primary staging | |

| 1–2 | 6 |

| 3 | 71 |

| 4 | 13 |

| cNb stage at primary staging | |

| 0 | 18 |

| + | 72 |

clinical Tumor stage as assessed by MRI

clinical Node stage as assessed by MRI

397 patients with primary non-mucinous, non-metastatic, locally advanced rectal cancer with available MRI were reviewed. Of these 397 patients, 90 individuals (51 males and 39 females, mean age 60.8 years, range 33–94 years) had at least one post-CRT, post-TNT, and/or surveillance rectal MRI with an abnormal +DWI at the site of treated tumor and had a paired endoscopy or surgical excision performed within two weeks of the abnormal MRI (Figure 1).

Imaging follow up (Table 2)

Table 2.

Imaging Follow up

| Follow up Type | Post-CRT* | Post TNT** | SS***1 | SS2 | SS3 | SS4 | SS5 | SS6 | SS7 | SS8 | SS9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of scans | 3 | 85 | 45 | 40 | 33 | 22 | 15 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

Chemoradiotherapy

Total neoadjuvant therapy

Surveillance scan

263 post CRT MRI scans were performed. The mean imaging follow-up time (defined as the date of the last scan minus the date of the post-all-treatment scan) was 77.5 weeks (range 8 – 178 weeks). Scan intervals were quite variable, some per research protocol (Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma [NCT02008656]) and most at the discretion of the surgeon, with the mean 20.9 weeks (range 6.5 – 51.7 weeks, median 19.8 weeks).

Patients

90 patients were included who had at least one rectal MRI scan post-all-therapy and/or on follow up surveillance imaging in which there was +DWI signal in the tumor bed. Treatment consisted of induction chemotherapy and then CRT (n=70), CRT and then consolidation chemotherapy (n=17) and CRT alone (n=3). Seventy-six patients’ +DWI scans were concordant with endoscopy (TPa, Figure 2). Seventeen patients’ +DWI scans were discordant with endoscopy (FP). (Please note that 3 patients had both TPa and FP episodes). Four FP patients from this group remained +DWI on the next paired MRI and endoscopy (≤ 3 months) when the endoscopy became concordant (i.e. tumor present), (TPb, Figure 3). 61/90 patients (68%) underwent definitive surgical resection. 29/90 patients (32%) with complete clinical response (cCR) continued on watch-and-wait, non-operative management for the duration of the study period.

Discordant MRI and Endoscopy

4/18 discordant scans (22%) (+DWI and normal endoscopy) were ultimately determined to be TPb, whereas 4 out of 17 patients (24%) had DWI-MRI and endoscopy paired scans in which +DWI initially appeared to be FP but was proven TP within 3 months (TPb). The positive predictive value (PPV) of +DWI scans was thus 80 TPa scans + 4 TPb scans / 84 TP scans +14 final FP scans= 0.86. PPV on a patient basis was 76 TPa patients + 4 TPb patients / 76+4 TP patients +13 final FP patients = 0.86.

Discussion

In our cohort of patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent treatment defined as standard of care at our institution and who were evaluated with both DWI-MRI and endoscopy, we found that most +DWI studies were concordant with a suspicious appearance on endoscopy, or a positive biopsy or tumor at surgery and thus, true positive. A significant number of +DWI cases (18% scans, 19% patients) however, were initially discordant with a normal appearing endoscopy and thus seemingly false positive for tumor. Nonetheless, within this group of patients, when we allowed for a subsequent 3 month follow up wherein there was persistent +DWI; endoscopy eventually became positive and thus, concordant with the MRI findings. This occurred in 4/18 scans (22%) and 4/17 patients (24%) and suggested that MRI detected the presence of tumor before endoscopy. Based on these findings, our investigation suggests that DWI continues to play an important supportive role in tumor assessment.

