Abstract

BACKGROUND

Retrobulbar hemangioblastomas involving the optic apparatus in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) are rare, with only 25 reported cases in the literature.

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the natural history of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas in a large cohort of VHL patients in order to define presentation, progression, and management.

METHODS

Clinical history and imaging of 250 patients with VHL in an ongoing natural history trial and 1774 patients in a neurosurgical protocol were reviewed. The clinical course, magnetic resonance images, treatment, and outcomes were reviewed for all included patients.

RESULTS

A total of 18 patients with retrobulbar hemangioblastoma on surveillance magnetic resonance imaging met the inclusion criteria for this study. Of the 17 for whom clinical information was available, 10 patients presented with symptoms related to the hemangioblastoma, and 7 were asymptomatic. The mean tumor volume was larger for symptomatic (810.6 ± 545.5 mm3) compared to asymptomatic patients (307.6 ± 245.5 mm3; P < .05). A total of 5 of the symptomatic patients were treated surgically and all experienced improvement in their symptoms. All 3 symptomatic patients that did not undergo intervention had continued symptom progression. Long-term serial imaging on asymptomatic patients showed that these tumors can remain radiographically stable and asymptomatic for extended periods of time (101.43 ± 71 mo).

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that retrobulbar hemangioblastomas may remain stable and clinically asymptomatic for long durations. Recent growth and larger tumor volume were associated with symptom occurrence. Surgical treatment of symptomatic retrobulbar hemangioblastomas can be safe and may reverse the associated symptoms.

Keywords: Optic nerve hemangioblastoma, von Hippel-Lindau, Retrobulbar hemangioblastoma

ABBREVIATIONS

- CNS

central nervous system

- HGB

hemangioblastomas

- IM

intramuscular

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau disease

von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) is an autosomal dominant neoplasia syndrome caused by germline mutations of the VHL gene on chromosome 3.1 More than 80% of VHL patients develop central nervous system (CNS) hemangioblastomas (HGB) and more than 90% of them will develop multiple hemangioblastomas.2-4 CNS VHL hemangioblastomas are most commonly found in the cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord,3 with supratentorial lesions seen in less than 2% of patients.3,5 Retinal hemangioblastomas are also found in 25% to 60% of patients.5 Retrobulbar hemangioblastomas, those that are behind the orbit and involving the optic nerve in patients with VHL are exceedingly rare with only 25 reported cases in the literature.6-20 Due to the rarity of these tumors and the limited literature, a consensus on optimal management has not been established.

At our institution we care for a large cohort of VHL patients in a collaborative interdisciplinary effort. Since 1990, the neurosurgery department and the ophthalmology institute have managed 18 VHL patients with retrobulbar optic nerve hemangioblastomas. Of these, 9 patients have been previously published in a case series by Meyerle et al6 in 2008. Here we expand this experience to analyze the natural history of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas. We report on the presentation, progression, and management of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas in patients with VHL. We also present an illustrative case of an optic nerve hemangioblastoma with detailed discussion of the surgical approach and decision making.

