Abstract

Background:

Group B streptococcus or streptococcus Agalactia is a gram positive beta hemolytic bacteria which is the main factor in neonatal infections. This study aimed at determining the prevalence of GBS in world and clarifying the rate of this infection in Islamic and non-Islamic countries.

Methods:

We performed a systematic search by using different databases including Medline, Scopus, Science Direct, Psycho-Info ProQuest and Web of Science published up to Feb 2019. We undertook meta-analysis to obtain the pooled estimate of prevalence of GBS colonization in Islamic and non-Islamic countries.

Results:

Among 3324 papers searched, we identified 245 full texts of prevalence of GBS in pregnancy; 131 were included in final analysis. The estimated mean prevalence of maternal GBS colonization was 15.5% (CI:95% (14.2–17)) worldwide; which was 14% (CI:95% (11–16.8)) in Islamic and 16.3% (CI:95% (14.6–18.1)) in non-Islamic countries and was statistically significant. Moreover, with regards to sampling area, prevalence of GBS colonization was 11.1 in vagina and 18.1 in vagina-rectum.

Conclusion:

Frequent washing of perineum based on religious instructions in Islamic countries can diminish the rate of GBS colonization in pregnant women.

Keywords: Group B streptococcus, Vagina, Rectum, Pregnant women

Introduction

Group B streptococcus or streptococcus Agalactia is a gram positive beta hemolytic bacteria which is the main factor in neonatal infections (1). This organism is able to abundantly colonize in genital and digestive tracts of pregnant women and enter amniotic fluid through chorioamniotic membranes (2). In various studies, different numbers of prevalence of this organism in pregnant women have been mentioned, 50%–70% of these women transmit GBS to infants (3). The effect of this bacteria in bringing about undesirable consequences in pregnancy such as pre-term labor, premature rupture of membranes, Chorioamnionitis, and fetal infections has been put forward (4). Furthermore, in recent systematic reviews, the infection in infants is considerably related to the vaginal colonization of mother with GBS during pregnancy (5). GBS can produce infections in infants such as Septicemia, Meningitis, Cellulitis, Conjunctivitis, Pneumonia, Adenitis, Osteomyelitis, Otitis media. Out of these infections, septicemia and meningitis are threatening the lives of the infants more than the others. Although they are put under treatment, they mostly lose their lives (6). Considering the importance of GBS infections and the health of mothers and infants exposed to post-partum infections, screening of pregnant in terms of GBS colonization has been suggested for the sake of treatment in due time and prevention of the bacterial transmission to the infants (7). Some revisions occurred in the protocol of (CDC) in order to make bacterial screening obligatory for all pregnant during 35 to 37 wk of the pregnancy (8).

Screening is carried out on the basis of vaginal secretion culture and that of rectum and in the case of positive culture pregnant, Antibiotic prophylaxis during pregnancy has been suggested (9,1). Variations in the rate of colonization due to difference in geographical regions, social conditions, pregnancy age of the study population, microbiological diagnostic methods, sexual activity, physical status, time and place of sampling and among religious and ethnical groups differ (10–14). Previous systematic review carried out in 2017 has stated that the prevalence of GBS is 18%. The maximum amount is related to Caribbean region with 35% and minimum amount is found in East Asia with 11%. Moreover, this study considers various serotypes in different regions of the world (15). According to the hypothesis of this study based on the possibility of low prevalence of Group B streptococcus in pregnant of Islamic countries due to the religious instructions concerning hygiene after urination and defecation, the outcomes of this study may propose some strategies for preventing GBS infection. Up to now, there has not been any systematic review considering the comparison between Islamic and non-Islamic countries in this respect. Therefore, this study aimed at clarifying the rate of vaginal and rectal colonization of this infection in Islamic countries and comparing it with that of non-Islamic countries.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis study concerning the prevalence of Group B Streptococcus (GBS) in the world and compares the prevalence of it in Islamic and non-Islamic countries, carried out in Iran in 2019.

Search strategy & selection criteria

We have searched papers dealing with prevalence of GBS in rectum and vagina of pregnant throughout the world. The search covers databases such as ScienceDirect, MedLine, Scopus, Web of Science (Web of Knowledge), Psycho-Info-ProQuest in which papers have been published up to Feb of 2019. Unpublished documents (gray literature) and documents presented in conferences have been searched too. We have even consulted with those involved in similar subjects in order to get more information about published and unpublished documents in this regard. Keywords (colonization, vaginal, rectal, pregnant women, pregnancy, prevalence, Group B streptococcus, streptococcal infections, GBS, streptococcus Agalactia) have been used in searching the papers. These terms have been derived from MeSh and EMTree.

