Abstract

Sarcopenia, or age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is an important contributor to loss of physical function in older adults. The pathogenesis of sarcopenia is likely multifactorial, but recently the role of neurological degeneration, such as motor unit loss, has received increased attention. Here, we investigated the longitudinal effects of muscle hypertrophy (via overexpression of human follistatin, a myostatin antagonist) on neuromuscular integrity in C57BL/6J mice between the ages of 24 and 27 months. Following follistatin overexpression (delivered via self-complementary adeno-associated virus subtype 9 injection), muscle weight and torque production were significantly improved. Follistatin treatment resulted in improvements of neuromuscular junction innervation and transmission but had no impact on age-related losses of motor units. These studies demonstrate that follistatin overexpression-induced muscle hypertrophy not only increased muscle weight and torque production but also countered age-related degeneration at the neuromuscular junction in mice.

Keywords: Follistatin, myostatin, sarcopenia, neuromuscular junction, motor unit number estimate, single fiber electromyography, contractility, twitch, tetanic, Adeno-associated

1. INTRODUCTION

Physical functional capacity is an important determinant of quality of life in older adults (Fusco et al., 2012; McPhail et al., 2010). Sarcopenia, or pathological age-related decline in muscle mass and strength, is a major contributor to the loss of physical function in older adults (Clark and Manini, 2010; Rosenberg, 1989, 2011; Sayer et al., 2013). Sarcopenia is also independently associated with increased risk for disability, frailty, and mortality and has a significant economic impact on society (Goates et al., 2019; Sayer et al., 2013). In 2002, health care costs in the United States directly attributable to sarcopenia were estimated at $18.5 billion, and between the years 1999–2004, the costs of hospitalization due to sarcopenia were estimated to be $40.4 billion (Goates et al., 2019; Janssen et al., 2004). The pathogenesis of sarcopenia is only partly understood and is likely multifactorial (Sayer et al., 2013; Stangl et al., 2019). Management of sarcopenia is primarily focused on therapeutic exercise and nutritional interventions (Beaudart et al., 2016; Hardee and Lynch, 2019; Hunter et al., 2004; McPhee et al., 2016). In a parallel study, we examined the neurobiological effects of exercise in aged mice (Chugh et al., 2021). However, many older adults may be unable to exercise due to co-morbid conditions. Hence there is a need for improved understanding of the mechanisms that contribute to sarcopenia and development of additional treatment strategies.

In the current study, we investigated the effects of increasing muscle size [via follistatin (FST) overexpression] on neuromuscular function and integrity in aged mice. FST is a secreted glycoprotein that acts as a negative regulator of several members of the TGF-ß superfamily, one of which is myostatin (Rodino-Klapac et al., 2009). FST is expressed in the brain, liver, bone marrow, ovary and blood vessels and plays an important function in reproductive physiology (Rodino-Klapac et al., 2009). FST has two precursor forms, FS-344 and FS-317, which undergo peptide cleavage to produce the active FS-315 and FS-288 respectively (Haidet et al., 2008; Shimasaki et al., 1988). FS-317 lacks exon 6 that forms the carboxy-terminal of the protein and has a high affinity for binding to proteoglycans on the cell surface (Rodino-Klapac et al., 2009). Studies have shown that upon FST overexpression, via gene delivery or transgenic approaches in mice, muscle exhibits hypertrophy and improved muscle fiber regeneration and there is proliferation of satellite cells (Wagner 2005, Wagner 2002, Gilson 2009, Zhu et al 2011). Here we investigated the FS-344 isoform of FST due to its specificity for muscle effects and prior work showing muscle hypertrophy when overexpressed postnatally in mice and non-human primates (Haidet et al., 2008; Kota et al., 2009).

Signaling at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) from the motor neuron to the muscle as well as from the muscle to the presynaptic nerve terminal are important for development, repair and maintenance of neuromuscular integrity (Delbono, 2003; Messi and Delbono, 2003). We have previously shown that aging C57BL/6J mice demonstrate features of prominent motor unit loss at about 20 months and NMJ transmission failure occurring after 24 months of age (Chugh et al., 2020; Sheth et al., 2018). The current experiments were designed to test the neurobiological impact of muscle hypertrophy on motor unit losses and NMJ transmission instability and failure in aged C57BL/6J mice. We employed a longitudinal study design with delivery of FST via adeno-associated subtype 9 viral vector (AAV9) delivery at 24 months of age and tracking of outcomes until 27 months of age corresponding to roughly 80 and 90 human years, respectively (Dutta and Sengupta, 2016).

2. METHODS

2.1. Animal care

All procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Ohio State University, Columbus OH. A total of 57 C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the National Institute on Aging Mouse Colony and used in the current studies. In the longitudinal study, a total of 34 mice were used [vehicle: n=17 (11 males and 6 females) and FST: n=17 (11 males and 6 females)] in the FST group. For the investigation of endogenous myostatin and FST levels at different ages, a total of 23 untreated C57BL/6J mice were used [12 months: n=6 (3 males and 3 females), 24 months n=9 (5 males and 4 females), and 27 months n=8 (4 males and 4 females)].

2.2. Anesthesia and animal preparation

During in vivo electrophysiological and muscle contractility measurements, mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (3–5% for induction, and 1.5–2.5%) for maintenance using a digital inhaled anesthesia system (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT, USA). Animal temperature was maintained at 37 °C, with a warm water bath-heated stage (HTP-1500, Androit Medical System, Loudan, TN, USA) for muscle physiology tests and with a thermostatically controlled heating plate (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) for electrophysiology. The duration of experiments was kept under 20 minutes. During anesthesia, a petroleum-based eye ointment (Paralube Vet Ointment, Dechra Veterinary Products, UK) was applied to prevent corneal dryness. All procedures were performed on the right hind limb which was shaved using clippers (Remington VPG6530, Middleton, WI). Muscle physiology experiments were performed the day following the electrophysiology studies to minimize duration of anesthesia on a single day. At the final study time point, single fiber electromyography (SFEMG) was performed to assess NMJ transmission. Following SFEMG, mice were euthanized. The triceps brachii, gastrocnemius, and soleus muscles were collected and weighed.

