Abstract

Objective

To synthesize evidence on the prevalence of mental disorders in adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities and examine sources of heterogeneity between studies.

Method

Electronic databases and relevant reference lists were searched to identify surveys published from January 1966 to October 2019 that reported on the prevalence of mental disorders in unselected populations of detained adolescents. Data on the prevalence of a range of mental disorders (psychotic illnesses, major depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], conduct disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) along with predetermined study characteristics were extracted from the eligible studies. Analyses were reported separately for male and female adolescents, and findings were synthesized using random-effects models. Potential sources of heterogeneity were examined by meta-regression and subgroup analyses.

Results

Forty-seven studies from 19 countries comprising 28,033 male and 4,754 female adolescents were identified. The mean age of adolescents assessed was 16 years (range, 10–19 years). In male adolescents, 2.7% (95% CI 2.0%–3.4%) had a diagnosis of psychotic illness; 10.1% (95% CI 8.1%–12.2%) major depression; 17.3% (95% CI 13.9%–20.7%) ADHD; 61.7% (95% CI 55.4%–67.9%) conduct disorder; and 8.6% (95% CI 6.4%–10.7%) PTSD. In female adolescents, 2.9% (95% CI 2.4%–3.5%) had a psychotic illness; 25.8% (95% CI 20.3%–31.3%) major depression; 17.5% (95% CI 12.1%–22.9%) ADHD; 59.0% (95% CI 44.9%–73.1%) conduct disorder; and 18.2% (95% CI 13.1%–23.2%) PTSD. Meta-regression found higher prevalences of ADHD and conduct disorder in investigations published after 2006. Female adolescents had higher prevalences of major depression and PTSD than male adolescents.

Conclusion

Consideration should be given to reviewing whether health care services in juvenile detention can address these levels of psychiatric morbidity.

Key words: criminal justice, detention, mental disorders, PTSD, systematic review

Adolescents account for approximately 5% of the custodial population in Western countries, and on any given day in the United States, 53,000 young people are detained in various correctional facilities.1 Psychiatric disorders are known to be prevalent in juvenile offenders.2 Furthermore, a number of studies indicate that psychiatric disorders in this population are linked to a wide range of negative outcomes, including elevated risk of repeat offenses,3,4 poor prognosis of mental health problems, high rates of substance misuse,5,6 increased likelihood to experience or perpetrate violence in intimate relationships, and psychosocial difficulties in adulthood.7

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis synthesized evidence up to 2006 on the prevalence of mental disorders in detained adolescents. The findings highlighted considerable mental health needs.8 Since then, a significant body of new primary research has been published. However, recent systematic reviews have been limited by their scope (eg, by including only English-language reports or not searching the gray literature), a lack of quantitative methods (including heterogeneity analyses), and the use of inconsistent time frames for psychiatric diagnoses (eg, in past month, past year, and lifetime).9, 10, 11 This article presents an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental disorders in detained adolescents, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),12 which has become increasingly researched in this population over the last decade. The findings should inform service provision, planning, and future research.

Method

Protocol and Registration

We conducted this systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses13 and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (see Table S1, available online).14 The study protocol was also registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42019117111).

Search Strategy

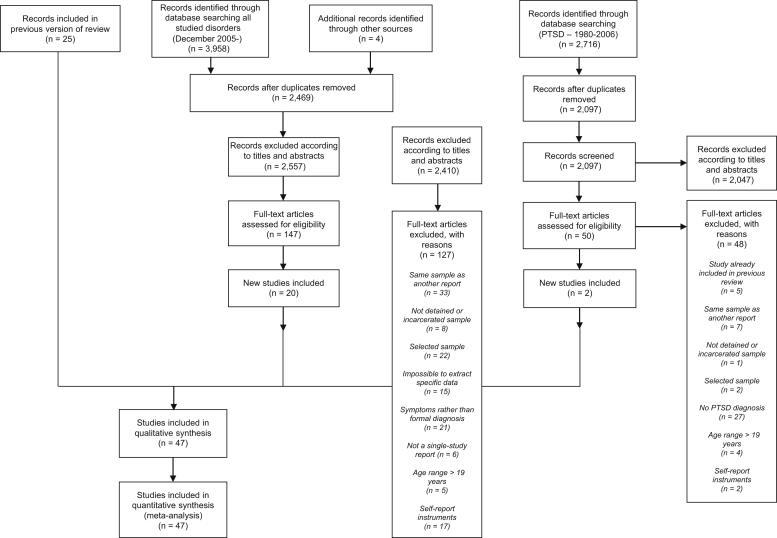

We identified studies published between January 1966 and October 2019 reporting the prevalence of mental disorders in adolescents aged between 10 and 19 years in juvenile detention and correctional facilities. For the period January 1966 to May 2006, the methods were described in a previous review conducted by two of the authors (S.F. and N.L.).8 For this update, we searched the following electronic databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, Medline, US National Criminal Justice Reference System Abstract Database, Global Health, and Google Scholar. Our search strategy featured terms related to adolescents (juvenile∗, adol∗, young∗, youth∗, boy∗, or girl∗) and custody (prison∗, jail∗, incarcerat∗, custod∗, imprison∗, or detain∗), which was identical to the previous review. For psychotic illnesses, major depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and conduct disorder, new search dates ranged from December 2005 to October 2019. However, for PTSD, searches began in January 1980 to coincide with the addition of this disorder to DSM-III.15 Reference lists were hand-searched. No language restriction was set, and non-English surveys were translated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram Detailing the Search Strategy for the Updated Systematic Review (1966–2019)

Note:PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Study Eligibility

We included studies reporting diagnoses of psychotic illnesses, major depression, ADHD, conduct disorder, and PTSD among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities based on clinical examination or interviews conducted with semistructured diagnostic instruments.16 We defined adolescence from the age of 10 to 19 years,17 comparable with the previous review and consistent with research.18 We excluded studies that did not report the prevalence rates of mental disorders separately for male and female adolescents (with the exception of samples including <10% girls), surveys featuring enriched or selected samples of juveniles in custody, and studies that employed exclusively self-report instruments to diagnose individuals (but did include the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children [DISC], as it was typically administered in a semistructured way). Furthermore, included studies reported current prevalence of psychotic illnesses, major depression, ADHD, and PTSD or lifetime prevalence of conduct disorder that adhered to international classifications (ICD and DSM). Thus, one study19 was partially excluded because the prevalences of psychotic illnesses, major depression, and ADHD were reported for the past year rather than the past 6 months. Another reason to include PTSD was correspondence from the original review that recommended its inclusion to expand the clinical scope.20 For psychosis, we excluded one small study21 (n = 173) owing to being an outlier (11.0%).

Data Extraction

One reviewer (G.B.) extracted data from the newly identified studies according to the protocol used in the previous review. In the case of any uncertainty in data extraction, R.Y. and S.F. were consulted. Gender-specific information was collected in regard to prespecified characteristics: geographic location, year of interview, sampling method (consecutive admissions, total population, random, stratified random, or some combination thereof), participation rate, number of interviewed adolescents, diagnostic instrument and criteria (ICD or DSM), type of interviewer (psychiatrist versus other), proportion of individuals diagnosed with each disorder, mean age and age range, mean duration of incarceration at the interview, and proportion with violent offenses.8 Authors of primary studies were contacted when further information was required (Table 1).

Table 1.