METHODS

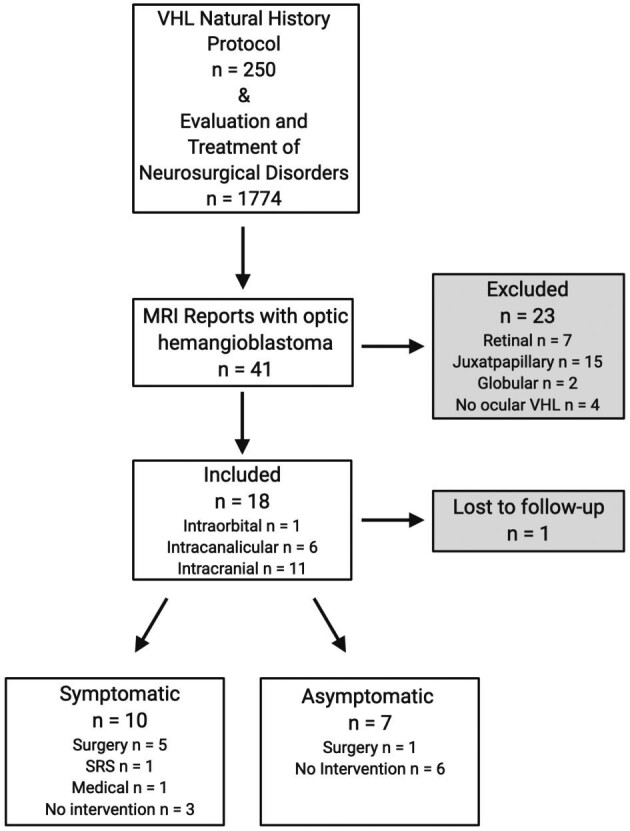

Clinical history and imaging of patients with VHL disease and CNS tumors (n = 250) in an ongoing natural history trial and (n = 1774) an ongoing trial evaluating the treatment of neurosurgical disorders were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of our institution (Figure 1). All patients provided consent to be included in the clinical trials. Among patients with a confirmed VHL diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reports were screened for optic nerve hemangioblastomas. We then identified retrobulbar hemangioblastomas of the optic nerve located in the intraorbital, intracanalicular, and intracranial segments.7 Patients identified as having retinal hemangioblastomas involving the optic disk or with posterior extension were excluded.8 Clinical course were reviewed for included patients using the electronic medical record. Clinical progression was determined as development or progression of tumor related symptoms. Radiographic progression was determined as appreciable tumor growth on MRI. Symptomatic and asymptomatic tumor volumes were compared using 2-tailed t-test with Welch's correction for unequal variance. Statistical analysis was completed on GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California).

FIGURE 1.

Study schema. Retrobulbar optic nerve hemangioblastomas in 18 patients with VHL.

Both clinical trials (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00005902 and NCT00060541) were reviewed and approved by the Combined Neuroscience Institutional Review Board of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

RESULTS

Demographics

Of the 41 patients with supratentorial optic apparatus-associated hemangioblastomas, 18 patients were found to have distinct retrobulbar optic nerve related lesions (Figure 1). Of patients included (n = 18), 1 patient did not have accessible information regarding clinical or radiographic progression; however, this patient was included in the prior report6 and as such we included him in our cohort. The majority of the patients were male (61.1%).

All patients had a history of other CNS hemangioblastomas as well as varying symptomatology (Table 1). Cerebellar tumors were noted in 12 (66.7%), spinal cord tumors were found in 9 (50.0%), brainstem tumors were seen in 3 (16.7%), and nonoptic apparatus supratentorial tumors were seen in 2 (11.1%) patients. The majority of patients (77.7%) had a history of retinal hemangioblastomas. Visceral manifestations such as renal cell carcinoma (61.1%), pheochromocytoma (27.7%), and pancreatic tumors (38.8%) were common.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics (n = 18)

| Patient demographics | |

| Age at diagnosis of retrobulbar HGB | 42 ± 12 |

| mean ± SD | |

| Male | 11 (61.1%) |

| n (%) | |

| Female | 7 (38.9%) |

| n (%) | |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| CNS hemangioblastomas | |

| Cerebellar | 12 (66.7%) |

| n (%) | |

| Spinal cord | 9 (50.0%) |

| n (%) | |

| Brainstem | 3 (16.7%) |

| n (%) | |

| Supratentorial | 3 (16.7%) |

| n (%) | |

| Visceral manifestations | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 11 (61.1%) |

| n (%) | |

| Pheochromocytomas | 5 (27.8%) |

| n (%) | |

| Pancreatic tumors | 7 (38.9%) |

| n (%) | |

| Ocular hemangioblastomas | |

| Retinal | 14 (77.8%) |

| n (%) | |

| Initial presentation | |

| Asymptomatic | 7 (38.9%) |

| Symptomatic | 10 (55.6%) |

| Visual deficits | 9 |

| Neuralgia | 1 |

HGB = hemangioblastoma.