2.3. Experimental timeline

The FS-344 variant of human FST, packaged in self-complementary AAV9 was injected in 24-month-old C57BL/6J mice (AAV9-FST) (Handy, 2009). A total viral dose of 1.13*1011 vg/mouse of AAV9-FS-344 in a final volume of 50 μl sterile saline was injected into four hind limb muscles namely the right and left gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior in equal amounts in 24-month-old C57Bl/6J mice (n=17, 11 males and 6 females). Control mice were injected similarly with the vehicle, sterile saline (n=17, 11 males and 6 females). Prior to injection, mice were assessed at baseline with electrophysiology and muscle contractility measurements and randomized to treatment to AAV9-FST or vehicle injections while stratifying by sex and ensuring balanced distribution based on baseline measures. Following injection, mice were reassessed with electrophysiology and muscle outcomes every 2 weeks for a total of 12 weeks. At endpoint, mice were 27 months of age. All in vivo and endpoint assessments were performed with blinding to treatment group. Figure 1 shows the study timeline.

Figure 1. Study Timeline.

AAV-FST344 was injected in the right and left gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior muscles in equal volumes to a total dosage of 1.13 × 1011 vg/mouse. Physiological measurements of motor unit and muscle function were done at baseline before injection and then every two weeks after the injection for 12 weeks. The mice were euthanized at 12 weeks post-injection at the age of 27 months for the measurement of wet muscle mass and morphological and biochemical analyses of muscle tissues.

2.4. In vivo muscle physiology

Muscle contractility was assessed as described previously (Sheth et al., 2018; Wier et al., 2019). Briefly, mice were positioned in the supine position on a heated stage. The right hindlimb paw was securely taped to a rotating foot plate, and the femoral condyles were clamped securely to ensure no movement during measurements. The stage position was adjusted to position the ankle at 90 degrees (foot and tibia positioned perpendicular to each other). Two monopolar needle electrodes (Natus Neurology Inc., Middleton, WI, USA) were inserted subcutaneously at the proximal, medial leg. The stimulus was adjusted to determine the maximal stimulus intensity, and ~120–150% of maximal stimulus was used for subsequent measurements. Peak twitch torque was measured following a single supramaximal stimulation of 0.2 ms square wave pulse, and tetanic torque was measured following a 500 ms train of 0.2 ms stimuli delivered at 125 Hz.

2.5. Electrophysiology

Compound motor action potential (CMAP) and single motor unit potential (SMUP) amplitudes were recorded from the right hind leg as previously described using a clinical electrodiagnostic system (Cadwell, Kennewick, WA, USA) (Arnold et al., 2015; Sheth et al., 2018). Two insulated 28-gauge monopolar needle electrodes (Teca, Oxford Instruments Medical, NY, USA) were inserted subcutaneously as the proximal hindlimb to stimulate the sciatic nerve. Two fine wire ring electrodes (Alpine Biomed, Skovlunde, Denmark) were used as recording electrodes and were placed distal to the knee over the bulk of the gastrocnemius muscle (active recording electrode) and over the metatarsal region of the foot (reference recording electrode). A disposable ground electrode (Carefusion, Middleton, WI, USA) was placed on the tail. To measure the CMAP, the right sciatic nerve was supramaximally stimulated (<10mA constant current intensity, 0.1 ms pulse duration, 20 mV sensitivity, 10 Hz – 10 KHz filter) and the baseline-to-peak and peak-to-peak amplitudes were recorded. Motor unit number estimate (MUNE) was determined using an incremental technique (Arnold et al., 2015; Sheth et al., 2018). A total of 10 incremental submaximal responses (50–500 μV sensitivity, 10 Hz – 10 KHz filter) were recorded and averaged to determine the single motor unit potential (SMUP) amplitude. MUNE was calculated as follows: MUNE = CMAP amplitude peak-to-peak/Average SMUP peak-to-peak.

2.6. Single Fiber Electromyography (SFEMG)

SFEMG was performed as described previously using clinical electrodiagnostic system (Natus Neurology Inc., WI, USA, Viking software) (Chugh et al., 2020). During SFEMG recordings, two 28-guage monopolar needle stimulating electrodes were inserted subcutaneously at the proximal hindlimb over the sciatic nerve (Natus Neurology Inc., Middleton, WI, USA). A ground electrode was placed on the left foot (Carefusion, Middleton, WI, USA). The recording SFEMG needle (Natus neurology Inc, WI, USA) was inserted into the right gastrocnemius muscle parallel to the length of the muscle fibers. The filter was set at 1 KHz – 10 KHz, and sampling rate was 50 kHz. Sweep speed was set to 500 μs. The sciatic nerve was stimulated at 10 Hz frequency with constant current intensities between 0.3–10 mA with 0.1 ms pulse duration to record single fiber action potentials. Criteria for acceptable single fiber action potentials (SFAP) included: (i) a stable all-or-none response with consistent morphology with no instability or fractionation, (ii) a minimum baseline-to-peak amplitude of 200 μV, and (iii) a baseline-to-negative peak rise time of <500 μs. NMJ jitter and blocking was assessed during sciatic nerve stimulation at 10 Hz frequency for 50–100 stimulations per synapse. Jitter is a function of time variability between consecutive SFAP responses. Jitter, quantified by mean consecutive delay (MCD), was calculated from the latencies of 50–100 consecutive discharges (n) using peak detection using the following equation:

NMJ blocking is defined as the failure of action potential generation following nerve stimulation indicative of loss of safety factor at the NMJ (Stalberg and Trontelj, 1997). Individual NMJ synapses/SFAPs were categorized as synapses with blocking or without blocking. On average, 10 unique synapses/SFAPs were obtained per animal for the calculation of jitter and assessing SFAP blocking.

2.7. Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISAs were performed on homogenized gastrocnemius muscle and expressed as per mg of total protein. About 50–70 mg of gastrocnemius muscle was homogenized using a motorized pestle in 300μl lysis buffer: 150mM NaCl, 50mM TrisHCl, 5mM CaCl2, 0.02% NaN3, 1% Triton-X, pH 7.6 (Chugh et al., 2013). Just before use, Roche EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (1 tablet/10 mL) was added to the lysis buffer (SigmaAldrich, Cat. No. 11836170001, MO, USA). This was followed by 5s of sonication after which 200μl more of lysis buffer was added and the samples were centrifuged at ~17,000g, 30min, 4°C. The supernatant was used for analyses of total protein concentration and ELISAs. To assess the total protein concentration, BCA assay was performed using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Cat. No. 23225, MA, USA) as per manufacturer’s instructions. 1:20 dilution of the muscle extract was used for BCA. Human follistatin levels were measured by Quantikine ELISA (RnD Systems, Cat. No. DFN00, MN, USA) as suggested in the instructions, at 1:2 dilution. Mouse follistatin was measured using sandwich ELISA according to the user manual (LSBio, Cat. No. LS-F22235, WA, USA). The dilution of muscle homogenates ranged from 1:50 for 12m and 24m old samples and 1:200 to 1:400 for the 27m old samples. Mouse myostatin levels were measured with a Quantikine ELISA kit (RnD Systems, Cat. No. DGDF80, MN, USA) at 1:10 dilution according to manufacturer instructions.

