Abstract

In Germany it is currently recommended that women start mammographic breast cancer screening at age 50. However, recently updated guidelines state that for women younger than 50 and older than 70 years of age, screening decisions should be based on individual risk. International clinical guidelines recommend starting screening when a woman’s 5-year risk of breast cancer exceeds 1.7%. We thus compared the performance of the current age-based screening practice to an alternative risk-adapted approach using data from a German population-representative survey. We found that 10,498,000 German women ages 50–69 years are eligible for mammographic screening based on age alone. Applying the 5-year risk threshold of 1.7% to individual breast cancer risk estimated from a model that considers a woman’s reproductive and personal characteristics, 39,000 German women ages 40–49 years would additionally be eligible. Among those women, the number needed to screen to detect one breast cancer case, NNS, was 282, which was close to the NNS=292 among all 50–69 year old women. In contrast, NNS=703 for the 113 000 German women ages 50–69 years old with 5-year breast cancer risk <0.8%, the median 5-year breast cancer risk for German women aged 45–49 years, which we used as a low-risk threshold. For these low-risk women longer screening intervals might be considered to avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures.

In conclusion, we show that risk adapted mammographic screening could benefit German women ages 40–49 who are at elevated breast cancer risk and reduce cost and burden among low-risk women ages 50–69.

Keywords: breast cancer, breast cancer risk assessment, mammography, risk adapted screening

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common female cancer in developing and developed countries (1). In Germany, 68,950 women were diagnosed with BC and 18,570 women died of the disease in 2016 (2). The number of BC cases in Germany is projected to increase (3), due to aging of the population and changes in reproductive behaviour, e.g. a higher proportion of childless women, later ages at first birth and lower breastfeeding rates, and changes in lifestyle, including diet and exercise habits (2).

The German mammographic screening program (MSP), established in 2009, invites all women ages 50–69 for a mammogram every two years. The program aims to reduce BC related mortality by detecting cancers early, but there is ongoing debate about efficacy of screening mammography, the potential of overdiagnosis, the optimal age to initiate screening, screening intervals and potential harmful effects (4, 5). Recently updated German guidelines state that for women younger than 50 and older than 70 “screening decisions based on individual risk” should be considered, and recommend screening women ages 40–49 who are at “moderate BC risk” by ultrasound and mammography (6).

These recommendations acknowledge that the current age-based eligibility criteria for the German MSP for a woman from the general population do not account for other well-established breast cancer risk factors, e.g. a woman’s BC family history, her history of benign breast disease, her reproductive history, use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and other lifestyle factors (7). Recently developed risk models take some of these factors into account (7–9) and can facilitate implementing risk adapted screening approaches. Eligibility for screening based on risk can reduce unnecessary diagnostic procedures for women at low BC risk and target more intensive diagnostic procedures to women at elevated risk (6). These ideas also motivated two ongoing screening trials. The WISDOM trial was designed to compare annual mammography with a risk-based screening schedule in 100,000 US women ages 40–74 years (10). BC risk is estimated with the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) model that uses information from 76 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in addition to personal and clinical characteristics. MyPeBS (My Personal Breast Screening; https://mypebs.eu/) is an ongoing randomized study of 85,000 women ages 40–70 to assess the effectiveness of a risk-based BC screening strategy compared to screening according to regional guidelines in several European countries and Israel. BC risk is calculated with the BCSC and Tyrer-Cuzick models.

We recently showed that two models, BCRAT (11) and BCmod (12), that predict BC risk for women in the general US population, were well calibrated in German women ages 40–70 years using data from the prospective EPIC Germany cohort, and one-year BC predicted model risks estimated for all German women using the “German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults” (DEGS) agreed well with overall German BC incidence (13). Both models use questionnaire-based risk factor information that is easy and inexpensive to obtain.

