Abstract

Human FOXP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells are central to immune tolerance. However, their heterogeneity and differentiation remain incompletely understood. Here we use single-cell RNA and T cell receptor sequencing to resolve Treg cells from healthy individuals and patients with or without acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) who undergo stem cell transplantation. These analyses, combined with functional assays, separate Treg cells into naïve, activated, and effector stages, and resolve the HLA-DRhi, LIMS1hi, highly suppressive FOXP3hi, and highly proliferative MKI67hi effector subsets. Trajectory analysis assembles Treg subsets into two differentiation paths (I/II) with distinctive phenotypic and functional programs, ending with the FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets, respectively. Transcription factors FOXP3 and SUB1 contribute to some Path I and Path II phenotypes, respectively. These FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets and two differentiation pathways are conserved in transplanted patients, despite having functional and migratory impairments under aGVHD. These findings expand the understanding of Treg cell heterogeneity and differentiation and provide a single-cell atlas for the dissection of Treg complexity in health and disease.

Subject terms: RNA sequencing, Mechanisms of disease, Regulatory T cells, Graft-versus-host disease, Stem-cell research

Human Treg cells are central to immune tolerance, yet their heterogeneity and differentiation remain incompletely understood. Here the authors perform single-cell RNA and T cell receptor sequencing to resolve Treg cells from healthy individuals and patients with or without acute graft-versus-host disease revealing Treg complexity in health and disease.

Introduction

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are a highly immunosuppressive population of CD4+ T cells characterized by the expression of the transcription factor forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3). Treg cells control immune responses and maintain peripheral tolerance1–4. Treg cells have been suggested to be heterogeneous. Based on cell origins, Treg cells are divided into two parts. Thymus-derived Treg (tTreg) cells develop in the thymus and make up the majority of Treg cell pool in secondary lymphoid organs. Peripheral Treg (pTreg) cells arise from conventional T (Tcon) cells at peripheral inflammation sites with the acquisition of FOXP3 expression5. Human peripheral blood (PB) CD4+FOXP3+ Treg cells are subdivided into three subpopulations: CD45RA+FOXP3lo/CD25lo resting or naïve Treg cells, CD45RA−FOXP3hi/CD25hi effector Treg cells, and CD45RA−FOXP3lo/CD25lo cells (not true Treg cells)6. Mass cytometry analysis based on 26 well-recognized Treg-associated markers identified 22 subsets7. Treg cells can also be divided into several T helper (Th) like subpopulations8. However, none of these taxonomies are dependent on the unsupervised global gene expression profile.

Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have shed new light on T cell and Treg cell heterogeneity at single-cell resolution9–13. Based on scRNA-seq, Treg cells were subdivided into six clusters in healthy human PB12, or five clusters in the human breast cancer microenvironment10. The proportions of resting and activated Treg populations in mice were reportedly not determined by T cell receptor (TCR) signaling strength, whereas the intensity of TCR signal intriguingly influenced the phenotypic and functional programs of activated Treg cells12. Treg cells also exhibited transcriptional dynamics along a continuum of tissue adaptation and presented conserved expression programs between homeostasis and disease and between mice and human13. Despite these findings, in-depth single-cell investigations on human Treg cells during steady state or disease conditions are still limited. The identity, functional/homeostatic characteristics, differentiation, and relationships of distinct Treg subsets remain incompletely understood.

Treg cells are impaired in number or function in inflammatory disorders. Typically, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a major adverse effect of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT)14. GVHD is associated with the decreased number and function of Treg cells15,16. Transfer of Treg cells has alleviated GVHD symptoms in mouse models and clinical trials17–19. However, the mechanisms underlying Treg cell defects in GVHD have not been fully addressed, at least partially due to the lack of single-cell omics analysis.

In this work, we use scRNA-seq and single-cell TCR (scTCR)-seq to analyze Treg cells in PB and bone marrow (BM) from healthy donors and allo-HSCT patients with or without acute GVHD (aGVHD). Heterogeneous Treg cell subpopulations are resolved. Their transcriptional signatures, phenotypic markers, and functional and homeostasis programs are defined. In addition, two Treg cell differentiation pathways are identified, and their characteristics and transcription factors are defined. Moreover, Treg cells from allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD are also analyzed at the single-cell level, which provide further insight into the conservation and change of Treg cell dynamics under disease conditions.

Results

scRNA-seq resolves distinctive subsets among human FOXP3+ Treg cells

We firstly conducted scRNA-seq on Treg cells from healthy donors and allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD. scRNA-seq was performed using the 10× Genomics Chromium platform to analyze CD4+CD25+CD127− Treg20,21 and CD4+CD25− conventional T (Tcon) cells sorted from PB and BM of healthy donors and allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a–c, Supplementary Data 1). Consistent with a previous study12, not all CD4+CD25+CD127− cells had FOXP3 reads due to potential non-Treg cell contamination and limited gene coverage in scRNA-seq (Supplementary Fig. 1d). To reduce the contamination of non-Treg cell populations, FOXP3+ cells were selected for subsequent analyses. The 43,178 FOXP3+ Treg cells and 3,138 CD4+FOXP3− Tcon cells were analyzed and they had an average of 1331 genes per cell (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f, Supplementary Data 2). The Treg identity of these FOXP3+ cells was confirmed by their enriched expression of canonical Treg marker genes including FOXP3, IKZF2, TIGIT, IL2RA, IL10RA and CTLA4 (Supplementary Fig. 1g, Supplementary Data 3)3,4.

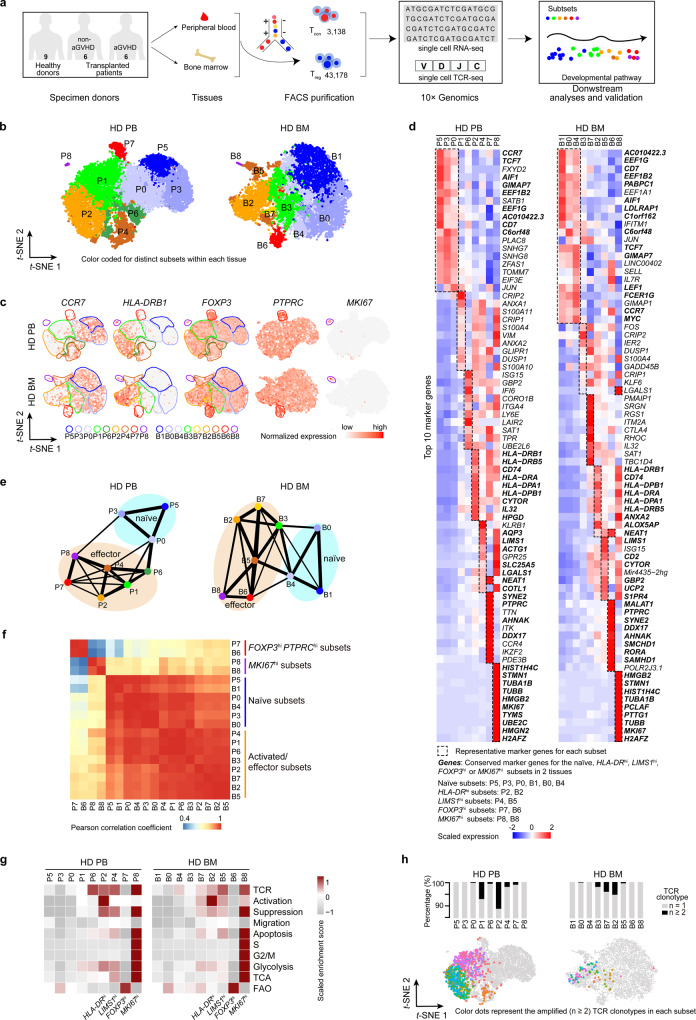

Fig. 1. ScRNA-seq and TCR-seq reveals distinctive subsets among human FOXP3+ Treg cells.