2.8. Immunohistochemistry

Gastrocnemius muscle samples were sectioned longitudinally on a cryostat at 30 μm thickness. The slides were blocked with 10% goat serum, 4% BSA, 3% TritonX-100 in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature in a humidified chamber. This was followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies: chicken polyclonal NF-200 (Ab72996, Abcam, 1:5000) and rabbit monoclonal anti-Synapsin-1 (5297, Cell Signaling, 1:200). After 3 washes of 10 min each in PBS, the slides were incubated in a dark humidified chamber at room temperature for 2 hours with the following secondary antibodies: Alexa-594 goat anti-chicken (A11042, Life Technologies, 1:1000), Alexa-546 goat anti-rabbit (A11010, Life Technologies, 1:1000) and a-bungarotoxin-488 (B13422, Life Technologies, 1:1000). After 3 washes in PBS for 10 min each, the slides were mounted with Fluoromount-G (0100–01, Southern Biotech) and dried overnight at room temperature. Confocal images were taken with Andor Revolution WD spinning disk confocal microscope. NMJ morphology was analyzed in 3 vehicle and 3 follistatin male mice with a sampling of approximately 70–100 junctions per animal.

Each NMJ was categorized as fully innervated or not-fully innervated (partial or denervated) and fragmented or non-fragmented. Using ImageJ, confocal z-stack projections were analyzed for the co-localization of NF-200 (labeling presynaptic nerve), synapsin (labeling presynaptic nerve terminal) and α-bungarotoxin (labeling post-synaptic AchR). Individual NMJ synapses were categorized as fully innervated if there was a complete colocalization between pre- and post-synaptic elements and as partially innervated if the colocalization was not complete and as denervated when there was no colocalization at all. NMJ fragmentation was qualitatively analyzed based on the morphology of the postsynaptic endplate labeled by α-bungarotoxin staining. A complete solid pretzel-like endplate was defined as a non-fragmented NMJ whereas some degree of fragmentation in the endplate was considered as a fragmented NMJ.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v8.4.2, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess data for parametric or non-parametric distribution. Due to non-normal distribution, Kruskal Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to analyze mouse FST expression levels in gastrocnemius muscle from untreated mice at 12, 24, and 27 months of age, and Mann-Whitney test was used to compard mouse FST expression levels in gastrocnemius between AAV9-FST and vehicle injected mice. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to analyze mouse myostatin expression levels in gastrocnemius muscles from groups of uninjected mice at 12 months, 24 months, and 27 months of age, and unpaired t-test was used to compare mouse myostatin expression levels in gastrocnemius muscle from AAV9-FST and vehicle injected mice at endpoint.

Mixed effects model using Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used to analyze longitudinal muscle contractility, CMAP, SMUP and MUNE data over time. At endpoint, gastrocnemius and triceps brachii muscle weights, twitch torque normalized to muscle weight, and tetanic torque normalized to muscle weight were compared between groups with unpaired t-tests. Due to non-parametric distributions, Mann-Whitney test was used to compare SFEMG jitter. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze SFEMG blocking frequency. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to investigate the relationship between human FST expression and gastrocnemius muscle weight. For all tests, p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Confirmation of Human FST Overexpression, Endogenous FST and Myostatin Expression During Aging, and Increased Muscle Mass following human FST Overexpression

Overexpression of human FST was confirmed in gastrocnemius muscle from AAV9-FST injected mice (~450% of the vehicle injected group) (Figure 2A). We examined endogenous expression of mouse FST at 12, 24 and 27 months of age in untreated mice and in mice following injection of AAV9-FST (Figure 2B). Endogenous FST levels in gastrocnemius muscles were similar between the ages of 12 months and 24 months but were significantly increased at 27 months of age (Figure 2B, Left). There was no significant change in endogenous mouse FST expression following AAV9-FST injection (Figure 2B, Right). We similarly investigated myostatin at 12, 24 and 27 months of age in untreated mice and in treated mice following injection of AAV9-FST (Figure 2C). There was no significant change in the expression of endogenous myostatin between the ages of 12 to 27 months in untreated mice (Figure 2C, Left). Endogenous myostatin expression levels were unchanged following AAV9-FST injection (Figure 2C, Right).

Figure 2. Human FST overexpression following AAV-9 and expression of endogenous FST and myostatin with age and following AAV9-FST injection.

(A) Overexpression of human FST following AAV9-FST. Human FST protein expression was increased in gastrocnemius muscle homogenate from FST-injected mice [n=10 (8 males, 2 females)] compared with vehicle-injected controls [n=9 (6 males, 3 females),] at end point (Mann-Whitney, p=0.0004). (B) Left: Endogenous Mouse FST in Untreated Mice. Endogenous mouse FST protein expression showed a significant change over time in aged untreated C57BL/6J mice (Kruskal-Wallis test: p=0.0405). On multiple comparisons to 12 months (Dunn’s multiple comparison test), follistatin expression at 27 months was significantly increased versus 12 months (p=0.0231), but there was no significant difference between 24 versus 12 months (p=0.2054). [12 months: n=6 (3 males, 3 females); 24 months: n=9 (5 males, 4 females); 27 months: n=8 (4 males, 4 females)]. Right: Mouse FST following AAV9-FST. Endogenous mouse FST protein expression was similar between vehicle [n=9 (6 males, 3 females) and AAV9-FST treated mice [n=9 (4 males, 5 females)] (Mann-Whitney, p=0.7304). (C) Left: Endogenous Mouse FST in Untreated Mice. Endogenous mouse myostatin levels did not show statistically significant changes between 12 and 27 months of age in untreated mice (one way ANOVA, F (2, 16) = 3.097, p=0.0730, multiple comparisons to 12 months (Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test): 12 m vs 24: p=0.2039 and 12m vs 27m: p=0.8826 [12 months: n=4 (2 males, 2 females); 24 months: n=8 (4 males, 4 females); 27 months: n=7 (4 males, 3 females)] Right: Endogenous Mouse Myostatin following AAV9-FST. Mouse myostatin protein expression was similar between vehicle [n=6 (5 males, 1 female)] and AAV9-FST [n=4 (3 males, 1 female)] treated mice (unpaired t-test, p=0.4937). Data shown as mean ± standard deviation for mouse follistatin and as median ± 95% confidence interval for mouse and human FST. *** p<0.001 * p<0.05

