Abstract

HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects African-Americans more than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States. Currently representing only 12% of the US population, African-Americans now comprise close to half of the total reported HIV/AIDS cases in the United States according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since the initial reporting of HIV/AIDS. In this paper, we examined the prevalence and current direction of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the African-American community especially in comparison to our first call to action in 2008. The situation remains dire and broader attention is necessary from the public health and medical sectors who serve majority African-American populations and the community at-large to work towards closing this health disparity gap. This paper thus recommends an action plan for community leaders (i.e., the public health sector, policy makers, public health practitioners, and other stakeholders) to reduce the disparity.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, African-Americans, STDs, Socioeconomic Status, Epidemic

Introduction

Although there has been a recent drop in HIV diagnoses across every population group in the United States (US), African-Americans are significantly more likely to contract the disease. At the end of 2014, 471,500 African-Americans were living with HIV which encompasses 43% of everyone living with HIV in the US [1]. In 2016, African-Americans represented 44% (17,528) of newly diagnosed infections [1]. Among that group, more than half (58%, 10,223) of African-Americans diagnosed with HIV were Black men that have sex with men (MSM) [2]. Although measures have been taken in the last decade to address this epidemic, more effective strategies must be implemented, especially in communities where African-Americans primarily reside, to close this disparity.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created a strategy to reduce the incidence of HIV/AIDS through 2020 that must be taken further in order to reduce the incidence rate among the African-American community [3]. We believe there must be an even more assertive approach than the one we called for in 2008 to end this epidemic [4]. The objective of this perspective article is to provide the current landscape of HIV/AIDS in the African-American community and to signal the need for an even stronger call to action than the one relayed a decade ago, in the hope that finally the disparities seen among African-Americans and other minority groups will be successfully addressed. This paper also suggest a five-fold action plan for stakeholders to finally succeed in addressing these disparities.

