Abstract

Introduction

Conflicting reports of increases and decreases in rates of preterm birth (PTB) and stillbirth in the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic have surfaced. The objective of our study was to conduct a living systematic review and meta‐analyses of studies reporting pregnancy and neonatal outcomes by comparing the pandemic and pre‐pandemic periods.

Material and methods

We searched PubMed and Embase databases, reference lists of articles published up until 14 May 2021 and included English language studies that compared outcomes between the COVID‐19 pandemic time period and pre‐pandemic time periods. Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. We conducted random‐effects meta‐analysis using the inverse variance method.

Results

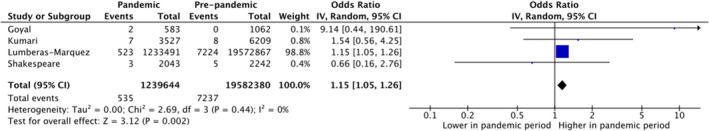

Thirty‐seven studies with low‐to‐moderate risk of bias, reporting on 1 677 858 pregnancies during the pandemic period and 21 028 650 pregnancies during the pre‐pandemic period, were included. There was a significant reduction in unadjusted estimates of PTB (28 studies, unadjusted odds ratio [uaOR] 0.94, 95% confidence [CI] 0.91–0.98) but not in adjusted estimates (six studies, adjusted OR [aOR] 0.95, 95% CI 0.80–1.13). The reduction was noted in studies from single centers/health areas (uaOR 0.90, 95% CI 0.86–0.94) but not in regional/national studies (uaOR 0.99, 95% CI 0.95–1.03). There was reduction in spontaneous PTB (five studies, uaOR 0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.98) and induced PTB (four studies, uaOR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81–1.00). There was no reduction in PTB when stratified by gestational age <34, <32 or <28 weeks. There was no difference in stillbirths between the pandemic and pre‐pandemic time periods (21 studies, uaOR 1.08, 95% CI 0.94–1.23; four studies, aOR 1.06, 95% CI 0.81–1.38). There was an increase in birthweight (six studies, mean difference 17 g, 95% CI 7–28 g) during the pandemic period. There was an increase in maternal mortality (four studies, uaOR 1.15, 95% CI 1.05–1.26), which was mostly influenced by one study from Mexico. There was significant publication bias for the outcome of PTB.

Conclusions

The COVID‐19 pandemic time period may be associated with a reduction in PTB; however, referral bias cannot be excluded. There was no difference in stillbirth between the pandemic and pre‐pandemic period.

Keywords: birthweight, epidemic, maternal mortality, neonatal mortality, preterm birth, SARS‐CoV‐2, stillbirth, stress

Abbreviations

- ELBW

extremely low birthweight

- GA

gestational age

- LBW

low birthweight

- PTB

preterm birth

- VLBW

very low birthweight

Key message.

Population‐level preterm birth may have declined during the pandemic but there was no difference in stillbirths. The reduction was only noted in single‐center studies and in unadjusted estimates, raising the possibility of referral bias and need for further data.

1. INTRODUCTION

Although most pregnancies end with healthy mothers and healthy children, a small proportion result in adverse outcomes for the mother, fetus or neonate. Among others, such outcomes include stillbirth, preterm birth (PTB), neonatal mortality and maternal mortality—all of which can have devastating and long‐lasting effects on families. 1 , 2 , 3 Preterm birth (birth before 37 weeks’ gestation) is a major determinant of neonatal mortality and morbidity 4 with long‐term adverse consequences during childhood and adulthood. 5 Medical, social, psychological, environmental and economic factors have all been implicated in the etiopathogenesis of PTB and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had an unprecedented impact on society worldwide and has provided a natural experiment allowing us to study the effects of these factors on adverse pregnancy outcomes. During the early stages of the pandemic, reports emerged describing reduced PTB rates in Denmark 6 and Ireland. 7 However, these were followed by reports of increased PTB rates (births between 28 and 32 weeks’ gestation) in Nepal 8 and no changes in PTB rates in the UK 9 and Sweden. 10 At the same time, increases in stillbirth rates were reported from the UK 9 and Nepal, 8 with or without changes in PTB rates, while no change in the stillbirth rate was reported from Ireland. 2

In light of these mixed reports, it is uncertain whether the COVID‐19 pandemic has affected pregnancy outcomes at the population level. Inconsistency among conclusions from different studies and a lack of evidence to inform the creation of evidence‐based population health guidance prompted us to undertake a comprehensive review of the influence of the COVID‐19 pandemic on pregnancy outcomes. Our objective was systematically to review and meta‐analyze studies reporting defined local, regional or national population‐based rates for maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes during the pandemic period compared with the pre‐pandemic period.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

The review was conducted using standardized methods for systematic reviews of observational studies and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses guidelines. 11 No ethical approval was obtained, as all data used for these analyses were published previously. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021234036). 12

2.1. Data sources: search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed and Embase databases, reference lists of included articles, and personal files for studies published up to 14 May 2021. The search strategy used a combination of the MeSH terms “preterm” or “stillbirth” AND “Covid19” or “SARS‐COV‐2” and included any type of study design published in the English language (Appendix S1). Since this is a living systematic review, it will be updated 3‐monthly for the duration of the pandemic, using the same search strategy. Studies were included if they compared pregnancy outcomes between the COVID‐19 pandemic time period versus pre‐pandemic time periods and reported on any of the outcomes of interest. We excluded studies that only reported outcomes of pregnant women with COVID‐19 infection. Screening of articles was conducted by two authors (PS and JY) and disagreements were resolved through discussion (JY, RD and PS) and consensus. Since we were interested in overall pregnancy outcomes, we did not restrict studies based on plurality (included singleton and multiple pregnancies).

2.2. Exposure

In most studies, the pandemic period was defined as the period of time beginning from the date or month of the implementation of emergency lockdown measures in relevant countries or states or cities, or when there was an emergence of cases or a surge of cases in the population studied. Some studies assessed the “post‐lockdown” period, which for the purpose of this study was included as “pandemic” period, as we are still not out of pandemic. The pre‐pandemic period was defined either as the period ending immediately before lockdown measures were implemented or before the emergence of the first case or high case numbers in the population, or as a historical period, such as births in the same population in previous year(s). The lengths of these periods varied across studies.