Extracted Information From Included Samples, 1966–2019

| Study | Country | Population | Type of custody | Sampling strategy | Proportion not consenting | Total number interviewed | Instrument | Diagnostic criteria | Diagnoses reported | Mean age (Years) | Age range (Years) | Interviewer | Time detained before interview | Proportion committed violent offenses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolton, 197652 | USA | Juvenile detention center | Not further specified | Stratified random | Not provided | 502 boys 149 girls |

Semistructured interview | DSM-II | PI | 16 | 16–17 | Layperson | 4 days | Not provided |

| Chiles et al., 198053 | USA | Juvenile detention center | Correctional | Consecutive (psychotic individuals excluded) | 0% | 94 boys 26 girls |

Clinical | Research criteria of depression | MD | Not provided | 13–15 | Nonpsychiatrist | Up to 2 days | Not provided |

| Kashani et al., 198060 | USA | Detention center | Evaluation and detention | Consecutive | Not provided | 71 boys 29 girls |

Clinical | DSM-III | MD | 15 | 11–17 | Psychiatrist | Mean 7 days | 6% |

| Hollander and Turner, 198559 | USA | Convicted juvenile delinquents | Correctional | Consecutive | 8% | 185 boys | Clinical | DSM-III | PI ADHD |

15 | 12–18 | Staff psychologist and psychiatrist | Not provided | 38% |

| Duclos et al., 199857 | USA | Detention center | Not further specified | Consecutive | 25% | 86 boys 64 girls |

DISC-2.3 | DSM-III-R | MD ADHD CD PTSD |

15 | 12–18 | Nonpsychiatrist | Not provided | Not provided |

| Shelton, 199868 | USA | Detention facilities | Committal and detention facilities | Complete sample | 8% | 252 boys 60 girls |

DISC | DSM-III | PI | 16 | 12–18 | Nonpsychiatrist | Not provided | Not provided |

| Ulzen et al., 199870 | Canada | Detainees | Secure custodial facilities | Not provided | 7% | 38 boys 11 girls |

DICA-R | DSM-III-R | MD ADHD CD PTSD |

15 | 13–17 | Research assistant | Not provided | Not provided |

| Atkins et al., 199951 | USA | Central detention facility | Not further specified | Simple random | 17% | 71 boys 4 girls |

DISC-2.3 | DSM-III-R | ADHD CD |

15 | 13–17 | Social workers, nurses, medical students | Up to 6 months | Not provided |

| Lader et al., 200062 | UK | Detainees | Local prison secure juvenile facility (Young Offender’s Institution) | Stratified random | 2% | 314 detainee and 169 sentenced boys 107 detained/sentenced girls |

SCAN Clinical |

DSM-IV ICD-10 (MD) |

PI MD Mania BP |

Not provided | 16–20 | Psychiatrist | Modal categories 0–2 months, 6–11 months, and 0–2 months | 19% |

| Nicol et al., 200064 | UK | Detainees | Secure juvenile facility (Young Offender’s Institution) | Stratified random | Not provided | 51 juveniles (estimate >90% boys) | K-SADS-E | DSM-III-R | PI MD |

Not provided | 13–17 | Psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist | Not provided | 35% |

| Pliszka et al., 200066 | USA | Juvenile detention center | Not further specified | Consecutive | 0% | 45 boys 5 girls |

DISC-2.3 | DSM-III-R | MD ADHD CD Mania BP |

15 | 11–17 | Nonpsychiatrist | Up to 4 days | Not provided |

| Robertson and Husain, 200128 | USA | Detention centers | Secure detention | Simple random | Not provided | 168 boys 79 girls |

APS JDI |

DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD CD Mania |

15 | 11–18 | Mental health worker (nonpsychiatrist) | Mean 10.2 days | 17% boys, 18% girls (self-report) |

| Dimond and Misch, 200255 | UK | Remand detainees | Secure juvenile facility (Young Offender’s Institution) | Consecutive | 5% | 19 boys | K-SADS-P | DSM-IV | PI MD CD BP |

Not provided | 15–16 | Psychiatrist | Not provided | 42% |

| Oliván Gonzalvo, 200265 | Spain | Juvenile detention center | Correctional | Consecutive | 0% | 35 girls | Clinical | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD |

15 | 14–17 | Psychiatrist | Up to a few days | Not provided |

| Ruchkin et al., 200267 | Russia | Juvenile detention center | Correctional | Complete sample | 2% | 370 boys | K-SADS-PL | DSM-IV | MD ADHD CD |

16 | 14–19 | Psychiatrist | Not provided | 49% |

| Teplin et al., 200269 | USA | Detainees in correctional facilities | Pretrial detention center | Stratified random | 4% | 1,172 boys 657 girls |

DISC-2.3 | DSM-III-R | PI MD ADHD CD Mania |

15 | 10–18 | Trained interviewer (Master’s in psychology or associated field) | Up to 2 days | Not provided |

| Waite and Neff, 200272 | USA | Juvenile detention center | Not further specified | Consecutive | 0% | 9,629 boys 1,190 girls |

Clinical | DSM-IV | PI ADHD CD |

16 | 11–18 | Clinical psychologist | Up to a few days | 18% (boys), 19% (girls) |

| Wasserman et al., 200273 | USA | Reception for juvenile delinquents | Assessment before correctional placement | Simple random | 3% | 292 boys | Voice DISC-IV | DSM-IV | MD ADHD CD Mania PTSD |

17 | Not provided | Layperson | Mean 18.7 days | 36% |

| Gosden et al., 200358 | Denmark | Detainees | Prison and secure social services facility | Consecutive | 21% | 100 boys | SCAN |

ICD-10 DSM-IV (ADHD) |

PI MD ADHD CD |

17 | 15–17 | Psychiatrist | Mean 11 days | 86% |

| Abram et al., 200412 | USA | Detainees in correctional facilities | Short-term detention | Stratified random | 3% | 532 boys 366 girls |

DISC-IV | DSM-IV | PTSD | 15 | 10–18 | Trained interviewer (Master’s in psychology or associated field) | Up to 2 days | Not provided |

| Dixon et al., 200456 | Australia | Juvenile detention center | For serious girl offenders | Consecutive | 5% | 100 girls | K-SADS-PL | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD CD PTSD |

16 | 13–19 | Clinical psychologist | Not provided | 71% |

| Lederman et al., 200463 | USA | Juvenile detention | Before trial or long-term placement | Consecutive | 27% | 493 girls | DISC | DSM-IV | MD ADHD CD |

15 | 10–17 | Nonpsychiatrist | Up to 5 days | 54% |

| Vreugdenhil et al., 200471 | Netherlands | 6 national detention centers | Not further specified | Consecutive | 21% | 204 boys | DISC-IV (DISC-2.3 for PI) |

DSM-IV DSM-III-R (PI) |

PI ADHD CD |

16 | 12–18 | Nonpsychiatrist | Mean 4 months | 72% |

| Yoshinaga et al., 200448 | Japan | Juvenile Classification Home | Short-term detention | Consecutive | 0% | 40 boys 8 girls |

CAPS | DSM-IV | PTSD | 17 | 14–19 | Psychiatrist | Up to 4 weeks | Not provided |

| Abrantes et al., 200550 | USA | 2 juvenile detention centers | Not further specified | Consecutive | Not provided | 218 boys 34 girls |

PADDI | DSM-IV | PI MD CD Mania PTSD |

16 | 13–18 | Staff (nonpsychiatrist) | Not provided | 27% (self-report) |

| Kuo et al., 200561 | USA | Juvenile detention center | Secure placement | Consecutive | 31% | 36 boys 14 girls |