a A scheme showing the overall strategy of this study. b t-SNE of single-cell transcriptomes of Treg cells from healthy donor (HD) peripheral blood (PB, n = 8) and bone marrow (BM, n = 6) samples, colored by subsets. Each subset was numbered and labeled with the first letter (s) of the tissue name (P0 for cluster 0 in peripheral blood, etc.). c Projection of CCR7, HLA-DRB1, FOXP3, PTPRC and MKI67 expression onto the t-SNE plot. d Heatmaps showing the top 10 (by fold change) marker genes for each subset, excluding the ribosomal and mitochondrial genes. Scaled expression means the gene expression was centered and scaled among subsets. The fold change means the values of normalized expression of genes in a specific subset compared to the normalized expression of genes in the other subsets. e Partition graph abstraction (PAGA) analysis. Nodes represent subsets, and thicker edges indicate stronger connectedness between subsets. f Correlograms visualizing the correlation of single-cell gene expression profiles between subsets from HD PB and HD BM. g Heatmaps showing the GSVA enrichment score of Treg cell feature pathways for each subset. h The amplified (n ≥ 2) TCR distribution of Treg cells across different subsets, colored by TCR clonotypes. The insert pictures show the composition of unique and amplified (n ≥ 2) Treg cell TCR clonotypes in each subset. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The heterogeneity of healthy donor Treg cells was assessed. Cell clusters were identified based on the shared nearest neighbor (SNN) clustering algorithm in Seurat22 and visualized through t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) or Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) analysis. Finally, nine clusters in PB and BM Treg cells from healthy donors were defined (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2a). According to previously defined markers of naïve and effector Treg cells, including CCR7, HLA-DR, and FOXP323–25, and the top 10 signature genes and signature transcription factors of each cluster (Fig. 1c, d, Supplementary Fig. 2b–f, Supplementary Data 4), clusters 0, 3, and 5 in PB (P0, P3, P5) and clusters 0, 1, and 4 in BM (B0, B1, B4) perfectly matched naïve status with CCR7hiTCF7hiHLA-DRlowFOXP3low profile. These clusters were termed naïve subsets. The others were activated/effector subsets. They featured negative or low expression of CCR7. In addition, the partition-based graph abstraction (PAGA) mapping revealed high connectivity among the naïve clusters, and among the activated/effector clusters (Fig. 1e). To better resolve these activated/ effector subsets, we performed a further annotation. Among them, clusters 2 in PB and BM (P2, B2) exhibited high expression of HLA-DR and were named as HLA-DRhi subsets. The expression of LIMS1 was high in clusters 4 and 8 in PB (P4, P8) and clusters 5 and 8 in BM (B5, B8). Among these clusters, P4 and B5 were designated LIMS1hi subsets. Cluster 7 in PB (P7) and cluster 6 in BM (B6) were highly similar in transcriptome signature and had the FOXP3hiPTPRChiDDX17hi profile. P7 and B6 were designated FOXP3hi effector subsets. Cluster 8 in PB (P8) and cluster 8 in BM (B8) were very similar, both of them had an MKI67hi TUBBhiHMGB2hi profile and the maximal proportion of cells in the S + G2/M phase (Supplementary Fig. 3a). P8 and B8 were designated MKI67hi effector subsets. Although the FOXP3hi and MKI67hi Treg cell subsets were highly conserved across PB and BM, they also showed tissue-specific gene expression differences (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 3b, Supplementary Data 5). These differences might have been caused by the distinctive tissue microenvironment. Treg subsets also displayed disparate expression of signature transcription factors (Supplementary Fig. 2f). There were more naïve Treg cells in BM than those in PB, although there was no significant difference (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The naïve and effector Treg cell markers suggested by Treg cell scRNA-seq studies12,13 were also enriched in our defined naïve and activated/effector subsets, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). Thus, based on unsupervised clustering, we identified several distinct human Treg cell subsets under steady-state conditions.

To compare the functional/homeostatic features among different clusters, gene set variation analysis (GSVA)26,27 was performed (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Data 6). GSVA showed a gradual increase in TCR signaling, activation, and suppressive function from naïve to activated/effector subsets. The MKI67hi subsets had the highest expression of TCR signal, suppression, apoptosis, cell cycle (S, G2/M), glycolysis, and tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) gene sets. The FOXP3hi subsets were characterized by low TCR signal and glycolysis, intermediate suppression, and high fatty acid oxidation (FAO) gene sets. The HLA-DRhi subsets exhibited the highest degree of activation. Further examination of individual genes indicated that suppression and migration genes were selectively expressed by different subsets (Supplementary Fig. 3f). Particularly, the HLA-DRhi subset strongly expressed TGFB1, CCR3 and CCR10. The LIMS1hi subset highly expressed IL10 and CCR9. The FOXP3hi subset highly expressed IL2RA, CTLA4, CCR4, CXCR4 and SELL. The MKI67hi subset highly expressed LGALS1 and ITGAE.

scTCR-seq reveals amplification and transition among Treg cells subsets

TCRs are uniquely expressed by individual Treg cell clones28,29. To trace the amplification history of a single Treg clone, scRNA-seq and paired scTCR-seq were performed simultaneously in 11,830 sorted FOXP3+ Treg cells and 1,519 sorted Tcon cells (Supplementary Data 7). This approach allowed direct mapping of gene expression to TCR in the same cell. Most amplified TCR clonotypes (n ≥ 2) were detected in activated/effector subsets such as HLA-DRhi and LIMS1hi effector subsets. No or very few cells from naïve, FOXP3hi, or MKI67hi subsets harbored clonally amplified TCRs (Fig. 1h). We also identified a total of 250 and 27 TCR clonotypes that were shared by cells from at least two different clusters in PB and BM, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3g). Most TCRs were shared between activated/effector subsets, suggesting frequent differentiation between them. Although either FOXP3hi subset or MKI67hi subset had shared TCR clonotypes with other subsets, there was no shared clonotype between FOXP3hi subset and MKI67hi subset, which might be due to their distinctive development or the limited cell number. The latter would not be sufficient to capture the same TCR (many TCR clonotypes are present in vivo). In addition, 121 TCR clonotypes were shared between PB and BM Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 3h). The TCRs shared between tissues were presented in most subsets, except P5 (naïve), P3 (naïve), P8 (MKI67hi), and B8 (MKI67hi). Therefore, P5 and P3 may be at the most naïve status that were only present in PB. MKI67hi subsets might differentiate independently in PB or BM. However, the lack of shared TCRs between PB and BM MKI67hi subsets may have been caused by a relatively small cell number of analyzed cells. These results collectively indicated a process of naïve to activated and effector differentiation, defined as the transition between individual Treg subsets in one tissue or between two tissues. However, we could not determine the order of Treg cell development between different tissues. Further studies are necessary.

In vitro assay of Treg subsets

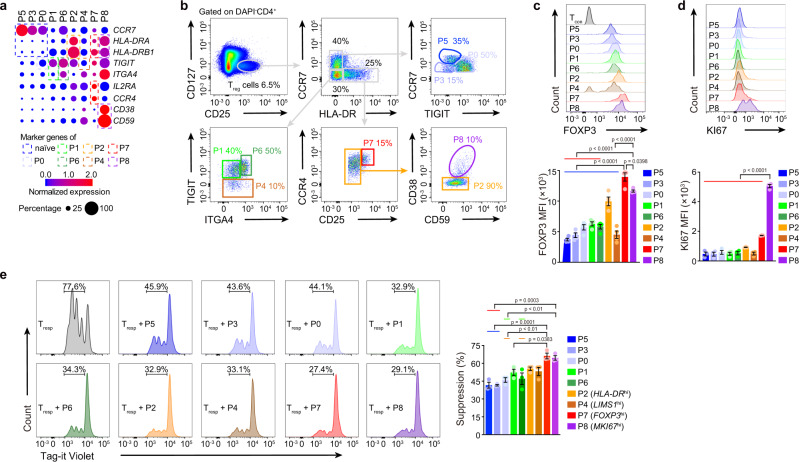

To evaluate the functional and homeostatic characteristics of Treg subsets in vitro, cell surface marker candidates for different clusters were identified (Fig. 2a), and clusters from PB were isolated by flow cytometry sorting (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Figs. 4a, 12a, f). Cells in the FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets were the largest and displayed the highest expression of FOXP3 and KI67 proteins, respectively (Fig. 2c, d, Supplementary Figs. 4b, 12a). The FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets exhibited the strongest inhibition of responder T (Tresp) cell proliferation, followed by LIMS1hi and HLA-DRhi subsets and then by other activated/effector subsets (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). MKI67hi and LIMS1hi subsets proliferated more than other activated/effector subsets after stimulation (Supplementary Figs. 4c, 12a, c). Activated/effector subsets had a slightly higher apoptosis rate than most naïve subsets during culture (Supplementary Figs. 4d, 12a, c). Surprisingly, a large proportion of cultured LIMS1hi subset cells lost the FOXP3 protein (Supplementary Figs. 4e, 12a, c). The LIMS1hi subset rarely expressed Helios (encoded by IKZF2) (Supplementary Figs. 4f, 12a), which is considered a potential marker of thymus-derived Treg cells30. Although, the LIMS1hi subset shared a number of TCRs with activated/effector Treg subsets but not with Tcon cells (Supplementary Fig. 4g), it still could not determine whether LIMS1hi subset were converted from Tcon cells or not. The collective in vitro findings further defined the functional and homeostatic characteristics of Treg subsets previously resolved with single-cell transcriptomics.

Fig. 2. In vitro assay of Treg cell subsets.

a Dot plots showing the expression of indicated genes in each subset. b Gating strategy for HD PB Treg cell subset sorting. c, d Flow cytometry and its quantification of FOXP3 (n = 4) and KI67 (n = 3) in each HD PB Treg cell subset from PBMC. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. In c, blue line indicated that P7 was compared with P5, P3, P0, P1, P6, P2 or P4; red line indicated that P8 was compared with P5, P3, P0, P1 or P6. In d, red line indicated that P8 was compared with P5, P3, P0, P1, P6, P2, P4 or P7. e In vitro suppression assay. Tag-it Violet-labeled Tresp cells were co-culture with different Treg subsets for 96 h, with CD3/CD28 T cell activator (n = 3). The Treg: Tresp ratio was 1: 2. The Tag-it Violet dilution of Tresp cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Blue line indicated that P7 was compared with P5 or P3; orange line indicated that P7 was compared with P0 or P6; red line indicated that P8 was compared with P5 or P3; green line indicated that P8 was compared with P0 or P6. In c-e, experiment repeated at least three times; p values were determined by One-way ANOVA, part of the statistical significance was shown in the pictures and the whole ANOVA results were given in Supplementary Data 11; data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Two effector differentiation paths revealed by pseudotime analysis

