Summary

Between October 2020 and January 2021, we conducted three national surveys to track anaesthetic, surgical and critical care activity during the second COVID‐19 pandemic wave in the UK. We surveyed all NHS hospitals where surgery is undertaken. Response rates, by round, were 64%, 56% and 51%. Despite important regional variations, the surveys showed increasing systemic pressure on anaesthetic and peri‐operative services due to the need to support critical care pandemic demands. During Rounds 1 and 2, approximately one in eight anaesthetic staff were not available for anaesthetic work. Approximately one in five operating theatres were closed and activity fell in those that were open. Some mitigation was achieved by relocation of surgical activity to other locations. Approximately one‐quarter of all surgical activity was lost, with paediatric and non‐cancer surgery most impacted. During January 2021, the system was largely overwhelmed. Almost one‐third of anaesthesia staff were unavailable, 42% of operating theatres were closed, national surgical activity reduced to less than half, including reduced cancer and emergency surgery. Redeployed anaesthesia staff increased the critical care workforce by 125%. Three‐quarters of critical care units were so expanded that planned surgery could not be safely resumed. At all times, the greatest resource limitation was staff. Due to lower response rates from the most pressed regions and hospitals, these results may underestimate the true impact. These findings have important implications for understanding what has happened during the COVID‐19 pandemic, planning recovery and building a system that will better respond to future waves or new epidemics.

Keywords: anaesthesia, COVID‐19, critical care, peri‐operative medicine

Introduction

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, there has been considerable focus on the escalation of critical care capacity, capability and delivery. In many UK hospitals, critical care and anaesthesia departments work together and share staff. The expansion of critical care capability has inevitably led to redeployment of staff, space, equipment and drugs intended for anaesthesia and peri‐operative care [1, 2]. In the first wave of the pandemic, most planned surgery was stopped for several months but, after this, there were specific efforts made to restore surgical activity and to maintain this, even in the face of subsequent waves of pandemic activity [3, 4]. The extent of disruption of anaesthetic and peri‐operative activity in the second wave has not been clearly documented. The 7th National Audit Project (NAP7) is a national service evaluation, run by the Health Service Research Centre within the Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA), examining peri‐operative cardiac arrest which had been due to start in May 2020. Early in the first wave, NAP7 was postponed and, as part of assessing when anaesthetic and peri‐operative services might have returned to a stable baseline and thus be ready for starting NAP7, we undertook a series of national surveys in order to track activity during the second wave of the pandemic.

Methods

The Anaesthesia and Critical Care COVID‐19 Activity Tracking (ACCC‐track) survey did not meet the definition of research as per the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research [5], was deemed a service evaluation and therefore did not require research ethics committee approval. The conduct of ACCC‐track was approved by the RCoA Clinical Quality and Research Board. During the planning stages of NAP7, a network of 330 local co‐ordinators was established in all NHS hospitals and many independent sector hospitals in the UK. After the postponement of NAP7, as part of planning for restarting, we initially devised the ACCC‐track survey to determine the degree of disruption of peri‐operative services and readiness to start NAP7. A questionnaire was submitted to all local co‐ordinators in July 2020 which showed a majority (75%) supported the concept of the ACCC‐track survey. An electronic survey tool (SurveyMonkey®) was used to conduct three successive ACCC‐track surveys. The survey tracked changes of systemic stress in surgical and critical care during different stages of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Rounds 2 and 3 differed from Round 1 (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1) by removal of questions that did not need repetition and addition of new questions as indicated. Drafts of the survey were reviewed and tested by clinicians involved with NAP7 and the RCoA Quality Improvement committee.

Rounds 1 and 2 of the survey were sent to all local co‐ordinators. Responses were encouraged by email reminders at regular intervals to local co‐ordinators and to anaesthetic department clinical leads once per round. Respondents were asked to provide information for the main hospital site they represented, which was identified by region and name of hospital. Response rates from the independent sector were limited and for Round 3 only the 273 local co‐ordinators representing the 420 NHS hospitals were asked to respond [6]. This analysis only includes data from NHS hospitals.