We included studies that reported outcomes of pregnancy in general population. The review was not designed to evaluate outcomes of pregnancies where only women were affected by SARS‐CoV‐2 infection were reported.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcomes in this study were rates of PTB and stillbirth. Secondary outcomes included mean birthweight (continuous) and rates of low birthweight (LBW), spontaneous PTB, medically indicated PTB, and neonatal, perinatal or maternal mortality. We contacted authors to obtain data on stillbirth and neonatal mortality when the outcomes were reported as “intrauterine fetal death” (IUFD) and “perinatal mortality”. The outcomes of IUFD and perinatal mortality, though specified in the protocol, were not included ultimately in review (deviation from protocol). Outcomes were defined as follows:

Preterm birth: Live births between 22+0 and 36+6 weeks’ gestation were classified as PTB. Data on PTB at <28 weeks’, <32 weeks’ and <34 weeks’ gestation were reported separately in some studies and were analyzed independently.

Stillbirth: Death before the complete expulsion or extraction from the parturient of a product of human conception at or after 20 weeks’ gestation. 13

Birthweight: Infant weight in grams, measured as soon as possible after live birth. Birthweight <2500 g was defined as LBW, birthweight <1500 g was defined as very low birthweight (VLBW), and birthweight <1000 g was defined as extremely low birthweight (ELBW).

Spontaneous PTB: Birth of a baby between 22+0 and 36+6 weeks’ gestation following spontaneous preterm labor or preterm pre‐labor rupture of membranes. 3

Medically indicated PTB: Preterm birth initiated by a healthcare provider for maternal or fetal indications. 3

Neonatal mortality: Death of a newborn due to any cause before 28 days of age.

Maternal mortality: Death of a woman either during pregnancy or childbirth from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management, or within 42 days of end of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy. 9

2.4. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

Data from the eligible studies were independently extracted by two authors (JY and PS) using a predefined, standardized extraction form. Disagreements between the authors were resolved by consensus and involving a third author (RD). The information extracted included details of the publication, study setting and size, pre‐pandemic period definition, pandemic period definition, and rates of the reported outcomes in pre‐pandemic and pandemic time periods. We relied only on published information.

We anticipated that primarily observational studies would be included in this review; thus, we used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale 14 for cohort studies to assess risk of bias. This scale assesses risk of bias in domains of selection, comparability and outcomes, and assigns a maximum score of 9. Studies with scores of 0–3 were considered to have a high risk of bias, those with scores of 4–6 a moderate, and those with scores of 7–9 a low risk.

2.5. Statistical analyses

We planned for meta‐analyses of studies that reported similar outcomes and were methodologically homogeneous. For binary outcomes, we calculated the summary unadjusted odds ratios (uaOR), adjusted OR (aOR) when available and 95% confidence intervals (CI), whereas for birthweight we calculated the mean difference (MD) and 95% CI. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic and quantified by calculating the I 2 values. We expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity between studies and thus planned a priori for random effect meta‐analyses using the inverse variance method. We planned to meta‐analyze adjusted estimates from studies that reported them, understanding that studies will have adjusted for different factors based on data availability and baseline differences. We also expected that the duration of the “pre‐pandemic” period would vary across studies; we therefore conducted meta‐regression on the variable “duration of the pre‐pandemic period” as a covariate to explain any heterogeneity in the results. Post‐hoc subgroup analyses were conducted for the two primary outcomes after dividing studies into single‐center (or selected hospitals/centers in an area), regional (statewide or province‐wide) or national in scope. Publication bias was assessed qualitatively using funnel plots, and quantitatively by calculating Egger’s regression intercept when >10 studies were included in the meta‐analyses. For the Egger test, values of <0.10 were considered indicative of publication bias. Meta‐analyses were conducted using Stata v11.0 (Statacorp 2009, College Station, TX, USA) and Review Manager v5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark).

