Abstract

The adverse impact of racial discrimination on youth, and particularly its impact on the development of depressive symptoms, has prompted attention regarding the potential for family processes to protect youth from these erosive effects. Evidence from non-experimental studies indicates that protective parenting behavior which occurs naturally in many Black families can buffer youth from the negative impact of racial discrimination. Of interest is whether “constructed resilience” developed through family-centered prevention programming can add to this protective buffering. The current paper examines the impact of constructed resilience in the form of increased protective parenting using 295 families randomly assigned either to a control condition or to the Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) program, a familybased prevention program previously shown to enhance protective parenting. We found that baseline racial discrimination was predictive of change in youths’ depressive symptoms across the pre-post study period. Second, we found that parents participating in ProSAAF, relative to those randomly assigned to the control group, significantly improved in their use of an intervention targeting protective parenting behavior (PPB). Third, we found a significant effect of change in PPB on the association of discrimination with change in depressive symptoms. Finally, we found that ProSAAF participation buffered the impact of racial discrimination on change in depressive symptoms through change in PPB. Results provide experimental support for constructed resilience in the form of change in PPB and call for increased attention to the development of family-based intervention programs to protect Black youth from the pernicious effects of racial discrimination.

Keywords: racial discrimination, protective parenting, buffering, depressive symptoms, family-based intervention

Over 10 million Black Americans live in the rural Southern counties collectively referred to as “the Black Belt,” one of the most economically disadvantaged regions of the United States (Semega et al., 2017), and the area from which the sample for the current investigation is drawn. This region has substantially elevated poverty and unemployment rates relative to the U.S. as a whole (Carl Vinson Institute of Government, 2003; Probst et al., 2002), as well as entrenched oppressive social structures that lead to frequent experiences of racial discrimination (Cutrona et al., 2016; Tickamyer & Duncan, 1990; Williams et al., 2003). For Black youth, the result is frequent experiences of racial discrimination, and elevated feelings of threat and intimidation. The vast majority of Black youth will experience racial discrimination from multiple sources as they enter adolescence (Greene et al., 2006; Priest et al., 2018), with nearly all Black youth reporting one or more discriminatory incidents in the past year (Brody et al., 2006; Seaton et al., 2008). Similarly, racial microaggressions are reported to occur multiple times per day, on average (English et al., 2020). Accordingly, experiences of discrimination provide an important, negative developmental context for Black youth.

Not surprisingly, a considerable body of research suggests that experiences of racial discrimination have an adverse impact on the well-being of Black youth (Benner et al., 2018; Finch et al., 2000; Greene et al., 2006) with greater racial discrimination predicting significantly greater anxiety and depressive symptoms (English et al., 2014; Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, 2009; Sellers et al., 2006). Longitudinal designs also confirm this association, suggesting that perceived racial discrimination predicts increases in depressive symptoms over time (Brody et al., 2006; English et al., 2014). Associations between racial discrimination and mental health may be exacerbated when individuals who experience racial discrimination come to believe and internalize the messages of inferiority they receive about their group (David et al., 2019). This association may be particularly relevant for Black youth in the rural South for whom implicit biases of teachers and authority figures may often lead to greater expectations of problem behavior among Black youth (Gilliam et al., 2016). Poor mental health of Black youth in response to experiences of discrimination in the rural South may also be amplified by racismrelated experiences and vicarious exposures such as witnessing racially discriminatory experiences in social media as well as within their community (e.g., police brutality, racial profiling) that occur with disturbing frequency.

Given racial discrimination’s toxic effects on Black youth (Geronimus et al., 2006; Goosby et al., 2018) and its potential to lead to elevated depressive symptoms and additional downstream consequences for health and health behavior (Carter et al., 2019; Zapolski et al., 2016), there is a substantial need for models to guide preventive intervention efforts to better protect youth. One potential source of protection may be that provided by families in the form of protective parenting practices that counter negative messages conferred by racial discrimination and instead suggest that youth are valuable, protected, and worth protecting (Brody et al., 2006). Focusing on the role of protective parenting in preventing depressive symptoms and substance use, Zapolski et al. (2016) identified supportive parenting as a critical protective factor while also noting that protective parenting may be somewhat different for African American families than for Whites given that it evolved to protect Black youth in a uniquely harsh environment. Supporting the expectation that protective parenting may counter the impact of discrimination, Brody and colleagues (2014) found that although perceived racial discrimination predicted later physiological effects among Black youth, this effect was not observed for those receiving more supportive parenting. Likewise, Brody and colleagues (2006) reported that supportive parenting reduced the negative impact of racial discrimination on African American youths’ depressive symptomatology and conduct problems. The protective effect of parental support may also extend to other negative emotions, with parental support buffering the effect of perceived racial discrimination on both feelings of anger and willingness to engage in negative health behavior in response to racial discrimination (Gibbons et al., 2010). These findings highlight the potential importance of increasing protective parenting practices in the context of discriminatory environments as a way to prevent harmful effects of discriminatory experiences on youths’ mental health and well-being.

The current study uses data from the Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) intervention trial to experimentally test the buffering effect of constructed resilience in the form of protective parenting. Resilience theory (Luthar, 2006) suggests that not all Black youth confronting adverse circumstances will experience negative outcomes. Constructed family resilience posits that family practices associated with resilience can be shared more broadly (i.e., constructed through preventive intervention programs) to reduce the negative impact of adverse community conditions. ProSAAF is a family-centered preventive program designed to promote positive family relationships and interactions among African American couples and their early adolescent children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods in the rural South (see Barton et al., 2018). The ProSAAF program consists of six weekly, 2-hour meetings in which parents and their child participate. Content is provided using videotapes which structure couple and youth activities, depict positive relationship processes, describe ways to deal with daily hassles and burdens, and promote communication skills (particularly active listening). Additionally, protective parenting behavior is discussed, including increased communication with youth about their activities, friends, and plans, establishing rules, and providing positive messages affirming youth Black identity. Prior analyses found that participation in the ProSAAF intervention enhanced couple functioning and co-parenting (Barton et al., 2017; Barton et al. 2018; Lavner et al., 2019) and also had indirect beneficial effects on child outcomes (Lavner et al., 2020; Lei & Beach, 2020), albeit not depressive symptoms. However, the ability of program-induced changes in protective parenting behavior (PPB) to buffer the impact of racial discrimination on youth depressive symptoms was not tested.

Examining the buffering effects of PPB in the context of intervention trials can be useful in testing whether it is indeed a mechanism of resilience. Because differential change in PPB across conditions can be ascribed to the effect of the experimental manipulation, to the extent that change in PPB buffers the impact of discrimination, this provides a sensitive index of the causal, buffering impact of ProSAAF. Simple assignment to condition in a family-based intervention is ambiguous with regard to mechanism, and so does not provide a sensitive test of the buffering potential of PPB. Accordingly, we use a test of “indirect moderation” to examine the connection between ProSAAF, change in PPB, and the resulting buffering of the association of discrimination and depressive symptoms. This allows us to trace the causal flow from ProSAAF to change in PPB and ultimately to buffering of the relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms.

