Abstract

Cancer is a multi-faceted disease in which spontaneous mutation(s) in a cell leads to the growth and development of a malignant new organ that if left undisturbed will grow in size and lead to eventual death of the organism. During this process, multiple cell types are continuously releasing signaling molecules into the microenvironment, which results in a tangled web of communication that both attracts new cell types into and reshapes the tumor microenvironment as a whole. One prominent class of molecules, chemokines, bind to specific receptors and trigger directional, chemotactic movement in the receiving cell. Chemokines and their receptors have been demonstrated to be expressed by almost all cell types in the tumor microenvironment, including epithelial, immune, mesenchymal, endothelial, and other stromal cells. This results in chemokines playing multifaceted roles in facilitating context-dependent intercellular communications. Recent research has started to shed light on these ligands and receptors in a cancer-specific context, including cell-type specificity and drug targetability. In this review, we summarize the latest research with regards to chemokines in facilitating communication between different cell types in the tumor microenvironment.

Keywords: Chemokines, Cancer, Tumor microenvironment, Review

Introduction

Cancer is a multi-faceted disease in which spontaneous mutation(s) in a cell leads to the growth and development of a malignant new organ that if left undisturbed will grow in size and lead to eventual death of the organism. In the year 2020, over 600,000 people in the United States are projected to die from cancer (SEER common cancer sites 2020), making it second to only heart disease with respect to mortality number (CDC 2020). Although a tumor consists of dozens of different cell types functioning together, for the longest time the individual cancer cells within the tumor were considered the driving force and studied more in depth than other cell types. This has led to both significant progress and an uneven knowledge base in understanding cancer cells individually without understanding the tumor microenvironment (TME).

There has been a recent movement to not view cancer through the lens of cancer cells, but to look at the tumor as a whole microenvironment with dozens of cell types consistently communicating with and reacting to each other. This view is more in line with the tumor as an evolving landscape that is constantly adapting to changes in the microenvironment. Indeed, many studies recently have found that cross talk between cancer and non-cancer cells, referred to as stromal cells, play roles in all aspects of cancer progression, from invasion (Wang et al. 2018a; Lee et al. 2018; Higashino et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2020) to metastasis (Yu et al. 2017b; Irshad et al. 2017; Liubomirski et al. 2019a; Kalpana et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2020) to immune cell recruitment (Yuan et al. 2016; Araujo et al. 2018; Walens et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2020a) and drug resistance(Ham et al. 2018; Fang et al. 2018; Pasquier et al. 2018; Le Naour et al. 2018; Li et al. 2020). Cross talk between cancer cells and the stroma can be mediated through direct physical contact (Ding et al. 2016; Liubomirski et al. 2019b), or by indirect cellular signaling (Farmaki et al. 2016; Feng et al. 2018b; Tivari et al. 2018; Pausch et al. 2020), further adding to the complexity of the system.

Indirect cell–cell signaling is mediated through signaling molecules known as cytokines, which are released from one cell type and bind to a specific receptor in another to initiate physical and transcriptional changes in the cell. Chemokines are a chemotactic subtype of cytokines that initiate physical movement in cells when the signaling cascade starts (Borish and Steinke 2003; Dinarello 2007). The first chemokine to be discovered, CXCL4, was discovered over 50 years ago in the context of anti-heparin activity in the blood (Deutsch et al. 1955). As of now, close to 50 chemokine ligands and 20 chemokine receptors are collectively known about, with several of them classified as orphan receptors without a known specific ligand (Raman et al. 2007; Shore and Reggio 2015; Lorenzen et al. 2019).

Research into chemokines poses a difficult but rewarding challenge in the context of cancer. Chemokines themselves are quite promiscuous—many receptors will accept multiple ligands, and vice-versa (Chow and Luster 2014; Lacalle et al. 2017; Marcuzzi et al. 2018). Additionally, there is significant crosstalk between the downstream signaling pathways after the chemokine cascade initiates, with multiple chemokines converging on the PI3K, AKT, SMAD, STAT3, and ERK1/2 pathways, in addition to many others known and unknown (Tang et al. 2016; Loveridge et al. 2017; Gallo et al. 2018; Ding et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2019a; Li et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2020). To add to the complexity, some chemokines have been shown to play multiple roles in intercellular signaling cascades, based on the tissue and cell type context they are expressed in. Untangling the cross-talk between chemokines while also focusing on and decoding the tissue-type specific context will require patience along with many independent experiments. Many labs have realized the importance of this task, and there has been an influx of papers demonstrating that targeting specific chemokines in both cancer cells and stroma can disrupt cancer progression (Yuan et al. 2016; Tanabe et al. 2016; Su et al. 2017; Nishikawa et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019b).

There have been many high-quality reviews recently that describe the different chemokines, receptors, and the signaling pathways involved in great detail (Stone et al. 2017; Cecchinato and Uguccioni 2018; Susek et al. 2018; Marcuzzi et al. 2018; Mollica Poeta et al. 2019) and are highly valuable reads. To differentiate and not be repetitive, this review will focus on chemokine signaling in the context of cancer-stroma communication, and will focus on new discoveries as of 2016.

With respect to cancer progression, this review will focus on chemokine signaling in three different contexts: chemokines in cancer-immune cell communication, chemokines in cancer-endothelial cell communication, and chemokines in cancer-fibroblast communication. These three categories describe the unique roles that chemokines play in the different contexts of cancer progression. This review will cover many cancer types, and be organized by each chemokine/receptor pair.

Immune

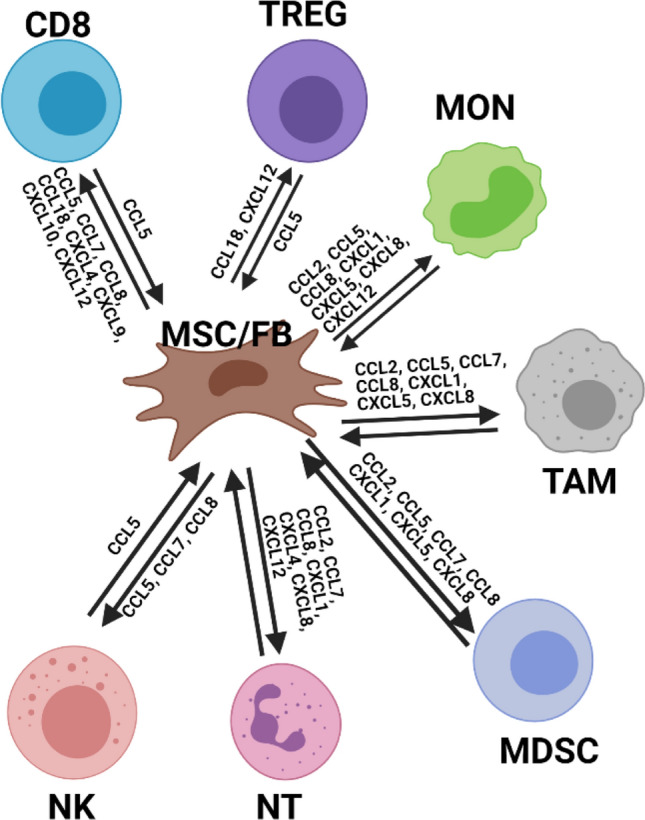

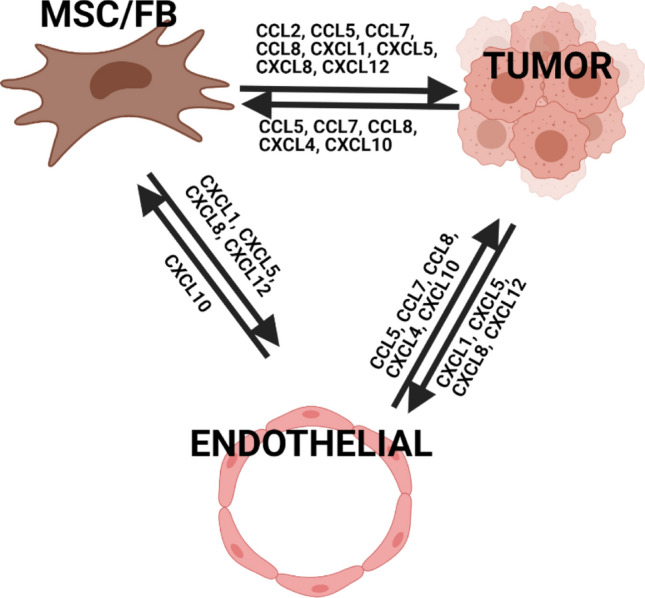

Immune signaling was among the first contexts in which chemokines and their receptors were extensively studied (Lohmann-Matthes 1989; Stoeckle and Barker 1990; Mantovani et al. 1993). Chemokine receptors are expressed in a variety of immune cell types and subtypes, largely in the context of mediating an anti-inflammatory response. It is this anti-inflammatory response that initially guides the chemotactic migration of immune cells to the site of the tumor and is the basis of incorporating immune cells into the TME as a whole. There have been several reviews lately that have covered this subject in a varying amount of depth (Lacalle et al. 2017; Mollica Poeta et al. 2019; Do et al. 2020; Sjöberg et al. 2020). In this review, the important basics will be covered, with an emphasis on integrating new information from recent publications. An overarching view of immune signaling in the TME is shown in Figs. 1 and 2, which each summarize the chemokines that immune cells use to communicate between cancer cells and fibroblasts, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Small representation of the TME with a focus on communication between cancer and immune cells. Cancer cells express high levels of many different chemokines and receptors, whereas immune cells express more specific chemokines and receptors, depending on the cell subtype. Frequently it is chemokines secreted my cancer cells that initially attract immune cells into the TME. It should be noted that this is not a comprehensive cartoon, since the expression of certain chemokines and ligands can be context and environment dependent. CD8: CD8 + T-cell; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; NK: Natural Killer Cell; NT: Neutrophil; Treg: Regulatory T-cell; MON: Monocyte; MDSC: Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cell

Fig. 2.

