Abstract

Objectives:

To investigate the relationship between frailty and treatment response to antidepressant medications in adults with late life depression (LLD).

Methods:

Data were evaluated from 100 individuals over age 60-years (34 men, 66 women) with a depressive diagnosis, who were assessed for frailty at baseline (characteristics include gait speed, grip strength, activity levels, fatigue, and weight loss) and enrolled in an 8-week trial of antidepressant medication followed by 10-months of open-treatment.

Results:

Frail individuals (n=49 with ≥ 3 deficits in frailty characteristics) did not differ at baseline from the non/intermediate frail (n=51 with 0-2 deficits) on demographic, medical comorbidity, cognitive, or depression variables. On average, frail individuals experienced 2.82 fewer Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) points of improvement (t=2.12, df 89, P = .037) than the non/intermediate frail over acute treatment, with this difference persisting over 10- months of open-treatment. Weak grip strength and low physical activity levels were each associated with decreased HRSD improvement, and lower response and remission rates over the course of the study. Despite their poorer outcomes, frail individuals received more antidepressant medication trials than the non/intermediate frail.

Conclusions:

Adults with LLD and frailty have an attenuated response to antidepressant medication and a greater degree of disability compared to non/intermediate frail individuals. This disability and attenuated response remain even after receiving a greater number of antidepressant medication trials. Future research must focus on understanding the specific pathophysiology associated with the frail-depressed phenotype to permit the design and implementation of precision medicine interventions for this high-risk population.

Late life depression (LLD) affects as many as 25% of adults over the age of 60, the most rapidly growing demographic group in the United States.1 Depressed older adults incur greater personal, social, and economic costs in part because treatment resistance is substantially more common relative to younger adults.2,3 Moreover, treatment outcomes of LLD are dismal, with high recurrence rates.4,5 The heterogeneity of LLD has stimulated work to identify clinical dimensions and corresponding biological processes6 that may be responsible for these negative outcomes. Leveraging geroscience7 may elucidate distinct pathophysiologic mechanisms, delineate corresponding phenotypes, and identify novel therapeutic targets which can then be used to implement personalized treatment strategies to alter the dire clinical trajectory associated with LLD.8

Frailty, a syndrome of bioenergetic deficiency defined clinically by diminished strength and physical activity, fatigue, slowed mobility, and unintentional weight loss, is bidirectionally associated with LLD9 and, when comorbid with LLD, leads to increased mortality risk.10 Specific physical deficits of frailty including slow gait speed and weak grip strength are highly comorbid in adults with LLD, associated with greater depressive symptom severity, and do not appear to be associated with known subtypes of LLD such as vascular depression (as measured by both white matter hyperintensity [WMH] burden and corresponding executive dysfunction).11 Frailty comorbid with LLD may represent accelerated biological aging, and a number of mechanisms such as mitochondrial dysfunction and dopaminergic depletion have been postulated to explain the frailty-depression intersection.12

The overall aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between frailty and antidepressant treatment response in adults with LLD. Specifically, we sought to examine whether baseline frailty burden and specific frailty deficits are associated with depression symptom change and change in disability in acute and long-term trials of antidepressant medications in adults with LLD, and explored whether frailty status was associated with response and remission rate as well. To our knowledge, this is the first study designed to measure the relationship between frailty and response to antidepressant medications in adults with LLD.

METHODS

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Participants evaluated between June 2013 and December 2018 entered ongoing antidepressant treatment protocols at the Clinic for Aging, Anxiety, and Mood Disorders (CAAM) at the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI). Individuals were required to be ≥ 60 years of age with a diagnosis of either Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD) and have a rater-administered 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HRSD) ≥ 16. Participants were excluded if they suffered from an acute, unstable, or severe medical illness, had significant cognitive impairment (30-item Mini Mental State Exam [MMSE] < 24) or a diagnosis of dementia, history of psychosis or bipolar disorder, or were diagnosed with substance abuse or dependence in the last 12-months prior to evaluation.

TREATMENT

Participants were treated with antidepressant medication (escitalopram or duloxetine) either openly or in a placebo-controlled 8-week trial, during which they were seen weekly for clinical management. Following the 8-week acute trial, participants were eligible to continue in open-treatment for an additional 10-months. During this 10-month period, participants were treated as clinically indicated, using both switch and augmentation strategies. Major assessment points included baseline, 8-weeks, and 6- and 12-months. The treatment provided in this study was part of two registered clinical trials on clincialtrials.gov, NCT01931202 and NCT01973283.

ASSESSMENT MEASURES DEPRESSION

An initial diagnosis of a depressive disorder was obtained at evaluation from the rater-administered Structured Clinical Interview Diagnostic for DSM 5 (SCID), and severity was assessed by the rater-administered 24-item HRSD.13 Response is defined as a 50% reduction in baseline HRSD score; remission as a HRSD score < 10.

FRAILTY CHARACTERISTICS

Participants’ average gait speed (m/s) was derived from two trials of usual walking speed, with < 1 m/s defining frailty level impairment.14 A dynamometer was used to assess grip strength (three trials in dominant hand unless dominant hand was compromised), with average grip strength (kgf) recorded and gender-specific cut-scores used (≤ 32 for males, ≤ 21 for females). Self-report of significant unintentional weight loss in the last year (≥ 10 lbs or 5% of their body weight) was recorded. Physical activity was measured using the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire, with < 1000 kcal/week defining frailty level inactivity. Fatigue was measured by two exhaustion-items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D15). These items are scored 0-3, with a response of ≥ 2 on either denoting fatigue.