3. RESULTS

3.1. General study characteristics

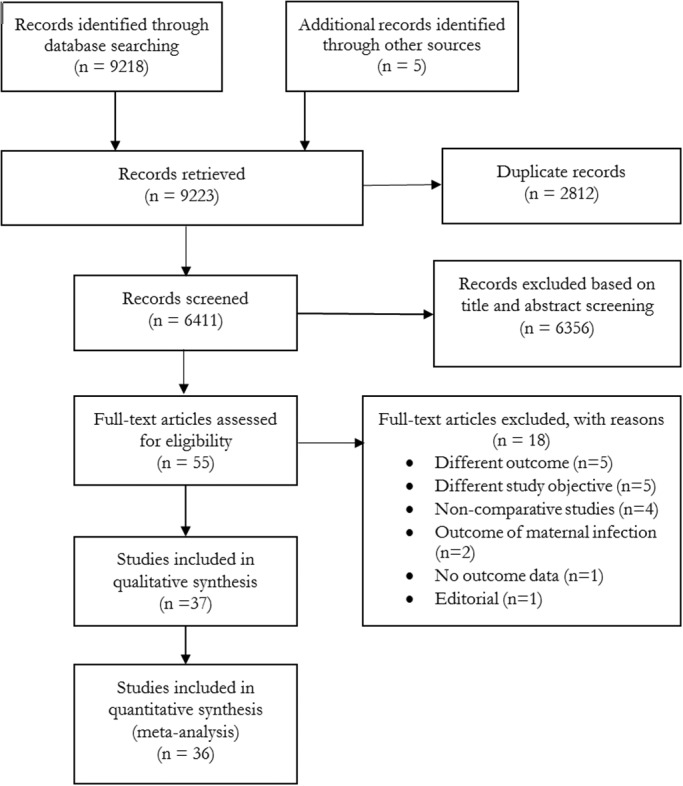

Of 9123 records in the initial search, 37 articles were eligible for inclusion, of which 36 were used in the quantitative synthesis 2 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 (Figure 1). Eighteen full‐text reports were excluded: reasons for the exclusions are provided in Appendix S2. For one study conducted in the Netherlands by Been et al., 45 data were presented using multiple cut‐offs to define the pre‐ and post‐pandemic periods, with several different comparisons, making it difficult to select one comparison that aligned well with the other studies; we therefore included this study in the systematic review but not in meta‐analyses. Khalil et al. 9 had data for stillbirth outcome that overlapped with another study; however, preterm birth data were not overlapping, so only preterm birth data were used in this review. Study characteristics are reported in Table 1: six studies were national in scope, seven were regional, and 24 were local, including single‐center studies. Across the included studies, 1 677 858 pregnancies during the pandemic period (excluding numbers from Been et al. 45 ) and 21 028 650 pregnancies during the pre‐pandemic period were studied. Duration of the “pandemic period” studied varied from 4 weeks to 7 months, and duration of the “pre‐pandemic period” studied varied from 2 months to 19 years. The risk of bias assessment scores for the included studies ranged from 5 to 9 (Table 2). Twenty studies had moderate risk of bias and 17 studies had low risk of bias. Twenty‐nine studies included a pregnant population from local/regional/national data which may have included those with COVID‐19 infection, whereas eight studies specifically excluded women with COVID‐19 infection if it was known. However, it is difficult to be completely certain, as testing on pregnant women was not universally applied in any of the studies.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram: article selection

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First Author, Country | Population level | Neonatal | Exposed cohort (Pandemic period) | Non‐exposed cohort (Pre‐pandemic period) | Outcomes | Statistical approach | Factors adjusted for, if any |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arnaez, 15 Spain |

13 regional hospitals | Singleton | 15 March–3 May 2020 | 15 March–3 May 2015 −2019 |

PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Stillbirth; LBW; VLBW; ELBW |

Joinpoint regression analysis; Multivariate binomial logistic regression models | Hospital, sex, type of delivery and multiples |

|

Been, 45 Netherlands |

Nationwide | Singleton |

1 month, 2 months, 3 months and 4 months after 9 March 2020; 1 month, 2 months, 3 months and 4 months after 15 March 2020; 1 month, 2 months, 3 months and 4 months before 23 March 2020 |

1 month, 2 months, 3 months and 4 months before 9 March 2020; 1 month, 2 months, 3 months and 4 months before 15 March 2020 1 month, 2 months, 3 months and 4 months before 23 March 2020 |

PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks |

Difference‐in‐regression‐discontinuity analysis | |

|

Berghella, 16 USA |

Single center | Singleton | 1 March – 31 July 2020 | 1 March – 31 July 2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Stillbirth; Spontaneous PTB; Medically indicated PTB | Chi square test; multivariable logistic regression | |

|

Caniglia, 17 Botswana |

Nationwide | Singleton | 3 April –20 July 2020 | 3 April– 20 July 2017–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; Stillbirth; Neonatal mortality | Difference‐in‐differences | |

|

De Curtis, 18 Italy |

Single center | Singleton | March–May 2020 | March–May 2019 |

PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; Stillbirth |

Z test | |

|

Dell’Utri, 19 Italy |

Single center | Not reported | 23 February–24 June 2020 | 23 February–24 June 2019 | Stillbirth | Chi‐square test | |

|

Du, 20 China |

Single center | Singleton | 20 January–31 July 2020 | 20 May–30 November 2019 | PTB <37 weeks; Stillbirth; LBW | Chi‐square test; t test; Univariate and multivariate log‐binomial regression models | Age, ethnicity, occupation, education, gravidity, parity, h/o miscarriage, h/o induced abortion, BMI, GWG, f/h chronic diseases, prenatal visits |

|

Goyal, 21 India |

Single center | Not reported | 1 April –30 August 2020 | 1 October 2019–29 February 2020 | Maternal mortality | Chi‐square test; Student’s t test | |

|

Greene, 22 USA |

Single center | Not reported | March–April 2020 | January–February 2020 | PTB <37 weeks |

Student’s t test; Wilcoxon test; Chi‐square test; Fisher’s exact test |

|

|

Gu 23 China |

Single center | Not reported | January–February 2020 | January–February 2019 |

PTB <37 weeks; Stillbirth; Birthweight |

t test; Chi‐square test | |

|

Handley, 24 USA |

2 Penn Medicine hospitals in Philadelphia | Singleton | March–June 2020 | March–June 2018–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; Stillbirth; Spontaneous PTB; Medically indicated PTB | Fisher exact | |

|

Harvey, 25 USA |

Regionwide | Not reported | 22 March–30 April 2020 | 22 March–30 April 2015–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; LBW; VLBW | Logistic regression models | Maternal age, education, race/ethnicity, diabetes, and hypertension |

|

Hedermann, 6 Denmark |

Nationwide | Singleton | 12 March –14 April 2020 | 12 March– 14 April 2015–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; PTB <28 weeks | Logistic regression | |

|

Janevic, 26 USA |

Single center | Not reported | March 28–31 July 2020 | 28 March–31 July 2019 |

PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks |

Log binomial regression | |

|

Justman, 27 Israel |

Single center | Not reported | March–April 2020 | March–April 2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; Stillbirth; Birthweight | Chi‐square and t test or Mann–Whitney U test | |

|

Kasuga, 28 Japan |

Single center | Not reported | 1 April –30 June 2020 | 1 April –30 June 2017–2019 | PTB <37 weeks | Not reported | |

|

KC, 8 Nepal |

9 hospitals across seven provinces | Not reported | 21 March–30 May 2020 | 1 January–20 March 2020 |

PTB <37 weeks; Stillbirth; LBW; Neonatal mortality |

Generalized linear model with Poisson regression; Pearson’s χ2 | Ethnicity, maternal age, and complication during admission |

|

Khalil, 9 UK |

Single center | Singleton; twin; triplet | 1 February –14 June 2020 | 1 October 2019–31 January 2020 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; Stillbirth a | Mann–Whitney and Fisher exact | |

|

Kirchengast, 29 Austria |

Single center | Singleton | March to July 2020 | March to July 2005–2019 |

PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; LBW; VLBW; ELBW |

t test; Chi‐square test; Linear regression | |

|

Kumar, 30 India |

Not reported | Not reported | March to September 2020 | March to September 2019 |