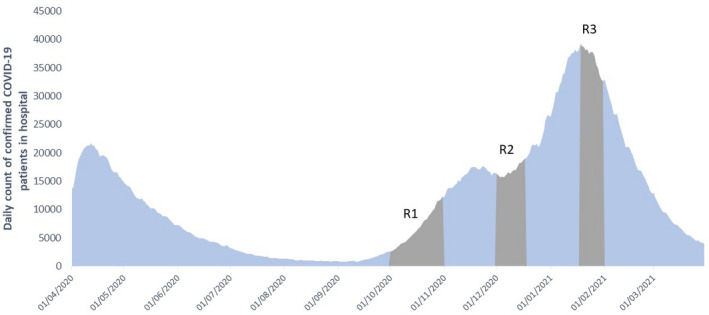

Duplicate responses and those which did not record a hospital site and/or region were excluded. Since some local co‐ordinators represented more than one hospital across multiple sites, the hospital response rate was calculated using the 420 NHS hospitals with anaesthesia provision as the denominator. This denominator was cross‐referenced using NHS digital [7] and NAP7 lists of hospital sites [6]. Data collection periods were as follows: Round 1 (R1) for the month of October 2020; Round 2 (R2) for 2 weeks between 1 and 18 December 2020; Round 3 (R3) for 2 weeks between 18 and 31 January 2021. Surveys could be submitted for 4–5 weeks after distribution. These three rounds corresponded to different stages of the second wave, as recorded on the UK government’s COVID‐19 data website [8]: Round 1 from the start of the second wave and before the second lockdown in England; Round 2 shortly after the end of this lockdown, during a period of slowly increasing hospital activity, and Round 3 during the third lockdown and shortly after the peak of the secondary surge caused by the SARS‐CoV‐2 Kent B117 variant [9]. The relationship between the timing of the surveys and UK hospital admissions due to COVID‐19 is shown in Figure 1. In each round, respondents were asked about anaesthesia/surgical activity, including the number of operating theatres open for activity at the hospital site and their productivity compared with the previous year, measures taken to increase operating theatre capacity at other locations (e.g. another NHS or independent sector hospital), reorganisation of care pathways and changes to staffing levels, including COVID‐19 related staff sickness and redeployment (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1).

Figure 1.

Timing of the surveys and number of hospital admissions due to COVID‐19 in the UK. Grey areas represent the timeline for October 2020 (R1), December 2020 (R2) and January 2021 (R3). Data adapted from [9].

Organisational disruption of anaesthetic and critical care departments were assessed using the red‐amber‐green rating criteria for ‘Space, Staff, Stuff (equipment) and Systems’ described in Restarting planned surgery in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic [10] which was a joint publication of the four UK organisations supporting the Intensive Care Medicine‐Anaesthesia‐COVID‐19 hub (ICM‐anaesthesia hub – https://icmanaesthesiacovid‐19.org). Each ‘red’ rating describes a system “not ready for a return”, ‘amber’ a system “close to being ready for a return” and ‘green’ a system “ready for a return” to undertaking planned surgery (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1) [10]. Overall organisational disruption of peri‐operative services can be measured by combining red and amber responses.

Round 1 examined the types of personal protective equipment and organisational processes used in operating theatres for patients designated as at low and high risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Rounds 2 and 3 assessed the degree of critical care expansion and disruption using the levels of the staged resurgence plan described in the ICM‐anaesthesia hub document Anaesthesia and critical care: guidance for Clinical Directors on preparations for a possible second surge in COVID‐19, which, in September 2020, advised departments across the UK how to respond to the second COVID‐19 wave by increasing critical care capacity while also protecting planned surgery [4]. Five stages of critical care capacity surge are described (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1): stage 1, an endemic level of COVID‐19 activity; stage 2, increased demand but met within established capacity; stages 3–5, normal capacity (or capability) is exceeded and in stage 5, there is a need to transfer via external local or regional networks as part of mutual aid. Round 3 collected the number of critically ill COVID‐19 patients transferred into and out of respondents’ hospitals as part of mutual aid.