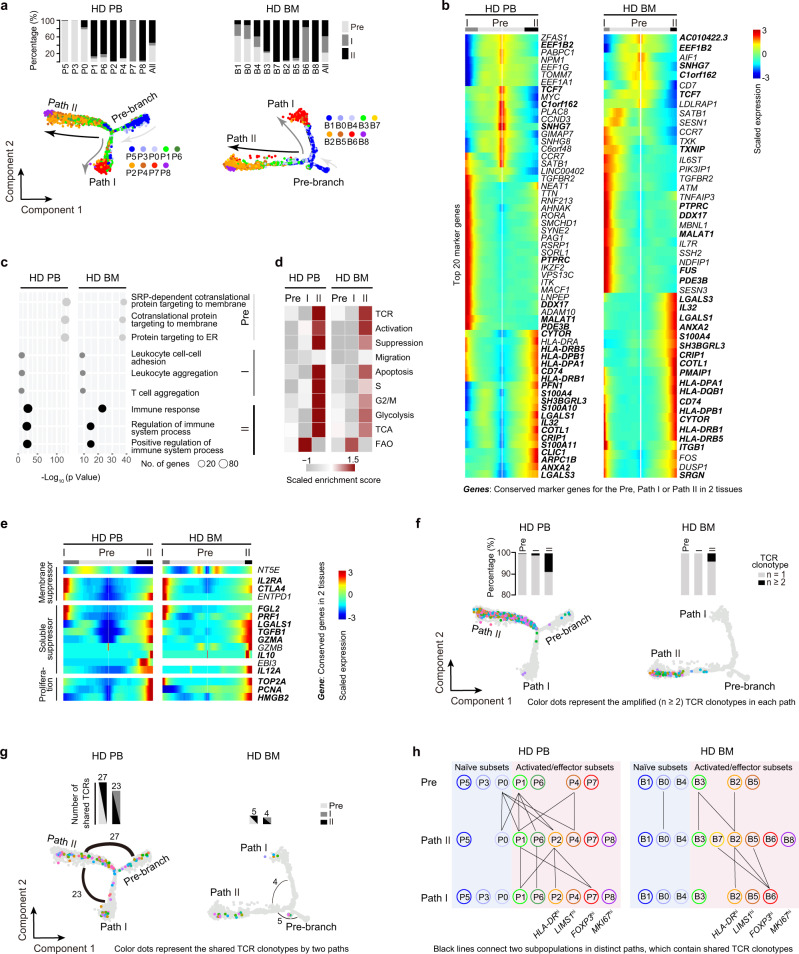

To delineate the hierarchy and development relationship between subsets, pseudotime analysis31 was performed. The findings unexpectedly revealed two effector differentiation pathways (termed Path I and II) in both PB and BM (Fig. 3a). Signature genes for Pre-branch (such as TCF7, EEF1B2, C1orf162, and SNHG7), Path I (such as PTPRC, DDX17, MALAT1, and PDE3B), and Path II (such as HLA-DR, LGALS1/3 and CD74) were identified (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Data 8). Correlation analysis suggested a conservation between PB and BM of Pre-branch and Path II, but not of Path I (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Different clusters merged into a process in pseudotime that started with naïve subsets (mostly in the Pre-branch), followed by activated/effector subsets, and ending with the FOXP3hi subset (Path I) or MKI67hi subset (Path II) (Fig. 3a, bottom, Supplementary Fig. 5b). Even cells within the same subsets could be distributed into the two paths, indicating that this bifurcated differentiation is a dominant rule (Fig. 3a, top). There were some overlapping marker genes between the FOXP3hi subset and Path I, or between the MKI67hi subset and Path II, consistent with the FOXP3hi subset as the terminus of Path I and the MKI67hi subsets as the terminus of Path II (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Gene Ontology analysis showed that, in both PB and BM, Pre-branch-enriched genes were associated with translation and protein targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Path I-enriched genes were related to cell-cell adhesion and cell aggregation, and Path II-enriched genes played roles in response to immune system processes (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 5d, e, Supplementary Data 9). GSVA indicated that Path II cells expressed higher TCR, activation, suppression, migration, apoptosis, S and G2/M gene sets than did Path I cells (Fig. 3d). Path I cells preferentially expressed FAO gene sets, and Path II cells predominantly expressed glycolysis and TCA gene sets (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3. Pseudotime analysis and scTCR analysis defines two differentiation paths.

a Pseudotime trajectory of Treg cells within distinct tissues, colored by subsets. The insert picture shows the proportions of different Treg cell paths in each cell subset (HD PB: n = 5, HD BM: n = 3). b Pseudotemporal gene-expression profiles of the top 20 (by fold change) marker genes for each path, excluding the ribosomal and mitochondrial genes. c Representative terms from Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed genes for each Treg cell path. d Heatmaps showing the GSVA enrichment score of Treg cell feature pathways for each different path. e Pseudotemporal gene-expression profiles of suppression and proliferation-associated genes in the Treg cell paths. f The amplified TCR distribution of Treg cells across different paths, colored by TCR clonotypes. The insert pictures show the composition of unique and amplified (n ≥ 2) Treg cell TCR clonotypes in each path. g The shared TCR distribution of Treg cells between any two paths, colored by TCR clonotypes. The thickness of the black solid lines representing the relative numbers of shared TCRs. The insert pictures show the numbers of TCRs shared by two paths. h The shared TCR distribution of Treg cells between any two subpopulations in different paths. The black lines connected two subpopulations, which contained shared TCRs. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Inspecting of individual genes revealed that the Path I terminus highly expressed the critical membrane-associated suppressor genes IL2RA and CTLA4 and soluble suppressor genes FGL2 and PRF1. The Path II terminus highly expressed the soluble suppressor genes LGALS1, TGFB1, GZMA, IL10, and IL12A and the proliferation genes TOP2A, PCNA, and HMGB2, with a slightly higher proportion of S + G2/M cells (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 6a).

TCR analyses revealed that most of the amplified TCR clonotypes were in Path II cells (Fig. 3f, Supplementary Data 7), corroborating the high glycolysis-proliferation gene signature. Shared TCRs were mostly observed between Pre-branch and Path II and between Path II and Path I, indicating a dominant differentiation from Pre-branch to Path II and the transition between Path II and Path I cells (Fig. 3g). A more detailed analysis of TCR overlap indicated that most Path I HLA-DRhi and FOXP3hi subset of cells might be derived from the Path II HLA-DRhi subset. While Path II MKI67hi subset did not transit into Path I cells (Fig. 3h), suggesting that the MKI67hi subset was probably a distinctively developed subpopulation.

In vitro assay of two differentiation Paths

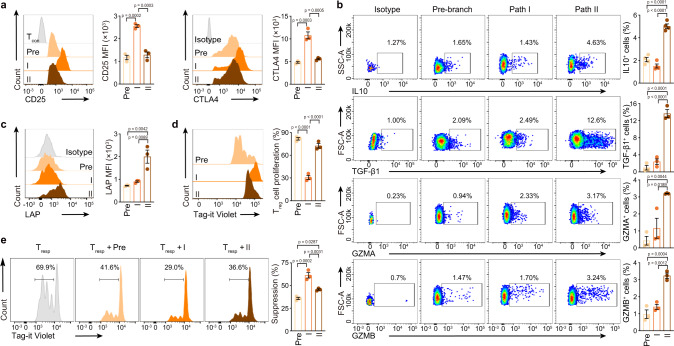

The surface markers of different paths were identified to validate the properties of the two paths (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c, Supplementary Data 8). In vitro assays were performed after isolation of Path I and II cells by flow cytometry: Pre-branch as CCR7+, Path I as CCR7−CCR4med/hi, Path II as CCR7−CXCR3+ (Supplementary Figs. 6d, 12a). Path I cells expressed more CD25 and CTLA4 proteins, whereas Path II cells expressed more IL10 and TGF-β1 proteins (Fig. 4a, b, Supplementary Fig. 12a, d). However, the expression of GZMA, GZMB, and LAP (the N-terminal dimer of latent TGF-β1)32 proteins were overall very low and only marginally different between Path II and Path I cells (Fig. 4b, c, Supplementary Fig. 12a, d). Path I cells had stronger suppressive but weaker proliferative capacity than Path II and Pre-branch cells in vitro (Fig. 4d, e, Supplementary Fig. 12a–c). Path II cells displayed lower expression of FOXP3 protein than Path I cells, and were slightly larger in size than Pre-branch and Path I cells (Supplementary Figs. 6e, f, 12a, c). Thus, single-cell transcriptomics in combination with functional assays defined two effector differentiation paths in Treg cells.