Stillbirth; LBW; ELBW; VLBW |

Fisher exact test | |

|

Kumari, 31 India |

4 regional hospitals | Not reported | 25 March–2 June 2020 | 15 January–24 March 2020 | Stillbirth; Maternal mortality | Not reported | |

|

Lemon, 32 USA |

Single center | Singleton | 1 April– 27 October 2020 | 1 January 2018–31 January 2020 |

PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Spontaneous PTB; Medically indicated PTB |

Pearson Chi‐square or t tests | |

|

Li, 33 China |

Single center | Not reported | 23 January– 24 March 2020 | 1 January 2019–22 January 2020 | PTB <37 weeks; Birthweight | Chi‐square, t test and Fishers exact | |

|

Lumbreras‐Marquez, 34 Mexico |

Nationwide | Not reported | 1 January –9 August 2020 | 2011–2019 | Maternal mortality | Not reported | |

|

Main, 35 USA |

Statewide | Singleton | April–July 2020 | April–July 2016–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; PTB <28 weeks | Logistic regression | |

|

Matheson, 36 Australia |

3 regional hospitals | Singleton and multiple pregnancies | July–September 2019 | July–September 2020 |

PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Stillbirth; Spontaneous PTB; Medically indicated PTB |

Interrupted time‐series analysis; Auto‐regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model | |

|

McDonnell, 7 Ireland |

Single center | Not reported | January–July 2020 | January–July 2018–2019 |

PTB <37 weeks; Stillbirth |

Pearson correlation; Chi‐square, Fishers exact test |

|

|

Meyer, 37 Israel |

Single center | Singleton | 20 March –27 June 2020 | 20 March –27 June 2011–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; Stillbirth; Birthweight; Neonatal mortality | Multivariate regression | |

|

Meyer, 38 Israel |

Single center | Not reported | February–March 2020 | February–March 2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; Birthweight | Chi‐square; Fisher’s exact test; Mann–Whitney U test | |

|

Mor, 39 Israel |

Single center | Singleton |

21 February –30 April 2020 |

21 February–30 April 2017–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Stillbirth; Birthweight | Chi‐square test or Fisher’s exact test | |

|

Pasternak, 10 Sweden |

Nationwide | Singleton | 1 April –31 May 2020 | 1 April –31 May 2015–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Stillbirth | Logistic regression | Maternal age, birth country, parity, body mass index and smoking |

|

Philip, 2 Ireland |

Region‐wide | Not reported |

January–April 2020; and March–June 2020 |

January‐April 2001–2019; and March–June 2016–2019 |

Stillbirth; LBW; ELBW; VLBW |

Poisson regression | |

|

Shakespeare, 40 Zimbabwe |

Single center | Not reported | April–June 2020 | January–March 2020 | Stillbirth; neonatal mortality; maternal mortality | Not reported | |

| Simpson, 41 Canada | Region‐wide | Singleton; multiple | 15 March–30 September 2020 | 15 March–30 September 2015–2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Stillbirth | Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models | |

|

Stowe, 42 UK |

Nationwide | Not reported | April–June 2020 | April–June 2019 | Stillbirth | Fisher exact test | |

|

Sun 43 Brazil |

Single center | 11 March–11 June 2020 | 11 March–11 June 2019 | PTB <37 weeks; LBW | Not reported | ||

|

Wood 44 USA |

4 level 3 or 4 neonatal intensive care units |

Singleton | April–July 2020 | April–July 2019 | PTB <37 weeks; PTB <34 weeks; PTB <32 weeks; PTB <28 weeks; Spontaneous PTB | Not reported |

ELBW, extremely low birthweight, LBW, low birthweight, PTB, preterm birth, VLBW, very low birthweight.

Data not utilized due to overlapping cohorts.

TABLE 2.

Risk of bias assessment using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

| First author | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non‐exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow‐up long enough for outcomes to occur? | Adequacy of follow‐up of cohorts | ||

| Arnaez 15 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Been 45 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

| Berghella 16 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Caniglia 17 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | ||

| De Curtis 18 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Dell’Utri 19 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Du 20 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

| Goyal 21 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Greene 22 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Gu 23 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

| Handley 24 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 9 |

| Harvey 25 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

| Hedermann 6 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Janevic 26 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

| Justman 27 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Kasuga 28 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| KC 8 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | ||

| Khalil 9 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Kirchengast 29 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Kumar 30 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Kumari 31 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | |||

| Lemon 32 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Li 33 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Lumbreras‐Marquez 34 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Main 35 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Matheson 36 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

| McDonnell 7 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Meyer 1 37 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Meyer 2 38 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Mor 39 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

| Pasternak 10 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

| Philip 2 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

| Shakespeare 40 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

| Simpson 41 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

| Stowe 42 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

| Sun 43 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

| Wood 44 | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

A study can be awarded a maximum of 1 star for each item within the Selection and Outcome categories. A maximum of 2 stars can be given for comparability.