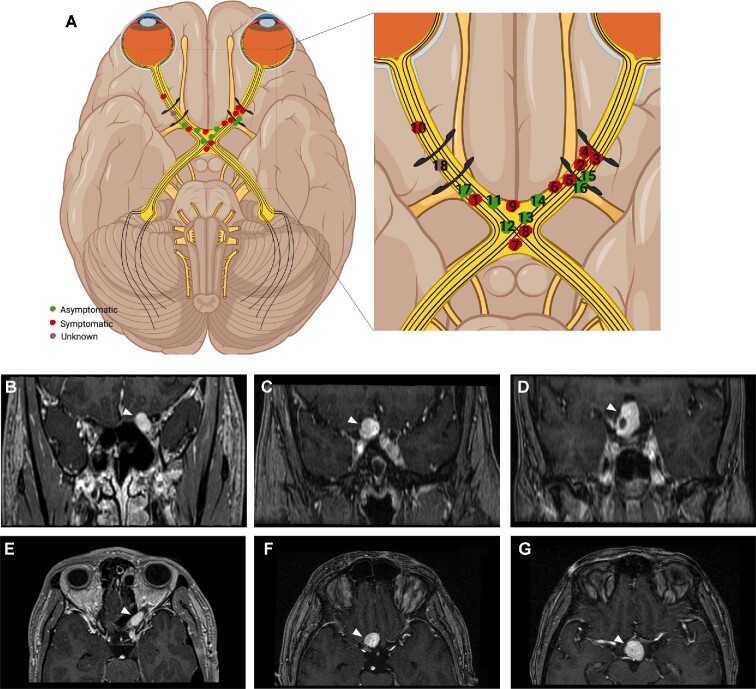

Locations of Retrobulbar Hemangioblastomas

Retrobulbar hemangioblastomas were primarily intracranial (n = 11), and rarely intracanalicular (n = 6) or intraorbital (n = 1) (Figure 2A-2G). The age [mean ± standard deviation (SD)] at diagnosis of the retrobulbar hemangioblastoma was 42 ± 12 yr (16-64 yr). All patients (symptomatic and asymptomatic) were followed with serial MRI for 115 ± 67 mo (mean ± SD); 2 patients did not have MRI available for follow-up (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Retrobulbar hemangioblastomas reported in this study. Schematic showing retrobulbar optic apparatus hemangioblastoma locations for all included patients (n = 18), black curvilinear structures represent the optic canals A. Inset shows the individual tumors labeled as symptomatic (red), asymptomatic (green), and unknown (brown), and are numbered by patient corresponding to Table 2. Representative examples of coronal T1 gadolinium enhanced MR images of hemangioblastomas (white arrowhead) included in this study such as intracanalicular B, intracranial presellar C, and intracranial suprasellar D. Axial T1 gadolinium enhanced MR images of the intracanalicular E, intracranial presellar F, and intracranial suprasellar G patients. Illustration (A) was created using BioRender.com

TABLE 2.

Clinical Course of Included Patients (n = 18)

| Patient | Location | Tumor volume (mm3) | Presentation | Intervention | Imaging | Imaging follow-up (mo) | Clinical progression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R ON; intracranial | 1468.3 | Trigeminal neuralgia and retro-orbital pain | SRS | Diminished size with resolution of cyst | 81.03 | Persistent neuralgia and pain |

| 2 | L ON; intracanalicular | 583 | Diminished visual field and acuity | Surgery: FT craniotomya | Incomplete resection | 64.4 | Improved visual fields, persistent acuity deficits |

| 3 | L ON; intracanalicular | 247.9 | Diminished visual field | Surgery: LSO craniotomy | Complete resection | 36 | Improved visual fields; no progression |

| 4 | L ON; intracanalicular | 845.6 | Diminished acuity | Surgery: enucleation + FT craniotomy + RTX | Incomplete resection; diminished size after RTX | 171.17 | Remained blind after enucleation; no further symptoms |

| 5 | L ON; intracranial | 661 | Sudden monocular blindness | Surgery: TSS | Complete resection | 191.07 | Improved visual fields and acuity; no progression |

| 6 | L ON; intracranial | 1787.9 | Diminished visual fields | Surgery: FT craniotomy + TSS | Complete resection | 91.70 | Persistent visual field deficit, no progression |

| 7 | Optic chiasm; intracranial | 355.9 | Diminished R eye acuity | None (SRS recommended) | Tumor progression | 109.9 | Worsening visual acuity and loss of visual fields |

| 8 | Optic chiasm; intracranial | 1095.2 | Diminished visual fields | IM octreotide | No progression | 219.60 | Stable visual field deficit; no progression |

| 9 | Optic chiasm/infundibulum; intracranial | 251 | Diminished acuity | None | No progression | 128.1 | Worsening acuity |

| 10 | R ON; intraorbital | – | Diminished acuity | None | Not available | – | Worsening acuity |

| 11 | Optic chiasm/infundibulum; intracranial | 374.8 | Asymptomatic | Surgery: FT craniotomya | Incomplete resection | 172.0 | Developed postoperative visual field deficit; no progression |

| 12 | Optic chiasm/infundibulum; intracranial | 138 | Asymptomatic | None | No progression | 193.4 | Stable |

| 13 | Optic chiasm; intracranial | 182.5 | Asymptomatic | None | No progression | 72.8 | Stable |

| 14 | L ON; intracranial | 517 | Asymptomatic | None | No progression | 140.2 | Stable |

| 15 | L ON; intracanalicular | 102.2 | Asymptomatic | None | Growing | 151.9 | Stable |

| 16 | L ON; intracanalicular | 203.1 | Asymptomatic | None | No progression | 37.7 | Stable |

| 17 | R ON; intracranial | 805 | Asymptomatic | None | No progression | 12.6 | Stable |

| 18 | R ON; intracanalicular | – | Not available | Not available | Not available | – | Lost to f/u |

FT = frontal-temporal; IM = intramuscular; L = left; LSO = lateral supraorbital; ON = optic nerve; R = right; RTX = radiation therapy; SRS = stereotactic radiosurgery; TSS = transsphenoidal surgery.

aOutside institution.