In this paper, we use BCmod risk estimates from the DEGS survey to compare the current age-based screening strategy in Germany to a risk-based one. We apply recommendations of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (14), that annual mammographic screening should start when a woman’s 5-year risk of invasive breast cancer exceeds 1.7%, but also show results obtained when using lifetime risks, that were the basis of the German guidelines (6). We compare the numbers of women eligible for screening, the numbers of BC cases screened and the numbers of women needed to be screened to detect one breast cancer case (NNS) in Germany for age and risk-based screening approaches to inform future screening recommendations.

Methods

German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS)

We evaluated the distribution of BC-risk using data on 3,705 women participating in the cross-sectional DEGS survey, a nationally representative health survey (15). Using a two-stage stratified cluster sampling design, DEGS data were collected using standardized personal interviews, self-administered questionnaires and standardized measurements. Primary sampling units (PSUs) in the two-stage design are communities, stratified by districts and measures of urbanization. Within PSUs, random samples of individuals, stratified by 10-year age groups, were drawn from local population registers. Further details on the design and sampling procedures are provided in (15). The DEGS study protocol was approved by the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin ethics committee in September 2008 (No. EA2/047/08). The women sampled into DEGS can be weighted to represent the general German adult female population at the time of recruitment (2008–2011). Supplemental Table S1 shows the distribution of several breast cancer risk factors in women in DEGS ages 40 years or older.

Risk Model

BCmod predicts a woman’s risk of developing invasive BC over a specified time period (e.g. 5 years or lifetime), given her age, reproductive history and BC family history, her past history of biopsy and diagnosis of benign hyperplasia, her current body mass index (BMI), HRT use and alcohol consumption (12). The probability of developing BC is computed by combining relative risk estimates for a woman’s risk factors with attributable risk estimated from two large US cohorts and age-specific BC incidence and competing mortality rates from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. The model was well calibrated in German women (13).

Imputation of missing values and statistical analysis

Information on some predictors used in BCmod was not collected in DEGS, including age at first live birth, type and duration of HRT use, a past diagnosis of benign breast disease, and BC family history. As previously described (13), we used multiple imputation with chained regression equations (IVEware, (16)) and information on missing variables from 27,934 women in the German EPIC cohort study to generate 5 complete datasets (17). While EPIC is not representative of the overall German female population, its utilization for imputation is likely adequate, as the assumption underlying imputation is missing at random, i.e. conditional on the observed data the missing data in DEGS are similar to those in EPIC. We further compared the DEGS risk factor distributions after imputation with those from population-based controls sampled into two population-based German BC case control studies and found generally good agreement, suggesting unbiasedness of the imputation approach (Supplemental Table S2). Estimates were obtained for each imputed data set accommodating the complex survey design, and then combined across imputed datasets. Variances of the final estimates were computed using Rubin’s formula, thus fully incorporating the variability in estimates across imputed data sets. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA; procedures SURVEYMEANS, SURVEYFREQ, and MIANALYZE).

The number of women that need to be screened to detect one breast cancer case (NNS) was computed as the total number of women divided by the number of projected cases within one year of follow-up, overall or within groups. The number of cases was obtained by summing one-year projected risk estimates overall or in subgroups.