3.2. Synthesis: outcomes

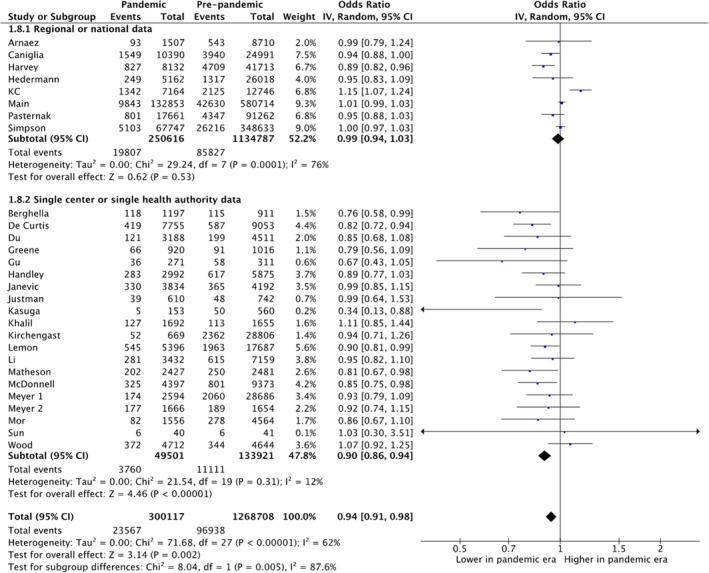

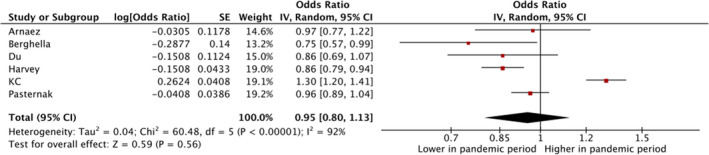

Preterm birth and its subgroups: Twenty‐eight studies including 300 117 women during the pandemic period and 1 268 708 women in the pre‐pandemic period reported PTB <37 weeks’ gestation; there was a reduction in unadjusted odds of PTB during the pandemic period compared with the pre‐pandemic period (pooled uaOR 0.94, 95% CI 0.91–0.98, I 2 = 62%; Figure 2). However, subgroup analyses revealed no differences in odds of PTB during pandemic period in national or regional studies (uaOR 0.99, 95% CI 0.94–1.03, I 2 = 76%). There was a reduction in odds of PTB in single‐center studies (uaOR 0.90, 95% CI 0.86–0.94, I 2 = 12%, subgroup differences p = 0.005; Figure 2). Six of these studies reported adjusted estimates (with different factors adjusted, reported in Table 1) but pooled analyses did not show significant differences in PTB rate (pooled aOR 0.95, 95% CI 0.80–1.13; I 2 = 92%; Figure 3). There was no reduction in unadjusted odds of PTB <34 weeks’ (Table 3, Appendix S3), <32 weeks’ (Table 3, Appendix S4), and <28 weeks’ gestation (Table 3, Appendix S5). Meta‐analysis of five studies reporting data on spontaneous PTB (Table 3, Appendix S6), and four studies of medically indicated PTB revealed reduction in unadjusted odds of PTB during pandemic period (Table 3, Appendix S7).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot for odds of preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation in pandemic vs pre‐pandemic periods. CI, confidence interval, IV, inverse variance

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot for adjusted odds of preterm birth <37 weeks’ gestation in pandemic vs pre‐pandemic periods. CI, confidence interval, IV, inverse variance

Most of the studies presented data for the entire pregnant population, but some categorically excluded individuals with a known confirmed diagnosis of COVID‐19. When the latter studies were included in meta‐analyses, we could identify no difference in PTB or stillbirth. For PTB, regional/national data from two studies had a pooled uaOR of 1.05 (95% CI 0.87–1.26) and six single‐center studies had a pooled uaOR of 0.89 (95% CI 0.79–1.01. For stillbirths, regional/national data from two studies had a pooled uaOR of 1.14 (95% CI 0.58–2.22 and four single‐center studies had a uaOR of 1.97 (95% CI 0.85–4.55).

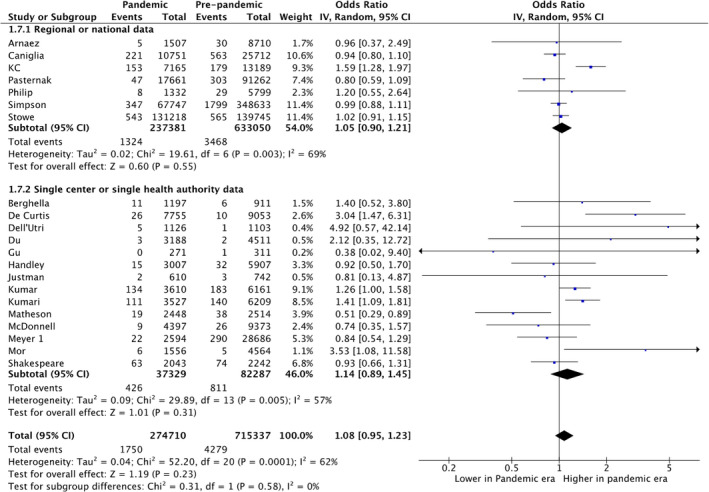

Stillbirth: Twenty‐one studies of 237 381 women during the pandemic period and 633 050 women in the pre‐pandemic period assessed stillbirth. There was no difference in the odds of stillbirth between the pandemic and pre‐pandemic periods (pooled uaOR 1.08, 95% CI 0.95–1.23, I 2 = 62%; Figure 4). Subgroup analyses also revealed no difference in stillbirth during the pandemic period vs the pre‐pandemic period in single‐center studies and regional/national studies (Figure 4). Meta‐analysis of adjusted estimates from four studies revealed no difference in stillbirth between groups (aOR 1.06, 95% CI 0.81–1.38; I 2 =72%; Appendix S8).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot for odds of stillbirth in pandemic vs pre‐pandemic periods. CI, confidence interval, IV, inverse variance

Birthweight: Seven studies of 13 871 women during the pandemic period and 49 152 women in the pre‐pandemic period reported birthweight. There was an increase in mean birthweight during the pandemic compared with the pre‐pandemic period (pooled mean difference 17 g, 95% CI 7–28 g, I 2 =0%; Table 3, Appendix S9). There was no difference in odds of low birthweight (Table 3, Appendix S10), very low birthweight (Table 3, Appendix S11) or extremely low birthweight (Table 3, Appendix S12).

Neonatal mortality: Six studies of 90 976 neonates during the pandemic period did not show any difference in the rate of neonatal mortality between the pandemic and pre‐pandemic periods (uaOR 1.34, 95% CI 0.71–2.55, I2 =96%; Table 3, Appendix S13); however, the heterogeneity of results across studies was very high. One national study from nine hospitals in Nepal8 reported a higher neonatal mortality rate during the pandemic period that may reflect significant local impact on access to care during the lockdown period.