The selection of papers

Inclusion criteria: The criteria for selecting papers concentrate on all studies which consider the prevalence of group B streptococcus of every age of pregnancy or delivery. They included those studies in which sampling of rectum and vagina was conducted. No time limitation has been considered.

Exclusion criteria: Those papers which met the following criteria were excluded from our study:

-Those papers which had clearly methodological defects.

-Those papers which had surveyed non-pregnant population or had not declared the prevalence in pregnant separately.

-Those papers surveyed the women with previous illness such as Diabetes or Immunocompromised disease.

-Those papers determined the Streptococcus with a method other than the culture like PCR.

Data extraction and survey of study quality

The papers have been selected in three stages after their extraction from related databases with the above mentioned keywords by an expert in the field. First, the titles and then the abstracts of all the papers were surveyed and those papers which were not compatible with the study aims were extracted. Afterwards full texts of the papers were studied and those which didn’t meet our criteria or were weakly related to our subject were put aside. Selected materials were evaluated by two experts and their different ideas about the materials were referred to the third evaluator. The quality of materials before their extraction and separation was assessed with PRISMA checklist (checklist of all the papers are in the appendix). The necessary extracted data was summarized in Extraction form. They included the author’s names, publication year, the kind of study, country, sample size, pregnancy age, average age of mothers, culture media, various bacterial serotype, sensitivity or antibiotic resistance and sampling place separately recorded. We have used source management software Endnote X5 to organize, and study the topic and abstracts, and even to identify the repeated materials. Furthermore, Islamic and non-Islamic countries were divided into two groups and then analyzed with reference to countries whose names were recorded in the site of Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). F bias risk of all studies was evaluated by an epidemiologist. The quality of the included papers was assessed with the checklist related to studies about the prevalence of JBI.

Statistical Analysis

We have used frequency and percent to show the data, and the heterogeneity among the studies was surveyed with Cochran and I2 statistics which indicate the changes among the studies. We have assumed the rate of I2 less than 0/50 as the presence of homogeneity among the studies. Random effects model was used to combine the results and the analysis of subgroups was conducted on the basis of pregnancy age, the kind of society (Islamic/non-Islamic). Statistical analysis was carried out using CMA v.3.1 software and p-value less than 0.05 was assumed as meaningful level. Moreover, we have surveyed the prevalence of GBS in minor subgroups which covered the survey of prevalence in different continents, antibiotic sensitivity and resistance, and the analysis based on GBS serotypes.

Results

The results of the search and the characteristics of the studies

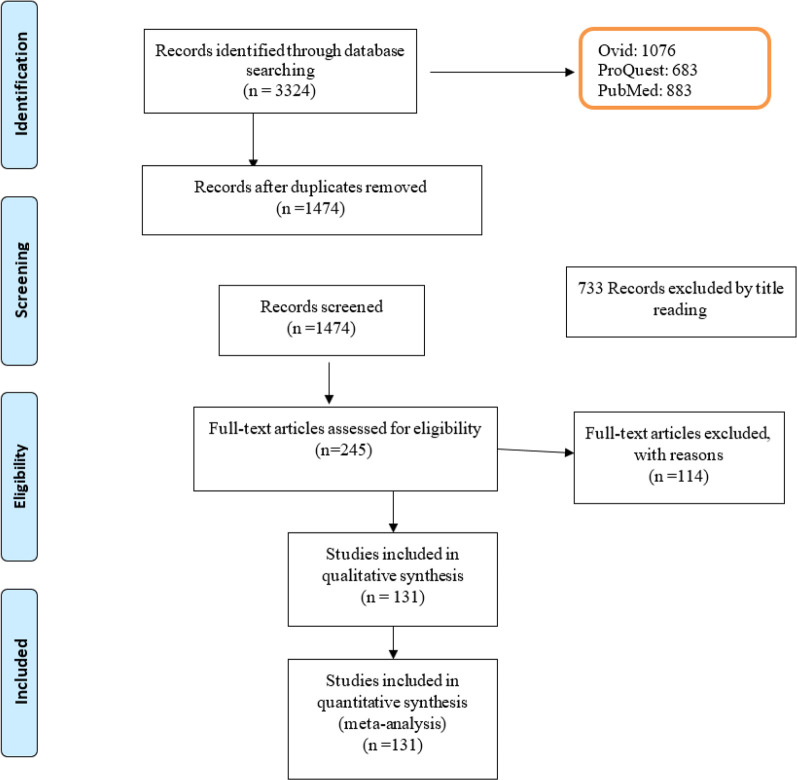

Overall, 3324 papers were identified, 1850 papers due to their repetition, 733 papers after considering their titles, and 496 papers after reviewing their abstract were excluded from our study. After we have surveyed full texts of papers, we excluded 114 papers from our study, therefore, 131 papers were included in our meta-analysis study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

