Abstract

Background:

Depressive symptoms and pain are prevalent during pregnancy. Untreated pain and depressive symptoms occurring together may have a negative effect on maternal and newborn outcomes, yet little is known about women’s experiences with pain and depressive symptoms during pregnancy. The purpose of this study is to describe the lived experience of depressive symptoms and pain occurring in women during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Methods:

A descriptive phenomenological study was conducted. Women during postpartum were recruited from a previous cross-sectional study of women in their third trimester which evaluated the relationship between pain, depression, and quality of life. Twenty-four women entered their responses into an online secure research website. These data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s method of descriptive phenomenological analysis.

Results:

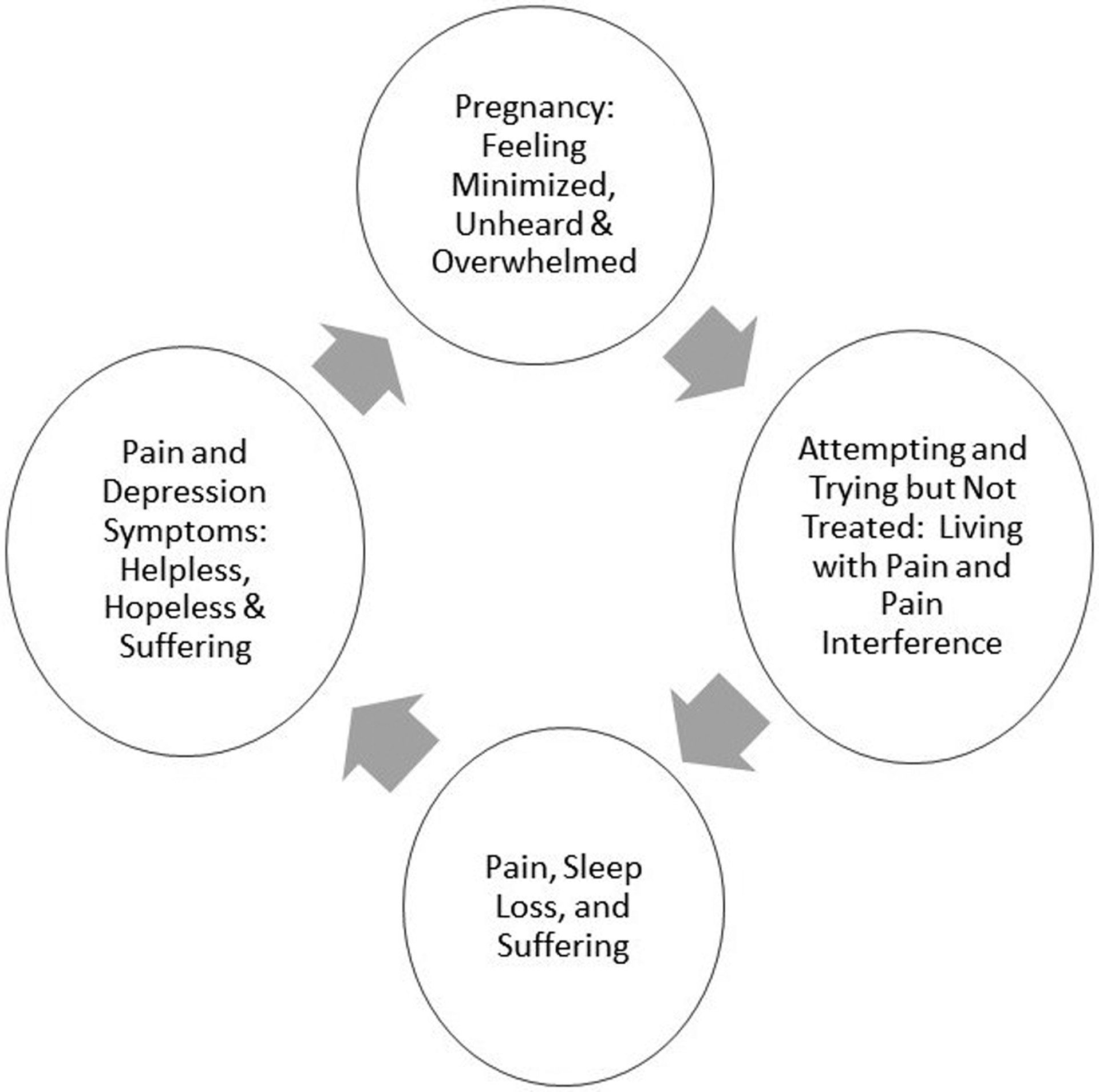

Four themes emerged that described the essence of women’s experiences with both pain and depressive symptoms Pregnancy: Feeling Minimized, Unheard and Overwhelmed; Attempting or Trying but not Treated: Living with Pain and Pain Interference; Pain, Sleep Loss, and Suffering; and Pain and Depressive Symptoms: Helpless, Hopeless, and Suffering.