Results

Distribution of 5-year risk based on BCmod in age-groups of German women

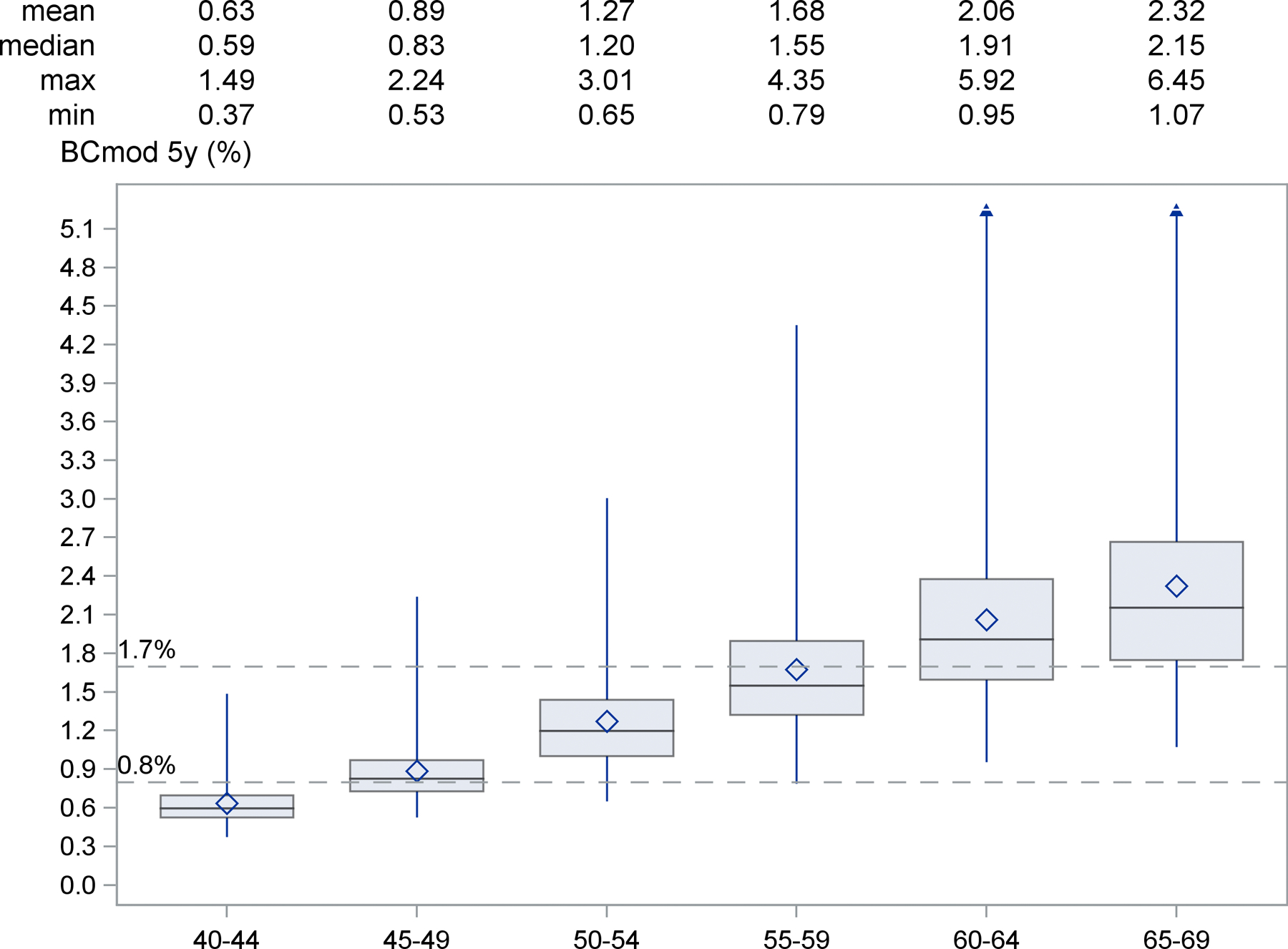

Figure 1 shows the estimated distribution of 5-year individual BCmod risks in German women for different age groups. The mean 5-year BC risk increased with increasing age group, ranging from 0.63% for women ages 40–44 years old to 2.32% for women ages 65–69 years. Among 40–44 years old women, the 5-year BC risk ranged from 0.37% to 1.49%, and no woman had a BC risk ≥1.7. However, among women ages 45–49 years old, 5-year BC risks ranged from 0.53% to 2.24%. The median risk was 0.83% for women 45–49 years, and we therefore used a risk of <0.8% to define “low-risk”. Among those ages 50–54 years, risks ranged from 0.65% to 3.01%. The mean 5-year risk of women ages 55–59 years was 1.68% (range 0.79% to 4.35%) and 2.06 for women ages 60–64 years. The median 5-year risk for women ages 60–64 years was 1.91% (range 0.95 to 5.92%) and it was 2.15% for ages 65–69 (range 1.07 to 6.45%; Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Distribution of 5-year risks based on BCmod in age-groups of German women (projected from DEGS)

The boxes are drawn from the first to the third quartile with the horizontal line drawn in the middle denoting the median, the diamond the mean value, and the whiskers ranging from minimum to maximum (except for ages 60+).