The characteristics of the study

Out of 131 papers in our study, we found 99 papers in which pregnancy age at the time of sampling had been mentioned and three cases of sampling were conducted at delivery, but in one study, pregnancy age was not mentioned. The remaining studies were carried out during the second and third trimester.

We have found 127 studies in which the place of sampling was stated, that is, in 86 cases, the places of sampling were rectum and vagina and in 41 cases it was vagina. Different culture medias have been used in the studies. Among the 131 studies, only 91 studies had referred to the kind of culture media. In 56 cases, the sampling media Todd Hweit, in 17 cases Blood agar, in 6 cases CHROM, in 5 cases LIM Broth, in 3 cases Granada, and in 3 cases Clumbia were used.

Among the included papers, only 22 papers had surveyed different serotypes of GBS separately and 28 papers discussed antibiotic sensitivity.

In some studies, the sensitivity for one type of antibiotic was considered while in some others effects of various antibiotics were discussed. In other words, in 24 studies sensitivity to Penicillin, in 17 studies sensitivity to Ampicillin and Vancomycin, in 16 sensitivity to Erythromycin were surveyed. Moreover, 17 studies had considered antibiotic resistance that is, in 15 studies resistance to Erythromycin, in 14 papers resistance to Clindamycin, in 15 studies resistance to Tetracycline and in 3 studies resistance to Penicillin were discussed.

Meta-Analysis results

About 131 studies were included in the meta-analysis and 115680 individuals were surveyed. The rate of homogeneity was meaningful. (Q=4969.21, df=130, I2=97.5, P<0.001). Considering the results of the meta-analysis, we noticed that the prevalence of GBS in pregnant women of all the studied countries was 15.5%. (15.5%, CI=95% (14.2–17.0))

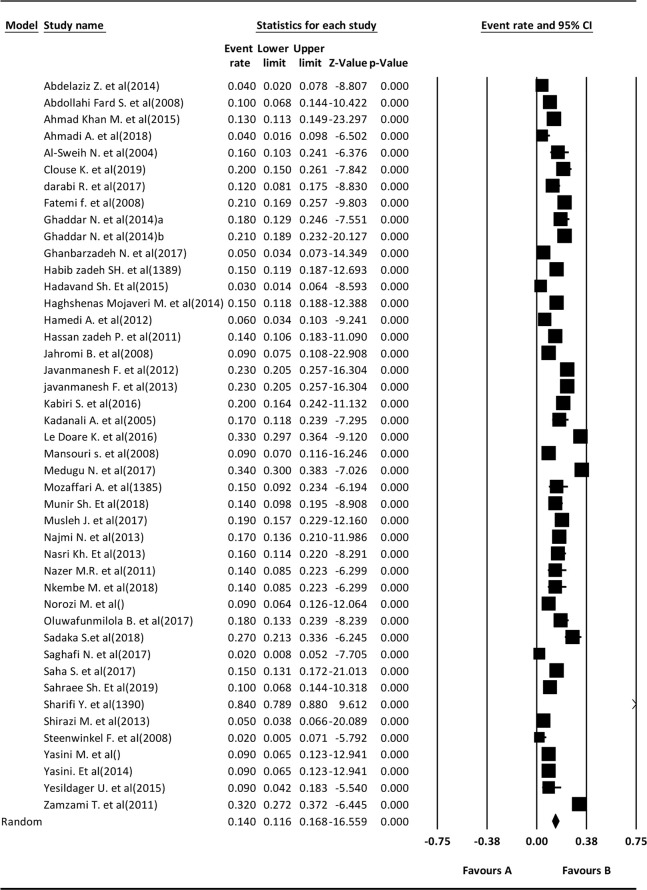

The prevalence of GBS in pregnant women of Islamic and non-Islamic countries

About 44 cases of study had been conducted in countries where Moslem population were living and in the studies of Islamic countries 18359 individuals had been surveyed, so heterogeneity among the studies were meaningful. (Q=1102.17, df=43, I2=96.09). According to the results of the meta-analysis, the prevalence of GBS in pregnant women in Islamic countries was 14% (14%, CI=95%, (11.0–16.8)). In Fig. 2, the prevalence of GBS in pregnant has been illustrated.