Clinical Implications:

If a woman presents with pain, additional nursing assessments of her sleep and emotional state may be needed. Likewise, a positive depression symptom screening suggests the need for a more in-depth exploration of pain, pain interference, poor sleep, and mental health symptoms. As these women perceive their pregnancy as minimized, nurses may need to assist the women in setting realistic expectations and encouraging social support. Most of all, nurses listening to women describing these conditions may be essential in promoting the women’s wellbeing

Keywords: pain, depression, pregnancy, qualitative research

Introduction

Prevalence of antenatal depression or some depression symptoms ranges from 15% to 65% worldwide and is linked with low birth weight infants and preterm birth (Dadi et al., 2020). During pregnancy, both depressive symptoms and back or pelvic pain (55% to 78%) are prevalent (Dadi et al., 2020; Liddle & Pennick, 2015). Approximately 44.2% of women with severe pain report moderate to severe depressive symptoms during the third trimester of pregnancy (Vignato et al., 2020). Despite the frequency of their co-occurrence in pregnant women, little is known about women’s lived experience of both pain and depressive symptoms, which may hinder appropriate medical care.

Antenatal Depressive Symptoms

Antenatal depressive symptoms are self-reported symptoms found in Major Depressive Disorder to include: guilt, fatigue, hopelessness, diminished ability to concentrate, insomnia, irritability, and suicidal ideation (American Psychiatric Association [APA]), 2013; Pinheiro et. al, 2015).

Antenatal Pain

Pregnancy pain, e.g., back or pelvic pain, is common and contributes to sick leave (Liddle & Pennick, 2015). The increasing uterine weight and hormonally induced loosening of pelvic joints contributes to back and pelvic pain with pain increasing in the third trimester (Liddle & Pennick, 2015). Untreated pregnancy pain may prevent activities of daily living and disturb sleep (Liddle & Pennick, 2015). Chronic pregnancy-related pain increases risk of postpartum depression (Gaudet et al., 2013), however, the relationship of depression and its symptoms with pain is unclear (Pinheiro et al., 2015).

Identification and Treatment

Identification of pain and depressive symptoms occurring together during pregnancy may assist in better treatments (Virgara et al., 2018). Currently, treatment is complex as medications may pose a risk to the fetus (Berard et al., 2017). There is low to moderate evidence on effectiveness of recommended nonpharmacologic pain treatments (Liddle & Pennick, 2015; World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). Women sharing their lived experience with pregnancy pain and depressive symptoms would be one key source of information on these commonly comorbid conditions. Most quantitative studies that find a relationship with pain and depressive symptoms do not describe the relationship (Virgara et al., 2018). Qualitative studies have focused on the experience and management of depression or different types of pain during pregnancy (Beck, 2002; Close et al., 2016). One study of 14 women from the United Kingdom described a physical and emotional impact of pain disturbing sleep (Close et al., 2016). Qualitative data on effects of pain with depressive symptoms among pregnant women are needed. The research question for this study is what is the lived experience of women undergoing both pain and depressive symptoms during the third trimester of pregnancy?

Methods

Research Design

This descriptive phenomenological study describes women’s lived experience with pain and depressive symptoms during the third trimester of pregnancy as retrospectively reported within one year of birth. Descriptive phenomenology is the thorough account of everyday life experiences through conscious awareness. Husserl’s phenomenology provides the philosophical underpinnings for this study to include the “lived experience” (Husserl, 1970). The “lived experience” is explored through three phenomenological concepts: intentionality (being aware), essences (description of the relationships), and phenomenological reduction (suspending assumptions) (Husserl, 1962). Colaizzi’s phenomenological research method, which builds upon Husserl’s concepts, is used for this data analysis (Colaizzi, 1978). Colaizzi believed that researchers’ assumptions should not be completely bracketed or disregarded, but should instead guide questioning (Colaizzi, 1978). Assumptions about ineffective pain treatments for some women guided this study’s questions.