Recent Statistics

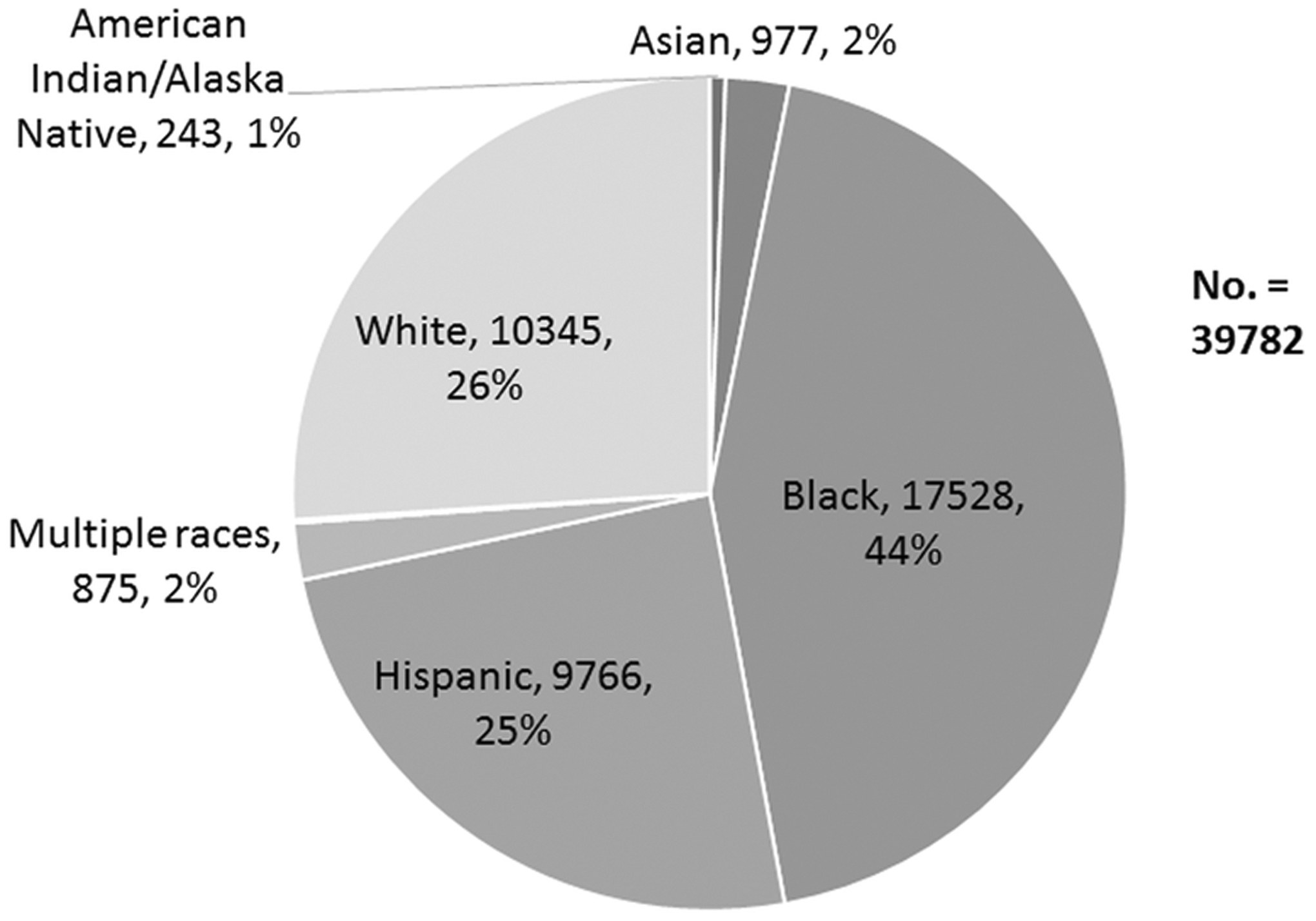

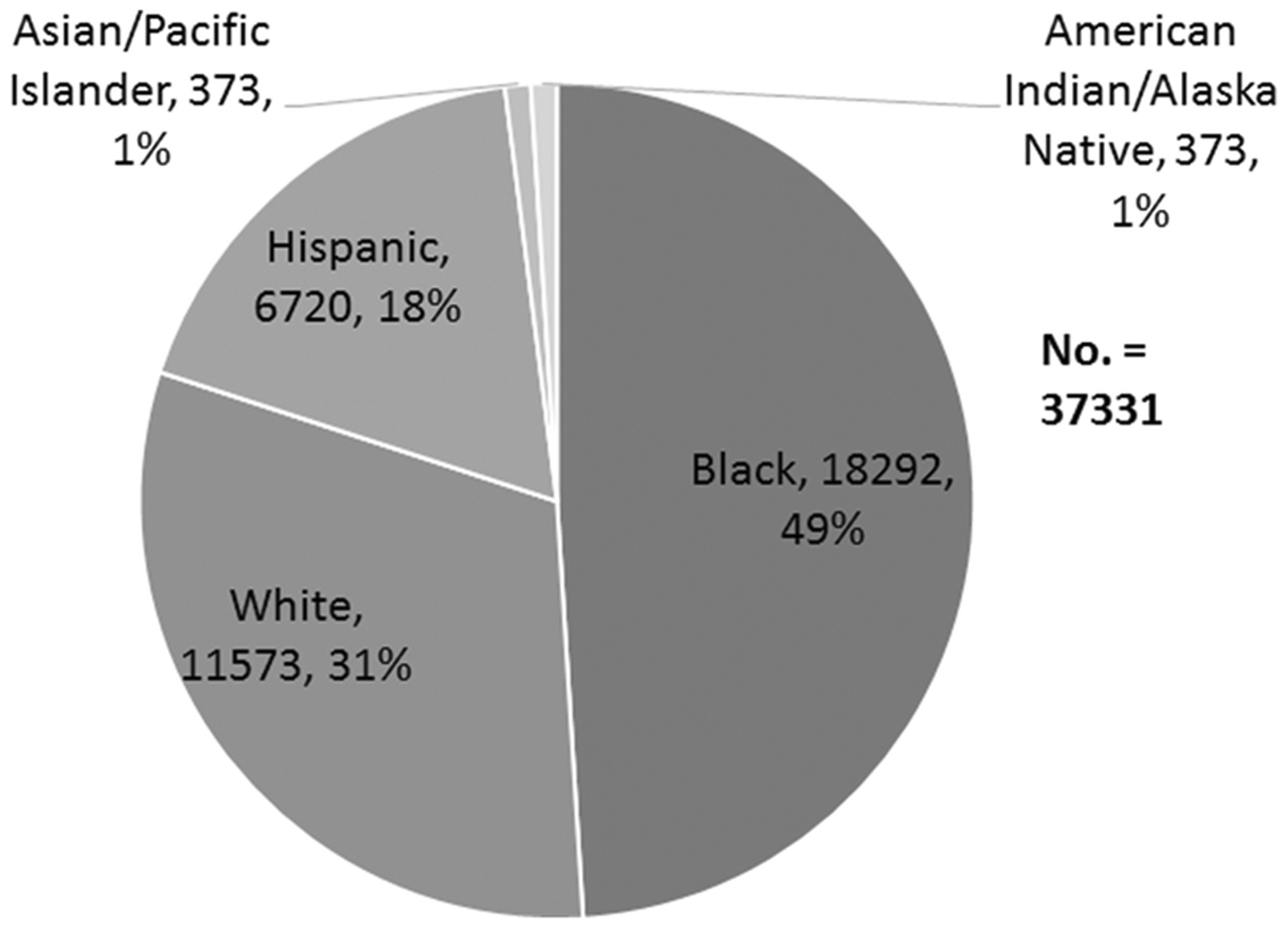

African-Americans represent approximately 12% of the United States population according to the 2010 United States census [3]. However, the 2016 HIV Surveillance Report by the Centers for Disease Control found that African-Americans account for 17,528 (44%) of the estimated 39,782 new HIV diagnoses in the US (Figure 2) [5]. When data is compared from 2005 to 2016, we see that while the percentage has slightly reduced, numbers continue to remain very high. In addition, the 2016 Surveillance Report also includes a category of multi-racial ethnicity, which could include those that might be classified under African-American in 2005 (Figures 1 and 2). Further calling into question the accuracy of the data provided by the 2016 Surveillance Report is the failure to designate origins of the African-Americans diagnosed as this information could be vital to providing a greater reference point to localize the cause and create focused treatment efforts for this epidemic.

Figure 2.

New HIV Diagnoses (including children) by Race 2016

Adapted from 2016 HIV Surveillance Report by the CDC [4].

Figure 1.

New HIV Diagnoses (including children) by Race 2005

Adapted from 2005 CDC Fact Sheet: HIV/AIDS among African-Americans [8].

The estimated annual HIV diagnosis rate in 2016 among African-American males was 82.8 per 100,000 population and 26.2 per 100,000 among African-American females, both significantly higher than the rate of 24.3 per 100,000 for males and 5.4 per 100,000 for the total population [5]. This disparity is even more prominent when compared to other races. Among the male populations, the HIV diagnosis rate is 38.8 per 100,000 for Hispanics/Latinos and 10.6 per 100,000 for Whites [5]. Among the female populations, the HIV diagnosis rate is 5.3 per 100,000 for Hispanic/Latinos and 1.7 per 100,000 for Whites [5]. These numbers indicate that African-American males are 2.1 times more likely than their Hispanic/Latino counterparts and 7.8 times more likely than their White counterparts to be diagnosed with HIV. African-American females are 4.9 times more likely than Hispanic/Latino females and 16.4 times more likely than White females to be diagnosed with HIV. For male and female populations, African-Americans are 2.6 times more likely than their Hispanic/Latino counterparts and 8.4 times more likely than their White counterparts. In 2005, African-Americans were 2.5 times more likely than their Hispanic/Latino counterparts and 7.9 times more likely than their White counterparts to be diagnosed with HIV, providing further evidence that the disparity in the incidence rate of HIV in the African-American population continues to grow.

The disproportionality is not just prominent among adults, but affects infants and children as well. In 2016, 64 (65%) of the estimated 99 infants perinatally infected with HIV were African-American. Of the 38 U.S. children (age <13) who received new AIDS diagnoses, 25 (66%) were African-American indicating that African-American children are three times (.3 per 100,000 children) more likely to be diagnosed with AIDS than the total population (.1 per 100,000 children) [5]. The disparity between African-American infants and their other racial counterparts continues to increase from 2005 as the number of African-American infants diagnosed with the disease has stayed relatively the same (74, 66%) while Whites (16, 14.4%) and Hispanic/Latinos (19, 17%) numbers have decreased in the past decade (Whites – 13, 13.1% and Hispanics/Latinos – 15, 15.1%) even with their population percentages increasing in comparison to African-Americans [6].

Of the total population of women living with diagnosed HIV at the end of 2014, 60% (139,058) were African-American [7]. During the time period from 2005 to 2014, new HIV diagnoses among African-American women fell 42%, but are still significantly higher compared to other races and ethnicities. Diagnosis rates in African-American women from 2010 to 2014 have gone from 38.7 per 100,000 to 30.0 per 100,000, showing a slight improvement in new diagnoses in African-American women [8]. The incidence rates among African-American women have seen a decrease of 21% from 2000 to 2015 [9].

