Abstract

Introduction

Spiritual care has a positive influence when patients are subjected to serious illnesses, and critically ill situations such as the case of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions and attitudes of nurses working at critical care units and emergency services in Spain concerning the spiritual care providing to patients and families during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A qualitative investigation was carried out using in-depth interviews with 19 ICU nursing professionals.

Findings

During the pandemic, nurses provided spiritual care for their patients. Although they believed that spirituality was important to help patients to cope with the disease, they do not had a consensual definition of spirituality. Work overload, insufficient time and lack of training were perceived as barriers for providing spiritual healthcare.

Discussion

These results support the role of spirituality in moments of crisis and should be considered by health professionals working in critical care settings.

Keywords: Critical care, COVID-19, Emergency, Health professionals, Qualitative research, Spiritual care, Spirituality

Introduction

Although there is no consensus, spirituality is usually considered the “dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant, and/or the sacred” (Nolan, Saltmarsh, & Leget, 2011; p.88). This dimension is different and a broader concept as compared to the term “religion”, which involves “beliefs, practices, and rituals related to the transcendent” (Koenig, 2012; p.2).

In the last decades, there has been a remarkable increase in this field of knowledge (Lucchetti & Lucchetti, 2014) and the current evidence shows that spiritual well-being plays a fundamental role in both physical and mental health (Heidari, Karimollahi, & Mehrnoush, 2016), providing peace and harmony that can lead to healthier lifestyles (Azarsa, Davoodi, Khorami Markani, Gahramanian, & Vargaeei, 2015). Likewise, these beliefs seem to have an important influence on the decision-making of patients and their families (Nascimento et al., 2016).

In this context, spiritual care (i.e. meeting the spiritual needs of patients and family) is especially important in intensive care units (ICUs) and emergency services, where the complexity and severity of the diseases and the critically ill situations of patients create an environment of unexpected changes that causes loss of hope, anxiety, fear and stress (Abu-El-Noor, 2016; Azarsa et al., 2015; Pierce, Hoffer, Marcinkowski, Manfredi & Pourmand, 2020). Some studies have already confirmed the importance of spiritual care in these settings, showing an improvement in stress, self-esteem and depression, a decrease in hospitalization time, and a reduction in healthcare costs (Riahi et al., 2018; Abu-El-Noor, 2016).

However, healthcare professionals seldom include spiritual care in their routine clinical practice. Several reasons are pointed as barriers to include this care such as a lack of understanding of the concept of spirituality, fear of imposing own beliefs or offending patients, preference for biological issues and lack of training (Choi, Curlin & Cox, 2019; Cordero et al., 2018; Gallison, Xu, Jurgens, & Boyle, 2013; Kim, Bauck, Monroe, Mallory & Aslakson, 2017; Koukouli, Lambraki, Sigala, Alevizaki, & Stavropoulou, 2018; Vasconcelos et al., 2020). These barriers result in a late addressing of the spiritual needs, which are commonly limited to the last 24 to 48 hours of the patient's life (Choi et al., 2019).

All these problems seem to be increased during moments of crisis, when time and resources are limited, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 has affected millions of individuals worldwide and Europe has seen a very delicate situation, where the number of deaths and hospitalizations in ICUs were alarming (Shah & Farrow, 2020). In the specific case of Spain, the number of infected people has reached more than 400,000 cases, and more than 28,500 people have died (Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare MHCSW, 2020). Regarding ICU hospitalizations, the figures have exceeded 12,000 cases. Currently, nurses are constantly subjected to the stress of critically ill patients, something that has intensified even more during this pandemic (Gabriel & Webb, 2013). In addition, although the family is one of the main pillars for providing spiritual care, family visits have been limited in all healthcare units due to restrictions.

Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients needed to overcome the feeling of isolation in different ways. Among several coping strategies, spiritual and religious beliefs were important to these patients as noted by some studies (Lucchetti et al, 2020). However, the support of religious services and religious leaders during the pandemic were not fully available (Kowalczyk, et al., 2020; Roman, Mthembu & Roman, 2020). Some hospitals tried provide technological means for communication between patients and their families (video calls or telephone conversations), in an attempt to alleviate the lack of spiritual support from their loved ones (Andrews & Benken, 2020).

Although the number of publications has drastically increased during the pandemic, most of the studies have focused on the treatment, care planning and epidemiology of COVID-19 disease (Del Castillo, 2020; Dawood et al., 2020). In this context, more studies are needed to understand the qualitative experiences of critical care health professionals towards spiritual care and, to our knowledge, no study has investigated this aspect in Spain, one of the most affected countries.

In order to bridge this gap, this study aims to investigate the perceptions, knowledge and attitudes of nurses working at critical care units (ICUs) and emergency services in Spain concerning the spiritual needs of patients and families and the spiritual care provided during their clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Design

A qualitative, exploratory and descriptive design study using an ethnographic-phenomenological approach has been carried out. This approach is characterized by (a) a conceptual orientation provided by a researcher team; (b) a focus on a discrete community; (c) a focus on a problem within a specific context; (d) a limited number of participants; (e) the use of participants who may hold specific knowledge; and (f) the use of selected episodes of participant observation (Muecke, 1994). Data collection consisted of in-depth interviews conducted by a qualified investigator from January to June 2020 (6 months of data collection).

Sample and Setting

Participants were included provided they were nursing professionals working at intensive care units (ICUs) or emergency services from public or private hospitals in Spain and treating critically ill patients with COVID-19. Religious personnel from hospital centers, health professionals who were working outside ICUs or emergency services, as well as those not caring for patients (e.g. academic or management level) were excluded.

