Abstract

BACKGROUND

Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD) is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder that results from a deficiency of α-galactosidase A enzyme activity in which glycosphingolipids gradually accumulate in multi-organ systems. Cardiac manifestations are the leading cause of mortality in patients with AFD. Among them, arrhythmias comprise a large portion of the heart disease cases in AFD, most of which are characterized by conduction disorders. However, atrial fibrillation as a presenting sign at the young age group diagnosed with AFD is uncommon.

CASE SUMMARY

We report a case of a 26-year-old man who was admitted with chest discomfort. Left ventricular hypertrophy was fulfilled in the criteria by the Sokolow-Lyon index and atrial fibrillation on the 12 Leads-electrocardiography (ECG) that was documented in the emergency room. After spontaneously restored to normal sinus rhythm, relationships between P and R waves, including a shorter PR interval on the ECG, were revealed. The echocardiographic findings showed thickened interventricular septal and left posterior ventricular walls. Based on the clues mentioned earlier, we realized the possibility of AFD. Additionally, we noticed the associated symptoms and signs, including bilateral mild hearing loss, neuropathic pain, anhidrosis, and angiokeratoma on the trunk and hands. He was finally diagnosed with classical AFD, which was confirmed by the gene mutation and abnormal enzyme activity of α-galactosidase A.

CONCLUSION

This case is a rare case of AFD as a presentation with atrial fibrillation at a young age. Confirming the relationship between P and Q waves on the ECG through sinus rhythm conversion may help in differential diagnosis of the cause of atrial fibrillation and hypertrophic myocardium.

Keywords: Fabry disease, Atrial fibrillation, Electrocardiography, Cardioversion, Glycosphingolipids, Case report

Core Tip: Atrial fibrillation as the initial presenting sign at a young age is rare. It was essential to identify the cause of the atrial fibrillation and hypertrophic myocardium with no history of hypertension in the young patient. Even though atrial fibrillation was incidentally converted into sinus rhythm, the restored rhythm clarified the shortened PR interval and segment without delta wave, which became a crucial clue for Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD) diagnosis. Therefore, sinus conversion to detect the relationship between P and QRS may be needed and helpful in differential diagnoses such as AFD and other heart diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD) is an X-linked genetic disorder that arises from a mutation in the galactosidase A gene, encoding α-galactosidase A (GLA). The deficiency of enzyme GLA activity leads to the accumulation of glycosphingolipids in multi-systems[1,2]. Cardiac manifestations in AFD have been reported, with an incidence of up to 37%[3]. Palpitations and arrhythmias have a prevalence of 27%[4]. Shah et al[1] reported AFD patients with persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) (only 3 of 78, or 3.9%) and with 8 (13.3%) patients having paroxysmal AF during a follow-up of 1.9 years. However, no AF under 38 years of age was observed in the cohort.

Because cardiovascular death, including sudden death, is a leading cause of AFD mortality, early diagnosis of cardiac involvement is vital to prevent progression. Here, we describe a case of a 26-year-old man with AFD who presented paroxysmal AF and typical electrocardiography (ECG) and echocardiographic findings after sinus conversion.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 26-year-old man was referred to our hospital with chest discomfort.

History of present illness

The chest discomfort located substernal area started suddenly 30 min ago and was accompanied by palpitation.

History of past illness

About two years prior, he had a history of taking some medicines for three months at another clinic because of arrhythmia but did not know the details of the previous event and did not follow up with the clinic since then. Alcohol consumption was approximate 30 g per week. A family history related to cardiovascular disease could not be confirmed because the parents no longer have been out of touch with him after the divorce.

Personal and family history

A family history related to cardiovascular disease could not be confirmed because the parents no longer have been out of touch with him after the divorce.

Physical examination

Upon arrival, vital signs were as follows: blood pressure of 150/90 mmHg, pulse rate of 94 bpm, respiratory rate of 20 per minute, and body temperature of 36.6 °C. His blood pressure during the hospitalization period did not exceed over 130/84 mmHg. He had no history of hypertension. There was no symptom and sign suggesting volume overload.