Data from SurveyMonkey were exported into, cleaned and analysed using Microsoft Excel version 2021 (Microsoft, Inc., Redmond, WA, USA). Qualitative data were imported and analysed using NVivo version 2020 (QSR, International Pty Ltd., Burlington, MA, USA), identifying common themes. Incomplete responses to individual questions were accepted with missing data noted as a non‐response, except in questions that required comparative analysis (e.g. difference in the number of operating theatres open or differences in the number of cases performed compared with a previous time‐point), in which case the responses were excluded from analysis. When estimating changes in anaesthesia and ICU workforce and the number of lost operations per day, an adjustment was made for non‐responders and survey response to provide an estimate of national impact. Data from August 2020 NHS Workforce Statistics [11] were used as the denominator for the number of current anaesthesia (13,119) and critical care (2404) staff in England and this was scaled up to UK levels by multiplying by 1.187 [12].

Results

Responses were received from 176 (64%) NHS local co‐ordinators in R1, 154 (56%) in R2 and 140 (51%) in R3. These local co‐ordinators represented 65% of NHS hospitals in R1, 54% in R2 and 51% in R3. Response rate varied by region (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1). In R1, this ranged from 80% from the East and West Midlands to 46% from Wales, in R2 80% from Yorkshire and Humber region to 35% from Wales and in R3 from 68% from the South‐West to 32% from the East Midlands. Response rate fell most between R2 and R3, with half the regions having a <50% response rate in R3.

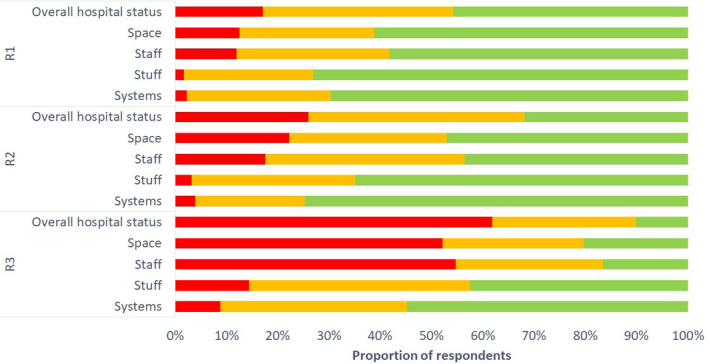

A summary of key results is presented here, with a more detailed analysis of theatre processes and personal protective equipment and detailed results by region presented in the Supporting Information Appendix S1. Staff and space were the resources most frequently affected (Fig. 2). Nationally, between R1 and R3, green ratings for staff reduced from 58.3% to 16.5% and for space from 61.1% to 20.3%. Stuff (equipment) and systems were less impacted; green ratings for both fell to approximately 50% in R3. In R1 and R2, 54% and 68% of departments, respectively, had at least one red or amber domain and therefore self‐declared as not ready for a return to planned surgery. In R3 this rose to 90%. In R3, no region reported being above 50% green for space or staff with most above 80% amber/red, of which most were red.

Figure 2.

Proportion of respondents (%) that have reported red (not able to resume planned surgery), amber (nearly able to resume planned surgery) or green (able to resume planned surgery) for ‘Space, Staff, Stuff (equipment) and Systems’ categories for R1 (October 2020), R2 (December 2020), R3 (January 2021). ‘Overall hospital status’ indicates the proportion of respondents reporting at least one of staff, space, stuff or systems red (red), no red and at least one amber (amber), all green (green).

In R2, 45% reported ICU expansion beyond baseline capacity (staged resurgence plan 3–5) and in 15% there was an imminent or actual need for mutual aid to transfer critically ill COVID‐19 patients to other hospitals (staged resurgence plan 4–5) (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1). In R3, 74% of ICUs were expanded above capacity, with 39% likely or actually needing mutual aid. In R3, 133 respondents (accounting for approximately 40% of all UK hospitals, but a greater proportion of all critical care units) reported admission of approximately 900 patients transferred under mutual aid and transfer out of 600 to another hospital under mutual aid.