Clinical course of all patients included (n = 18). Location of retrobulbar hemangioblastoma in association with optic nerve segment: intraorbital, intracanalicular, or intracranial, numbered to match Figure 2. Symptomatic patients are grouped first, followed by asymptomatic patients, with the last patient being lost to follow-up. Clinical progression is defined as symptomatology after intervention or throughout time followed with MRI.

Clinical Presentation of Retrobulbar Hemangioblastomas

We found that 7 patients were asymptomatic when hemangioblastomas were initially seen on yearly imaging as per protocol for VHL patients, while 10 patients initially presented with progressive symptoms requiring additional imaging and the retrobulbar tumors were identified (Table 2). Of the symptomatic patients (n = 10), 9 patients had decreased visual acuity and/or loss of visual fields, and 1 patient presented with trigeminal neuralgia and retro-orbital pain. Serial MRI on 6 of the asymptomatic patients demonstrated radiographically stable hemangioblastomas for long periods of time (101.43 ± 71 mo) without symptom development. However, 1 of the asymptomatic patients showed radiographic progression on MRI with a 4 mm3 growth and optic pathway edema over a 37-mo period without symptom development. Retrobulbar hemangioblastomas were larger in symptomatic patients (810.6 ± 545.5 mm3) than those without symptoms (307.6 ± 245.5 mm3; P < .05) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Interventions

Interventions were performed on 8 patients (6 treated surgically; 2 treated with nonsurgical interventions). Indications for intervention (Table 2) included tumor progression with presumed risk of symptom development (n = 1; treated at outside institution)9 and worsening symptoms such as deteriorating visual function (n = 7). Of the symptomatic patients that did not receive interventions (3/10), 1 refused stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), 1 was deemed a poor surgical candidate, and the third chose conservative management.

Overall, interventions were performed on 7 of the symptomatic patients (n = 10) and on 1 asymptomatic patient (n = 7) as previously mentioned. Patients that were simply followed without interventions consisted of 3 symptomatic patients previously mentioned and 6 asymptomatic patients.

Nonsurgical Interventions

Of the 2 patients that received nonsurgical interventions, 1 patient had extension of the hemangioblastoma into the right cavernous sinus and underwent a single session of SRS with Gamma Knife (Elekta AB) at an outside institution. The other patient had a chiasmatic hemangioblastoma with involvement of the suprasellar region and was placed on monthly Octreotide intramuscular injections as an off-label indication.10

Surgical Interventions

Surgical intervention was attempted in 6 patients. A total of 1 patient had enucleation in the setting of unsalvageable vision loss and optic atrophy as well as a frontotemporal craniotomy for tumor debulking and adjuvant SRS. A total of 1 patient underwent extended transsphenoidal surgery, 1 underwent a combined transsphenoidal with frontotemporal craniotomy, and 1 underwent a lateral supraorbital craniotomy. The remaining 2 patients had their surgery at outside institutions; detailed information of surgical approach was not available for 1 of these patients. The other patient that was operated at an outside hospital had a pre-emptive frontotemporal craniotomy for an asymptomatic tumor.

Patient Outcomes

Patients that underwent interventions (n = 8), were followed for 94.37 ± 69 mo (mean ± SD). Of the patients who had surgery without enucleation, 4 initially presented with loss in visual acuity and/or partial loss of visual fields and all had postoperative visual improvement that was maintained during follow-up. The asymptomatic patient that underwent prophylactic surgery developed a postoperative visual field deficit with preserved acuity that was not previously present. The patient treated with SRS had persistence of her trigeminal neuralgia and retro-orbital throbbing pain following SRS; however, the tumor diminished with complete resolution of the cyst. The patient who was placed on Octreotide has continued with treatment since June of 2015 and has not had any clinical or radiographic progression. Other than the asymptomatic patient with postoperative visual field deficit, none of the surgically treated patients suffered any complications.

The 3 symptomatic patients that did not undergo any intervention had continued progression of visual deficits until they expired (Table 2). Of note, the nonsurgical patients (n = 5) included in the prior report6 continued to have stable disease with no interventions on long-term follow-up.

