Abstract

COVID-19 is a complex disease with many clinicopathological issues, including respiratory, gastrointestinal, neurological, renal, cutaneous, and coagulative ones; in addition, reactive arthritis has been reported by different authors. Here, we hypothesize that a peripheral microangiopathy involving nerve supply, a viral demyelination, or an immune-mediated irritating antigenic stimulus on synovial sheaths after SARS-CoV-2 infection may all induce a carpal, cubital or tarsal tunnel syndrome of variable entity in genetically predisposed subjects associated with myxoid nerve degeneration.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Carpal tunnel syndrome, Cubital tunnel syndrome, Tarsal tunnel syndrome, Histopathology

Background

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the single-stranded RNA virus causing Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), is able to infect the human cells via Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, present in many tissues including the synovial one [1], [2]. Synovium is a specialized connective tissue, which lines the synovial bursae, the inner surface of synovial joint capsules and the tendon sheaths. More in particular, the synovial membrane is found where the tendon runs under ligaments and through osteofibrous tunnels, such as carpal, cubital or tarsal tunnels; its function is to reduce friction between the tendon and the surrounding structures. During viral infections, synovium may be the direct target of the pathogen attack, as in the case of Ross River virus, the single-stranded RNA virus responsible for the so called “epidemic polyarthritis”, or it can be indirectly involved through immunocomplexes deposition [3], [4]. In COVID-19, this deposition can also occur in vascular walls causing leukocytoclastic vasculitis [5]; moreover, COVID-19-related abnormal immunothrombosis and SARS-CoV-2-induced demyelination have been described [6], [7], [8], [9].

Hypothesis

Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 has been reported by different authors during the ongoing pandemic [10], [11], [12]; all the synovial fluid cultures and polymerase chain reactions proved negative, suggesting that it can be the result of a type III hypersensitivity reaction or of an autoimmune response involving cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 antigens and synoviocytes, quite similar to what happens in seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, the well-known autoimmune disorder primarily affecting the synovial membrane [13]. Since carpal, cubital or tarsal tunnel syndrome is sometimes an accompanying event of rheumatoid arthritis [13], [14], [15], it is likely that a reactive arthritis after COVID-19 with irritation and thickening of the synovial sheaths may lead to a compression of the median, ulnar or tibial nerve inside the respective tunnels, such as to require decompressive surgery. Besides, we also hypothesize that the same pain can be exacerbated, even in absence of synovitis or significant compression, if the nerve is subjected to SARS-CoV-2-induced demyelination or ischemic insult due to peripheral microangiopathy triggered by a COVID-19-related hypercoagulative state. In both these conditions, there is no relevant inflammatory infiltrate, but the nerve anyway undergoes myxoid degeneration, also known as “mucoid” or “mucinous” degeneration, real expression of a nerve injury (Fig. 1 ). In support of this hypothesis, we provide our two-cases experience of concomitant carpal and cubital syndrome after SARS-CoV-2 infection in the non-dominant limb of as many middle-aged male patients.

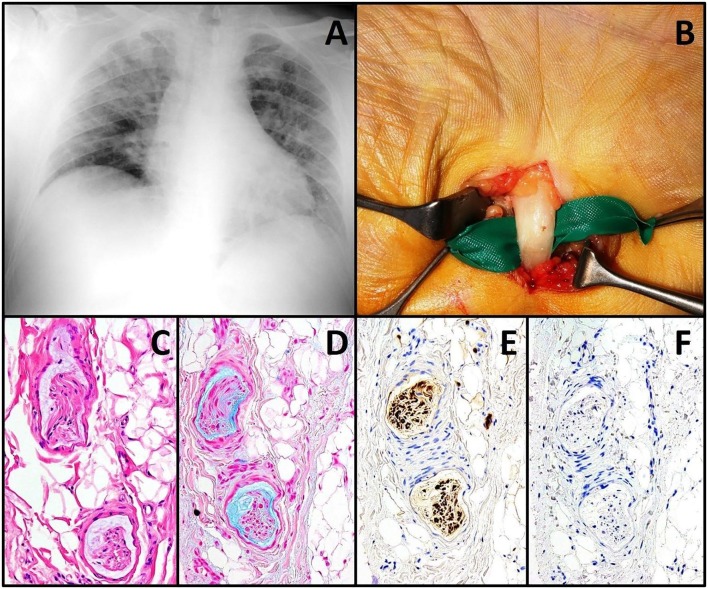

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray showing massive COVID-19 pneumonia in a middle-aged male patient (A), who developed an acute carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome after SARS-CoV-2 infection in the non-dominant limb; macroscopically, a whitish color of the median nerve is well noticeable during decompressive surgery (B). On microscopy, small nerve collaterals are in myxoid degeneration (C, hematoxylin & eosin, 20× objective), well highlighted by histochemistry, which stains mucins in light blue (D, Alcian Blue, 20× objective). Immunohistochemistry for S100 protein labels in brown the nerve collaterals through diaminobenzidine as chromogen (E, clone 4C4.9, Ventana Medical Systems, 20× objective), while immunohistochemistry for SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein does not reveal any positivity in the excised tissue, to suggest an indirect effect of viral infection (F, clone FIPV3-70, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 20× objective).