In R2, by nation, ICU expansion above normal capacity was highest in England (49%) and lowest in Scotland (17%). The South‐West was the least impacted region in England with 33% of ICUs needing to expand, compared with 60% in North‐East England and the East Midlands. Potential or actual use of mutual aid transfers ranged from 0% in North‐West and South‐West England to 36% of hospitals in the East of England. In R3, 75% of hospitals in England, Northern Ireland and Wales expanded their ICUs and 67% of hospitals in Scotland. Within English regions, expansion rates ranged from 45% (Yorkshire and Humber) to 100% (North‐East). The potential or actual need for mutual aid transfers ranged from 0% in North‐East England to 78% in the West Midlands.

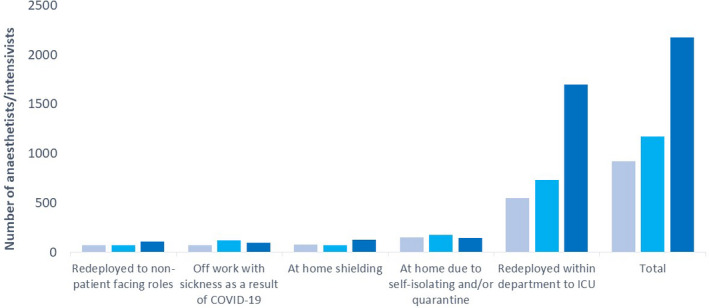

Figure 3 shows the impact of COVID‐19 on absences within the anaesthetic workforce. A progressive loss of the anaesthesia workforce was seen through the survey rounds, largely due to redeployment to critical care, resulting in a simultaneous increase in the critical care workforce. Loss of anaesthetic staff due to redeployment to non‐patient‐facing roles, shielding, self‐isolation, quarantine and sickness as a result of COVID‐19 did not change substantially between R1 and R3. The overall impact on national anaesthesia staffing was: 12% loss in October 2020, 15% loss in December 2020 and 29% loss in January 2021. The redeployment to critical care increased the critical care workforce by approximately 38% in October 2020, rising to an approximately 125% increase in January 2021.

Figure 3.

Impact on anaesthesia and critical care staffing levels. Total number of anaesthetists and/or intensivists off work or redeployed to ICU activities as a result of COVID‐19 in R1 (October 2020, light blue), R2 (December 2020, mid blue) and R3 (January 2021, dark blue) from responding hospital sites.

A progressive decrease in anaesthesia and surgical activity was reported across the UK, with the highest impact in R3. Among all respondents, the average proportion of operating theatres closed increased from 15% in R1 to 42% in R3 (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1). Regionally, the steepest rises in operating theatre closures were in London, and the East and South‐East of England, which all had among the lowest rates of closure until R3. In R3, five regions (42%) had more than 50% of their normal operating theatre capacity closed, eight (67%) more than 40%, and 10 (83%) more than 30%.

The overall use of external sites to maintain surgical activity decreased from R1 (10%) to R3 (8%) (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1). While some regions were able to maintain external surgical capacity between R1 and R3 (London and South‐East England both maintained > 10%), this reduced in many (e.g. North‐West England 10% to 8% and Yorkshire and the Humber 12% to 7%) and increased in only one (East of England 14% to 15%). In R1, in five regions (East of England, London, South‐East, South‐West and North‐East) external operating theatre expansion exceeded theatre closures. This reduced to two regions (East of England and London) in R2 and in R3 operating theatre closures exceeded external expansion in all regions.

In those operating theatres that were open, theatre activity declined in all rounds compared with the corresponding previous year (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1). Between R1 and R3, near‐normal productivity (75–100%) fell from 48% to 32% and operating at < 50% productivity increased from 10% to 27%.