Laboratory examinations

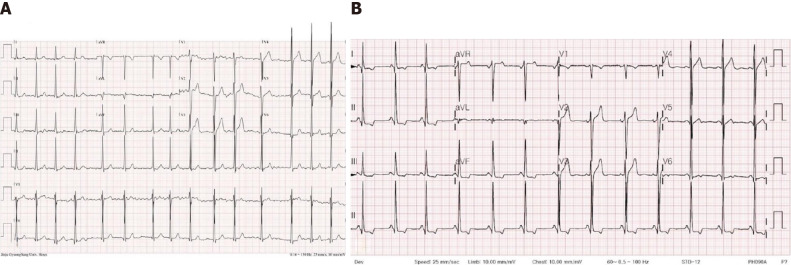

A chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly, but there was no evidence of pulmonary congestion and pleural effusion. The ECG showed AF with the controlled ventricular response and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) in voltage criteria by the Sololow-Lyon index (R in V5 > 35 mm) upon visit at the emergency department (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

The patient’s electrocardiogram before and after rhythm conversion. A: The electrocardiogram (ECG) shows atrial fibrillation with left ventricular hypertrophy upon admission; B: After spontaneous rhythm conversion to normal sinus rhythm, the surface ECG reveals a short PR interval (120 ms) and an unmeasurable Pend-Q interval.

The results of blood chemistry were as follows: BUN, 11.0 mg/dL, creatinine, 0.73 mg/dL; troponin-I, 0.1 ng/mL (ref. 0.0-0.16); and N terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide, 136.0 pg/mL. The amount of albuminuria for 24 h was 17.6 mg (the category A1 as normal to mildly increased range < 30 mg).

Imaging examinations

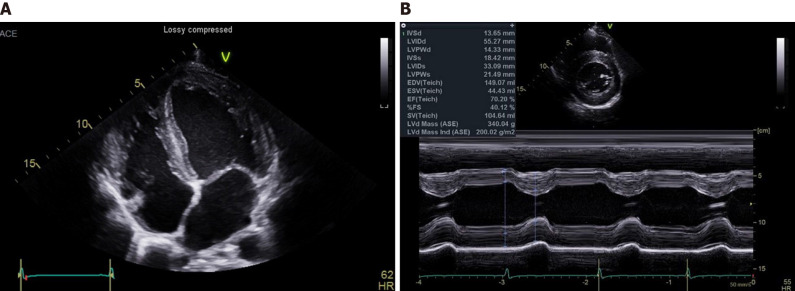

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed interventricular septum/Left ventricular posterior wall thickness, measured as 14/14 mm, respectively; left ventricular mass index, 200 g/m2; the left ventricular ejection fraction, 65%; left atrial volume index, 45 mL/m2; thickened mitral valve leaflets without functional abnormality and no wall motion abnormality (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Echocardiographic images in the patient with Fabry disease. A: The apical 4-chambers view reveals brighten endocardium, slightly thickened mitral valves, and thickened left atrial wall; B: M-mode shows thickened left ventricular walls (up to 14 mm).

Further diagnostic work-up

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed to control the symptom before electric cardioversion. Spontaneous restoration of sinus rhythm during the TEE was noticed. The 12 Leads-ECG followed by the TEE revealed the link between P and R waves that was abnormally shortened. The follow-up ECG showed a short PR interval of less than 120 ms but no delta waves (Figure 1B). The relationship between P and R waves on the following ECG, severely symmetric LVH without a history of hypertension, and unusual presenting with AF in the young age group suggested congenital myocardial disease. The patient was needed to re-evaluate the other missing clinical symptoms and signs related to multi-organ involvement. Additionally, there were bilateral mild hearing loss, neuropathic pain, anhidrosis, and angiokeratoma on the trunk and hands. (Figure 3). Corneal verticillata on the ophthalmic examination was observed. Genetic tests and GLA enzyme activity were performed to confirm AFD. The enzyme activity of GLA was 1.7 nmol/hr/mg (< 0.1% of normal range), and mutation of the GLA gene was detected in exon-7 with c.1024C>T variant.

Figure 3.

Cutaneous manifestations in the patient. Angiokeratomas (small, numerous, and dark red/purple spots) on both hands and flank are observed. A: Hands; B: Flank.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The young patient was finally diagnosed with AFD.