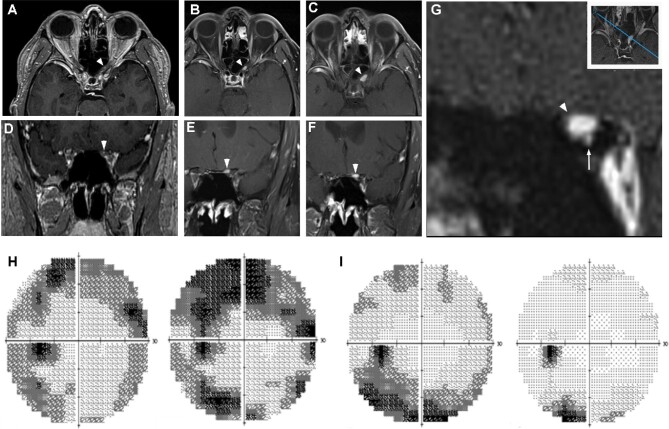

Case Presentation: Intracanalicular Hemangioblastoma

Here, we present the case of a 55-yr-old man (patient 3, Table 2) with an enlarging, symptomatic optic canal hemangioblastoma. Preoperative gadolinium enhanced T1 coronal MRI showed an enhancing 0.53 cm × 0.4 cm lesion on the superior medial quadrant of the intracanalicular left optic nerve (Figure 3A-3G). A review of historical imaging revealed that the hemangioblastoma likely originated from a punctate lesion in the superomedial quadrant of the optic canal, with inferior displacement of the optic nerve and the ophthalmic artery. The patient presented with a mild dimming and variable blurring of vision in the left eye for a few months. Visual acuity tested 20/20, but color vision was decreased (11/16 Ishihara color plates), subtle optic nerve pallor was present on ophthalmoscopy, retinal ganglion cell layer thickness was decreased on optical coherence tomography, and Humphrey visual field testing (30-2 algorithm) showed a mean deviation of −10.44. A total of 2 mo after his initial presentation and prior to undergoing surgery, his visual acuity diminished to 20/32 and visual field mean deviation had decreased to −13.48 (Figure 3H), which improved postoperatively (Figure 3I). A decision was made to approach the hemangioblastoma from an intracranial approach due to the superior location of the hemangioblastoma within the optic canal.

FIGURE 3.

Presentation of a left intracanalicular hemangioblastoma. Serial imaging revealed the significant growth of a left intracanalicular optic nerve hemangioblastoma (white arrowheads) A. A total of 3 yr prior to symptomatic presentation, a punctate, gadolinium contrast enhancing lesion was detectable within the optic canal B, C. A significant growth within the optic canal was detected upon presentation with visual symptoms D-F. High resolution coronal images revealed that the hemangioblastoma was based superiorly within the optic canal G. Custom high-resolution contrast imaging in an oblique plane (inset) revealed that the hemangioblastoma (white arrowhead) was displacing the optic nerve and the ophthalmic artery (white arrow) inferiorly G. Visual fields of left eye (consecutively, left-to-right) 2-mo preoperatively and 2-d preoperatively H, 2-d postoperatively and 1-mo postoperatively I.

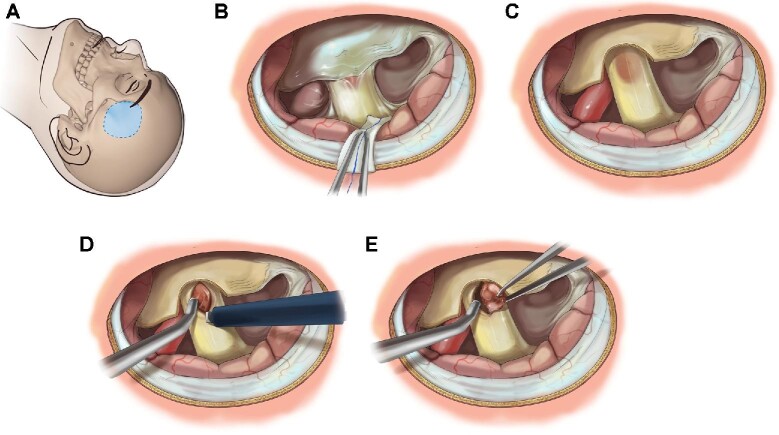

A lateral supraorbital approach11 with visual evoked potential monitoring12 was performed (Figure 4A and Video). The canalicular optic nerve was unroofed by sharp dissection of the falciform ligament (Figure 4B and 4C). All quadrants of the exposed optic nerve were examined for the surface presentation of the hemangioblastoma. Although no surface presentation of the hemangioblastoma was observed, a slight thickening and discoloration of the optic nerve was seen (Figure 4C). Following further bony decompression of the optic nerve proximal to the tumor, a linear incision with a diamond knife was performed parallel to the optic nerve fibers (Figure 4D). Careful deeper dissection allowed the surface of a reddish-brown mass to be identified. All feeding blood vessels were cauterized with microbipolar forceps set at low and divided with micro dissecting scissors, allowing the tumor to be completely mobilized and removed en bloc from within the nerve (Figure 4E). The visual evoked potentials remained stable throughout the case (Supplementary Figure 2). The patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery with subjective improvement in visual fields. At the 1-mo postoperative ophthalmology visit, visual acuity remained 20/32 as was preoperatively, and his visual field testing had improved from a preoperative mean deviation of −13.48 to −2.99.