Small representation of the TME with a focus on communication between fibroblast/mesenchymal stromal cells and immune cells. Fibroblasts express high levels of many different chemokines, but express very few receptors. Frequently it is chemokines secreted by cancer cells and fibroblasts that initially attract immune cells into the TME. It should be noted that this is not a comprehensive cartoon, since the expression of certain chemokines and ligands can be context and environment dependent. MSC/FB: Mesenchymal Stromal Cell / Fibroblast; CD8: CD8 + T-cell; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; NK: Natural Killer Cell; NT: Neutrophil; Treg: Regulatory T-cell; MON: Monocyte; MDSC: Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cell

Vascular

Tumor growth, progression, and metastasis all rely on the creation and manipulation of a TME that is hospitable for the cancer cells. An important part of such an environment is the formation of new blood vessels that are able to shuttle nutrients and oxygen from outside the TME and deliver them to the cancer cells. These nutrients are so essential for cancer cell and tumor growth that angiogenesis has been considered a rate-limiting step in tumor formation and progression (Bergers and Benjamin 2003). Chemokines and their receptors have been known to be important regulators of and participants in angiogenesis for years (Dimberg 2010). The C-X-C-motif (CXC) family of chemokines can be grouped as either angiogenic or angiostatic, based on the presence of a glutamic-leucine-arginine (ELR) motif at the N terminal (Mollica Poeta et al. 2019). ELR + chemokines include CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL7, and CXCL8, while ELR- chemokines are CXCL4, CXCL4L1, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, and CXCL14. Interestingly, CXCL12 does not contain an ELR motif but is one of the best known and studied pro-angiogenic chemokines (Chow and Luster 2014).

In addition to angiogenesis, endothelial cells play another important role in tumor progression. In order to facilitate escape and metastasis, cancer cells need to migrate through endothelial cell barriers in order to move into the blood for transport. This process, called intravasation, is required for a tumor to metastasize to other sites. Chemokines have also been shown to play a role in this process, possibly by allowing direct access, or by weakening the barriers and enabling cancer cells to slip through the blood vessel (Reymond et al. 2013; Ahirwar et al. 2018; Ren et al. 2019). This review will cover vascular-chemokine signaling in the context of both angiogenesis and intravasation, with a focus on new information from recent publications. Figure 3 summarizes the chemokines that facilitate communication between endothelial cells and the rest of the TME.

Fig. 3.

Small representation of the TME with a focus on communication between fibroblast/mesenchymal stromal cells, cancer cells, and endothelial cells. Endothelial cells express few and very specific chemokines and receptors, relative to fibroblasts and cancer cells. It should be noted that this is not a comprehensive cartoon, since the expression of certain chemokines and ligands can be context and environment dependent. MSC/FB: Mesenchymal Stromal Cell / Fibroblast

Mesenchymal stromal

Similar to other stromal cell types, chemokines play an important role in facilitating communication between cancer cells and cells of mesenchymal origin, such as fibroblasts or mesenchymal stem cells. Quite interestingly, mesenchymal cells are a major contributor of many different secreted chemokines, but express only a few receptors at relatively lower levels (Raman et al. 2007). Fibroblasts are the main mesenchymal cell type present in the TME and show heterogeneity and subpopulations with heterogeneity similar to cancer cells (Truffi et al. 2020). While the origin of fibroblast heterogeneity is unclear, there is evidence that the heterogeneity is partly due to the recruitment and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) recruited from different tissues (Guo et al. 2008). Recent studies have shown these fibroblasts and MSCs secrete chemokines that polarize macrophages (Kersten et al. 2017), deposit linear collagen (Brett et al. 2020), induce cancer cell invasion (Liu et al. 2017; Li et al. 2019b), and contribute to the development of drug resistance (Le Naour et al. 2018)—all facilitated through chemokine signaling. This review will focus on recent studies, with an emphasis on covering and integrating the chemokine cross-talk between multiple cell types in the TME. These concepts are summarized in Figs. 2 and 3.

Chemokines

CCL1/CCR8

CCL1 is one of the few non-promiscuous chemokines, known to bind only to the CCR8 receptor. Relative to the other chemokines, the specific effects of CCL1 have not been well studied yet. Fortunately, recent papers are slowly elucidating its specific roles in immune cell recruitment in the TME. In breast cancer, CCL1 has been shown to be secreted by both cancer cells (Xu et al. 2017) and macrophages (Ding et al. 2017). In matrigel migration assays, CCL1 secreted by the triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line 4T1 was shown to attract regulatory T cells (Tregs) to the proximity (Xu et al. 2017). In a separate study, immuno-histochemistry (IHC) for CCL1 from 192 patients with invasive breast cancer (BC) found significant correlation between high intratumoral CCL1 expression and FOXP3+ Treg infiltration of the tumor (Kuehnemuth et al. 2018). Conversely, using a murine model of BC with forced overexpression of the SAP gene, the authors found an overall reduction in tumor growth, CCL1 expression, and the number of infiltrating macrophages (Ding et al. 2017). Further treatment of macrophages in culture with SAP led to a reduction in CCL1 levels, implying that the CCL1 was secreted by macrophages in the tumor. None of these papers studied the responsible mechanism(s) closely, but taken together they indicate an important immune-mediated role of CCL1, especially in Treg recruitment.

CCL2/CCR2

CCL2 is another non-promiscuous chemokine that specifically binds to CCR2, although CCR2 also accepts several other chemokines as additional ligands. CCL2 is expressed by a variety of cell types, including endothelial, epithelial, myeloid, fibroblasts, and myoepithelial (Deshmane et al. 2009). Originally named Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP1), recent studies have shown much more diverse functions than simply attracting monocytes.

Studying the expression of CCL2 in multiple murine models of cancer has demonstrated that CCL2 attracts stroma-remodeling macrophages that lead to a pro-inflammatory TME, through multiple unique mechanisms (Yang et al. 2016; Sun et al. 2017; Kersten et al. 2017; Nakatsumi et al. 2017; Obr et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2020). CCL2 has also been found to be expressed higher in recurrent BC lesions, relative to the primary tumor site (Heiskala et al. 2019). In one murine model of BC, tumor-secreted CCL2 from the primary site induced the expression of the cytokine IL1ß in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) which led to the systemic induction of IL17 by gamma-delta T cells, polarization of neutrophils, and suppression of CD8 + activity which ultimately led to an immunosuppressive state in other organs (Kersten et al. 2017). In a murine HeLa xenograft model, inhibition of the mTORC-FOXK1 axis increased both the number TAMs and overall tumor progression in a CCL2-dependent manner (Nakatsumi et al. 2017). In a similar study by a different lab, it was found that CCL2 neutralizing treatment of MCF10Ad murine tumors did not affect either tumor growth or CCL2 levels in mice, despite working in a human cell co-culture (Yao et al. 2017), indicating that more work will be needed to understand the tissue-specific function of CCL2 and assess its viability as a potential drug target.

Oftentimes, cell co-cultures using two different cell types have been used to more clearly and simply elucidate specific signaling mechanisms. While these systems are more simple and less representative of human biology as a whole, they enable the disentanglement and elucidation of context-dependent signaling effects, and serve as a solid foundation for more complicated experiments. In a co-culture model of the lung cancer cell line A549 and RAW 264.7 macrophages, treatment with PDGF-BB increased CCL2 expression and macrophage attraction towards cancer cells, mediated through the MAPK/AKT pathways (Ding et al. 2019). Similarly, a co-culture of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells with THP-1 monocytes showed that conditioned media (CM) from PDAC cells induces monocyte migration, monocyte polarization, and monocyte secretion of CCL2 (Chen et al. 2018). In another co-culture of macrophages and BC pre-malignant epithelial MCF10A cells, CCL2 secretion from TAMs induced the expression of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related genes ERO1A and MMP9, leading to increased invasiveness in MCF10A cells (Lee et al. 2018). EMT-related genes were also upregulated in different BC cell lines when treated with CCL2, and found to be modulated by the genes ALDH1A1 and HTRA2 (Hu et al. 2019). The exposure of BC cells to CM from CCL2-secreting TAMs activates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways and increases tamoxifen resistance (Li et al. 2020), indicating a multifaceted role for CCL2 in cancer communication.