The current study also expands upon prior work by examining two-parent Black households and the impact of both parents’ behavior for youth outcomes. A previous nonexperimental study of the buffering effect of protective parenting focused primarily on parenting in the context of single-mother-headed households (Brody et al., 2006). For at least part of their adolescence, however, a substantial proportion of African American youth will live in a household with two parents (Jayakody & Kalil, 2002), making this an important, but understudied context of supportive parenting effects on youth. A focus on single-mother-headed households has led to a dearth of information that can guide the development of programming designed to enhance protective parenting in two-parent African American families, particularly information that is relevant to youth entering the age of risk for increased depressive symptoms.

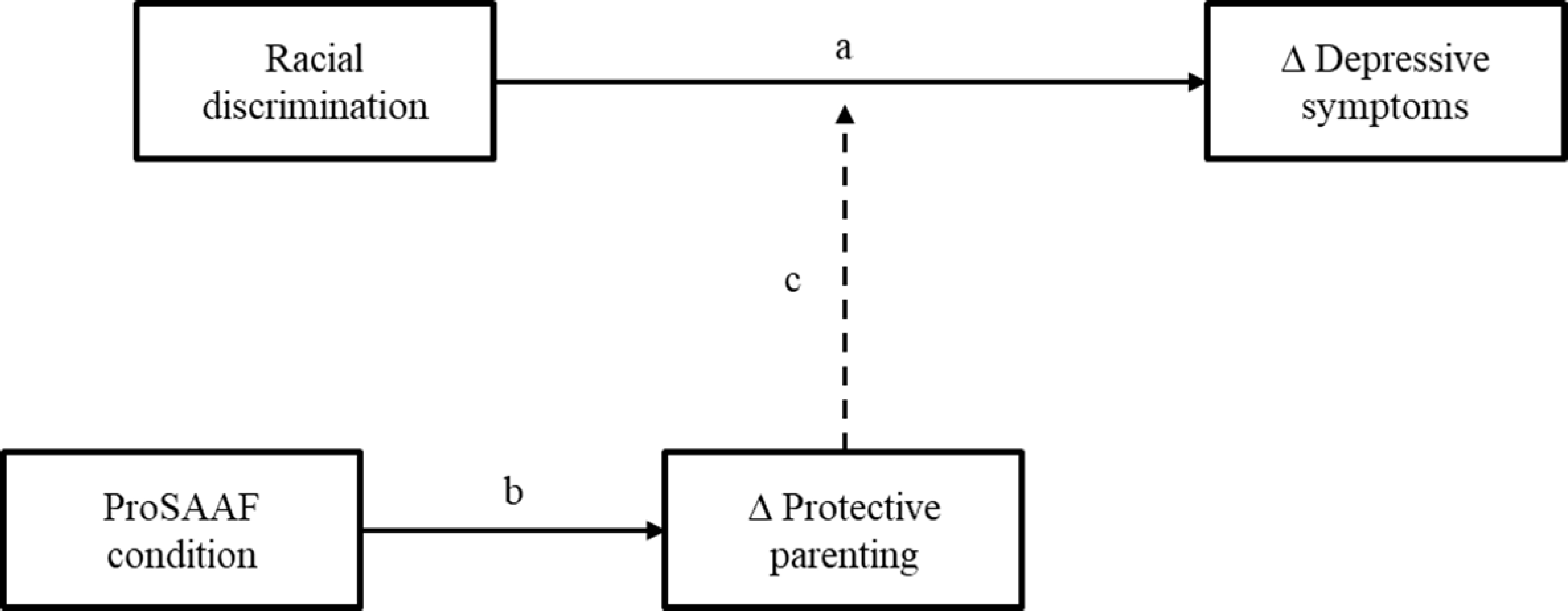

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical model guiding the present study. We tested a series of two preliminary hypotheses and two primary hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model showing mediated moderation effects of ProSAAF on the relationship between racial discrimination and change in youth depressive symptoms through changes in protective parenting.

Note. Δ = change in a variable from pre-test to post-test.

Preliminary Hypotheses:

H1: Consistent with prior literature, greater experience of racial discrimination at baseline will forecast significantly greater increases in depressive symptoms from pre- to post- intervention (Pathway a).

H2: Parents assigned to the ProSAAF intervention will increase their use of protective parenting behavior (PPB) significantly more than those assigned to the control condition (Pathway b).

Primary Hypotheses:

H3: Change in protective parenting behavior (PPB) will buffer the effect of racial discrimination on change in youth depressive symptoms (Pathway c).

H4: There will be a significant indirect moderating effect of ProSAAF on the association between racial discrimination and changes in youth depressive symptoms through its effect on PPB (Pathways b and c).

Method

Sample

This study used data from the Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) project, a randomized controlled trial to promote strong family relationships in African American families with an adolescent child living in low-income neighborhoods in the Southern US (full study overview is provided in Barton et al., 2018). The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board at The University of Georgia (Review board approval number: 2012104112). Details of the participants’ progress through baseline and post-test are illustrated in the CONSORT in flowchart in Supplemental Figure S1. Subject enrollment began in 2013 and continued into 2014. Through school lists and advertisements, we recruited 1,897 families with an African American child between the ages of 9 and 14 years from small towns and communities in the Southern US. Of these, 1,145 families were not eligible for participation because the child was in a single-parent household, the family was enrolled in another program, the child was not within the specified age range, the child had a sibling/stepsibling in the same grade, or the child did not identify as African American. In addition, 347 families declined to participate, and 59 families were unable to schedule an assessment. In total, data at baseline were collected from 346 families, and they were randomly assigned to the intervention (n = 172) or control (n = 174) condition. Additional details regarding recruitment are described by Barton, Beach, and colleagues (2018).

Of the randomized sample, 63% were married, with an average marital duration of 9.7 years. Unmarried couples had been living together for 6.73 years. At baseline, the female caregiver’s mean age was 36.51 years and the male caregiver’s mean age was 39.89 years. Children’s mean age was 10.87 (SD = 0.90); 54% were boys (n = 186). The majority of families in the study could be classified as working poor: 51% had incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level and an additional 17% had incomes between 100% and 150% of that level. Median monthly income was $1,375 (SD = $1,375; range $1 to $7,500) for men and $1,220 (SD = $1,440; range $1 to $10,000) for women.

The post-intervention assessment took place an average of 9.4 months after the baseline. The current study focuses on the 295 youth participants (162 boys and 133 girls) for whom data were available on all study measures at baseline and post-test assessment.1 The mean age for youth was 12.08 years at the post-test assessment. Of the 295 families, 49.2% had two biological parents, 39% had a biological mother and stepfathers/adoptive father, and 7.1% had a biological mother and a stable romantic partner in the home for more than 1 year. The other families were six grandparent families, eight adoptive parents, and an aunt and uncle.

