Abstract

Background

Evidence from disease epidemics shows that healthcare workers are at risk of developing short‐ and long‐term mental health problems. The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned about the potential negative impact of the COVID‐19 crisis on the mental well‐being of health and social care professionals. Symptoms of mental health problems commonly include depression, anxiety, stress, and additional cognitive and social problems; these can impact on function in the workplace. The mental health and resilience (ability to cope with the negative effects of stress) of frontline health and social care professionals ('frontline workers' in this review) could be supported during disease epidemics by workplace interventions, interventions to support basic daily needs, psychological support interventions, pharmacological interventions, or a combination of any or all of these.

Objectives

Objective 1: to assess the effects of interventions aimed at supporting the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic.

Objective 2: to identify barriers and facilitators that may impact on the implementation of interventions aimed at supporting the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic.

Search methods

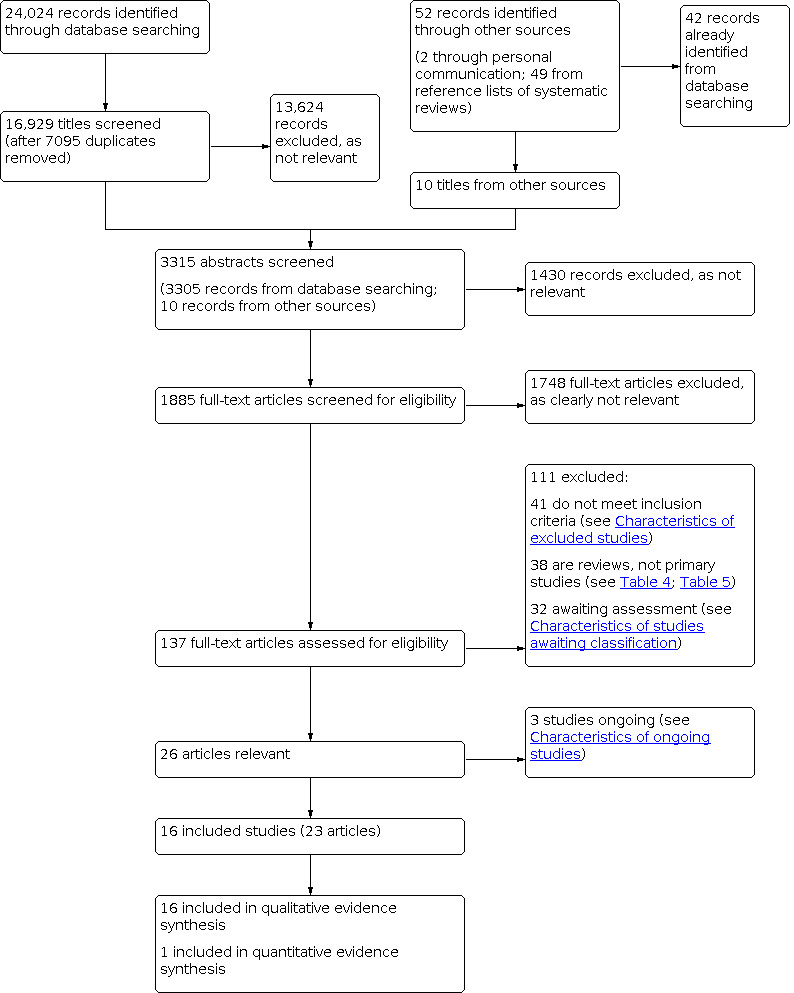

On 28 May 2020 we searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Global Index Medicus databases and WHO Institutional Repository for Information Sharing. We also searched ongoing trials registers and Google Scholar. We ran all searches from the year 2002 onwards, with no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included studies in which participants were health and social care professionals working at the front line during infectious disease outbreaks, categorised as epidemics or pandemics by WHO, from 2002 onwards. For objective 1 we included quantitative evidence from randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, controlled before‐after studies and interrupted time series studies, which investigated the effect of any intervention to support mental health or resilience, compared to no intervention, standard care, placebo or attention control intervention, or other active interventions. For objective 2 we included qualitative evidence from studies that described barriers and facilitators to the implementation of interventions. Outcomes critical to this review were general mental health and resilience. Additional outcomes included psychological symptoms of anxiety, depression or stress; burnout; other mental health disorders; workplace staffing; and adverse events arising from interventions.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of review authors independently applied selection criteria to abstracts and full papers, with disagreements resolved through discussion. One review author systematically extracted data, cross‐checked by a second review author. For objective 1, we assessed risk of bias of studies of effectiveness using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. For objective 2, we assessed methodological limitations using either the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) qualitative study tool, for qualitative studies, or WEIRD (Ways of Evaluating Important and Relevant Data) tool, for descriptive studies. We planned meta‐analyses of pairwise comparisons for outcomes if direct evidence were available. Two review authors extracted evidence relating to barriers and facilitators to implementation, organised these around the domains of the Consolidated Framework of Implementation Research, and used the GRADE‐CERQual approach to assess confidence in each finding. We planned to produce an overarching synthesis, bringing quantitative and qualitative findings together.

Main results

We included 16 studies that reported implementation of an intervention aimed at supporting the resilience or mental health of frontline workers during disease outbreaks (severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): 2; Ebola: 9; Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): 1; COVID‐19: 4). Interventions studied included workplace interventions, such as training, structure and communication (6 studies); psychological support interventions, such as counselling and psychology services (8 studies); and multifaceted interventions (2 studies).

Objective 1: a mixed‐methods study that incorporated a cluster‐randomised trial, investigating the effect of a work‐based intervention, provided very low‐certainty evidence about the effect of training frontline healthcare workers to deliver psychological first aid on a measure of burnout.

Objective 2: we included all 16 studies in our qualitative evidence synthesis; we classified seven as qualitative and nine as descriptive studies. We identified 17 key findings from multiple barriers and facilitators reported in studies. We did not have high confidence in any of the findings; we had moderate confidence in six findings and low to very low confidence in 11 findings. We are moderately confident that the following two factors were barriers to intervention implementation: frontline workers, or the organisations in which they worked, not being fully aware of what they needed to support their mental well‐being; and a lack of equipment, staff time or skills needed for an intervention. We are moderately confident that the following three factors were facilitators of intervention implementation: interventions that could be adapted for local needs; having effective communication, both formally and socially; and having positive, safe and supportive learning environments for frontline workers. We are moderately confident that the knowledge or beliefs, or both, that people have about an intervention can act as either barriers or facilitators to implementation of the intervention.

Authors' conclusions

There is a lack of both quantitative and qualitative evidence from studies carried out during or after disease epidemics and pandemics that can inform the selection of interventions that are beneficial to the resilience and mental health of frontline workers. Alternative sources of evidence (e.g. from other healthcare crises, and general evidence about interventions that support mental well‐being) could therefore be used to inform decision making. When selecting interventions aimed at supporting frontline workers' mental health, organisational, social, personal, and psychological factors may all be important. Research to determine the effectiveness of interventions is a high priority. The COVID‐19 pandemic provides unique opportunities for robust evaluation of interventions. Future studies must be developed with appropriately rigorous planning, including development, peer review and transparent reporting of research protocols, following guidance and standards for best practice, and with appropriate length of follow‐up. Factors that may act as barriers and facilitators to implementation of interventions should be considered during the planning of future research and when selecting interventions to deliver within local settings.