Individuals were coded as having a frailty deficit at pre-treatment baseline using clinically-significant cut-points.16 The original frailty criteria, specifically for grip strength, gait speed, and physical activity levels, were based on the lowest quintile from subjects in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Since then, more clinically relevant cut-scores to define slow gait speed (< 1 m/s) and low physical activity levels (< 1000 kcal/week) have been identified as more appropriate for use in an outpatient setting such as the one in this study.11 Frailty burden is categorized as non-frail (0 deficits), intermediate frail (1-2 deficits), and frail (≥ 3 deficits).

DISABILITY

The secondary outcome for this trial was disability, defined using the 36-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0). The WHODAS 2.0 is a self-report measure of daily functioning (cognition, mobility, self-care, socialization, life activities, and participation in community activities) with higher total scores denoting greater disability.17

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

We summarized study variables and stratified by baseline frailty status using means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges for numerical variables or frequencies and proportions for categorical variables, with group comparisons for the fomer using t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests and the latter using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests.

To address the primary aim, we fit a linear mixed effects model with a subject-specific random intercept to account for within-subject correlation among repeated observations, with HRSD as the response and baseline frailty, visit (3-level categorical variable for 8-weeks, 6-, and 12-months), baseline HRSD, age, sex, education, number of medical comorbidities, and randomization arm (placebo-controlled or open-label to control for potentially higher response in open- compared to placebo-controlled trials) as predictors. The K-nearest neighbors’ algorithm (K=5) was used to impute missing values for a subset of participants missing values on a few covariates (17 subjects in the total sample and 12 in the sample with complete baseline frailty information were missing years of education; 9 subjects in the total sample and 3 in the sample with complete baseline frailty information were missing medical comorbidity data). Model parameters were estimated for all subjects with at least one post-baseline HRSD score and complete baseline frailty information (for individual frailty deficit models, participants with partial baseline frailty information were included). An effect size estimate akin to a Cohen’s d was calculated using the adjusted difference estimated from the model and dividing it by the pooled standard deviation of the HRSD scores at each post-baseline visit. Missing values in the response variables were treated as missing at random.18 A similar strategy was used for response and remission at 8-weeks, 6-, and 12-months, with logistic mixed effects models fit with a random subject-specific intercept. For logistic models, marginal (population-averaged) effects were estimated using methods proposed in Hedeker and colleagues.19

The same modeling approaches were used to assess the association between HRSD scores (and response/remitter outcomes) and individual frailty deficits, with each deficit considered in a separate covariate-adjusted model. For each, the sample comprises subjects with at least one post-baseline HRSD score and complete data for each individual frailty predictor. As the goal was to assess the association between frailty and response to antidepressant medication, we set the 8-week HRSD and WHODAS scores to missing for subjects who received placebo in the 8-week acute trial, thereby excluding the 8-week scores for subjects treated with placebo from the analysis. All tests were two-sided at a significance level α = .05. We used R (R Foundation) version 4.0.0 and the lme4 and GLMMadaptive packages for analyses.20–22