AAV-FST injection resulted in significantly increased gastrocnemius muscle mass (Figure 3A). Similarly, the soleus (Figure 3B) and the triceps brachii (Figure 3C) demonstrated patterns of increased muscle mass in FST treated mice. To further explore the hypertrophy effect, we normalized the weights of the gastrocnemius, soleus, and triceps brachii of the FST injected mice to the respective mean control muscle weights, and we found that the ratios between the muscles of the FST treated mice were similar suggesting systemic hypertrophic effect (Figure 3D). We explored the relationship between human FST expression levels and gastrocnemius weight, but this did not show significant correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient, n=10, r= 0.08347, p=0.8187).

Figure 3. Injection of AAV9-FST increased muscle weights.

(A) AAV9-FST injected mice demonstrated significantly increased gastrocnemius muscle weight (unpaired t-test, p=0.0066). (B-C) Similar trends were seen in both the soleus (unpaired t-test, p=0.0682) and the triceps brachii (unpaired t-test, p=0.0883). (D) When ratios of muscle weights (to control mean) for gastrocnemius and triceps brachii AAV9-FST-injected mice were compared, there were no significant differences suggesting a similar systemic hypertrophy effect at the site of AAV9-FST injection and remotely (One Way ANOVA, F (2, 42) = 0.3365, p=0.7162). Data shown as mean ± standard deviation. (gastrocnemius and triceps brachii weights). Sample sizes: Vehicle n=13 (10 males, 3 females); AAV9-FST n=16 (10 males, 6 females). One outlier (vehicle male) removed from vehicle soleus weights. ** p<0.01

3.2. FST overexpression increased muscle torque but not when normalized to muscle mass

Longitudinal twitch and tetanic plantar flexion contractility testing are shown as absolute torque values and normalized to baseline values in Figures 4A–D. There was a significant interaction between time and treatment for increased twitch torque in the AAV9-FST treated mice (Figures 4A, 4B). Tetanic torque demonstrated significant reduction with time (loss of contractility with aging) (Figures 4C, 3D). Tetanic torque was increased with AAV9-FST treatment, but there was no significant interaction between time and treatment (Figures 4C, 3D). To analyze muscle quality, torque values were normalized to muscle mass at endpoint. Twitch torque normalized to soleus and gastrocnemius weight was significantly less at endpoint in the AAV9-FST injected mice versus controls (Figure 4E). In contrast, at endpoint tetanic torque normalized to gastrocnemius and soleus weight was not significantly different between treatment groups (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. Follistatin overexpression resulted in increased muscle contractility torque.

(A-B) Plantarflexion twitch contractility [shown as absolute (A) and normalized to baseline (B)] demonstrated no change with time (p=0.3931) or treatment alone (p=0.1624) but there was a significant increase of twitch over time in the AAV9-FST treated group (p=0.0089). (C-D) Tetanic contractility [shown as absolute (C) and normalized to baseline (D)] showed significant reduction over time (p=0.0482) and increase with follistatin treatment (p=0.0308) but no interaction between time and treatment (p=0.2183). (E) Muscle twitch torque normalized to gastrocnemius and soleus muscle weight was reduced in the AAV9-FST group compared with the vehicle treated group (p=0.0438). (F) Tetanic contractility normalized to weight of gastrocnemius and soleus muscle was unchanged between groups (p=0.2369). Mixed effect model was used to analyze longitudinal twitch and tetanic values. Unpaired t-test was used to compare twitch and tetanic normalized to muscle mass. Data shown as mean ± standard deviation. [For the longitudinal studies, n=17 mice (11 males, 6 females) per group; for normalized muscle torque at endpoint, n=13 in vehicle (10 males, 3 females) and n=14 in AAV9-FST group (8 males, 6 females)]. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01

3.3. FST overexpression increased summated muscle excitation but did not prevent age-related losses of motor units

Longitudinal CMAP responses demonstrated significant amplitude losses in both groups over time (loss of amplitudes with aging). CMAP amplitudes were significantly improved with AAV9-FST treatment when compared to vehicle-injected controls, but there was no significant interaction between time and treatment (Figure 5A). SMUP amplitude demonstrated significant change with time though the overall pattern was noted to variable. SMUP showed no change with treatment or interaction between time and treatment (Figure 5B). MUNE demonstrated significant losses of motor unit numbers over time but no significant change with treatment or interaction between treatment and time (Figure 5C). As CMAP amplitude can be impacted by hypertrophy and atrophy of muscle, we explored CMAP amplitude normalized to muscle size (Mobach et al., 2020; Molin and Punga, 2016). There was no significant difference for CMAP amplitude per gram of gastrocnemius and soleus weight when comparing mice injected with FST versus vehicle (Figure 5D) suggesting that hypertrophy might explain CMAP amplitude increase in the FST treated group.

Figure 5. Follistatin overexpression increases compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude but does not alter single motor unit potential size (SMUP) or motor unit number estimation (MUNE).