Plain language summary

What is the best way to support resilience and mental well‐being in frontline healthcare professionals during and after a pandemic?

What is ‘resilience’?

Working as a 'frontline' health or social care professional during a global disease pandemic, like COVID‐19, can be very stressful. Over time, the negative effects of stress can lead to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, which, in turn, may affect work, family and other social relationships. ‘Resilience’ is the ability to cope with the negative effects of stress and so avoid mental health problems and their wider effects.

Healthcare providers can use various strategies (interventions) to support resilience and mental well‐being in their frontline healthcare professionals. These could include work‐based interventions, such as changing routines or improving equipment; or psychological support interventions, such as counselling.

What did we want to find out?

First (objective 1), we wanted to know how successfully any interventions improved frontline health professionals’ resilience or mental well‐being.

Second (objective 2), we wanted to know what made it easier (facilitators) or harder (barriers) to deliver these interventions.

What did we do?

We searched medical databases for any kind of study that investigated interventions designed to support resilience and mental well‐being in healthcare professionals working at the front line during infectious disease outbreaks. The disease outbreaks had to be classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as epidemics or pandemics, and take place from 2002 onwards (the year before the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak).

What did we find?

We found 16 relevant studies. These studies came from different disease outbreaks ‐ two were from SARS; nine from Ebola; one from Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS); and four from COVID‐19. The studies mainly looked at workplace interventions that involved either psychological support (for example, counselling or seeing a psychologist) or work‐based interventions (for example, giving training, or changing routines).

Objective 1: one study investigated how well an intervention worked. This study was carried out immediately after the Ebola outbreak, and investigated whether staff who were training to give other people (such as patients and their family members) 'psychological first aid' felt less ‘burnt out’. We had some concerns about the results that this study reported and about some of its methods. This means that our certainty of the evidence is very low and we cannot say whether the intervention helped or not.

Objective 2: all 16 studies provided some evidence about barriers and facilitators to implement interventions. We found 17 main findings from these studies. We do not have high confidence in any of the findings; we had moderate confidence in six findings and low to very low confidence in 11 findings.

We are moderately confident that the following two factors were barriers to implementation of an intervention: frontline workers, or the organisations in which they worked, not being fully aware of what they needed to support their mental well‐being; and a lack of equipment, staff time or skills needed for an intervention.

We are moderately confident that the following three factors were facilitators to implementation of an intervention: interventions that could be adapted for a local area; having effective communication, both formally within an organisation and informal or social networks; and having positive, safe and supportive learning environments for frontline healthcare professionals.

We are moderately confident that the knowledge and beliefs that frontline healthcare professionals have about an intervention can either help or hinder implementation of the intervention.

Key messages

We did not find any evidence that tells us about how well different strategies work at supporting the resilience and mental well‐being of frontline workers. We found some limited evidence about things that might help successful delivery of interventions. Properly planned research studies to find out the best ways to support the resilience and mental well‐being of health and social care workers are urgently required.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

This review includes studies published up to 28 May 2020.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Evidence from infectious disease epidemics has shown that healthcare workers are at risk of developing both short‐ and long‐term mental health problems (Maunder 2006), with up to one‐third of frontline healthcare workers experiencing high levels of distress (Lynch 2020). Health and social care professionals may develop a lack of resilience or mental health problems, or both, as a result of working in a variety of stressful situations. However, working during or immediately after an outbreak of an infectious disease which has, or has the potential to, overwhelm the health and social care system, may have a particularly negative impact on the health and well‐being of individual health and social care staff and on the maintenance of a functional workforce and healthcare system. The common work‐related factors affecting mental health and well‐being during a pandemic include: concern about exposure to the virus; personal and family needs and responsibilities; managing a different workload; lack of access to necessary tools and equipment (including personal protection equipment, PPE); feelings of guilt relating to the lack of contribution; uncertainty about the future of the workplace or employment; learning new technical skills; and adapting to a different workplace or schedule (CDC 2020a; Houghton 2020; Shanafelt 2020).

The mental health of frontline health and social care professionals may also be negatively affected by witnessing death, and feeling powerless over the levels of patient death. During epidemics of contagious diseases, frontline health and social care professionals may experience particular concerns around the risk of infection and re‐infection. These can have adverse effects on individual health and social care professionals, the delivery of patient care, and the capacity of healthcare systems to respond to the increased demands during a disease epidemic or pandemic (Kang 2020).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as "a state of well‐being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community" (WHO 2004). The term 'mental health' describes someone's psychological and emotional well‐being, and good mental health can be considered to be "a positive state of mind and body, feeling safe and able to cope, with a sense of connection with people, communities and the wider environment" (Strathdee 2015). Symptoms associated with mental health problems commonly include depression, anxiety, or stress. Mental health problems can result in additional cognitive and social problems, and can lead to long‐term issues, including post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These problems can impact on function in the workplace, while a negative working environment can lead to mental health problems (WHO 2019a).

Possible symptoms that frontline health and social care professionals may experience include: feelings of irritation, anger, uncertainty, stress, nervousness or anxiety; lack of motivation; tiredness; feeling sad, depressed or overwhelmed; difficulty in sleeping or concentrating (CDC 2020a). Negative effects of mental health may result in unhealthy behaviours, such as alcohol, tobacco or drug abuse, which may contribute to reduced ability to function at work (CDC 2020b). Moreover, these unhealthy behaviours could also potentially be linked to family breakdown and domestic abuse, further increasing feelings of depression, anxiety and stress and impacting negatively on ability to function. Health and social care professionals experiencing mental health problems may have high levels of absenteeism or presenteeism (turning up for work when unable to function in an optimal way).

Definitions of resilience vary, but often refer to the ability to cope with negative effects of stress or adversity. For the purposes of this review, we define resilience as a dynamic, multifactorial process in which an individual can “adjust to adversity, maintain equilibrium, retain some sense of control over their environment, and continue to move on in a positive manner” (Jackson 2007). Often resilience is contrasted with the concept of burnout, which is characterised by distress and exhaustion, and dysfunction at work (WHO 2019b).

A pandemic is defined as a global outbreak of a disease (WHO 2020a), while an epidemic is a greater than normal expected number of cases of a disease in a population, often with a sudden increase in cases (CDC 2011). Pandemics are generally classified as epidemics prior to reclassification as a pandemic if there is global spread of a disease. While declarations of diseases as epidemics or pandemics are not always clear, and local outbreaks of a disease may or may not be categorised as an epidemic by local government or health service organisations, the WHO plays a key role in international detection and classification of epidemics and pandemics. Within this review we focus on infectious diseases that have been categorised by WHO 2020a as "pandemic or epidemic diseases", as these diseases arguably have the greatest potential to affect adversely the mental well‐being and resilience of health and social care professionals and, consequently, the function of health and social care systems and the delivery of patient care.