ProSAAF Program and Control Group

The Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) program was informed by cognitive-behavioral (CBT) approaches to the prevention of couple and family problems (e.g., Stanley et al. 1999) adapted to meet the needs of two-parent African American families residing in economically stressed regions of the rural South, as well as by the SAAF parenting program designed to be applicable to rural African American families (Brody et al., 2004). Each session was designed to focus on a specific stressor that rural African American couples experience (e.g., work, racism, finances, extended family), and to introduce techniques for handling the stressor together in mutually supportive and effective ways. There was also a focus on enhancing coparenting, with sample coparenting/parenting issues including empathy with children, discipline, and supporting children. Youth issues included empathy with parents, resisting temptation, and qualities of good friends; and parent-child issues included understanding each other, effective communication, and working together. In this context, protective parenting behavior was discussed and encouraged on multiple occasions, with particular attention to increased communication with youth about their activities, friends, and plans, establishing rules, and encouragement to provide positive messages affirming youth Black identity.

ProSAAF implementation.

A trained African American facilitator visited the family in their home for six consecutive weeks to conduct each 2-hour intervention session. All facilitators were married, middle-aged Black Americans from participants’ local communities who had received 40 hours of training in program content, facilitation, and delivery methods, and adherence to the program manual. The first 60 minutes of each session focused on the couple’s relationship. The next 30 minutes of each session focused on parenting/coparenting topics. The facilitator then met with the target child for 15 minutes to discuss a youth-focused topic while the couple took a break in a different room. After the youth activity, the entire family met with the facilitator for a 15-minute family activity, such as a discussion or a game. This session structure was modeled after the Strengthening Families Program (Kumpfer et al., 1996).

Following each intervention session, each adult was compensated for their time (Sessions 1 and 2 = $25, Sessions 3 and 4 = $30, Sessions 5 and 6 = $35). A total of 28 facilitators implemented the program; the total number of families with whom each facilitator worked ranged from 1 to 15.

Attendance.

Of the 172 families assigned to the intervention condition, 81% (n = 139) completed all six sessions. Total sessions attended by remaining families were as follows: 5 sessions, 0.6% (n = 1); 3 sessions, 2.9% (n = 5); 2 sessions, 2.3% (n = 4); 1 session, 4.1% (n = 7); and no sessions, 9.3% (n = 16). Sessions were attended by all family members.

Fidelity.

All sessions were audiotaped to allow implementation to be monitored. A sample of sessions (n = 220, corresponding to 25% of all project sessions) was coded using an 87- to 143-point checklist (depending on the session) for fidelity to intervention guidelines. All facilitators were assessed at least once. Of the 220 sessions reviewed, 10% (n = 22) were coded by more than one rater (ICC = .94). The mean fidelity score across facilitators on a scale of 0100% was 91% (SD = 9.0%).

Control group.

Youth in the control group were assessed on the same schedule as those in the intervention group, thereby controlling for effects of repeated measurements, maturation, individual differences, and external social changes.

Measures

Racial Discrimination

Youths’ experiences of perceived racial discrimination were assessed at baseline using 9 items from the daily life experiences subscale of the Racism and Life Experiences Scale (Harrell, 2007), which asks participants to report the frequency with which they experienced several racial stressors over the last 6 months (sample items: “Have you been treated rudely or disrespectfully because of your race?” “Have you been called a name or harassed because of your race?”) using a four-point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = a few times, 4 = frequently). Responses were summed such that higher scores indicated higher levels of racial discrimination. Cronbach’s alpha was .85 at baseline.

Depressive Symptoms

Youths’ reports of depressive symptomatology in the past week were assessed at baseline and at post-test using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977; sample items: “how often did you feel depressed?” “How often did you have crying spells?”). Response options ranged from 0 (Rarely or none of the time [0–1 days]) to 3 (Most or all of the time [6–7 days]). Items were summed such that higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms (M = 13.24, SD = 7.51 at baseline; M = 13.10, SD = 7.95 at posttest); a score of 16 or greater is often used to indicate clinically significant depressive symptoms. The correlation between baseline and posttest depressive symptoms was .58, p < .001. Cronbach’s alpha was .75 at baseline and .78 at posttest.

Protective Parenting Behavior (PPB)

At baseline and at post-test, the caregivers completed a 8-item scale assessing a range of protective parenting behaviors specifically targeted in the intervention, including items assessing the extent to which each parent asks the child what they will be doing, where they will go, who they will be with, when they will get home, checks on them when they are out, discusses house rules, enforces house rules, and reminds them of why they should be proud of being African American. Ratings for these items ranged from 0 (Never) to 4 (All of the time). The same items were reworded so that the target child could use this 8-item scale to rate the protective parenting behavior of their caregivers. The caregiver and child-report items were averaged within a family (i.e., youth, both caregivers’ reports) to create a family-level scale with a theoretical range of 0 to 4 (M = 2.97, SD = .54, range 1.53 to 3.97 at baseline; M = 3.11, SD = .53, range 1.13 to 4.00 at posttest). The correlation between baseline and posttest PPB scores was .48, p < .001. Cronbach’s alpha was .86 at baseline and .85 at posttest.

Control Variables

Because of their potential associations with parenting behavior and youth depressive symptoms, or potential to influence response to intervention, our analysis also included controls for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics including youth sex (male = 1; female = 0), youth age at baseline, married-parent families at baseline (married = 1; unmarried families = 0), parental education at baseline (high school or above =1; less than high school = 0), the number of children living at home at baseline, and financial stress at baseline. Financial stress (Conger & Elder, 1994) was reported at baseline by caregivers and assessed using four items (sample item: “During the past 12 months, my family has not had enough money to afford the kind of home we need?”), which were rated on a 4-point scale (1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree). Items were summed/averaged, with higher scores reflecting more financial stress. Cronbach’s alpha was .82.

Equivalence of Intervention and Control Groups

Intervention and control participants did not significantly differ at baseline in any of the variables under examination here (all p > .05; see Supplemental Table S2).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Associations

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations for the study variables. Consistent with hypotheses, there was a significant correlation of baseline experiences of racial discrimination with change in depressive symptoms, r = .13, p = .02. Likewise, participation in the ProSAAF intervention was positively associated with change in protective parenting behavior (PPB) from baseline to post-test, r = .16, p < .01. Youth age was associated with change in PPB, and other control variables were associated with each other and with youth age. Youth sex was not associated with primary study variables or with other control variables.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations among the Study Variables (N = 295)

| Variable or statistic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Δ Depressive symptoms | — | |||||||||

| 2. Racial discrimination | .13* | — | ||||||||

| 3. Δ PPB | −.09 | −.03 | — | |||||||

| 4. ProSAAF intervention | −.04 | −.07 | .16** | — | ||||||

| 5. Youth sex (1 = male) | −.11† | .05 | −.04 | −.10† | — | |||||

| 6. Youth age | .01 | −.01 | −.12* | −.02 | −.02 | — | ||||

| 7. Financial stress | −.01 | .04 | −.02 | .04 | −.03 | .12* | — | |||

| 8. Married-parent families | .06 | −.03 | .04 | .08 | −.04 | .03 | −.22** | — | ||

| 9. Number of children | .08 | .03 | .04 | .08 | .05 | .05 | .11† | −.06 | — | |

| 10. Parental education | −.05 | −.01 | −.03 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | −.07 | .14* | .10 | — |

| Mean | .00 | 1.51 | .00 | .48 | .55 | 11.31 | 11.35 | .63 | 2.94 | .89 |

| SD | 6.49 | .55 | .47 | .50 | .50 | .86 | 2.50 | .48 | 1.49 | .31 |

Note. Δ = change in a variable from pre-test to post-test; PPB = Intervention targeted protective parenting behavior.

p ≤ .10

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01 (two-tailed tests).