Fig. 4. In vitro assay of Treg cell paths.

a−c Flow cytometry and its quantification of the indicated proteins in each HD PB Treg cell path (CD25: n = 3, CTLA4: n = 3, IL10: n = 4, TGF-β1: n = 3, GZMA: n = 3, GZMB: n = 3, LAP: n = 3). d The proliferation of HD PB Treg cell paths. The Tag-it Violet dilution of Treg cells were assessed by flow cytometry, after 96 h in vitro culture (n = 3). e In vitro suppression assay (n = 3). Tag-it Violet-labeled HD PB Tresp cells were co-cultured with different HD PB Treg cell paths for 96 h with CD3/CD28 T cell activator. The Treg: Tresp ratio was 1: 2. The Tag-it Violet dilution of Tresp cells were assessed by flow cytometry. In a–e, experiment repeated at least three times; p values were determined by One-way ANOVA; data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

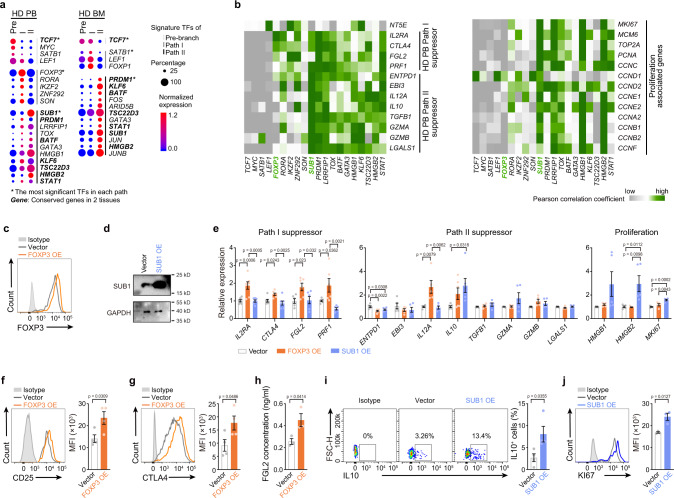

Transcription factors enriched in two differentiation paths

To understand the transcription factor basis of bifurcated differentiation, the signature transcription factors were identified for each path in PB Treg cells. TCF7, FOXP3, and SUB1 were the most significant signature transcription factors in Pre-branch, Path I, and Path II cells from PB, respectively (by p value, Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 6g). PB-BM conservations were evident in the enrichment of TCF7 in the Pre-branch and SUB1 and HMGB2 in Path II (Fig. 5a). Single-cell correlation analysis indicated that FOXP3 was preferentially co-expressed with Path I-associated suppressor genes IL2RA, CTLA4, and FGL2 within individual cells, whereas SUB1 was frequently co-expressed with Path II-associated suppressor genes EBI3, IL12A, IL10, TGFB1, GZMA, GZMB, and LGALS1 and with the proliferative genes MKI67, MCM6, TOP2A, PCNA and CYCLINs in healthy donor PB (Fig. 5b). A similar gene correlation pattern was observed in the BM (Supplementary Fig. 6h).

Fig. 5. Transcription factors enriched in Treg cell differentiation paths.

a Dot plots showing the transcriptional factors (TFs) which were differently expressed in each Treg cell path (p < 0.05, log FC > 0.28), ordered by p value. The dot size represents the percentage of cells that express the indicated genes, and the dot color shows the averaged level of expression. FC: fold change. b Correlograms visualizing the correlation of single-cell gene expression profiles between TFs and suppression or proliferation genes in HD PB samples. c FOXP3 protein levels in HD PB Treg cells, 5 days after transfection with FOXP3 overexpression virus, as measured by flow cytometry. Experiment repeated at least three times. d SUB1 protein levels in HD PB Treg cells, 5 days after transfection with SUB1 overexpression virus, as measured by western blot. Experiment repeated three times. e Expression of the mRNA level of indicated genes in HD PB Treg cells, 5 days after transfection with FOXP3 or SUB1 overexpression virus, as measured by RT-qPCR (n = 5–7). Experiment repeated at least three times. f–j Expression of CD25, CTLA4, FGL2, IL10 and KI67 in HD PB Treg cells, 5-6 days after transfection with FOXP3 or SUB1 overexpression virus, as measured by flow cytometry (f, g, i, j) or ELISA (h) (CD25: n = 4, CTLA4: n = 4, FGL2: n = 3, IL10: n = 4, KI67: n = 3). Experiment repeated three times. In e, p values were determined by One-way ANOVA; In f–j, p values were determined by two-sided unpaired t-test; data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine whether FOXP3 and SUB1 contribute to the Path I and II features, gain-of-function experiments were performed using Treg cells that overexpressed FOXP3 or SUB1. FOXP3 and SUB1 were successfully overexpressed in Tcon and Treg cells by infection with recombinant lentivirus (Fig. 5c, d, Supplementary Figs. 7a–d, 12d, e). FOXP3 overexpression increased IL2RA, CTLA4, FGL2, PRF1, and IL12A mRNA levels. SUB1 overexpression increased IL10, HMGB2, and MKI67 mRNA levels in Treg cells (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 12e). The expression of some genes was confirmed at the protein level. FOXP3 overexpression slightly increased the level of CD25, CTLA4, and FGL2 proteins in Treg cells. SUB1 overexpression increased the level of IL10 protein and slightly increased KI67 protein Treg cells (Fig. 5f–j, Supplementary Fig. 12d, e). The levels of PRF1 and IL12 p35 were overall low in Treg cells and not significantly affected by FOXP3 overexpression (Supplementary Figs. 7e, f, 12d, e). FOXP3 overexpression also significantly promoted the RNA and protein levels of CD25 and CTLA4 in Tcon cells, consistent with a previous report33 (Supplementary Figs. 7g, h, 12d, e). Some other genes that changed after FOXP3/SUB1 overexpression in Tcon cells were not significantly altered in Treg cells (Supplementary Figs. 7g, 12e), suggesting that these transcription factors may have cell type-dependent functions. These results collectively indicated the possible contribution of FOXP3 and SUB1 to the features of the two paths. However, the changes in some genes were slight after FOXP3 and SUB1 overexpression, suggesting that other transcription factors may also be involved, which warrant further study.

Treg subsets in allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD

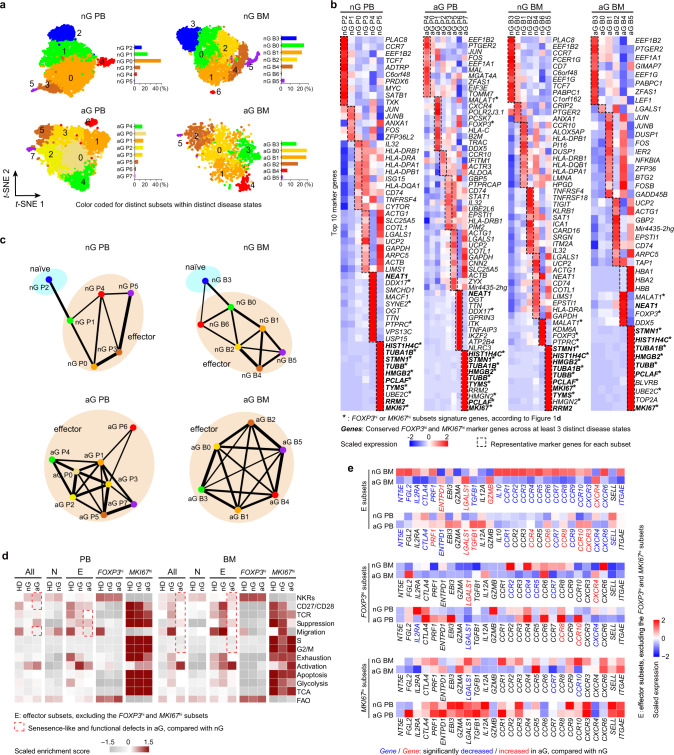

Treg cells are largely regenerated after allo-HSCT, but their function and number are impaired if complicated with aGVHD (Supplementary Fig. 8a)15,34–36. To understand the disturbance of Treg subsets and pathways under this pathological condition, scRNA-seq was used to explore FOXP3+ T cells from the PB and BM of allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD (Supplementary Data 1). Chimerism analyses showed early reconstitution of donor T cells (> 96%, Supplementary Data 1). Treg subsets were resolved and compared with healthy donor Treg atlas, which revealed that naïve subsets (non-aGVHD P2, non-aGVHD B3), FOXP3hi subsets (non-aGVHD P4, aGVHD P6, non-aGVHD B6, aGVHD B4) and MKI67hi subsets (non-aGVHD P5, aGVHD P7, non-aGVHD B5, aGVHD B5) were present in allo-HSCT patients regardless of primary diseases (Fig. 6a–c, Supplementary Fig. 8b–d, Supplementary Data 4). Other effector clusters in allo-HSCT patients were not highly correlated with any effector clusters in healthy donors, indicating that dramatic changes occurred in effector subpopulations after allo-HSCT. Compared with healthy donors, allo-HSCT patients without aGVHD displayed reduced naïve Treg cells, whereas aGVHD patients almost completely lost naïve Treg cells (Fig. 6a–c, Supplementary Fig. 8e). In the BM, the MKI67hi subset was expanded up to 3% in non-aGVHD patients (non-aGVHD B5), but was decreased to < 1% (aGVHD B5) in aGVHD patients (Fig. 6a). These results indicated that FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets still preserved their identity, but other effector Treg cells had undergone dramatic alterations after allo-HSCT.

Fig. 6. Treg subsets in allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD.

a t-SNE of single-cell transcriptomes of Treg cells from allo-HSCT patients, numbers denote subsets. The insert histograms denote the percentage of each subset within specific patients. nG PB/BM, PB/BM samples from non-aGVHD patients; aG PB/BM, PB/BM samples from aGVHD patients (nG PB: n = 5, nG BM: n = 4, aG PB: n = 6, nG BM: n = 3). b Heatmaps showing the top10 (by fold change) marker genes for each subset, excluding the ribosomal and mitochondrial genes. c Partition graph abstraction (PAGA) analysis. Nodes represent clusters, and thicker edges indicate stronger connectedness between clusters. d Heatmaps showing the GSVA enrichment score of selected pathways for each subset. e Heatmaps showing the expression of migration and suppression-associated genes in different Treg cell subsets. The blue font indicated that the genes were significantly down-regulated in aGVHD patients, compared with non-aGVHD patients (p < 0.05). The red font indicated that the genes were significantly up-regulated in aGVHD patients, compared with non-aGVHD patients (p < 0.05). In e, gene normalized expressions were used and p-values were determined by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

GSVA analysis of Treg subsets indicated that the effector Treg subsets from non-aGVHD patients had slightly higher expression of suppression-associated genes than those from healthy donors (Fig. 6d). Even though FOXP3hi or MKI67hi subsets seemed to be comparable between non-aGVHD and aGVHD conditions, other effector Treg cells from PB and BM of aGVHD patients displayed lower expression of suppression-, migration-, and TCR-associated gene sets, compared with the non-aGVHD patients (Fig. 6d). In the BM of aGVHD patients, the effector Treg subsets (excluding the FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets) displayed a senescence-like defect characterized by high expression of natural killer cell receptors (NKRs) and lower expression of CD27/CD2837–39 (Fig. 6d). These defects were not associated with an exhausted phenotype (Fig. 6d). As the aGVHD patients in this study were relatively older than non-aGVHD patients (Supplementary Fig. 8f), the senescence-like defect might be attributed to the age of aGVHD patients.