FIGURE 4.

Lateral supraorbital approach A for resection of intracanalicular hemangioblastoma. Following the initial subfrontal approach, the optic nerve and falciform ligament are identified B. Swelling and discoloration of the nerve is identified. The falciform ligament is removed to expose the optic nerve C. A linear incision parallel to optic nerve fibers is performed to expose hemangioblastoma within D. Microsurgical dissection with spot bipolar cauterization and sharp dissection is utilized to mobilize and remove tumor en bloc E. Artist: Erina He. Medical Arts, Office of Research Services, National Institutes of Health.

DISCUSSION

VHL-associated supratentorial, nonretinal lesions are seen in 2% to 11% of patients with VHL and are primarily found in the temporal lobe, pituitary stalk or in association with the retrobulbar optic nerve.3,13-16 Overall, retrobulbar hemangioblastomas in VHL are exceedingly rare with only 25 reported cases in the literature.6-20 Although rare, these tumors must be considered in VHL patients with diminished visual acuity and/or visual feilds, retro-orbital pain, or diminished color perception. In accordance to management of most VHL-associated hemangioblastomas, surgical resection is reserved for symptomatic or rapidly progressing lesions; however, there is no consensus on the optimal management of these retrobulbar lesions.9,17-28 Here, we present 18 patients with VHL-associated retrobulbar hemangioblastomas and their clinical course as well as their management.

The location and size of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas determine clinical presentation and current management. As optic neuropathy occurs and usually in the earlier stages, the symptomatology may be subtle as presented in our case with changes in color perception and brightness prior to loss of any visual component. However, many of these are asymptomatic upon image presentation.6

Successful treatment of retrobulbar optic nerve hemangioblastomas using intracranial surgery, SRS, and anti-VEGF inhibitors, has been reported previously in the literature.23,28-30 Prompt treatment of cases causing optic neuropathy is essential to preserve vision once visual deficits begin to appear.6,9,19,31 Historically, surgical resection of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas was avoided due to fear of causing vision loss.6,32 Previous studies and our current cohort demonstrate that optic nerve hemangioblastomas may be resected with no postoperative visual loss.6,9,19 These tumors have been found to have an intraneural origin, however remaining discretely separate from the nerve fibers, and displacing the fibers apart rather than infiltrating.6,17,18,33 An incision parallel to the nerve allowed the plane between the hemangioblastoma and nerve fibers to be longitudinally dissected minimizing the risk of injury.

Retrobulbar hemangioblastomas occur in the intraorbital, intracanalicular, intracranial presellar, or intracranial suprasellar segments of the optic nerve.6,27 Surgical approach depends on which corridor the tumor is located in and its relationship to the optic nerve. Those in the sellar vicinity or located on the medial aspect of the optic nerve provide an environment for transsphenoidal or an extended transsphenoidal approach.6,19,21 Lesions located on the superior or lateral surface of the optic nerve favor a transcranial approach.22,24,33,34 In our case, the tumor was intracanalicular but an intracranial approach was used due to the superior location of the tumor in relationship to the optic nerve. Therefore, the relationship of the tumor to the optic nerve should be carefully studied prior to finalizing a surgical approach.

Analyzing our cohort of 18 patients allowed for a better understanding of the natural history of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas. Of the asymptomatic patients (n = 7, 38.9%), 6 were followed with serial imaging, and these tumors appeared to be stable for long periods of time (101 ± 71 mo; mean ± SD). One of the asymptomatic patients did demonstrate tumor growth on imaging but given that they remained asymptomatic, observation was continued. Another patient in this group that had neither clinical nor imaging findings of progression underwent preventive surgery at an outside institution9 and developed a postoperative field deficit. Our asymptomatic cohort suggests that conservative management is a reasonable approach for asymptomatic tumors. VHL patients should be followed with annual ophthalmologic exam as well as with annual neuroaxis imaging. If a retrobulbar hemangioblastoma is found, those patients should be followed with thorough ophthalmologic exams. If patients develop ophthamologic symptoms, further imaging should be obtained to correlate tumor progression with symptomotalogy.