Data Collection

A WhatsApp blast including a poster describing the study was distributed widely using researchers’ professional and personal contacts. In order to increase the number of participants, a snowball sampling procedure was used, aiming to have a diverse range of ages and experiences (Higginbottom, 2004). Interested participants contacted the researchers ( Reviewer 1, Reviewer 4 ) directly and eligibility criteria were applied. Eligible participants were invited by the main researcher ( Reviewer 1 ), who is a nurse and anthropologist with expertise in spiritual care and that has published several articles in the field of “Spirituality and Health”.

Since Spain was facing the implementation of a “State of Emergency” during this period, no face-to-face meetings with health professionals were allowed. Therefore, interviews occurred at a time of convenience to the participant, using telephone calls, e-mail or other web meetings. The interviews were carried out by one researcher ( Reviewer 2 ) in the Spanish language, lasted approximately 50 to 60 minutes and were audiotaped by the main researcher, transcribed verbatim by two researchers ( Reviewer1, Reviewer 2 ), and then, translated into English by a translation company. Data collection continued until data saturation was reached (Urra, Muñoz, & Peña, 2013).

In addition, as part of the interviews, participants were asked to send images captured by them during the COVID-19 pandemic. These images were important to corroborate participants’ statements and to show their experiences with spirituality and spiritual care. In the last decades, there is a trend of interest in using qualitative techniques such as photovoice, as a research method in healthcare research in order to fully examine the studied context (Oosterbroek, Yonge, & Myrick, 2020). The participants were oriented to produce photographs and they were asked to report what each photo represented to them. The researcher team analyzed these images, which were incorporated into the analysis.

Instrument

An interview script was used. An expert panel using the Delphi method (Boulkedid, Abdoul, Loustau, Sibony, & Alberti, 2011) carried out an analysis of the script's content between January and February 2020. The contact and contributions to assess this initial script were made online in two rounds, where 17 experts in spiritual health and/or critical care were invited to participate via email, of which 10 agreed to participate. The characteristics of the experts’ panel are shown as a Supplementary material (Table A1).

The interview script was based on previous quantitative instruments and on the experience of the members of the Delphi panel (e.g. spirituality and its interface with COVID-19). These instruments were adapted and used as open-questions in a qualitative way. The following instruments served as a theoretical framework to the development of the interview:

-

–

Sociodemographic characteristics: gender, age, ethnicity, religion and year of undergraduate nursing training;

-

–

Religiosity: using the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) (Koenig, Parkerson, & Meador, 1997), which is an instrument with five questions concerning the religious aspects of a person, including organizational religiosity (religious attendance), non-organizational religiosity (private religious practices) and intrinsic religiosity (religion as an important part of life).

-

–

Attitudes and opinions about spirituality and health: using the Curlin's instrument, “Religion and Spirituality in Medicine, Perspectives of Physicians—RSMPP” (Curlin, Lawrence, Chin, & Lantos, 2007). This instrument has two sections: (a) The first section deals with religion, spirituality and clinical practice (spirituality's influence on health, attitudes and barriers to address these questions with patients and the influence of these on the professional–patient relationship), (b) The second section evaluates professional’ opinions about academic training and teaching.

-

–

Questions related to the clinical care during COVID 19 pandemic: developed during the Delphi panel, it includes the influence of spiritual and religious beliefs on COVID patients, the challenges of providing spiritual care during the pandemic and the coping strategies these professionals use.

The complete interview is available as a Supplementary material (Table B1).

Data analysis

Transcription, literal reading, and theoretical manual categorization were performed, and MAXQDA software was used. Data analysis started with individual readings and looking at the photos to get an overview of respondents’ experiences. Two researchers read all interview transcriptions and looked at the photos several times, to gain an overall understanding of the content. The analysis continued by organizing descriptive labels, focusing on emerging or persistent concepts and similarities/differences in participants’ behaviors, statements and pictures. The coded data from each participant were examined and compared with the data from all the other participants to develop categories of meanings. Finally, the analysis and treatment of qualitative data MAXQDA was used and a final report was developed (Braun, Clarke, Hayfield, & Terry, 2019), with the statements of the participants (P- participant number, sex, age).

Trustworthy

This research followed the criteria of The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007) (See the Supplementary material – Table C1). The methods used for guaranteeing quality were data triangulation, including participants with different sociodemographic characteristics, and triangulation of data analysis via different researchers.

Ethical considerations

The study received approval from the [BLINDED FOR PEER REVIEW]. Participants were invited through the main researcher to participate voluntarily, so they were incorporated into the study after accepting and signing the informed consent sent by email.