Examination of individual genes related to suppression and migration revealed that effector Treg cells (excluding the FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets) from non-aGVHD patients had higher levels of IL2RA, ENTPD1, EBI3, LGALS1, and CCR1/3/5 than with those from healthy donors (Supplementary Fig. 9). FOXP3hi or MKI67hi subsets displayed few genes that were differentially expressed between non-aGVHD and aGVHD conditions (Fig. 6e). Effector Treg cells from aGVHD patients had lower levels of NT5E, CTLA4, CCR1, CCR7, CCR9, and CXCR6 than those from non-aGVHD patients (Fig. 6e). In addition, lower levels of other genes such as FGL2, IL2RA, PRF1, TGFB1, IL10, CCR2-6/8/10, CXCR3, and ITGAE in BM effector Treg cells were found in aGVHD patients than in non-aGVHD patients (Fig. 6e), indicating severe defects in BM Treg cells. These results suggested that the FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets were stable populations in allo-HSCT patients regardless of aGVHD, whereas the other effector subsets underwent dramatic changes in frequency, signature, and function under allo-HSCT and aGVHD conditions.

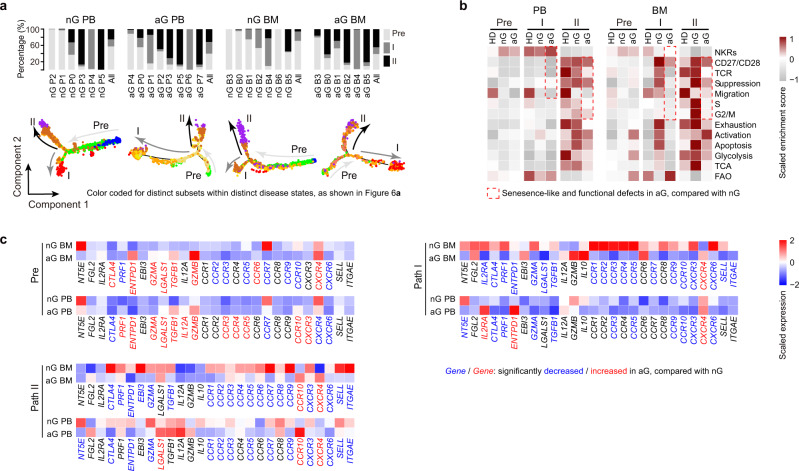

Treg paths in allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD

Treg cells from allo-HSCT patients preserved the two differentiation paths, mostly with the FOXP3hi subset at the Path I terminus (except non-aGVHD BM), and with the MKI67hi subset at the Path II terminus (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Fig. 10a, Supplementary Data 8). Allo-HSCT patients also expressed high levels of suppressor genes LGALS1 and cell cycle genes TOP2A, PCNA, and MCM6 in Path II, and expressed high levels of suppressor genes IL2RA, CLTA4, and FGL2 in Path I, similar to healthy donor Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 10b). GSVA demonstrated that in allo-HSCT patients, Path II still had higher TCR signaling, suppression, migration, cell cycle, apoptosis, glycolysis, and TCA than Path I, similar to the observations in healthy donors (Fig. 7b). These results suggested that the two-path differentiation modes were preserved in allo-HSCT patients regardless of aGVHD.

Fig. 7. Treg Paths in allo-HSCT patients with or without aGVHD.

a Trajectory analysis for Treg cell clusters in allo-HSCT patients, colored by subsets (nG PB: n = 3, nG BM: n = 3, aG PB: n = 4, nG BM: n = 3). The insert picture shows the proportions of different Treg cell paths in each subset. b Heatmaps showing the GSVA enrichment score of selected pathways for each Treg cell path. c Heatmaps showing the expression of migration and suppression-associated genes in Treg Paths. The blue font indicated that the genes were significantly down-regulated in aGVHD patients, compared with non-aGVHD patients (p < 0.05). The red font indicated that the genes were significantly up-regulated in aGVHD patients, compared with non-aGVHD patients (p < 0.05). In c, gene normalized expressions were used and p values were determined by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

There were also alterations in the paths after allo-HSCT. Compared with healthy donors, non-aGVHD patients had higher levels of IL2RA, ENTPD1, GZMA, LGALS1, CCR3, CCR5, and CXCR6, and lower levels of CCR7, in Pre-branch, Path I, and Path II. These findings might suggest a general Treg functional activation after allo-HSCT (Supplementary Fig. 10c). GSVA analysis revealed that, compared with non-aGVHD patients, aGVHD patients displayed senescence-like defects and reduced suppression and migration capacity (Fig. 7b) in both Path I and Path II. Examination of the individual genes revealed that, compared with non-aGVHD patients, aGVHD patients expressed lower levels of CCR7 and CXCR6 in Pre-branch, lower levels of CTLA4, PRF1, GZMA, TGFB1, CCR3, CCR5, CCR9, CCR10, CXCR3, and CXCR6 in Path I, and lower levels of CTLA4, ENTPD1, GZMA, CCR1/2/3/5/7/9, CXCR3, CXCR6, SELL, and ITGAE in Path II (Fig. 7c). These results suggested that aGVHD Treg cells have displayed path-specific defects in suppression and migration.

Discussion

Multi-faceted investigations of Treg heterogeneity have revealed diverse classifications, which largely improved the knowledge of Treg cells and potential clinical benefits. The present single-cell transcriptome-based exploration of human Treg cells from healthy donors and stem cell transplanted patients corroborates previous findings and brings some fresh insights into Treg cell biology. We resolved healthy donor PB and BM Treg cells into nine subsets continuously spanning naïve and activated/effector stages. Among them, FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets were highlighted. The FOXP3hi subset had the highest expression of FOXP3 and IL2RA. The MKI67hi subset was characterized by high proliferation-associated genes. FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets had the strongest suppressive capacity, suggesting that they might be important in vivo despite their limited numbers. Although the FOXP3hi subset did not exhibit a remarkably higher score than other effector subsets in GSVA analysis based on all suppressor genes, it expressed the highest levels of IL2RA and CTLA4 (in PB), which are two critical mediators of Treg suppressor function3 and might account for its superior suppressive capacity. Compared with the highly conserved FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets, the overall signature of the HLA-DRhi or LIMS1hi subsets were less conserved between PB and BM. The HLA-DRhi subset displayed the highest degree of activation, which has been described previously40. The LIMS1hi subset lost FOXP3 expression when cultured in vitro, but this result could be more or less affected by the presence of FOXP3-negitive cells in this sorted Treg cell subset (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Unexpectedly, in our study, LIMS1hi cells still retained strong suppression ability (Fig. 2e), probably due to FOXP3-independent mechanisms or because the residual FOXP3+ cells can still exert a strong suppressive effect. The LIMS1hi subset somehow resembled the inducible murine Treg cells mentioned in a previous study41. The findings of a recent study that used scRNA-seq to map umbilical cord blood Treg cells in an inflammatory setting and suggested that the TIGIT− subset was sensitive to IL6 and developed an “unstable” Treg identity42. This subset is similar with the LIMS1hi subset in terms of low expression of TIGIT (Supplementary Fig. 11a). However, there was no evidence in the current study concerning whether the human LIMS1hi cells were induced or unstable Treg cells. The relationship between our LIMS1hi subset and the previously described TIGIT− subset in literature awaits future study. In a previous study using mass cytometry, 22 Treg subpopulations were identified in the PB of human7. The CD45RA+CCR4−CD31+, CXCR3+CD38lowICOSlow, and CXCR3−CD38+ subpopulations in their study were similar to our naïve subsets (P0, 3, 5), P6 effector subset, and P4 effector subset, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 11b). However, as mRNA levels may not always be consistent with protein levels, a very strict comparison is difficult. Future analysis of protein and mRNA in the same cells may clarify the relationship between the identified subpopulations in different studies.

Our results also reveal two disparate differentiation pathways in Treg cells. Path I had high expression of CD25 and CTLA4, and genes associated with FAO and was termed as the FOXP3hi subset. In contrast, Path II had high expression of IL10 and TGF-β1, and genes associated with glycolysis and proliferation and was termed as the MKI67hi subset. Intriguingly, even cells within the same effector cluster could be divided into two paths, suggesting that the bifurcated differentiation is a dominant rule that governs Treg cells. Single-cell TCR analysis can provide in-depth information about Treg cell differentiation. A previous single-cell analysis indicated the close relationship of mouse Treg cells with shared TCRs12. Presently, high-frequency TCR clonotypes were mainly detected in activated/effector Treg cells, suggesting that the acquisition of the activation/effector phenotype requires clonal expansion. Effector Treg subsets had the highest numbers of overlapping TCR clonotypes, suggesting their frequent transition. Surprisingly, the FOXP3hi and MKI67hi subsets had hardly any overlapping clonotypes, and the MKI67hi subset did not contain repeated TCRs. This may reflect their distinct developmental mode or be attributed to the few cells that were collected. Overlapping TCR clonotypes were abundant between Pre-branch and Path II and between Path II and Path I but were rare between Pre-branch and Path I, suggesting a probable differentiation route from Pre-branch to Path II and the transition between Path II and Path I cells. However, we should not rule out the possibility of differentiation from Pre-branch to Path I. We also explored the transcription factors that may contribute to Path I or Path II phenotype. Notably, the Path I cells displayed high expression of FOXP3, whereas Path II cells displayed high expression of SUB1. Overexpression of FOXP3 and SUB1 slightly but repeatedly promoted the expression of some Path I- and Path II-associated suppressive genes, respectively, suggesting they may be involved in promoting Path I and Path II phenotypes. However, after FOXP3 and SUB1 overexpression, the gene expression changes were mostly slight, suggesting that the Path I and Path II phenotypes may also be regulated by many other transcription factors that are enriched in Path I and Path II cells. This needs to be further investigated.