Fig. 2:

Prevalence of GBS in pregnants women of Islamic countries

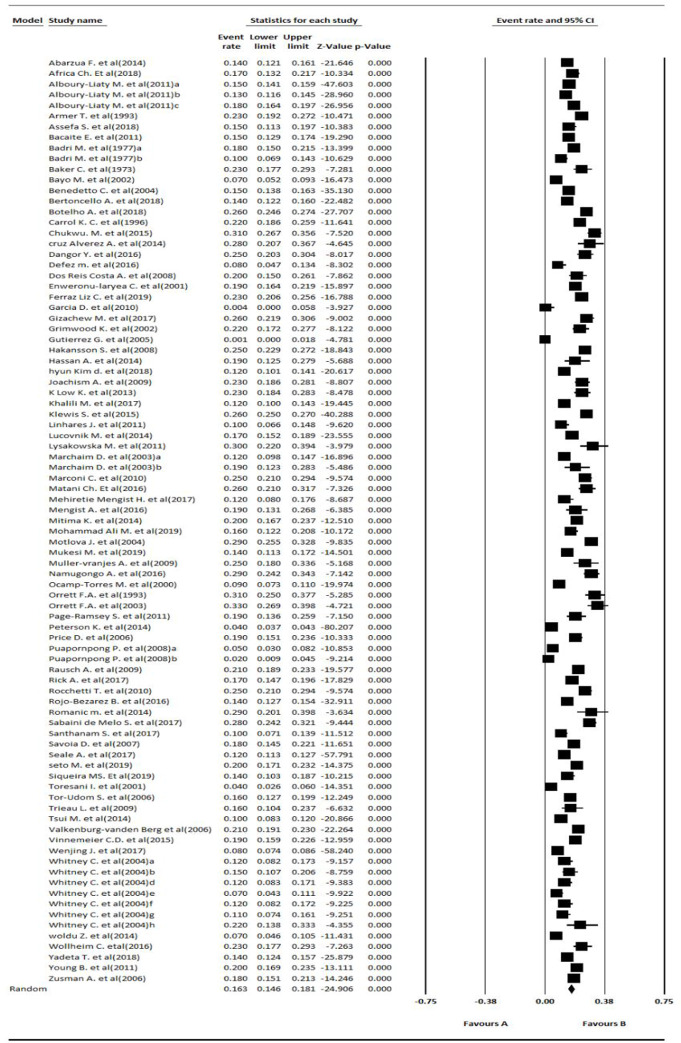

About 87 studies have taken place in countries where non-Muslim population were living. In these studies, 97321 individuals had been considered and the result was that heterogeneity among the studies was meaningful (Q=3834.67, df=86, I2=97.75). According to our meta-analysis, the prevalence of GBS in pregnant women of non-Islamic countries was 16.3% (16.3%, CI=95% (14.6–18.1)). The prevalence of GBS has been illustrated in (Fig. 3). The prevalence of GBS in pregnant of Islamic and non-Islamic countries is 14% and 16.3% respectively. Therefore, according to the ratio test, difference in the case of prevalence of GBS between Islamic and non-Islamic countries was meaningful statistically.