Findings

Description of Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 19 nursing professionals working at Spanish ICU and emergency services, being 78.9% women with a mean age of 30.0 (SD:8.9) years old (ranging from 22 to 52 years). In the total sample, six participants sent a photograph that symbolized some aspect of spiritual or religious care during the pandemic. Most participants work in emergency departments (57.9%), in public health institutions (78.9%) and the most common cities were in Barcelona (47.3%), Madrid (15.8%), and Seville (36.9%). Regarding their spiritual and religious beliefs, 47.3% had no religious affiliation and did not believe in God and 42.1% were Catholics. Only 36.9% of the sample defined themselves as spiritual and religious beings. The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

| Variables | Participants (n = 19) |

|---|---|

| Gender | n(%) |

| Woman | 15 (78.9) |

| Man | 4 (21.1) |

| Age (years) M(SD) | 30 (8.09) |

| Ethnicity | |

| European (white) | 18 (94.7) |

| Asian | 1 (5.3) |

| Incomes | |

| 500-1,499€ | 2 (10.5) |

| 1,500-2,999€ | 13 (68.4) |

| 3,000-4,999€ | 3 (15.8) |

| ≥ 5,000€ | 1 (5.3) |

| City of residence and work | |

| Barcelona | 9 (47.3) |

| Madrid | 3 (15.8) |

| Seville | 7 (36.9) |

| Hospital service | |

| Intensive Critical Unit (ICU) | 8 (42.1) |

| Emergency services | 11 (57.9) |

| Type of hospital according to financing | |

| Public | 15 (78.9) |

| Private | 1 (5.3) |

| Mixed | 3 (15.8) |

| Religious affiliation | |

| None and I don't believe in God | 9 (47.3) |

| Catholic | 8 (42.1) |

| Buddhist | 1 (5.3) |

| Belief in energies | 1 (5.3) |

| Do you consider yourself a spiritual / religious person? | |

| Spiritual and Religious | 7 (36.9) |

| Spiritual, but not Religious | 1 (5.3) |

| Religious, but not Spiritual | 2 (10.5) |

| Neither Spiritual nor Religious | 9 (47.3) |

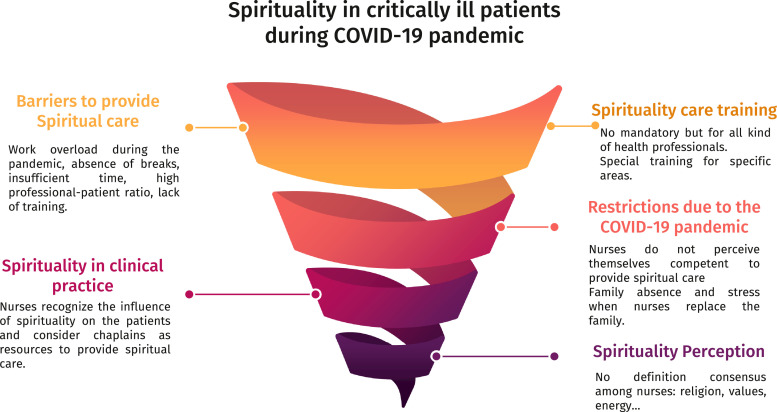

The analysis yielded five main themes which reflect all of the categories: “The definition of Spirituality”, “Addressing spirituality in clinical practice and its influence on health”, “Spiritual care during the COVID pandemic”, “Barriers to provide Spiritual Care and possibilities for improvement”, and “Spiritual care training for health professionals”. These themes are described below.

Theme 1: The definition of Spirituality

It was clear that there was no consensus on the definition of spirituality by nurses. In fact, spirituality was related to a series of different factors such as: meaning and searching for answers, religious beliefs; the essence of really fundamental things, such as love, family, friends; and the exchange of energy between people. Some participants also have acknowledge the differences between spirituality and religion, describing that they have beliefs but were not religious persons.

“I like to think about the meaning of things, searching for answers that cannot be explained in a scientific way” (P-2, man, 32 years); “I consider myself spiritual and integrate it into my life to relieve stress. For example, I do meditation and it helps me relax, something essential in these hard times” [referred to COVID-19 pandemic] (P-7, woman, 22 years); “I am not a member of any religion, but I have beliefs and values of my own” (P-9, woman, 23 years).

Theme 2: Addressing spirituality in clinical practice and its influence on health

Nurses used the words faith, support, or beliefs to explain the term spirituality. Most participants (n = 17) agreed that there was a positive and direct relationship between patient's spirituality and health, that spirituality may help in coping with a disease and that could improve the nurse-patient relationship. Some nurses shared their experiences as shown below:

“Some patients have coped better with their illness by clinging to God through prayers, images, and promises”; (P-1, woman, 25 years) “I think it influences both the patient's attitude and the nurse-patient relationship. I have dealt with patients who have accepted their treatments better thanks to their beliefs and with other ones who have rejected them due to the same reason” (P-5, woman, 25 years).

Although two people preferred to talk about emotion management as the way to achieve success in coping with health problems, most participants believe spirituality and/or religiosity help the patient to cope and adapt to a new situation of illness, providing hope, energy, and strength to overcome health problems.

Nurses were aware that the spiritual needs of their patients are an important part of care. However, some nurses believe the care should focus predominantly on biological dimensions, especially in high technology and stressful environments such as the ICU and the emergency services: “In critical and emergency situations, I think the issue spiritual care should be left aside since we must prioritize serious care” (P-13, woman, 29 year). Likewise, some participants considered that other professionals have more competencies to carry out this spiritual approach: “As in hospitals there are Catholic chaplains, we let them provide that care. We, in the emergency room or in the ICU, respond quickly to the physiological state of people, that is the priority” (P-10, woman, 33 years).

Nurses also emphasized that healthcare professionals need to respect every aspect that may positively influence patients’ health, and this should be done regardless of the religiosity of the healthcare worker: “I consider that Professionals' beliefs should not interfere. I am not a religious believer and I have supported the beliefs of those who were religious because it made them feel better” (P-8, woman, 24 years); “Religious / spiritual patients who practice their faith, carry images and they pray during their illness process ... respecting it is synonymous with professionalism” (P-2, man, 32 years old).