RESULTS

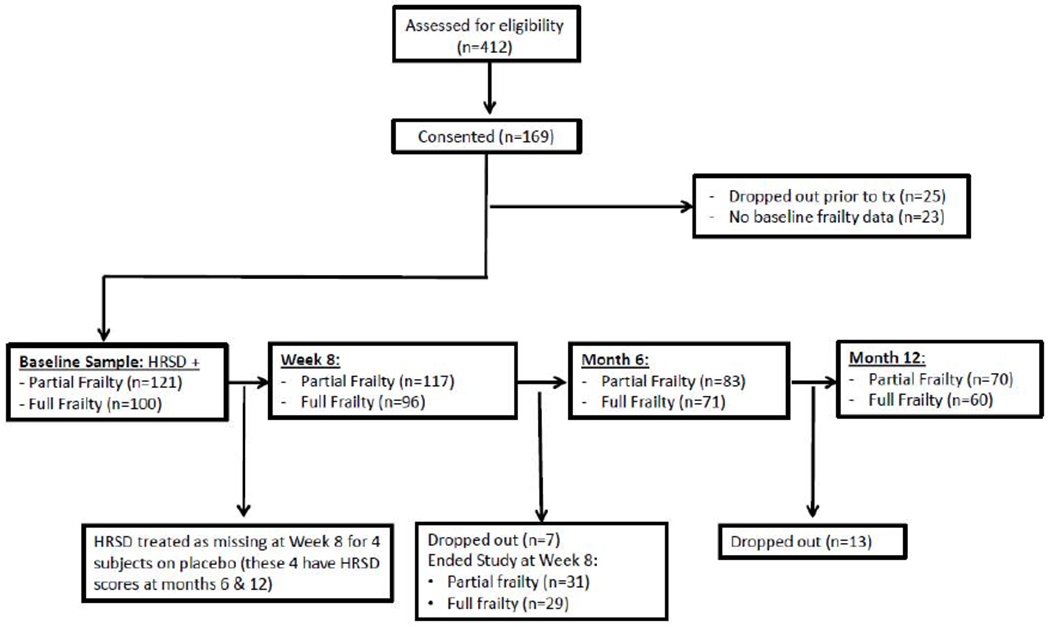

A total of 121 adults with LLD were evaluated, completed depression assessments, and at least partially completed assessment of frailty characteristics (Figure 1). Of these 121, 100 had complete baseline frailty measures performed, entered a treatment-protocol, and had at least one post-baseline HRSD assessment. These data were used in the primary analyses. Baseline demographic and clinical variables are listed in Table 1. As only three participants were classified as non-frail (no frailty deficits), the non-frail and intermediate frail (1-2 frailty deficits) were combined for all subsequent comparisons and analyses. The most common characteristic in the intermediate frail was fatigue, with 61% of the intermediate-frail group reporting fatigue at baseline in this group. The frail group (n=49 with ≥ 3 deficits) did not differ from the non/intermediate frail group (n=51 with 0-2 deficits) on any demographic variables, medical comorbidity burden, cognition, or depression severity (Table 1). The frail group exhibited slower gait speed, weaker grip strength, lower physical activity levels, and a greater prevalence of exhaustion and significant weight loss compared with the non/intermediate frail group. Additionally because individual frailty deficits and specific depressive symptoms may phenomenologically overlap (gait speed with psychomotor retardation HRSD item, physical activity levels with work and activity HRSD item, objective weight loss with loss of weight HRSD item, and exhaustion with anergia HRSD item), we tested these possibilities. No such overlap was observed (See Supplement) and thus we did not adjust HRSD scores to account for such overlap in the main analyses.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram with timing of assessments.

Note. The figure displays the number of individuals assessed for eligibility, consented for participation, assessed at baseline, and who were assessed at major assessment points following treatment initiation (Week 8, Month 6, and Month 12). The figure also differentiates sample sizes of those individuals who completed the assessment of fewer than five frailty characteristics at baseline (partial frailty) and those who completed all five characteristics at baseline (frailty) at each major time point. Also noted in the consort is that only four patients actually were assigned to placebo in the 8-week placebo-controlled trial. This unequal randomization was part of the study design for that trial, and given that this study was examining the relationship between frailty burden and response to antidepressant medication, the HRSD scores for these four participants were treated as missing at 8-weeks.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for adults with late life depression who completed frailty assessments at baseline

| Variable | Sample size available | Total sample (n = 100) | Non-frail/Intermediate (n = 51) | Frail (n = 49) | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years | 100 | 70.56 (7.59) | 69.50 (6.37) | 71.67 (8.60) | t (98) = −1.44, P = 0.154 |

| Gender, # Female (% Female) | 100 | 66 (66%) | 34 (66.7%) | 32 (65.3%) | χ2(1) = 0.00, P = 1.000 |

| Education, years | 88 | 16.39 (2.76) | 16.74 (2.96) | 16.00 (2.50) | t (86) = 1.26. P = 0.212 |

| Ethnicity, # Hispanic (% Hispanic) | 99 | 12 (12%) | 4 (8%) | 8 (16.3%) | χ2(1) = .92, P = 0.337 |

| Race, # Caucasian/Other (% Caucasian) | 92 | 68/24 (73.9%) | 36/12 (75.0%) | 32/12 (72.7%) | χ2 = 0.00, P = 0.992 |

| Medical burden | 98 | 4.59 (2.49) | 4.24 (2.41) | 4.94 (2.54) | t (96) = −1.39, P = 0.168 |

| Depression | |||||

| HRSD | 100 | 20.32 (5.84) | 19.67 (5.73) | 21.00 (6.61) | t (98) = −1.08, P = 0.283 |

| Diagnosis, # MDE/PDD (% MDE) | 97 | 89/11 (91.8%) | 45/4 (91.8%) | 44/4 (91.7%) | P = 1.000* |

| # of episodes | 60 | 1 [1, 3] | 1 [1, 3] | 1 [1, 2] | U = 503, P = 0.332 |

| Length of current, years | 82 | 0.14 [0.07, 0.55] | 0.14 [0.05, 0.43] | 0.25 [0.07, 0.73] | U = 703.5, P = 0.206 |

| Age of first onset, years | 85 | 37.79 (23.99) | 36.41 (21.63) | 39.27 (26.49) | t (83) = −0.55, P = 0.586 |

| Frailty | |||||

| Gait, m/s | 100 | 1.00 (0.26) | 1.15 (.22) | 0.85 (.22) | t (98) = 6.90, P < .001 |

| # (%) Gait < 1 m/s | 100 | 44 (44%) | 8 (15.7%) | 36 (73.5%) | χ2(1) = 31.56, P = .001 |

| Grip ave strength, kg force | 100 | 24.59 (9.73) | 28.57 (9.66) | 20.45 (7.98) | t (98) = 4.57, P < .001 |

| Frailty grip, # Frail (%) | 100 | 54 (54%) | 15 (29.4%) | 39 (79.6%) | χ2(1) = 23.35. P < .001 |

| Physical Activity, kcal/wk | 100 | 963.84 [436.28, 2285.94] | 2081.45 [1069.48, 2924.34] | 604.18 [222.11, 871.29] | U = 2024, P < .001 |

| Activity < 1000 kcal=/wk | 100 | 50 (50%) | 12 (23.5%) | 38 (77.6%) | χ2(1) = 27.05, P < .001 |

| Weight loss, # (% WL) | 100 | 31 (31%) | 10 (19.6%) | 21 (42.9%) | χ2(1) = 5.27, P = .022 |