Based on BCmod estimates, 67% of the 6,721,000 German women ages 40–49 years had a 5-year BC risk higher than the lowest 5-year risk (0.65%) among 50-year old women (Table 1). These 40–49 years old women are currently not eligible for mammographic screening while a 50-year old woman with BC risk of 0.65% is.

Table 1:

Numbers and percent (%) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of German women ages 40 −49 with 5-year BC risk estimates (BCmod) below and above 0.6488%, the lowest estimated 5-year BC risk among women ages 50+.

| Risk group | Age 40–49 years | |

|---|---|---|

| 5-year risk <0.65% | 95% CI | |

| Total count | 2,250,000 | 1,777,850–2,721,957 |

| Percent | 33% | 27–40% |

| Number of BC cases expected within 1 year from risk assessment | 2,100 | 1,645 – 2,540 |

|

| ||

| 5-year risk≥0.65% | 95% CI | |

| Total count | 4,471,000 | 3,870,548–5,071,674 |

| Percent | 67% | 60–73% |

| Number of BC cases expected within 1 year from risk assessment | 6,800 | 5,905–7,721 |

| Total | ||

| Number of BC cases expected within 1 year from risk assessment | 8,900 | 8,026 – 9,784 |

Comparison of the age-based and risk-based screening strategies

According to the current age-based screening program, 10,498,000 German women ages 50–69 years are eligible for biennial mammograms. Of those 35,900 are expected to have a BC diagnosis within one year following risk assessment, corresponding to a number needed to screen to detect one case (NNS) of 292 (Table 2).

TABLE 2:

Total number of German women in each age group, percent in risk stratum and number of predicted breast cancer (BC) cases within one year of risk assessment estimated from the DEGS survey and the BCmod breast cancer risk prediction model. The number needed to screen (NNS) derived as the ratio of the total count and the number of expected BC cases. (CI= confidence interval)

| Age 40–44 years | Age 45–49 years | Age 50–69 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | ||||

| total population | ||||||

| Total count$ | 3,261,000 | 3,461,000 | 10,498,000 | |||

| Number of BC cases expected within 1 year from risk assessment | 3,400 | 5,500 | 35,900* | |||

| NNS | 953 | 631 | 292 | |||

| 5-year BC risk <0.8% | ||||||

| Total count$ | 2,871,000 | (2,399,498 – 3,343,261) | 1,494,000 | (1,157,169 – 1,831,468) | 113,000 | (38,486 – 187,825) |

| Percent | 88% | (79 – 97) | 43% | (35 – 51) | 1% | (0 – 2) |

| Number of BC cases expected within 1 year from risk assessment | 2,800 | (2,355 – 3,268) | 1,900 | (1,508 – 2,365) | 160 | (53 – 269) |

| NNS | 1,021 | 772 | 703 | |||

| 5-year BC risk 0.8%- 1.7% | ||||||

| Total count$ | 389,000 | (93,249 – 685,016) | 1,927,000 | (1,535,413 – 2,318,348) | 5,624,000 | (5,005,871 – 6,241,407) |

| Percent | 12% | (3 – 21) | 56% | (47 – 64) | 54% | (49 – 58) |

| Number of BC cases expected within 1 year from risk assessment | 600 | (158 – 1,064) | 3,400 | (2,694 – 4,120) | 13,800 | (12,309 – 15,280) |

| NNS | 637 | 566 | 408 | |||

| 5-year BC risk >1.7% | ||||||

| Total count$ | 0 | 39,000 | (0 – 145,620) | 4,761,000 | (4,150,573 – 5,371,914) | |

| Percent | 0% | 1% | (0 – 4) | 45% | (41– 50) | |

| Number of BC cases expected within 1 year from risk assessment | 0 | 140 | (0 – 510) | 22,000 | (19,261 – 24,709) | |