TREATMENT

According to the discretion of the emergency physician, a trial of propafenone i.v. (Rytomornom®, Abbott) Relieving the symptom and rhythm conversion was tried, but no response to AF before performing the TTE. After confirming the AFD, enzyme replacement therapy was started.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient diagnosed with AFD had an unusual presentation as AF at a young age. The fast and irregular activity of atriums that masking the PR segment can confuse and delay the diagnosis of AFD. It has been two years since diagnosed with AFD. He has followed for enzyme replacement therapy without any cardiac events.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the young man with AFD presented paroxysmal AF. After spontaneous sinus conversion, a shortened PR interval without pre-excitation and LVH on the 12-lead ECG were disclosed, which led to helping in working and correct diagnosis.

Earlier clinical manifestations include the peripheral nervous system, dermatologic angiokeratomas, gastroenterological, and ophthalmological symptoms[5]. Cardiovascular and renal manifestations present later, usually in young adulthood. According to the Fabry registry (NCT 00196742), cardiovascular complications develop in 40% of the patients[6]. Cybulla et al[3] reported cardiac manifestations in AFD of up to 37%. The primary pathophysiology is globotriaosylceramid (GL3) accumulation in cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, and the conduction system[7]. The clinical consequences were well known, such as ECG abnormalities, including shortened PR interval and T wave inversion, LVH, myocardial fibrosis, and arrhythmia. However, it is difficult to notice the specific ECG findings concerning AFD without some suspicious clinical findings. LVH is the most frequent but later sign and non-specific, often absent in patients less than 15 years old[6]. Unlike the LVH, a short PR interval could be the first sign of cardiac manifestation of AFD. Namdar M revealed that the P wave duration (sensitivity 92% and specificity 80%) was the most predictive for early diagnosis of AFD[8]. The short PR interval and short P-end-Q interval were also useful in differentiation to other cardiac diseases such as LVH, hypertensive heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, aortic stenosis, and amyloidosis[8]. Interestingly, the prevalence of AFD in the cohorts of HCM patients is 1%-3%[9,10]. Furthermore, there was no genetic abnormality in 30%-40% of patients who were diagnosed with AFD. These findings make it more challenging to diagnose AFD. In this patient, atrial and mitral annular thickening on echocardiography might be evidence of GL3 infiltration, which causes a shortened PR interval. Although a shortened PR interval in the patients with an earlier stage of AFD was reported only 14% incidence, the ECG finding would be more helpful in young AFD patients[8], as in this case.

Shah et al[1] showed a prevalence of 14% AF among 78 patients during a follow-up of 1.9 years. AF may be caused by infiltration of GL3 in the atriums and diastolic dysfunction resulting from progressive LVH. AF is a result of remodeling myocardium filtrated with GL3 as one of the later complications in AFD. There was no report in childhood and young adults.

The reversibility of cardiac manifestations after ERT is still controversial[11,12]. Schmied et al[13] showed that cardiac disease progression in patients with abnormal ECG at the time of treatment initiation compared with patients with normal ECGs and suggested ECG assessments at an earlier stage and ERT initiation before ECG abnormalities develop.

Gubler et al[14] revealed that endothelial deposit of GL3 and glomerular sclerosis could be confirmed in most cases even though the young patients with AFD had 30 mg or less per day of proteinuria. Therefore, an earlier renal biopsy would play a vital role in confirmative diagnosis of AFD. However, there was no study on the usefulness and safety of earlier renal biopsy in patients with AFD in the A1 category of proteinuria according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2012 guidelines[15], and Ortiz et al[16] recommended that if baseline albuminuria > 30 mg/24 h is shown, it can be considered as an indication of ERT. In this case, the amount of albuminuria for 24 h was 17.6 mg. We thought that renal manifestation in this patient was started, and renal biopsy was not needed in aspect of decision of diagnosis and starting treatment, because other organ involvement signs were definite.

CONCLUSION

We report here that a young adult with AFD can present with AF. For early diagnosis and initiation of ERT, the ECG findings, such as short PR interval and LVH, should be carefully assessed.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 28, 2021

First decision: February 25, 2021

Article in press: May 15, 2021

Specialty type: Cardiac and Cardiovascular Systems

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhu F S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Hangyul Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju 52727, South Korea.