Procedure

After Institutional Review Board approval, emails were sent to women from a previous quantitative study on pain and depressive symptoms who agreed to be contacted for future research (Vignato et al., 2020). Women interested in participating were given a secure REDCap (2017) website link in which to consent and respond to the following questions: (1) Please describe your experiences of both pain and depressive symptoms during the last three months of pregnancy. (2) Please describe a day during the third trimester of pregnancy when you experienced both pain and depressive symptoms from the time you woke up until the time you went to bed. (3) Is there anything in particular that you did when you began to experience both pain and depressive symptoms? After the experience? (4) Is there anything you wish to share with us about pain and depressive symptoms during the last three months of pregnancy that has not been asked?

Our Previous Study

In our quantitative study, 70 participants who screened positive for depressive symptoms using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and for pain according to the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) agreed to be contacted again for future research. The EPDS Cronbach’s alpha was .89, and for the BPI, 0.89 for the pain intensity and 0.94 for the pain interference subscales. Inclusion criteria were: 18 years or older, English speaking, and in their third trimester of pregnancy as previously described (Vignato et. al., 2020).

Sample

A convenience sample of 24 women from the previous study was recruited through email. Those eligible for inclusion had screened positive for depressive symptoms and pain in our previous study (Vignato, 2020). All had scored their pain greater than 4 out of 10 on the BPI. Five also had moderate to severe depressive symptoms and the remaining 19 experienced mild depressive symptoms. All were living in the United States and within one year of their birth. Mean age was 30 years (range 24 to 39), and most had a partner (95%) except for one who was divorced. Most were Caucasian (90%) with one woman being Asian and one Latina. They were generally well educated: 23 answered the education question (high school diploma, 1; some college, 11; associate’s degree, 1; and bachelor’s degrees or higher, 10).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi’s (1978) eight methodological steps to evaluate the women’s descriptions of pain and depressive symptoms. This method encourages flexibility between stages to clarify new understandings of meanings (Colaizzi, 1978). Components of methodological congruence, including rigor in documentation, procedural rigor, and auditability, were addressed. Rigor in documentation was attained for the questions that were asked through detailed discussions with research team members based upon extant literature and results of our previous quantitative study. Procedural rigor included emailing women with both severe and mild depressive symptoms to obtain a diverse sample and prevent “elite bias.” Journals of the researchers’ thoughts and feelings were kept to assist in bracketing and theme development. Three independent researchers verified an audit trail describing how themes were uncovered and confirmed until data saturation was achieved (Table 1). During the process, NVivo (2020) was used to explore findings for data triangulation. All women had their initial responses clarified once and then were contacted for the final summation through a new REDCap link. All women agreed with the final summation.

Table 1.

Significant Statements and Formulated Meanings for the Themes

| Theme | Significant Statements | Formulated Meanings |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy: Feeling Minimized, Unheard, and Overwhelmed | I remember trying to describe how bad I was feeling to my doctor and him essentially brushing it off. That was hard. | The woman tried to describe how bad she was feeling but her doctor essentially brushed it off. |

| Attempting and Trying but Not Treated: Living with Pain and Pain Interference | However, once I began feeling better, they…decided I no longer needed to be seen. I continued to walk about a mile a day so that I would stay active but the pain in my pubic symphysis eventually came back. I felt I was right back where I started and that nothing would ever make this pain go away. | The woman was receiving treatments for her pain but once she was feeling better the providers decided to stop the treatments. The woman tried to stay active but the pain came back. The woman felt like she was back where she started and nothing would make the pain go away. |

| Pain, Sleep Loss, and Suffering | “The pain was in my sciatic nerve which progressed each day to where I could hardly walk…It interrupted by sleep, prevented me from being able to carry my toddler… | The woman had sciatic nerve pain that progressed to the point where she could hardly walk. The pain interrupted her sleep and prevented her from carrying her toddler. |

| Pain and Depressive Symptoms: Helpless, Hopeless & Suffering | I would lay down to get some sleep, and it [pain] would be excruciating, I would opt to sit up and it would be even worse. It was a back and forth battle all the time, which eventually lead to depression and sadness… | The woman would lay down to sleep, but the pain was excruciating so she opted to sit up and it became worse. It was a back and forth battle all the time and eventually led to depression and sadness. |

Results

Participants described similar experiences, whether their depressive symptoms were mild, moderate, or severe. Our results revealed that pain does influence depressive symptoms. Pain, pain interference, and the lack of effective pain treatments interfered with sleep, social support, and others’ understanding which contributed to a cycle of pain and depressive symptoms. Four distinct but connected themes were identified on the women’s lived experience of pain and depressive symptoms during pregnancy.