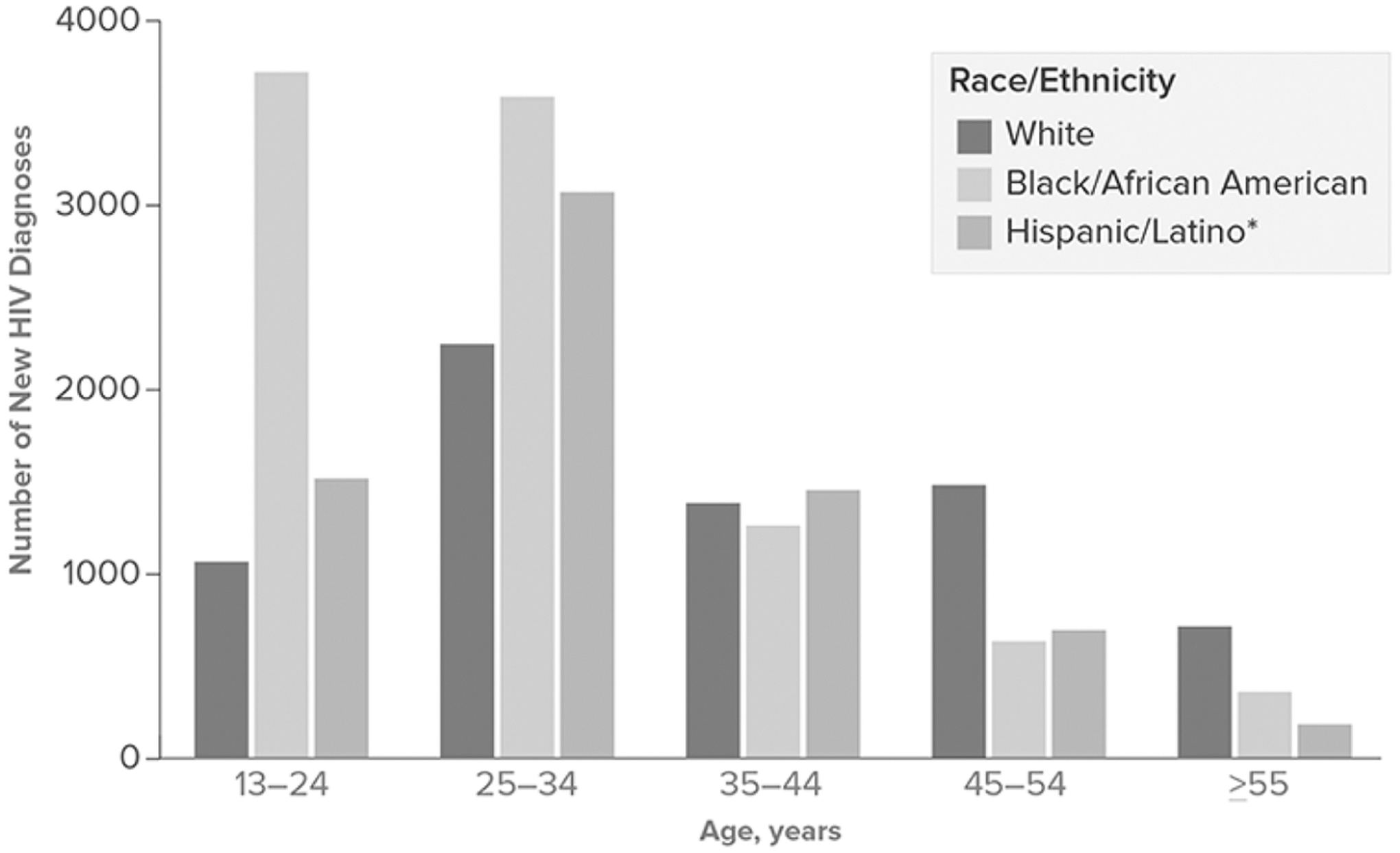

Diagnoses among the total male population declined as a whole, but diagnoses among the Black MSM population increased 22% in that time period. This endemic amongst BMSM has increased significantly in the populations aged 13 to 24 with a 30% increase from 2011 to 2015 (Figure 3). If the current rates persist, the CDC projects that approximately one in 20 African-American men, one in 48 African-American women, and one in two BMSM will receive a diagnosis of HIV during their lifetimes [1,10]. This is compared to the lifetime risk of one in 99 for all Americans and one in 11 for White gay and bisexual men. To provide more perspective the HIV prevalence rate in Swaziland, an African nation which has the highest HIV prevalence rate at 28.8% of the population would be surpassed if BMSM made up their own country [10]. The crisis is most prevalent in the Southern states, which retains 37% of the country’s population as of 2014, but accounted for 54% of all new HIV diagnoses. The South also contains 21 of the 25 metropolitan areas with the highest HIV prevalence among gay and bisexual men. Other ethnic groups have shown an increase in diagnosis rate among MSM, but American Indians/Alaskan Natives have shown the greatest increased diagnosis rate of HIV/AIDS among gay and bisexual men in the last decade with a 63% increase between 2006 and 2016 [6].

Figure 3.

HIV Diagnoses Among Men Who Have Sex with Men, by Race/Ethnicity and Age at Diagnosis, 2016. Adapted from CDC. Adapted from the CDC: HIV among African Americans [1]

Risk Factors Influencing Transmission

There is no sole culprit for the cause of the disparities seen in African-Americans in regards to HIV/AIDS [11].