Maternal mortality: Four studies reported on maternal mortality. Three studies reported no significant difference in maternal mortality; however, one study from Mexico34 reported a significant increase in maternal mortality during pandemic (Figure 5). The study from Mexico contributed to 98.7% of the weight in this analysis and it also reported that significant portion of excess mortality was due to respiratory infections including COVID‐19.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot for odds of maternal mortality in pandemic vs pre‐pandemic periods. CI, confidence interval, IV, inverse variance

In meta‐regression analyses, duration of the pre‐pandemic period did not emerge as a significant covariate for any outcome (p > 0.05 for all outcomes). We found evidence of publication bias for PTB (Egger’s p = 0.001; Appendix S14) but not for stillbirth (Appendix S15), with fewer studies reporting higher rates of PTB during the pandemic period.

TABLE 3.

Results of studies reporting other outcomes

| Outcome | No. of studies | Pandemic period (n/N) | Pre‐pandemic period (n/N) | OR (95% CI) | I 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTB <34 weeks | 8 | 523/21 240 | 1592/62 282 | 0.87 (0.70–1.07) | 67 |

| PTB <32 weeks | 13 | 3668/263 626 |

14 366/ 1 198 164 |

0.96 (0.78–1.19) | 94 |

| PTB <28 weeks | 10 | 1136/240 218 | 5404/1 085 624 | 0.92 (0.79–1.06) | 51 |

| Spontaneous PTB | 5 | 767/16 724 | 1685/31 598 | 0.89 (0.82–0.98) | 0 |

| Induced PTB | 4 | 583/12 012 | 1453/26 954 | 0.90 (0.81–1.00) | 0 |

| Low birthweight | 7 | 1673/24 121 | 7194/99 667 | 0.90 (0.80–1.02) | 53 |

| Very low birthweight | 5 | 205/15 292 | 1366/114 636 | 1.03 (0.71–1.49) | 65 |

| Extremely low birthweight | 4 | 33/7167 | 299/73 001 | 0.83 (0.32–2.17) | 72 |

| Neonatal mortality | 6 | 583/90 976 | 1263/419 057 | 1.34 (0.71–2.55) | 96 |

| Birthweight, g | 6 | 13 871 a | 49 152 a | 17.0 (6.9–27.6) b | 0 |

PTB, preterm birth.

Birthweight is shown as total number.

Value shown is mean difference (95% CI) in grams.

4. DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta‐analysis, we identified a reduction in the unadjusted odds of PTB in pandemic compared with pre‐pandemic time periods, especially spontaneous PTB and medically indicated PTB. However, in subgroup analyses, a significant reduction in PTB was only observed in single‐center studies, not in regional or national studies. Moreover, we identified no difference in the odds of PTB in analysis of studies that reported adjusted estimates, although there was variation in the factors adjusted for across the individual studies. We identified no difference in any other fetal/neonatal outcomes including stillbirths and neonatal mortality, and only a marginal increase of 17 g in mean birthweight during the pandemic period as compared with the pre‐pandemic period. The increased incidence of maternal mortality noted in our meta‐analysis, was mostly driven by one study from Mexico 34 which included deaths due to COVID‐19, which emerged as the leading cause of maternal mortality during the pandemic period.

This review was designed to evaluate the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic time period on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes and not to evaluate studies that report only on maternal COVID‐19 infection itself, which has been discussed in other reviews. 46 , 47 , 48 We specifically excluded studies which only reported outcomes of pregnant population infected with COVID‐19. We identified conflicting evidence from the included studies based on whether they were single‐center or regional/national studies. There could be a number of reasons for this. In addition to potential referral bias, other potential explanations include variation in sample sizes, outcome definitions, lengths of the pandemic and pre‐pandemic periods, differences in timing and enforcement of lockdown orders, failure of some studies to account for natural variation in pregnancy outcomes over time, and dissimilarities among COVID‐19 mitigation strategies. 8 , 10 , 17 , 24 , 38 Moreover, the study populations were heterogeneous; for example, baseline PTB rates ranged from 4.8% to 16.7% during pre‐pandemic period across the included studies; however, the change in PTB rate between periods was not baseline‐rate dependent. Although we did not observe any differences in subgroups of PTB using different gestational age cut‐offs (ie <34, <32 and <28 weeks), not all studies contributed to these analyses.

Recently, Chmielewska et al. 49 reported results from a systematic review and meta‐analyses including studies evaluating studies assessing population‐level impact during pandemic period published up to 8 January 2021. They reported no difference in PTB rate (15 studies, uaOR 0.94, 95% CI 0.87–1.02) but an increase in stillbirth (12 studies, uaOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.07–1.54) and maternal mortality. With availability of data from 13 more studies on PTB and nine more studies for stillbirth, the results have remarkably changed, although this could also partly relate to minor differences in study inclusion criteria and data extraction. The larger number of subjects included in pooled analyses in our review has improved the precision of pooled estimates, thus increasing confidence in the findings, particularly for less common secondary outcomes; nonetheless, this is the main reason for conducting this as a living systematic review so the information can be updated regularly.

The effects of lockdowns and mitigation strategies had contrasting effects in high‐ vs low‐ and middle‐income countries. 49 Reports from low‐resource settings described increased fear and stress among pregnant individuals, reluctance to access in‐hospital care during a pandemic, financial or employment issues, childcare or home schooling challenges, maternity staff shortages, reduced access to in‐hospital care, and perceived or actual reductions in available obstetric services, resulting in a significant reduction in institutional births. 8 , 9 , 17 , 30 Some reports noted a reduction in PTB and attributed this to a number of social and health behaviors associated with the pandemic, 2 , 7 including decreased physical and mental stress due to better work–life balance, 6 , 16 , 37 better support systems and financial assistance, 16 , 28 improved nutrition, better hygiene, 8 , 12 reduced physical activity, 6 , 16 , 28 , 33 reduced exposure to infection, 8 , 16 , 37 , 50 lower incidence of smoking and drug use due to reduced access and being indoors, 16 lower pollution exposure and levels in environment, 16 , 51 and fewer medical interventions secondary to reduced antenatal surveillance. 7 , 16 , 37 , 45 The differences in PTB findings between single‐center/adjacent hospitals studies and national/regional studies could reflect a change in referral patterns due to reduced access or the fact that pregnant individuals opted to give birth in hospitals with lower prevalence of COVID‐19 or in non‐COVID‐designated hospitals. 27 Future studies are needed to explore these differences.