| Fatigue, No. (% Fatigue) | 100 | 74 (74%) | 31 (60.8%) | 43 (87.8) | χ2(1) = 8.10, P = .004 |

| Neuropsychological function | |||||

| MMSE | 99 | 29 [28, 30] | 29 [28, 30] | 28 [27, 29] | U = 1431.5, P = .136 |

Note. For all categorical variables, frequencies and proportions are presented. Mean (sd) is presented for each numerical variable with a t-test statistic shown while median [IQR] is presented for each variable with Mann-Whitney U test statistic shown. Abbreviations: Non-Frail (0 characteristics, n = 3), Intermediate Frail (1-2 characteristics, n = 48), and Frail (≥ 3 characteristics, n =49); HRSD, Total score on the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MDE, Major Depressive Episode; PDD, Persistent Depressive Disorder; m/s, meters per second; kg force, kilograms of force; kcal/wk, kilocalories per week; WL, weight loss; MMSE, 30-item Mini-Mental State Exam; s, seconds; cm3 cubic centimeters, t(df) is the t-test statistics on df degrees of freedom, χ2(1) is the Chi-squared test statistic on 1 degree of freedom, U is the Mann-Whitney U test statistic, and p = p-value.

p-value from Fisher’s Exact test.

Of the 100 participants with complete baseline frailty and a post-baseline HRSD score, 96 completed 8-weeks of treatment (Figure 1). Of these 96, 29 ended participation following 8-weeks of treatment; 71 continued to receive treatment past 8-weeks. The 29 who ended participation at 8-weeks were older (73.38 ± 8.41 vs. 69.41 ± 6.96; t=2.44, df 98, P = .017) than those who continued, but did not differ on any other demographic variable, baseline HRSD, medical comorbidity or frailty characteristic (See Supplement). Additionally, there were no differences in Week 8 HRSD scores between those who concluded participation at 8-weeks and those who remained in treatment during the continuation phase (8-week HRSD: 12.90 ± 8.66 vs. 13.49 ± 7.60; t=−0.34, df 94, P = 0.736), nor were there a differences in 8-week response (34.5% vs. 38.8%; χ2=0.030, dj=1, P = .863) or remission rates (34.5% vs. 37.3%, χ2=0.001, df=1, P = .973).