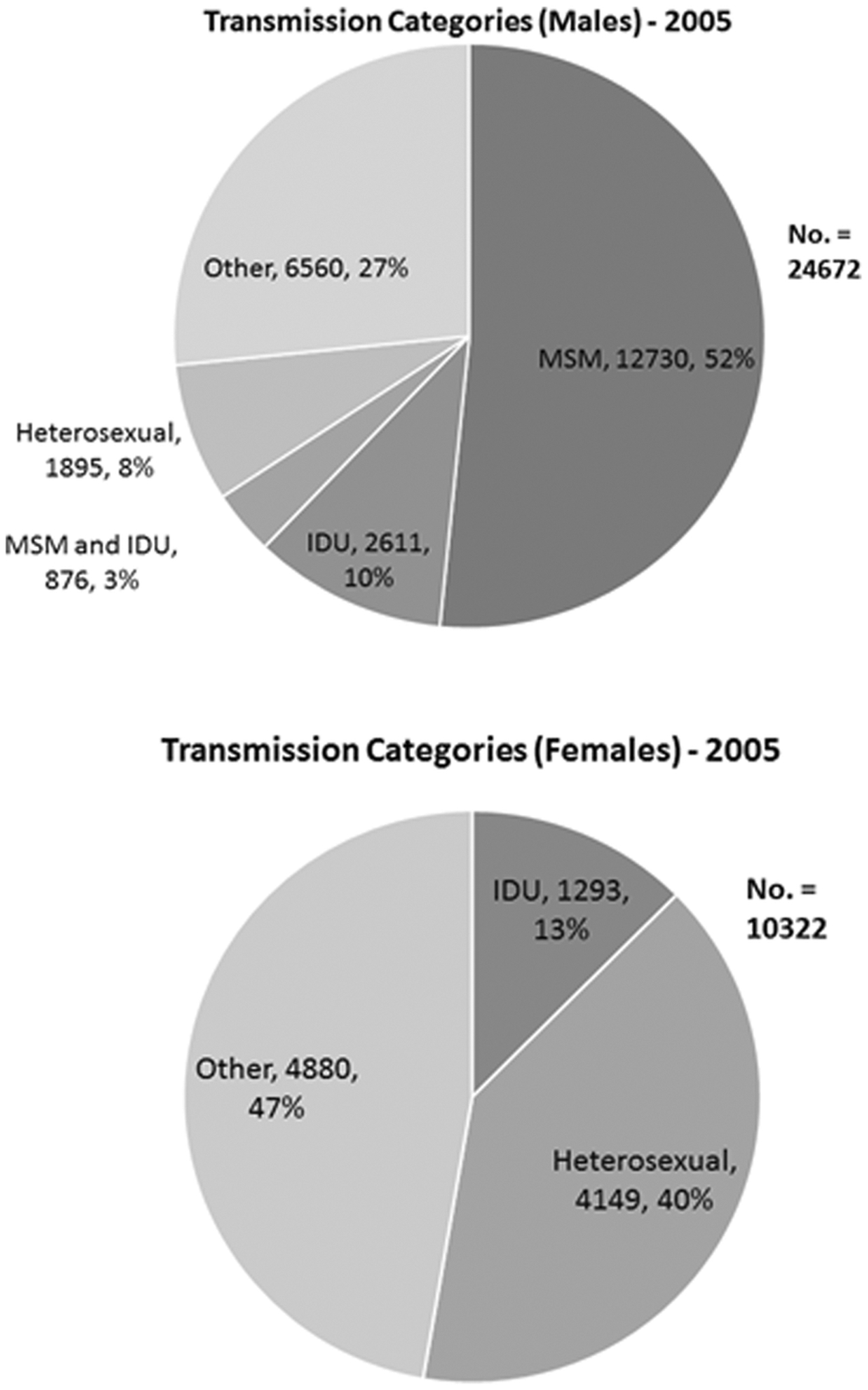

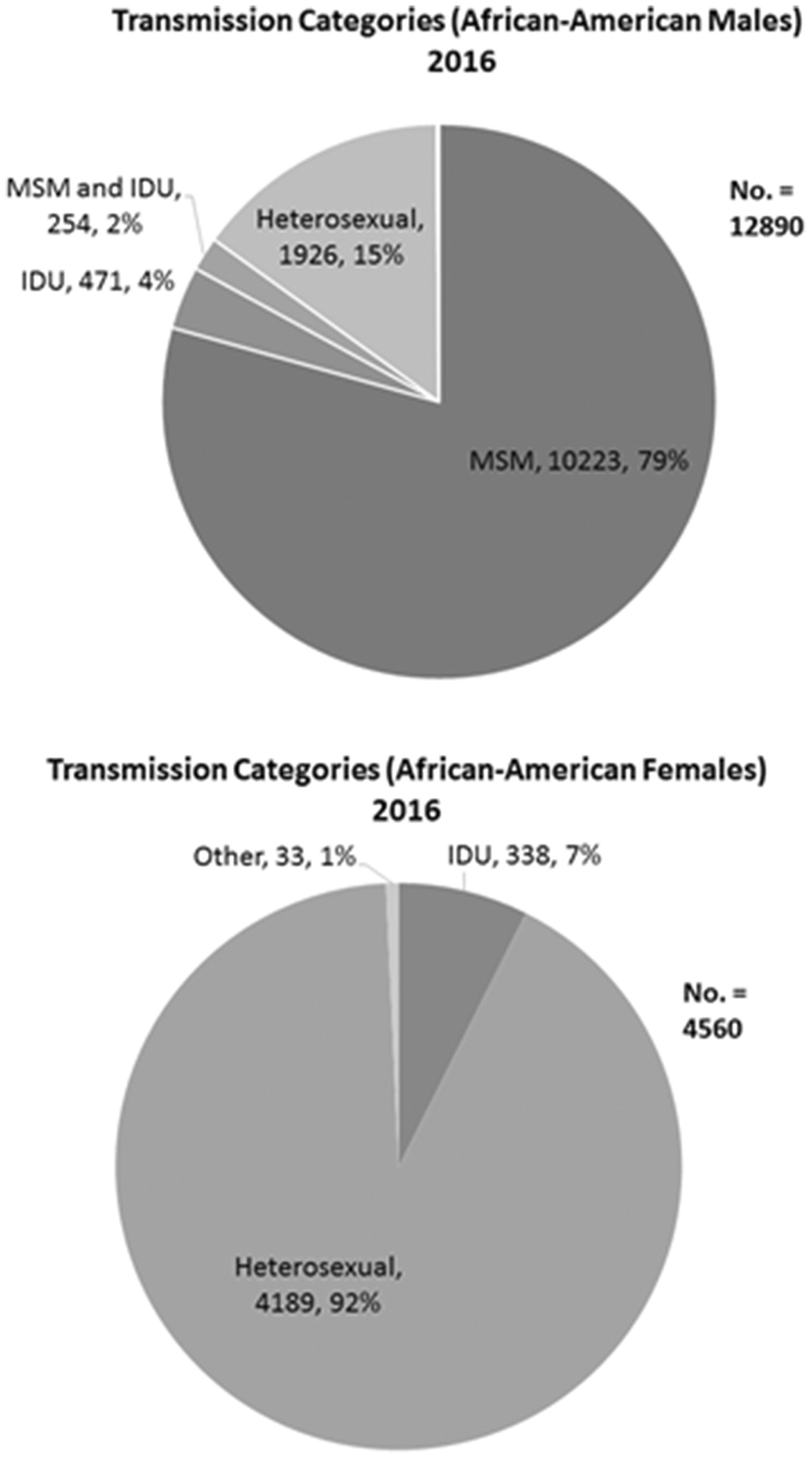

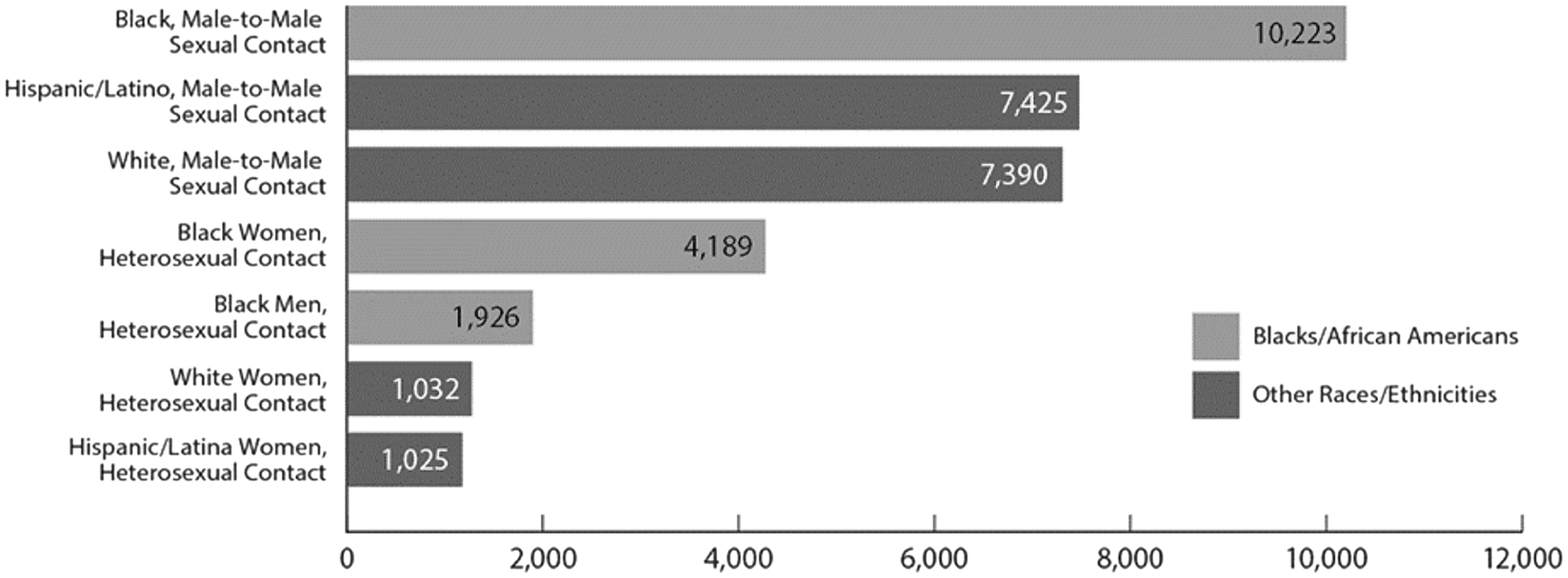

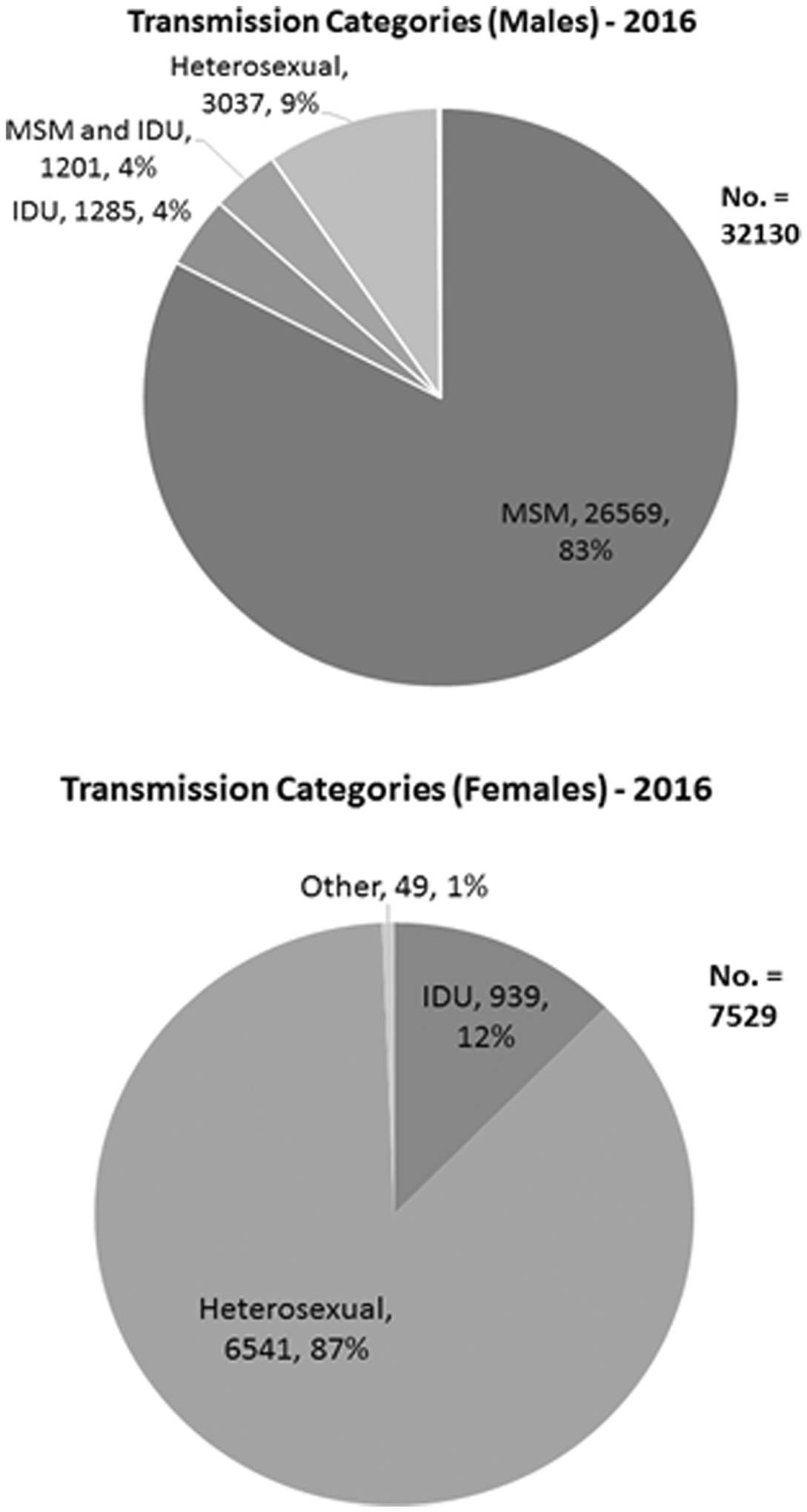

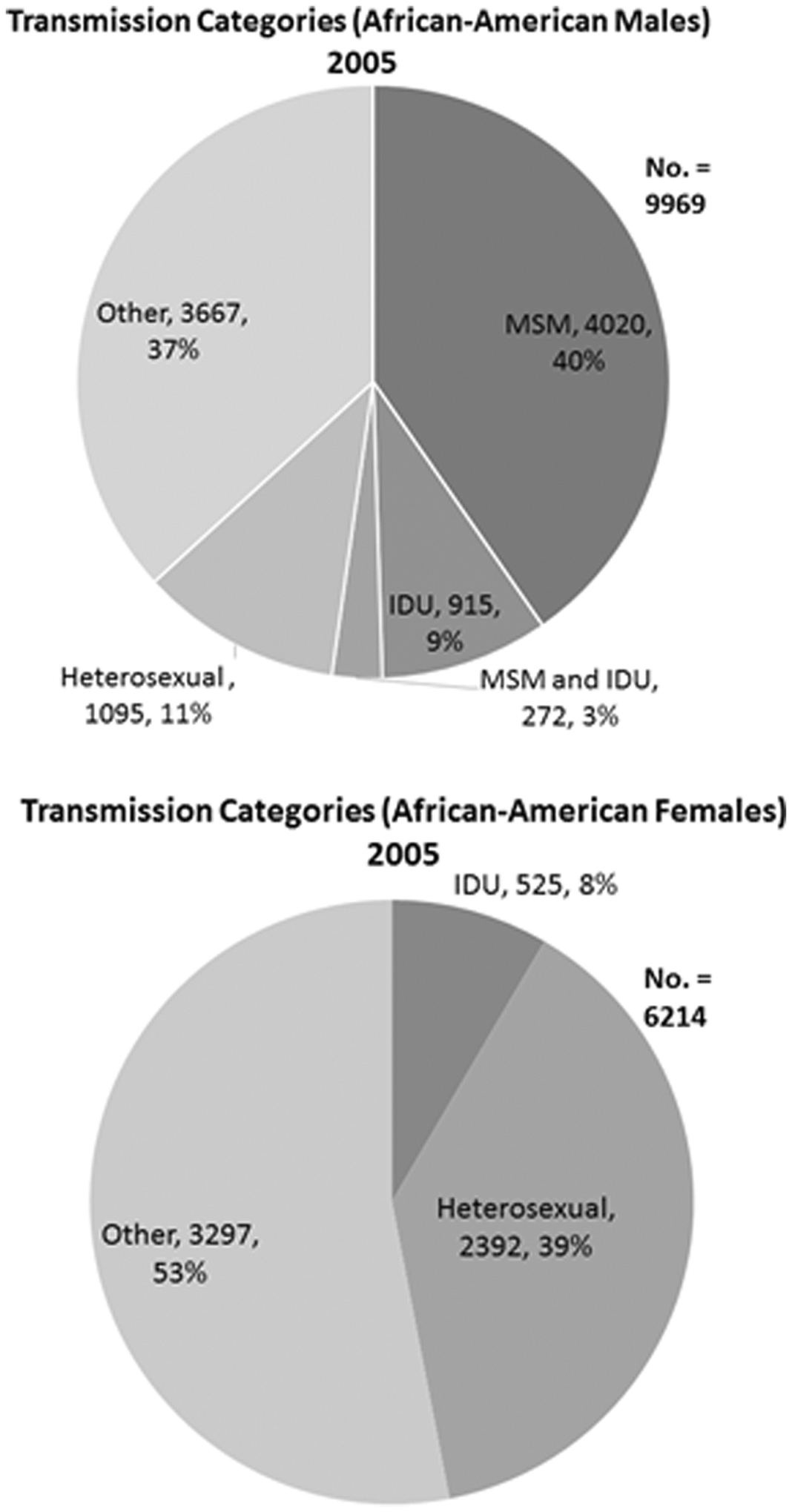

Within the African-American population alone, most HIV cases of African-American males and adolescents in 2016 are attributed to men that have sex with men (79%, 10,223), heterosexual contact (15%, 1926), intravenous drug usage [IDUs] (4%, 471), and men that have sex with men in combination with intravenous drug usage (2%, 254) in order of prevalence [5]. Among African-American female adults and adolescents, most HIV diagnoses were classified as heterosexual contact (92%, 4189) followed by intravenous drug usage (7%, 338) [5]. When comparing 2005 to 2016, we can see that the incidence rate of men that have sex with men has increased significantly amongst all races and the change is even more prominent among the African-American population. The number of African-American males diagnosed with the disease has also increased by nearly 4000 in comparison to 2005. The total population number of cases has only increased by 4000, which provides further evidence that the African-American population incidence rate continues to increase while others are declining. In the female population, the number of African-American women diagnosed with HIV from heterosexual contact has increased substantially as well (2392 to 4189), while the total population that has diagnosed HIV through heterosexual contact has declined (7734 to 6571). The total population of females diagnosed with HIV has decreased, but African-American women still account