The remainder of our cohort (n = 10, 55.6%) initially presented with worsening clinical symptoms. In our symptomatic patients, half were treated with surgical resection (n = 5), 1 underwent SRS, 1 was placed on a monthly intramuscular Octreotide intramuscular (IM) injections, the remaining 3 symptomatic patients did not receive any form of intervention and were observed. All of the surgically treated symptomatic patients showed improvement in their symptoms with no further progression during the time they were followed (101 ± 71 mo; mean ± SD). The patient treated with SRS continued to suffer from trigeminal neuralgia and retro-orbital pain irrespective of the tumor's decrease in size on imaging. The patient that was placed on IM Octreotide is presently still receiving the monthly treatment and without progression.10 The 3 symptomatic patients that did not receive any form of intervention all had progression of symptoms until their death. The clinical course of our cohort shows that the surgical treatment of symptomatic retrobulbar hemangioblastomas is a prudent choice that may actually reverse symptoms. Additionally, the implementation of intraoperative visual-evoked potentials minimizes risk by providing the surgeon with real-time monitoring of the optic nerve.

Study Limitations

The main limitation is the rarity of this condition and the small sample size preclude the generalizability of this study.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study suggest that retrobulbar hemangioblastomas may remain stable and clinically asymptomatic for long durations. However, recent growth and larger tumor volume was associated with symptom occurrence. Lastly, we found that surgical treatment of symptomatic retrobulbar hemangioblastomas can be considered a safe therapeutic option that may reverse the tumor-associated symptoms.

Funding

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Eye Institute. The study was also supported by the National Institutes of Health Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the National Institutes of Health and generous contributions to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. For a complete list, please visit the Foundation at http://fnih.org/work/education-training-0/medical-research-scholarsprogram.

Disclosures

The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to those who supported the completion of this study. Gloria Oshegbo, Biomedical Translational Research Information System (BTRIS), NIH, and Jessica Mack, Surgical Neurology Branch, NINDS, for assistance with data extraction; Matthew Johnson, BS, and Tanya Lehky, MD, Electromyography Section, NINDS, for the visual-evoked potential monitoring; and Erina He and Alan Hoofring of the Medical Arts Team at the NIH Clinical Center.

Contributor Information

Reinier Alvarez, Neurosurgery Unit for Pituitary and Inheritable Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland; Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Miami, Florida; Surgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland.

Panagiotis Mastorakos, Surgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland; Department of Neurosurgery, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Elizabeth Hogan, Neurosurgery Unit for Pituitary and Inheritable Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland; Department of Neurosurgery, George Washington University, Washington, District of Columbia.

Gretchen Scott, Surgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland.

Russell R Lonser, Department of Neurological Surgery, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio.

Henry E Wiley, Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications, National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

Emily Y Chew, Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications, National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

Prashant Chittiboina, Neurosurgery Unit for Pituitary and Inheritable Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland; Surgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland.

Supplementary Figure 1. Mean symptomatic tumor volume (mm3) on presentation compared to mean asymptomatic tumor volume (mm3) with statistical significance set at P < .05.

Supplementary Figure 2. Visual evoked potentials. Red line is preoperative baseline and black line is postoperative. Monitoring began prior to skin incision and concluded after skin closure.

COMMENT

Hemangioblastomas of cranial nerves are very rare and are typically described in case reports. Fortunately, due to an ongoing natural history study in a large cohort of von Hippel-Lindau disease patients, we now can cite the experience of 18 patients with the rare finding of a retrobulbar optic nerve hemangioblastoma. As would be expected, tumor volume correlated significantly with symptoms in this location. What was unexpected, however, was the favorable outcome experienced in symptomatic patients with microsurgical resection of hemangioblastoma from the retrobulbar optic nerve using intra-operative visual-evoked potential monitoring. The authors are to be commended as it demonstrates how careful surgical approach and technique can improve neurologic outcomes in even the most challenging tumors. Based on the outcomes reported here, neurosurgeons encountering this rare entity can advise surgical intervention for symptomatic patients with confidence that surgery is appropriate, technically feasible and that visual symptoms may improve or at least stabilize. Also, we can advise symptomatic patients that without surgical treatment visual symptoms will likely continue to deteriorate. Finally, we can reassure asymptomatic patients that their retrobulbar optic nerve hemangioblastoma may remain stable for years. Although the patient numbers are small, we rely on information provided in such reports to guide our decisions in such rare diagnoses. The authors are congratulated on their success in helping patients with this debilitating disease and for sharing their experience to help improve the outcome for similar patients.