Voice-DISC | DSM-IV | MD | Not provided | 13–17 | Nonpsychiatrist | Median 4 days | Not provided |

| Chitsabesan et al., 200654 | UK | Detainees | Secure juvenile facility (Young Offender’s Institution) | Stratified random | 7% | 118 boys 33 girls |

SNASA | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD |

16 | 13–18 | Psychiatrist | Mean 4 months | Not provided |

| Hamerlynck et al., 200739 | Netherlands | Detainees | 3 juvenile justice institutions | Complete sample | 7% | 212 girls | K-SADS-P-L | DSM-IV | CD | 16 | 12–19 | Not provided | Up to 1 month | Not provided |

| Colins et al., 200919 | Belgium | Detainees | 3 youth detention centers | Simple random | 15% | 245 boys | DISC-IV | DSM-IV | CD PTSD |

16 | 12–17 | Trained interviewer (researcher and university students) | Between 3 days and 3 weeks | 12% |

| Indig et al., 201141 | Australia | Young people held in custody | 8 juvenile detention centers and 1 juvenile correctional center | Simple random | 5% | 245 boys 39 girls |

K-SADS-P-L | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD CD PTSD |

17 | 13–19 | Trained juvenile justice psychologist | Not provided | Not reported for <19 years |

| Köhler et al., 200943 | Germany | Prisoners on remand or in penal detention | Juvenile prison | Complete sample | 7% | 38 boys | SCID (German version) | DSM-IV | PI MD CD PTSD |

Not provided | <18 | Psychologist | Not provided | 75% (not specific to <19 years) |

| Sørland and Kjelsberg, 200946 | Norway | Prisoners | Not further specified | Complete sample | 5% | 40 boys | K-SADS (Norwegian version) | ICD-10 | MD CD |

18 | 15–19 | Researcher | 60% during first 5 days of custody, 85% during first 18 days (range, 25–240 days) | Not provided |

| Karnik et al., 201042 | USA | Detainees | Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Division of Juvenile Justice | Consecutive | 1% | 650 boys 140 girls |

SCID (PI, MD, PTSD) DICA (ADHD) SIDP-IV (CD) |

DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD CD PTSD |

17 | <16 | Not provided | After 9 months | 36% |

| Gretton and Clift, 201137 | Canada | Incarcerated youth | Provincial youth custody centers | Complete sample | Not provided | 119 boys 54 girls |

DISC-IV | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD CD PTSD |

16 | 13–18 (girls) 12–19 (boys) |

Trained interviewer with advanced degrees in psychology | Not provided | 83% (boys) 74% (girls) |

| Mitchell and Shaw, 201127 | UK | Remand and sentenced boys | Young Offender’s Institution | Simple random | 7% | 115 boys | K-SADS | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD PTSD |

17 | 15–17 | Researcher with significant level of clinical experience | 24 hours minimum | 53% |

| Ghanizadeh et al., 201236 | Iran | Incarcerated boys | Prison | Not provided | 0% | 100 boys | K-SADS (Farsi version) | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD CD PTSD |

17 | 12–19 | Researcher | Not provided | 83% |

| Harzke et al., 201240 | USA | Youth entrants | Youth commission facilities | Complete sample | Not provided | 10,469 boys 1,134 girls |

Guided interview structure based on DSM-IV | DSM-IV | PI MD ADHD CD |

Not provided | <19 | Psychiatrists,clinical psychologists, associate psychologists, physicians, physician assistants, nurses | Up to 30 days | Assault (52.1%), sexual offenses (6.6%), murder/manslaughter (3.1%)a |

| Zhou et al., 201247 | China | Detainees | 2 youth detention centers | Complete sample | 9% | 232 boys | K-SADS-PL | DSM-IV | MD DP ADHD CD |

17 | 15–17 | Psychiatrist | Not provided | 73% |

| Lennox et al., 201344 | UK | Adolescent offenders | Young Offender’s Institution | Consecutive | 3% | 219 boys | K-SADS | DSM-IV | PI MD PTSD |

17 | 15–18 | Not provided | 0–26 days | 72% |

| Aida et al., 201434 | Malaysia | Detainees | 5 prisons that are designated centers for juvenile offenders | Simple random | 0% | 105 juveniles (estimate >90% boys) | MINI-KID |

DSM-IV ICD-10 |

PI MD ADHD CD |

17 | 14–17 | Psychiatrist | Not provided | 38% |

| Guebert and Olver, 201438 | Canada | Adolescents adjudicated under Youth Criminal Justice Act or former Young Offenders Act) | Not further specified | Not provided | Not provided | 109 boys 77 girls |

Diagnostic interview | DSM-IV or DSM-IV-TR | MD ADHD CD |

16 | Not provided | Pediatric psychiatrist, registered (usually doctoral level) psychologist | Not provided | 83% (boys), 74% (girls) |

| Aebi et al., 201533 | Austria | Male juvenile detainees | County jail | Consecutive | 3% | 259 boys | MINI-KID |

DSM-IV ICD-10 |

ADHD PTSD |

17 | 14–19 | Psychiatry resident | Up to 4 days | 8.5% |

| Dória et al., 201535 | Brazil | Incarcerated boys | Socio-education center | Simple random | Not provided | 69 boys | K-SADS-PL (Brazilian version) | DSM-IV | MD ADHD CD |

16 | 12–16 | Trained interviewer | 15–30 days | Not provided |

| Lindblad et al., 201545 | Russia | Incarcerated delinquents | Juvenile correctional center | Consecutive | 2% | 370 boys | K-SADS-PL | DSM-IV | PI ADHD CD PTSD |

16 | 14–19 | Child psychiatrist | Not provided | 49% |

| Aebi et al., 201632 | Switzerland | Detainees | Juvenile detention center | Consecutive | 2% | 158 boys | MINI-KID |

DSM-IV ICD-10 |

ADHD CD PTSD |

17 | 13–19 | Psychiatrist, forensic psychologist | Not provided | 63.9% |

| Kim et al., 201721 | South Korea | Juvenile detainees | Male juvenile detention center | Consecutive | 0% | 173 boys | MINI K-SADS-PL (Korean version) |

DSM-IV ICD-10 |

PI MD ADHD CD PTSD |

18 | 15–19 | Clinical psychologist | Not provided | 60% |

| Schorr et al., 201949 | Brazil | Juvenile offenders in temporary custody | Provisional detention center | Consecutive | 0% | 74 boys | Clinical | DSM-IV | CD | Not provided | 15–17 | Psychiatrist | Not provided | 24% committed homicide offenses |

Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; APS = Adolescent Psychopathology Scale; BP = bipolar disorder; CD = conduct disorder; DICA = Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (R = Revised); DISC = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; JDI = Juvenile Detention Interview; K-SADS = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (P = Present, L = Lifetime, E = Epidemiologic); MD = major depression; MINI = Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (KID = for Children and Adolescents); PADDI = Practical Adolescent Dual Diagnostic Interview; PI = psychotic illnesses; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SCAN = Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I, II and Personality; SIDP = Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality; SNASA = Salford Needs Assessment Schedule for Adolescents.

Percentages do not add up to 100%.

Quality Assessment

Study quality was assessed in the included surveys using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, which appraises sample representativeness and size, participation rate, statistical quality, and ascertainment of diagnosis.22,23 We employed the same version of the checklist used in a recent study of the prevalence of PTSD in prisoners.24 The potential total score ranged from 0 to 6 points. Studies with a score of 0 to 2 points were considered low quality, studies with scores of 3 to 4 points were considered medium quality, and studies with scores of 5 to 6 points were high quality (see Supplement 1 and Table S2, available online).