The previous studies observe CCL2 in the context of the cancer-immune signaling axis, but this is not the whole story. Much work has recently been done to understand the role of CCL2, secreted from fibroblasts and other mesenchymal stromal cells, in the TME. In a MCF10CA1d xenograft model of BC, co-transplantation of cancer cells with CCL2-expressing fibroblasts increased tumor growth, dependent on the tyrosine kinases SRC and PKC negatively regulating p27KIP expression (Yao et al. 2019). FAK protein depletion in a subset of cancer-associated fibroblast (CAFs) leads to reduced TAM numbers in late-stage tumors through secretion of CCL2 by CAFs (Demircioglu et al. 2020). CAFs isolated from a murine liver cancer tumor were found to be activated by the FAP protein, which lead to upregulated inflammatory profiles of the cytokines STAT3 and CCL2. Further research identified FAP + CAFs as the primary contributors of CCL2, and the STAT3-CCL2 signaling axis enhanced recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (Yang et al. 2016). In other experiments, the co-culture of MSCs with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCCs) increased FAP expression in MSCs, which promoted CCL2-dependant migration of both ESCCs and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) macrophages (Higashino et al. 2019).

While most of the research focuses on CXC chemokines, C–C-motif (CC) chemokines have been shown to play a role in angiogenesis, often mediated through communication with multiple different cell types. In a liver fibrosis murine model of cancer, a population CCR2 + TAMs was identified and showed an active angiogenic and inflammatory transcriptional profile. Treatment of the mice with a CCL2 antagonist reduced the numbers of that specific population, along with tumor growth and vascularization (Bartneck et al. 2019). In a different Her2-driven murine model of BC, the knock-out (KO) of CCL2 prolonged mouse survival by decreasing the development and mobilization of endothelial cell precursors, which ultimately lead to reduced tumor vascularization (Chen et al. 2016). Both these studies demonstrate that CCL2 contributes to angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment, likely through activating and modulating certain populations of TAMs.

Other studies have used co-cultures and drug treatments to identify the stimuli for and effects of CCL2 secretion. Treatment of normal lung fibroblasts with the hormone leptin increases αSMA, CCL2, CXCL8, and CXCL6 expression at both the protein and mRNA levels (Watanabe et al. 2019). The co-culture of PDAC cells with fibroblasts leads to the induction of CCL2 and CXCL8 in the fibroblasts, which results in increased angiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with the corresponding CM (Pausch et al. 2020). Another study demonstrated that treatment of androgen receptor (AR) + CAFs isolated from prostate cancer with testosterone lead to a decrease in CCL2 expression. AR chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) demonstrated that AR likely binds to the CCL2 promoter and modulates its expression. To further confirm the link, the authors treated several prostate cancer cell lines with CCL2, and observed an increase of migration and invasion in those treated cells, leading to a direct link between testosterone, chemokine signaling, and cancer invasiveness in prostate cancer (Cioni et al. 2018).

Overall, these recent papers demonstrate that CCL2 facilitates communication between cancer, immune, mesenchymal, and endothelial cells. This holds true across different cancer types and models, where different pathways are active at different levels and in different cell types. Despite the large volume of studies that exist on CCL2, there is still much progress to be made in the context of CCL2 as a therapeutic target.

CCL3/CCR1|CCR4|CCR5

CCL3, originally named macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP1α), is a promiscuous CC chemokine that recruits leukocytes through binding of the CCR1, CCR4, and CCR5 receptors (Wolpe et al. 1988). CCL3 is well known for the recruitment of immune cells, and recent studies have additionally identified a role in mesenchymal cell signaling.

Inhibiting CCR5 in a murine model of colo-rectal carcinoma (CRC) reduced activated αSMA + intratumoral fibroblasts numbers by preventing the binding of CCL3 secreted from TAMs (Tanabe et al. 2016). In a different model, MSCs in culture were found to naturally secrete CCL3. Further experiments showed several CRC cell lines naturally express the corresponding receptor CCR5, and inhibition of CCR5 in the CRC cells reversed the observed MSC-induced growth in a murine CRC model (Nishikawa et al. 2019), agreeing with the previous study that CCL3 can activate stromal mesenchymal cells in the TME. Though much of the previous and early research has focused on the immune-mediated effects of CCL3, these preliminary studies suggest that its fibroblast|MSC signaling axis is rich in new information, and ready to be explored.

CCL5/CCR1|CCR3|CCR5

CCL5, originally named RANTES, is a promiscuous chemokine that binds to three receptors, CCR1, CCR3, and CCR5. CCL5 is notoriously known for its role in facilitating HIV viral entry into cells, and has been extensively studied in that context (Watson et al. 2005). With respect to cancer, it is known for its role in the recruitment of multiple immune cell types including T cells, macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells (Maghazachi et al. 1996; Wang et al. 2017a). Recent studies have probed deeper into its effects and mechanisms of action.

Gallo et al. used both estrogen receptor (ER) + and TNBC cell lines overexpressing the cytokines CCL5 and IL6 to demonstrate that co-expression in both cell types increases migration and wound healing through the AKT, ERK1/2, and STAT3 pathways in both cell types. In a different study, the injection of nude mice with cancer cells overexpressing CCL5 had no effect on tumor growth, indicating that the effect of CCL5 may be mediated by the immune system, which nude mice are lacking (Gallo et al. 2018). Other research has shown that when CCL5 expression is forced in ovarian cancer cells, T cells will preferentially migrate towards them, even passing through any stromal barriers (Salmon et al. 2012; Peranzoni and Donnadieu 2019). This could help explain why the previous authors saw no effect of CCL5 in tumors from immunodeficient mice.

More studies have confirmed that CCL5 attracts different immune cell types in various types of cancer. Using a PTEN/ERK5 null murine model of prostate cancer, Loveridge et al. showed that loss of Erk5 in combination with the loss of Pten leads to increased CCL5 and CXCL10 expression within the malignant tumor epithelium. This in turn is associated with an increased recruitment of T cells towards the tumor epithelium and distinct sites within the stroma (Loveridge et al. 2017). In another case, the treatment of a murine PDAC model with a CD40 antagonist increased the intratumoral myeloid cell production of CCL5, which selectively recruited CD4 + but not CD8 + T cells into the tumor (Huffman et al. 2020). Using IHC from 72 TNBC patients, Araujo et al. showed that tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were correlated with CCL5 expression. CIBERSORT from public data suggests that CCL5 is correlated with CD8 + , CD4 + T cells, and natural killer (NK) immune cells (Araujo et al. 2018), further demonstrating the importance of CCL5 in immune cell recruitment.

In other contexts, CCL5 has been shown to play a role in tumor metastasis and recursion. Using a RhoA kinase knock-down (KD) murine model of TNBC, Kalpana et al. observed an increase in lung metastasis occurrence that did not affect primary tumor growth, relative to control mice. Further exploration revealed an increase in CCL5 and CXCL12 expression in CAFs located in the primary tumor, which generated a pro-metatastatic niche in other organs (Kalpana et al. 2019). Similarly, the downregulation of Her2 in a murine model of BC led to an increase in CCL5 expression and promoted tumor recurrence by recruiting CCR5 + macrophages that contributed to collagen deposition in residual tumors (Walens et al. 2019). Autocrine CCL5 signaling can activate NFKß and STAT3 in ovarian cancer stem cells and cause them to differentiate into endothelial cells, indicating a pathway through which chemokines can directly induce cancer cells to contribute to the tumor vasculature (Tang et al. 2016). Injection of CCR5-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells into a murine BC model reduced the tumor onset through decreasing CCL5 levels that resulted in an overall reduction in glucose metabolism in the tumor, which demonstrates a possible link between chemokines and cancer metabolism (Gao et al. 2017). CCL5 is well documented in its contributions to cancer progression via the multiple axes, but especially the immune, and could be a promising drug target to pursue (Peranzoni and Donnadieu 2019).

Many co-culture systems have been used to elucidate the effects of CCL5 on tumor related cells. The co-culture of TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells with adipose-derived stem cells and dermal fibroblasts showed an increase in the deposition of of linear and pro-oncogenic collagen IV, found to be produced by fibroblasts in response to CCL5 secreted from both the BC and stem cells (Brett et al. 2020). The co-culture of oral cavity cancer (OCC) cells with MSCs separated via transwells induced CCL5 secretion in and by MSCs which then increased IL6 secretion and chemoresistance in OCC cells through an unresolved mechanism (Pasquier et al. 2018). The treatment of MSCs with TNFα was found to induce CCL5 secretion, which promoted lung metastasis in a murine model of BC by recruiting CXCR2 + neutrophils into the tumor and creating a pro-metastatic environmen t(Yu et al. 2017a). A similar paper demonstrated that TNFα treatment of the same MSCs increases CCL5 secretion, which binds to CCR1 on CRC cells and upregulates the ßCAT/SLUG pathways, inducing EMT in the CRC cells(Chen et al. 2017). These studies taken together demonstrate that cancer cells induce CCL5 secretion by stromal cells, which then creates a hospitable TME for the cancer cells. A separate study demonstrated that immortalized CAFs expressing ESR1 suppressed prostate cancer (PCa) invasion by influencing TAM infiltration. ESR1 bound to the CCL5 promoter and inhibited CCL5 secretion in CAFs which reduced overall TAM infiltration in this model (Yeh et al. 2016). Additionally, CAFs from gastric cancer patients were shown to express higher KLF5 than their normal counterparts. These KLF5 + CAFs secreted CCL5, which induced CCR5 expression in the gastric cancer cells (Yang et al. 2017). These studies demonstrate that CCL5 facilitates communication with mesenchymal stromal cells in addition to immune, and further suggests that disentangling these communication networks will assist in developing therapeutics that target CCL5.