Despite the respect for the spiritual beliefs, most nurses did not address these issues in clinical practice: “By not considering myself a spiritual / faith person, I have never noticed this need in my patients, possibly in an erroneous on my part” (P-4, man, 31 years), and tend to have little experience with the spiritual issues: “I have not had experience on spiritual care. Once, they [patients] have asked us for the chaplain to come so they can speak, confess or ask for extreme unction. Other than that, nothing” (P-2, man, 32 years).

Theme 3: Spiritual care during the COVID pandemic

COVID-19 pandemic was a special moment in which, according to the participants, emotions and spirituality are necessary as a support for the patient: “A woman began to pray when the doctors confirmed the diagnosis of COVID-19 positive and it did not seem strange to us. I remained silent as a sign of respect and support for her” (P-17, man, 25 years). Likewise, they understand spirituality as a moral support to those who suffer the most, in many cases, the relatives of the most serious patients: “More than to the patient, the support is often offered to families when we have had to prepare them for the loss of a loved one, when we can only limit ourselves to comfort and advise them (...), when everything is lost, the only thing we can do is pray because it will make us feel better” (P-11, man, 46 years). In fact, in several occasions, religious and spiritual symbols were given to patients as noted in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

It incorporates two photos of ICU rooms: (a) The daughter of a patient brought a handmade canvas made by the villagers. Since she couldn't be with her father, she asked the nurse to hang it up. The nurse one afternoon hung it in the place where the patient could see it and he told her about "his Virgin”; (b) A nurse found an image of the Virgin next to a patient's respirator, understanding it as a symbol of protection that the patient and her family trusted.

Nursing professionals were responsible for providing psychological and spiritual support to patients during the pandemic, since family visits were not allowed and religious leaders were not fully available. However, some participants reported that they did not have the appropriate training to handle this situation: “I think that no one was prepared for this situation. Some patients have faced it by taking refuge in their religion or spirituality, and others have needed psychological attention, but I do not know if everyone has had this help. Sometimes the family has that function, but it has not been possible on this occasion, so we do what we can” (P-7, woman, 22 years).

Although some professionals acknowledged that religious beliefs influenced the acceptance of the prognosis of COVID-19 by patients: “I believe that patient's religious beliefs have been useful in coping with the disease and the uncertainty of its evolution, and move forward with more force” (P-7, woman, 22 years), other participants considered that the only factors relevant to the prognosis of this condition were the immune status of the patients and a good ventilatory support, supporting that the biomedical science is the only appropriate method for caring their patients.

Although spirituality was not important to most of our participants, they tended to agree that their work was characterized by empathy, compassion, solidarity, patience, resilience, and companionship: “Few colleagues express their religious thoughts to patients” (P-2, man, 32 years); “I have seen many aspects of professional resilience in many moments, psychological messages of support and encouragement, but I have not seen professionals attending to the spirituality of patients or of themselves” (P-9, woman, 23 years). On the other hand, some nurses have tried to cope with the stressful situation and the suffering of patients and relatives through mental disconnection (e.g. yoga or relaxation techniques) and by religious practices (e.g. prayer). This has been expressed through Figure 2 .

Figure 2.

A nurse and an emergency technician enter a Catholic church. They work for 12 hours, providing home care, where people affected by COVID-19 remain alone, sad and desperate. When they get a break or finish their workday, they remain silent with their thoughts and with God in this church, seeking answers and hope to overcome the pandemic.

Theme 4: Barriers to provide Spiritual Care and possibilities for improvement

During the interviews, most of the nurses (n = 15) reported the barriers and reflected on the possibility of improving spiritual care in critical and emergency care units. The most common barriers cited were, work overload during the pandemic (e.g. absence of breaks), insufficient time, a high professional-patient ratio and the lack of training.

Other difficulties were not feeling prepared to answer “transcendental” or personal questions, the lack of social and professional recognition of spiritual care, difficulty in identifying the presence of religious symbols that accompany the patient and restrictions on family visits to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus: “I believe that it is one of the greatest handicaps of this pandemic since the accompaniment of family members is very comforting to both; and the restriction of visits generates anguish and uncertainty; although we must understand that it is the best for everyone” (P-8, woman, 24 years) and the patient's critical condition: “In ICUs we have worked with patients who are totally sedated and when we have been able to extubate him/her, we have provided him/her mainly moral support” (P-11, man, 46 years).

Some participants have also underscored the differences of beliefs as an important barrier in order to provide a more integrative care: “It can be difficult for a religious professional to understand a patient with different beliefs and vice versa” (P-6, woman, 22 years); “My religious or spiritual beliefs influence, in my case, I declare myself an atheist and I think that a religious belief that indoctrinates a person can lead him/her to reject a treatment that would probably save his/her life ...” (P-9, woman, 23 years). However, sharing beliefs could bring the patient closer to the nurse as noted by one participant: “From my experience, if a patient and the health worker are religious, the relationship is more open to talk about it” (P-7, woman, 22 years).

Despite these remarkable barriers, in order to promote a better spiritual care, professionals reported that they need a silent moment without interruptions in order to provide such care: “It would be necessary to mark a moment where there is no interruption so that there is connection between patient and nurse and build trust” (P-5, woman, 25 years), better guidelines and protocols for the inclusion of spiritual care in these settings: “Setting objectives for nurses and doctors regarding care psychological and spiritual, interviewing the patient, using quality scales” (P-9, woman, 23 years), appropriate spaces for contemplative practices: “From spaces for meditation, yoga to others where religious practices of any kind are carried out” (P-5, woman, 25 years), improving training on spiritual care, the creation of support groups, the incorporation of specialized personnel (chaplain, priest or priest) of different religions in the ICU or emergency services and a coordinated work with them within the interdisciplinary team.

