Abstract

We herein report two patients with early-stage autoimmune gastritis who did not exhibit complete atrophy. Endoscopic examinations showed no manifestations of severe atrophic gastritis, but revealed a mosaic pattern with slight swelling of the areae gastricae restricted to the corpus in both patients. In the patient in case 2, upper gastrointestinal barium X-ray radiography revealed a slightly protruded irregular areae gastricae throughout the gastric body, except for in the antrum. Our findings emphasize the need for clinicians to recognize that autoimmune gastritis might be present in the absence of severe atrophic gastritis; this can aid in the identification of the early stages of autoimmune gastritis.

Keywords: autoimmune gastritis, early-stage, areae gastricae, autoimmune disease, endoscopy

Introduction

Autoimmune gastritis (AIG) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the stomach that may remain asymptomatic for many years before progression to gastric atrophy (1,2). To our knowledge, there have been few reports concerning endoscopic analyses of patients with AIG who do not exhibit complete atrophy, as most of these patients have not been clearly diagnosed. Recently, multiple pseudopolyps were reported as a characteristic endoscopic finding in patients with early-stage AIG (3).

We herein report two patients with early-stage AIG who exhibited different manifestations from previous reports. In particular, we present the endoscopic and upper gastrointestinal barium X-ray radiography (UGI-XR) images of patients with early-stage AIG.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 40-year-old woman underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for screening purposes. Six months prior to screening, she had been diagnosed with adult-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. She was receiving insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes mellitus but had not been prescribed proton-pump inhibitors.

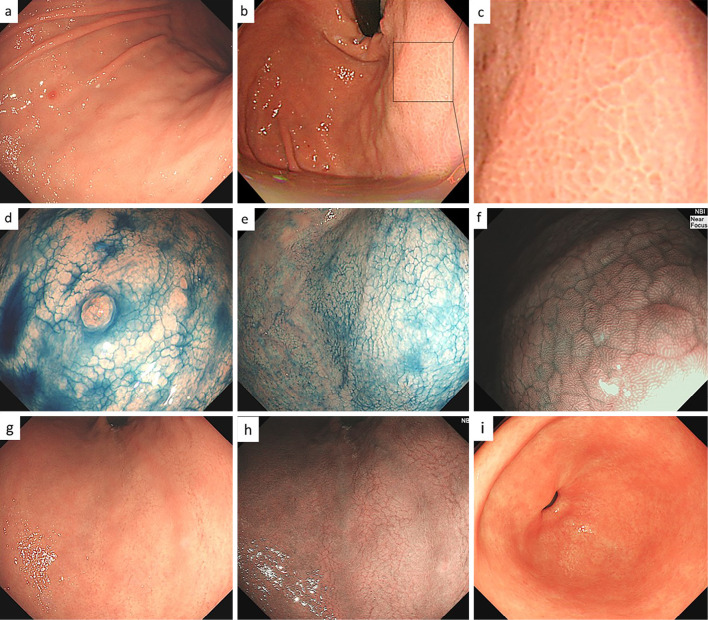

An endoscopic examination revealed a small hyperplastic polyp on the greater curvature of the corpus with slightly thickened and edematous mucosa (Fig. 1a). Polygonal areae gastricae surrounded by a reticular border in a mosaic-like pattern were observed on the greater curvature of the gastric body and fundus (Fig. 1b, c). These findings, including slight swelling of the areae gastricae, were confirmed using the indigo carmine method (Fig. 1d, e). Near-focus mode (×45 optical magnification) with narrow-band imaging facilitated visualization, revealing slightly enlarged and rounded pits (Fig. 1f). On the lesser curvature of the stomach, swelling of the areae gastricae was not evident, and multiple slightly depressed lines were present (Fig. 1g). These findings were further clarified by narrow-band imaging (Fig. 1h). In contrast to these mucosal changes in the corpus, the antrum mucosa was completely normal (Fig. 1i). A histopathological examination of tissue taken from the antrum revealed no atrophy or inflammation (Fig. 2a), while biopsy specimens from the greater curvature of the gastric corpus exhibited uneven infiltration of plasma cells and lymphocytes involving the full thickness of the lamina propria (Fig. 2b). Biopsy specimens from the lesser curvature of the corpus showed focal infiltration of plasma cells and lymphocytes; these findings were suggestive of early-stage AIG (4,5). Intact parietal cells exhibited pseudohypertrophy, including parietal cell protrusion with slight oxyntic gland dilatation (Fig. 2c).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic findings in the patient in case 1. a) Non-atrophic mucosa and a small hyperplastic polyp were present in the greater curvature of the corpus. b, c) Polygonal areae gastricae surrounded by a reticular border in a mosaic-like pattern were observed. d, e) Endoscopic image of the corpus with 0.2% indigocarmine chromoendoscopy. A mosaic pattern was clearly visible. f) Magnified narrow-band imaging of the corpus. A slightly enlarged, round pit was seen. g) Non-atrophic mucosa, with multiple depressed lines mimicking cracked mucosa, were present on the lesser curvature of the corpus. h) Narrow-band imaging of the lesser curvature. Multiple depressed lines were visible. i) Normal antrum.