CCL7/CCR1|CCR2|CCR3

CCL7, originally called monocyte-chemotactic protein 3 (MCP3), is a promiscuous CC chemokine closely related to CCL2, with an established role in attracting monocytes and macrophages by binding to the to the CCR1, CCR2, and CCR3 receptors (Ben-Baruch et al. 1995). A recent study in an immuno deficient murine model of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) demonstrated that CAFs secrete CCL7 which promote invasion and migration of HCC cells by enhancing TGFß pathway expression (Liu et al. 2016), suggesting it has a direct effect on cancer cells too.

CCL8/CCR1|CCR2|CCR3|CCR5

CCL8, originally named monocyte chemoattractant protein 2 (MCP2) when first discovered, is a C–C chemokine with established roles in immune cell recruitment by binding to the receptors CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, and CCR5 (Proost et al. 1996; Gong et al. 1998). Recently, it was shown that the co-culture of TNBC cell lines with fibroblasts increases CCL8 expression in fibroblasts. Following up with IHC from BC samples, CCL8 was primarily expressed by fibroblasts at the tumor margins, and that cancer cells follow the CCL8 gradient to the tumor edge before they disseminate (Farmaki et al. 2016), demonstrating a possible fibroblast-mediated role in dissemination and metastasis.

CCL18/CCR8

CCL18 is a unique chemokine because it has no natural analog in rodents, making it more tedious to study. It is known that CCL18 is primarily produced by the innate immune system, to communicate with adaptive immune cells (Bellinghausen et al. 2012), and that expression can be induced by other cell types, such as fibroblasts (Schraufstatter et al. 2012). Significant progress has been made recently in further understanding the mechanisms involved.

It was found via IHC that CCL18 expression was significantly upregulated in tumor tissue after a laparotomy, and was correlated with the number of Treg cells present. The knockdown of CCL18 in a PDX model of colon cancer reduced both tumor growth and angiogenesis, implying that CCL18 contributes to cancer progression by recruiting Treg cells and contributing to an immunosuppressive TME (Sun et al. 2019). Similarly, Su et al. demonstrated that KD of the CCL18 receptor PITPNM3 significantly reduced Treg number and inhibited cancer progression in a murine cancer model (Su et al. 2017).

Recent studies have also shown that CCL18 can affect cancer cells in different contexts. Zhao et al. demonstrated that the treatment of BC cell lines with CCL18 increases ANXA2 expression which promotes invasion and metastasis by inducing EMT through the PI3K/AKT/GSK3ß/SNAIL pathways (Zhao et al. 2020). It was also reported that treatment of BC cells with a small molecule inhibitor (SMI) of CCL18 inhibited CCL18-induced adherence and invasiveness, but interestingly did not reduce metastasis when adapted to a murine model (Liu et al. 2019b). CCL18 will continue to be difficult chemokine to study until more accurate murine models are developed, but its demonstrated role in immune recruitment suggests it is could be a promising drug target in the future.

CCL21/CCR7

CCL21, formerly known as secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC), is a less studied chemokine known to attract and recruit T cells (Mueller and Germain 2009). New studies are beginning to elucidate its multiple roles in cancer progression. In a preclinical BC murine model, Irshad et al. demonstrated that CCL21-mediated recruitment of RORγ+ group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) to tumors stimulated the production of the CXCL13 by TME stromal cells, which in turn promoted ILC3–stromal interactions and production of the cancer cell motile factor RANKL which ultimately led to lymph node metastasis (Irshad et al. 2017). In a separate murine model of BC, the stromal protein Podoplanin (PDPN) was involved in modulating the activity of CCL21/CCR7 in a hypoxia-dependant manner; and hypoxia reduced CCL21 expression in endothelial cell and increased PDPN expression in CAFs, which both reduced NK cell adhesion and assisted cancer cells in intravasation (Tejchman et al. 2017). Due to its recently discovered roles in facilitating stromal cell cross talk and intravasation, CCL21 appears to be another promising chemokine to further study.

CXCL1/CXCR2

CXCL1, known originally as GROa, is a CXC chemokine originally isolated from the supernatant of melanoma cells (Richmond and Thomas 1988), that has dual angiogenic and immune recruitment roles. With regards to immune cells, a recent study found that the inhibition of CXCL1 expression in a murine model of lung cancer led to a decrease in neutrophil recruitment in the primary tumor (Yuan et al. 2016). Similarly, using doxorubicin (DOX) or paclitaxel (PAC) resistant CI66 murine cancer cells, Wu et al. observed higher CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligand expression in resistant cells relative to normal controls, and murine experiments demonstrated an increase in neutrophil recruitment (Wu et al. 2020b), agreeing with the previous authors.

In addition to recruiting immune cells, CXCL1 also has direct stimulatory effects on cancer cells. It was found that CXCL1 treatment of BC cells increased invasion and EMT, through direct binding to the SOX4 promoter and activation of the NFKß pathway. Silencing of CXCL1 in TAMs in a murine BC model reduced tumor growth and metastatic burden, demonstrating two way communication (Wang et al. 2018b). Supporting this, CXCL1 was found to be secreted by dendritic cells in colon cancer patients, and CXCL1 treatment of CRCs enhances cell migration, and EMT, while increasing the expression of the oncogenes PTHLH, TYRP1, FOXO1, TCF4, and ZNF80 (Hsu et al. 2018). Yang et al. observed that CXCL1 is upregulated in TNBC tissues and cell lines relative to ER + counterparts. Following up, the treatment of TNBC cells with CXCL1 increased invasiveness and migration via upregulating MMP2 and MMP9, which were activated by the ERK1/2 pathways (Yang et al. 2019a). In a separate study, GNA13 overexpression in CRC cells promoted proliferation and EMT in addition to increasing the expression of angiogenic chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL4 (Zhang et al. 2018c).

Being an ELR + chemokine, CXCL1 has also been implicated in tumor vascularization, directly through binding to CXCR2 on endothelial cells, or indirectly through other stromal cells. Using an adiponectin KO murine model of pancreatic cancer, it was demonstrated that adiponectin stimulates CXCL1 secretion by cancer cells, which leads to an increase in tumor growth and vasculature, driven partially by inducing senescence in fibroblasts (Cai et al. 2016). A separate lab similarly found that the activation of RelA in a murine PDAC model promoted oncogene-induced senescence of fibroblasts via elevation of CXCL1, which activated CXCR2 in the stromal endothelial cells (Lesina et al. 2016), agreeing with the previous study. Using either drug treatments or murine cancer models, several studies have demonstrated that CXCL1 secretion by cancer cells stimulated CXCL1 expression in mesenchymal stromal cells, which binds to CXCR2 on endothelial cells to promote angiogenesis (Wang et al. 2017b; Zhang et al. 2018b; Liu et al. 2019a).

Multiple studies have used IHC in combination with patient outcomes to demonstrate correlation between poor patient outcomes and CXCL1 expression in multiple cancer types (Kasashima et al. 2017; Miyake et al. 2016; Naito et al. 2019; Wen et al. 2019). These consistent findings are due to the multifaceted role of CXCL1 in cancer-immune-fibroblast communications. Yu et al. demonstrated that TNFa-activated MSCs secrete CXCL1 and promote lung metastasis in a murine model of BC. CXCR2 ligands also increased in expression and led to the recruitment of CXCR2 + neutrophils into the tumor to create a pro-metastatic environment (Yu et al. 2017a). Across multiple murine models of cancer, CXCL1 secreted by cancer cells stimulated the migration of both stromal mesenchymal and TAMs into the tumor via interaction with CXCR2 (Miyake et al. 2016; Kasashima et al. 2016; Sano et al. 2019).

CXCL1 can also be induced in stromal cells, further emphasizing its multifaceted role in cancer progression. Naito et al. showed that extracellular vesicles from gastric cancer cell lines induce miRNA that leads to CXCL1 and CXCL8 expression in CAFs, both of which were associated with poor patient survival (Naito et al. 2019). TGFß1 expression in pancreatic cancer cells induced pancreatic stellate cells, fibroblast equivalents in the pancreas, to produce FAP and CXCL1, which promoted cancer invasion and migration through AKT phosphorylation and led to worse patient outcomes (Wen et al. 2019). This agrees with Bernard et al., who demonstrated in a murine BC model that a decrease in TGFß signaling in fibroblasts increases CXCL1 secretion, which contributes to tumor progression via activation of the AKT, STAT3, and p42/p44/MAPK pathways (Bernard et al. 2018). In a separate study, cancer-associated MSCs were shown to secrete chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL2 and induced CXCR2-dependent chemoresistance in ovarian cancer cell lines and a murine model (Le Naour et al. 2018). While these studies show the important and multifaceted roles of CXCL1 in many cancer types, significant work still needs to be done in disentangling its context-specific functions.