Description of the intervention

A number of strategies have been recommended to support the mental health and well‐being of frontline health and social care professionals during disease outbreaks. These include accurate work‐related information, regular breaks, adequate rest and sleep, a healthy diet, physical activity, peer support, family support, avoidance of unhelpful coping strategies (e.g. alcohol and drugs), limitation of social media use, and professional counselling or psychological services. During the COVID‐19 pandemic, healthcare managers have been urged to consider the long‐term impact on their workers, and to ensure clear communication with staff (WHO 2020b). Several strategies that healthcare providers could implement have been proposed, such as rotating workers from higher‐ to lower‐stress roles, partnering experienced and less experienced workers (buddy systems), initiation and monitoring of work breaks, flexible schedules, and provision of social support (WHO 2020b). Training key staff members in 'psychological first aid' has been proposed to provide basic emotional and practical support to people affected by their stressful work environment. Interventions aim to strengthen and maintain personal resilience, enabling a worker to manage their experiences and increased work‐related demands and continue to perform well in the workplace (Robertson 2016).

How the intervention might work

Interventions aimed at supporting the mental health and well‐being of frontline health and social care professionals, or helping them cope with highly stressful or anxiety‐provoking situations, may work in a variety of different ways. The WHO highlights that the promotion of positive mental health and the prevention of negative mental health consequences are overlapping and complementary activities (WHO 2002). Interventions might work in the following ways.

Changing the workplace or organisation of work. These interventions may work by adjusting work practices or providing opportunities for rest and relaxation during the workday,or both (e.g. regular breaks, shorter working hours, regular team meetings, relaxation/recreation areas in workplaces), or by enabling workers to cope better (e.g. through provision of information, guidance, mentorship, or training). These strategies might work by reducing stress to a manageable level, by providing time for health and social care professionals to develop or optimise their own coping mechanisms or support systems, or by placing a worker away from frontline work for a period of time.

Supporting the basic daily needs of frontline health and social care professionals. These interventions may promote or support a healthy lifestyle and self‐care, such as eating, sleeping, exercising, following a routine, avoiding excess social media, staying in touch with family and friends, doing things that are enjoyable; or may comprise the use of techniques such as progressive muscle relaxation or meditation, which aim to help stop ‐ or distract from ‐ negative thoughts. While there are a number of studies that report a link between lifestyle changes and mental health benefits, the underlying mechanisms have not been fully established. The benefits of physical activity are proposed to be associated with a range of neurobiological, psychosocial and behavioural mechanisms (Lubans 2016).

Providing psychological support. These interventions may use cognitive‐behavioural techniques to help people find ways to stop negative cycles of thoughts and to change the way they respond to things that make them feel anxious or distressed. Interventions may include: self‐help management techniques (e.g. online cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), mindfulness, writing down worries) including the use of well‐being and sleep apps; and professional psychological or counselling support (e.g. talking therapies, support groups or psychotherapy, which can include CBT). These psychological support mechanisms can also teach people how to avoid unhelpful coping strategies.

Medication (e.g. prescribed medication for depression, anxiety, sleep problems and/or other mental disorders). Antidepressant drugs can act on neurochemicals in the brain, but may also mediate complex neuroplastic and neuropsychological mechanisms (Harmer 2017).

It is thought that workplace stress can negatively impact resilience, but that processes of adaptation and personal development can potentially build resilience and influence the ability to cope with stressful situations (Robertson 2016). Strategies to strengthen and maintain personal resilience within a workplace may incorporate the development of positive relationships and networks (e.g. through mentorship), as well as personal skills, such as emotional insight and maintaining a healthy work‐life balance (Jackson 2007). Evidence suggests that recovery‐enhancing interventions, such as relaxation, physical activity, stress management and workplace changes, may prevent the development of ill health amongst workers (Verbeek 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

In March 2020, the WHO declared the COVID‐19 coronavirus outbreak a pandemic (WHO 2020c), and warned about the potential negative impact of the crisis on the psychological and mental well‐being throughout the population, including and, in particular, health and social care professionals (WHO 2020b).

The negative impact on health and social care professions may result in effects at multiple levels, from the individual worker to the entire health and social care system at the macro level. This topic was identified as a high priority for a rapid review by the Cochrane COVID‐19 rapid reviews initiative (Priority Question 78).

This review is important in order to inform recommendations to support the mental health of frontline personnel during the COVID‐19 crisis and during the subsequent (‘de‐escalation’) phase, and during other disease epidemics and pandemics. This is important for the health and well‐being of individual health and social care staff and for the maintenance of a functional workforce and healthcare system.

There are currently a number of systematic reviews that synthesise evidence relating to workplace health and well‐being, including several that focus on issues relevant to mental health, or resilience, or both. Key Cochrane Reviews and protocols that are potentially relevant to this topic are summarised in Table 3. These include two reviews and one protocol specifically focused on the population of healthcare workers, addressing issues relating to prevention (Ruotsalainen 2015), and reduction (Giga 2018, protocol) of workplace stress and fostering of workplace resilience (Kunzler 2020). Ruotsalainen 2015 reports moderate‐certainty evidence that physical relaxation may reduce stress levels of healthcare workers, as compared to no intervention, low‐certainty evidence that stress levels of healthcare workers may reduce following cognitive‐behavioural intervention (with or without relaxation) as compared to no intervention, and low‐certainty evidence that changing work schedules of healthcare workers may reduce stress levels. Kunzler 2020 reports that there is very low‐certainty evidence that resilience training for healthcare professionals may result in higher levels of resilience, lower levels of depression, stress or stress perception, and higher levels of some resilience factors, as compared to control. Furthermore, there are reviews summarising evidence relating to general well‐being of workers, including issues such as stress and sleep; workers with diagnosed mental health problems; and issues associated with sick leave and return to work (see Table 3).

1. Summary of Cochrane Reviews and protocols potentially relevant to workplace mental health, resilience, or both.

| Review | Review title | Population | Interventions | Outcomes |

| Reviews focused specifically on healthcare workers/professionals | ||||

| Giga 2018 | Organisational‐level interventions for reducing occupational stress in healthcare workers (protocol) | "adult workers, aged 18 years or above, employed in a healthcare setting, who have not actively sought help for conditions such as stress and burnout. This includes workers, such as nurses and physicians, who are in training and undertaking clinical work" | "organisational level interventions aimed at reducing stress. Eligible interventions include the following.

|

|

| Kunzler 2020 | Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals | "Adults aged 18 years and older, who are employed as healthcare professionals, i.e. healthcare staff delivering direct medical care such as physicians, nurses, hospital personnel, and allied healthcare staff working in health professions, as distinct from medical care (e.g. psychologists, social workers, counsellors, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, medical assistants, medical technicians)" | "Any psychological resilience intervention, irrespective of content, duration, setting or delivery mode." |

|

| Ruotsalainen 2015 | Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers | "healthcare workers officially employed in any healthcare setting or at student nurses or physicians otherwise in training to become a professional who were also doing clinical work" "workers who had not actively sought help for conditions such as burnout, depression or anxiety disorder" |