Pregnancy: Feeling Minimized, Unheard & Overwhelmed

Women felt that a significant number of medical providers and other trusted men and women in their lives dismissed them when they discussed their pain. For example, one woman wrote, I’d told my OB about the pain at each appointment, but he always said it was “normal. Another woman felt belittled by her mother-in-law. She shared, I remember thinking that it’s sad that I am depressed over here and instead of supporting me as a women and mother she [Mother-in-Law] instead insulted me and belittled me and my feelings…I remember sitting on the bathroom floor and cried [sic].

Women would minimize their situation and abilities because they felt they should be able to meet all of their obligations. They felt guilty about their inability to properly mother or meet work expectations. As two women described, this affected their ability to care for their children. One wrote, Emotionally, I felt incredibly disappointed in myself for being less mobile and felt very guilty about my toddler needing & wanting affection that I couldn’t comfortably provide. Another stated, Although I did not have extreme pain during my last 3 months of pregnancy, what I remember more so is just being constantly uncomfortable. Because of that, both my job as a teacher and also caring for my other children felt overwhelming. I felt like I was failing…I felt very frustrated…I could not meet expectations for myself.

Women also felt minimized by society and had concerns about the societal pressures of needing to work and stigma related to pregnancy pain. As two women described, I felt crazy, like everyone thought I was exaggerating how intense the pain was. and There are not very many resources for pregnant females. I found my hospital work environment not to be welcoming or accommodating. I worked through any pain I had because I did not want to jeopardize my maternity leave.

Attempting and Trying but Not Treated: Living with Pain and Pain Interference

Women described the ways in which the inability to treat pain led to pain interference. For example, this woman was unable to find pain relief:

I had terrible pain in my hips, knees, and lower back…I am on my feet throughout the day…the impact on my knees and back was brutal…there was no time or day when I felt good, and nothing that really helped. Another woman described the pain, not as extreme, but constant. She stated, I think they called it “round ligament” pain that I experienced a lot during my third trimester. It wasn’t that the pain was too extreme but just the constantness of it that exhausted me. The feeling of not being able to get away from it. I think that tended to make me feel overwhelmed…

Women also describe the pain as excruciating as written, Walking was difficult at times because it feel [sic] like my body is being ripped apart… and With all the pain, sometimes excruciating, and the inability to walk, sleep, put on clothes, play with my 5-year-old son that I would like it really took a toll. If relief was obtained, it did not last long as stated, “…things like a supportive spouse or pet helped, even for a few fleeting moments. When providers listened, some relief was obtained as stated, …the PT decided to forgo rigorous therapy and instead applied warm heat to my back and massaged my muscles. This helped significantly.

Pain, Sleep Loss, and Suffering.

Women described how untreated pain and pain interference prevented sleep. One woman described her sleep experience in the third trimester in relation to what it is normally. [The sciatica] also made sleeping a nightmare (more so than third trimester pregnancy sleep already is). Another woman described how she could not function during the day as stated, The inability to sleep caused me to be exhausted during the day and when I couldn’t focus I would really get down on myself leading to some issues with self-loathing…I have previously had depression and could see the symptoms coming back…

Pain and Depressive Symptoms: Helpless, Hopeless & Suffering.

When women could not get pain relief, perform their normal daily activities, or sleep, they described symptoms of depression such as helplessness and hopelessness. One woman shared how these symptoms felt in relation to her prior depression. She wrote, I felt like my already unstable mental health got worse the worse my pain would get…I have battled depression for over 10 years; however, this pregnancy was a little different. I was mentally doing great, until my second and third trimester when I began hurting so badly. I felt like I was going to be pregnant forever…I never saw this pain ending for me.

Women felt they were experiencing pain and suffering from these depressive symptoms. As one woman shared, Depression is worse than physical pain. Other women described severe symptoms of depression and feelings of being alone as stated, I had talked to my OBGYN and she upped my dose of anxiety medicine…It did not work, I felt like my daughter wanted to kill me. I felt really alone, like no one cared or understood what I was feeling.