CXCL4/CXCR3B

CXCL4 is the first chemokine discovered and published in the literature (Deutsch et al. 1955). Originally called Platelet factor 4 (PF4), CXCL4 is an ELR- CXC chemokine that binds specifically with the CXCR3 splice variant, CXCR3B. Though CXCL4 plays known roles in angiogenesis, immune cell recruitment, and inflammation (Stoeckle and Barker 1990; Maurer et al. 2006), recent studies have provided new context of its roles in cancer progression.

In a murine model of lung adenocarcinoma, CXCL4 overexpression increased megakaryopoeiesis in the bone marrow which led to an accumulation of platelets in the lung and increased overall adenocarcinogenesis (Pucci et al. 2016). Interestingly, in CXCL4 KO lung cancer murine model, tumor metastasis occurred more frequently due to leaky vasculature and a larger MDSC population (Jian et al. 2017). Although these studies disagree, it is possible that CXCL4 both assists in carcinogenesis and inhibits metastasis, depending on the signaling context. These conflicting studies demonstrate the value in having multiple labs researching chemokines.

CXCL5/CXCR1|CXCR2

CXCL5, first named epithelial-derived neutrophil-activating peptide 78 (ENA78), is and ELR + CXC chemokine that binds to the receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 (Persson et al. 2003). CXCL5 has well documented roles in angiogenesis (Rowland et al. 2014), leukocyte recruitment, and homeostasis (Persson et al. 2003). New studies have looked at CXCL5 in other cell types such as fibroblasts, and probed deeper into the different pathways activated during the CXCL5 signaling cascade.

In cell culture experiments, CXCL5 treatment of HUVECs stimulates angiogenesis via upregulation of VEGFA, CXCR2, and the AKT/NFKß pathways (Chen et al. 2019). Conversely, in small cell lung cancer cells, CXCL5 treatment promotes cell proliferation and migration via activation of the MAPK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways (Wang et al. 2018a), suggesting that CXCL5 signals though different pathways depending on the cell type it binds to. Further bolstering the previous study, CAFs in a murine model of BC were shown to express CXCL5, which induced PDL1 expression in BC cells through the PI3K/AKT pathway (Li et al. 2019c). The overexpression of CXCL5 in CRC cell lines enhances invasion and activates EMT through the ERK/ELK1/SNAIL and AKT/GSK3B/BCAT pathways in a CCR2-dependent manner (Zhao et al. 2017). These studies demonstrate a role for CXCL5 in both angiogenesis and tumor invasion, in addition to its established role in immune cell recruitment.

CXCL6/CXCR1|CXCR2

CXCL6, originally named granulocyte chemotactic protein 2 (GCP2), is an ELR + CXC chemokine with an established role in attracting neutrophilic granulocytes by binding to the receptors CXCR1 and CXR2 (Proost et al. 1993; Wuyts et al. 1997). Recent studies suggest its effects are mediated by other cell types in addition.

In one study, the treatment of HCC cells with CXCL6 promoted invasion and migration through the activation of MMP9 (Zheng et al. 2016). In a co-culture model of CRC and fibroblasts, CXCL12 secreted from fibroblasts induced CXCL6 expression in cancer cells, which lead to enhanced invasion and angiogenesis in HUVEC cells through the activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways (Ma et al. 2017). Focusing on fibroblasts in a murine model of liver fibrosis, Kupffer cells treated with CXCL6 secreted TGFß1 which activated fibrogenic gene expression in HSCs and led to a myofibroblast phenotype through activation of the SMAD2/BRD4/C-MYC/EZH2 pathways (Cai et al. 2018). While its role in immune cell recruitment is well documented, these recent studies reveal that CXCL6 can activate both cancer cells and fibroblasts, which makes it a high interest target to study.

CXCL8/CXCR1|CXCR2

CXCL8 was originally identified as a chemotactic agent for lymphocytes and neutrophils (Larsen et al. 1989; Yasumoto et al. 1992). Originally named IL8, it was later officially renamed to CXCL8, demonstrating the close relationship between the interleukins and chemokines.

Unsurprisingly, CXCL8 expression and significance varies depending on the cancer type and subtype. IHC of CXCL8 in 62 BC patient samples shows that CXCL8 expression in ER-, but not ER + cases, is associated with poor patient outcome (Fang et al. 2017). More IHC of primary BC patient biopsies indicates that TNBC cancers express CXCL8 at higher levels than their luminal counterparts (Liubomirski et al. 2019b). In another study, the co-culture of TNBC cell lines with MSC/CAFs increased CXCL8 expression partially based on physical contact, and these co-cultures lead to increased aggressiveness, invasiveness, and metastasis in murine model, relative to Luminal A counterparts(Liubomirski et al. 2019b), reinforcing the conclusion reached by Fang et al. From a different lab, RNA-Seq from 187 CRC patients identified high CXCL8 expression in CRC patients, which also correlated positively with CREB1, RPS6KB, and negatively with BAD mRNA levels, indicating an increase in proliferation and differentiation with a decrease in apoptosis in the tumors (Li et al. 2019a).

Multiple studies have also shown that CXCL8 has a direct stimulatory effect on cancer cells. In one study, treating ESCCs with CXCL8 induced migration and invasion via activation and phosphorylation of AKT and ERK1/2 pathways (Hosono et al. 2017). In bladder cancer, it was demonstrated that CM derived from TAM-like PBMC macrophages is high in CXCL8 and increased bladder cancer cell migration via upregulation of MMP9 and VEGF (Wu et al. 2020a). In separate studies, CXCL8 treatment of HCCs (Bi et al. 2019) and OCCs (Uddin et al. 2020) promoted migration, proliferation, and invasion of both cancer types. The overexpression of CXCL8 in the LoVo CRC cell line increases proliferation and leads to an EMT phenotype via activation of the PI3K/AKT/NFKß pathways, and could be the mechanism responsible in the previous two studies (Shen et al. 2017).

Many co-culture and murine experiments have also demonstrated that CXCL8 is used to facilitate multi-way communication between immune and cancer cells. The co-culture of PDAC cells with THP-1 monocytes shows that CM from PDAC cells promotes monocyte migration, polarization, and induces secretion of both CCL2 and CXCL8. In another study, CXCL8 treatment of PDAC cells increased both migration and metastasis in a murine model, and induced cancer EMT via upregulation of TWIST and STAT3 (Chen et al. 2018). In another system, CXCL8 expression in macrophages was stimulated by the presence of HCCs, which then accelerated HCC growth and metastasis via upregulating the micro RNAs miR-18a and miR-19a (Yin et al. 2017). In a separate murine model of pancreatic cancer, cancer cells were shown to secrete CXCL8, which attracts CXCR2 + macrophages to foster an immunosuppressive environment, and could be reversed by. IFNγ treatment (Zhang et al. 2020). IFNγ treatment of PC cells inhibited proliferation and migration by suppressing CXCL8 expression via RhoGD12/Rac1/NFKß signaling pathway (Zhang et al. 2018a), agreeing with the previous study. Taken together, co-culture systems indicate that cancer cells induce CXCL8 secretion in immune cells in several different contexts, which then leads to a proinflammatory TME hospitable for cancer..

Apart from immune cells, CXCL8 is also used as a messenger to facilitate communication between cancer cells and stromal mesenchymal cells. Mano et al. observed that supernatants of cultured CAFs from HCC patients had higher levels of CCL2, BMP4, and CXCL8, relative to normal patient fibroblasts. Upon BMP4 treatment, normal fibroblasts increase expression of αSMA and CXCL8, ultimately leading to a CAF phenotype (Mano et al. 2019). Treatment of normal lung fibroblasts with leptin results similarly in increased αSMA, CCL2, CXCL8, and CXCL6 expression at protein and mRNA levels in a separate model (Watanabe et al. 2019). In a murine model of liver cancer, tumor-derived exosomal miR1247-3p converts normal fibroblasts to CAFs via downregulating B4GALT3, to activate the β1-integrin–NFKß signaling pathway to promote lung metastasis. Activated fibroblasts further promoted stemness, EMT, chemoresistance, and tumorigenicity of liver cancer cells by secreting IL-6 and CXCL8 (Fang et al. 2018). When PDAC cells are co-cultured with CAFs, they are observed to be more resistant to histone deacetylase (HDAC)-inhibitor treatment due to increased CXCL8 expression. This resistance could be reversed via inhibition of AP1 protein, hinting at a possible mechanism and therapeutic target (Nguyen et al. 2017).

Similar phenotypes and activated pathways have been observed in 2D co-culture models. The co-culture of CAFs with PDAC cell lines increases CXCL8 secretion by fibroblasts and cancer cell growth in an FGF2 ligand-dependent manner (Awaji et al. 2019). A similar study found that treatment of CAF and TNBC co-cultures with TNFa and the notch receptor activator DAPT inhibited the contact-dependent fibroblast secretion of CXCL8 (Liubomirski et al. 2019a). In a different co-culture of PSCs with PC cells, GAL3 treatment activates PSCs to produce the inflammatory cytokines CCL2, CXCL1, and CXCL8 via ITGB1 signaling and activation of NFKß (Zhao et al. 2018). Another co-culture model of MCF7 cells with fibroblasts lead to increased CXCL8 secretion from fibroblasts which then generated an EMT phenotype in the MCF7 cells (Tivari et al. 2018).