Theme 5: Spiritual care training for health professionals

“We must be prepared to provide spiritual care” is a common statement shared by nurses, being the increase in cultural diversity in large Spanish cities the main reason: “It is necessary [having competencies to provide spiritual care] because we are dealing with patients with a multitude of beliefs and we are not being able to take care of the patient in that regard” (P-11, man, 46 years).

However, most of the participants state that they have not received any training concerning spirituality (n = 17) and did not feel prepared to provide this care (n = 15). Therefore, nurses consider that training in spirituality should be offered to professionals from any health discipline (n = 14): “In Barcelona it is important because there are many people from other countries, with different religious beliefs and spirituality. If the healthcare professional is not trained, the patient will not trust you” (P-9, woman, 23 years).

While some nurses only associate training in spiritual health with the acquisition of competencies to care for patients in near-death situations: “I miss the university training in spiritual care for situations of grief or coping with a serious illness” (P-15, woman, 26 years), others believe this issue is personal and training should not be addressed as mandatory: “Classes on spiritual care should be optional, since religion and spirituality are very personal things and diverse, and it can hurt sensibilities” (P-2, man, 32 years); “I do not think this type of training is adequate, at least not in a scientific career like nursing” (P-16, woman, 31 years) Figure 3 .

Figure 3.

Graphic summary of the reults.

Discussion

This study showed that, during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain, nurses were responsible for providing spiritual care for their patients. Although they generally believe that spirituality is important to treatment and help patients to cope with the disease, they do not have a consensual definition of spirituality and were not trained to handle this care. Several barriers are cited as limitations of the spiritual care such as the work overload, insufficient time and lack of training.

The diversity of our findings stems from the terminological confusion about spirituality itself (Nascimento et al., 2016). Although the World Health Organization proposed the spiritual aspect as a component of health in 1983 (WHO, 1998), there is still no universal and clear definition of spirituality (Canfield et al., 2016). This explains why some nurses use spirituality and religiosity as synonyms, or even erroneously exclude spirituality as part of religiosity (Sonemanghkara, Rozo, & Stutsman, 2019). Also coinciding with our study, nurses also include compassion and empathy as related to spirituality, as shown in a previous study investigating Thai ICU nurses (Lundberg & Kerdonfag, 2010).

Although the nurses in our study perceive the influence of Spirituality and/or Religiosity (S/R) on patient's health and on the way they cope with the disease, there is a clear confusion concerning the role that nurses should play towards spiritual care. One of the reasons for this confusion is the presence of religious personnel such as chaplains, who are considered the professionals with greater competence for spiritual care and, in the perception of the family, are the most important figures to address spiritual beliefs in critically ill patients (Gallison et al., 2013).

In the same direction, most of the spiritual care is provided by the family as seen in previous studies. Previous authors have reported that family accompaniment is “something spiritual”, helping patients to seek meaning and protection from God in order to cope with tragedies (Chávez-Correa, 2014). In this context, nurses are responsible for making this connection between family and the patient and providing a safer and comfortable environment (Nascimento et al., 2016). However, the restrictions on family visits during the pandemic, increased the tension between nurses, since, although they professionally respect the spiritual needs of their patients, they fear facing them alone and without training (Kowalczyk et al., 2020).

In Spain, some institutions have made efforts to incorporate the spiritual and religious approaches in health care. Taking as a framework the Spanish legislation that recognizes the right to religious freedom; spiritual and religious assistance in hospital centers is considered as a right of the patient and the family. The Observatory of Religious Pluralism (OPR, 2011) in Spain, published a guideline for health personnel on recommendations about how to address spiritual and religious assistance in hospitals. However, we observed that the inclusion of the S/R as part of the comprehensive care of critically ill patients is yet uncommon. On the one hand, critical care units and emergencies are characterized by a biomedical care approach (De Brito et al., 2013; Huijer, Bejjani, & Fares, 2019; Ferrell, Handzo, Picchi, Puchalski, & Rosa, 2020). On the other hand, the nurses state that their own beliefs can constitute a handicap to provide spiritual care (Turan & Yavuz Karamanoǧlu, 2013), and other barriers as well. Lack of time, the high patient and/or nurse ratio, the fear of making the patient uncomfortable and the belief that spirituality is something private are also shared by other authors (Gallison et al., 2013).

Finally, the nurses in this study share with other nursing professionals and students the need to improve their competence to provide spiritual care to patients (Cordero et al., 2018; Riahi et al., 2018). According to the International Council of Nurses and the Commission on the Rights of Patients, nurses must have the knowledge and skills to be able to promote and assess the satisfaction of the spiritual needs of their patients (De Brito et al., 2013) and, for this reason, institutions should be able to provide education to these professionals concerning spiritual care. However, the application of the biomedical science to nursing, as well as the consideration that there are professionals with better skills to deliver this care to patients (e.g. chaplains, psychologists) seem to reduce the willingness to provide such care.

Limitations and Strengths

The present study has some limitations that should take into account while interpreting our findings. First, this study was carried out in Spain and it reflects the experiences of health professionals from Spanish health care facilities. It is difficult to guarantee that the same results would be observed in other countries, since the cultural and religious backgrounds are different. Second, we used a purposive sample and generalizability should be made with caution. Third, Spain was one of the most affected countries in the COVID pandemic and, for this reason, nurses were burned out and with work overload, which may have impacted our findings. Finally, since nurses have been one of the largest healthcare forces with patients affected by COVID, feminization has resulted in a higher proportion of women.