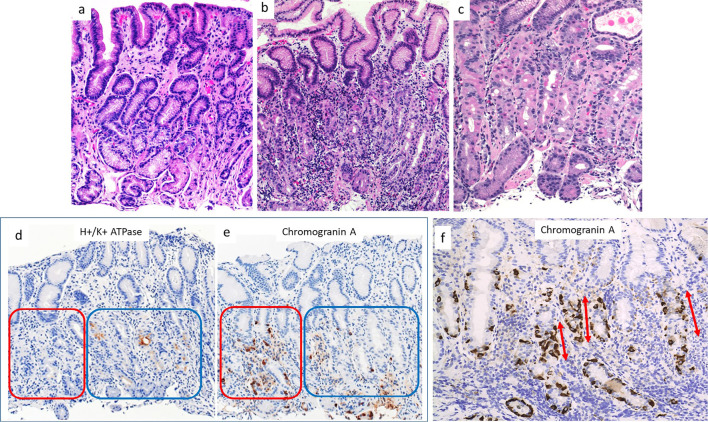

Figure 2.

Histopathological findings from various parts of the stomach in the patient in case 1. a) Tissue taken from the antrum. No inflammation or atrophy was present. b) Tissue taken from the greater curvature of the corpus. Lymphocytes and plasma cells were present in deeper, glandular tissue. c) Tissue taken from the lesser curvature of the corpus. Focal lymphocytic destruction of fundic glands was present in deeper tissue. Slight dilatation of oxyntic glands was observed, with parietal cell protrusion. d,e) Immunohistochemical staining for H+/K+ATPase and Chromogranin A. Parietal cells were lost on the left side (red square) but remained on the right side (blue square). ECL cells were more abundant in regions without parietal cells than in those with parietal cells (red square). f) Immunohistochemical staining for chromogranin A. Linear ECL cell hyperplasia was present (arrows).

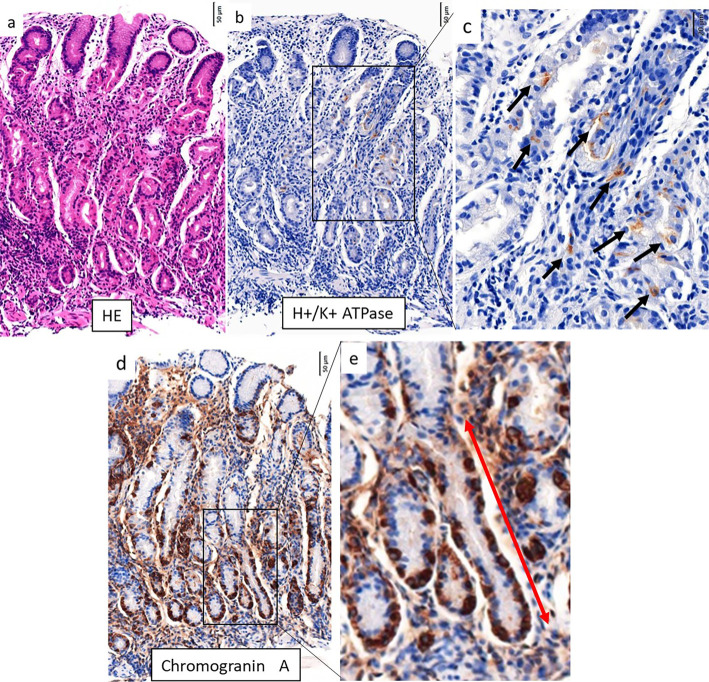

Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the infiltrating lymphocytes cells mainly comprised CD4+ T cells. H+K+ -ATPase staining showed that parietal cells remained in some areas, whereas they were completely absent from other areas, even in tissue from the same biopsy specimen (Fig. 2d). Chromogranin A staining demonstrated that enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells were more abundant in areas where parietal cells had disappeared than in others (Fig. 2e); in the disappeared areas, linear hyperplasia of ECL cells could be observed, comprising five adjacent ECL cells lining the glandular neck region (Fig. 2f). These findings suggested the focal destruction of oxyntic glands.