(A) CMAP amplitude demonstrated a significant decline with age (p<0.0001). Treatment with AAV9-FST resulted in increased amplitude compared with controls (p=0.0083), but there was no interaction between time and treatment (p=0.8412). (B) SMUP demonstrated a significant change with time (p=0.0150), no effect of treatment (p=0.4161) or interaction between time and treatment (p=0.5087). (C) MUNE demonstrated a significant reduction with time (p<0.0001) but no change with treatment (p=0.2062) or interaction with treatment over time (p=0.6018). (D) The CMAP amplitude when normalized to the weight of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscle demonstrated no significant differences between the vehicle and AAV9-FST treated groups (AAV9-FST n=15, vehicle n=12, p=0.4040). Mixed effect model was used to analyze longitudinal CMAP, SMUP, and MUNE. Unpaired t-test was used to analyze the CMAP data normalized to muscle weights. Data shown as mean ± standard deviation. Longitudinal studies: [n=17 mice (11 males, 6 females) per group.] * p<0.05

3.4. FST overexpression improved NMJ transmission and NMJ morphology

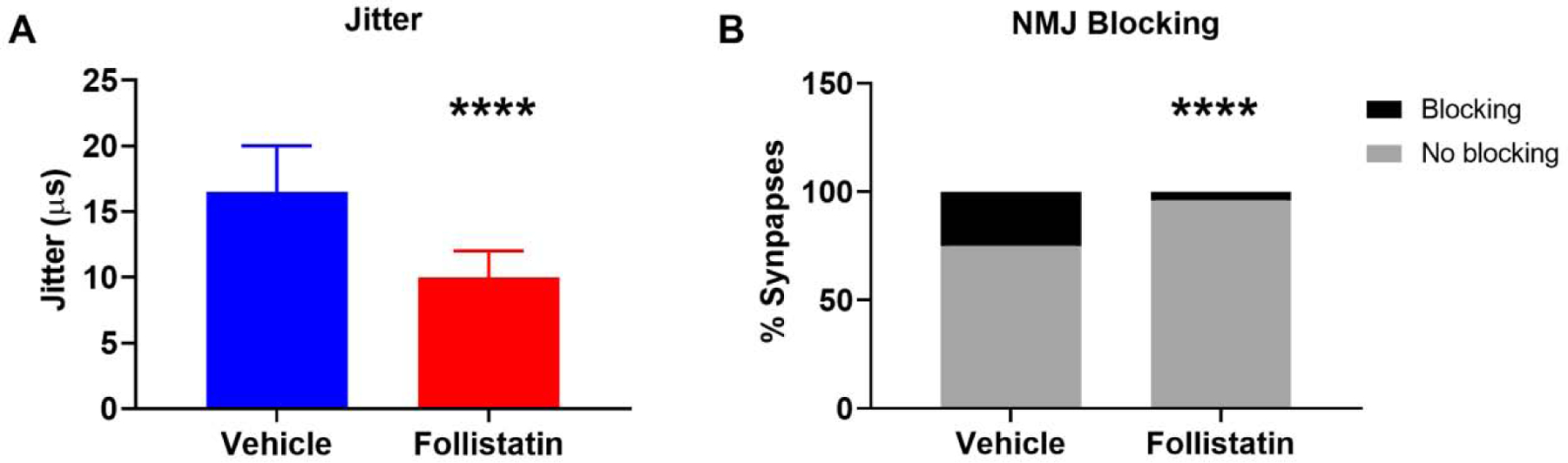

At endpoint (27 months), AAV9-FST injected mice showed significantly reduced jitter (median: 10.00 μs [95% CI: 9.00, 12.00] compared with Vehicle injected mice (median: 16.50 μs [95% CI: 13.00, 20.00] (Figure 6A). Similarly, there was a drastic reduction in blocking from 25% to 4% in the FST cohort as compared to the Vehicle cohort (Figure 6B). These results indicate a robust improvement in the reliability of NMJ transmission upon overexpression of FST in aged mice and significantly reduced NMJ failure. Furthermore, analyses of NMJ morphology with immunohistochemical staining of neurofilament + synapsin (red) to indicate the presynaptic nerve terminal and bungarotoxin (green) to indicate postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors, revealed a significant improvement in NMJ innervation upon follistatin injection (58.54% fully innervated NMJs in FST vs. 49% in Vehicle, Figures 7A and 7C). We also analyzed NMJ fragmentation but found no significant difference between the vehicle and FST groups (Figures 7B and 7D).

Figure 6. Neuromuscular junction transmission fidelity was improved with follistatin overexpression.

(A) Jitter was reduced in 27-months-old treated with AAV9-FST injection (median: 10 μs [95% CI: 12.30, 17.93] and mean: 15.12±17.14.96μs) compared with vehicle treated mice (median: 16.5 μs, [95% CI: 22.17, 31.25] and mean: 26.71 ± 24.01μs) (p<0.0001). (B) Blocking frequency was significantly reduced in the AAV9-FST injected cohort of mice (4%, 6 of 146 synapses, n=15 mice, 9 males, 6 females) as compared with vehicle treated mice (25%, 28 of 110 synapses, n=13 mice, 10 males, 3 females) (p<0.0001). Mann Whitney test was used to compare groups for jitter due to non-normal distribution. Fisher’s Exact test was used to compare frequency of blocking between group. Jitter data shown as median ± 95% confidence interval (CI). **** p<0.0001

Figure 7. NMJ morphology was improved following follistatin overexpression.

Immunohistochemistry of longitudinal sections of gastrocnemius muscle was performed to investigate NMJ morphology following follistatin overexpression. (A, B) Representative NMJ staining images of Vehicle and AAV9-FST groups of mice respectively. P represents partially innervation junctions, while F indicates fully innervated junctions. (C) Quantification of innervation status of junctions revealed that the AAV9-FST group had significantly higher number of fully innervated NMJs (p=0.0381). (D) There was no significant change in the fragmentation status of the NMJs upon injection of AAV9-FST, as compared to the vehicle injected group (p=0.0848). Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the categories of fully innervated versus not fully innervated and fragmented versus non-fragmented between the two groups of mice. (Neurofilament and synapsin = red, bungarotoxin = green, n=3 males per group) * p<0.05

4. DISCUSSION

In the current study, we investigated the effects of FST overexpression in C57BL/6J mice between the ages of 24 and 27 months. We confirmed that high levels of human FST expression were sustained following a one-time intramuscular gastrocnemius injection of AAV9-FST. FST overexpression resulted in significantly increased gastrocnemius muscle weight and plantarflexion torque production. The primary goal of the study was to investigate the neurobiological effects of muscle hypertrophy, induced via FST overexpression, on motor unit and NMJ function in aged mice. Longitudinal electrophysiological analyses demonstrated increased CMAP amplitude compared with vehicle injected controls consistent with increased summated muscle excitation likely due to muscle hypertrophy, but age-related losses of motor units were not different between groups. At endpoint, NMJ transmission on SFEMG and NMJ morphological assessments of innervation were significantly improved following three months of FST overexpression. Therefore, inducing FST overexpression did not lessen or exacerbate motor unit losses of aging, but did result in improvement of NMJ transmission and morphology.