Women would also lie to others and minimize their own feelings as stated, I always lied and said I was fine because what mother wants to admit she’s drowning in her own mind during the happiest time ever…I just wanted to end it all. Illustrative of a continuous cycle, women described being minimized as well as reporting pain, pain interference, lack of sleep, and depressive symptoms as suffering (Figure 1). As stated, I had some pretty severe back pain due to the baby sitting on my sciatic nerve. It made it hard to sleep which resulted in a lack of energy throughout the day. I know that my moods swings and depression had to die [sic] with the lack of sleep and also the feeling of pressure to continue to work 12-hour days…I remember feeling overwhelmed with pain and loneliness…I remember trying to describe how bad I was feeling to my doctor and him essentially brushing it off. That was hard.

Figure 1.

Cycle of Pain and Depression Symptom Themes

Participants’ Response to Final Summation of Results

For Colaizzi’s Steps six and seven in which respondents review the final summation of the researchers’ results, all women agreed with the results as stated, Yes, definitely. Even reading this summation brought me to tears. Another added: …the pain women experience because they do keep up with the daily tasks…no matter how much pain I had or how exhausted I was. What was almost more painful though was that my husband/family just EXPECTED that I SHOULD be able to continue to do everything as before…Their lack of understanding led to much of my loneliness and depression…

Discussion

Our results offer new information on pain and depression as comorbidities during pregnancy. Since pregnancies are expected to be uncomfortable, women may suffer in silence and become depressed. Our findings uncover a continuous cycle of women experiencing suffering related to untreated pain, pain interference, lack of sleep, and depressive symptoms. Women felt unheard and minimized, and in response they minimized their own symptoms. The synergy of pain, lack of sleep, and perceived lack of understanding or support has a negative impact on the mental state of women as they approach birth and bonding with their newborn. More research is needed to explore these complexities and their impact on the perinatal experience.

Our results are consistent with findings of earlier studies. Pain leads to insomnia which is then linked with antenatal depression (Beebe et al.,2017). Current treatments for pain relief during pregnancy are often ineffective (Close et. al., 2016). For example, current medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, that treat both depression and some types of pain, are promising pharmacologic treatments but may not treat back pain (Berard et al., 2017). Non-pharmacologic treatment provides temporary pain relief but does not improve pain interference (Liddle & Pennick, 2015).

Our findings from this relatively homogenous sample suggest higher education does not exempt women from experiencing physical pain or the psychological pain of feeling unheard, minimized, or dismissed when their pain is not validated. Women experiencing pain during pregnancy may be likely to minimize the rated intensity of their pain and related symptoms. Women in the previous quantitative study identified by the EPDS as having mild depression described severe symptoms in this study such as wanting to end their life. As noted by women in the general population, these findings suggest women may not reveal depressive symptoms due to being minimized by health care providers or others that support them, stigma, culture, or confusion replying to a questionnaire (FitzGerald & Hurst, 2017; Recto & Champion, 2018).

Limitations and Strengths

Limitations were reduced by strictly adhering to Colaizzi’s method of analysis and using data triangulation, or multiple methods to confirm themes and obtain data saturation. Besides journaling and researcher discussions, word clouds run by NVivo (2020) assisted in uncovering both themes and the related cycle of themes. The delay between the third trimester screen and the one year after birth for this study requires confirmation of our results. Composition of the sample is lacking in diversity based on race, ethnicity, education, and partner status, which may reduce applicability of findings.

Clinical Implications.

Specific findings, themes, and cycle of pain and depression from this study have several clinical implications. Discrepancies between respondents’ earlier quantified EPDS scores and descriptions of their actual depressive symptoms suggest women may benefit from routine depression screening during each trimester of pregnancy. A positive depression screening would alert clinicians to perform an in-depth exploration of physical symptoms such as pain, pain interference and poor sleep as well as previously described behavioral health symptoms.

Our findings emphasize the critical role nurses, certified nurse midwives, nurse practitioners, and clinical nurse specialists fulfill in maternal child nursing and all of health care. Women’s descriptions of their experiences of being minimized remind us of the importance of hearing patients rather than merely listening to them or dismissing their complaints, and of understanding our own biases that may interfere with providing empathetic care. Nurses are patient advocates. As nurses approach birth and maternal-newborn bonding, a better understanding of how the synergy of pain, sleep loss, and perceived lack of support can have a negative impact on women can empower nurses to advocate for women and for supportive pregnancy workforce policies. As women progress through pregnancy, they and their families may need help reframing earlier expectations. Exploring and validating findings from this study will add to nursing knowledge aimed at promoting pregnancy experiences that reduce negative sequalae in women and their families after birth.

