Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic is a public health, economic and social crisis that is likely to have lasting consequences, including increased rates of financial hardship, housing insecurity, mental health problems, substance abuse and domestic violence. Workers in the community service sector have continued to support some of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged Australians during the pandemic, while also delivering services to new groups experiencing the economic impacts of virus suppression strategies. We surveyed community service sector workers from across Australia in three snapshots during April–May 2020 and found that perceptions of acute needs and organisational pressure points shifted even through this short period. While the sector faced significant challenges, it responded to the initial phase of the pandemic with flexibility, a strongly client‐centred approach and a re‐emphasis on collaboration between services. The community service sector's demonstrated capacity for agility and rapid adaptation suggests it is well placed to provide critical supports to those affected by crisis situations and everyday disadvantage. However, the sector's capacity to perform this role effectively depends on strong, stable government supports for all Australians in need.

Keywords: COVID‐19, community care, disadvantaged groups, Australia, pandemic

1. INTRODUCTION

The intersection of health, economic and social shocks during the COVID‐19 pandemic has magnified some long‐standing structural inequalities and produced new fault lines in Australian society. The community service sector 1 has been playing a vital role in supporting people affected by the crisis, and this is likely to continue as government supports (such as enhanced income assistance programmes) are withdrawn. The social and economic impacts of the pandemic have been cast into sharp relief in Australia as health impacts (in terms of illness, hospitalisation and mortality) have been at a smaller scale than in some other countries. 2

To explore how community service sector organisations were responding to early pandemic impacts, we deployed three snapshot surveys across Australia in April–May 2020. Our research found that community service sector organisations were able to respond to the socioeconomic effects of the virus and associated government actions with a focus on flexible and collaborative efforts to maintain critical service delivery. The community service sector response evolved rapidly through the early phase of the pandemic, with shifting perceptions of acute needs among client groups and organisational pressure points. The sector's capacity for rapid adaptation in the face of unexpected shocks suggests it is well positioned to respond to the continuing impacts of the pandemic with agility and recognised value.

2. THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF COVID‐19

Governments around the world have used a number of strategies to contain the direct public health threat of the COVID‐19 pandemic. These strategies tend to be multifaceted and vary widely in terms of stringency (see Blavatnik School of Government, 2020). Physical distancing, mask wearing, widespread testing and contact tracing are common elements of virus suppression strategies. Imposing some form of “lockdown”, which involves activating the coercive power of government to restrict citizens’ freedoms, is a more controversial measure. The term “lockdown” is used here to refer to mandated restrictions on travel, private and public gatherings, movement in public spaces and the operation of businesses and workplaces. Australian Governments have made substantial use of lockdown approaches during the pandemic, with some parts of the country experiencing stricter regimes than others 3 and different citizens being impacted differently.

The effects of lockdowns on people's social, psychological and economic well‐being are unclear over the medium to long term. During our data collection period in the early stages of the pandemic, indicators of deteriorating mental health among some groups were already being detected (Galea, Merchant & Lurie, 2020; Newby et al., 2020; Pierce, 2020; Van Rheenen et al., 2020). There were expectations that suicide rates could increase (Gratz et al., 2020; Kawohl & Nordt, 2020; Sher, 2020). Higher rates of domestic violence (Boxall, Morgan & Brown, 2020; Pfitzner et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020) and alcohol and substance abuse (Marsden et al., 2020) were becoming evident. People living with disability and others requiring care were being exposed to additional risks and sometimes finding their usual supports were not available (Collins, 2020). Lockdown can have the dual effect of exacerbating people's need for services at the same time as making services harder to access (Biddle & Gray, 2020).

This paper does not argue that the pandemic responses of Australian Governments have been unjustified or an overreach of government power. It does, however, contend that lockdowns, like the virus itself, do not affect all members of society equally. It was evident early in the pandemic that those who are already disadvantaged are at heightened risk of being adversely affected by the virus itself (see, e.g., Clarke & Whiteley, 2020; Finch & Finch, 2020; Niedzwiedz et al., 2020) and by lockdown constraints on social and economic activity (e.g., Wright, Steptoe & Fancourt, 2020).

Some elements of government pandemic responses exacerbate rather than ameliorate inequities. For example, the most punitive lockdown approach in Australia was that applied to public housing towers in Melbourne in July 2020 (ABC News, 2020). Groups whose jobs and wages were disproportionately affected by COVID‐19 from March to May 2020 included women, young people, lower paid workers, private renters and those already living in poverty before the pandemic (Davidson, 2020), but many people from these groups were excluded from government programmes addressing the economic impacts of the pandemic. Two of the most prominent Australian Government assistance programmes in place during the pandemic have been higher rates of “Jobseeker” payments for the unemployed and new “JobKeeper” payments incentivising employers to retain staff during the pandemic. However, most of Australia's 1.1 million temporary visa holders and 1 million short‐term casual workers were ineligible for JobKeeper payments, while another 2.1 million multiple job holders had limited eligibility, undermining the key policy objective of retaining employer–employee relationships (Cassells & Duncan, 2020).

Notwithstanding these exclusions, recent research by the Reserve Bank of Australia found that in the first 6 months of JobKeeper, it supported 3.5 million people and probably prevented around 700,000 people from losing their jobs (Bishop & Day, 2020). Modelling concluded that Australia's existing Social Security system would not have been able to respond adequately to the negative economic shocks generated by the pandemic. On an “after‐housing” measure, poverty would have increased from 3 million to 5.8 million people without the extra support payments, while with them, poverty and housing stress dropped to levels below what they were before COVID‐19 (Davidson, 2020; Phillips et al., 2020).

While these programmes can be celebrated as the “return of the visible state” and a welcome re‐politicisation of social need, they do not align well with the Coalition Government's preference for constrained spending and were always designed to be retrenched in time (Spies‐Butcher, 2020). Rollback of JobKeeper and the adjusted JobSeeker payments commenced from late September 2020, despite the pandemic continuing. Governments’ failure to continue to adequately support those in need, and to smooth out the unequal impacts of the pandemic on different groups in Australian society, potentially leaves some people vulnerable and undermines the legitimacy of exercising coercive power to the degree required for virus suppression. The survey data discussed in this paper shed some light on how these inequitable impacts played out in the community service sector during the initial pandemic response phase.

3. THE ROLE OF THE COMMUNITY SERVICE SECTOR

In keeping with a shift in Australia and other countries around the world over the last quarter‐century toward networked and collaborative approaches to the delivery of social services, the community service sector is critical to managing the social and economic consequences of the pandemic. While networked service delivery is a multifaceted concept, a key element in practice has been the increasing contracting out of social service delivery by government to third party providers, including nonprofit organisations (see, e.g., Milward & Provan, 2000; Osborne & Gaebler, 1992; Rhodes, 1996; Smith & Lipsky, 1993). In Australia, government funding for nonprofits doubled between 2000 and 2007 alongside increasing interdependency between the community sector and government, but funding growth slowed thereafter even though the demand for services continued to increase (Cortis, 2017).