Treg cell differentiation has been extensively explored. A recent report indicated that human Treg cells may simulate Th cell differentiation mechanisms and can be divided into Th1, Th17, Th1/17, Th2, and Th22-like subpopulations8. Our data suggested that the FOXP3hi subset expressed some genes associated with Treg2-like cells, whereas the MKI67hi subset expressed some genes associated with Treg1-like cells (Supplementary Fig. 11c). However, other subsets had more complex features and did not fit well with obvious Th-like gene expression patterns. In addition, the two paths of differentiation revealed by our trajectory analysis did not show a tendency to express a specific Th-like signature (Supplementary Fig. 11d). For example, TBX21 and GATA3 were expressed at higher levels in Path I, while IFNG was higher in Path II. Additional studies are needed to explore this important issue. A previous study has suggested that Treg cells from non-lymphoid organs differ from those in lymphoid organs and exhibited tissue-adapted gene signatures13. The present findings identified differences in gene patterns between PB and BM Treg cells. Future studies on other tissues will further resolve the tissue-specific differentiation of Treg cells.

Treg cell heterogeneity and differentiation were also studied in the context of allo-HSCT. FOXP3hi and MKI67hi Treg subsets and the two differentiation pathways were still present in allo-HSCT patients regardless of aGVHD. However, other effector subsets from aGVHD patients displayed a senescence-like phenotype, and a decreased expression of suppression and migration-related molecules. Our results are consistent with previous microarray analysis data suggesting reduced expression of migratory and suppressive genes, including CCR1, CCR3, CCR5, CXCR3, CXCR6, LGALS1, and GZMA, in aGVHD patients43. With the caveat of the examination of a limited number of specimens, the average age of aGVHD patients was higher than that of non-aGVHD patients, although the average age of donors was comparable. A previous study described that the combination of donor and recipient age is a predictor of GVHD44. The senescence-like defect of Treg cells from aGVHD patients might be at least partially attributed to the older age of aGVHD patients compared with non-aGVHD patients.

In conclusion, with an unbiased single-cell approach, our study reveals previously unrecognized effector subsets and two-path differentiation structure in the human Treg compartment. These aspects are conserved between PB and BM and between steady state conditions and immune disturbance. The features related to function, migration, metabolism, activation, proliferation, TCR signaling, and transcription factors in different subsets and pathways are illustrated. We also suggest the transcription factor FOXP3 and SUB1 might be involved in promoting some features of the two-paths, although future study on the complete list of differentially expressed transcription factors will provide more complete understanding of two-path differentiation. These findings enrich the knowledge of human Treg cell heterogeneity, function, and differentiation, and provide a single-cell resolution atlas that will inform the greater understanding of Treg cells and Treg cell-related diseases and therapeutic interventions in these diseases.

Methods

Human specimens

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, Institute of Hematology and Hospital of Blood Disease, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Tianjin, China (approval number: KT2017069-EC-2). All the people in this study provided written informed consent for sample collection and data analyses. The inclusion criteria of patients were allogeneic stem cell transplantation, donor cell chimerism of CD3+ cells > 95%, and no active infections (i.e., cytomegalovirus or hepatitis B virus). Nine HDs, six non-aGVHD patients and six aGVHD patients were enrolled in this study. aGVHD was staged according to modified Glucksberg criteria45. Their ages ranged from 12 to 58, with a median age of 32. All HSCT patients received aGVHD prophylaxis with tacrolimus or ciclosporin plus short-term methylprednisolone, with or without ruxolitinib. PB samples with/without paired BM samples were obtained for the subsequent lymphocyte isolation. Patient characteristics are given in Supplementary Data 1.

Specimen preparation of single-cell suspensions

PB and BM were collected, and coagulation was prevented by the addition of 50 U/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Mononuclear cells from PB or BM were isolated using Lymphoprep (STEMCELL, Vancouver, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lysis of red blood cells was performed with 500 μl of ACK (Lonza, NJ, USA) for 5 min on ice. These cells were resuspended in sorting buffer PBS supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, CA, USA). Suspensions were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer before immunostaining.

Flow cytometry

For the analysis of cell surface molecules, single-cell suspensions were prepared and incubated with the following antibodies: PE-Cyanine7-anti-human CD4 (357410, Biolegend, 1/200), BV785-anti-human CD4 (300553, Biolegend, 1/200), APC-Cyanine7-anti-human CD3 (317341, Biolegend, 1/200), APC-anti-human CD25 (302610, Biolegend, 1/100), BV711-anti-human CD25 (356137, Biolegend, 1/100), FITC-anti-human CD127 (351312, Biolegend, 1/100), BV510-anti-human CD127 (351331, Biolegend, 1/100), BV650-anti-human CCR7 (353234, Biolegend, 1/100), APC-anti-human CCR7 (353213, Biolegend, 1/100), BV605-anti-human HLA-DR (307639, Biolegend, 1/100), APC-anti-human TIGIT (372706, Biolegend, 1/50), APC-Cyanine7-anti-human ITGA4 (304328, Biolegend, 1/50), PerCP-Cyanine5.5-anti-human CCR4 (359405, Biolegend, 1/100), APC-anti-human CCR4 (359407, Biolegend, 1/100), PE-Cyanine7-anti-human CD38 (356608, Biolegend, 1/100), FITC-anti-human CD59 (304706, Biolegend, 1/100), PE-anti-human CD59 (304707, eBioscience, 1/100), PE-anti-human CXCR3 (2009783, Invitrogen, 1/100), FITC-anti-human CXCR3 (353704, Biolegend, 1/50), PE/Cy7-anti-human CD161 (339917, Biolegend, 1/100), PE-anti-human CD152 (369603, Biolegend, 1/100), PE-Cyanine7-anti-human CD152 (369613, Biolegend, 1/100), APC-mouse IgG1 (400119, Biolegend, 1/200), APC-Cyanine7-mouse IgG1 (400127, Biolegend, 1/200), PE-mouse IgG1 (400111, Biolegend, 1/200), PE/Cy7-mouse IgG1 (400125, Biolegend, 1/200), PerCP/Cyanine5.5-mouse IgG1 (400149, Biolegend, 1/200), FITC-mouse IgG1 (400107, Biolegend, 1/200), and BV421-mouse IgG1 (400157, Biolegend, 1/200). Intracellular staining of FOXP3 (PE, 320107, Biolegend, 1/100 or PE, 4331087, eBioscience, 1/50), cytokines and other proteins (FITC-anti-human Helios, 137204, Biolegend, 1/100; APC-anti-human LAP, 349705, Biolegend, 1/100; BV421-anti-human KI67, 562899, BD Bioscience, 1/100) was performed with FOXP3 staining kits (eBioscience, CA, USA). To detect the expression of cytokines IL10 (PerCP/Cyanine5.5, 501417, Biolegend, 1/50), TGF-β1 (BV421, 562962, BD Bioscience, 1/50), GZMA (PE-Cyanine7, 25-9177-41, eBioscience, 1/100), GZMB (FITC, 515403, Biolegend, 1/100), Perforin (BV510, 308119, Biolegend, 1/50), and IL12 p35 (eFluor® 660, 50-7359-41, Invitrogen, 1/50) cells were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml) in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) for 4 h before analysis46. The antibodies were obtained from eBioscience, Biolegend (CA, USA), Invitrogen and BD Biosciences (CA, USA) and were listed in Supplementary Data 10. Flow cytometry data were acquired on LSR II, FACSCanto II or FACSAria III (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, OR, USA).

Single-cell sorting and processing of 10× Genomics single cell RNA-seq and TCR-seq

Based on FACS analysis, single cells of different subtypes, including DAPI−CD3+CD4+CD25+CD127− Treg cells and DAPI−CD3+CD4+CD25− Tcon cells, were sorted into microcentrifuge tubes (Axygen, CA, USA) filled with 200 µl of PBS with 0.06% BSA. Cells were then encapsulated in one lane of a 10× Chromium instrument, and libraries were constructed with a Chromium Single Cell 3ʹ GEM, Library & Gel Bead Kit v3 or Chromium Single Cell 5′ Library & Gel Bead Kit plus Chromium Single Cell V(D)J Enrichment Kit (Human T Cell), following the 10× Genomics protocol (10× Genomics, CA, USA).

Processing and quality control of single-cell RNA-seq data

For 3′ single cell RNA-seq and 5′ single cell RNA-seq data, raw reads obtained from the 10× Genomics single-cell RNA-seq platform were demultiplexed and mapped to the human reference genome GRCh38 using the CellRanger software (version 3.0.2) (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software) with default parameters. Cells were removed if they expressed fewer than 200 unique genes, or greater than 20% mitochondrial genes. Then, genes that were expressed in 5 or more cells were retained for further analysis. FOXP3 is essential for Treg cells to function properly. In this study, FOXP3 positive cells were retained for downstream analysis. Finally, our study included 43,178 FOXP3+ Treg cells and 3,138 CD4+FOXP3− Tcon cells (Supplementary Data 2).