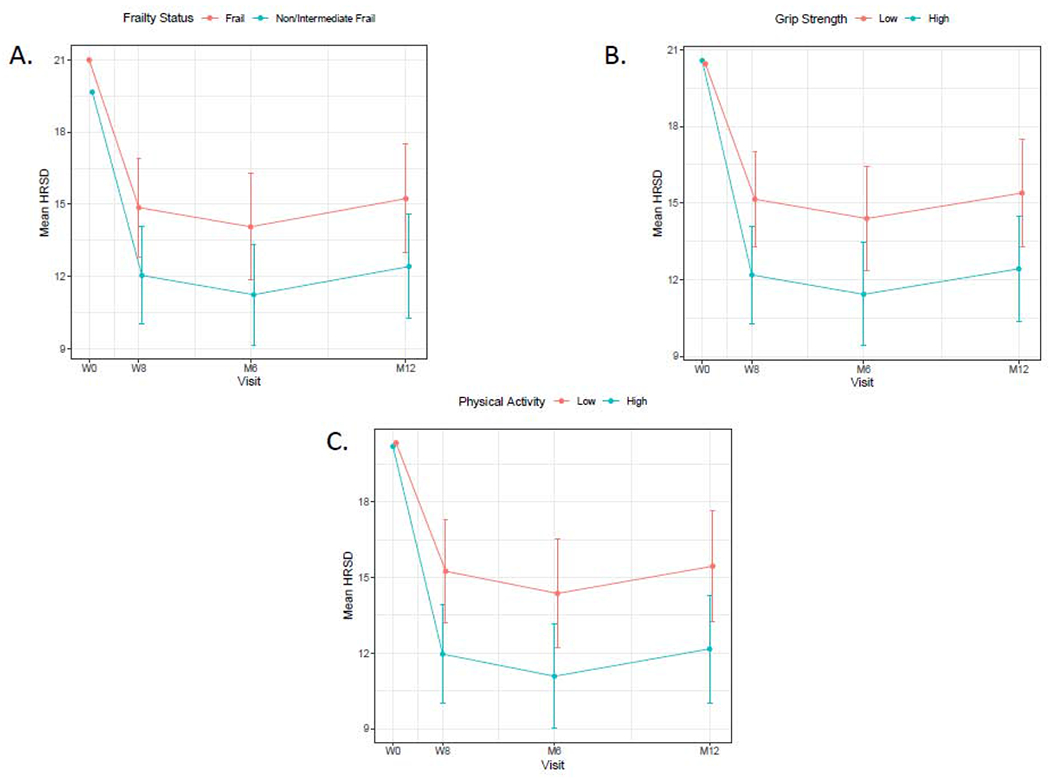

ANTIDEPRESSANT TREATMENT RESPONSE AS A FUNCTION OF OVERALL FRAILTY BURDEN

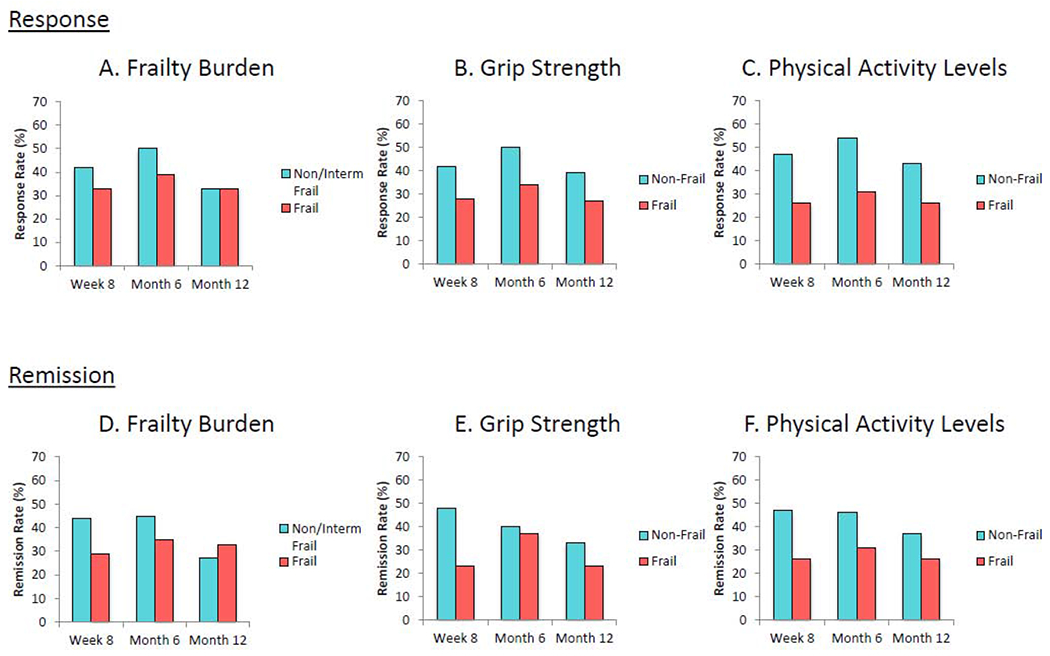

Figure 2A shows the model-based mean HRSD scores for the frail and non/intermediate frail subjects at 8-weeks, 6-months, and 12-months. Frail individuals showed an average HRSD score 2.82 points higher ([0.46, 5.46], t=2.12, df 89, P = .037) than the non/intermediate frail individuals over 8-weeks of acute treatment, with this difference persisting over the entire study follow-up period. This corresponds to Cohen’s d values of 0.36, 0.38, and 0.37 at 8-weeks, 6-months, and 12-months respectively. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic mixed effects models were used to assess associations between frailty burden and response/remission rates. As depicted in Figure 3A, following 8-weeks of acute treatment 33% of the frail group responded to antidepressant medication compared with 42% of the non/intermediate frail group, although differences in response rates between the two groups did not significantly differ at 8-weeks, 6-months, or 12-months, OR = 0.61 (0.30, 1.25), z = −1.34, P = .18. Similarly, although frail participants had remission rates 10-15% lower than non/intermediate frail participants at 8-weeks and 6-months (Figure 3D), there was no evidence of a relationship between frailty burden and remission in either the unadjusted (OR = 0.57 (0.28, 1.18), z = −1.52, P = .13) or adjusted models (OR = 0.65 (0.30, 1.42), z = −1.09, P = .28).

Figure 2.

Change in depressive symptoms over time as a function of frailty burden or specific frailty deficits.

Note. The figure displays the model-based mean HRSD scores with the 95% confidence intervals demarcated at the Baseline, Week 8, Month 6 and Month 12 visits. Figure 2A compares frail (three or more deficits in frailty characteristics) and non-frail/intermediate frail (0-2 deficits in frailty characteristics) subjects, Figure 2B compares those with frailty level weakness with those without, and Figure 2C compares those with frailty level deficits in physical activity levels with those without.

Figure 3.

Response and remission rates at major assessment points as a function of frailty burden and specific frailty deficits.

Note. The figure displays response and remission rates as a function of both frailty burden (those with 3+ frailty deficits vs. those with 0-2 frailty deficits) and specific frailty deficits (those with frailty weakness vs. those without; those with low physical activity levels vs. those without). Response in Figures 3A, B, and C is defined as a 50% reduction in baseline HRSD score. Remission in Figures 3D, E, and F is defined as a HRSD score < 10.

Durability of response/non-response as a function of baseline frailty was examined. Among individuals who responded at 8-weeks (33% of frail, 42% of non/intermediate frail), response rates remained high regardless of baseline frailty burden at both 6- (frail 77% [10/13] vs. non/intermediate 77% [10/13]) and 12-months (frail 64% [7/11] vs. non/intermediate 55% [6/11]). In those who did not respond at 8-weeks (67% of frail, 58% of non/intermediate frail), response rates remained low, particularly in frail individuals at both 6- (frail 12% [2/17] vs. non/intermediate 38% [9/24]) and 12-months (frail 13% [2/15] vs. non/intermediate 16% [3/19]). Given that overall frailty burden led to an attenuated antidepressant medication response, with this diminished response evident after acute treatment and persistent across study follow-up (Figure 2A), we tested whether frail participants were treated with a greater number of antidepressant trials. Number of trials were summarized and divided by the length of time a participant was treated, creating a number of trials per month variable. Using Mann-Whitney U tests, we observed an effect of frailty status on the number of medication trials per month (non/intermediate frail median number of trials per month = 0.17; IQR = [0.08, 0.38], compared with frail median number of trials per month = 0.33 IQR = [0.17, 0.50]; Mann-Whitney U = 913.5, P = .018), such that frail adults were treated with more antidepressant medication trials per month than non/intermediate frail adults.