The expansion of networked service delivery raises questions about how dependency on government funding might influence the activities of nonprofits (see, e.g., Mosley, 2012). Debate has also been generated around optimising funding for service provision in the context of collaborative and partnership arrangements between public and private/third sector agencies. Researchers have considered both the potential for government funding to “crowd out” other sources of nonprofit funding (see, e.g., Brooks, 2000; Carroll & Calabrese, 2017) and the risk of private funding “crowding out” government support, effectively resulting in the state abdicating its responsibility for social service provision (see, e.g., Becker & Cotton, 1994).

This aligns with what has been described as the “supplementary model” of government–nonprofit relations, in which nonprofits must step into the breach to meet demand for services government is not providing (and private funding for these services increases as government spending decreases) (Young, 2000). The “complementary model” emphasises nonprofit–government partnership, with private and government spending increasing together. A third view, the “adversarial model”, posits that nonprofits engage in advocacy to influence policy and hold government to account while governments attempt to influence and regulate the activities of nonprofits (Young, 2000).

Our research into the community service sector's response to the early stages of the COVID‐19 pandemic highlighted the key role the sector plays, after several decades of networked service delivery, in supporting vulnerable Australians in times of crisis and on a day‐to‐day basis. However, this does not give the state licence to step out of the field. The work of the community service sector must be well scaffolded by government supports (such as the Australian Government's supplemented income assistance programmes introduced in 2020). A complementary approach, emphasising partnerships, collaboration and increased government spending on social services, best supports the needs of Australians experiencing hardship and disadvantage, notwithstanding the inevitable implementation tensions and challenges involved (see, e.g., Butcher & Gilchrist, 2020). Effective collaborations between government and non‐government partners are particularly important at times of crisis when needs may be exacerbated, new groups may encounter hardship and private funding sources may dry up.

4. RESEARCH APPROACH

The research was intended to be a rapid review assessing the community sector's immediate reaction to the pandemic, rather than a rigorous in‐depth analysis of the sector's sustained response over time. The project was designed and implemented in tight time frames to capture a real‐time perspective on the evolving pandemic situation in April–May 2020. Following fast‐tracked ethical approval, an online survey was distributed to 391 community service sector contacts across Australia, with an invitation for them to disseminate the survey further via snowballing if they wished. The distribution list was built by drawing on the researchers’ extensive networks in the community service sector and supplemented by online searches for peak/national bodies and NGOs, with the aim of identifying organisations providing services and supports targeting people experiencing disadvantage and/or marginalisation of some kind. The groups supported by organisations on the distribution list included people experiencing housing stress and homelessness, disability, mental health issues, domestic violence, financial exclusion and legal problems, as well as families with children under 18, young people aged up to 25, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, refugees and migrants, and seniors.

Of the 391 contacts on the survey distribution list, 279 different organisations (or branches of organisations) were included. While representatives of many prominent organisations in Australia's community service sector were included, 279 organisations and 391 contacts is only a small fraction of the sector. In November 2020, nearly 480,000 Australians were employed in “social assistance” roles (and an additional 238,000 in “residential care” roles), while over 1.3 million were classified as “community and personal service workers” (ABS, 2020b). Defining the Australian community service sector relatively narrowly as personal welfare, childcare, aged care and crisis accommodation services, it comprises 18,473 “businesses”, employs 788,000 people and is expected to grow by 3%–5% over the next 5 years (Richardson, 2020). The survey results do not reflect the diversity of the sector across Australia, rather than the experiences of a range of individuals and organisations within the sector, with organisations based in South Australia over‐represented due to recruitment biases.

The survey was deployed three times during an Australia‐wide lockdown period in April–May 2020, with a total of 299 completed surveys across the three snapshots. The first snapshot was open from 6 to 13 April; the second from 20 to 27 April; and the third from 4 to 11 May. Sixty‐four responses were received for the first snapshot, 136 for the second and 99 for the third. Management‐level staff were initially targeted, with the survey expanded to include frontline staff for the second and third snapshots following feedback from the sector that the experience of these workers was important to capture. The distribution list for the first snapshot comprised a subset of approximately 200 of the final 391 contacts as it was restricted to line and executive manager contacts. Table 1 shows the distribution of management‐level and frontline respondents across the three snapshots. The response rate for the first snapshot was approximately 32%; for the second, it was 35%; and for the third, it was 25%. 4

TABLE 1.

Survey responses by respondent type

| Respondent type | Snapshot 1 | Snapshot 2 | Snapshot 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership or line management | 64 | 69 | 56 |

| Frontline worker | n/a | 67 | 43 |

| Total | 64 | 136 | 99 |

The research team was acutely aware of the overwhelming demands on the time and energy of community service sector workers at the time of data collection and aimed to keep the survey simple while still generating useful data for the sector for reflection and advocacy. The survey produced both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data were analysed using basic statistical methods, and the qualitative data were analysed thematically. Independent t‐tests and the chi‐square tests were used to check for statistical significance of data variations between snapshots and between the two respondent groups. However, caution is necessary in comparing results between snapshots because the respondent samples were different in each snapshot. Under the challenging conditions and time pressures created by the pandemic, only some respondents were able to complete all three surveys. 5

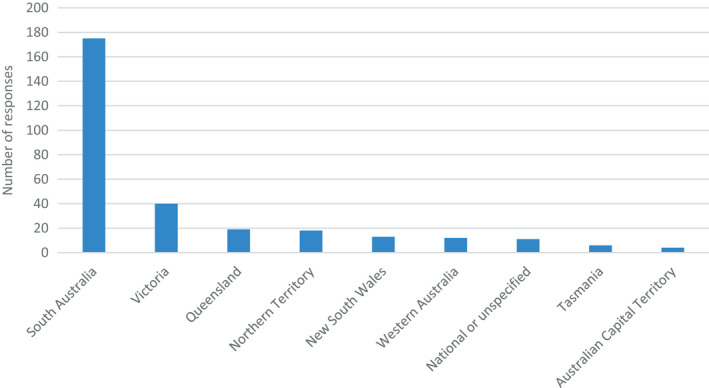

The contacts on the survey distribution list from each state/territory, along with the responses recorded from each jurisdiction, are given in Table 2. It is not possible to meaningfully calculate response rates by state/territory because many of the contacts recorded as “unspecified or national” in the distribution list specified a particular state/territory in their survey response. For comparison purposes, Figure 1 shows how the 299 responses across the three snapshots were distributed by jurisdiction. Participants based in South Australia were over‐represented. The researchers’ strong links with the community sector in this jurisdiction meant it had the highest number of participants on the contact distribution list. It is also possible that contacts in South Australia were more likely to respond because they were more familiar with the researchers and their home institution. This limitation means the data are more representative of the community sector in South Australia than other states. However, unlike later in 2020, the pandemic and lockdown experience in April–May 2020 was similar across states.