for more than sixty-percent of the women becoming newly infected [7]. A more in-depth view of these numbers can be found in Figures 5–8. Although these risk factors give a starting point for the attributors towards HIV/AIDS prevalence in the African-American community, a more in-depth look is needed to gain an understanding of the underlying factors for HIV/AIDS prevalence.

Figure 5.

Largest Categories for Affected Individuals by Sex and Transmission Influence in 2005.

Figure 8.

Largest Categories for Affected Individuals that are African-American by Sex and Transmission Influence in 2016.

Adapted from 2016 CDC Fact Sheet

Socioeconomic Status

Poverty rates are directly correlated with HIV diagnosis as well. Prevalence rates in poor urban areas were inversely related to socioeconomic status (SES), where the lower the SES the greater the HIV prevalence rate [12]. In the United States, of those in poverty, African-Americans represent 27.4% compared to 9.9% for Whites. 45.8 percent of young African-American children (under age 6) live in poverty compared to 14.5 percent of White children [13]. Hispanics are another group with high poverty rates (21.9%), but the effects of that poverty do not correlate to higher diagnosis rates of HIV/AIDS [14]. A study on how racial/ethnic identity correlates to the reduced HIV rates of Hispanics in comparison to African-Americans could be vital to discovering another mechanism to reduce the prevalence among African-American populations affected by poverty. Until the socioeconomic gradient is minimized, there will be an uphill challenge to reduce rates of HIV/AIDS amongst African-Americans.