Much progress has been made recently in contextualizing the multi-faceted role of CXCL8 in cancer progression. It is able to recruit immune cells, reprogram fibroblasts to an activated CAF state, and induce EMT phenotypes in cancer cells. Decoding its role in each of these individual processes will require deeper study and collaboration between labs, but the promise of possible therapeutic targets makes it a worthwhile goal.

CXCL9/CXCR3A|CXCR3B

CXCL9, formerly known as monokine induced by gamma interferon (MIG), is a small CXC chemokine with known roles in immune cell recruitment (Gorbachev et al. 2007), tissue extravasation, and leukocyte proliferation (Tokunaga et al. 2018). It is structurally similar to the chemokines CXCL10 and CXCL11, and all three are located in close proximity on chromosome four (Lee and Farber 1996; O’Donovan et al. 1999). It functions through binding to the receptor CXCR3, which has two different isoforms of CXCR3A and CXCR3B (Ma et al. 2015). Recent studies have demonstrated newfound roles in T cell activation and proliferation (Tan et al. 2018; Gao et al. 2020), angiogenesis (Ding et al. 2016; Shen et al. 2019), and fibroblast activation (Pein et al. 2019).

IHC for CXCL9 of 577 early BC patients found that high CXCL9 is associated with high TIL numbers and poor overall survival (Razis et al. 2020) In another study, IHC from 89 HCC patients showed high CXCR3 expression is similarly associated with tumor size and metastasis. Further experiments revealed CXCL9 expression in immune cells promotes CXCR3A expression in cancer, which increases ERK1/2 phosphorylation levels in the MAPK pathway and upregulates MMP2 and MMP9, ultimately leading to invasion and migration of cancer cells (Ding et al. 2016). Furthering the immune axis, treatment of a murine model of pancreatic cancer with CXCL9 increases tumor growth and reduces the CD8 + T cell numbers without affecting any other immune cell populations. Treatment of CD8 + T cells with CXCL9 in-vitro decreased their activation and proliferation, while increasing STAT3 and RAS signaling. The inhibition of STAT3 in CD8 + T cells reversed the phenotype, implying that the mechanism of action of CXCL9 on CD8 + T cells is based on STAT3 (Gao et al. 2020). In another murine model of prostate cancer, forced overexpression of CXCL9 also increased tumor growth and reduced T cell numbers (Tan et al. 2018), agreeing with the previous study.

Even though it is less studied, recent progress is being made on the angiogenic CXCL9 signaling axis. Shen et al. demonstrated through co-culture of rat bone-marrow derived stem cells with human HUVEC cells that CXCL9 was secreted by the MSCs and inhibits angiogenesis via activation of the mTOR/STAT1 signaling pathways (Shen et al. 2019). Another study used the co-culture of CD133 + HCCs and HUVECs to show that CXCL9 protein levels increase in supernatants from direct contact cultures, and that CXCL9 additionally promotes migration and invasion in HCCs (Ding et al. 2016). These two studies indicate a possible dual role of CXCL9, that it inhibits angiogenesis in endothelial cells while increasing cancer cell invasiveness.

It was only recently that a significant role for CXCL9 in fibroblast-cancer signaling was discovered. Pein et al. use a murine model of BC to demonstrate that JNK signaling from cancer cells induces IL1α, and IL1ß expression, which binds to IL1R in stromal fibroblasts, activating NFKß signaling and increasing fibroblast expression of CXCL9 and CCXL10 that feeds forward to bind to CCR3 on cancer cells. This generates a feedback loop that leads to a pro-metastatic environment (Pein et al. 2019).

While the immune-signaling axis of CXCL9 has been established for years, new studies have demonstrated important roles in both angiogenesis and fibroblast activation. These newly discovered axes are ripe for exploration, and we expect much more will be discovered soon.

CXCL10/CXCR3A|CXCR3B

CXCL10, previously known as Interferon-gamma induced protein 10 (IP-10), is a small CXC chemokine secreted by multiple cell types including monocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, in response to interferon gamma (Luster et al. 1985). It is structurally similar to CXCL9 and CXCL11, and binds to the CXCR3 receptor. CXCL10 is known to play major roles in immune cell recruitment and angiogenesis (Angiolillo et al. 1995; Dufour et al. 2002). Recent studies have further demonstrated that CXCL10 has anti-tumoral effects (Loveridge et al. 2017; Nishina et al. 2019; Kikuchi et al. 2019), stimulates fibroblasts (Feng et al. 2018a), and induces cancer stem cell phenotypes (Kundu et al. 2019).

CXCL10, when expressed by cancer cells, has a direct effect on immune cell recruitment. Forced overexpression of CXCL10 in CRC cell lines followed by implantation into nude mice leads to decreased tumor growth and metastasis, driven by recruiting NK cells to the tumor site (Kikuchi et al. 2019). In a similar case, an orthotopic mouse model of CRC demonstrates a protective and anti-metastatic role of intratumoral CXCL10 expression, mediated mainly by adaptive immunity from T and B cells (Kistner et al. 2017). Similar results were observed in a PTEN/ERK5 null mouse model of prostate cancer, where loss of Erk5 and Pten leads to increased CCL5 and CXCL10 expression within the malignant tumor epithelium. This in turn is associated with recruitment of T cells, predominantly CD4, to the tumor epithelium and distinct sites within the stroma, resulting in prolonged survival for the mice (Loveridge et al. 2017). A separate study demonstrated that the inhibition of DPP4, a cell-surface enzyme that cleaves active CXCL10, suppresses HCC development through recruitment of activated lymphocytes into the tumor (Nishina et al. 2019). These four studies together demonstrate that CXCL10 has an anti-tumoral effect based on recruiting beneficial immune cells, in multiple contexts.

More recent studies have shown that fibroblasts both secrete and respond to CXCL10. Treatment of pancreatic cancer and CAF co-cultures with paclitaxel induces CXCL10 secretion by cancer cells, which decreases IL6 secretion in CAFs (Feng et al. 2018a). The co-culture of adipose-derived MSC engineered to overexpress CXCL10 with melanoma cells leads to inhibited tumor cell growth. When both cells are injected into nude mice, those injected with CXCL10-overexpressing MSC showed prolonged survival driven by less infiltration of Tregs and restricted angiogenesis (Mirzaei et al. 2018). The treatment of pulmonary fibroblasts with TNFα and IL1ß leads to increased CXCL10 expression mediated through phosphorylation of STAT3, FAK, GSK3α/ ß and PKCD. Treatment of macrophages with CM from CXCL10 treated fibroblasts induced iNOS and CD86 expression in macrophages, leading to an M1 polarized phenotype (Tsai et al. 2019). In these studies, CXCL10 facilitates three-way communication between cell types, and changes fibroblast behavior, leading to immune cell polarization.

In other contexts, CXCL10 has a direct effect on cancer cells, and can lead to feed-forward loops. One study found that 4T1 BC cells secrete CXCL10 while growing, which binds to its own CXCR3 and creates a positive feedback loop through the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway (Jin et al. 2017). In another study, the treatment of BC cells with CXCL10 and CXCL11 directly induced cancer stem cell and EMT phenotypes through STAT3/ERK1/2, CREB, and NOTCH1 pathway activations (Kundu et al. 2019). A. canaliculatum ethanolic extract (ACE) treatment of TNBC cells similarly attenuated TNFα-induced upregulation of CXCL10 and CXCR3 expression at the gene promoter level. This inhibited TNFα-induced phosphorylation of inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase (IKK), IκB and p65 RelA, leading to the suppression of nuclear translocation of p65/RelA nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) (Choi et al. 2018). CXCL10 mechanistically functions through multiple pathways in cancer cells, and more studies will be needed to contextualize those pathways.

CXCL12/CXCR4

CXCL12, formerly known as Stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1), is one of the most extensively studied chemokines in many different contexts of cancer. It was first discovered in the context of embryogenesis (Bleul et al. 1996), but was then found to be continuously expressed in bone marrow, leading to its original name (Nagasawa et al. 1996). In the context of cancer, CXCL12 regulates angiogenesis (Ziegler et al. 2016; Song et al. 2018; Qian et al. 2018; Ma et al. 2018), assists in intravasation (Schwenk et al. 2017; Ahirwar et al. 2018), enhances cancer invasiveness (Zeng et al. 2017; Bhagat et al. 2019), and facilitates multi-way communication between cancer, endothelial, and immune cells (Costa et al. 2018; Benedicto et al. 2018). Multiple recent reviews specifically cover the CXCL12 signaling axis in cancer (Yu et al. 2018; Meng et al. 2018; Janssens et al. 2018a, b; Janssens et al. 2018a, b; Zhou et al. 2019) in great detail, which further emphasizes how important this single chemokine is. In this review, I will focus on recent studies that demonstrate the complex and multifaceted role of CXCL12 in the context of different cancers.