We next proceeded to test the four hypotheses outlined above. For all analyses, we utilized Mplus 8 to test OLS regressions, the path modeling, and indirect moderation models. To assess goodness-of-fit, chi-square statistics, and Steiger’s root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .05) were used. We calculated change scores (Δ) for study variables using the residuals from the regression of post-test score on baseline scores. To assess the significance of indirect moderation effects, the 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated using bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping with 1,000 resamples.

H1: Racial Discrimination at Baseline will Predict Change in Depressive Symptoms

To better examine the longitudinal effect of youths’ experiences of perceived racial discrimination on their change in depressive symptoms, we examined the association of racial discrimination with regressed change in depressive symptoms both with and without entering control variables. As shown in Table 2, the first model examined the effect of racial discrimination on change in depressive symptoms without control variables. Results indicated that the main effect of racial discrimination at baseline was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms (β = .13, p = .045), but intervention condition was not. It is also noteworthy that the interaction between ProSAAF and racial discrimination on change in depressive symptoms also was not significant (β = −.01, p = .99, not shown in Table 2). However, recent studies (see O’Rourke and MacKinnon, 2018) have indicated that this does not rule out a possible significant indirect or indirect moderating effect, as these may be present even in the absence of a significant intervention effect on dependent variables. Because intervention programs are typically concerned with mediational mechanisms on an a priori basis and have theoretically specified models detailing the way in which intervention is thought to produce its effects, it is informative to examine moderating effects of hypothesized mediators to better characterize intervention effects (see O’Rourke and MacKinnon, 2018). Model 1B added control variables. The effect of discrimination remained significant (β = .14, p = .038), indicating that an increase of one standard deviation in perceived discrimination at baseline was associated with an increase of .14 standard deviation units in youth depressive symptoms from baseline to post-test.

Table 2.

Regression Models Examining Racial Discrimination and ProSAAF as Predictors of Change in Youth Depressive Symptoms and Protective Parenting Behaviors (PPB) (N = 295)

| Δ Depressive symptoms |

Δ PPB |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A |

Model 1B |

Model 2A |

Model 2B |

|||||

| Variables | b | β | b | β | b | β | b | β |

| Racial discrimination | 1.55* | .13 | 1.60* | .14 | −.02 | −.02 | −.02 | −.02 |

| (.77) | (.77) | (.05) | (.06) | |||||

| ProSAAF intervention | −.44 | −.03 | −.75 | −.06 | .15** | .16 | .14** | .15 |

| (.75) | (.78) | (.05) | (.05) | |||||

| Youth sex (1 = male) | −1.67* | −.13 | −.03 | −.03 | ||||

| (.78) | (.05) | |||||||

| Youth age | .06 | .01 | −.06* | −.12 | ||||

| (.40) | (.03) | |||||||

| Financial stress | −.04 | −.02 | −.00 | −.01 | ||||

| (.16) | (.01) | |||||||

| Married-parent families | .94 | .07 | .04 | .04 | ||||

| (.82) | (.06) | |||||||

| Number of children | .38 | .09 | .01 | .04 | ||||

| (.26) | (.02) | |||||||

| Parental education | −1.05 | −.05 | −.06 | −.04 | ||||

| (1.25) | (.10) | |||||||

| Constant | −2.13† | −2.13 | −.04 | .70† | ||||

| (1.21) | (5.29) | (.09) | (.37) | |||||

| R-square | .02 | .05 | .03 | .05 | ||||

Note: Unstandardized (b) and standardized (β) coefficients shown, with robust standard errors in parentheses.

p ≤ .10

p ≤ .0

p ≤ .01 (two-tailed tests).

H2: ProSAAF will Increase Protective Parenting Behavior

To better examine the effect of ProSAAF intervention on change in protective parenting behavior (PPB) from baseline to post-test, we examined the association of the ProSAAF intervention condition vs. control with regressed change in PPB both with and without entering control variables. As shown in Model 2A in Table 2, there was a significant effect of ProSAAF on change in PPB (β = .16, p < .01) in the model without control variables. Model 2B added control variables and indicated that the ProSAAF intervention program had a significant positive effect on change in PPB from baseline to post-test (β = .15, p < .01) with these controls, such that families in ProSAAF intervention showed significant increases in protective parenting behavior from baseline to post-test compared to those who did not receive the program.