N. Nicole Moayeri

San Francisco, California

REFERENCES

- 1. Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra Jet al. Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science. 1993;260(5112):1317-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dornbos D, Kim HJ, Butman JA, Lonser RR. Review of the neurological implications of von Hippel-Lindau disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(5):620-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wanebo JE, Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Oldfield EH. The natural history of hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(1 Suppl.):82-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Butman JA, Linehan WM, Lonser RR. Neurologic manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1334-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther Met al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2059-2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyerle CB, Dahr SS, Wetjen NMet al. Clinical course of retrobulbar hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1382-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee AG, Morgan ML, Palau AEBet al. Anatomy of the Optic Nerve and Visual Pathway. Vol 1. San Diego: Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiley HE, Krivosic V, Gaudric Aet al. Management of retinal hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Retina. 2019;39(12):2254-2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raila FA, Zimmerman J, Azordegan P, Fratkin J, Parent AD. Successful surgical removal of an asymptomatic optic nerve hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neuroimaging. 1997;7(1):48-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sizdahkhani S, Feldman MJ, Piazza MGet al. Somatostatin receptor expression on von Hippel-Lindau-associated hemangioblastomas offers novel therapeutic target. Sci Rep. 2017;7(December 2016):40822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hernesniemi J, Ishii K, Niemelä Met al. Lateral supraorbital approach as an alternative to the classical pterional approach. In: New Trends of Surgery for Stroke and Its Perioperative Management. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 2005:17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harding GFA, Bland JDP, Smith VH. Visual evoked potential monitoring of optic nerve function during surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(10):890-895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neumann HP, Eggert HR, Weigel K, Friedburg H, Wiestler OD, Schollmeyer P. Hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. A 10-year study with special reference to von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1989;70(1):24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Filling-Katz MR, Choyke PL, Oldfield Eet al. Central nervous system involvement in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neurology. 1991;41(1):41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lonser RR, Butman JA, Kiringoda R, Song D, Oldfield EH. Pituitary stalk hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease: clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;110(2):350-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peyre M, David P, Van Effenterre Ret al. Natural history of supratentorial hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neurosurgery. 2010;67(3):577-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ginzburg BM, Montanera WJ, Tyndel FJet al. Diagnosis of von Hippel-Lindau disease in a patient with blindness resulting from bilateral optic nerve hemangioblastomas. Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159(2):403-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wirtschafter J, Balcer LJ, Galetta SL, Curtis M, Maguire A, Judy K. von Hippel-Lindau disease manifesting as a chiasmal syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39(4):302-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kouri JG, Chen MY, Watson JC, Oldfield EH. Resection of suprasellar tumors by using a modified transsphenoidal approach. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(6):1028-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fons Martínez MR. An optic nerve tumor in von Hippel-Lindau disease, masquerading as a retinal hemangioma. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2006;81(5):293-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baggenstos M, Chew E, Butman JA, Oldfield EH, Lonser RR. Progressive peritumoral edema defining the optic fibers and resulting in reversible visual loss. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(2):313-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barrett R, Meyer D, Boulos A, Eames F, Torres-Mora J. Optic nerve hemangioblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(11):2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanno H, Osano S, Shinonaga M. VHL-associated optic nerve hemangioblastoma treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2018;5(2):1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Staub B, Livingston A, Chévez-Barrios P, Baskin D. Hemangioblastoma of the optic nerve producing bilateral optic tract edema in a patient with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fard MA, Hassanpoor N, Parsa R. Bilateral optic nerve head angiomas and retrobulbar haemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neuroophthalmology. 2014;38(5):254-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McGrath LA, Mudhar HS, Salvi SM. Optic nerve haemangioblastoma: signs of chronicity. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2018;4(6):370-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Darbari S, Meena RK, Sawarkar D, Doddamani RS. Optic nerve hemangioblastoma: review. World Neurosurg. 2019;128:211-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aiello LP, George DJ, Cahill MTet al. Rapid and durable recovery of visual function in a patient with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome after systemic therapy with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor SU5416. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(9):1745-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Singh AD, Nouri M, Shields CL, Shields JA, Perez N. Treatment of retinal capillary hemangioma. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(10):1799-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krivosic V, Kamami-Levy C, Jacob J, Richard S, Tadayoni R, Gaudric A. Laser photocoagulation for peripheral retinal capillary hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1(1):59-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kerr DJ, Scheithauer BW, Miller GM, Ebersold MJ, McPhee TJ. Hemangioblastoma of the optic nerve: case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;36(3):573-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nerad JA, Kersten RC, Anderson RL. Hemangioblastoma of the optic nerve. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(3):398-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prabhu K, Daniel RT, Chacko G, Chacko AG. Optic nerve haemangioblastoma mimicking a planum sphenoidale meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 2009;23(5):561-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turel MK, Kucharczyk W, Gentili F. Optic nerve hemangioblastomas? A review of visual outcomes. Turk Neurosurg. 2017;27(5):827-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.