Therapeutic development for sarcopenia has largely focused on methods for increasing muscle mass namely the inhibition of myostatin and related pathways. Despite consistent preclinical and clinical effects on muscle mass following myostatin inhibition, the effects on muscle strength and function have been more modest (White and LeBrasseur, 2014). We found robust improvements of NMJ transmission and morphology. We have previously shown that NMJ transmission failure is a later onset phenotype in aging mice that emerges at ~27 months of age and is not temporally related to motor unit losses (Chugh et al., 2020). In the current study, mice were injected with AAV9-FS344 at 24 months of age when no overt defects in NMJ transmission were observed in our previous study (Chugh et al., 2020). At the endpoint, 27 months of age, mice with FST overexpression demonstrated significantly improved NMJ transmission and morphology when compared with vehicle treated mice. As AAV9-FS344 was injected prior to onset of NMJ decline, it is possible that FST overexpression prevented NMJ disruption. Whether FST overexpression would improve regeneration or repair the NMJ after onset of NMJ defects as well as what mechanisms underlie FST’s impact on the NMJ are open questions.

We also demonstrated mild improvements in absolute muscle torque production in mice with FST overexpression. Previous studies of myostatin loss or FST overexpression have also shown a decrease in twitch and tetanic specific force (i.e. muscle force production normalized to muscle size) (Amthor et al., 2007; Bogdanovich et al., 2008; Giesige et al., 2018; Kota et al., 2009; Mendias et al., 2011). Similarly, we observed reduced muscle twitch torque normalized to muscle weight following FST overexpression. In contrast, we did not observe significant loss of normalized muscle torque (to muscle weight) during tetanic responses in FST treated mice. The differential effects on normalized twitch as compared with normalized tetanic are likely due, at least in part, to the improvements of NMJ transmission with FST overexpression. A prior clinical study by Becker and colleagues investigated a humanized monoclonal antibody designed to bind and neutralize myostatin in older adults with a history of falls (Becker et al., 2015). This study demonstrated a strong positive effect on lean mass in weaker older adults with a history of falls, but more modest effects on functional outcomes with only 2 of 9 functional outcomes showing significant improvement (Becker et al., 2015). In contrast, FST has not been previously studied in the context of sarcopenia, but two published studies investigated FST overexpression via AAV intramuscular injection in Becker muscular dystrophy and inclusion body myositis and have shown positive effects on lean mass and ambulation distance on the six-minute walk test (Al-Zaidy et al., 2015; Mendell et al., 2017). Future studies could investigate the effects of FST on function in the context of aging and sarcopenia.

One of the major goals of the current study was to assess the effects of FST overexpression on motor unit losses during aging. In contrast to the improvements noted on assessments of NMJ transmission, NMJ morphology, and muscle contractility, we did not observe any overt differences between treatment groups for age-related losses of motor unit numbers. The lack of effect on age-related decline of motor unit number is in line to one prior study where the authors investigated motor unit numbers following myostatin reduction in mice starting at 12 months of age but found no attenuation of age-related motor unit losses between 12 and 24 months of age; however assessment of NMJ transmission was not included in this study (Tavoian et al., 2019). Similarly, no effect on motor unit numbers was observed following myostatin/activin inhibition in a mouse model of the autosomal recessive motor neuron disorder, spinal muscular atrophy (Liu et al., 2016). These studies, together with our current findings, therefore, suggest that postnatal modulation of myostatin pathway may not directly affect motor unit degeneration. From our findings it could be speculated that motor neuron losses are related to degenerative effects within cell bodies of motor neurons that are independent of signaling from muscle via the NMJ. However, it remains possible that an earlier treatment with FST could have more impact on age-related losses of motor units because in the current study, FST overexpression was initiated at 24 months, approximately 4 months after motor unit losses are first observed in aging C57BL/6J mice (Sheth et al., 2018). It has been hypothesized that motor neuronal dysfunction and motor unit “dying back” might explain defects at the NMJ (Manini et al., 2013). In our prior experiments, we showed that motor unit loss and NMJ dysfunction are not temporally related possibly suggesting distinct pathophysiological processes at the motor unit and the NMJ (Chugh et al., 2020). In our current experiments, the effect on NMJ morphology and transmission without impact on motor unit number add further evidence that NMJ defects may not be directly attributed to a common upstream motoneuronal defect.

In our studies, we also investigated the endogenous levels of mouse FST levels across the mouse lifespan and found that endogenous FST expression was increased in very old mice at 27 months. Perhaps coincidentally, this increase in FST expression in aged C57BL/6J mice corresponded to the age of onset of NMJ transmission failure in our prior NMJ study (Chugh et al., 2020). Increased follistatin expression has also been observed in genetic and acquired neuromuscular disorders, and the patients with the most severe muscle wasting demonstrated the most robust downregulation of the myostatin pathway with increases of FST (Mariot et al., 2017). Since muscle wasting occurs in sarcopenia, it is possible that either FST expression increases in very old age as a compensatory mechanism in response to impaired NMJs or there is an increased requirement of FST to maintain failing NMJs in very old ages. The mechanism by which FST led to improvement of NMJ transmission and innervation warrants further studies. Prior work in drosophila has shown that myostatin inhibits NMJ strength and composition, affects synapse formation in culture, and inhibits synaptic transmission between neurons in the escape response neural circuit of adult flies (Augustin et al., 2017). A recent study showed that administration of activin receptor, a strong myostatin inhibitor, did not change the NMJ morphology (Boido et al., 2020). In our study, we found no differences in NMJ fragmentation between groups, but we did find increased NMJ innervation. Whether the NMJ improvements we observed with FST overexpression occurred via myostatin inhibition is unclear. A potential pleotropic effect of FST on the NMJ (i.e. independent of myostatin inhibition) is possible. Therefore, future studies could be designed to determine whether selective inhibition of myostatin has a similar impact on the NMJ as compared with FST overexpression.