The ability to non-invasively predict residual tumor or tumor regrowth is clinically relevant in restaging treated rectal cancer patients since it would help identify patients deemed potentially ineligible for watch and wait treatment[19]. Small local tumor regrowth or incomplete tumor regression is challenging to diagnose on T2 weighted MRI sequences-only and the addition of DWI-MRI has been documented to add value in detecting microscopic tumor[20]. Our results suggest that DWI-MRI may identify tumor residua or regrowth below the mucosa, within the fibrotic scar, before penetrating the mucosal surface and becoming visible to the endoscope in up 22% of scans. We also found that most +DWI scans are actually concordant with endoscopy. While not perfect, a PPV of 86% to detect tumor confirms the usefulness of DWI-MRI.

Our results are similar to those already published but with additional new information regarding the natural history of discordant interpretations between MRI and endoscopy in a large cohort of patients with multiple follow up evaluations. Lambregts et al. assessed the value of DWI-MRI for tumour regrowth in 72 patients with rectal cancer. The addition of DWI to T2W-MRI increased sensitivity from 58% to 75% and decreased the number of equivocal MRIs. The authors found that the rate of ‘false-positives’ increased after the addition of DWI, however they found this occurred most frequently in “patients who developed tumour regrowth later in their post-CRT surveillance”. As stated by the authors, “this raises the question, however, of…whether these DWI findings might have been early features of regrowth...in which tumor growth starts within the fibrotic mass without distortion of the lumen [before] any visible changes on endoscopy”[20]. Van der Sande et al. evaluated findings on restaging MRI and endoscopy that resulted in a DWI false positive diagnosis of residual tumour in 36 patients with cCR after CRT for a FP rate of 51% [21]. By contrast, we demonstrated an initial false positive result of 19% (17/90); however, this was revised to 14% (13/90) on subsequent follow-up DWI-MRI where 4 patients subsequently became true positive. Our lower false positive rate may relate to our longer follow up times with surveillance MRIs where the scar matures and edema subsides allowing for increased specificity of the DWI signal to represent tumour. Nonetheless, a brief image re-review of our remaining FP cases revealed that approximately 1/3 were due to artefactual signal from air trapped in the lumen not specified in the report, 1/3 were unexplained and 1/3 were due to ulcers, hemorrhoidal banding artefact or misinterpretation errors. We now advocate administration of a mini-enema to reduce artefacts[22].

Our findings have clinical relevance that may inform the complex, challenging scenario of re-staging and surveillance of treated rectal cancer in patients undergoing watch and wait using combined modalities. The frequency of follow up and need for biopsy in these patients has been arbitrary and not standardized except within the context of prospective protocols[15]. Our study offers a proof of principle that tumour - as yet un-detectable by endoscopy-can occasionally be identified using the non-invasive functional MRI sequence of diffusion weighed imaging; and this offers an important addition to the care of these patients. We and others continue to advocate for use and optimization of DWI-MRI with continued efforts to reduce artefacts and improve tumour conspicuity and interpretation accuracy[22–25].

Our study has several limitations. It is retrospective with the known limitations of such a design. We opted to focus on a pragmatic question of how to interpret discordant findings when DWI was positive and endoscopy was negative rather than to perform a comprehensive review of the diagnostic accuracy of DWI-MRI and thus we cannot comment on overall performance characteristics of DWI-MRI in this setting. Our gold standard was mainly endoscopy with or without biopsy because we focused on capturing how to interpret the presence of diffusion restriction in the tumour bed at various intervals during the course of a patient’s treatment - often with multiple surveillance scans during nonoperative treatment. We could not use ultimate patient outcomes of histopathologic complete response or sustained clinical complete response, typical of outcomes articles, because that does not account for the intermediate course of the disease during follow up in which multiple tests are used, often subjectively, to appraise the tumour without the benefit of complete resection. Study design limitations could also include exclusion of “equivocal” DWI scans and those with artefact; real world scenarios[26], and lack of exploration of longer follow up intervals (e.g. 6 months). We felt that these longer intervals might be less credible. Finally, this study was performed in a tertiary care setting where surgeons and radiologists see many patients undergoing watch and wait follow up with numerous MRI and endoscopy exams limiting the generalizability of our results to the community setting.