Case #1

A 47-year-old left-handed man with past medical history of sporadic hyperglycemic peaks suffered from COVID-19, as ascertained by molecular nasopharyngeal swab. The disease began with hyperpyrexia (40 °C), dyspnea plus diarrhea, and progressed towards a clinical picture of septic pneumonia. The patient entered hospital in serious respiratory condition, slipped into a coma and woke up 35 days later, intubated with tracheotomy results. He tested positive at molecular swab for all 35 days, after which he was discharged. In the post-COVID-19 period, he developed a LADA (latent autoimmune diabetes in adults) diabetes mellitus and a right carpal and cubital syndrome, as confirmed by electromyography. On January 26, 2021, he was submitted to decompressive surgery; today, he is alive and well.

Case #2

A 51-year-old right-handed man with low level of vitamin D in anamnesis contracted COVID-19, as proved by molecular nasopharyngeal swab. He remained positive at the test for 33 consecutive days. The disease began with fever and dry cough; following the onset of dyspnea, the patient was hospitalized and stayed in hospital for 22 days, 10 of which intubated. After discharge, during the post-COVID-19 period, he developed a left carpal and cubital syndrome, as highlighted by electromyography. On March 30, 2021, he was submitted to decompressive surgery; today, he is alive and well, with only slight paresthesia at the fifth finger.

Conclusion

Tunnel syndromes and related neuropathies appear to be possible sequelae of severe COVID-19, responding favorably to decompressive surgery. More cases are needed in order to convert our working hypothesis into a certain fact, to confirm a middle-aged male predominance, and to understand the real pathogenetic mechanism underlying this association.

Sources of support in the form of grants

None.

Consent statement/ethical approval

Formal consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the present study; sensitive data and images have been entirely anonymized. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Roncati L., Gallo G., Manenti A., Palmieri B. Renin-angiotensin system: the unexpected flaw inside the human immune system revealed by SARS-CoV-2. Med Hypotheses. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokuda S., Tokunaga T., Masumoto J., Sugiyama E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, a SARS-CoV-2 receptor, is upregulated by interleukin 6 through STAT3 signaling in synovial tissues. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(10):1593–1595. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harley D., Sleigh A., Ritchie S. Ross River virus transmission, infection, and disease: a cross-disciplinary review. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(4):909–932. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.909-932.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roncati L., Palmieri B. What about the original antigenic sin of the humans versus SARS-CoV-2? Med Hypotheses. 2020;142 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roncati L., Ligabue G., Fabbiani L., Malagoli C., et al. Type 3 hypersensitivity in COVID-19 vasculitis. Clin Immunol. 2020;217 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roncati L., Ligabue G., Nasillo V., Lusenti B., et al. A proof of evidence supporting abnormal immunothrombosis in severe COVID-19: naked megakaryocyte nuclei increase in the bone marrow and lungs of critically ill patients. Platelets. 2020;31(8):1085–1089. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2020.1810224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roncati L., Manenti A., Manco G., Farinetti A., et al. The COVID-19 arterial thromboembolic complications: from inflammation to immunothrombosis through antiphospholipid autoantibodies. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;72:216–217. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roncati L., Corsi L., Barbolini G. Abnormal immunothrombosis and lupus anticoagulant in a catastrophic COVID-19 recalling Asherson's syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11239-021-02444-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roncati L., Lusenti B., Pellati F., Corsi L. Micronized / ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) as natural neuroprotector against COVID-19 inflammation. Prostagland Other Lipid Mediat. 2021;154 doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2021.106540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saricaoglu E.M., Hasanoglu I., Guner R. The first reactive arthritis case associated with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):192–193. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hønge B.L., Hermansen M.F., Storgaard M. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(3) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-241375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasparotto M., Framba V., Piovella C., Doria A., et al. Post-COVID-19 arthritis: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05550-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbison G.J., Teng C., Martin J.H., Ditunno J.F., Jr. Carpal tunnel syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Phys Med. 1973;52(2):68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balagtas-Balmaseda O.M., Grabois M., Balmaseda P.F., Lidsky M.D. Cubital tunnel syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64(4):163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabois M., Puentes J., Lidsky M. Tarsal tunnel syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1981;62(8):401–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]