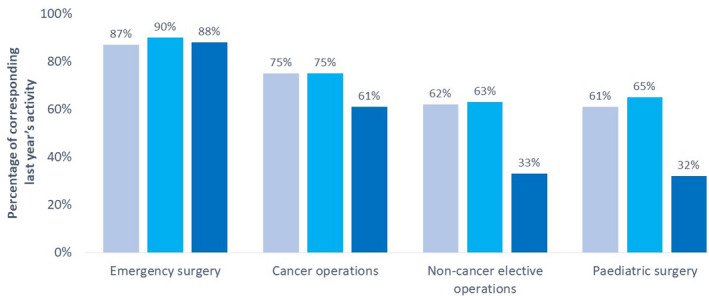

Surgical activity, compared with 12 months previously, reduced in all rounds of the survey, but most markedly in R3 (Fig. 4). At all times, the greatest impacts were (in descending order): paediatric; non‐cancer elective; cancer; and emergency surgery. In R3, paediatric and non‐cancer elective surgery activity were at less than a third of the previous year’s activity and cancer surgery was reduced by more than a third. Regional variation in impact was noted, particularly among paediatric and non‐cancer surgical activity (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1).

Figure 4.

Average UK percentage of surgical activity at R1 (October 2020, light blue), R2 (December 2020, mid blue) and R3 (January 2021, dark blue) compared with the corresponding previous year’s activity.

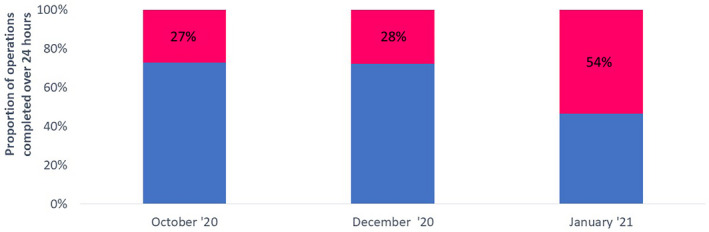

Measured over a 24 h period, in R1 and R2 overall surgical activity was reduced by a little over one‐quarter compared with 12 months previously (Fig. 5). This equates to approximately 5000 operations not performed each day in the NHS. In R3, surgical activity was reduced by 54% compared with 12 months previously; equivalent to 9770 operations lost per day across the UK.

Figure 5.

Proportion of operations (%) completed over a 24‐hour period from responding hospital sites compared with the previous year, at R1 (October 2020), R2 (December 2020) and R3 (January 2021). Blue area denotes the proportion (%) of active surgical cases completed and pink area the proportion (%) of lost surgical cases that were completed on the same date the previous year.

Qualitative open responses for factors facilitating the delivery of peri‐operative care included staff flexibility (e.g. new rotas, extra shift work), use of virtual communication and presence of separate low‐risk COVID‐19 areas. Barriers included staffing issues, critical care bed and operating theatre availability. Although themes were similar during R1 and R3 (see also Supporting Information Appendix S1) in R1, issues surrounding personal protective equipment supply and testing facilities were reported, whereas cessation of elective work only featured in R3, in which there was also an increase in number of respondents reporting lack of staff and space compared with R1.

Discussion

The three rounds of this service evaluation have provided a clear picture of increasing systemic stress and disruption of anaesthetic and peri‐operative services throughout the UK, as a consequence of the second wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic and the need to support increased critical care demand. During Rounds 1 and 2, anaesthetic staff and peri‐operative services were significantly impacted by the pandemic. Staff and space constraints had the greatest impact. Surgical activity was reduced by both significant closure of operating theatres and reduced activity within those that were open. Some mitigation of this was achieved by relocation of surgical activity to external sites, but in most locations this did not fully match the reduction in surgical activity and, overall, more than a quarter of all surgical activity was lost. Paediatric and non‐cancer surgery were most impacted, with less impact on cancer surgery and emergencies. Round 1 of the survey was undertaken when UK COVID‐19 hospital activity was increasing and shortly before much of the UK entered lockdown in November 2020. Round 2 took place after that lockdown was lifted and as UK COVID‐19 hospital activity continued to slowly increase. Overall measures of system stress increased by a small amount between October and December 2020, including redeployment of staff from anaesthesia to critical care, and by December approximately half of critical care units were expanded, to the extent that planned surgery could not be safely undertaken.