A serological examination showed that the anti-parietal cell autoantibody titer was high (1:640), the gastrin level was 894 pg/mL (normal level: <200 pg/mL), and anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG antibodies were <3 U/mL (normal level: <10 U/mL). These findings supported a diagnosis of active, early-stage AIG without complete atrophy.

Case 2

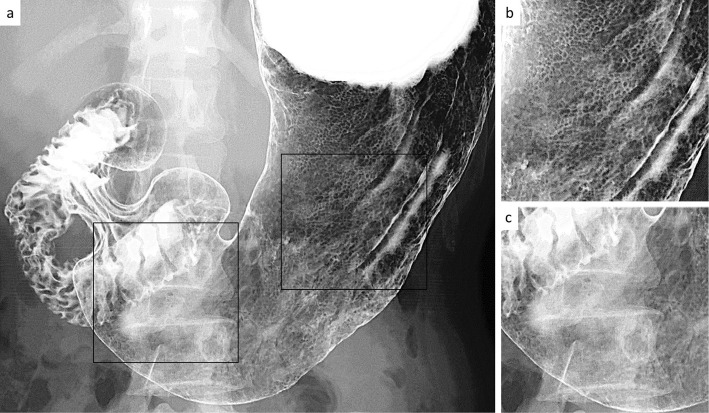

A 35-year-old woman began undergoing double-contrast UGI-XR as part of an annual health screening. She had no relevant previous history and was not taking any medications (e.g. proton-pump inhibitors). She had never received eradication therapy for H. pylori. During the initial screening, UGI-XR revealed slightly enlarged irregular areae gastricae throughout the gastric body; however, the folds were not enlarged, and the areae gastricae could not be detected on the antrum (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium X-ray radiography findings in the patient in case 2. a) Full view of the stomach. b) Magnified image of the corpus (black square area on the right side in panel a). c) Magnified image of the antrum (black square area on the left side in panel a).

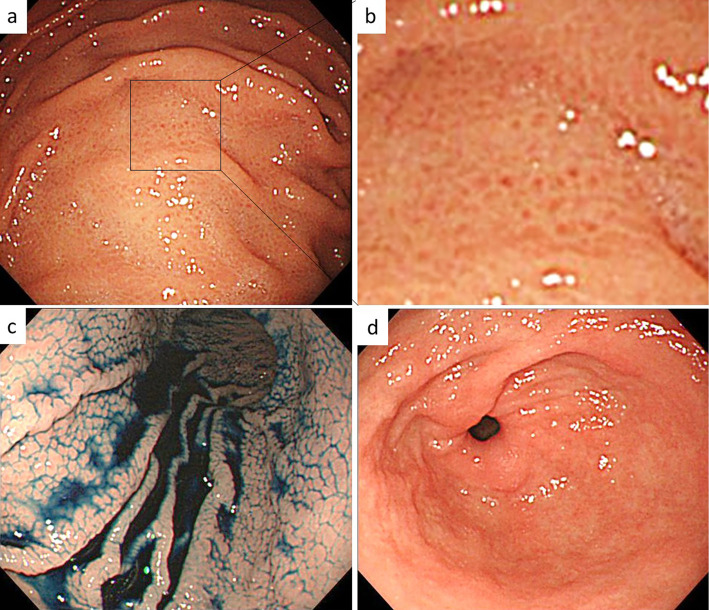

Six years later (at 41 years old), the patient underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. This endoscopic examination revealed edematous mucosa accompanied by slight swelling of the areae gastricae, with erythema restricted to the corpus (Fig. 4a, b). These findings were confirmed using the indigo carmine method (Fig. 4c). Notably, there was no swelling of the areae gastricae in the antrum (Fig. 4d). To determine the cause of gastritis in this patient, tissues were taken from the gastric corpus.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic findings in the patient in case 2. a, b) Non-atrophic mucosa, with a mosaic pattern, slight swelling of the areae gastricae, and erythema were present in the corpus. c) A mosaic pattern was clearly visible by 0.2% indigocarmine chromoendoscopy. d) Normal antrum.