To our knowledge, this is the only study specifically evaluating the natural history of discordant MRI-endoscopy evaluations during the post-neoadjuvant treatment evaluation and surveillance of patients undergoing standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer. We found that in 22% of discordant scans, DWI detection of incomplete response or of tumor regrowth - not visible at endoscopy - can occur and may require a subsequent endoscopy within 3 months for confirmation. Such information is hypothesis-generating, but we speculate that if a discordant evaluation is encountered between endoscopy and MRI, 3 months could be suggested as a maximum pragmatic interval for follow up evaluation with MRI and endoscopy to confirm a possibility that microscopic tumor was missed at endoscopy. Alternatively, it might provide a sufficient reason to justify a biopsy when such discordances are encountered. Further prospective studies may help inform suitable MRI and endoscopy follow up intervals, including the use of biopsy. In that vein, we eagerly await the final results of the OPRA study (NCT02008656).

Keypoints:

Most often, in post-treatment assessment for rectal cancer when DWI-MRI shows restriction in the tumor bed and endoscopy shows no tumor, +DWI MRI will be proven false positive.

Conversely, our study demonstrated that, allowing for sequential follow up at a 3-month maximum interval, DWI-MRI may detect tumor presence in the treated tumor bed before endoscopy in 22% of discordant findings between DWI-MRI and endoscopy.

Our results showed that the majority of DWI-MRI positive scans in treated rectal cancer concur with the presence of tumor on endoscopy performed within 2 weeks.

Funding

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Non-Common Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- +DWI

diffusion restriction is present at diffusion weighted imaging with associated low signal on the ADC map

- cCR

clinical complete response

- cGy

centi-Gray

- CR

complete response

- CRT

chemoradiotherapy

- DWI-MRI

diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging

- ESGAR

European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology

- FOV

field of view

- GE

General Electric

- HIPPA

Health Insurance Portability and Protection Act

- NEX

number of signal averages

- OPRA

Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma

- SS

surveillance scans

- T2W

T2 weighted imaging

- TE

time to echo

- TME

total mesorectal excision

- TNT

total neoadjuvant treatment

- TPa

true positive, conventional definition

- TPb

true positive after initial false positive and allowing for 3 months

- TR

time to recovery

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Guarantor:

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Marc J Gollub.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and Biometry:

No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper.

Informed Consent:

Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

Ethical Approval:

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Methodology

• retrospective

• diagnostic or prognostic study

• performed at one institution

Contributor Information

Marc J. Gollub, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065

Jeeban P. Das, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065

David D.B. Bates, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065

J. Louis Fuqua, III, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065.

Jennifer S. Golia Pernicka, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065.

Sidra Javed-Tayyab, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065.

Viktoriya Paroder, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065.

Iva Petkovska, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Department of Radiology, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065.

Julio Garcia-Aguilar, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Division of Colorectal, Department of Surgery, 1275 York Avenue, NY, NY 10065.