"any kind of intervention aimed at preventing or reducing stress arising from work." Including:

|

|

| Reviews focused on participants with diagnosed mental health problems | ||||

| Nieuwenhuijsen 2014 | Interventions to improve return to work in depressed people | "adult (that is over 17 years old) workers (employees or self‐employed)" | "all interventions aimed at reducing work disability, thereby differentiating work‐directed interventions from clinical interventions." |

|

| Suijkerbuijk 2017 | Interventions for obtaining and maintaining employment in adults with severe mental illness, a network meta‐analysis | "adults aged between 18 and 70 years who had been diagnosed with severe mental illness. We defined severe mental illness as schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, depression with psychotic features or other long‐lasting psychiatric disorders, with a disability in social functioning or participating in society, such as personality disorder, severe anxiety disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder, major depression or autism with a duration of at least two years. Study participants had to be unemployed due to severe mental illness." | "We included trials of all types of vocational rehabilitation compared to each other or to no intervention or psychiatric care only." These included:

|

|

| Reviews focused on sick leave, absenteeism, job loss and/or return to work | ||||

| Kausto 2019 | Self‐certification versus physician certification of sick leave for reducing sickness absence and associated costs | "individual employees or insured workers" | "We included studies evaluating the effects of introducing, abolishing, or changing the period of self‐certification of sickness absence. We included any sickness certification practice in which the employee could report sick for a certain number of days without physician certification or certification by any other healthcare professional. Self‐certification could be accepted for any disease or restricted to certain types of diseases. We also included studies that combined self‐certification with an intervention related to supervisor role or practices, working conditions (e.g. flexible working conditions), or terms of sickness benefit (e.g. number of waiting days), etc. (i.e. multicomponent interventions)." |

|

| Liira 2016 | Workplace interventions for preventing job loss and other work‐related outcomes in workers with alcohol misuse (protocol) | "workers with alcohol misuse aged 18 years or above.......participants who fulfil the criteria for hazardous drinking, that is, weekly drinking an amount that regularly exceeds 190 grams of pure alcohol for men or 100 grams for women, as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism" | "interventions that target either the workplace, work team or the individual worker" |

|

| Vogel 2017 | Return‐to‐work co‐ordination programmes for improving return to work in workers on sick leave | "adults of working age (16 to 65 years) who:

|

Return‐to‐work co‐ordination programmes, defined as:

|

|

| Reviews focused on well‐being of employees (not specifically healthcare workers) | ||||

| Erren 2013 | Adaptation of shift work schedules for preventing and treating sleepiness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work (protocol) | "any adult workers (age > 18) in shift work schedules that include night shift work, irrespective of industry, country, age or comorbidities" | "any intervention that deals with a shift work schedule" |

|

| Kuehnl 2019 | Human resource management training of supervisors for improving health and well‐being of employees | "any type of supervisors, of any gender and their dependently employed subordinates of any gender. For the purpose of this review a supervisor was defined as a person who has the authority to give instructions to at least one subordinate and is held responsible for their work and actions. We included studies that had been conducted in profit, non‐profit or governmental organisations, that is, in a real working environment." | Human resource management training of supervisors, including:

|

|

| Kuster 2017 | Computer‐based versus in‐person interventions for preventing and reducing stress in workers | "full‐time, part‐time, or self‐employed working individuals over 18 years of age" | "any type of worker‐focused web‐based stress management intervention, aimed at preventing or reducing work‐related stress with techniques such as CBT, relaxation, time management, or problem‐solving skills training. These interventions had to be delivered via email, a website, or a stand‐alone computer programme" |

|

| Liira 2014 | Pharmacological interventions for sleepiness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work | "workers who undertake shift work (including night shifts) in their present jobs and who may or may not have sleep problems." | "any pharmacological intervention aimed at preventing or reducing sleepiness at work or sleep disturbances caused by shift work" |

|

| Naghieh 2015 | Organisational interventions for improving well‐being and reducing work‐related stress in teachers | "teachers working at primary and secondary schools, serving children aged between 4 and 18 years." | "Organisational interventions for employee wellbeing target the stressors in the work environment, rather than the stress response of the individual employee. They aim to alter the psychosocial work environment by changing some aspect of the organisation, such as structures, policies, processes, climate, programmes, roles, tasks, etc." |

|

| Pachito 2018 | Workplace lighting for improving alertness and mood in daytime workers | "adults aged 18 years and above performing work exclusively indoors, in the period restricted to 7:00 am to 10:00 pm, irrespective of type of work, industry and comorbidities" | "different types of light interventions" |

|

| Slanger 2016 | Person‐directed, non‐pharmacological interventions for sleepiness at work and sleep disturbances caused by shift work | "adult workers engaged in shift work schedules that include night‐shift work, irrespective of industry, country, age or comorbidities." | "any person‐directed, non‐pharmacological intervention" |

|

| CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; WHO: World Health Organization | ||||

While these Cochrane Reviews provide evidence that there are interventions that can benefit the mental well‐being of healthcare workers, this evidence is not specific to health and social care workers in frontline positions during disease outbreaks. As described above, the work of frontline health and social care professionals during a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic places a unique burden on the mental health and resilience of these workers and – as such – a separate review with this specific focus is merited. Furthermore, the current body of Cochrane Reviews focuses on the synthesis of quantitative evidence of effectiveness of interventions, and these do not incorporate qualitative evidence relating to the barriers and facilitators to implementation of these interventions. During disease epidemics and pandemics there may be particular challenges to implementation of workplace, or worker‐focused, interventions, and it is therefore important to bring both quantitative and qualitative evidence together. This review is therefore important as it will bring unique evidence, which is relevant and useful to decision making relating to interventions to support mental health and resilience of frontline health and social care professionals during disease outbreaks. This will create accessible evidence, highly relevant to decision‐making during, and planning for, any future outbreaks of COVID‐19 or other disease pandemics.

Objectives

Objective 1: to assess the effects of interventions aimed at supporting the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic.

Objective 2: to identify barriers and facilitators that may impact on the implementation of interventions aimed at supporting the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

To address objective 1, we included quantitative evidence from the following.

Randomised trials: experimental studies in which people are allocated to different interventions using methods that are random. We included cluster‐randomised trials, in which randomisation is at the level of the site, where a study has at least two intervention sites and two control sites (EPOC 2017a).

Non‐randomised trials: experimental studies in which people are allocated to different interventions using methods that are not random (EPOC 2017a).

Controlled before‐after studies: studies in which observations are made before and after the implementation of an intervention, both in a group that receives the intervention and in a control group that does not (EPOC 2017a).

Interrupted time series studies: studies that use observations at multiple time points before and after an intervention (the ‘interruption’). The design attempts to detect whether the intervention has had an effect significantly greater than any underlying trend over time. For inclusion, these studies must have a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred, and at least three data points before and three after the intervention (EPOC 2017a).

We planned to include evidence from non‐randomised studies as the planning and conduct of randomised studies is likely to be highly challenging during disease epidemics and pandemics. However, evidence from non‐randomised studies has an increased risk of bias; in particular there are a number of confounding factors that may influence whether an individual receives one or other intervention. In relation to interventions to support the mental health and resilience of health and social care professionals, important confounding factors were likely to include the setting that the healthcare professional is working in, the type and grade of health professional, and the length of time that the individual has worked within the disease epidemic or pandemic. Furthermore, there are known differences between men and women in the reporting of mental health symptoms and treatment rates for symptoms such as depression and anxiety, therefore gender may have been a confounding domain (MHF 2016). There is also a growing body of evidence that socioeconomic status may be associated with an increased chance of developing mental health problems (WHO 2014a), and this could be an important confounding factor in some studies. If these important confounding factors were not controlled for within the non‐randomised study, we planned to judge the study to be at high risk of bias.

We excluded evidence from non‐randomised studies in which the interventions were not assigned by the investigators, including prospective and retrospective cohort and case‐control studies.