Data Analysis

A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted to calculate pooled prevalence of each disorder, given that heterogeneity among studies was high.25 We aggregated smaller studies, for which the sample size was <100 individuals. For these small studies, prevalences reported in the text were from the nonaggregated data, whereas the figures were generated using results from the aggregated data. The Poisson distribution was used to obtain 95% confidence intervals when events were rare.26 Two studies27,28 for which the prevalence of psychotic illnesses was zero were imputed according to standard methods (ie, confidence intervals were calculated using “3” as the numerator and the real population size as the denominator).29 We reported the I2 statistic and Cochran's Q to indicate the degree of heterogeneity between studies. In line with guidelines, heterogeneity was considered to be low when I2 ranged from 0 to 40%; moderate, from 30% to 60%; substantial, from 50% to 90%; and considerable, from 75% to 100%.30 We conducted subgroup and meta-regression analyses to explore source of heterogeneity on a range of study characteristics: year of publication (≤2006 versus >2006), gender (male versus female), mean age (both as a continuous and as a dichotomous variable; ≤15 or >15 years), sample size (both as a continuous and as a dichotomous variable; ≤250 versus >250 adolescents), study origin (United States versus elsewhere), instrument (DISC versus other instruments), diagnostic criteria (ICD versus DSM), interviewer (psychiatrist versus nonpsychiatrist), sampling strategy (stratified/nonstratified random versus consecutive/complete) and study quality score (both as a continuous and as a dichotomous variable; high-quality studies versus low- and medium-quality studies)). We first conducted univariate meta-regression, followed by multivariable analysis including factors that reached statistical significance (set at p < .05) in the univariate models. To test group differences, subgroup analyses were conducted on all dichotomous variables. All analyses were performed using STATA statistical software package, version 13.0 using metan and metareg commands.31

Results

We identified 47 studies (46 different samples) from 19 different countries. Through our updated search, we found 22 new surveys.12,19,21,27,32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 We combined them with the 25 surveys identified in the previous review.28,50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 Two studies12,69 were based on the same sample, which provided data for different outcomes. The 47 studies included a total of 32,787 adolescents (28,033 male and 4,754 female [15%]) with mean age of 16 years (range, 10–19 years). Of studies, 18 were from the United States (n = 28,018, [86%])12,28,40,42,50, 51, 52, 53,57,59, 60, 61,63,66,68,69,72,73; six were from the United Kingdom (n = 1,145)27,44,54,55,62,64; three were from Canada (n = 408)37,38,70; two each were from Australia (n = 384),41,56 Brazil (n = 143),35,49 Russia (n = 740),45,67 and the Netherlands (n = 416)39,71; and one each was from Austria (n = 259),33 Belgium (n = 245),19 China (n = 232),47 Denmark (n = 100),58 Germany (n = 38),43 Iran (n = 100),36 Japan (n = 48),48 Malaysia (n = 105),34 Norway (n = 40),46 South Korea (n = 173),21 Spain (n = 35),65 and Switzerland (n = 158).32 These surveys were conducted using a range of sampling strategies, including consecutive recruitment of participants (n = 14,768),21,32,33,42,44,45,48, 49, 50,53,55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61,63,65,66,71,72 stratified random sampling (n = 3,272),12,52,54,62,64,69 simple random sampling (n = 1,432),19,27,28,34,35,41,51,73 and complete sampling (n = 12,980).37,39,40,43,46,47,67,68 Three studies (n = 335) did not report on their sampling method.36,38,70 Response rates were reported in 38 studies,12,19,21,27,32, 33, 34,36,39,41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49,51,53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59,61, 62, 63,65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 and only seven of them (n = 1,317) reported rates ≤75%.19,51,57,58,61,63,71 Interviews were conducted using the following instruments: 12 used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children and Adolescents,12,19,37,51,57,61,63,66,68,69,71,73 and 14 used the Schedule for Affective Disorders for School-Age Children, Present, Lifetime or Epidemiologic Version,21,27,35,36,39,41,44, 45, 46, 47,55,56,64,67 while the other surveys employed the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents,42,70 the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Depression,53 the Adolescent Psychopathology Scale and Juvenile Detention Interview,28 the Practical Adolescent Dual Diagnostic Interview,50 the Salford Needs Assessment Schedule for Adolescents,54 the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents,32, 33, 34 the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I, II and Personality,42,43 the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale from DSM-IV,48 or a semistructured interview.52 Most reported diagnoses were assigned using DSM criteria. However, one study provided ICD-10 diagnoses,46 while others combined both DSM and ICD-10 diagnoses.21,32, 33, 34,58,62 The diagnostic interviews were mostly conducted by psychiatrists,33,34,41,45,47, 48, 49,54,55,58,60,62,65,67 clinical psychologists,21,43,56,72 researchers and research assistants,27,36,46,70 or teams with diverse backgrounds.19,28,32,35,37,38,40,50,51,59,64 Most studies reported the types of offenses, and in accordance with previous research,74 we calculated the proportion of adolescents who committed violent offenses, which ranged from 6.0%60 to 86.0%.58 Figure 2 presents gender-specific prevalence estimates.

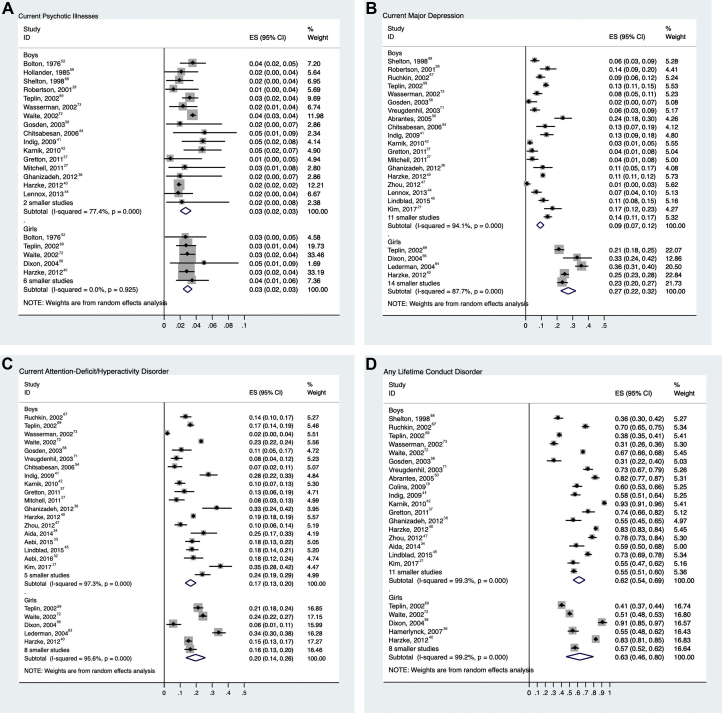

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Specific Mental Disorders Among Incarcerated Male and Female Adolescents

Note:Error bars represent 95% CIs of prevalence. Smaller studies (n < 100) were aggregated. Subtotal is pooled prevalence estimate based on random effects models. ES = prevalence estimate.

Psychotic Illnesses

Prevalence of psychotic illness was reported in 21 studies, comprising 27,801 adolescents.21,27,28,36,37,40, 41, 42, 43, 44,52,54,56,58,59,64,65,68,69,72,73 Overall, 683 of 24,261 male adolescents were diagnosed with a current psychotic disorder (random-effects pooled prevalence 2.7%; 95% CI 2.0%–3.4%) (Figure 2a). There was substantial heterogeneity between surveys (χ217 = 71, p < .001; I2 = 76%). Among female adolescents, 105 of 3,540 individuals were diagnosed with a current psychotic disorder (random-effects pooled prevalence 2.9%; 95% CI 2.4%–3.5%). Heterogeneity between studies was low (χ210 = 5, p = .916; I2 = 0%). We found no associations between study characteristics and prevalence estimates in meta-regression.