Interestingly, CXCL12 has a well documented angiogenic effect, while missing an ELR motif that other pro-angiogenic chemokines have. In both 3D and murine CRC models, cancer cells secrete CXCL12, which activates CXCR4 signaling on endothelial cells, leading to mTORC2 activity through the PI3K pathway. It was shown that only mTORC2 was required for microvascular sprouting, and inhibition of mTORC2 was sufficient to decrease tumor volume and angiogenesis (Ziegler et al. 2016). Similarly, CXCL12 treatment of HUVECs increased EGFR, VEGF, and MMP2 expression, which stimulated angiogenesis through the upregulation of the MAPK/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways, partially agreeing with the previous study (Song et al. 2018). Similar results were seen when the CXCL12 used was derived from BC cell lines, rather than the purified ligand (Martinez-Ordoñez et al. 2018). A second receptor to CXCL12, CXCR7 or ACKR3, has also been shown to mediate communication between endothelial cells and cancer cells. The inhibition of CXCR7 by the compound CCX771 in MDA-MB-231 BC cells reduced invasion, adhesion, metastasis, and VEGF expression. Additionally, CXCR7 inhibition of HUVECs prevented tube and blood vessel formation, indicating CXCR7 is required for angiogenesis in this context (Qian et al. 2018).

In addition to angiogenesis, recent studies have started to explore the role of CXCL12 in the other endothelial context of intravasation. In a murine model of BC with CXCL12-ablated fibroblasts, CXCL12 was shown to enhance permeability by recruiting endothelial precursor cells and decreasing endothelial tight junction and adherens junction proteins (Ahirwar et al. 2018). In another study, treatment of HUVEC cells with the microtubule targeting agent pretubulysin (PT) increased adhesion of TNBC cells to HUVEC rather than translocation through them. PT treatment induced CXCL12 expression, and the tumor cells preferentially adhered to collagen exposed within PT-triggered endothelial gaps via β1-integrins on the tumor cell surface (Schwenk et al. 2017).

Recent studies have also shown that CXCL12 strongly attenuates cancer invasiveness, often in cooperation with signals from stromal cells such as fibroblasts and stellate cells, and through multiple different pathways. CAFs isolated from a BC metastasis to the brain were shown to attract BC cells through secretion of CXCL12 and CXCL16 (Chung et al. 2017). The co-culture of TNBC cells and HMFs induces CXCL12 expression in fibroblasts, leading to enhanced proliferation and invasion in TNBC cells through activation of the CXCR4 receptor (Plaster et al. 2019). On a similar axis, the co-culture of TNBC cells with CXCR4 + and CXCR7 + HMFs significantly increases the growth of TNBC cells and drug resistance through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways (Ham et al. 2018). CXCL12 expression in fibroblasts can be attenuated by co-culture with TGFß1-KO melanoma cells, indicating another pathway upstream of CXCL12 (Moore-Smith et al. 2017). In an orthotopic murine prostate cancer model, the CXCL12-CXCR7 axis was found to accelerate the migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells through the phosphorylation of the mTOR and Rho/ROCK pathways (Guo et al. 2016). The downregulation of CXCL12 in PCs via treatment with Acetyl-L-carnitine conversely impairs cancer cell migration (Baci et al. 2019). Similarly, silencing the CXCL12 gene in CRCs significantly inhibited proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis via down-regulation of the MAPK/PI3K/AP1 signaling pathways (Ma et al. 2018). In another murine model, sustained expression of CXCL12 by MSCs in the primary tumor inhibits metastasis by downregulating CXCR7 in tumor cells, and could be reversed treatment with TGFß (Yu et al. 2017b).

Other studies have helped to confirm that CXCR4 is responsible for the increased invasiveness observed in these previous studies. Forcing CXCR4 overexpression in A549 cells leads to increased invasiveness through the increased expression of VEGF-C, MMP2, and phosphorylation of AKT (Zeng et al. 2017). A different group repeated the experiment and found similar results that could be reversed by treatment with a CXCR4 inhibitor (He et al. 2018). The co-culture of CAFs with PDAC cells similarly increases invasiveness, which can be nullified by the inhibition of CXCR4 (Bhagat et al. 2019), although the authors left the responsible pathway unspecified. Another lab observed that the overexpression of CXCR4 also promotes invasion and migration of non‑small cell lung cancer via activating EGFR and MMP9 (Zuo et al. 2017). The overexpression of FOXC1 in TNBC cells increases invasion and motility via upregulation of CXCR4 (Pan et al. 2018), further confirming the relationship between invasiveness and CXCR4.

In addition to its roles in endothelial and fibroblast signaling, CXCL12 plays an important role in immune cell recruitment, often mediated by coordinating with other cell types. In a recent study, pre-treatment of HCCs with a CXCR4 inhibitor before injecting them into nude mice resulted in reduced liver metastasis, and a smaller CD11b + Ly6G + MDSC population (Benedicto et al. 2018). Another study, using RNA-Seq of TNBC patients identified a FB subtype that secretes CXCL12 and attracts CD4 + CD25 + T cells to promote their differentiation to Tregs (Costa et al. 2018). Using a Fgl2-KO murine model of lung cancer, it was demonstrated that Fgl2 increased expression of FAP, PDGFRα, and CXCL12 expression in CAFs which led to an overall increase in MDSC cells in those systems (Zhu et al. 2017). In an orthotopic murine CRC model, targeting CXCR4 increases the efficacy of the anti-angiogenic compound ramucirumab by reducing the accumulation of CXCR4-dependent Ly6C-low monocytes (Jung et al. 2017), further indicating that communication between multiple different cell types assists in recruiting immune cells.

Despite its varied and multifaceted function, recent studies of drug treatments and murine KO models have started to elucidate the mechanisms through which CXCL12 functions. In a RhoA KD murine model of TNBC, expression of CCL5 and CXCL12 in CAFs located in the primary tumor is increased, which ultimately generates a pro-metastatic niche in other organs (Kalpana et al. 2019). Gefitinib treatment of an EGFR-mutant PC9 lung cancer cell line promoted migration and EMT by upregulating CXCR4 via TGFß1/Smad2 activity (Zhu et al. 2020). Cordycepin treatment inhibited the nuclear translocation of P65 by preventing p-IκBα activation; this resulted in the downregulation of CXCR4 expression, and subsequently, in the impaired migration and invasion abilities of liver cancer cells and attenuated reactivity to CXCL12 (Guo et al. 2020). The treatment of TNBC cell lines with CXCL12 induced a Ca2 + response in the more metastatic lines that also expressed more CXCR4 and CXCR7. The transcriptional regulation of CXCR4 may differ depending on the EMT stimuli and may not be a fundamental characteristic of a more mesenchymal state (Jamaludin et al. 2018). Using the both the native AR ligand dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and flagellin, treatment of prostate cancer cell lines demonstrated that down regulation of the CXCR7 protein by DHT and flagellin increased migration, supporting CXCR7 as decoy receptor counteracting CXCL12/CXCR4-mediated migration in prostate cancer cells (Yu et al. 2020). AMD3100 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition and migration of PC cells by inhibiting the CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling pathway (Zhu et al. 2019). Fisetin inhibits the growth and migration of the A549 human lung cancer cell line via CXCR4 and the ERK1/2 pathway (Wang and Huang 2018). In a murine model of BC, downregulation of TAGLN2 promoted metastasis by reducing expression PRDX1 which led to ROS production and NFKß activation, which induced CXCR4, MMP1, and MMP2 expression (Yang et al. 2019b). Treatment of CAFs isolated from pancreatic cancer patients with the isolated compound conophyline reduces secretion of CCL2, CXCL8, and CXCL12, and also desmoplasia in a murine model though an unexplored mechanism (Ishii et al. 2019).

Although CXCL12 is one of the most studied chemokines in terms of papers published, there are still many unknowns about that need to be solved. Having a highly specific CXCR4 inhibitor, AMD3100, has been and will continue to be a boon for labs looking to further determine the pathways through which CXCL12 and CXCR4 work through. Due to its multifaceted role in multiple processes of cancer progression, more studies and collaborations will be required to fully assess and develop therapeutics targeting this chemokine and receptor pair.

CXCL14/??? (Orphan chemokine, unknown receptor)

CXCL14 is an ELR- CXC chemokine that plays a role in immune cell recruitment through an unknown receptor (Lu et al. 2016). While not having a known receptor makes it challenging to study, it also offers a great reward, and several recent studies have gained insight into its possible mechanisms.

IHC from 106 NSCLC tumor specimens showed correlation with stromal CXCL14 and NOS1 expression in cancer cells. In this study, high stromal CXCL14 expression was associated with poor patient outcomes, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic target (Ji et al. 2018). In a mouse model of BC with CXCL14 over/underexpressing fibroblasts, CXCL14 overexpressing fibroblasts stimulated BC EMT, migration, and invasion, mediated by but not binding to ACKR2 on the cancer cells (Sjöberg et al. 2019). Another co-culture model of CAFs and BC cells shows that CAFs stimulate secretion of CCL11 and CXCL14 in BC cells, accelerating tumor growth, and contributing to drug resistance through the p38-STAT1 pathway (Liu et al. 2017). These recent studies indicate CXCL14 has a more complex role in cancer signaling than just immune cell recruitment, and is a promising target for further research.