Based on this study, we suggest a few directions for future research. Future research should include new care contexts, religious personnel (if this hospital resource exists), as well as other health professionals as members of the health team. In addition, interventions aimed at clarifying terms of S/R would be the first step so that health professionals can internalize them and take it into account as part of holistic care. Multicenter studies and cross-cultural comparisons are suggested between countries, to know the experiences of health professionals (especially nurses) in secular countries or where different religious practices predominate.

Finally, this study showed spiritual needs are commonly expressed during life-threatening situations, such as those experienced in ICUs. Because our results highlight that most nurses are open to this subject, a valuable strategy would be training to handle these situations. Therefore, health managers are commended to organize training for ICU health care professionals in order to provide a more holistic care.

Conclusions

Spirituality was considered an essential dimension of care during the COVID-19 pandemic as observed in the opinions and perceptions of the Spanish nurses included in this study. These results support the role of spirituality in moments of crisis and should be considered by health professionals working in critical care settings. However, the lack of training, insufficient time and work overload are important barriers to this provision of care and should be considered by health managers and healthcare institutions.

Author Contribution

Rocío De Diego-Cordero: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis and interpretation, Software, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Lorena López-Gómez: Investigation, Formal analysis and interpretation, Data curation, Software, Giancarlo Lucchetti: Formal analysis and interpretation, Writing- Original draft preparation, Validation, Visualization, Bárbara Badanta: Conceptualization, Writing-Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Project administration.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Appendix

Table A1.

Characteristics of Experts for Delphi Panel

| Code | Age | Gender | Residence | Highest academic level | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | 40 | Woman | Murcia | PhD | Medical anthropology / Expert in spiritual health, cross-cultural spirituality and mindfulness |

| Expert 2 | 59 | Woman | Seville | PhD | Nurse in ICU/University professor |

| Expert 3 | 63 | Woman | Seville | PhD | Nurse (specialist in paliative care, spirituality and humanization of care) / Anthropologist /Social Worker/ University professor |

| Expert 4 | 57 | Woman | Seville | MRcN | Nurse in Emergency Care/University professor |

| Expert 5 | 43 | Woman | Seville | PhD | Nursing Researcher (specialist in paliative care and humanization of care) /University professor in religious institution |

| Expert 6 | 42 | Woman | Seville | PhD | Nursing Researcher (specialist in spiritual health) /University professor in religious institution |

| Expert 7 | 33 | Woman | Seville | PhD | Nurse in ICU/ Research in spiritual health and transcultural nursing / University professor |

| Expert 8 | 59 | Man | Granada | PhD | Psychologist / Expert in health promotion and spiritual health |

| Expert 9 | 33 | Woman | Seville | MRcN | Nursing Researcher in spiritual health |

| Expert 10 | 41 | Man | Brazil | PhD | Physician Researcher (specialist in spirituality and health) / University professor |

Table B1.

Interview Guide

| What do you consider to be S / R person? What does the S / R imply? Do you consider the S / R in your life? How? Trought, feeling or practice? |

| Have you ever heard the term spiritual health or spiritual care? What ideas do you have or know about spiritual activities or care? |

| Do you think that S / R influences in any way the health of patients, their coping with the disease, or even the professional-patient relationship? If so, how do you think it influence? Do you have any experiences or know some examples? |

| Have you ever discussed S / R with the patients? If you have experience, could you comment on any situation in which you provided spiritual care? Do you feel a desire or need to do so? (If “Yes”, How often? When or in what specific situations?) |

| Do you consider yourself prepared to address S / R issues with your patients? |

| What is your experience and what do you need to face the COVID-19 pandemic? Are there any resources or help to provide spiritual care? Are they being launched or used? |

| What is the role of your spiritual or religious beliefs at this time of crisis due to COVID-19? Have aspects of S / R emerged in yourself, your colleagues, patients or relatives to cope with the situation of COVID-19? |

| What reasons discourage you from addressing S / R with your patients? How do you think it could be done? How do you think spiritual care in hospitals could be improved? |

| Do you think that nursing students should be prepared during their university career to address S / R with patients? |

| Have you ever participated in any training activity on S / R or “Health and Spirituality”? Any example? |

| Is current university education adequate to address S / R beliefs with patients? For which situations do you consider the training most necessary? |

Table C1.

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ): 32-Item Checklist

| No | Item | Guide questions/description | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | |||

| Personal Characteristics | |||

| 1. | Interviewer/facilitator | Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group? | All the interviews were conducted by the one author, LL. |

| 2. | Credentials | What were the researcher's credentials? E.g. PhD, MD | BB, RDC and GL were PhD. LL was a nursing student. |

| 3. | Occupation | What was their occupation at the time of the study? | Researcher's occupations at the time of the study: student and research professor. |

| 4. | Gender | Was the researcher male or female? | BB, RDC and LL were females. GL was male. |

| 5. | Experience and training | What experience or training did the researcher have? | All researchers had experience in carrying out qualitative research. BB has been trained to conduct interviews and RDC has training in social research. LL has been trained to analyze data of qualitative research. |

| Relationship with participants | |||

| 6. | Relationship established | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? | No, there wasn't. |

| 7. | Participant knowledge of the interviewer | What did the participants know about the researcher? e.g. personal goals, reasons for doing the research | Name, occupation, reasons for doing the research. |