Currently, sarcopenia is primarily managed with exercise and nutrition interventions (Hardee and Lynch, 2019, Hunter 2004, McPhee 2016, Beaudart 2017). In a parallel study, we combined voluntary running exercise with FST overexpression in aged mice to investigate the possibility of additive or synergistic effects (Chugh et al., 2021). The overall goal of that study was to investigate the effects of exercise, one of the primary treatments of sarcopenia, on motor unit function in aging mice. In that study, mice housed with voluntary running wheels alone (without FST overexpression) demonstrated improvements of NMJ transmission similar to those in mice treated with AAV-FST in the current study. Interestingly, when FST overexpression was combined with voluntary running wheel exercise there were no additive or synergistic effects. Together, the findings of these two studies suggest that FST treatment may not be beneficial in individuals that are able to exercise. In the current studies we did not test FST in the context of immobilization or disuse atrophy. FST treatment may be more relevant for older adults affected by muscle disuse or immobilization related to injury, hospitalization, or other contraindication to exercise. Following injury or hospitalization, recovery is often slow or incomplete in older adults (Creditor, 1993; Hansen et al., 1999; Sager et al., 1996). Future studies could investigate FST as a therapeutic intervention following immobilization.

Highlights.

Follistatin overexpression was studied in aged mice between 24 to 27 months of age

Follistatin increased muscle size and absolute torque production in aged mice

Normalized twitch torque, but not tetanic torque, was reduced with follistatin

Follistatin improved neuromuscular junction transmission but not motor unit loss

Endogenous mouse follistatin but not myostatin was increased in aged mice

Funding:

R03 GEMSSTAR grant Funding to WDA and The Ohio State University College of Medicine Roessler Medical Student Research Scholarship to AY. Images presented in this report were generated using the instruments and services at the Neuroscience Imaging Core, The Ohio State University. This facility is supported in part by grants P30 CA016058, and S10 OD010383.

Abbreviations.

- FST

follistatin

- NMJ

neuromuscular junction

- CMAP

compound motor action potential

- MUNE

motor unit number estimate

- SFEMG

single fiber electromyography

- SMUP

single motor unit potential

- MU

motor units

- AAV9

self-complementary Adeno-associated virus subtype 9

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interests to report.