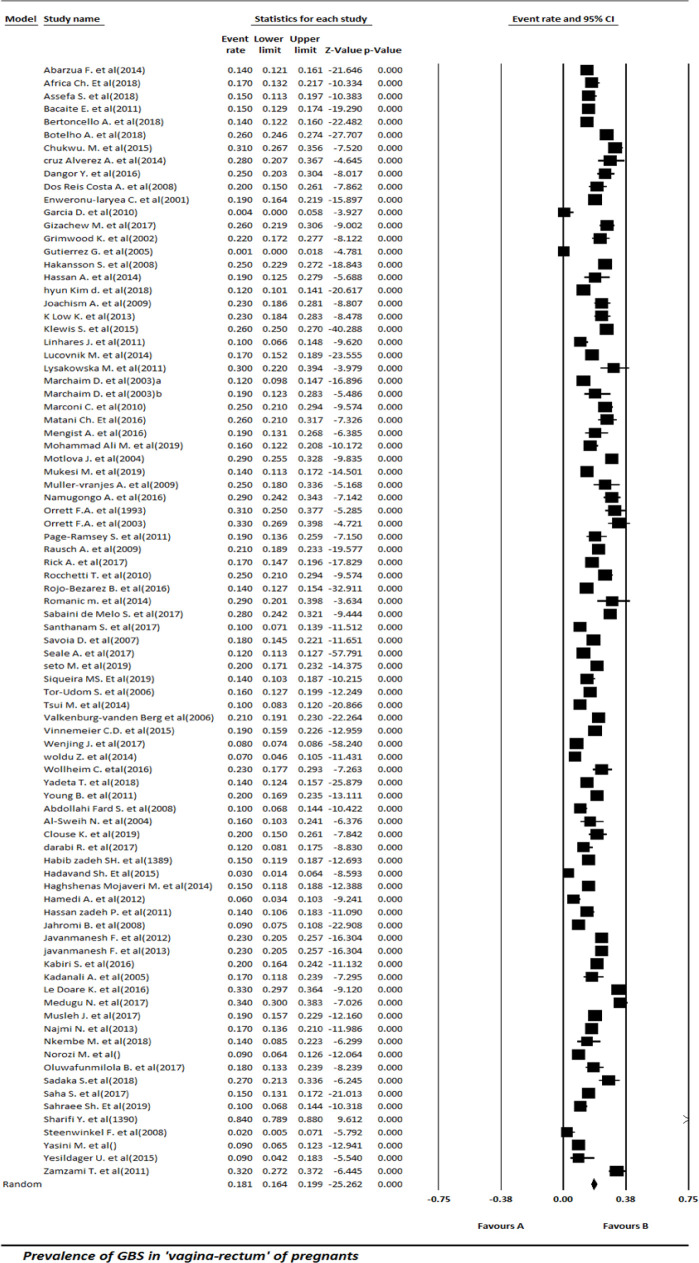

Fig. 3:

Prevalence of GBS in pregnants women of non-Islamic countries

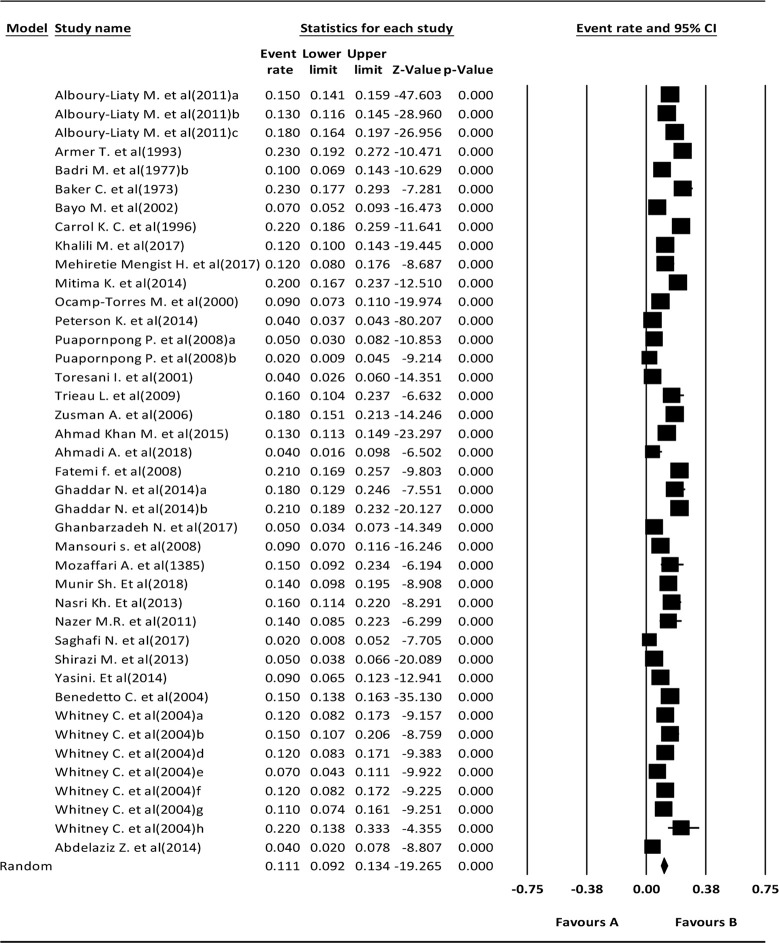

The prevalence of GBS in pregnant according to the sampling region

The sampling region in 41 studies was vagina and the heterogeneity among included studies was meaningful (Q=1550.32, df=40, I2=97.42, P<0.001). According to the results of the meta-analysis, the prevalence of GBS in pregnant undergone sampling in the vagina was 11.1% (11.1%, CI=95% (9.2–13.4)). The prevalence of GBS in the vagina of pregnant is illustrated in (Fig. 4). The sampling region in 86 studies was vagina-rectum, and heterogeneity was meaningful statistically (Q=2561.78, df=85, I2=96.68, P<0.001). According to the results obtained from meta-analysis, the prevalence of GBS in the pregnant from whose vaginal-rectal region samples had been drown was 18.1% (18.1, CI=95% (16.4–19.9)). The prevalence of GBS in vaginalrectal region of pregnant women has been shown in (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4:

Prevalence of GBS in pregnants undergone sampling in the vagina

Fig. 5:

Prevalence of GBS in vaginal-rectal region of pregnant women

Antibiotic sensitivity

Among the papers selected, 28 papers had surveyed the rate of antibiotic sensitivity. The sensitivity caused by different antibiotics has been shown in (Table 1). Sensitivity to antibiotics in the conducted meta-analysis was 98.2% (96.5–99.1) to Ampicillin, 99.7% (99.2–99.9) to Vancomycin, 98.9% (97.7–99.5) to Penicillin, 80.9% (64.7–90.7) to Erythromycin, and 78.9% (61.8–85.9) to Clindamycin. In present study antibiotic sensitivity to Ampicillin, Vancomycin and Penicillin reached 98–99% which was meaningfully more than the sensitivity to Erythromycin and Clindamycin.

Table 1:

Sensitivity caused by different antibiotics

| Model | Effect size and 95% interval | Test of null (2-Tail) | Heterogeneity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Studies | Prevalence | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | P-value | Q-value | df (Q) | P-value | I-squared | |

| Ampicilin | 17 | 0.9828 | 0.9652 | 0.9915 | 11.01 | <0.001 | 263.91 | 16 | <0.001 | 93.93 |

| Penicilin | 24 | 0.9897 | 0.9773 | 0.9954 | 11.08 | <0.001 | 688.71 | 23 | <0.001 | 96.66 |

| Vancomycin | 17 | 0.9977 | 0.9921 | 0.9993 | 9.58 | <0.001 | 184.53 | 16 | <0.001 | 91.32 |

| Erythromycin | 16 | 0.8096 | 0.6476 | 0.9077 | 3.38 | 0.001 | 3635.97 | 15 | <0.001 | 99.58 |

| Clindamycin | 13 | 0.7590 | 0.6180 | 0.8597 | 3.37 | 0.001 | 1738.60 | 12 | <0.001 | 99.30 |

Antibiotic resistance

About 17 studies have considered antibiotic resistance. The rate of Antibiotic resistance was as follows: 82.92% (74–90) to Tetracycline, 28.14% (25–85) to Penicillin, 14.3% (10–19) to Erythromycin and 15.97% (10.5–23) to Clindamycin. In the present study, resistance to Tetracycline was meaningfully more than the resistance to Erythromycin and Clindamycin (Table 2).

Table 2:

Resistance caused by different antibiotics

| Model | Effect size and 95% interval | Test of null (2-Tail) | Heterogeneity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Studies | Prevalence | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | P-value | Q-value | df (Q) | P-value | I-squared | |

| Tetracyclin | 5 | 0.8392 | 0.7401 | 0.9054 | 5.35 | <0.001 | 154.709 | 4 | <0.001 | 97.41 |

| Erythromycin | 15 | 0.1430 | 0.1041 | 0.1933 | − 9.70 | <0.001 | 514.730 | 14 | <0.001 | 97.28 |

| Clindamycin | 14 | 0.1597 | 0.1050 | 0.2354 | − 6.74 | <0.001 | 717.800 | 13 | <0.001 | 98.19 |

| Penicilin | 3 | 0.2840 | 0.0253 | 0.8584 | − 0.66 | 0.506 | 359.704 | 2 | <0.001 | 99.44 |

The survey of serotype distribution

Among the papers surveyed, we found that 22 papers had separated various serotypes of GBS in terms of their prevalence which inducted Ia type 17%, Ib 10%, Ic 2%, II 16%, III 22%, IV 6%, V type 15%, and VI type 1%. In the conducted studies, serotype of kind III was the most prevalent, but kind II and V were in the second and third position respectively. The least prevalence belonged to the kind IV (Table 3).