Round 3 took place shortly after the peak of the second surge and showed that the system was close to breaking point. The number of open operating theatres fell further, as did efficiency in those that were open. Hospitals were less able to relocate activity to other locations, although whether this was due to staff shortage or other factors, such as contractual arrangements, is not clear. Almost one in three anaesthetic staff were unavailable for anaesthetic activity as redeployments more than doubled the critical care workforce. All but a quarter of critical care units were expanded to the extent that planned surgery could not be safely undertaken. As a result, surgical activity fell precipitously, with all types of surgery affected. In hard‐pressed regions, paediatric and non‐cancer surgery fell to 12–20% of normal activity and even cancer surgery fell to below half of normal activity.

In Rounds 1 and 2, reduced peri‐operative capability led to a decrease in surgical activity of a little over one‐quarter compared with previous years. In Round 3, surgical activity decreased to below half of normal. With estimates of NHS surgical activity, in which anaesthetists are involved, being approximately 4 million episodes per year [13] these figures represent an annual loss of surgical activity of approximately 1–2 million cases per year. In the spring of 2020, almost all planned surgical activities ceased and, despite explicit efforts to resume and maintain this from July 2020 onwards, it is clear that this has been hampered. Other sources make similar estimates of surgical workload lost, with numbers of patients added to waiting lists being estimated as approximately 1.5–2 million (Dobbs T, et al., preprint, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.27.21252593v1) and 2 million [14]. When this accumulated surgical activity is added to pre‐existing waiting lists, cumulative waiting lists now are estimated to be between 4.5 million (Dobbs T et al., preprint, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.27.21252593v1) and 7.5 million [14].

Optimistically, control of COVID‐19 in the UK will be achieved by a combination of prolonged lockdown and extensive vaccination [15]. Resumption of surgical activity and peri‐operative services will need to go hand in hand with decompression and step‐down of expanded critical care provision [1, 10]. Our data illustrate very clearly that anaesthetists (and in all probability other healthcare providers working in operating theatres) have been central in the critical care response to the pandemic, and that they will have been similarly impacted. It is acknowledged that as a consequence of increased amount and intensity of workload, decreased leave, psychological burden and moral injury, the physical and psychological needs of the workforce must be considered in planning recovery of non‐COVID healthcare services [16].

There is a marked regional variation in most of the measures we have examined. To some extent, this variation may reflect temporal variations in the impact of the pandemic on different geographical regions. However, as well as variation in demand, different regions may vary in baseline capacity and ability to expand services. In regions or hospitals with lower numbers of critical care beds per head of population or staff per hospital bed, relatively smaller rises in community prevalence of COVID‐19 might lead to higher system stress. For instance, London has approximately 10 critical care beds per 100,000 head of population, compared with the South‐West, where the figure is less than six [17]. This perhaps partially explains why we observed similar impacts on service delivery in London and the South‐West region despite them having almost four‐fold differences in rates of critical care occupancy per head of population in the three periods of the survey [2].

The surveys in part illustrate the pressure points in the current system. These are clearly space and, most particularly, staff. The fact that critical care expansion requires redeployment of substantial numbers of anaesthetists is likely to have important implications for at least the next year, as critical care services work flexibly to address fluctuations in demand or step‐wise expansion. This in turn will have important implications for addressing surgical waiting lists. Expansion of both space and anaesthetic workforce are likely to be inevitable requirements.

There is some evidence that we sampled from hospitals with less systemic stress. The hospitals that responded, likely to represent between a third and half of all critical care units, reported approximately 900 mutual aid admissions in December 2020 to January 2021. This is broadly consistent with data from the Intensive Care Research and Audit Centre which recorded 1971 transfers between critical care units in December 2020 and January 2021, including 1634 for mutual aid [18] (compared with 54, one year previously) [19]. Our respondents reported 50% more mutual aid admissions to their hospitals than transfers out, and as each mutual aid transfer must have a decompressing and receiving unit, this provides some support for the idea that we preferentially sampled from less systemically stressed sites.