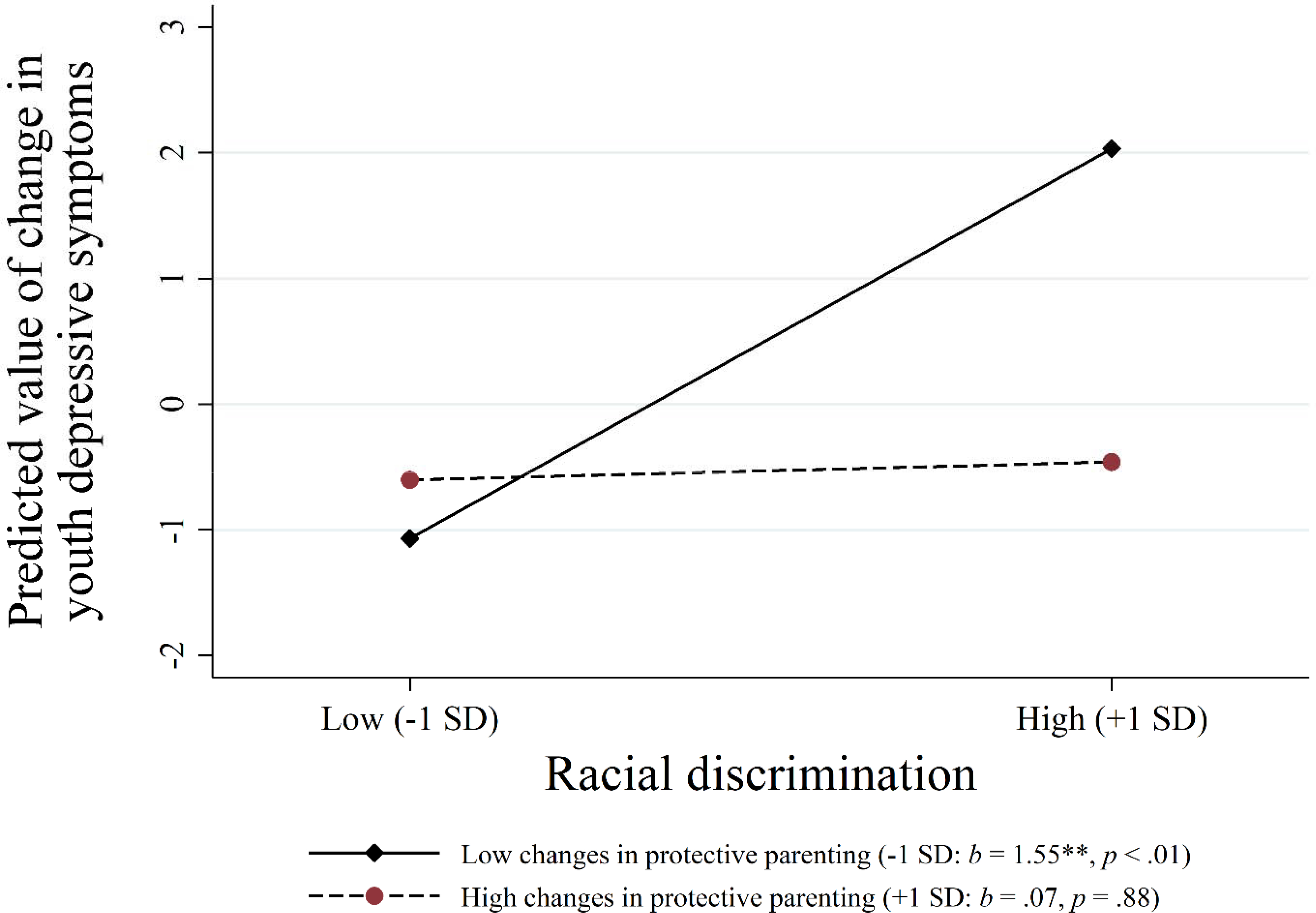

H3: Change in Protective Parenting Behavior Will Buffer the Effect of Racial Discrimination on Change in Youth Depressive Symptoms

Turning to the third hypothesis, an OLS regression was used to test the buffering effect of change in protective parenting behavior on change in youth depressive symptoms. As can be seen in Model 1 of Table 3, the effect of racial discrimination at baseline on change in depressive symptoms was significant (β = .14, p = .03), and the effect of change in PPB on change in depressive symptoms was not significant (β = −.10, p = .09). To test the buffering hypothesis, Model 2 added the multiplicative interaction term of racial discrimination at baseline by change in PPB. The analysis shows the hypothesized interaction (β = −.12, p = .01), which Figure 2 illustrates. The graph and simple slope analysis showed that the effect of racial discrimination on increase in youth depressive symptoms from baseline to post-test was positive and significant among those youth whose parents showed weaker changes in protective parenting behavior (b = 1.55, p < .01) but was not significant among those with greater increases in protective parenting behavior (b = .07, p = .88). High and low change in PPB are defined as one standard deviation (SD) above the sample mean and one SD below the sample mean.

Table 3.

Regression Models Examining the Effects of Racial Discrimination and Change in Protective Parenting Behaviors on Change in Depressive Symptoms (N = 295)

| Δ Depressive symptoms |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

| Variables | b | β | b | β |

| Racial discrimination | .88* | .14 | .81* | .12 |

| (.41) | (.40) | |||

| Δ PPB | −.62† | −.10 | −.51 | −.08 |

| (.37) | (.36) | |||

| Racial discrimination × Δ PPB | −.74* | −.12 | ||

| (.30) | ||||

| ProSAAF intervention | −.62 | −.05 | ||

| (.76) | ||||

| Youth sex (1 = male) | −1.65* | −.13 | −1.70* | −.13 |

| (.76) | (.77) | |||

| Youth age | −.01 | −.01 | .07 | .01 |

| (.41) | (.41) | |||

| Financial stress | −.05 | −.02 | −.04 | −.01 |

| (.16) | (.16) | |||

| Married-parent families | .94 | .07 | .99 | .07 |

| (.83) | (.83) | |||

| Number of children | .38 | .09 | .40 | .09 |

| (.25) | (.25) | |||

| Parental education | −1.13 | −.05 | −1.16 | −.06 |

| (1.25) | (1.24) | |||

| Constant | .89 | .10 | ||

| (5.28) | (5.40) | |||

| R-square | .05 | .07 | ||

Note: Unstandardized (b) and standardized (β) coefficients shown with robust standard errors in parentheses. Δ = change in a variable from pre-test to post-test; PPB = Intervention Targeted protective parenting behavior; racial discrimination and Δ PPB are standardized by ztransformation (mean = 0 and SD = 1).

p ≤ .10

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01 (two-tailed tests).

Figure 2.

Effects of racial discrimination on changes in youth depressive symptoms at different levels of changes in protective parenting behavior.

Note: The lines represent the regression lines for different levels of a moderator (low: 1 SD below the mean; high: 1 SD above the mean). Numbers in parentheses refer to simple slopes. * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01 (two-tailed tests), N = 295.

H4: ProSAAF Indirectly Moderates the Association Between Racial Discrimination and Changes in Depressive Symptoms through Increasing Protective Parenting Behavior

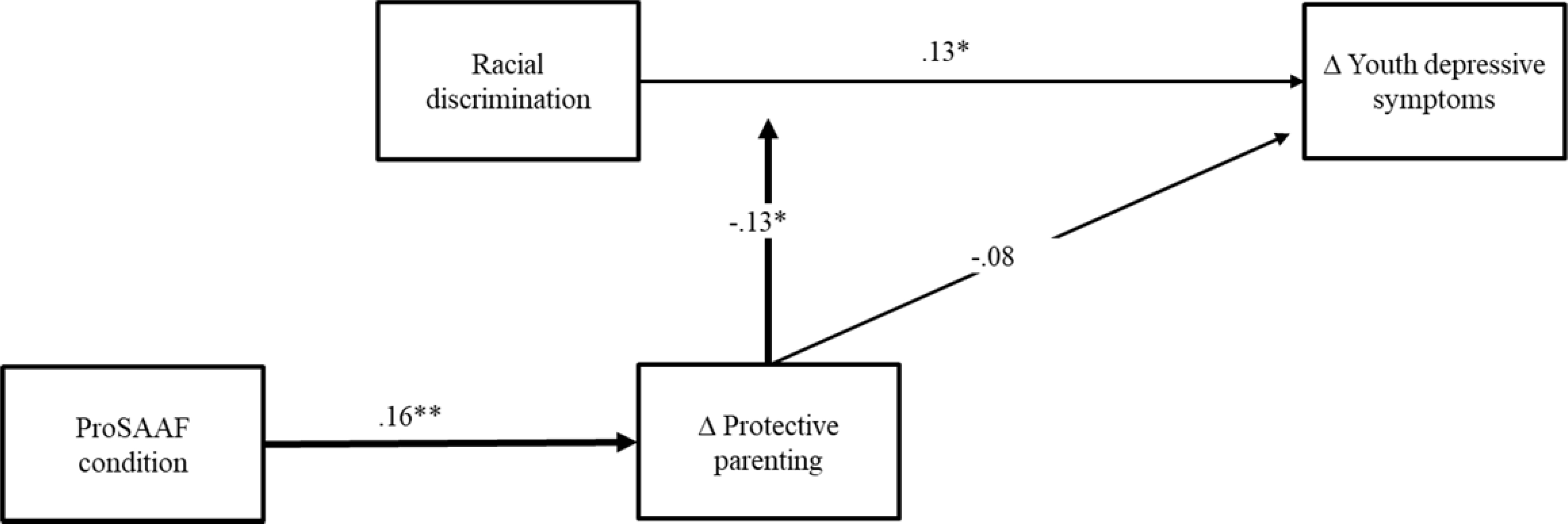

To test indirect moderating effects, we used path modeling with interaction effects. As shown in Figure 3, the various fit indices were good for our hypothesized model. Consistent with the previous hypotheses, ProSAAF was associated with a significant change in protective parenting behavior (β = .16, p < .01), which in turn buffered the effect of racial discrimination on change in youth depressive symptoms (β = −.13, p = .02). Further, as hypothesized, using a bootstrapping method with 1,000 replications, we found that the indirect moderating effect was significant (indirect effect = −.24, 95% CI [−.58, −.06]), suggesting that ProSAAF indirectly buffered against racial discrimination’s effects on change in youth depressive symptoms through its effect on change in PPB. That is, change in PPB emerged as a mechanism by which ProSAAF participation could result in greater protection from discrimination.