Major Depression

We identified 33 studies on major depression in 18,861 adolescents.19,21,27,28,35, 36, 37, 38,40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47,50,53,54,56, 57, 58,60,61,63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71,73 Overall, 1,753 of 15,881 male adolescents (random-effects pooled prevalence 10.1%; 95% CI 8.1%–12.2%) (Figure 2b) and 774 of 2,980 female adolescents (25.8%; 95% CI 20.3%–31.3%) had a current major depression episode. There was considerable heterogeneity among both male (χ229 = 339, p < .001; I2 = 91%) and female (χ217 = 159, p < .001; I2 = 89%) samples. Meta-regression suggested that both gender and study quality were associated with heterogeneity among studies. Male adolescents (β = −.14, SE = .032; p < .001) and studies with higher quality scores (β = −.08, SE = .036; p = .040) reported lower prevalence.

ADHD

We identified 27 articles21,27,33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38,40, 41, 42,45,47,54,56, 57, 58,63,65, 66, 67,69, 70, 71, 72, 73 reporting on ADHD among 28,749 juveniles in custody. Overall, 4,951 of 24,824 male adolescents (random-effects pooled prevalence 17.3%; 95% CI 13.9%–20.7%) (Figure 2c) and 836 of 3,925 female adolescents were diagnosed with current ADHD (17.5%; 95% CI 12.1%–22.9%). Heterogeneity was high for male (χ223 = 824, p < .001; I2 = 97%) and female (χ212 = 179, p < .001; I2 = 93%) samples. Meta-regression found that heterogeneity was partly explained by the publication year (studies published after 2006 reporting a higher prevalence: β = .08, SE = .04; p = .03). In subgroup analyses, the pooled estimate of prevalence of studies published after 2006 was 20.4% (95% CI 17.4%–23.3%) compared with 13.6% (95% CI 8.4%–18.7%) before 2006.

Conduct Disorder

We identified 31 studies on conduct disorder in 28,846 juveniles.19,21,34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43,45, 46, 47,49, 50, 51,55, 56, 57, 58,62,66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73 Overall, 18,042 of 25,184 male adolescents (random-effects pooled prevalence 61.7%; 95% CI 55.4%–67.9%) (Figure 2d) and 2,226 of 3,662 female adolescents (59.0%; 95% CI 44.9%–73.1%) had a diagnosis of any lifetime conduct disorder. Considerable heterogeneity was observed in male (χ228 = 2,664, p < .001; I2 = 99%) and female (χ212 = 1,127, p < .001; I2 = 99%) samples.

In meta-regression, studies published after 2006 (β = .19, SE = .07; p = .006) and studies with older participants (β = .12, SE = .05; p = .013) had higher prevalences. We also found lower prevalences of conduct disorder where the DISC was used (β = −.22, SE = .07; p = .004). None of these variables remained significant in multivariable meta-regression.

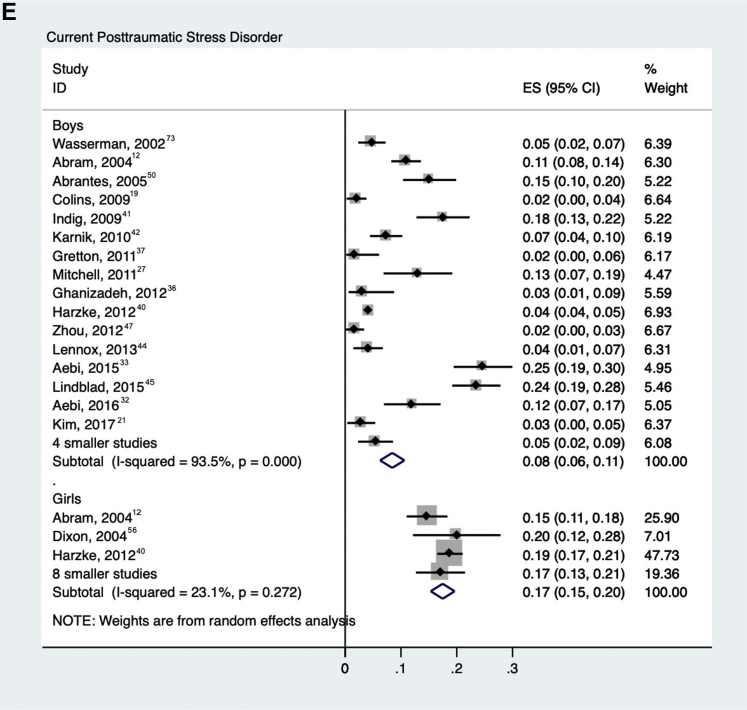

PTSD

Twenty-one studies reported on PTSD12,19,21,27,32,33,36,37,40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45,47,48,50,56,57,70,73 in 16,136 detained adolescents. Among 14,260 male adolescents, 832 (random-effects pooled prevalence 8.6%; 95% CI 6.4%–10.7%) were diagnosed with current PTSD (Figure 2e), and 334 of 1,876 female adolescents (18.2%; 95% CI 13.1%–23.2%) were diagnosed with current PTSD with substantial heterogeneity in male (χ219 = 250, p < .001; I2 = 92%) and female (χ29 = 41, p < .001; I2 = 78%) samples. Gender was the only factor associated with heterogeneity in meta-regression (male adolescents had a lower prevalence: β = −.10, SE = .04; p = .01).

Heterogeneity Analyses

Table 2 presents the results from the meta-regression analyses assessing sample characteristics as possible sources of heterogeneity between studies. Influence analysis, which was performed by omitting one study at a time, reported no effect. Egger's regression test showed publication bias in surveys reporting prevalence of conduct disorder (t = −4.98, p = .03) and PTSD (t = 2.32, p = .02), both in male adolescents (see Figures S1–S5, available online).

Table 2.

Univariate Meta-regression Analyses Examining Possible Sources of Between-Study Heterogeneity Among Adolescents in Juvenile Detention

| Variable | Psychotic Illnesses |

Major Depression |

ADHD |

Conduct Disorder |

PTSD |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | |

| Year of publication: ≤2006 vs >2006 | −.005 | .004 | .22 | −.072 | .037 | .06 | .081 | .035 | .028∗ | .194 | .066 | .005∗ | −.029 | .039 | .47 |

| Gender: male vs female | −.004 | .005 | .42 | −.144 | .032 | < .001∗ | .002 | .040 | .96 | .028 | .079 | .72 | −.102 | .037 | .01∗ |

| Mean age (continuous) | −.003 | .004 | .53 | −.033 | .024 | .18 | .003 | .027 | .91 | .124 | .047 | .01 | −.014 | .027 | .60 |

| Mean age: ≤15 vs >15 years | −.005 | .007 | .46 | −.048 | .073 | .52 | −.022 | .079 | .79 | .182 | .163 | .27 | −.007 | .050 | .89 |

| Study size (continuous) | .000 | .000 | .97 | .000 | .000 | .69 | .000 | .000 | .65 | .000 | .000 | .38 | .000 | .000 | .44 |

| Study size: ≤250 vs >250 adolescents | .005 | .005 | .26 | −.022 | .045 | .63 | .002 | .040 | .96 | −.001 | .082 | .99 | .031 | .038 | .43 |