There are some limitations to our surveys. We have had decreasing response rates, falling to 50% in Round 3. In normal circumstances, some will consider response rates of above 60% to be necessary to be judged representative of the population sampled. Others regard 40% as sufficient [20]. Our surveys specifically targeted departments during a pandemic, including when capability pressures were increasing or saturated and survey responses were required rapidly. It is plausible, and perhaps likely that, within regions, the more systemically stressed hospitals were less likely to respond, and the data support this. It is therefore also plausible that the results of the survey underestimate the true extent of the ‘system stress’ due to failure to capture data from the most stressed part of the system. This is likely to be most marked when overall clinical pressure was highest, in R3. The surveys required respondents to compare activity at the time of the survey to activity a year previously and also to measure activity over 24 h. In some cases, the responses were estimated but sub‐analysis of only those reported as accurate did not change the overall results. Finally, for some regions, only a small number of hospitals replied so that these regional results may be less reliable.

In conclusion, we have documented the systemic stress on anaesthetic and peri‐operative services during the second wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the UK. This shows growing pressures between October and December 2020 because of critical care demands, predominantly on staff and space. Falls in surgical activity due to having to close operating theatres and reduce activity was mitigated by use of resources in other locations. In January 2021, shortly after the peak of the second surge, there is evidence that systemic resilience was overwhelmed; almost a third of anaesthesia staff were unavailable and surgical activity reduced to less than half, impacting all surgery, including cancer surgery and emergencies. At all times the greatest resource limitation was staffing, followed by space. The findings have important implications for understanding what has happened during the COVID‐19 pandemic and for planning recovery and building a system that will be better able to respond to future waves or new epidemics.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Information including red‐amber‐green rating: minimum requirements for restarting elective surgery and procedures, ICU staged resurgence plans and ACCC‐track results (Tables S1–S4 and Figures S1–S37).

Appendix S2. List of contributors including the NAP7 steering panel and the NAP7 local co‐ordinators and associated clinicians.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NAP7 local co‐ordinators and other clinicians who have completed any round of the ACCC‐track surveys. Those who have responded and expressed interest in being included in publication have been listed as contributors in the Supporting Information Appendix S2. We thank the NAP7 Steering Panel and the HSRC/RCoA research team including K. Williams (Audit Coordinator), J. Lourtie (Head of Research), S. Drake (Director of Clinical Quality and Research) and I. Moppett (Deputy Director) for supporting and collaborating on the project. The project was supported by the Health Service Research Centre at the Royal College of Anaesthetists who also partially fund the salary of J. Soar and T.M. Cook. No competing interests declared.

This article is accompanied by an editorial by Wong et al. Anaesthesia 2021; 76: 1151–4.

A summary of the results of Rounds 1 and 2 of the survey have been published on the Health Service Research Centre website at https://www.nationalauditprojects.org.uk/ACCC‐track‐Anaesthesia‐and‐Critical‐Care‐COVID‐Activity#pt.

Contributor Information

E. Kursumovic, @emirakur.

T. M. Cook, Email: timcook007@gmail.com, @doctimcook.

C. Vindrola‐Padros, @CeciliaVindrola.

A. D. Kane, @adk300.

R. A. Armstrong, @drrichstrong.

J. Soar, @jas_soar.

References

- 1. Intensive Care Society . Recovery and Restitution of Critical Care Services during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 2021. https://www.baccn.org/static/uploads/resources/Recovery_and_Restitution_‐_finalV2.pdf (accessed 08/04/2021).

- 2. Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre . ICNARC report on COVID‐19 in critical care: England. Wales and Northern Ireland. 2021. https://www.icnarc.org/Our‐Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports (accessed 08/04/2021).

- 3. Stevens S, Pritchard A. Third phase of NHS response to. COVID‐19. 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp‐content/uploads/sites/52/2020/07/Phase‐3‐letter‐July‐31‐2020.pdf (accessed 10/04/2021).