| 8. | Interviewer characteristics | What characteristics were reported about the interviewer/facilitator? e.g. Bias, assumptions, reasons and interests in the research topic | Name, occupation, contact method, reasons for doing the research. |

| Domain 2: Study design | |||

| Theoretical framework | |||

| 9. | Methodological orientation and Theory | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? e.g. grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis | Phenomenological and ethnographic approach with a discourse and content analysis. |

| Participant selection | |||

| 10. | Sampling | How were participants selected? e.g. purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball | Purposive and snowball sampling procedure. |

| 11. | Method of approach | How were participants approached? e.g. face-to-face, telephone, mail, email | Interviews occurred at a time of convenience to the participant, using telephone calls, e-mail or other web meetings. |

| 12. | Sample size | How many participants were in the study? | 19 nursing professionals from ICU and emergency services |

| 13. | Non-participation | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? | None |

| Setting | |||

| 14. | Setting of data collection | Where was the data collected? e.g. home, clinic, workplace | The activation of the “State of Emergency” in Spain did not allowed face-to-face meetings with health professionals, nor mobility between cities. Therefore, interviews occurred at a time of convenience to the participant, using telephone calls, e-mail or other web meetings. A quiet and comfortable place was chosen by each participant (home or workplace). |

| 15. | Presence of non- participants | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? | There were other health professionals and family members. |

| 16. | Description of sample | What are the important characteristics of the sample? e.g. demographic data, date | 78.9% were women with a mean age of 30 years. 57.9% participants was working in emergency departments and the most common cities were Barcelona (47.3%), Madrid (15.8%), and Seville (36.9%). |

| Data collection | |||

| 17. | Interview guide | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? | Yes, they were. / Yes, it was. |

| 18. | Repeat interviews | Were repeat inter views carried out? If yes, how many? | No, they weren't. |

| 19. | Audio/visual recording | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? | Audio recording. |

| 20. | Field notes | Were field notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? | No, they weren't. |

| 21. | Duration | What was the duration of the inter views or focus group? | Average 50-60 minutes. |

| 22. | Data saturation | Was data saturation discussed? | Yes, it was. |

| 23. | Transcripts returned | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? | Reviewed by 2 participants. |

| Doman 3: Analysis and findings | |||

| Data analysis | |||

| 24. | Number of data coders | How many data coders coded the data? | Two (LL and RDC). |

| 25. | Description of the coding tree | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? | Yes, we did. |

| 26. | Derivation of themes | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? | Themes were derived using both methods. |

| 27. | Software | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? | MAXQDA |

| 28. | Participant checking | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? | Reviewed by 2 participants |

| Reporting | |||

| 29. | Quotations presented | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? e.g. participant number | Yes, there were. / Yes, there was. |

| 30. | Data and findings consistent | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? | Yes, there was. |

| 31. | Clarity of major themes | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? | Yes, they were. |

| 32. | Clarity of minor themes | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? | Yes, there is. |

Developed from: Tong, A. Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32- ítem checklist for interviews and focus group. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19: 349-357.

References

- Abu-El-Noor N. ICU nurses’ perceptions and practice of spiritual care at the end of life: Implications for policy change. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2016;21(1):1–10. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No01PPT05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews L.J., Benken S.T. COVID-19: ICU delirium management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic—pharmacological considerations. Critical Care. 2020;24(1):375. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03072-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarsa T., Davoodi A., Khorami Markani A., Gahramanian A., Vargaeei A. Spiritual wellbeing, Attitude toward Spiritual Care and its Relationship with Spiritual Care Competence among Critical Care Nurses. Journal of Caring Sciences. 2015;4(4):309–320. doi: 10.15171/jcs.2015.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulkedid R., Abdoul H., Loustau M., Sibony O., Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2011;(6):6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V., Hayfield N., Terry G. Thematic Analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Singapore. 2019 doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield C., Taylor D., Nagy K., Strauser C., VanKerkhove K., Wills S., Sorrell J. Critical Care Nurses Perceived Need for Guidance in Addressing Spirituality in Critically Ill Patients. American Journal of Critical Care. 2016;25(3):206–211. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2016276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-Correa M.I. Apoyo espiritual en casos de emergencia desastres o catástrofes. Centro San Camilo Vida y Salud. 2014;(69):69. [Google Scholar]