To address objective 2, we included any papers that described barriers or facilitators to implementation of an intervention. Papers could report a qualitative, quantitative or descriptive study. We classified papers that:

reported a pre‐planned qualitative method of data collection (e.g. interviews) as 'qualitative studies';

reported a pre‐planned quantitative method of data collection (e.g. cohort study) as 'quantitative studies';

reported a pre‐planned study that combined qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection as 'mixed methods studies';

described factors relating to implementation of an intervention, but that did not report a pre‐planned or systematic method of data collection as 'descriptive studies'.

Our classification of studies was based on the type of data extracted and used for our qualitative evidence synthesis, rather than on the pre‐planned study design; for example, we classified a mixed methods study from which we only used qualitative data as a 'qualitative study', and we classified a quantitative study from which we only used descriptive data as a 'descriptive study'.

We excluded secondary research (systematic reviews and evidence syntheses). However, where we found relevant secondary research studies, we considered any primary studies included in these reviews, and included any that met our inclusion criteria.

Types of participants

We included studies in which participants were (or had been) health and social care professionals working at the front line during disease outbreaks, epidemics or pandemics, from the year 2002 onwards. Within this review we use the term 'frontline workers' as an abbreviation to refer to health and social care professionals working at the front line during disease outbreaks, epidemics or pandemics. Operational definitions of key terms are below.

Disease epidemics or pandemics

We only included studies relating to epidemics or pandemics that have occurred from the year 2002 onwards. We categorised evidence as 'epidemic' or 'pandemic' according to the WHO categorisation (WHO 2020a), and other evidence as 'outbreak'.

We included studies conducted during or after an epidemic or pandemic.

We included infectious diseases that were categorised by WHO 2020a as “pandemic or epidemic diseases”, if outbreaks occurred in 2002 or later. These may have included:

chikungunya

cholera

Crimean‐Congo haemorrhagic fever

Ebola virus disease

Hendra virus infection

influenza (pandemic, seasonal, zoonotic)

Lassa fever

Marburg virus disease

meningitis

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)

monkeypox

Nipah virus infection

novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV)

plague

Rift Valley fever

severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

smallpox

tularaemia

yellow fever

Zika virus disease

We excluded studies relating to diseases that have not been listed by WHO 2020a as a pandemic or epidemic disease. This included studies relating to the following diseases: insect‐borne diseases, including (but not limited to): dengue fever, malaria, leishmaniasis, measles, hepatitis, hand foot and mouth disease, mumps, polio, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) and HIV/AIDS.

The decision to focus on epidemics or pandemics from the year 2002 onwards was made pragmatically, with the aim of limiting the necessary searching, in order to ensure feasibility of carrying out this review rapidly. We considered the year 2002 appropriate as the outbreak of SARS occurred in 2003, meaning that we would capture studies undertaken in response to SARS, as well as more recent outbreaks of the Ebola virus and MERS (originated 2012). A similar justification for date restriction was used in a Cochrane qualitative evidence synthesis that focused on infection control during infectious respiratory diseases (Houghton 2020).

Health and social care professionals

We included studies in which the participant is any person who works in a health or social care setting in a professional capacity, or who provides health or social care within community settings deployed at the ‘front line’. This included, but was not limited* to the following.

Doctors

Nurses and midwives

Allied health and social care professionals, including all those currently regulated by the UK's Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC 2016). This includes: art therapists, biomedical scientist, chiropodists/podiatrists, clinical scientists, dietitians, hearing aid dispensers, occupational therapists, operating department practitioners, orthoptists, paramedics, physiotherapists/physical therapists, practitioner psychologists, prosthetists/orthotists, radiographers, social workers, speech and language therapists.

Students of any of the above listed professions

Health and social care assistants

*The list given here is not comprehensive of all health and social care professionals. For professional groups included in search strategy see Appendix 1 (row 12‐18), Appendix 2 (row 34‐72), and Appendix 3 (row 14‐21).

We planned to include health and social care professionals who returned to practice after a period of absence (> 3 months), for example, following a career break or retirement.

We also included students in education to become health and social care professionals where they enter paid clinical or social care practice early in order to work during the epidemic or pandemic.

We included volunteers who delivered frontline health or social care services; for example, medical or nursing staff volunteering to assist in different countries. To be included, the volunteer had to be working in a professional role, as listed above.

We excluded studies including only other people who may have frontline roles, but who are not providing health and social care, such as cleaners, porters and biomedical waste management handlers, or volunteers undertaking tasks such as delivery of medicines. We acknowledge that there are equity issues here and that evidence relating to 'non‐professional' frontline workers is of high importance. However, this was beyond the scope of this rapid review; in future updates we will consider expanding inclusion criteria in order to include this important group of workers.

Frontline

We defined 'frontline' as working in any role that brings the person into direct contact (e.g. providing care to) or indirect contact (e.g. managing a team of people who are providing care), or potential contact (e.g. working on the same ward or setting) with a patient with the disease of interest, or where the patient is suspected of having the disease (e.g. displays symptoms but disease not yet confirmed), or is considered to be at high risk of contracting the disease (e.g. working in environments where it is considered necessary for staff to wear PPE), or where the staff member is considered to be at risk of contracting the disease.

We included studies in which there is a mix of different frontline workers, if the majority were health and social care professionals. For example, where an intervention is given to all staff within a particular setting, and these staff include a mix of health and social care professionals and other frontline workers, such as cleaners, porters or receptionists. If possible, we included data from only the subgroup of health and social care professionals, but if these data were not available, we included the mixed frontline worker data and planned to explore the inclusion of this within sensitivity analyses.

We excluded:

studies focused on the mental health and resilience of health and social care professionals, where these people were not working at the front line of disease epidemics or pandemics; and

studies focused on the psychological, mental health, resilience of patients, or a combination of any or all of these.

Types of interventions

We included any intervention that was aimed at addressing mental health or resilience, or both, in the staff identified above. This could include, but was not limited to, the following.

Workplace interventions

Workplace structure and routine interventions, for example, regular breaks, shorter working hours, regular team meetings, mentorship, relaxation or recreation areas in workplaces

Provision of information, guidance, or training, for example, on dealing with difficult situations

Interventions to support basic daily needs

Interventions promoting or supporting healthy lifestyle and self‐care, for example, eating, sleeping, exercising, following a routine, avoiding excess social media, staying in touch with family and friends, engaging in enjoyable activities

Relaxation techniques, for example, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation

Psychological support interventions

Therapist‐delivered psychological interventions, delivered individually or in groups, and face‐to‐face or by text or video call, including professional psychological or counselling support, CBT and psychotherapy

Guided self‐help strategies, such as online CBT, online/web well‐being and sleep apps, and mindfulness programmes. For inclusion, guided interventions had to describe the type of support offered (e.g. telephone, online, video)

Non‐guided self‐help strategies, such as online/computer, audio or book‐based self‐guided interventions (these can also include self‐guided CBT, mindfulness, mediation, and exercises such as writing down worries)

Workplace‐based psychological support strategies, such as peer support networks, employee wellness programmes, and psychological first aid

Pharmacological interventions

Medication for depression, anxiety, sleep other mental disorders, or a combination of any or all of these.

We categorised included interventions using the headings and subgroups listed above, with the addition of new subgroups if necessary. We included multifaceted interventions that comprised a combination of interventions or strategies, including, but not limited to, those listed above.

To address objective 1, within the review of effectiveness we included studies with any comparator intervention. We categorised these as:

no intervention;

standard care;

placebo or attention control intervention; and

other active intervention(s).