TABLE 2.

Sample and survey responses by state/territory

| State/territory that organisation operates in | Number on distribution list | Snapshot 1 responses | Snapshot 2 responses | Snapshot 3 responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Capital Territory | 14 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| New South Wales | 64 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Northern Territory | 45 | 6 | 9 | 3 |

| Queensland | 20 | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| South Australia | 93 | 31 | 77 | 67 |

| Tasmania | 29 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Victoria | 37 | 5 | 25 | 11 |

| Western Australia | 26 | 2 | 9 | 1 |

| National or unspecified | 63 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| Total | 391 | 64 | 136 | 99 |

FIGURE 1.

Survey responses by state/territory (all respondents) (n = 299)

Survey participants were drawn from organisations operating across urban, regional and remote areas. Table 3 shows the percentage of respondents who said their organisation delivered programmes in each of these areas. A number of respondents said their organisation worked across more than one area: 57% in snapshot 1; 26% in snapshot 2; and 17% in snapshot 3. The higher rate of working in more than one area in snapshot 1 may reflect that these respondents were all managers and taking a higher‐level perspective of organisational operations than some frontline staff.

TABLE 3.

Programme delivery areas for respondents’ organisations (snapshot 1, n = 64; snapshot 2, n = 69; and snapshot 3, n = 56) (totals are >100% as most respondents cited more than one delivery area)

| Delivery area |

Snapshot 1 % of respondents |

Snapshot 2 % of respondents |

Snapshot 3 % of respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 80% | 48% | 58% |

| Regional | 71% | 60% | 54% |

| Remote | 28% | 30% | 14% |

The survey distribution list included contacts from organisations operating across the community service sector. Table 4 shows the primary areas of service provision for contacts’ organisations and for frontline workers who responded to the survey in snapshots 2 and 3. The survey did not ask management‐level respondents about their primary area of service provision because it was assumed many would be responsible for multiple areas. The distribution list included many contacts from large organisations in the community service sector, such as Anglicare, Catholic Care, St Vincent de Paul, Brotherhood of St Laurence, the Red Cross, Mission Australia and the Salvation Army, which tend to deliver services across a range of areas.

TABLE 4.

Primary area of service provision for survey contacts and frontline worker respondents

| Primary area of service provision/activity | Number on distribution list | Number of frontline worker responses (snapshot 2) | Number of frontline worker responses (snapshot 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General/multiple | 157 | 1 | 1 |

| Services for youth and families with children | 39 | 16 | 15 |

| Services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples | 34 | 4 | 0 |

| Financial, legal and advocacy support | 30 | 8 | 4 |

| Education and training | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| Disability support | 19 | 2 | 2 |

| Housing and homelessness services | 17 | 8 | 11 |

| Services for refugees and migrants | 14 | 1 | 0 |

| Domestic violence support services | 12 | 8 | 2 |

| Services for seniors | 11 | 3 | 0 |

| Government agency | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Mental health services | 10 | 13 | 3 |

| Sport | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Unspecified | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Alcohol, drug and gambling support services | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Emergency relief and low‐income support | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 391 | 67 | 43 |

5. RESULTS

The survey results suggest that the virus itself had only a limited health impact on community service sector organisations and their clients, largely because Australian infection and mortality rates remained relatively low during the initial phase, but the socioeconomic effects of lockdown had a significant effect. Survey respondents reported increasing demand for services and workloads during the data collection period and changing perceptions of client needs and organisational pressure points.

5.1. Staffing issues

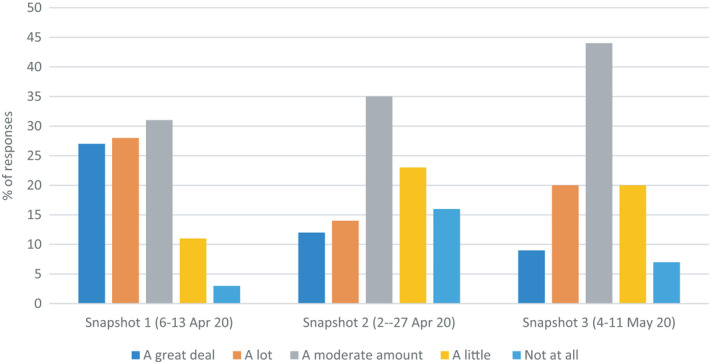

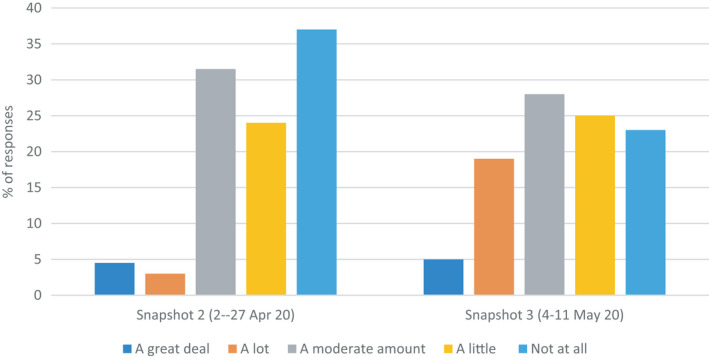

Concerns about the virus itself were initially high. In the first snapshot, 97% of managers thought their frontline staff were at heightened risk of exposure to COVID‐19, and over half described the additional risk as “a great deal” or “a lot”. Concern declined substantially between the first and second snapshots (see Figure 2). An independent two‐sample t‐test conducted to compare the results for snapshots 1 and 2 found the difference was significant. 6 However, the difference between snapshots 2 and 3 was not significant. 7

FIGURE 2.