Although we did not observe an overall change in the odds of stillbirth during the pandemic period, several individual studies, mostly single‐center in scope, reported increased odds of stillbirth compared to pre‐pandemic time periods. The increase in stillbirth reported by these studies was attributed to reduced antenatal surveillance, a reluctance to access in‐hospital care due to increased stress and anxiety 9 , 18 , 30 , 33 , 39 or missed appointments due to rapid changes in maternity services during the pandemic. 50 These reasons may also explain an increase in maternal mortality identified in Mexico 34 ; however, according to those authors, the data from a government website were preliminary in scope and may change as more data become available. This could be a signal to be vigilant in attending the mother–fetus dyad during difficult public health emergency situations.

We did not find any significant differences between the pandemic and pre‐pandemic periods for other outcomes, except for a marginal difference in birthweight. Since these data came from only five studies, further studies are needed to clarify this association, as a difference of 17 g is unlikely to be of clinical significance. Other factors that could be responsible for the differences between study findings include variations in the etiology of adverse pregnancy outcomes in different countries, 2 , 17 initiatives by local governments to provide support to those at risk for higher stress, 7 and changes to national legislation on pregnancy termination during the study period potentially influencing the incidences of stillbirth and PTB. 2 , 7

A key strength of our review was the inclusion of large populations from 18 countries, mainly arising from national or state or provincial data. Most included studies came from registries or similar types of datasets. In addition, we only included studies that reported on temporal changes in outcomes in the overall population, not data specifically from women affected by COVID‐19. However, our study has limitations. There may be other relevant studies that are not yet published (and thus are not included), as the pandemic is still ongoing and many countries are facing a second or third wave of infections and associated public health restrictions. There was clinical and methodologic heterogeneity across studies regarding pandemic and pre‐pandemic period definitions, population bases (single‐center/adjacent hospitals vs regional/national) and choices of statistical methodologies. To overcome these limitations, we planned a priori to include pre‐pandemic duration in meta‐regression analyses, and we conducted post‐hoc subgroup analyses on the type of studies. We were able to explain statistical heterogeneity to an extent for both of our primary outcomes. Some studies included the entire population of pregnant women, comprising those who did and did not have COVID‐19 infection in their sample. When studies that categorically excluded women with COVID‐19 infection were included in our review, we identified no difference in PTB or stillbirth. Finally, there were an insufficient number of studies to assess some of the prespecified outcomes, including maternal mortality.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has affected many countries with very high case numbers, such as India, Brazil, the UK and Italy, yet large, population‐based estimates on pregnancy outcomes from these countries were lacking in this review. National registries from these and other countries would be ideally suited to investigate the impact of the pandemic on perinatal health at a population level. A harmonization of methodological approaches would also facilitate the assessment of the effects of the pandemic period on fetal, neonatal and maternal outcomes, as high methodological heterogeneity makes direct comparisons challenging. One important point to consider going forward will be that the rates of these outcomes fluctuate with natural variation over time. We hope to capture these fluctuations through 3‐monthly updates of this living systematic review. Future investigations should use approaches than can elucidate whether any fluctuation observed in a particular setting during the pandemic period is outside the range of expected natural variation.

5. CONCLUSION

In pooled analyses, we observed reductions in the unadjusted odds of PTB between the pandemic and pre‐pandemic periods; especially spontaneous PTB. However, this finding was driven by single‐center studies. There was no difference in analyses of adjusted estimates of PTB or within subgroups of PTB. Although we did not observe meaningful differences in other outcomes, including odds of stillbirth, the data were more limited and precluded a robust assessment. Higher maternal mortality reported from Mexico indicates that further studies from low‐ and middle‐income regions highly affected by COVID‐19 are needed where drastic changes in the healthcare access, healthcare availability, and personal, social and environmental factors contributed disproportionately to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Since the findings are changed between reviews published recently and current reviews, there is a need for a living systematic review which can be updated regularly.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

PSS conceptualized and designed the study and conducted and executed the search strategy. PSS and JY screened study titles, abstracts, and full texts; completed the analysis and risk of bias assessments; and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AK, DBF, JWS, KEM, and RD contributed to the data interpretation, commented on all versions of the manuscript, and approved the final draft. All authors have approved this version of the manuscript as submitted, and all agree to be accountable for its accuracy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Appendix S1‐S15

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Heather McDonald Kinkaid, PhD, for editorial support in preparing this manuscript. Dr. Kinkaid is a scientific writer employed with the Maternal‐infant Care Research Centre (MiCare) at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and receives a salary for her work. MiCare is supported by Sinai Health and the participating hospitals, and in turn provides organizational support for the Canadian Preterm Birth Network.

Yang J, D’Souza R, Kharrat A, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and population‐level pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: a living systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1756–1770. 10.1111/aogs.14206

Funding information

Although no specific funding was received for this study, the Canadian Preterm Birth Network is funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (PBN 150642)

REFERENCES

- 1. Ohlsson A, Shah PS. Effects of the September 11, 2001 disaster on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:6‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Philip RK, Purtill H, Reidy E, et al. Unprecedented reduction in births of very low birthweight (VLBW) and extremely low birthweight (ELBW) infants during the COVID‐19 lockdown in Ireland: a ‘natural experiment’ allowing analysis of data from the prior two decades. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e003075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stout MJ, Busam R, Macones GA, Tuuli MG. Spontaneous and indicated preterm birth subtypes: interobserver agreement and accuracy of classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:530.e1‐530.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu LI, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–13, with projections to inform post‐2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430‐440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crump C. An overview of adult health outcomes after preterm birth. Early Hum Dev. 2020;150:105187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hedermann G, Hedley PL, Bækvad‐Hansen M, et al. Danish premature birth rates during the COVID‐19 lockdown. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021;106:93‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McDonnell S, McNamee E, Lindow SW, O’Connell MP. The impact of the Covid‐19 pandemic on maternity services: A review of maternal and neonatal outcomes before, during and after the pandemic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:172‐176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kc A, Gurung R, Kinney MV, et al. Effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1273‐e1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khalil A, von Dadelszen P , Draycott T, Ugwumadu A, O’Brien P, Magee L. Change in the incidence of stillbirth and preterm delivery during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324:705‐706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pasternak B, Neovius M, Söderling J, et al. Preterm birth and stillbirth during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Sweden: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2021. DOI: 10.7326/M20-6367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang J, Shah P. COVID‐19 pandemic and population level pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021234036 (accessed 18 May 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Statistics Canada . Deaths 2004: Vital Statistics‐Stillbirth Database. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/84f0211x/2004000/4068009‐eng.htm (accessed 18 April 2021).