We anticipated that it was possible that 'standard care' in some studies could be the same as 'no intervention'. We planned to note this, and combine these studies if it was clear that participants had received no intervention aimed at addressing mental health or resilience.

Types of outcome measures

Objective 1: review of effectiveness

As outlined in Description of the condition, there are a wide range of mental health‐related symptoms that someone may experience, and a range of impacts on the individual and their ability to function effectively within the work environment. The outcomes considered critical to this review included measures of general mental health, as these are anticipated to be of critical importance to frontline health and social care professionals, and measures of resilience as this is a measure of the ability to cope with negative effects of stress or adversity, relates to dysfunction at work, and is considered of key importance to this review, which focused on the effects of anticipated high levels of stress in the workplace. Outcomes critical to this review therefore included the following.

-

General mental health, measured by:

Symptom Checklist 90 Revised (SCL‐90‐R)

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ‐12 or GHQ‐28)

Short Form‐36 questionnaire (SF‐36)

-

Resilience, measured by:

Wagnild and Young Resilience Scale

Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale (CD‐RISC)

Brief Resilience Scale

Baruth Protective Factors Inventory (BPFI)

Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA)

Brief Resilience Coping Scale (BRCS)

Additional important outcomes included the following.

-

Psychological symptoms of anxiety, depression or stress:

-

anxiety, measured by:

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7‐Item (GAD‐7)

Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)

State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory

Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – 21 Items (DASS‐21)

-

depression, measured by:

Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9)

Beck Depression Inventory

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D)

-

stress, measured by:

Parker and DeCotiis Scale (job‐related stress)

SARS‐Related Stress Reactions Questionnaire

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS‐10)

-

-

Burnout, measured by:

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI)

Maslach Burnout Inventory questionnaire (MBIQ)

Effects on workplace staffing, measured by:

absenteeism/presenteeism

staff retention/turnover

Mental health disorders caused by distressing events, measured by:

post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – Stanford Acute Stress Reaction (SASR)

Impact of Event Scale (IES, IES‐R)

Davidson Trauma Scale

Vicarious Traumatization Questionnaire

PTSD Checklist‐Civilian Version (PCL‐C)

Chinese Impact of Event Scale—Revised (CIES–R)

Harm, adverse events or unintended consequences arising from the interventions

We noted where studies report costs; referrals, for example to mental health team; or alcohol or substance use.

We included other tools that assess these domains where those named specifically in the list above were not measured.

We did not use measuring or reporting of outcomes within studies as a criterion for inclusion within the review.

We were interested in outcomes that were recorded at the end of the intervention period ('immediate' time point) and outcomes recorded at a 'follow‐up' time point. If possible, we planned to categorise follow‐up outcomes as short‐term (< 3 to 6 months), medium‐term (> 6 to 12 months) and longer‐term (> 12 months) follow‐up.

Objective 2: qualitative evidence synthesis

To be included, qualitative studies had to report findings relating to barriers and facilitators to the implementation of interventions aimed at improving the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals. We defined a barrier as any factor that may impede the delivery of an intervention. We defined a facilitator as any factor that contributes to the implementation of an intervention (Bach‐Mortensen 2018).

Search methods for identification of studies

We used one search strategy for identifying studies eligible for a broader review on this topic (New Reference), and for identifying studies relevant to each of the objectives addressed by this Cochrane Review.

Electronic searches

An information specialist (JDC) developed a comprehensive search strategy for MEDLINE (Appendix 1), combining uncontrolled vocabulary terms and MeSH for (a) resilience and mental health interventions AND (b) health and social care personnel AND (c) pandemics, epidemics and health outbreaks; this has been peer reviewed in accordance with PRESS guidelines (McGowan 2016). We adapted and ran the search for each of the following major electronic databases on 28 May 2020.

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946 to 28 May 2020; Appendix 1).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020 Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 2)

Embase Ovid (from 1974 to 28 May 2020; Appendix 3)

Several indexes in Web of Science: Web of Science Indexes (Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIEXPANDED), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S), Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Social Science & Humanities (CPCI‐SSH); Appendix 4).

PsycINFO Ovid (from 1806 to 28 May 2020; Appendix 5).

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; from 1982 to 28 May 2020; Appendix 6).

Global Index Medicus databases (www.globalindexmedicus.net/; Appendix 7).

WHO Library Database (WHO IRIS (Institutional Repository for Information Sharing, apps.who.int/iris) last searched 28 May 2020; Appendix 8).

We ran searches from the year 2002 onwards, with no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We also conducted systematic supplementary searches (last search date 28 May 2020) to identify other potentially relevant studies including:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; Appendix 9);

Google Scholar (first 250 relevant entries) via 2Dsearch (www.2dsearch.com/; Appendix 10).

We attempted to search the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en; Appendix 11), but were unable to complete this (see Differences between protocol and review).

Where our searching identified relevant systematic reviews or qualitative evidence synthesis we handsearched the list of included studies. Due to the rapid nature of this review, we did not conduct additional handsearching. This included handsearching of reference lists of included studies and forward citation searching. These should be considered for future updates of this review.

Data collection and analysis

The methods for conducting and reporting this review followed the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020a), the Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research (Sandelowski 2007), and guidance from the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group (CQIMG, Noyes 2020), CQIMG supplemental methods papers (Noyes 2018), and Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC; EPOC 2019).

Selection of studies

One review author ran the targeted searches and excluded any obviously irrelevant titles and abstracts. Pairs of review authors independently applied selection criteria to abstracts; this stage was managed in Covidence. Pairs of review authors independently applied the selection criteria to the full papers, and 'tagged’ included studies as relevant to the Cochrane Review. Disagreements between review authors were resolved through discussion, involving a third review author.

Objective 1: review of effectiveness

We did not impose any restrictions according to language. Where titles and abstracts were in languages other than English, we used Google‐Translate to enable screening. Where studies published in languages other than English were considered at the full‐paper stage, we involved a review author or advisory group member with appropriate language skills. The review authors and advisory group are fluent in a wide range of languages (including Arabic, Bengali, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Marathi, Portuguese, Spanish). If necessary, we planned that selection criteria would be applied by one review author, with a second review author checking the translated text of included studies.

Objective 2: qualitative evidence synthesis

Studies included in the qualitative evidence synthesis were limited to those published in English, due to the potential problems associated with translations of concepts across different languages, and the rapid nature of this planned synthesis and need for additional resources if studies in languages other than those that the review author team are proficient in are to be included in qualitative synthesis (Downe 2019). Studies in languages other than English that otherwise meet the criteria for inclusion in the qualitative evidence synthesis were placed in 'studies awaiting assessment', and should be considered for inclusion in future updates of this review.

Ongoing, unpublished and preprint papers

Any studies that met the eligibility criteria, but that are still ongoing, or for which no results data are yet available, we listed as an 'ongoing' study. Reports of studies that were available as unpublished studies or preprint publications (not yet peer‐reviewed) were treated as included studies, but the publication status was noted and we planned to explore the effect of inclusion using sensitivity analysis.

Reporting of search results

We reported search results using PRISMA (Moher 2009).

Where there was a potentially relevant abstract, but we were unable to find a full paper, we listed this as a 'study awaiting assessment'. Where there was a relevant abstract for which there was no full paper, for example a conference abstract, we planned to include this study and attempt to contact study authors to obtain further data.