Dimensionality reduction and cell clustering

The R package Seurat (version 3.0.2)22 implemented in R (version 3.6) were used to perform dimensional reduction of Treg and Tcon cell RNA data. The “NormalizeData” function from Seurat was used to normalize the raw counts, and the scale factor was set to 100,000, then followed by “FindVariableFeatures” with default parameters to calculate highly variable genes for each sample. After performing “JackStraw”, which returned the statistical significance of PCA scores, we selected ten significant PCs to conduct dimension reduction and cell clustering. Then, cells were projected in 2D space using t-SNE or UMAP with default parameters. Clustering on individual tissues used the following resolutions: for Treg cells, 0.5 on HD-BM, 0.5 on HD-PB, 0.4 on non-aGVHD-BM, 0.36 on non-aGVHD-PB, 0.36 on aGVHD-BM, 0.5 on aGVHD-PB; for Tcon cells 0.3 on HD-PB.

Integrated analysis of different conditions 10× Genomics-derived data

To account for batch effect among different samples in each condition (HD-BM, HD-PB, Non-aGVHD-BM, Non-aGVHD-PB, aGVHD-BM, aGVHD-PB), we used “FindIntegrationAnchors” in the Seurat package to remove batch effect and merge samples in each condition to one object. In detail, the top 2 000 genes with the highest expression and dispersion from each sample were used to find the integration anchors, and then the computed anchoret was applied to perform dataset integration.

Identification and analysis of differentially expressed genes

To identify unique differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among each cluster, the “FindAllMarkers” function from Seurat was used and non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum tests were set to evaluate the significance of each individual DEG. The DEGs with adjusted P value less than 0.05 were thought to be significant and used in downstream analysis. Then, significant genes were selected as input to perform gene ontology analysis through DAVID (https://david-d.ncifcrf.gov, version 6.8)47.

Clustering, heatmaps and dot plots for gene expression in single cells

Hierarchical clustering and heatmap generation were performed for single cells on the basis of normalized expression values of marker genes curated from the literature or identified significant DEGs. To visualize the expression of individual genes, cells were grouped by their cell type as determined by analysis with Seurat. Normalized gene expression values were plotted for each cell type as a heatmap or dot plot in R.

PAGA analysis

To assess the global connectivity topology between the Treg cell clusters we applied Partition-based graph abstraction (PAGA)48. The weighted edges represent a statistical measure of connectivity between the partitions. Connections with a weight less than 0.3 were removed.

Functional enrichment analysis of signature genes

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) analysis was performed to identify the pathway alterations that underlie our Treg cell subsets with the Bioconductor package GSVA (version 1.16.0). The expression matrix of Treg cells were subjected to the GSVA algorithm to calculate GSVA enrichment scores for each gene set, and the gene sets are listed in Supplementary Data 6.

Pseudotime trajectories analysis

Pseudotime trajectories were constructed with the R package Monocle (version 2.12.0)49, ordering genes were identified by the “differentialGeneTest” function, and adjusted P value less than 0.001 were regarded as significant and used to order cells. The discriminative dimensionality reduction with trees (DDRTree) method was used to reduce data to two dimensions and visualized through the “plot_cell_trajectory” function. To detect genes that play essential roles in cell fate decisions, branched expression analysis modeling (BEAM) from Monocle was implemented to identify genes with branch-dependent expression and visualized with the “plot_genes_branched_heatmap” function.

Preprocessing and analysis of scTCR-seq data

TCR sequence data from Chromium single cell 5′ RNA-seq libraries were processed by CellRanger (version 3.0.2) with default parameters. To compare the TCR data among different samples, multiple libraries were analyzed together according to the documentation provided by 10× Genomics (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-vdj/software/pipelines/latest/advanced/multi-library-samples). First, we constructed a mro file and checked by “cellranger mrc”. Then, “cellranger vdj” was used to align TCR data to human Cell Ranger V(D)J compatible reference (http://cf.10xgenomics.com/supp/cell-vdj/refdata-cellranger-vdj-GRCh38-alts-ensembl-3.1.0). The number of distinct UMIs aligned to each TCR alpha/beta pair less than 10 were filtered out, and only the productive TCR alpha/beta pairs were kept for further analysis. Finally, we identified the TCR alpha/beta pairs for 13,349 cells.

Isolation of Treg clusters or different path cells

Treg cell clusters or paths were purified from human PBMCs with the indicated genotypes. In brief, CD4+ T cells or CD4+CD25+CD127low Treg cells were selected from cell suspensions by EasySep™ Human CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit or EasySep™ Human CD4+CD127lowCD25+ Regulatory T Cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then isolated as by FACSAria III (BD Biosciences). Living Treg cluster cells (DAPI negative, CD4+CD25+CD127−) were isolated with the following marker antibody combinations: HLA-DR−CCR7++TIGIT− for cluster 5 (P5), HLA-DR−CCR7+TIGIT− for cluster 3 (P3), HLA-DR−CCR7+TIGIT+ for cluster 0 (P0), HLA-DR−CCR7−TIGIT+ITGA4− for cluster 1 (P1), HLA-DR−CCR7−TIGIT+ITGA4+ for cluster 6 (P6), HLA-DR−CCR7−TIGIT− for cluster 4 (P4), HLA-DR+CCR7−CD25++CCR4++ for cluster 7 (P7), HLA-DR+CCR7−CD38+CD59+ for cluster 8 (P8), and HLA-DR+CCR7−CD38−CD59−CD25+CCR4+ for cluster 2 (P2). Living Treg different Path cells (DAPI negative, CD4+CD25+CD127−) were isolated with marker antibody combinations as follows: as CCR7+ for Pre-branch, CCR7−CCR4med/hi for Path I, and CCR7−CXCR3+ for Path II.

In vitro Treg suppression assay, cell lineage maintenance and survival

Based on FACS analysis, DAPI−CD4+CD25−CD44−CD62L+ T cells were sorted and used as responder cells (Tresp). For in vitro suppression assay, Tresp cells (4 × 104) were labeled with Tag-it VioletTM proliferation and cell tracking dye kit (Biolegend) and cultured in the presence or absence of FACS-isolated Treg cells from distinct clusters or different path cells with the ratio 1: 2 (Treg: Tresp) for 96 h, with CD3/CD28 T cell activator (3 µl/ml, STEMCELL). The cell division index of Tresp cells was assessed by dilution of Tag-it Violet, using FlowJo software. The calculation formula to determine the suppression ability of Treg in vitro is: Suppression (%) = (Percentage of proliferating Tresp cells alone - Percentage of proliferating Tresp cells treated with Treg)/ Percentage of proliferating Tresp cells alone × 10050,51. The in vitro FOXP3 stability, proliferation capacity and apoptosis of Treg cells were assessed after 96 h in vitro culture (3 µl/ml CD3/CD28 T cell activator, 20 ng/ml IL-2) by the expression of FOXP3, the dilution of Tag-it Violet and the expression of Annexin V, respectively.

Plasmid preparation and lentivirus packaging

To overexpress the indicated TFs, the canonical CDS at each gene locus was obtained from NCBI GenBank. After necessary sequence optimization for gene cloning, DNA sequences were synthesized and sub-cloned into the lentivirus vector pLVX-IRES-mCherry (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The TF overexpression vectors were co-transfected into 293 T (CRL-11268, American Type Culture Collection) cells with the 2nd-generation lentivirus packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2G, and the virus in the medium supernatant was harvested and concentrated for target cell infection.

In vitro cell culture and gene transduction of Treg and Tcon cells

Human PBMC-derived Treg cells were isolated via the MACS strategy (STEMCELL) based on their surface markers: CD4+CD25+CD127−, and FACS was followed to isolate Treg cells in high purity, with sorting markers: DAPI−CD4+CD25+CD127−. In some cases, DAPI−CD4+CD25− Tcon cells were also isolated via FACS. Tcon and Treg cells were maintained in the human T cell growth medium (STEMCELL) and supplemented with IL-2 at concentrations of 100 ng/ml and 500 ng/ml, respectively, and anti-human CD3/CD28 T cell activator (25 µl/ml) were added to the medium to initiate Tcon or Treg cell proliferation. After 48 h of in vitro activation, lentivirus with a typical titer of 5 × 107 TU/ml was added to the cell culture medium to reach the final MOI of 15, and a cell spin-infection protocol was applied for gene transduction. Polybrene was also added to the medium to enhance the gene transduction efficiency. Eight to ten hours post infection, the cell supernatant was replaced with fresh T cell growth medium to facilitate the removal of virus and transduction reagent from cells. Seventy-two hours later, transduction efficiency was determined by measuring the percentage of mCherry+ cells with FACS. 5-6 days after transduction, lentivirus transduced cells were purified by FACS sorting of mCherry+ cells. The following RT-PCR, flow cytometry staining and Western blot were carried out in the sorted cells. With the limited cell numbers, we transducing the cells with vector and FOXP3-OE virus or with vector and SUB1-OE virus in the detection of protein levels of genes.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Lentivirus transduced Treg or Tcon cells were sorted by FACS and Total RNA was extracted from these sorted cells using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). For semiquantitative PCR, the SYBR green-based CTΔΔT method was carried out, and all reactions were run on an ABI 7900 instrument. The Primers included in the experiments are listed in Supplementary Data 10, and the 18 S rRNA expression level was selected for the internal reference for target expression level analysis.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Lentivirus transduced Treg cells were sorted by FACS and then cells were stimulated with CD3/CD28 T cell activator (25 µl/ml) for 48 h to amplify FGL2 production. Post stimulation, the conditional medium was collected and cell debris was removed by centrifugation. The soluble form of FGL2 secreted by Treg cells was quantified by LEGEND MAX™ Human FGL2 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kit (Biolegend). The manufacturer’s instructions were followed to measure the secretory FGL2 levels in conditional medium, and the concentrations of FGL2 were converted from 450nm-570nm absorbance, which the microplate reader detected. The standard curve was plotted at the same time to facilitate the calculation of FGL2 concentrations.