| NNS | na§ | 282 | 217 | |||

estimated from weighted survey data

differences due to rounding

no data available for estimation

Using a risk-based approach, 39,000 German women ages 45–49 years with 5-year risks >1.7% would be additionally eligible for mammographic screening; 140 of those are expected to be diagnosed with BC within one year (NNS=282, Table 2). This NNS is very close to that of women ages 50–69 years, and much lower than the NNS values for women ages 45–49 years with 5-year risks <0.8% and 0.8% to 1.7% (NNS=772 and NNS=566 respectively; Table 2). For women ages 40–44 years, NNS=1021 for those with 5-year risks <0.8% and NNS=637 for those with risk between 0.8% and 1.7% (Table 2).

Only 45% of German women ages 50–60 years had a 5-year BCmod risk ≥1.7%. As depicted in Figure 1, after age 55 most women had 5-year risk estimates ≥0.8%. There were 5,624,000 women ages 50–69 years old with risks between 0.8% and 1.7%, and 4,761,000 with risk ≥1.7%, with expected numbers of BC cases of 13.800 and 22,000 and NNS=408 and NNS=217, respectively. However, 113,000 women ages 50–69 years had a 5-year risk <0.8%; 160 BC diagnoses would be expected in the year following risk assessment, corresponding to NNS=703. These women might consider delaying screening until their 5-year risk (computed during annual routine-checks) rises above 0.8% (Table 2).

Based on remaining lifetime risks>16%, which is currently used in German guidelines (6), 78,000 women ages 40–49 years would be eligible for screening; 220 of those are expected to be diagnosed with BC, corresponding to NNS=358 (Supplemental Table S3).

Discussion/Conclusion

The current age-based mammography screening program in Germany is being re-evaluated (4, 5) and recent guidelines (6) recommend considering individualized risk in screening decisions for women <50 and >70 years old. This recommendation acknowledges that some younger women might benefit from screening (18) and that some unnecessary diagnostic procedures in older low-risk women could be avoided.

Based on NCCN Guidelines (14), annual mammographic screening for a woman <50 years should start when her 5-year invasive BC risk exceeds 1.7%. This risk-threshold corresponds to the average risk of a 60-year old US woman, for whom it is agreed upon that mammography screening is beneficial. The mean 5-year-risks in 55–59 and 60–64 year old German women were similar, 1.68 and 2.06%, respectively (Figure 1).

We therefore compared the numbers of women screened, the expected numbers of BC cases screened and the NNS in Germany when using the eligibility risk-cutoff of 1.7% for women 40–50 years old. We used the BCmod risk model for the risk-based calculations, as it was well calibrated in German women ages 40–77 and thus provides unbiased BC risk estimates (13). We calculated risk using DEGS survey data and found that 39,000 women (1%) ages 45–49 years would be eligible for mammographic screening. Using remaining life time risk (RLR)>16% as a basis for screening recommendation as suggested in the recent German guidelines (6), 78,000 German women ages 40–49 years would be eligible. However, using RLR is problematic, as a young woman can have a low short-term risk but large RLR based on the long remaining life time alone; additionally, risk models are typically validated only for shorter projection intervals (9).

The median 5-year risk among 45–49 year old women, who are currently not invited to screening, was 0.8%. Similar to the reasoning of the NCCN guidelines, one could thus also consider delaying screening for the 113,000 women ages 50–59 with risk estimates lower than 0.8%, as their risk is as low or lower than that of the median 45–49 year old for whom screening is currently not recommended. The low number of BC cases in this group is also reflected in the high number needed to screen, NNS=703. Risk estimates were almost universally above 0.8% for all women around age 55, suggesting a maximum delay of 5 years to screening initiation for women ages 50–59 with risk <0.8%.

Of note, risk-adapted screening is already implemented in Germany for women with high BC risks due to a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. They are offered intensified BC surveillance including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) starting ages 25 to 30 years (19).

The participation rate for the German MSP is 56%, below the European Union’s benchmark of acceptable participation (>70%) (20). Focusing resources, e.g. regularly assessing and discussing BC risk, could help to specifically motivate higher risk women to participate in screening and lower BC mortality.