A histopathological assessment revealed oxyntic mucosa with lymphocytes in deeper tissue (Fig. 5a). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated reductions in parietal cell populations (Fig. 5b, c); linear hyperplasia of ECL cells was also evident (Fig. 5d, e). An immunohistochemical analysis did not reveal H. pylori. The patient was suspected of having AIG; thus, serological examinations were performed. A serum analysis revealed a high level of gastrin (1,804 pg/mL, normal level: <200 pg/mL) and a high anti-parietal cell autoantibody titer (1:160). Serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody, fecal H. pylori antigen, and urea breath test findings were negative. These results supported a diagnosis of active AIG without complete atrophy.

Figure 5.

Histopathological findings from the corpus in the patient in case 2. a) Lymphocytes and plasma cells were evident in deeper, glandular tissue. b, c) Immunohistochemical staining for H+/K+ATPase. There were only a few remaining parietal cells (black arrows). d, e) Immunohistochemical staining for Chromogranin A. Linear ECL cell hyperplasia was evident (red arrow).

Discussion

Atrophic gastritis is a process involving chronic inflammation of the stomach gastric mucosa that leads to the loss of gastric glandular cells and their eventual replacement by intestinal and fibrous tissues (1). Typical endoscopic findings are as follows: advanced corpus dominant mucosal atrophy, hyperplastic polyps, remnant oxyntic mucosa, and sticky adherent dense mucus (6,7). These manifestations are only observed when extensive atrophy of the corpus is present (i.e., in advanced-stage AIG). Although sustained active gastritis results in atrophic gastritis, clinicians rarely observe endoscopic changes in active AIG.

In the two patients described in this report, we observed swelling of the areae gastricae that was restricted to the corpus, such that the antrum was spared. In the patient in case 1, an endoscopic examination revealed a thick, shiny mucosa on the greater curvature. On closer observation, a mosaic pattern was evident in the greater curvature of the gastric body and fundus. The lesser curvature initially appeared almost normal, but detailed observation revealed multiple depressed lines resembling gastric cracked mucosa. Notably, gastric cracked mucosa is a reported proton-pump inhibitor-associated mucosal change; a histological analysis of such mucosa has revealed parietal cell protrusion and oxyntic gland dilatation (8). In tissues taken from the lesser curvature, remnant oxyntic glands showed mild dilatation with parietal cell pseudohypertrophy. The endoscopic findings may be comparable, due to the histological similarity of parietal cell pseudohypertrophy and oxyntic gland dilatation. In this patient, tissues taken from the greater curvature exhibited a greater degree of inflammation than those from the lesser curvature.

In the patient in case 2, the swelling of the areae gastricae was slightly more obvious than in the patient in case 1, including greater prominence and erythema. Six years prior to the most recent screening, UGI-XR findings had already shown polygonal swelling of the areae gastricae restricted to the corpus, suggesting that AIG had been present at that time. These two separate imaging analyses showed minimal or no gastric mucosal changes over the course of six years. Because AIG is asymptomatic, it is difficult to determine the timing of the onset; thus far, little is known regarding the natural history of the disease. Data regarding a large number of patients is needed to clarify the natural course and interval until progression of atrophy.

It is very difficult to distinguish between H. pylori-active gastritis (9,10) and active AIG when only the corpus is observed. A careful assessment of the antrum is required to distinguish between these two types of gastritis. H. pylori gastritis is most intense in the antrum and typically develops in the corpus (11). An autoimmune reaction in which CD4+ T cells target gastric H+/K+ adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) leads to the destruction of parietal cells (12), which are unique cells in the corpus and fundus glands; therefore, swelling of the areae gastricae, a change that occurs in patients with gastritis, is observed only in the gastric body (excluding the antrum). Because of the persistent gastritis in these two patients, they are expected to eventually present with severe corpus-dominant atrophic gastritis, which is a typical endoscopic manifestation of AIG.

Recently, Kotera et al. reported that multiple reddish pseudopolyps were an endoscopic finding in patients with early-stage AIG (3). Our endoscopic findings differed from the findings of Kotera et al. In the patient in case 1, no redness was present, the areae gastricae divided by grooves were small, and the features were not suggestive of pseudopolyps. In the patient in case 2, redness was present; however, as in the patient in case 1, the areae gastricae divided by grooves were small.