ANTIDEPRESSANT MEDICATION RESPONSE AS A FUNCTION OF INDIVIDUAL FRAILTY DEFICITS

In the individual frailty deficit models, weak grip strength and low physical activity levels were associated with worse response to antidepressant medications, while slow gait speed, exhaustion, and significant weight loss were not. Participants with weaker grip strength have an average HRSD score 2.96 points higher at 8-weeks of treatment, with this difference persisting over the entire follow-up period compared with those with stronger grip strength, ([0.46, 5.46], t = 2.35, df 104, P = .021; Figure 2B). This corresponds to Cohen’s d values of 0.38, 0.39, and 0.39 at 8-weeks, 6-months, and 12-months respectively. Similarly, participants with physical activity levels below the CDC recommended 1000 kcal per week had an average HRSD score 3.28 points higher than highly physically active participants after 8-weeks of treatment, with this difference persisting over the entire follow-up period ([0.67, 5.87], t = 2.51, df 94, P = .014; Figure 2C). This corresponds to Cohen’s d values of 0.43, 0.46, and 0.44 at 8-weeks, 6-months, and 12-months respectively.

In examining the associations between response rates and individual frailty characteristics, both weak grip strength (OR = 0.49 (0.25, 0.96), z = −2.09, P = .04; Figure 3B) and low physical activity levels (OR = 0.41 (0.21,0.81), z = −.57, P = .01; Figure 3C) were associated with significantly decreased response rates to antidepressant medication in the unadjusted models, with the effect of lower physically activity levels on response rates remaining after adjusting for covariates (OR = 0.41 [0.20, 0.81], z = −2.56, P = .01). A similar pattern was observed for remission rates in which weaker grip strength (OR = 0.48 (0.24, 0.94), z = −2.15, P = .03; Figure 3E) and low physical activity levels (OR = 0.47 (0.24, 0.94), z = −2.15, P = .03; Figure 3F) were both associated with decreased remission rates over the follow-up period in the unadjusted models, with these effects maintained in the adjusted models (ORgrip = 0.51 (0.26, 0.97), z = −2.05, P = .04; ORactivity = 0.45 (0.21, 0.93), z = −2.15, P = .03).

CHANGE IN DISABILITY AS A FUNCTION OF FRAILTY

Frailty was associated with a 19.69-point greater impairment in WHODAS 2.0 scores over the 12-month trial of antidepressant medications, such that frail individuals reported significantly greater disability throughout the study compared with non/intermediate frail participants. Similarly, in testing individual frailty characteristics, each of the five frailty characteristics was associated with greater disability throughout the 12-month study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Covariate adjusted longitudinal mixed effects models testing the association between baseline frailty and changes in disability over the 12-month study.

| WHODAS 2.0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Individual Models | Estimate | SE | t-statistic (df) | p-value |

| Total frailty burden | 19.68 | 3.70 | 5.32 (68) | < .001 |

| Grip Strength | 10.91 | 4.00 | 2.73 (85) | .008 |

| Gait speed | 14.98 | 3.95 | 3.80 (83) | < .001 |

| Physical activity levels | 9.48 | 4.33 | 2.19 (76) | .032 |

| Fatigue | 13.85 | 4.63 | 2.99 (86) | .004 |

| Weight loss | 8.70 | 4.32 | 2.02 (88) | .047 |

Note. All models adjusted for age, sex, education and number of medical comorbidities, randomization arm, baseline HRSD, and visit. Models are mixed effects models with covariates (one predictor). Values in the table show the average difference in WHODAS2.0 scores by baseline frailty status (comparing either those who are frail with those who are non-frail/intermediate frail at baseline, or comparing those with the specific frailty characteristic [such as slow gait]. Abbreviations: WHODAS 2.0, Total score on the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale 2.0; HRSD, Total score on the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; Total frailty burden, comparing those with 3 or more characteristics (Frail) to those with 0-2 characteristics (non-frail/Intermediate frail).

DISCUSSION

The intersection between frailty and depression results in increased morbidity and mortality in older adults.10–12,23,24 What remains unknown, however, is whether frailty in the context of LLD is associated with differing treatment trajectories. To address these knowledge gaps, we examined whether frailty burden and specific frailty deficits are associated with differential response to antidepressant medications in adults with LLD. We observed that frail individuals (those with ≥ three frailty deficits) had an attenuated response to antidepressant medications. This attenuated response was evident after an acute 8-week trial and persisted across 10-months of continuation treatment, with nonresponse at 8-weeks associated with non-response at 6- and 12-months in frail elders. The difference in response by frailty status was not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful as well, achieving both a medium effect size difference by frailty status and the three-point difference in HRSD scores used to determine clinical significance in depression treatment trials. Frail elders are also treated with a greater number of antidepressant medication trials compared with non-frail or intermediate-frail individuals. Finally, frail adults with LLD report greater levels of disability throughout the study, with no observed improvement in disability noted despite as much as 12-months of antidepressant medication treatment.