A strength of our study is combining a well calibrated risk prediction model with a population representative survey to obtain numbers representative for Germany. However, there are some limitations. One is the modest sample size of the DEGS survey and imputation of some model predictors based on the EPIC cohort study. As EPIC is conducted in only two German locations (Heidelberg and Potsdam) the imputation could have biased the risk factor distribution compared to the overall German female population. However, when we compared the distribution of risk factors in DEGS after imputation to that observed in population-based controls from two German BC case-control studies there were few noticeable differences (Supplemental Table S2). Another limitation is that BCmod predicts incidence while the most relevant quantity for screening is the prevalence of clinically detectable BC. However, data from the BCSC suggest that prevalence is proportional to incidence in previously unscreened women. Under this proportionality assumption one can therefore use models that predict incidence to determine who should get screened. A limitation of BCmod is its modest discriminatory accuracy, with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of around 0.6 in German women (13). For a model with a higher AUC, the NNS would be further reduced (21). Thus models that add genetic and other molecular information, e.g. a polygenic risk score (PRS) are useful (22), with the trade-off that such data are more costly to obtain and some women might not agree to genetic measurements. A minor limitation is that BCMod does not include an important predictor of BC risk, breast density, as this information would not be available at the time a woman wants to decide when to start mammographic screening. However, it would be important to incorporate breast density information into decision making regarding screening intervals following an initial screen and deciding on the most appropriate screening modality. Both, PRS and breast density could help to further risk-stratify the 113,000 women ages 50–59 with BCmod risk estimates lower than 0.8%. However, importantly, as BCmod was well calibrated in German women (13) all our population-level calculations are unbiased and valid.

In summary, we showed that risk adapted mammographic screening could benefit women ages 40–49 who are at elevated BC risk, and reduce screening costs and burdens for low-risk women ages 50–69 compared to the current age-based screening practice. A possible screening strategy might be to regularly compute a woman’s 5-year BC risk starting at age 40 and then recommend screening when her risk surpasses a risk level common among older women (e.g. 1.7%, mean risk for ages 55–60). A model that additionally includes mammographic density could be used to update and refine risk estimates after a woman’s first mammogram (23) to help adapt screening intervals and to decide on the most appropriate modality. Considering all possible scenarios here goes beyond the scope of this paper and more work is needed to identify the optimal screening strategy and risk cut-offs with careful balancing of risks, benefits and costs. Such an analysis was conducted by Pashayan et al (24), who compared age-based screening for UK women every three years to targeted screening based on a model that contains age and a PRS and found a higher benefit to harm ratio for the risk-based strategy than the age-based approach.

We found that using age-based screening 10,498,000 biennial mammograms are administered and 35,900 BC cases detected among screened German women. Using a risk-based approach 10,424,000 mammograms (74,000 fewer) would lead to almost the same number of detected BC cases. However, risk adapted screening may be administratively more challenging and a careful weighing of potential costs, benefits and harms are needed before recommending its implementation in Germany.

Supplementary Material

Publication Relevance.

We show that a risk-based approach to mammography screening for German women can help detect breast cancer in women ages 40–49 years with increased risk and reduce screening costs and burdens for low risk women ages 50–69 years. However, before recommending a particular implementation of a risk based mammographic screening approach, further investigations of appropriate models and thresholds are needed.

Acknowledgement

We are indebted to Prof. Hiltrud Brauch and Prof. Peter Fasching who allowed us to present data from the GENICA and BBCC-studies for comparison (Supplemental Table S2). We very much appreciate the support from the Dr. Pommer-Jung Stiftung. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

“The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.”