Are your frontline staff at heightened risk of exposure to COVID‐19? (managers) (snapshot 1, n = 64; snapshot 2, n = 69; and snapshot 3, n = 56)

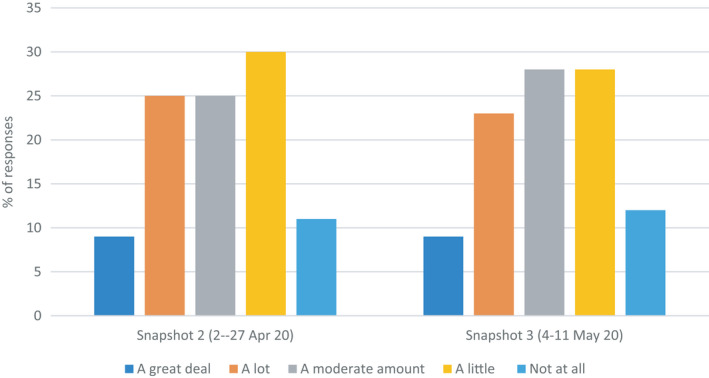

Frontline workers themselves were asked in the second and third snapshots whether they felt they were at heightened risk of COVID‐19 in carrying out their day‐to‐day duties. Eighty‐nine per cent felt they were at some heightened risk in the second snapshot and 88% in the third snapshot (around a third described the additional risk as “a great deal” or “a lot” each time) (see Figure 3). Independent two‐sample t‐tests indicated frontline workers and managers made similar assessments of the risk of frontline staff being exposed to the virus during their work at the time of both snapshot 2 and snapshot 3. 8

FIGURE 3.

In carrying out your day‐to‐day duties, do you feel you are at heightened risk of exposure to COVID‐19? (frontline workers) (snapshot 2, n = 67; and snapshot 3, n = 43)

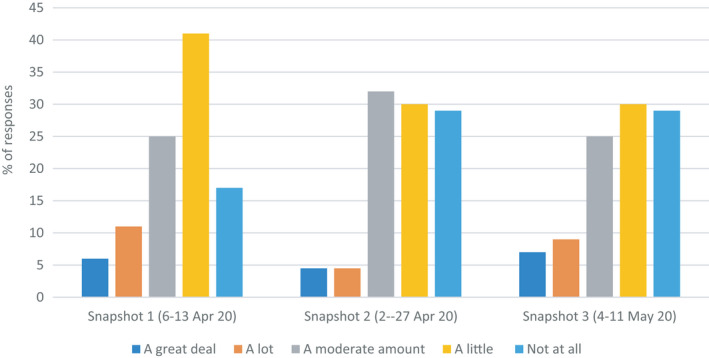

It was expected that maintaining staffing levels would be a significant problem for community service sector organisations during the lockdown period, particularly due to self‐isolation/quarantine requirements, but this was not the case. Only a small proportion of respondents in management positions reported a significant impact on their staffing levels (see Figure 4). An independent two‐sample t‐test conducted to compare the results between snapshots found no significant differences over time. 9

FIGURE 4.

Have your current staffing levels been impacted by COVID‐19? (managers) (snapshot 1, n = 64; snapshot 2, n = 69; and snapshot 3, n = 56)

Only one case of actual COVID‐19 infection (of a staff member or someone in their household) was reported, though being in self‐isolation and at high risk of infection were common causes of staffing disruption at the time of the first snapshot. Child care responsibilities were another common cause of staffing issues. In the first snapshot, 30% of managers said they were actively attempting to recruit staff to assist with managing demand on their organisations because of the COVID‐19 crisis, but this had dropped to 16% in the second snapshot and 14% in the third. The fact that neither the community service sector nor the public health system has been overwhelmed by increased demand during the pandemic, despite initial fears and the experience in some other countries, suggests that Australian Governments’ virus suppression strategies have been highly effective in many respects. However, a majority of frontline workers did say they had experienced increased workloads due to COVID‐19, especially in the third snapshot (see Figure 5), although the difference between the second and third snapshots was not statistically significant. 10

FIGURE 5.

Has your workload increased due to the COVID‐19 crisis? (frontline workers) (snapshot 2, n = 67; and snapshot 3, n = 43)

5.2. Client needs

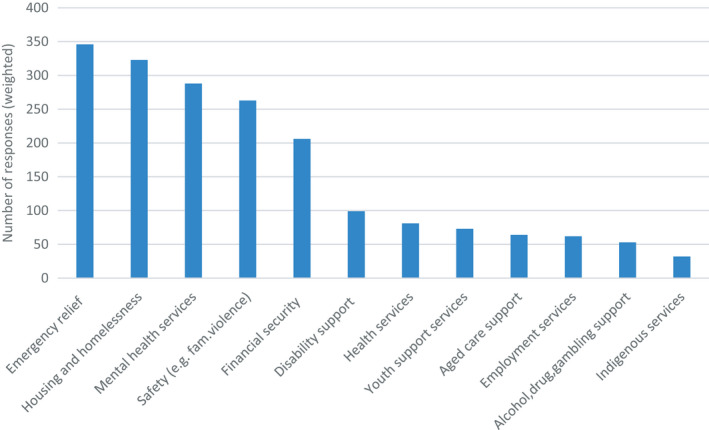

Survey respondents were asked to select the first, second and third most acute needs for their client bases during the previous seven days. The total weighted responses 11 for all respondents across the three snapshots are shown in Figure 6. The five most acute needs during the survey period were for emergency relief, housing security, mental health support, safety (including protection from family violence) and financial security. 12 Social engagement and digital inclusion were the most commonly mentioned acute needs by respondents who selected an “other” response and provided further information.

FIGURE 6.

What have been the most acute needs for your client base over the last 7 days (all respondents)?

There were some shifts in the perception of acute needs even in the short time frames between snapshots, illustrating how rapidly the pandemic situation evolved in the April–May 2020 period. Concerns about emergency relief and housing/homelessness were highest in the third snapshot. Mental health concerns peaked in the second snapshot and remained high in the third. Concerns about safety and financial security issues peaked in the second snapshot but eased a little in the third. A chi‐square test of independence found there was a significant variation in the acute needs identified for each snapshot 13 , although some variation is likely attributable to the different mix of services represented by respondents in each snapshot.

Clients with mental health [issues] that have no other support systems in place were beginning to socialise but are now withdrawn again (Survey participant 19, snapshot 2).

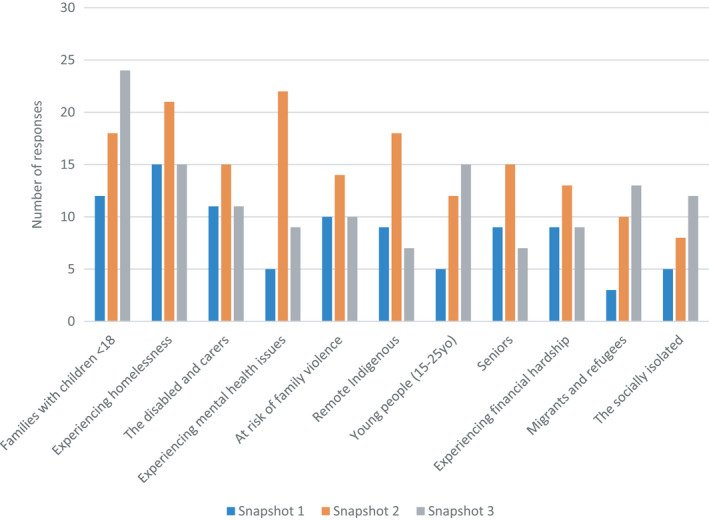

In an open‐ended question, survey respondents were asked which groups of people in the communities they served were most at risk of not having their needs met during the pandemic. This question, as well as one on organisational pressure points (see below), was intentionally framed to allow respondents latitude to respond on their own terms, rather than being required to select from set options. The open‐ended questions generated qualitative data, which were coded according to categories emerging from the data rather than being predetermined by the researchers. The total responses for all respondents by snapshot are shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Which group(s) of people in the communities you serve do you consider the most at risk of not having their needs met currently? (i.e., who is falling through the system) (all respondents) (n = 299)?