- Choi P.J., Curlin F.A., Cox C.E. Addressing religion and spirituality in the intensive care unit: A survey of clinicians. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2019;17(2):159–164. doi: 10.1017/S147895151800010X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero R.D., Romero B.B., de Matos F.A., Costa E., Espinha D.C.M., Tomasso C.S., Lucchetti G. Opinions and attitudes on the relationship between spirituality, religiosity and health: A comparison between nursing students from Brazil and Portugal. Journal of clinical nursing. 2018;27(13-14):2804–2813. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curlin F.A., Lawrence R.E., Chin M.H., Lantos J.D. Religion, conscience, and controversial clinical practices. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356(6):593–600. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa065316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood F.S., Ricks P., Njie G.J., Daugherty M., Davis W., Fuller J.A., Bennett S.D. Observations of the global epidemiology of COVID-19 from the prepandemic period using web-based surveillance: a cross-sectional analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(11):1255–1262. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30581-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito F.M., Costa Pinto, I C., Andrade Garrido de, C Oliveira de Lima, K F., M E. Spirituality in iminent death: Strategy utilized to humanize care in nursing. Revista Enfermagem. 2013;21(4):483–489. doi: 10.12957/reuerj.2013.10013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo F.A. Health, spirituality and Covid-19: Themes and insights. Journal of Public Health. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell B.R., Handzo G., Picchi T., Puchalski C., Rosa W.E. The urgency of spiritual care: COVID-19 and the critical need for whole-person palliation. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2020;60(3):7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel L.E.K., Webb S.A.R. Preparing ICUs for pandemics. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2013;19(5):467–473. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328364d645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallison B.S., Xu Y., Jurgens C.Y., Boyle S.M. Acute care nurses spiritual care practices. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2013;31(2):95–103. doi: 10.1177/0898010112464121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari H., Karimollahi M., Mehrnoush N. Evaluation of the perception of Iranian nurses towards spirituality in NICUs. Iranian Journal of Neonatology. 2016;7(2):35–39. doi: 10.22038/ijn.2016.7114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom G.M.A. Sampling issues in qualitative research. Nurse Researcher. 2004;12(1):7–19. doi: 10.7748/nr2004.07.12.1.7.c5927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijer H.A.-S., Bejjani R., Fares S. Quality of care, spirituality, relationships and finances in older adult palliative care patients in Lebanon. Annals of Palliative Medicine. 2019;8(5):551–558. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.09.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Bauck A., Monroe A., Mallory M., Aslakson R. Critical care nurses’ perceptions of and experiences with chaplains. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2017;19(1):41–48. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H., Parkerson, G. R., Jr., & Meador, K. G. (1997). Religion index for psychiatric research. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(6), 885–886. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.885b [DOI] [PubMed]

- Koenig H.G. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012:1–33. doi: 10.5402/2012/278730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukouli S., Lambraki M., Sigala E., Alevizaki A., Stavropoulou A. The experience of Greek families of critically ill patients: Exploring their needs and coping strategies. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2018;45:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk O., Roszkowski K., Montane X., Pawliszak W., Tylkowski B., Bajek A. Religion and Faith Perception in a Pandemic of COVID-19. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti G., Góes L.G., Amaral S.G., Ganadjian G.T., Andrade I., Almeida P.O., Manso M.E.G. Spirituality, religiosity and the mental health consequences of social isolation during Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020970996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti G., Lucchetti A.L. Spirituality, religion, and health: over the last 15 years of field research (1999-2013) International journal of psychiatry in medicine. 2014;48(3):199–215. doi: 10.2190/PM.48.3.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg P.C., Kerdonfag P. Spiritual care provided by Thai nurses in intensive care units. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(7–8):1121–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare (2020) Actualización n° 191. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19). Availble at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_191_COVID. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Muecke, M.A. (1994). On the Evaluation of Ethnographies; Morse, J.M., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 187, ISBN 0-8039-5042-X.

- Nascimento L.C., Alvarenga W.A., Caldeira S., Mica T.M., Oliveira F.C.S., Pan R., Vieira M. Spiritual care: The nurses’ experiences in the pediatric intensive care unit. Religions. 2016;7(3):1–11. doi: 10.3390/rel7030027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan S., Saltmarsh P., Leget C. Spiritual care in palliative care: Working towards an EAPC Task Force. European Journal of Palliative Care. 2011;18(2):86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Observatory of Religious Pluralism in Spain (2011). Guía de gestión de la diversidad religiosa en los centros hospitalarios. Madrid. Available at: http://www.observatorioreligion.es/upload/35/85/Guia_Hospitales.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2020

- Oosterbroek T, Yonge O, Myrick F. Participatory Action Research and Photovoice: Applicability, Relevance, and Process in Nursing Education Research. Nursing education perspectives. 2020 doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce A., Hoffer M., Marcinkowski B., Manfredi R.A., Pourmand A. Emergency department approach to spirituality care in the era of COVID-19. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riahi S., Goudarzi F., Hasanvand S., Abdollahzadeh H., Ebrahimzadeh F., Dadvari Z. Assessing the Effect of Spiritual Intelligence Training on Spiritual Care Competency in Critical Care Nurses. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2018;11(4):346–354. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman N.V., Mthembu T.G., Roman N. Spiritual care – ‘A deeper immunity’ – A response to Covid-19 pandemic Spiritual care in the South African. African journal of primary health care & family medicine. 2020;12(1):1–3. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S.G.S., Farrow A. A commentary on “World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) International Journal of Surgery. 2020;76:128–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonemanghkara R., Rozo J.A., Stutsman S. The Nurse-Chaplain-Family Spiritual Care Triad: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Christian Nursing : A Quarterly Publication of Nurses Christian Fellowship. 2019;36(2):112–118. doi: 10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan T., Yavuz Karamanoǧlu A. Determining intensive care unit nurses’ perceptions and practice levels of spiritual care in Turkey. Nursing in Critical Care. 2013;18(2):70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urra E., Muñoz A., Peña J. El análisis del discurso como perspectiva metodológica para investigadores de salud. Enfermería Universitaria. 2013;10(2):50–57. doi: 10.1016/S1665-7063(13)72629-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos A., Lucchetti A., Cavalcanti A., da Silva Conde S., Gonçalves L.M., do Nascimento F.R., Lucchetti G. Religiosity and Spirituality of Resident Physicians and Implications for Clinical Practice-the SBRAMER Multicenter Study. Journal of general internal medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 1998. WHOQOL and Spirituality, Religiousness and Personal Beliefs (SRPB) pp. 1–162.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70897 Available at: Accessed October 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]