We listed any studies excluded at the full‐paper stage in a table of excluded studies, and provided reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

We brought together multiple reports of the same study at data extraction and considered all publications related to that study. Where there was conflicting information between different reports of the same study, we planned to base our extraction on the designated 'main' publication. Where there was a protocol and also a report of a completed study, we designated the report of the completed study as the 'main' publication, referring to both for data extraction but using the main publication if there was conflicting information relating to a study.

Objective 1: review of effectiveness

One review author (AP) systematically extracted data from all papers using a predeveloped data extraction form, within Microsoft Excel. We planned to pilot the extraction form on at least five studies prior to use, but this was not done as we only identified one study. All data extraction was cross‐checked by a second review author (AE), and any disagreements resolved through discussion.

We extracted and categorised data on the following items.

Year

Study design

Aim

Inclusion criteria

Geographical setting (countries)

Epidemic/pandemic ‐ disease, phase of disease outbreak (during outbreak/de‐escalation)

Setting (hospital, care home, community, etc.)

Participant characteristics – number of participants/dropouts, demographic variables of included participants, type (profession) of staff. We will categorise participant populations using the list above (see Types of participants), with additional categories if required. We will note when participants are people who returned to practice or were students who entered a professional role early

Intervention characteristics – described using TIDieR framework (Hoffmann 2014). We will categorise interventions according to whether the intervention involves changes at the level of individual staff members, groups of staff members (e.g. teams), an organisation (e.g. at the hospital level), or policy (e.g. National Health System (NHS) or government policy)

Comparator characteristics

Assessed outcomes

Baseline and follow‐up results data (mean and standard deviation, or other summary statistics as appropriate) for relevant outcomes. We will extract data for an 'immediate' time point – recorded at the end of the intervention period; and for a 'follow‐up' time point. Where multiple follow‐up time points are available we will extract data that reflect the following time points: short‐term (< 3 to 6 months), medium‐term (> 6 to 12 months) and longer‐term (> 12 months).

Analysis: presented analysis/es

For non‐randomised studies we planned to extract data on intervention effects, levels of precision and confounders adjusted for. We planned to document whether the following potentially confounding factors were controlled for: setting that the healthcare professional is working in, the type and grade of healthcare professional, and the length of time that the individual has worked within the disease epidemic or pandemic, gender and socioeconomic status.

Objective 2: qualitative evidence synthesis

One review author (PC) systematically extracted data from all papers using a predeveloped data extraction form, within Microsoft Excel. This was cross‐checked by a second review author (JC), and any disagreements were resolved through discussion, involving a third review author (AP) if necessary.

We extracted and categorised data on the following items.

Year

Study design

Aim

Geographical setting (countries)

Epidemic/pandemic ‐ disease, phase of disease outbreak (during outbreak/de‐escalation)

Type (profession) of staff and length of time in the profession

Whether staff have previous experience of working in the front line during an epidemic/pandemic

Details of who the frontline staff were providing care for

Type of interventions implemented

Study fidelity with a specific focus on whether the interventions were tailored or modified, or both, in different contexts

Details of any adverse events or unintended consequences

Barriers and facilitators to implementation (direct quotes)

Sampling of studies

Qualitative evidence synthesis aims for variation in concepts rather than an exhaustive sample, and large amounts of study data can impair the quality of the analysis. Once we had identified all studies that were eligible for inclusion, we assessed whether their number or data richness was likely to represent a problem for the analysis, and whether we should consider selecting a sample of studies (EPOC 2017b). Due to the relatively low number of included studies, discussion amongst review authors (PC, JC, AP) led to the decision not to select a sample of studies, but instead to extract data from all included studies.

Qualitative data management

One review author (PC or JC) extracted and coded data identified as a barrier or facilitator to the implementation of interventions (author, year, country, direct quotes, page numbers) verbatim, which a second review author (PC or JC) independently checked. We resolved any ambiguity identified through discussion with other members of the review team.

We used the best fit framework synthesis approach, which combines deductive and inductive thematic approaches to identifying barriers and facilitators (Carroll 2011). The first step involved a deductive approach, employing a predefined list of 39 constructs, grouped into five domains, from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research guide (CFIR 2020), see Table 4. We coded data against this framework. The second step involved an inductive approach to develop themes and subthemes from data that could not be categorised using the predefined codes.

2. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) constructs.

| Domain | Constructsa |

| Intervention characteristics | Intervention source |

| Evidence strength and quality | |

| Relative advantage | |

| Adaptability | |

| Trialability | |

| Complexity | |

| Design quality and packaging | |

| Cost | |

| Outer settings | Patient needs and resources |

| Cosmopolitanism | |

| Peer pressure | |

| External policy and incentives | |

| Inner setting | Structural characteristics |

| Networks and communications | |

| Culture | |

| Implementation climate | |

| Tension for change | |

| Compatibility | |

| Relative priority | |

| Organisational incentives and rewards | |

| Goals and feedback | |

| Learning climate | |

| Readiness for implementation | |

| Leadership engagement | |

| Available resources | |

| Access to knowledge and information | |

| Characteristics of individuals | Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention |

| Self‐efficacy | |

| Individual stage of change | |

| Individual identification with organisation | |

| Other personal attributes | |

| Process | Planning |

| Engaging | |

| Opinion leaders | |

| Formally appointed internal implementation leaders | |

| Champions | |

| External change agents | |

| Executing | |

| Reflecting and evaluating |

aFrom CFIR 2020. For descriptions of each construct, see www.cfirguide.org/constructs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Objective 1: review of effectiveness

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool for randomised trials (Higgins 2017). Two review authors (AP and AE) independently completed assessments, with disagreements resolved through discussion.

Had we included any non‐randomised studies, we had planned to use ROBINS‐I tool for non‐randomised studies of interventions (Sterne 2016), following the guidance in Chapter 25 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and in section 25.5 for assessing the risk of bias in interrupted time series studies (Sterne 2020).

Assessment of methodological limitations

Objective 2: qualitative evidence synthesis

One review author (AP) assessed methodological limitations, using the tool relevant to the type of individual study (see below). A second review author (PC) checked all assessments, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Qualitative studies

We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for qualitative studies to assess the methodological limitations of studies with a qualitative design (CASP 2018). We answered each of the questions from Section A and B of the tool (i.e. questions 1 to 9), giving a response of 'yes', 'no' or 'cannot tell'. We considered the 'hints' listed within the tool, and we noted our reasons for each response. We also made a judgement on the overall assessment of the limitations of the study as follows:

where the assessments for most items in the tool were 'yes' ‐ no or few limitations;

where the assessments for most items in the tool were 'yes' or 'cannot tell' ‐ minor limitations;

where the assessments for one or more questions in the tool were 'no' ‐ major limitations.

Descriptive studies

We used the WEIRD (Ways of Evaluating Important and Relevant Data) tool to assess the methodological limitations of descriptive studies (Lewin 2019). We answered each of the questions from the tool, giving a response of 'yes', 'no' or 'unclear', with consideration of the subquestions for each criterion. We combined question 5 ("Is the information accurate (source materials other than empirical studies)?" and question 6 ("Is the information accurate (empirical studies only)?") into one question ("5/6 Is the information accurate? (non‐empirical/empirical studies)"). We noted our justification for each assessment. Based on our assessment for each tool item, we made a judgement on the overall assessment of the limitations of the source as follows:

where the assessments for most items in the tool were 'yes' ‐ no or few limitations;

where the assessments for most items in the tool were 'yes' or 'unclear' ‐ minor limitations;

where the assessments for one or more questions in the tool were 'no' ‐ major limitations.