These findings are significant for a number of reasons. Physical characteristics that are not commonly assessed by psychiatrists (strength, physical activity levels, mobility) were associated with poorer treatment outcomes to antidepressant medications and greater depression severity. Clinically, these findings highlight the need for a comprehensive frailty assessment to permit more accurate treatment planning and inform clinicians about long-term patient trajectories. This can be accomplished in less than 10 minutes and requires minimal extra measurement tools, with a dynamometer to assess grip strength the most elaborate device required for adequate assessment. If a dynamometer is too cumbersome, using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) as an alternative will identify older adults with lower extremity musculature difficulties without the need for specific assessment tools. Additionally, wrist-based actigraphy devices can provide accurate measurements of an individual’s physical activity levels that are easily monitored by clinicians prior to and following treatment implementation. These additional procedures exemplify how assessments in clinical psychiatry must be aging-informed: the comprehensive evaluation of a 72 year-old is different from that of a 32 year-old.

Moreover, clinicians should understand that the prognosis is more guarded when treating an individual with comorbid frailty and depression. Frail-depressed older adults will likely experience less symptom improvement, require more antidepressant medication trials, and be left with more disability compared to depressed older adults without frailty. Educating patients and their families on potential clinical trajectories and treatment options may be necessary. Frailty in the context of LLD may mean that antidepressant medications are necessary but not sufficient for the adequate treatment of frail adults with LLD. For example, the presence of frailty deficits25 may prompt a physical therapy consultation, implementation of behavioral activation strategies, or an exercise intervention to improve energy, lower extremity strength, and greater overall activity levels.

As research on the frail-depressed subtype of LLD progresses, identification of specific pathologic mechanisms may facilitate the implementation of precision medicine strategies to improve long-term outcomes. Decreased mitochondrial function,26 for example, is associated with reduced activity levels, diminished strength and muscle mass, slowed mobility27 and greater fatigability in later life.28 Greater mitochondrial dysfunction has also been observed in depressed adults and predicts onset of LLD.29–31 Aerobic exercise interventions targeting sedentary or frail elders improve muscle oxidative capacity and skeletal muscle mitochondrial content22,23,30–32 and increase physical functioning.32,33 Additionally, dopaminergic dysfunction plays a particularly important role in motor slowing. Striatal dopamine levels decrease with age,34 and are associated with slow gait in adults with depression.35 Targeting dopaminergic availability in adults with LLD and slowed motor speed with carbidopa/levodopa results in increased motor speed and decreased depressive symptoms after only three-weeks of treatment.35 Finally, inflammation also increases with age and is associated with increased frailty and specific frailty deficits in both human36 and animal models.37,38 Inflammation is more prevalent in adults with major depressive disorders and incurs increased treatment resistance to some antidepressant medications.39 Studies are ongoing targeting depression with inflammation with anti-inflammatory medications that may benefit individuals with depression who report higher prevalence of frailty-like symptoms of fatigue, slow processing and motor speed, and diminished activity levels.40

There are important limitations to this study. Those with acute or unstable medical illnesses as well as comorbid illnesses such as substance use disorders were excluded, which may impact the generalizability of the study findings to the overall population of frail older adults. Similarly, CAAM is an outpatient clinic and therefore individuals who are unable to travel to such a clinic (individuals in assisted living or nursing homes) may have been excluded. Also, as noted in Figure 1, the dropout rate may appear high in this study. That is misleading, however, as individuals initially consented to an 8-week trial, and thus had the option of completing treatment following the 8-week acute trial. Of the initial 100, 29 participants availed themselves of that option. These 29, although older, did not differ from those who continued in any other meaningful way including frailty burden, baseline depression severity, or 8-week treatment response. Additionally, of the 71 who chose to continue in treatment past 8-weeks, 60 completed all 12-months of treatment, resulting in a retention rate of 85%, quite high given the length of study and patient population. The limitations are offset by specific strengths including the recruitment of a large sample of older adults both classified as frail and diagnosed with MDE or PDD using gold standard measures.16 As such, this study is the first study to comprehensively measure both depression and frailty serially in a relatively controlled treatment study.

In conclusion, findings from this study showed that adults with LLD and frailty, including deficits in strength and physical activity levels, have an attenuated response to antidepressant medication and a greater degree of disability compared with non-frail or intermediate frail individuals. This disability and attenuated antidepressant response remain despite frail elders receiving a greater number of antidepressant medication trials over the course of the study. These findings highlight the importance of comprehensively assessing adults with LLD beyond the standard of psychiatric diagnosis and symptom severity ratings. Physical characteristics such as activity levels, strength, and mobility can provide important insight into the clinical trajectories of the patient, the identification of potential barriers to treatment implementation and may impact therapeutic decision making. Furthermore, future research must focus on understanding whether frailty and specific manifestations of the frail-depressed phenotype represent specific pathophysiological non-normative aging processes, and if so, design and test interventions to target these processes and alter the deleterious clinical course associated with frail adults with LLD.

Supplementary Material

- What is the primary question addressed in this study?

- Adults with late life depression are worse than non-depressed older adults on all five characteristics of the biological syndrome of frailty: They display lower physical activity levels, a greater prevalence of fatigue and significant weight loss, slower gait speeds and weaker grip strength. Frailty in adults with late life depression results in increased mortality risk. Whether frailty burden predicts who will or will not respond to antidepressant medication, however, remains unknown. As such, the primary focus of this study was to investigate the relationship between frailty and treatment response to antidepressant medications in adults with late life depression.

- What is the main finding of this study?