Families with children under 18 were the group of greatest concern across the data collection period. The qualitative data suggested that respondents were worried about the impact of social isolation on this group, particularly with children not attending school, and service providers’ inability to monitor family situations through home visits. Concerns for young people, migrants and refugees, and people who were socially isolated also appeared to increase over the course of the data collection. However, the chi‐square testing indicated the distribution of responses did not vary significantly between snapshots 14 and some variation is likely attributable to the different mix of services represented by respondents in each snapshot. Some respondents were commenting from the perspective of organisations delivering services to multiple different client groups, while others were from more specialised organisations or specific programmes within generalist organisations. The latter group are likely to have had a heightened awareness of needs within the client base they were familiar with, and less awareness of needs among other groups. However, most respondents identified multiple groups they thought were at risk of not having their needs met, which suggests they were taking a relatively broad view across the community rather than focusing narrowly on their own specific client groups.

5.3. Organisational pressure points

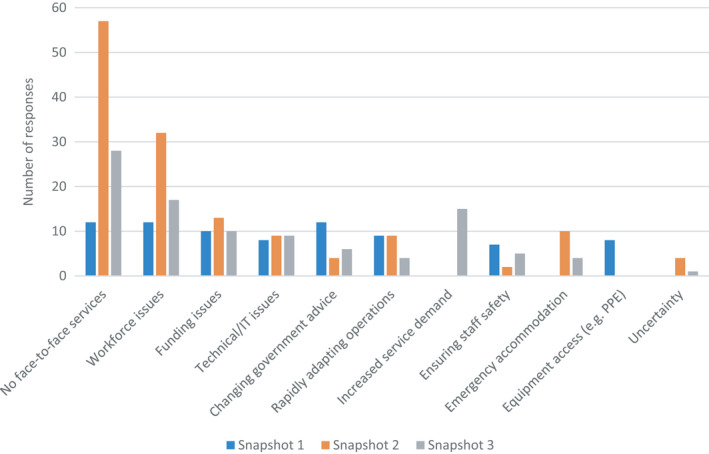

In another open‐ended question, survey respondents were asked about the most significant pressure or pain points their organisations were experiencing. The total responses for all respondents by snapshot are shown in Figure 8. Most identified multiple pressure points. Some early pressure points, such as accessing supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) and hand sanitiser and ensuring changing government advice was adhered to, eased quickly. The emergence of increased service demand as a key pressure point in snapshot 3 was notable. 15

FIGURE 8.

What is your biggest pressure/pain point as an organisation right now? (all respondents) (n = 299).

Practical difficulties around continuing to deliver services with physical distancing in place were the most significant concern across the data collection period, though easing by the third snapshot as organisations adapted to the new circumstances. The difficulty of not having face‐to‐face contact with clients, including in their home environments, was repeatedly highlighted in the qualitative data. Face‐to‐face interactions are used to build trust and rapport and make observations about clients’ circumstances which inform how their cases are managed (including in terms of risks and vulnerability). Many organisations, notably those supporting families and children at risk, had to rapidly devise new forms of client engagement.

Workforce‐related issues such as covering staff absences and supporting staff working remotely remained a significant pressure point for the duration of the data collection period. Survey participants were conscious of the importance of looking after each other and pulling together to get through the crisis: “We are not alone in this, it is larger than most thought it would be” (Survey participant 6, snapshot 1).

[Our biggest challenge is] ensuring we can operate safely whilst maintaining the intensity of supports needed to assist people during this frightening and intense time (Survey participant 8, snapshot 1).

Our team are proud to be an essential service and working really well to support each other through this time (Survey participant 8, snapshot 1).

Funding constraints were a significant pressure point, but possibly not to the extent that might have been expected. This may be partly because the economic effects of the pandemic are likely to play out over a much longer period of time than our data collection period. Increased government spending and borrowing during the pandemic could give rise to budgetary pressures over coming years, which reduce the funding available for community services even as the demand increases. This may be mitigated by increased funding to some parts of the sector, such as the Australian Government's announced $150 m in additional funding to support victims of family and domestic violence, $200 m for organisations providing emergency relief services (Prime Minister of Australia, 2020) and $48 m for a mental health and well‐being plan (Department of Health, 2020b).

Greater flexibility around contracting arrangements between governments and community service organisations would augment the sector's capacity for rapid, adaptive responses to crisis situations. Research with the Australian community sector undertaken in July 2020, as the pandemic progressed, found organisations had varying experiences with government partners over the preceding 4 months; around half of those surveyed reported positive engagement and increased funding flexibility (Cortis & Blaxland, 2020). Most organisations had not experienced any reduction in government funding up to that point, but loss of commercial and philanthropic funding was common. In other research undertaken in July–August 2020, over three‐quarters of surveyed organisations from the for‐purpose sector were reporting considerable strain on their finances as a result of the pandemic (Muir et al., 2020).

Flexibility was a key feature of how community sector organisations managed pandemic‐related pressure points, and survey respondents were asked to share some of their innovations in an open‐text field in the survey. A number of organisations said they found new ways of keeping clients engaged with services, including conducting “footpath drop‐offs” of food parcels, pamper packs, survival kits and Easter baskets. Many organisations reported moving to online service delivery, aligning with research undertaken later in the pandemic (July–August 2020) indicating a substantial shift to digital delivery modes across the for‐purpose sector, while acknowledging that a proportion of the sector's client base (and some organisations) experience “digital exclusion” (Muir et al., 2020). Some of our respondents said they addressed this by providing clients with iPads, Zoom accounts and data packs.

Such practice innovations not only helped staff and clients to cope with the acute phase of the pandemic but also generated improvements to service delivery that could be retained post‐pandemic. Clients’ new familiarity with online platforms may open up more choices around service delivery models in the future.

We are using Zoom to continue to provide dance classes for people with disability in their own homes (Survey participant 127, snapshot 2).

We have had some unexpected successes with remote online counselling, especially with kids, who feel more comfortable in the home than in a clinical setting (Survey participant 115, snapshot 2).