Few endoscopic findings of patients with early-stage AIG have been reported thus far. A collection of reports from various institutions may be necessary to establish the common endoscopic findings of early-stage AIG. Stolte et al. reported that a histological diagnosis of AIG is possible for patients in the pre-atrophic stage of disease (8). However, unless clinicians suspect AIG, tissue sampling and serological testing are not typically performed. To avoid missing the early stages of AIG, clinicians must recognize that AIG may be present even in the absence of severe atrophic gastritis and be aware of the relevant findings.

Unfortunately, there is no curative therapy for AIG that can prevent its associated complication of pernicious anemia and subsequent progression to gastric adenocarcinoma. Prednisolone reportedly promotes remission and gastric mucosal regeneration in patients with AIG only during active therapy (13); however, this is not a practical treatment approach considering the side effects of long-term prednisolone administration. We suggest performing surveillance endoscopy at intervals of three to five years to screen for carcinoid tumors and gastric adenocarcinoma (14). We also suggest the provision of iron or vitamin B12 replacement therapy for patients with iron deficiency anemia and those with pernicious anemia.

A recently published study revealed that more than half of patients with AIG had an associated autoimmune disease (15). The inflammatory changes present in AIG can be visualized by endoscopy; if endoscopists can recognize such changes during the early stage of the disease, AIG might be accurately diagnosed prior to assessments of other autoimmune diseases.

The natural course of AIG is expected to become clearer as more descriptions of patients with early-stage AIG are published. Further case reports, follow-up, and research are needed concerning early-stage AIG.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge Hidenobu Watanabe, Special Adviser of Pathology & Cytology Laboratories, Emeritus Professor at Niigata University, for his assistance with pathology analyses. We thank Kim Rice and Ryan Chastain-Gross, Ph.D., for editing a draft of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Strickland RG, Mackay IR. A reappraisal of the nature and significance of chronic atrophic gastritis. Am J Dig Dis 18: 426-440, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Massironi S, Zilli A, Elvevi A, Invernizzi P. The changing face of chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis: an updated comprehensive perspective. Autoimmun Rev 18: 215-222, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kotera T, Oe K, Kushima R, Haruma K. Multiple pseudopolyps presenting as reddish nodular are a characteristic endoscopic finding in two cases. Intern Med 59: 2995-3000, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coati I, Fassan M, Farinati F, Graham D, Genta R, Rugge M. Autoimmune gastritis: pathologist's viewpoint. World J Gastroenterol 21: 12179-12189, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stolte M, Baumann K, Bethke B, Ritter M, Lauer E, Eidt H. Active autoimmune gastritis without total atrophy of the glands. Z Gastroenterol 30: 729-735, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Terao S, Suzuki S, Yaita H, et al. Multicenter study of autoimmune gastritis in Japan: clinical and endoscopic characteristics. Dig Endosc 32: 364-372, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park JY, Lam-Himlin D, Vemulapalli R. Review of autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc 77: 284-292, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miyamoto S, Kato M, Tsuda M, et al. Gastric mucosal cracked and cobblestone-like changes resulting from proton pump inhibitor use. Dig Endosc 29: 307-313, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kanzaki H, Uedo N, Ishihara R. Comprehensive investigation of areae gastricae pattern in gastric corpus using magnifying narrow band imaging endoscopy in patients with chronic atrophic fundic gastritis. Helicobacter 17: 224-231, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yan SL, Wu ST, Chen CH, et al. Mucosal patterns of Helicobacter pylori-related gastritis without atrophy in the gastric corpus using standard endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 16: 496-500, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kimura K. Chronological transition of the fundic pyloric border determined by stepwise biopsy of the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach. Gastroenterology 63: 584-592, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toh BH, Chan J, Kyaw T, Alderuccio F. Cutting edge issues in autoimmune gastritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 42: 269-278, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biondo M, Field J, Toh BH, Alderuccio F. Prednisolone promotes remission and gastric mucosal regeneration in experimental autoimmune gastritis. J Pathol 209: 384-391, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, et al. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy 51: 365-388, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kryssia IRC, Marilisa F, Chiara M, et al. Autoimmune diseases in autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Acta Biomed 89: 100-103, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]