Table 3:

The survey of serotype distribution

| Effect size and 95% interval | Test of null (2-Tail) | Heterogeneity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Studies | Prevalence | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | P-value | Q-value | df (Q) | P-value | I-squared | |

| La | 22 | 0.1700 | 0.1312 | 0.2174 | − 10.20 | <0.001 | 1507.88 | 21 | <0.001 | 98.61 |

| Lb | 16 | 0.1033 | 0.0879 | 0.1211 | − 23.67 | <0.001 | 197.96 | 15 | <0.001 | 92.42 |

| Lc | 2 | 0.0267 | 0.0022 | 0.2548 | − 2.79 | <0.001 | 13.04 | 1 | <0.001 | 92.33 |

| Ii | 20 | 0.1667 | 0.1280 | 0.2142 | − 10.19 | <0.001 | 872.40 | 19 | <0.001 | 97.82 |

| Iii | 22 | 0.2229 | 0.1607 | 0.3004 | − 6.07 | <0.001 | 3049.76 | 21 | <0.001 | 99.31 |

| Iv | 9 | 0.0647 | 0.0436 | 0.0952 | − 12.50 | <0.001 | 281.41 | 8 | <0.001 | 97.16 |

| V | 19 | 0.1521 | 0.0940 | 0.2368 | − 6.15 | <0.001 | 2192.46 | 18 | <0.001 | 99.18 |

| Vi | 2 | 0.0103 | 0.0026 | 0.0394 | − 6.52 | <0.001 | 10.87 | 1 | 0.001 | 90.80 |

Prevalence according to the geographical region

Due to the difference in the prevalence of GBS in different geographical regions, we decided to study it in terms of geographical region, so the prevalence of GBS according to the continents was determined separately. Maximum prevalence belonged to Australia and Oceania with 22.54% and minimum prevalence belonged to Asia with 12.86%. The other continents had prevalence as follows: Europe with 16.41%, South American with 18.63%, North American with 18.6%, and Africa with 19%. Considering Islamic countries such as Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Jordan which can affect the results, that is, we can see low prevalence in Islamic countries, so we have included the result of analysis for each continent separately in the appendix.

The prevalence of GBS in pregnant women of developed and developing countries

About 33 studies had been carried out in developed countries, and heterogeneity among them was meaningful (Q=2457.62, df=32, I2=98.69). In these studies, 55288 individuals were surveyed. According to the results obtained from meta-analysis by using Random Effect Model, the prevalence of GBS in pregnant was 17.74%. (17.74%, CI=95% (14.69–21.27)). The prevalence of GBS in pregnant women of developed countries has been shown in the appendix. About 99 studies had been conducted in developing countries, and the heterogeneity among them was meaningful (Q=2405.46, df=98, I2=95.93). In these studies, 60392 individuals were surveyed. According to the results obtained from meta-analysis with the use of Random Effect Model, the prevalence of GBS in pregnants was 14.92% (p:14.92, CI=95% (13.46–16.561)). The prevalence of GBS in pregnant women of developing countries has been shown in the appendix. According to Ratio Test, the difference between developed and developing countries in the prevalence of GBS in pregnants was meaningful statistically (P<0.001).

Discussion

Streptococcus group B is abundantly colonized in vagina and rectum of pregnant women which is in accordance with the surveyed studies; however, the prevalence of it differs geographically. In the present study, the prevalence of GBS in pregnant was 15.5%. There have been systematic reviews dealing with the prevalence of GBS in pregnant and its geographical distribution, but no up-to-date study has been conducted which could compare the prevalence in Islamic and non-Islamic countries.

The quality of the papers was surveyed by making use of the checklist related to the prevalence studies of JBI. Most of the papers met the requirements needed to enter our study. Out of them 10 papers did not have suitable quality, and we could not survey quality of 6 papers due to its unavailability and abstract use. Thirteen papers did not have a suitable sample size. In most papers, the respective population selection method had taken place without randomization, and the method of sampling and culture had not been extensively stated in 17 papers. Moreover, there had been no reference to the sampling method in 5 papers; however, the other papers had explained the sampling method and the suitable culture media in detail.

In this study, the general prevalence of GBS in Islamic and non-Islamic countries was 14% and 16.3% respectively, but this result should be analyzed in terms of the study restrictions and the effects brought about by defacing variants.