Sexual Risk Factors

Among female adults and adolescents, from 2010–2016, the estimated number of HIV/AIDS cases decreased among intravenous drug users, but heterosexual contact increased to counterbalance that decrease. This is largely seen due to the advent of new technology to discover the mechanism of contraction for the “Other” category that was largely unknown, but now can be truly confirmed by physicians as heterosexual in origin. Heterosexual contact accounted for 92% (4189) of the infected African-American women with HIV [5]. Additionally, African-American women are more likely than White women (71%, 1032) to have acquired HIV heterosexually [5]. Greater emphasis and new programs need to be established to target the disproportionate and increasing numbers in the African-American female population or the epidemic will continue to proliferate.

Within the African-American male population, numbers have dropped for IDUs as well, but have significantly increased in BMSM over the past decade. BMSM are also more likely to contract other STDs introducing more compounding variables [15,16]. Syphilis and gonorrhea are especially more rampant in the BMSM population. A 2014 study indicated that an additional $2.5 billion is needed to address unmet testing, care, treatment and prevention needs among BMSM [10]. In 2015, only $31 million (19 percent) out of $168 million HIV/AIDS philanthropic dollars were spent in the South. Of that $168 million dollars only $26 million directly targeted African-Americans and $16 million went to men that have sex with men. Programs need to be established in order to target BMSM for testing, prevention, and early treatment.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are associated with the African-American population. In 2016, 481.2 per 100,000 African-Americans were diagnosed with gonorrhea, in comparison to 55.7 per 100,000 amongst Whites making African-Americans nine times more likely to be diagnosed with gonorrhea than their White counterparts [15]. The rate of diagnosis for syphilis was 23.1 per 100,000 amongst African-Americans, in comparison to 4.9 per 100,000 amongst Whites indicating that African-Americans are five times more likely to be diagnosed with syphilis than their White counterparts [15]. As an inflammatory STD, gonorrhea is associated with increased HIV vulnerability and infectiousness [17]. As an ulcerative STD, syphilis creates additional portals of entry through mucosal ulcerations and recruits inflammatory cells that bind and propagate HIV infection [17]. According to research done by Hughes (2012), people affected with an ulcerative STD are 2.65 times as likely as a healthy individual to diagnosed with HIV [18]. In Florida in 2010, among all persons diagnosed with infectious syphilis, 42% were also HIV positive [17]. Herpes is also associated with HIV and produces a three-fold increase risk for acquiring HIV infection [19]. Herpes is an ulcerative STD much like syphilis, leading to additional portals of entry for HIV and increased susceptibility to HIV infection. According to data gathered from 1988 to 2010, African-American males and females are significantly more likely to contract herpes simplex virus than their White equivalents. Additionally, they are more likely to be unaware of their positive status [19].

It has long been known that the presence of certain STDs can increase a person’s chances of being diagnosed with HIV significantly and also increases their chances of infecting others. Addressing the increased rates of STDs in the African-American community could be a mitigating variable to help reduce HIV diagnoses in the population. Methods establishing earlier diagnosis and treatment of these diseases as well as safe practices to avoid infection are pivotal to reduce the incidence rate of HIV amongst other STDs in the population.

Substance Use

Intravenous drug usage (IDU) has shown a marked decrease over the past decade in HIV/AIDS infection among African-Americans, but still are a contributing factor. It is the second leading cause of positive diagnosis amongst females and third leading cause among males. In 2016, IDU accounted for 4% (471) of diagnosed cases amongst African-American males [15], which is an extreme reduction in numbers compared to 2008 (10%, 1425) [12]. For African-American females, IDU accounted for 7% (338) of positive diagnosis, which is a reduction from the 12.7% in 2008 [6]. Substance users are more inclined to engage in other high-risk behaviors, such as sex without contraception while under the influence [20,21]. Substance abuse also affects the efficacy of treatment methods, as substance users are less likely to take their antiretroviral therapies as prescribed [22]. This erratic compliance prevents effective viral suppression and increases the likelihood of transmission of the virus.

Incarceration

Prison populations have recently declined, but this decade has still seen the highest total numbers in incarcerated individuals in comparison to previous decades. In 2016, 1,505,400 prisoners were under the jurisdiction of state and federal correctional authorities [23]. Of that population, 32% (486,900) were of African-American origin making the national incarceration rate for African-Americans 1,608 per 100,000 [23]. African-Americans are more than five times as likely to be imprisoned as their White counterparts. Prisoners are five times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV/AIDS than their non-incarcerated counterparts [24,25]. The number of incarcerated African-Americans, especially males has increased from 2005 to 2016 [23], adding another underlying factor that needs to be addressed to dissolve this disparity. The mass incarceration of African-Americans, especially males, and many prisons’ refusal to test, prevent and treat, needs to be addressed if we are to eliminate this reservoir of the virus that fuels the epidemic in African-American communities.

Access to Healthcare

Treatment practices has become more effective over the past few decades, but too few African-Americans are receiving adequate treatment. In 2013, 87 percent were aware of their positive status, but only 49 percent had achieved viral suppression [1]. African-Americans account for close to half of those with AIDS who have died in the United States since the beginning of the endemic. These numbers have declined by 28% from 2008 to 2012. But making African-Americans more aware of this endemic as well as increasing access to treatment would decrease these numbers more substantially as only 38 percent of African-Americans got consistent HIV healthcare treatment from 2011 to 2013. African-American males were less likely to receive consistent medical care than African-American females (35% to 44%) [26]. According to a CDC report published in 2016, at least 90 percent of HIV transmission presently comes from people with diagnosed infection who are not retained in care (69 percent) and people whose infections has not been diagnosed (23 percent) [26]. There has been an increasing trend since 2007 in African-Americans being tested [27], but more needs to be done to ensure access to HIV testing and treatment. Increased access to healthcare must be provided through greater insurance coverage among African-Americans to reduce the prevalence rate of HIV/AIDS. The barriers to access to healthcare and treatment such as lack of availability of services and the deficiency of culturally component care must be addressed to prevent the increased proliferation of HIV/AIDS in the African-American community.

HIV Serostatus Awareness

Unrecognized HIV infections among African-Americans have been an issue since the inception of this epidemic. Early diagnosis is pivotal as the earlier the individual is diagnosed, the earlier the person can benefit from lifesaving therapies and prevent unknowingly spreading the virus. In 2005, 33% of African-Americans were unaware of their positive status [4]. Of those testing positive for HIV in 2016, one in eight (13%) were previously unaware of their positivity [1]. In 2011, a study done by the National institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases found that people with HIV are far less likely to infect their sexual partners when put on treatment at onset of the infection [10]. The numbers are even more staggering in BMSM, as the CDC reported in February 2017 that only 48% of African-American gay and bisexual men effectively suppress HIV with consistent medication, and the numbers are even lower for BMSM in their late teens and 20s. In 2014, one in five BMSM had progressed to AIDS by the time they learned of their infection [10]. Timely diagnosis is critical to begin early treatment, reduce risk of transmission, and to extend life expectancy.

Stigmatization

Fear of disclosing risk behavior or sexual orientation may prevent African-Americans from seeking testing, prevention and treatment services, and seeking support from friends and family. The socialization of many African-Americans begins in the Church. The Church is seen as a realm for empowerment and well-being and has been associated with positive influences on health behaviors, coping and outcomes when promoted within the Church [28]. The homo-negativity present in many African-American Churches may prevent early diagnosis of HIV infection especially among homosexual African-American youth. Since the Church is an integral part of African-American culture, African-American youth are less likely than other adolescents to abandon their Church even if the Church is being homo-negative or negative towards HIV/AIDS [29]. A 2006–2007 nationally representative survey of US congregations indicated that only 4% of African-American churches had conducted activities to serve persons living with HIV [29,30]. This attitude could account for the higher number of incidence rates amongst BMSM as they are more likely to conceal their sexual activity and less likely to be tested because of this cognitive dissonance. A partnership amongst healthcare providers and the African-American Church is vital in order to reduce the numbers of HIV/AIDS diagnoses in the African-American community since the African-American Church is the main agent of socialization in the African-American community.