- 4. Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, Intensive Care Society, Association of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Anaesthetists . Anaesthesia and critical care: guidance for Clinical Directors on preparations for a possible second surge in COVID‐19. 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e6613a1dc75b87df82b78e1/t/5f68ce9ccda1805270405136/1600704156814/Second‐Surge‐Guidance.pdf (accessed 06/04/2021).

- 5. Health Research Authority . HRA decision tools: defining research. 2017. http://www.hra‐decisiontools.org.uk/research/docs/DefiningResearchTable_Oct2017‐1.pdf (accessed 10/04/2021).

- 6. NAP7 Sites . National Audit Project. 2020. http://www.nationalauditprojects.org.uk/NAP7‐Sites (accessed 01/11/2020).

- 7. NHS Digital . NHS Workforce Statistics, April 2020. 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/data‐and‐information/publications/statistical/nhs‐workforce‐statistics/april‐2020 (accessed 01/11/2020).

- 8. UK Government . Coronavirus (COVID‐19) in the UK. Healthcare in United Kingdom. 2021. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/healthcare (accessed 10/04/2021).

- 9. Frampton D, Rampling T, Cross A, et al. Genomic characteristics and clinical effect of the emergent SARS‐CoV‐2 B.1.1.7 lineage in London, UK: a whole‐genome sequencing and hospital‐based cohort study. Lancet Infectious Diseases 2021; S1473‐3099: 00170–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, Intensive Care Society, Association of Anaesthetists, Royal College of Anaesthetists . Restarting planned surgery in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic. 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e6613a1dc75b87df82b78e1/t/5eac2a173d65cd27933fca88/1588341272367/Restarting‐Planned‐Surgery.pdf (accessed 30/01/2021).

- 11. NHS Digital . NHS workforce statistics ‐ December 2020. 2021. https://digital.nhs.uk/data‐and‐information/publications/statistical/nhs‐workforce‐statistics/december‐2020 (accessed 08/04/2021).

- 12. Park N. Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland (accessed 10/04/2021).

- 13. Sury MRJ, Palmer JHMG, Cook TM, Pandit JJ, Mahajan RP. The state of UK anaesthesia: a survey of National Health Service activity in 2013. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2014; 113: 575–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. British Medical Association . Rest, recover, restore: GETTING UK health services back on track. 2021. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/3910/nhs‐staff‐recover‐report‐final.pdf (accessed 14/04/2021).

- 15. Cook TM, Roberts JV. Impact of vaccination by priority group on UK deaths, hospital admissions and intensive care admissions from COVID‐19. Anaesthesia 2021; 76: 608–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Price J, Sheraton T, Self R, Cook TM. The need for safe, stable and sustainable resumption of planned surgery in an era of COVID‐19. Anaesthesia 2021. Epub 28 March. 10.1111/anae.15470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Batchelor G. Revealed huge regional variation in NHS’ ability to meet coronavirus demand. Health Service Journal. 2020. https://www.hsj.co.uk/quality‐and‐performance/revealed‐huge‐regional‐variation‐in‐nhs‐ability‐to‐meet‐coronavirus‐demand/7027153.article (accessed 18/04/2021).

- 18. Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre . Table appendix. 2021. https://www.icnarc.org/Our‐Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports (accessed 08/04/2021).

- 19. Digital NHS. Critical Care Bed Capacity and Urgent Operations Cancelled 2019‐20 Data. 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical‐work‐areas/critical‐care‐capacity/critical‐care‐bed‐capacity‐and‐urgent‐operations‐cancelled‐2019‐20‐data/ (accessed 20/04/2021).

- 20. Story DA, Tait AR. Survey research. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Information including red‐amber‐green rating: minimum requirements for restarting elective surgery and procedures, ICU staged resurgence plans and ACCC‐track results (Tables S1–S4 and Figures S1–S37).

Appendix S2. List of contributors including the NAP7 steering panel and the NAP7 local co‐ordinators and associated clinicians.