Figure 3.

ProSAAF indirectly moderates the effects of racial discrimination on change in youth depressive symptoms through changes in protective parenting.

Note: χ2 = 11.32, df = 15, p = .73, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00. Δ = change in a variable from pretest to post-test. Values are standardized parameter estimates. Child’s sex, child’s age, financial stress, married-parent families, number of children, and parental education are controlled but now shown in the figure. The bold lines indicate that the indirect effect is significant.

* p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01 (two-tailed tests), N = 295.

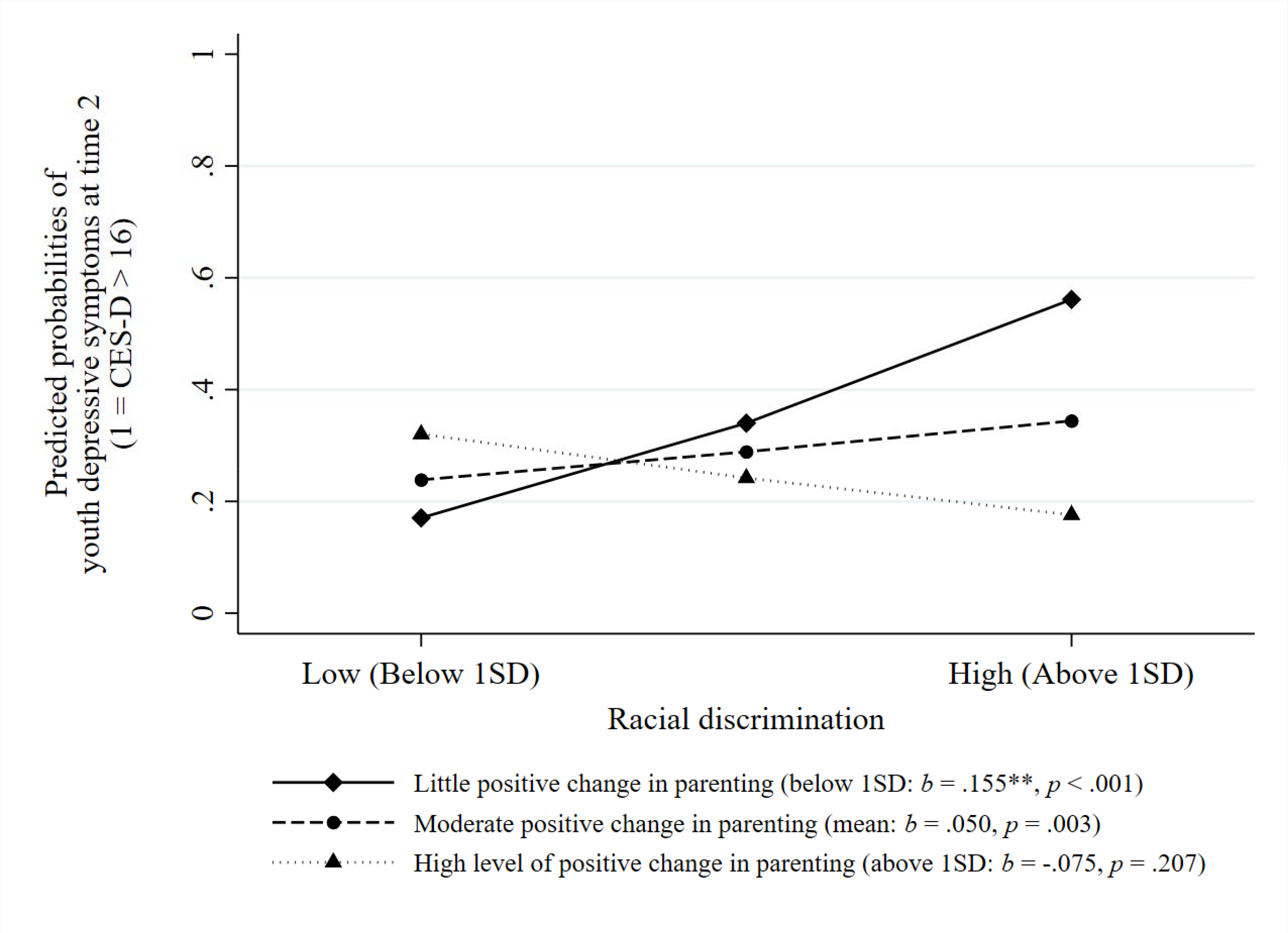

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of these findings. First, one component of PPB relates to racial socialization. Our measure included an item asking how often parents remind their child why they should be proud to be Black. To ensure that this item was not driving observed effects, we repeated all analyses excluding this item. The results showed no change in the pattern of results (see Supplemental Figure S2). Second, to better characterize the clinical significance of observed effects, we re-estimated models in a logistic regression framework using CES-D > 16 to identify youth with clinically significant depression. This revealed that about 30 percent of the participants at post-test had CES-D scores at or above 16. As shown in Figure 4, the pattern of results was identical to that depicted in Figure 2. Finally, to test for any potential differences in the impact of parenting on youth outcomes between married-parent and unmarried parent dyads, we conducted a multiple group analysis in SEM directly comparing model fit when sub-samples were constrained to have all paths to be equal between those with married-parent and unmarried parent dyads vs. an alternative model that allowed all paths to differ. To determine which paths were different, we freed one path in the constrained model at a time and compared it with the constrained model’s chi-square with one degree of freedom. As shown in Supplemental Table S3, no paths were significantly different for married-parent families versus unmarried families, indicating that these patterns are similar regardless of parents’ marital status.

Figure 4.

Effects of racial discrimination on depression at time 2 (measured by CES-D greater than 16) at different levels of change in protective parenting behavior.

Note: The lines represent the regression lines for different levels of a moderator (low: 1 SD below the mean; moderate: mean; high: 1 SD above the mean). Beta coefficients indicate simple slopes. The logit model is used to model a dichotomous CES-D variable. The model controls for depression at time 1. * p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01 (two-tailed tests), N = 295.