CXCL17/CXCR8

CXCL17 is an orphan chemokine receptor that is known to attract dendritic cells and monocytes (Pisabarro et al. 2006; Weinstein et al. 2006). A recent study using a murine model of BC has demonstrated that BC cells secrete CXCL17 which increases the accumulation of CD11b + Gr-1 + MDSCs in the lungs. MDSCs attracted to CXCL17 expressed PDGF-BB which then activates stroma and increases angiogenesis while creating an overall pro-metastatic environment (Hsu et al. 2019). In another study with HCC cell lines, Wang et al. demonstrated that the upregulation of CXCL17 promotes proliferation, invasion, and migration, and suppresses autophagy through the LKB1-AMPK pathway (Wang et al. 2019). These studies demonstrate a multi-faceted role of CXCL17 in cancer communication, with much more room to be explored.

Conclusions and future directions

The summation of recent studies in this review reveals a multifaceted and tangled web of functions for chemokines and their receptors, in the context of cancer-stroma communication in the tumor. Chemokines attract specific immune cell subtypes, induce proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and drug resistance, in almost every cancer type studied so far. It is likely that new research will implicate chemokines and their receptors in new and less studied roles, such as metabolic reprogramming (Mateo 2019; Chen et al. 2020) and transdifferentiation (Heneberg 2016; Li et al. 2018).

Even though we have started to learn the specific effects that some chemokines and their receptors play in the tumor microenvironment, progress in using that information to therapeutically target them has been slow moving. This is likely due to two factors. First, chemokines play a role in overall homeostasis in the body in addition to the role they play in the TME. Targeting a chemokine-receptor pair in cancer could lead to indirect side-effects in other tissues in the body. Second, as briefly mentioned and shown in this review, there is extreme redundancy in many chemokines and receptors, where multiple chemokines bind to multiple receptors, and multiple receptors accept multiple chemokines as their ligands. This makes it incredibly difficult to specifically target one single receptor-pair at once, and also can lead to unwanted, indirect effects.

Moving forward, there is plenty of work and research that can be done to further increase our understanding of chemokine signaling in the tumor TME. Among the most important will be understanding what leads the same chemokine-receptor pair to induce the expression of different pathways in different contexts and cell types. Currently, it is not known what imparts this molecular function to chemokines and receptors, although it likely involves conformational state changes (Allen et al. 2007). To study this phenomenon, experiments will have to be carefully designed using specific and relevant cell types in combination with specific inhibitors of the receptors. The choice of model systems will also be greatly important, as some chemokines might have slightly different effects in humans vs mice, or in 3D cultures vs 2D. In the upcoming years, we expect significant progress in answering these questions and others, especially as new technologies are developed and made more widely available, such as protein quantification via reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) and mRNA abundance via single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq). There are very few papers in the literature currently that use scRNA-Seq in conjunction with chemokine stimulation or inhibition, and such a system would be a powerful way to probe the perturbed downstream pathways. These types of experiments, executed meaningfully and carefully, could assist in identifying molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets within the larger chemokine network, in the context of the TME.

Funding

Funding for this review was provided by OCSSB at Oregon Health and Sciences University, and by the 2019 PhRMA Foundation post-doctoral fellowship in translational medicine and therapeutics

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahirwar DK, Nasser MW, Ouseph MM, et al. Fibroblast-derived CXCL12 promotes breast cancer metastasis by facilitating tumor cell intravasation. Oncogene. 2018;37:4428–4442. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0263-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SJ, Crown SE, Handel TM. Chemokine: receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:787–820. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angiolillo AL, Sgadari C, Taub DD, et al. Human interferon-inducible protein 10 is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;182:155–162. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo JM, Gomez AC, Aguilar A, et al. Effect of CCL5 expression in the recruitment of immune cells in triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4899. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23099-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awaji M, Futakuchi M, Heavican T, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts enhance survival and progression of the aggressive pancreatic tumor via FGF-2 and CXCL8. Cancer Microenviron. 2019;12:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s12307-019-00223-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baci D, Bruno A, Cascini C, et al. Acetyl-L-Carnitine downregulates invasion (CXCR4/CXCL12, MMP-9) and angiogenesis (VEGF, CXCL8) pathways in prostate cancer cells: rationale for prevention and interception strategies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:464. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1461-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartneck M, Schrammen PL, Möckel D, et al. The CCR2+ Macrophage Subset Promotes Pathogenic Angiogenesis for Tumor Vascularization in Fibrotic Livers. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7:371–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinghausen I, Reuter S, Martin H, et al. Enhanced production of CCL18 by tolerogenic dendritic cells is associated with inhibition of allergic airway reactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1384–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Baruch A, Xu L, Young PR, et al. Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-3 (MCP3) interacts with multiple leukocyte receptors: C-C CKR1, a receptor for macrophage inflammatory protein-1α/RANTES, is also a functional receptor foR MCP3. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22123–22128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedicto A, Romayor I, Arteta B. CXCR4 receptor blockage reduces the contribution of tumor and stromal cells to the metastatic growth in the liver. Oncol Rep. 2018;39:2022–2030. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard S, Myers M, Fang WB, et al. CXCL1 derived from mammary fibroblasts promotes progression of mammary lesions to invasive carcinoma through CXCR2 dependent mechanisms. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2018;23:249–267. doi: 10.1007/s10911-018-9407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat TD, Von Ahrens D, Dawlaty M, et al. Lactate-mediated epigenetic reprogramming regulates formation of human pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts. Elife. 2019 doi: 10.7554/eLife.50663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi H, Zhang Y, Wang S, et al. Interleukin-8 promotes cell migration via CXCR1 and CXCR2 in liver cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:4176–4184. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleul CC, Fuhlbrigge RC, Casasnovas JM, et al. A highly efficacious lymphocyte chemoattractant, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) J Exp Med. 1996;184:1101–1109. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borish LC, Steinke JW. 2. Cytokines and chemokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:S460–S475. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett E, Sauter M, Timmins É, et al. Oncogenic linear collagen VI of invasive breast cancer is induced by CCL5. J Clin Med Res: 2020 doi: 10.3390/jcm9040991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Xu S, Piao C, et al. Adiponectin induces CXCL1 secretion from cancer cells and promotes tumor angiogenesis by inducing stromal fibroblast senescence. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55:1796–1806. doi: 10.1002/mc.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Li Z, Zhang Q, et al. CXCL 6-EGFR-induced Kupffer cells secrete TGF-β1 promoting hepatic stellate cell activation via the SMAD 2/BRD 4/C-MYC/EZH 2 pathway in liver fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:5050–5061. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2019) CDC—Expected New Cancer Cases and Deaths in 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/research/articles/cancer_2020.htm. Accessed 24 Jul 2020

- Cecchinato V, Uguccioni M. Insight on the regulation of chemokine activities. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104:295–300. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MR0118-014R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang Y, Nelson D, et al. CCL2/CCR2 regulates the tumor microenvironment in HER-2/neu-driven mammary carcinomas in mice. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0165595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Liu Q, Tsang LL, et al. Human MSCs promotes colorectal cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition and progression via CCL5/β-catenin/Slug pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e2819. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S-J, Lian G, Li J-J, et al. Tumor-driven like macrophages induced by conditioned media from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma promote tumor metastasis via secreting IL-8. Cancer Med. 2018;7:5679–5690. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Xu Z-Q, Zong Y-P, et al. CXCL5 induces tumor angiogenesis via enhancing the expression of FOXD1 mediated by the AKT/NF-κB pathway in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:178. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1431-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Tan L, Liao Y, et al (2020) Chemokine CCL2 impairs spatial memory and cognition in rats via influencing inflammation, glutamate metabolism and apoptosis-associated genes expression-a potential mechanism for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Life Sci 117828 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choi J, Ahn SS, Lim Y, et al. Inhibitory effect of alisma canaliculatum ethanolic extract on NF-κB-dependent CXCR3 and CXCL10 expression in TNFα-exposed MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijms19092607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow MT, Luster AD. Chemokines in cancer. Cancer. Immunol Res. 2014;2:1125–1131. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung B, Esmaeili AA, Gopalakrishna-Pillai S, et al. Human brain metastatic stroma attracts breast cancer cells via chemokines CXCL16 and CXCL12. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2017;3:6. doi: 10.1038/s41523-017-0008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioni B, Nevedomskaya E, Melis MHM, et al. Loss of androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) promotes CCL2-and CXCL8-mediated cancer cell migration. Mol Oncol. 2018;12:1308–1323. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Kieffer Y, Scholer-Dahirel A, et al. Fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppressive environment in human breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:463–479.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demircioglu F, Wang J, Candido J, et al. Cancer associated fibroblast FAK regulates malignant cell metabolism. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1290. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15104-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:313–326. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch E, Johnson SA, Seegers WH. Differentiation of certain platelet factors related to blood coagulation. Circ Res. 1955;3:110–115. doi: 10.1161/01.res.3.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]