Survey respondents also recognised remote working as a more viable option in the future. There was a heightened awareness of the importance of working together, including improved communication between staff, stronger links between organisations and greater sharing of information and resources. Survey respondents cited flexibility and positivity as key elements of an effective COVID response.

Collaboration has never been this good! (Survey participant 106, snapshot 2).

Communities have banded together like never before (Survey participant 59, snapshot 1).

6. DISCUSSION

The survey results not only revealed difficulties for the community service sector during the early phase of the pandemic, but also reflected organisations’ agility, responsiveness and resilience. Some predicted challenges for the sector (reduced staff capacity, supporting highly vulnerable groups such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and seniors) were not as bad as might have been expected. Other challenges (accessing equipment such as PPE, adapting to non‐face‐to‐face service delivery modes) eased quite quickly. On the other hand, the sector reported significant concerns about groups such as families with children, young people, migrants and refugees, people experiencing mental health issues and those at risk of family violence during the early phase of the pandemic.

The community service sector's early pandemic experience provided some stark illustrations of how government policy can protect or expose the vulnerable in crisis situations. One of the good news stories to emerge was the temporary accommodation strategy enacted for rough sleepers (albeit to varying degrees) by state governments in collaboration with community service sector organisations (see Mason et al., 2020; Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, 2020; Parsell, Clarke & Kuskoff, 2020). This response demonstrated the potential for rapid, coordinated policy innovation to produce effective results, and created an opportunity to put in place more sustainable recovery pathways for people experiencing homelessness (Mason et al., 2020).

Other vulnerable groups were left out of government policy responses. By the third snapshot of our survey, respondents were reporting an increased demand for services driven by an influx of new clients, largely people ineligible for government support measures such as casual employees and temporary visa holders (Berg & Farbenblum, 2020; Clibborn & Wright, 2020; Phillips, 2020). Our results from early in the pandemic align with results from subsequent research with community organisations (undertaken in July 2020), which found “the community sector is enormously impacted by the exclusions of key populations from government support systems” (Cortis & Blaxland, 2020, p. 8). These new client groups are a reminder that the costs of the pandemic have not been borne equally across Australian society.

[Those most at risk are] people on temporary visas who are excluded from all government assistance in situations where repatriation isn’t an option (Survey participant 12, snapshot 3).

As would be expected after years of governments outsourcing social service provision, the sector's contribution to supporting people experiencing disadvantage or marginalisation is critical to maintaining a strong social safety net. This is particularly true when government supports allow some vulnerable groups to fall through the gaps, as was the case with the income assistance programmes introduced to help address the economic impacts of the pandemic. Our survey results suggest that the community service sector is well placed to respond rapidly and effectively to emerging crisis situations and providing routine support for people experiencing disadvantage. Research with the sector undertaken later in the pandemic (July to August 2020) indicates that the process of rapid adaptation continued beyond the initial phase of the pandemic (Cortis & Blaxland, 2020; Muir et al., 2020). However, the community sector's work should be conducted in collaborative partnership with governments, and as a complement to public service provision, not as a substitute for it.

The survey results suggested that groups in need and pressure points for community service organisations can shift rapidly as fluid crisis situations evolve. In these situations, community service sector organisations may be better placed than bureaucracies to respond with agility. Governments working in partnership with community organisations can facilitate this responsiveness through rapid funding mechanisms and clear but flexible key performance indicators.

Crisis situations generate immediate acute needs, often concentrated among particular groups rather than spread evenly across society. This research sought to examine the crisis response in the community service sector during the initial phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Like other crises (including natural disasters and climate‐related events such as bushfire, flood and extreme weather), the pandemic will also have lasting effects and generate opportunities for change. It has temporarily opened policy windows, which may make systemic reforms more achievable (see, e.g., Auener et al., 2020), but there is also a risk that governments will roll back public support measures and revert to the pre‐pandemic policy status quo.

6.1. Limitations

The research has significant limitations, which should be borne in mind when interpreting the data. These limitations largely arise from the time constraints within which the survey was designed and deployed. The research was intended as a rapid real‐time review rather than a systematic, in‐depth analysis, and the dataset is relatively small. Community service sector organisations based in South Australia were over‐represented, and specific issues in particular service areas and geographic locations are obscured. The community service sector is large and highly diverse, with the survey data capturing the experience of just a small sample of individuals and organisations. The survey distribution list was not intended to be representative of the Australian community service sector as a whole: constructing the list systematically was not possible in the time frame available. Instead, the list aimed to maximise response rates by drawing on researchers’ professional networks, on the assumption that familiarity with the research team and host university would make response more likely at a time when potential participants were under a great deal of pressure.

The time series data generated by the three snapshots illustrates shifting concerns and pressure points, but trends should be interpreted cautiously as each snapshot had different participants. The changing composition of the samples is likely to have affected the data on perceived acute issues and client groups most at risk. There was also a relatively high rate of respondents partially completing surveys: across the three waves, 425 surveys were commenced, but 127 were incomplete and are not included in the data analysis. These limitations reflect the difficulties of conducting research in a complex, rapidly evolving real‐world setting encompassing a diverse range of organisations.

7. CONCLUSION

Our research with the Australian community service sector during the early phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic in April–May 2020 is a reminder that the effects of this crisis go beyond public health impacts and must be viewed holistically. Survey respondents indicated that the five most acute needs for their clients during this period were for emergency relief, housing security, mental health support, safety and financial security. Respondents reported high levels of concern for families with children, young people, migrants/refugees and people with mental health issues as the implications of the pandemic and associated suppression strategies became clearer. While the sector adapted effectively to new modes of service delivery, and staff capacity was not compromised to the degree initially expected, respondents reported that demand for services was becoming a pressure point by the third snapshot, and a majority of frontline workers said their workloads were impacted.

Our survey findings suggest that Australia is well served even in crisis situations by an adaptable, resilient community service sector, characterised by strong collaboration and a commitment to client‐centred practice and outcomes. However, the sector remains in a state of flux, with a high degree of uncertainty about the medium‐ and longer‐term future, as the effects of the pandemic continue. It is vital that Australian Governments recognise the ongoing socioeconomic impacts of their pandemic response strategies, including the unevenness of these impacts, and invest trust, resources and capacity in a community service sector that is well placed to support those most affected.

Further investigation of the ongoing challenges experienced by the community service sector in the post‐COVID‐19 period is required. Our study points the way to potentially fruitful avenues of inquiry relating to the sector's ability to respond adaptively to crisis (while government bureaucracies may take longer to react); address the needs of new client groups; and embrace opportunities for service delivery improvements. It also highlights the need for community service sector staff to be well supported through crisis periods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by Dr Catherine McKenzie, Dr Laurence Lester, Mr David Pearson and Ms Kelly McKinley. They thank the staff from community service sector organisations across Australia for taking the time to contribute their reflections during a very challenging period. The authors are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for the feedback provided on this paper.