Racial Discrimination

The history of racial discrimination in the US is well-documented and still prevalent in society today. The atrocity is especially directed towards African-Americans in everyday life and works as another culprit for the increased incidence rates of HIV/AIDS among African-Americans. Residential segregation is a principal example of racial discrimination’s impact on the HIV/AIDS health disparity. The average White person lives in a community that is 80% White, in comparison to African-Americans congregating in communities that are 50% African-American and Hispanic/Latinos living with 46% of people that are also Hispanic/Latino [31]. Americans living in low income, primarily minority neighborhoods are significantly less likely to receive early HIV testing and treatment [31]. The lack of testing and treatment in the predominately minority community leads to augmented “community viral load” amongst the populace and increased progression to AIDS in these communities [31]. Regions of the United States where racial discrimination is most prominent remain hotbeds for the HIV/AIDS African-American epidemic [32]. The disparities are also more prevalent in areas such as the South, where non-White Southerners may be nearly five times more likely than those in all other regions of the United States, Canada, Australia, and Brazil, to experience serious medical complications once infected [31,32]. The dismal history of racial discrimination in the United States must be addressed and rectified in order to begin eradicating the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the African-American community.

Racial Identity

Racial identity or “an individual’s sense of having their identity defined by belonging to a particular race or ethnic group” [33] is another factor that could further proliferate the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the African-American community. A stronger racial identification and partner selection remaining within the African-American community is a determinant that also causes increased rates of HIV/AIDS diagnoses in the African-American community. The reasoning for this increased racial identification when selecting a partner among African-Americans is due to racism, racial segregation and poverty, leading to African-Americans being more likely than others to partner with members of their own race [34]. The higher incidence rates among African-Americans and the increased affinity for primarily African-American partners in the population is a factor that proliferates the HIV/AIDS disparity in the African-American populace.

Strategies for Prevention and Action

The CDC has implemented the National HIV/AIDS strategy through 2020 that utilizes data since 2010. The strategic goals are to: 1) Reduce new infections, 2) Increase access to care and improve health outcomes for people living with HIV, 3) Reduce HIV-related health disparities and health inequities, and 4) achieve a more coordinated national response to the HIV epidemic [3]. Through that plan, 216 million dollars have been awarded to 90 community-based organizations nationwide to deliver effective HIV prevention to create strategies for those at greatest risk, including African-Americans and other people of color [2].

A strategy that has built off the efforts of the CDC’s National HIV/AIDS strategy is the United Nation’s program HIV/AIDS established in 2013, 90–90-90. The goal is that by 2020, 90% of people who are HIV Infected will be diagnosed, 90% of people who are diagnosed will be on antiretroviral treatment, and 90% of those who receive antiretroviral treatment will be virally suppressed [35]. This a global initiative that also funds the United States among other territories strongly affected by HIV/AIDS. Ambitious ground roots methods such as this will be vital to attacking this epidemic head on.

A new preventive effort for people that are at high risk to HIV/AIDS is Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [36]. Daily PrEP reduces the risk of contracting HIV from sex by more than 90% and among IDUs by more than 70% [36]. The usage of the PrEP technique has been advantageous when utilized by high risk groups such as MSM and if more readily used, could help reduce diagnoses among African-Americans at risk.

Williams, Wyatt, and Wingood discussed the “four Cs” of HIV prevention with African-Americans: 1) crisis, 2) condoms, 3) culture, and 4) community. They state that future HIV prevention strategies must move beyond education and condom availability and use, to removing the institutional and historical barriers that hinder HIV risk reduction behaviors [37]. William et al. devised the acronym ADAPITT (assess, decide, adapt, production, topic experts, integrate, train and test) to help determine if a prevention strategy in the African-American subpopulation would be effective in a specific target area. It is important that strategies be personalized for African-American populations in order to reduce the current disparities within the population. The strategies could go through a preliminary testing using the ADAPITT protocols to help predict the efficacy of the proposed effort in decreasing the incidence rates in the community.

As stated before, the African-American Church must also play a vital role in closing the HIV disparities gap. The African-American Church can most effectively produce change by: 1) Adapting Church-based prevention strategies developed for other African-American Subgroups, 2) providing prevention and referral services, 3) considering how scripture supports prevention efforts, and 4) emphasizing the tenets of liberation theology [27,38].

A community-based organization in New York City has developed a strategy aimed at reducing BMSM prevalence rates of HIV called the “Many Men, Many Voices (3MV)”. The 3MV program focuses on reducing sexual risk behaviors and increasing protective behaviors among BMSM. An important strategy for 3MV involves the use of small group education and interaction opportunities to increase knowledge and change attitudes and behaviors related to HIV/STD risk among BMSM [39] The increased utilization of these techniques could be what is needed in order to stop the growing rate of HIV/AIDS amongst BMSM. The community-based approach has also been utilized in Miami in order to increase testing rates among the population by providing a more direct approach to draw in the African-American community [40].

In their study, Hendrick and Canfield focused on African-American women under the age of 25. Their work involved efficacious interventions and included promoting gender and ethnic pride, HIV risk-reduction self-efficacy, and skills building. They found that the content must be tailored to the specific age, developmental period, and baseline behavioral characteristics of participants [41]. More work needs to be done developing new and innovative approaches as described above.

Conclusions

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the African-American community continues to be of crisis proportion. Since our report 10 years ago trends have continued, and in some regards have worsened. It is clear that much more needs to be done to address the fact that African-Americans continue to be overrepresented across all categories of transmission such as heterosexual contact, men that have sex with men, intravenous drug usage, incarceration, sexually transmitted disease, and other factors that have a direct correlation to HIV/AIDS diagnosis rate. While higher rates of poverty and prevalence of negative socio-economic determinants in African-Americans are important underlying factors, we believe that a concerted, re-dedicated effort (as can be seen with other national health emergencies such as opioid addiction) can create meaningful change in the decade to come. The understanding of the intersectionality between all of these factors is necessary to finding a solution to eradicate this epidemic.

Specifically, we believe the unavailability of access to HIV healthcare and testing in combination with cultural HIV/AIDS stigma has increased the rates of delayed diagnosis and treatment of the population. Homo-negativity in the African-American population must be addressed even further to stem the increasing incidence of HIV/AIDS among BMSM. Funding and resources need to be reallocated to address high risk regions such as the South and groups such as African-Americans and men that have sex with men more proportionally to the prevalence rates of those locations and groups. Lack of awareness and misinformation about HIV/AIDS must be addressed as well in order to combat the ongoing epidemic.

Lastly, what can the public health sector, medical professionals, and leaders that serve the African-American communities do? This has been a review of the multitude of factors that are responsible for the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The objective was to present the current status of HIV/AIDS and convey a basic understanding of the impacting issues that the African-American community faces daily. The CDC has implemented a strategy that has been advantageous to the population in general, but more needs to be done to reach the African-American community. Meeting people “where they are” and the implementation of more culturally appropriate solutions are the actions that have shown the greatest efficacy. There have been many advances in retroviral therapies, but they are of no use if they do not reach everyone who needs them. As community leaders: the public health sector, policy makers, public health practitioners, and other stakeholders need to address the issues of access, stigma, and the socio-economic factors that are underlying the disease, as well as encourage safe practices and testing in their patient population and the community at-large. The recommended action plan for those community leaders to impact the HIV/AIDS disparity is five-fold:

Immerse: Be out and active in African-American communities and participate in free or reduced cost testing in your area. Be aware of cultural norms in order to foster better and more trustworthy medical patient relationships.