| Study origin: USA vs elsewhere | .003 | .005 | .52 | .044 | .037 | .25 | −.029 | .039 | .46 | −.094 | .073 | .21 | −.016 | .038 | .67 |

| Instrument: DISC vs other | −.005 | .005 | .33 | −.051 | .040 | .21 | −.057 | .041 | .17 | −.218 | .071 | .004∗ | −.071 | .038 | .07 |

| Diagnostic criteria: ICD vs DSM | .006 | .005 | .20 | .034 | .074 | .64 | .008 | .080 | .92 | −.123 | .122 | .32 | −.050 | .053 | .36 |

| Interviewer: psychiatrist vs nonpsychiatrist | −.006 | .005 | .19 | −.050 | .042 | .25 | −.012 | .041 | .78 | .118 | .073 | .11 | −.004 | .045 | .93 |

| Sampling strategy: stratified/nonstratified vs consecutive/complete | −.003 | .005 | .53 | −.021 | .040 | .60 | −.010 | .042 | .81 | .099 | .080 | .22 | −.030 | .039 | .45 |

| Study quality (continuous) | .003 | .002 | .17 | −.029 | .013 | .04∗ | .007 | .018 | .71 | .048 | .033 | .16 | −.004 | .017 | .81 |

| Study quality: high-quality studies vs low- and medium-quality studies | .007 | .004 | .12 | −.756 | .036 | .04∗ | −.013 | .041 | .76 | .044 | .073 | .55 | −.003 | .039 | .93 |

Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DISC = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05.

Discussion

In this updated systematic review of the prevalence of mental disorders among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities, we identified 47 studies with 32,787 adolescents from 19 different countries. We doubled the number of primary studies compared with a 2008 systematic review.8 Moreover, we broadened our scope of search by adding a new psychiatric diagnosis (PTSD) and more carefully analyzed heterogeneity. The prevalence estimates confirm high levels of mental disorders in detained adolescents. The two commonest treatable disorders in male adolescents were depression (present in about 1 in 10) and ADHD (prevalent in 1 in 5). In female adolescents, approximately one in four had depression, and one in five had PTSD. We found higher prevalences of depression and PTSD in girls in custody compared with boys.

Our review suggests that mental disorders are substantially more common among detained adolescents compared with general population counterparts. Approximately 3% of detained adolescents were diagnosed with a current psychotic illness, a 10-fold increase compared with age-equivalent individuals in the general population.75,76 Higher prevalences of current major depression were found in both male (10%) and female (26%) adolescents compared with the general adolescent population (5% and 11%, respectively).77 About 1 out of 5 detained adolescents had ADHD compared to 1 out of 10 adolescents in the general population.78 Nearly two-thirds of detained adolescents were diagnosed with any lifetime conduct disorder, whereas the estimated lifetime rate of conduct disorder in US adolescents is approximately 10%.79 In addition, adolescents in detention also had higher rates of PTSD than those in the general population, 9% versus 2% in male adolescents and 18% versus 8% in female adolescents.80 These differences underscore the large burden of psychiatric morbidity in detained adolescents.

Apart from higher prevalence than the general population, prevalence estimates in adolescent juvenile detention and correctional facilities were also different from those found in adult prison populations. Psychotic illnesses and major depression appear to be more prevalent in adult prisoners than in adolescent custodial populations.81 However, the prevalence estimates for PTSD are similar in both groups.24 These comparisons suggest that the mental health needs of detained adolescents could be different from those of adult prisoners and may require separate and specifically targeted programs to meet these needs.

The prevalences for ADHD and conduct disorder are higher than in the previous 2008 review. Regarding ADHD, this upward trend may be specific to detained adolescents, as ADHD diagnoses in youths in the general population have not increased when standardized diagnostic methods are used.82 There are two possible explanations for this finding. First, increased prevalence could result from increased awareness of ADHD symptoms among health professionals working in custodial services. That is, the true prevalence of these disorders remains unchanged, but clinicians might be identifying them more accurately. Second, higher prevalence may result from improved identification of adolescents at high risk of reoffending over time. Some individuals with ADHD and conduct disorders who previously might not have been identified may be more likely to be selected for placement in custodial correctional facilities due to improved identification of these disorders.

Another main finding was the higher prevalence of major depression and PTSD in detained female adolescents compared with their male counterparts. These results are consistent with results from adult prison samples24,81,83 as well as the general population, military personnel, and terror attack survivors.84, 85, 86, 87 However, the explanations for this specific to incarcerated youths are not clear. Criminality in female adolescents may be more strongly associated with internalizing mental disorders than crime in male adolescents, or girls might be more vulnerable to adverse and traumatic experiences related to an antisocial lifestyle either within or outside the detention centers.

Finally, the funnel plot results suggest publication bias in male adolescents toward lower prevalence for conduct disorder and toward higher prevalence for PTSD. This could be due to the increased attention that trauma theory has received as a putative causal mechanism for juvenile criminality. In contrast, a highly prevalent descriptive diagnosis such as conduct disorder might be perceived as less useful for etiologic understanding, treatment planning, and primary prevention regarding juvenile delinquency.

One implication of this updated review is that there is no pressing need for conducting more primary prevalence studies, especially in high-income countries, considering that the evidence base is quite large and with most prevalence estimates remaining stable over time. Hence, future research could move toward treatment and interventions in custodial settings and investigate modifiable risk factors for adverse outcomes within custody such as self-harm and violence that may be associated with mental health problems. Effective treatment will likely improve prognosis and reduce suicidality, violence, and reoffending risk.88

Some limitations should be noted. First, owing to discrepancies in how substance use disorder and other mental disorders were classified between studies, it was not possible to reliably examine comorbidity. As adolescents who have comorbid disorders generally present an elevated criminogenic risk, future research on comorbidity is needed.45,69,89 Second, there were insufficient data on the type of facilities (pretrial versus sentenced; short-term versus long-term) where youths were detained. Therefore, we could not explore whether this variable was associated with heterogeneity. Future studies should consider reporting this information on juvenile justice facilities. Third, our analyses were solely based on formal diagnoses of mental disorders according to DSM and ICD, which provide standard ways of communication between mental health professionals. However, we did not report on subthreshold psychiatric symptoms, which future work could examine, as these individuals could benefit from preventive programs. An additional limitation from this review is that the quality appraisal scale was not specifically designed for the purpose of prison prevalence studies, and therefore some of the scoring made assumptions that need further examination (including a lower score for interviews conducted by laypersons using standardized measures versus unstructured clinical interviews conducted by psychiatrists or psychologists, although most of the latter also used standardized tools). Further, there were high levels of between-study heterogeneity. This is expected due to the differences in jurisdictions regarding whom they detain, availability and effectiveness of health care services, and prison environments. Therefore, further work could examine prevalence rates longitudinally in the same individuals to study trends over time. Moreover, we primarily used data from the US general population as a point of comparison for the calculated pooled prevalences because of similar diagnostic instruments, age ranges, and prevalence periods.77, 78, 79, 80 Nevertheless, as worldwide rates differ, including for ADHD between high-income countries, prevalences should be interpreted in relation to national or regional general population prevalences. Finally, it is notable that all included studies were conducted in high- and upper middle–income countries despite the global search. Determining whether new research in other countries is required will need to be balanced by information in this review, local needs, and whether such research can be linked to improved services.