Biographies

Dr Veronica Coram is Research Fellow at The Australian Alliance for Social Enterprise, University of South Australia. Her research focuses on housing, social policy and inequality. She has a particular interest in policy, practice and service delivery for children, families and young people.

Dr Jonathan Louth is Industry Adjunct at The Australian Alliance for Social Enterprise, University of South Australia. He is also Executive Manager for Strategy, Research and Evaluation at a large not‐for‐profit organisation. His research focuses on social policy and the political economy of the lived experience. This has informed work on gender, spatial politics, neoliberal governance, financialisation and the impact of economic thought. He also has an interest in electoral politics focusing on marginalised communities.

Dr Selina Tually is Senior Research Fellow at The Australian Alliance for Social Enterprise, University of South Australia. She is Geographer and Social Researcher driven by understanding how people and places interact, especially to improve social policy and practice for vulnerable people in our communities. Her research expertise and interests centre on the fields of housing and homelessness, community, local and regional economic development and enterprise in communities and social services.

Professor Ian Goodwin ‐Smith is Director of The Australian Alliance for Social Enterprise, University of South Australia. He has extensive experience in research and evaluation relating to social service improvement, social service system reform and social policy. He has a history of working with non‐government organisations, all tiers of government, communities and people who have been marginalised.

ENDNOTES

The term “community service sector” is used broadly in this paper to describe the range of organisations working in Australia to provide services and supports to people experiencing some form of marginalisation or disadvantage, including poverty, disability, frailty, domestic violence, homelessness and mental health issues. These organisations are largely not‐for‐profits but also include private businesses and some government agencies.

As of 13 January 2021, Australia had recorded 28,634 cases of COVID‐19 with 909 deaths (Department of Health 2020a) among a population of some 25.6 million people (ABS 2020a).

For example, under Melbourne's Stage 4 restrictions in place in August–September 2020, people could leave their homes only to shop for essentials within a 5‐km radius, provide care, exercise for up to an hour once a day within a 5‐km radius and work if they were not able to work from home. An 8 pm to 5 am curfew was in place, and non‐essential business, services and activities, including schools, were closed.

These response rates do not take into account that snowballing may have occurred through contacts on the distribution list forwarding the survey to others.

The research was not in panel survey form so there were not paired responses.

t(131) = 4.08, p = <.001.

t(123) = −1.05, p = .15

For snapshot 2, t(134) = −0.49, p = .63; for snapshot 3, t(84) =0.57, p = .57.

For snapshots 1 and 2, t(129) = 1.27, p = .21; for snapshots 2 and 3, t(111) = −0.54, p = .59.

Independent two‐sample t‐test results were t(91) = 0.83, p = .41.

The second most acute factors were weighted at half the first most acute, and the third most acute at half the second most acute.

Chi‐square testing indicated there were no statistically significant differences in responses between managers and frontline workers: for snapshot 2, X2 (11, N = 24) = 4.14, p = .96; for snapshot 3, X2 (10, N = 22) =10.67, p = .95.

X2 (22, N = 36) = 69.29, p = <.001.

X2 (20, N = 33) = 24.48, p = .22.

The chi‐square testing indicated the distribution of responses varied significantly between snapshots: X2 (20, N = 33) = 102.14, p = <.001.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- ABC News (2020) Coronavirus forces lockdown of Melbourne public housing towers in 3051 and 3031 postcodes. This is what that means for the residents. 5 July 2020. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020‐07‐04/coronavirus‐victoria‐melbourne‐public‐housing‐estates‐lockdown/12423042 [Accessed 6 July 2020].

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2020a) Population clock. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs%40.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/1647509ef7e25faaca2568a900154b63?OpenDocument [Accessed 5 July 2020].

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2020b) Labour force, Australia, detailed. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment‐and‐unemployment/labour‐force‐australia‐detailed/latest‐release#industry‐occupation‐and‐sector [Accessed 12 January 2021].

- Auener, S. , Kroon, D. , Wackers, E. , Van Dulmen, S. & Jeurissen, P. (2020) A window of opportunity for positive healthcare reforms. International Journal of Health Policy Management, 9(10), 419–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, E. & Cotton, M.L. (1994) Does the government free ride? The Journal of Law and Economics, 37(1), 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, L. & Farbenblum, B. (2020) As if we weren’t humans: the abandonment of temporary migrants in Australia during COVID‐19. Sydney: Migrant Worker Justice Initiative. Available at: https://www.mwji.org/covidreport [Accessed 22 September 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, N. & Gray, M. (2020) Service usage and service gaps during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Canberra: ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University; Available at: https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/2020/6/Service_usage_during_COVID‐19.pdf [Accessed 4 July 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J. & Day, I. (2020) How many jobs did JobKeeper keep? Research Discussion Paper 2020‐07, Economic Research Department, Reserve Bank of Australia. Available at: https://rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2020/pdf/rdp2020‐07.pdf [Accessed 13 January 2021].

- Blavatnik School of Government (2020) Coronavirus government response tracker. University of Oxford. Available at: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research‐projects/coronavirus‐government‐response‐tracker [Accessed 9 September 2020].

- Boxall, H. , Morgan, A. & Brown, R. (2020) The prevalence of domestic violence among women during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Statistical Bulletin 28, Australian Institute of Criminology. Available at: https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020‐07/sb28_prevalence_of_domestic_violence_among_women_during_covid‐19_pandemic.pdf [Accessed 2 September 2020].

- Brooks, A.C. (2000) Public subsidies and charitable giving: crowding out, crowding in, or both? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 19(3), 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, J. & Gilchrist, D. (2020) Collaboration for impact. Canberra: ANU Press (Australia and New Zealand School of Government series). [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, D.A. & Calabrese, T.D. (2017) Intersecting sectors? The connection between nonprofit charities and government spending. Journal of Public and Nonprofit Affairs, 3(3), 247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Cassells, R. & Duncan, A. (2020) JobKeeper: the efficacy of Australia’s first short‐time wage subsidy. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 23(2), 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, H. & Whiteley, P. (2020) Economic inequality can help predict COVID‐19 deaths in the US. London School of Economics US Centre. Available at: https://bit.ly/2YBI31T [Accessed 2 July 2020].

- Clibborn, S. & Wright, C.F. (2020) COVID‐19 and the policy‐induced vulnerabilities of temporary migrant workers in Australia. The Journal of Australian Political Economy, 85, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A. (2020) Disability sector left vulnerable by coronavirus response despite early warnings, Royal Commission hears. ABC News, 20 August 2020. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020‐08‐20/disability‐sector‐left‐vulnerable‐by‐coronavirus‐commission/12576918 [Accessed 25 August 2020].