Measures of treatment effect

Objective 1: review of effectiveness

We planned to carry out meta‐analyses of pairwise comparisons for outcomes where direct evidence was available. We planned to estimate pooled effect sizes (with 95% confidence intervals (CI)) using data from individual arms of included studies, and to estimate risk ratios for binary outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes (or standardised mean differences if different studies used different measures of the same outcomes). We would have meta‐analysed complex study designs (multi‐arm, cluster and cross‐over) following established guidance (Higgins 2020b).

We planned to conduct the synthesis of non‐randomised studies according to the guidance in Chapter 24 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Reeves 2020). Where possible, we would meta‐analyse adjusted effect sizes. We planned to meta‐analyse randomised and non‐randomised studies separately.

For outcomes relating to effects on workplace staffing, we planned only to conduct meta‐analysis where we would analyse this as dichotomous data. For example, using data for the proportion of participants who have a period of absenteeism during the intervention period, those who are absent at the end of the intervention period, and/or those who have a period of absenteeism before stated follow‐up assessment points. If time‐to‐event data were presented (e.g. for absenteeism) we planned to only include these if we could convert these and analyse as dichotomous data. If count data were presented (e.g. number of periods of absenteeism) we planned not to include these unless we could determine the number of participants to whom these data relate (e.g. the number of participants who had at least one period of absenteeism).

Unit of analysis issues

For the quantitative evidence synthesis, where studies had two or more active intervention groups eligible for inclusion within the same comparison (against a control, placebo, or no‐treatment group), we intended to 'share' the control group data between the multiple pair‐wise comparisons in order to avoid double‐counting of participants within an analysis. Where we included studies that used a cluster‐randomised design, we planned to treat the group (or cluster) as the unit of allocation, and follow methods for analysis of cluster‐randomised trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020b), with advice from a statistician (AE).

Dealing with missing data

For the quantitative evidence synthesis: where studies appeared to have measured outcome data that are relevant to our critical outcomes of general mental health and resilience, but these are missing from identified reports, we planned to contact study authors by email. This included requests where the study report did not provide means or standard deviations (or data from which these can be calculated by the review authors). Where we did not obtain the missing data, or where there were missing data relating to other outcomes, we intended to highlight this within our narrative synthesis. We intended to only analyse available data and did not plan to input missing data with replacement values.

For the qualitative evidence synthesis, where studies appeared to have missing data we noted this, but did not contact study authors due to the rapid nature of this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Within the quantitative evidence synthesis, we planned to assess heterogeneity by visually inspecting forest plots and assessing I2 statistics (Higgins 2003), with random‐effects models used to address potential heterogeneity. We intended to consider an I² value of more than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

As this is a rapid review, we did not use any formal methods to assess the risk of reporting biases.

Data synthesis

Objective 1: review of effectiveness

We planned to conduct pairwise meta‐analyses using Review Manager 2020 for all primary and secondary outcomes listed above, for comparisons of:

intervention versus no intervention

intervention versus standard care

intervention versus placebo or attention control

and for outcomes measures:

immediately after the end of intervention

at follow‐up. If data are available, we will present data for short‐term (< 3 to 6 months), medium‐term (> 6 to 12 months) and longer‐term (> 12 months) follow‐up.

We did not plan to conduct any meta‐analyses for comparisons of one active intervention with another intervention.

We planned to summarise and tabulate important clinical and methodological characteristics of all included studies (including randomised and non‐randomised studies). Where study results were pooled within meta‐analysis, we intended to judge our certainty in each pooled outcome using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2020). We created a 'Summary of findings' table for the comparison of 'intervention versus no intervention'. We did not create planned 'Summary of findings' tables for 'intervention versus standard care' or 'intervention versus placebo or attention control', as we included no studies with this comparison. Our 'Summary of findings' table includes results relating to the following outcomes.

General mental health

Resilience

Anxiety

Depression

Stress

Burnout

Absenteeism

We planned to include in the 'Summary of findings' table, results measured immediately at the end of the intervention and at one‐year follow‐up (if data were available).

We planned to structure our main narrative summary of findings first by the intervention, using the predefined broad intervention headings listed under Types of interventions, second by comparison group, and third by outcome. Within the narrative we intended to refer to the study participants, and to areas of similarity or differences (clinical heterogeneity) between the studies. For the included study, for which there were no data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis, we provided a brief table summarising results reported by the study, and referred to these tabulated data within a narrative synthesis. Had we had suitable data, we had planned to comment on whether there were agreements or disagreements between our meta‐analysis and studies not included in meta‐analysis, with reference to the risk of bias of studies.

For any outcomes not included in the 'Summary of findings' table, we planned to provide a brief narrative synthesis of key findings. We also planned to provide a brief narrative synthesis of key findings of studies that had comparisons of one active intervention with another active intervention. We followed the Synthesis Without Meta‐analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews reporting guideline (Campbell 2020).

Objective 2: qualitative evidence synthesis

We brought evidence relating to barriers and facilitators together using a narrative synthesis supported by Summary of Qualitative Findings (SoQF) tables and figures organised around the five major domains that may influence an intervention’s implementation, as reported in the Consolidated Framework of Implementation Research (CFIR 2020). These five factors included:

intervention characteristics;

outer settings (i.e. environmental factors);

inner settings (i.e. organisational factors);

individual characteristics;

implementation process characteristics.

We used the GRADE‐CERQual approach to assess our confidence in each finding (Lewin 2018), reaching agreement through discussion. GRADE‐CERQual assesses confidence in the evidence, based on the following four key components.

Methodological limitations of included studies: the extent to which there are concerns about the design or conduct of the primary studies that contributed evidence to an individual review finding. For this component we considered the assessment of methodological limitations, using the CASP or WEIRD tool, for each study that contributed to a review finding. We considered whether the inclusion of evidence from studies judged to have minor or major limitations reduced our confidence in the findings, and recorded these decisions within our evidence profiles.

Coherence of the review finding: an assessment of how clear and cogent the fit is between the data from the primary studies and a review finding that synthesises those data. By cogent, we mean well supported or compelling.

Adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding: an overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding.

Relevance of the included studies to the review question: the extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a review finding is applicable to the context (perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in the review question.

After assessing each of the four components, we made a judgement about the overall confidence in the evidence supporting the review finding. We judged confidence as 'high', 'moderate', 'low', or 'very low'. The final assessment was based on consensus among the review authors. All findings started as high confidence and we then downgraded the findings if we had important concerns regarding any of the GRADE‐CERQual components.

Overarching synthesis

We planned to produce a brief narrative synthesis that brings the findings from the quantitative and qualitative syntheses together, but due to lack of evidence from the quantitative synthesis we did not complete the planned formal overarching synthesis (see Differences between protocol and review).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Had we conducted the planned quantitative evidence synthesis: we would have explored differences between subgroups based on the following.

Type of intervention (including whether intervention is targeted at individual/group/organisation/policy)

Duration of intervention delivery (one‐off, < 3 months, 3 to 6 months, > 6 months)