In conclusion, our updated systematic review has reported high rates of treatable mental disorders in detained adolescents. The findings underscore the importance of access to mental health services and effective treatment. Such treatment will likely improve prognosis of this population, almost all of whom will reenter the community, and decrease risk of repeat offending, reducing the substantial social and financial costs related to imprisonment.90

Footnotes

Ms. Beaudry is supported by a Master’s Training Grant 2018–2020 from the Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé (FRQS; 255906). Dr. Fazel is funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (Grant No. 202836/Z/16/Z).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Fazel

Formal analysis: Beaudry, Yu

Funding acquisition: Fazel

Investigation: Beaudry, Yu, Fazel

Methodology: Beaudry, Yu, Langstrom, Fazel

Supervision: Yu

Visualization: Beaudry

Writing – original draft: Beaudry, Yu

Writing – review and editing: Beaudry, Yu, Langstrom, Fazel

ORCID

Gabrielle Beaudry, BA: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7800-8753

Niklas Långstrom, MD, PhD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2686-6799

Seena Fazel, FRCPsych, MD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5383-5365

The authors wish to thank the following researchers who kindly agreed to provide additional data from their studies: Marcel Aebi, PhD, of the University Hospital of Psychiatry, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Zurich (Switzerland), Robert J. W. Clift, PhD, of the Youth Forensic Psychiatric Services and the University of British Columbia, Vancouver (Canada), Devon Indig, PhD, of the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney (Australia), Denis Köhler, PhD, of the University for Applied Sciences Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf (Germany), Mark Olver, PhD, of the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon (Canada), and Coby Vreugdenhil, MD, PhD, of the Pieter Baan Centrum, Almere (Netherlands).

Disclosure: Drs. Yu, Långström, and Fazel and Ms. Beaudry have reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Material

References

- 1.Sawyer W. Youth confinement: The whole pie. Prison Policy Initiative Web site. Published 2018. Available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/youth2019.html. Accessed May 17, 2019.

- 2.Schubert C.A., Mulvey E.P., Glasheen C. Influence of mental health and substance use problems and criminogenic risk on outcomes in serious juvenile offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:925–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McReynolds L.S., Schwalbe C.S., Wasserman G.A. The contribution of psychiatric disorder to juvenile recidivism. Crim Justice Behav. 2010;37:204–216. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plattner B., Steiner H., The S.S. Sex-specific predictors of criminal recidivism in a representative sample of incarcerated youth. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penn J.V., Esposito C.L., Schaeffer L.E., Fritz G.K., Spirito A. Suicide attempts and self-mutilative behavior in a juvenile correctional facility. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:762–769. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046869.56865.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teplin L.A., Welty L.J., Abram K.M., Dulcan M.K., Washburn J.J. Prevalence and persistence of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: A prospective longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1031–1043. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Molen E., Vermeiren R., Krabbendam A., Beekman A., Doreleijers T., Jansen L. Detained adolescent females’ multiple mental health and adjustment problem outcomes in young adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54:950–957. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fazel S., Doll H., Langstrom N. Mental disorders among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities: A systematic review and metaregression analysis of 25 surveys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1010–1019. doi: 10.1097/CHI.ObO13e31817eecf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black E.B., Ranmuthugala G., Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S., Toombs M.R., Nicholson G.C., Kisely S. A systematic review: Identifying the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorder in Australia’s Indigenous populations. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:412–429. doi: 10.1177/0004867415569802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottfried E.D., Christopher S.C. Mental disorders among criminal offenders: A review of the literature. J Correct Health Care. 2017;23:336–346. doi: 10.1177/1078345817716180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young S., Moss D., Sedgwick O., Fridman M., Hodgkins P. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in incarcerated populations. Psychol Med. 2015;45:247–258. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abram K.M., Teplin L.A., Charles D.R., Longworth S.L., McClelland G.M., Dulcan M.K. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:403–410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gersons B.P., Carlier I.V. Post-traumatic stress disorder: The history of a recent concept. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:742–748. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fazel S., Yoon I.A., Hayes A.J. Substance use disorders in prisoners: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction. 2017;112:1725–1739. doi: 10.1111/add.13877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNESCO . UNESCO; Barcelona, Spain: 1985. World Congress of Youth—Final Report. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton G.C., Sawyer S.M., Santelli J.S. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387:2423–2478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colins O., Vermeiren R., Schuyten G., Broekaert E. Psychiatric disorders in property, violent, and versatile offending detained male adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:31–38. doi: 10.1037/a0015337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guchereau M., Jourkiv O., Zametkin A. Mental disorders among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities: Posttraumatic stress disorder is overlooked. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:340. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181949004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J.I., Kim B., Kim B.-N. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders, comorbidity patterns, and repeat offending among male juvenile detainees in South Korea: A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2017;11:6. doi: 10.1186/s13034-017-0143-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mata D.A., Ramos M.A., Bansal N. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314:2373–2383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baranyi G., Cassidy M., Fazel S., Priebe S., Mundt A.P. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in prisoners. Epidemiol Rev. 2018;40:134–145. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxx015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borenstein M., Hedges L.V., Higgins J.P.T., Rothstein H.R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Re Synth Methods. 2010;1:97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilienfeld D.E., Stolley P.D., Lilienfeld A.M. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1994. Foundations of Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell P., Shaw J. Factors affecting the recognition of mental health problems among adolescent offenders in custody. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2011;22:381–394. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson A., Husain J. Mississippi Department of Public Safety; Jackson, MS: 2001. Prevalence of mental illness and substance abuse disorders among incarcerated juvenile offenders in Mississippi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paoli B., Haggard L., Shah G. Utah Department of Health, Office of Public Health Assessment; Salt Lake City, UT: 2002. Confidence intervals in public health. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins J., Altman D., Sterne J. John Wiley & Sons: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 31.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13, 2013. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX

- 32.Aebi M., Barra S., Bessler C., Steinhausen H.-C., Walitza S., Plattner B. Oppositional defiant disorder dimensions and subtypes among detained male adolescent offenders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:729–736. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aebi M., Linhart S., Thun-Hohenstein L., Bessler C., Steinhausen H.-C., Plattner B. Detained male adolescent offender’s emotional, physical and sexual maltreatment profiles and their associations to psychiatric disorders and criminal behaviors. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43:999–1009. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9961-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aida S.A., Aili H.H., Manveen K.S. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among juvenile offenders in Malaysian prisons and association with socio-demographic and personal factors. Int J Prison Health. 2014;10:132–143. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-06-2013-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dória G.M., Antoniuk S.A., Assumpção Junior F.B., Fajardo D.N., Ehlke M.N. Delinquency and association with behavioral disorders and substance abuse. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2015;61:51–57. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.61.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghanizadeh A., Nouri S.Z., Nabi S.S. Psychiatric problems and suicidal behaviour in incarcerated adolescents in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:311–316. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gretton H.M., Clift R.J.W. The mental health needs of incarcerated youth in British Columbia, Canada. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2011;34:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guebert A.F., Olver M.E. An examination of criminogenic needs, mental health concerns, and recidivism in a sample of violent young offenders: Implications for risk, need, and responsivity. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 2014;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamerlynck S.M., Cohen-Kettenis P.T., Vermeiren R., Jansen L.M., Bezemer P.D., Doreleijers T.A. Sexual risk behavior and pregnancy in detained adolescent females: A study in Dutch detention centers. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2007;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harzke A.J., Baillargeon J., Baillargeon G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the Texas juvenile correctional system. J Correct Health Care. 2012;18:143–157. doi: 10.1177/1078345811436000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Indig D., Vecchiato C., Haysom L. Justice Health and Juvenile Justice; Sydney, Australia: 2011. 2009 NSW Young People in Custody Health Survey: Full Report. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karnik N.S., Soller M.V., Redlich A. Prevalence differences of psychiatric disorders among youth after nine months or more of incarceration by race/ethnicity and age. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:237–250. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Köhler D., Heinzen H., Hinrichs G., Huchzermeier C. The prevalence of mental disorders in a German sample of male incarcerated juvenile offenders. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2009;53:211–227. doi: 10.1177/0306624X07312950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lennox C., Bell V., O’Malley K., Shaw J., Dolan M. A prospective cohort study of the changing mental health needs of adolescents in custody. BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindblad F., Isaksson J., Heiskala V., Koposov R., Ruchkin V. Comorbidity and behavior characteristics of Russian male juvenile delinquents with ADHD and conduct disorder. J Atten Disord. 2015;9:392–401. doi: 10.1177/1087054715584052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sørland T.O., Kjelsberg E. Mental health among teenage boys remanded to prisoner [in Norwegian] Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. 2009;129:2472–2475. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.08.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou J., Chen C., Wang X. Psychiatric disorders in adolescent boys in detention: A preliminary prevalence and case-control study in two Chinese provinces. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2012;23:664–675. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshinaga C., Kadomoto I., Otani T., Sasaki T., Kato N. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in incarcerated juvenile delinquents in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:383–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schorr M.T., Reichelt R.R., Alves L.P., Telles B.B., Strapazzon L., Telles L.E. Youth homicide: A study of homicide predictor factors in adolescent offenders in custody in the south of Brazil. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019;41:292–296. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2018-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abrantes A.M., Hoffmann N.G., Anton R. Prevalence of co-occurring disorders among juveniles committed to detention centers. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2005;49:179–193. doi: 10.1177/0306624X04269673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atkins D.L., Pumariega A.J., Rogers K. Mental health and incarcerated youth. I: Prevalence and nature of psychopathology. J Child Fam Stud. 1999;8:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bolton A. Arthur Bolton Associates; Sacramento, CA: 1976. A Study of the Need for and Availability of Mental Health Services for Mentally Disordered Jail Inmates and Juveniles in Detention Facilities. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chiles J.A., Miller M.L., Cox G.B. Depression in an adolescent delinquent population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:1179–1184. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780230097015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chitsabesan P., Kroll L., Bailey S. Mental health needs of young offenders in custody and in the community. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:534–540. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.010116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dimond C., Misch P. Psychiatric morbidity in children remanded to prison custody—a pilot study. J Adolesc. 2002;25:681–689. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dixon A., Howie P., Starling J. Psychopathology in female juvenile offenders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:1150–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duclos C.W., Beals J., Novins D.K., Martin C., Jewett C.S., Manson S.M. Prevalence of common psychiatric disorders among American Indian adolescent detainees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:866–873. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199808000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gosden N.P., Kramp P., Gabrielsen G., Sestoft D. Prevalence of mental disorders among 15–17-year-old male adolescent remand prisoners in Denmark. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:102–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hollander H.E., Turner F.D. Characteristics of incarcerated delinquents: Relationship between development disorders, environmental and family factors, and patterns of offense and recidivism. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:221–226. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kashani J.H., Manning G.W., McKnew D.H., Cytryn L., Simonds J.F., Wooderson P.C. Depression among incarcerated delinquents. Psychiatry Res. 1980;3:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuo E.S., Stoep A.V., Stewart D.G. Using the short mood and feelings questionnaire to detect depression in detained adolescents. Assessment. 2005;12:374–383. doi: 10.1177/1073191105279984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lader D., Singleton N., Meltzer H. Office for National Statistics; London: 2000. Psychiatric morbidity among young offenders in England and Wales. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lederman C.S., Dakof G.A., Larrea M.A., Li H. Characteristics of adolescent females in juvenile detention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2004;27:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicol R., Stretch D., Whitney I. Mental health needs and services for severely troubled and troubling young people including young offenders in an NHS region. J Adolesc. 2000;23:243–261. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oliván Gonzalvo G. Health and nutritional status of delinquent female adolescents [in Spanish] An Esp Pediatr. 2002;56:116–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pliszka S.R., Sherman J.O., Barrow M.V., Irick S. Affective disorder in juvenile offenders: A preliminary study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:130–132. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ruchkin V.V., Schwab-Stone M., Koposov R., Vermeiren R., Steiner H. Violence exposure, posttraumatic stress, and personality in juvenile delinquents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:322–329. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shelton D. University of Maryland, School of Nursing; Baltimore: 1998. Estimates of Emotional Disorder in Detained and Committed Youth in the Maryland Juvenile Justice System. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teplin L.A., Abram K.M., McClelland G.M., Dulcan M.K., Mericle A.A. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ulzen T.P., Psych D.C., Hamilton H. The nature and characteristics of psychiatric comorbidity in incarcerated adolescents. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:57–63. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vreugdenhil C., Doreleijers T.A.H., Vermeiren R., Wouters L.F.J.M., Van Den Brink W. Psychiatric disorders in a representative sample of incarcerated boys in the Netherlands. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:97–104. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waite D., Neff J.L. Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice; Richmond: 2002. Profiles of Incarcerated Adolescents in Virginia’s Juvenile Correctional Centers: Fiscal Years 1999-2003. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wasserman G.A., McReynolds L.S., Lucas C.P., Fisher P., Santos L. The voice DISC-IV with incarcerated male youths: Prevalence of disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:314–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fazel S., Chang Z., Fanshawe T. Prediction of violent reoffending on release from prison: Derivation and external validation of a scalable tool. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:535–543. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Costello E.J., Egger H., Angold A. 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:972–986. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000172552.41596.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kirkbride J.B., Fearon P., Morgan C. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: Findings from the 3-center AeSOP study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:250–258. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Avenevoli S., Swendsen J., He J.-P., Burstein M., Merikangas K.R. Major depression in the national comorbidity survey–adolescent supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Visser S.N., Danielson M.L., Bitsko R.H. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nock M.K., Kazdin A.E., Hiripi E., Kessler R.C. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2006;36:699–710. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Merikangas K.R., He J.-P., Burstein M. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fazel S., Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33 588 prisoners worldwide: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:364–373. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Polanczyk G.V., Willcutt E.G., Salum G.A., Kieling C., Rohde L.A. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:434–442. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Komarovskaya I.A., Booker Loper A., Warren J., Jackson S. Exploring gender differences in trauma exposure and the emergence of symptoms of PTSD among incarcerated men and women. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2011;22:395–410. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Parker G., Brotchie H. Gender differences in depression. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22:429–436. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.492391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cyranowski J.M., Frank E., Young E., Shear M.K. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: A theoretical model. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luxton D.D., Skopp N.A., Maguen S. Gender differences in depression and PTSD symptoms following combat exposure. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:1027–1033. doi: 10.1002/da.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laufer A., Solomon Z. Gender differences in PTSD in Israeli youth exposed to terror attacks. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24:959–976. doi: 10.1177/0886260508319367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wibbelink C.J., Hoeve M., Stams G.J., Oort F.J. A meta-analysis of the association between mental disorders and juvenile recidivism. Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;33:78–90. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Colins O., Vermeiren R., Vahl P., Markus M., Broekaert E., Doreleijers T. Psychiatric disorder in detained male adolescents as risk factor for serious recidivism. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:44–50. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cuellar A.E., Markowitz S., Libby A.M. Mental health and substance abuse treatment and juvenile crime. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2004;7:59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.