- Cortis, N. (2017) Access to philanthropic and commercial income among nonprofit community service organisations. Voluntas, 28(2), 798–821. [Google Scholar]

- Cortis, N. & Blaxland, M. (2020) Australia’s community sector and COVID‐19: supporting communities through the crisis. Sydney: Australian Council for Social Service. Available at: https://www.acoss.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2020/09/Australias‐community‐sector‐and‐Covid‐19_FINAL.pdf [Accessed 13 January 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, P. (2020) Inequality in Australia, part 1: overview, supplement: the impact of COVID‐19 on income inequality. Sydney: Australian Council of Social Service and UNSW. Available at: https://apo.org.au/node/308015 [accessed 13 January 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2020a) Coronavirus (COVID‐19) current situation and case numbers. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/news/health‐alerts/novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov‐health‐alert/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐current‐situation‐and‐case‐numbers [Accessed 24 October 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2020b) COVID‐19: $48.1 million for National Mental Health and Wellbeing Pandemic Response Plan. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the‐hon‐greg‐hunt‐mp/media/covid‐19‐481‐million‐for‐national‐mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐pandemic‐response‐plan [Accessed 2 September 2020].

- Finch, W.H. & Finch, M.E.H. (2020) Poverty and COVID‐19: rates of incidence and deaths in the United States during the first 10 weeks of the pandemic. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 10.3389/fsoc.2020.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea, S. , Merchant, R.M. & Lurie, N. (2020) The mental health consequences of COVID‐19 and physical distancing. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K.L. , Tull, M.T. , Richmond, J.R. , Edmonds, K.A. & Rose, J.P. (2020) Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness explain the associations of COVID‐19 social and economic consequences to suicide risk. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 50(6), 1140–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawohl, W. & Nordt, C. (2020) COVID‐19, unemployment and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 389–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, J. , Darke, S. , Hall, W. , Hickman, M. , Holmes, J. , Humphreys, K. et al. (2020) Mitigating and learning from the impact of COVID 19 infection on addictive disorders. Addiction, 115(6), 1007–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C. , Moran, M. & Earles, A. (2020) Policy coordination and housing outcomes during COVID‐19. AHURI Final Report No. 343, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final‐reports/343, 10.18408/ahuri5125801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milward, H.B. & Provan, K.G. (2000) Governing the hollow state. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10, 359–380. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, J.E. (2012) Keeping the lights on: how government funding concerns drive the advocacy agendas of nonprofit homeless service providers. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(4), 841–866. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, K. , Carey, G. , Weier, M. , Barraket, J. & Flatau, P. (2020) Pulse of the for purpose sector final report: wave one. Sydney: Centre for Social Impact. Available at: https://www.csi.edu.au/research/project/pulse‐of‐the‐for‐purpose‐sector/ [Accessed 14 January 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- Newby, J.M. , O’Moore, K. , Tang, S. , Christensen, H. & Faasse, K. (2020) Acute mental health responses during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia. PLoS One, 15(7), e0236562. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L. , O’Donnell, C.A. , Jani, B.D. et al. (2020) Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: prospective cohort study using UK Biobank. BMC Medicine, 18, 160. 10.1186/s12916-020-01640-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, D. & Gaebler, T. (1992) Reinventing government: how the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming government. New York, NY: Plume. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia (2020) Shelter in the storm – COVID‐19 and homelessness. Interim report of the inquiry into homelessness in Australia, House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs. Available at: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Social_Policy_and_Legal_Affairs/HomelessnessinAustralia/Interim_Report [Accessed 15 January 2021].

- Parsell, C. , Clarke, A. & Kuskoff, E. (2020) Understanding responses to homelessness during COVID‐19: an examination of Australia. Housing Studies, 9, 1–14. 10.1080/02673037.2020.1829564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfitzner, N. , Fitz‐Gibbon, K. & True, J. (2020) Responding to the ‘shadow pandemic’: practitioner views on the nature of and responses to violence against women in Victoria, Australia during the COVID‐19 restrictions. Victoria: Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Monash University. Available at: https://bridges.monash.edu/articles/Responding_to_the_shadow_pandemic_practitioner_views_on_the_nature_of_and_responses_to_violence_against_women_in_Victoria_Australia_during_the_COVID‐19_restrictions/12433517 [Accessed 20 August 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B. , Gray, M. & Biddle, N. (2020) COVID‐19 JobKeeper and JobSeeker impacts on poverty and housing stress under current and alternative economic and policy scenarios. Canberra: Centre for Social Research and Methods, Australian National University. Available at: https://csrm.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications/covid‐19‐jobkeeper‐and‐jobseeker‐impacts‐poverty‐and‐housing‐stress‐under [Accessed 3 September 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. (2020) Responding to migrant workers: the case of Australia. In: Georgeou, N. & Hawksley, C. (Eds.) State responses to COVID‐19: a global snapshot at 1 June 2020. pp. 12–13, Sydney: Western Sydney University. 10.26183/5ed5a2079cabd [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, M. , Hope, H. , Hatch, S. , Hotopf, M. , John, A. , Kontopantelis, E. et al. (2020) Mental health before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime Minister of Australia (2020) Media release, Prime Minster, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Women, Assistant Minister for Health, Minister for Families and Social Services. Available at: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/11‐billion‐support‐more‐mental‐health‐medicare‐and‐domestic‐violence‐services‐0

- Rhodes, R. (1996) The new governance: governing without government. Political Studies, 44(4), 652–667. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, A. (2020) Australia industry (ANZSIC) report Q8700: community services in Australia. Melbourne: IbisWorld. Available at: https://my.ibisworld.com/au/en/industry/q8700/about [Accessed 13 January 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- Sher, L. (2020) The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(10), 707–712. 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.R. & Lipsky, M. (1993) Nonprofits for hire: the welfare state in the age of contracting. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spies‐Butcher, B. (2020) The temporary welfare state: the political economy of JobKeeper, JobSeeker and ‘snap back’. Journal of Australian Political Economy, 85, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, K. , Bhullar, N. , Durkin, J. , Gvamfi, N. & Jackson, D. (2020) Family violence and COVID‐19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 549–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rheenen, T.E. , Meyer, D. , Neill, E. , Phillipou, A. , Tan, E.J. , Toh, W.L. et al. (2020) Mental health status of individuals with a mood‐disorder during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia: initial results from the COLLATE project. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L. , Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. (2020) Are we all in this together? Longitudinal assessment of cumulative adversities by socioeconomic position in the first 3 weeks of lockdown in the UK. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74, 683–688. 10.1136/jech-2020-214475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.R. (2000) Alternative models of government‐nonprofit sector relations: theoretical and international perspectives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 149–172. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.