Clinical Implications.

A positive depression symptom screening suggests the need for a more in-depth exploration of pain, pain interference and poor sleep, and further mental health symptoms.

Women found to have mild depressive symptoms may need an additional routine assessment for moderate to severe depressive symptoms every trimester and immediately postpartum.

After establishing rapport, nurses may need to help women and their families reframe pregnancy expectations in order to promote the women’s physical and mental health.

Nurses can educate women about the most effective ways to use nonpharmacologic pain management techniques (i.e. schedule), obtain appropriate social support, and other community resources as needed.

Nurses can continue to advocate for maternity friendly workplace policies to reduce stress, fatigue, and pain to promote maternal health.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the NIH funded T32 (NR11147) Pain and Associated Symptoms Grant (McCarthy and Herr), the University of Iowa College of Nursing Class of 1969 Scholarship, and National Association for Neonatal Nurses Research Grant (Vignato). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54TR001356 (University of Iowa).

Contributor Information

Julie Vignato, College of Nursing, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa.

Cheryl Beck, College of Nursing, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut.

Virginia Conley, College of Nursing, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa.

Michaela Inman, College of Nursing, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa.

Micayla Patsais, College of Nursing, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa.

Lisa S. Segre, College of Nursing, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-V, 5th ed. APA, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Beebe KR, Gay CL, Richoux SE, & Richoux KAL (2017). Symptom experience in late pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing, 46(4), 508–520. 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT (2002). Postpartum depression: A metasynthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 12(4), 452–72. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F104973202129120016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bérard A, Zhao JP, & Sheehy O (2017). Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of major congenital malformations in a cohort of depressed pregnant women: an updated analysis of the Quebec Pregnancy Cohort. BMJ open, 7(1), e013372. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close C, Sinclair M, Liddle D, Cullough JM, & Hughes C (2016). Women’s experience of low back and/or pelvic pain (LBPP) during pregnancy. Midwifery, 37, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaizzi PF (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In Valle R & King M (Eds.), Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology (pp.48–71), New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dadi AF, Miller ER, Bisetegn TA, & Mwanri L (2020). Global burden of antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health, 20, 173. 10.1186/s12889-020-8293-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald C, & Hurst S (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18(1), 19. 10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet C, Wen SW, & Walker MC (2013). Chronic perinatal pain as a risk factor for postpartum depressive symptoms in Canadian women. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue canadienne de sante publique, 104(5), e375–e387. 10.17269/cjph.104.4029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husserl E The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology (Trans. D. Carr). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press;1970. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl E Ideas: General introduction to pure phenomenology. New York: MacMillan; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle SD, & Pennick V (2015). Interventions for preventing and treating low-back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9:CD001139., 1465–1858. 10.1002/14651858.CD001139.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NVivo. (2020). Qualitative data analysis. https://www.qsrinternational.com/

- Pinheiro M,B, Ferrieira ML, Refshauge K, Ordonana JR, Machado GC, Prado LR, Maher CG, & Ferrieira PH (2015). Symptoms of depression and risk of new episodes of low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care & Research, 67(11), 1591–1603. 10.1002/acr.22619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recto P & Champion JD (2018). Mexican-American adolescents’ perceptions about causes of perinatal depression, self-help strategies, and how to obtain mental health information. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 31(2–3), 61–69. 10.1111/jcap.12210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REDCap. (2017). REDCap features. https://its.uiowa.edu/redcap

- World Health Organization Reproductive Health Library. (2016). WHO recommendation on interventions for the relief of low back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Reproductive Health Library. [Google Scholar]

- Vignato J, Perkhounkova Y, McCarthy AM, & Segre LS (2020). Pain and Depression Symptoms During the Third Trimester of Pregnancy. MCN. The American journal of maternal child nursing, 45(6), 351–356. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgara R, Maher C, & Van Kessel G (2018). The comorbidity of low back pelvic pain and risk of depression and anxiety in pregnancy in primiparous women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18, 288. 10.1186/s12884-018-1929-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]