Be non-judgmental: Work to eliminate prejudices and unconscious biases in treating patients.

Be knowledgeable: Understand new approaches to treatment, nuances in medications, and other issues related to HIV/AIDs.

Advocate: Speak out and call attention to this epidemic and its impact in the African-American community. Recruit other advocates for the effort to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the African-American community. Also work to eradicate secondary factors such as incarceration rates, poverty, STDs and other factors that increase the chances of contracting HIV through being an activist in the community.

Innovate: Society must continue to be proactive and create solutions that evolve with the times and the changing needs of the affected populations. New technology and techniques to help prevent or eradicate HIV/AIDS will be important to the effort to end the epidemic among African-Americans as well as the population at-large.

This must be an “all hands” effort. We are hopeful that with renewed vigor and re-dedication, the next ten years will demonstrate dramatic progress toward reversing this disease in the African-American community.

Figure 4.

Largest Categories for Affected Individuals by race and transmission influence.

Adapted from the CDC: HIV among African-Americans [1].

Figure 6.

Largest Categories for Affected Individuals by Sex and Transmission Influence in 2016.

Figure 7.

Largest Categories for Affected Individuals that are African-American by Sex and Transmission Influence in 2005.

Adapted from 2005 CDC Fact Sheet

References

- 1.African American | Gay and Bisexual Men | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html. Published February 15, 2018. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 2.January 31 CSH gov D last updated:, 2017. National HIV/AIDS Strategy: Updated to 2020. HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update. Published January 31, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 3.Humes Karen, Jones Nicholas, Ramirez Roberto R.. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010. March 2011. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 4.Laurencin CT, Christensen DM, Taylor ED. HIV/AIDS and the African-American community: a state of emergency. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HIV Survelliance Report Volume 28. February 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 6.HIV Survelliance Report Volume 17. June 2007. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2005_hiv_surveillance_report_vol_17.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 7.Women | Gender | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html. Published November 22, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 8.McCree DH. Changes in the Disparity of HIV Diagnosis Rates Among Black Women — United States, 2010–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6604a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Addressing the Needs of Black Women in HIV Prevention in the U.S. Infographic | AIDS Education and Training Centers National Coordinating Resource Center (AETC NCRC). https://aidsetc.org/resource/addressing-needs-black-women-hiv-prevention-us-infographic. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 10.Villarosa L. America’s Hidden H.I.V. Epidemic. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/06/magazine/americas-hidden-hiv-epidemic.html. Published June 6, 2017. Accessed February 22, 2018.

- 11.Male H. CDC Factsheet: HIV among African Americans. February 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-hiv-aa-508.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 12.Communities in Crisis: Is There a Generalized HIV Epidemic in Impoverished Urban Areas of the United States? | National Prevention Information Network. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/communities-crisis-there-generalized-hiv-epidemic-impoverished-urban-areas-united-states. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 13.Poverty | State of Working America. http://www.stateofworkingamerica.org/fact-sheets/poverty/. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 14.Flores A, López G, Radford J. Facts on U.S. Latinos, 2015. Pew Res Cent Hisp Trends Proj. September 2017. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2017/09/18/facts-on-u-s-latinos-trend-data/. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 15.STDs in Men Who Have Sex with Men - 2016 STD Surveillance Report. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/msm.htm. Published October 2, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 16.Washington TA, Robles G, Malotte K. Factors associated with HIV testing history among Black men who have sex with men (BMSM) in Los Angeles County. Behav Med Wash DC. 2013;39(3):52–59. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2013.779565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Factors Increasing HIV Risk | HIV Risk and Prevention Estimates | HIV Risk and Prevention | HIV/AIDS | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/estimates/riskfactors.html. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 18.Hughes JP, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Determinants of per-coital-act HIV-1 infectivity among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(3):358–365. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.STD Facts - HIV/AIDS & STDs. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hiv/stdfact-std-hiv.htm. Published October 4, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 20.Vlahov D, Robertson AM, Strathdee SA. Prevention of HIV Infection among Injection Drug Users in Resource-Limited Settings. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2010;50(Suppl 3):S114–S121. doi: 10.1086/651482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall BDL, Friedman SR, Monteiro JFG, et al. Prevention And Treatment Produced Large Decreases In HIV Incidence In A Model Of People Who Inject Drugs. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(3):401–409. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egea JM, Muga R, Sirera G, et al. Initiation, changes in use and effectiveness of highly active anti-retroviral therapy in a cohort of injecting drug users. Epidemiol Amp Infect. 2002;129(2):325–333. doi: 10.1017/S0950268802007495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) - Prisoners in 2016. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6187. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 24.Bose S. Demographic and spatial disparity in HIV prevalence among incarcerated population in the US: A state-level analysis. Int J STD AIDS. 2018;29(3):278–286. doi: 10.1177/0956462417724586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NAACP | Criminal Justice Fact Sheet. NAACP. http://www.naacp.org/criminal-justice-fact-sheet/. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 26.Despite Progress, Persistent Disparities Prolong HIV Epidemic Among African Americans News. AIDSinfo. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/news/1650/despite-progress--persistent-disparities-prolong-hiv-epidemic-among-african-americans. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 27.Expanded HIV Testing and African Americans | National Prevention Information Network. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/expanded-hiv-testing-and-african-americans. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 28.Oji VU, Hung LC, Abbasgholizadeh R, Terrell Hamilton F, Essien EJ, Nwulia E. Spiritual care may impact mental health and medication adherence in HIV+ populations. HIVAIDS Auckl NZ. 2017;9:101–109. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S126309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Kelly JA. The role of the Black Church in the lives of young Black men who have sex with men. Cult Health Sex. 2016;18(5):524–537. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1091509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulton BR. Black churches and HIV/AIDS: factors influencing congregations’ responsiveness to social issues. J Sci Study Relig. 2011;50(3):617–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson R, Moodie-Mills AC. HIV/AIDS Inequality: Structural Barriers to Prevention, Treatment, and Care in Communities of Color. Cent Am Prog. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/reports/2012/07/27/11834/hivaids-inequality-structural-barriers-to-prevention-treatment-and-care-in-communities-of-color/. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 32.Discrimination and inequality are fueling America’s AIDS crisis. MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/discrimination-and-inequality-are-fueling-americas-aids-crisis. Published August 10, 2014. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 33.Nugent P. Racial Identity. Psychology Dictionary. https://psychologydictionary.org/racial-identity/. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 34.Andrinopoulos K, Kerrigan D, Ellen JM. Understanding Sex Partner Selection From the Perspective of Inner-City Black Adolescents. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/journals/psrh/2006/understanding-sex-partner-selection-perspective-inner-city-black. Published September 6, 2006. Accessed April 4, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Gray G. HIV, AIDS and 90–90-90: what is it and why does it matter? The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/hiv-aids-and-90-90-90-what-is-it-and-why-does-it-matter-62136. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- 36.PrEP | HIV Basics | HIV/AIDS | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prep.html. Published March 23, 2018. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- 37.Williams JK, Wyatt GE, Wingood G. The four Cs of HIV prevention with African Americans: crisis, condoms, culture, and community. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):185–193. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0058-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeffries WL, Sutton MY, Eke AN. On the Battlefield: The Black Church, Public Health, and the Fight against HIV among African American Gay and Bisexual Men. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2017;94(3):384–398. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0147-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evidence-Based HIV/STD Prevention Intervention for Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6301a5.htm. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- 40.Kenya S, Okoro I, Wallace K, Carrasquillo O, Prado G. Strategies to Improve HIV Testing in African Americans. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care JANAC. 2015;26(4):357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.HIV Risk-Reduction Prevention Interventions Targeting African American Adolescent Women | SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40894-016-0036-x. Accessed February 15, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]