Discussion

Racial discrimination has serious consequences for Black youth, and indeed serious consequences across the lifespan. The current results suggest that Black youths’ experiences of racial discrimination are linked to depressive symptoms that could include reactions of sadness and hopelessness in the face of seemingly insurmountable oppression. Our findings align with previous research indicating that experiences of racial discrimination can negatively impact the psychological well-being of Black youth (e.g., Benner et al., 2018; English et al., 2014). Metaanalytic reviews on racial discrimination and psychological well-being have found that the effects of racial discrimination on psychological distress are larger for youth than they are for adults (Lee & Ahn, 2013; Schmitt et al., 2014). Researchers theorize that a reason for these findings may be that youth have acquired fewer resources and strategies to cope with racial discrimination in comparison to adults.

Given the widespread and pernicious effects of racial discrimination, it is particularly important to identify modifiable protective processes that can be used to decrease vulnerability among racial and ethnic minority youth. As youth develop, parents play a critical role in how youth conceptualize experiences of racial discrimination through their communication and knowledge about Black identity (Anderson et al., 2015; Simons et al., 2002). Scholars have called for more rigorous research on Black families in the context of a racialized society that does not narrowly focus on urban, low-income single mothers (Murry, 2019; Murry et al., 2018). Furthermore, researchers note the importance of amplifying the strengths and protective processes within Black families that can serve as useful tools in daily oppressive contexts. The ProSAAF intervention utilized in this study emphasized buffering mechanisms that promote resiliency in Black families, particularly protective parenting behavior (PPB), with results indicating that parents participating in ProSAAF reported increases in PPB relative to control parents. These strategies are important because they can help Black youth to engage with parents in discussions that involve both messages of racial pride and the importance of safety and preparation for living in a society that frequently produces devaluing messages during an important development period.

We also examined whether increases in PPB buffered youth from the harmful effects of discrimination on changes in depressive symptoms. Survey samples and some intervention studies have indicated that protective parenting processes may buffer the effect of discrimination on depression, but conclusions from these studies are typically weakened by their correlational, and often cross-sectional, design. This leaves the observed buffering effect of protective parenting open to alternative explanations. To our knowledge, no prior research has experimentally examined the moderating effect of constructed protective parenting resources on the lagged association between discrimination and changes in depressive symptoms among rural African American youth. Longitudinal intervention designs, like the one used in the current investigation, overcome some of these limitations and allow us to provide more compelling support for hypothesized buffering effects. We show that ProSAAF promoted resilience in youth by increasing protective parenting, which in turn reduced the effect of discrimination on changes in their depressive symptoms. Because depressive symptoms may have a variety of other downstream and lagged effects, it will be important to further examine the extent to which constructed resilience lasts over time and its ability to inhibit the development of other negative outcomes thought to result from chronic exposure to racial discrimination.

The clinical significance of the current findings was underscored by our sensitivity analysis examining clinically elevated depressive symptoms. In these analyses, youth experiencing high levels of racial discrimination showed pronounced effects of enhanced protective parenting on their probability of exceeding 16 on the CES-D. Specifically, at low levels of change in PPB, youth experiencing elevated discrimination had a 56.1% chance of exceeding the depression cut-off, while those who experienced high levels of improvement in PPB in the context of elevated discrimination had only a 17.6% chance of having clinically elevated depressive symptoms. All effects controlled for baseline CES-D. These findings underscore that youth experiencing elevated levels of discrimination relative to their peers are especially likely to benefit from greater attention to protective parenting.

At the same time that these patterns support increased attention to promoting familybased resilience to racial discrimination’s pernicious effects on Black youth, and highlight youth at greatest risk, it should be noted that the underlying problem is discrimination itself. Racial discrimination occurs in multilevel structural contexts, ranging from face-to-face interactions to community and broader contexts. Reducing discrimination will therefore require systemic efforts aimed at multiple levels. Residing in socioeconomically disadvantaged or highly segregated communities has biological as well as psychological consequences (Lei, Beach, & Simons, 2018), and new policy initiatives to decrease community segregation are needed. Likewise, because structural racism may be viewed as a root cause of racialized inequalities (Phelan & Link, 2015), neighborhood or school intervention programs designed to enhance social connections and social integration provide alternative approaches to reduce perceived racial discrimination and protect vulnerable youth. Finally, broad societal efforts to combat discrimination should reduce risk among youth, relieving some of the pressure on Black families.

The current results can be seen as an important step forward by suggesting that the pernicious effects of elevated experiences of discrimination may be blocked in many cases by building and strengthening family practices that are community friendly and affirming and that many African American parents find appealing. Generalization to other groups at elevated risk for experiencing bias, negative messages, and internalized negative affect remains to be examined. However, the current results suggest the potential to refine other family-focused interventions and tailor them to the needs of a range of groups at risk for adverse impact of discriminatory treatment during childhood and adolescence.

Its strengths notwithstanding, the current study also has several limitations that should be noted. First, our sample was limited to Black youth and their families and so conclusions may not generalize to other groups experiencing discrimination-related difficulties. Nonetheless, a focus on Black youth may be particularly instructive because the level of overt and covert discrimination experienced by Black youth are thought to be especially high, with the historical context of discrimination for Black families being particularly prolonged and pronounced (Sears & Savalei, 2006). In addition, a focus on a single ethnic group may be useful when the set of behaviors that are most protective potentially varies across ethnic groups. Therefore, testing the potentially protective role of PPB using an ethnically homogeneous group may avoid potential confounding issues and potential measurement problems that can arise in multi-ethnic samples, thereby providing a more stringent test of theory. Nonetheless, it will be important to replicate observed buffering effects of PPB for other groups of youth who experience discrimination due to race and ethnicity, or other sources of negative stereotyping (e.g., sexual orientation, ability).

Second, all variables were assessed through self-reports, which may have resulted in some inflation of associations due to shared response biases. Future studies using direct observational measurements of change in PPB may help to further stringently test the proposed model while minimizing self-report artifacts. Finally, it should be noted that the current study does not rule out possible additional influences on the development of depressive symptoms among youth or additional pathways to the development of depressive symptoms. Many factors may contribute to youth depressive symptoms and so there may be multiple other sources of resilience that may be relevant to examine and develop in future investigations. Likewise, there may be additional sources of family resilience in the face of racial discrimination beyond protective parenting that could be further developed.

In conclusion, the current results extend prior observations that the erosive effects of discrimination on Black youths’ depressive symptoms is reduced by increased levels of protective parenting behavior. To complement prior non-experimental research, we used a randomized experimental design to construct a more stringent test of causal, buffering hypotheses. Our results replicated prior work on the erosive effects of discrimination on Black youth’s depressive symptoms and showed that change in PPB produced by ProSAAF participation exerted a protective, buffering effect. These findings highlight the potential of family-based interventions to promote constructed resilience resources that can in turn protect marginalized youth in the face of discrimination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Award Number R01 HD069439 and R01 AG059260 awarded to Steven R. H. Beach and Award Number P50 DA051361 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to Gene H. Brody. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Individuals not included in this study due to missing data at follow-up did not differ significantly from those who participated with regard to baseline study variables (see Supplemental Table S1).

Prior analyses: The ProSAAF intervention has been shown to enhance couple functioning and coparenting (Barton et al., 2017; Barton et al. 2018; Lavner, Barton, & Beach, 2019) and also has been shown to have indirect beneficial effects on child outcomes (Lavner, Barton, & Beach, 2020; Lei & Beach, 2020).