References

- 1.Maas M, Lambregts DM, Nelemans PJ et al. (2015) Assessment of Clinical Complete Response After Chemoradiation for Rectal Cancer with Digital Rectal Examination, Endoscopy, and MRI: Selection for Organ-Saving Treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 22:3873–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maas M, Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM et al. (2011) Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:4633–4640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Proscurshim I et al. (2006) Patterns of failure and survival for nonoperative treatment of stage c0 distal rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy. J Gastrointest Surg 10:1319–1328; discussion 1328–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habr-Gama A, Gama-Rodrigues J, Sao Juliao GP et al. (2014) Local recurrence after complete clinical response and watch and wait in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: impact of salvage therapy on local disease control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 88:822–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JD, Ruby JA, Goodman KA et al. (2012) Nonoperative management of rectal cancer with complete clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg 256:965–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JJ, Strombom P, Chow OS et al. (2019) Assessment of a Watch-and-Wait Strategy for Rectal Cancer in Patients With a Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Therapy. JAMA Oncol 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5896:e185896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W et al. (2004) Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg 240:711–717; discussion 717–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schurink NW, Lambregts DMJ, Beets-Tan RGH (2019) Diffusion-weighted imaging in rectal cancer: current applications and future perspectives. Br J Radiol 92:20180655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Paardt MP, Zagers MB, Beets-Tan RG, Stoker J, Bipat S (2013) Patients who undergo preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer restaged by using diagnostic MR imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 269:101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambregts DMJ, Delli Pizzi A, Lahaye MJ et al. (2018) A Pattern-Based Approach Combining Tumor Morphology on MRI With Distinct Signal Patterns on Diffusion-Weighted Imaging to Assess Response of Rectal Tumors After Chemoradiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum 61:328–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dzik-Jurasz A, Domenig C, George M et al. (2002) Diffusion MRI for prediction of response of rectal cancer to chemoradiation. The Lancet 360:307–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Lee JM, Hong SH et al. (2009) Locally advanced rectal cancer: added value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the evaluation of tumor response to neoadjuvant chemo- and radiation therapy. Radiology 253:116–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambregts DM, Beets GL, Maas M et al. (2011) Tumour ADC measurements in rectal cancer: effect of ROI methods on ADC values and interobserver variability. Eur Radiol 21:2567–2574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ, Maas M et al. (2017) Magnetic resonance imaging for clinical management of rectal cancer: Updated recommendations from the 2016 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur Radiol 10.1007/s00330-017-5026-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith FM, Wiland H, Mace A, Pai RK, Kalady MF (2014) Clinical criteria underestimate complete pathological response in rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum 57:311–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cercek A, Goodman KA, Hajj C et al. (2014) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy first, followed by chemoradiation and then surgery, in the management of locally advanced rectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 12:513–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hotker AM, Tarlinton L, Mazaheri Y et al. (2016) Multiparametric MRI in the assessment of response of rectal cancer to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: A comparison of morphological, volumetric and functional MRI parameters. Eur Radiol 26:4303–4312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JJ, Chow OS, Gollub MJ et al. (2015) Organ Preservation in Rectal Adenocarcinoma: a phase II randomized controlled trial evaluating 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with chemoradiation plus induction or consolidation chemotherapy, and total mesorectal excision or nonoperative management. BMC Cancer 15:767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gollub MJ, Hotker AM, Woo KM, Mazaheri Y, Gonen M (2018) Quantitating whole lesion tumor biology in rectal cancer MRI: taking a lesson from FDG-PET tumor metrics. Abdom Radiol (NY) 43:1575–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambregts DM, Lahaye MJ, Heijnen LA et al. (2016) MRI and diffusion-weighted MRI to diagnose a local tumour regrowth during long-term follow-up of rectal cancer patients treated with organ preservation after chemoradiotherapy. Eur Radiol 26:2118–2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Sande ME, Beets GL, Hupkens BJ et al. (2019) Response assessment after (chemo)radiotherapy for rectal cancer: Why are we missing complete responses with MRI and endoscopy? Eur J Surg Oncol 45:1011–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayaprakasam VS, Javed-Tayyab S, Gangai N et al. (2020) Does microenema administration improve the quality of DWI sequences in rectal MRI? Abdom Radiol (NY). 10.1007/s00261-020-02718-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Griethuysen JJM, Bus E, Hauptmann M et al. (2017) Air artefacts on diffusion-weighted MRI of the rectum: effect of applying a rectal micro-enema. Insights into Imaging ECR 2017 – BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 8:S187 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambregts DMJ, van Heeswijk MM, Delli Pizzi A et al. (2017) Diffusion-weighted MRI to assess response to chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: main interpretation pitfalls and their use for teaching. Eur Radiol 27:4445–4454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates DDB, Golia Pernicka JS, Fuqua JL, 3rd et al. (2020) Diagnostic accuracy of b800 and b1500 DWI-MRI of the pelvis to detect residual rectal adenocarcinoma: a multi-reader study. Abdom Radiol (NY) 45:293–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Griethuysen JJM, Bus EM, Hauptmann M et al. (2018) Gas-induced susceptibility artefacts on diffusion-weighted MRI of the rectum at 1.5T - Effect of applying a micro-enema to improve image quality. Eur J Radiol 99:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]