Western blot

Lentivirus transduced Treg cells were sorted by FACS, and then cells were lysed for SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the denatured protein samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane for incubation with primary antibody. Antibodies to SUB1 (HPA001311, Sigma-Aldrich) and GAPDH (D16H11, Cell Signaling Technology) were both applied with a dilution rate of 1: 3000. Post incubation with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, membranes were washed by TBST, then followed by the other incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for an hour at room temperature52. The specific signals from HRP-ECL reaction were visualized by the ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

Experimental results are reported as mean values ± SEM; n represents numbers of patients or healthy donors in the experiments, as specified in the Figure Legends. An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (for two group comparisons) or a one-way ANOVA was performed using Prism (GraphPad, CA, USA) and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed using R package ggpubr. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No specific randomization or blinding protocols were used. The ANOVA results of certain experiments were given in Supplementary Data 11. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank professor Tao Cheng and professor Hongbo Luo, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, for support of the project; Xin Gao, Xuelian Cheng, Min Liu, Chuo Li, Mingyang Wang, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, for their excellent assistance with the experimental support and data analyses. This work was supported by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2017-I2M-1-015, 2016-I2M-1-003, 2016-I2M-3-002, 2016-I2M-1-018), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81401295, 81870090, 82000191, 81870089, 81890990), the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFA0102300, 2017YFA0103102, 2019YFA0110200), the Tianjin Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars (17JCJQJC45800), the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin City (18JCQNJC12100), the State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology Research Grant (Z20-07), and the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2018PT32034, 2019-RC-HL-013).

Source data

Author contributions

Y.L., X.F. conceived the project. Y.L., B.W., Q.N., X.S., G.S., H.C., X.C., H.H., H.W. and X.F. designed the experiments. Y.L., B.W., Q.N., X.S., S.Z., C.Z., X.S., Y.S., J.W. and M.L. performed the experiments; C.X., Y.L. and Y.B. analyzed the single-cell sequencing data. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results. Y.L., C.X., B.W., Q.N., X.S. and X.F. wrote the manuscript. M.H., E.J., L.S. and X.F. supervised the project.

Data availability

The scRNA-seq data and scTCR-seq data sets have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at “GSE175604”. Data usage shall be in full compliance with the Regulations on Management of Human Genetic Resources in China. All other relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source data underlying Figs. 1h, 2c-e, 3a, 3f, 4a-e, 5d-j, 6a, 7a and Supplementary Figs. 1c-f, 2e, 3a, 3c, 4a-f, 5b, 6a, 6e, 6f, 7b, 7e–h, 8a, 8c, 8e, 8f are provided as a Source Data file with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper. A reporting summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Lawrence Kane and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yuechen Luo, Changlu Xu, Bing Wang, Qing Niu and Xiuhua Su.

Contributor Information

Mingzhe Han, Email: mzhan@ihcams.ac.cn.

Erlie Jiang, Email: jiangerlie@ihcams.ac.cn.

Lihong Shi, Email: shilihongxys@ihcams.ac.cn.

Xiaoming Feng, Email: fengxiaoming@ihcams.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-24213-6.

References

- 1.Lu L, Barbi J, Pan F. The regulation of immune tolerance by FOXP3. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:703–717. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Molecular control of regulatory T cell development and function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017;49:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:1–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plitas G, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: differentiation and function. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016;4:721–725. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyara M, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason GM, et al. Phenotypic complexity of the human regulatory T cell compartment revealed by mass cytometry. J. Immunol. 2015;195:2030–2037. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollbacher B, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of human effector and regulatory T cell subsets identifies predictive population signatures. Immunohorizons. 2020;4:585–596. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.2000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng C, et al. Landscape of infiltrating T cells in liver cancer revealed by single-cell sequencing. Cell. 2017;169:1342–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azizi E, et al. Single-cell map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1293–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sade-Feldman M, et al. Defining T cell states associated with response to checkpoint immunotherapy in melanoma. Cell. 2018;175:998–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zemmour D, et al. Single-cell gene expression reveals a landscape of regulatory T cell phenotypes shaped by the TCR. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:291–301. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0051-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miragaia RJ, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of regulatory T cells reveals trajectories of tissue adaptation. Immunity. 2019;50:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Acute graft-versus-host disease - biologic process, prevention, and therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:2167–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1609337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su X, et al. Loss of Lkb1 impairs Treg function and stability to aggravate graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2019;17:483–495. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0312-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xhaard A, et al. Reconstitution of regulatory T-cell subsets after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2014;49:1089–1092. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edinger M, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat. Med. 2003;9:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martelli MF, et al. HLA-haploidentical transplantation with regulatory and conventional T-cell adoptive immunotherapy prevents acute leukemia relapse. Blood. 2014;124:638–644. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-564401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunstein CG, et al. Umbilical cord blood-derived T regulatory cells to prevent GVHD: kinetics, toxicity profile, and clinical effect. Blood. 2016;127:1044–1051. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-653667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuadrado E, et al. Proteomic analyses of human regulatory T cells reveal adaptations in signaling pathways that protect cellular identity. Immunity. 2018;48:1046–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenblum MD, Way SS, Abbas AK. Regulatory T cell memory. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:90–101. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smigiel KS, et al. CCR7 provides localized access to IL-2 and defines homeostatically distinct regulatory T cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:121–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong S, et al. Multiparameter single-cell profiling of human CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T-cell populations in homeostatic conditions and during graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2013;122:1802–1812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-482539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinforma. 2013;14:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponzetta A, et al. Neutrophils driving unconventional T cells mediate resistance against murine sarcomas and selected human tumors. Cell. 2019;178:346–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li MO, Rudensky AY. T cell receptor signalling in the control of regulatory T cell differentiation and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:220–233. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein L, Robey EA, Hsieh CS. Central CD4(+) T cell tolerance: deletion versus regulatory T cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19:7–18. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thornton AM, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trapnell C, et al. The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:381–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lienart S, et al. Structural basis of latent TGF-beta1 presentation and activation by GARP on human regulatory T cells. Science. 2018;362:952–956. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aarts-Riemens T, Emmelot ME, Verdonck LF, Mutis T. Forced overexpression of either of the two common human Foxp3 isoforms can induce regulatory T cells from CD4(+) CD25(-) cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38:1381–1390. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkey E, Maillard I. New insights into graft-versus-host disease and graft rejection. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2018;13:219–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbi J, Pardoll D, Pan F. Treg functional stability and its responsiveness to the microenvironment. Immunol. Rev. 2014;259:115–139. doi: 10.1111/imr.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mancusi A, Piccinelli S, Velardi A, Pierini A. CD4(+) FOXP3(+) regulatory T cell therapies in HLA haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2901. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pangrazzi L, Weinberger B. T cells, aging and senescence. Exp. Gerontol. 2020;134:110887. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.110887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira BI, et al. Sestrins induce natural killer function in senescent-like CD8(+) T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2020;21:684–694. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0643-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu W, Larbi A. Markers of T cell senescence in humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1742. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baecher-Allan C, Wolf E, Hafler DA. MHC class II expression identifies functionally distinct human regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4622–4631. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gang Y, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq unveils critical regulators of human FOXP3+ regulatory T cell stability. Sci. Bull. (Beijing) 2020;65:1114–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ukena SN, et al. Human regulatory T cells in allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:e82–e92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bacigalupo A, et al. Graft versus host disease in unmanipulated haploidentical marrow transplantation with a modified post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PT-CY) regimen: an update on 425 patients. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2019;54:708–712. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Przepiorka D, et al. 1994 consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transpl. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu D, et al. Lkb1 maintains Treg cell lineage identity. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15876. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf FA, et al. PAGA: graph abstraction reconciles clustering with trajectory inference through a topology preserving map of single cells. Genome Biol. 2019;20:59. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1663-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiu X, et al. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat. methods. 2017;14:979–982. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ward ST, Li KK, Curbishley SM. A method for conducting suppression assays using small numbers of tissue-isolated regulatory T cells. MethodsX. 2014;1:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McMurchy AN, Levings MK. Suppression assays with human T regulatory cells: a technical guide. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012;42:27–34. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen S, et al. Control of Treg cell homeostasis and immune equilibrium by Lkb1 in dendritic cells. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:5298. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07545-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The scRNA-seq data and scTCR-seq data sets have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at “GSE175604”. Data usage shall be in full compliance with the Regulations on Management of Human Genetic Resources in China. All other relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source data underlying Figs. 1h, 2c-e, 3a, 3f, 4a-e, 5d-j, 6a, 7a and Supplementary Figs. 1c-f, 2e, 3a, 3c, 4a-f, 5b, 6a, 6e, 6f, 7b, 7e–h, 8a, 8c, 8e, 8f are provided as a Source Data file with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper. A reporting summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.