Min Gyu Kang, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju 52727, South Korea.

Hyun Woong Park, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju 52727, South Korea.

Jeong-Rang Park, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine and Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju 52727, South Korea.

Jin-Yong Hwang, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine and Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju 52727, South Korea.

Kyehwan Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju 52727, South Korea. nicol2000@nate.com.

References

- 1.Shah JS, Hughes DA, Sachdev B, Tome M, Ward D, Lee P, Mehta AB, Elliott PM. Prevalence and clinical significance of cardiac arrhythmia in Anderson-Fabry disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:842–846. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel V, O'Mahony C, Hughes D, Rahman MS, Coats C, Murphy E, Lachmann R, Mehta A, Elliott PM. Clinical and genetic predictors of major cardiac events in patients with Anderson-Fabry Disease. Heart. 2015;101:961–966. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cybulla M, Walter K, Neumann HP, Widmer U, Schärer M, Sunder-Plassmann G, Jansen T, Rolfs A, Beck M. [Fabry disease: demographic data since introduction of enzyme replacement therapy] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007;132:1505–1509. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-982060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linhart A, Kampmann C, Zamorano JL, Sunder-Plassmann G, Beck M, Mehta A, Elliott PM European FOS Investigators. Cardiac manifestations of Anderson-Fabry disease: results from the international Fabry outcome survey. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1228–1235. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortiz A, Germain DP, Desnick RJ, Politei J, Mauer M, Burlina A, Eng C, Hopkin RJ, Laney D, Linhart A, Waldek S, Wallace E, Weidemann F, Wilcox WR. Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2018;123:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson HC, Hopkin RJ, Madueme PC, Czosek RJ, Bailey LA, Taylor MD, Jefferies JL. Arrhythmia and Clinical Cardiac Findings in Children With Anderson-Fabry Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagège A, Réant P, Habib G, Damy T, Barone-Rochette G, Soulat G, Donal E, Germain DP. Fabry disease in cardiology practice: Literature review and expert point of view. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;112:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namdar M, Steffel J, Vidovic M, Brunckhorst CB, Holzmeister J, Lüscher TF, Jenni R, Duru F. Electrocardiographic changes in early recognition of Fabry disease. Heart. 2011;97:485–490. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.211789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monserrat L, Gimeno-Blanes JR, Marín F, Hermida-Prieto M, García-Honrubia A, Pérez I, Fernández X, de Nicolas R, de la Morena G, Payá E, Yagüe J, Egido J. Prevalence of fabry disease in a cohort of 508 unrelated patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2399–2403. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kampmann C, Baehner F, Ries M, Beck M. Cardiac involvement in Anderson-Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13 Suppl 2:S147–S149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eng CM, Guffon N, Wilcox WR, Germain DP, Lee P, Waldek S, Caplan L, Linthorst GE, Desnick RJ International Collaborative Fabry Disease Study Group. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A replacement therapy in Fabry's disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:9–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madsen CV, Bundgaard H, Rasmussen ÅK, Sørensen SS, Petersen JH, Køber L, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Petri H. Echocardiographic and clinical findings in patients with Fabry disease during long-term enzyme replacement therapy: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2017;51:207–216. doi: 10.1080/14017431.2017.1332383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmied C, Nowak A, Gruner C, Olinger E, Debaix H, Brauchlin A, Frank M, Reidt S, Monney P, Barbey F, Shah D, Namdar M. The value of ECG parameters as markers of treatment response in Fabry cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2016;102:1309–1314. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gubler MC, Lenoir G, Grünfeld JP, Ulmann A, Droz D, Habib R. Early renal changes in hemizygous and heterozygous patients with Fabry's disease. Kidney Int. 1978;13:223–235. doi: 10.1038/ki.1978.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens PE, Levin A Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:825–830. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortiz A, Oliveira JP, Wanner C, Brenner BM, Waldek S, Warnock DG. Recommendations and guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Fabry nephropathy in adults. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4:327–336. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]