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(6):394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krebs in Deutschland für 2015/2016 Berlin: Robert Koch Institute, Association of Population-based Cancer Registries in Germany; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quante AS, Ming C, Rottmann M, Engel J, Boeck S, Heinemann V, et al. Projections of cancer incidence and cancer-related deaths in Germany by 2020 and 2030. Cancer Med 2016;5(9):2649–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedewald SM. Breast cancer screening: the debate that never ends. Cancer treatment and research 2018;173:31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welch HG, Passow HJ. Quantifying the benefits and harms of screening mammography. JAMA internal medicine 2014;174(3):448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Früherkennung, Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie.Langversion 4.3 - Februar 2020(AWMF-Registernummer: 032–045OL)

- 7.Quante AS, Whittemore AS, Shriver T, Strauch K, Terry MB. Breast cancer risk assessment across the risk continuum: genetic and nongenetic risk factors contributing to differential model performance. Breast cancer research : BCR 2012;14(6):R144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee A, Mavaddat N, Wilcox AN, Cunningham AP, Carver T, Hartley S, et al. BOADICEA: a comprehensive breast cancer risk prediction model incorporating genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Genet Med 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Quante AS, Whittemore AS, Shriver T, Hopper JL, Strauch K, Terry MB. Practical problems with clinical guidelines for breast cancer prevention based on remaining lifetime risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eklund M, Broglio K, Yau C, Connor JT, Stover Fiscalini A, Esserman LJ. The WISDOM Personalized Breast Cancer Screening Trial: Simulation Study to Assess Potential Bias and Analytic Approaches. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2018;2(4):pky067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81(24):1879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeiffer RM, Park Y, Kreimer AR, Lacey JV Jr., Pee D, Greenlee RT, et al. Risk prediction for breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer in white women aged 50 y or older: Derivation and validation from population-based cohort studies. PLoSMed 2013;10(7):e1001492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husing A, Quante AS, Chang-Claude J, Aleksandrova K, Kaaks R, Pfeiffer RM. Validation of two US breast cancer risk prediction models in German women. Cancer Causes Control 2020;31(6):525–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, Calhoun KE, Camp M, Daly MB, et al. NCCN Guidelines - Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. 2019;NCCN Guidelines Version 1 2019

- 15.Scheidt-Nave C, Kamtsiuris P, Gosswald A, Holling H, Lange M, Busch MA, et al. German health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS) - design, objectives and implementation of the first data collection wave. BMC public health 2012;12:730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Hoewykand JV, Solenberger P. A Multivariate Technique for Multiply Imputing Missing Values Using a Sequence of Regression Models. Survey Methodology 2010;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boeing H, Wahrendorf J, Becker N. EPIC-Germany--A source for studies into diet and risk of chronic diseases. European Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Ann Nutr Metab 1999;43(4):195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellquist BN, Czene K, Hjalm A, Nystrom L, Jonsson H. Effectiveness of population-based service screening with mammography for women ages 40 to 49 years with a high or low risk of breast cancer: socioeconomic status, parity, and age at birth of first child. Cancer 2015;121(2):251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmutzler R Konsensusempfehlung des Deutschen Konsortiums Familiärer Brust- und Eierstockkrebs zum Umgang mit Ergebnissen der Multigenanalyse. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde 2017;77:733–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kääb-Sanyal V, Wegener B, Malek D. Jahresbericht Qualitätssicherung 2012, Deutsches Mammographie-Screening-Programm Berlin: Kooperationsgemeinschaft Mammographie; August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gail MH, Pfeiffer RM. Breast Cancer Risk Model Requirements for Counseling, Prevention, and Screening. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018;110(9):994–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pal Choudhury P, Wilcox AN, Brook MN, Zhang Y, Ahearn T, Orr N, et al. Comparative validation of breast cancer risk prediction models and projections for future risk stratification. J Natl Cancer Inst 2020;112(3):278–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Pee D, Ayyagari R, Graubard B, Schairer C, Byrne C, et al. Projecting absolute invasive breast cancer risk in white women with a model that includes mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98(17):1215–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pashayan N, Morris S, Gilbert FJ, Pharoah PDP. Cost-effectiveness and Benefit-to-Harm Ratio of Risk-Stratified Screening for Breast Cancer: A Life-Table Model. JAMA Oncol 2018;4(11):1504–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.