Majority of the studies had been carried out with large sample size in developed countries, yet less developed countries had small sample size, and no study had been conducted to represent the difference between developed and developing countries in this respect. In the present study, the prevalence in developed and less developed countries was 17.74% and 14.92% respectively. Considering the fact that all Islamic countries belong to the less developed group of countries, we cannot rely on the low prevalence of this infection in Islamic countries only because of the repeated wash which is the hypothesis of this study. Another limitation of the studies was concerned with using various culture medias. Through surveying the papers, we noticed that enriched culture media had been used a lot in developed countries, but in less developed countries such as Islamic countries where researchers had utilized culture medias based on Blood Agar. Since culture medias based on Blood Agar bearing less sensitivity in diagnosis cause the prevalence to seem low, making firm judgment about the low prevalence in Islamic countries may lead to ambiguity.

Still another limitation of the surveyed papers was that the sample had been selected in an un-random manner in the majority of them which causes us to give contradictory judgment about the results of the study.

Another limitation of the studies was related to the time of sampling in pregnant. In the systematic review carried out recently, researchers have come to the conclusion that the prevalence of GBS in pregnant sampled before the 35th week was more than those sampled after 35th week. However, the result of the sampling in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters compared with that of early weeks of pregnancy are more predictable in the case of colonization of pregnant by GBS. Considering the point that the exact date of sampling had not been mentioned in some papers or the date had covered a long period of pregnancy in some others such as 2nd and 3rd trimester, in the present study, analysis and conclusion drawn about the prevalence in terms of sampling time was impossible.

Conclusion

Frequent washing of perineum based on religious instructions in Islamic countries can diminish the rate of GBS colonization in pregnant women.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the deputy of research of the center in which the study was performed.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Savoia D, Gottimer C, Crocilla C, Zucca M. (2008). Streptococcus agalactiae in pregnant women: phenotypic and genotypic characters. J Infect, 56(2):120–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker CJ, Goroff DK, Alpert S. (1977). Vaginal colonization with group B Streptococcus: a study in college women. J Infect Dis, 135(3):392–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Records K, Tanaka L. (2015). 5 Physiology of Pregnancy. Core Curriculum for Maternal-Newborn Nursing E-Book:83.

- 4.López Sastre JB, Fernández Colomer B, Coto Cotallo GD, et al. (2005). Trends in the epidemiology of neonatal sepsis of vertical transmission in the era of group B streptococcal prevention. Acta Paediatr, 94(4):451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmeiro JK, Dalla-Costa LM, Fracalanzza SE, et al. (2010). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of group B streptococcal isolates in southern Brazil. J Clin Microbiol, 48(12):4397–4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zangwill KM, Schuchat A, Wenger JD. (1992). Group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1990: report from a multistate active surveillance system. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ, 41(6):25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rallu F, Barriga P, Scrivo C, et al. (2006). Sensitivities of antigen detection and PCR assays greatly increased compared to that of the standard culture method for screening for group B streptococcus carriage in pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol, 44(3):725–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fultz-Butts K, Gorwitz RJ, Schuchat A, Schrag S. (2002). Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease; revised guidelines from CDC. [PubMed]

- 9.Hamedi A, Akhlaghi F, Seyedi SJ, Kharazmi A. (2012). Evaluation of group B streptococci colonization rate in pregnant women and their newborn. Acta Med Iran, 50 (12):805–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaleznik DF, Rench MA, Hillier S, et al. (2000). Invasive disease due to group B Streptococcus in pregnant women and neonates from diverse population groups. Clin Infect Dis, 30 (2):276–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilk K, Sikora J, Bakon I, et al. (2003). Significance of group B Streptococcus (GBS) infections in parturient women. Ginekol Pol, 74 (6):463–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goffinet F, Maillard F, Mihoubi N, et al. (2003). Bacterial vaginosis: prevalence and predictive value for premature delivery and neonatal infection in women with preterm labour and intact membranes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 108 (2):146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dechen TC, Sumit K, Ranabir P. (2010). Correlates of vaginal colonization with group B streptococci among pregnant women. J Glob Infect Dis, 2 (3):236–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molnar P, Biringer A, McGeer A, McIsaac W. (1997). Can pregnant women obtain their own specimens for group B streptococcus? A comparison of maternal versus physician screening. The Mount Sinai GBS Screening Group. Fam Pract, 14 (5):403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell NJ, Seale AC, O’Driscoll M, et al. (2017). Maternal colonization with group B Streptococcus and serotype distribution worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis, 65 (suppl_2):S100–S111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]