REFERENCES

- Al-Zaidy SA, Sahenk Z, Rodino-Klapac LR, Kaspar B, Mendell JR, 2015. Follistatin Gene Therapy Improves Ambulation in Becker Muscular Dystrophy. Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 2, 185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor H, Macharia R, Navarrete R, Schuelke M, Brown SC, Otto A, Voit T, Muntoni F, Vrbóva G, Partridge T, Zammit P, Bunger L, Patel K, 2007. Lack of myostatin results in excessive muscle growth but impaired force generation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(6), 1835–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WD, Sheth KA, Wier CG, Kissel JT, Burghes AH, Kolb SJ, 2015. Electrophysiological Motor Unit Number Estimation (MUNE) Measuring Compound Muscle Action Potential (CMAP) in Mouse Hindlimb Muscles. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE(103). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin H, McGourty K, Steinert JR, Cochemé HM, Adcott J, Cabecinha M, Vincent A, Halff EF, Kittler JT, Boucrot E, Partridge L, 2017. Myostatin-like proteins regulate synaptic function and neuronal morphology. Development 144(13), 2445–2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balice-Gordon R, Lichtman J, 1990. In vivo visualization of the growth of pre- and postsynaptic elements of neuromuscular junctions in the mouse. The Journal of Neuroscience 10(3), 894–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyère O, Cesari M, Rolland Y, Rizzoli R, Araujo de Carvalho I, Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan J, Bautmans I, Bertière M-C, Brandi ML, Al-Daghri NM, Burlet N, Cavalier E, Cerreta F, Cherubini A, Fielding R, Gielen E, Landi F, Petermans J, Reginster J-Y, Visser M, Kanis J, Cooper C, 2016. Sarcopenia in daily practice: assessment and management. BMC Geriatr 16(1), 170–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Lord SR, Studenski SA, Warden SJ, Fielding RA, Recknor CP, Hochberg MC, Ferrari SL, Blain H, Binder EF, Rolland Y, Poiraudeau S, Benson CT, Myers SL, Hu L, Ahmad QI, Pacuch KR, Gomez EV, Benichou O, Group S, 2015. Myostatin antibody (LY2495655) in older weak fallers: a proof-of-concept, randomised, phase 2 trial. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology 3(12), 948–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanovich S, McNally EM, Khurana TS, 2008. Myostatin blockade improves function but not histopathology in a murine model of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2C. Muscle Nerve 37(3), 308–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boido M, Butenko O, Filippo C, Schellino R, Vrijbloed JW, Fariello RG, Vercelli A, 2020. A new protein curbs the hypertrophic effect of myostatin inhibition, adding remarkable endurance to motor performance in mice. PloS one 15(3), e0228653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh D, Iyer CC, Bobbili P, Blatnik AJ, Kaspar BK, Meyer K, Burghes AHM, Clark BC, Arnold WD, 2021. Voluntary Wheel Running with and without Follistatin Overexpression Improves NMJ Transmission but not motor unit loss in Late Life of C57BL/6J Mice. Neurobiology of Aging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh D, Iyer CC, Wang XY, Bobbili P, Rich MM, Arnold WD, 2020. Neuromuscular junction transmission failure is a late phenotype in aging mice. Neurobiology of Aging 86, 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh D, Nilsson P, Afjei S-A, Bakochi A, Ekdahl CT, 2013. Brain inflammation induces post-synaptic changes during early synapse formation in adult-born hippocampal neurons. Experimental Neurology 250, 176–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BC, Manini TM, 2010. Functional consequences of sarcopenia and dynapenia in the elderly. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care 13(3), 271–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creditor MC, 1993. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med 118(3), 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalakas MC, 1995. Pathogenetic Mechanisms of Post-Polio Syndrome: Morphological, Electrophysiological, Virological, and Immunological Correlations. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 753(1), 167–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalakas MC, Elder G, Hallett M, Ravits J, Baker M, Papadopoulos N, Albrecht P, Sever J, 1986. A long-term follow-up study of patients with post-poliomyelitis neuromuscular symptoms. The New England journal of medicine 314(15), 959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbono O, 2003. Neural control of aging skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 2(1), 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Sengupta P, 2016. Men and mice: Relating their ages. Life Sciences 152(Supplement C), 244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco O, Ferrini A, Santoro M, Lo Monaco MR, Gambassi G, Cesari M, 2012. Physical function and perceived quality of life in older persons. Aging clinical and experimental research 24(1), 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesige CR, Wallace LM, Heller KN, Eidahl JO, Saad NY, Fowler AM, Pyne NK, Al-Kharsan M, Rashnonejad A, Chermahini GA, Domire JS, Mukweyi D, Garwick-Coppens SE, Guckes SM, McLaughlin KJ, Meyer K, Rodino-Klapac LR, Harper SQ, 2018. AAV-mediated follistatin gene therapy improves functional outcomes in the TIC-DUX4 mouse model of FSHD. JCI Insight 3(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goates S, Du K, Arensberg MB, Gaillard T, Guralnik J, Pereira SL, 2019. Economic Impact of Hospitalizations in US Adults with Sarcopenia. The Journal of frailty & aging 8(2), 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet AM, Rizo L, Handy C, Umapathi P, Eagle A, Shilling C, Boue D, Martin PT, Sahenk Z, Mendell JR, Kaspar BK, 2008. Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105(11), 4318–4322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy CR, 2009. Follistatin Gene Therapy for the Treatment of Muscular Dystrophy, Integrated Biomedical Science. The Ohio State University, OhioLINK, p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K, Mahoney J, Palta M, 1999. Risk factors for lack of recovery of ADL independence after hospital discharge. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47(3), 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardee JP, Lynch GS, 2019. Current pharmacotherapies for sarcopenia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 20(13), 1645–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter GR, McCarthy JP, Bamman MM, 2004. Effects of resistance training on older adults. Sports Med 34(5), 329–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R, 2004. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(1), 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota J, Handy CR, Haidet AM, Montgomery CL, Eagle A, Rodino-Klapac LR, Tucker D, Shilling CJ, Therlfall WR, Walker CM, Weisbrode SE, Janssen PML, Clark KR, Sahenk Z, Mendell JR, Kaspar BK, 2009. Follistatin gene delivery enhances muscle growth and strength in nonhuman primates. Science translational medicine 1(6), 6ra15–16ra15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Hammers DW, Barton ER, Sweeney HL, 2016. Activin Receptor Type IIB Inhibition Improves Muscle Phenotype and Function in a Mouse Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. PloS one 11(11), e0166803–e0166803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manini TM, Hong SL, Clark BC, 2013. Aging and muscle: a neuron’s perspective. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care 16(1), 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariot V, Joubert R, Hourdé C, Féasson L, Hanna M, Muntoni F, Maisonobe T, Servais L, Bogni C, Le Panse R, Benvensite O, Stojkovic T, Machado PM, Voit T, Buj-Bello A, Dumonceaux J, 2017. Downregulation of myostatin pathway in neuromuscular diseases may explain challenges of anti-myostatin therapeutic approaches. Nature communications 8(1), 1859–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhail S, Beller E, Haines T, 2010. Physical function and health-related quality of life of older adults undergoing hospital rehabilitation: how strong is the association? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 58(12), 2435–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, Degens H, 2016. Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 17(3), 567–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell JR, Sahenk Z, Al-Zaidy S, Rodino-Klapac LR, Lowes LP, Alfano LN, Berry K, Miller N, Yalvac M, Dvorchik I, Moore-Clingenpeel M, Flanigan KM, Church K, Shontz K, Curry C, Lewis S, McColly M, Hogan MJ, Kaspar BK, 2017. Follistatin Gene Therapy for Sporadic Inclusion Body Myositis Improves Functional Outcomes. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 25(4), 870–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendias CL, Kayupov E, Bradley JR, Brooks SV, Claflin DR, 2011. Decreased specific force and power production of muscle fibers from myostatin-deficient mice are associated with a suppression of protein degradation. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) 111(1), 185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messi ML, Delbono O, 2003. Target-derived trophic effect on skeletal muscle innervation in senescent mice. J Neurosci 23(4), 1351–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobach T, Brooks J, Breiner A, Warman-Chardon J, Papp S, Gammon B, Nandedkar SD, Bourque PR, 2020. Impact of disuse muscular atrophy on the compound muscle action potential. Muscle & Nerve 61(1), 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molin CJ, Punga AR, 2016. Compound Motor Action Potential: Electrophysiological Marker for Muscle Training. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 33(4), 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodino-Klapac LR, Haidet AM, Kota J, Handy C, Kaspar BK, Mendell JR, 2009. Inhibition of myostatin with emphasis on follistatin as a therapy for muscle disease. Muscle Nerve 39(3), 283–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg IH, 1989. Summary comments. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 50(5 SUPPL.), 1231–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg IH, 2011. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. Clin Geriatr Med 27(3), 337–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager MA, Franke T, Inouye SK, Landefeld CS, Morgan TM, Rudberg MA, Sebens H, Winograd CH, 1996. Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons. Archives of internal medicine 156(6), 645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer AA, Robinson SM, Patel HP, Shavlakadze T, Cooper C, Grounds MD, 2013. New horizons in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of sarcopenia. Age and Ageing 42(2), 145–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth KA, Iyer CC, Wier CG, Crum AE, Bratasz A, Kolb SJ, Clark BC, Burghes AHM, Arnold WD, 2018. Muscle strength and size are associated with motor unit connectivity in aged mice. Neurobiol Aging 67, 128–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimasaki S, Koga M, Esch F, Cooksey K, Mercado M, Koba A, Ueno N, Ying SY, Ling N, Guillemin R, 1988. Primary structure of the human follistatin precursor and its genomic organization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 85(12), 4218–4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalberg E, Trontelj JV, 1997. The study of normal and abnormal neuromuscular transmission with single fibre electromyography. Journal of neuroscience methods 74(2), 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangl MK, Böcker W, Chubanov V, Ferrari U, Fischereder M, Gudermann T, Hesse E, Meinke P, Reincke M, Reisch N, Saller MM, Seissler J, Schmidmaier R, Schoser B, Then C, Thorand B, Drey M, 2019. Sarcopenia - Endocrinological and Neurological Aspects. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 127(1), 8–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavoian D, Arnold WD, Mort SC, de Lacalle S, 2019. Sex differences in body composition but not neuromuscular function following long-term, doxycycline-induced reduction in circulating levels of myostatin in mice. PloS one 14(11), e0225283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TA, LeBrasseur NK, 2014. Myostatin and Sarcopenia: Opportunities and Challenges - A Mini-Review. Gerontology 60(4), 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wier CG, Crum AE, Reynolds AB, Iyer CC, Chugh D, Palettas MS, Heilman PL, Kline DM, Arnold WD, Kolb SJ, 2019. Muscle contractility dysfunction precedes loss of motor unit connectivity in SOD1(G93A) mice. Muscle Nerve 59(2), 254–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]