- The main findings from this study are that greater frailty burden and specific characteristics including weak grip strength and low physical activity levels are associated with an attenuated response to antidepressant medications and a greater degree of disability compared with non-frail adults with LLD, even after receiving a greater number of antidepressant medications.

- What is the meaning of the finding?

- This study provides evidence that frailty may identify a high-risk subgroup of late life depression defined by lower antidepressant response to medication treatments, greater disability, and higher mortality risk. Future research must focus on understanding the specific pathophysiology associated with the frail-depressed phenotype to permit the design and implementation of precision medicine interventions for this high-risk population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH099097, K01 MH113850, and R01 MH102293). No Disclosures to Report.

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH099097, K01 MH113850, and R01 MH102293). Drs. Brown, Roose, Ciarleglio, and Rutherford, as well as Ms. Montes, Chung, Alvarez, Stein, and Gomez have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Meeks TW, Vahia IV, Lavretsky H, Kulkarni G, Jeste DV. A tune in “a minor” can “b major”: a review of epidemiology, illness course, and public health implications of subthreshold depression in older adults. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1-3):126–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchalter ELF, Oughli HA, Lenze EJ, et al. Predicting Remission in Late-Life Major Depression: A Clinical Algorithm Based Upon Past Treatment History. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sneed JR, Culang ME, Keilp JG, Rutherford BR, Devanand DP, Roose SP. Antidepressant medication and executive dysfunction: a deleterious interaction in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):128–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng Y, McQuoid DR, Potter GG, et al. Predictors of recurrence in remitted late-life depression. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(7):658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rush AJ, Warden D, Wisniewski SR, et al. STAR*D: revising conventional wisdom. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(8):627–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford BR, Taylor WD, Brown PJ, Sneed JR, Roose SP. Biological Aging and the Future of Geriatric Psychiatry. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(3):343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuthbert BN. Research Domain Criteria: toward future psychiatric nosologies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(1):89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):732–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown PJ, Roose SP, Zhang J, et al. Inflammation, Depression, and Slow Gait: A High Mortality Phenotype in Later Life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown PJ, Roose SP, Fieo R, et al. Frailty and depression in older adults: a high-risk clinical population. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(11):1083–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown PJ, Roose SP, O’Boyle KR, et al. Frailty and Its Correlates in Adults With Late Life Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(2):145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown PJ, Rutherford BR, Yaffe K, et al. The Depressed Frail Phenotype: The Clinical Manifestation of Increased Biological Aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(11):1084–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton M Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1967;6:278–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305(1):50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sousa RM, Dewey ME, Acosta D, et al. Measuring disability across cultures--the psychometric properties of the WHODAS II in older people from seven low- and middle-income countries. The 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, Third Edition. Wiley; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedeker D, du Toit SHC, Demirtas H, Gibbons RD. A note on marginalization of regression parameters from mixed models of binary outcomes. Biometrics. 2018;74(1):354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing.. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizopoulos D GLMMadaptive: Generalized Linear Mixed Models using Adaptive Gaussian Quadrature. R package version 0.6-8. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz IR. Depression and frailty: the need for multidisciplinary research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soysal P, Veronese N, Thompson T, et al. Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;36:78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyrrell DJ, Bharadwaj MS, Van Horn CG, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Molina AJ. Respirometric Profiling of Muscle Mitochondria and Blood Cells Are Associated With Differences in Gait Speed Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1394–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coen PM, Jubrias SA, Distefano G, et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics are associated with maximal aerobic capacity and walking speed in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(4):447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santanasto AJ, Glynn NW, Jubrias SA, et al. Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Function and Fatigability in Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown PJ, Brennan N, Ciarleglio A, et al. Declining Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Function Associated With Increased Risk of Depression in Later Life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(9):963–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karabatsiakis A, Bock C, Salinas-Manrique J, et al. Mitochondrial respiration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlates with depressive subsymptoms and severity of major depression. Translational psychiatry. 2014;4:e397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris G, Berk M. The many roads to mitochondrial dysfunction in neuroimmune and neuropsychiatric disorders. BMC medicine. 2015;13:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broskey NT, Greggio C, Boss A, et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondria in the elderly: effects of physical fitness and exercise training. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(5):1852–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pahor M, Blair SN, Espeland M, et al. Effects of a physical activity intervention on measures of physical performance: Results of the lifestyle interventions and independence for Elders Pilot (LIFE-P) study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(11):1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haycock JW, Becker L, Ang L, Furukawa Y, Hornykiewicz O, Kish SJ. Marked disparity between age-related changes in dopamine and other presynaptic dopaminergic markers in human striatum. J Neurochem. 2003;87(3):574–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutherford BR, Slifstein M, Chen C, et al. Effects of L-DOPA Monotherapy on Psychomotor Speed and [(11)C]Raclopride Binding in High-Risk Older Adults With Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;86(3):221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Walston JD, Matteini AM, Nievergelt C, et al. Inflammation and stress-related candidate genes, plasma interleukin-6 levels, and longevity in older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44(5):350–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128(1):92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visser M, Pahor M, Taaffe DR, et al. Relationship of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with muscle mass and muscle strength in elderly men and women: the Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(5):M326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raison CL, Rutherford RE, Woolwine BJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: the role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(1):31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fourrier C, Sampson E, Mills NT, Baune BT. Anti-inflammatory treatment of depression: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial of vortioxetine augmented with celecoxib or placebo. Trials. 2018;19(1):447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.