Contributor Information

Man-Kit Lei, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia..

Justin A. Lavner, Department of Psychology, University of Georgia.

Sierra E. Carter, Department of Psychology, Georgia State University.

Ariel R. Hart, Department of Psychology, University of Georgia.

Steven R. H. Beach, Department of Psychology and Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

References

- Anderson AT, Jackson A, Jones L, Kennedy DP, Wells K, & Chung PJ (2015). Minority parents’ perspectives on racial socialization and school readiness in the early childhood period. Academic Pediatrics, 15, 405–411. 10.1016/j.acap.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AW, Beach SR, Lavner JA, Bryant CM, Kogan SM, & Brody GH (2017). Is communication a mechanism of relationship education effects among rural African Americans? Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 1450–1461. 10.1111/jomf.12416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AW, Beach SRH, Wells AC, Ingels JB, Corso PS, Sperr MC, … Brody GH (2018). The Protecting Strong African American Families program: A randomized controlled trial with rural African American couples. Prevention Science, 19, 904–913. 10.1007/s11121-018-0895-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Wang Y, Shen Y, Boyle AE, Polk R, & Cheng YP (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist, 73, 855–883. 10.1037/amp0000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, … Cutrona CE (2006). Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77, 1170–1189. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Lei M, Chae DH, Yu T, Kogan SM, Beach SRH (2014). Perceived discrimination among African American adolescents and allostatic load: A longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Development, 85, 989–1002. 10.1111/cdev.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, ... & Chen YF (2004). The Strong African American families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development, 75, 900–917. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl Vinson Institute of Government. (2003). Dismantling persistent poverty in Georgia. Athens, GA: University of Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Carter SE, Ong ML, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Lei MK, & Beach SR (2019). The effect of early discrimination on accelerated aging among African Americans. Health Psychology, 38, 1010–1013. 10.1037/hea0000788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Elder GH Jr. (1994). Families in troubled times: The Iowa young and family project. In Conger RD & Elder GH (Eds.), Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America (pp. 3–19). Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Clavél FD, & Johnson MA (2016). African American couples in rural contexts. In Crockett LJ & Carlo G (Eds.), Rural ethnic minority youth and families in the United States: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 127–142). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-20976-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- David EJR, Schroeder TM, & Fernandez J (2019). Internalized racism: A systematic review of the psychological literature on racism’s most insidious consequence. Journal of Social Issues, 75, 1057–1086. 10.1111/josi.12350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Lambert SF, & Ialongo NS (2014). Longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1190–1196. 10.1037/a0034703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Lambert SF, Tynes BM, Bowleg L, Zea MC, & Howard LC (2020). Daily multidimensional racial discrimination among Black U.S. American adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 66, 101068. 10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, & Vega WA (2000). Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 295–313. 10.2307/2676322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, & Cunningham JA (2009). The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 532–543. 10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, & Bound J (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 826–833. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2004.060749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Kiviniemi M, & O’Hara RE (2010). Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 785–801. 10.1037/a0019880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, Maupin AN, Reyes CR, Accavitti M, & Shic F (2016). Do early educators’ implicit biases regarding sex and race relate to behavior expectations and recommendations of preschool expulsions and suspensions? Yale University Child Study Center. Retrieved from http://ziglercenter.yale.edu/publications/PreschoolImplicitBiasPolicyBrief_final_9_26_276766_5379_v1.pdf

- Goosby BJ, Cheadle JE, & Mitchell C (2018). Stress-related biosocial mechanisms of discrimination and African American health inequities. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 319–340. 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, & Pahl K (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42, 218–236. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP (2007). The Racism and Life Experiences Scales. In Bond M (Ed.), Compendium of diversity measures for organizations. Washington, DC: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakody R, & Kalil A (2002). Social fathering in low income, African American families with preschool children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 504–516. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00504.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Molgaard V, & Spoth R (1996). The Strengthening Families Program for the prevention of delinquency and drug use. In Peters RD & McMahon RJ (Eds.), Banff international behavioral science series, Vol. 3. Preventing childhood disorders, substance abuse, and delinquency (p. 241–267). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Barton AW, & Beach SR (2019). Improving couples’ relationship functioning Leads to improved coparenting: A randomized controlled trial with rural African American couples. Behavior Therapy, 50, 1016–1029. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Barton AW, & Beach SRH (2020). Direct and indirect effects of a couple focused preventive intervention on children’s outcomes: A randomized controlled trial with African American families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88, 696–707. 10.1037/ccp0000589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, & Ahn S (2013). The relation of racial identity, ethnic identity, and racial socialization to discrimination–distress: A meta-analysis of Black Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 1–14. 10.1037/a0031275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei MK, & Beach SR (2020). Can we uncouple neighborhood disadvantage and delinquent behaviors? An experimental test of family resilience guided by the social disorganization theory of delinquent behaviors. Family Process. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1111/famp.12527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei MK, Beach SR, & Simons RL (2018). Biological embedding of neighborhood disadvantage and collective efficacy: influences on chronic illness via accelerated cardiometabolic age. Development and Psychopathology, 30 (5), 1797–1815. 10.1017/S0954579418000937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In Cicchetti D D, Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2nd. (pp. 739–795). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM (2019). Healthy African American families in the 21st century: Navigating opportunities and transcending adversities. Family Relations, 68, 342–357. 10.1111/fare.12363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Butler-Barnes ST, Mayo-Gamble TL, & Inniss-Thompson M (2018). Excavating new constructs for family stress theories in the context of everyday life experience of Black AmericanFamilies. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10, 384–405. 10.1111/jftr.12256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, & Link BG (2015). Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Slopen N, Woolford S, Philip JT, Singer D, Kauffman AD, … Williams D (2018). Stereotyping across intersections of race and age: Racial stereotyping among White adults working with children. Plos One, 13, e0201696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst JC, Samuels ME, Jespersen KP, Willert K, Swann RS, & McDuffie JA (2002). Minorities in Rural America: An overview of population characteristics. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, Norman J. Arnold School of Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, & Garcia A (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 921–948. 10.1037/a0035754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears DO, & Savalei V (2006). The political color line in America: Many “peoples of color” or black exceptionalism? Political Psychology, 27(6), 895–924. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00542.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, & Jackson JS (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1288–1297. 10.1037/a0012747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, & Lewis RL (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 187–216. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semega JL, Fontenot KR, & Kollar MA (2017). Income and poverty in the United States: 2016: Current population report. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, P60–259, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin KH, Cutrona C, & Conger RD (2002). Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 371–393. 10.1017/S0954579402002109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Blumberg S, & Markman HJ (1999). Helping couples fight for their marriages: The PREP approach. In Berger R & Hannah M (Eds.), Handbook of preventive approaches in couple therapy (pp. 279–303). Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Tickamyer AR, & Duncan CM (1990). Poverty and opportunity structure in rural America. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 200–208. 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Fisher S, Hsu WW, & Barnes J (2016). What can parents do? Examining the role of parental support on the negative relationship among racial discrimination, depression, and drug use among African American youth. Clinical Psychological Science, 4, 718–731. 10.1177/2167702616646371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.