- 14. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta‐analyses (vol 2021). http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed 18 May 2021).

- 15. Arnaez J, Ochoa‐Sangrador C, Caserío S, et al. Lack of changes in preterm delivery and stillbirths during COVID‐19 lockdown in a European region. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:1997‐2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berghella V, Boelig R, Roman A, Burd J, Anderson K. Decreased incidence of preterm birth during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Caniglia EC, Magosi LE, Zash R, et al. Modest reduction in adverse birth outcomes following the COVID‐19 lockdown. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:615.e615.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Curtis M, Villani L, Polo A. Increase of stillbirth and decrease of late preterm infants during the COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dell’Utri C, Manzoni E, Cipriani S, et al. Effects of SARS Cov‐2 epidemic on the obstetrical and gynecological emergency service accesses. What happened and what shall we expect now? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;254:64‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Du M, Yang J, Han N, Liu M, Liu J. Association between the COVID‐19 pandemic and the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e047900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goyal M, Singh P, Singh K, Shekhar S, Agrawal N, Misra S. The effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on maternal health due to delay in seeking health care: Experience from a tertiary center. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;152:231‐235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greene NH, Kilpatrick SJ, Wong MS, Ozimek JA, Naqvi M. Impact of labor and delivery unit policy modifications on maternal and neonatal outcomes during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gu XX, Chen K, Yu H, Liang GY, Chen H, Shen Y. How to prevent in‐hospital COVID‐19 infection and reassure women about the safety of pregnancy: Experience from an obstetric center in China. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520939337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Handley SC, Mullin AM, Elovitz MA, et al. Changes in preterm birth phenotypes and stillbirth at 2 Philadelphia hospitals during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic, March–June. JAMA. 2020;2020:87‐89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harvey EM, McNeer E, McDonald MF, et al. Association of preterm birth rate with COVID‐19 statewide stay‐at‐home orders in Tennessee. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;e206512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Janevic T, Glazer KB, Vieira L, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in very preterm birth and preterm birth before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e211816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Justman N, Shahak G, Gutzeit O, et al. Lockdown with a price: The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on prenatal care and perinatal outcomes in a tertiary care center. Isr Med Assoc J. 2020;22:533‐537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kasuga Y, Tanaka M, Ochiai D. Preterm delivery and hypertensive disorder of pregnancy were reduced during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a single hospital‐based study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020. DOI: 10.1111/jog.14518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kirchengast S, Hartmann B. Pregnancy outcome during the first COVID 19 lockdown in Vienna, Austria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18073782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kumar M, Puri M, Yadav R, et al. Stillbirths and the COVID‐19 pandemic: looking beyond SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153:76‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumari V, Mehta K, Choudhary R. COVID‐19 outbreak and decreased hospitalisation of pregnant women in labour. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1116‐e1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lemon L, Edwards RP, Simhan HN. What is driving the decreased incidence of preterm birth during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic? Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021;3:100330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li M, Yin H, Jin Z, et al. Impact of Wuhan lockdown on the indications of cesarean delivery and newborn weights during the epidemic period of COVID‐19. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lumbreras‐Marquez MI, Campos‐Zamora M, Seifert SM, et al. Excess maternal deaths associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Mexico. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:1114‐1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Main EK, Chang S‐C, Carpenter AM, et al. Singleton preterm birth rates for racial and ethnic groups during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:239‐241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matheson A, McGannon CJ, Malhotra A, et al. Prematurity rates during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic lockdown in Melbourne, Australia. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:405‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meyer R, Bart Y, Tsur A, et al. A marked decrease in preterm deliveries during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:234‐237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meyer R, Levin G, Hendin N, Katorza E. Impact of the COVID‐19 outbreak on routine obstetrical management. Isr Med Assoc J. 2020;22:483‐488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mor M, Kugler N, Jauniaux E, et al. Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on excess perinatal mortality and morbidity in Israel. Am J Perinatol. 2020;38:398‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clare Shakespeare DH, Moyo S, Ngwenya S. Resilience and vulnerability of maternity services in Zimbabwe: A comparative analysis of the effect of Covid‐19 and lockdown control measures on maternal and perinatal outcomes at Mpilo Central Hospital. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs‐52159/v1 (accessed 18 May 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41. Simpson AN, Snelgrove JW, Sutradhar R, Everett K, Liu N, Baxter NN. Perinatal outcomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2110104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stowe J, Smith H, Thurland K, Ramsay ME, Andrews N, Ladhani SN. Stillbirths during the COVID‐19 pandemic in England, April–June 2020. JAMA. 2021;325:86‐87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sun SY, Guazzelli CAF, Morais LR, et al. Effect of delayed obstetric labor care during the COVID‐19 pandemic on perinatal outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151:287‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wood R, Sinnott C, Goldfarb I, Clapp M, McElrath T, Little S. Preterm birth during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic in a large hospital system in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:403‐404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Been JV, Burgos Ochoa L, Bertens LCM, Schoenmakers S, Steegers EAP, Reiss IKM. Impact of COVID‐19 mitigation measures on the incidence of preterm birth: a national quasi‐experimental study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e604‐e611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Juan J, Gil MM, Rong Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Poon LC. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:15‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Smith V, Seo D, Warty R, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with COVID‐19 infection: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0234187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, et al. Effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Coxon K, Turienzo CF, Kweekel L, et al. The impact of the coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic on maternity care in Europe. Midwifery. 2020;88:102779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bauwens M, Compernolle S, Stavrakou T, et al. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on NO(2) pollution assessed using TROPOMI and OMI observations. Geophys Res Lett. 2020;47;e2020GL087978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1‐S15